Gentrification and Sustainable Urban Development in Hong Kong

LI Yu Sum

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bachelor of Arts (Hons) Architecture of School of Architecture and the Built Environment University of Lincoln

Lincoln School of Architecture and the Built Environment

Cover Sheet for Dissertation

Candidate Student ID: 207163294 (SHAPE) / 20791381 (Lincoln)

Module Code: ARC3001M

Department: Lincoln School of Architecture and Built Environment

Title of Module: Research Projects

Studio Group: Tutor/ Supervisor: Dr. Primali Paranagamage / Jo Lo

Date Summitted: 08-03-2021 Word Count: 10811 words (content)

Declaration: I declared that this dissertation contains no examples of misconduct, such as plagiarism, collusion, or fabrication of results, and has not previously summitted elsewhere.

STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY

I, LI Yu Sum, certify that:

This dissertation is an original and indivdual piece of work and contains the work of no other person.

I also declared that this dissertation has not been submitted elsewhere for the fulfillment of other qualification.

This statement is made in full understanding that, disciplinary penalty will be recieved if the statement is found to be false.

Signature : Date : 08-03-2021

ABSTRACT

Urban renewal is an important method to prevent urban decay. Both traditional gentrification and unban redevelopment are the methods adpopted by the Hong Kong. In this essay, urban renewal project by these two methods would be analysed and compared in architectural and social perspective. The essay aim to find out which model could achieve a more sustainable urban development. A mixed mode of urban renewal is suggested in the conclusion.

Keywords: gentrification, urban renewal, sustainability, architecture

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Statement of originality

Abstract Chapter 1 Introduction

Background Aim, Objectives and Significance of study

Methodology

Chapter 2 Literature Review

Definition of gentrification and urban redevelopment

Gentrification and its situation in Hong Kong

Urban Redevelopment and its situation in Hong Kong

Chapter 3 Case Studies

Case 1 – Lan Kwai Fong – gentrification example

Case 2 – Langham Place – urban redevelopment example

Chapter 4 Discussion Conclusion Reference

List of Illustration

Introduction

Urban renewal prevents urban decay and maintains a livable environment for the citizen (URA,2021). Urban redevelopment and private-owner-led gentrification are the main modes of urban renewal in Hong Kong.

In Hong Kong, urban redevelopment is always facilitated by Urban Renewal Authority (URA), set up by the government, with cooperation with developers. The scale of the redevelopment area is usually large involving several street blocks. Langham Place in Mongkok and The Avenue in Wan Chai are examples of urban redevelopment in the recent decade (La Grange, Pretorius, 2013).

The redevelopment projects had been accused of their brutality during land resumption with limited compensation to the residents. The neighborhood of the district was eradicated. The outcome of the redevelopment projects is also tending to be homogenized in terms of the type of shops and the building blocks typology (La Grange, Pretorius, 2013). The new residential flats provided were in high density, smaller in size with high cost (Tang, 2017).

On the other hand, the traditional way of gentrification also raises the awareness of the public. Social activists have warned that the consequences that will potentially be brought by gentrification after numerous of cafes invaded Tai Nam Street in Sham Shui Po including rising rent, disturbance to local culture and the gradual displacement of long-term residents (Poon, 2020).

Due to the fast-growing economy in Hong Kong, the living standard of the citizens are also rising. The old buildings are being replaced at a faster rate to meet the living requirement. With the limited land resources in Hong Kong, urban renewal is an unpreventable issue (La Grange, Pretorius, 2013).

Chapter

1

When urban renewal is mandatory in our city, but both urban redevlopment and gentrification also negatively impact the citizens, the following research questions are being derived in the study.

1. What impacts do both gentrification and urban redevelopment bring to the community?

2. When compared with the impacts of both models, which one is preferable to create a more sustainable urban environment? In social and architectural perspective.

If gentrification is preferable, 3. Could it be the counterforce against the hegemonic urban redevelopment?

1.1 Aim, Objectives, and Significance of the study

This dissertation focuses on the social and architectural sustainability of urban redevelopment and gentrification and determining which one is more beneficial to the community. The essay will also argue whether gentrification could be the counterforce against the redevelopment model from the government and the developers.

1.2 Research Methodology

Chapter 1 of the dissertation will explain how the argument is derived from the current Hong Kong situation. Chapter 2 would be a literature review on gentrification, urban development, including the causes, factors, and consequences to the community. The current situation in Hong Kong was also compared with the theory. Chapter 3 will be case studies of two urban renewal projects in Hong Kong, Lan Kwai Fong and Langham Place. The changes on the façade, street space and urban fabric will be studied. In Chapter 4, the parameters of the cases will be compared and analysed and determine their social and architectural sustainability. Moreover, the feasibility of gentrification as a counterforce to urban redevelopment would be discussed.

Literature Review

2.1 Definition of gentrification and urban redevelopment

“Gentrification” is an inductive term from a series of urban phenomenons. None of a theory has conclusively defined this term. Therefore, the definition of gentrification is yet to be exact, and it is varying according to time, places, and context. The definition of gentrification is debating vigorously within academia (Brown-Saracino, 2010).

