anthroposophy.org

personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century

a quarterly publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America – summer issue 2013

Creating a House for Peace

To Enkindle the Soul of Another Music as a Threshold Experience

100 Years of the Goetheanum

The Blue Star of Individuality

Rudolf Steiner & the Atom

Sacred Economics

“Coney Island” (egg tempera, detail)

by Douglas Safranek

Research . . . in practice at Threefold Educational Center

August 14–18, 2013

September 19–22, 2013

The Challenge of Objectivity in Spiritual Research

2013 Living Questions Research Symposium

Are there ways of objectively investigating the world of soul and spirit? Dive into this question with speakers and workshop leaders Michael D’Aleo, Laura Summer, Gerald Karnow, Anneliese Davidson, Hans Shumm, Gary Lamb, and Laurie Portocarrero. Ample time for conversation and sharing

www.threefold.org/research

Starting October 19, 2013

The Art of Acting: Drama as a Path of Inner Development

A One-Year Course

Led by Laurie Portocarrero with David Anderson, Laura Geilen and Barbara Renold

Explore the wellsprings of human emotion using the most universal instrument of all: the human body and voice. Ten weekend workshops from October to June.

www.threefold.org/artofacting

The Souls’ Awakening: Taking Responsibility for Destiny

2013 Mystery Drama Conference

Featuring two performances of Rudolf Steiner’s fourth mystery drama, plus talks by John Alexandra, Matthew Dexter, Daniel Hafner, Herbert O. Hagens, Laurie Portocarrero, Barbara Renold, Stephen Usher, and Sherry Wildfeuer, conversation groups, acting workshops, and more.

www.threefold.org/awakening

August 8–17, 2014

From the Portal of Initiation to the Souls’ Awakening

2014 Mystery Drama Conference

The Threefold Mystery Drama Group will perform Rudolf Steiner’s four Mystery Dramas, the first time all four have been presented together, in English, outside of Dornach. The performances will be embedded in a conference that will explore the dramas in relation to the future of the anthroposophical movement.

www.threefold.org

June 24–28, 2014

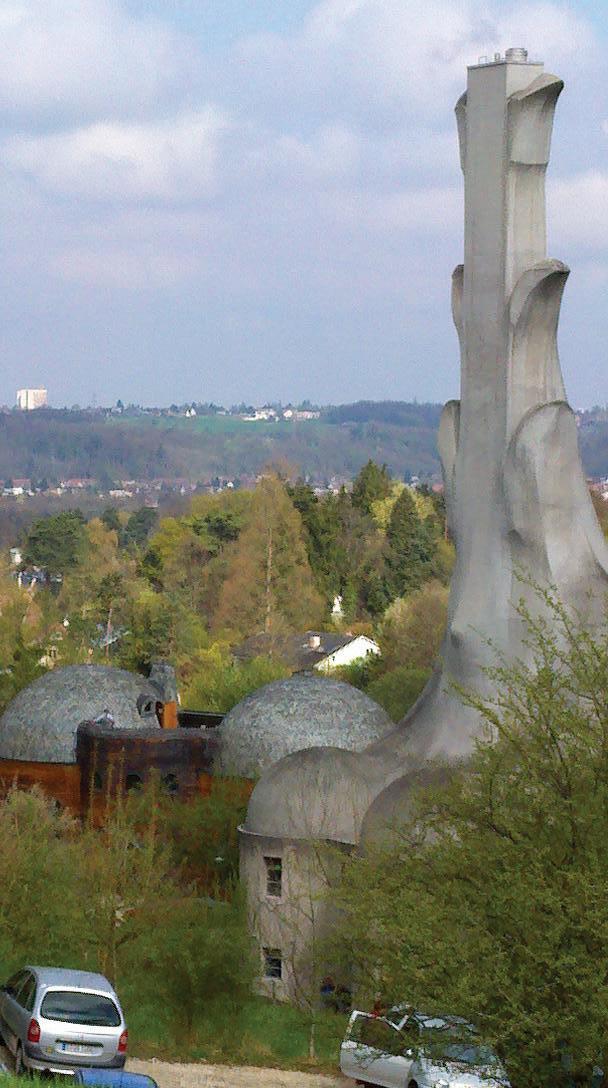

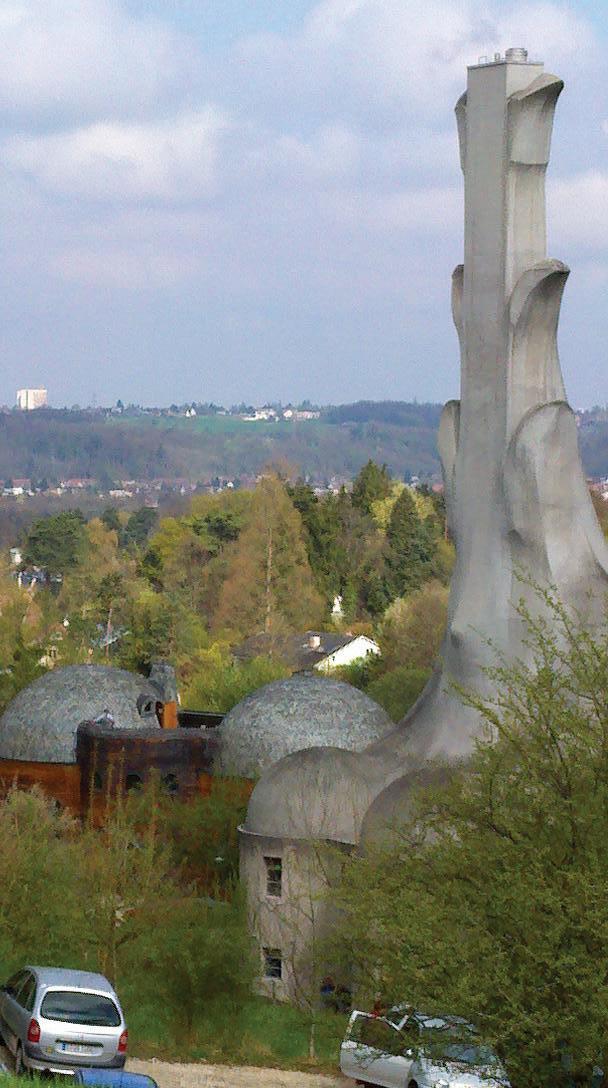

InPower

An Event for Young Adults

November 10–16, 2013

Reflections, Refractions, Reversals

Painting course with Deborah Lothrop

When we explore and pursue the most primal activities of light and darkness, we inevitably arrive at the mysteries of reflection, refraction and reversal. In this course, we will conduct a few simple experiments to apply what we observe in painting.

www.threefold.org/events

Ages 18–36

Can we strengthen that place that speaks from inner authority, that stands strong in its heartfelt convictions? We will work together to strengthen our own voices, inwardly and outwardly, through presentations, artistic work and conversation.

www.inpower2014.eventbrite.com

EDUCATIONAL CENTER

Hungry Hollow Rd. Chestnut Ridge, NY 10977 845-352-5020

260

info@threefold.org

I believe that miso belongs to the highest class of medicines, those which help prevent disease and strengthen the body through continued usage. . . Some people speak of miso as a condiment, but miso brings out the flavor and nutritional value in all foods and helps the body to digest and assimilate whatever we eat. . .

—Dr. Shinichiro Akizuki, Director, St Francis Hospital, Nagasaki

—Dr. Shinichiro Akizuki, Director, St Francis Hospital, Nagasaki

We are a Rudolf Steiner inspired residential community for and with adults with developmental challenges. Living in four extended-family households, forty people, some more challenged than others, share their lives, work and recreation within a context of care.

Daily contact with nature and the arts, meaningful and productive work in our homes, gardens and craft studios, and the many cultural and recreational activities provided, create a rich and full life.

For information regarding placement possibilities, staff, apprentice or volunteer positions available, or if you wish to support our work, please contact us at:

WOOD-FIRED HAND-CRAFTED MISO Nourishing Life for the Human Spirit since 1979 unpasteurized probiotic certified organic SOUTH RIVER MISO COMPANY C onway , M assa C husetts 01341 • (413) 369-4057

www.southrivermiso.com

PO Box 137 • Temple,

•

603-878-4796 • e-mail: lukas@monad.net lukascommunity.org

residential community for adults with developmental challenges • COMMUNITY SPIRIT • • THE ARTS • • MEANINGFUL WORK • • RECREATION •

NH

03084

A

Job Opening – Development Director

The Anthroposophical Society in America is seeking a Development Director who will assist with the growth and further development of the Society. In the past year, the Society has held a colloquium involving leaders in the anthroposophical movement, as well as intensive meetings with the Council of Anthroposophical Organizations, the Collegium of the School for Spiritual Science in North America, and the Youth Section. We have been a sponsor for last fall’s conference of the Biodynamic Association and cosponsored a conference with the Association of Waldorf Schools in North America. We are currently planning co-sponsorship with other anthroposophical organizations. It is a time for initiative and growth and we are looking to professionalize our work and truly become a heart organ serving Anthroposophia. The first step in this movement toward professionalization is the hiring of a Development Director who is enthusiastic about this mission. A full description of the position and its responsibilities may be found here:

www.anthroposophy.org/development.html

Please share this information with others who may be interested.

