Barriers to Health Service Access: Three

Geo-cultural Regions of Peru

Maritza Pintado Caipa

Atlantic Fellow for Equity in Brain Health

Oscar Ramirez Atlantic Fellow for Health Equity U.S.

Alex Kornhuber

Atlantic Fellow for Equity in Brain Health

Kate

Irving Professor of Clinical Nursing, Dublin City University

Introduction

Peru is one of the most diverse countries in the world, divided into three main geo-cultural regions: the Pacific coast, the Andes, and the Amazon; each of which incorporates a unique set of characteristics that influence the health of their populations. Peruvian diversity must be measured through cultural and ethnic variables (60% mestizo, 22% Quechua, 20% white, 6% black, mulatto, zambo or Afro-Peruvian; 2.4% Aymara, and a small percentage of Amazonian indigenous cultures), linguistic variables include 47 languages: 43 Amazonian, three Andean, and one European; Spanish being the official language along with Quechua and Aymara.

Nutritional and culinary practices, as well as environmental and geographic variables, and belief-systems, all influence the economic development, life opportunities, health and well-being of communities. It is well documented that access to health services have systemic deficiencies (1) and that the Peruvian public health system, in general, has been suffering for decades from inadequate management, financing, and epidemiological surveillance functions. However, within these limitations, diversity is not always considered and that directly or indirectly has an impact on the quality of health services and outcomes.

Most currently available information on health comes from surveys and reports based on technical, economic, and social specifications, largely carried out in more urbanized areas with better access, without considering the dimensions of the country's diversity. Therefore, this report addresses the scant data on the perception of health access in Peru’s most underserved populations –generally from rural or non-urbanized settings on the coast, Andean highlands, and Amazon jungle– while attempting to respond to these information gaps.

In addition, this report relies on photography as a powerful tool for greater social awareness and empathy for distant and varied realities. Medical sciences and photography both seek to meticulously observe and understand human beings, although through different methods, but we believe that this collaboration may lead to novel perceptions, ideas, and solutions.

1- San Regis, a small Amazonian town in the district of Nauta, Loreto Region, only accessed by boat

2- Santa Maria is a slum in the district of San Juan de Miraflores (SJM), located on the outskirts of the capital city of Lima

3- The town of Pomacanchi belongs to one of the seven districts of Acomayo Province in Cuzco Region, located in the Southern Andean highlands of Peru

Peruvian Context

Peru has gone through a decade of sluggish growth (2014-2024), defined by low-quality job creation and a poverty increase of 1 5% in the last year (a third of the population lives in poverty or extreme poverty), in stark contrast to the previous decade (2004-2013), which saw sustained economic growth In recent years, Peru’s political instability –six presidents in the last six years, and three imprisoned ex-presidents– has added another layer of complexity to its social, economic, and institutional transformations, which, altogether with climate change, make Peru a highly vulnerable country.

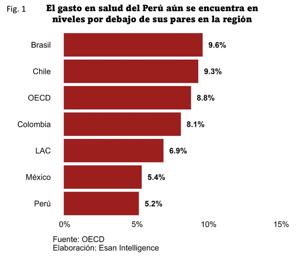

The Peruvian government’s health spending, in relation to GDP, has been below regional average (6 9%) and below the 9 3% average held by those countries that comprise the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). By 2024, a 9.2% budget increase over the previous year has been allotted; however, historically, much of this budget ends up not reaching its targets (between 50% and 75%) due to inefficient management (5). Thus, in 2022, 87 4% of primary health care facilities had inadequate capacity, such as precarious infrastructure and obsolete, inoperative or insufficient equipment (6).