Under the circumstance of not having a well-defined term of gentrification, the definition raised by Gina Perez would be adopted in this essay to facilitate practical discussion. Gina Perez (2004) definition has generally described most of the common characteristics of gentrification that had been agreed within the scholars.

“An economic and social process whereby private capital and individual homeowners and renters reinvest in fiscally neglected neighbourhood through housing rehabilitation loft conversions, and the construction of new housing stock. It is a gradual process, occurring one building or block at a time, slowly reconfiguring the neighbourhood landscape of consumption and residence by displacing poor and working-class residents unable to afford to live in ‘revitalized’ neighbourhoods.”

Some scholars considered refurbishment, new-builds and private sector blockbusting, urban renewal, and rural and suburban redevelopment as the typologies of gentrification (Ye, Vojnovic and Chen, 2015). In this article, only the prior two types would be considered as gentrification. The latter two always involve a radicle change of demographics and the process are usually not gradual.

Urban and suburban redevelopment displaced all the long-term residents, so they cannot experience the process, impacts and the consequence of gentrification. The redevelopment is totally leaded by state and developers, and middle class invasion is the consequence instead of the cause or process. Thus, it is not a pure natural urban phenomenon.

Chapter

2

Therefore, the redevelopment will be defined as:

“A large-scale clearance, unilateral taking of private property, and urban displacement led by the government with the use of ordinance, authority, and redevelop into new single, planned urban project with public capital or private investment.” – (Gotham,2001)

2.2 Gentrification and the current situation in Hong Kong

2.2.1.1 Factors contributing to gentrification

The factors that contributing to gentrification could mainly be separated into two sides, the production (supply) sides and the consumption (demand) side (Brown-Saracino, 2010).

The production side means the economic and political situation that promotes gentrification. For example, the cycle of disinvestment and reinvestment in the city and the new liberate government policy encourage free market capitalism (Harvey 1989; Peck 2006), deindustrialization and the development of the international service economy and free mortgage lending policy. The rent-gap hypothesis also stated that investors and gentrifies might also take advantage of the difference between current and potential ground rent (Smith, 1979).

The consumption side means the demand and preference of the consumers. The economy housing stocks, and policy would provide incentive for gentrification, but only if the demand of the gentrifiers exists (Gale 1979; Ley 1986). Those policy and incentive are responding to the demand of the gentrifiers. The most influential consumption factor is culture. When there is an ideological shift, say working-class shift, increasing interest in diversity and taste for historic properties, the gentrification is mostly related to the shift (Brown-Saracino, 2010). Some scholars point out that two contributing camps collaborate to form a market that driven the process of gentrification. Christopher Mele has mentioned the gentrification of New York East Village that the government and investors had built the first gentrifiers’ art scene and inducing the demand for the residents to gentrify their own district (BrownSaracino, 2010).

From the above information, the policymakers, politician, investors, developers, gentrifiers (mostly new middle-class) are contributing to the process. However, others also point out that media and financial institutions could also be participating (Brown-Saracino, 2010).

2.2.1.2 Factors contributing to gentrification in Hong Kong

The free-market economy and transformation towards a serviced-based economy since the 1970’s are the main driving force of gentrification in Hong Kong (Ye, Vojnovic and Chen, 2015). The liberate capitalist system with a low tax rate encourages the investors making a profit through revaluing of the properties by gentrification. The followed examples of the contributing factor are mostly related to the economic factor.

First, the tourism strategy promoted by the government. Hong Kong tourism is quite different from that in other parts of the world. It focuses on commercial activities such as retail and service industry instead of promoting local culture. Many shop owners take the opportunities to profit from the tourists and commencing various irrelevant stores with respect to the local residents. Those stores usually centralised in the tourists easily accessible urban area with shopping malls or stores. Causeway Bay, Tsim Sha Tsui, Mongkok, Shatin, Yuen Long and Sheung Shui are examples of this kind of gentrification. This kind of gentrification is also the most antagonistic with the local residents as most of the gentrified service usually incompatible with the daily needs of the residents, such as pharmacy, boutiques, jewellery stores etc.

Second, the relationship between the railway and the working class has demonstrated the collaboration of the production side and the consumption side. The fast pace of living style in Hong Kong and unsatisfactory traffic condition has driven the working class choosing the area around MTR stations for less commute time. While the government has put more effort to develop railway network, the government allows the MTR corporate to build their own property to compensate the exaggerate building and operation cost. Those properties are targeting the middle class with shopping malls to fulfilling the needs of the new residents. Although MTR properties are regarded as urban redevelopment that is not regard as gentrification in this article, the neighboring street blocks are also being gentrified by the expanding railway network. The obvious example would be Tai Wai, Western district and Tai Kok Tsui.

Third, the public housing properties policy of Hong Kong has allowed the gentrification of the public housing shopping mall. The public housing shopping mall originally belongs to the Hong Kong Housing Authority which the Hong Kong government directly governs. Due to the pause of selling of Home Ownership Scheme Flats in 2002 and the economic regression in 2003, the revenue of the authority had been greatly reduced. The housing authority has privatized the carpark and retails properties to ensure sustainable income for building public housing. As a result, to compete with other shopping malls in the market, those shopping malls have been renovated and the rent has skyrocketed and displaced numerous local retail stores.