Immerse Yourself in the Depth of Waldorf Education RUDOLF STEINER COLLEGE A Center for Waldorf Teacher Education, Transformative Learning, and the Arts www.steinercollege.edu/lilipoh 916-INFO-RSC•Fair Oaks and San Francisco, CA Full-time, two-year imersion program steeped in arts and anthroposophy Part-time, weekend, summer courses, MA option Programs in Early Childhood, Grades and High School Beautiful California Campus with Dorms and Biodynamic Farm Master teachers with a wealth of experience See Christ Differently The

more at thechristiancommunity.org Part-Time & Full-Time Training Educational Training Public Courses and More Eurythmy Spring Valley 260 Hungry Hollow Road, Chestnut Ridge, NY 10977 845-352-5020, ext. 13 info@eurythmy.org www.eurythmy.org Consider a Career in Eurythmy

Christian

Community is a world-wide movement for religious renewal that seeks to open the path to the living, healing presence of Christ in the age of the free individual. Learn

Contents Features 16 initiative! 16 Creating a House for Peace, by Lori Barian 21 To Enkinde the Soul of Another, by Laurie Clark & Joan Treadaway 24 A Search for the Medical Understanding of Autism, by Basil Williams, MD 25 Raoul Goldberg’s Addictive Behavior, review by Meg Spencer Gorman 26 Enter Light—Voices from Prison, review by Robert Black 28 A New Impulse in Drama for the Anthroposophic Arts, by Marke Levene 30 arts & ideas 30 Music as a Threshold Experience, by Frederick Amrine 34 The Goetheanum 1913-2013 38 Frank Chester: Imagining a Goetheanum-West, by John Beck 39 Peter Stebbing’s The Goetheanum Cupola Motifs of Rudolf Steiner, review by David Adams 42 The Blue Star of Individuality, by C.T. Roszell 47 news for members & friends 47 The Society’s Rudolf Steiner Library, an Evolving Story 49 Anne Mendenhall, 1930-2013 50 David Spear Mitchell, 1945-2012 51 Lotte K. Emde, 1916-2013 52 Alicia Stewart Busser, 1916-2013 52 Members Who Have Died – New Members 53 An Important Reformation and Its Consequences for a Renaissance, by Nathaniel Williams 60 Rudolf Steiner Library New Book Annotations

eviews 7 being human digest 12 Charles Eisenstein’s Sacred Economics, review by Christopher Schaefer 14 Keith Francis’s Rudolf Steiner & the Atom, review by Frederick J. Dennehy 15 Frank John Ninivaggi’s Biomental Child Development, review by K. David Schultz

Notes, r

The Anthroposophical Society in America

General Council Members

Torin Finser (General Secretary)

Virginia McWilliam (at large)

Carla Beebe Comey (at large)

John Michael (at large, Treasurer)

Regional Council Representatives

Ann Finucane (Eastern Region)

Dennis Dietzel (Central Region)

Joan Treadaway (Western Region)

Marian León, Director of Administration & Member Services

being human

is published four times a year by the Anthroposophical Society in America

1923 Geddes Avenue

Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1797

Tel. 734.662.9355

Fax 734.662.1727

www.anthroposophy.org

Editor: John H. Beck

Associate Editors:

Judith Soleil, Fred Dennehy

Cover design: Seiko Semones (S2 Design)

Layout: John Beck, Seiko Semones

Please send submissions, questions, and comments to: editor@anthroposophy.org or to the postal address above, for our Fall 2013 issue by 9/1/2013.

©2013 The Anthroposophical Society in America. Responsibility for the content of articles is the authors’.

from the editors

What Human Beings Do

Our cover is from a painting-in-progress by New York City artist Douglas Safranek, who works in the very lively but painstaking medium of egg tempera. It’s a summer image, Brooklyn’s famous Coney Island, and in summer Earth breathes out and we work with growing things or “vacate” a bit. Real enjoyment is not trivial. At an old amusement park human beings engaged the foundational body senses: balance, movement in space, well-being. Behind this lighter side of human experience is also a touch of the mysterious and magical folk memories of the ancient mystery schools where, according to Rudolf Steiner’s research, a youthful humanity was being trained to meet the physical world and its experiences. Now, with wild rides and laughter, are we trying to get free of the physical?

Sections. In our third year as being human, we’re organizing our content with a new look to guide you through sections. In the Spring issue several articles came together as an initiative! section. This time we add arts & ideas The words note our three fields of consciousness: we think, we take action, we feel and express ourselves—toward ideals of truth, goodness, beauty. Without false optimism, Rudolf Steiner and anthroposophy embrace a fundamental confidence in the human being. This stands in contrast to a view of humanity as horribly muddled if not malignant—a picture justified by a century of enormities from 1914 forward. Do our misdeeds prove that we are bad? Steiner pointed toward freedom as essential now for human development. And freedom means that we can fall as far as we can rise. The falls have been steep. To choose to rise is more and more essential. Even dreadful current events give strong images of humanity rising. After the shootings at a Connecticut school late last year a special-ed teacher was found covering and hugging a child; both were dead. Yet the mother was comforted because her child, touched by autism, only felt really safe when held tight. In her own last moments this teacher thought to be sure that this small boy felt safe. We are left this image alongside that of the lost young man who took their lives. Articles in this issue touch on these questions. We are not yet fully human, said Dr. Steiner, in one of his thousands of lectures. We must conceive of something higher, and exert ourselves to become that something higher. And people do, in tragic brief “moments of truth” and in long lives of service. Both sections speak to our aspirations. Our third main section is now more clearly named “News for Members and Friends of the Anthroposophical Society in America.” There you’ll find

How to:

receive being human, contribute, and advertise

Copies of being human are free to members of the Anthroposophical Society in America (visit anthroposophy.org/membership.html or call 734.662.9355).

Sample copies are also sent to friends who contact us (address below).

To contribute articles or art please email editor@anthroposophy.org or write Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104.

To advertise contact Margaret Wessel Walker at 734-662-9355 or email advertising@anthroposophy.org

6 • being human

being human digest

reports of life and activity in the Society, along with special essays. This issue includes a considered assessment by Nathaniel Williams on page 53: “An Important Reformation and its Consequences for a Renaissance.”

John Beck

Each of the three books reviewed for the library in some way explores the relation of Rudolf Steiner’s work to other contemporary disciplines.

K. David Schultz reviews Biomental Child Development: Perspectives on Psychology and Parenting, by Frank Ninivaggi, M.D., a Yale psychiatrist and longtime student of Rudolf Steiner. Dr. Schultz looks at this integrated perspective on the details of child development and parenting in light of three modern classics, von Bertalanffy’s General System Theory, Karl Ernst Schaefer’s Toward a Man-Centered Medical Science, and Martin Buber’s I and Thou. The reviewer finds that current scientific understanding of child development should be grasped first on its own terms, and then integrated into the general anthroposophical world view.

Christopher Schaefer discusses Charles Eisenstein’s Sacred Economics: Money, Gift and Society in the Age of Transition, focusing on the author’s radically nontraditional approach and comparing it favorably with other contemporary economic critiques, such as David Korten’s When Corporations Rule the World. Dr. Schaefer urges us to study Eisenstein’s book not only for its analytical incisiveness, but as a program for the future. Some of the ideas in Sacred Economics are developed further in overtly anthroposophical works such as Martin Large’s Commonwealth, Christopher Houghton Budd’s Finance at the Threshold, Gary Lamb’s Associative Economics, and Steiner’s far-reaching World Economy.

My review of Rudolf Steiner and the Atom, by Keith Francis, explores the fascinating relationship between anthroposophy and the quantum revolution, which began in earnest in 1925, the year of Steiner’s death. While Mr. Francis discerns no direct relationship between quantum physics and the anthroposophical approach to reality, in view of the steadfast resistance of the quantum sciences to determinism and reductionism he leaves open the possibility of a pathway that may eventually lead, through the efforts of others, to a science of the spirit.