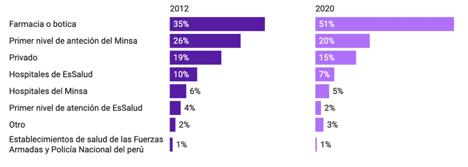

Chart 1

Peru’s health system, like many other Latin American countries, has fragmented and segmented services and financing, which leads to poor responses addressing health problems (7). It is composed of two large sectors, public and private, divided into five subsystems that provide health services to the population: MINSA, Social Health Insurance, Armed Forces Health, National Police Health, and private sector institutions (8). Over time, efforts have been made to integrate the Peruvian health system, but the current regulatory framework does not

correct this fragmentation. On the contrary, it accentuates and perpetuates State inefficiency in public resource management, in addition to limiting local governance (9)

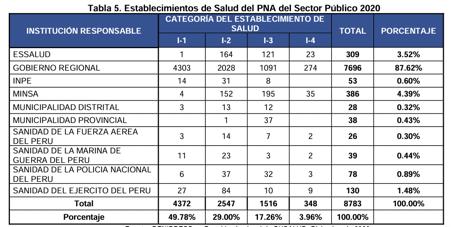

Table 1: Public health care institutions

Source: Diagnosis of gaps in infrastructure or access to health services, Minsa (2023).

By 2020, Peruvians had 8783 health posts and health centers that made up the country’s first level of care (FLC), all of them distributed among these subsystems If these FLC services functioned adequately, they could address 85% of people's health problems. However, 94% of these facilities have not improved their medical infrastructure nor equipment during the past five years (6). Currently, the Regional Health Directorates are responsible for most health posts and centers, but they depend financially on regional governments, whose priorities are not always focused on primary health care (6).

As of fourth quarter 2023, approximately 90% of the population had some type of health insurance. Nearly 60% of people were affiliated only to the Seguro Integral de Salud (SIS, or Integral Health Insurance), directed to low-income people in rural and urban areas; 30% to EsSalud, where most salaried workers are found; and 6% to other insurance (for the Armed Forces or Police, private, among others) (10), the latter corresponding to a population with greater purchasing power in more urbanized areas.

Despite efforts toward universal insurance, health centers are not the first, but the second option Peruvians turn to when faced with a health problem, after drugstores (11). This phenomenon is most evident in cities and towns, so this leads to the question: Where do people from neglected rural or non-urbanized communities go for healthcare?

Source: National Household Survey (ENAHO)

Chart 2: Primary health care venues

Three

Case Studies on Access to Healthcare: The Peruvian Coast, Andes, and Amazon

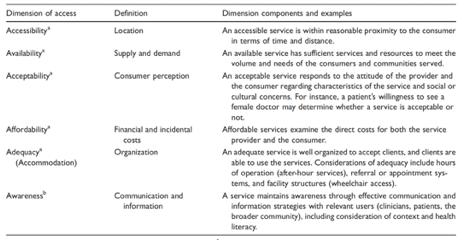

To research the experience of barriers and perceptions of access to health services in Peru, we directly connected with people living in three socially and geo-culturally distinct regions of the country. In each, we visited communities and conducted a dynamic focus group with specific and open-ended questions to gather their experiences, perspectives, and insights; giving each participant the possibility to express with openness, clarity, and confidence. To measure and describe access to health care in Peru’s three different geo-cultural regions, we will discuss this concept in all its dimensions; particularly through the Penchansky & Thomas model, which postulates Five A’s: accessibility, availability, acceptability, affordability, and adequacy These dimensions of access to health services are independent, but interconnected and each is important for its overall assessment

In addition to these, a subsequent study incorporates “awareness” as another salient dimension that influences access because it is linked to knowledge and comprehension, which become constituents of health literacy (2) Awareness goes both ways; it requires a service that is aware of the local context and the needs of the population to provide more appropriate and effective care, and for patients –or people, in general– to have the necessary knowledge or awareness to enable them to seek, access and make better use of these health services (3).

