edited by MANLIO MICHIELETTO

edited by MANLIO MICHIELETTO

edited by

MANLIO MICHIELETTO

Towards the next heritage. Museum projects in Old Cairo

THE EPISTEMIC SPACE

Towards the next heritage. Museum projects in Old Cairo

ISBN 979-12-5953-176-6 (printed version)

ISBN 979-12-5953-182-7 (digital version)

edited by Manlio Michieletto

editorial board

Yara Galal, Martina AbuAlam, Nadeen Amged

related laboratories and research programmes

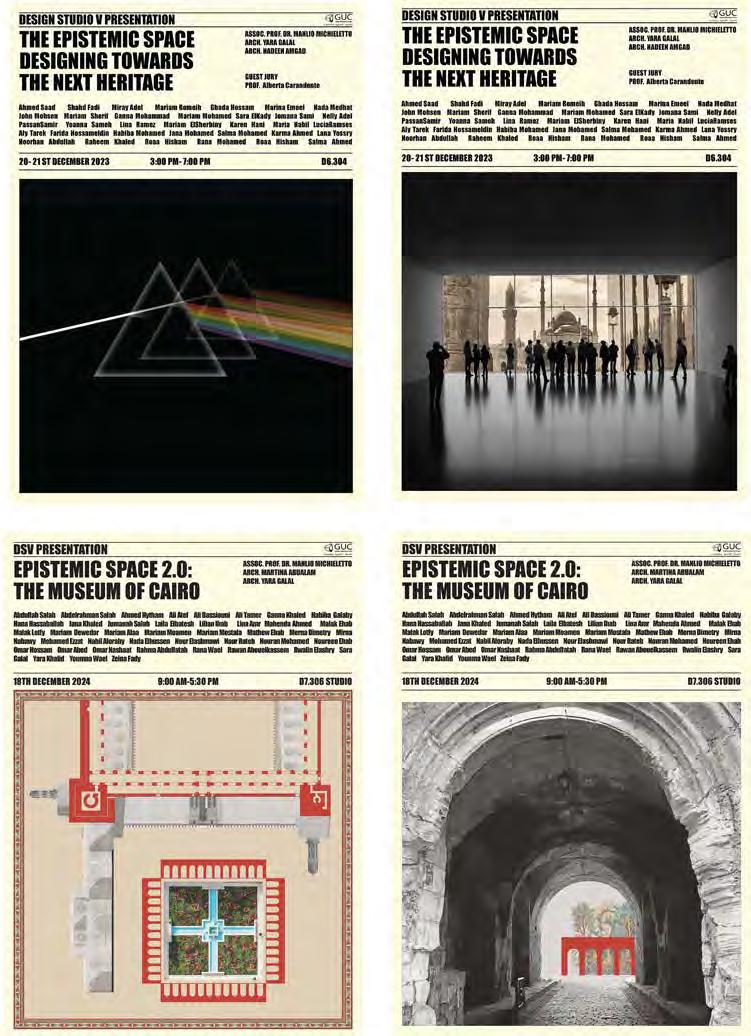

The book showcases the outcomes of two design studios, ARCH703, conducted in the winter semesters of 2023 and 2024 at the German University in Cairo, GUC.

translation by Manlio Michieletto

publisher Anteferma Edizioni Srl via Asolo 12, Conegliano, TV edizioni@anteferma.it

First Edition: September 2025

Copyright

This work is distributed under Creative Commons License

Attribution - Non-commercial - Share-alike 4.0 International

Yara Galal

Lilian Ehab, Salma Moussa and Mirna Nabawy

Manlio Michieletto

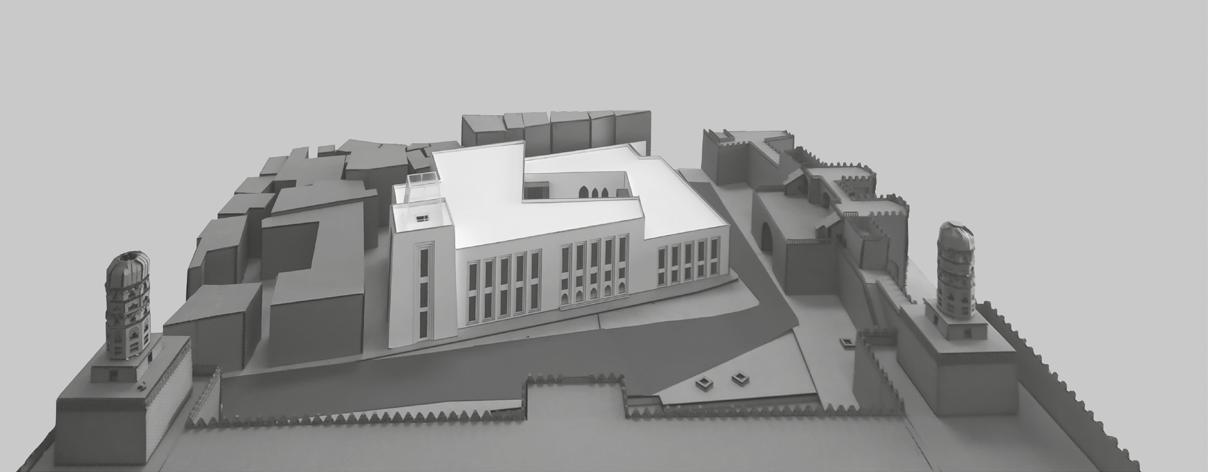

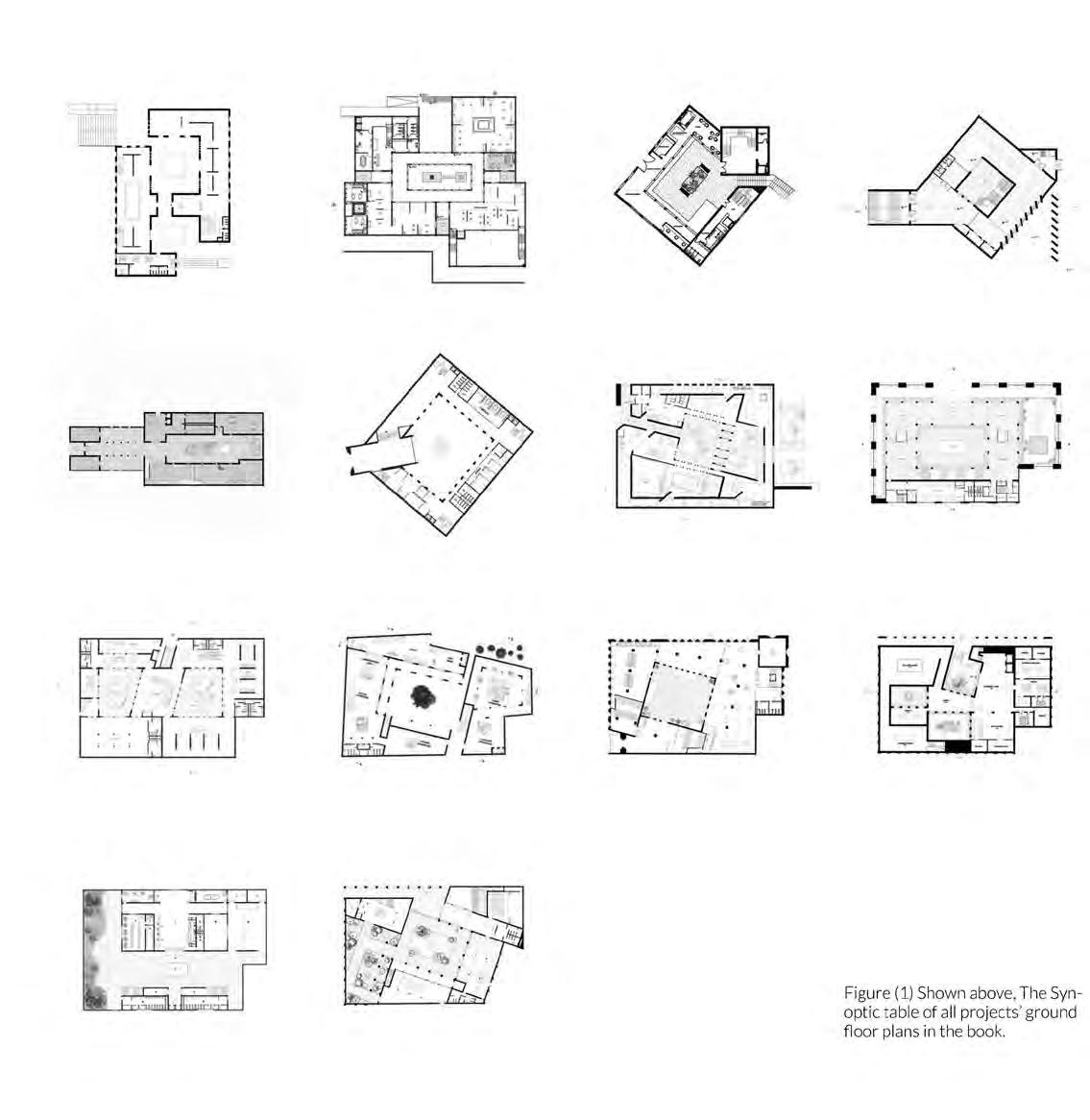

This book presents the outcomes of two consecutive academic years of design studios conducted under the direction of Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto, supported by teaching assistants Yara Galal, Nadeen Amged, and Martina Yacoub. Special acknowledgment is extended to Lilian Ihab, Mirna Nabawy, and Salma Moussa for their invaluable contributions in curating, selecting, and editing the students’ projects. The aim is to analyze the students’ architectural proposals from both compositional and operational perspectives, focusing on their design approaches for a new museum dedicated to the city of Cairo. The 2023/24 and 2024/25 design studios, titled “The Epistemic Space: The Cairo City Museum”, were founded on the conceptualization of Cairo as a palimpsest – a layered historical archive. Within this framework, students investigated urban morphology and building typology, crafting a contemporary architectural language grounded in historical precedent.

By reinterpreting an abacus of architectural elements, students developed proposals that bridge past and present, constructing a cohesive dialogue between tradition and modernity. The idea of a museum that encapsulates Cairo’s historical evolution is embedded in a broader narrative: reclaiming the city’s identity while projecting it into the future. Their architectural investigations were enriched by analyses of residential, religious, and monumental Islamic buildings, and further deepened through literary reflections inspired by Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz, whose Cairo Trilogy captures the intricate genius loci of the city.

The forma urbis of Africa’s most populous capital remains a fragmented and cacophonous aggregation – a megalopolis where the urban fabric serves as an evolving record of its historical geography. The historic core of Cairo continues to grapple with asserting its identity within this sprawling contemporary landscape – yet it remains a critical architectural resource for imagining a contextualized urban future. The Cairo City Museum is envisioned not merely as a repository of artefacts but as an active agent in stitching together the city’s fragmented fabric, rendering its layered past legible and accessible. Its spatial configuration maintains continuity with the surrounding urban environment, where labyrinthine alleys open into secret courtyards and gardens, echoing the spatial logic of historic Cairo. Locating the studio in the UNESCO-protected district of Old Cairo reflects a pedagogical commitment to immersing students in a culturally and historically rich context. Designing a contemporary public building in such a setting necessitates a methodical, empirical process – an approach rooted in learning from the past. Site visits, analytical drawings, and physical models formed the foundation of the students’ design methodology, nurturing a deep understanding of architectural composition. In this educational framework, architecture is not an arbitrary act but a structured language, complete with its own syntax and grammar. By engaging with Cairo’s local architectural idioms within a global design discourse, students created proposals that are not alien impositions but meaningful contributions to the city’s evolving identity.

The 2023/24 cohort includes: Ahmed Gabr, Ali Tarek, Farida Shouman, Ghada Hossam, Habiba Riad, Jana Foda, John Faragalla, Jomana Sami, Karma El Antably, Lana Yossry, Lucia Ramses, Maria Nabil, Mariam Hendawy, Mariam Mohammad, Mariam Rumaieh, Marina Emil, Nelly Adel, Nourhan Abdullah, Passant Samir, Raheem Khaled, Rana Dakroury, Roaa Tawfik, Salma Hefnawi, Salma Ibrahim, Salma Moussa, Sarah Elkady, Yoanna Sameh

The 2024/25 cohort comprises: Abdullah Aboelyazeed, Jumanah Shehatah, Abdelrahman Ahmed, Ahmed Mahran, Ali Abdelrahman, Mohamed Fahmy, Ali Bassiouni, Omar Abed, Ali Ibrahim, Ganna Eldessoki, Noureen Ali, Habiba Galaby, Nada Fahmy, Hana Hassaballah, Nour Hammad, Jana Rashwan, Nouran Elshall, Laila Elbatesh, Malak Said, Lilian Tadrous, Mirna Nabawy, Lina Seireg, Mahenda Mahmoud, Malak Abdelghany, Mariam Dewedar, Rwalin Elashry, Mariam Ramadan, Mariam Elkoush, Mariam Moharam, Merna Dimetry, Mathew Gondy, Nabil Aloraby, Youmna Elaidy, Nour Elashmawi, Omar Abdelhady, Omar Alrefaei, Rahma Salem, Sara Ahmed, Rana Elmamlouk, Rawan Hussein, Yara Khafagy, Zeina Eldeeb.

Manlio Michieletto, associate professor, Department of Architecture and Urban Design, GUC German University in Cairo, Egypt

This research aims to analyze students’ proposals from two iterations of “Design Studio V,” both from methodological and compositional perspectives, focusing on their design choices for a new museum in Cairo. The first studio, conducted in 2023/24, and the second, in 2024/25, were titled “The Epistemic Space: The Cairo City Museum.” The term epistemic refers to the idea that the architecture of Cairo functions as a palimpsest – a historical archive of constituent elements and their compositional qualities.

Through the study of urban morphology and building typologies, students were able to develop an abacus of architectural details, which they reinterpreted using contemporary design strategies. The concept of a museum dedicated to the city of Cairo – one that narrates its evolution over time – is part of a broader effort to reappropriate the identity of the place. In this framework, the Old City of Cairo is not merely a backdrop, but a source of architectural material and inspiration.

The analysis of the traditional Islamic house, religious buildings, and monumental structures was enriched by literary readings, particularly the Cairo Trilogy by Nobel Prize winner Naguib Mahfouz. His work gave voice to the city’s deepest and most intriguing genius loci, offering an atmospheric and humanistic counterpoint to the spatial studies.

The Cairo Museum project thus emerges not only as a physical structure echoing a tradition to be resumed, but as an architectural instrument capable of re-stitching the fragmented urban fabric – rendering it legible, accessible, and meaningful. The museum’s spatial language establishes a continuum with the city’s fixed urban scene, where the dense sequence of alleys opens into hidden courtyards and gardens. This choice reflects an intention to integrate contemporary architecture within a living historic environment.

The decision to work for two consecutive years within the UNESCO-protected area of Old Cairo was deliberate. It aimed to expose students to the complexity of real-world urban contexts – places that simultaneously challenge and inspire. Architecture, especially within such a charged context, cannot be invented on a “Monday morning.” It requires principles derived from empirical study – observations, site inspections, analytical drawings, and case-study models – which informed the students’ compositional strategies and, more importantly, their acquisition of a method.

Just as language relies on grammar and syntax, architecture requires structure and logic. In this studio, the goal was to articulate a local architectural language that can operate within a global framework – ensuring that the students’ work is not perceived as an alien insertion, but as a meaningful fragment within Cairo’s ongoing urban narrative.

A city of profound historical depth and cultural significance, Cairo represents an urban framework where layers of civilizations, architectural traditions, and socio-political transformations have continually shaped its form and identity. As one of the world’s most enduring metropolises, Cairo embodies a dynamic interplay between heritage and modernity – constantly reinventing itself while preserving its intrinsic character. The Cairo City Museum, envisioned as an institution dedicated to narrating this multifaceted urban history, serves as a bridge between past and future. It offers both a spatial and intellectual framework through which the city’s evolution can be explored and understood.

Cairo’s urban narrative dates back to antiquity, when Memphis – the capital of the Old Kingdom – flourished as a center of political power and cultural innovation. The city’s strategic location at the crossroads of the Nile Valley enabled its emergence as a hub of trade and administration. With the founding of al-Fustat in 641 CE by Amr ibn al-As, Cairo developed into a prominent Islamic capital. Over the centuries, successive dynasties – the Fatimids, Ayyubids, Mamluks, and Ottomans – left indelible marks on the city’s architectural and urban fabric, from monumental mosques and palaces to labyrinthine alleyways and vibrant souqs.

These layered transformations are extensively documented in Warner’s The Monuments of Historic Cairo: A Map and Descriptive Catalogue (2005), which offers a comprehensive mapping of the city’s architectural heritage.

The 19th and 20th centuries brought radical changes to Cairo’s urban form. Under Khedive Ismail, the city underwent sweeping transformations modeled on Haussmann’s Paris, introducing wide boulevards, formal squares, and modern infrastructure that starkly contrasted with the dense medieval core. British colonial influence further reshaped the city’s planning, governance, and architectural expression – seen in the creation of planned communities such as Garden City, Heliopolis, and Maadi, which embodied European ideals within an Egyptian context. The mid-20th century marked the rise of modernist architecture, with landmark projects such as the Cairo Tower and a series of governmental and cultural buildings expressing Egypt’s postcolonial aspirations. The Cairo City Museum engages critically with these narratives, analyzing how colonial and modernist interventions have reconfigured the city’s spatial and social fabric. These dynamics are explored in depth by Raymond (2000) in Cairo and Sims (2012) in Understanding Cairo: The Logic of a City Out of Control.

In parallel with formal planning, informal urbanization has become a defining force in Cairo’s contemporary landscape. Fueled by rural-urban migration and socio-economic inequality, the growth of unplanned settlements has produced a city where informality now dominates its spatial logic. The densification of neighborhoods, the evolution of vernacular housing, and the adaptive strategies of informal communities reveal a resilient, self-organized urbanism that challenges top-down planning models. As Sims (2012) emphasizes, informal settlements constitute the primary mode of expansion in Cairo today, creating a continuous negotiation between state authority and grassroots development. The Cairo City Museum addresses these phenomena as essential to understanding the lived realities of the majority of Cairenes. Cairo’s approach to heritage preservation has been marked by both achievements and challenges. Conservation initiatives in Historic Islamic Cairo, the restoration of royal palaces, and the adaptive reuse of colonial-era buildings illustrate the ongoing tension between safeguarding cultural heritage and accommodating contemporary urban demands. Williams (2018), in Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide, provides critical insights into these efforts, revealing the practical and political complexities of heritage management in a rapidly changing city.

By documenting these histories and spatial trajectories, the Cairo City Museum aspires to be more than a repository of artifacts. It functions as a platform for reflection and discourse, advocating for sustainable preservation strategies that integrate Cairo’s rich historical identity with its evolving urban needs.

Cairo is home to a number of renowned museums that document the city’s rich and layered history – from ancient artifacts to modern cultural expressions. The Egyptian Museum, housing the world’s most extensive collection of Pharaonic antiquities, has long served as a cornerstone of historical preservation. The recently inaugurated Grand Egyptian Museum near the Pyramids of Giza aims to redefine the narrative of Egypt’s ancient heritage through state-of-the-art exhibitions and immersive technologies. Equally significant is the Museum of Islamic Art, which presents an unparalleled collection of artifacts that reflect the artistic and architectural legacy of the Islamic dynasties that once ruled Cairo. Beyond these monumental institutions, Cairo also hosts museums fo-

cused on modern urban and social history. The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization adopts an interdisciplinary lens, covering Egypt’s cultural, social, and industrial development across time. However, despite the city’s extensive cultural infrastructure, none of these institutions is dedicated specifically to Cairo’s urban history and spatial transformations – a fundamental gap in the city’s museological landscape. The Cairo City Museum seeks to address this absence by offering a space where the evolution of the metropolis itself becomes the central subject. It is conceived not as a repository of static artifacts but as a platform for interpreting the city’s dynamic and ongoing processes of change.

Internationally, several institutions serve as successful precedents for this model. The Berlin Stadtmuseum (the Museum of the city) offers a comprehensive account of Berlin’s architectural, political, and social transformations through multimedia installations, urban models, and interactive exhibits. The Museo di Roma (the Museum of Rome) presents the history of the Italian capital’s urban development, employing historical maps, artworks, and reconstructions of key moments in the city’s growth. In New York, the Museum of the City of New York blends historical documentation with contemporary urban issues, fostering public dialogue around the city’s continuous transformation and future challenges. These institutions provide valuable reference points for the conceptualization and curatorial strategies of the Cairo City Museum. They demonstrate how urban history can be presented in a dynamic and engaging manner – making the city itself both subject and exhibition. In doing so, the Cairo City Museum aspires to become a new cultural landmark, one that narrates the complexities of Cairo’s past, reflects on its present, and envisions its future within a rapidly evolving urban context.

Designing the Cairo City Museum offers an opportunity to integrate architectural elements rooted in the city’s historical built environment. Cairo’s rich architectural legacy – from the Fatimid period through Ottoman and Mamluk dynasties to modernist interventions – presents a broad repertoire of design strategies that can be reinterpreted in a contemporary museum context.

Key elements such as courtyards, mashrabiya screens, and domes, prominent features of Islamic architecture, provide both aesthetic and functional advantages. Courtyards, widely used in historic Cairene residences and religious complexes, improve natural ventilation, introduce daylight into interior spaces, and establish contemplative atmospheres. Mashrabiya – ornamental wooden latticework traditionally used in windows – can be adapted using modern materials to enhance passive cooling and light filtering while maintaining visual

privacy. Their reinterpretation offers a sustainable design solution that pays homage to tradition.

Domes and vaulting techniques, exemplified in iconic structures like the Mosque of Sultan Hassan and the Qalawun Complex, contribute not only to structural efficiency but also to spatial grandeur. These elements offer symbolic and climatic value, establishing visual hierarchies and modulating internal temperatures.

The principle of adaptive reuse – as demonstrated in restorations such as Beit El Suhaymi – emphasizes the potential of combining historical continuity with modern needs. Materials such as local limestone, intricate wooden detailing, and geometric patterns can help embed the Cairo City Museum within its urban and cultural context. Through such an approach, the museum becomes not merely a space of exhibition, but a cultural landmark that embodies a dialogue between past and present, and a model for sustainable, place-sensitive urban development.

Since antiquity, the courtyard has served as one of architecture’s most foundational spatial archetypes – mediating between function and symbolism, myth and reality. In the dwellings of the pharaonic dynasties, the courtyard was both a climatic device and a domestic fulcrum, regulating ventilation, light, and social life. This environmentally responsive model evolved into a symbolic and ritual space in sacred architecture, where the courtyard assumed a metaphysical role.

Temples such as Philae, Dendera, and Deir el-Bahari (the temple of Hatshepsut) reinterpreted the domestic courtyard into spaces of eternity – thresholds between the human and the divine, between terrestrial life and cosmic order. Defined by colonnades, reliefs, and inscriptions, these courtyards embodied theological narratives, projecting the intimate logic of the home into monumental and sacred contexts.

The courtyard’s typological resilience is evident throughout Mediterranean and Islamic architectural traditions. Its enduring relevance lies in its adaptability – a spatial logic that balances environmental pragmatism with cultural and symbolic resonance. In the urban fabric of Old Cairo, the courtyard house stands as a quintessential typology. Residences such as Beit El Suhaymi and Beit Zeinab Khatoun illustrate the courtyard’s functions as a climatic regulator, a social nucleus, and a privacy-enhancing device (Raymond, 1993).

The inward orientation of these homes protected them from the harsh external climate while allowing for natural cooling through the stack effect. Integrated mashrabiya further enhanced passive ventilation and light modulation, maintaining privacy without compromising comfort (Fathy, 1986).

Cairo’s Islamic courtyard houses also reflect a rich socio-cultural matrix. Their spatial hierarchies adhere to principles of gender segregation and hospitality, with designated areas for public reception (salamlik) and private family life (haramlik) (Bianca, 2000). The courtyard often hosted a central fountain or garden, reinforcing the connection between architecture and nature, and promoting thermal comfort and introspection (Schoenauer, 2003). The mashrabiya – while technical in function – also acts as a cultural signifier, embodying ideals of modesty and community (Ragette, 2003).

The persistence of the courtyard archetype in Cairo, despite pressures of urban densification, attests to its adaptability and architectural intelligence. As Abdelmonem (2015) argues, its contemporary reinterpretation offers meaningful strategies for urban sustainability and cultural continuity. In the context of the Cairo City Museum, the courtyard provides not only a performative space but also a symbolic anchor – an architectural memory capable of informing a modern civic institution grounded in Cairo’s enduring identity.

Bibliography

Abdelmonem, M. G. (2015). The Architecture of Home in Cairo: Socio-Spatial Practice of the Hawari’s Everyday Life. Routledge, London.

Bianca, S. (2000). Urban Form in the Arab World: Past and Present. Thames & Hudson, London.

Fathy, H. (1986). Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture: Principles and Examples concerning Hot Arid Climates. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Ragette, F. (2003). Traditional Domestic Architecture of the Arab Region. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

Raymond, A. (1993). Cairo. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Schoenauer, N. (2003). 6,000 Years of Housing. W.W. Norton & Company, New York.

Sims, D. (2012). Understanding Cairo: The Logic of a City Out of Control. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

Warner, N. (2005). The Monuments of Historic Cairo: A Map and Descriptive Catalogue. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

Williams, C. (2018). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

Yara

Galal, teaching assistant, Architecture and Urban Design Department, GUC German University in Cairo, Egypt

“As an urban unit, the Cairene harrah had a complex nature whereby interrelated spatial and social structures complemented each other and integrated in harmony in the absence of formal organisation or authoritarian control, which created an old mystery about how it came to take on such an interrelated forms”1.

During Design Studio V in the German University in Cairo, the students were tasked to design a museum in the historic heart of Cairo. Designing in a very precise yet constantly changing context came with its challenges, the major challenge was to understand a context that has been morphing and adapting in response to power change for a Millennia. The current historic or Islamic Cairo that we have today was mostly built during the Ottoman Empire. It was a city built to encompass previous cities. Gayer Anderson Museum, Previously Bayt El Kritiliya or House of the Cretean Woman, is a prime example of domestic architecture during the Ottoman time.

The residents during the Ottoman period defined the boundaries of their home according to certain socio-cultural codes and costumes followed by society. For them, the local alley in front of the home is part of their home, it is essentially a bigger part home their home that includes other close families. The local alley also attends to the needs of the house to invite guests and share meals. To them home extends beyond the physical boundaries of the house. Abdelmoneim writes “The extent of home is defined by the boundaries residents construct around what they believe to be their unchallenged home. These boundaries could be physically constructed by ownership rights in the case of fences , lawns or backyard gardens, or mentally and cognitively organised to extend beyond the ownership lines, for example, to the local street”2

Egyptians during the Ottomans lived in urban units or quarters called Harrah.

The infamous Harrah of Cairo weren’t a product of the Ottomon time, they weredeveloped from earlier urban planning in the fatimid period, Mainly it is an urban unit where its function extends beyond domesticity to include social and economic activities of the residents. Hence the connection between occupation, ethnicity and domestic space discussed by Janet Abu-lughod. Abdelmoneim defines the borders of a harrah through social means, as a group of people unified by occupation, religious, or ethnic background, a unit segregated from the other units of the city socially while still physically connected with limited access through controlled gates and walls.

Ottoman Cairo’s main urban unit was the Harrah, defined as a mass of solid buildings surrounding a network of dead end lanes. The hierarchy of public streets during the time starts with a Sharei or a Qasaba, which is a main street outside of the Harrah where shops and public buildings directly overlook it and opens towards it, it is the route of heavy traffic and the basic layer of the city.

The Gates of the Harrah overlook the main street, the gates usually close at

Detailed map of Cairo’s Harrahs done by Pierre Jacotin, Edme-François Jomard, and other scientists of the French Expedition. Published in Description de L’Égypte (1809-1828).

night and are guarded by a Bawab (doorman). Going into the Gate of the harrah, one is faced with The Darb, the darb is the spine of the Harrah, a semi-private alley with limited access from the outside. In some cases, the darb overlooks purely residential houses, and other times overlooks workshops and shops belonging to the residents. The Zuqaq/ Atafa/ Sikka, are a small dead-end street branching off the Darb and overlooking a cluster of residential building, they have no direct access to the outside of the harrah, hence protecting the privacy of the residents. During specific occasions such as weddings or Ramadan Iftar, the Zuqaq becomes an extension of the house’s public space.

Residents of the Harrah view it as their uncompromised territory, its meaning as a home is emphasised through the availability of the public space of the harrah as a gathering space where residents gather to eat and sit as they do at home. The harrah’s public space can turn to private without changing the users or physical characteristics of the space.The users ability to extend their home into the harrah’s public space is an ownership action by the locals to exercise control. Abdelmoneim explains “ the harrah emerges as an intermediate practice of home. Where security and protection are guaranteed and privacy is combined with shared activities”3

Urban planning in Islamic cities based its rules upon the rules of Sharia (Islamic law based on teaching from the Quran), which prioritizes privacy of the household; this is especially true in the planning of Cairo under the Ottoman. The city was extremely compact with every available inch built on, however it operated within a very precise set of rules set by the ruling body. Architecture of the harrah was characterized by a solid wall on the ground floor with minimal opening to prevent the public from looking in, opening started from the upper floor. The upper floors are extruded into the harrah’s void with approximately 1m, with the opening covered by Mashrabiyas. This was to preserve privacy but also to expand the area of the house. The master builder had to design the house externally and internally so that it avoids privacy conflicts.

As space was usually so scarce in Cairo, and houses were built to withstand the passage of time where the household changes but the building stands, some adaptations were necessary. A really common practice between residents in the Harrah is Mounting, the residents agree with each other that a neighbour can build a room over the gate of the harrah or extrude an overhang over a street. Thus increasing the complexity of the city.

A main characteristic of housing in a traditional harrah are the extruded Mashrabiyas from the top floors of buildings. It enables transparency to the inner residents of the house while obstructing the view completely from the outside. It is a woven screen of wood, that poses social and political meaning. The mashrabiyas were usually exclusive to accompany spaces used by women, it allowed women the access to observe and supervise activities in the public domain while keeping their privacy. Traditional Islamic houses in Cairo have a system in their facade design, the outer facades have minimal openings and these openings are usually covered by Mashrabiyas. On the other side, the inner courtyards have significantly more openings which are also covered by mashrabiyas. The inner facades of the courtyard are considered the main facades of the building and its openings are bigger in proportions.

Architecture during the Ottoman period was characterised by multi-story residential buildings, this contrasts with other cities in the Ottoman Empire, due to the lack of spaces within the walls of the city. The houses usually had an irregular plot because the residents had to make use of every available space. Usually the plot was closely surrounded with other builds, which led to some creative solutions in dealing with ventilation and privacy. The Hi -

erarchy within the house was in three parts, there were spaces that were used by the guests from outside the house, spaces used by the residents exclusively, and service space. The public main zone is usually at the ground level and it includes a reception space such as Qa’aa or Meqaad. In the Case of Gayer Anderson House, the public zone was on the first floor while the service zone occupied the ground floor. The public zone is usually dominated by males. While the private zone is usually on a higher level and is exclusively for the usage of women. These two zones are connected by a staircase, it acts as a strong barrier that is crossed by family members only. The daily socio-spatial practices of the residents resulted in the decision, the spatial organisation of the house is influenced from inherent ideology of the society and their daily ritual.

Ottoman housing had a characteristic that was common between all classes, which is the various clear heights and leveling within houses. It is very common to find a variety of leveling in the roof not only in one story but also in the same room, this was to create a spatial hierarchy in a singular space. The more important the space the higher the ceiling, the lower ceiling is usually for secondary functions. Difference in ground leveling also exists to hint into moving from a space to another space.

Houses with a courtyard seemed to have different levels of integrating the courtyard in the circulation of the building, sometimes entering the houses would lead into a winding corridor called Majaz to prevent direct visual connection to the outside then a staircase on one side and the courtyard on the other. The other type integrates the courtyard more with the vertical circulation, while the door leads to a Qa’aa rather than the stairs. Courtyards play a significant role in the ventilation of the house and the existence of the windows; when a courtyard exists, the majority of openings in the building is oriented towards it. Circulation in housing during the Ottoman period was mostly dependent on vertical circulation using the main staircase. This allowed a variety of spatial configuration around the core while still connecting the ground floor to the roof.

The reception spaces were the public spaces in houses at the time and they were usually used for guests. The public spaces were usually decorated with painted wood ornamentation and marble., and they were characterized by how easy it was for the guest to reach them. One example of such a space is Al Qa’aa, it is a big rectangular main space with different heights. The middle

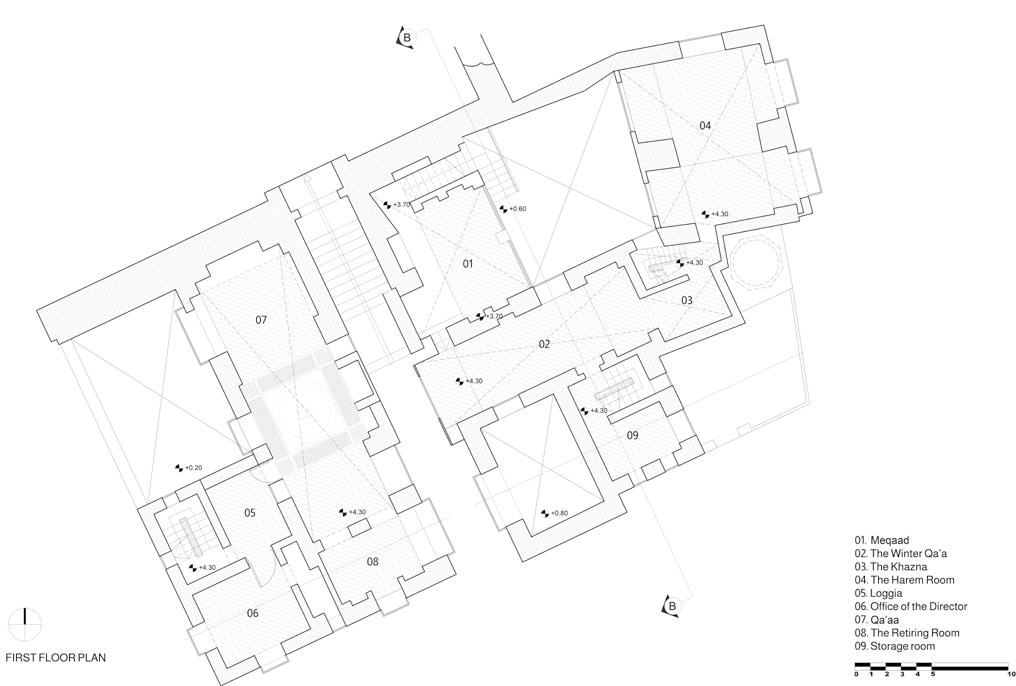

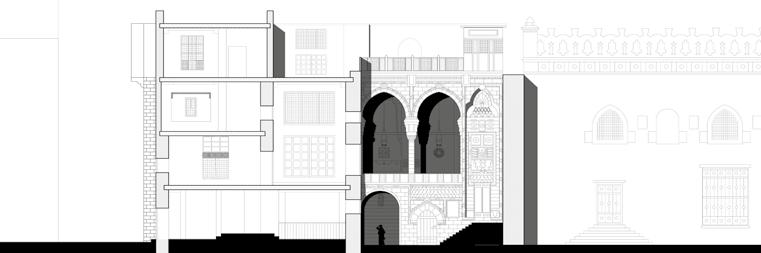

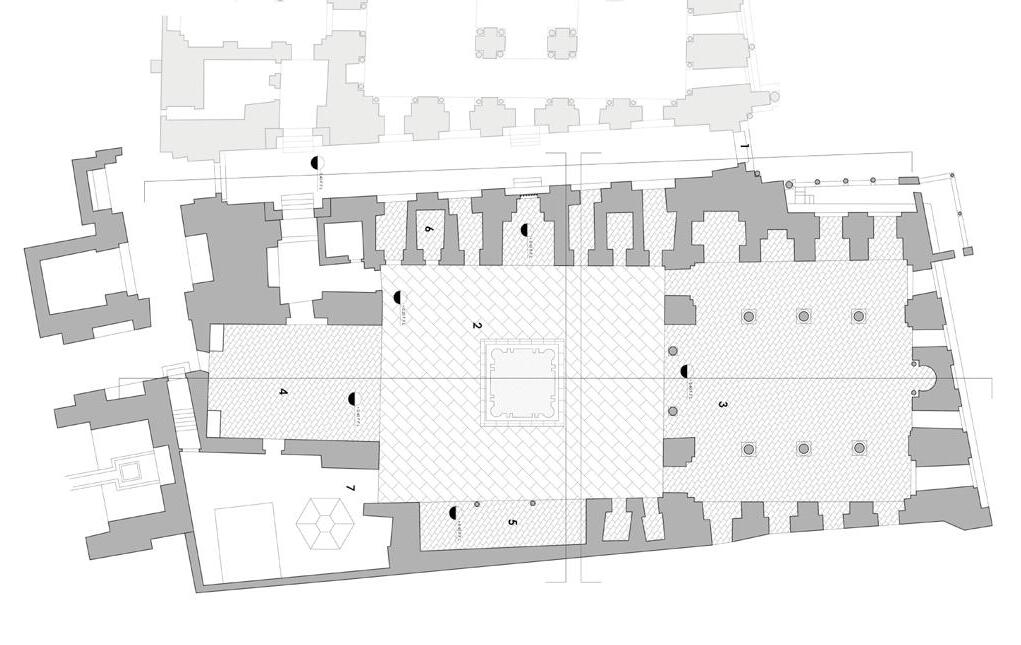

Plan of the first floor of Gayer Anderson museum, previously known as House of the Cretean Woman. The plan clearly shows that the house used to be divided into two middle class houses, then later on compined. The Meqaad (01) is shown overlooking the inner courtyard of the first house, while the Qa’aas (02)(07) are aglomorated around the inner courtyard to prompt ventilation.

Section through Gayer Anderson Museum, showing the Meqaad overlooking the inner courtyard of the house. Additionally the dection shows the spatial composition of the different heirarchies of room within the house with the Qa’aa and the biggest space in height to signify importance.

part of the Qaaa is usually the highest with a Iwan on both sides with a lower roof, however middle class houses typically had one Iwan. some houses tried to solve the issue of privacy by implementing two sets of staircases, one for the Qa’aa and one for the residents. But that was applicable when the Qa’aa was not on the ground floor.

Maalqaf and Shokhshekha are usually the highest points in traditional buildings. The Maalqafs are usually corresponding to the wind direction to provide ventilation to several stories within the building and lowers the pollution of the air. The Shokhshekha is an octagonal element usually found on top of the centre of a Qa’aa, its purpose is to provide natural light and aid in the process of ventilating the room. The Shokhshekha is usually coupled with a Feskia (fountain) underneath it to cool down the air.

The Meqaad is another type of public space that is very common in big houses in Cairo. The Meqaad is similar to a loggia that overlooks the courtyard of a house, and it faces the wind direction. The living room of the family was usually more private and on the upper floors, however it has similar spatial configuration as the Qa’aaa and it was called Rewaq.

Notes

1. Abdelmonem, M.G. (2015). The Architecture of Home in Cairo: Socio-Spatial Practice of the Hawari’s Everyday Life. Routledge, London, p. 120.

2. Ibid., p. 117.

3. Ibid., p. 118.

Bibliography

Abdelmonem, M.G. (2015). The Architecture of Home in Cairo: Socio-Spatial Practice of the Hawari’s Everyday Life. Routledge, London.

Abu-Lughod, J.L. (1971). Cairo, 1001 years of the city victorious: 1001 Years of the city victorious. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Fathy, H. (1986). Vernacular Architecture: Principles and Examples with Reference to Hot Arid Climates. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Hanna, N. (2004). In praise of books: A cultural history of Cairo’s middle class sixteen to the eighteenth century The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

Hanna, N., Tusun, H. (1991). Buyut al-Qahirat = Habiter au Caire: Fi al qarnayn al-sabi ašar wa al-Tamin ašar: Dirasat Igtimaiyat mumariyt: Aux xviie Et Xviiie SIÈCLES. Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

Raymond, A., Wood, W. (2007). Cairo: City of history. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

Lilian Ehab, Salma Moussa and Mirna Nabawy, graduate students, Architecture and Urban Design Department, GUC German University in Cairo, Egypt

“El Beit Serr” – the house holds secrets, is a saying that goes beyond privacy in walls and doors in Old Cairo. It is a reflection of the layered spaces behind the dense facades, that are present either within the private homes or communal worshiping and learning buildings. Mashrabeya, a silent element, allows unseen observation while protecting a whole world in motion. Heavy stoned walls hide gigantesque open spaces of worship. This interplay between different physical, environmental but most importantly social layers is what shaped Old Cairo’s unique architectural identity. This chapter explores structures that played a key role in shaping what we know today as “Old Cairo”.

Before examining these various typologies along Muez Street, it is only right to visit the elements that delight the entrance of the street, particularly observing how near the site is to Bab Al-Futuh and the Mosque of Al-Hakim. Bab Al-Futuh, a gate and an imposing military structure, features a series of large towers and arches. It escorts the visitor into an ominous entrance, with dark narrow passage and thick walls before revealing the beginning of the old city and its sense of relief. The Mosque of Al-Hakim, continues on with the idea of shifting from a thick, complex facade to a lightweight luminous interior. The sense of calmness is also achieved through the use of tall pointed arches and stonework, balancing the heaviness seen outside the mosque.

The analysis of Old Cairo typologies begins with Beit Al-Suhaymi, an exemplary structure of Ottoman domestic architecture. The ingenuity of its architecture begins with an angled narrow entrance, leading to the central courtyard, around which are Winter and Summer Mandaras. Mandaras are a reflection of the social hierarchy back in the day, with the spatial organization of Iwan and Durqaa.

One of the main unique features of this Beit, is the Takhtaboush, a semi-open sitting space, well ventilated, intermediate between enclosed rooms and the open courtyard. Above the ground floor, spaces become increasingly private, and their planning / addition over time is fully based on the family’s needs; the first floor was preserved for women, with mashrabiyas that allow them to observe while ensuring discretion and coolness.

In fact, the sensitivity to climate and light is likewise evident in other manzils of the same typologies, such as Bayt Mostafa Gaafar and Bayt al-Khorazaty, with similar, effective thermal comfort strategies.

Aside from the concealed privacy in Beits of Old Cairo, going deeper into Muez street, is the Qalawun complex, a monumental testimony of the rich mamluk architecture of Old Cairo. The complex includes a madrasa, a mosque and a hospital. The Madrasa of Sultan Qalawun was well known as a cultural and educational center, reflecting the islamic principles and studies. The space is structured around a central courtyard with arcades and iwans organized around that central public space. These Iwans, each held a different activity which made the space more interactive for the educators and their students. This typology is also an example of using mashrabiya and domes to control light and atmosphere.

Beit Zeinab Khatoun

Ending Muez Street, one finds themself in the center of Darb Al-Ahmar, where Zeinab Khatoun Complex is located, a different architectural typology and context. Entered through a discreet bent corridor, the house reveals a richly layered spatial sequence centered around a courtyard. From the ground floor, the Maqa’ad is directly accessed through a tunneled staircase. The Main Durqa’a overlooking the courtyard through mashrabiya screens is representative of Mamluk Qa’a, flanked by iwans covered with beamed wood ceilings that serve as heat insulators and provide protection against external elements. Making use of the upward flow of warm air, the Malqafs serve large and small halls by entrapping cool air and propelling it into the halls. Together with the Shokhshekha, ensuring a continuous airflow. The nuanced privacy and gender dynamics of Old Cairo’s dwellings is embodied by the spatial logic, vertically organized with interconnected terraces and staircases, while also allowing fluid circulation and shielding internal life from external gaze. Similar to Bayt Ali Labib and Bayt al-Sinnari, this manzil exemplifies an architecture that is performative, adaptive, and carefully attuned to light, climate, and the hierarchies of space.

Located adjacent to the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, the Gayer Anderson Museum is a fusion of two 16th- and 17th-century houses later unified and restored by Major Gayer Anderson in the early 20th century. This adaptive reuse project preserves the essential typological elements of Cairo domestic architecture: the sahn, iwan, takhtaboush, and mashrabiya. The museum offers a curated experience that unveils the domestic rituals and spatial choreography of the period, while also inserting a foreign gaze into Cairo’s fabric. Like Bayt al-Khorazaty and Bayt Mostafa Gaafar, its spaces reflect layered uses and expansions over time, embodying the palimpsest nature of the city, becoming both artifact and architecture: a spatial narrative bridging cultural memory and appropriation.