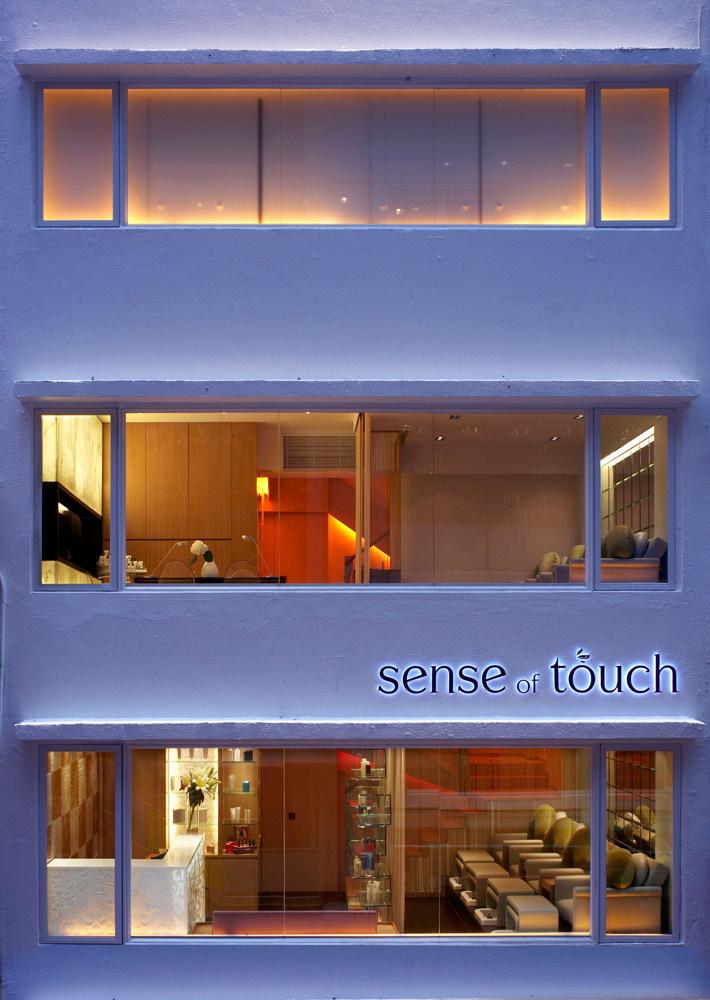

2.2.2.2 Gentrifiers in Hong Kong

Regarding the situation in Hong Kong, there are several examples of gentrifiers. First, part of the international workers would be significant gentrifiers. This group of workers are not born locally. They do not need to stick with their family, which allow them residential mobile. A large proportion of their daily routine is working in the company. The choice of their living place would prefer a minimum commute distance. Also, their living style is so different from that of most Hong Kong people, and they would tend to live in the same community. The district would be gentrified to cater for their alternative living style. The most explicit examples are the districts near the CBD of Hong Kong, such as Wan Chai, SOHO in central, Kennedy Town, Tai Ping Shan in Sheung Wan. There are more bars, café, international cuisine, salad bar, restaurants hiring foreigner as their staff which apparently not aiming to fulfil the needs of local residents.

Some gentrifiers that based on ideological reason in Hong Kong as well. Artists, craftsmen and “Art-loving hipster”. The prior two trying to seek places for working studio with cheap rent. They also try to gather their studio in the same district to provide mutual support such as sharing machinery, art and design ideas, holding exhibitions etc. Tai Ping Shan in Sheung Wan, Central mid-level districts are the examples of this kind of district, a lot of art galleries were opened. The setting up of art galleries also matched the living style of those international workers mentioned in previous paragraph, the upper middle-class that live at the mid-level district, which have amplified gentrification. The local residents that original living in this district has mostly displaced.

The “art-loving hipster” (文青) is a recent term that appeared in Hong Kong, which means a group of teenagers refusing mainstream culture and particularly like art and literature. These teenagers have adopted an alternative lifestyle such as spending an afternoon reading books in a café, joining art and craft workshop, and buying some Japanese or British-style pseudo-vintage fashion. This trending lifestyle has catalysed the formation of an “art-loving hipster” community such as Tai Nam Street in Sham Shui Po. The formation of this kind of community has already raised controversy in society. Although the local residents living in the districts still remain in place, the elevating rent of the retail stores has been pointed out as the precursor of the gentrification process.

2.2.3 Consequence of Gentrification

There are several signs and traits to recognize gentrification, such as preserved streetscape with high-end bistros, historically preserved homes, health food store etc., which are some explicit signifiers. Moreover, some implicit signs appear, such as surging housing cost, demographic change, local politics change. There would be displacement, social tension or privatization of public space and transformation of buildings to some extent (BrownSaracino, 2010).