In Peru, access to health services is a particular concern in rural and remote areas due to structural challenges, such as socioeconomic disadvantage, small and dispersed communities, long distances, unpaved or inexistent roads to these villages, labor shortages or lack of trained human resources. Access to health goes beyond the use of services or the presence of a facility; rather, the test of access is the use of a service by those who need and would benefit from it. Along with use, the dimensions of access include concerns about barriers, relevance, and equity in accessing these services (4).

Table 2: Dimensions of Access

Taken from: Improving access: modifying Penchansky & Thomas’s Theory of Access, Emily Saurman; Journal of Health Services

Focus Groups and Communities

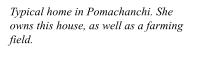

We held our first focus group in March of 2023 in Pomacanchi, a town at 3693 meters above sea level that can only be reached after a 4-hour drive from the city of Cuzco. Ten people participated in this focus group: two men and eight women In general, people in this locality are busy working on their land, with cattle and crops. Here, they often distrust Lima residents, a historical and political feature of this region Proud of their heritage as descendants from the Inca empire, they resent Lima’s centralism.

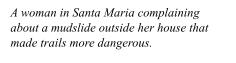

The other two focus groups were carried out in June 2023. We first visited the slum of Santa Maria, located on the outskirts of the capital city of Lima The focus group consisted of 10 people, mostly women; one of the few men was the mayor of the community of Santa Maria. It was difficult to recruit participants because they were too busy making a living

In addition, they were worried that the purpose of the focus group was to get them into trouble or to evict them from their land. After overcoming initial mistrust, we agreed to have breakfast together Possibly, this was the main reason for the attendance of some They were also self-conscious about their educational abilities and this created an “us and them” mentality that had to be navigated by our team However, once they began to talk, they did share their stories openly.

Then, we traveled to San Regis, a small Amazonian town, after an hour and a half flight from Lima to Iquitos, followed by a 2-hour drive to the port of Nauta, from where we boarded a boat on the Marañon River, and went upriver for six hours. This is the only route because it’s costly to construct and maintain roads in the Amazon, and the Peruvian State has not yet developed a road system in this part of the country.

The focus group was attended by 10 people: six men and four women. Recruitment in this geo-cultural region was different than in the previous two communities because people were keenly curious about us –the strangers in town– and were enthusiastic to meet with us and talk. Also, San Regis residents had more flexible work hours than those in the other two areas we had visited, therefore it was easier to set a time and date for the focus group meeting.

Santa Maria

Health in Context

According to the Peruvian Ministry of Health, respiratory tract and digestive system infections –specifically, intestinal– are found among the residents of Pomacanchi, Santa Maria, and San Regis, possibly due to the lack of basic sanitation services, such as drinking water and adequate sewage. Also, in common, both the coastal and Andean populations visited suffered from nutritional deficiencies and its consequences

Regarding the main causes of death, there was no official data for San Regis, which demonstrates it is not a priority for the Peruvian State, although we were informed while conducting fieldwork that death during childbirth was still significant In terms of mortality, both Santa Maria and Pomacanchi had respiratory infections and ischemic heart disease as leading causes, although the Andean town additionally had a prevalence of cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases, probably linked to alcohol abuse.

The community of Pomacanchi administratively has a level I-4 health facility with inpatient beds and a range of services dedicated to environmental, family and communal health These include prenatal, perinatal and postnatal care, comprehensive nutritional advice; cancer prevention, rapid tests and sampling, community-based rehabilitation; early cancer diagnosis, outpatient surgery, ultrasound and radiology (13). Yet, physical spaces, equipment and supplies are inadequate to ensure timely and effective care for patients Also, there is not enough personnel to cover the population’s demands and, therefore, care is hasty and nonoptimal.