PROJECT 01

Shahd Fadi

PROJECT 02

Nourhan Emmam

Roaa Tawfik

PROJECT 03

Habiba Riad

Salma Hefnawi

PROJECT 04

Raheem Khaled

Salma Moussa

PROJECT 05

Marina Soroor

PROJECT 06

Lina Ramez

Mariam El Sherbiny

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Nadeen Amged

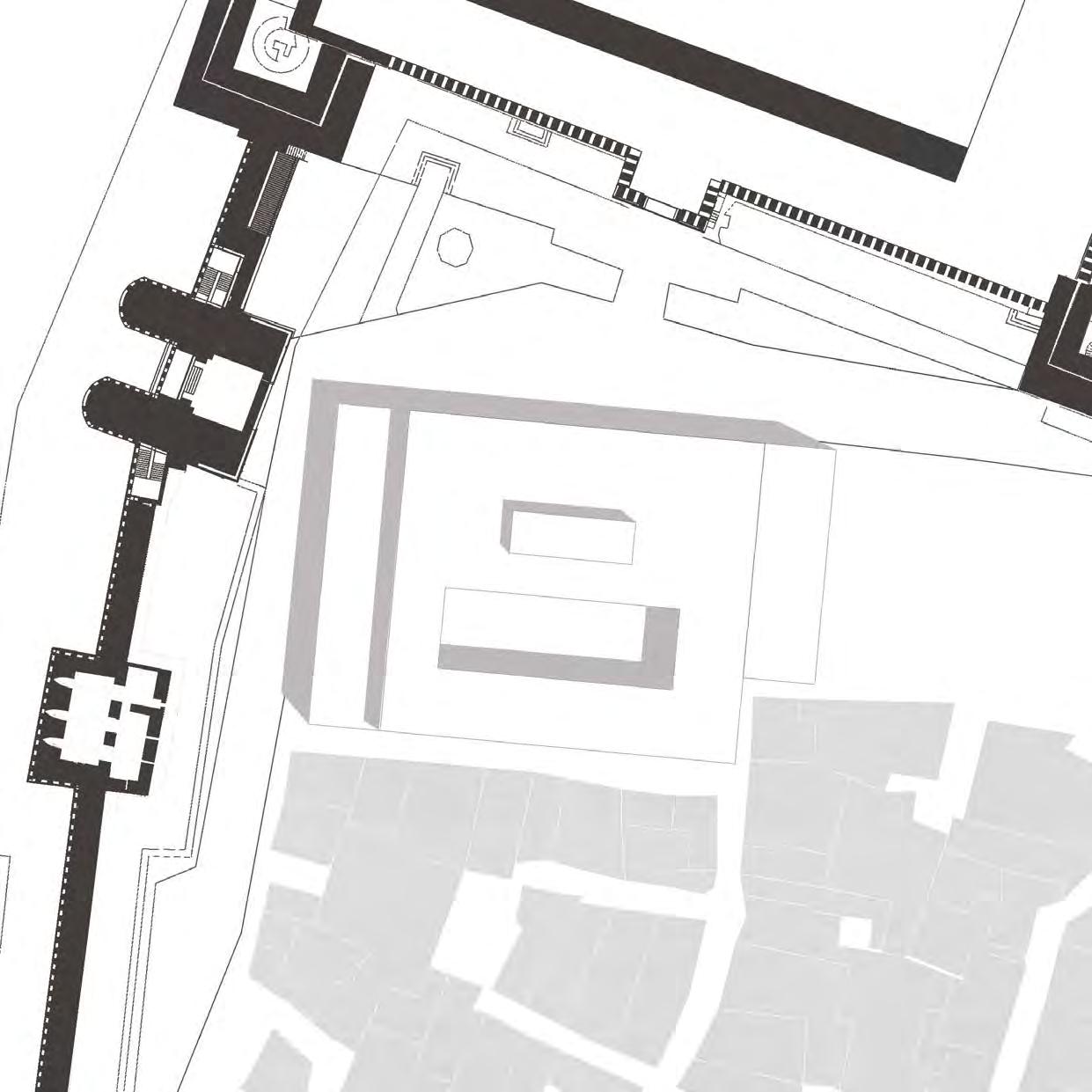

Student Shahd Fadi

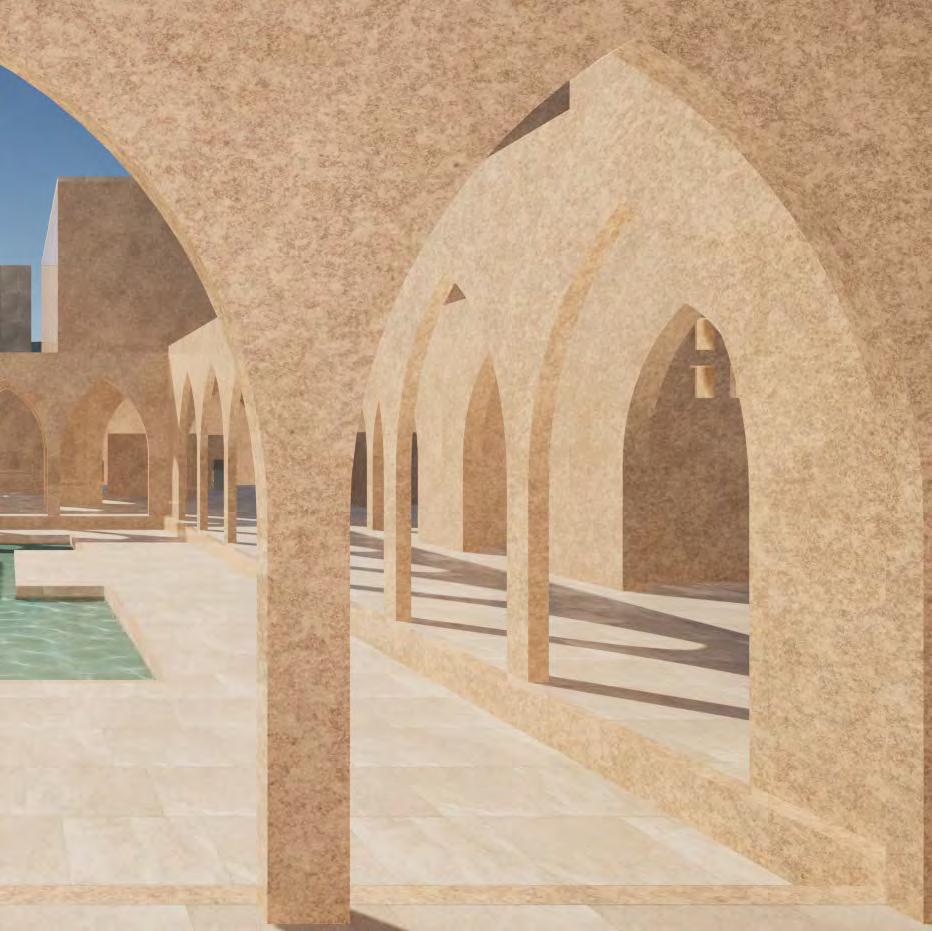

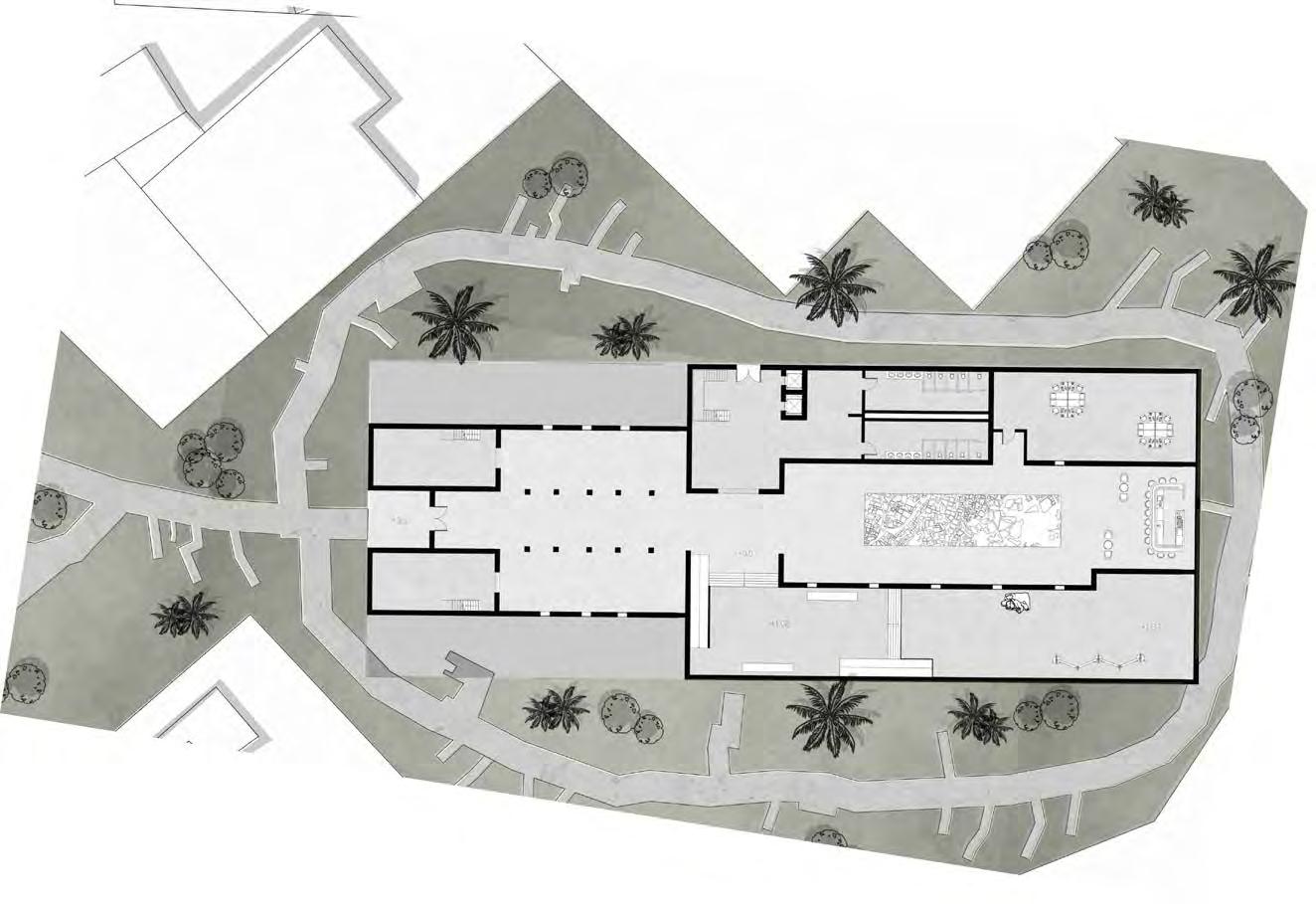

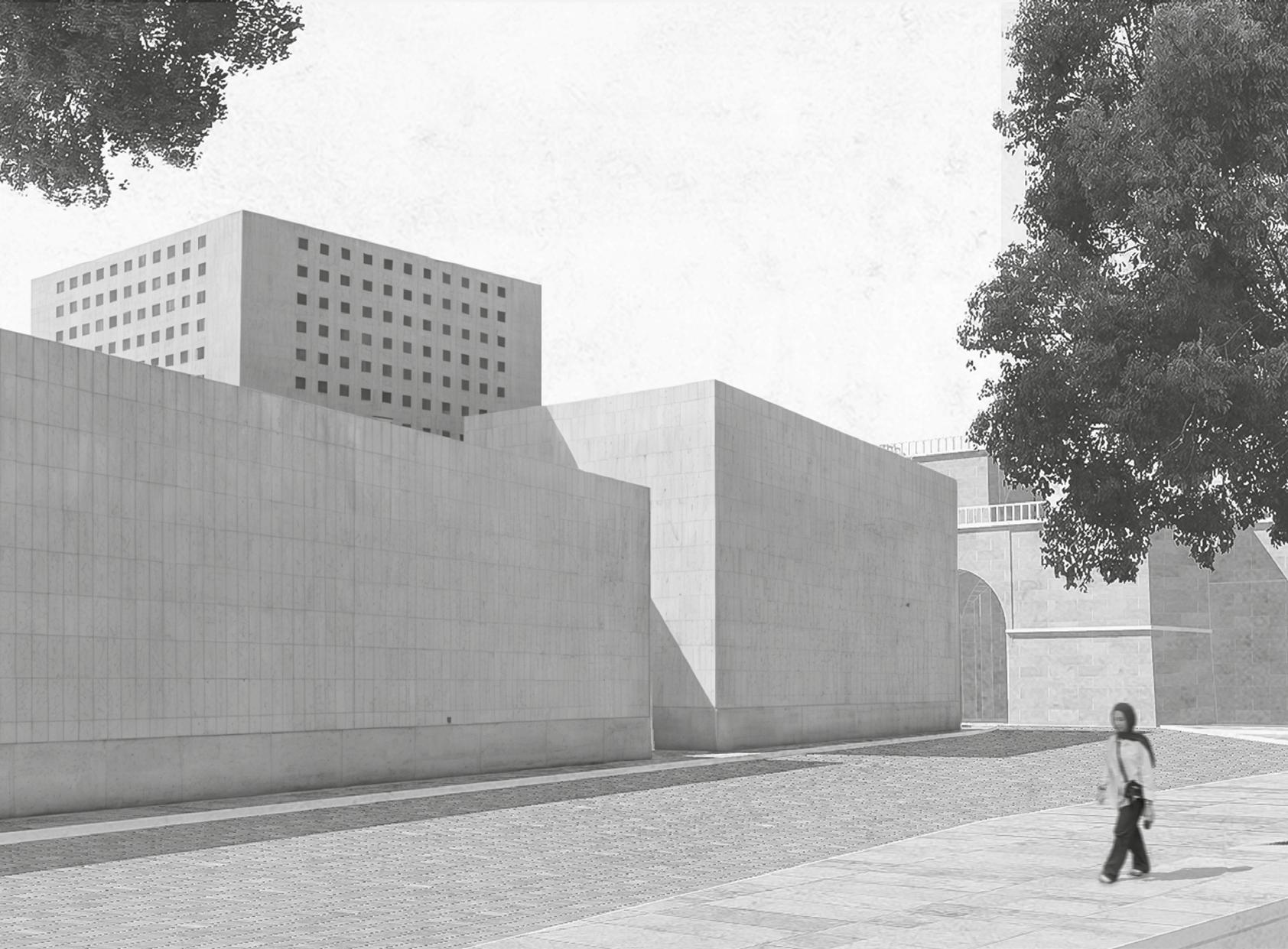

The museum’s design guides visitors through a spatial journey inspired by Old Cairo’s traditional houses. Centered around two courtyards, the entrance is positioned between them, echoing the historic “Egyptian Architecture House.” To the right, exhibition spaces narrate Cairo’s history, extending to a mezzanine library. On the left, a large city model sits beneath an open courtyard, enhancing spatial depth. A central boulevard links both sections, integrating louvers that frame views of the Mohamed Ali Palace and Citadel. Natural materials like limestone reinforce the connection to Cairo’s architec tural heritage and context

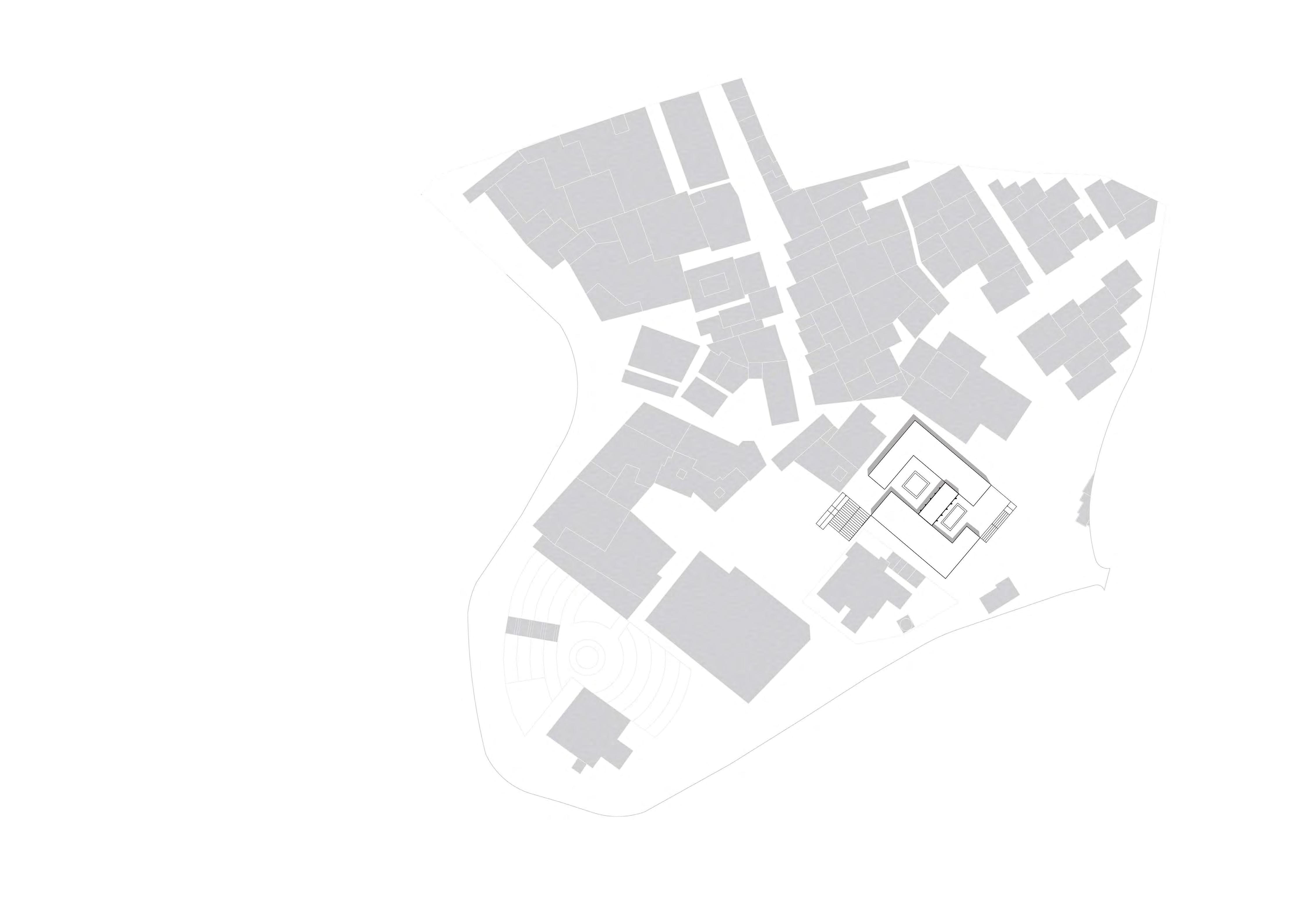

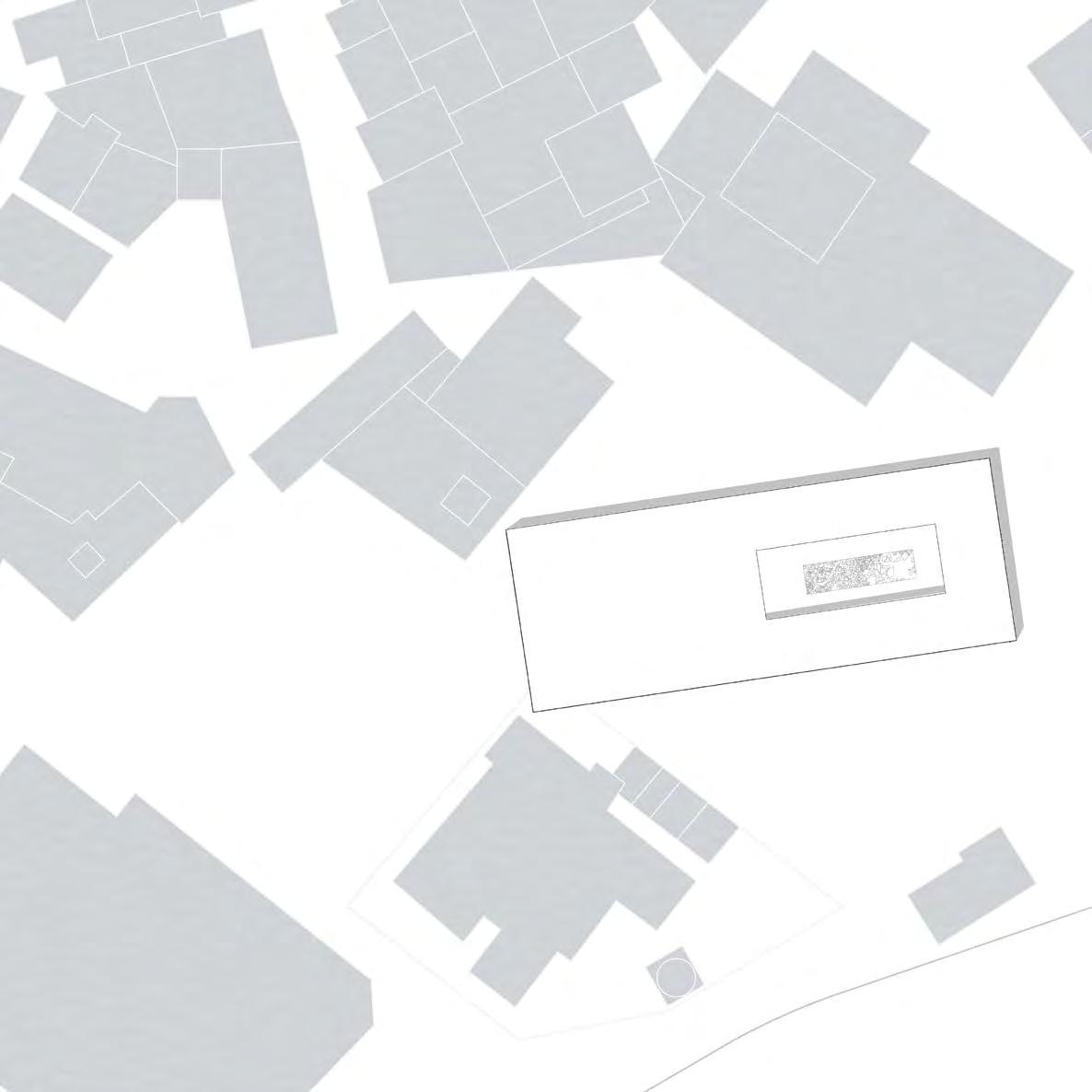

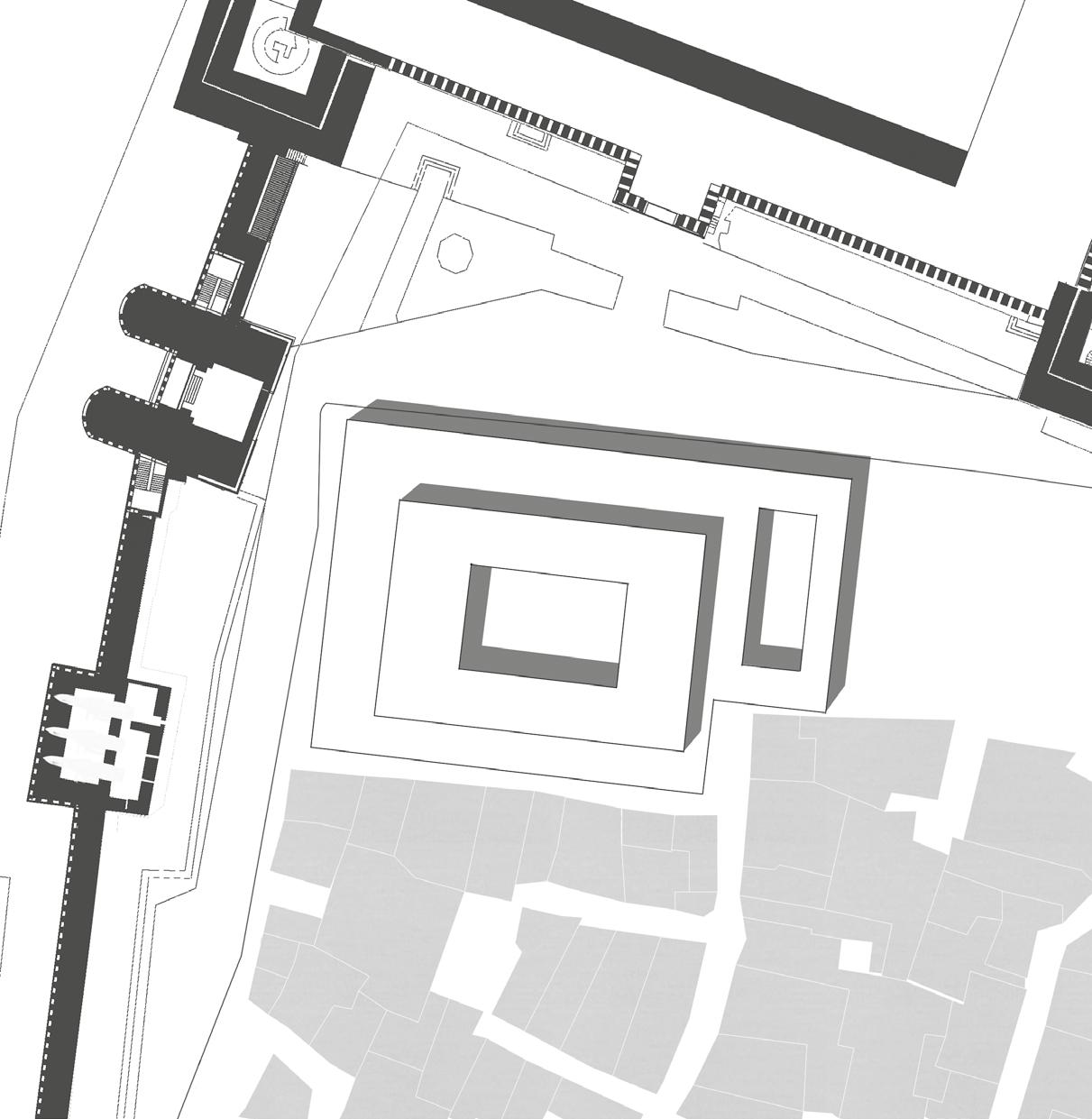

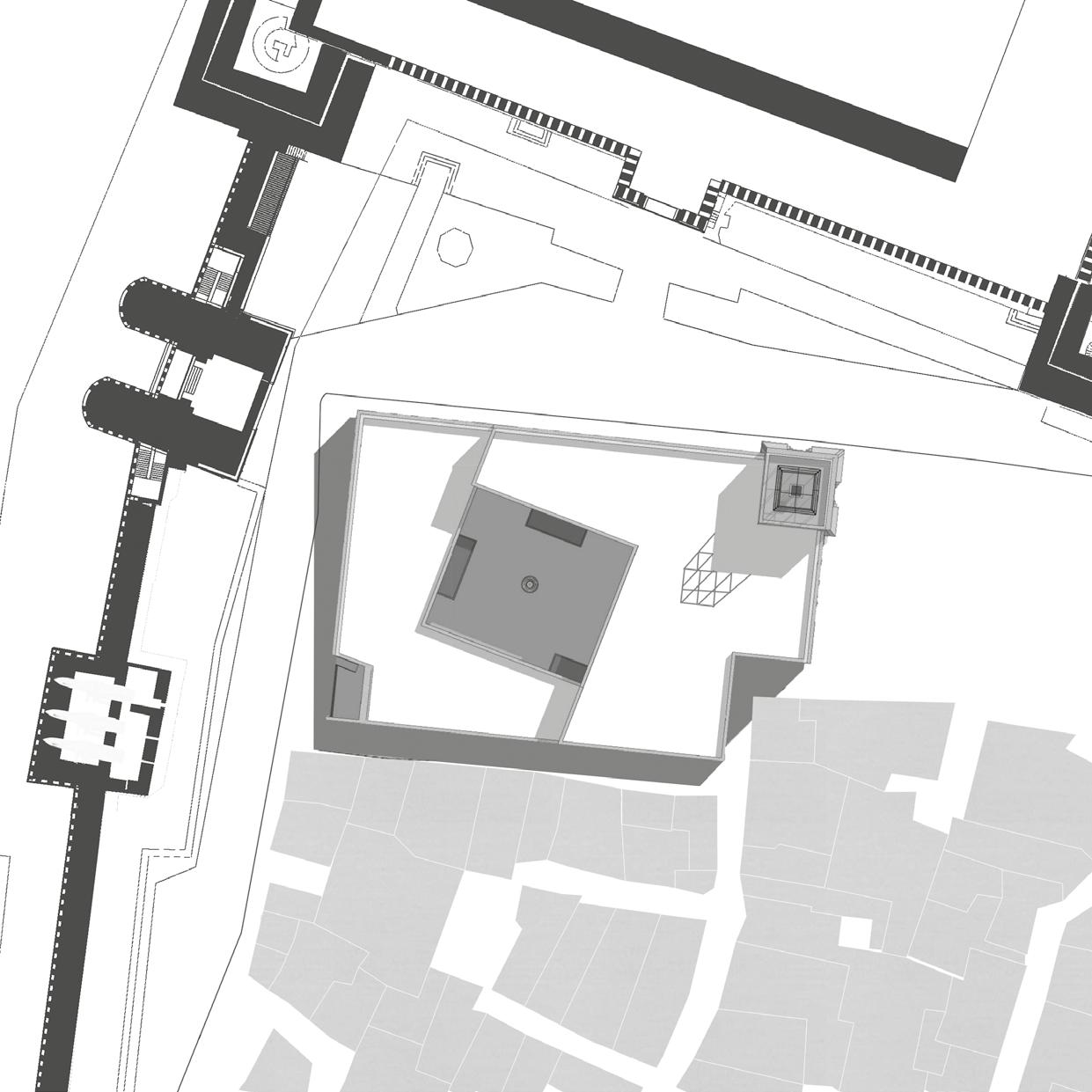

Figure (1) Shown on the left page, the placement of the museum within the conext and how it carefully aligns with the existing urban fabric.

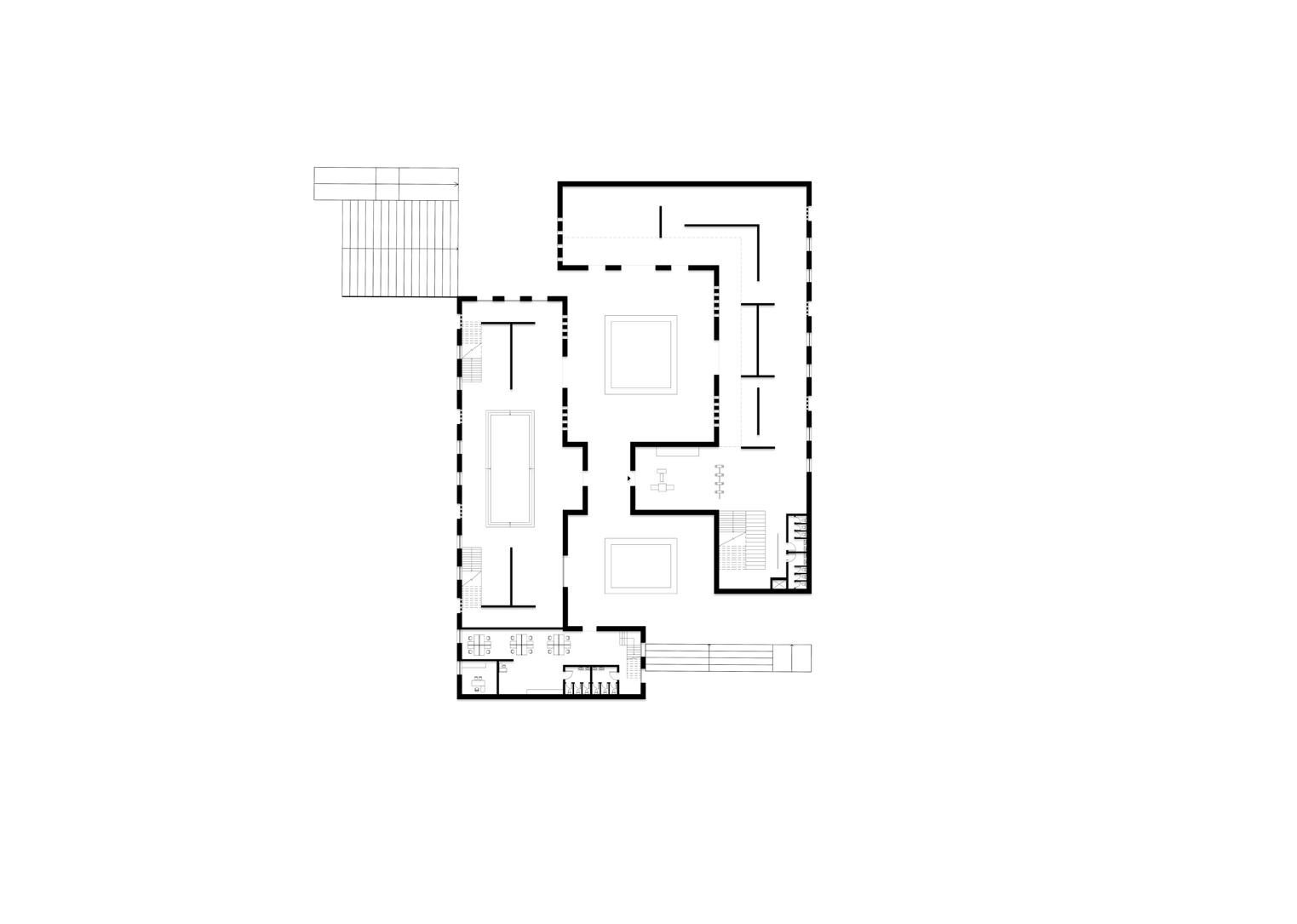

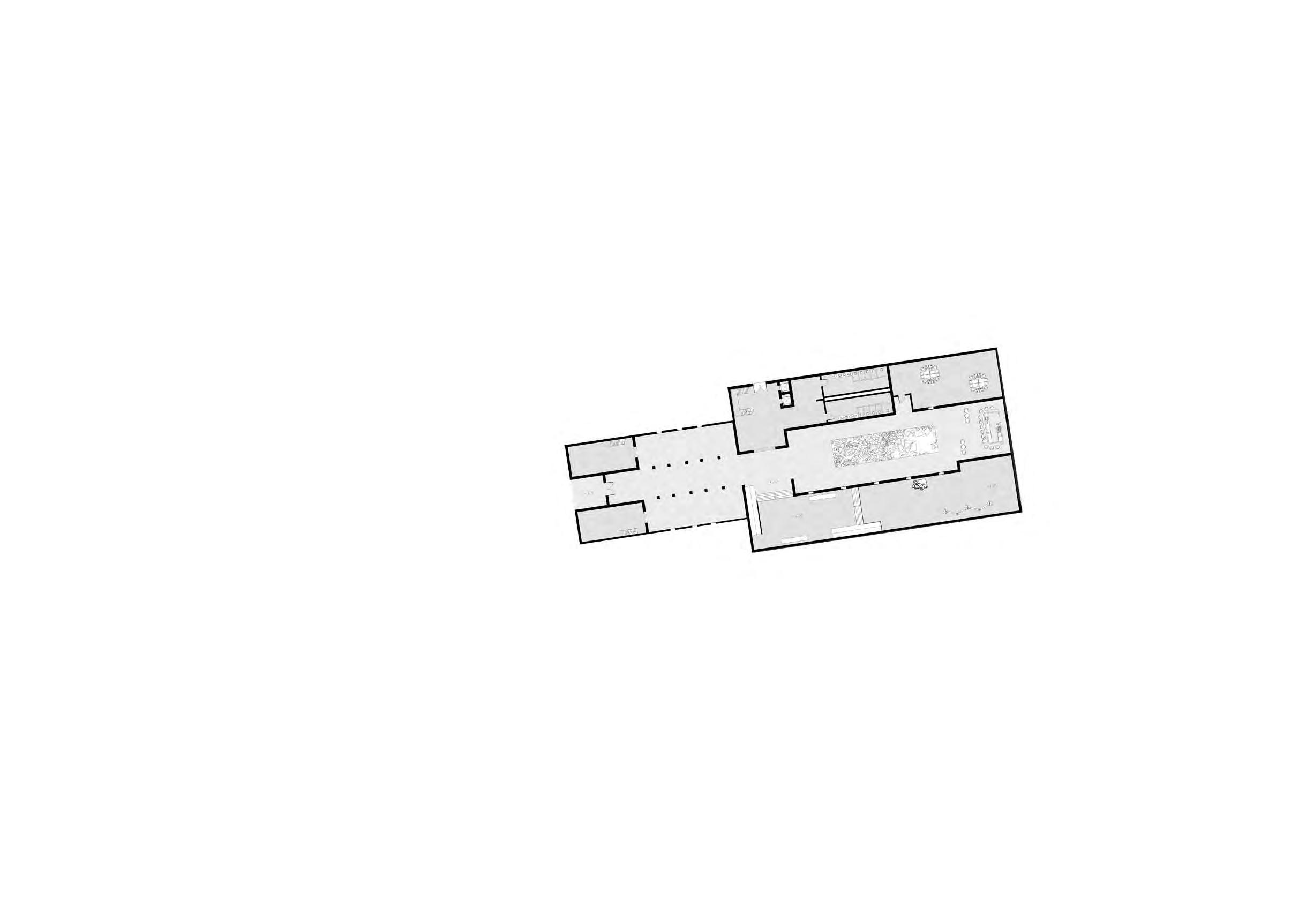

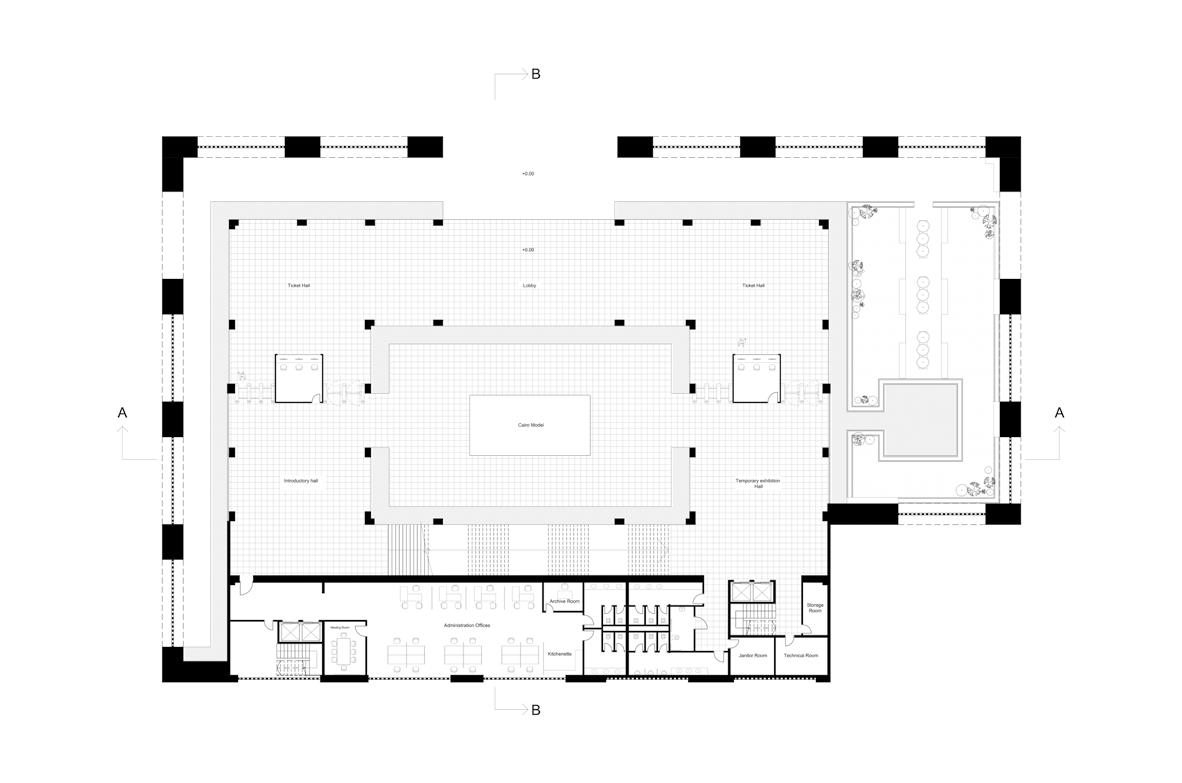

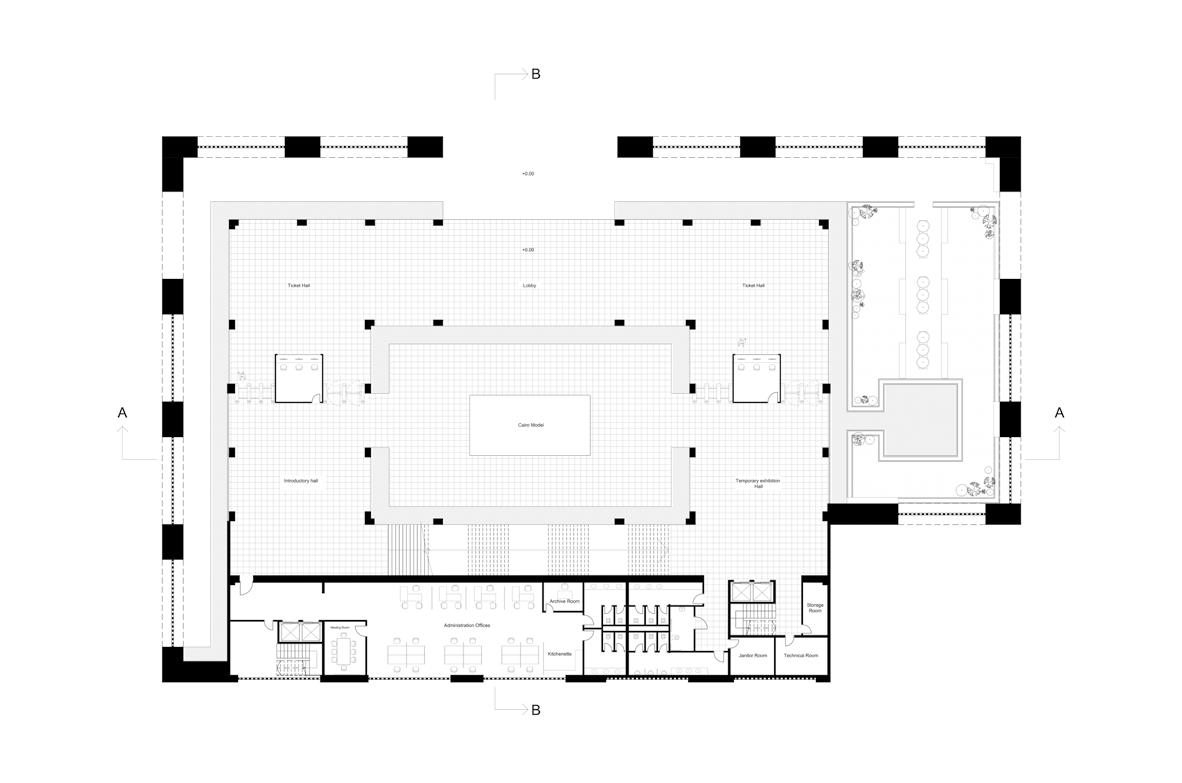

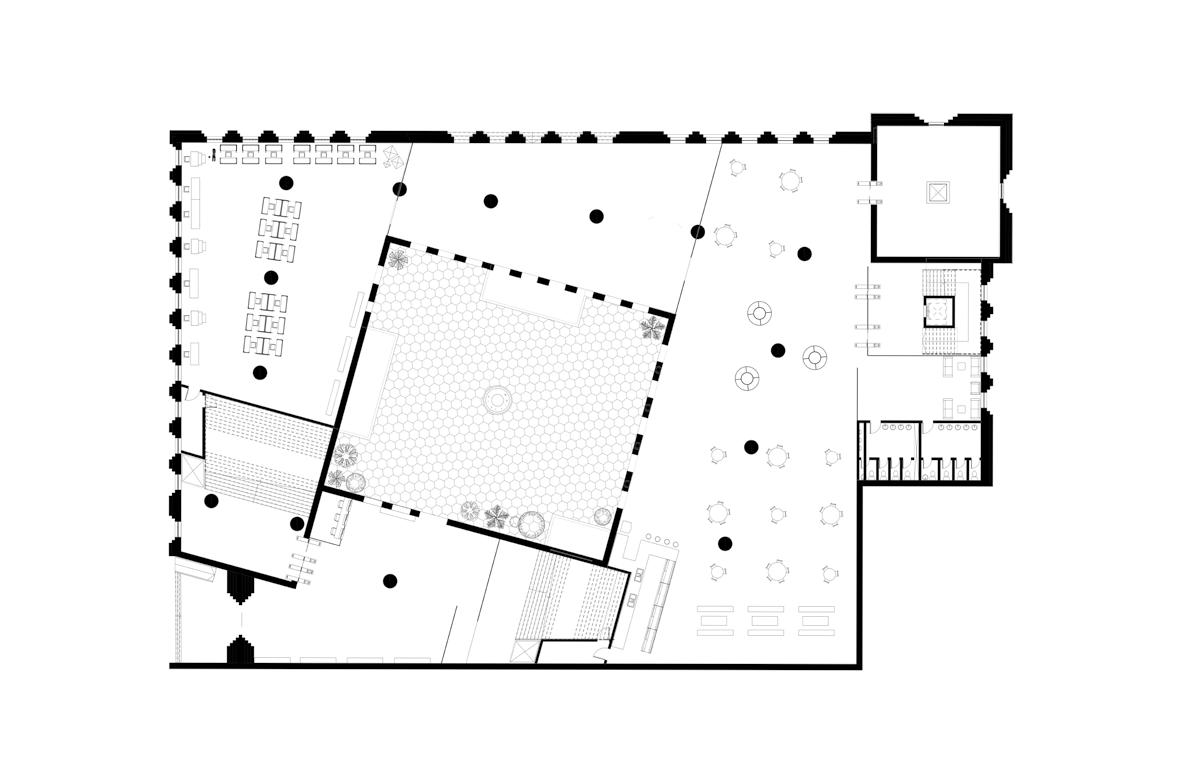

Figure (2) Shown above, the ground floor plan arrangement of interior spaces separated by partition walls, promoting flow and functionality.

