Volume 2. Issue 2. May-August 2025 A publication from

Welcome to issue 2 of the 2nd volume of the Arbona Health Hub’s Newsletter. We are so happy you are here!

Volume 2. Issue 2. May-August 2025 A publication from

Welcome to issue 2 of the 2nd volume of the Arbona Health Hub’s Newsletter. We are so happy you are here!

If there’s one thread running through this edition of the ArbonaHealthHub,it’surgency.

Urgency to understand — how a single gene mutation canunraveltheimmunesystem.

Urgency to adapt — as antibiotic resistance creeps forwardwhileinnovationlagsbehind.

Urgency to act — when public health systems falter and liveshanginthebalance.

In this issue, our contributors ask sharp questions and chase realworld answers. From the cellular level to the structural failures of healthcare policy, these pieces reflect a generation of thinkers unafraid to look complexity in the eye, and write it clearly.

Chairman of the Board

Alejandro Arbona Lampaya Chairman of the Board

Sofía I. Malavé Ortiz Board Secretary

Avery R. Arsenault Vice-Chair

Marcel De Jesús Vega Peer Review Coordinator

1.Janlouis Rodriguez-Figueroa, MPH

Christian G. Correa García Board Member

2.Iranis N. Hernández González, MS4 Universidad Central del Caribe School of Medicine

3. Alejandro Arbona Lampaya, MS2 University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine

4 Avery R Arsenault, Post-Baccalaureate IRTA Fellow, Office of the Clinical Director (OCD), National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

5. Héctor Cancel Asencio, Post-Baccalaureate IRTA Fellow, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

6. Sofía I. Malavé Ortiz, Post-Baccalaureate IRTA Fellow, National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences

7. Marcel De Jesús Vega, Post-Baccalaureate IRTA Fellow, National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

8 Christian G Correa García, MS3 San Juan Bautista School of Medicine

This page was intentionally left blank

Writtenby:VictoriaBlaiotta-Vazquez,MPH

PublishedonlineonMay21,2025

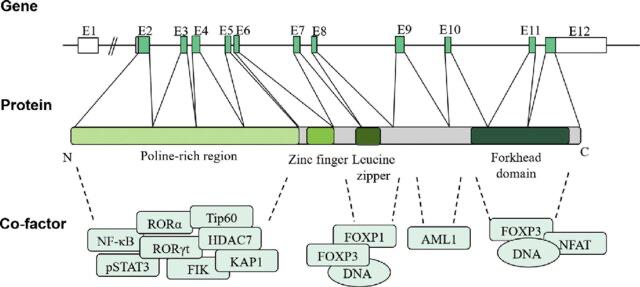

The immune system plays a crucial role in defending the body against pathogens through the coordinated action of specific immune cells, such as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells Among these, CD4+ T regulatory (Treg) cells serve a unique function: they suppress immune responses and prevent the immune system from mistakenly attacking the body’s own tissues Treg cells must express the forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) gene located on the X chromosome to properly maintain immune homeostasis (Figure 1)

FOXP3 is also involved in tissue repair and metabolic regulation (Savage et al, 2020)

Although mutations in this gene can vary and cause different presentations, one of the most well-studied disorders associated with FOXP3 mutations is immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome This rare X-linked recessive disorder typically presents during infancy and leads to systemic autoimmunity due to the failure of Treg cell development or function IPEX syndrome is characterized by polyendocrine dysfunction, chronic enteropathy, and dermatitis (BenSkowronek,2021)

Figure 1. Diagram of the FOXP3 gene structure, mRNA structure, and functional features FOXP3 protein contains four distinct domains, including the N-terminal proline-rich region, central zinc finger, leucine zipper, and forkhead (FKH) domain. These domains can interact with different proteins to regulate transcriptional activity and affect Treg cell function. Reprinted from Huang Q, Liu X, Zhang Y, Huang J, Li D, Li B Molecular feature and therapeutic perspectives of immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome J Genet Genomics 2020 Jan 20;47(1):17-26. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2019.11.011. Epub 2020 Jan 24. PMID: 32081609.

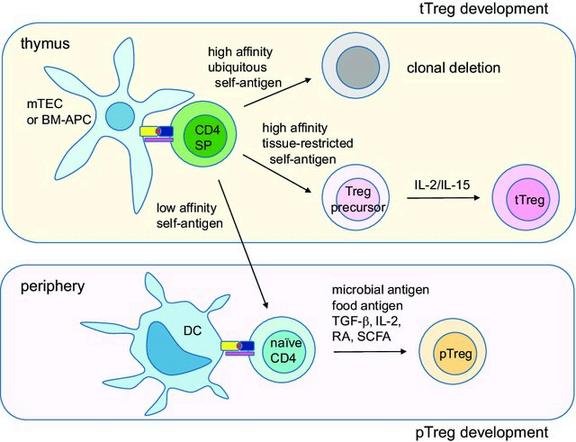

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of Treg cell development tTreg cells develop in the thymus by two-step process First, highaffinity tissuerestricted self-antigens presented by medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) or bone-marrow derived antigen-presenting cells (BM-APCs) derive single-positive (SP) T cells into Treg pathway Second, cytokine IL-2 or IL-15 derives the precursor cells into fully committed tTreg cells pTreg cells develop in the periphery by environmental antigens such as microbial antigens or food antigens presented by mucosal tissue-resident dendritic cells (DCs). TGF-β, retinoic acids (RAs) and short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced in the immunosuppressive environments promote pTreg development Reprinted from Lee W, Lee GR. Transcriptional regulation and development of regulatory T cells Exp Mol Med. 2018 Mar 9;50(3):e456. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.313. PMID: 29520112; PMCID: PMC5898904.

Natural Tregs are produced in the thymus during T cell development, while induced Tregs can be generated in peripheral tissues both of which are essential for maintaining immune tolerance and preventing autoimmunity (Figure 2)

IPEX Syndrome commonly manifests with three hallmark clinical features enteropathy, endocrinopathy, and dermatitis all of which begin in the first year of life (Ben-Skowronek, 2021) Enteropathy presents as intractable diarrhea and is unresponsive to dietary interventions due to immune-mediated damage to the intestines (Gentile et al , 2012) Endocrinopathy most often takes the form of early-onset type 1 diabetes, sometimes emerging within the first weeks of life (Husebye et al , 2018) Dermatologic manifestations include atopic or psoriasiform dermatitis, though more rare presentations such as autoimmune, allergic, or infectious skin conditions have also been reported (Barzaghi & Passerini, 2021) Additional complications may include nephropathy, hepatitis, thyroid disease, and bone marrow abnormalities

Diagnosis is confirmed via genetic testing for pathogenic FOXP3 variants (Tan et al , 2004) The syndrome is extremely rare, with an estimated prevalence of fewer than 1 in 1,000,000 individuals (Tan et al , 2004)

The management of IPEX Syndrome centers around immunosuppressive therapy to mitigate the autoimmune response. This is supplemented by symptom-specific interventions such as supplemental nutrition for enteropathy, topical treatments for dermatitis, insulin therapy for diabetes, and thyroid hormone replacement when needed (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 2022) For patients who are eligible, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) offers the potential for long-term remission HSCT is more effective in patients with less organ involvement, but it is constrained by donor availability and its high risk-benefit ratio (Barzaghi et al , 2018) Rapamycin has emerged as a preferred agent for immunosuppressive therapy and is particularly notable for its ability to modulate Treg cell function through FOXP3-independent pathways (Passerini et al , 2020)

These mechanisms provide new insights into disease control and suggest further directions for treatment innovation.

In severe cases, patients often die within the first two years of life However, immunosuppressive therapy has allowed for stabilization in many patients until HSCT can be performed (Immune Deficiency Foundation, nd) Future research should prioritize understanding the molecular heterogeneity of FOXP3 mutations and their functional impact, which could improve prognostic assessments and inform personalized treatment strategies

Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome is a rare genetic disorder caused by mutations in the FOXP3 gene, which disrupts Treg cell development and function, ultimately leading to widespread autoimmunity The syndrome typically presents with enteropathy, endocrinopathy, and dermatitis While immunosuppressive therapy and HSCT offer effective interventions, each comes with significant limitations Rapamycin shows promise as a FOXP3-independent modulator of immune suppression Continued research into the mechanisms of Treg cell regulation, FOXP3 mutation profiling, and novel therapeutic options is essential for improving outcomes in IPEX patients Future efforts should also focus on earlier diagnosis, donor expansion for HSCT, and targeted gene therapies.

1 Savage, P A, Klawon, D E J, & Miller, C H (2020). Regulatory T Cell Development. Annual Review of Immunology, 38, 421–453 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol100219-020937

2 Huang, Q, Liu, X, Zhang, Y, Huang, J, Li, D, & Li, B. (2020). Molecular feature and therapeutic perspectives of immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome Journal of Genetics and Genomics, 47(1), 17–26 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgg.2019.11.011

3 Ben-Skowronek, I (2021) IPEX Syndrome: Genetics and Treatment Options Genes, 12(3), 323 https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12030323

4 Lee, W, & Lee, G R (2018) Transcriptional regulation and development of regulatory T cells Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 50(3), e456. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.313

5 Gentile, N M, Murray, J A, & Pardi, D S (2012) Autoimmune enteropathy: a review and update of clinical management. Current Gastroenterology Reports, 14(5), 380–385 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-012-0276-2

6 Husebye, E S, Anderson, M S, & Kämpe, O (2018) Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndromes

The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(12), 1132–1141

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1713301

7 Barzaghi, F, & Passerini, L (2021) IPEX Syndrome: Improved Knowledge of Immune Pathogenesis Empowers Diagnosis. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9, 612760

https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.612760

8 Tan, Q K G, Louie, R J, & Sleasman, J W (2004) IPEX Syndrome In Adam, M P, Feldman, J, Mirzaa, G M, et al (Eds), GeneReviews® [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2023

Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1118/

9 Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (2022) IPEX syndrome Children’s Hospital of Philadelphiahttps://www.chop.edu/condition s-diseases/ipex-syndrome