Apart from the observation could be found in a gentrified city. Most of the scholars are debating on the cost and benefit of gentrification. The benefit and the costs are not isolated. The main issue is who would benefit during the process and who will bear the cost of it. Most scholars agree that the process is mainly beneficial to the public, but these benefits would be a high cost paid by the long-term residents (Brown-Saracino, 2010).

For the public benefit, the tax revenues would be increased. The cultural and social amenities would be restored. These changes may lead to job creation and decrease the crime rate. Some of the districts may have an influx of “creative class”, which may lead to economic growth. The new middle-class living style would also boost the place reputation. The better design of public space also tries to solve the social isolation of the long-term resident and increase security (Brown-Saracino, 2010).

When it comes to the neighborhood level, the move-in of high cultural, social, and economic capital also improves the standard of neighbourhood institutions such as schools. The institution improvement is beneficial to both gentrifiers and longtime residents (Brown-Saracino, 2010).

Nonetheless, gentrification has changed the social and familial network, such as market, worshipping place, public space etc. These changes may cause the redevelopment of housing and displacement of local business. These changes may also lead to the displacement of long-term residents. The long-term residents may not remain until the benefit brought to the community (Brown-Saracino, 2010).

Moreover, the increase of the sense of safety may come from harming the long-term residents. The government may rely on the police to harass the poor and the residents to achieve a sense of safety (Brown-Saracino, 2010).

Though the gentrifiers are one of the driving forces of gentrifications, they are also benefited during the process. However, some scholars also pointed out that the gentrifiers could be the victim of the process if over-gentrification occur as the rent will keep surging until the earlier stage of gentrifiers cannot afford it (Brown-Saracino, 2010).

The consequence of the gentrification process would be the rising of property value and the influx of professionals, leading to physical displacement. Apart from the demographic and economic change, cultural conflict is one of the consequences as well. The long-term residents would feel a loss of local power and influence on the district. The scholars also suggested that people with less social resources, such as poor, elderly, ethnic minorities, would be the most susceptible to the negative consequences (Brown-Saracino, 2010).

2.3 Redevelopment and the situation in Hong Kong

2.3.1 Factor contributing to urban redevelopment

Several factors that facilitate the model of redevelopment in Hong Kong. First of all, the extensive power of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government with the help of Urban Renewal Authority (URA). The strong power of the authority allows the government to take the leading role in large scale urban redevelopment projects (La Grange, Pretorius, 2013).

Second, the leasehold management system and the dependence on land-selling revenue as the main fiscal source to the government. The well-developed social welfare system in Hong Kong has contributed almost half of the government budget. The significant expense in social service with a low tax rate leads to heavy dependence on land-selling revenue. Therefore, redevelopment in the urban area can ensure a sustainable land supply, thus a sustainable satisfactory financial income to the government (La Grange, Pretorius, 2013). The Hong Kong leasehold management system can ensure a continuous supply of land and its revenue. The land lease sold by the government is time-limited, which could be collected when the lease is expired. Apart from the time constraint, the government even have the right to terminate the lease for public use (La Grange, Pretorius,2013).

Third, compact and dense urban morphology. The average residential population density in Hong Kong is around 60,000 people/km2. The older inner-city area is even triple this density. The dense living environment can facilitate a vibrant urban economy by having a low-cost, efficient urban structure with highly accessible, efficient and low-cost public transportation. Unfortunately, the older urban inner areas are the most suitable site for this type of urban economy that containes most affordable housings in Hong Kong (La Grange, Pretorius, 2013).

Forth, short building age leads to fast depreciation of housing stocks. From the Developmental Bureau perspective, buildings with 30 years old are regarded as old buildings, over 50 years old are regarded as functionally obsolete or probably in need of demolition. Moreover, those old buildings were built in the time with relatively low-income society. Following with

several economic changes in Hong Kong, the society has become wealthier. The old building living quality cannot match with the development of housing preference. This causes the old buildings to become a source of affordable housings for the underprivileged group. Furthermore, many older buildings were built with low quality and management. The owners do not have enough money for maintenance. While some of the owners purchasing these properties due to the redevelopment potential, the disinvestment in those housing even accelerated the land resumption process (La Grange, Pretorius, 2013).

2.3.2 Redevelopment authority, ordinance

2.3.2.1 Urban Renewal Authority (URA)

The URA facilitates redevelopment with cooperation with the developers. URA claimed that they are more concerned about the displacement problems, including providing compensation to the affected residents, relocation plan and consulting the opinions from the residents. Until recent year, however, the URA tends to adopt developers’ more favourable model, acquiring large area of old housings and developed into a densely developed, large scale, gentrified urban building project (La Grange & Pretorius, 2013). Most of these projects are profitable, which have accused by the social activists.

2.3.2.2 Land (Compulsory Sale for Redevelopment) Ordinance (LCSR)

Due to the dispersed property right, the URA has faced difficulties acquiring vacant and rundown properties for redevelopment. Therefore, the LCSR Ordinance establishment enables the majority of owners (over 80% of housing units of the whole building) to initiate a sale by auction for the whole property (Cap.545 Land (Compulsory Sale For Redevelopment) Ordinance). After the launching of the LCSR, it raised a vigorous competition between developers, owners who are willing to sell their properties for compensation and the owners who wish to stay in the building before reaching the 80% threshold.