Figure (3) Shown on the left page, an interior shot capturing the courtyard’s strong geometric clarity and visual coherence.

Figure (4) Shown above, the facade design and materiality. The choice of stone blends contemporary expression with contextual references.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Nadeen Amged

Students

Roaa Tawfik

Nourhan Abdallah

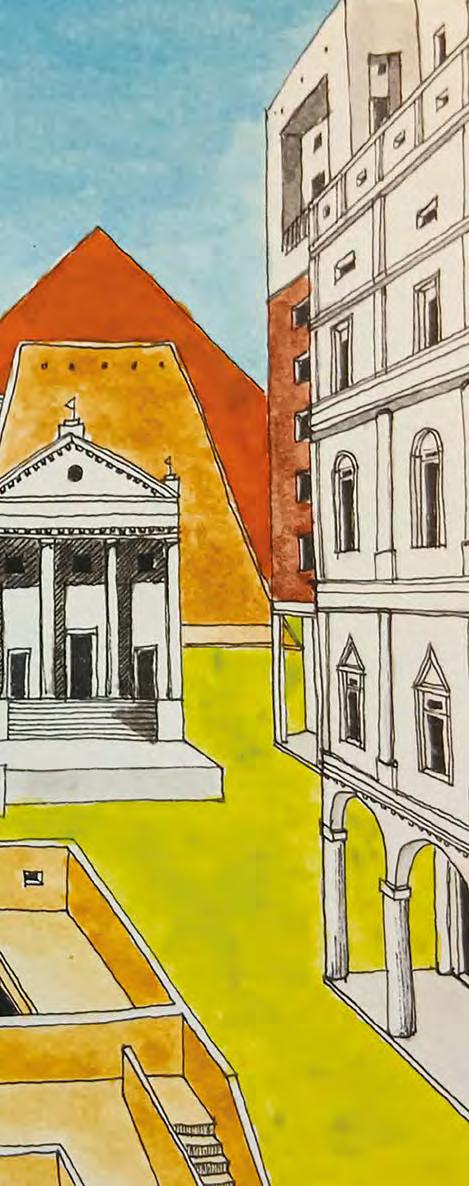

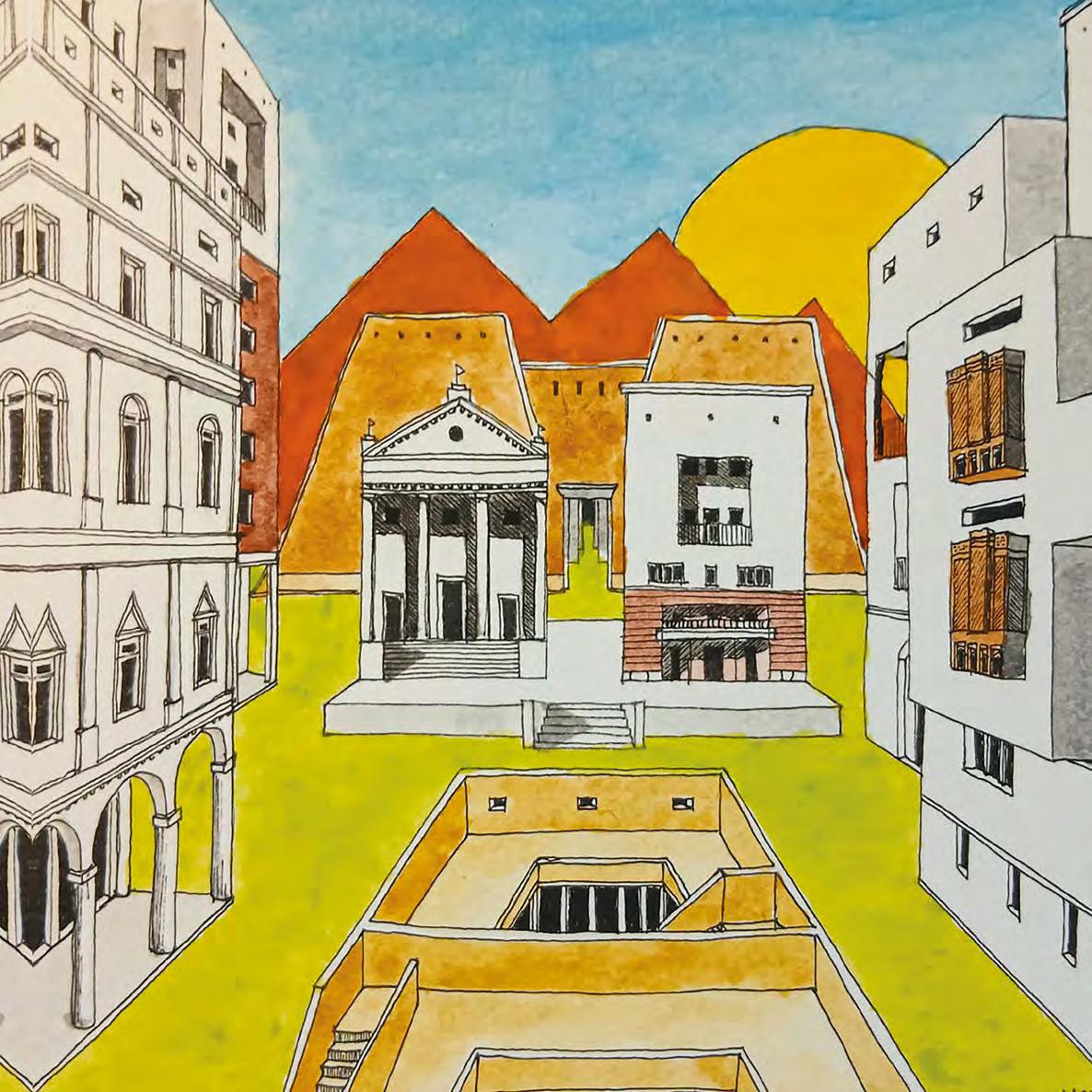

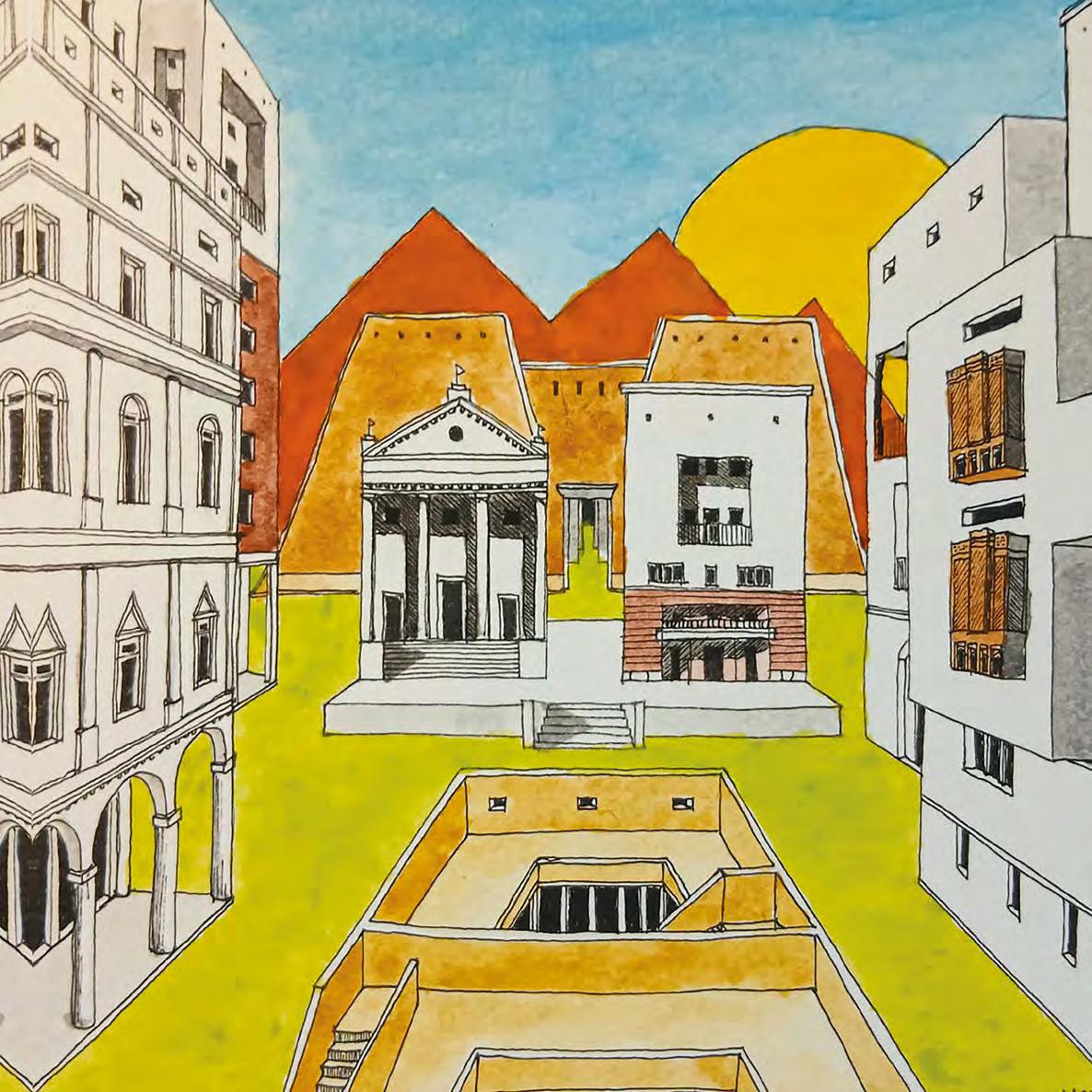

The cultural museum in Old Cairo is designed around the concept of “journeying through time.” It guides visitors through a sequence of contrasting buildings that reflect different historical layers, while also allowing them to engage with Old Cairo as the museum’s living context. The layout centers around a courtyard that acts as a transitional and organizing space, supported by passages inspired by the traditional “Zo’a” found between buildings. These elements create moments of pause and reflection. The museum seamlessly blends movement between interior and exterior spaces, offering a timeless journey through the rich architectural and cultural heritage of Old Cairo.

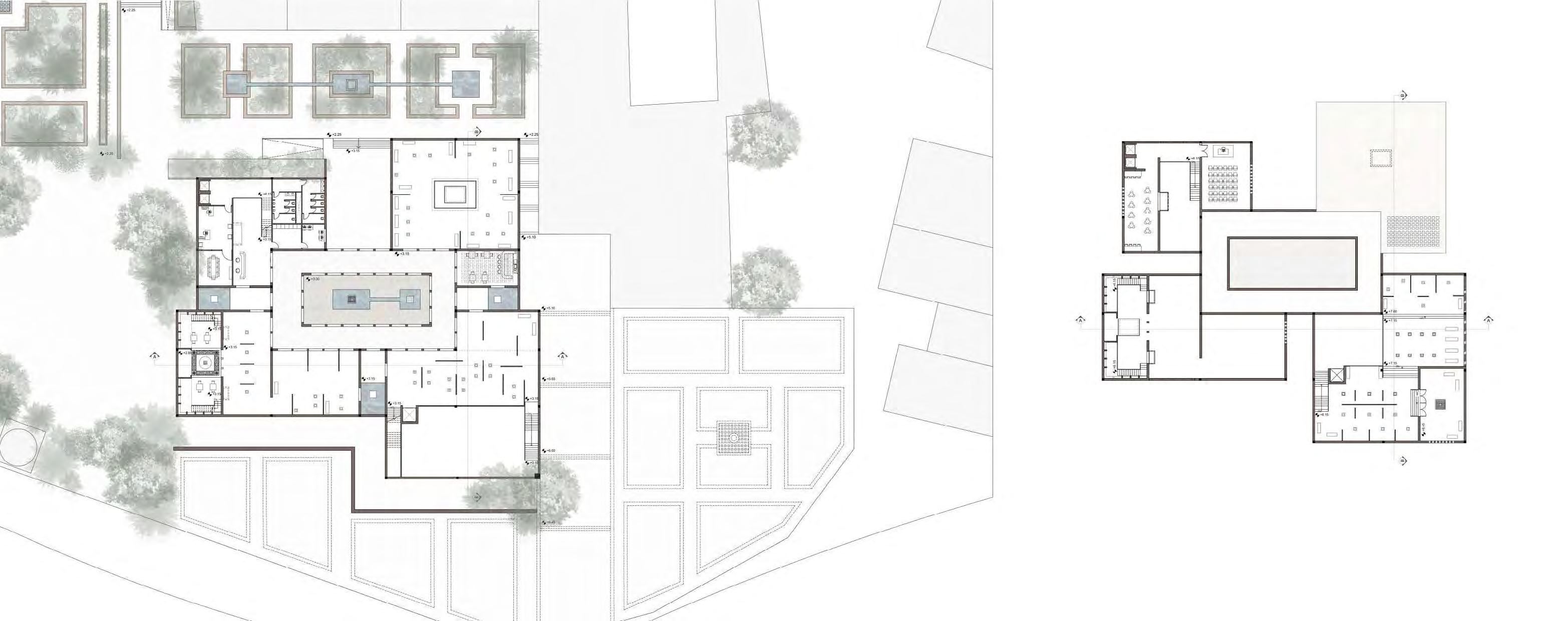

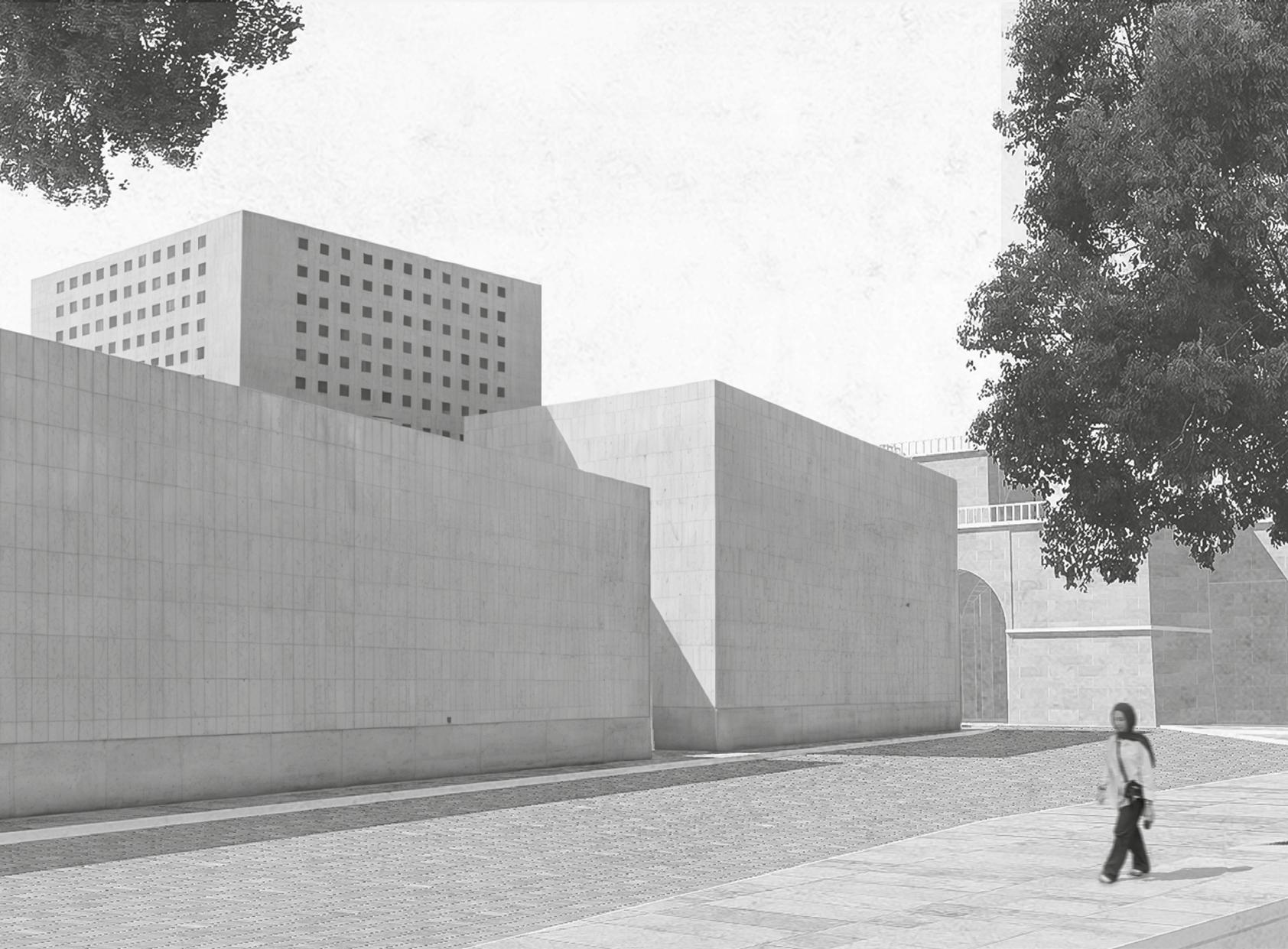

Figure (1) Shown on the left page, the site plan of the museum neighbourining Manzil Ali Labib, emphasizing the relation between the two public buildings.

Figure (2) Shown above, the programmatic zones, clearly defined and integrated. The courtyard typology invites engagement and interaction within the ground floor level.

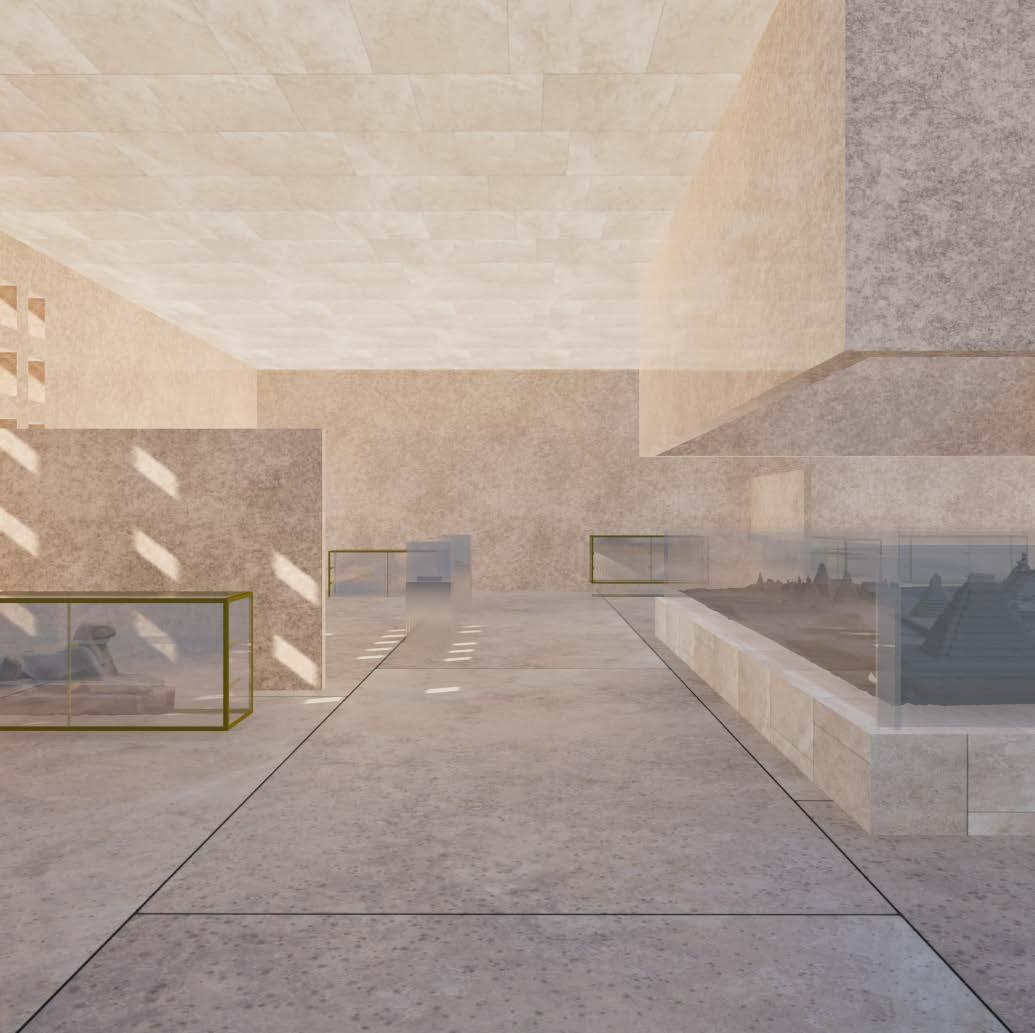

Figure (3) Shown on the left page, the exhibition space communicating the materials contextualizing the museum of Cairo and supporting an uninterrupted journey.

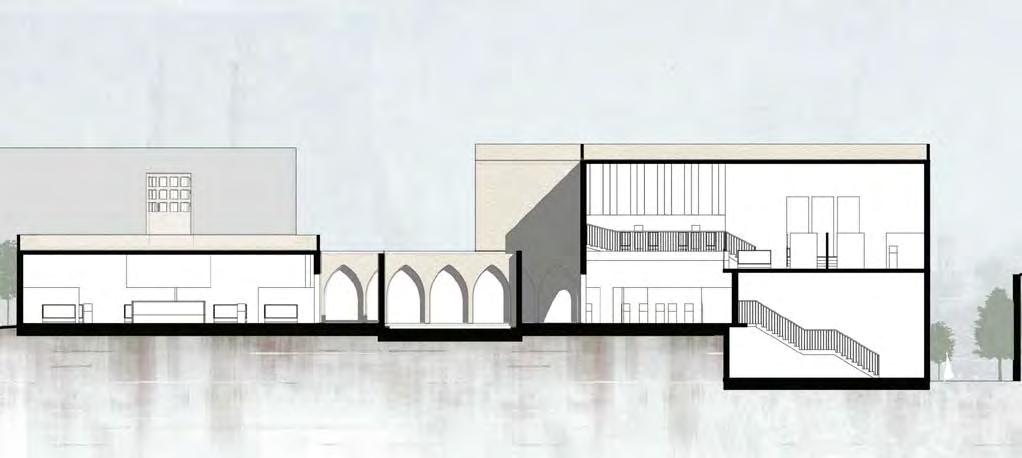

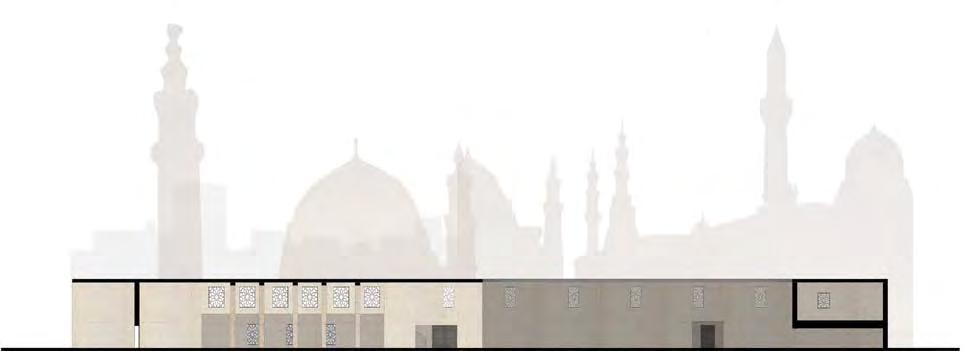

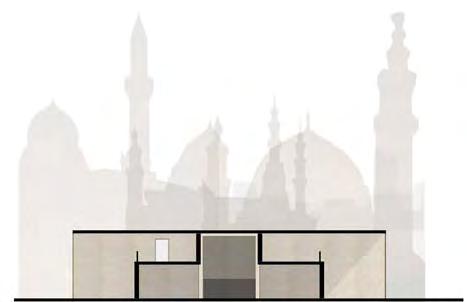

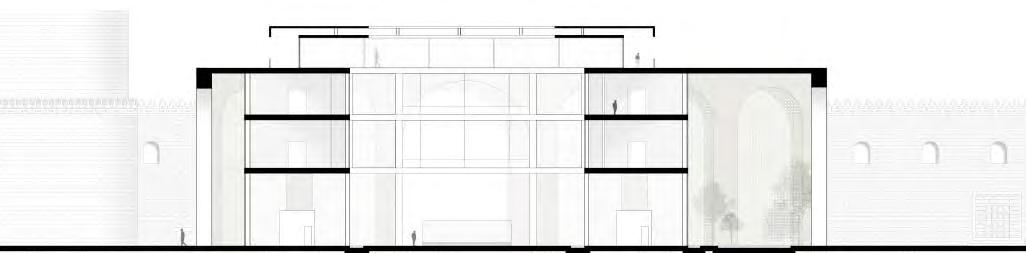

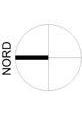

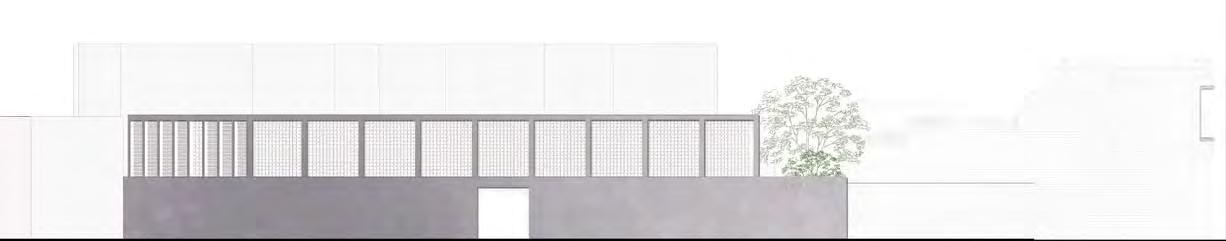

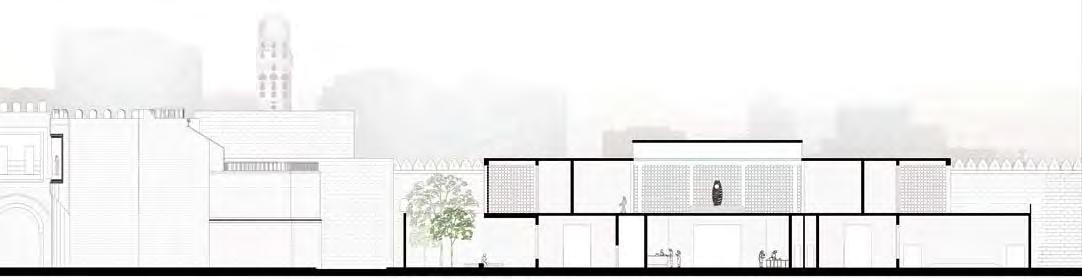

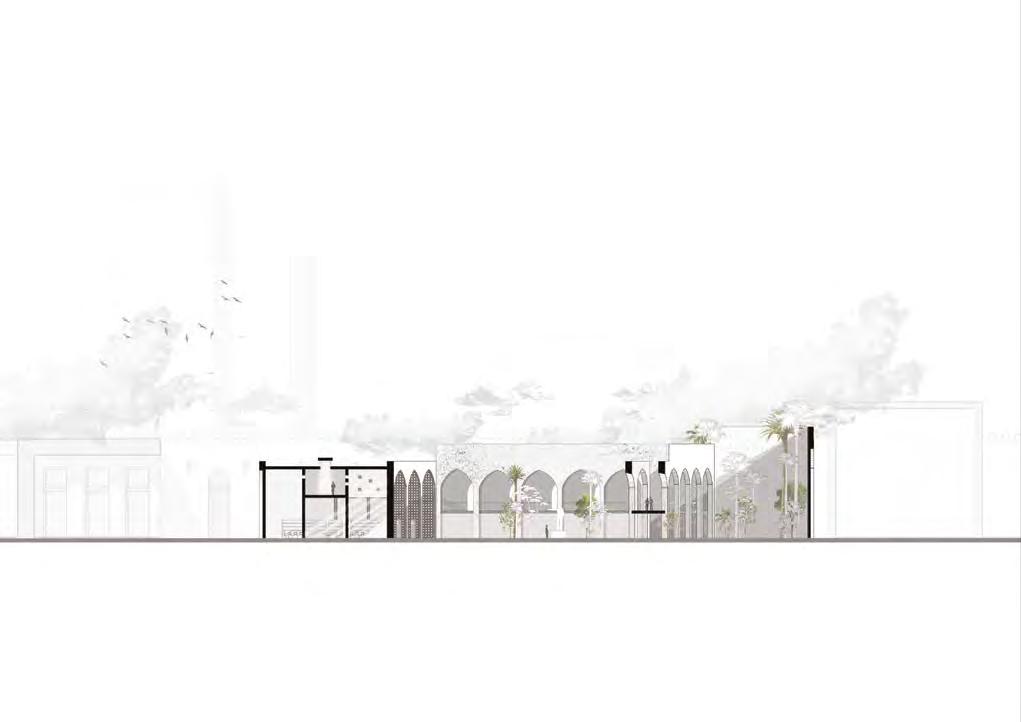

Figure (4) Shown above, the main elevation and section, demonstrating the interconnection between the masses and the courtyard.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Nadeen Amged