10 Barzaghi, F, Amaya Hernandez, L C, Neven, B, et al (2018) Long-term follow-up of IPEX syndrome patients after different therapeutic strategies: An international multicenter retrospective study. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 141(3), 1036–1049e5 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.041

11 Passerini, L, Barzaghi, F, Curto, R, et al (2020) Treatment with rapamycin can restore regulatory T-cell function in IPEX patients. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 145(4), 1262–1271e13 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.043

12 Immune Deficiency Foundation (nd) IPEX syndrome. https://primaryimmune.org/understandingprimary-immunodeficiency/types-of-pi/ipexsyndrome

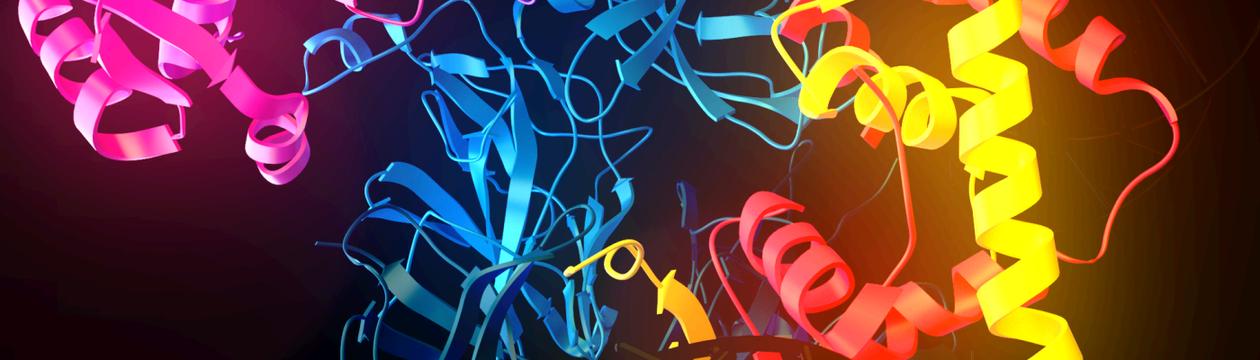

Image Credits

Cover Image: FOXP3 by Ismaïl Jarmouni, retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php? curid=86104165 Used under Creative Commons

Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

Figure 1. Reprinted from Huang Q, Liu X, Zhang Y, Huang J, Li D, Li B Molecular feature and therapeutic perspectives of immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome J Genet Genomics 2020 Jan 20;47(1):17-26 doi: 101016/jjgg201911011 Epub 2020 Jan 24 PMID: 32081609

Figure 2. Reprinted from Lee W, Lee GR Transcriptional regulation and development of regulatory T cells Exp Mol Med 2018 Mar 9;50(3):e456 doi: 101038/emm2017313 PMID: 29520112; PMCID: PMC5898904

Writtenby:JanlouisRodríguez-Figueroa,MPH

PublishedonlineonMay28,2025

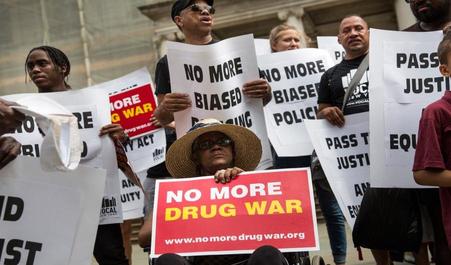

For decades, the so-called “War on Drugs” has been driven by punitive policies that not only fail to protect society but have also led to devastating public health consequences and entrenched racial and social inequalities Drawing on insights from voices such as Dr. Carmen Albizu García and supported by a growing body in interdisciplinary research, this article argues for a fundamental rethinking of drug policy By moving from criminalization toward a decriminalization and regulated legalization, we can foster an approach grounded in public health and racial justice that prioritizes treatment, harm reduction, and community well-being over punishment (Earp et al, 2021)

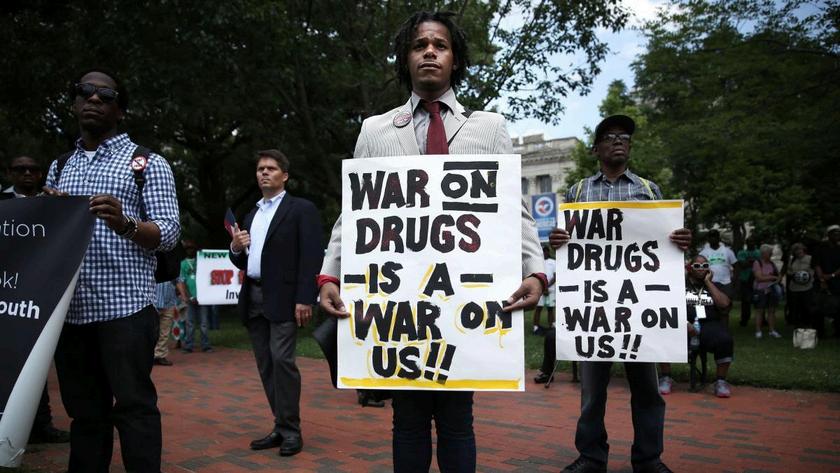

The roots of punitive drug policy can be traced back to the early 1970s when President Richard Nixon’s declaration of ‘War on Drugs” served not only as a political maneuver against opposition but also to target minority communities (Cummings & Ramirez, 2021) While marijuana (cannabis) was Nixon’s oft-cited focus, portrayed as the plague of young antiwar protesters, his campaign also laid groundwork for crackdowns on hard drugs such as heroin and cocaine, treating all these substances as criminal problems rather than health issues (Sirin, 2011) Nixon’s targeted antiwar protesters and minority communities, using drug laws as pretext to discredit opposition This period laid the foundation for a punitive system by linking drug use with political subversion and racial deviance (Cummings & Ramirez, 2021)

Figure 1 On June 17, 1971, President Richard Nixon declared the “War on Drugs” Reproduced from https://time.com/6090016/us-war-on-drugsorigins/

The approach intensified under President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s Reagan expanded harsh sentencing guidelines and increased funding for drug enforcement His policies not only reinforced the punitive measures initiated under Nixon but also amplified the racial disparities inherent in drug law enforcement. These policies boost mandatory minimums for cocaine; especially crack, Reagan’s tougher sentencing guideline contributed to roughly a 400 % increase in the US incarceration rate growing from about 200,000 people behind bars in 1970 to nearly two million by 2000 (Vera Institute of Justice, nd; Ziedenberg & Schiraldi,1999). Altogether these policies contributed to disproportionately penalize Black communities (Palamar et al, 2015; Sirin, 2011)

In recent decades, evolving public sentiment and emerging evidence of the collateral harms of strict enforcement have encouraged new reforms. Measures such as decriminalization in select jurisdictions and a reduction in mandatory minimum sentences reflect a growing consensus: drug use should be approached as a public health issue rather than solely a criminal matter (Smith, 2021; Gottschalk, 2023)

The negative consequences of a punitive approach are far reaching Criminalization discourages individuals from seeking treatment or harm reduction services, exacerbating public health challenges such as the opioid crisis (Tyndall & Dodd, 2020) Moreover, repeated enforcement actions regardless of similar usage rates across racial groups have entrenched systemic disparities, leading to long-term economic and social exclusion Research shows that the legacy of punitive policies continues to bias substance use studies, impeding evidencebased public health strategies (Stone, 2024).

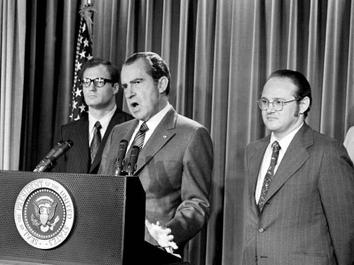

2 Protester holds a sing agains policy reforms. Reproduced from https://theconversation.com/drugprohibition-is-fuelling-the-overdose-crisisregulating-drugs-is-the-way-out-233632

The enforcement driven approach to drug policy has produced widespread negative consequences and serious public health implications Criminalization discourages individuals from seeking necessary health services and harm reductions support (Tyndall & Dodd, 2020) Structural violence and stigma, intensified by punitive policies, have paralyzed effective responses to the opioid crisis in North America and Puerto Rico (Santiago-Negrón & Albizu-García, 2003; Tyndall & Dodd, 2020)

Substance use research is skewed by the legacy of the war on Drugs, ultimately impeding the development of evidence-based public health strategies (Stone, 2024)

Despite similar rates of drug use across racial groups, enforcement practices have disproportionately impacted people of color (Earp et al , 2021; Cummings & Ramirez,2021) The currents drug policy framework reinforces systemic prejudice and discrimination through higher arrest, convictions, and incarceration rates among Black and Hispanic These disparities contribute to long-term economic and social exclusion, perpetuating cycles of poverty and limited opportunities (Earp et al , 2021; Cummings & Ramirez, 2021)

The collateral consequences of these policies extend far beyond individual health (SantiagoNegrón & Albizu-García, 2003) The punitive approach has contributed to the formation of a “prison-industrial complex,” where the economic incentives of mass incarceration further marginalize vulnerable population The focus on punishment has undermined public health efforts and deepened social inequities (Santiago-Negrón & Albizu-García, 2003)

3.