Frederick J. Dennehy

“being human digest” briefly notes news and ideas from a wide range of holistic and human-centered cultural initiatives. Send suggestions to editor@anthroposophy. org or “Editor, being human, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI, 48104.”

Resea R ch

More Living Questions

Spring and fall, two events have become staples of the research culture of the anthroposophical life in America. SteinerBooks Spiritual Research Seminar dealt with basics this past March, and the event at New York University was stronger than ever. In September Threefold Educational Center in Chestnut Ridge, NY, continues its Living Questions Research Symposium, this year with keynotes from Michael D’Aleo of the Saratoga Experiential Natural Science Research Institute (SENSRI) and the Waldorf School of Saratoga Springs, NY; Gerald Karnow, MD of the Fellowship Community and the Otto Specht School, Chestnut Ridge, NY; and Laura Summer, artist, author, and co-founder of Free Columbia, Hillsdale, NY.

Link: www.threefold.org/research

summer issue 2013 • 7

BDA-ad-being-human-sept-2012:Layout 1 9/27/12 10:18 AM Page

being human digest

Wa Ldo R f e ducation

aWsna conference, new torin finser Book

In June in Austin, Texas, the Anthroposophical Society in America co-sponsored the AWSNA summer conference, always a rich event. General Secretary Torin Finser is a writer and educator of educators who is well-known to the Waldorf community. He participated throughout the conference and brought a new book from AWSNA Publications: Finding Your Self: Exercises and Suggestions to Support the Inner Life of the Teacher. The table of contents is thought-provoking in itself:

Silence: The Gift of the Gods

From Nature to the Human Soul and Back Again

The Importance of Not Knowing Place

Morning and Evening

Finding Our Inner Observer

The Two Teacher Meditations

Membership in the Anthroposophical Society

Time Can Heal Wounds

The Human Being as Fulcrum in the Midst of Contending Forces

Waldorf Education

Judgments

Youth

Appendix: Calendar of the Soul: A Commentary by Karl König

A short statement from the back of the book suggests the spirit of what To rin brought to the conference: Society demands so much of our teachers today. Schools are expected to deal with a host of social needs, often without adequate funding and support. Many politicians think the solution is to raise standards through additional testing, common core curriculum, and increased scrutiny of teacher performance. The external pressures on teachers and schools are increasing each year, yet few ask the teachers, “What do you need?” Many studies have shown that the single most important factor in education is the teacher. In Waldorf schools, teachers are encouraged to grow professionally by cultivating inner resources. This book is intended to encourage teachers to take care of themselves, meditate, and become a source of inspiration for our students so that together we can address the urgent needs of our time. [emphasis added]

More than a few parents might be interested, and not just those who are using Waldorf ideas for homeschooling. Link: www.awsnabooks.org

aR ts: Music

an instrument “conceived out of silence”

The Lyre Association of North America just held a conference, “The Lyre & the Human Voice,” in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and it seems like a good moment to introduce this wonderful instrument, which is not the lyre of ancient Greece.

In the nineteen twenties, when many innovative ideas made an impact on the culture of the day...away from

8 • being human

An art and painting school that is rooted in the foundations of spiritual science. www.neuekunstschule.ch Join us to tread new paths for painting and Anthroposophy. neue kunstschule (newartschool) Art that makes a difference! mail@neuekunstschule.ch to speak with nks alumni in the US please call: 704 243 50 78 neuekunstschule, Birsstrasse 16, 4052 Basel, Switzerland. Tel +41 (0)61 311 41 40

Waldorf Education. Redefining success in education and in life. Strength Through Collaboration • Social Renewal • Learning for Life © 2012

of North America (AWSNA). Waldorf, AWSNA, WhyWaldorf Works, are registered marks of the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America. Like us on facebook! facebook.com/WaldorfEducation www.whywaldorfworks.org Receives the child in reverence, educates the child in love, sends the child forth in freedom YFinding our Self Supporting the Inner Life of the Teacher by Torin M. Finser Finding Your Self: Torin M. Finser WS na ublications Schools of North America Publications Office Torin M. Finser, hD, is currently chair of the ducation Department at niversity ngland, having previously led the Waldorf Teacher education program for eighteen years. h also serves eneral Secretary of the nthroposophical Society in america and represents the u a in international gatherings in Switzerland. has given presentations at conferences all over the world and recognized as Finding Your Self School as Journey translated into many languages, School Renewal being translated into Spanish, and Organizational Integrity will soon join School as Journey hinese. Many parents and teachers around the world have found their way to Waldorf education through his books. Torin lives in n hampshire with his wife, Karine, and their twelveyear-old son, Ionas. Their five older children are college-age and beyond. Karine is an art therapist, teacher, and creator of the cover illustration for Society demands so much of our teachers today. Schools are expected to deal with host of social needs, often without adequate funding and support. Many politicians think the solution is to raise standards through additional testing, common core curriculum, and increased scrutiny of teacher performance. The external pressures on teachers and schools are increasing each year, yet few ask the teachers, “What do you need?” Many studies have shown that the single most important factor in education is the teacher. In Waldorf schools, teachers are encouraged to grow professionally by cultivating inner resources. This book is intended to encourage teachers to take care of themselves, meditate, and become source of inspiration for our students so that together we can address the urgent needs of our time.

The Association of Waldorf Schools of North America (AWSNA) creates one voice for Waldorf Education across North America.

Association of Waldorf Schools

being human digest

the bustling crowd of mainstream progress, two men were in the lonely pursuit of creating an instrument gentle to the child’s ear, yet challenging to the discriminating musician. The lyre was conceived and created out of silence.

The year was 1926 ... the place, Dornach, Switzerland. The men through whom the lyre was realized were Edmund Pracht, a musician, and Lothar Gärtner, a sculptor, both still in their twenties and students of anthroposophy as taught by the late Rudolf Steiner. Soon the simple chromatic string instrument, which borrowed only its name from the Greek predecessor, came to the notice of teachers, curative educators and therapists, as well as to the ear of musicians and performers seeking a new manifestation of tone. In 1928, at a conference in London, four different models of the lyre were displayed.... Currently, there there is a wide range of lyres and related instruments, varying in size from a child’s “kinderharp” and cantele to the classical soprano and alto lyre for solo and ensemble playing. Largest of all is the Choroi (stand-up) harp.

The freeing of the tone from the resonance of the actual instrument is what all types of lyres have in common. With a new awareness, musicians use lyres for researching future elements of melody, harmony and rhythm. The gentle stroke of the string produces a somewhat modest note that grows at once in tonal intensity within the space of the room or hall where it is played. This acoustic property has been employed by Choroi for developing other instruments in the woodwind and percussion sector. A completely transformed ensemble sound is created when the new instruments play together. These words from Christof-Andreas Lindenberg are at the LANA website along with much more information on events, teachers, and instruments.

Link: www.lyreamerica.net

e nvi R on M ent – Biodyna M ic ag R icu Ltu R e food safety,

food Rights

David Gumpert, author of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Food Rights: The Escalating Battle Over Who Decides What We Eat, takes up this topic July 16 in Common Dreams. “Around the country, local farmers are selling meat, dairy products, and other dinner table staples directly to neighbors, who are increasingly flocking to the farms in search of wholesome food. This would seem to embody the USDA’s advisory, ‘Know your farmer, know your food,’ right? Not exactly.

“For the USDA and its sister food regulator, the FDA, there’s a problem: many of the farmers are distributing the food via private contracts like herd shares and leasing arrangements, which fall outside the regulatory system of state and local retail licenses and inspections that govern public food sales.

“In response, federal and state regulators are seeking legal sanctions against farmers in Maine, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and California, among others. These sanctions include injunctions, fines, and even prison sentences. Food sold by unlicensed and uninspected farmers is potentially dangerous say the regulators, since it can carry pathogens like salmonella, campylobacter, and E.coli O157:H7, leading to mild or even serious illness.

“Most recently, Wisconsin’s attorney general appointed a special prosecutor to file criminal misdemeanor charges against an Amish farmer for alleged failure to have retail and dairy licenses, and the proceedings turned into a high-profile jury trial in late May that highlighted the depth of conflict: following five days of intense proceedings, the 12-person jury acquitted the farmer, Vernon Hershberger, on all the licensing charges, while convicting him of violating a 2010 holding order on his food, which he had publicly admitted.

“Why are hard-working normally law-abiding farmers aligning with urban and suburban consumers to flout well-established food safety regulations and statutes? Why are parents, who want only the best for their children, seeking out food that regulators say could be dangerous? And, why are regulators and prosecutors feeling so threatened by this trend?