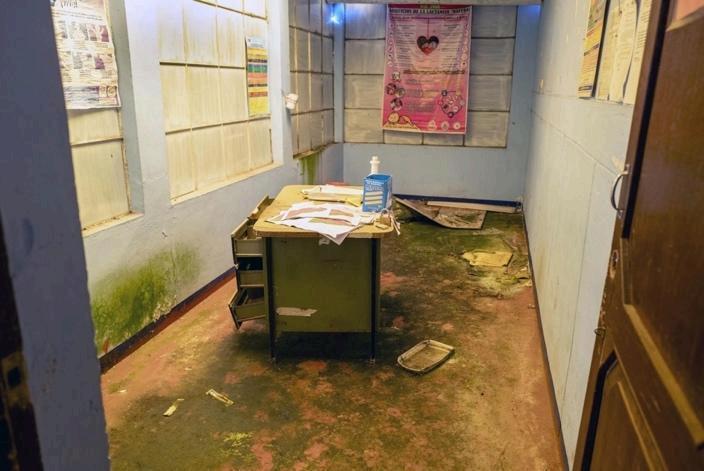

Whereas in San Regis, the community’s health post has recently been recategorized from I to I-2, according to the Ministry of Health’s categorization system, (13) and –therefore– San Regis should have at least the following: family and community health services, community environmental health, drug dispensation, maternity care, comprehensive nutritional assessment and advice, early cancer diagnosis and prevention, rapid testing and sampling, as well as community-based rehabilitation, in addition to outpatient surgery interventions.

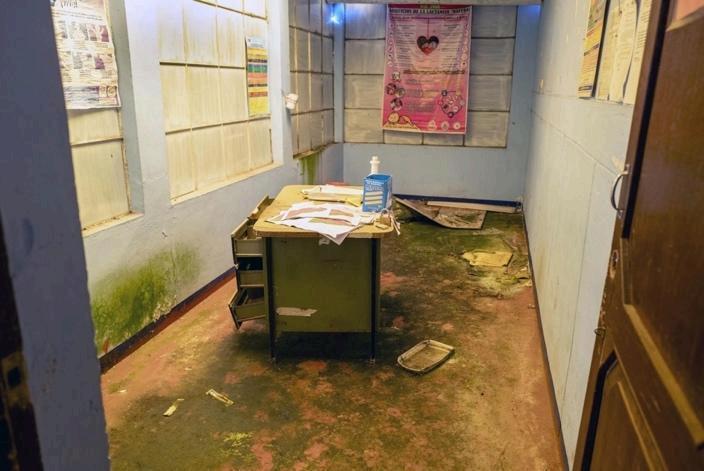

Nevertheless, this health center has neither running water, electricity, nor a generator, which limits care to daytime hours. When there are emergencies at night, staff must use flashlights and lamps. It would be utopian to think of having air conditioning to cope with the intense and permanent humid heat. Another major limitation is that health personnel do not have a deslizador (or a fast motorboat) nor any type of boat that serves as an ambulance and allows them to move from one place to another in case of emergency, either to a small community or to the city of Nauta to commute patients who need more specialized care

Thus, commuting is a shared experience in all three locations: residents of Santa Maria must travel large distances for basic health care in Lima; in Pomacanchi and San Regis, people leave for larger cities to find more specialized health services

Accessibility

Commuting for better health care services is a constant phenomenon in all locations visited In Santa Maria, at the outskirts of Peru’s capital, accessing primary health care services, in terms of time, distance and transportation facilities, results challenging This population does not have a primary health care center nor health worker nearby to help them in the prevention, management, and control of their illnesses

In this type of population, many –or most– of the people use the Integral Health Insurance (SIS), affiliated to the Ministry of Health. To access this service, they must commute to more urbanized districts, which also poses multiple challenges because of Lima’s chaotic public transportation system and its lack of urban planning and infrastructure. In addition, this implies greater costs, not only in economic terms, but also regarding time because of great distances and heavy traffic. Since Lima is Latin America’s most congested city, it is common for residents to consider it a "waste of time and money" to seek medical attention

When we contrast Santa Maria and Pomacanchi, the latter has a health unit in the community center that is accessible for all. Despite this service, if someone needs more specialized care, that person must travel with a relative to the city of Cuzco Most Pomacanchi citizens are not acquainted with the region’s capital and find it intimidating and extremely difficult to make the trip

Similarly, in the Amazonian community of San Regis, patients must travel to the cities of Nauta and Iquitos to receive more advanced health care services. Beyond San Regis, other small communities in this part of the Amazon do not have their own health centers and access is more problematic for these villagers. During the dry months, small tributaries dry up and the route becomes more long and arduous: first, by foot to the main river and, then, by boat to the nearest health unit.