Students

Habiba Riad Salma Hefnawi

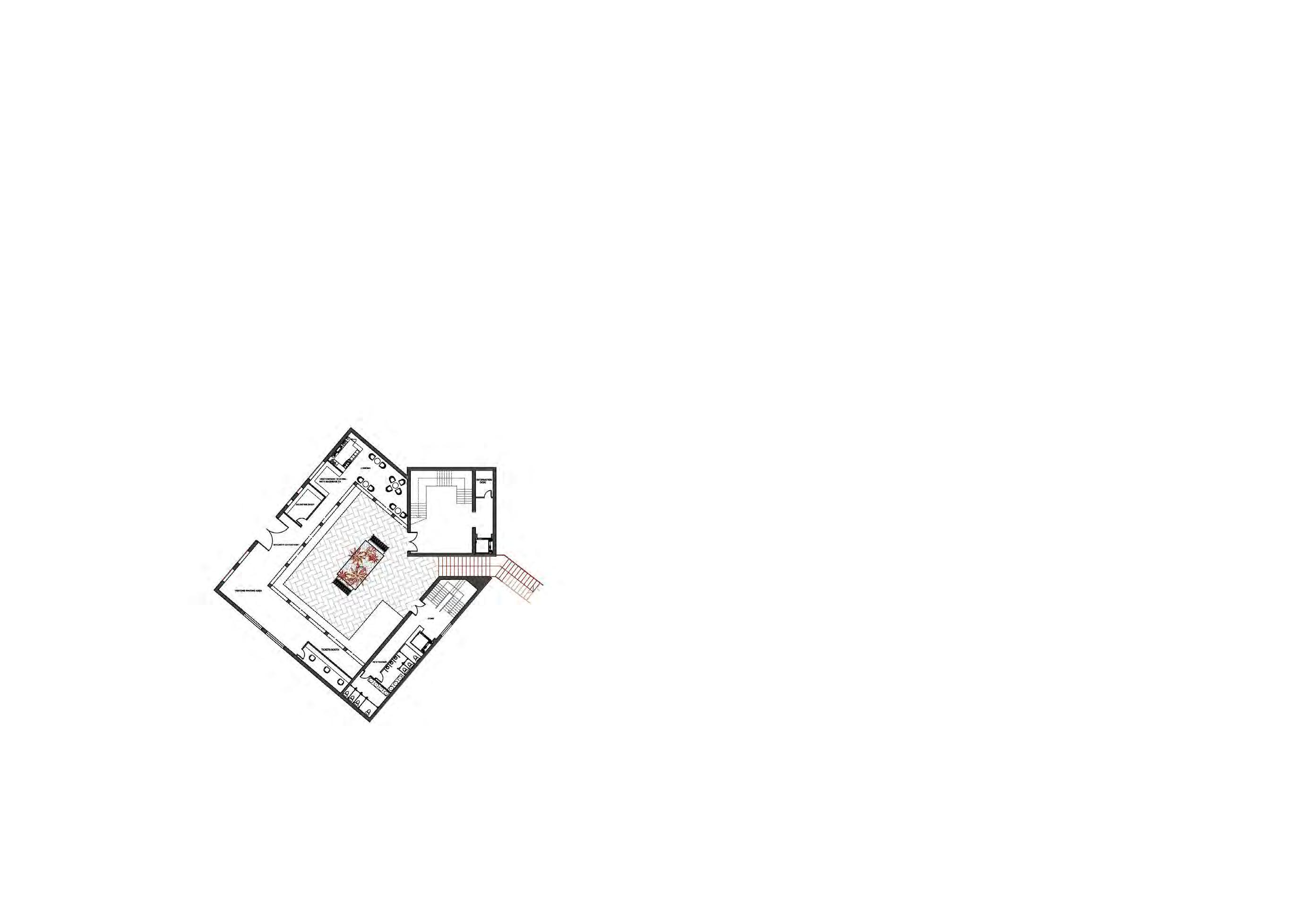

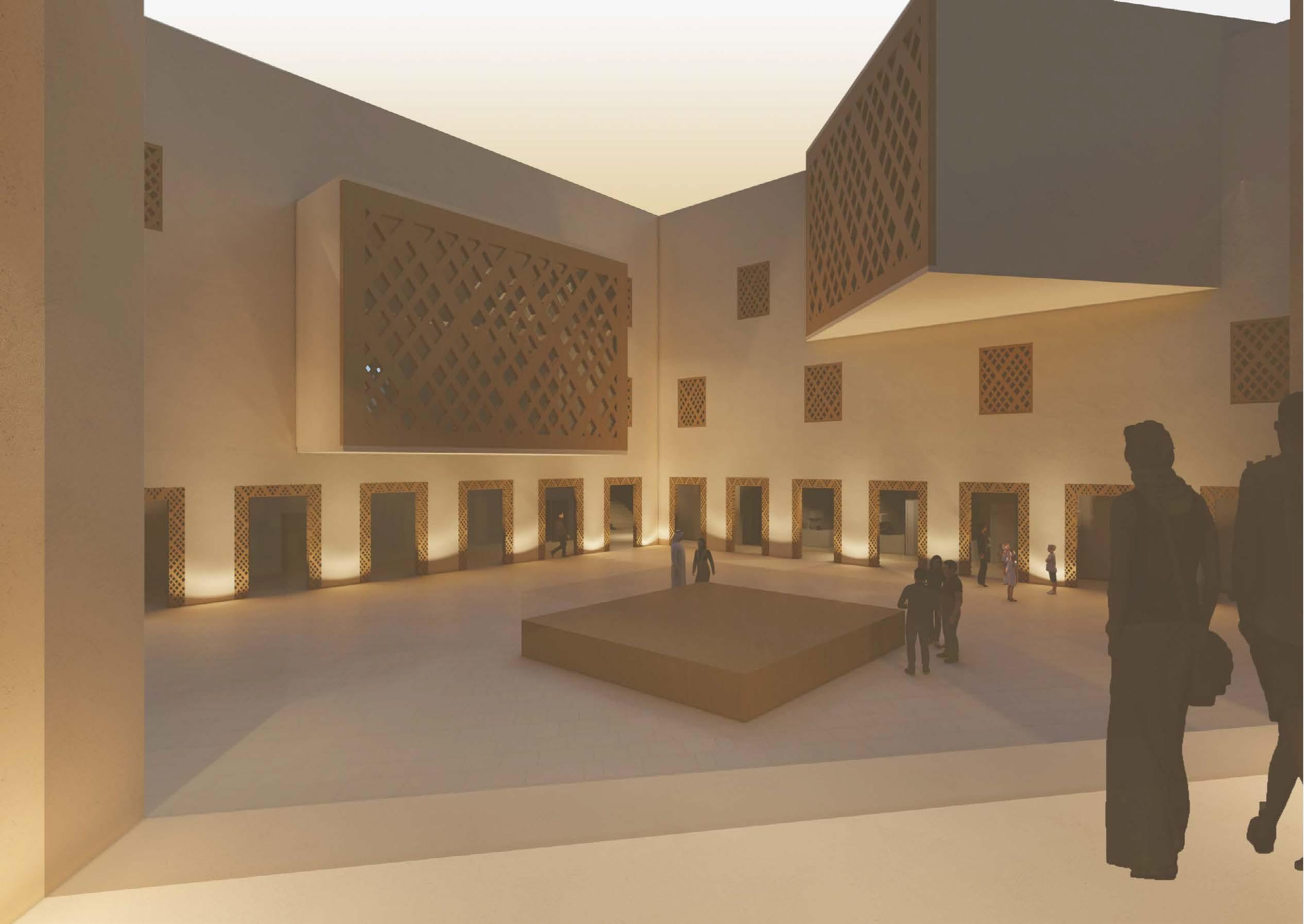

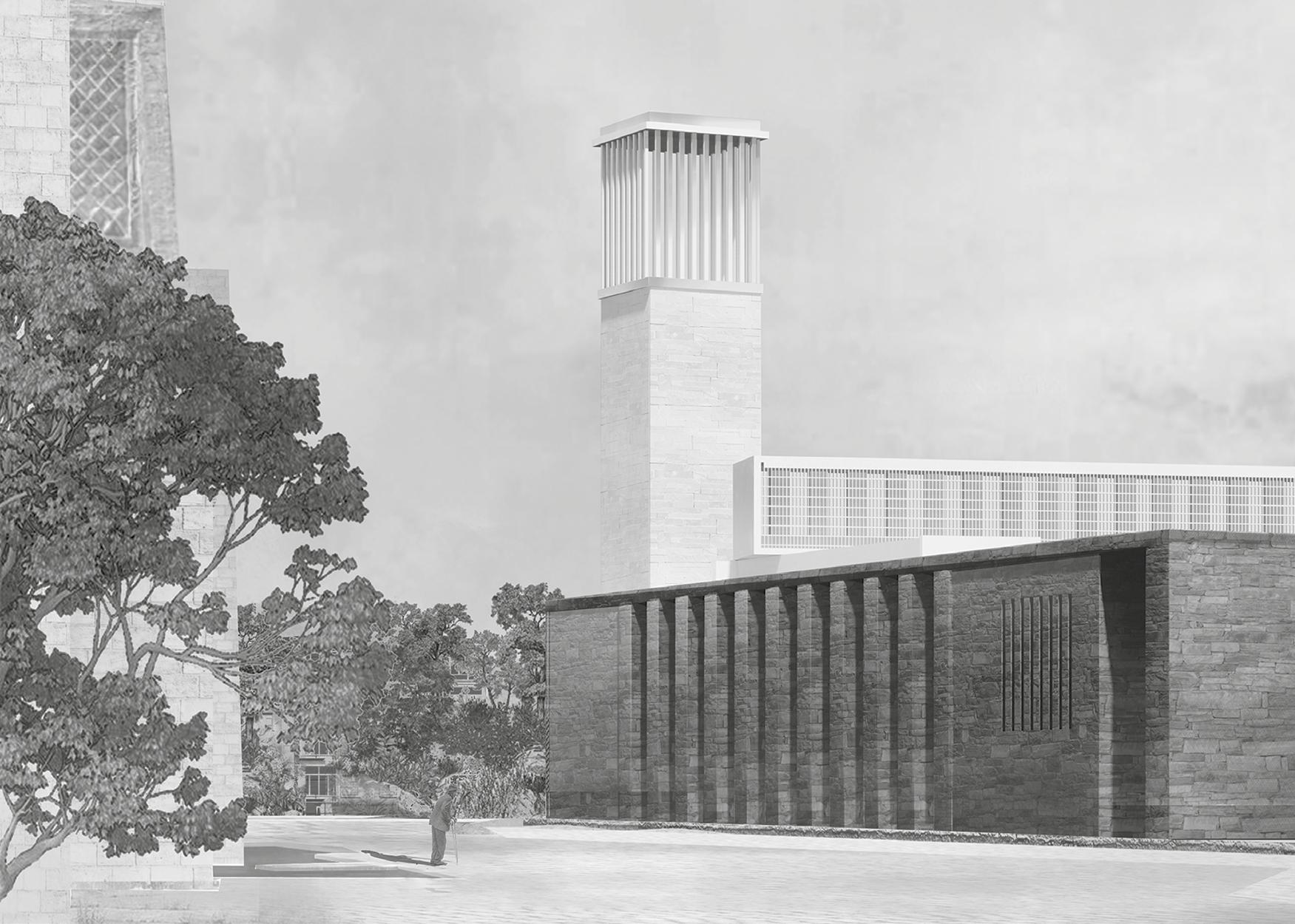

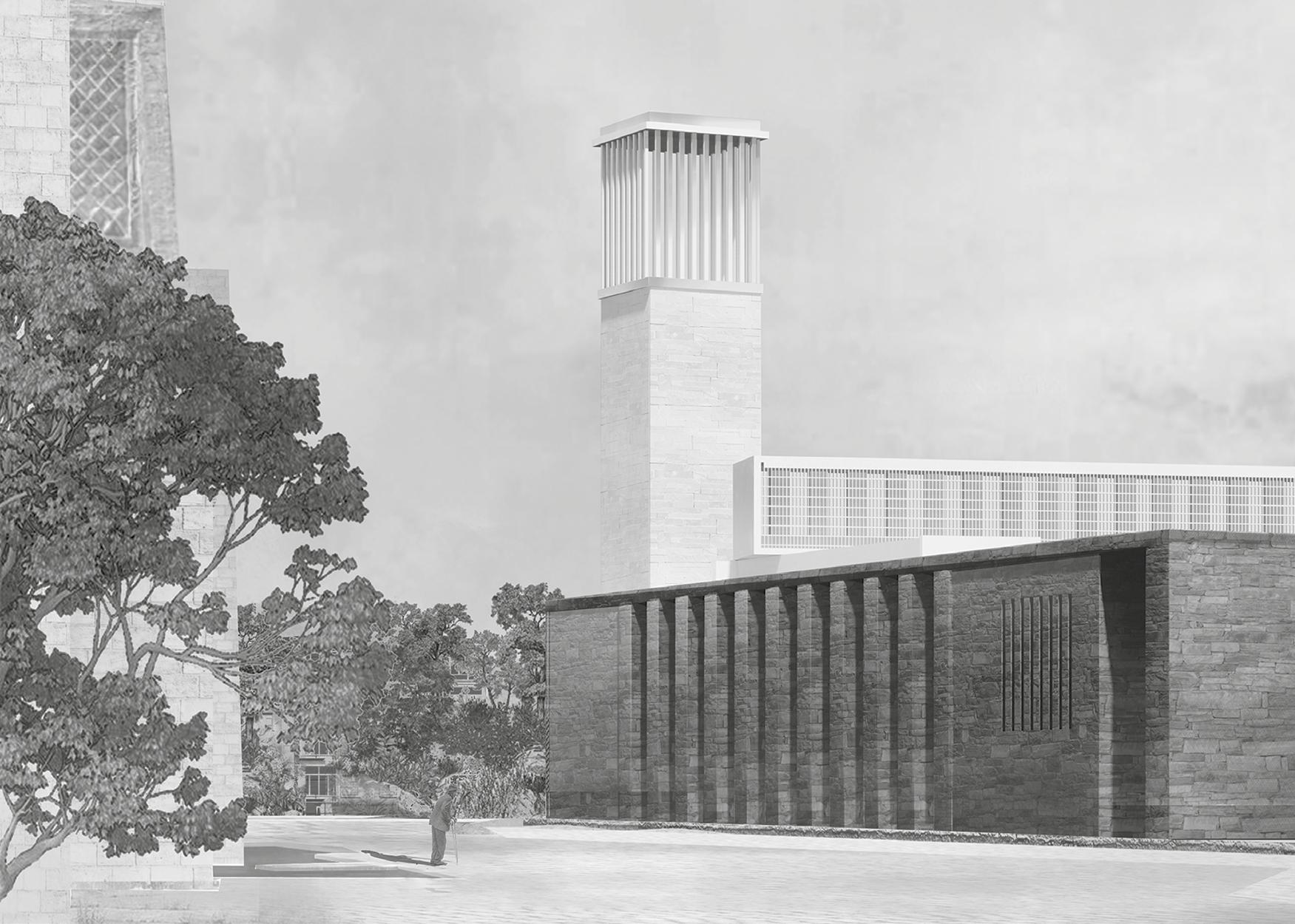

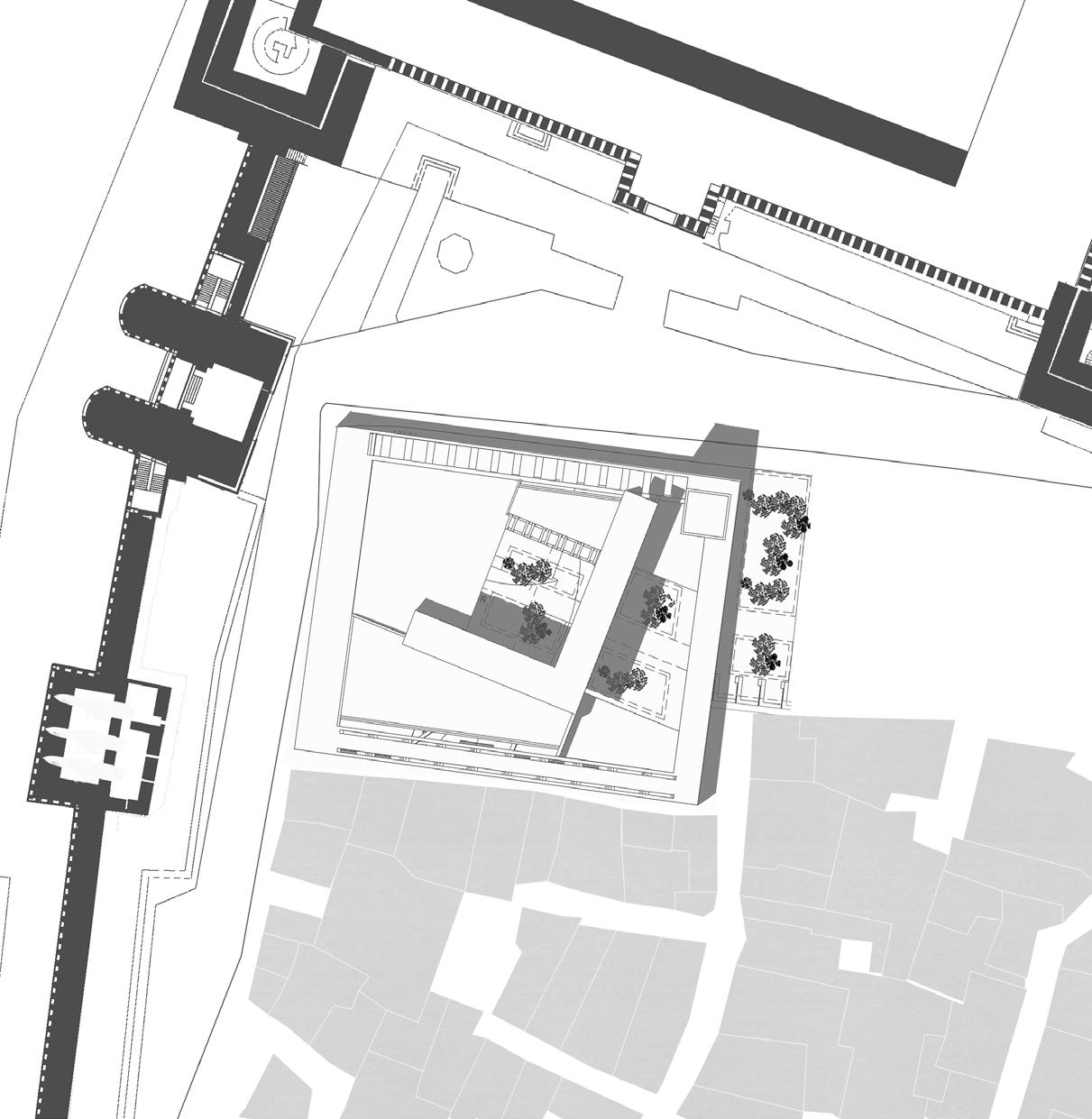

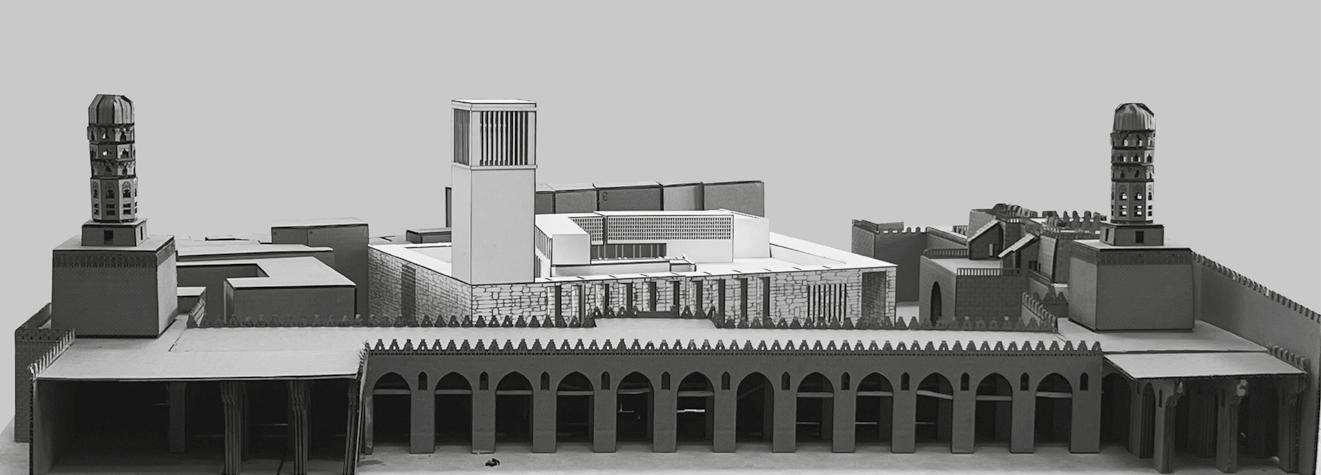

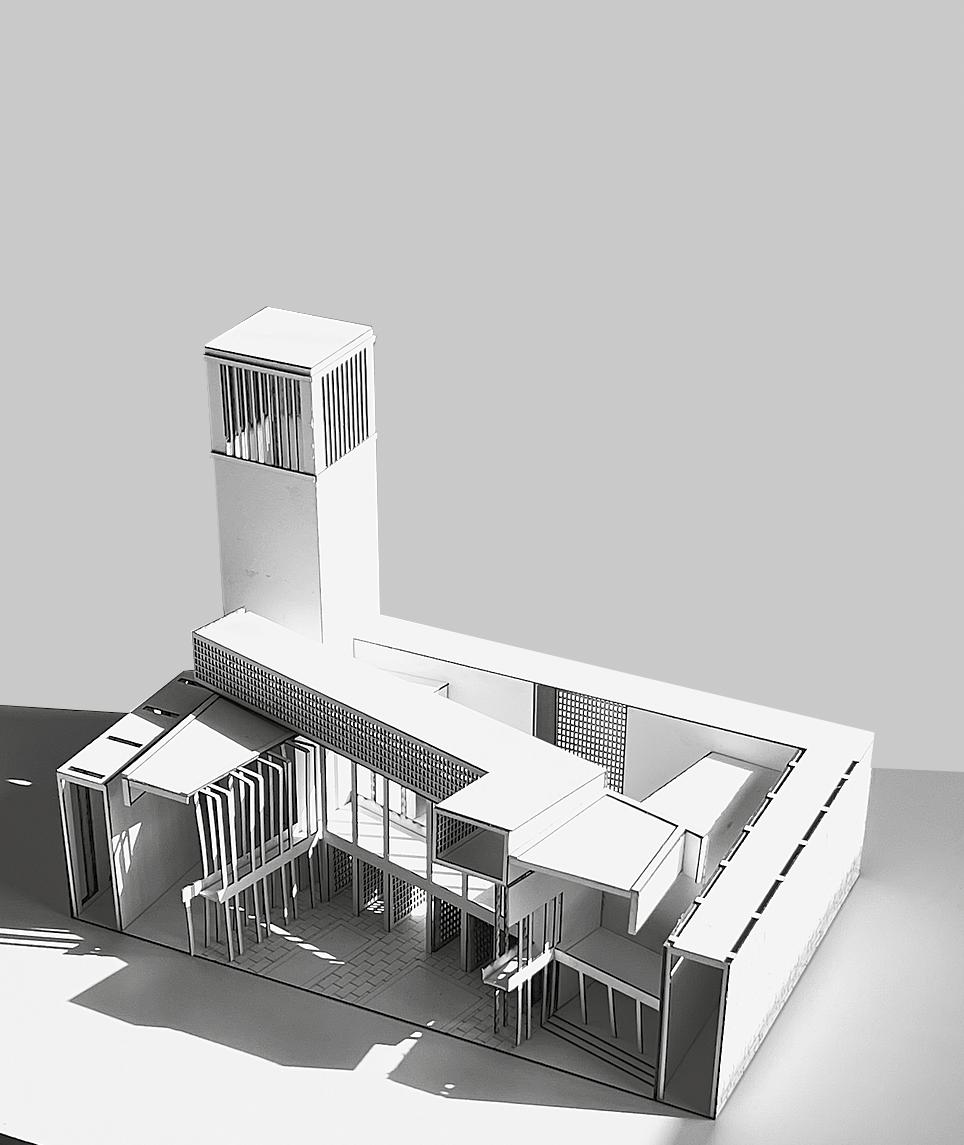

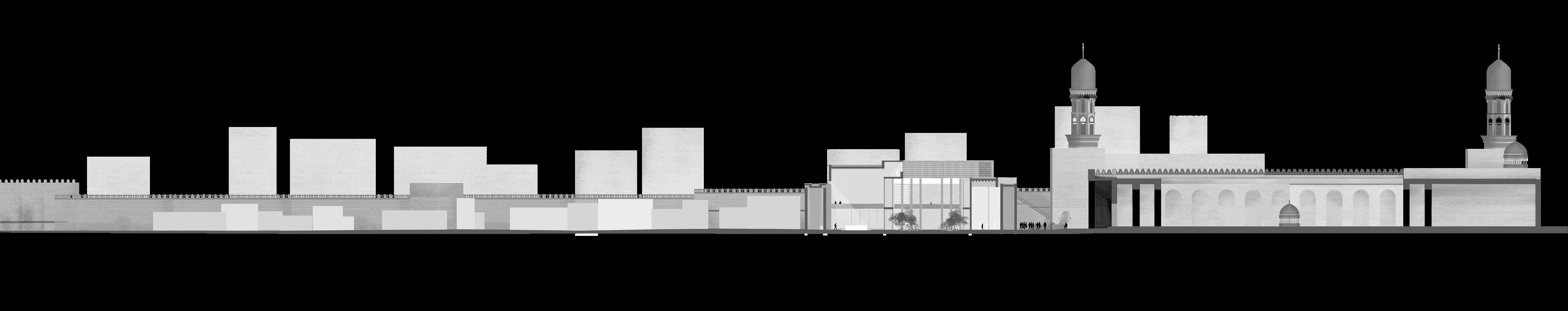

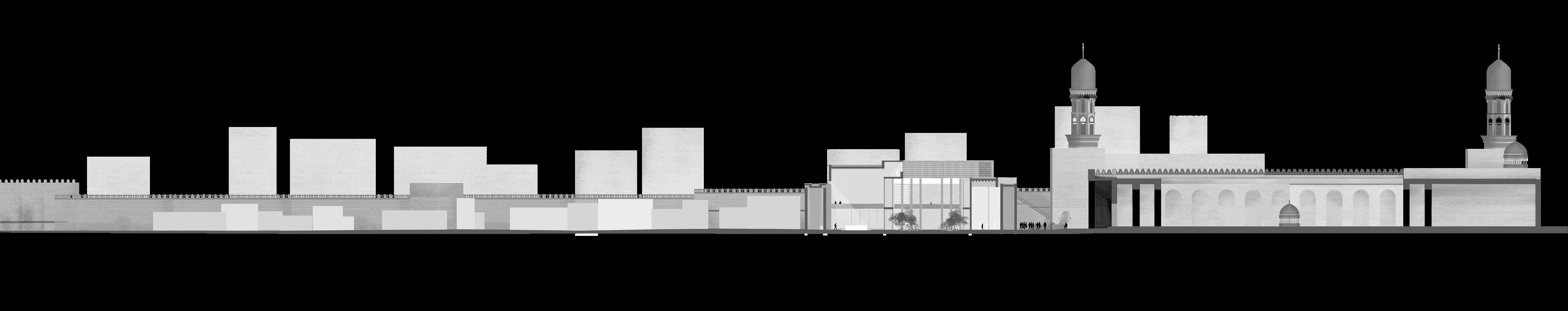

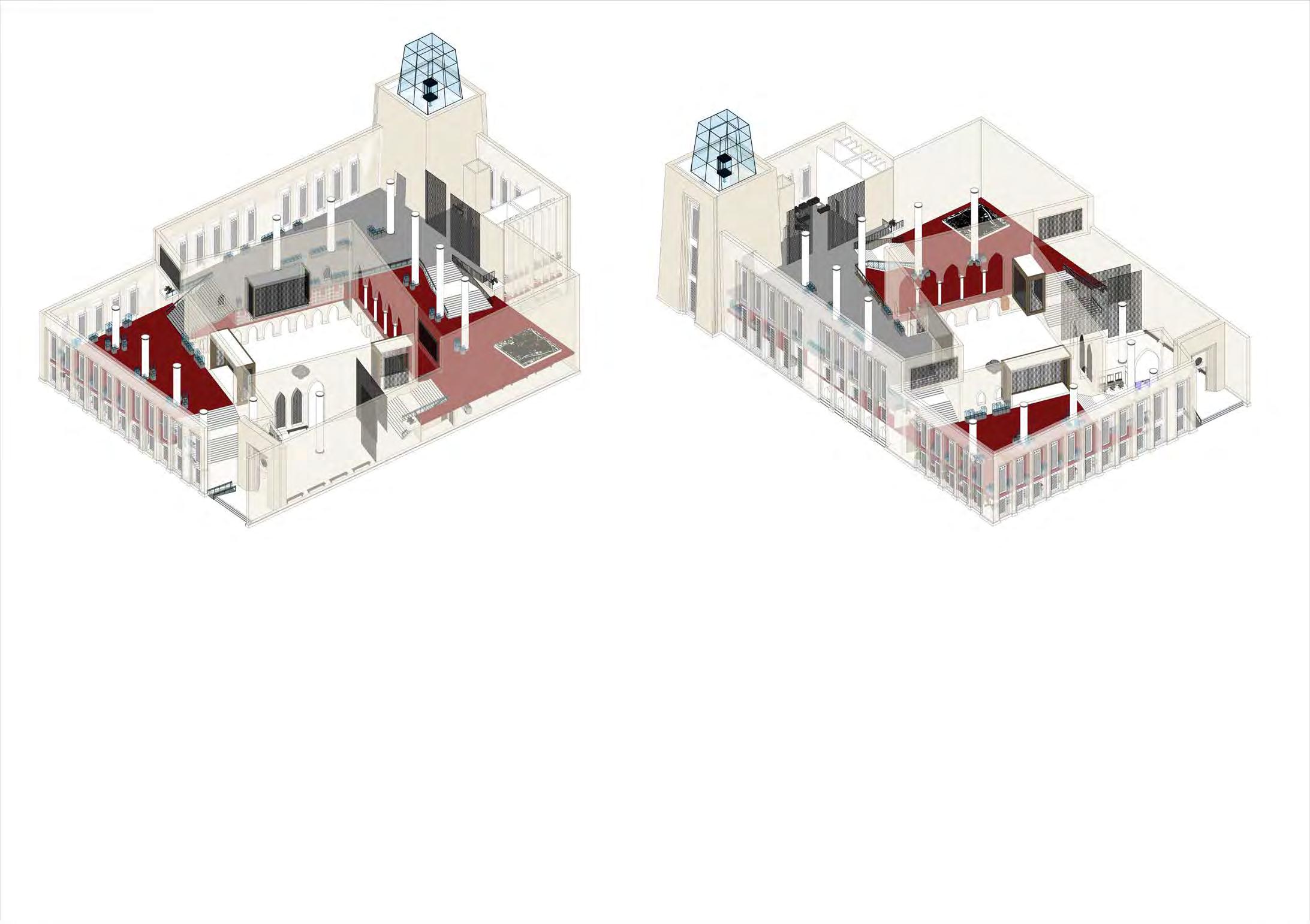

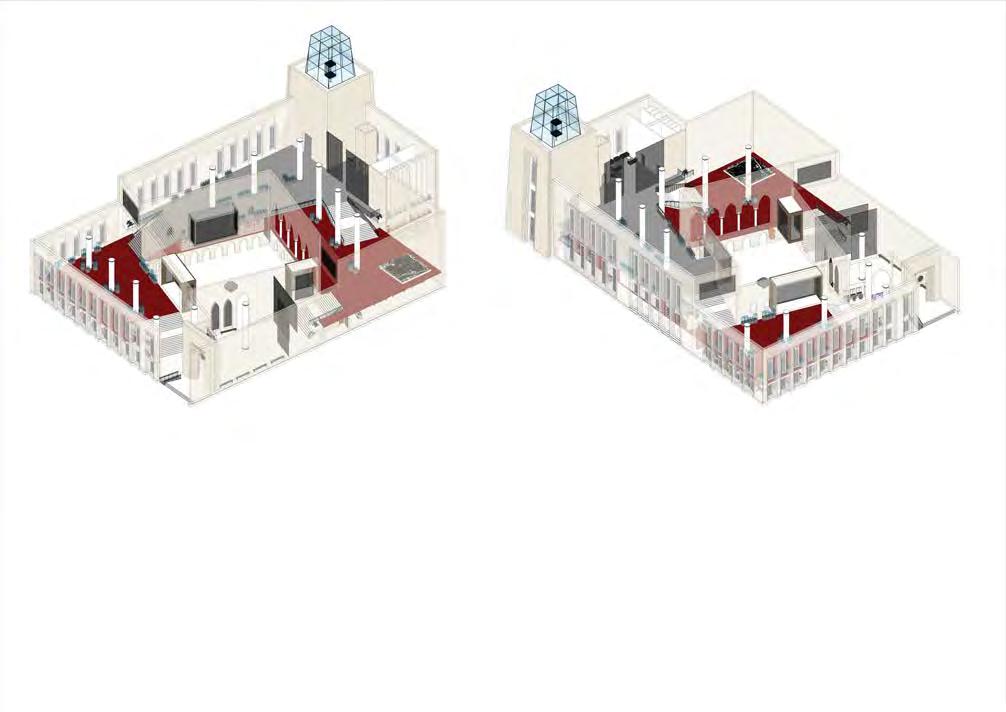

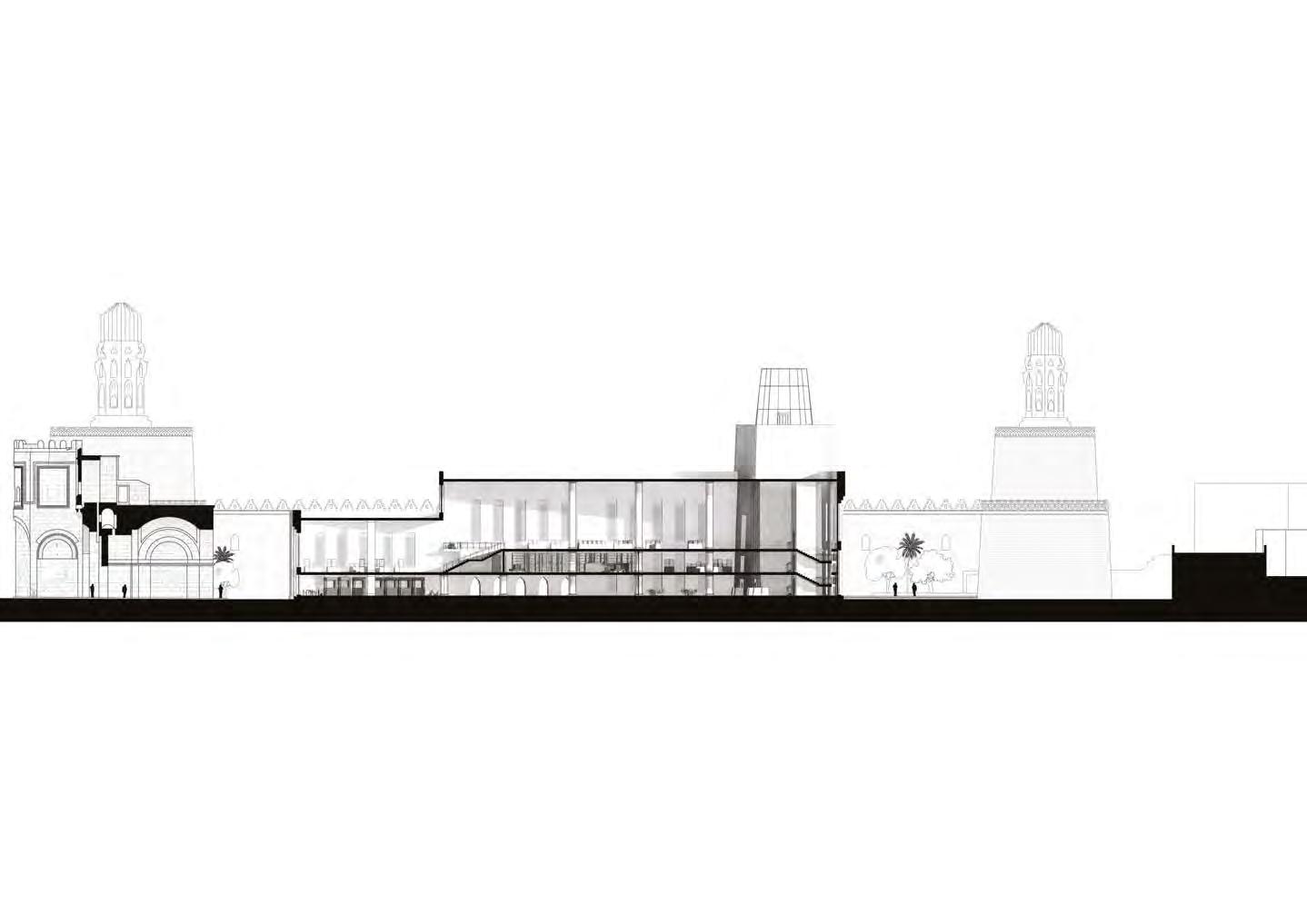

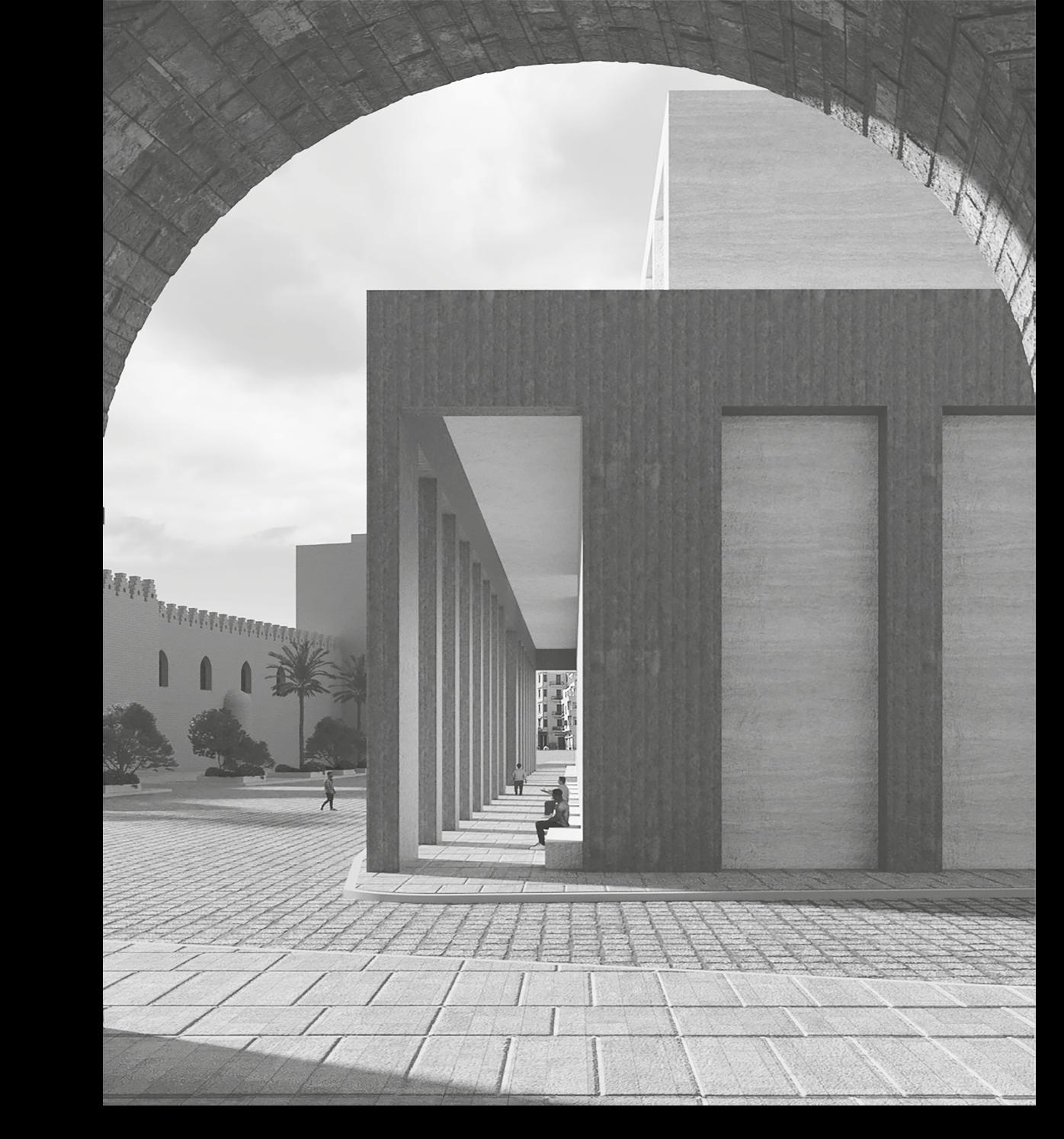

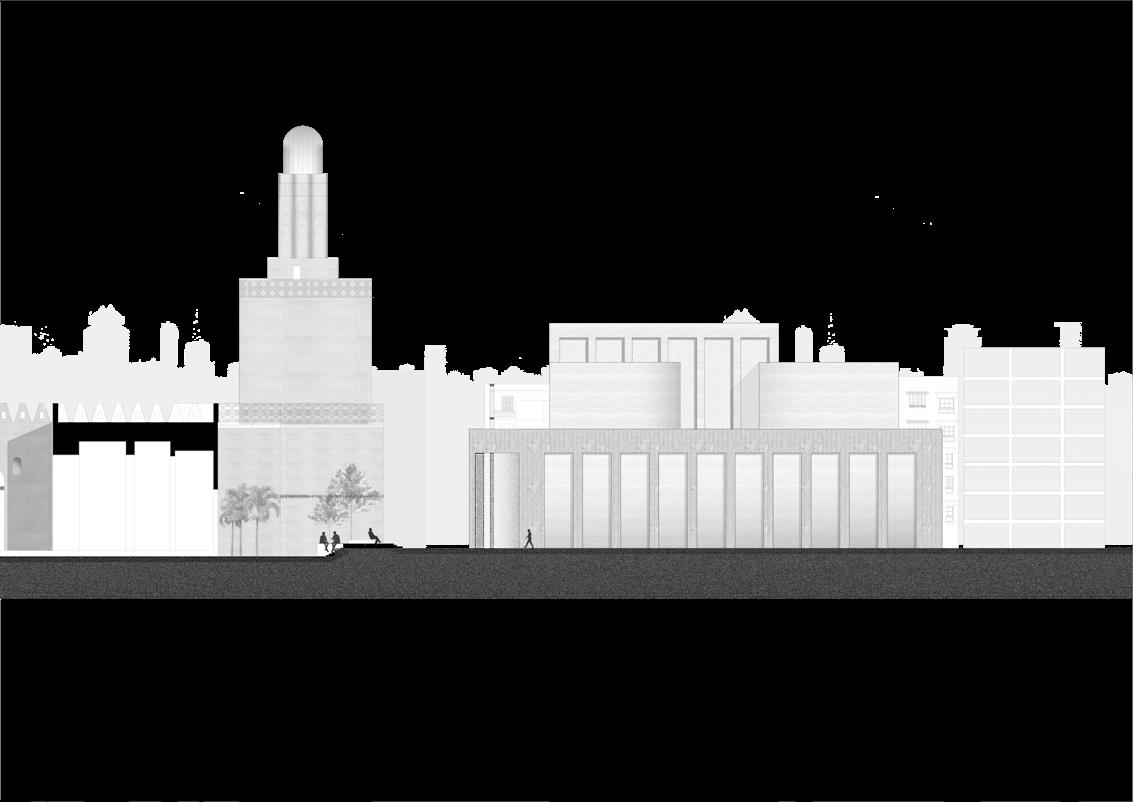

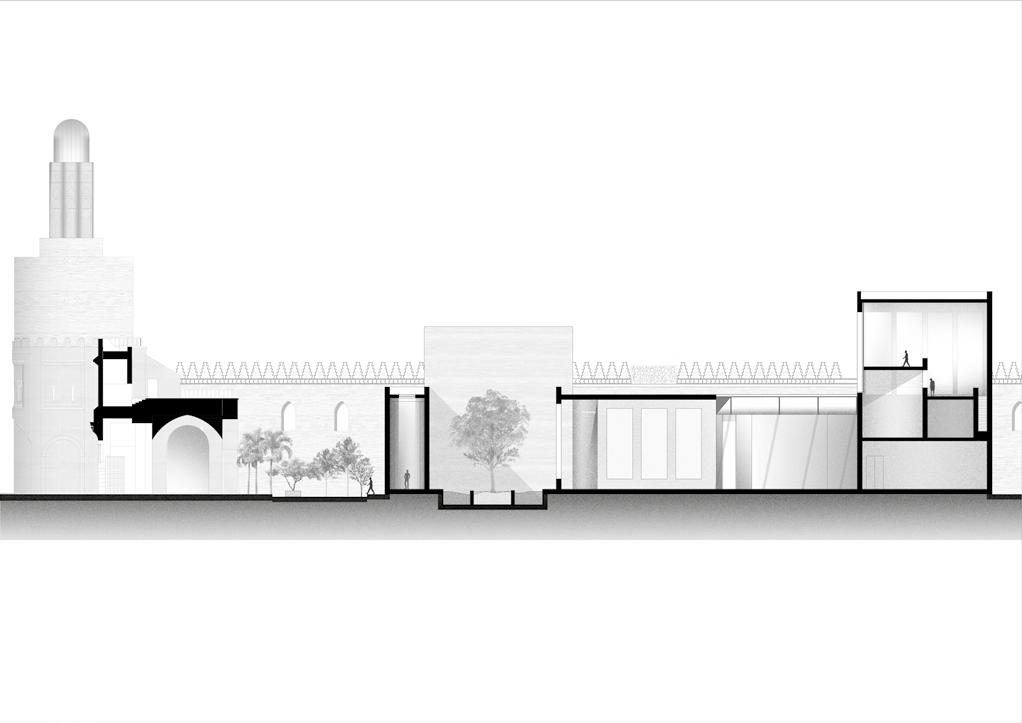

Located in Islamic Cairo, facing Aly Labib House with a dominant view of the Citadel, this museum showcases the history of Old Cairo. The design consists of two courtyard buildings positioned at different topographic levels, connected through a central malqaf-shaped tower. The lower courtyard serves as a semi-public space with common functions, leading visitors through the malqaf tower to the upper courtyard, where the main exhibition unfolds as a journey through Islamic Cairo’s history. Featuring elements like a Mashrabiya Hall and a panoramic rooftop view, the design integrates traditional Islamic architecture to harmonize with the site’s topography.

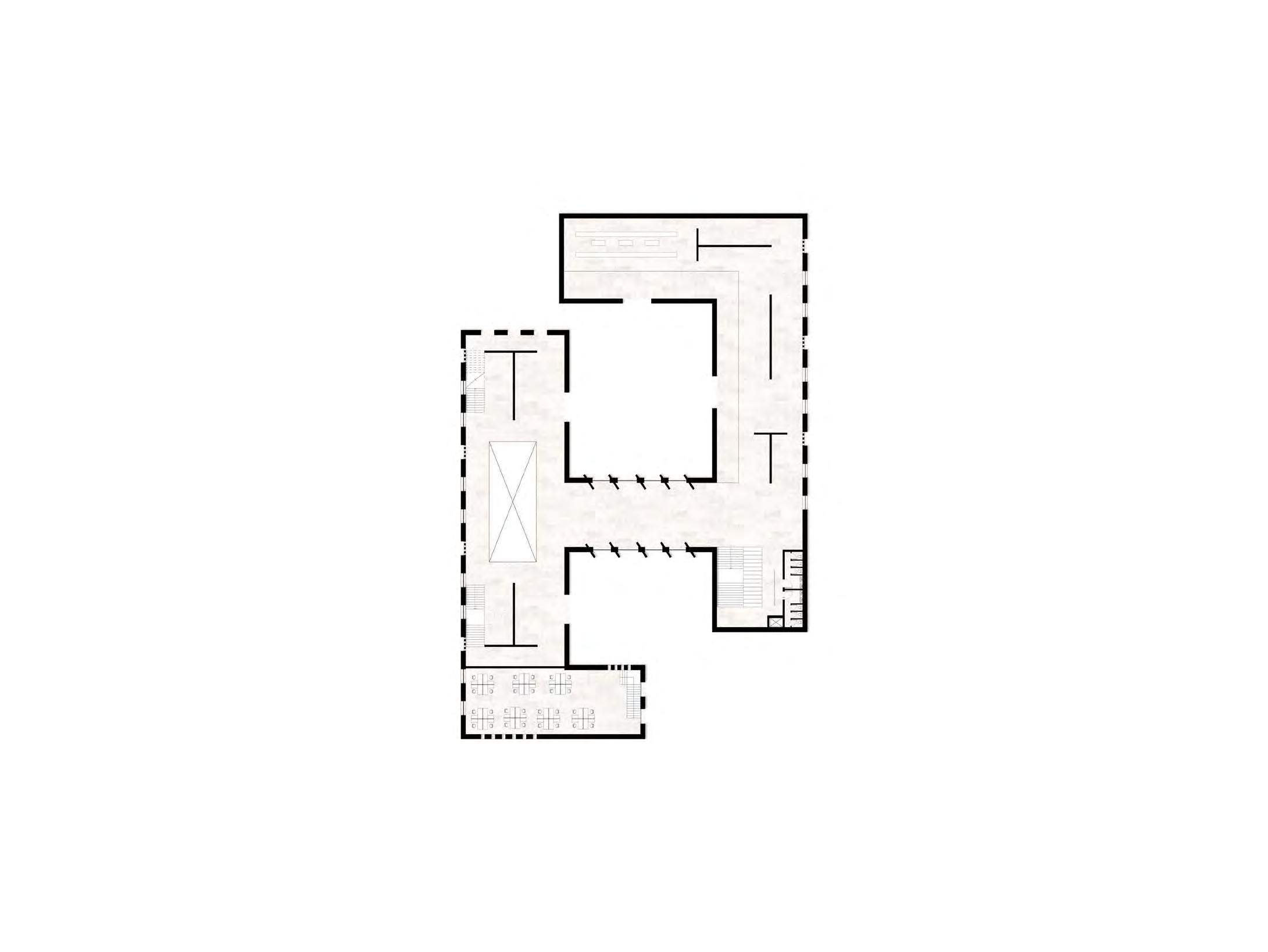

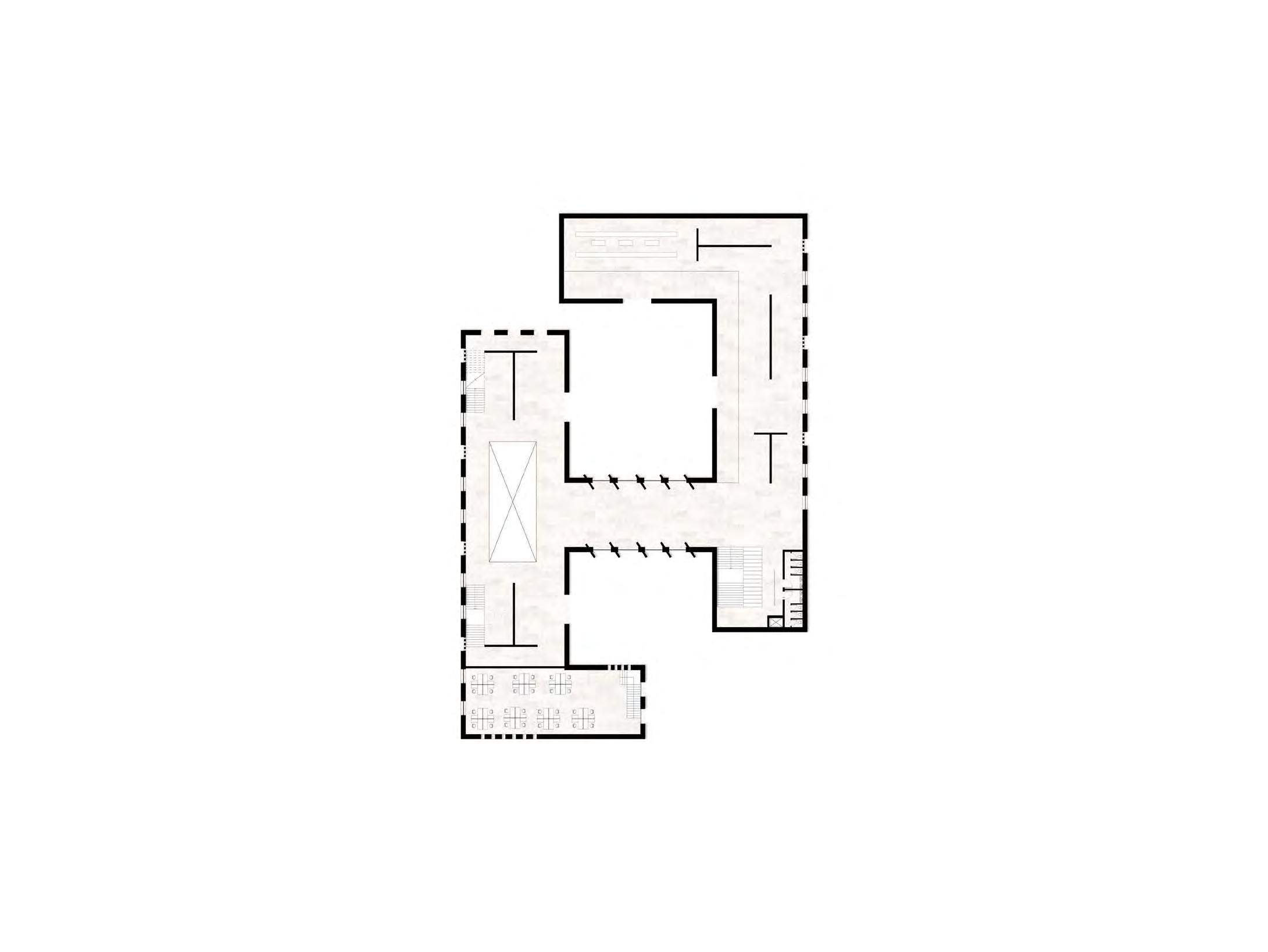

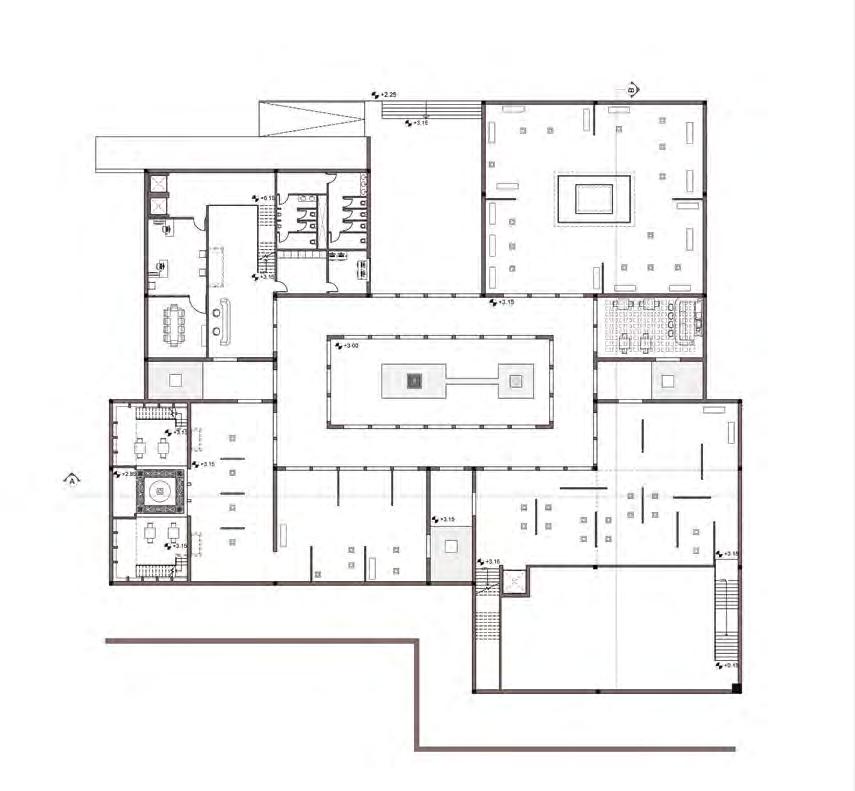

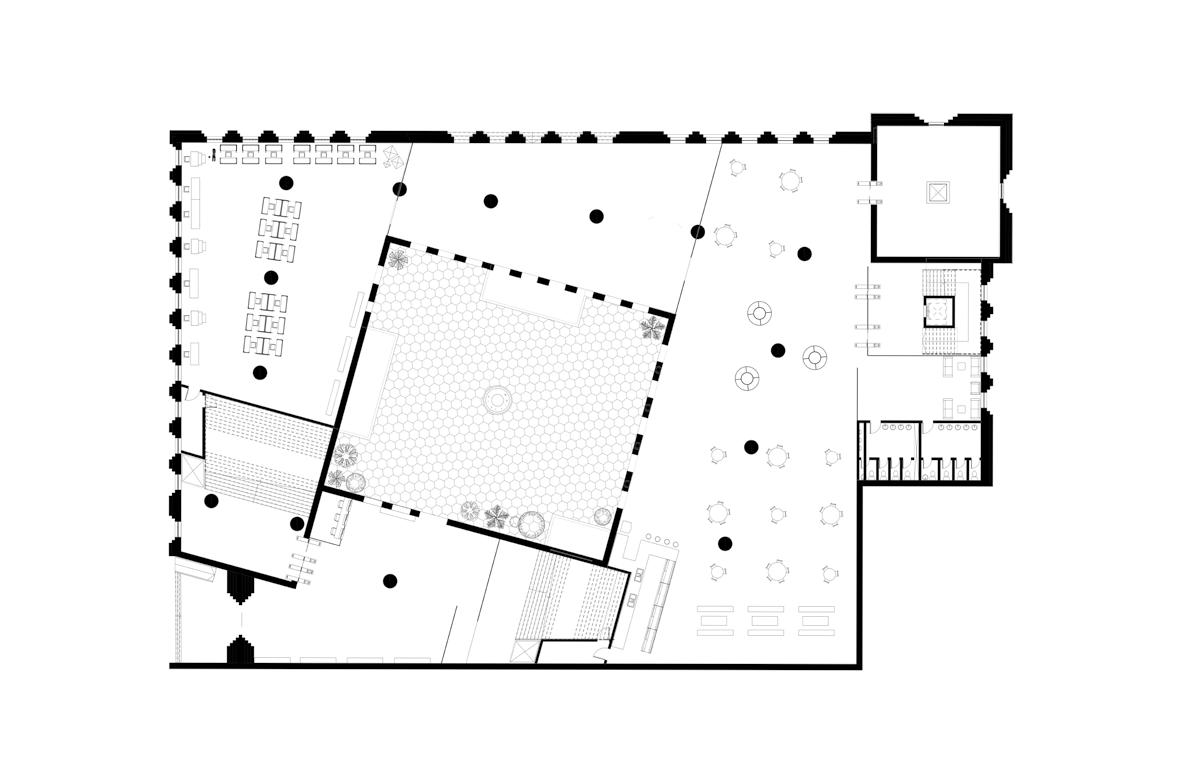

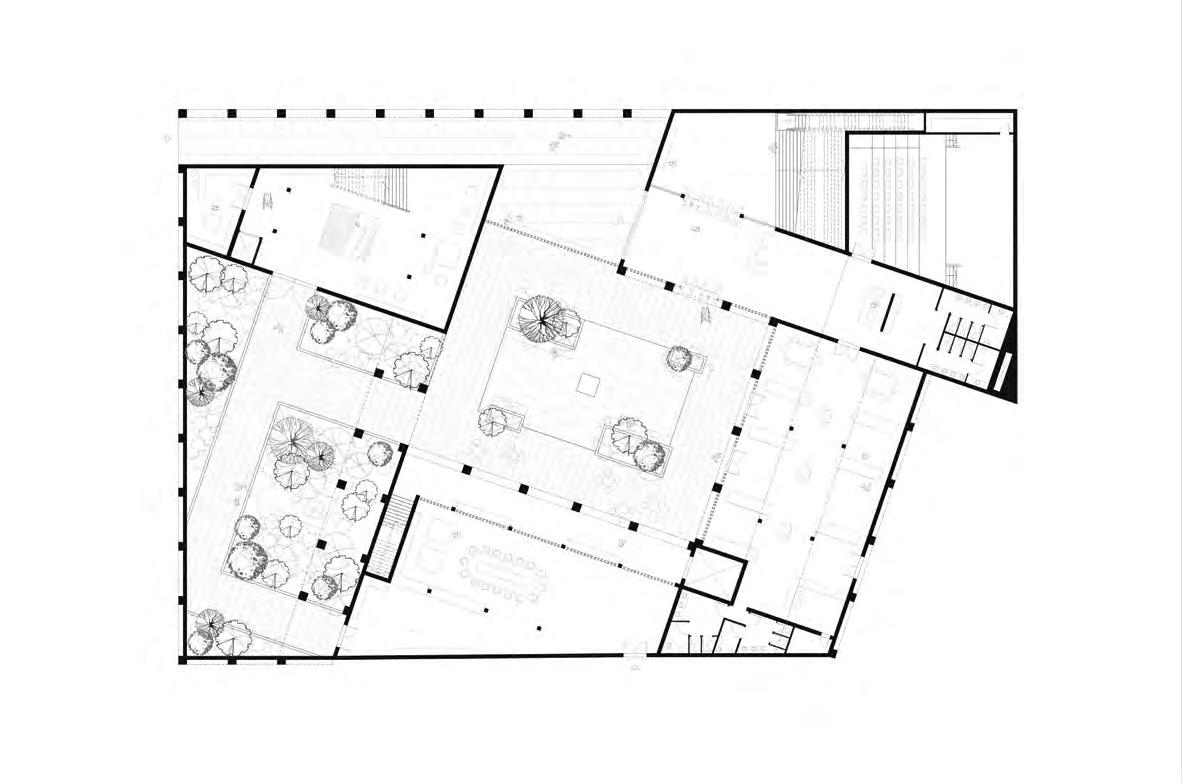

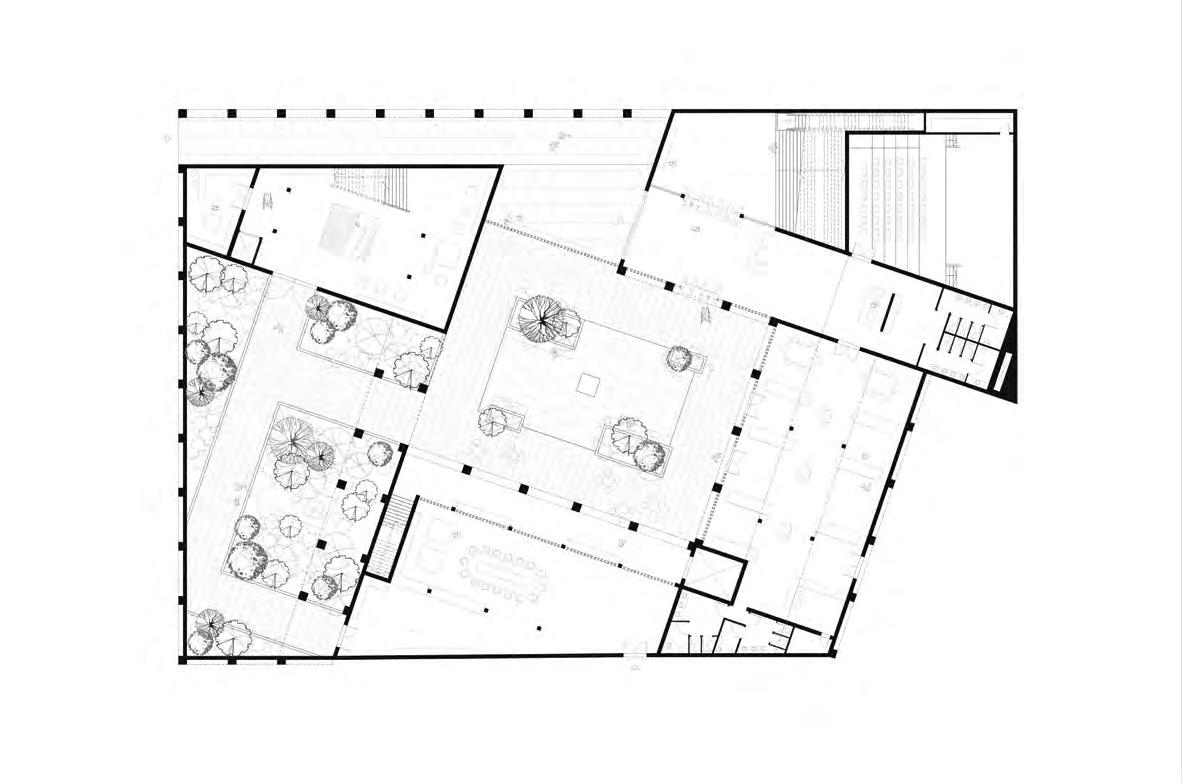

Figure (1) Shown on the left page, the site plan showing the building in relation to the surroundings and the two courtyards placed on two different levels