Drug

and War on Drugs Reproduced from http://www.colorofpain.org/criminal-justice

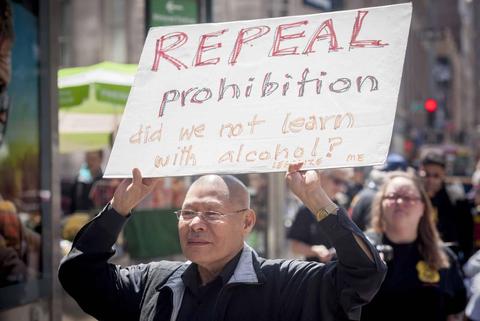

The first step is to decriminalize the possession and use of small amounts of non-medical drugs Removing criminal penalties for small amounts of key substances: cannabis, MDMA, cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine would allow individuals to seek help without fear of arrest, thereby facilitating access to treatment and harm reduction services Evidence from countries like Portugal shows that decriminalization can lead to significant improvements in public health outcomes (Csete et al , 2016)

Portugal’s 2001 reform reclassified personal possession of all drugs as an administrative, not criminal, offense Decisions are made by local “dissuasion commissions” that include health and legal professionals, who can refer individuals directly into counseling or treatment instead of jail. Savings from reduced prosecutions were then funneled into community-based services, resulting in a 60 % increase in treatment uptake and an 80 % drop in HIV incidence among people who inject drugs within five years (Greenwald, 2009; Hughes & Stevens, 2010)

Decriminalization should be followed by comprehensive legal regulation. By establishing a framework similar to alcohol and tobacco controls: license the cultivation and sale of cannabis, pilot prescription of heroin in supervised settings as in Switzerland and offer drug-checking for MDMA or cocaine to guard against adulterant like fentanyl (Hughes & Stevens, 2010; Westenberg et al, 2023) Standards for production, distribution, and sale, regulation can ensure product safety, reduce the harms associated with adulterated drugs, and generate tax revenue to be reinvested in public health programs (Maghsoudi et al., 2022).

Resources saved from reducing incarceration rates should be redirected toward expanding addiction treatment, preventive education, and community-based support programs Such reinvestment would address the underlying social determinants of drug abuse, fostering long-term improvements in public health and social equity (Gottschalk, 2023) A critical component of reform is reorienting police practices to prioritizing health interventions over punitive measures can further reduce the collateral harms inflicted on marginalized communities (Christine, 2021; Earp et al, 2021)

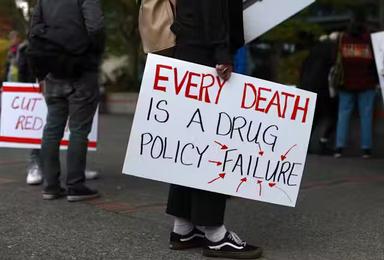

Empirical evidence and personal testimonies alike reveal that the current punitive model not only fails to prevent drug use but also magnifies health risk, social inequities and illustrate the human cost of criminalization, families disrupted, lives altered by criminal records, and communities left without support A comprehensive shift toward a public health centered strategy is essential for reducing overdose deaths, curbing the spread of infectious diseases, and repairing communities that have long endured the burden of harsh drug policies (Cummings & Ramirez, 2021; Santiago-Negrón and Albizu-García, 2003)

Figure 4. Drug policy fail. Reproduced from https://reason.org/commentary/drugprohibition-has-failed-it-is-time-to-legalizedrugs/

Decades of punitive drug policies in the U.S. and Puerto Rico have deepened racial and social injustices, exacerbated public health crises, and failed to reduce drug use Communities of color, particularly Black and Latino populations, have endured the burden of mass incarceration and aggressive policing, despite similar rates of drug use across racial groups Meanwhile, overdose deaths have skyrocketed, and access to treatment remains limited, especially in marginalized communities

The evidence is clear: criminalization worsens outcomes, while public health strategies save lives Harm-reduction programs like syringe exchanges, naloxone distribution, and medication-assisted treatment are proven to reduce disease transmission, overdose deaths, and drug dependency Yet, outdated laws and misplaced funding priorities continue to block widespread adoption.

A real shift is urgently needed Decriminalizing personal drug use, investing in treatment and community services, and ending discriminatory enforcement practices are essential steps Without bold action, the devastating human toll rising overdose deaths, mass incarceration, and deepening inequalities will only grow, leaving already vulnerable communities to suffer even greater consequences

The choice is stark: continue a cycle of punishment and loss, or invest in evidencebased, compassionate solutions that promote health and justice The path forward is clear and the cost of inaction is too high to ignore

1.Earp, B. D., Lewis, J., Hart, C. L., & with Bioethicists and Allied Professionals for Drug Policy Reform (2021) Racial Justice Requires Ending the War on Drugs The American journal of bioethics : AJOB, 21(4), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.18613 64

2 Cummings, A D P , & Ramirez, S A (2021) The racist roots of the war on drugs & the myth of equal protection for people of color UALR L Rev , 44, 453 https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/v ol44/iss4/1

3 Sirin, C V (2011) From Nixon’s War on Drugs to Obama’s drug policies today: Presidential progress in addressing racial injustices and disparities. Race, Gender & Class, 82-99.

4 Ziedenberg, J , & Schiraldi, V (1999) The punishing decade: Prison and jail estimates at the millennium (p 4) Washington, DC: Justice Policy Institute.

5 Vera Institute of Justice (n d ) Causes of mass incarceration Vera Institute of Justice https://www.vera.org/ending-massincarceration/causes-of-massincarceration?utm source=chatgpt.com

6 Palamar, J J , Davies, S , Ompad, D C , Cleland, C M , & Weitzman, M (2015) Powder cocaine and crack use in the United States: an examination of risk for arrest and socioeconomic disparities in use Drug and alcohol dependence, 149, 108–116 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01. 029

7 Smith, B T (2021) New Documents Reveal the origins of America’s war on drugs Times https://time.com/6090016/us-war-ondrugs-origins/

8 Santiago-Negrón, S , & Albizu-García, C E (2003) Guerra contra las Drogas o Guerra contra la Salud? Los retos para la salud pública de la política de Drogas de Puerto Rico [War on Drugs or War against Health? The pitfalls for public health of Puerto Rican drug policy]. Puerto Rico health sciences journal, 22(1), 49–59

9 Gottschalk, M (2023) The opioid crisis: the war on drugs is over Long live the war on drugs Annual review of criminology, 6(1), 363-398 http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurevcriminol-030421-040140

10 Tyndall, M , & Dodd, Z (2020) How Structural Violence, Prohibition, and Stigma Have Paralyzed North American Responses to Opioid Overdose AMA journal of ethics, 22(1), E723–E728 https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2020.723

11 Stone B M (2024) The War on Drugs has Unduly Biased Substance Use Research Psychological reports, 127(4), 2087–2094 https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941221146701

12 Color of Pain (n d ) Criminal Justice – The Drug Policy Alliance http://www.colorofpain.org/criminal-justice

13 Csete, J , Kamarulzaman, A , Kazatchkine, M , Altice, F , Balicki, M , Buxton, J , Cepeda, J , Comfort, M , Goosby, E , Goulão, J , Hart, C , Kerr, T., Lajous, A. M., Lewis, S., Martin, N., Mejía, D., Camacho, A , Mathieson, D , Obot, I , Ogunrombi, A , Beyrer, C (2016) Public health and international drug policy Lancet (London, England), 387(10026), 1427–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00619-X

14 Greenwald, G (2009) Drug decriminalization in Portugal: Lessons for creating fair and successful drug policies. Cato Institute. https://www.hanfplantage.de/images/greenw ald whitepaper.pdf

15 Hughes, C E , & Stevens, A (2010) What can we learn from the Portuguese decriminalization of illicit drugs? The British Journal of Criminology, 50(6), 999-1022

16 Westenberg, J N , Meyer, M , Strasser, J , Krausz, M., Dürsteler, K. M., Falcato, L., & Vogel, M (2023) Feasibility, safety, and acceptability of intranasal heroin-assisted treatment in Switzerland: protocol for a prospective multicentre observational cohort study. Addiction science & clinical practice, 18(1), 15 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-023-00367-0

17 Maghsoudi, N , Tanguay, J , Scarfone, K , Rammohan, I., Ziegler, C., Werb, D., & Scheim, A. I (2022) Drug checking services for people who use drugs: a systematic review Addiction (Abingdon, England), 117(3), 532–544 https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15734

18 Christine, J (2021) Facts and Recommendations: How Cannabis legalization can be used to repair the damage to communities worst affected by the US War on Drugs [Report] https://hdl.handle.net/1813/111103

Writtenby:SebastianTorres

PublishedonlineonJune 17,2025

Introduction

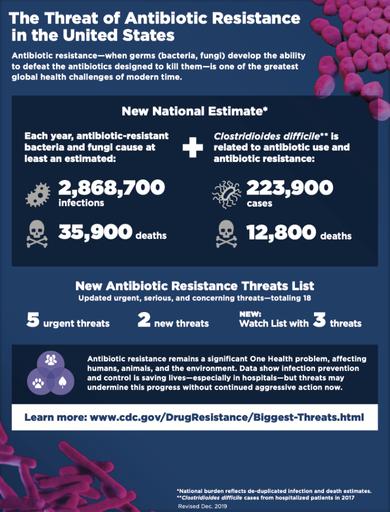

Something interesting that might not receive too much attention is the negative effect and impact that antibiotic-resistant bacteria have on the public health. The overuse and misuse of antibiotics has led to the development of resistant bacterial strains, transforming a once manageable problem into a global health concern Not only has this become a problem worldwide it has the potential to escalate This may potentially lead to higher healthcare costs; longer hospital stays and increased mortality rates.

According to the CDC, at least 28 million people are infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the United States each year, and more than 35,000 people die as a result (Ventola, 2015)

Given the limitations of conventional antibiotics, researchers are exploring new antimicrobial strategies that work through novel mechanisms These include alternative antimicrobial agents capable of inhibiting or killing bacterial growth in ways different from traditional antibiotics.

