Part I: Te Sanctifcation Experience Among African American Women in

Methodism

Te earliest African American women leaders tend to arise out of established Methodist circles. As the doctrine of sanctifcation became more widely taught in these groups, and experienced by individuals, the teachings spread to African American religious communities. While Wesley taught on sanctifying grace, his chosen successor John Fletcher (1729-1785) wrote on the Baptism of the Holy Spirit and the idea of a second work of grace. Fletcher’s writings especially infuenced other women, along with the early work of Madame Guyon (1648-1717). White women, such as Mary Bosanquent Fletcher (1739-1815), Hester Ann Roe Rogers (17561794), and Phoebe Palmer (1807-1874) broke out of traditional male roles in early Methodism, and their teachings would help pave the way for African American women to follow. While breaking down barriers of gender, class, and race were not easy, even within Methodist circles, the concept of sanctifcation provided an avenue for this to happen, which was not available in other Christian denominations.

Early image of Jarena Lee. (Image in the Public Domain)

Jarena Lee (February 11, 1783-February 3, 1864)

(African Methodist Episcopal Church)

Jarena Lee wrote Te Life and Religious Experience of Jarena Lee, A Coloured Lady, Giving an Account of Her Call to Preach the Gospel in 1836.7 Tis was the frst autobiography by an African American woman, and it speaks to her importance in understanding the religious experience of African American women.

While Jarena was born in 1783 to a free black family in Cape May, New Jersey, by the age of seven she was working as a live-in servant for a white family. Despite having no formal education, she taught herself how to write. By 1804, she had moved to Philadelphia, where she still continued in fnding work as a servant. At this time, she was exposed to the Gospel and attended religious services at Richard Allen’s African Methodist Episcopal Church.

About three months afer her conversion, Jarena records the account of her sanctifcation experience.

When I rose from my knees, there seemed a voice speaking to me, as I yet stood in a leaning posture“Ask for sanctifcation.” When to my surprise, I recollected that I had not even thought of it in my whole prayer. It would seem Satan had hidden the very object from my mind, for which I had purposely kneeled to pray. But when this voice whispered in my heart, saying, “Pray for sanctifcation,” I again bowed in the same place, at the same time, and said, “Lord sanctify my soul for Christ’s sake?” Tat very instant, as if lightning had darted through me, I sprang to my feet, and cried, “ Te Lord has sanctifed my soul!”

7 Te most easily accessed version of Jarena Lee’s autobiography is from a reprinted version found in: William L. Andrews edited 1986 book, Sisters of the Spirit: Tree Black Women’s Autobiographies of the Nineteenth Century. Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press.

Tere was none to hear this but the angels who stood around to witness my joy- and Satan, whose malice raged the more. Tat Satan was there, I knew; for no sooner had I cried out, “ Te Lord has sanctifed my soul,” than there seemed to be another voice behind me, saying, “No, it is too great a work to be done.” But another spirit said, “Bow down for the witness- I received it- thou art sanctifed!” Te frst I knew of myself afer that, I was standing in the yard with my hands spread out, and looking with my face toward heaven.

I now ran into the house and told them what had happened to me, when, as it were, a new rush of the same ecstasy came upon me, and caused me to feel as if I were in an ocean of light and bliss.8

By 1807, Jarena was feeling called to preach, but she was informed that women could not preach in the church. She wrote of this event and noted,

For as unseemly as it may appear now-a-days for a woman to preach, it should be remembered nothing is impossible with God. And why should it be thought impossible, heterodox, or improper for a woman to preach? seeing the Saviour died for the woman as well as the man.

If a man may preach, because the Saviour died for him, why not the woman? Seeing he died for her also. Is he not a whole Saviour, instead of a half one? As those who hold it wrong for a woman to preach, would seem to make it appear.

Did not Mary frst preach the risen Saviour, and is not the doctrine of the resurrection the very climax of

8 Andrews 1986: 34.

Christianity- hangs not all our hope on this, as argued by St. Paul? Ten did not Mary, a woman, preach the gospel? For she preached the resurrection of the crucifed Son of God.9

In 1811, Jarena married Joseph Lee, a preacher in the community of Snow Hill, outside of Philadelphia. Her husband also forbid her from preaching, and so she had two children and focused on her family. Afer only six years, Joseph died. Jarena asked Bishop Allen again in 1817 for a license to preach and she was again refused. In 1819, Jarena stepped into the pulpit at the Mother Bethel church in Philadelphia, when the preacher began to falter. Her preaching impacted the crowd and Bishop Allen publicly acknowledged her abilities. Unable to give her a formal license to preach, Allen named her an ofcial traveling exhorter. Jarena than began to preach all over the United States, including the South. She is credited with having travelled 2,325 miles, ofen by foot, and preaching 178 sermons during her lifetime.10 But in 1852, when the African Methodist Episcopal Church decided ofcially that women could not preach, she disappeared from ofcial church histories.

In her written account, Jarena focuses more on preaching as a woman than on her race, but in one place she noted,

…I had a call to preach at a place about thirty miles distant, among the Methodists, with whom I remained one week, and during the whole time, not a thought of my little son came into my mind; it was hid from me, lest I should have been diverted from the work I had to do, to look afer my son. Here by the instrumentality of a poor coloured woman, the Lord poured forth his spirit among the people. Tough as I

9 Andrews 1986: 36

10 Susan J. Hubert, “Testimony and Prophecy in the Life and Religious Experience of Jarena Lee.” Journal of Religious Tought, 54/54(2) (1998):49.

was told, there were lawyers, doctors, and magistrates present, to hear me speak, yet there was mourning and crying among sinners, for the Lord scattered fre among them of his own kindling. Te Lord gave his handmaiden power to speak for his great name, for he arrested the hearts of the people, and caused a shaking amongst the multitude, for God was in the midst.”11

Jarena mentions other women in her account, those who encouraged her, listened to her, and cared for her children when she travelled. What really comes out in her account is how the African American Church itself worked against African American women in having public ministry.

Excellent research by Frederick Knight of Morehouse College helps understand some of the trials of Jarena Lee’s fnal years.12 She died in relative poverty in Philadelphia in her 80s and indications show she struggled to survive as a “washerwoman” and through “begging”. Even the location of her remains are obscured, demonstrating some of the social problems ofen faced by African American women in American history. Nevertheless, Jarena Lee remains the author of the frst autobiography of an African American woman, and the frst female preacher of the African Methodist Episcopal denomination.

11 Andrews 1986: 45-46

12 Frederick Knight, “ Te Many Names for Jarena Lee.” Te Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 141(1) (January 2017):59-68.

Image of Zilpha Elaw. (Image in the Public Domain)

Zilpha Elaw (c. 1790-1873)

(Primitive Methodists)

Zilpha Elaw was born to a family of freed African Americans who were deeply religious. Born in Pennsylvania, she was sent to live with a Quaker family when she was about 12 years old, due to the death of her mother.13 Shortly afer her move, her father also passed away. Zilpha was not inclined toward the Quaker style of worship, and eventually began attending Methodist services. Her conversion came from a vision she had of Jesus:

As I was milking the cow and singing, I turned my head, and saw a tall fgure approaching, who came and stood by me. He had long hair, which parted in the front and came down on his shoulders; he wore a long white robe down to the feet; and as he stood with open arms and smiled upon me, he disappeared. I might have tried to imagine, or persuade myself, perhaps, that it had been a vision presented merely to the eye of my mind; but, the beast of the stall gave forth her evidence to the reality of the heavenly appearance; for she turned her head and looked round as I did; and when she saw, she bowed her knees and cowered down upon the ground. I was overwhelmed with astonishment at the sight, but the thing was certain and beyond all doubt. I write as before God and Christ, and declare, as I shall give an account to my Judge at the great day, that every thing I have written in this little book, has been written with conscientious veracity and scrupulous adherence to truth.”14

13 Te most easily accessed version of Zilpha Elaw’s autobiography is from a reprinted version found in: William L. Andrews edited 1986 book, Sisters of the Spirit: Tree Black Women’s Autobiographies of the Nineteenth Century. Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press. 14 Andrews 1986:56-57.

In 1810, Zilpha married Joseph Elaw, who was not a committed Christian. He attempted to get Zilpha to leave the Methodists with music and dancing, but Zilpha rejected worldly pleasures. Afer moving to New Jersey, Zilpha was able to attend a camp meeting in 1817, which she described for her British readers,

In order to form a camp-meeting, when the place and time of meeting has been extensively published, each family takes its own tent and all things necessary for lodgings, with seats, provisions and servants; and with wagons and other vehicles repair to the destined spot, which is generally some wildly rural and wooded retreat in the back grounds of the interior: hundreds of families, and thousands of persons, are seen pressing to the place from all quarters; the meeting usually continues for a week or more: a large circular enclosure of brushwood is formed; immediately inside of which the tents are pitched, and the space at the centre is appropriated to the worship of God, the minister’s stand being on one side, and generally on a somewhat rising ground. It is a scafold constructed of boards, and surrounded with a fence of rails.

In the space before the platform, seats are placed sufcient to seat four or fve thousand persons; and at night the woods are illuminated; there are generally four large mounds of earth constructed, and on them large piles of pine knots are collected and ignited, which make a wonderful blaze and burn a long time; there are also candles and lamps hung about in the trees, together with a light in every tent, and the minister’s stand is brilliantly lighted up; so that the illumination attendant upon a camp-meeting, is a magnifcently solemn scene. Te worship commences in the morning before sunrise; the watchmen proceed round the enclosure, blowing with trumpets to awaken every inhabitant of this City of the Lord;

then they proceed again round the camp, to summon the inmates of every tent to their family devotions; afer which they partake of breakfast, and are again summoned by sound of trumpet to public prayer meeting at the altar which is placed in front of the preaching stand.15

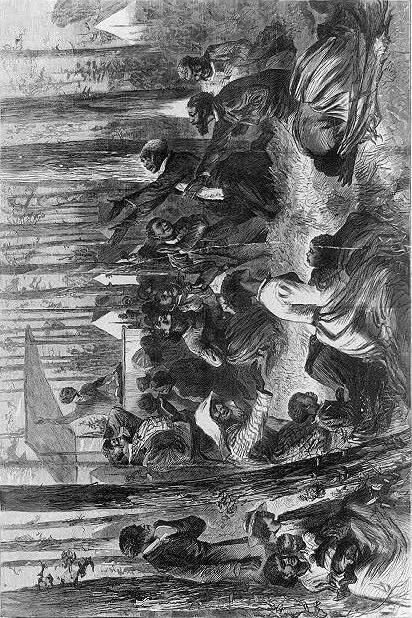

Zilpah goes on to describe more detail of a camp meeting, but more importantly, she notes her sanctifcation experience occurred at such a meeting,

I, for one, have great reason to thank God for the refreshing seasons of his mighty grace, which have accompanied these great meetings of his saints in the wilderness. It was at one of these meetings that God was pleased to separate my soul unto Himself, to sanctify me as a vessel designed for honour, made meet for the master’s use. Whether I was in the body, or whether I was out of the body, on that auspicious day, I cannot say; but this I do know, that at the conclusion of a most powerful sermon delivered by one of the ministers from the platform, and while the congregation were in prayer, I became so overpowered with the presence of God, that I sank down upon the ground, and laid there for a considerable time; and while I was thus prostrate on the earth, my spirit seemed to ascend up into the clear circle of the sun’s disc; and, surrounded and engulphed in the glorious efulgence of his rays, I distinctly heard a voice speak unto me, which said, “Now thou art sanctifed; and I will show thee what thou must do.” I saw no personal appearance while in this stupendous elevation, but I discerned bodies of resplendent light; nor did I appear to be in this world at all, but immediately far above those spreading trees, beneath whose shady and verdant bowers I