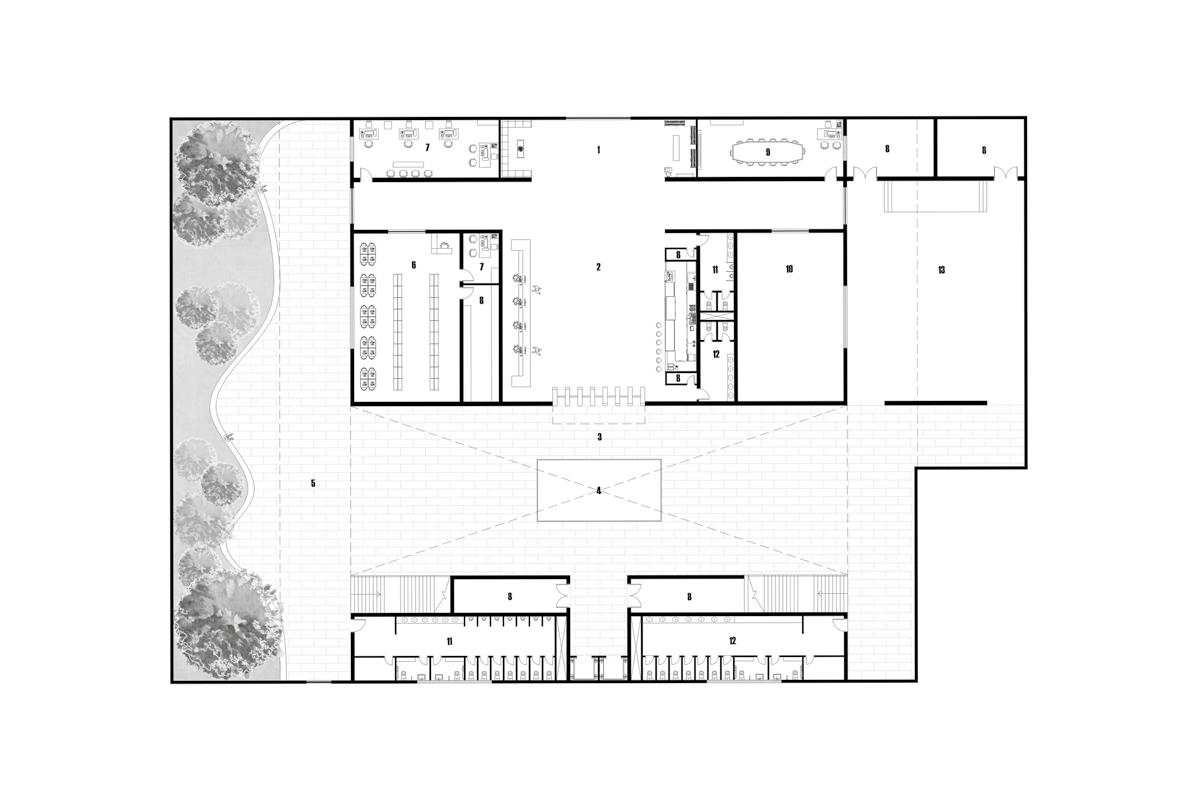

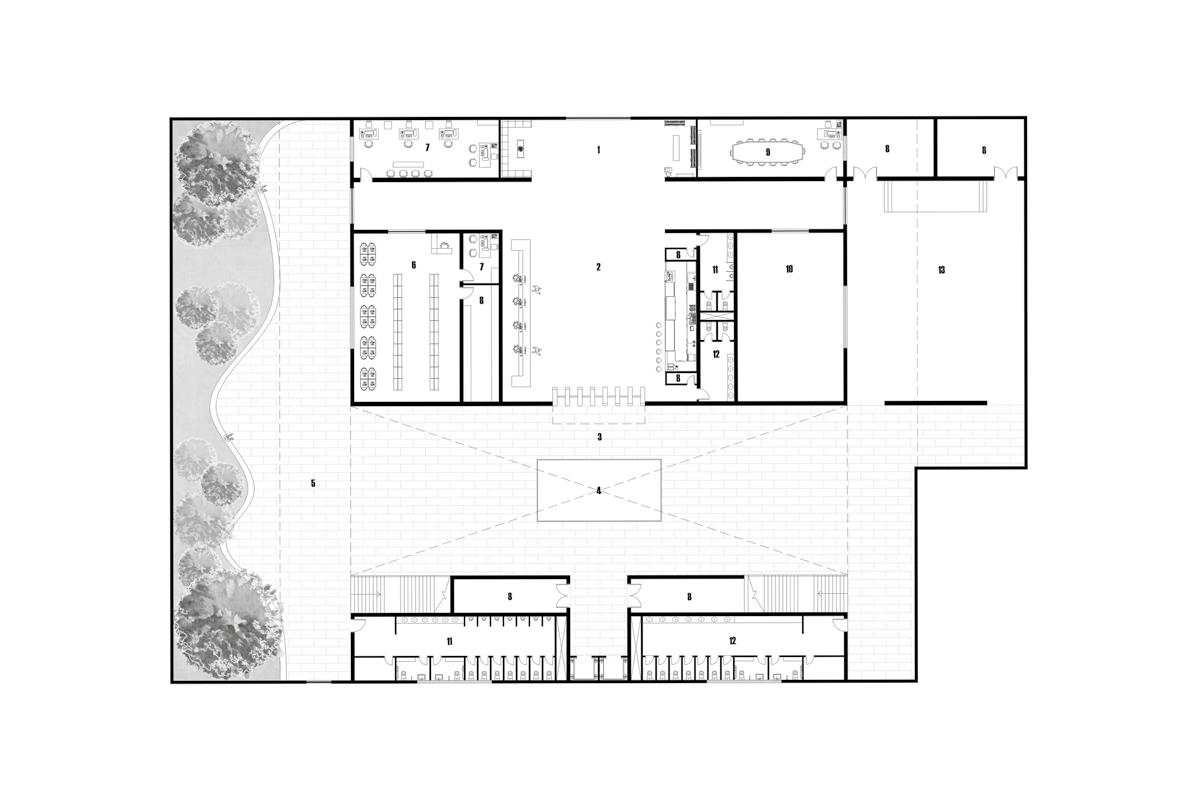

Figure (2) shown above, the ground floor plan with the first courtyard and the circulation core to the second. Another staircase connects the courtyard with the first floor outdoor area.

Figure (3) shown on the adjacent page, the exhibition space with natural lighting and Mashrabeya shading.

Figure (4) shown above, the museum”s main facade with its corresponding section showing the malqaf and main circulation tower connecting the two masses.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Nadeen Amged

Students

Raheem Khaled

Salma Moussa

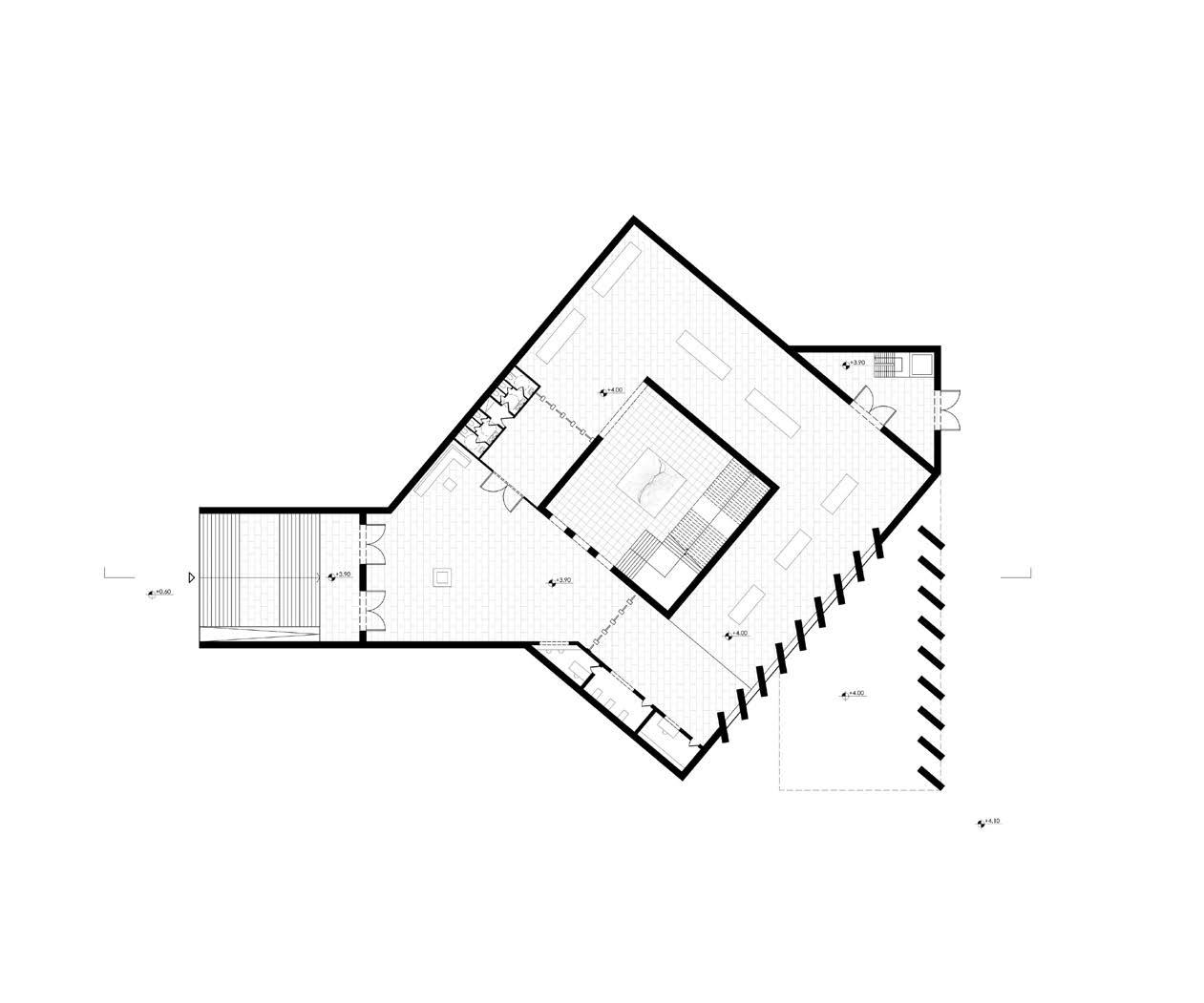

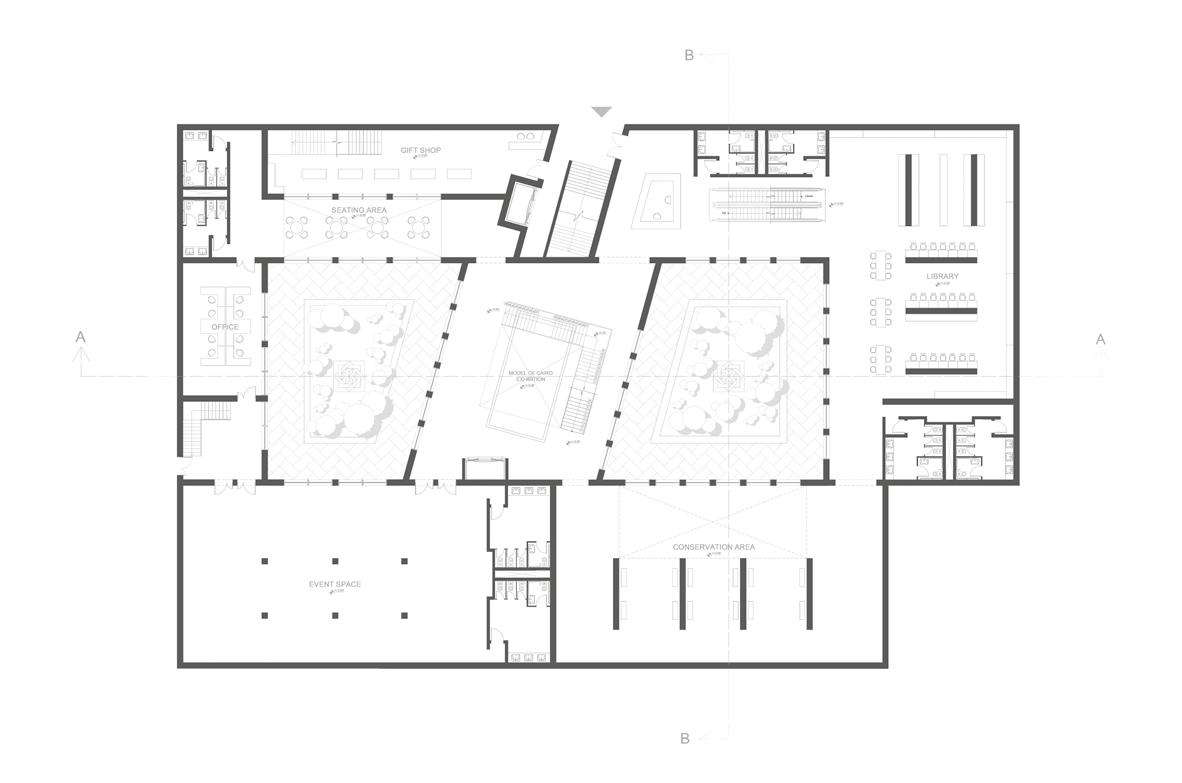

This project is a contemporary courtyard museum set within the historic fabric of Old Cairo, near Al-Rifai Mosque and Hassan Fathy’s house. The design is shaped by two main visual axes – one framing the iconic Citadel, the other aligned with the historic Al-Rifai and Sultan Hassan Mosques. These sightlines inspired two fully glazed picture windows, each emphasized by bold extrusions from the building’s mass. The museum’s courtyard anchors the design, offering a serene inner world while maintaining strong visual and cultural connections to its historic surroundings. This interplay of heritage, view, and modern form creates a reflective and immersive spatial experience.

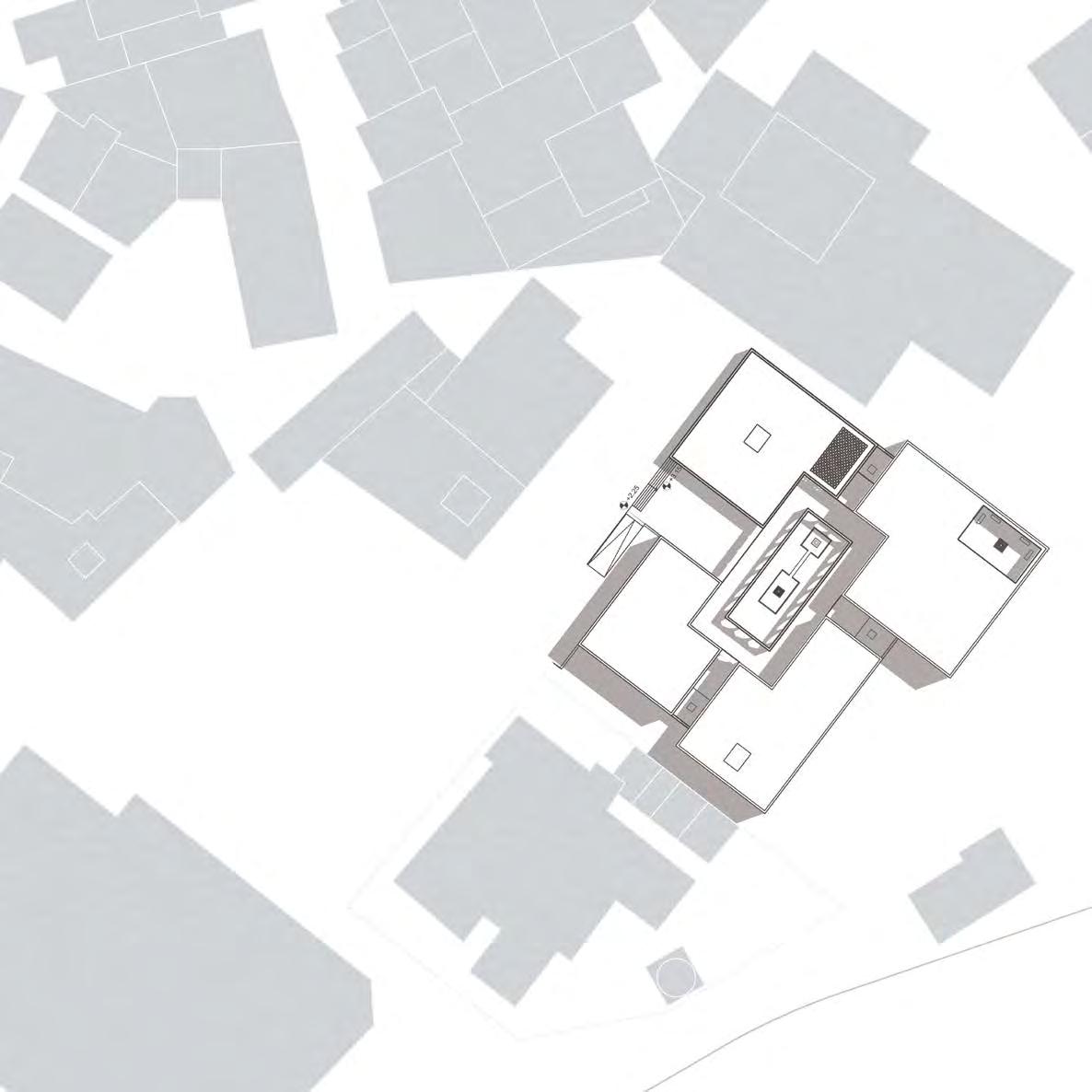

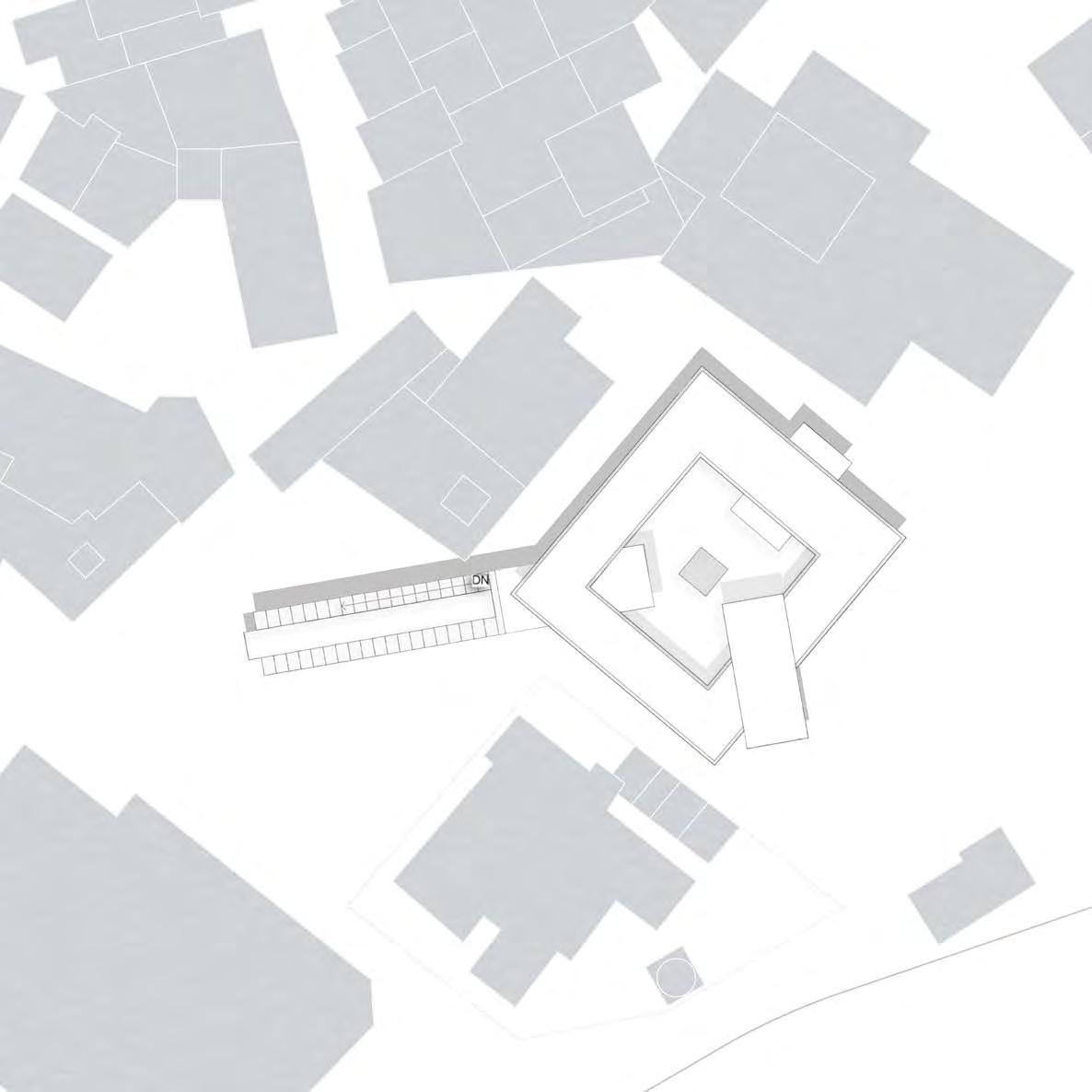

(1) Shown on the left page, the site plan showing the building in relation to the surroundings and the two-way extruded form along two main axes.

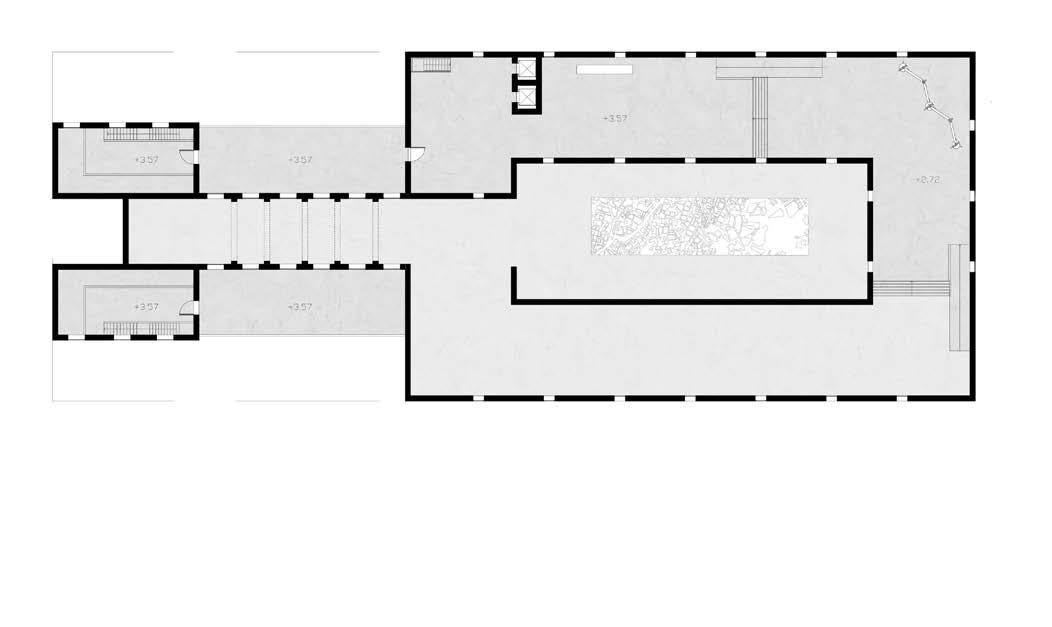

Figure (2) Shown above, the ground floor plan revealing the layout with a staircase in the courtyard, as commonly seen in Old Cairo Houses.

(3) Shown on the left page, a shot of the entrance situation from the lower level street; Darb Al

Figure (4) Shown above, the museum”s South facade with shading concrete walls which also serve as structural support.and its corresponding section.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal Arch. Nadeen Amged

Student Marina Sorour

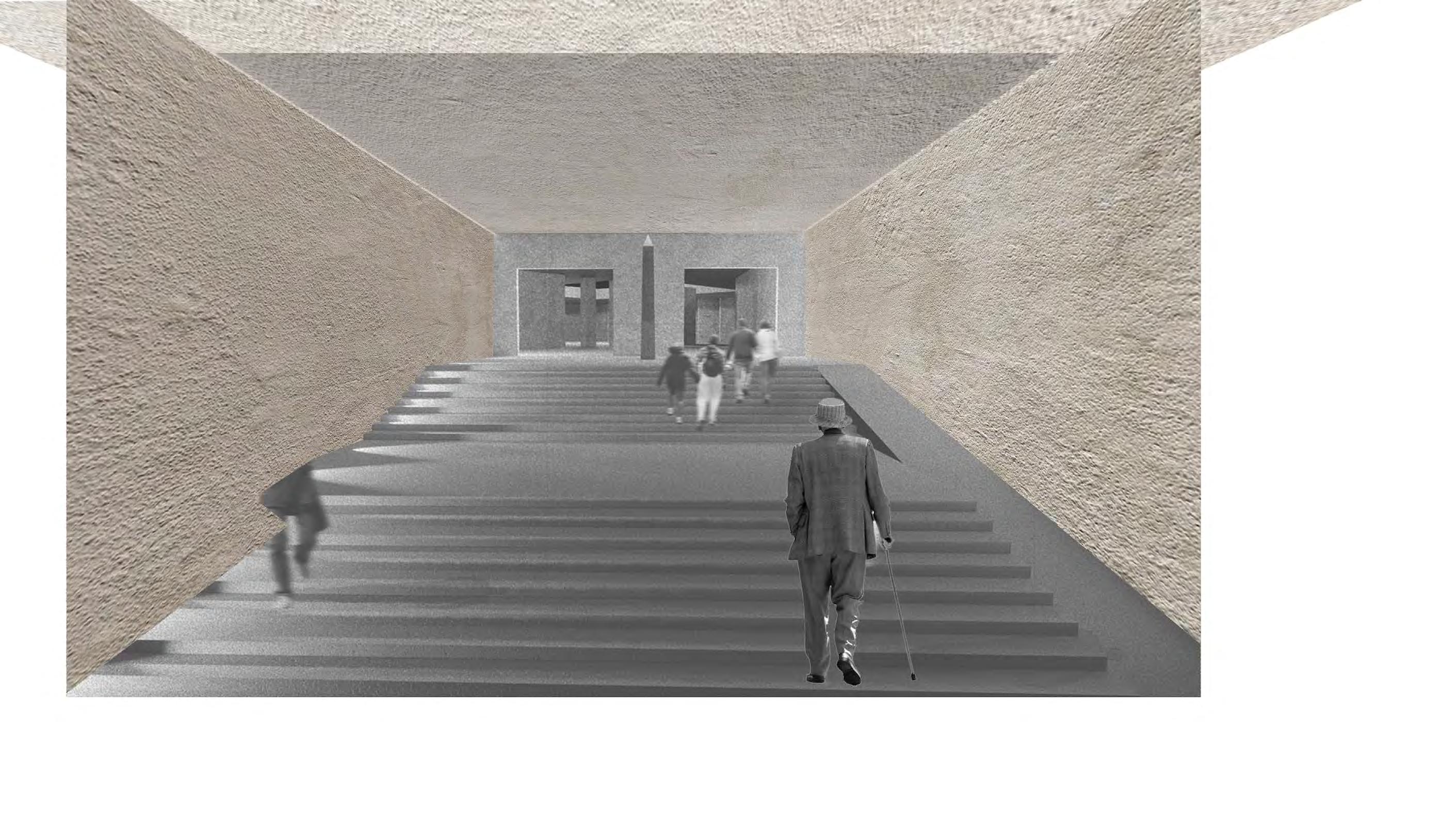

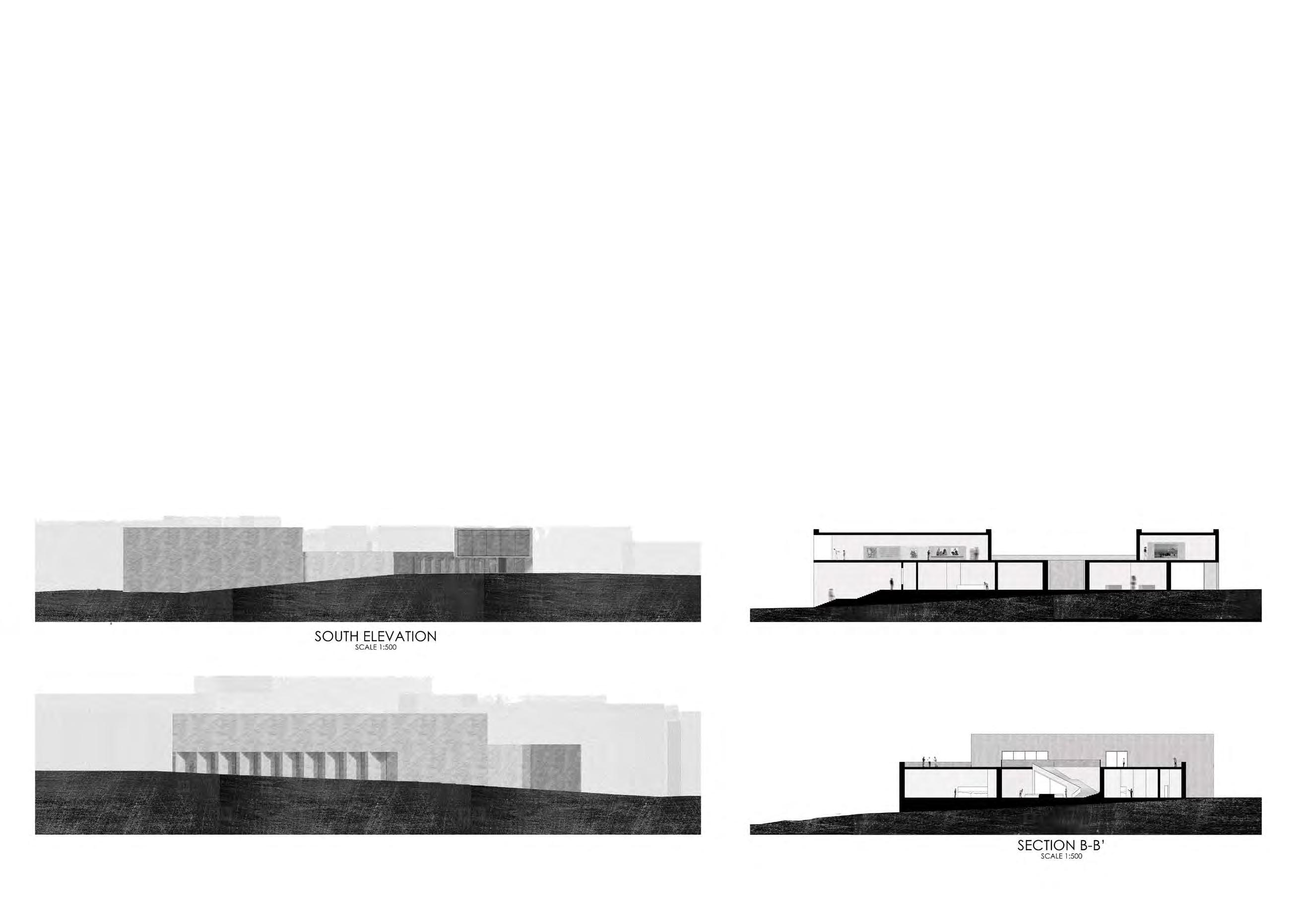

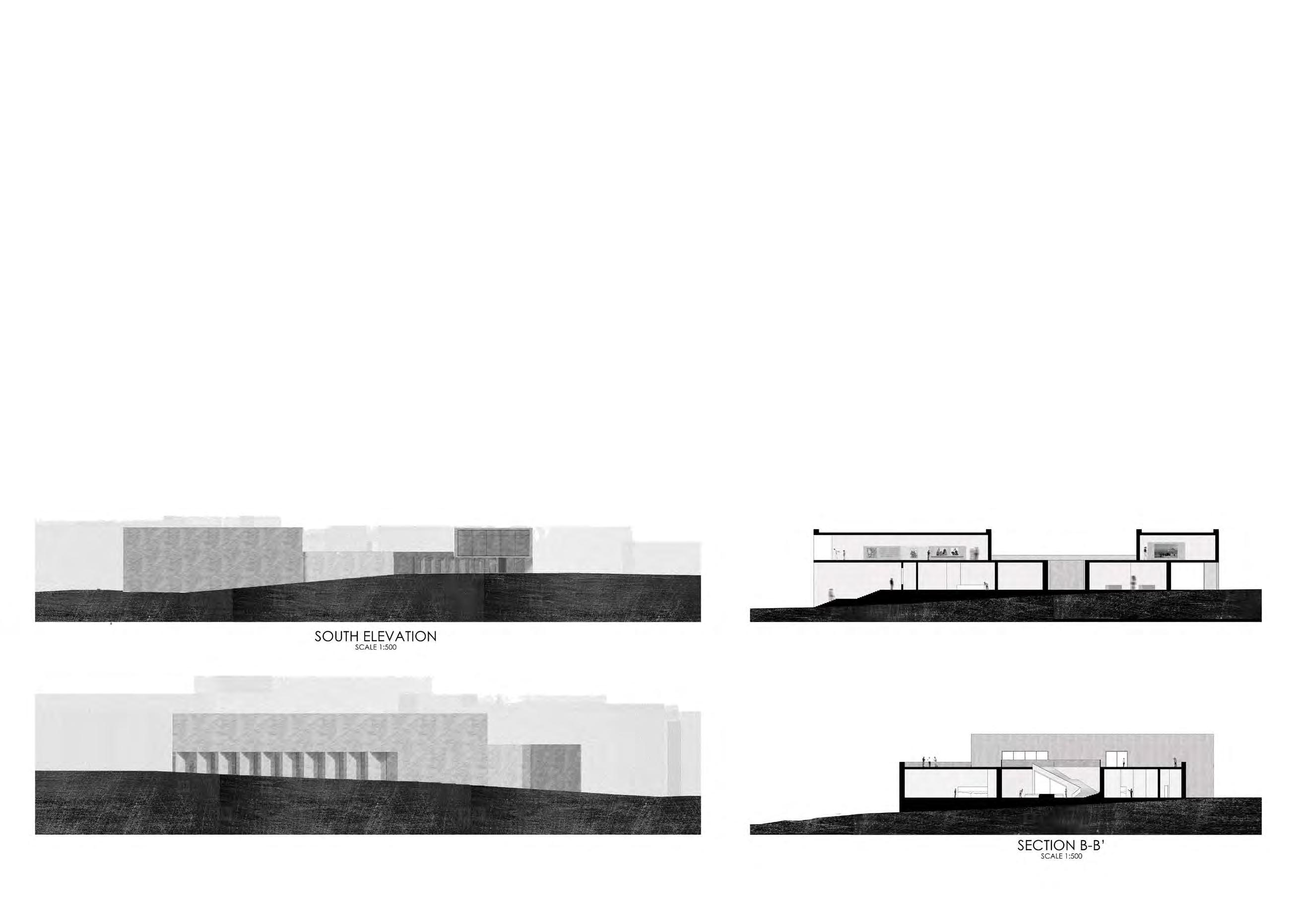

The Museum of Cairo is a time machine honoring the beautiful city of Cairo with its blend of historical architecture. Taking you through four different eras, the museum takes you through the Greco-Roman era, to the Christian era, then the Islamic era, all the way to the top to look over Cairo as it is today. Contrasting with the museum’s fixed path, the outside area takes you through a meandering path inspired by Old Cairo’s darbs and attafas with its intertwining routes.

Figure (1) Shown on the left page, the museum placed in the site with an axial orientation extended from Al Rifai and Sultan Hassan Mosques.

Figure (2) Shown above, the symmetrical layout of the ground floor plan, offering human-scale experience with well proportioned spaces.

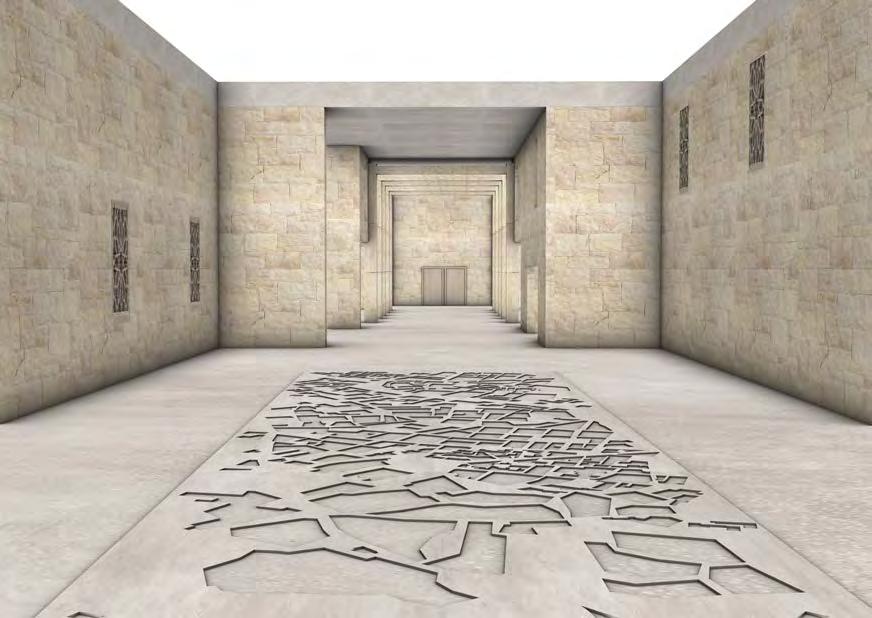

Figure (3) Shown on the left page, a hall formed by stone walls, echoing the material language of its historic surroundings

Figure (4) Shown above, a section illustrating the sequence of spaces, and its corresponding elevation with mashrabeya openings stabilizing indoor temperature.

Figure (5) Shown above, a hall formed by stone walls, echoing the material language of its historic surroundings and the map model of Cairo placed in the heart of the building.