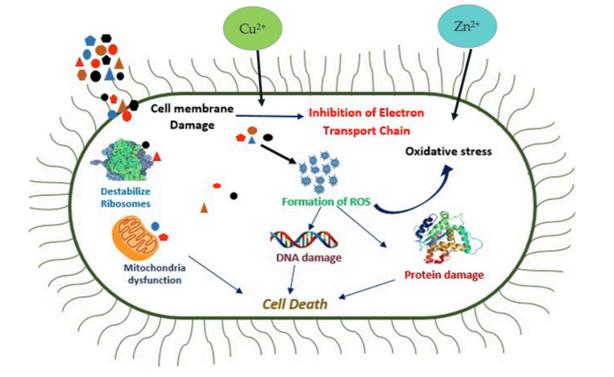

Metals like zinc and copper can be toxic to the cell in sub millimolar concentrations leading to bactericidal effects within the cell Copper toxicity can be attributed to reactive oxygen species, such

Figure 1. Adapted from CDC Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019

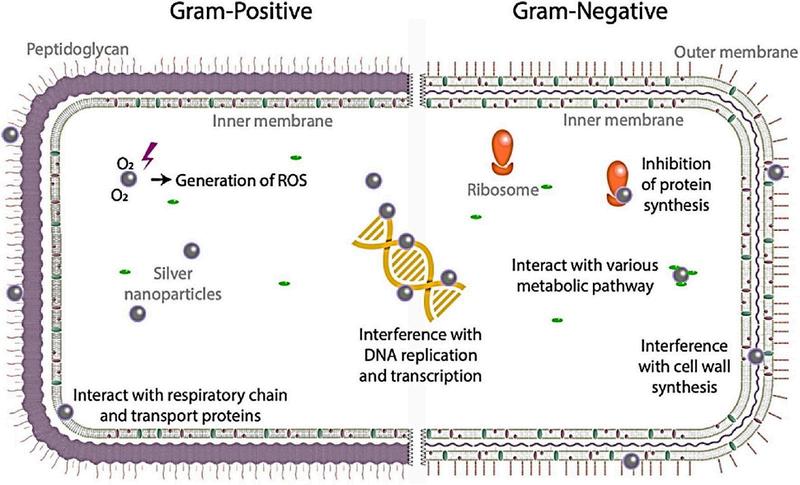

Figure 2. Adapted from Rahman S, Rahman L, Khalil AT, Ali N, Zia D, Ali M, Shinwari ZK Endophyte-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biological applications Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2019 Mar;103(6):2551-2569. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-09661-x. Epub 2019 Feb 5. PMID: 30721330

as hydroxy radical, superoxide ion, and hydrogen peroxide (Djoko, et Al 2015) These free radicals, when accumulated, can cause significant damage by disrupting DNA and nucleic acids Zinc, while generally well tolerated within the cell at low concentrations, can become toxic at elevated levels (Djoko, et Al 2015). Zinc can cause inhibition of key enzymes in the cell Leading to protein denaturation, enzyme inactivation and apoptosis (programmed cell death) (Ye Q, et al 2020).

Silver (Ag) has always been recognized as a strong antimicrobial agent, when reduced to a nano size level, its antimicrobial effects are increased Advancements in nanotechnology have facilitated the developments of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), maximizing their bactericidal properties

Nanoparticles are preferred over basic Ag compounds due to its favorable surface area This high surface area to volume ratio contributes to potent bactericidal activity against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (e g E coli, P aeruginosa, S aureus) (Ferdous Z, 2020)

When microbes are treated with Ag ions their replication capacity is impaired as the Ag ions disrupt phosphorus components in the DNA sequence Ag ions are also able to inhibit phosphate uptake and suppress the growth of E coli, a Gram-negative bacteria This leads to

an efflux of aggregated phosphates, glutamine, proline as well as succinate (Ahmad, et Al 2020)

As AgNP’s enter the cell it affects cellular respiration as well as cell division AgNP’s create free radicals increasing in ROS production The accumulation of ROS damages cellular damages cellular components such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, ultimately triggering cell death Additionally, the positive charge of silver ions enhances membrane permeability contributing to the disruption of nucleic acids and further impairing cellular function (Slavin YN, 2017)

Combination therapy, the use of two or more antimicrobial agents, has showed improvement in addressing antibiotic-resistant bacteria This approach utilizes antimicrobial synergy, where the combined action of multiple agents is greater than their individual effect alone. By enhancing overall treatment efficacy, combination therapy can potentially reduce resistance development and improve patient outcomes.

This strategy offers increased efficacy against resistant bacterial strains, reduced toxicity through lower individual dosages, as well as the ability to target multiple cellular pathways Combination therapies have been successfully applied in the treatment of different infections such as tuberculosis, cancer, and HIV (Fischbach MA, 2011) Furthermore,

Figure 3 Adapted from Ahmad, A S., Das, S S., Khatoon, A., Ansari, M. T., Afzal, M., Hasnain, M. S., & others (2020). Bactericidal activity of silver nanoparticles: A mechanistic review Materials Science for Energy Technologies, 3, 756–769 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mset.2020.10.004

combination therapy can minimize adverse and reduce overall treatment costs, making this approach clinically and economically beneficial

As the global health community continues to struggle with the growing challenges posed by antibiotic-resistant bacteria, the search for effective and sustainable solutions remains imperative Innovative therapies, such as the combined use of toxic metal ions and silver nanoparticles, which together exhibit enhanced antimicrobial activity, offer a promising step forward This emerging therapeutic strategy holds significant potential for preserving the efficacy of existing antibiotics, combating resistant bacterial strains, and most importantly, protecting the public health in the years to come.

1. Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats P T 2015 Apr;40(4):277-83 PMID: 25859123; PMCID: PMC4378521

2. CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 Atlanta, GA: U S Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019

3. Djoko, K. Y., Ong, C. L., Walker, M. J., & McEwan, A G (2015) The Role of Copper and Zinc Toxicity in Innate Immune Defense against Bacterial Pathogens The Journal of biological chemistry, 290(31), 18954–18961. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R115.647099

4 Ye, Q , Chen, W , Huang, H , Tang, Y , Wang, W , Meng, F , Wang, H , & Zheng, Y (2020) Iron and zinc ions, potent weapons against multidrugresistant bacteria. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 104(12), 5213–5227 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10600-4

5 Rahman S, Rahman L, Khalil AT, Ali N, Zia D, Ali M, Shinwari ZK. Endophyte-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biological applications Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2019 Mar;103(6):2551-2569 doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-09661-x. Epub 2019 Feb 5. PMID: 30721330

6 Ferdous Z, Nemmar A Health Impact of Silver Nanoparticles: A Review of the Biodistribution and Toxicity Following Various Routes of Exposure Int J Mol Sci 2020 Mar 30;21(7):2375 doi: 10 3390/ijms21072375 PMID: 32235542; PMCID: PMC7177798

7. Ahmad, A. S., Das, S. S., Khatoon, A., Ansari, M. T , Afzal, M , Hasnain, M S , & others (2020) Bactericidal activity of silver nanoparticles: A mechanistic review Materials Science for Energy Technologies, 3, 756–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mset.2020.10.004

8 Slavin YN, Asnis J, Häfeli UO, Bach H Metal nanoparticles: Understanding the mechanisms behind antibacterial activity. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2017;15(1)

9 Fischbach MA Combination therapies for combating antimicrobial resistance Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2011;14(5):519–23.

Writtenby:GracielaColón-Camuñas,BSc

PublishedonlineonJuly9,2025

Introduction

Did you know there’s a naturally occurring sweetener that doesn’t cause cavities? As someone who loves sweets and studies teeth for a living, discovering xylitol felt like uncovering a sweet exception to the rules of tooth decay Naturally present in many fruits and vegetables, xylitol has become a favorite ingredient in sugarfree gums and oral care products The best part? It’s not just another sugar substitute, it’s a sciencebacked ally in the fight against dental caries, and it might just change the way we think about oral health

Xylitol is a type of natural sweet-tasting carbohydrate that looks and tastes like sugar but acts very differently in the body It’s found in small amounts in things like berries, corn, and mushrooms It has about 40% fewer calories than regular sugar, doesn’t spike blood sugar levels, and most importantly for us dental folks, it doesn’t feed the bacteria that cause cavities

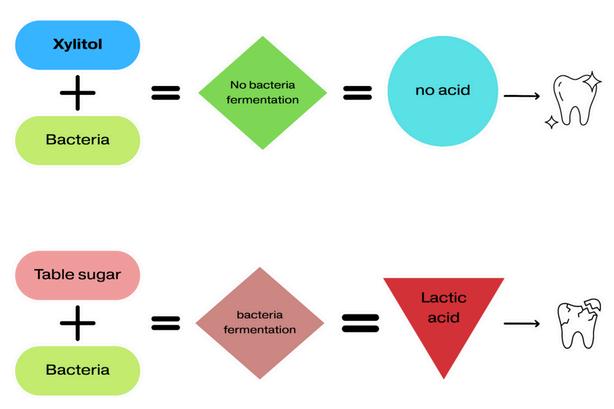

Unlike regular sugar, xylitol doesn’t feed the bacteria that cause cavities! The bacteria most commonly linked to tooth decay are called Streptococcus mutans These bacteria naturally live in our mouths, but when conditions are right for them, they thrive Just like many of us, these bacteria love sugar When we eat foods like bread,

candy, or pasta, our bodies break those carbohydrates down into glucose, which is the main fuel our cells use for energy

Once glucose is available, our cells go through a process called glycolysis which is just a fancy way of saying they split the sugar to start making energy From there, our cells use oxygen to keep breaking things down and produce lots of energy to keep us going

But bacteria like S mutans don’t use oxygen After glycolysis, they switch to a different kind of process that creates lactic acid instead of energy. This acid is super harsh on the teeth and over time, destroys the enamel and leads to cavities

So, here’s the cool part about xylitol: it looks like sugar to the bacteria, but they can’t use it for their metabolism As a result, there’s no growth, no acid, and no damage. Studies have shown that xylitol can reduce S mutans’ ability to stick to surfaces and form plaque and even make them less harmful (Söderling et al, 2006) This helps maintain a more neutral pH in your mouth, which protects your tooth enamel And even better? Xylitol has been shown to support the remineralization of early enamel lesions by making it easier for calcium to reach the deeper layers of the tooth and rebuild the destroyed surface (Miake et al, 2012)

Figure 1. Comparison of xylitol and table sugar metabolism by oral bacteria Xylitol is not fermented by bacteria, preventing acid production and helping maintain healthy teeth. In contrast, table sugar undergoes bacterial fermentation to produce lactic acid, which contributes to tooth enamel demineralization and dental caries

What’s even better is that these benefits have been proven in real people, not just in lab experiments. One of the most impressive examples comes from a study mentioned in a 2022 meta-analysis It followed mothers who chewed xylitol gum for three months after giving birth. Their babies were then followed from birth to age five The result? A 70% reduction in cavities in the kids whose moms used xylitol, compared to the kids whose moms were given either fluoride or chlorhexidine alone: two common dental treatments used to protect against cavities, where fluoride strengthens enamel and chlorhexidine helps reduce bacteria.

