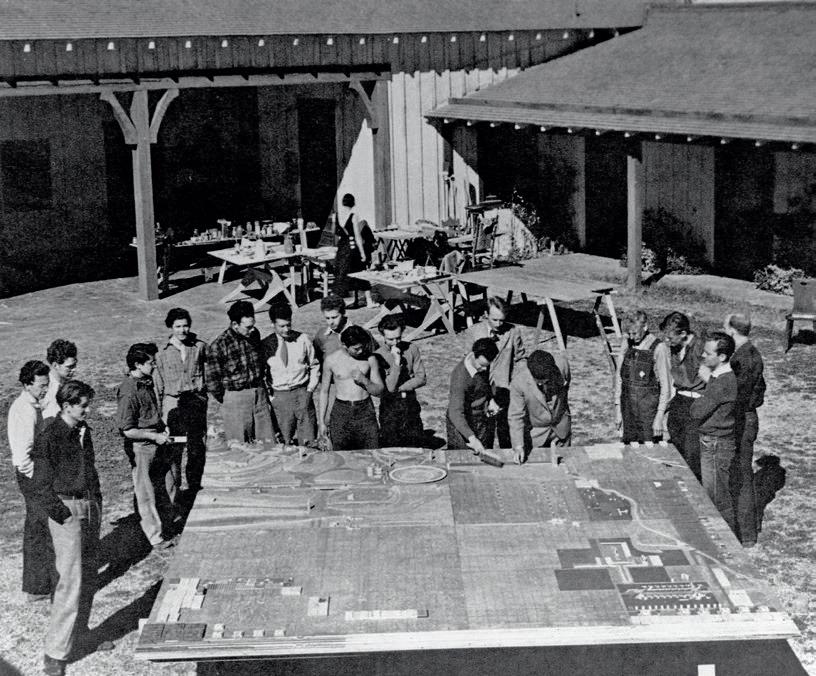

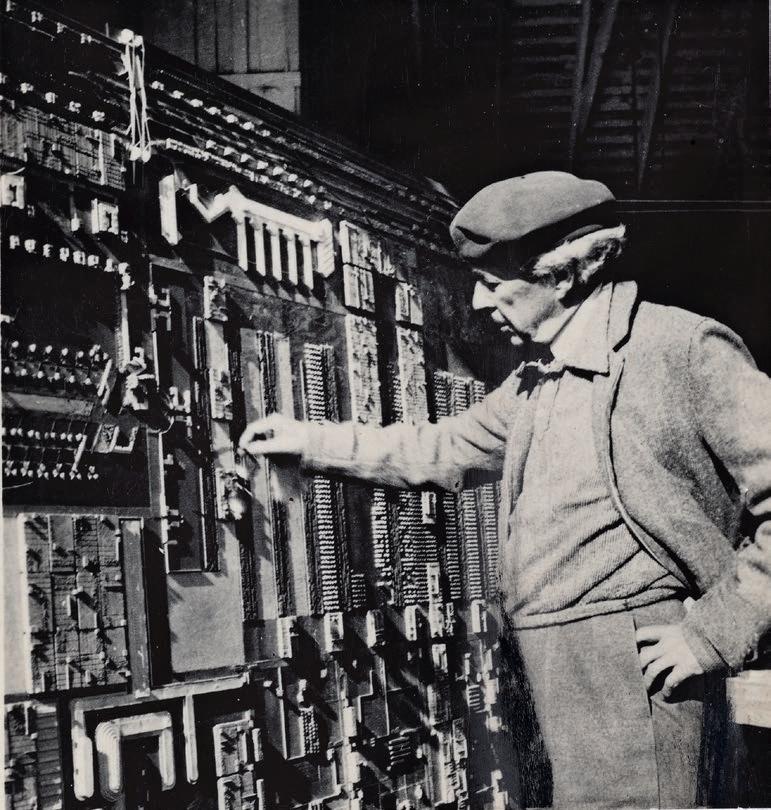

The model’s visually compelling iteration of Broadacre City was lovingly constructed—and later adapted and repaired—by groups of architectural apprentices who came to live and work alongside Wright at the Taliesin estate in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and subsequently at Taliesin West in Arizona [fig. 5] This educational scheme, known as the Taliesin Fellowship, was established in 1932; it ran concurrently with the Broadacre City project, which remained an idée fixe for Wright until his death in 1959. The Taliesin apprentices assisted their master in refining his ideas for Broadacre through a steady flow of experimental models, drawings, publications, and exhibitions.