15 Andrews 1986:64-65.

Early Engraving of an African American Camp Meeting. (Image in the Public Domain)

was then reclined. When I recovered from the trance or ecstasy into which I had fallen, the frst thing I observed was, that hundreds of persons were standing around me weeping; and I clearly saw by the light of the Holy Ghost, that my heart and soul were rendered completely spotless- as clean as a sheet of white paper, and I felt as pure as if I had never sinned in all my life…16

It was afer this experience that Zilpha began to pray in public and speak to individuals more about salvation. When her sister was dying, Zilpha was called to her bedside and her sister had a vision of Jesus with the message to Zilpha to preach the gospel. Even then, Zilpha had doubts, writing, “I could not at the time imagine it possible that God should select and appoint so poor and ignorant a creature as myself to be his messenger, to bear the good tidings of the gospel to the children of men.”17 But afer a serious illness and a personal confrmation of her call, Zilpha attended another camp meeting, where in the power of the Holy Spirit, Zilpha began preaching. In 1823, Zilpha’s husband died afer a deathbed repentance. With the help of some Quakers, she opened a school to teach African American children. She noted some of the issues of race when she wrote,

Te pride of a white skin is a bauble of great value with many in some parts of the United States, who readily sacrifce their intelligence to their prejudices, and possess more knowledge than wisdom. Te Almighty accounts not the black races of man either in order of nature or spiritual capacity as inferior to the white; for He bestows his Holy Spirit on, and dwells in them as readily as in persons of whiter complexion: the Ethiopian eunuch was adopted as a son and heir of

16 Andrews 1986: 66-67.

17 Andrews 1986: 75.

God; and when Ethiopia shall stretch forth her hands unto him [Ps. 68:31], their submission and worship will be graciously accepted. Tis prejudice was far less prevalent in that part of the country where I resided in my infancy; for when a child, I was not prohibited from any school on account of the colour of my skin. Oh! Tat men would outgrow their nursery prejudices and learn that “God hath made of one blood all the nations of men that dwell upon all the face on the earth.” Acts 17:26.18

Zilpha continued to preach, travelling to New York and even down into the slave states, with the knowledge that she could have been arrested and sold into slavery, just because of the color of her skin. She continued preaching in Virginia, and noted the astonishment which greeted her as a black woman preacher. She then preached extensively in New England among camp meetings and in pulpits with African American and white audiences. She spoke in Boston, Lynn, New York, Nantucket, and even in Bangor, Portland, and Bath, Maine.

In 1840, Zilpha lef the United States for England. Tere she spent at least four years preaching in many places, and ofen among the Primitive Methodists. Zilpha would ultimately publish an account of her life while she was living in England. Te work was titled, Memoirs of the Life, Religious Experience, Ministerial Travels and Labours of Mrs. Zilpha Elaw, an American Female of Colour; Together with Some Account of the Great Religious Revivals in America and was published in 1846.

It is not clear if Zilpha returned to the United States, but evidence seems to show she married Ralph Bressey Shum in East London in 1850. It is believed that she continued preaching until

18 Andrews 1986:85-86.

her death. Registers show she was buried in 1873 in Tower Hamlets Cemetery in London, England.

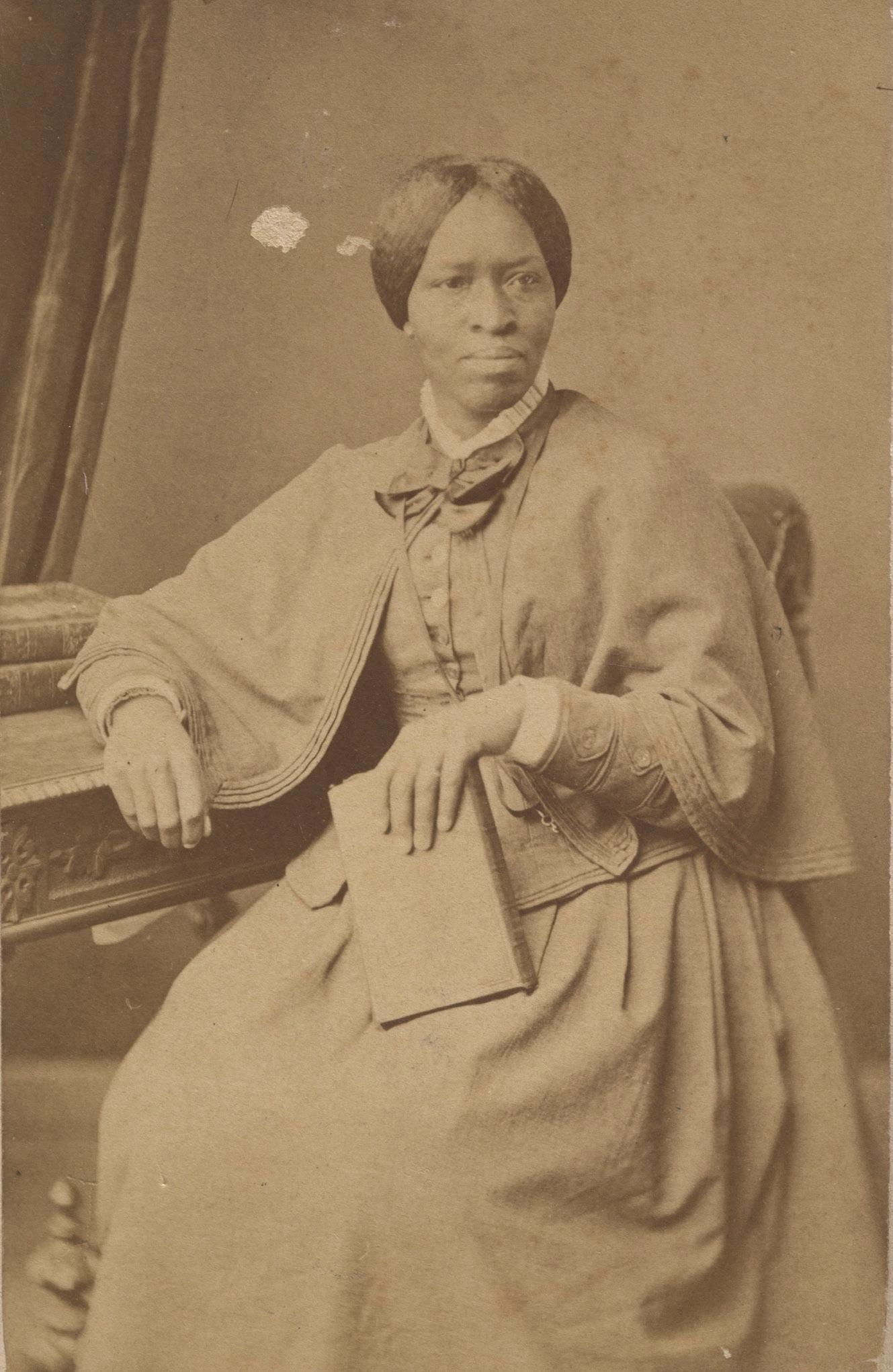

Photo of Julia Foote. (Image in the Public Domain)

Julia Foote (May 21, 1823-November 1901) (African Methodist Episcopal Zion)

Julia Foote was born to former slaves in 1823.19 Her father had been born free, but was stolen and enslaved. He ended up working as a teamster moving goods by horse and wagon. Julia’s mother had been born a slave in New York and had been viciously whipped by an owner who had wanted her to submit to him, and she had told the wife. She was then sold to various owners. Julia’s father had purchased his own freedom and then that of his wife and his oldest child. Julia was the fourth child and was born free. Julia’s family was religious and belonged to the Methodist Episcopal Church, which kept African Americans in one area in the balcony and required them to take communion afer white members. As Julia recounted,

One day my mother and another colored sister waited until all the white people had, as they thought, been served, when they started for the communion table. Just as they reached the lower door, two of the poorer class of white folks arose to go to the table. At this, a mother in Israel caught hold of my mother’s dress and said to her, “Don’t you know better than to go to the table when white folks are there?” Ah! She did know better than to do such a thing purposely. Tis was one of the fruits of slavery. Although professing to love the same God, members of the same church, and expecting to fnd the same heaven at last, they could not partake of the Lord’s Supper until the lowest of the whites had been served. Were they led by the Holy Spirit? Who shall say? Te Spirit of Truth can never be mistaken, nor can he inspire anything unholy. How many at the present day profess great spirituality, and

19 A free download of Julia Foote’s book, A Brand Plucked From the Fire: An Autobiographical Sketch, 2019 Wilmore, KY: First Fruits Press can be found at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/frstfruitsheritagematerial/169/

even holiness, and yet are deluded by a spirit of error, which leads them to say to the poor and colored ones among them, “Stand back a little- I am holier than thou.”20

Julia began the process of learning to read from her father. No one else in the family could read, and he had very limited knowledge, although he would read from the Bible by spelling out words. So, he taught her the alphabet. At ten, Julia was sent to live in the country, and she was able to go to school. At about twelve years old, Julia returned to her family to help care for younger children and the family moved to Albany and joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Tis led to her conversion at 15 years of age. Also, around this time, a childhood accident led to Julia losing her sight in one eye. Julia entered a period of misery and did not understand how to break through this feeling. Finally, she heard an older couple speak about sanctifcation, and through speaking with the couple who showed her various scriptures, Julia had a sanctifcation experience. Julia wrote,

Te second day afer that pilgrim’s visit, while waiting on the Lord, my desire was granted, through faith in my precious Saviour. Te glory of God seemed almost to prostrate me to the foor. Tere was, indeed, a weight of glory resting upon me. I said with all my heart, “ Tis is the way I long have sought, and mourned because I found it not.” Glory to the Father! Glory to the Son! And glory to the Holy Ghost! Who hath plucked me as a brand from the burning, and sealed me unto eternal life. I no longer hoped for glory, but I had the full assurance of it.21

20 Foote 2019 reprint: 11-12.

21 Foote 2019 reprint: 43.

At 16, Julia married George Tillman and the young couple moved to Boston. As her ministry and outreach continued, especially while her husband was a sailor on extended trips, Julia experienced a vision telling her to preach,

I took all my doubts and fear to the Lord in prayer, when, what seemed to be an angel, made his appearance. In his hand was a scroll, on which were these words: “ Tee have I chosen to preach my Gospel without delay.” Te moment my eyes saw it, it appeared to be printed on my heart. Te angel was gone in an instant, and I, in agony, cried out, “Lord, I cannot do it!” It was eleven o’clock in the morning, yet everything grew dark as night. Te darkness was so great that I feared to stir.22

Julia makes clear in her account that until this command, she was opposed to women preaching in the church. She was aware of the difculties that would need to be overcome and the opposition she would face, even from her husband and family. Two months afer the frst visit she experienced a second angelic appearance directing her “to go in my name and warn the people of their sins,”23 and this time she submitted to God’s will, but before long fear took hold of her again. Afer a short time, she had a third encounter, …while engaged in fervent prayer, the same supernatural presence came to me once more and took me by the hand. At that moment I became lost to everything in this world. Te angel led me to a place where there was a large tree, the branches of which seemed to extend either way beyond sight. Beneath it sat, as I thought, God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, besides many others, whom I thought were angels. I was led before them: they looked me

22 Foote 2019 reprint: 66.

23 Foote 2019 reprint: 68.

over from head to foot, but said nothing. Finally, the Father said to me: “Before these people make your choice, whether you will obey me or go from this place to eternal misery and pain.” I answered not a word. He then took me by the hand to lead me, as I thought, to hell, when I cried out, “I will obey thee, Lord!” He then pointed my hand in diferent directions, and asked if I would go there. I replied, “Yes, Lord.” He then led me, all the others following, till he came to a place where there was a great quantity of water, which looked like silver, where we made a halt. My hand was given to Christ, who led me into the water and stripped me of my clothing, which at once vanished from sight. Christ then appeared to wash me, the water feeling quite warm.