That’s a big deal, because preventing cavities at an early age can mean fewer dental visits, less pain, and lower costs later in life.

The same meta-analysis looked at 30 human clinical trials and found that xylitol really does help prevent cavities, but only when used right

The sweet spot? Using it three to five times a day, with a total of 5 to 10 grams per day Other sources indicate 4 to 15 grams per day Less than that (like under 3 4 grams a day or only used once or twice) probably won’t do much

The authors also pointed out that we still need more research on newer xylitol products like gummy bears or syrups, but the evidence we have so far is really promising

Now that you know how xylitol works, here’s how to use it You’ll find it in sugar-free gum, mints, toothpaste, mouthwash, and even some candies or syrups Just check the label, “xylitol” should be near the top of the ingredient list!

To get results, aim for 3–5 uses a day, totaling around 5 to 10 grams per day. That could be a piece of gum or mint right after each meal It’s that simple!

Before you go stocking up on xylitol gum, let’s clear one thing up: xylitol isn’t a magic fix It doesn’t replace brushing, flossing, or regular dental visits it just gives your routine an extra boost Also, not every product that says “xylitol” has enough of it to actually help, so always check the label. Personally, I only use gum that is sweetened with 100% xylitol to make sure I’m getting the real benefits!

Another thing to keep in mind is that some people may experience mild gastrointestinal discomfort if they consume too much xylitol, especially at first And very importantly: xylitol is extremely toxic to dogs, even in small amounts, so keep anything containing it far out of reach of your furry friends

Conclusion

Xylitol might sound too good to be true, but the science backs it up it’s a sweet that actually helps protect your teeth While it’s not a replacement for brushing or flossing, it’s a great way to level up your oral care routine. Whether it’s in gum, toothpaste, or mints, adding a few grams of xylitol each day can make a real difference!

References

1 Söderling, E M , Marttinen, A M , HietalaLenkkeri, A. M., & Tenovuo, J. O. (2006). Xylitol inhibition of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus mutans adhesion, biofilm formation, and viability Journal of Medical Microbiology, 52(5), 471–477. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.05255-0

2 Miake, Y , Saeki, Y , Hata, S , & Yanagisawa, T (2012) Remineralization effects of xylitol on demineralized enamel. Journal of Electron Microscopy, 61(1), 11–15 https://doi.org/10.1093/jmicro/dfs081

3 Muthu, M S , Selvakumar, H , Pani, S , & Kirthiga, M. (2022). Effectiveness of xylitol in caries prevention among children: A systematic review and meta-analysis Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry, 12(3), 271–279

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles /PMC9022379/

4.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. (2023) Policy on the use of xylitol in caries prevention

https://www.aapd.org/media/policies guid elines/p xylitol.pdf

5 Streptococcus mutans, an opportunistic cariogenic bacteria within biofilms (2022) BioMed Research International https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/434283

Writtenby:ArelysA.Angueira-Laureano,BSc

PublishedonlineonJuly28,2025

Introduction

Puberty is the developmental stage where sexual maturity and reproductive capacity are acquired, leading to the adult phenotype The biological process of puberty involves a complex orchestration of hormonal signaling regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis In both sexes, this system is activated by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which stimulates the release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary These in turn drive gonadal production of sex steroids such as estrogen and testosterone (Argente et al, 2023).

Expected pubertal timing in humans has a wide variation In females, puberty typically begins with adrenarche, followed by thelarche (breast development), pubarche (hair growth), and menarche (onset of menstruation) In males, the sequence includes adrenarche, gonadarche (testicular growth and testosterone production), pubarche, and spermarche (onset of sperm production) These physical changes reflect deeper neuroendocrine dynamics that differ by sex Trends indicate an advancement in the typical age range of puberty onset in girls, although the underlying biological reason for this sex difference remains unclear (Argente et al, 2023) This review focuses on the biological and environmental evidence that may explain why females generally enter puberty earlier than males

Sex differences in puberty onset are primarily influenced by variations in kisspeptin expression , neurokinin b (NKB) signaling, and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) regulation These molecular pathways help determine how early the hypothalamic-pituitarygonadal (HPG) axis is reactivated in each sex (Argente et al, 2023)

Kisspeptin, encoded by the KISS1 gene, is a neuropeptide that directly stimulates GnRH neurons and plays a key role in triggering pubertal onset (Semaan et al, 2022) Females show higher levels of Kiss1 mRNA in the arcuate nucleus (ARC), which leads to earlier and more robust GnRH release (Semaan et al, 2022) NKB, a neuropeptide co-expressed with kisspeptin in the ARC, enhances this stimulatory effect and is also regulated differently between sexes (Yao et al., 2022) These patterns of kisspeptin and NKB expression contribute to earlier reproductive axis activation in females (Yao et al, 2022)

IGFBP-5 modulates the availability of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a hormone that supports GnRH neuron activity (Kauffman et al, 2009) In males, elevated IGFBP-5 expression reduces IGF-1 bioavailability, which dampens GnRH stimulation and delays the onset of puberty (Kauffman et al,

2009) This mechanism may help explain why males typically begin puberty later than females (Argente et al , 2023; Kauffman et al , 2009)

Conclusion

Females tend to begin puberty earlier than males due to sex-specific differences in hypothalamic signaling and growth factor regulation. Higher kisspeptin and NKB expression in the female brain leads to earlier activation of GnRH neurons, while greater IGFBP-5 expression in males reduces IGF-1 activity, delaying puberty onset (Semaan et al., 2022; Yao et al , 2022; Kauffman et al , 2009)

In simpler terms, females begin puberty earlier because their brains activate the hormonal systems responsible for sexual development sooner and more strongly than in males Environmental and nutritional factors such as body mass index, rapid early growth, and exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals may further influence these pathways and reinforce the sex difference in timing (Yao et al , 2022) Together, these findings highlight the multifactorial nature of puberty and the interplay between internal and external drivers of its onset

References

1 Argente, J , Dunkel, L , Kaiser, U B , Latronico, A C , Lomniczi, A , Soriano-Guillén, L , & TenaSempere, M (2023) Molecular basis of normal and pathological puberty: from basic mechanisms to clinical implications The Lancet Diabetes & endocrinology, 11(3), 203–216 https://doi org/10 1016/S22138587(22)00339-4

2 Semaan, S J , & Kauffman, A S (2022) Developmental sex differences in the peripubertal pattern of hypothalamic reproductive gene expression, including Kiss1 and Tac2, may contribute to sex differences in puberty onset Molecular and cellular endocrinology, 551, 111654 https://doi org/10 1016/j mce 2022 111654

3.Yao, Z., Lin, M., Lin, T., Gong, X., Qin, P., Li, H., Kang, T , Ye, J , Zhu, Y , Hong, Q , Liu, Y , Li, Y , Wang, J , & Fang, F (2022) The expression of IGFBP-5 in the reproductive axis and effect on the onset of puberty in female rats. Reproductive biology and endocrinology: RB&E, 20(1), 100 https://doi org/10 1186/s12958-022-00966-7

4 Kauffman, A S , Navarro, V M , Kim, J , Clifton, D. K., & Steiner, R. A. (2009). Sex differences in the regulation of Kiss1/NKB neurons in juvenile mice: implications for the timing of puberty American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism, 297(5), E1212–E1221. https://doi org/10 1152/ajpendo 00461 2009

Writtenby:JanPaulGómez-Acevedo,MS

PublishedonlineonAugust4,2025

Summary

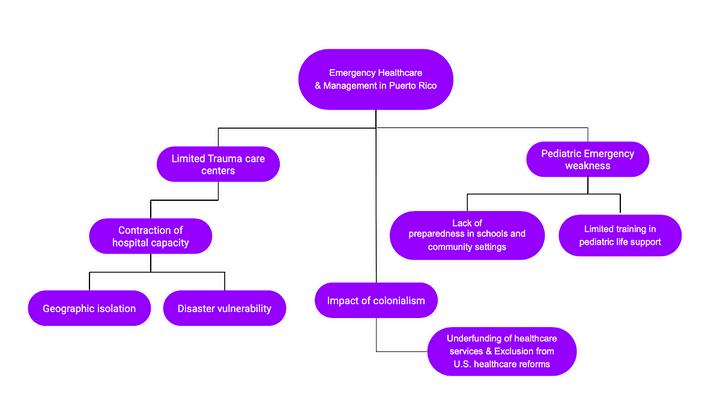

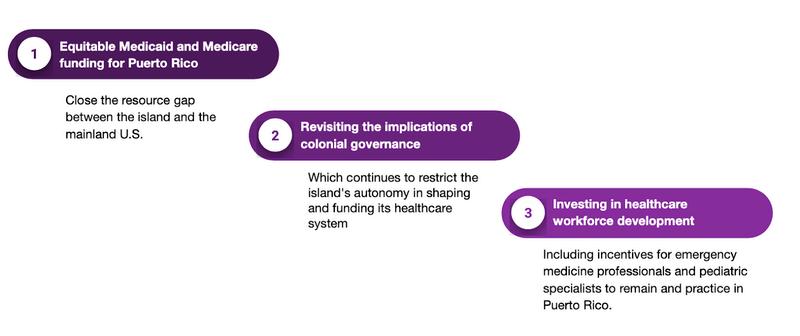

This article specifically analyzes the serious deficiencies in Puerto Rico’s emergency healthcare system, including the lack of a fully accredited Level I trauma center, as well as the broader consequences for public health and disaster preparedness Puerto Rico has more than 3 million US citizens, but no trauma network, which can leave patients without proper care, particularly in rural areas, where delays often turn survivable injuries into preventable deaths The wreckage wrought by Hurricane Maria in 2017 exposed systemic failures in medical infrastructure, including understaffed hospitals, disrupted supply chains, and fragmented emergency coordination These problems persist even in routine emergencies, exacerbated by remoteness, inadequate funding, and unequal access to care