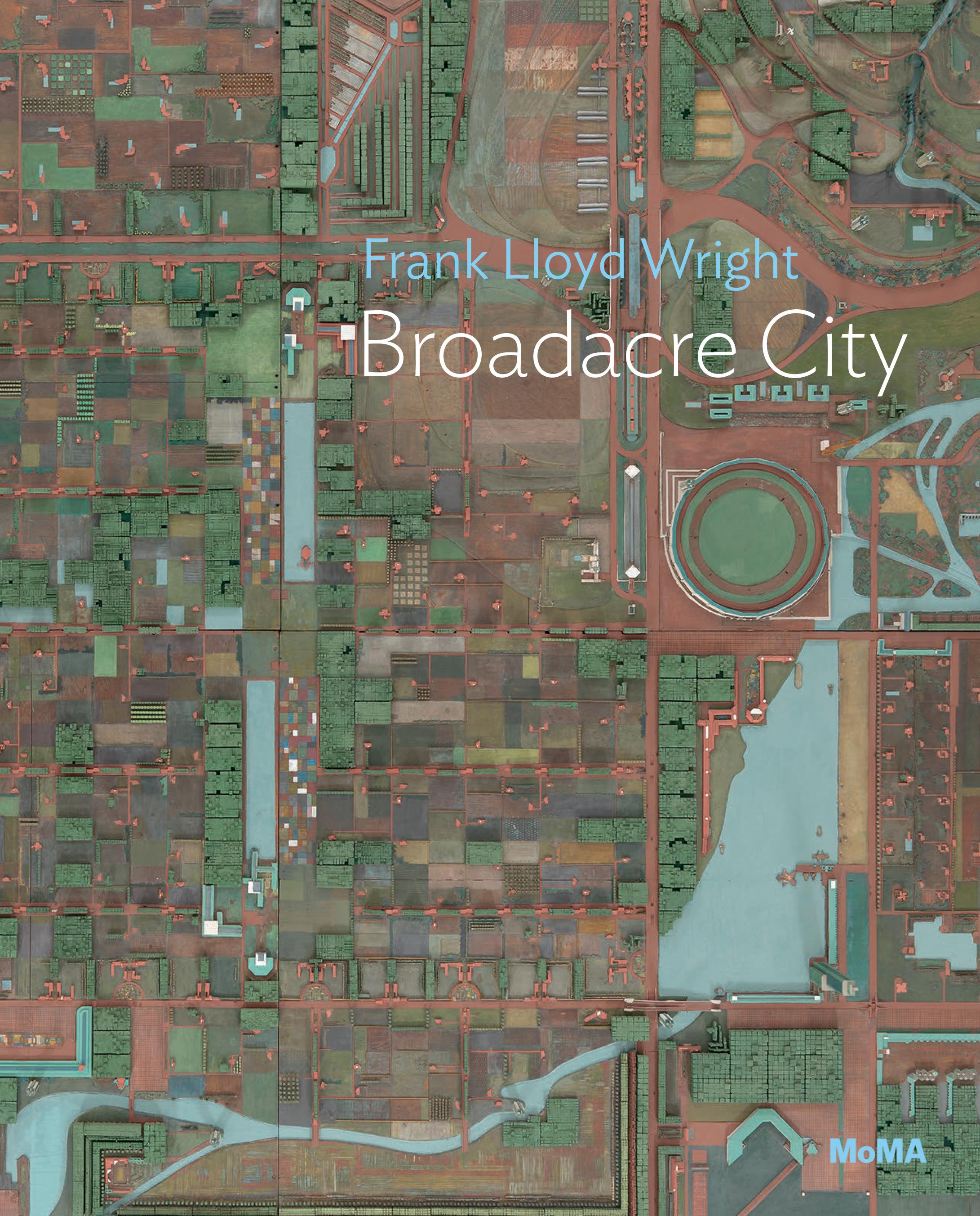

Broadacre City was not so much a fixed template for a defined location as a polemical demonstration of possibilities that could embrace “all of this country.” It existed, Wright said, “everywhere, or nowhere”—a utopia in the original sense of the ancient Greek word: a “non-place.” 6 In the absence of restrictive budgets

or interference from actual clients and legislative authorities, Wright gave free rein to his imagination, designing a future in which the architect ruled supreme [fig. 6] . Arguably, it took someone of his international stature and notoriously giant ego to attempt to resettle an entire nation.

“There is already no question that Wright is one of the great architects of all time,” wrote architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock in 1932 (an estimation with which Wright evidently concurred). 7 The architect’s reputation at this point rested on earlier achievements at the forefront of what was known as the Prairie Style, a Midwestern manifestation of the international Arts and Crafts

New York and other big cities were already being strangled by traffic. “If congestion is crucifixion now, what will congestion be within a few years?” asked Wright. “The motor car has just begun on the city.” 18 Both he and Le Corbusier were car lovers and accepted that the automobile was not about to disappear; it was the city that had to give way for the car. Le Corbusier proposed fast- and slow-moving lanes of traffic circulating smoothly around his towers along oneway routes situated sixteen feet (about five meters) or more above the ground; this arrangement would leave pedestrians free to access extensive playing fields and parks around the base of each tower. City dwellers would be insulated from the racket and fumes of traffic zooming past their windows in soundproof, hermetically sealed living spaces, air-conditioned to keep humidity and temperature at a comfortable level. Wright thought this plan preposterous: “Why deck or double-deck or triple-deck the city streets at a cost of billions of dollars, only to invite increase and meet inevitable defeat?” Better, he maintained, for those billions to be spent on more cars to facilitate the individual’s physical and psychological release from the centralized city: “A view of the horizon gives him the desire to go. If he has the means, he goes . . . he himself is the city. The city is going where he goes.” 19

“A Man Without a Country, Architecturally Speaking”

Wright described himself in 1932 as “a man without a country, architecturally speaking, at the present time,” at odds with modern architecture trends in both Europe and America. 20 Simmering in the background of his public exchange with Le Corbusier was resentment at the lionization of his rival at New York’s recently established Museum of Modern Art. Le Corbusier was beloved by the institution’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr Jr., and by Philip Johnson and HenryRussell Hitchcock, curators of the Museum’s inaugural architecture show, Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, which opened in February 1932 and ran for six weeks [fig. 12] . This landmark event and related publications presented the “International Style” of architecture—characterized by its reductive geometric forms—as a single, unified movement spearheaded by Europeans, notably Le Corbusier, Germans Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (former and current directors of the Bauhaus), and the Dutchman J. J. P. (Jacobus Johannes Pieter) Oud. The tail end of this International Style was represented by a somewhat eclectic range of thirty-seven architects from fifteen different countries, including the United States. As Johnson coolly explained in a letter to Oud, Wright was included “only from courtesy and in recognition of his past contributions.” 21 Hitchcock went further in the exhibition catalogue, stating that “American architecture need not develop entirely in the footsteps of her great individual genius [Wright]. A larger and a newer world calls. The day of the lone pioneer is past.” 22