During this operation, all the others stood on the bank, looking on in profound silence. When the washing was ended, the sweetest music I had ever heard greeted my ears. We walked to the shore, where an angel stood with a clean, white robe, which the Father at once put on me. In an instant I appeared to be changed into an angel. Te whole company looked at me with delight, and began to make a noise which I called shouting. We all marched back with music. When we reached the tree to which the angel frst led me, it hung full of fruit, which I had not seen before. Te Holy Ghost plucked some and gave me, and the rest helped themselves. We sat down and ate the fruit, which had a taste like nothing I had ever tasted before. When we had fnished, we all arose and gave another shout. Ten God the Father said to me: “You are now prepared, and must go where I have commanded you.” I replied, “If I go, they will not believe me.” Christ then appeared to write something with a golden pen and golden ink upon golden paper. Ten he rolled it up, and said to me: “Put this in your bosom, and

wherever you go, show it, and they will know that I have sent you to proclaim salvation to all.” He then put it into my bosom, and they all went with me to a bright, shining gate, singing and shouting. Here they embraced me, and I found myself once more on earth.24

Julia commenced her work at this time, even though she immediately began to face opposition from within the African Methodist Episcopal Church of which she was a member. Her membership from the church was revoked because of her refusal to stop preaching. She appealed to the Conference, but recorded, “My letter was slightingly noticed, and then thrown under the table. Why should they notice it? It was only the grievance of a woman, and there was not justice meted out to women in those days. Even ministers of Christ did not feel that women had any rights which they were bound to respect.”25 In response to those who spoke against women preaching, Julia responded, “We are sometimes told that if a woman pretends to a Divine call, and thereon grounds the right to plead the cause of a crucifed Redeemer in public, she will be believed when she shows credentials from heaven; that is, when she works a miracle. If it be necessary to prove one’s right to preach the Gospel, I ask my brethren to show me their credentials, or I can not believe in the propriety of their ministry.”26

In her attendance of the Conference in Philadelphia, Julia also met “three sisters” who also felt called to preach, but had been denied, and so the four of them set up a meeting in Philadelphia right afer the Conference. Te women (one lef them for fear of being removed from the church) ran the meetings and closed with a love-feast, which created some controversy. From there she

24 Foote 2019 reprint: 69-71.

25 Foote 2019 reprint: 76.

26 Foote 2019 reprint: 78-79.

returned to her family in New York and spoke frequently in houses, but was ofen denied the right to speak in churches. She also faced opposition, especially in travelling because of the color of her skin. In one case she noted while going by boat from New York to Boston, the boat was delayed due to technical problems and she had to sit on deck and caught a severe cold because African Americans were not allowed in the sheltered cabin unless they were servants. In yet another case she noted that she was delayed for four days on a trip by stage coach, despite having paid for a ticket, because African Americans could not travel on a coach if any of the white passengers objected.

While speaking and traveling in Ohio, Julia received word of her husband’s death while he was at sea. She continued travelling and speaking, and in one case was invited to speak in Baltimore at an African Methodist Episcopal Church. Since this was about 1849 and Maryland was a slave state, Julia noted,

Upon our arrival there we were closely questioned as to our freedom, and carefully examined for marks on our person by which to identify us if we should prove to be runaways. While there, a daughter of the lady with whom we boarded ran away from her self-styled master. He came, with others, to her mother’s house at midnight, burst in the door without ceremony, and swore the girl was hid in the house, and that he would have her, dead or alive. Tey repeated this for several nights. Tey ofen came to our bed and held their light in our faces, to see if the one for whom they were looking was not with us. Te mother was, of course, in great distress. I believe they never recovered the girl. Tank the dear Lord we do not have to sufer such indignities now, though the monster, Slavery, is not yet dead in all its forms.27

27 Foote 2019 reprint: 98-99.

In another case, Julia refused to speak to a group of white Methodists who would not permit African Americans to attend, and this attitude in turn led to a white Methodist congregation in Zanesville, Ohio opening their church to African Americans for the frst time in 1851.

Julia published an account of her life in 1879, entitled A Brand Plucked From the Fire: An Autobiographical Sketch. In one chapter, she specifcally addressed women when she wrote, Sisters, shall not you and I unite with the heavenly host in the grand chorus? If so, you will not let what man may say or do, keep you from doing the will of the Lord or using the gifs you have for the good of others. How much easier to bear the reproach of men than to live at a distance from God. Be not kept in bondage by those who say, “We sufer not a woman to teach,” thus quoting Paul’s words [1 Cor. 14:34], but not rightly applying them. What though we are called to pass through deep waters, so our anchor is cast within the veil, both sure and steadfast? Blessed experience! I have had to weep because this was not my constant experience. At times, a cloud of heaviness has covered my mind, and disobedience has caused me to lose the clear witness of perfect love… Not till the day of Pentecost did Christ’s chosen ones see clearly, or have their understandings opened; and nothing short of a full baptism of the Spirit will dispel our unbelief. Without this, we are but babes- all our lives are ofen carried away by our carnal natures and kept in bondage; whereas, if we are wholly saved and live under the full sanctifying infuence of the Holy Ghost, we cannot be tossed about with every wind, but like an iron pillar or a house built upon a rock prove immovable. Our minds will then be fully illuminated,

our hearts purifed, and our souls flled with the pure love of God, bringing forth fruit to his glory.28

In this same vein, the point and purpose of Julia Foote’s writing was to teach and point others toward the sanctifcation experience, and her book should be read in that light.

In 1894, Julia Foote became the frst ordained woman deacon of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and in 1900 she was the second woman named an elder. She died in 1901 and was buried in an unmarked grave in the family plot of Bishop Alexander Walters in Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn.

28 Foote 2019 reprint: 112-116.

Photo of Amanda Smith. (Image in the Public Domain)

Amanda Smith (January 23, 1837-February 25, 1915)

(Methodist Episcopal Church)

Amanda Smith was born in Long Green, Maryland on January 23, 1837 to Samuel and Mariam Matthews Berry.29 She was born in slavery to parents who were owned by diferent slaveholders on adjoining farms. Amanda’s father was allowed to make extra money with an aim to buying his freedom. So, at nights and in his free time, he would make things to sell and work additional time during periods of harvest, sometime working till one or two in the morning. Afer buying his own freedom, he set to work to buy the freedom of his wife and children, fve of who were born into slavery (the family ended up with thirteen children in total). Amanda was the oldest girl in the family.

Amanda’s mother had attended a Methodist Camp Meeting with her young mistress, who went with some friends out of curiosity. Te young white lady became saved and desired to go to other services, but her family prevented it. Amanda’s mother and grandmother provided some of her little contact with others convinced of the message of sanctifcation. Te young lady developed typhoid fever, and on her death-bed repeatedly asked her parents to free Amanda’s mother and siblings. Amanda noted that when her father paid for their freedom, she had been too young to experience the real trials of slavery, but she also wrote, “I ofen say to people that I have a right to shout more than some folks; I

29 A reprint of the account of Amanda Smith can be found for free: Mrs. Amanda Smith, An Autobiography: Te Story of the Lord’s Dealings with Mrs. Amanda Smith, the Colored Evangelist: Containing an Account of her Life Work of Faith, and Her Travels in America, England, Ireland, Scotland, India, and Africa, as an Independent Missionary. Chicago, IL: Meyer and Brother, 1893. Free electronic access at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/ frstfruitsheritagematerial/139/

have been bought twice, and set free twice, and so I feel I have a good right to shout. Hallelujah!”30

Afer the family was free, Amanda’s father wished to visit a brother up north who had run away years before. Maryland law at the time held that even free blacks who lef the state for ten days would be considered no longer a resident and could be captured and sold. Amanda’s father took more than ten days for the visit, and so the family felt forced from fear to leave Maryland, while her mother’s family remained enslaved. Both Amanda’s mother and father had learned to read, and so she was sent to a small school in Pennsylvania, where she was educated, although her education was sporadic.

At thirteen, while living and working in the house of a Mrs. Latimer, Amanda Smith was saved in a revival held in a local white Methodist church. She still battled with lots of spiritual doubts and also due to the impact of prejudice. At the same time, her father’s house was an active station on the Underground Railroad and they were involved in helping slaves escaping from the South. Amanda recounts a number of the close calls they had in being caught by white slave catchers at the time and her parents’ bravery in helping runaway slaves escape capture.

In 1854, Amanda married C. Devine, her frst husband. Tey had one child who died, and a daughter, Maze, who lived in Baltimore. Amanda became very ill in 1855 and was considered close to death, when she had a vision,

I saw on the foot of my bed a most beautiful angel. It stood on one foot with wings spread, looking me in the face and motioning me with the hand; it said “Go back,” three times, “Go back, Go back, Go back.”

30 Smith 1893: 22.

Ten, it seemed, I went to a great Camp Meeting and there seemed to be thousands of people, and I was to preach and the platform I had to stand on was high above the people. It seemed it was erected between two trees, but near the tops. How I got on it I don’t know, but I was on this platform with a large Bible opened and I was preaching from these words:- “And I if I be lifed up will draw all men unto me.” O, how I preached, and the people were slain right and lef. I suppose I was in this vision about two hours.31

When Amanda came out of the vision her sickness began to pass and she recommitted herself to living a Christian life. But she continued to be plagued by doubts about her salvation, and she entered into a major time of prayer and trying to struggle against the voice of the Devil laying out her doubts. Finally, in 1856, she noted afer a third struggle in prayer:

Ten in my desperation I looked up and said, “O, Lord, if Tou wilt help me I will believe Tee,” and in the act of telling God I would, I did. O, the peace and joy that fooded my soul! Te burden rolled away; I felt it when it lef me, and a food of light and joy swept through my soul such as I had never known before. I said, “Why, Lord, I do believe this is just what I have been asking for,” and down came another food of light and peace. And I said again, “Why, Lord, I do believe this is what I have asked Tee for.” Ten I sprang to my feet, all around me was light. I was new. I looked at my hands, they looked new; I took hold of myself and said, “Why, I am new, I am new all over.” I clapped my hands: I ran out of the cellar, I walked up and down the kitchen foor. Praise the Lord! Tere seemed to be a halo of light all over me; the change was so real and so thorough that I have ofen said that

31 Smith 1893: 42-43.

if I had been as black as ink or as green as grass or as white as snow, I would not have been frightened.32

In the early 1860’s during the Civil War, Amanda’s husband enlisted with the army and went South to fght, and never returned. So, afer a few years of domestic service in Philadelphia, Amanda married James Smith, a local preacher for the African Methodist Episcopal Church. During the years she did not have a husband, she was in domestic service and had to board her young daughter in other houses. Tis was part of her decision to marry again, but the marriage immediately encountered problems, as Smith was not given an appointment and Amanda had to return to domestic service as a cook and washerwoman. To make matters worse, the couple’s newborn daughter passed away. In 1865 the couple moved to New York, and while things did not improve, Amanda did frst hear of the idea of sanctifcation.