A notable passage in the law stated that the Tribunal should not make the compulsory sales order if most owners failed to prove the building age and maintenance condition is necessary for redevelopment (Cap.545 Land (Compulsory Sale For Redevelopment) Ordinance). Therefore, the building maintenance status, property’s value would be a great bargaining power for preserving the building.

2.3.2.3 Land Resumption Ordinance (LR)

Land resumption Ordinance is a more powerful ordinance than LCSR. The LR does not require the acquisition of a certain proportion of property ownership. The government can decide to reclaim any land with a) insanitary property;

b) any buildings which interfere with ventilation or threaten other buildings habitation condition (safety and health); c) any other public purpose decided by the Chief Executive and in Council (Cap. 124 Land Resumption Ordinance).

The definition of “other public purpose” is not well defined by the government. Most of the lands are susceptible to this ordinance. However, the property maintenance status is also a pivotal factor to resist the power of the ordinance.

In concluding the redevelopment situation in Hong Kong, the government has almost unlimited power to eradicate old building blocks and its community in terms of authority and financially. Numerous old building blocks concentrated on inner urban area. This area contains many fiscal incentives for the government and developers, which also serve as a reservoir of affordable housings, small local shops, small scale industry at the same time. It would be interesting to investigate if the benefits bought by gentrification could counteract the authorities.

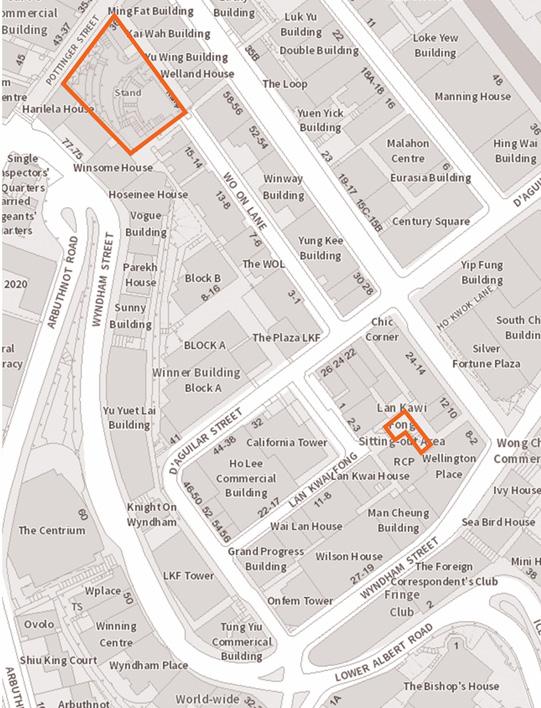

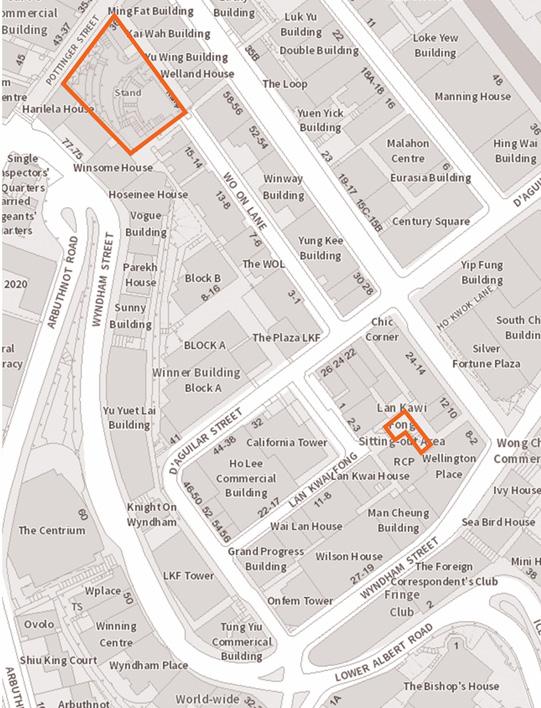

D’AguilarStreet PottingerStreet WoOn Lane WingWahLane WellingtonStreet WyndhamStreet Wyndham Street LanKwaiFong

1 Figure -ground Diagram of

Kwai Fong Area

Fig.

Lan

Case Studies

3.1 Lan Kwai Fong

Historical development of Lan Kwai Fong

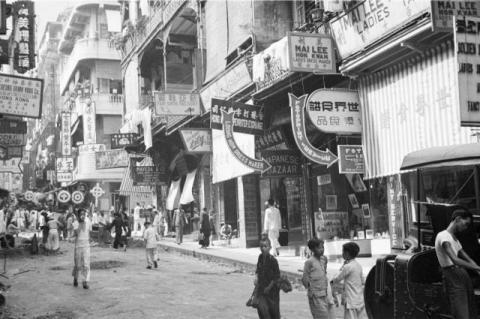

The historical development of Lan Kwai Fong is a very typical case of gentrification from a grassroots residential area to an icon of cosmopolitan consumption.