Adequacy

Because of the Peruvian health system’s disorganization, most services and accommodations are inadequate This contributes to significant overload for health care personnel who cannot cope with the system’s deficiencies. Often working in small facilities, they do not have interconnected referral and counter-referral systems Also, there is little chance of improving staffing levels. In short, they do not have the equipment, supplies nor materials to ensure timely and accurate care As a result, health personnel operate under great pressure and in precarious conditions, putting their physical, mental, and emotional health at risk.

Most significantly, the Santa Maria health center was closed because of its poor state of repair and inadequate staffing No subsequent center was reopened This is the starkest realization of inadequacy: a primary health care option does not exist.

In Pomacanchi, where there is a health center, staff work under constant pressure, in precarious conditions, running the risk of entering into a state of routinary apathy Insufficient attention has been paid to reducing or eliminating language barriers; many health workers, especially doctors, only speak Spanish, despite treating Quechua-speaking citizens

Pomacanchi’s health facility is a semiadapted, cold, overcrowded, and precarious environment with old and dusty furniture, scant maintenance or cleaning, where the only ambulance was broken Its installations, found in the community center, do not offer the space nor the minimum comfort for health workers and users. This situation has been going on for several years because the old facility, located in the lower part of town, was flooded during a rainy season and became unusable; although they admit that these facilities were also quite deteriorated even before the flood.

In June 2023, the new health center was inaugurated. Although fully equipped and furnished, this building, managed by Cuzco’s regional government, has not been delivered to the Ministry of Health for its implementation due to administrative and logistical bottlenecks between these two entities. In addition, personnel are somewhat reluctant to move because they will have to undertake additional training and they are not enthusiastic about this.

Whereas in the Amazon, San Regis has a small, dilapidated health center, but its personnel try to keep it clean and tidy. It has seven small rooms: a reception area for admission and triage, a storage for medical records and medications, a doctor's office, a nurse's office, an obstetrics office, an emergency room, and another space for multiple uses (perhaps for childbirth or to keep patients in observation for a few hours).

If the residents of Santa Maria do decide to go to a health center or hospital in one of the surrounding districts, they run into oversaturated hospitals and do not have the necessary human, infrastructure, supplies, and other resources to meet the basic health care needs of these populations. Focus group participants informed us that they are commonly forced to form long lines from the very early morning, at the doors of these institutions, hoping to access a slot for that day; and, –if they fail– they must return the next day with the same purpose, until they can be attended

In turn, Andean Pomacanchi has a health facility that comprises a multidisciplinary team of two doctors, nurses, midwives, a psychologist, nursing technicians, a biologist, and a social worker Nevertheless, staff described feeling overwhelmed by the workload, exacerbated by systemic inefficiencies because this health unit has not been purpose built, but has rather been temporarily lodged by the Municipality of Pomacanchi in the community center With limited services, understaffed health personnel are unable to perform their tasks adequately, yet –according to the health facility’s manager–, they cannot hire more workers because they are overcrowded. Also, they must first relocate to the recently built health center before renewing furniture

While collecting this data, we then visited the Amazonian community of San Regis and met a SERUMS1 –or rural service– doctor, who had recently arrived to San Regis; he told us of a deeply frustrating and painful experience: Around noon, on a certain day, he received an emergency call about a 25-year-old woman from another village who had given birth and was suffering from postpartum hemorrhage. They immediately looked for a speedboat to reach the patient’s community, but it took them four hours to find one and fuel. Once they arrived, they were saddened to find out that the patient had died from a hemorrhage caused by retained placental delivery and had left a baby girl and four other children between the ages of two and seven. Her body was transferred to Nauta for autopsy.