“Members of these private food groups often buy from local farmers because they want food from animals that are treated humanely, allowed to roam on pasture, and not treated with antibiotics. ‘I really want food that is full of nutrients and the animals to be happy and con-

summer issue 2013 • 9

being human digest

tent,’ says Jenny DeLoney, a Madison, WI, mother of three young children who buys from Hershberger.

“To these individuals, many of whom are parents, safety means not only food free of pathogens, but food free of pesticides, antibiotic residues, and excessive processing. It means food created the old-fashioned way— from animals allowed to eat grass instead of feed made from genetically modified (GMO) grains—and sold the old-fashioned way, privately by the farmer to the consumer, who is free to visit the farm and see the animals. Many of these consumers have viewed the secretly-made videos of downer cows being prodded into slaughterhouses and chickens so crammed into coops they can barely breathe.

“These consumers are clearly interpreting “safety” differently than the regulators. Some of these consumers are going further than claiming contract rights—they are pushing their towns and cities to legitimize private farmer-consumer arrangements. In Maine, residents of ten coastal towns have approved so-called “food sovereignty” ordinances that legalize unregulated food sales; towns in other states, including Massachusetts and Vermont, and as far away as Santa Cruz, CA, have passed similar ordinances.

“The new legal offensive isn’t going over well with regulators anywhere....” More online. [This aticle is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License.]

Link: www.commondreams.org/view/2013/07/16-2

Medicine

the human heart: cardiology in anthroposophic Medicine

The annual conference of the anthroposophic medical movement, 12-15 September at the Goetheanum, is dedicated to the heart and seeks to understand the essential nature of this central human organ in three steps.

Study of the way that the heart has been viewed in the western history of ideas leads, to begin with, to the key points of Rudolf Steiner’s teaching about the heart. How can we grasp the heart as the center of human fulfilment? The heart is not just in the middle physiologically, it is also the organ of conscience through which destiny is formed.

In the second step, a pathology of the heart is developed on the basis of anthroposophic medicine which highlights ideas on healing in the major disease groups of

sclerosis, heart rhythm disorders and myocardial disease. Prevention stands at the beginning of any treatment— which should really start in youth and education already, and which has created an anthroposophical cultural impulse in cardiology in the form of the heart schools.

These subjects will be discussed in a varied and differentiated way in subject-specific and interdisciplinary working groups. That is why this invitation is not just addressed to cardiologists but also general practitioners, pharmacists, physiotherapists, art therapists, eurythmy therapists, nursing staff as well as psychotherapists, curative education teachers, social therapists and everyone interested in anthroposophic medicine.

Link: www.herz-des-menschen.org/en/

Pe R sona L gR o W th

“Keep fighting, stop struggling”

Jonathan Levin of Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, recently sent being human a letter, honors thesis, and a sermon. He wrote, “My children, Miles and Nina Levin, matriculated from first grade through the 8th grade of the Oakland Steiner School, Rochester Hills, Michigan. The arc of Miles life was and the arc of Nina’s life is deeply influenced by their Waldorf education, as evidenced by the enclosed literature...”

The sermon is for Yom Kippur; Rabbi Aaron Staff observes that “traditional Judaism rejects entirely the notion of randomness. Everything, from the lottery to the most profound, well, acts of God, are part of the divine plan. But, to the human eye, the facts on the ground seem to suggest otherwise.”

Nina Levin’s BA honors thesis is “Finding Wholeness: An Eco-criticism.” From the Abstract: “How are distinct experiences of education microcosmic renditions of a grand intellectual landscape? How have writers—including myself—expressed sensations of wholeness through language? Had a reverence of Nature and literature long been the alembic of the mystery of the Universe? This paper addresses these very questions. ... Through an exploration of Waldorf educational systems, mathematical laws of Nature called ‘Fractals,’ Transcendentalism, Twentieth Century Latin American literature, and Sufi poetry, this thesis aims to deliver a sense of wholeness by dissecting these subjects into their curious and unexpectedly related constituent.”

And from Miles Levin’s book (with commentary by

10 • being human

being human digest

Jon Levin), Keep Fighting, Stop Struggling : “November 22, 2006. ... The U.S. population hit 300 million last month. Cases of rhabdomyosarcoma in America annually: 350. How wild is that?! (On top of that, my presentation is extremely rare.) In such a situation there is only one thing to do: buy lottery tickets. I bought my first one last weekend. I’ll probably win. Here’s another little statistic. 516 days down, 12 to go! We have pushed on with poisoning after poisoning and I am now hitting my physically tolerable maximum. When I’m not doing chemo...I feel normal, though sometimes a little weak. However, my insides are war-torn. My bone marrow is exhausted (though I can’t really feel that). My immune system is wiped out. I would hate to be a cancer cell right about now. My body will almost fully recover with time, although there are some long-lasting side effects.... I’m feeling a hearty dose of nausea as I type this.” And from April 17, 2007: “I try to hold in mind that all you can do is work with what you’re given, and I pretty much made the most of it. ... Who knows? I believe through cancer I was able to rise, coming respectably close to self-actualization. Maybe I never would have gotten my act together otherwise. Into adulthood, I might have been scattered, eternally five minutes late to life. Maybe this has put my good where it will do the most. I can only hope so.”

Copies of the thesis are available from Jon Levin at Yoni11@comcast.net; the book is available at www.Levinstory.com

s ociety - e cono M ics

“a Brief call for transformation”

“In a world in which we have commodified labor, land, and all natural resources, and now capital as well, why should we be surprised that democracy is also for sale? Citizens United has proven this point in the extreme. What has been less noticed or documented is a longstanding stealth campaign to commoditize human identity—the human ego is in many ways the last frontier

of commerce. Anyone who doubts this intention should be aware of the following clarion call from the Art Directors Club Annual No. 34 of 1955: ‘It is now the business of advertising to manufacture customers in the comfort of their own homes.’

“We cannot seek the antidote to this invasion in social isolation. Self-reflection is an important tool of selfknowledge, but self-knowledge is meaningless without the reciprocal knowledge reflected back to each of us from the world. In some ways we serve each other as awakeners and sanity checkers, and hold each other to accounts so to speak. Another way of looking at this would be that each of us needs to be free in determining a destiny path and vocation, and at the same time find meaningful work in serving others’ material needs. The world of rights and agreements mediates this intersection of the individual and material world, and the collective activity itself is what we call economics—or how we meet human material needs out of compassionate interdependence. I might venture to say that understanding and transforming how we work in the world economy, even in its most local or regional expression, is itself a threshold to restoring, preserving, or furthering the development of consciousness.

“The experience of this transformation acts as preventive counterpoint to what is a kind of virtual identity theft. Money, with all its attendant issues, is nothing more than the barometric instrument of the collective we call world economy. Understand money and the current condition of humanity, and our ability to know ourselves and care for each other is visible in it, for better or worse. Truth is, unless one hews to and hides behind a protected right of privilege, the picture demands profound transformation that centers on the intersection of money and spirit. This is work that no one other than each of us can do for ourselves, and even better to be done in community so that we can support others as they support us. If we do not rise to this challenge, we risk the human birthright and inner work of spiritual freedom and step instead onto a path of slow tyranny.”

John Bloom, Senior Director, Organizational Culture, at RSF Social Finance

summer issue 2013 • 11

Link: rsfsocialfinance.org/2013/05/call-for-transformation/

rudolf steiner library newsletter: reviews

Sacred Economics: Money, Gift and Society in the Age of Transition

By Charles Eisenstein; Evolver Editions, Berkeley, CA, 2011, 496 pgs.

Review by Christopher Schaefer, PhD

By Charles Eisenstein; Evolver Editions, Berkeley, CA, 2011, 496 pgs.

Review by Christopher Schaefer, PhD

This is a profound and moving book, full of insight and living examples. It is a book about money and our relationship to it, and how we can restore a sacred dimension to the world and to each other. As the author notes in his introduction, the book works at four levels: it shows what has gone wrong in our economic system; “it describes a more beautiful world based on a different kind of money and economy”; it moves to those collective actions and social changes required to shift our world from that of exploitation to sustainability and mutual service; and it ends with the individual changes of attitude and behavior that will contribute to a better world.