Lan Kwai Fong was a place for prostitution between the 19th century to early 20th century. In the 1950s, the prostitution business vanished, and this area is mainly residential. After ten years, the first wave of gentrification took place in Lan Kwai Fong, several blocks of wooden buildings were rebuilt, and some trendy tailor shops and carpet shops moved in after the reconstruction (Matthews and Lui, 2001).

After that, Disco Disco was set up at D’Aguila street in 1978. The disco has provided an alternative for people to dance other than hotel restaurants or hotel bars. The setting up of Disco Disco had dragged in people from different social class and ethnicity, and sexual orientations (Matthews and Lui, 2001).

The gentrification continued to sprawl with the participation of Group 1997 and California Restaurants. Apart from disco, other related businesses such as fashion and fine dining were opened in the district, targeting expatriates with higher income. The districts had then attracted a group of artistic people, hairdressers and gay people to visit during the mid1980s. After 1980, Lan Kwai Fong had experienced several waves of gentrifiers replacements, from expatriates’ professionals to Chinese Yuppies with their business friends (Matthews and Lui, 2001).

The gentrification process had gentrified the consumption standard as well as the ‘taste’ of the district. Many shops have been expelled out of the district because of the surging rent. The existing buildings were either renovated or rebuilt to commercial buildings to suit the needs of higher-class eateries (Matthews and Lui, 2001).

Chapter 3

a. Urban Fabric

The urban fabric of Lan Kwai Fong was established in the 19th Century. There is no significant change in the urban fabric over 132 years even gentrification occurred several times (Fig.2-6).

The Lan Kwai Fong Area is bounded by D’Aguilar Street, Wellington Street, and Wyndham Street, with a distinct L-shape Lan Kwai Fong, diverted from D’Aguilar Street. Wo On Lane and Wing Wah Lane are also included in the district.

Although the building mass of each buildings neighbouring Lan Kwai Fong has been increased, the street network organization even some back alley has been preserved during the gentrification.

Fig. 2-6 Urban Fabric of Lan Kwai Fong and surrounding area in a) 1889 b) 1945 c) 1975 d) 1983 e) 2021