1 SERUMS is the acronym of Servicio Rural y Urbano Marginal de Salud, or literally, “Urban-Marginal and Rural Health Service,” which recruits young doctors and assigns them posts in the countryside or at the outskirts of Peru’s main cities. They must complete this program to officially graduate from the university and be eligible for working in Peru’s public health system.

Acceptability

The population’s perception in Santa Maria regarding primary and hospital care in the health system, in general, is not favorable; specifically, in terms of quality. The common comment is that the government should have more oversight or control of the users’ care, which is primarily hampered by excessive delay or, in the case of hospitalization, an access to a bed. This also occurs with the Integral Health Insurance (SIS) or employee insurance (EsSalud) People often complain that patients should be treated with more human warmth. Failing acceptability (closely linked to availability) also makes early intervention –the hallmark of good public health care- impossible, not to mention prevention: nobody under these circumstances may access health services if nothing is evidently wrong

Another barrier toward acceptability is seen in the Amazonian community of San Regis where the health facility has only one permanent worker. Intermittently, the Ministry of Health sends a doctor, a nurse, or an obstetrician through the yearly SERUMS Program This small personnel often rotates and the understaffed health center is sometimes closed, which affects patients in an emergency and who may need to commute

In other cases, misinformation deters certain populations from visiting public health centers When doctors of the San Regis health unit sought to aid a woman who was hemorrhaging; unsuccessfully, they arrived too late and carried the corpse for necropsy When the doctor and his fellow workers asked for more details, they understood the multifaceted issues that could

have prevented this outcome.The pregnancy had been concealed due to false beliefs: this woman’s family had been warned in the city that if she had another child, they would tie her tubes. We do not know when or how this happened, but the family and community had agreed not to declare anything, so she did not undergo fetal monitoring, as it normally occurs with local pregnant women to prevent maternal or neonatal death.

Affordability

In addition to the long waiting lines to which users are subjected, often, if they finally access the service, they are disappointed that despite having the state care insurance, or some other type of insurance, they must pay for their own supplies, diagnostic tests, and other complementary care.

This greatly affects affordability, since for this type of population, it may be discretionally "faster, safer and cheaper" to first use "natural or homemade medicine" to treat their ailments, such as in respiratory diseases. They usually use concoctions, learned through generations, based on herbs, lemon and/or sugar cane alcohol.

The population has faulty health beliefs that pose barriers to their acceptance of conventional remedies for their ailments. Generic drugs are the same as branded drugs, just less expensive, but there is a belief that they are not as good. Sometimes they self-medicate by going to the nearest drugstore, asking for products they saw on television or asking the person in charge for recommendations.

Only when people do not get any better or the situation worsens, they seek specialized help in a public or private medical center. In this sense, the risk is high since many of these drugstores or private medical offices do not have appropriately qualified personnel: they often lack the licenses, thus putting their safety or life at risk and, even, that of a loved one. This leads to higher expenses, in the short and long term, for the family and the State, which ultimately covers the costs of recovery, disability, orphanage, and death.

Awareness

Due to widespread negative perception, it is crucial to generate awareness and foster information bidirectionally, i.e. from the providers of health services to the population and vice versa. Although there are some general and massive public policy efforts that try to create awareness of these services, these are often hampered by the State’s cultural ignorance and lack of attention to the population’s specific needs.

Peru’s vast geographic, economic, and sociocultural diversity generates a chasm that translates into the population’s mistrust toward health services, since they frequently do not feel seen or cared for These divisions become evident in the campaigns carried out by the Ministry of Health, the local government, or other organizations on topics such as healthy eating and hygiene because they demand people to wash their hands, but –for example– there’s no running water in Santa Maria.