Special attention is given to pediatric emergency preparedness, a neglected sector of healthcare on the island At the 2025 Emergency Preparedness Summit, it was reported that 46% of childcare centers had never conducted emergency drills Many caregivers also lack training in basic lifesaving techniques such as pediatric CPR and the Heimlich maneuver, leaving children especially vulnerable in critical situations These disparities are embedded in Puerto Rico’s colonial status and lack of full political autonomy. The territory receives lower federal reimbursements, was

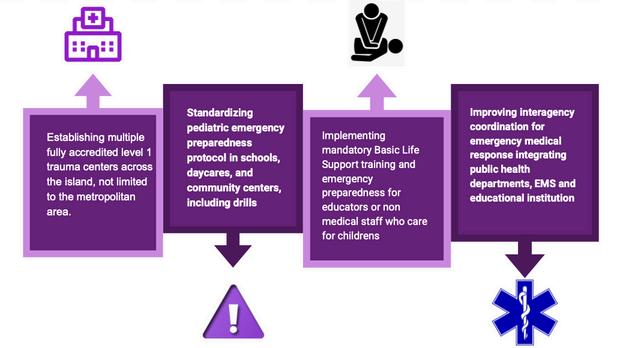

excluded from Medicaid expansion, and has undergone privatized health reforms that have widened the access gap The paper ends with an appeal for broad policy reform. Immediate recommendations include the development of accredited Level I trauma centers, mandatory pediatric emergency training in educational institutions, and the establishment of a centralized trauma registry Long-term solutions require equitable federal funding and a serious reconsideration of the political relationship that constrains Puerto Rico’s healthcare sovereignty In conclusion, this paper argues that Puerto Rico’s health crisis is not the result of unavoidable events but of structural failures Resolving them demands systemic reform, accountability, and sustained investment in health equity and resilience

Introduction

Puerto Rico, home to over 3 million US citizens, currently lacks a fully accredited Level I trauma center, with only one partially established facility located in the metropolitan area In contrast, trauma systems in the mainland United States typically provide definitive care within the critical “golden hour” However, patients in Puerto Rico often experience substantial delays due to geographic isolation, limited infrastructure, and chronic underfunding of healthcare services These systemic shortcomings raise critical concerns regarding the adequacy and equity of the island’s healthcare system This analysis seeks

Figure 1. This example highlights the long distances residents in rural and island municipalities, such as Vieques and Culebra, must travel to reach Puerto Rico’s only trauma center. Many of these areas lack hospitals or even basic Diagnostic and Treatment Centers (CDTs), leaving patients dependent on off-island emergency care

to examine the underlying structural forces contributing to these disparities, identify the key stakeholders responsible, and explore what policy and administrative reforms are necessary to prevent continued, avoidable loss of life (Colón & Sánchez-Cesareo 2019; Rodríguez-Madera et al., 2021)

This concern is not hypothetical; it has already manifested in real crises The devastation caused by recent natural disasters has exposed the severe vulnerabilities of Puerto Rico’s healthcare infrastructure Hospitals were left without power, water, or functional communication systems, and many collapsed under the weight of patient need and logistical isolation Even major academic institutions struggled to provide basic services, relying on improvised systems and overstretched personnel to deliver emergency care. The disaster did not create these weaknesses; it revealed and intensified them As documented by frontline physicians, the island’s lack of disaster preparedness, underfunded facilities, and disconnected care networks placed thousands of lives at risk and forced patients to be transferred off-island for treatment that should have been available locally These failures mirror the same systemic issues that limit access to trauma care daily Without a fully integrated trauma system, equitable funding, and robust emergency planning, Puerto Rico remains perilously unprepared not just for the next hurricane, but for the daily emergencies that continue to cost lives in silence Understanding whathappenedduringHurricaneIrmaandMaria (2017), is essential to understanding why Puerto Rico still lacks a functional, resilient trauma care system and why addressing it is no longer optional,buturgent(Zorrilla,2017)

The lack of a fully accredited Level I trauma center in Puerto Rico reflects a deeper and ongoing contraction of the island’s healthcare infrastructure, particularly hospital-based services From 2010 to 2020, Puerto Rico experienced a measurable decline in the number of hospitals, hospital beds, and surgical procedures across nearly all health regions, with the steepest losses occurring in areas outside the San Juan metropolitan corridor (Figure 1) (Stimpsonetal,2024)

This spatially uneven reduction in care capacity has had significant implications for trauma care access, with many patients in remote or underserved areas facing extended delays for definitive treatment The consequences are especially dire in emergencies where timely intervention is critical to survival As hospital resources continue to shrink due to systemic underfunding, disaster vulnerability, and uneven federal reimbursement policies, the fragility of Puerto Rico’s trauma system becomes increasingly apparent Coordinated health planning, equitable resource distribution, and infrastructurereinforcementareurgentlyneeded to reverse this downward trend and build a trauma system capable of serving the island’s full population(Stimpsonetal.,2024).

Pediatric healthcare readiness is another area of grave concern. The absence of pediatric-specific emergency protocols, limited CPR training among caregivers, and inconsistent disaster preparedness in schools and childcare centers further magnify the risk to children in emergencies(Gómez‐Cortes,2025)

These longstanding gaps in emergency infrastructure and pediatric preparedness are not isolated administrative oversights; they are symptoms of deeper structural inequities To fully understand why Puerto Rico continues to face such critical health system failures, it is necessary to examine the broader sociopolitical context that shapes its public health landscape Colonialism, as a structural determinant of health, offers a powerful lens through which to explore the root causes of the island’s systemic medical vulnerabilities

Puerto Rico’s healthcare deficiencies are not limited to hospitals or trauma centers; they extend into schools, daycares, and communities The lack of pediatric emergency preparedness in Puerto Rico reflects a broader systemic vulnerability within the island’s healthcare infrastructure At the 2025 Emergency Preparedness Summit, Prof Abner Gómez-Cortés, during his presentation on pediatric emergency preparedness, cited:

“If a child cries, they’re breathing, if they breathe, they have a pulse,”

–Doctor Martin de Pumarejo

emphasizing the urgent need for readiness in schools, childcare centers, and community settings (Gómez‐Cortes, 2025) This underscores the need for calm, trained responders; yet many, such as teachers, caregivers, staff members, lack even the minimum qualifications to act effectively This failure echoes the island’s broader trauma care crisis, where delays in care and uncoordinated response mechanism regularly cost lives Without the integration of preparedness drills, healthcare provider training, and public awareness campaigns, especially in pediatric settings, Puerto Rico remains perilously exposed to preventable loss of life, not only in hospitals, but also in classroom and community spaces. Alarmingly, 46% of childcare centers represented at the summit reported not conducting any drills for emergencies such as earthquakes or medical crises, in comparison with the National Center for Education Statistics in the US mainland, which reports that over 90% of public schools annually conduct at least one emergency drill, this includes more than actual medical emergencies, covering bullying, pandemic, lockdown, or fire drills (Waters, 2025) These gaps place children at serious risk during critical events

One of the most significant and historically rooted drivers of Puerto Rico’s public health disparities is U S colonialism As detailed by Pérez Ramos et al., more than a century of political subordination has directly shaped the island’s healthcare system, limiting its capacity to meet the needs of its population Puerto Rico’s status as a U.S. territory has led to chronic underfunding of essential services, including Medicaid and Medicare, which are reimbursed at lower rates than in the states The island has also been excluded from key federal protections and reforms, such as the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion These structural disadvantages have been intensified by the privatization of health services through reforms like “La Reforma” (Puerto Rico Health Reform) (Puerto Rico Department of Health), which prioritized cost control over equitable access to care

In addition, the compounded effects of repeated natural disasters, Hurricanes Irma and María (2017), COVID-19 pandemic (December, 2019) and earthquake 6 4 magnitude (January, 2020), exposed and amplified the fragility of the island’s health infrastructure Each crisis has led to short-term, patchwork solutions rather than long-term investment, leaving healthcare institutions in a state of perpetual recovery This ongoing instability has contributed to a rise in preventable chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and untreated mental illness, disproportionately affecting low-income and marginalized communities

Most critically, Puerto Rico’s limited political power severely restricts its ability to respond autonomously to healthcare challenges Lacking full congressional representation and voting rights in presidential elections, the island struggles to effectively advocate for equitable federal funding and policy reform This absence of self-determination undermines its capacity to build a resilient and responsive healthcare system, leaving the population structurally vulnerable to both everyday medical needs and large-scale emergencies

Addressing health inequities in Puerto Rico requires more than clinical or logistical solutions, it demands a direct confrontation with the colonial frameworks that continue to shape health outcomes on the island.

Discussion

Puerto Rico’s emergency healthcare system is both under-resourced and inequitably structured, particularly when compared to the mainland United States The absence of a fully accredited Level I trauma center, especially outside the San Juan metropolitan area, leaves a significant portion of the population without access to timely, life-saving interventions As emphasized, this systemic shortcoming is not just logistical; it is deeply rooted in historical, economic, and political inequalities that have long shaped the island’s public health landscape

Hurricane María, as a real-world stress test, exposed the fragile nature of Puerto Rico’s medical infrastructure, revealing that the island remains dangerously unprepared for masscasualty events In the absence of non-disaster contexts, geographic isolation, staff shortages, and administrative fragmentation continue to delay critical trauma care This fragility is compounded in pediatric settings, where gaps in CPR training, lack of emergency drills, and limited medical readiness in schools and childcare centers heighten the risk for the island’s most vulnerable population

Furthermore, the role of U S colonialism as a structural determinant of health cannot be understated Chronic underfunding, exclusion from federal healthcare expansions, and limited political autonomy have rendered Puerto Rico’s public health system reactive rather than resilient Policies such as “La Reforma” and privatization of essential services have introduced market-based barriers to care, often prioritizing cost-cutting over quality and accessibility These factors disproportionately

affect low-income, rural, and pediatric populations, those most in need of systemic support

Conclusion

Puerto Rico’s emergency healthcare crisis is not merely a failure of logistics or policy; it is the outcome of deeply entrenched structural and political inequities From the collapse of trauma infrastructure to the inadequate preparation of pediatric care environments, the current system falls short in delivering equitable, timely, and effective medical responses While high-impact events such as Hurricane María have spotlighted these vulnerabilities, they have only intensified long-standing issues that remain unresolved. The persistent lack of a fully integrated trauma care network, particularly in rural regions and pediatric settings, leaves the island dangerously unprepared for both everyday emergencies and large-scale disasters.