Figure (6) Shown on the right page, the double height entrance pathway towards the exhibition space.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Nadeen Amged

Students

Lina Ramez

Mariam El Sherbiny

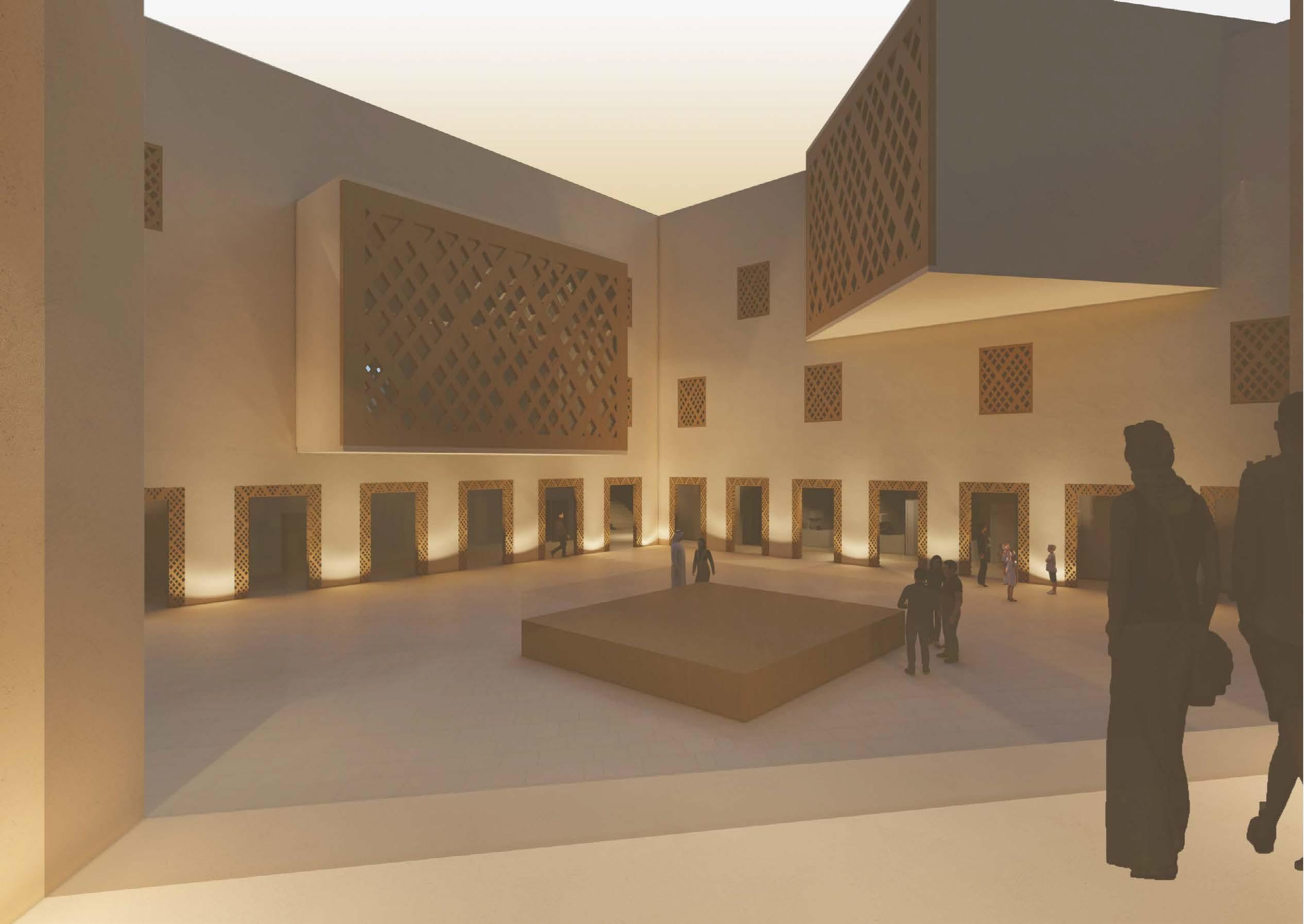

Cairo Heritage Haven reinterprets traditional Arab architecture through modern design, emphasizing elements like the courtyard, balcony, and mashrabiya. Its light-responsive double-skin façade features geometric patterns that cast dynamic shadows, enhancing the atmosphere. A perforated metal mesh allows natural light and airflow while ensuring privacy and cultural relevance. The design balances openness and enclosure, offering a sensory experience rooted in heritage. It thoughtfully adapts historic strategies, such as using water pots for cooling and latticed screens for ventilation, to suit contemporary needs in both functional and aesthetic ways.

Figure (1) Shown on the left page, the museum extending in the site, highlighting the main entrance and the circulation from a level to another.

Figure (2) Shown above, the courtyard framed by different spaces and porous openings creating smooth transition between open and enclosed areas.

PROJECT 01

Lilian Ihab

Mirna Nabawy

PROJECT 02

Ganna Khlaed

Noureen Ehab

PROJECT 03

Ali Atef

Mohamed Ezzat

PROJECT 04

Ali Bassiouni

Omar Abed

PROJECT 05

Nour Elashmawi

PROJECT 06

Nouran Elshall

Jana Khaled

PROJECT 07

Mariam Alaa Eldeen

PROJECT 08

Nour Rateb

Hana Hassaballah

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space 2.0

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Martina Abu Alam

Students

Mirna Nabawy

Lilian Ihab

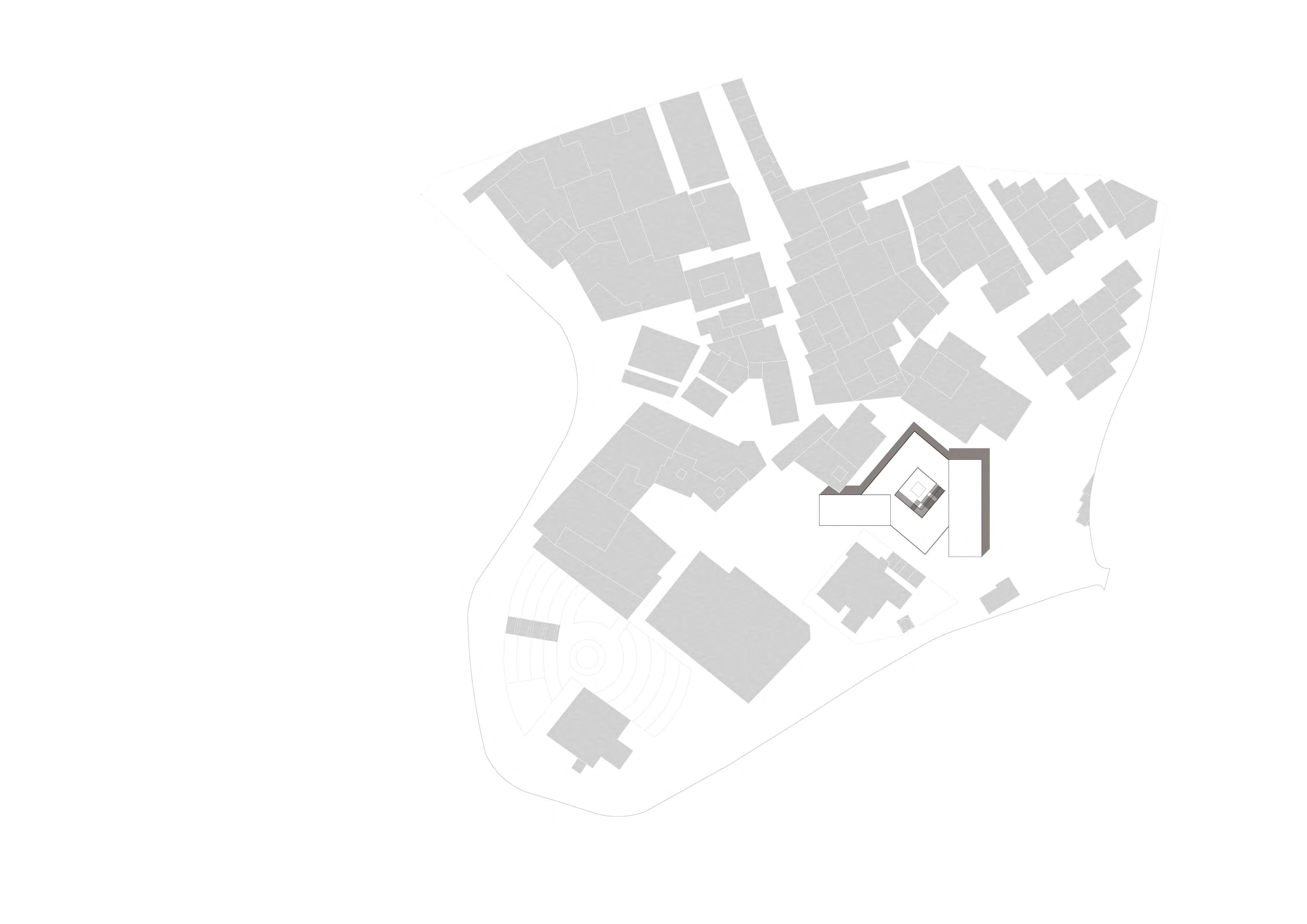

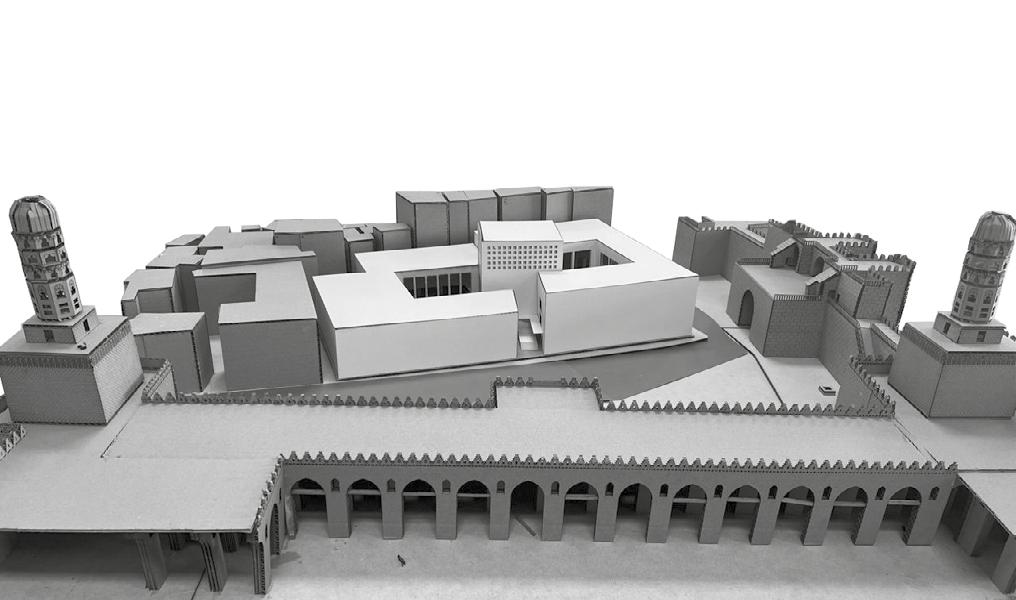

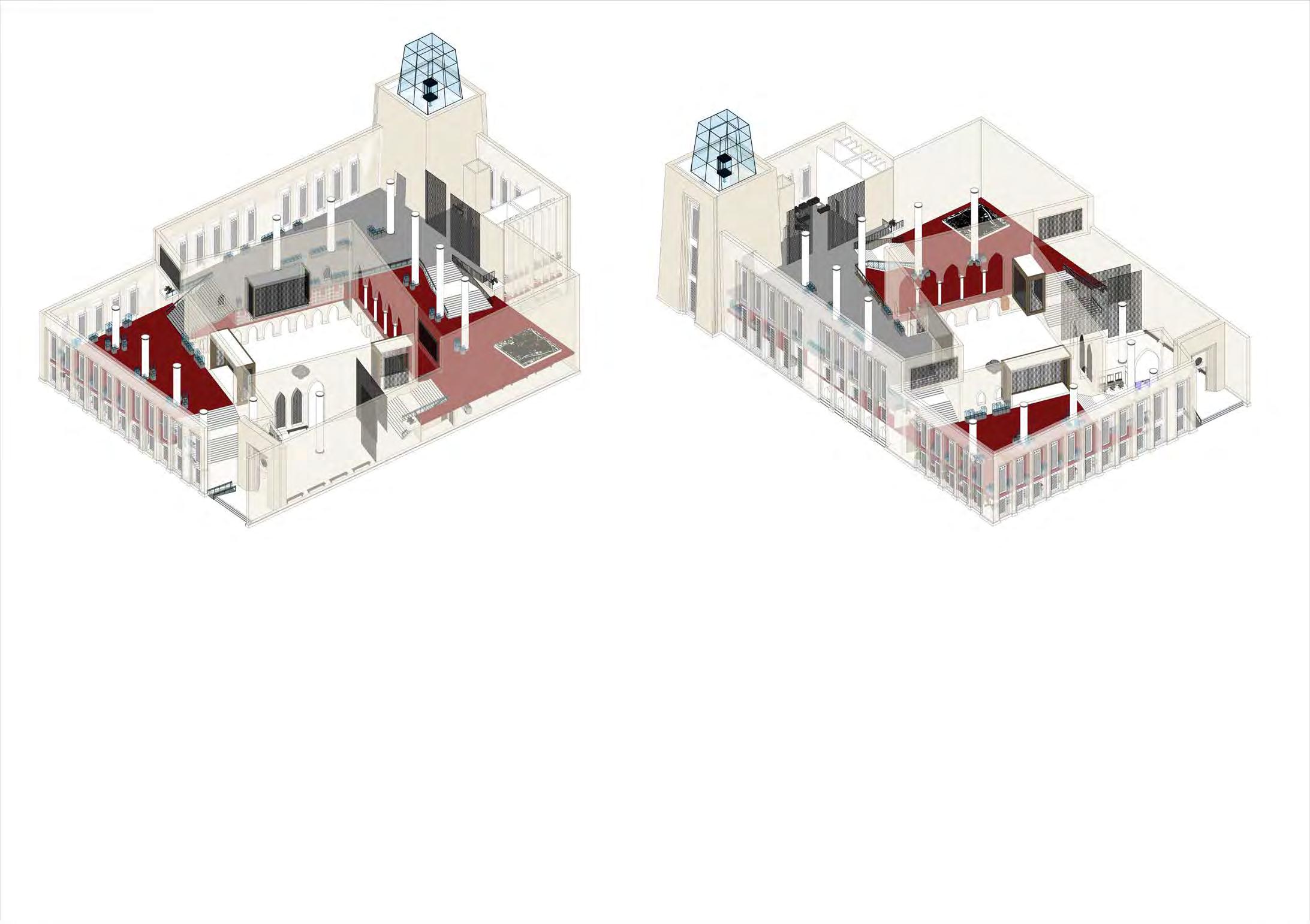

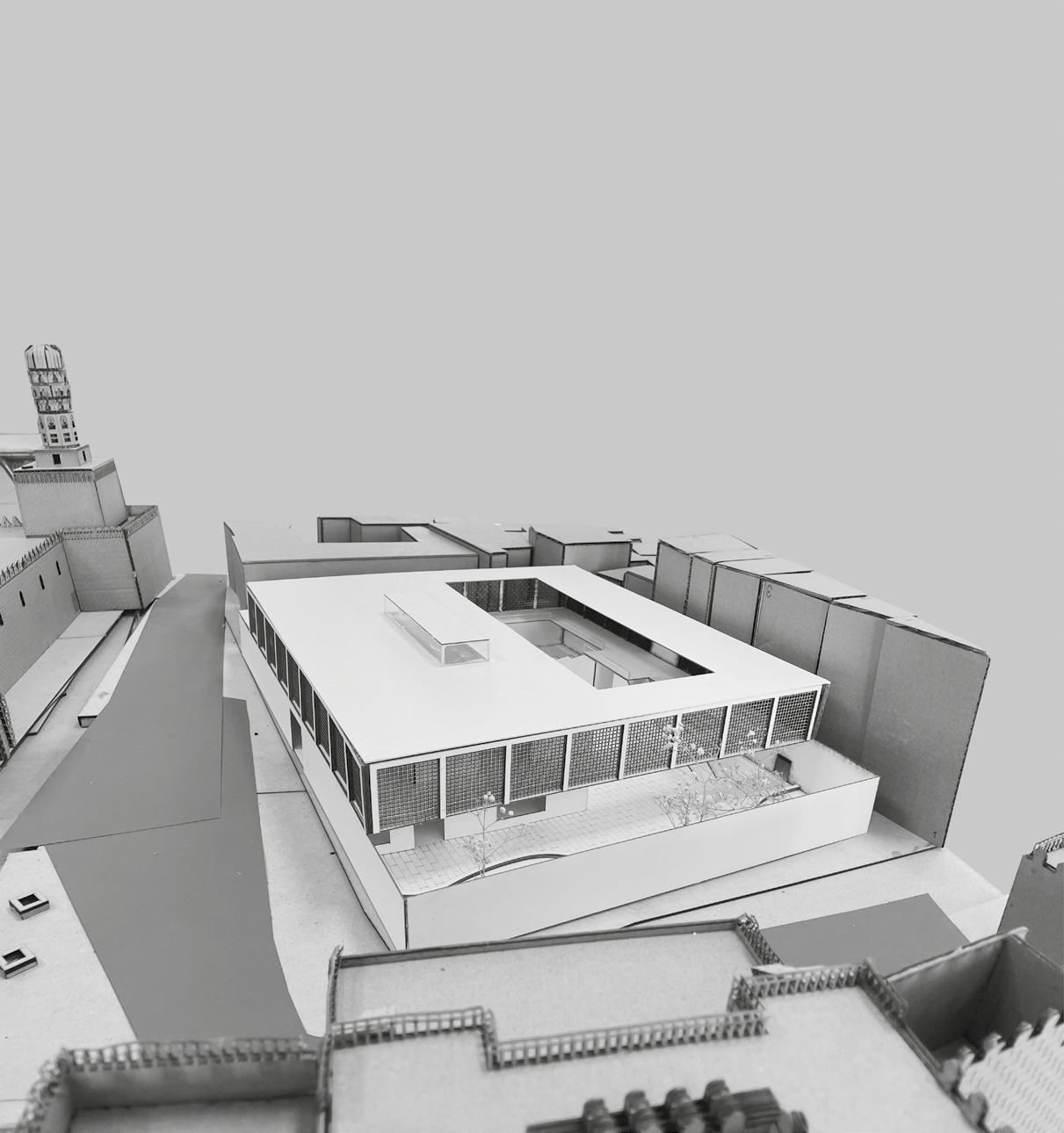

Inspired by the concept of “Bein El-Asrein”, the space “between the two castles”, to create a revitalized cultural hub. The design thoughtfully considers the path through the historic core, using the museum’s courtyard as a central organizing element. Positioned parallel to Bab al-Futuh and AlHakim Mosque, this courtyard serves as a transitional space, connecting the city’s rich past with the museum experience and culminating in a serene south garden.

Figure (1) shown on the left page, the site plan showing the L- shaped “Hall of Light” and division of exhibition spaces.

Figure (2) shown above, the ground floor plan, illustrating the concept of “Bein El Asrein” and a distinct axis, from the entrance to the South Garden.

Figure (3) shown on the left page, the South Garden and how the takhtaboush integrates seamlessly with it.

Figure (4) shown above, a section illustrating the projection room and the main exhibition space dedicated to ages and dynasties.

Figure (5) shown at the top- left, The corridor’s design features high walls that capture and channel light, creating a dramatic play of shadows and illumination.

Figure (6) shown at the topright, the public seating area drawing inspiration from the traditional Takhtaboosh, inviting people to gather and enjoy the museum’s outdoor spaces.

Figure (7) shown below, the physical model placed in the context of the site and how it interacts with its surroundings.

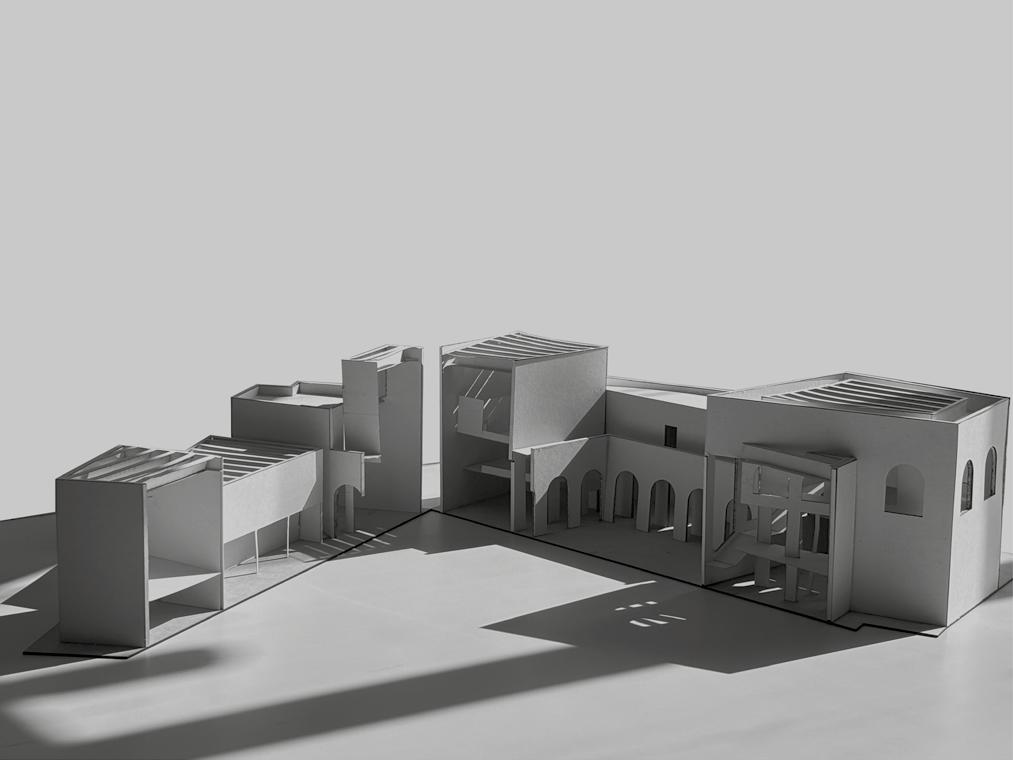

Figure (8) shown on the right page, the physical model as a section showing division of spaces.

of the chosen site. This is why relying on the architecture of Bab el Futuh and Al Hakim Mosque were important to come up with light spaces versus dark narrow corridors, massive exterior stone blocks versus lightweight interior structure.

Cairo, typically inaccessible in surrounding buildings. Designed with perforations that function like a mashrabiya, it not only frames light but also promotes passive ventilation, linking visibility and climate control through traditional principles.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space 2.0

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Martina Abu Alam

Students

Ganna Khaled Noureen Ehab

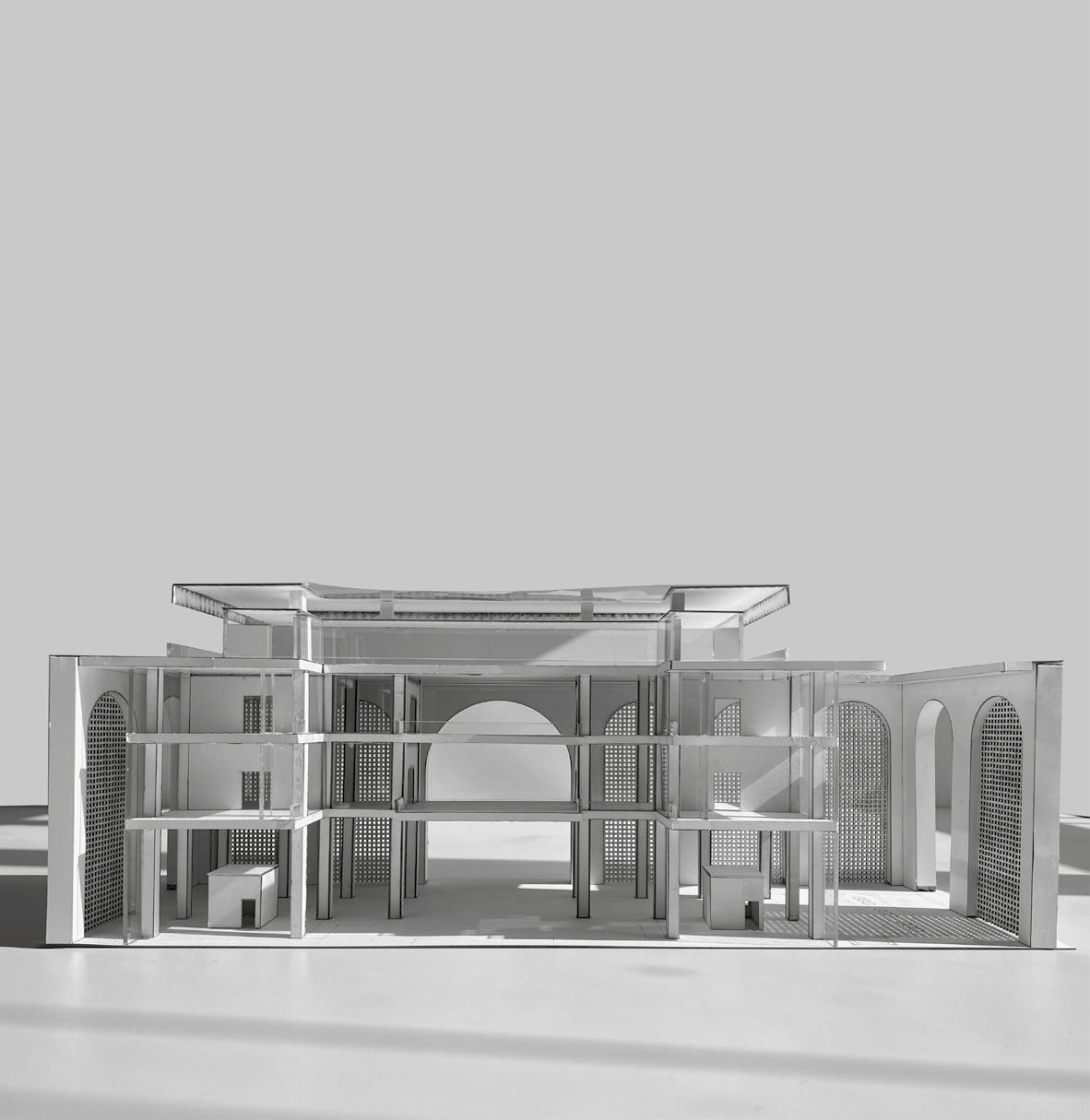

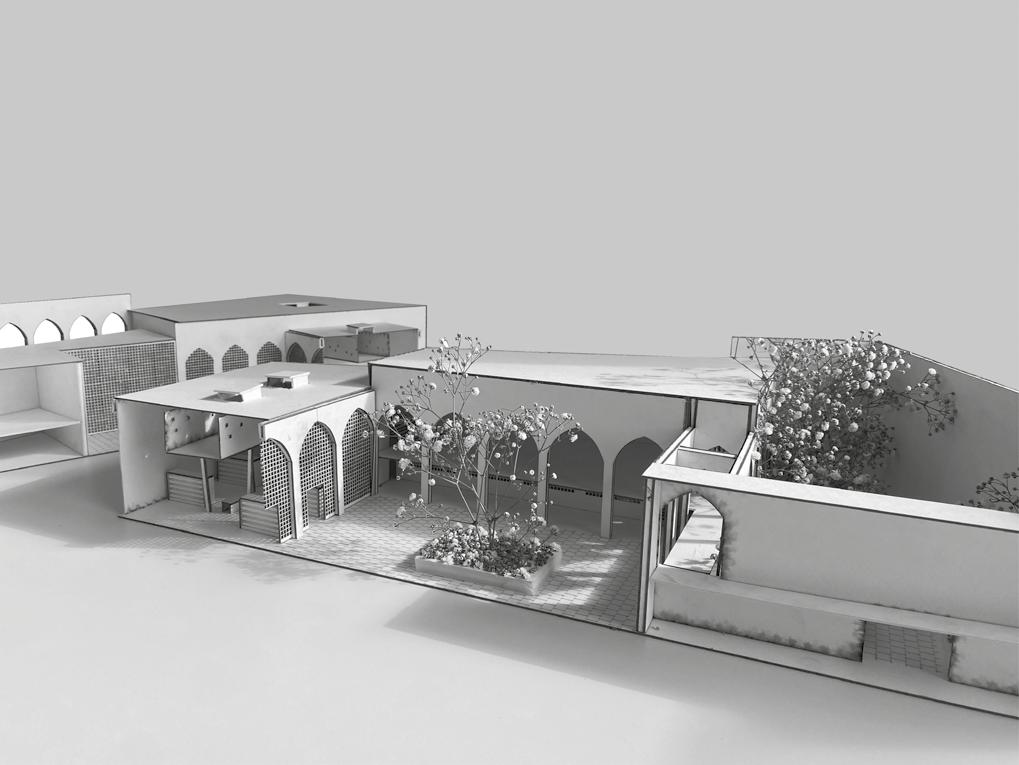

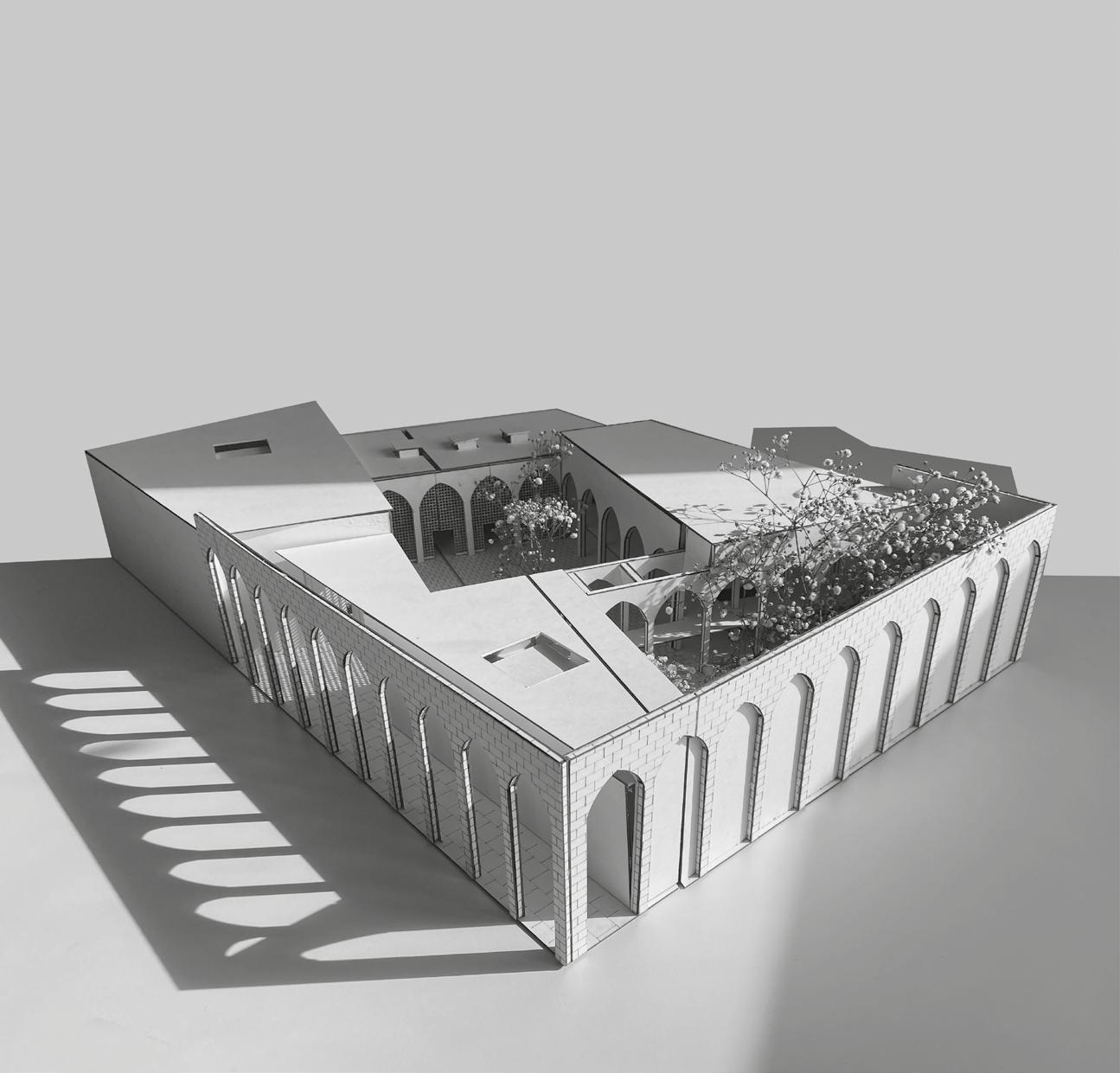

The architectural museum is inspired by the tradition of the Sabil but is also based on an extensive site analysis of the Mamluk and Ottoman periods that inform and underpin the design. The building is wrapped in an arched mashrabiya shell that balances light filtration, creates complex shadows, and allows for a shaded semi-outdoor seating area that helps soften the transition from the museum and the historic realm. The museum is organized around a courtyard with water feature typical of Islamic gardens, and the exhibition halls circle the courtyard.

Figure (1) shown on the left page, the site plan, revealing how the museum is carefully positioned within its historic context, with axial alignments to Al-Hakim Mosque and Bab El Futuh.

Figure (2) shown above, showcases the museum’s architecture, where a mashrabiya-clad shell, central water feature, and thematic exhibition halls echo the rich traditions of Mamluk and Ottoman design.

Figure (3) shown on the left page, the exhibition space, highlighting the interplay of natural light, curated displays, and architectural detailing. The design enhances the storytelling of the exhibited artifacts.

Figure (4) shown above, the museum’s arched mashrabiya skin and tranquil courtyard, both of which serve as key elements in bridging the building with its historic context.

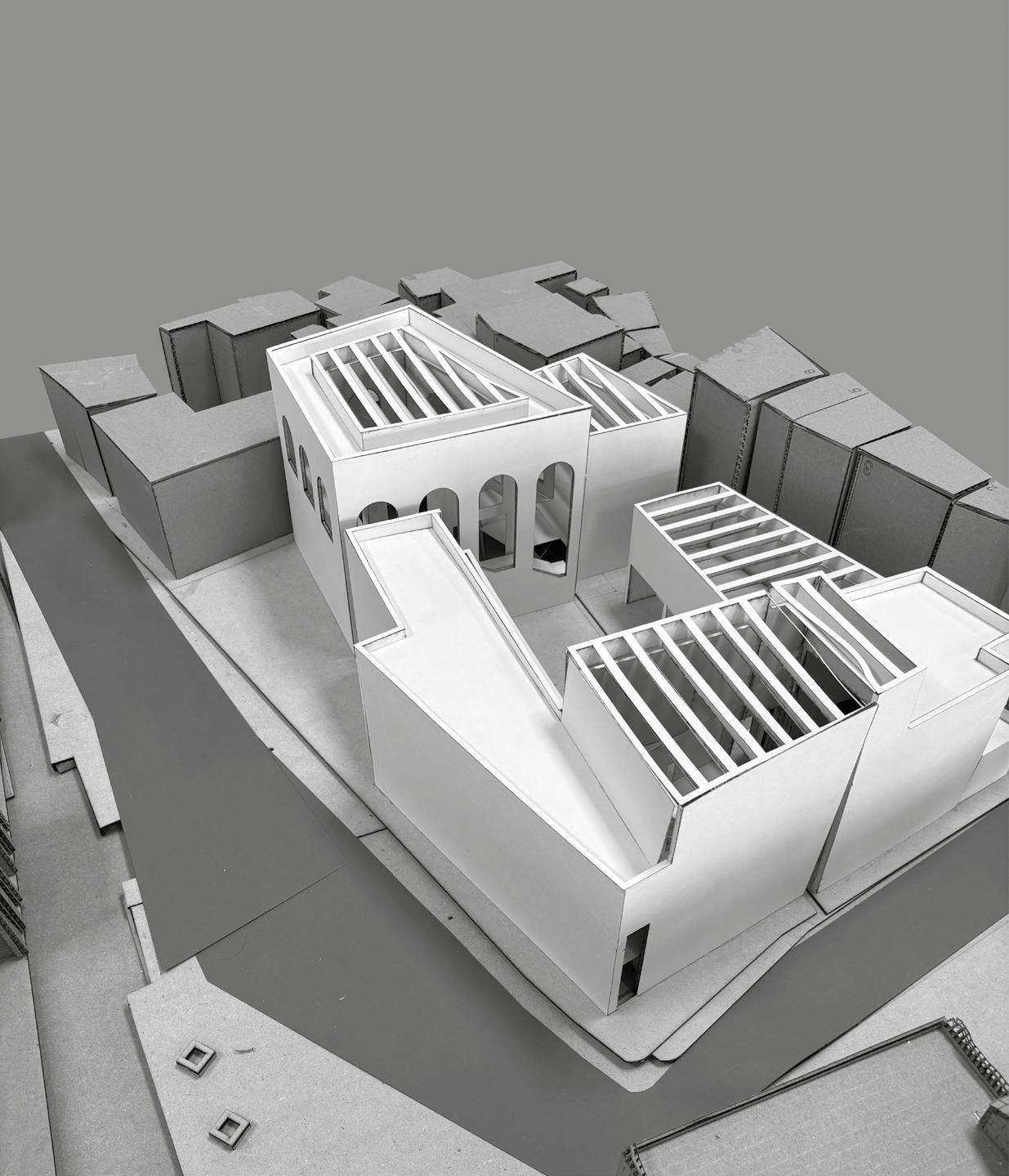

Figure (5) shown below, the physical model placed in the context of the site and how it interacts with its surroundings.

Figure (6) shown on the right page, the physical model as a section showing division of spaces.

In this section, the visitor encounters two gates of quality, Bab el Futuh, and the project’s arched mashrabiya, that serves as a climatic buffer and is also a contemporary interpreted portal that transitions from the contemporary to the historical. Another focus of the design is how the huge court is replicated in a way that makes it the most dominant, grand space.

The museum features a central courtyard, anchored by a water feature, in keeping with the thinking surrounding gardens and such courtyard concepts. The spatial arrangements encourage fluidity and circulation, while retaining the ability for the central courtyard to be seen from any corner of the museum; differentiating the museum experience.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space 2.0

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Martina Abu Alam

Students Ali Atef Mohamed Ezzat

The museum is located in a historic area of Cairo, adding to its story and continuing the city’s rich heritage of Islamic architecture, embracing the traditional aspects such as courtyard typology, well-proportioned space, and an innovative natural lighting and ventilation strategy. It is designed to blend peacefully with the surroundings, creating a calm cultural spot in the busy city. The familiar architectural styles used in its design make it comforting and inspiring for visitors.

Figure (1) shown on the left page, the site plan of the museum adjacent to Bab El Futuh and AlHakim Mosque, highlighting its spatial dialogue with the historic fabric of Old Cairo.

Figure (2) shown above, the layout respects axial relationships and integrates traditional Islamic planning principles into a contemporary framework.

Figure (3) shown on the left page, the fusion of old and new is evident in the details and materials. Islamic craftsmanship is reimagined through modern techniques, providing visitors with a space that honours heritage.

Figure (4) shown above, the elevation and section, highlighting the circulation path from the entrance through to the exhibition halls.

Figure (5) shown below, the physical model placed in the context of the site and how it interacts with its surroudings.