During her time in New York, another baby died, and she became reduced to the status of a washerwoman, taking in laundry, while her husband struggled with a poor-paying job in a hotel. When things were at their lowest in 1868, Amanda heard a voice from God telling her to go to the Green Street Church and hear John Inskip. Despite temptations to go to other churches and sheer exhaustion from her work, Amanda made it to the Green Street Church and sat close to the door, as she was the only African American in the white church. Inskip preached on the teaching of sanctifcation. While Amanda felt the experience of sanctifcation, she resisted the urge to shout out in the white congregation, and so she began doubting her experience. As she wrote later,

Somehow I always had a fear of white people- that is, I was not afraid of them in the sense of them doing me harm, or anything of that kind- but a kind of fear

32 Smith 1893: 47.

because they were white, and were there, and I was black and was here! But that morning on Green street, as I stood on my feet trembling, I heard these words distinctly. Tey seemed to come from the northeast corner of the church, slowly, but clearly: “ Tere is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female, for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.” (Galatians 3:28) I never understood that text before. But now the Holy Ghost had made it clear to me. And as I looked at white people that I had always seemed afraid of, now they looked so small. Te great mountain had become a mole-hill.33

James Smith died shortly afer in 1869, leaving Amanda as a widow again. By November of 1869, Amanda was doing extensive work among the African American community, especially in New York and New Jersey.

In commenting on if she had ever wished she were white, Amanda Smith wrote:

No, we who are the royal black are very well satisfed with His gif to us in this substantial color. I, for one, praise Him for what He has given me, although at times it is very inconvenient. For example: When on my way to California last January, a year ago, if I had been white I could have stopped at a hotel, but being black, though a lone woman, I was obliged to stay all night in the waiting room at Austin, Texas, though I arrived at ten P.M.: and many times when in Philadelphia, or New York, or Baltimore, or almost anywhere else except in grand historic Boston, I could not go in and have a cup of tea or a dinner at a hotel or restaurant. Tere may be places in these cities where colored people may be accommodated, but generally they are proscribed, and that sometimes makes it very

33 Smith 1893: 80.

inconvenient. I could pay the price- yes, that is all right; I know how to behave- yes, that is all right; I may have on my very best dress so that I look elegantyes, that is all right; I am known as a Christian ladyyes, that is all right; I will occupy but one chair; I will touch no person’s plate or fork- yes, that is all right; but you are black! Now, to say that being black did not make it inconvenient for us ofen, would not be true; but belonging to royal stock, as we do, we propose braving this inconvenience for the present, and pass on into the great big future where all these little things will be lost because of their absolute smallness! May the Lord send the future to meet us! Amen.34

By 1870, Amanda Smith indicates she once again received a call to preach. She had attended many camp meetings, including a number of the Holiness camp meetings, her frst being in Oakington, Maryland in 1870. She followed up by attending the camp meeting at Sing Sing in New York, Round Lake, Kennebunk, and Wesley Grove on Martha’s Vineyard. Each time she was able to share her story and become more and more comfortable sharing with white people. She also became more open to following the leading of the Holy Spirit. She encountered both prejudice, but also great acceptance, among the Holiness people in these meetings.

Amanda Smith managed to attend some of Phoebe Palmer’s Tuesday meetings, as well as hearing Sarah Smiley speak, both important Holiness fgures. She also became friends with Hannah Whitall Smith and attended her meetings as well. Ofen, she recounts a great deal of fear about how she would be received, and she did encounter negative remarks from some due to her race, but she was ofen welcomed by the speakers themselves and encouraged ofen to sing at these meetings as well.

34 Smith 1893: 117-118.

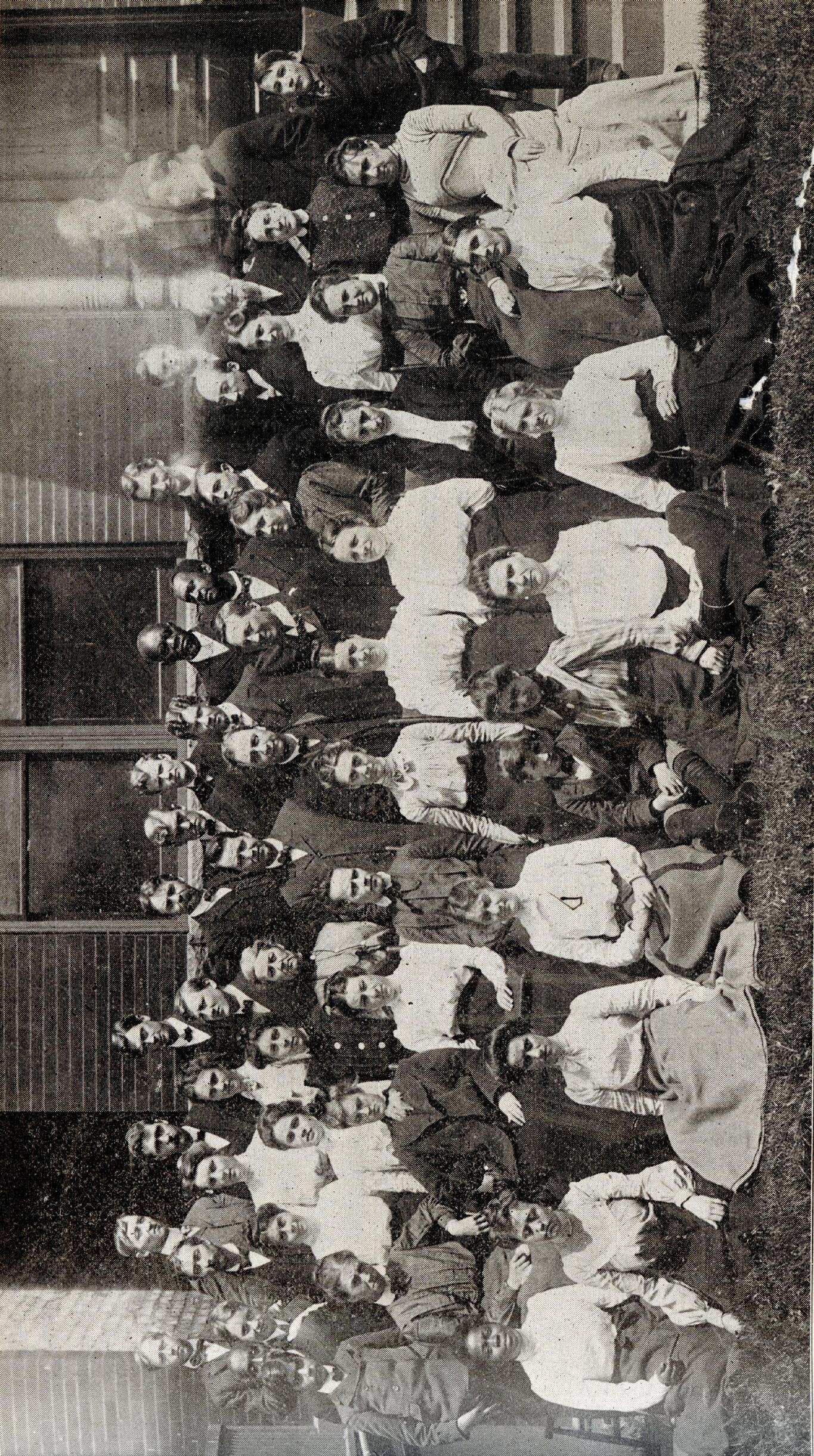

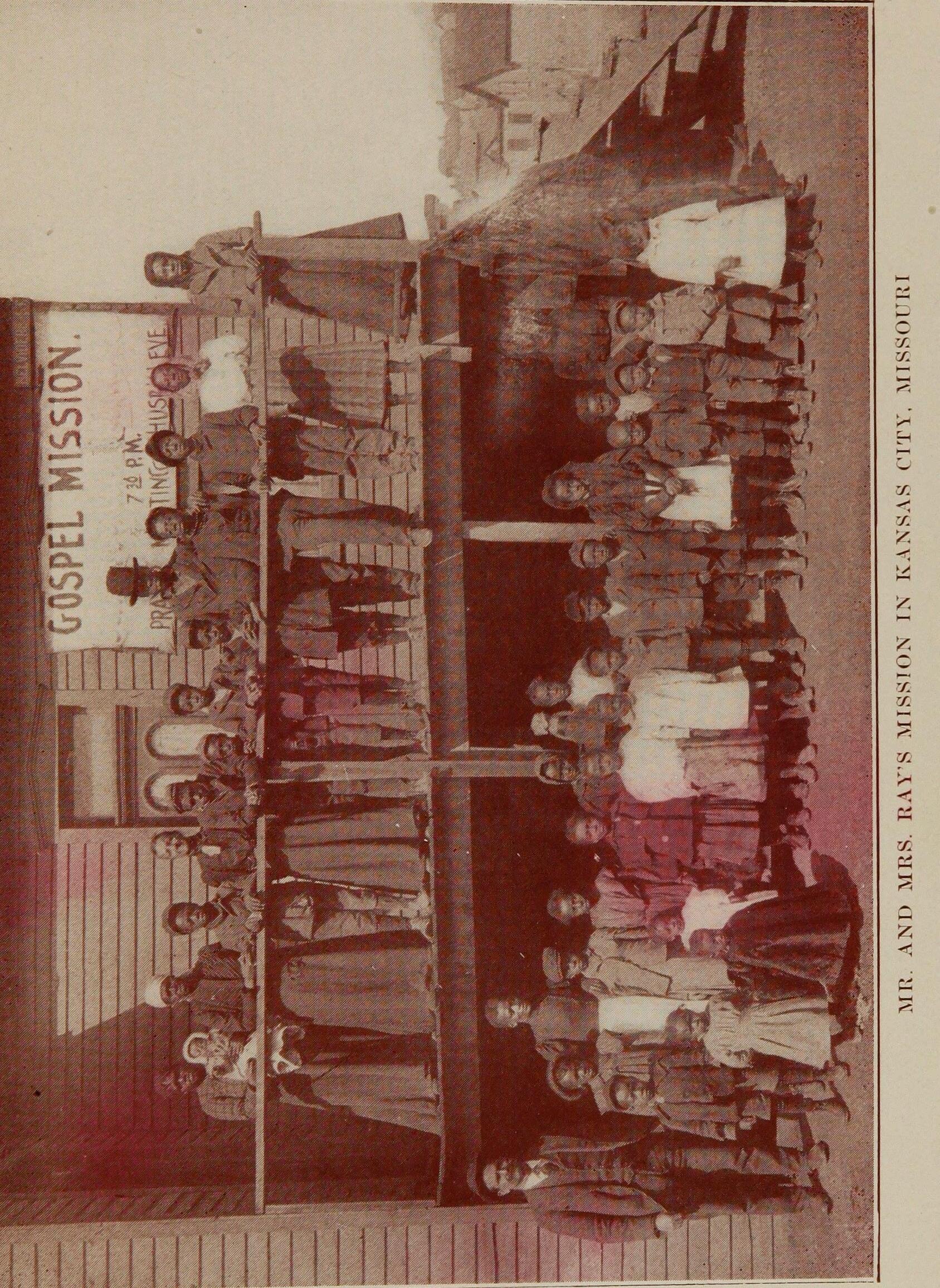

(Image courtesy of the Church of the Nazarene Archives.)

Iowa with White Leaders of the Christian Holiness Association.

Amanda Smith at a Camp Meeting in

When there was to be a national camp meeting in Knoxville, Tennessee, the Holiness leaders were concerned about her attending in the South. As she was struggling with determining if she should go, she wrote,

Just as I went to get up from my knees, a suggestion like this came:

“You know the Kuklux are down there, and they might kill you.”