The argument is both simple and complex. Simple in the sense that Eisenstein, like Rudolf Steiner and Silvio Gesell, sees private land ownership and the interest-bearing nature of money as responsible for the gradual erosion of our shared heritage of the commons: of land, water, air, and natural abundance, and of a natural gift-economy that most ancient cultures experienced in word and deed. Complex because money and economic processes are so embedded in our everyday consciousness and so full of taken-for-granted assumptions that even to think differently about money today requires great effort. It seems as if our present economic and money system is surrounded by a magic spell that makes it difficult to even imagine alternatives to the exploitative nature of today’s market-driven global economy.

The great virtue of this book is that it deals with the fundamentals, as did Steiner in his World Economy. It goes deeper than, say, David Korten’s When

Corporations Rule the World or Agenda for a New Economy; or the work of Gar Alperowitz; or even that of William Greider’s The Soul of Capitalism. 1

By this I mean that each of these other studies accepts traditional notions of private land ownership rather than engaging concepts like leasing land and owning buildings and equipment. They don’t question the present approach to currency creation through central banks charging interest for the money created and pumped into the economy. Instead, they tend to argue about the balance between the private economy and government or public institutions, and the role of the latter two in taming or modifying the excesses of today’s market-economy. The three central chapters of Eisenstein’s analysis of present issues are called “The Trouble with Property,” “The Corpse of the Commons,” and “The Economics of Usury.” Each is compelling in its own right, and often poetic in imagery and tone. In the chapter on property Eisenstein states, “The urge to own grows as a natural response to an alienating ideology that severs felt connections and leaves us alone in the universe. When we exclude world from self, the tiny, lonely identity that remains has a voracious need to claim as much as possible of that lost beingness for its own sake. If all the world, all of life and earth is no longer me, I can at least compensate by making it mine. Other separate selves do the same, so we live in a world of competition and omnipresent anxiety.”2

In “The Corpse of the Commons” Eisenstein describes how we have commodified and privatized the four forms of capital that were at the heart of the “commons” we once shared as human beings: natural capital (the land and nature); social capital (community); cultural capital( books, songs, language, poetry); and spiritual capital (our consciousness and ability to create new realities). Each is now bought and sold so that the relentless logic of growth, of increasing wealth and GNP can be met.3

In the chapter on the economics of usury the author gets to the heart of his case: “the problem starts

1 David Korten, When Corporations Rule the World, 1995, & Agenda for a New Economy, 2009, both Berrett Koehler, San Francisco; Gar Alperowitz, America Beyond Capitalism: Reclaiming Our Wealth, Our Liberty, and Our Democracy, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 2005; William Greider, The Soul of Capitalism: Opening Paths to a Moral Economy, Simon and Schuster, NY, 2003

2 Eisenstein, Sacred Economics, 50.

3 Ibid., 69–90.

12 • being human

with interest. Because interest-bearing debt accompanies all new money, at any given time, the amount of debt exceeds the amount of money in existence. The insufficiency of money drives us into competition with each other and consigns us to a constant, built-in state of scarcity. It is like a game of musical chairs, with never enough room for anyone to be secure. Debt-pressure is endemic to the system.”4 In an interest-based money system, income inequalities grow, especially when the commons have been privatized, and the likelihood of financial and economic crises grows as there is not enough demand to justify ever-expanding economic growth. The global financial crisis of 2007–9 and the decade-long recession in Japan are cases in point. This insight is also central to Robert Reich and others who have argued that there will be no economic recovery absent a concerted push to equalize wealth.5 No demand, no growth: no economic recovery and ongoing crises. While China and India as well as parts of Africa may still offer opportunities for economic expansion, developed economies are maxed out, with the result that wealthy corporations and individuals will cannibalize the economy to fulfill their expectations of financial return. Eisenstein summarizes by stating, “I think we will first experience persistent deflation, stagnation, and wealth polarization followed by social unrest, hyper-inflation, or currency collapse. At that point the alternatives we are exploring will come into their own….”.6 I agree.

The alternatives that Eisenstein—and a century ago, Steiner and Gesell—proposes are an economic system where money is publically created and carries a negative interest charge: spend it or it loses value; and a society that provides for the local and regional ownership of the commons—of land, currency, the air, mineral rights, water, cultural goods, and spiritual capital. It will be a zero-growth economy that balances wealth and fosters a simpler local and regional sense of community. It will replace the often insane race-to-the-bottom logic of the global economy with local economic and social activity. It will follow the pattern of nature, the law of return, and charge for all the environmental and social damages

4 Ibid. 102.

5 See Robert Reich, After-Shock: The Next Economy and America’s Future, Alfred Knopf, New York, 2010, 32–8.

6 Eisenstein, Sacred Economics,136.

caused by present production techniques, and it will promote simpler economic and social systems based on a sense of gratitude, of gift in return for what has been given. Eisenstein calls this the “Economics of Reunion” and points to many present initiatives that bear the hallmarks of these new economic and social relationships, from the land-trust movement to local and complementary currencies; from ethical investment and carbon and environmental taxes to the gift and mutual-exchange economy. Eisenstein proposes seven major steps: creating negative-interest currency; eliminating rents and interest; compensating for the depletion of the commons; internalizing all social and environmental costs; pushing for economic and monetary localization; realizing the social dividend and spreading it through a form of basic income; promoting de-growth and fostering a gift and people-topeople(P2P) economy.7

Part 3, “Living the New Economy,” describes what we as individuals can do to contribute to a more local, sustainable, and gift-based economy. While quite idealistic in tenor, these closing chapters do challenge us to rethink and to transform our relationship to money, work, possessions, and community, and offer us opportunities for growth and for sharing our gifts with others.

I wholeheartedly recommend Sacred Economics for its penetrating analysis and its hopeful image of our economic and social future. Savor it, and then add the following works to your reading list: Martin Large’s Commonwealth for a detailed picture of the contribution threefolding is making to society’s future; Christopher Houghton Budd’s Finance at the Threshold for its penetrating analysis of the international financial system and the problem of excess capital; Gary Lamb’s Associative Economics, because it makes visible the central role that associations among consumers, producers, and traders must play in a new economy; and Steiner’s World Economy, because, while difficult, it contains the most far-reaching discussion of labor, capital, land, and price that I know of.8 Together, these five books provide a basis for a

7 Ibid., 331–346.

8 Martin Large, Commonwealth: For a Free, Equal, Mutual and Sustainable Society, Hawthorn Press, Stroud, UK, 2010; Christopher Houghton Budd, Finance at the Threshold: Rethinking the Real and Financial Economics, Gower, London, 2011; Gary Lamb, Associative Economics: Spiritual Activity for the Common Good, ASWNA, Ghent, NY, 2011; Rudolf Steiner, World Economy: The

summer issue 2013 • 13

newsletter:

rudolf steiner library

reviews

new economics curriculum and a far reaching and possible new society.

Rudolf Steiner and the Atom

By Keith Francis. Adonis Press, Hillsdale, New York, 2012, 267 pgs.

Review by Frederick J. Dennehy

My disappointment after finishing Rudolf Steiner and the Atom was this: that I had not had the experience of having Keith Francis as a science teacher in school. Readers who, like me, have only a peripheral scientific background will be grateful for Mr. Francis’s ability to anticipate a reader’s questions and weave his responses into the book. The writing is so clear that even a reader without interest in anthroposophy will be excited by the history of the atom presented here, from the high days of ancient Greece; through the pioneer work of the 19th century leading to the development of the familiar Rutherford atomic model; to the imaginative daring of scientists such as Bohr, Einstein, Heisenberg, Born, Jordan, Dirac, and Schrödinger, who shaped and colored the quantum era. 9

What was Rudolf Steiner’s opinion of atomic theory? And what would that opinion have likely been following the anni mirabiles 1925–1930, immediately following his death? Although Mr. Francis pursues these questions throughout the book, he does not come to final judgment, because to produce a definitive answer would be to satisfy a need other than that for the truth. But the hunt itself is altogether worthwhile.

In his books and public lectures, Rudolf Steiner was emphatic in his opposition to atomic theories. He said that the atom was a mental construct, and accordingly

Formation of a Science of World Economics, Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1949. 9 I found myself wishing that Mr. Francis had also dealt with David Bohm’s approach. But then, as he observes, this is not a “book about everything.”

extended beyond the domain of the perceived world. For Steiner, as for Goethe, scientific theory must be limited to the perceptible, and must seek its connections within the perceptible.

But in the lectures he gave for members of the Theosophical Society, and later, the Anthroposophical Society, Steiner referred to atoms as physical realities, and cautioned his listeners about the demonic (ahrimanic) consequences of endowing the atom with the characteristics of “coagulated electricity”—the “same substance of which thought itself is composed.” Someday, said Steiner, “a man standing here, let us say, will be able by pressing a button concealed in his pocket, to explode some object at a great distance—say in Hamburg!… What I have just indicated will be within man’s power when the occult truth that thought and atom consist of the same substance is put into practical application.”10

This raises two distinct questions. First, how does one reconcile Steiner’s public and private pronouncements? Second, what would Steiner say now about atomic theory, which today is less a “theory” than it is the standard vocabulary of science, accepted by virtually every physicist in the world?