Figure (6) shown on the right page, the physical model and how shadows interact with the architectural form.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space 2.0

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Martina Abu Alam

Students

Ali Bassiouni

Omar Abed

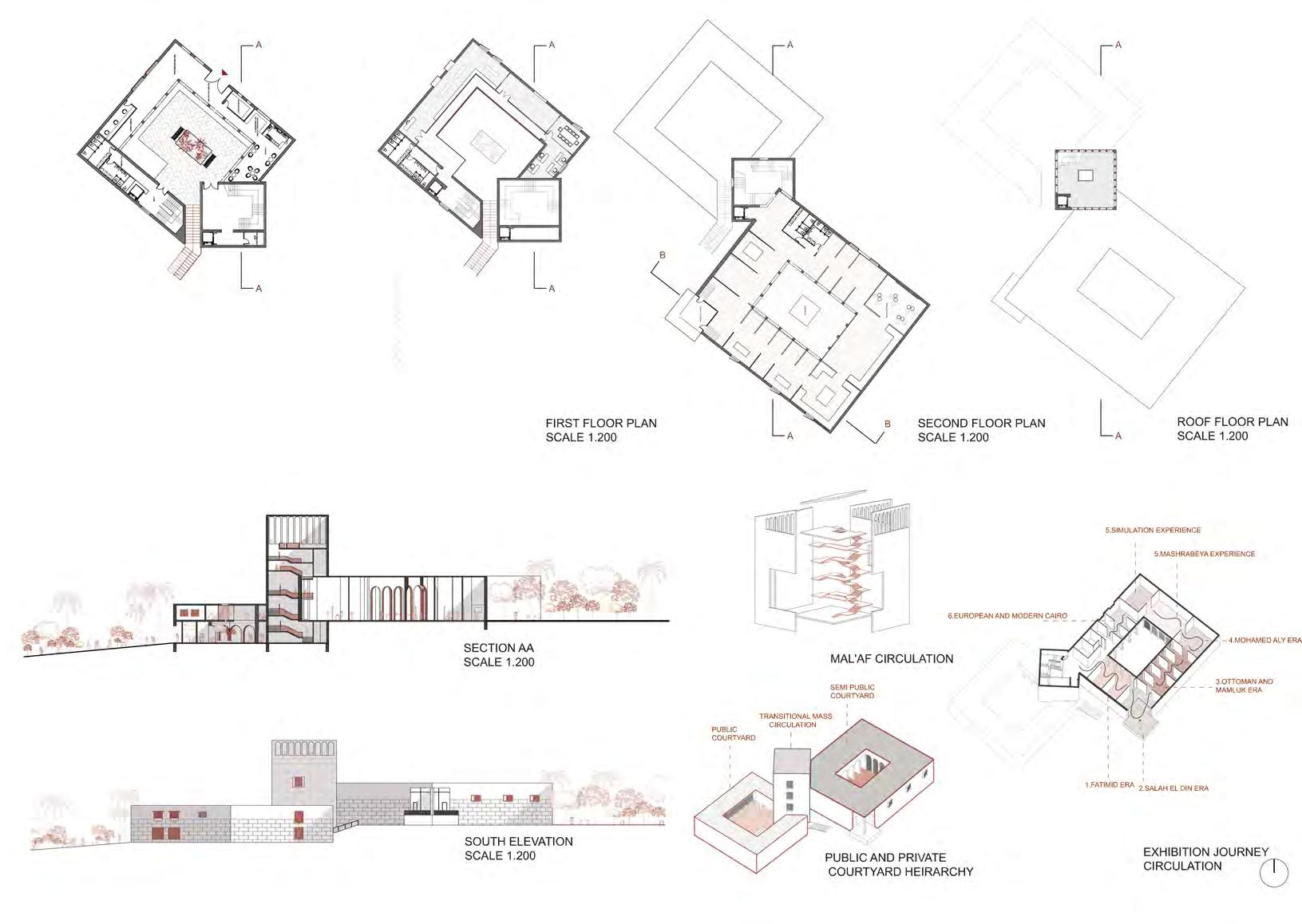

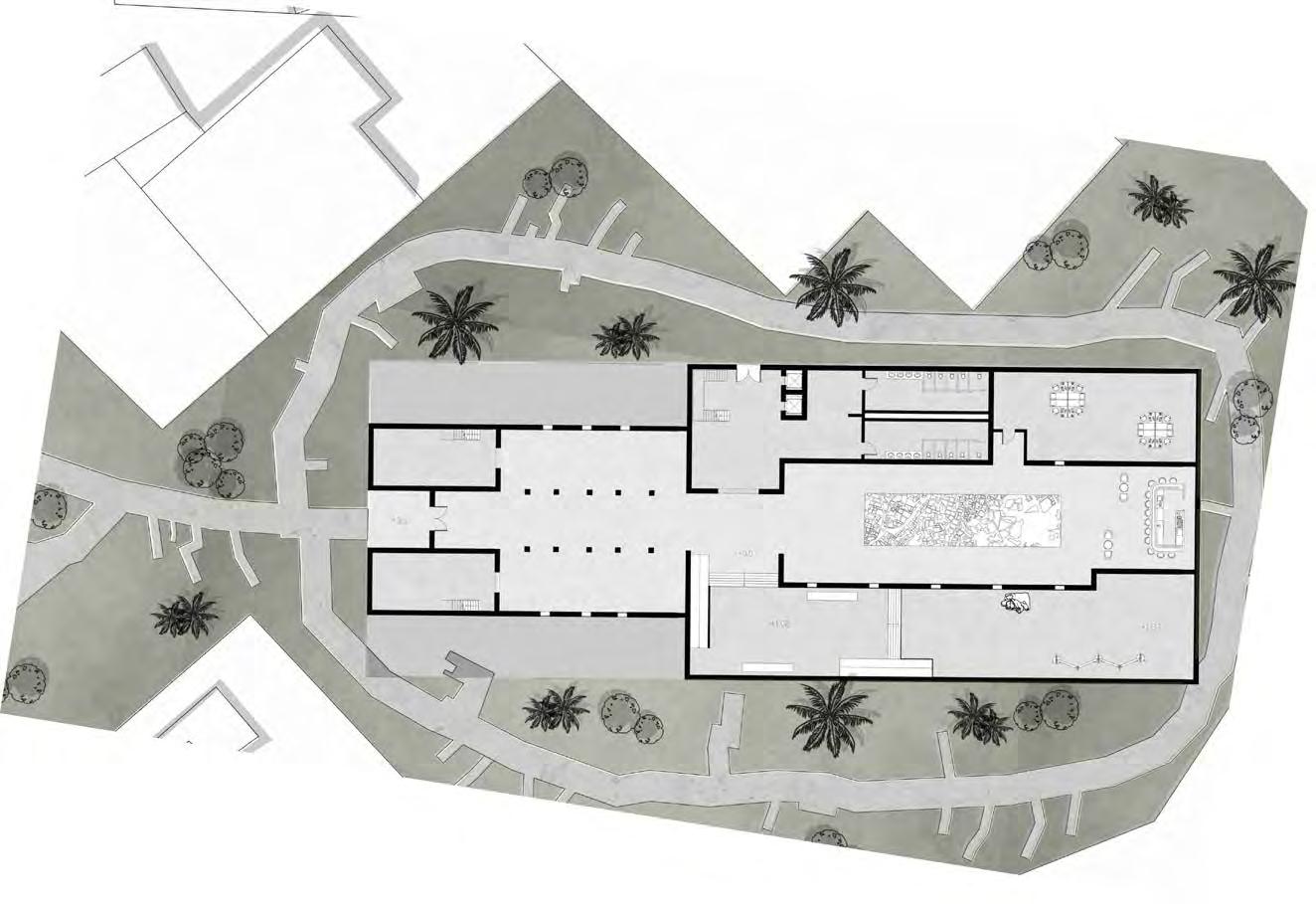

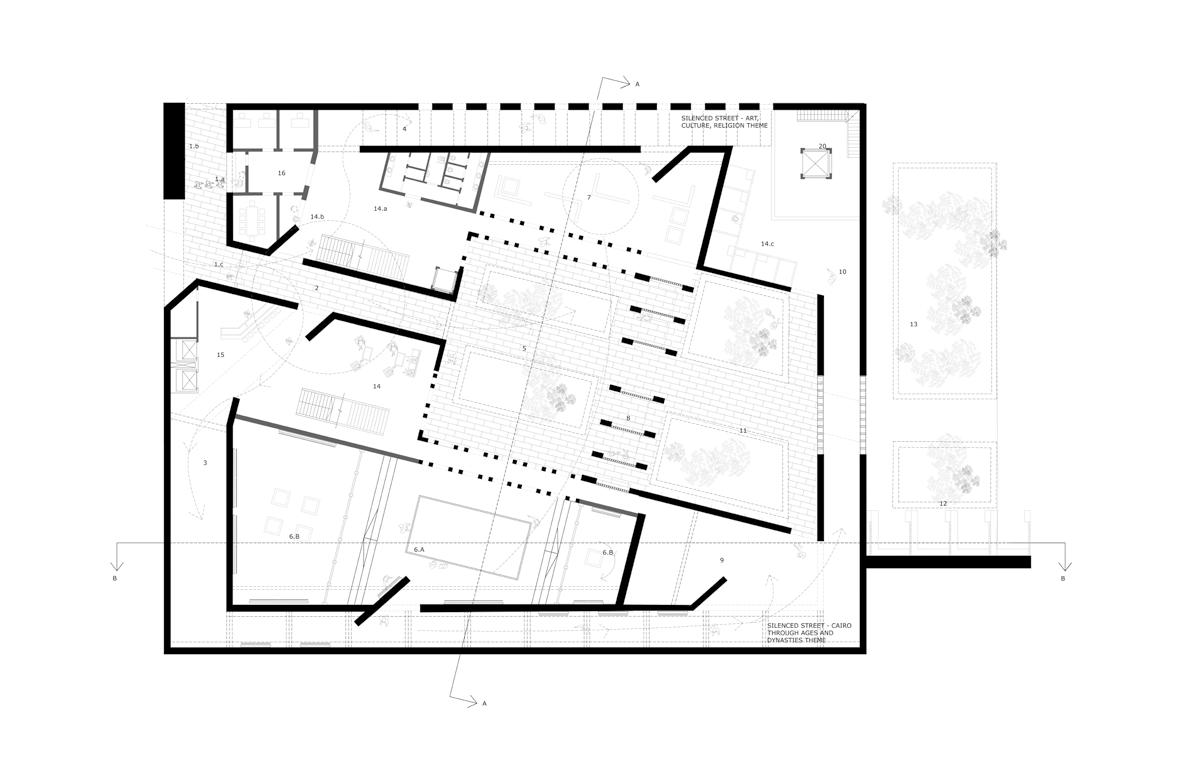

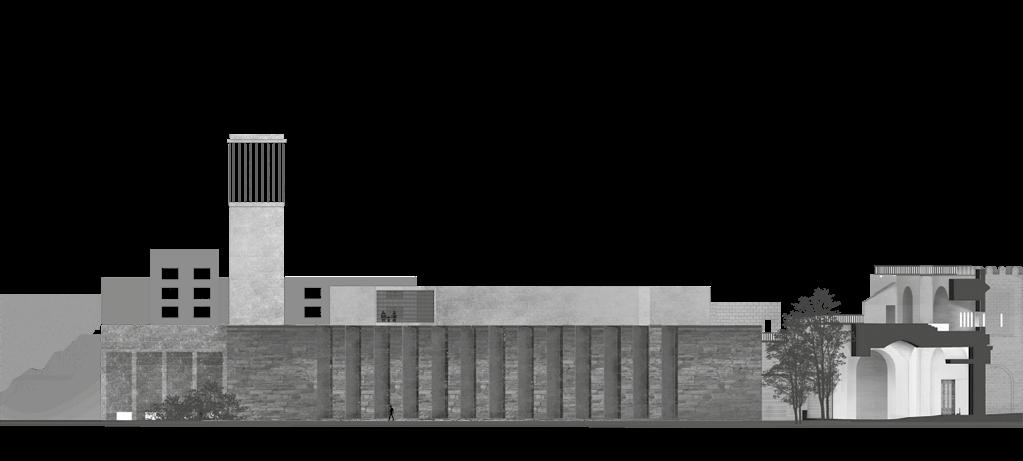

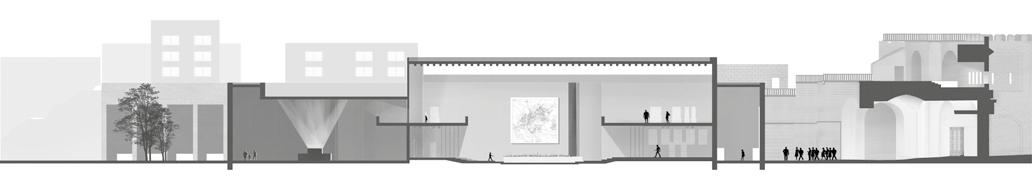

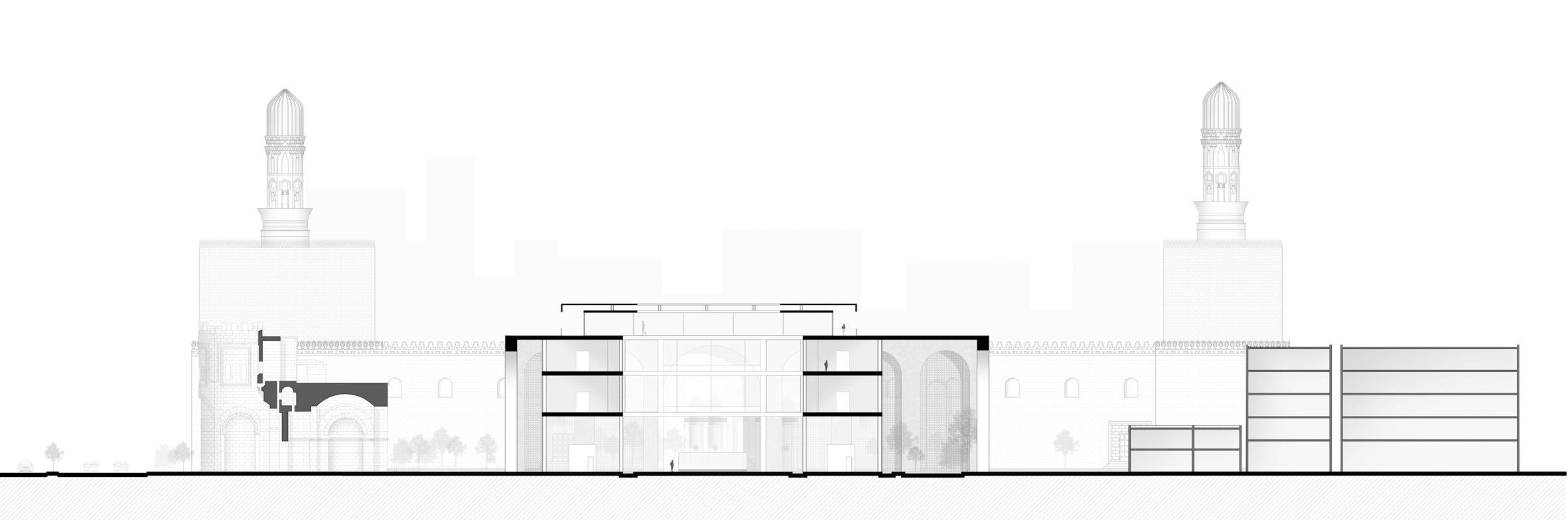

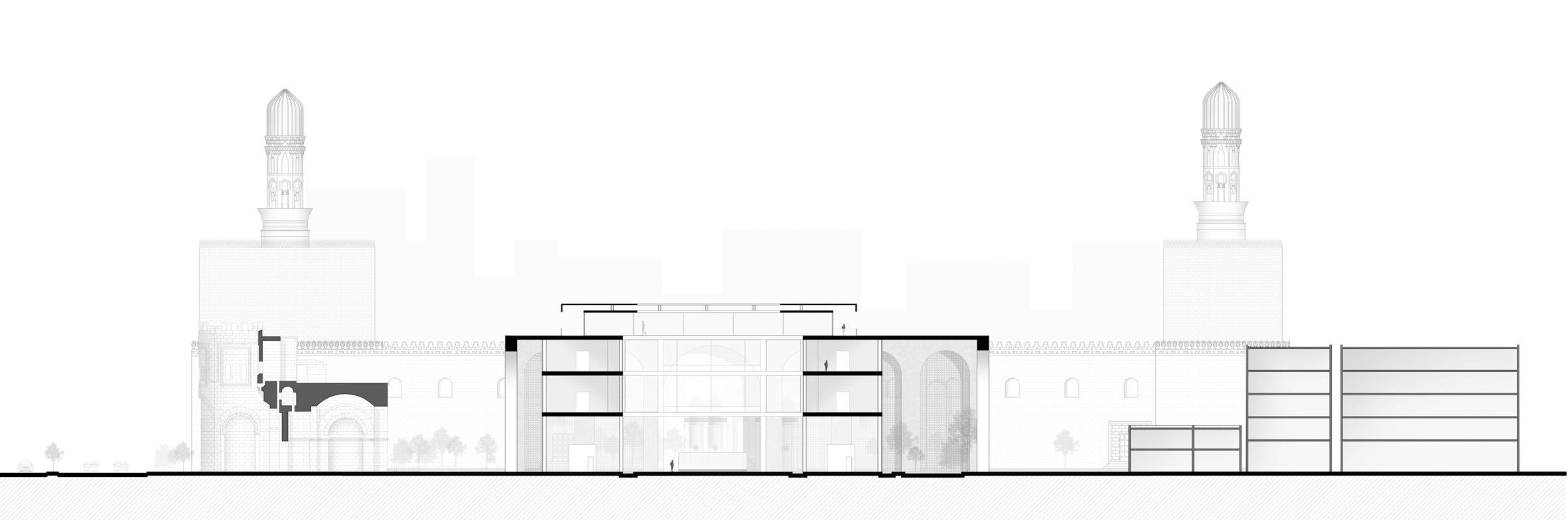

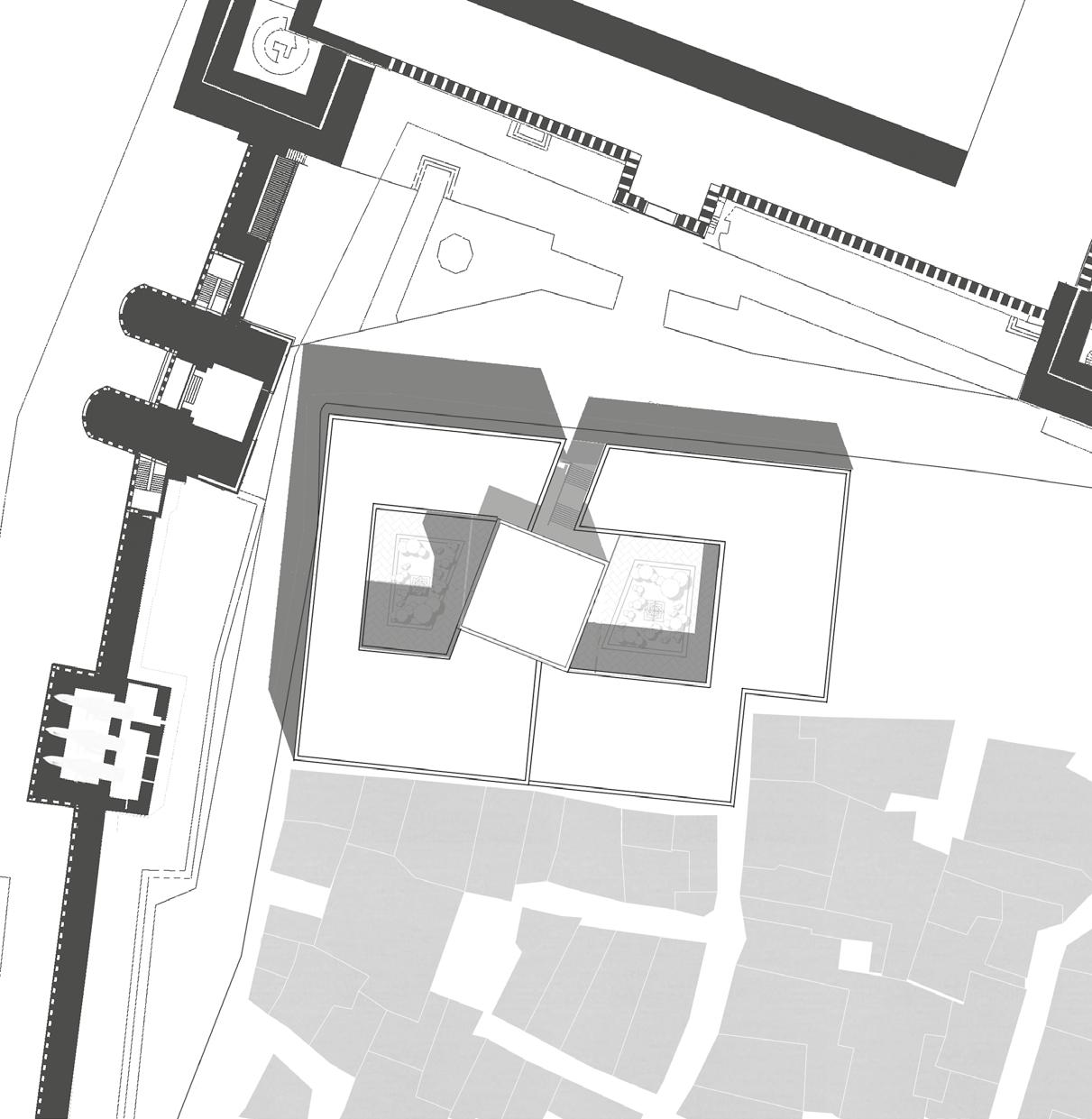

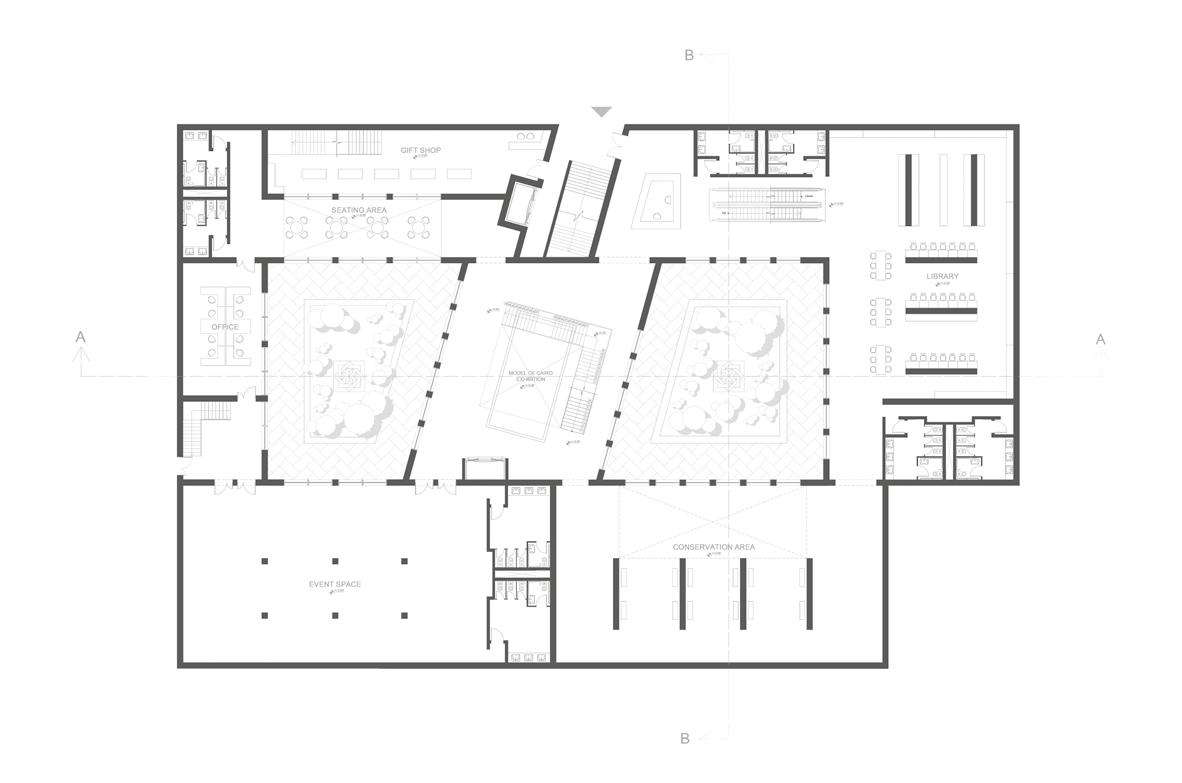

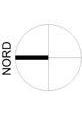

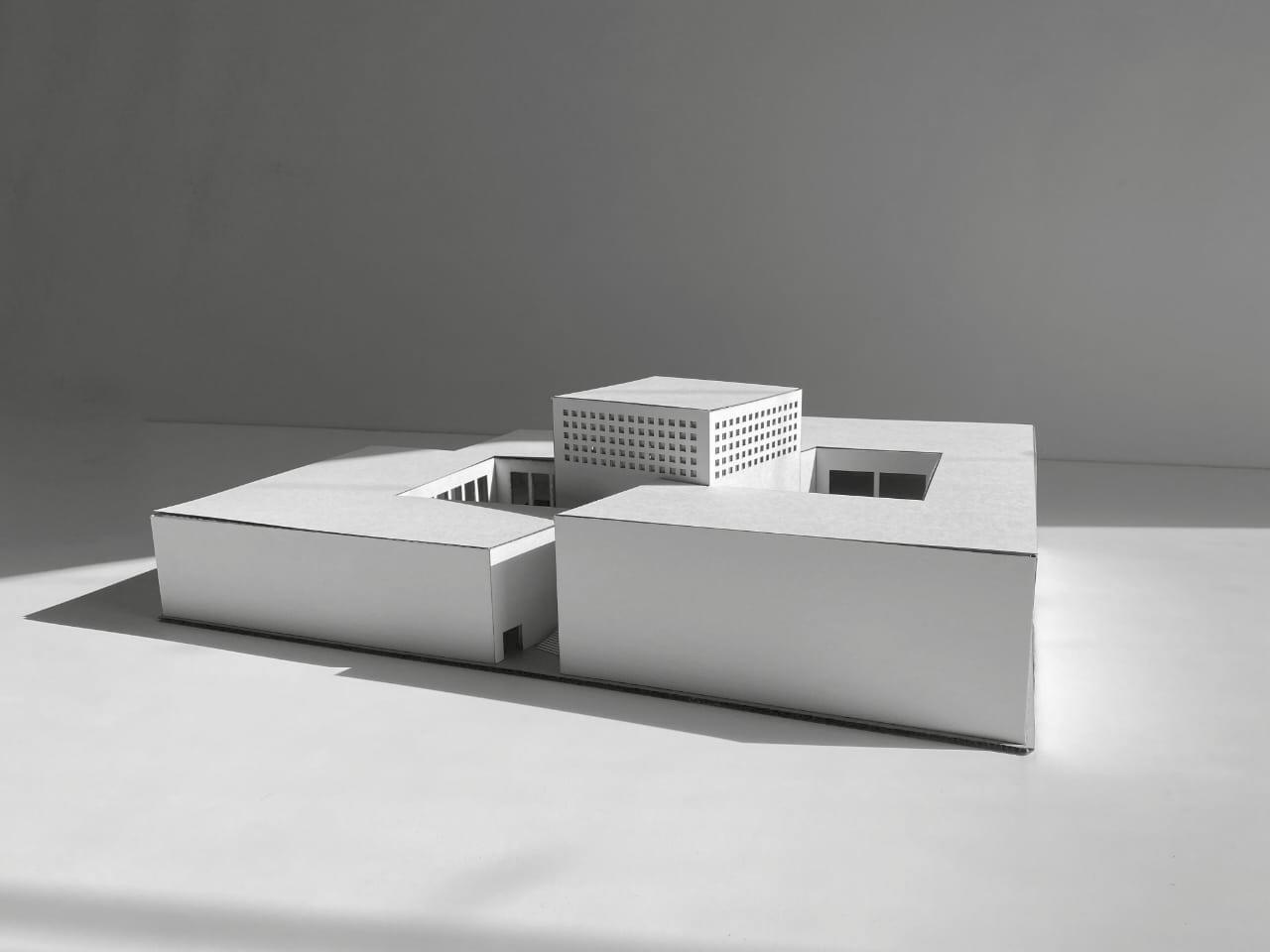

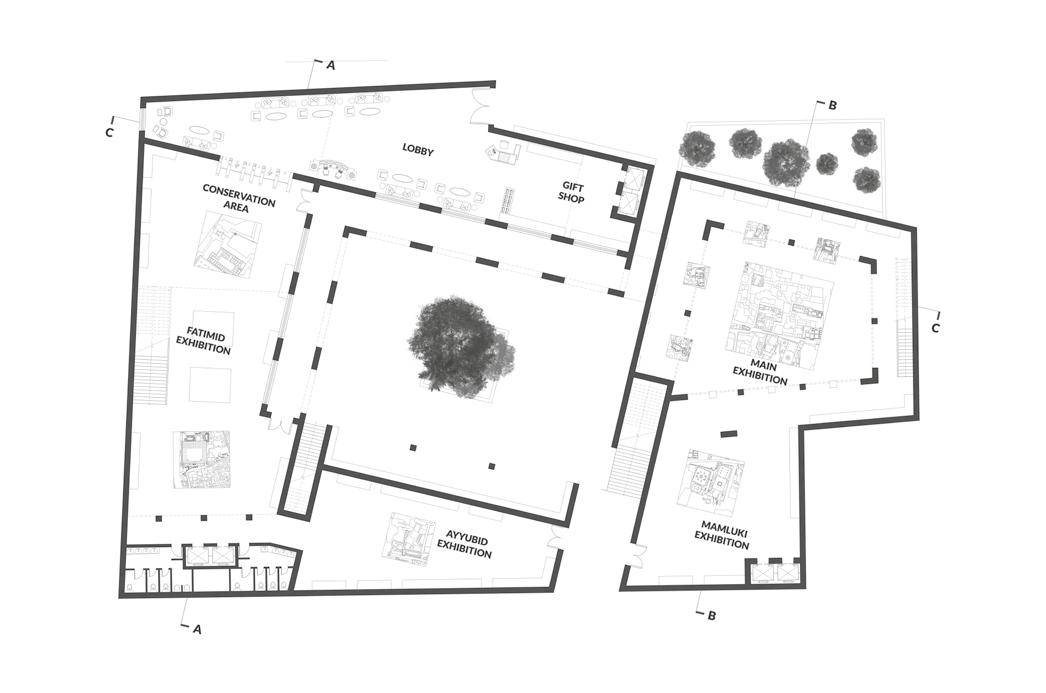

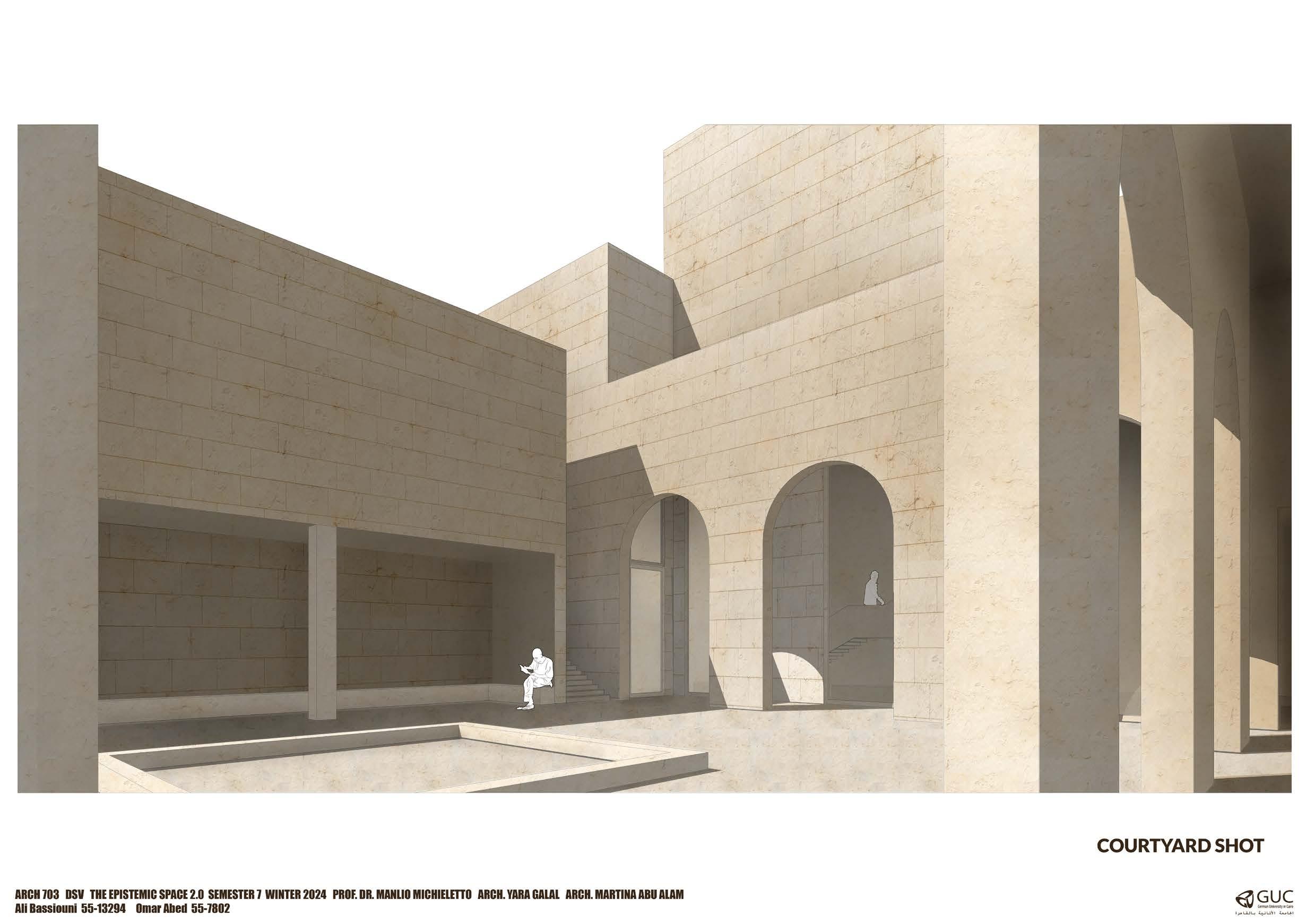

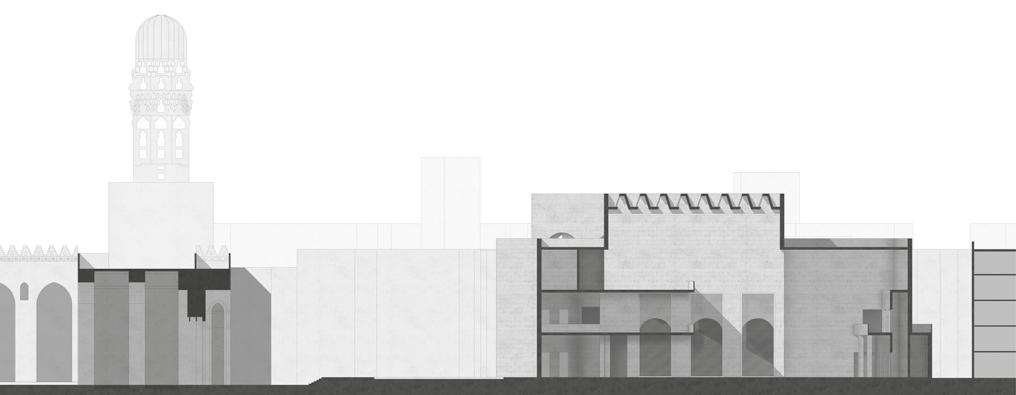

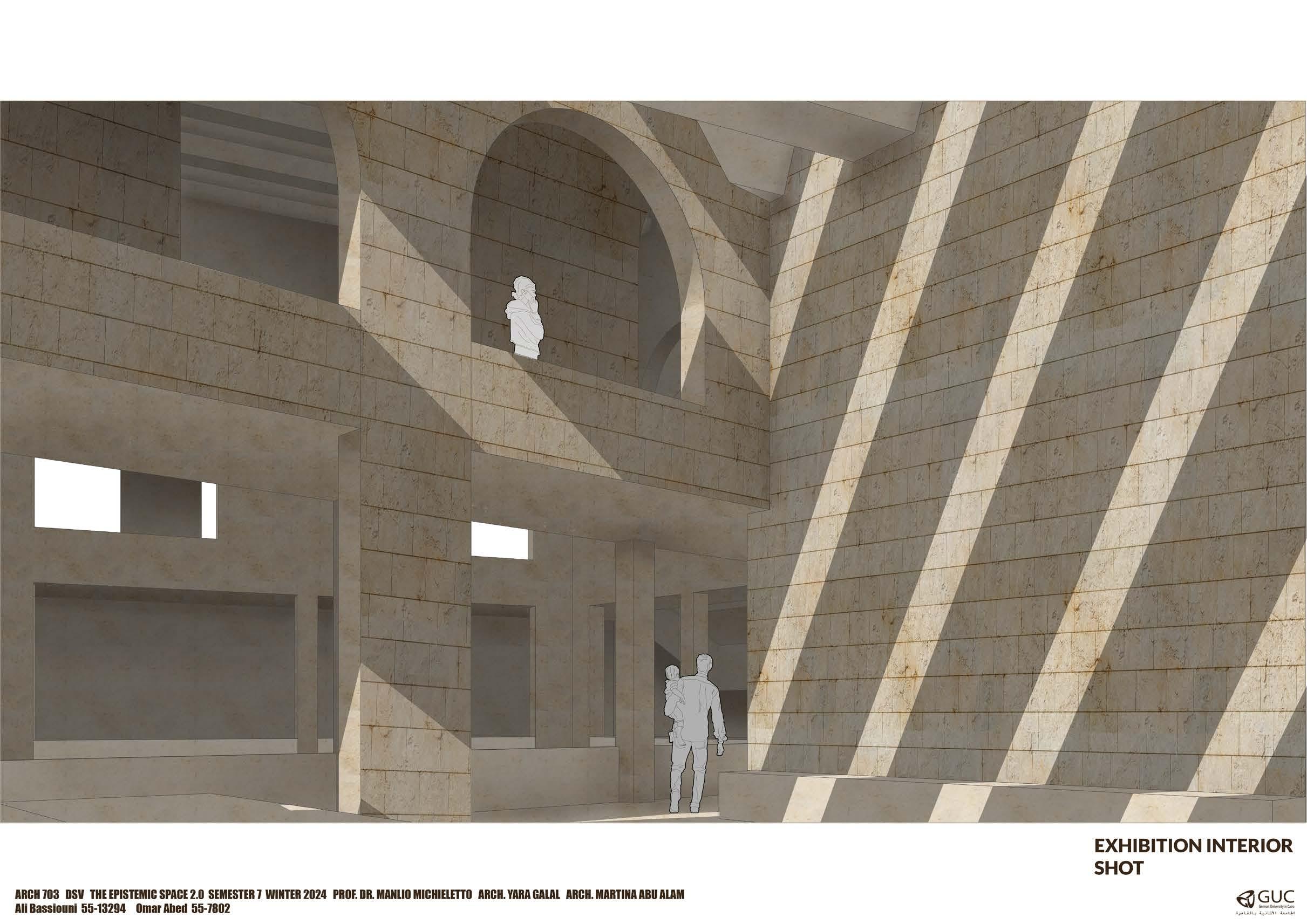

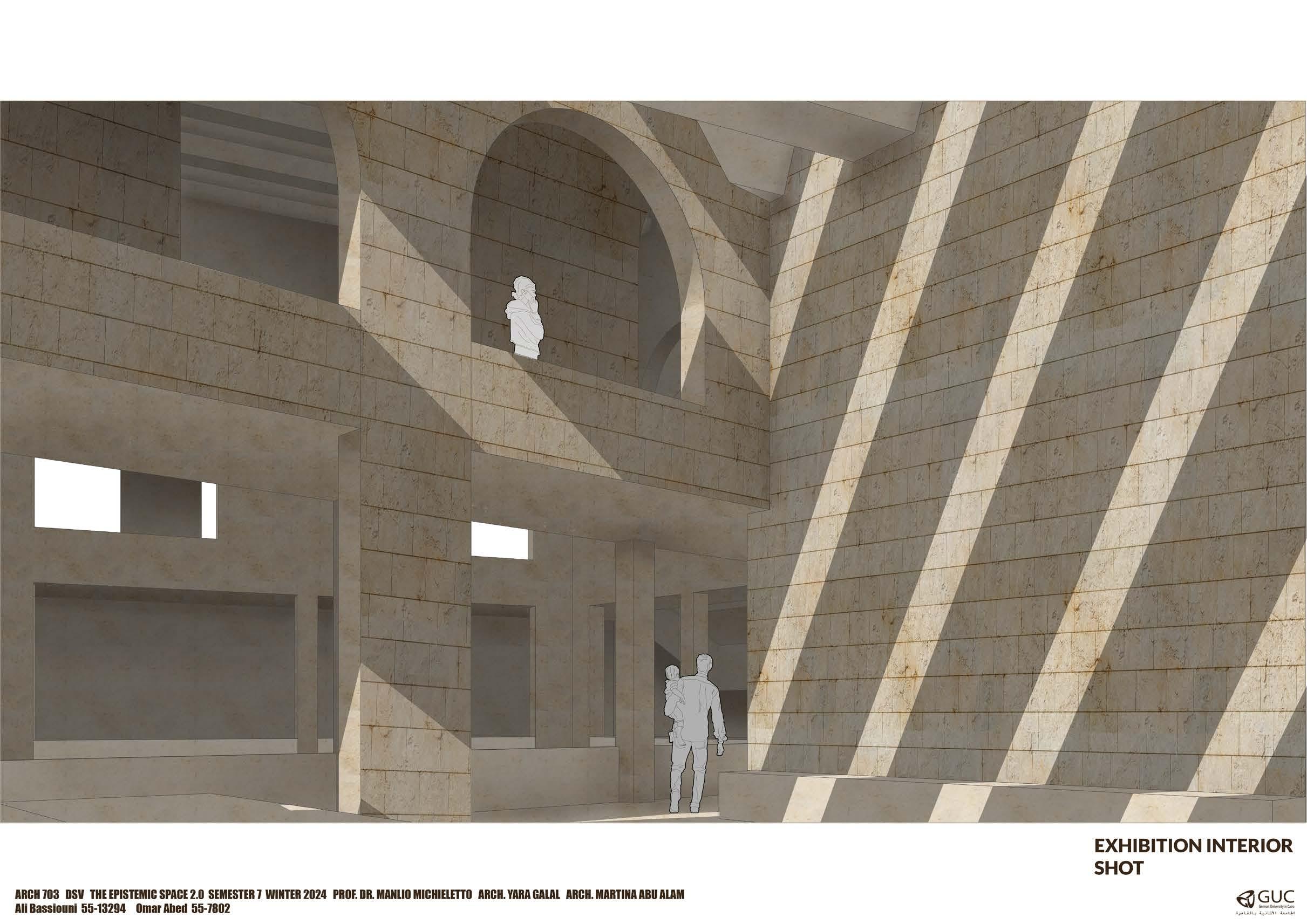

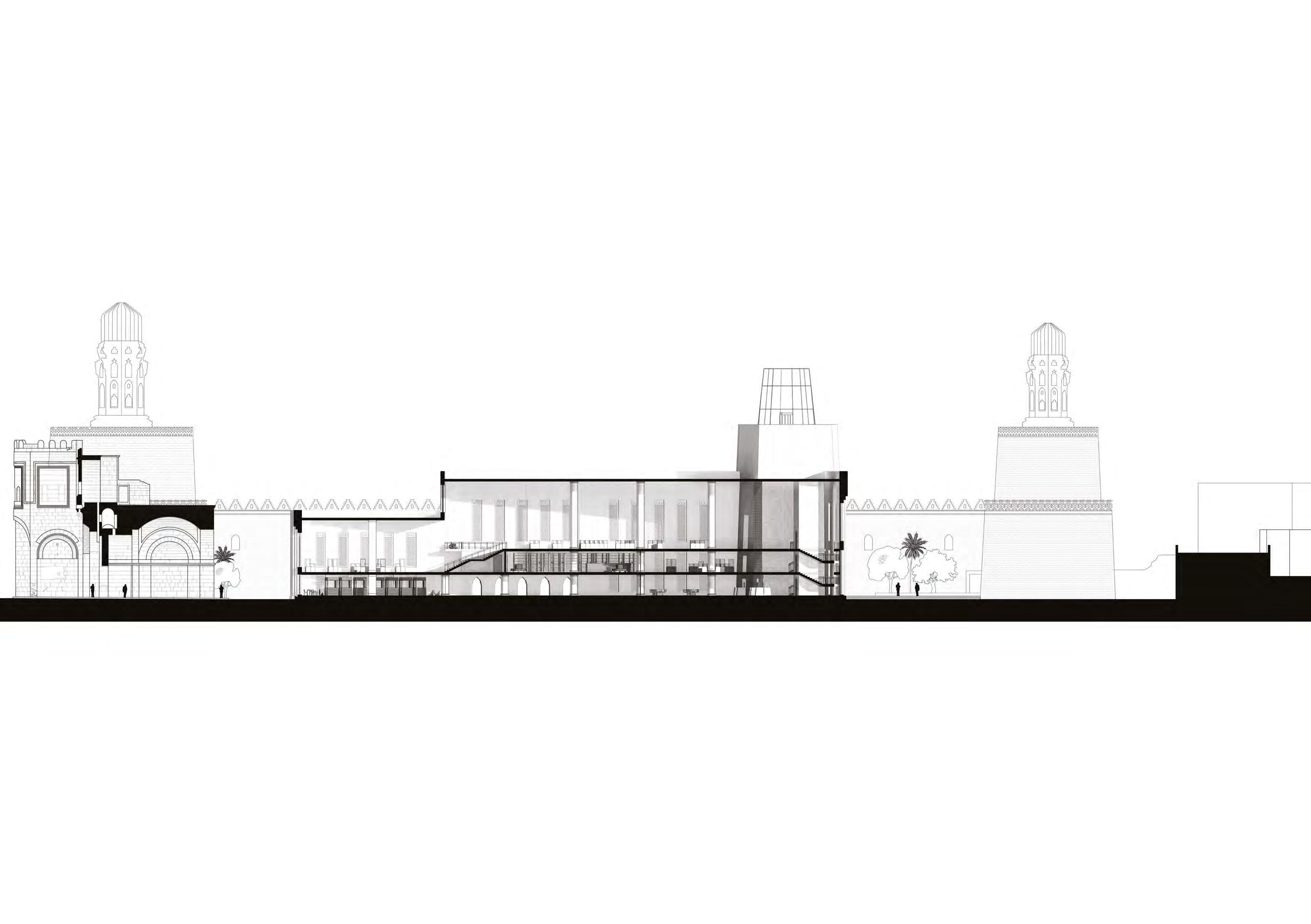

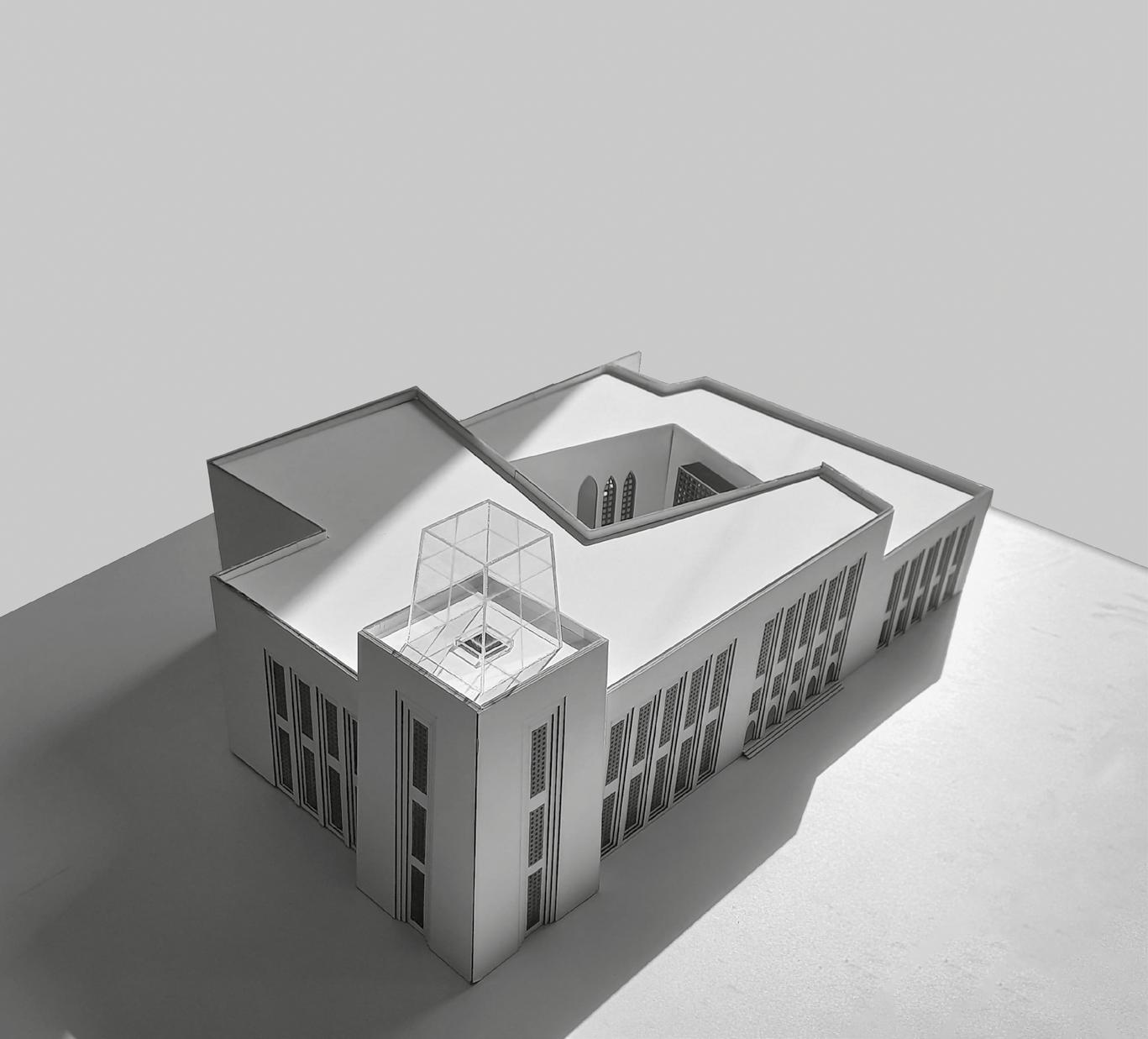

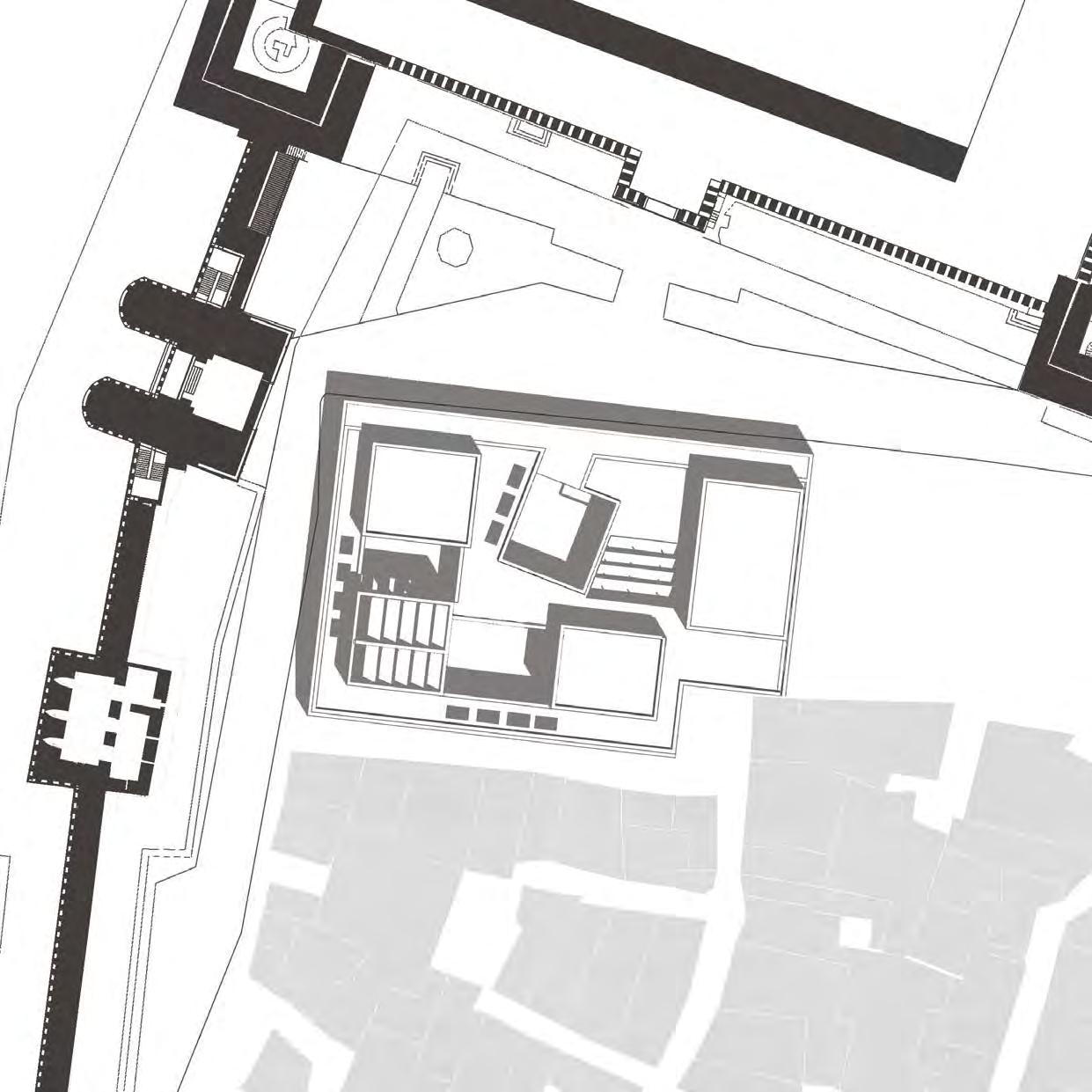

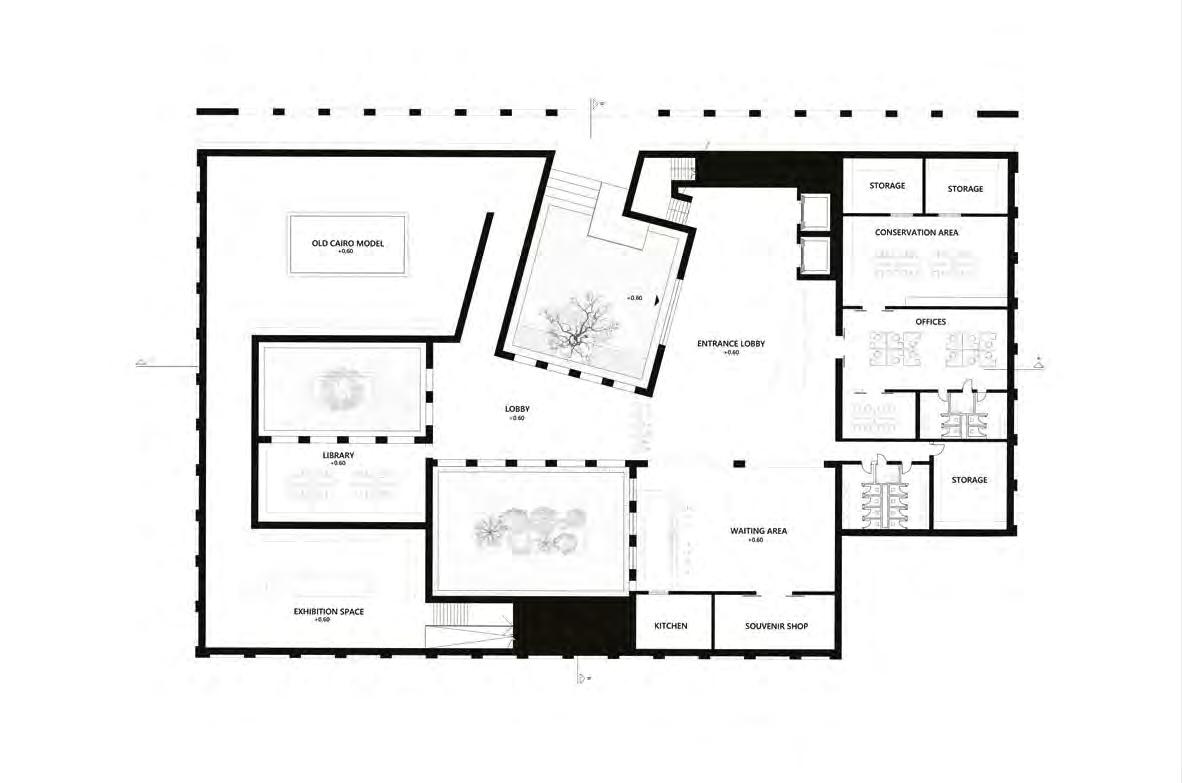

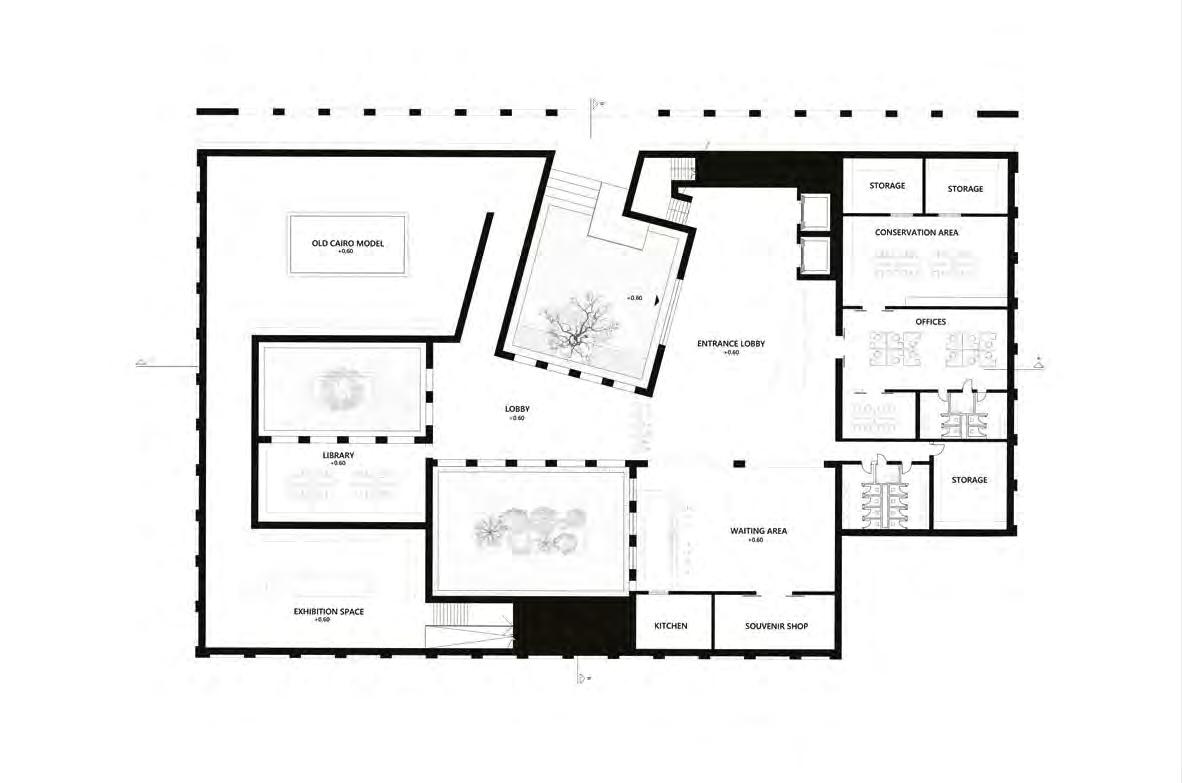

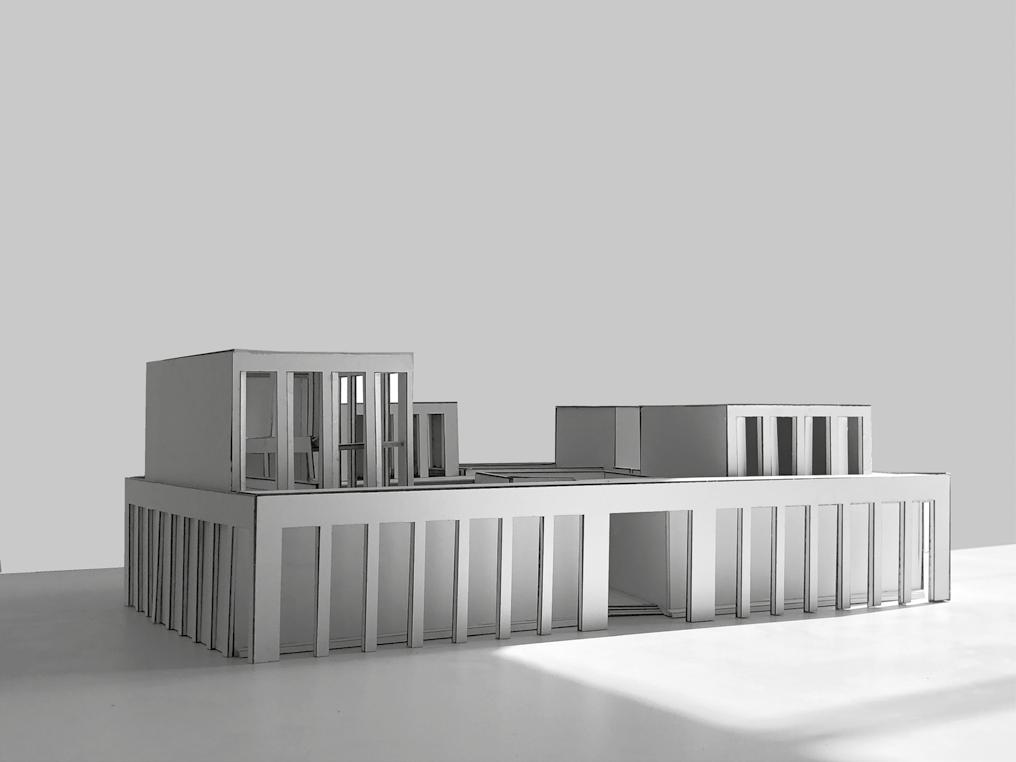

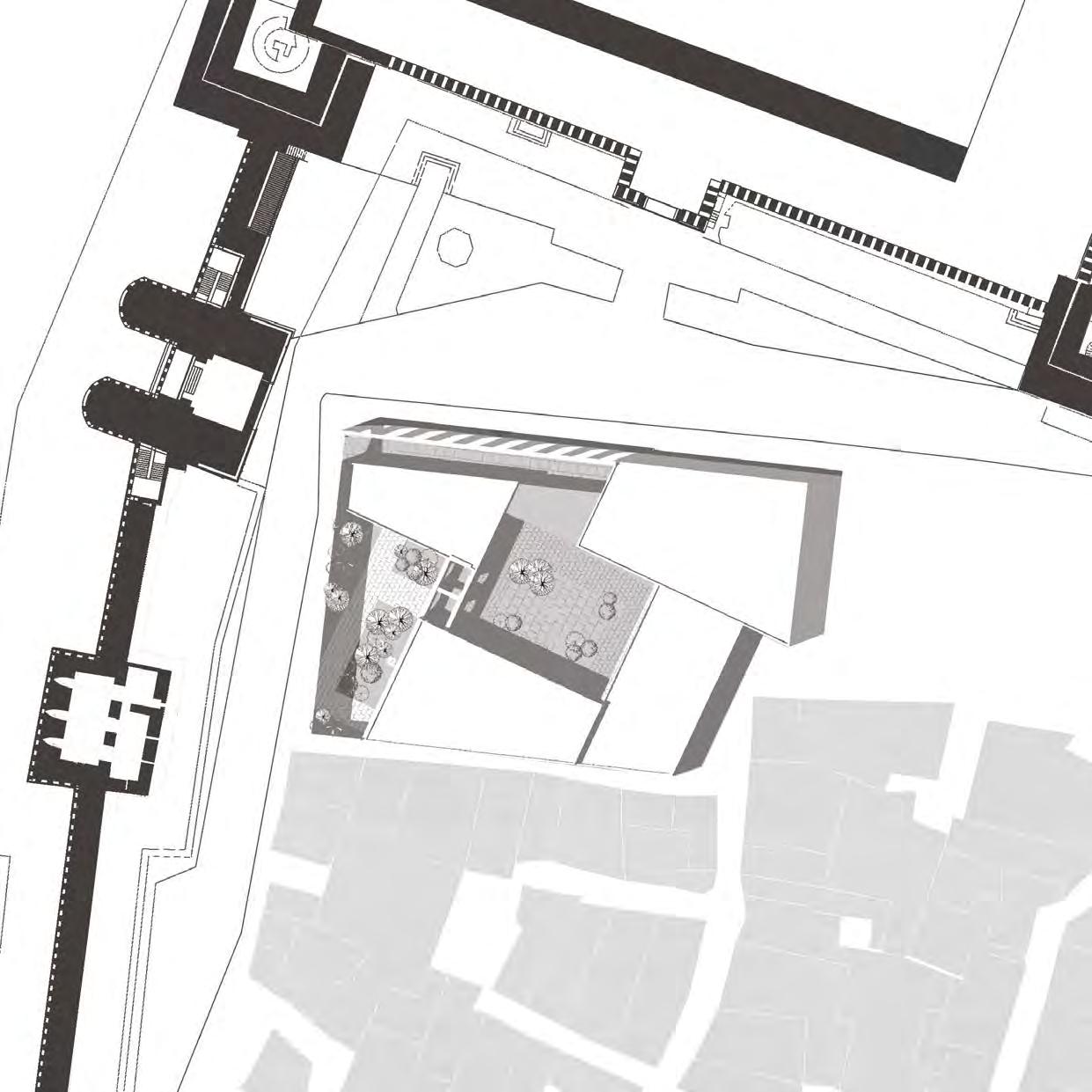

The museum is committed to showcasing a wide variety of historical periods in the city. The museum was designed around a central courtyard concept which provides a fluid assembly experience for visitors that takes them sequentially through various historical eras from the Fatimid period to the Mamluk period, and culminates in the main exhibition space with a very detailed model of historic Cairo. The layout also includes three main building masses that make up the way that people travel through the museum; they are designed as contiguous spaces with very open circulation.

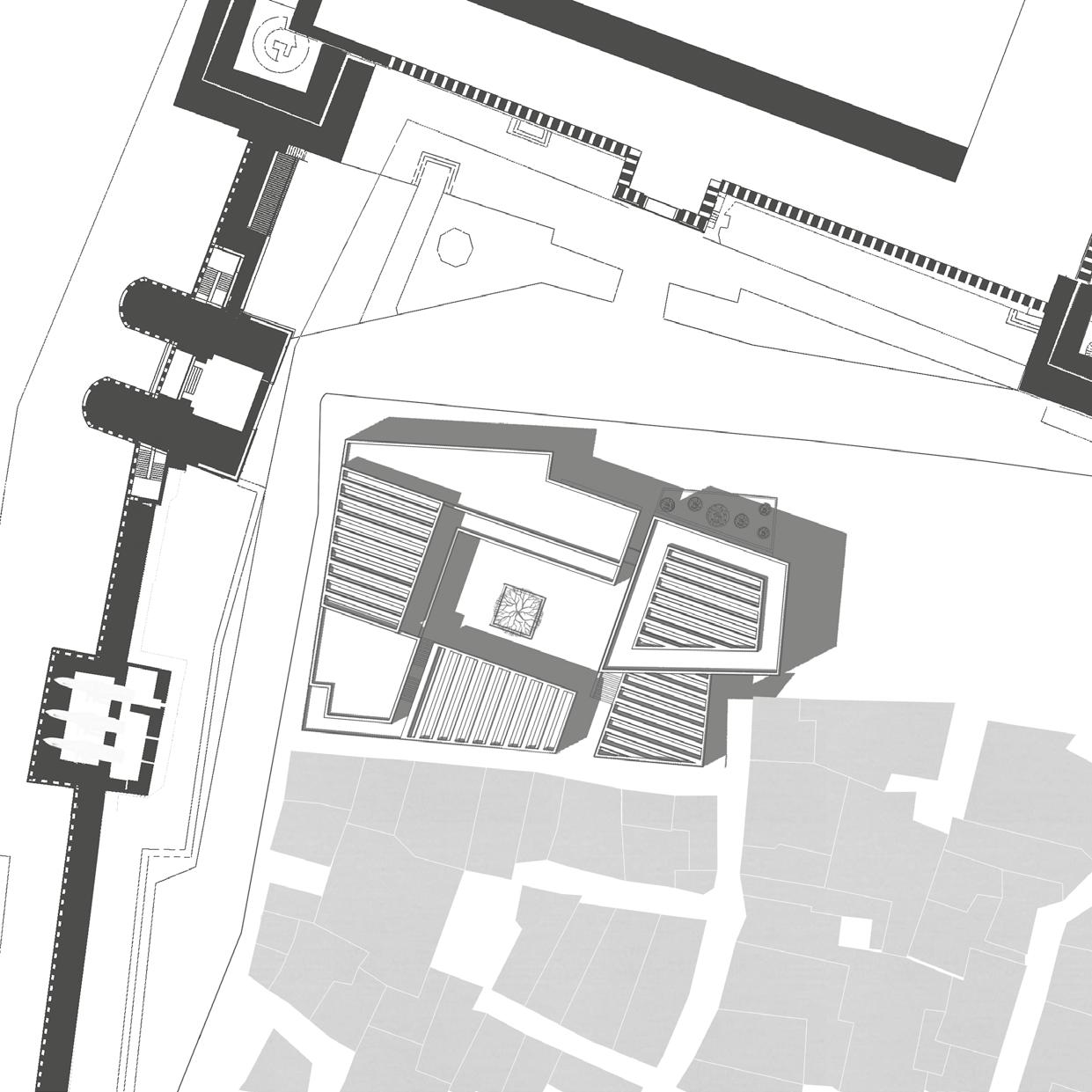

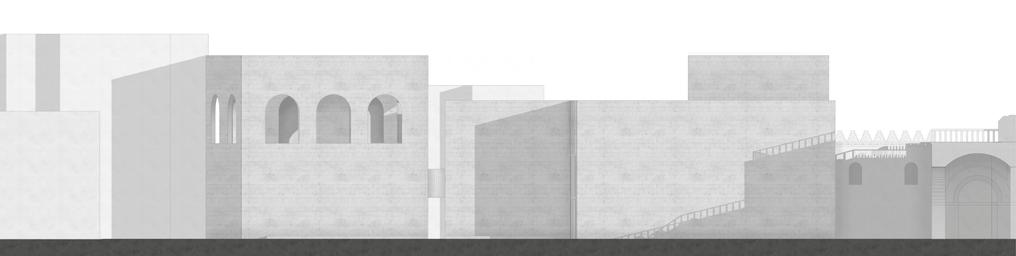

Figure (1) shown on the left page, site plan, outlining the museum’s organization around a central courtyard and three primary building masses.

Figure (2) shown above, floor plan, where open circulation and fluid spatial connections echo the character of historic bazaars. The layout supports a narrative flow through Cairo’s historical eras, culminating in a model of the old city.

Figure (3) shown on the left page, central courtyard, the spatial and conceptual heart of the museum. Framed by the surrounding building masses.

Figure (4) shown above, a section illustrating how natural light is subtly introduced into the interior through carefully placed openings.

Figure (5) shown below, the physical model as a section showing division of spaces.

Figure (6) shown on the right page, the physical model placed in the context of the site and how it interacts with its surroudings.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space 2.0

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Martina Abu Alam

Student Nour Elashmawi

“The Journey” is a museum inspired by old Islamic architecture, especially old Islamic courtyard houses. The courtyard is oriented on the same axis as Al-Hakim Mosque in front of the site to make use of the shade and shadowing that will occur throughout the day. Simplified designs of mashrabiyas and rows of Islamic pointed arches have been used to promote circulation of air throughout the building. As the name suggests, the concept mainly wants the visitor to walk through the museum as if on a journey of exploring the past through multiple wide staircases wrapping around the building.

Figure (1) shown on the left page, the central courtyard, maximize natural shading throughout the day. The layout reveals a circulation-focused design, guiding visitors along a gradual vertical journey.

Figure (2) shown above, wide staircases to lead visitors through successive exhibition zones. Each level offers a unique spatial experience and access to the minaret.

Figure (5) shown above, perspective section of the museum, illustrating the visitor’s upward journey through wide staircases, past layered exhibitions, and toward the rooftop viewing point over AlMoezz Street.

Figure (6) shown on the right page, the interior atmosphere of the museum, where natural light, abstracted arches, and open staircases create a dynamic and immersive spatial experience.

Figure (7) shown below, the physical model placed in the context of the site and how it interacts with its surroudings.

Figure (8) shown on the right page, the physical model and how shadows interact with the architectural form.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space 2.0

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Martina Abu Alam

Students

Nouran Elshall

Jana Khaled

The museum’s core is a 10×10 meter model of the city that allows visitors to navigate and explore the city’s depth of history. In line with the centre of the museum, the project is composed of three courtyards, of which the entrance court is rotated relative to the angle of Al-Hakim Mosque. The architectural concept contrasts light and dark, solid and void, to lead the visitors through narrow and dark corridors into the exhibition hall that is lit with soft theatrical light. This narrative continues through several levels of the building and culminates in a vantage point in the last hall from which the visitor can view a panoramic landscape of Old Cairo.

Figure (1) shown on the left page, the site plan and its alignment with historic context through the rotated entrance courtyard. The three courtyards, guiding visitors through a dynamic journey of the museum.

Figure (2) shown above, the museum’s spacial organisation is inspired from Beit el Suhaymi’s mandaras placed around a central courtyard for ventilation and quality.

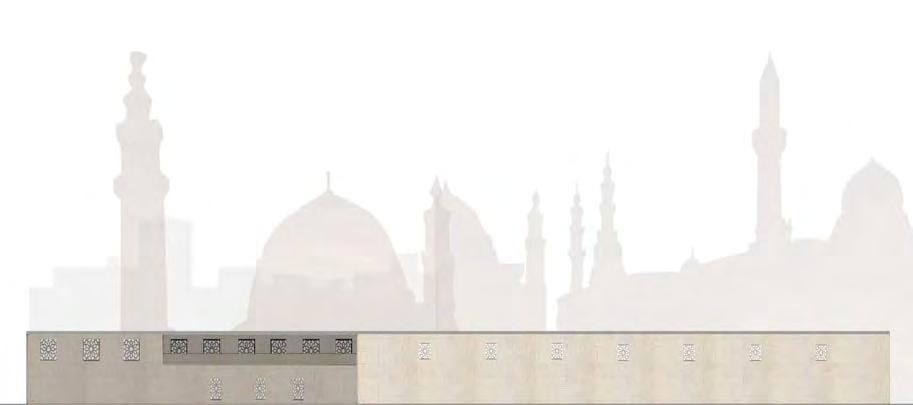

Figure (3) shown on the left page, elevations and facades are designed by replicating the same openings on a heavy wall, reflecting the architecture of massive exterior walls, such as El Hakim Mosque’s main entrance elevation.

Figure (4) shown above, visitor’s perspective going through Bab el Futuh narrow dark gate and to the open light museum corridor, framing the spontaneous scene of Muez Street.

Figure (5) shown below, the physical model and how shadows interact with the architectural form.

Figure (6) shown on the right page, the physical model placed in the context of the site and how it interacts with its surroudings.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space 2.0

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Martina Abu Alam

Student

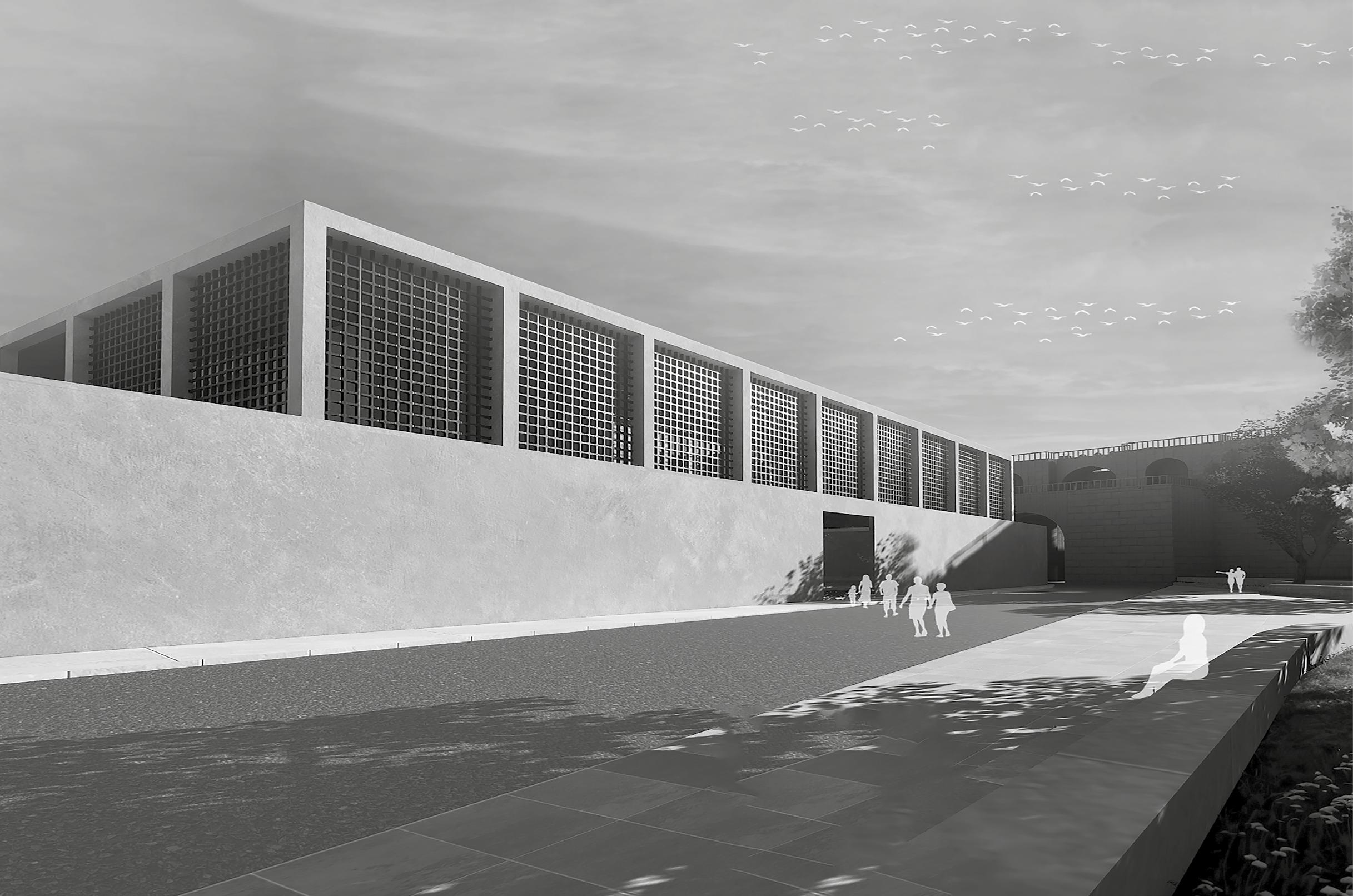

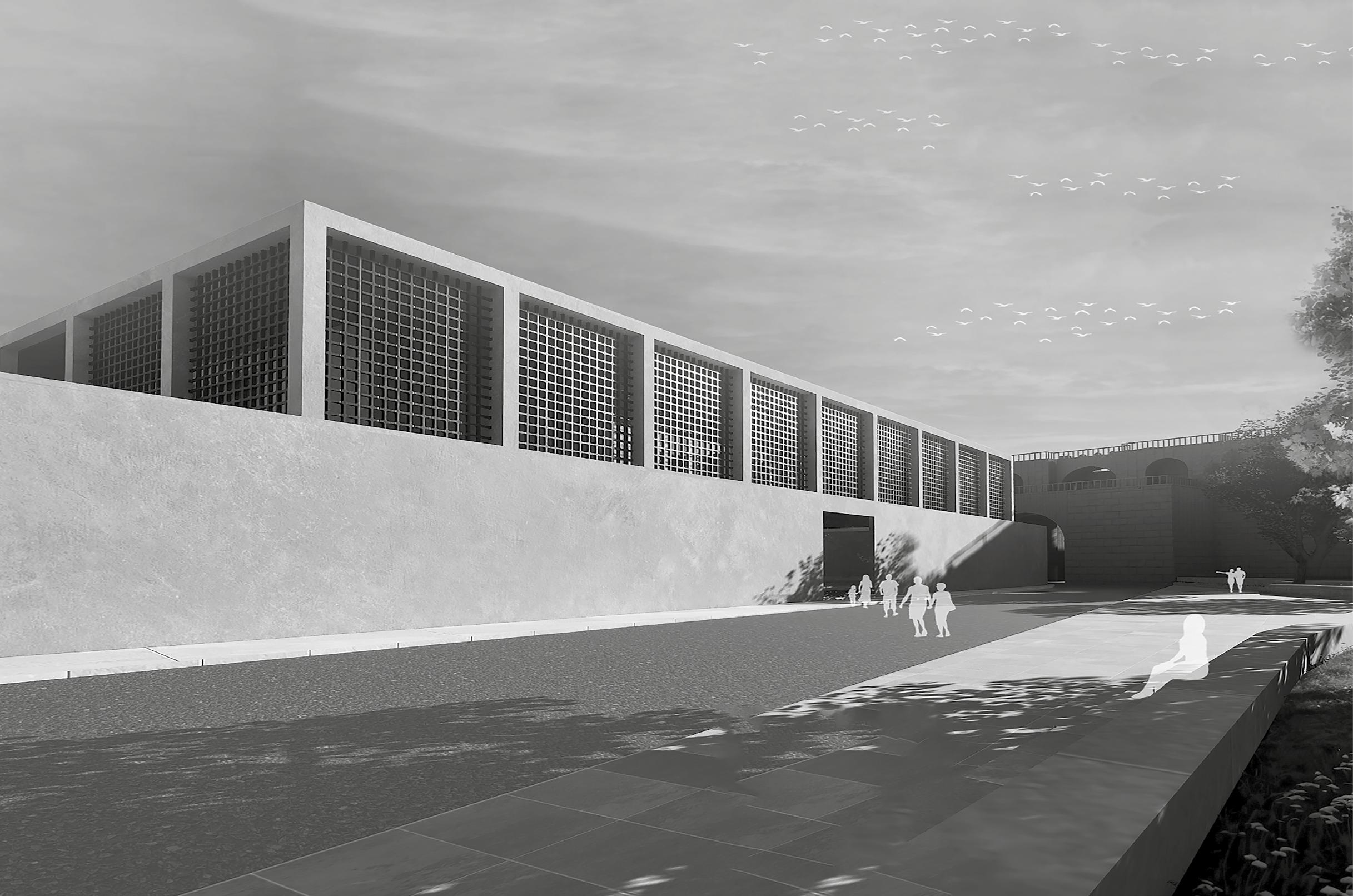

Mariam Alaa Eldeen

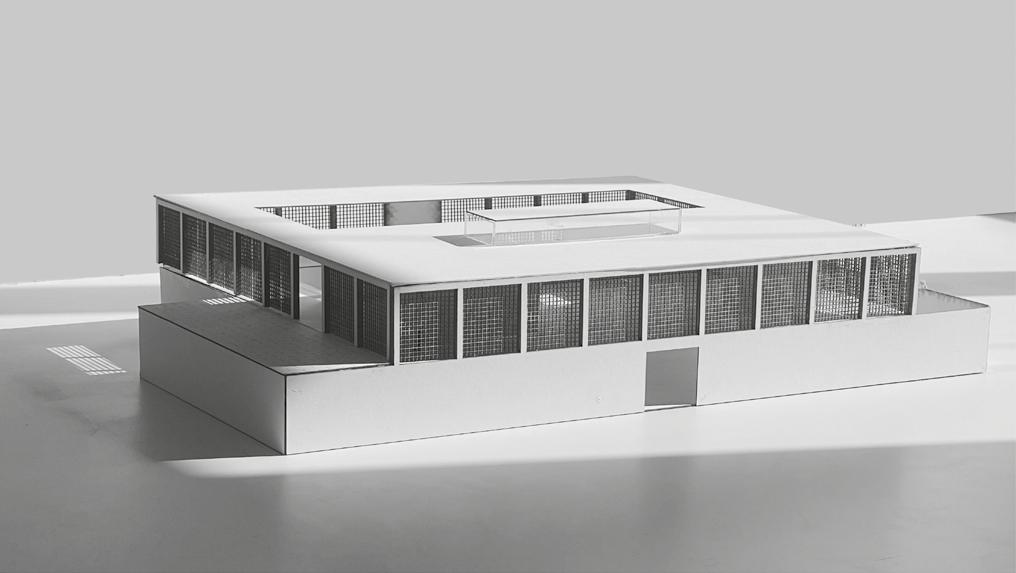

This concept was inspired by the style and culture of the House of Mostafa Gafer, which served as a primary case study, combined with elements from Al-Hakim Mosque. All of this is viewed through the minimalistic design style of Mies van der Rohe. The design mix es Cairo’s rich architectural history with a fresh, modern look. Central to this concept are the mashrabiyas, a traditional architectural feature that has been highlighted as a stand out element of the museum’s design.