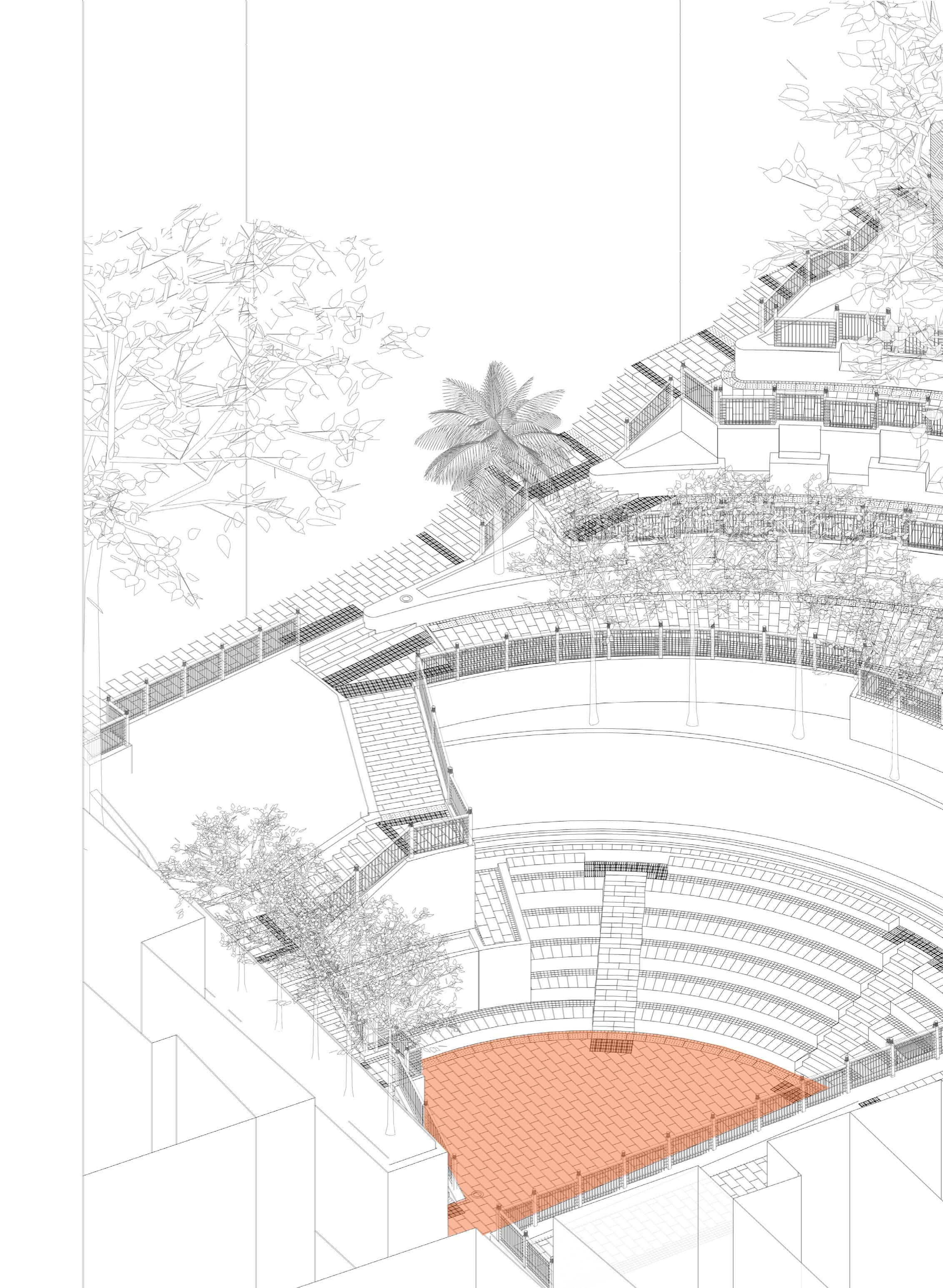

b. Public Space

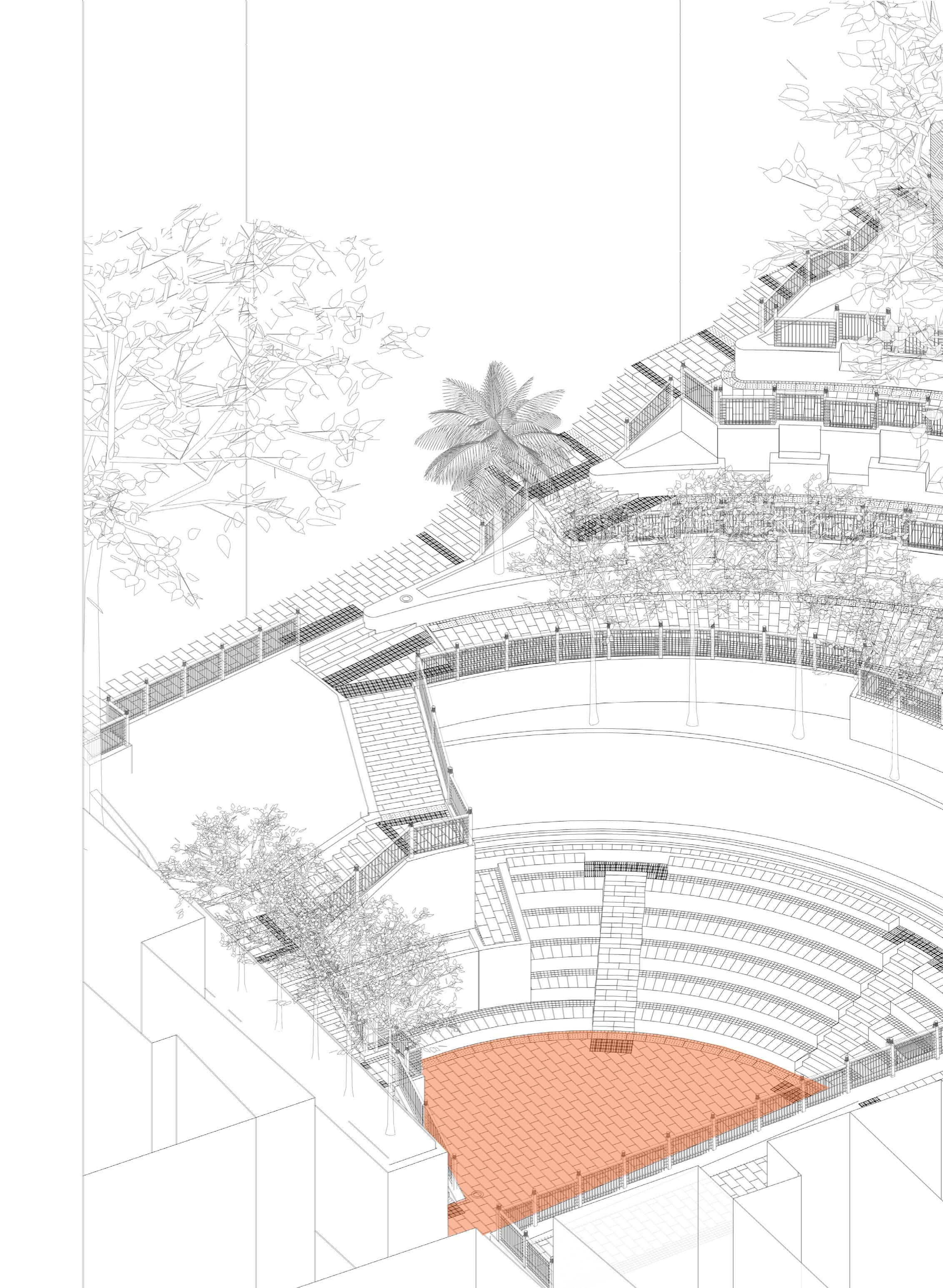

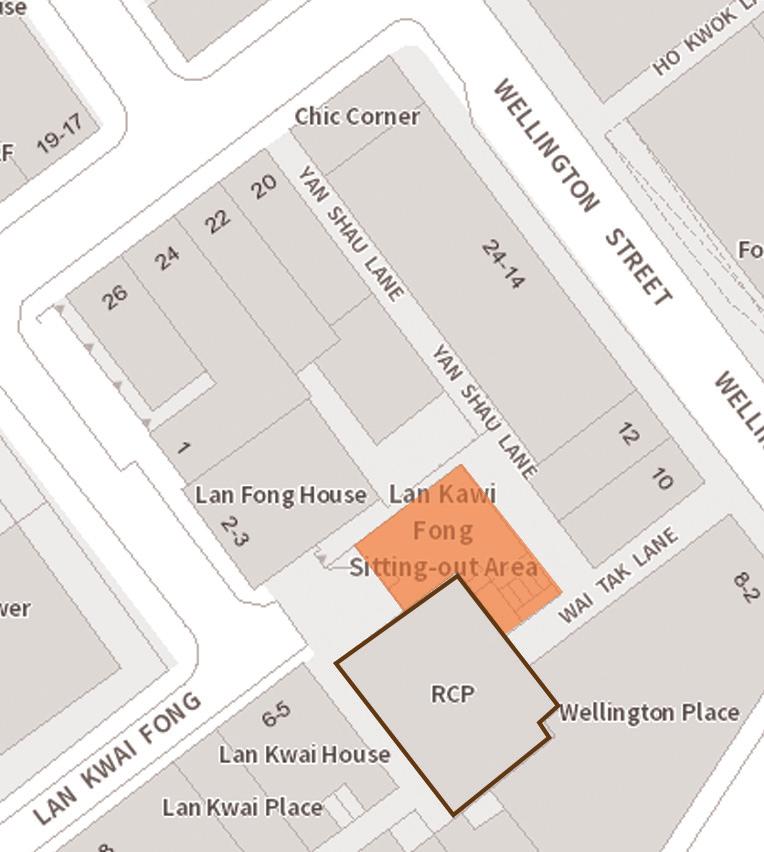

The gentrification would improve the quality of social amenities. The improved quality of public space is one of the examples (Brown-Saracino, 2010). There are two official public spaces in Lan Kwai Fong (Fig.7) , Lan Kwai Fong Amphitheater and Lan Kwai Fong Sitting Out Area.

Fig. 7 Location of Lan Kwai Fong’s public space

PottingerStreet

WellingtonStreet

Fig. 8 Wo On Lane in 1983

PottingerStreet

Fig. 11 Wo On Lane in 2021

WellingtonStreet

Lok Hing Lane Sitting Out Area

Back Alley to Wellington Street

Fig. 9 Wo On Lane dead-end in 1997

Fig. 10 After the Lan Kwai Fong amphitheater had established in 2001, some affordable retail shops were still remaining in the lane.

Lan Kwai Fong Amphitheatre

Slope that disconnect the sitting out area and Wo On Lane Bars and restaurants

Fig. 12 Wo On Lane with a lot of restaurants in 2021

和安里 WoOnLane 和安里 WoOnLane

The Lan Kwai Fong Amphitheater is a more robust public space. The public space connects Pottinger Street and Wo On Lane. Wo On Lane originally was a dead-end lane connected to D’Aguilar Street (Fig. 8-9). The shops in Wo On Lane initially were some affordable restaurants, fruit hawkers and domestic engineering companies. Those shops are more related to residents’ living (Fig 10).

After the Lan Kwai Fong amphitheatre was established in 2001, some affordable retail shops were still remained in the lane (Fig 10).