Ten I knelt down again, and thought it all over; and I said, “Lord, if being a martyr for Tee would glorify Tee, all right; but then, just to go down there and be butchered by wicked men for their own gratifcation, without any reference to Ty glory, I’m not willing. And now, Lord, help me. If Tou dost want me to do this, even then, give me the grace and enable me to do it.

Ten these words came: “My grace is sufcient for thee.” And I said, “All right,” and got up.35

Along with this request, Amanda had told God she needed an almost impossible $50.00 to go, and by the end of the week, someone had given her $50.00 without even knowing of her prayer. She went on to be a part of the camp meeting in Knoxville, even in the presence of racial prejudice.

While she had thought about mission to Africa earlier in her life, she felt that the best she could do would be to raise her surviving daughter to be a missionary someday. In July of 1878, Amanda lef for England for three months, but God revealed she was to stay longer. She spoke at the Keswick Convention and went to the Broadlands Conference with Lord and Lady Mount Temple.

35 Smith 1893: 207.

She was invited to Scotland. On a trip to Eastbourne in England, Mrs. Charles Boardman wrote to Amanda telling her that Lucy Drake was returning to India and would like to see her. Lucy Drake was a pioneering Holiness missionary to India who went to work in Bassim supported by Dr. Cullis of Boston. Lucy Drake told Amanda that she felt God was calling Amanda to India and she had already raised the money. Amanda was able to travel to India through Paris, Italy, and Egypt. She saw wonders of the world from Rome to the pyramids of Giza, which she never imagined a slave girl from America would ever have a chance to see.

In November of 1879, Amanda arrived in India in the city of Bombay, where Jennie Frow showed her around before returning to her work. Jennie Frow would become Jennie Fuller, a major missionary fgure for the Christian and Missionary Alliance in India. Amanda Smith travelled around India and Burma, recording a good description of early Holiness mission work there, and she sang and spoke in the various places she visited. Amanda returned to England in June of 1881.

Te following year, in January of 1882, Amanda set sail again, but this time to Africa. Afer a stop in the Canary Islands, she arrived in Sierra Leone and travelled on to Liberia. Here she spent time with B.Y. Paine, his sister, Patsy Paine and her family, early African American missionaries to Liberia. In addition, she visited mission work and spoke at meetings. She also travelled to Cape Palmas in Liberia with the well-known Holiness Methodist missionary bishop, William Taylor. She remained in this area, speaking and teaching for eight years, and her autobiography contains a wonderful account of the life and culture among the people of Liberia in its early history. Amanda lef Sierra Leone in November of 1890. It had been twelve years since she had lef the United States for a three-month trip to England.

On her return to the United States, Amanda Smith published her autobiography in 1893, entitled An Autobiography, Te Story of the Lord’s Dealing with Mrs. Amanda Smith, the Colored Evangelist Containing an Account of her Life, Work of Faith, and Her Travels in America, England, Ireland, Scotland, India, and Africa, as An Independent Missionary. She continued preaching and speaking, and with the proceeds of her book and gifs from friends in 1899, she opened the Amanda Smith Orphanage and Industrial Home for Abandoned and Destitute Colored Children in a suburb of Chicago. Due to various problems the home closed its doors in 1918, two years afer Amanda Smith passed away on February 24, 1915.

Part II: Te Experience of African American Women in Holiness Groups

As the teachings on sanctifcation and holiness began to take root within Methodist circles, opposition began to arise, especially from those with administrative or ecclesiastical authority. In the face of this opposition, many Holiness people took up the position as “Come Outers”, a movement which encouraged truly holy people to leave and remove themselves from existing denominations which were considered defled by sin and teaching doctrines contrary to scripture. Groups began to form, which became denominations: the Free Methodist Church, the Wesleyan Church, the Christian and Missionary Alliance, the Church of God (Anderson) and other smaller groups such as the United Holy Church of America and Christ Holy Sanctifed Church, which were African American groups. On the most radical edge was the Metropolitan Church Association.

While there were Holiness people who remained within their denominations, especially in Methodist groups, it was not uncommon for some sanctifed people to be forced out of their denominational homes, especially among the Baptists. African American women were a part of all of these various movements. Some like Roxy Turner, Emma Elizabeth Craig, and Sarah King were involved in forming their own independent organizations, some of which would later become Pentecostal. Others, such as Emma Ray, Susan Fogg, Eliza Suggs, Priscilla Wimbush, and Irene Blyden Taylor were part of white Holiness organizations, and they sought to work within the boundaries of these groups. However, the message of sanctifcation continued to provide them an exceptional access to leadership and ministry within these organizations despite gender and race.

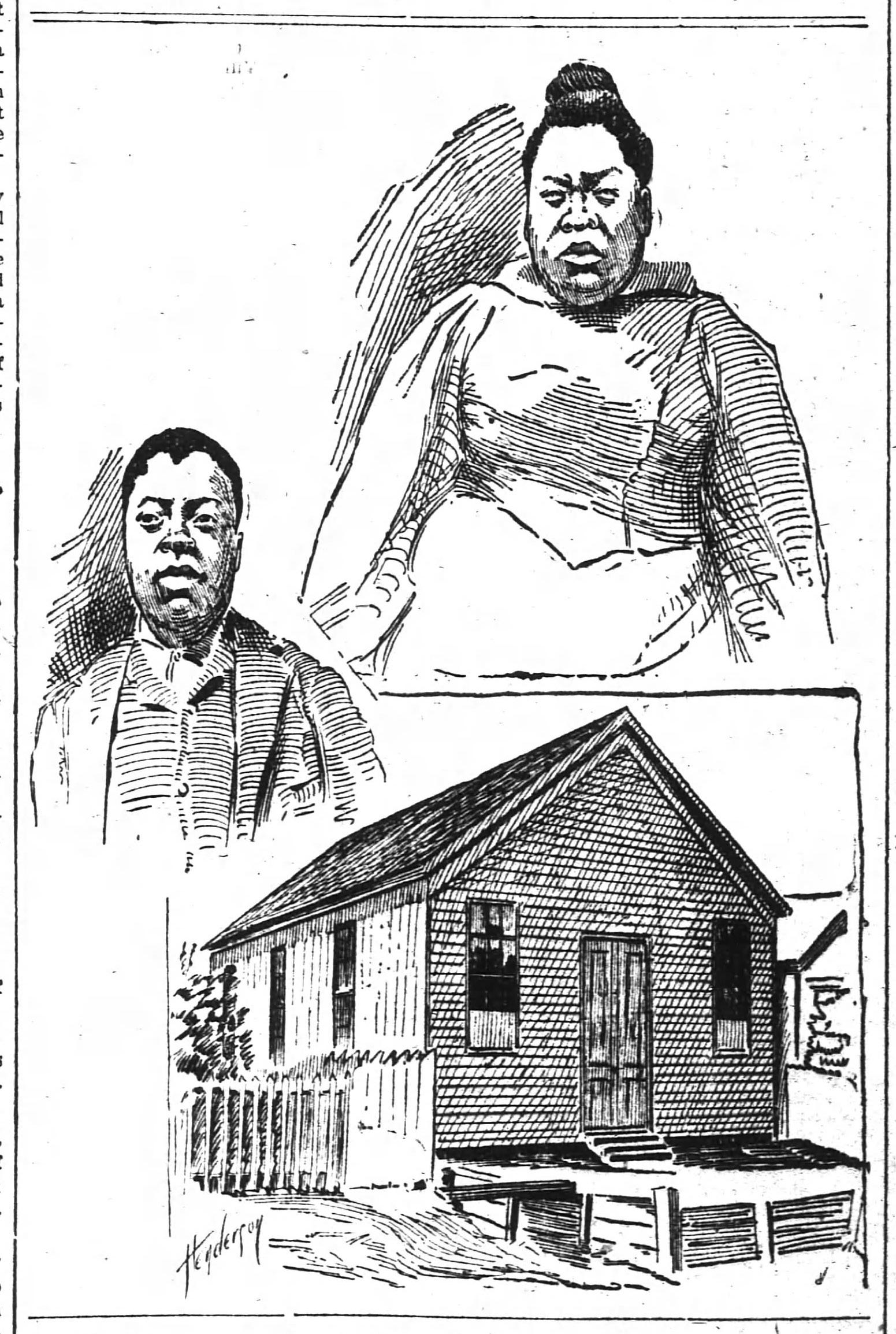

Engraving of Roxy Turner, her son Rolly, and her frst church in Lexington, Kentucky: Te Atlanta Constitution, October 4, 1896.

(Image in the Public Domain)

Roxy Turner (1851?- February 24, 1901)

(Independent Holiness- The Power Churches)

Roxy Turner was born a slave in Kentucky, possibly between 1851 and 1862.36 Almost nothing is known about her early life, although from her own accounts she never received any formal education and could not read or write. She married in 1876 to a farmhand named James Turner and had three sons. According to the accounts, Roxy took in washing to help supplement her husband’s wages, while the family lived in rental houses in Lexington, Kentucky, in African-American neighborhoods. At the time of her death, they were living in a two-room cottage on Race Street.

Around 1890, Roxy began to hold prayer meetings in her house and in the houses of neighbors and by 1891 they had formed a group called the Christian Faith Band in the African American community of Goodloetown in Lexington. Roxy’s principal teaching was on the “seven powers” and so her group became known locally as the “Power Churches,” “Power Society,” or “Power Band.” By 1894 a second band had been formed. An early description of their services was noted in 1895,

No regular pastors are employed, the exercises being participated in by the members, as the spirit moves them. Tese talks are indulged in by both male and female. Te talks are mostly in the shape of giving experiences, and the exhortation of others to greater piety. Te frst congregation soon had over a hundred members and the second now has a numerous membership.37

36 Much of this work is original research by the author which will be part of an upcoming article which will go into more depth.

37 “ Te ‘Power Church.’ Or Christian Faith Colored Organization.” Lexington Herald-Leader March 8, 1895: 6.

Before long, various congregations of the Power Churches began to appear around Central Kentucky. While there are few descriptions of her services, one reporter wrote,

Services opened with a weird hymn, followed by a prayer. With a rhythmic cadence that was not without its infuence on the listeners, a spare, ink black old woman with the strange, wrinkled face of a fetish woman, in a cracked voice, began her prayer. All of the elect fell on their knees, with bodies swaying, and with groans and exclamations of “Oh-h-h-h-h Lord!” and “Praise to His name!” kept up a sort of humming accompaniment to the voice of the old woman.

Prayer was followed by hymn and hymn by prayer for half or three-quarters of an hour. Ten Robert Smith, the regular minister of the church, announced that there would be a short ‘experience meeting’. “I want all that love the Lord to get up and testify. Make it short, say what you have got to say and say it quick or we will have to cut you of,” he said.

Te “experience” meeting evidently appealed to those in the church. In all parts of the house the negroes rose up, with eyes fashing, faces shining, and, with rude wild gestures, would shout a few words, such as “I’m a servant of the Lord, called from on high; I ain’t ashamed to tell it, and am going to heaven when I die, and wouldn’t take nothing for my journey.”