Mr. Francis approaches the apparent contradiction between Steiner’s public position that the atom is a mere mental construct and his private reference to atoms as constituents of the physical world by reminding us that Steiner himself said more than once that anthroposophy was “difficult” and also “strange.”

It may be helpful to understand it this way. The image of the electronic atom that Bohr worked with is in fact an intellectual artifact that does not correspond to anything in the physical world. Yet it may be “real” because the worlds of soul and spirit have reality just as does the physical world. Steiner said repeatedly that a wrong thought can do real damage. Thus, while the physicist’s mental representation of the atom in Steiner’s time may never have existed in the physical world, it may nonetheless be real if it has penetrated the general thought environment and become a vehicle for conceptions “for the future of a humanity bound to the physical world and unconscious of the spirit.” While unfortunately Steiner did not address the apparent contradiction for us, his latterday readers, he surely was not engaging in “double think.”

We should not treat categorically Steiner’s 1904 state-

Electricity.” Berlin, December 23, 1904.

14 • being human

steiner library newsletter: reviews

rudolf

10 “The Work of Secret Societies in the World: The Atom as Coagulated

Dr. Christopher Schaefer is a lecturer, writer, researcher, and organizational development consultant, and co-director of the Center for Social Research at Hawthorne Valley (thecenterforsocialresearch.org)

ment that “thought is composed of electricity.” Haven’t many of our thoughts been degraded by beings whose function it is to take control of them, and who use the very energy of divine intelligence descending into human intelligence to do so? But we know that in the Michael age, “hearts begin to have thoughts.” We may be very confident that “heart thinking” is not an electrical composition.

Mr. Francis’s attempt to reconcile Steiner’s public and private expressions about the atom is not designed to produce satisfaction or relief. It succeeds powerfully, however, in calling attention to what we do not fully understand. And what we do not understand is a gate through which we can go further spiritually—what Georg Kühlewind called a “sacred gate.”

The second question is even more challenging: How would Steiner have viewed the quantum revolution that began in the year of his death? During Steiner’s lifetime, it had become “close to heretical” to question the notion that the atom, in something very close to the Rutherford/ Bohr model, existed independently. Atomic science was believed to provide an objective account of the world governed by deterministic laws. But following the quantum revolution, the border between subject and object had been blurred, determinism had fled before probability, and the Copenhagen Interpretation, initiated by Bohr, eventually won the field. According to his most brilliant pupil, Werner Heisenberg, Bohr’s own insights did not come from mathematical analysis or discursive reasoning, but from an observation of actual phenomena so open and unprejudiced that it was possible for him to sense relationships intuitively. Mr. Francis presents Bohr as a scientist with enormous spiritual patience, someone capable of remaining in the question and struggling to define it rather than answering it in a linear fashion. For Bohr, “the question and the answer grow together through the interplay of inner and outer.” His methodology was to grasp the outer world in a familiar way and then to penetrate further after learning inwardly to construct the purely mathematical aspect. His third step, in Steiner’s terms, would be “the entirely inner experience, like the mathematical experience but with the character of spiritual reality.”

So far, Bohr’s methodology might suggest a modern version of Goethean science. But the comparison can be taken only so far, because the experimental methodologies employed by the leaders of the quantum revolution were made by intrusions into the natural world clearly

antithetical to the Goethean spirit.

It cannot be sufficiently emphasized that for Bohr and Heisenberg, the scientific project was not to discover a reality behind the phenomenal world or to construct mental images of particles and waves to serve as substitute realities. The giants of the quantum era stand fast at the threshold, preventing the monster of all-embracing reductionism from sweeping the field. As Mr. Francis puts it, “modern psychology depends on physiology, physiology depends on biology, biology depends on chemistry, and chemistry depends on physics; and, deep down, the wonderful thing is that nobody understands physics.”

Perhaps Niels Bohr was not, as Mr. Francis poses the question, a Goethean physicist. Certainly, quantum physics is in no way a proto-anthroposophical approach to reality. The atomic theory that came to flourish immediately after Rudolf Steiner’s death was initiated by scientists who, in the main, gave everything—often to the point of mental breakdown—for what they perceived to be the truth. The result of their efforts stands fast against the overwhelming lust in our day for determinism and reductionism. Perhaps one day, in ways that are not now apparent, it will lead to a science of the spirit.

Biomental Child Development: Perspectives on Psychology and Parenting

By Frank John Ninivaggi, MD; Rowman & Littlefield, 2013, 512 pgs. Review by K. David Schultz, PhD, ABPP, FAACP

Dr. Frank J. Ninivaggi, assistant clinical professor of child psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine Child Study Center and medical director of the Devereaux Glenholme School in Washington, CT, provides a thorough review of human physical and psychological development from infancy through childhood and adolescence to adulthood, which he refers to as “biomental child development.” His approach is consistent with the perspective evident in von Bertalanffy, Schaefer, and Buber.

Utilizing an anthroposopher’s way of thinking without employing traditional anthroposophical language, Dr. Ninivaggi has crafted a comprehensive, professional survey of contemporary scientific developmental research expressed in modern, human-centered concepts. Remicontinued on page 62

summer issue 2013 • 15

steiner library newsletter: reviews

rudolf

initiative!

In Th

IS SecTIOn:

Whenever the idea of an initiative has come up, the House of Peace is likely to be mentioned. We’re delighted finally to share the story of Carrie and John Schuchardt. Some months ago a powerful but rather mysterious poem came in from Colorado teacher Laurie Clark. “Perhaps you could put this in context,” we said, and the resulting story, told with her longtime friend Joan Treadaway, leads us into a very difficult and beautiful place. A bonus is the brief reminder of the Grimms’ story “The Donkey Prince.”

Marke Levene is person of large initiatives like mystery drama productions and symphonic eurythmy tours. He and a group of gifted colleagues are taking on an even larger challenge now. They met in Greece this spring, at Delphi, to shape their plans.

Creating a House for Peace

by Lori Barian

Number One High Street, Ipswich, Massachusetts, manifests the reality of its name—The House of Peace—in manifold healing relationships. By bringing together refugees, individuals with developmental disabilities, veterans, social activists, anthroposophists and spiritual seekers of many faiths and beliefs in one home, founders Carrie and John Schuchardt create the opportunity for knowing to overcome fear and to become love, daily.

The House of Peace “is a therapeutic community serving victims of war in companionship with adults with disabilities, and offering education for peace and moral awakening.” Since it opened its doors in 1990, 23 years ago, hundreds of survivors of war have found refuge there for days, weeks, months and some for years. For all, there has been continuing presence and support for the painful challenges of recovering from violence and unspeakable loss.

Two grand white pillars flank the House of Peace entranceway, symbols, say John and Carrie, of the essential supporting pillars of the work: Trust and Gratitude. Others, including neighbors, the Anthroposophical Society of Cape Ann, the Christian Community, Waldorf school communities, Veterans for Peace, the North Shore Coalition for Peace and Justice, and monks of the Nipponzan Myohoji Japanese Buddhist order dedicated to nuclear abolition, may think of John and Carrie as the real pillars of this house that has a place for them all.

Truly, trust and gratitude have contributed much to this initiative’s ability to come into being and to serve so many so well. And just as truly, a rather magical coming together of Carrie and John, Camphill, and movements for peace and justice led to this unique healing community.

Carrie, who grew up outside of Boston, was greatly influenced by having an older sister with special needs. Then, in her teenage years, she found inspiration in the movement for social justice. After undergraduate and graduate degrees preparing her to work with those with disabilities, she and her husband at that time, George Riley, joined Camphill Glencraig in County Down, Northern Ireland in 1971-72, during the height of The Troubles. “I was living in a war zone,” Carrie said. “I experienced what it was like to be among people who live in fear. I heard bombs, witnessed carnage, saw the profound imprint of the violence on human beings—how fear takes hold.” In 1975, they joined Camphill Kimberton Hills in Pennsylvania with their little son, Colum. They had two more children: Kieran, and later a daughter, Ethna.