Crucially, people in Santa Maria acknowledge that they would like to receive help with issues related to mental health, such as "psychology talks," because one of their main problems is –widespread and transgenerational– family violence. Even though participants have stressed the importance of breaking this pattern, they have made scarce progress in this regard and their perception of abandonment is quite marked.

Overwhelmingly, in Pomacanchi there are real and perceived divisions between health providers and users due to poor communication and information, which hinders health literacy. Moreover, prevention, diagnostics and timely treatment interventions are virtually impossible for these reasons. Also, important State-sponsored health promotion attempts and policies are not easily understood by the Quechua-speaking population in linguistic terms and are not perceived as reliable due to mistrust.

In San Regis, the population has a better relationship with health staff and understands what the local center can or cannot provide. Yet, people are also aware that there should be more interaction, training, supervision, and orientation of the health personnel towards them to improve their quality of life in areas such as disease prevention and safe food handling.

Conclusion

The three case studies clearly show Peru’s geo-cultural diversity, but each evidence a different set of barriers to healthcare access whose improvement would have to take careful account of these complex interconnected factors. For example, in the Andean Region the issue of health information being in the wrong language contributes to cultural distrust, which is a major barrier In the coastal part of Lima, lack of trust is also significant, but this comes from people fearing the loss of their small properties by third parties

The model used here, adapted from Penchansky and Thomas by Saurman et al , has been a useful tool to explore access to healthcare in all three communities. We found it to be complete and we did not require additional factors to describe the barriers to health service

In each region, attention to appropriate messages related to health information could improve these services and people’s involvement, thus increasing acceptability and overall health literacy When health information is provided, but impossible to carry out in the context in which a population lives, this advice causes disapproval. Therefore, investing more money on major issues does not necessarily solve the problem if communication is not based on listening and providing advice according to local realities.

In Santa Maria, the access issues found in the coastal area of Lima are mainly related to poverty, whether extreme or not The State’s health messages become irrelevant due to the lack of resources that Santa Maria’s people endure. In a context in which the demand for services outweighs the supply, awareness of the benefits of disease prevention and health promotion are not a priority.

Whereas Pomacanchi experiences a different set of barriers to accessing healthcare than those seen in the coastal region of Peru, ultimately the result is the same: utterly poor access to health care However, other strategies must be adopted to overcome these barriers In

addition, Pomacanchi’s remote location limits access to more specialized services while –at the same time– the inadequacy of local facilities, held up by red tape, is exacerbated by poor awareness driven by a lack of attention to cultural and linguistic diversity.

Given that the Pomacanchi health center only has the most basic equipment, increasing its capacity would allow local treatment of common ailments rather than requiring traveling to Cuzco.

In contrast, the community of San Regis is affected by its remote location, since limited transportation options make access to any secondary health center difficult or impossible Also, it lacks adequate facilities, its health center is understaffed and a significant number of villagers live in extreme poverty Yet, services are acceptable and people respect and trust local health personnel, possibly because they perceive an overwhelming sense of abandonment and are, therefore, grateful for any service they can get access to The need for primary prevention is additionally important given the community’s remoteness. Health literacy, in general, is a major issue, but due to the positive rapport between health workers and the population, this could be addressed more easily in San Regis than in other communities.

Although scarcity creates great disincentives to access in all regions, this was most acutely felt in Amazonian communities because of their basic infrastructure, remote location, and inadequate services for major health grievances. For example, villagers said that they would like to receive help with mental health issues While this is not necessarily recorded as a morbidity in this area, it is behind many issues, such as violence and alcoholism, which in turn, cause other health issues. It is not only a matter of refurbishing facilities, but of working with staff who have appropriate skills and cultural empathy to assist people with mental health issues.

In all of these communities, barriers to health service access are most keenly felt by vulnerable populations: children, older adults, and pregnant women. At the same time, inadequate services creates pressure for healthcare staff who are frequently working under extreme adversity. It is a system that offers poor working conditions for its health staff and –yet– these are expected to treat people kindly and with the utmost care.