“Sister Roxy” Turner then ascended the altar for a short sermon, selecting a text from Revelations, she preached the awful day of the Lord’s judgement. Shouting at the top of her voice, leaning out over the railing and pounding her words into the listeners with her great arm, “Roxy” painted a picture of hell that many of the unregenerate could not stand, leaving

the church interior rather than stay and listen. Shriek afer shriek went up from the sanctifed- they were feeling the power- a wild clamor rang through the church, and when the priestess sank exhausted to her seat mourners were weeping on every bench.38

When asked to describe her teachings of the “seven powers,” Roxy responded:

Tere are seven powers. First there is the high power, or Holy Ghost. In order to get this power one must be converted and pray fervently for a long time, until they are purged of every sin. Second, there is the healing power, which enables the possessor to heal the sick. Any one possessing the second power can go to your bed when you are dying and restore you to perfect health. Tird, we have the overcoming power. Tis power enables you to overcome sin. You may desire to indulge in the follies of the world ever so much, but when once endowed with the overcoming power you are able to turn away. Fourth, there is the standing power. Tis consists of the ability to withstand temptation. Te scorn of the world and the rebukes of your enemies have no efect upon you when you have the standing power. Fifh is the enduring power, which enables one to stand any hardship without physical injury. No matter how cold it is, anyone possessing this power cannot be frozen. Te sixth power is the controlling power, by which dangers can be avoided and happenings prevented. Te seventh, or last, power enables one to commune with the dead. A member possessing this power can go into the grave-yard, out yonder, and talk with friends who have departed this

38 “Roxy Head of a Strange Kentucky Sect in as Ebony Priestess: How She Sways Her Followers and Conducts a Strange Weird Service.” St. Louis Dispatch, December 23, 1900: 43. Tis article was reprinted in 1901 in Te Boston Globe.

life years ago. Yes, I have the healing power, and all the others except the seventh, which I intend to get in a few weeks.39

While not entirely orthodox, Roxy’s teachings have clear markers of the Holiness Movement with a second empowerment of the Spirit following conversion, an acceptance of divine healing, and teachings of sanctifcation which allow a believer to be free from sin in their life.

Beyond this, Roxy claimed that through the power of the Holy Spirit she was given the ability to read scripture. Accounts describe Roxy as “an unusually large woman, tipping the beam at 365 pounds and standing six feet two inches in her stockings.”40 But she is also recorded as,

“Roxy” Turner, the ebony priestess of this strange sect, is a rather squat, fat, ordinary negro woman, not more than 5 feet 4 inches in height, weighing nearly 300 pounds. She does not know her age. “Roxy” received no education, or says she received none, and claims to have obtained the power of reading afer she “saw the face of the Lord and got the power from the Most High.”41

39 “Sister Roxy’s Society. Religious Society Founded by a Negro Woman. A Worship Tat is Peculiar and a Faith Tat Inspires- Te Power Defned.” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, October 4, 1896: 6.

40 “Strange ‘Power’ Church”. Te Atlanta Constitution, October 4, 1896: 18.

41 “Roxy Head of a Strange Kentucky Sect in as Ebony Priestess: How She Sways Her Followers and Conducts a Strange Weird Service.” St. Louis Dispatch, December 23, 1900: 43. Note, many of these articles are written using dialect. Since this was ofen a method to disparage or belittle African Americans for a lack of education, I have chosen to quote from these articles, but not use the dialect form they chose, but put the words into proper English.

Engraving of Roxy Turner, preaching and healing: Te St. Louis DispatchDecember 23, 1900.

(Image in the Public Domain)

By 1900, the Power Churches numbered about 25 to 30 congregations spread across Central Kentucky. Roxy claimed these were all connected to one central church with the rest being local bands. One of her obituaries recorded,

Roxy Turner was a woman of unusually vigorous intellect for an uneducated woman and expressed herself eloquently, sometimes picturesquely, and through her infuence the “Power Church” wielded a great infuence among certain Negroes. She was exceedingly pious and it is said by her acquaintances that she lived an eminently correct life. Her belief and doctrine was, substantially stated, that she was imbued with especial “power” from God to bless, to foresee, to alleviate pain, in some instances where the belief of the suferer was great enough, and that she herself enjoyed special divine privileges in the working out of the Lord’s will concerning her people, and could call down “power” from on high to help her in her work.42

Several accounts also mention that Roxy was the only “colored woman” to hold a preaching license in the state of Kentucky at the time. But Roxy’s work was not limited to African Americans. A powerful account of her healing a white woman, Mrs. Frank Cox, was widely published, and white people would attend services in Power Churches. Roxy herself indicated that, “white folks come to my meetings everywhere I go. Just two or three, not many except at Harrodsburg, and they come to the meeting and give their experience just the same as us, and sometimes get up and exhorts some too.”43

42 “Roxey Turner, Founder of the Famous ‘Power Church’ is Dead. A Peculiar Belief.” Lexington Herald-Leader, February 26, 1901: 8.

43 “Roxy Head of a Strange Kentucky Sect in as Ebony Priestess: How She Sways Her Followers and Conducts a Strange Weird Service.” St. Louis Dispatch, December 23, 1900: 43.

Roxy Turner died on February 24, 1901 from a case of infuenza. Some recent accounts seem to label this the “Spanish fu” but this was a number of years before the Spanish fu epidemic of 1918. Accounts of her death were even reported in Cincinnati and Atlanta. One of which reported,

“Sister” Roxy Turner, the head of the “Power” Church in Kentucky, was buried this afernoon. Sister Roxy was one of the most infuential women of the negro race in this state and in the South. She created a sensation about ten years ago by the organization of the so-called “Power” Church. She preached the doctrine that all who worshipped as they should and spent their days in the service of God received a mysterious “power” from heaven. She claimed herself to have received the “power” and claimed to have raised the dead and healed the sick.44

It is important to note that the Power Churches did not end at the death of Roxy Turner. Te church in Danville continued to hold a camp meeting, and even by 1909 records indicate the twelfh annual meeting of the Christian Faith Band Union. One interesting aspect of the Power Churches was the prominence of women leaders.

In one brief description of Roxy’s church, it notes that there were white lace curtains on the windows and a railing of white to separate the true believers from the general audience. Tere was also an arch over the railing with the inscription, “ Tis is the Holy Temple of Holiness of the Power of the Star of Bethlehem, the Holy

44 “’Power’ Church Organizer Buried: Sister Roxy Turner Had Great Infuence Over Negroes.” Cincinnati Commercial-Tribune, February 27, 1901: 2.

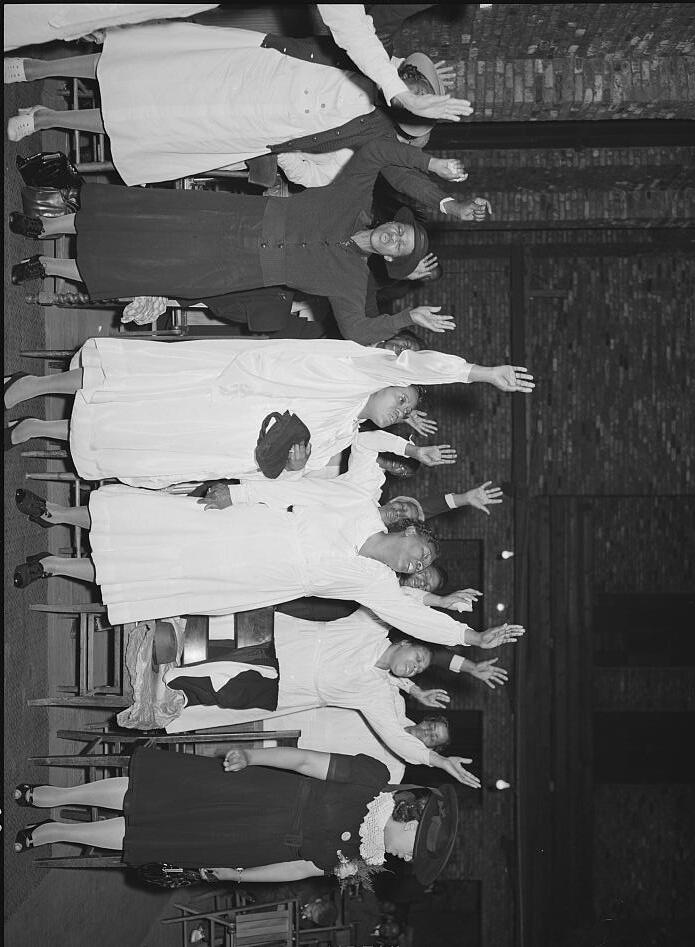

Ghost.”45 No special dress is noted at this time, but by 1903 there are accounts of women members wearing slate gray veils like Catholic nuns.46 In 1904, a woman in Louisville, named Annie Martin established a Christian Faith Band, where she was called “Mother in Israel” and the women came to worship dressed in white. When asked about her church, Annie replied,

“Our church is one of holiness,” she said. “We believe that a Christian should have no sin, and we teach it. We teach the old-time religion, and we fnd it in the Bible. We commune once a week and dress in white because it is an emblem of purity of the heart of our members. Our purpose is to save sinners, just like any other church, but we do not believe like most of the churches that a person can be part Christian and part sinner.”47

It is possible this use of special clothing developed afer the death of Roxy Turner, since there is no mention of this while she was living. But there is plenty of evidence that women preachers in the Christian Faith Band were fairly common, and this is likely tied to Roxy Turner herself. Other women teachers of the group include: Rev. Mary E. Bedinger, Harriet Grevious, and Ruth A. Murphy, who seems to take a major leadership role. In 1910, afer a convention held by Ruth A. Murphy, the group ofcially changed their name to “ Te Pentecostal Power Church for the

45 “Roxy Head of a Strange Kentucky Sect in as Ebony Priestess: How She Sways Her Followers and Conducts a Strange Weird Service.” St. Louis Dispatch, December 23, 1900: 43.

46 “‘Healer’ Given Cent and Costs: Two Negro Preachers Were Defendants- Lively Trial Before Justice Payne.” Lexington Herald, November 8, 1903: 16. Cf. “’Power Preacher’ Arrested.” Lexington Herald, August 24, 1904: 3.

47 “People Cannot Live Part Christian and Part Sinner”. Te Courier Journal (Louisville, Kentucky) December 5, 1904: 6.

Promulgation and Advancement of the Kingdom of God.”48 On the ofcial paperwork, Ruth A. Murphy is listed as the “chairman” of the group. While the Power Churches added “Pentecostal” to their name, it is not until 1912 that there is any indication of the practicing of glossolalia or “speaking in tongues” in the group.

Women continued to play a major role with Mary Bedinger and Ruth Murphy having key leadership and teaching roles, and other women’s names begin to appear including Sister Willie Saunders, Sister Brock, Sister Lena Fisher, and Sister America Jackson. By 1914, names include Pastor Lizzie Stewart and Pastor Alice Shores in Danville. Ruth Ann Murphy had been a preacher in the Star of Bethlehem Church back in 1909 and by 1920 through 1930 she was the pastor of the Pentecostal Power Church.

While, little is known about this group, it is clearly an example of how African-American women were empowered by the Holiness message, even in fairly remote locations. It is likely that similar situations occurred elsewhere, but were ofen not recorded in popular media of the time. Tere is some evidence that the Power Churches had infuence as far away as Cincinnati, and so the teachings of Roxy Turner may have infuenced other groups along the way. While it is complete speculation, it is interesting that William Seymour spent time in Cincinnati around the height of Roxy Turner’s work at the time of her death. Seymour’s version of Pentecostalism at the time of the Azusa Revival may owe some ideas to the Power Churches or pastors he may have encountered there.

48 “A New One: ‘ Te Pentecostal Power Church for the Promulgation and Advancement of the Kingdom of God’ is Incorporated.” Lexington Herald Leader May 11, 1910: 12.