Immediate call for action:

Long-term solutions require policy level change, including:

Establishing a centralized trauma registry would provide real-time data on injury trends, response times, and clinical outcomes, informing both clinical care and public health strategy across Puerto Rico (e g National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) managed by the American College of Surgeons, it is the largest repository of U S trauma registry data) Puerto Rican medical schools should require training in trauma triage, pediatric CPR, and disaster response to strengthen both clinical readiness and community preparedness Incorporating research and presentations can further highlight gaps within and beyond hospital settings.

In conclusion, health emergencies must not be viewed as inevitable tragedies, but rather as preventable failures of planning, policy, and equity Puerto Rico deserves a healthcare system that safeguards its people not only in times of disaster, but every day Achieving this demands urgent action, strategic investment, and an unwavering commitment to systemic reform

Seconds Count: Puerto Rico’s Ongoing Emergency Healthcare Crisis

References:

1.Colón HM, Sánchez-Cesareo M. Disparities in Health Care in Puerto Rico Compared With the United States JAMA Intern Med 2016 Jun 1;176(6):794-5 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1144. PMID: 27111567

2 Rodríguez-Madera, S L , Varas-Díaz, N , Padilla, M , Grove, K , Rivera-Bustelo, K , Ramos, J., … & Santini, J. (2021). The impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Rico’s health system: post-disaster perceptions and experiences of health care providers and administrators Global Health Research and Policy, 6(1), 44

3 Zorrilla, C D (2017) The view from Puerto Rico: Hurricane Maria and its aftermath New England journal of medicine, 377(19), 18011803

4 Stimpson JP, Rivera-González AC, Mercado DL, Purtle J, Canino G, Ortega AN Trends in hospital capacity and utilization in Puerto Rico by health regions, 2010-2020 Sci Rep 2024 Aug 1;14(1):17849 doi: 10 1038/s41598024-69055-6 PMID: 39090232; PMCID: PMC11294551

5 Gómez‐Cortes, A (2025, July 10) Pediatric emergency preparedness [Conference session] Emergency Preparedness Summit 2025, San Juan, Puerto Rico https://www.facebook.com/share/v/176oVj JJxD/?mibextid=wwXIfr

6 Waters, S (2025, April 24) 8 types of school emergency drills: A complete guide Coram AI https://www.coram.ai/post/types-ofschool-emergency-drills

7.Ramos, J. G. P., Garriga-López, A., & Rodríguez-Díaz, C E (2022) How is colonialism a socio-structural determinant of health in Puerto Rico? AMA journal of ethics, 24(4), 305-312.

8 Puerto Rico Department of Health (n d ) Medicaid program [Website] Medicaid PR gov https://www.medicaid.pr.gov/

Writtenby:TiffanyFuentes-González,BSc

PublishedonlineonAugust21,2025

Summary

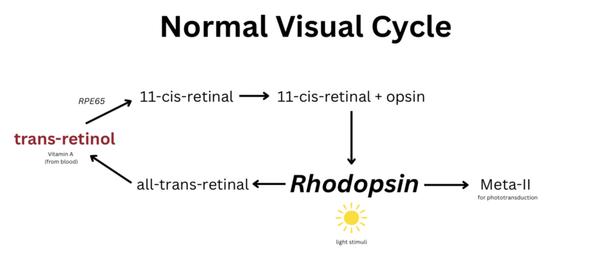

Phototransduction is a light-stimulated process that heavily relies on continuous regeneration of 11-cis-retinal to keep rhodopsin function and adequate visual performance Vitamin A is essential in this process, serving as a precursor of 11-cis-retinal However, it is not naturally produced by the human body A deficiency of this vitamin disruptsphototransductionand can lead to adverse symptoms, such as night blindness.This review explores the downstreamconsequencesof impaired rhodopsin regeneration in vitamin A deficiency (VAD), focusing on photoreceptorstructural and functionalhealth

Studies reviewed examined the role of Vitamin A in the visual system andhow a reduction in rhodopsin can lead to degeneration of photoreceptor outer segments, opsinmislocalization, and eventual photoreceptor death Ultimately, the evidence reinforces that vitamin A is crucial in sustaining retinal health, preserving photoreceptor integrity, and preventing vision loss.

Introduction

Phototransduction is the process by which light is converted into electrical impulses and ultimately processed by the brain An important part of this process is that of the conversion of 11-cis-retinal into all-trans-retinal upon rhodopsin’s absorption of light (Dewett et al, 2021)

This photoisomerization converts rhodopsin into its active form, metarhodopsin II (Meta-II), which initiates phototransduction After serving its function, activated rhodopsin dissociates into retinal and opsin For phototransduction to continue occurring normally, 11-cis-retinal must be regenerated, as shown in Figure 1

Vitamin A is a precursor of 11-cis-retinal, and is not synthesized endogenously, which is why it is crucial to acquire it from the diet (Dewett et al., 2021) Whilethere is extensive knowledgeabout theinitial rhodopsin decrease following VAD, this review focuses on examining the downstream effects onphotoreceptor health specifically related to the impairment of rhodopsin regeneration

This brief literature-based review article synthesizes findings of multiple studies that help answer the question of what the downstream effect of rhodopsin impairment on photoreceptors is Selected sources include a human case report, rodent and Drosophila model studies that examine phototransduction function, rhodopsin levels, and photoreceptor structure under VAD conditions

Figure 1. Simplified schematic of the normal visual cycle Vitamin A (trans-retinol) obtained from blood circulation is converted by RPE65 enzyme into 11-cis-retinal. This molecule combines with opsin to form rhodopsin. Upon light stimulation, rhodopsin is activated (Meta-II), causing isomerization of 11-cis-retinal into all-trans-retinal, which is then recycled to sustain the phototransduction cascade

The first study reviewed investigates the effect of vitamin A deficiency (VAD) in rat retinas, both structurally andbiochemically Carter-Dawson et al (1979) showed that, by the ninth week of deficiency, retinas lacking sufficient vitamin A displayed only 20% of control rhodopsin levels This reduction not only impaired the phototransduction process but also led to photoreceptor cell death by week 16, specifically the distal third outer segment of rods This degeneration was attributed to the instability of outer segment discs caused by insufficient rhodopsin These findings suggest that VAD not only disrupts 11-cis-retinal regeneration but also that this deficiency can rapidly progress from biochemical disruptions to structural, irreversible degeneration within weeks

Carter-Dawson et al ’s (1979) findings were confirmed over four decades later by Jevnikar et al (2022) reinforcing the consistency of results across time and methodology. Jevnikar et al. (2022) reported a case where an elderly patient presented with worsening nyctalopia due to a deficiency in vitamin A Once an optical coherence tomography was performed, it revealed rod outer segment degeneration; rod function had also been noted to decrease after two months of symptom onset, followed by a dysfunction in cones after eight months. Remarkably, normal retinal structure was observed after adequate supplementation of vitamin A, confirming reversibility of symptoms and damage is possible if treated urgently.

At a molecular level, Kumar et al (2022) reported that VAD directly impacts phototransduction machinery, particularlyproteins involved in the amplification of a visual signal Since amplification is crucial in a photoreceptor’s

response to light stimuli, disruption in machinery significantly compromises their function Thus, VAD weakens vision not only by reducing rhodopsin levels, but also by preventing proper signal transduction

Extending these findings, Ramkumar et al (2021) further demonstrated that chronic vitamin A deficiency disturbs the balancebetween opsin and 11-cis-retinal, leading to opsinmislocalizationand consequentialphotoreceptor dysfunction Unbound opsin accumulates due to the reduction of 11-cis-retinal formation in VAD, exacerbating photoreceptor stress and death Altogether, these findings, reinforced by Sajovic et al (2022), show that VAD initiates a detrimental cascade, beginning with impaired rhodopsin regeneration and ultimately resulting in widespread photoreceptor dysfunction and permanent degeneration

Chronic vitamin A deficiency (VAD) has consistently been shown to affect photoreceptor structure and function in several ways VAD impairs rhodopsin regeneration in the process of phototransduction, but this only represents the initial step in a deeper, complex cascade Studies demonstrate how reduced rhodopsin levels lead to disruption of pathways essential for photoreceptor survival and function; its deficiency may lead to degeneration of photoreceptors’ outer segments In addition, VAD creates an imbalance between chromophore and opsin, caused by the inability to regenerate chromophores, which severely affects electrical responses of photoreceptors to light stimuli, further contributing to their functional

impairment Over time, prolonged deficiency can lead to permanent photoreceptor degeneration and consequential visual impairment (Sajovic et al , 2022)

It is crucial to note that studies examined in this review did not include humans, which means further research must be done on this topic

To directly answer the question initially posed: structurally,VAD’s effect on rhodopsin leads to outer segment degeneration and opsinmislocalizationwhilein terms of survival, it causes photoreceptor dysfunction, degeneration, and eventually, death

1 Dewett, D , Lam-Kamath, K ,Poupault, C , Khurana, H., & Rister, J. (2021). Mechanisms ofvitamin A metabolism and deficiency in the mammalian and fly visual system Developmental Biology, 476, 6878.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2021.03.013

2 Carter-Dawson, L , Kuwabara, T , O’Brien, P J & Bieri, J G Structural and biochemical changesin vitamin A–deficient rat retinas (1979). PubMed. https://pubmed ncbi nlm nih gov/437947/