16 • being human

John grew up in rural Illinois, graduated from a Quaker college and University of Chicago Law School, and then, while on active duty in the U.S. Marine Corps, resigned his commission in 1965 when the U.S. began the unprecedented bombing and destruction of the defenseless agricultural societies of North and South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. As an attorney, John recognized that this aggression was a violation of the Nuremburg Principles. John then served as Director of Orientation for The Experiment and its School for International Training, and later practiced law as the first public defender of Windham County, Vermont. Continuing a spiritual quest, John joined the Bruderhof community in Rifton, New York, in 1975. This confirmed his belief that he must take personal responsibility in confronting the genocidal technologies of the escalating nuclear arms race. In 1976 he joined Jonah House, a community committed to nonviolent resistance to illegal weapons and wars of aggression. On September 9, 1980, he and five men and two women courageously entered General Electric Plant #9 in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania to “beat swords into plowshares and spears into pruning hooks.” They poured their own blood on blueprints and files and used hammers to render harmless two Mark 12A nuclear warhead components, which were thus never to be used on Minuteman ICBM missiles. All 8 were imprisoned for long terms, including internationally known and revered Catholic priests, Revs. Philip and Daniel Berrigan. “We were focused on the reality of impending nuclear catastrophe,” John said. “We went in to disarm these horrendous technologies to awaken conscience.”

Carrie had met and been inspired by Daniel Berrigan, so when the Plowshares, as they were known, appeared in court, she was there as a citizen supporting the deed. She met John and John’s sister Ada Lorette for the first time then. During the course of those next 10 years, John and Ada visited Camphill occasionally. It was through Camphill that John first met and was deeply moved by

anthroposophy and Waldorf education.

The year 1980 was pivotal. “I became aware of a real call to welcome victims of war into my own family,” Carrie said. “The deeds and mantle of motherhood needed to stretch out over the globe.” Two Vietnamese boys, “boat refugees”, arrived in June 1980 and were foster sons through high school at Kimberton Waldorf School. Two brothers and a sister of one of them joined their family in 1986. She saw magic happen as adults in need of special care welcomed and cared for spiritually wounded and traumatized refugees. It was through these intimate experiences of motherhood, lived in a socially therapeutic community, that Carrie became convinced that “it is war that is the ultimate handicapping condition and that people, so often labeled handicapped, hold the key to healing.”

This led to the vision in 1989 to offer shelter to refugees and people with special needs: the vision for the House of Peace.

Carrie went in search of the right place for this to happen and found the historical Rogers Manse for sale in Ipswich, Massachusetts. After her first visit to this house, she called one of her friends and mentors at Kimberton Hills, Helen Zipperlen, who with her husband Hubert was one of the founders of Camphill Kimberton. She described to Helen this perfect site: The home was built in 1727 by the minister of the First Church of Ipswich for people fleeing religious persecution. Transcendentalists including Thoreau and Hawthorne had spent time there. It is

summer issue 2013 • 17

located an hour north of Boston, near the coast and the healing forces of the ocean, with 10 bedrooms, 5 baths, 4 acres of land, gardens, nature, a convenient walk to downtown, a room for a chapel, and a hall for festivals and lectures. “It was totally clear and totally impossible,” Helen said, because there was no money to buy it. Helen helped galvanize support from friends of the Camphill community. “I sent letters to everyone I could think of: ‘Send me $5; send anything you would like.’” And support came, Helen said. “Everyone who knew her knew that if Carrie was doing it, it was going to be unconventional, possibly dangerous, but it was certainly right and needed doing.”

On Veterans Day, November 11, 1990, John and Carrie joined thousands in the streets of Boston in an outcry against the impending bombing of Iraq. The next morning they were married in the House of Peace chapel. Once settled in, with two companions from Camphill, her two foster sons Hue and Xia, and Colum, Kieran, and Ethna, other human and financial support came.

The first eight years, Carrie and John worked with local agencies following UNHCR (the United Nations Refugee Agency) protocol to provide a temporary home to unaccompanied refugee minors, mostly boys, some of whom had seen parents assassinated. They came from Haiti, El Salvador, Vietnam, Cuba, Ethiopia and Eritrea. Later the House of Peace helped families from all factions of former Yugoslavia resettle in America, and then families from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Somalia, Sudan and the Congo.

The most recent phase has been working in partnership with the Iraqi Children’s Project and Shriners Hospital in Boston, housing children and their parents while the children undergo surgery for burns and other severe injuries that have occurred as “collateral damage” from the U.S. invasion and pacification operation.

At the heart of this work with refugees is “the deep

companionship of friends with disabilities,” Carrie said. “We see that people in need of special care have the gift and responsibility to give special care.” She shared the story of Joseph, a beloved member of the household who recently passed away. Joseph was blind, mute, and brain injured at birth, yet refugees and guests gravitated to his warm heart forces; free of all antipathies, Joseph communicated trust and security to those most violated by violence. “The so-called handicapped are the hearth that the refugees go to first.”

This work housing and caring for refugees and living in companionship with people with developmental disabilities is embedded in a full anthroposophical community life and public social activism. From the beginning, Carrie and John have held an every-other-week study group at the Cape Ann Waldorf School working with Rudolf Steiner’s “basic books” and significant courses and lectures. In collaboration with the Anthroposophical Society of Cape Ann and the Cape Ann Waldorf School, many vibrant seasonal festivals are held and celebrated at the House of Peace and a summer lecture series is offered. Retreats for Christian Community confirmands, priests, and guest speakers have been part of the integration with the wider communities.

Joyce Reilly, who met Carrie in 1980 at a conference, has been on the House of Peace board for 20 years. Joyce described Carrie and John’s approach to life as a graceful balance of idealism and practicality, of seriousness and humor, of depth of study and intimacy of human relationships. “This balance keeps them so effective with people and accepting of themselves,” she said. “They are aware of and embracing of human frailty and seek creative ways to healing.

“John can talk to senators, make headlines, and build a chicken house in the driveway,” she said. “Carrie has an amazing ability to speak extemporaneously and an extraordinary sense of humor. She sees the beauty and holiness of things as well as the often inevitable humor. She’s down to earth.”

Dave Mansur, who serves as treasurer of the House of Peace Board and as a leader in the Anthroposophical Society of Cape Ann, remarked about anthro-

18 • being human initiative!

posophy being at the core of John and Carrie’s initiative. “We like anthroposophy because it is practical. This is a shining example of that practicality. For it to work, one needs that fundamental understanding of the human being as a noble individual. All this service becomes almost ordinary in that light. ‘Of course that’s how you would treat another human being !’”

In September of 2001, for example, Carrie and John had been negotiating for the children of a refugee family from Afghanistan, living at the House of Peace, to attend the Cape Ann Waldorf School, explained Dave, who was serving on the school’s board at the time. Then September 11 happened. “There was a lot of fear, “Dave said. “Carrie and John stood by their principles, saying ‘they have been victims of violence and cruelty and we can help.’ The children were enrolled in the school and their family has been contributing positively to the community ever since. It turned the experience of 9/11 into something with a thread of hope. This is what they do.”

The Cape Ann Waldorf School graciously welcomes children of refugee families as students from time to time, for the most part with full scholarship, said Jenny Helmick, who has had many roles at the school over the years. “It has been a wonderfully enriching experience. For the children to hear stories and learn to interact with each other is remarkable.”

Carrie and John’s willingness to fully immerse themselves in the physical demands and the sorrows and joys of the people they serve arises in part from a serious sense of urgency about the times we live in.

“Rudolf Steiner understood the catastrophe of war and he was passionately, urgently seeking to awaken human capacities to avoid the blind materialistic path heading to destruction,” said John. “Yet, this fervent plea Steiner is making to humanity has almost faded in people’s consciousness. Things have gotten worse and worse. Nuclear weapons are on alert every moment in seven nations, in all the most distrustful, conflicted regions.”

John also spoke of the karma of untruthfulness and the critical need for human beings to pursue truth in our time. “When assaulted by untruth from persons in author-

ity, our human capacity to think becomes dulled,” he warned. “In reality, we can see all around where Steiner’s contingent prophecy has become true: people have actually lost their capacity to think. Notice how many times you hear people say regarding uncomfortable untruths, ‘I don’t want to think about that.’ Rudolf Steiner saw outward events as symptoms. We need to understand the spiritual forces of untruthfulness and of karma holding us paralyzed and seemingly incapable of a full human response to the forces destructively at work!”

Untruth also divides us while truth unites us. Carrie shared that on Good Friday of this year, as the House of Peace presented “The Angel that Troubled the Waters” by Thornton Wilder, a play which refers to a scene in the St. John’s Gospel, Chapter 5, verses 12-14. In the play, a man with a palsied hand and a doctor with an inner wound both come to the well for healing. The angel troubles the water and the man with the ill hand is healed. The doctor asks for healing, but the angel says to him “Without your wound, where would your power be?”