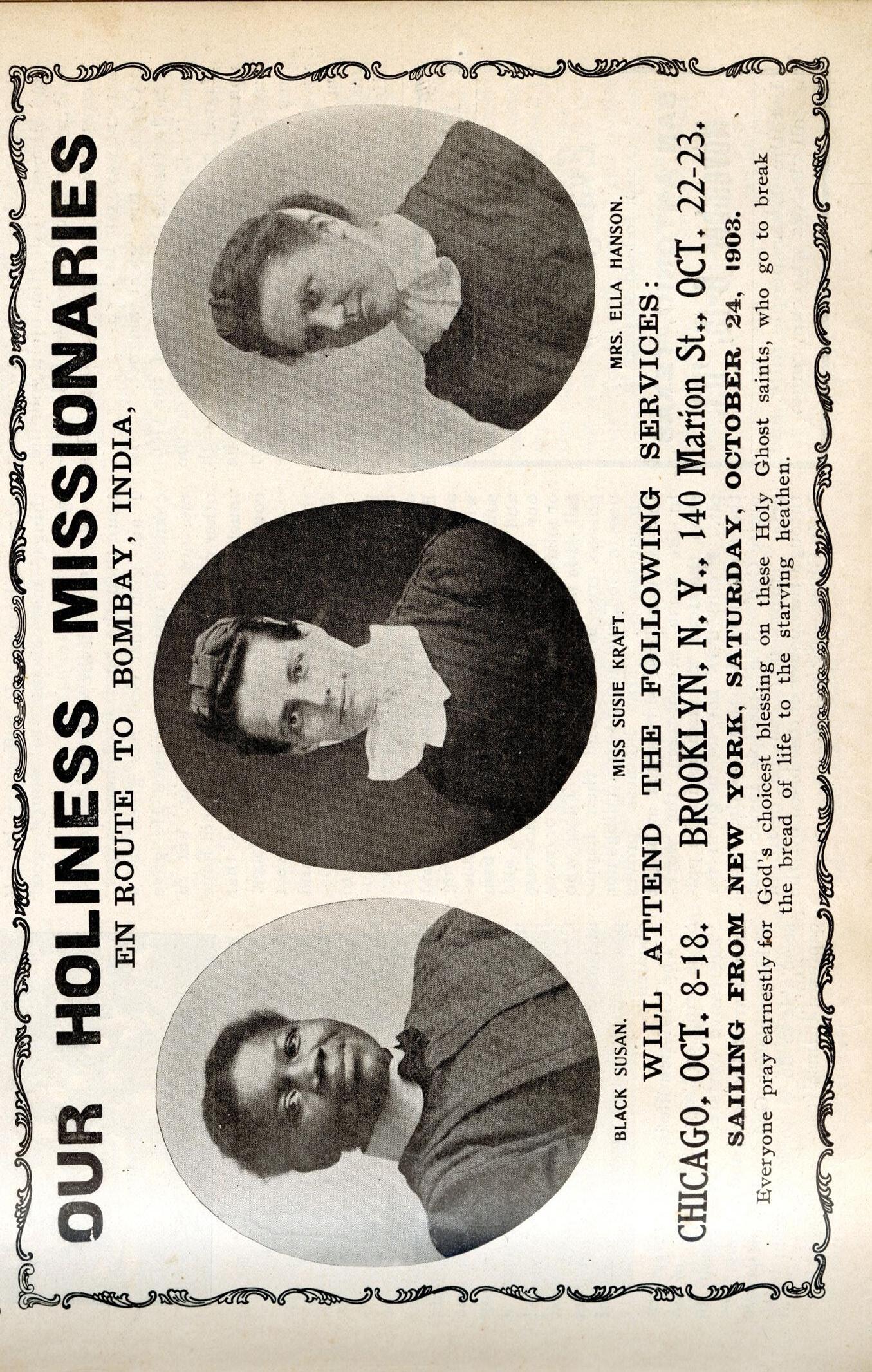

of Susan Fogg, popularly known as

Susan”. (Image in the Public Domain)

Photo

“Black

Susan Fogg (1875- ?)

(Radical Holiness- Metropolitan Church Association)

Born in Louisburg, North Carolina, outside of Raleigh, Susan was the second child of fve children born to Archibald and Deliah Fogg.49 Susan’s father was a farm worker, and she never learned to read or write. Sometime around 1900, when she was in her early 20s, Susan headed north, most likely to look for work, since she indicated that was a driving force in her life at one time. She was recorded in 1903 saying, “I believe when God gave me enough salvation to give up washing and ironing, the fruit of the sacrifce was to be winning souls. I felt I was gone when I stopped my trade, but I praise God I ever died out and quit working for dollars, and when people come ‘round telling me to work for a salary I look to Jesus.”50

By 1901, Susan Fogg was working as the head of the laundry at the Pentecostal Collegiate Institute and Bible School in Saratoga Springs. Tis was their second year in operation out of the Kenmore Hotel, which was purchased to house the school. A scholar on the history of the school (later to become Eastern Nazarene College) wrote,

Probably the two greatest spiritual forces in the school during this year were the President and the Negro woman, Susan Fogg, who worked in the laundry. In a letter to his mother Tracy reported that the “head professor was keeping up a profession but has lost the experience of Holiness and God got hold of him and made him willing to be taught and led back again by the negro worker women (sic) who had charge of

49 Te content of this article is also original research by the author, which will come out in a more detailed form in a future article.

50 “ Te Missionary Meeting.” Te Burning Bush, September 3, 1903: 4.

the school laundry…” Not only was Susan Fogg an efective evangelist at the school but she was in great demand to hold services, especially in New England. Tracy enthusiastically predicted that in a few years she would become as popular as Amanda Smith.51

In July 1902, Susan Fogg attended the camp meeting at Camp Hebron in Attleboro, Massachusetts, where she is referred to as “Black Susan of Saratoga, N.Y.” Two days later, President L.C. Pettit of the Pentecostal Bible Institute also arrived at the camp meeting. Te article notes, “ Te ecstacy (sic) of the meetings has increased considerably. Yesterday one of the speakers climbed one of the timber uprights and preached down to his audience from among the rafers; another leaped upon the reading desk and spoke from there; the marching, leaping, creeping, shouting and evidence of strong physical ecstacy (sic) are very much in evidence.”52 Te report also includes a case of divine healing, and prophecy of a volcanic eruption in the Caribbean, which had been fulflled a week afer the prediction. However, despite all of this, the author ends the article noting,

Among the most interesting characters at the camp is the acrobatic but very earnest negro woman, “Black Susan.” Her exhortations, her remarks interjected at the top of her lungs into the remarks of the speakers, and her exhibitions of physical agility, which are continuous, make her easily the most conspicuous person at camp. Some of her sayings have been caught by Rev. Mr. Greene, and his little collection of them contains some very quaint gems of negro philosophy.53

51 James R. Cameron, Eastern Nazarene College: Te First Fify Years, Kansas City, MO: Nazarene Publishing House, 1968: 25.

52 “’Wrath of God.’ Man Who Prophesied Eruption of Mt Pelee.” Boston Daily Globe, July 9, 1902: 17.

53 Ibid.

It appears that Susan Fogg remained in Lowell, Massachusetts instead of returning to Saratoga. An introduction to a publication of some of her sayings, produced in 1902, contains an introduction by L.F. Mitchel.54 He wrote in his introduction,

Truly this “King’s daughter is all glorious within.” We praise God for ever sending this Spirit flled woman to the Pentecostal Institute. She had not been with us two days before eleven were on their faces, reminding one of Sammy Morris’ experience with the students. May God use her burning words and make them live coals to many a heart and tongue. We need more men and women who are packed with holy fre, and who travail in prayer, and shout God’s praises and leap for joy, and put the trumpet to their mouths and cry aloud, as Susan does. God bless her and make her one hundred times more than she is.55

Another introduction by Samuel G. Otis of the Christian Workers Union notes that she was present with that group for a year (most likely 1902). Otis established the Christian Workers Union in 1878 in Springfeld, Massachusetts. His work was publishing a monthly magazine Our Gospel Letter, which would later become Word and Work, as well as tracts known as Word of Life. Otis was one of the earliest holiness publishers to work all over Southern New England. His wife transcribed the sermons at the Portsmouth camp meeting, which Samuel helped organize in 1890. He wrote, “During the year Susan was with us, she used to say, ‘I’m settin’ in the beltry, pullin’;” by which she meant she was holding on to God

54 Mitchel would join the Metropolitan Church Association and leave his position as a professor of music at the Pentecostal Institute. He would become a major supporter of the MCA and write music and hymnbooks for the group.

55 Nuggets No. 2 From Black Susan, Words of Life, No. 111, gathered by Louis F. Mitchel, Christian Workers Union, Springfeld, MA, 1902: 2.

in prayer. We believe much more work could be accomplished for God if there were more ‘Beltry’ Christians.”56

At the time of another camp meeting at Camp Hebron on September 9, 1902, another article noted,

Camp Hebron was again yesterday the center of attraction for thousands of persons who are interested in the holiness movement. Te vast congregations at each service manifested great enthusiasm.

Rev. Arthur W. Greene of North Attleboro, Mrs. Susan Fogg of Lowell and Frank Governs of Saratoga, NY, were the principal speakers. Tey delivered stirring addresses. Said one: “If the churches and ministers are holy, they don’t have to be supported by selling beans, by selling neckties and by such things.”57

In December of 1902, the group from the Metropolitan Church Association descended on the town of North Attleboro, Massachusetts. Tey clearly had the way opened by Rev. Arthur Greene who was the pastor of two groups, the independent Emmanuel Pentecostal Church and the People’s Free Church. He had also established a holiness campground known as Camp Hebron in the area. Te Boston Post described the opening of the event on December 24, 1902,

Te “White Horses” have opened their holiness convention. Tose present are: E.L. Harvey, the sanctifed Chicago hotel man; Duke M. Farson, the sanctifed Chicago banker; Mrs. Kent White, said to be the greatest woman preacher in the West, hailing

56 Nuggets No. 2 From Black Susan, Words of Life, No. 111, gathered by Louis F. Mitchel, Christian Workers Union, Springfeld, MA, 1902: 2.

57 “Holiness Movement: Large Gathering at Each Service Held Yesterday.” Boston Daily Globe, September 9, 1902: 16.

from Denver, Col.; John Wesley Lee of Indiana; A.F. Ingler, the famous singer and composer of Denver, Col.; Susan Fogg, known all over this district as “Black Susan,” who created such a sensation in town last winter; Mrs. E.L. Harvey and F.M. Messenger of North Grosvenordale, Conn., who is chairman of the New England workers.

Te attendance, while small, has lots of spirit in it. A vigorous attack is expected to be made on the various secret orders.

E.L. Harvey conducted the services. Once or twice he let out and the hall re-echoed with the yells of the evangelists. Duke Farson was on the stage, and he helped matters along all he could. “Black Susan” also made herself conspicuous during the session. Before the convention is brought to a close many unheardof events are prophesied for North Attleboro by the evangelists.58

By December 26, 1902, the group of evangelists were expected to leave the Opera House where the convention was being held. Te article noted:

Owing to the fact that a theatre company was booked for this evening, the Holiness convention was obliged to adjourn to another hall. Te worshippers did not like the idea of leaving the opera house, and so started an outdoor rally. In a short time a crowd had gathered, and the street was blocked.

Chief of Police E. Carlisle Brown and ofcer Jesse B. Stevens were obliged to order the noisy singers inside. Susan Fogg, better known as “Black Susan,” and Mrs

58 “White Horses” Holding Holiness Convention.” Boston Post, December 25, 1902: 5.

Photo of T e Metropolitan Church Association Bible School in 1903, with Susan Fogg in the lower le f . T e Burning BushJune 4, 1903. (Image in the Public Domain)

Kent White of Denver, Colo., rebelled against the order, and called the chief a bulldog.