3 Jevnikar, K , Šuštar, M , Kozjek, N R ,Štrucl, A M , Markelj, Š ,Hawlina, M , & Fakin, A (2022)

Disruption of the outer segments of the photoreceptors on optical coherence tomography as a feature of vitamin A deficiency Retinal Cases & Brief Reports, 16(5), 658–662 https://doi org/10 1097/icb 00000000000 01060

4 Kumar, M , Has, C , Lam-Kamath, K ,Ayciriex, S., Dewett, D., Bashir, M.,Poupault, C., Schuhmann, K ,Knittelfelder, O , Raghuraman, B K , Ahrends, R , Rister, J , &Shevchenko, A (2022) Vitamin A deficiency alters the phototransduction machinery and distinct Non-Vision-Specific pathways in the drosophila eye proteome Biomolecules, 12(8), 1083.https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12081083

5 Ramkumar, S , Parmar, V M , Samuels, I , Berger, N A , Jastrzebska, B , & V on Lintig, J (2021) The vitamin A transporter STRA6 adjusts the stoichiometry of chromophore andopsins in visual pigment synthesis and recycling Human Molecular Genetics, 31(4), 548–560 https://doi org/10 1093/hmg/ddab267

6 Sajovic, J , Meglič, A , Glavač, D , Markelj, Š ,Hawlina, M , & Fakin, A (2022) The role ofvitamin A in retinal diseases International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(3), 1014 https://doi org/10 3390/ijms23031014

Writtenby:MiaSaraPérezSalvá

PublishedonlineonAugust29,2025

“When a system needs change, settling for the same methods out of tradition is no longer viable”

- Dr Jorge Martínez Trabal, Puntos Claves: La disrupción positiva al sistema de salud en Puerto Rico

I was recently revisiting Puntos Claves, a book I had picked up some time ago, and the line quoted above struck me again with urgency Dr Jorge Martínez Trabal, a vascular surgeon based in Ponce, Puerto Rico, is not only known for his clinical expertise but also for his leadership as Program Director of the General Surgery Residency at Hospital Episcopal San Lucas and his contributions as a professor at Ponce Health Sciences University Internationally recognized for contributing to the development of the Hybrid Venous Thrombectomy procedure, a groundbreaking intervention for treating blood clots, he has paired innovation with a strong commitment to public health and equitable care on the island As both a physician and health policy advocate whose work has shaped recent debates on Puerto Rico’s healthcare crisis, Dr Martínez Trabal challenges us to embrace “positive disruption” His words speak directly to the persistent structural barriers that define Puerto Rico’s healthcare system and how they unfold daily in hospitals, clinics, and communities across the island

This reorganization of Puerto Rico’s healthcare system is not merely a response to crisis, but a necessary shift toward equity and sustainability The changes being proposed are intentional, rooted in fairness, access, and long-term resilience As someone who has navigated the system both as a patient and as a student aspiring to contribute to medicine, I know firsthand how these systemic gaps translate into live realities: long waits in transfusion centers at the local oncological hospital, packed emergency rooms, entire municipalities without specialists, and an ever-present fear of what will happen when the next disaster arrives To me, transformation is more than a policy matter, but a question of survival and dignity for our communities

Figure 1: Jorge Martínez Trabal, Puntos Claves; publish date 2023. Reproduced from https://puntos-clave.com/

Puerto Rico’s healthcare system is increasingly overwhelmed by rising demand, declining hospital capacity, and a shrinking medical workforce Hospital infrastructure has weakened over the past decade, while demand for services, especially in the aftermath of disasters, has intensified Following Hurricanes Irma and María, the island saw a surge of infectious diseases, from leptospirosis linked to contaminated floodwaters to respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses caused by prolonged power outages and lack of clean water At the same time, mental health claims soared In municipalities such as Caguas and Ponce, clinics reported unprecedented spikes in anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder, with wait times for psychiatric care stretching for months (Santiago et al , 2024; Chandra et al , 2021) These cases underscore how disasters do not just damage physical infrastructure: they fracture the very fabric of community well-being, leaving the most vulnerable patients without timely care

Figure 2. Patient waiting for medical assistance

Retrieved from https://www.statnews.com/2016/10/27/doctorsflee-puerto-rico/

At the same time, physician migration continues to erode the system. Nearly 500 doctors leave the island each year, more than the number trained locally, creating deep regional disparities Some municipalities lack specialists altogether (WLRN News, 2023). Recent studies have warned that this uneven landscape, if unaddressed, will further undermine equitable access to care (RodríguezDíaz et al., 2024; Santini-Domínguez et al., 2025).

Compared with the U S Virgin Islands and Guam, which face similar shortages and dependency on federal funding (Hall et al , 2018; Stolyar et al., 2021), Puerto Rico’s situation underscores the structural commonalities across U S territories: fragile health

infrastructure, dependence on off-island referrals, and reliance on a workforce that is constantly in flux.

Temporary federal relief, such as the increase in Medicaid funding through FY2027, has provided short-term stability Yet the looming “funding cliff” in 2028 raises alarms about sustainability Locally, in May 2025, Governor Jennifer González announced over $24 million in funding for medical resident retention and pledged 60% of the general budget to healthcare, education, and public safety (AP News, 2025) These measures signaled political will, but frustration remains widespread During a 72-hour blackout earlier that year, hospitals and emergency systems struggled to function: an acute reminder that outdated infrastructure and bureaucratic inefficiencies cannot be solved by pledges alone

Healthcare professionals, especially younger physicians, continue to face discouraging realities: reimbursement rates that are sometimes less than half of U S averages (Roman, 2015), underfunded facilities, and limited institutional support These factors weigh heavily in the decision to migrate Stakeholders have proposed strengthening rural health networks, expanding telemedicine, and creating better residency incentives While promising on paper, implementation consistently lags behind proposals, revealing a gap between political rhetoric and on-theground realities Without meaningful investment and accountability, the cycle of short-term fixes will persist

Figure 3 Headlight illuminate cobblestone streets in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico during island-wide blackout Retrieved from https://www npr org/2025/04/17/g-s160823/power-blackout-hits-all-of-puerto-ricoas-residents-prepare-for-easter-weekend.

In Puntos Claves, Dr. Martínez Trabal does not prescribe a singular solution but instead challenges clinicians, policymakers, and citizens alike to reconsider how we define progress His call for positive disruption is about building a system rooted not just in tradition, but in creativity, adaptability, and equity This call specifically resonates when viewed alongside the realities of Puerto Rico’s healthcare crisis: the outward migration of specialists, the resilience of hospitals in the wake of blackouts, and the everyday perseverance of communities rebuilding after disasters What makes the book so timely is that it does not shy away from the complexity of healthcare reform It recognizes that transformation is not just about policy but mindset Placing yourself in a position of questioning: What kind of system are we building, and for whom? If you are looking for a thoughtful, well-grounded exploration of the ideas behind health system transformation in Puerto Rico, Puntos Claves is worth your time It is a book that does not just diagnose the problem but invites us as citizens to imagine a healthier, more resilient future

Puerto Rico’s challenges are real, but so is its potential Across the island, healthcare workers, researchers, and communities are already leading innovation Projects such as Proyecto Arbona, Iniciativa Comunitaria, and PRCONCRA show that models of community-centered healthcare can thrive even within strained systems. The question now is whether our political, financial, and infrastructural systems will support these efforts In this season of reflection and rebuilding, perhaps the greatest opportunity lies not in returning to what once was, but in having the courage to build what could be

1 Martínez Trabal, J (2023) Puntos Claves: La disrupción positiva al sistema de salud en Puerto Rico. Editorial Raíces.

2 Chandra, A , Marsh, T , Madrigano, J , Simmons, M M , Abir, M , Chan, E W , Nelson, C (2021) Health and social services in Puerto Rico before and after Hurricane Maria. Rand Health Quarterly, 9(2), 10 https://doi org/10 7249/RR2603

3 Santiago, L M , et al (2024) Spatiotemporal analysis of post-disaster infectious and mental health conditions in Puerto Rico Scientific Reports, 14(1), 8123 https://doi org/10 1038/s41598-025-89983-1

4 WLRN News (2023, December 4) Puerto Rico’s mortality rate worsening as the island’s health care system collapses. https://www wlrn org/health/2023-12-04/puertorico-mortality-rate-healthcare-system

5 Rodríguez-Díaz, C E , et al (2024) Racialized structural inequities and health outcomes in Puerto Rico American Journal of Public Health, 114(2), 160–162 https://doi org/10 2105/AJPH 2024 307585

6. Santini-Domínguez, R., Martinez-Trabal, J., & Gonzalez-Diaz, G (2025) Puerto Rico’s specialist crisis A wake-up call for health equity and action JAMA Health Forum, 6(6), e251949 https://doi org/10 1001/jamahealthforum 2025 19 49

7 Hall, C , Rudowitz, R , Artiga, S , & Lyons, B (2018) One year after the storms: Recovery and health care in Puerto Rico and the U S Virgin Islands Kaiser Family Foundation https://www kff org/report-section/one-yearafter-the-storms/

8 Stolyar, L , Tolbert, J , Corallo, B , Rudowitz, R , Sharac, J , Shin, P , & Rosenbaum, S (2021) Community health centers in the U S territories and Freely Associated States Kaiser Family Foundation https://www kff org/reportsection/community-health-centers-in-the-u-sterritories-and-the-freely-associated-statesissue-brief/

9 Associated Press (2025, May 12) Puerto Rico governor pledges to improve power grid after repeated outages https://apnews com/article/d966a3dc81920c1ffa 4b231b7e2bc86b

10 Roman, J (2015) The Puerto Rico healthcare crisis Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 12(12), 1760–1763. https://doi org/10 1513/AnnalsATS 201508-531PS

11 Santiago-Santiago, A J , Rivera-Custodio, J , Grove, K (2024) Puerto Rican physician’s recommendations to mitigate medical migration Health Policy Open, 7, 100124 https://doi org/10 1016/j hpopen 2024 100124