Carrie said that there was a Muslim man from Iraq with them that night who saw the play. “There was truth in that,” he said to Carrie.

“That binds us together—the universality of truth,” she said. “It overcomes all things that divide us… Oneness does emerge.”

To help the next generation learn more about the needs and tasks of our time, the House of Peace also welcomes and offers experiential learning opportunities to young people involved in youth groups, fulfilling practicum requirements, working on master’s degrees, etc. “These are catastrophic times,” Carrie said. “Steiner has made very clear that we’re meant to be preparing the next epoch. We need to translate fear into hope.”

The Boston Marathon bombings created such an opportunity. At their regular study group gathering, they chose, said Carrie, to revisit the verse that has these words: “We must tear up by the roots—fear. It is essential to do what is right in the moment and leave the rest to the spiritual world.”

She went on to say, “We really work with people to understand that within each of us there slumber capaci-

summer issue 2013 • 19

ties to really make peace, and be at peace, and to create a culture of peace. We work at weaning people off of the media hype that fans the flames of fearfulness. We have people work to understand what their inner and outer environment really is. We speak about it in depth. Almost everyone who needs the House of Peace has posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We’ll never remove the wounds of terrifying events or deaths or shrapnel, but we can become stronger to bear that pain. When the circle is formed and people can share their pain and suffering with each other, they gain a sense of how truth and goodness are bigger than all that.”

Dave Mansur shared this story illustrating Carrie’s words. On the day after the Boston Marathon bombings, a little boy, who had lived for many months with his father at the House of Peace while being treated at a hospital for terrible burns all over his face and body, called the House of Peace from Iraq to ask with his little voice, “Is Carrie all right?” And then he asked about each one in the house by name to be sure that they, too, were all right.

As Karl Pulkkinen, vice president of the House of Peace Board, said of the work: “We can help undo some of the damage done in this world and literally make the world a better place.” Karl wanted readers to know that financial donations and volunteer and practical support are always appreciated. Contact John or Carrie for more information and to get on the newsletter mailing list: 978-356-9395 or thehouseofpeace@yahoo.com. Ask for past newsletters, too. They are filled with stories and photos of beautiful lives touched and healed, wise words from the founders, inspirational quotes from others, and more.

Lori Barian is Director of Administration &

Enrichment

happens

an all-wise cosmic guidance. Our part is to do, in each moment as it comes, what is right— and to leave the rest to the future. That is indeed the lesson we have to learn in this time: to base our life on simple trust, without any security of existence, to have trust in the ever-present help of the spiritual world. That is the only way for us, if our courage is not to fail...

20 • being human initiative!

Adult

at the Great Lakes Waldorf Institute. She has BS and MA degrees in English, and a certificate in Waldorf education. A member of the Emmaus Branch, she served on the Anthroposophical Society in America’s General Council representing the Central Region.

We must tear up by the roots fear and shrinking in the face of what the future threatens to bring to man. The whole feeling we have about the future must be pervaded with calm and confidence.

Absolute equanimity in the face of whatever the future may bring—that is what man has to acquire, knowing as he does that everything that happens,

under

—Rudolf Steiner

To Enkindle the Soul of Another

by Laurie Clark & Joan Treadaway

…and something ignited my soul, Fever or unremembered wings. And I went my own way deciphering that burning fire, and suddenly I saw the heavens unfastened and open.

—Pablo Neruda

Five-year-old Jenna discreetly throws her crackers under the table at snack time. She has been hospitalized before with an eating disorder. David, who is six years old, wears thick glasses, has a speech impediment, and falls often as his balance system is compromised. Jonah was adopted by his uncle after it was discovered that there was abuse by his drug-addicted mother. Ten-year-old Keith whose subliminal animosity permeates his daily mood and underlies his expression of disdain and sarcastic responses, refuses to cooperate with most requests. And eight-year-old Evelyn, a silent introverted child, shoulders hunched, her body folding in upon itself, speaks in a gesture of longed-for protection, for invisibility, of “please hide me.”

These children bring questions, riddles from the spiritual world, expecting to meet a resonance when they come, and a welcoming gesture that leads them into a relationship of trust in finding their answers. Everywhere, simulated images on screens appear, giving the child a counterfeit shadowed picture of life. These images are a distorted reflection of the archetype the child is seeking. Standing in desperation before this “shattered mirror,” the children’s longing for that welcome often becomes a veil of aberrant behavior, masking a noble destiny. Often, these children bring an extraordinary strength of will and carry their pre-birth instructions and resolves they have made with utmost integrity. Yet the clarion call for each child today sometimes comes to us as obscured by fear, defiance, a fury of demands; and even cloaked in the “silent tears” of deepest sorrow springing from a ravaged soul. We may never hear their stories, but we are called to meet their essential Being with active compassion—called to respond not with “this poor child” but with “I feel him, and I actively join in with him.”

There is an increasing number of children today who have these difficulties and are struggling to penetrate fully into their body; their “I” being hovering instead of integrating through the typical developmental stages into the self. Often this presents itself in the child as a disturbance in the lower senses. Instability in the senses of touch, balance, and self-movement shakes the child’s very foundations and may result in a disorder in the sense of life, the sense of well-being. Confidence and assurance in existence are traumatized when searching—for the way into one’s body and in the world—does not “make sense.”

There remain other unique and unusual children who bring various challenges that require the teacher to navigate through uncharted regions of the soul, encounters with which she has previously had no experience. The teacher is in constant search of an inner soul map so that she can guide these children who are in her care.

Laurie Clark, a long time Waldorf educator, describes one of these remarkable children who was a six-year-old boy in her kindergarten class. He was adopted from a Russian orphanage at the age of two. His experience in the orphanage was horrifying and disorienting. His devoted adoptive parents did everything possible for him including choosing to live in a lovely home in the mountains so that he could experience nature as a healing element. In the classroom he was disruptive, often making loud noises and uncontrolled movements, and had a look of scorn on his countenance. It appeared as though he was fighting a battle within himself, struggling to find his way into his body, to find some grounding. What seemed to the onlooker as misbehavior, however, was the honorable struggle that he valiantly fought and took on as his challenge in this incarnation.

This child could not bear to be the one who was chosen in a game, to be in the center of the circle, or any other circumstance that would make him feel as though he were being exposed. At story time, after telling a fairy tale several times, the children love to dramatize the story or “play” it as the story is told. One day, much to every-

summer issue 2013 • 21

What seemed misbehavior was the honorable struggle he valiantly fought...

one’s astonishment, when the question “Who wants to be the donkey in the story?” was asked, this boy who never volunteered for a part in a play, shyly raised his hand. Laurie held her breath and handed him the donkey ears for the play.

This Grimm fairytale “The Donkey” is about a king and queen who have everything they want except for a child. When God grants them their wish and a child is born to them, he is not a human child, but a donkey. The queen wants to “throw him into the river and let the fishes devour him,” but the king insists that he will grow up and wear the kingly crown. The donkey loves music and learns to play the lute. One day, out walking, he sees his donkey form in the mirrored water of a well, and decides to leave his kingdom. He walks uphill and down and enters another kingdom where he sits at the gate and plays his lute until the gatekeeper opens the entrance and takes him in to the king. The king grows fond of the donkey and after some time, marries him to his beautiful daughter. When the donkey is alone with the princess, he takes off his donkey skin and reveals himself as a prince each night. Each morning, before he leaves the chamber, he puts his donkey skin back on. When a servant divulges this secret to the king, the king himself goes at night into the chamber of the princess and sees the donkey skin lying on the floor and the handsome youth asleep beside his daughter. He quietly takes the donkey skin that is lying on the ground and has it burnt to ashes. When the prince awakens and cannot find his donkey skin, he becomes full of anxiety and decides that he must escape. The king meets him at the door, however, and begs him to stay and to show himself as he truly is. He gives the prince half his kingdom and offers the other half after his death. The prince inherits his own father’s kingdom as well, “and lives in all magnificence.”

This boy recognized himself in the archetypal situations which “The Donkey” presented. He had such an intense desire to portray this inner reality that truly belonged to him, that he overcame his fear of exposing himself in order to have this living experience. The teacher, standing beside the child as witness to his experience, had an inner resounding of the significance this had for this boy. Through this recognition, a deep unspoken communion occurred in the relationship between the teacher and child. An inner condition of feeling the other within oneself transpired, a kind of “inside out” understanding in the soul of the teacher where the soul condition of the child became her own experience. A transformation in