Despite the overwhelming amount of problems and conditions in the vast and complex geo-cultural realities of Peru, we believe that this report is a call to action: if we listen to the issues expressed by community members and work with strength and resilience toward more sound public policy, at least a part of the system could improve.

References

1 “Evolution of monetary poverty, 2010-2021 ” National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI, due to its acronym in Spanish). <https://www inei gob pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones digitales/Est/pobreza2021/Pob reza2021.pdf>

2 Saurman, Emily. “Improving Access: Modifying Penchansky and Thomas’s Theory of Access ” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, vol 21, no 1, 15 Sept 2015, pp 36–39 <journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1355819615600001>

3 Saurman, Emily, et al. “Responding to Mental Health Emergencies: Implementation of an Innovative Telehealth Service in Rural and Remote New South Wales, Australia ” Journal of Emergency Nursing, vol. 37, no. 5, 1 Sept. 2011, pp. 453–459. <www sciencedirect com/science/article/abs/pii/S0099176710005337>

4 Penchansky, Roy and J William Thomas “The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction.” Medical Care, vol. 19, no. 2, Feb. 1981, pp. 127-140. <http://www jstor org/stable/3764310>

5 “Health in Peru: An enormous pending challenge ” Universidad del Pacífico, 25 July 2023 <https://www.up.edu.pe/prensa/noticias/el reto de la salud fiestas patrias 2023>

6 Diagnosis of gaps in infrastructure or access to health services Peruvian Health Ministry (Minsa), August 2023.

<https://cdn www gob pe/uploads/document/file/5058113/Diagn%C3%B3stico%20de%20la %20Situaci%C3%B3n%20de%20%20Brechas%20de%20infraestructura%20o%20de%20ac ceso%20a%20servicios%20del%20Sector%20Salud%20%282025-2027%29 pdf>

7 Oswaldo Lazo-Gonzales, Jacqueline Alcalde-Rabanal and Olga Espinosa-Henao “The health system in Peru: situation and challenges”. Colegio Médico del Perú, 2016. <http://bvs minsa gob pe/local/MINSA/4141 pdf>

8 Oscar Cetrángolo, Fabio Bertranou, Luis Casanova, and Pablo Casalí “Peru's health system: current situation and strategies to guide the extension of contributory coverage.” International Labour Organization, 2013 <http://bvs.minsa.gob.pe/local/minsa/2401.pdf>

9 Oscar Cosavalente-Vidarte, Leslie Zevallos, José Fasanando, and Sofía Cuba-Fuentes. “Transformation process towards Integrated Health Networks in Peru ” Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública, vol. 36, no. 2, June 2019, pp. 319-25. <http://dx doi org/10 17843/rpmesp 2019 362 4623>

10 “Living Conditions in Peru ” National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI), 2024 <https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/6970764/6011541-condiciones-de-vida-en-el -peru-abril-mayo-junio-2024.pdf>

11 “National Household Survey 2022.” National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI). <https://www.datosabiertos.gob.pe/dataset/encuesta-nacional-de-hogares-enaho-2022-institu to-nacional-de-estad%C3%ADstica-e-inform%C3%A1tica-%E2%80%93>.

12. Valdeavellano, Rocío, et al. “Características de los barrios marginales de Lima” in El saneamiento básico en los barrios marginales de Lima metropolitana. UNDP/World Bank, 1998. <https://www2.congreso.gob.pe/sicr/cendocbib/con4 uibd.nsf/B5BB9C6DBA9AF49A05257D C50081492E/$FILE/40 pdfsam 720450WP0SPANI0s0Lima0Metropolitana.pdf>

13 “What is the first level of health care?”, Peruvian State Digital Platform. <https://www.gob.pe/16728-servicios-y-categorias-del-primer-nivel-de-atencion-de-salud>