As she was forced through the door to the hall, she screamed out: “I pity this town. You’ll get your fngers burned if you touch me.”59

Tings got even more raucous as the convention continued into January of 1903, when a Miss Maud Reed died of heart disease during worship. Te physician said that the “heart disease was brought on by the excitement.” Te young woman was only 21 years old. Te account ends, noting, “Afer the young woman’s death the worshipers continued shouting and praying with added fervor. Susan Fogg, known as “Black Susan,” fainted away and it was more than an hour before she regained consciousness.”60

By April 30, 1903, Susan Fogg was conducting a revival in Lincoln, Nebraska with Mrs. Kent White as part of the Pentecostal Union Evangelists of Denver, Colorado.61 Mrs. Kent White explained in the article that in 1890 she lef the Methodist Church and joined the Burning Bush group to return to an earlier form of the “Shouting Methodists.” Susan Fogg is listed as “a colored exhorter of Boston, Mass.” Te article also contains a detailed description of the group’s eforts,

Te meetings are announced on the streets by Sister Fogg, who assisted by local converts, does a cake walk and a sort of dance. When she has gathered a large crowd she conducts them to the hall where the other evangelists are awaiting their arrival. As soon as the

59 “Didn’t Like It. Holiness Convention Had to Leave Opera House.” Boston Daily Globe, December 27, 1902: 2.

60 “Fatal Excitement. Maud Reed Succumbed to Heart Disease. Dropped Dead in Holiness Meeting in North Attleboro.” Boston Daily Globe, January 2, 1903: 7.

61 “Will Hold Meeting.” Lincoln Daily Star, April 30, 1903: 2.

audience begins to enter a musician strikes up a tune on the piano. Ten the Rev. Mr. Ingler begins to sing in a monotone, assisted by the other members of the party, some kneeling, others pacing back and forth on the platform and still others jumping up and down. Te music is continued for nearly an hour and its efect upon the more susceptible of the auditors soon sets them to swaying and singing in unison with the others. Afer the song is concluded a prayer begins. One member of the party prays in a frenzied and impassioned manner, gradually working himself up to a pitch where he shouts, screams and rages. During the prayer the other members of the party break in with various ejaculations.

As the prayer draws to a close the praying one rises to his feet, with arms extended outward and face turned upward and beseeches and entreats as though to avert some terrible crisis. Te others spring to their feet and as the prayer concludes another starts in. Friday night, Sister Fogg, in her excitement, grabbed a chair and swinging it alof marched up and down the platform whirling it over her head. Some of the mourners and penitents involuntarily “ducked” their heads to prevent a possible collision, but continued their swaying and crooning.

At the conclusion of the prayer the Rev. Mr. Ingler delivered a short sermon, SAY THE CHURCHES ARE WRONG.

“ Te churches are all wrong,” said he, “ Tere is no religion in them. At the Pentecostal supper the Lord and his disciples drank wine. Yes, wine. Some called them drunk, but, dear ones, they were not drunk on the wine, they were drunk with the spirit of the Holy Ghost. I am drunk with that same tonight.”

“I’se drunk, too, praise God,” vociferously declared Sister Susan as the speaker paused.

Mr. Ingler, at the conclusion of his address, introduced the Rev. Mrs. White, the leader of the sect in the United States. She is a forcible talker, but gradually as she got deeper and deeper in her sermon worked into a frenzy. She took as her theme the old story of Jonah and the whale. Her discourse was frequently interrupted by the others, and in some parts was in the nature of a dialogue.

“ Tere are Jonahs in this audience tonight,” she declared, and several of the colored members of the congregation glanced nervously at those occupying seats next to them. “You are all Jonahs, unless you have the love of God in your hearts and are sanctifed.”

During the progress of the meeting many of the audience, particularly the colored members, became excited and joined in the exhortations.

“ Te Lord is here tonight,” declared the speaker.

“Dat’s right! I sees you, Lord,” vehemently asserted a portly sister in the audience, carried away by the hypnotic infuence which the speaker seemed to extend.

“He wants to see you all up there,” continued the speaker.

“In cose he does, dat’s right,” assented the other.

“Give up all and follow Him,” went on the speaker. “He will provide. You won’t have to worry if you are sanctifed. Your heart’s desire will be gratifed.”62

62 “Pentecostal’s Noisy Meeting.” Lincoln Daily Star, May 2, 1903: 1.

A number of the saying of Susan Fogg have been recorded, and an assortment of them provides a good overview of her impact in these types of holiness meetings:

I prays in season an’ out of season, so as to make a season an’ be in season. Down South when it is dry we go to the pumps an’ sprinkle our gardens an’ make a wet season. So when it is dry, that is a sign to me that I mus’ pray, pump an’ sprinkle.63

I like grapes when they is cool an’ sweet. O, how good they tas’ on a hot day! Tat is jes’ what God feeds me on when my soul is dry an’ parched. He’s got lots of grapes for you if you’ll reach out an’ take ‘em.64

Berries that grow way up on the hill-side ain’t like those that grow down in the rich valley. If you want big, fat ones you mus’ go down in the valley. Tat’s where we gits the bes’ fruits of the Spirit.65

My people is gittin’ fashioned an’ stif. Tey don’t git down on their knees an’ foor as they use to do. Tat is the way I got it an’ I am goin’ to keep it. As you receives Jesus so mus’ you walk in Him. It took a heap to save me, an’ it takes a heap to keep me. I can’t ‘ford to let up on any of these lines, for I was an awful mean negro.66

Don’t let up on me, Lord. I wants to know the wors’ of my case now. Te day of judgment will be too late for me to fx up; so I asks You to turn your great lectrif light on me so I can see things jes’ as they is.67

63 Nuggets No. 2 From Black Susan, Words of Life, No. 111, gathered by Louis F. Mitchel, Christian Workers Union, Springfeld, MA, 1902: 4.

64 Nuggets No. 2 1902: 5.

65 Nuggets No. 2 1902: 6.

66 Ibid.

67 Nuggets No. 2 1902: 7.

Te Lord stir up our faith in us. Prayer is the key, but it takes faith to turn the key an’ unlock the door. Tere is lots of doors locked up an’ we need faith to unlock ‘em.68

I praise God I got salvation. I didn’t get religion an’ hang it up on a nail.69

All the Lord asks of me is to jes’ be my own black se’f, flled with the Holy Ghost.70

I bless God for freedom. When a bird sits up yonder in a tree, she ain’t askin’ who the tree belongs to, she jes’ sits an’ sings. Tat is what I am doin’ this mornin’. My soul is jes’ d’lightin’ herse’f in the Lord. Hallelujah!71

Lord, don’t you let me go to that convention if I wants to have a ‘scursion or a good time. You make me a ball of fre or You keep me home.72

I want to be boilin’ hot, so I can burn an’ blister sin an’ scal’ the devil. Some of you people haven’t got fre enough to burn a bug.73

I’m ‘shamed of some white folks, and some white folks is ‘shamed of me. I was in a ‘lectrif car once with a white friend, an’ he was ‘shamed of me ‘cause I was black, an’ I was ‘shamed of him, ‘cause he smelt of tobacker. 74

68 Nuggets No. 2 1902: 8.

69 Ibid.

70 “Black Susan.” Te Burning Bush, January 1, 1903: 3.

71 Ibid.

72 Ibid.

73 “Black Susan.” Te Burning Bush, January 1, 1903: 4.

74 Ibid.

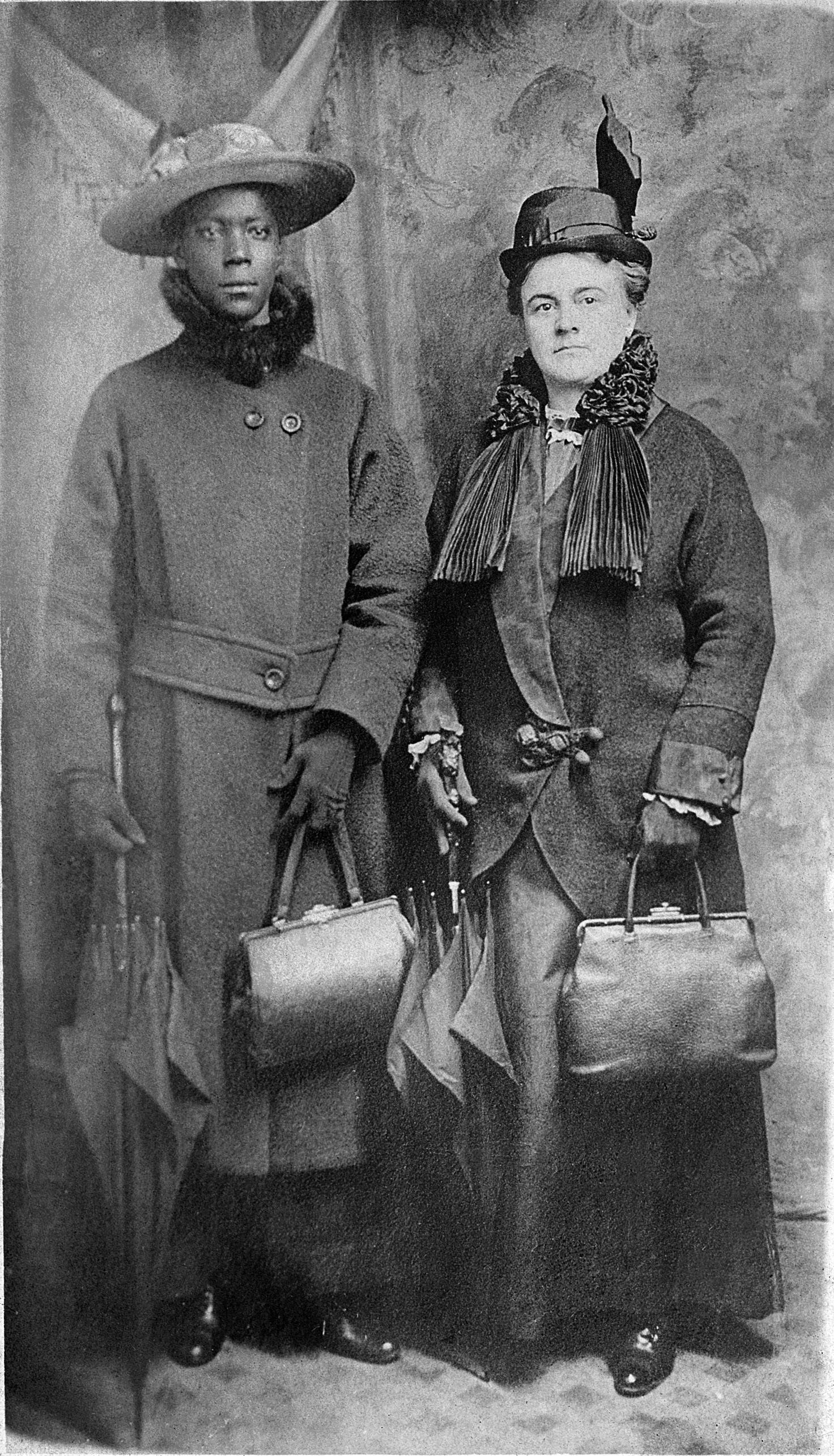

Last known photo of Susan FoggT e Burning BushOctober 8, 1903. (Image in the Public Domain)

Tey call me Black Susan, but I’ve got a salvation that’s mo’ than skin deep, an’ the Lord sees through the whole business an’ calls me whiter than snow.75