Figure (1) shown on the left page. The site plan showing the concept of working with the context instead of against it.

Figure (2) shown above, The design approach focuses mainly on creating a comfortable sustainable environment, with masses that offer natural shadings and openings that allow ventilation.

Figure (3) shown on the left page, the idea of mashrabiyas were interpreted as a lightweight perforated cladding that works similar to the traditional mashrabiya. But it also allowed the creation of a 360 degrees panoramic view over the city.

Figure (4), shown above, as the daylight hits the perforated surface, visitors enjoy a dynamic play of light and shadow, often seen in old Cairo architecture, which transforms their experience throughout their movement inside the project.

Figure (5) shown below, the physical model and how shadows interact with the architectural form.

Figure (6) shown on the right page, the physical model placed in the context of the site and how it interacts with its surroudings.

Design Studio V

The Epistemic Space 2.0

Advisors

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Manlio Michieletto

Arch. Yara Galal

Arch. Martina Abu Alam

Students Nour Rateb Hana Hassaballah

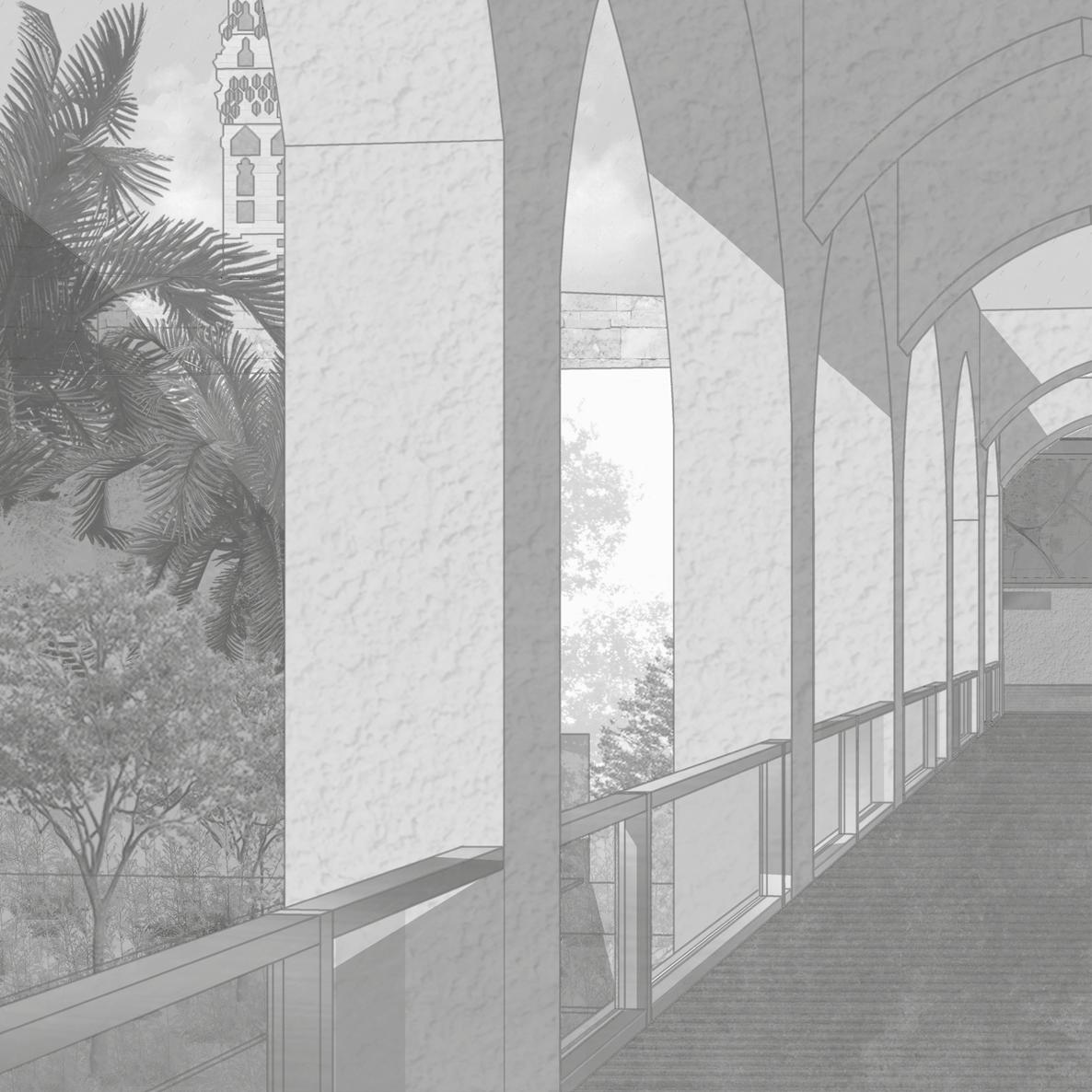

Crafting a journey of intrigue and exploration through selective visibility. Near Bab al-Futuh and Al-Hakim Mosque, arcades frame key views, drawing visitors inward. Controlled openings offer glimpses into the museum, sparking curiosity and guiding movement. A secret garden, partially visible from both the street and interior, remains inaccessible until the journey’s end. This interplay of concealment and revelation transforms the museum into an experience, one that invites discovery and deepens engagement with its historic surroundings.

Figure (1) shown on the left page, outlining a layered progression through enclosed spaces that culminates in a secluded garden.

Figure (2) shown above, A secret garden is subtly woven into the spatial narrative, partially visible but never fully accessible until the end of the journey, creating an irresistible pull toward the unknown, through movement and exploration.

Figure (3) shown on the left page, highlighting the integration of arcades along the key pathways offer controlled glimpses into significant spaces within the museum that allows visitors to see just enough to entice them further.

Figure (4) shown above, this interplay of visibility and restriction creates a sense of anticipation, transforming the journey through the museum into a continuous process of discovery.

Figure (5) shown below, the physical model as a section showing division of spaces.

Figure (6) shown on the right page, the physical model and how shadows interact with the architectural form.

THE EPISTEMIC SPACE

ARCH703

AA 2023/24

GUC German University in Cairo, Egypt

THE EPISTEMIC SPACE 2.0 ARCH703

AA 2024/25

GUC German University in Cairo, Egypt

Team

Associate Professor Dr. Manlio Michieletto (Design Studios Coordinator)

BSc Yara Galal

BSc Martina AbuAlam

BSc Nadeen Amged

Invited Professor Alberta Carandente

Participant Students

2023/24

Ahmed Gabr, Ali Tarek, Farida Shouman, Ghada Hossam, Habiba Riad, Jana Foda, John Faragalla, Jomana Sami, Karma El Antably, Lana Yossry, Lucia Ramses, Maria Nabil, Mariam Hendawy, Mariam Mohammad, Mariam Rumaieh, Marina Emil, Nelly Adel, Nourhan Abdullah, Passant Samir, Raheem Khaled, Rana Dakroury, Roaa Tawfik, Salma Hefnawi, Salma Ibrahim, Salma Moussa, Sarah Elkady, Yoanna Sameh

2024/25

Abdullah Aboelyazeed, Jumanah Shehatah, Abdelrahman Ahmed, Ahmed Mahran, Ali Abdelrahman, Mohamed Fahmy, Ali Bassiouni, Omar Abed, Ali Ibrahim, Ganna Eldessoki, Noureen Ali, Habiba Galaby, Nada Fahmy, Hana Hassaballah, Nour Hammad, Jana Rashwan, Nouran Elshall, Laila Elbatesh, Malak Said, Lilian Tadrous, Mirna Nabawy, Lina Seireg, Mahenda Mahmoud, Malak Abdelghany, Mariam Dewedar, Rwalin Elashry, Mariam Ramadan, Mariam Elkoush, Mariam Moharam, Merna Dimetry, Mathew Gondy, Nabil Aloraby, Youmna Elaidy, Nour Elashmawi, Omar Abdelhady, Omar Alrefaei, Rahma Salem, Sara Ahmed, Rana Elmamlouk, Rawan Hussein, Yara Khafagy, Zeina Eldeeb.

Manlio Michieletto

Manlio Michieletto is an associate professor at the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at the German University in Cairo. He holds a master’s in architecture and a PhD in architectural composition from the Iuav University of Venice. He has held teaching and research positions in various institutions in Europe and Africa. After being an assistant lecturer, he became an associate professor in the Democratic Republic of Congo from 2011 to 2016. After that, he was the Dean of the School of Architecture and the Built Environment of the University of Rwanda in Kigali. He also set his practice designing and implementing projects in Italy, Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda. He is supervising master’s and doctoral theses focused on modern and adaptive architecture. His latest research primarily investigates the city development process, adaptive architecture and architectural heritage in the sub-Saharan and Egyptian context.

Yara Galal

Yara Galal has been a teaching assistant in the Architecture and Urban Design Program since 2017. She worked on various courses, including Building Technology, Visual Design and Design Bachelor Studios. Yara’s primary experience and research focus on visual studies and their relation to space and architecture.

Nadeen Amged Elamir Tadros

Nadeen has been working in GUC since 2022. She has worked on various courses, such as Design Studios with different batches and Housing and Building Technology courses.

Martina AbuAlam

Martina AbuAlam is an architect, urban researcher, and graphic designer, working as a teaching assistant in the Architecture & Urban Design department at the German University in Cairo. She brings international experience in design, research, and visual communication, with a focus on participatory approaches and community-centered development.

Through the study of urban morphology and building typologies, students were able to develop an abacus of architectural details, which they reinterpreted using contemporary design strategies. The concept of a museum dedicated to the city of Cairo – one that narrates its evolution over time – is part of a broader effort to reappropriate the identity of the place. In this framework, the Old City of Cairo is not merely a backdrop, but a source of architectural material and inspiration. The analysis of the traditional Islamic house, religious buildings, and monumental structures was enriched by literary readings, particularly the Cairo Trilogy by Nobel Prize winner Naguib Mahfouz. His work gave voice to the city’s most profound and most intriguing genius loci, offering an atmospheric and humanistic counterpoint to the spatial studies.

ARCH703 Design Studio V

“The Epistemic Space. Towards the next heritage. Museum projects in Old Cairo” AA 2023/24

“The Epistemic Space 2.0. Towards the next heritage. Museum projects in Old Cairo” AA 2024/25