In 2001, the government set up the Lan Kwai Fong Amphitheatre, and it became a node of the district (Fig.11). Bars and high-ended restaurants had sprawl to the end of Wo On Lane (Fig.12), drinkers from both Pottinger Street, Wo On Lane, and Lan Kwai Fong will gather in the amphitheatre (Fig 13).

The Lan Kwai Fong amphitheatre is managed by the government. The public has great freedom to gather and held a wide range of activities without prior approval (Except for large cultural events held by an organization) (LCSD, 2018). The public space design also flavoured different scale of activities and different groups of users in the district.

Fig. 14 Drinkers gathered at Lan Kwai Fong Amphitheatre

Fig. 13 Community events for local residents

Fig. 14 Drinkers gathered at Lan Kwai Fong Amphitheatre

Fig. 13 Community events for local residents

The increased the public space footprint allowed a greater scale of events to be held in the public space. The cascading platforms with seating allow the audience to have a better view of the events, and the radial plan of the amphitheatre have made the performance space become a focal point (Fig.14).

Circulation

Wo On Lane

PottingerStreet

Large Flat area for performance or gathering Cascading Seating Pocket Seating

Pavillions providing shades

Fig 15. Axonometric Diagram of Lan Kwai Fong Amphitheatre

Fig 16. Pocket Seating in Lan Kwai Fong Amphitheatre

Fig 17. Domestic helpers and children using the pavilions

Fig 18. Children use as a playground

Fig 16. Pocket Seating in Lan Kwai Fong Amphitheatre

Fig 17. Domestic helpers and children using the pavilions

Fig 18. Children use as a playground

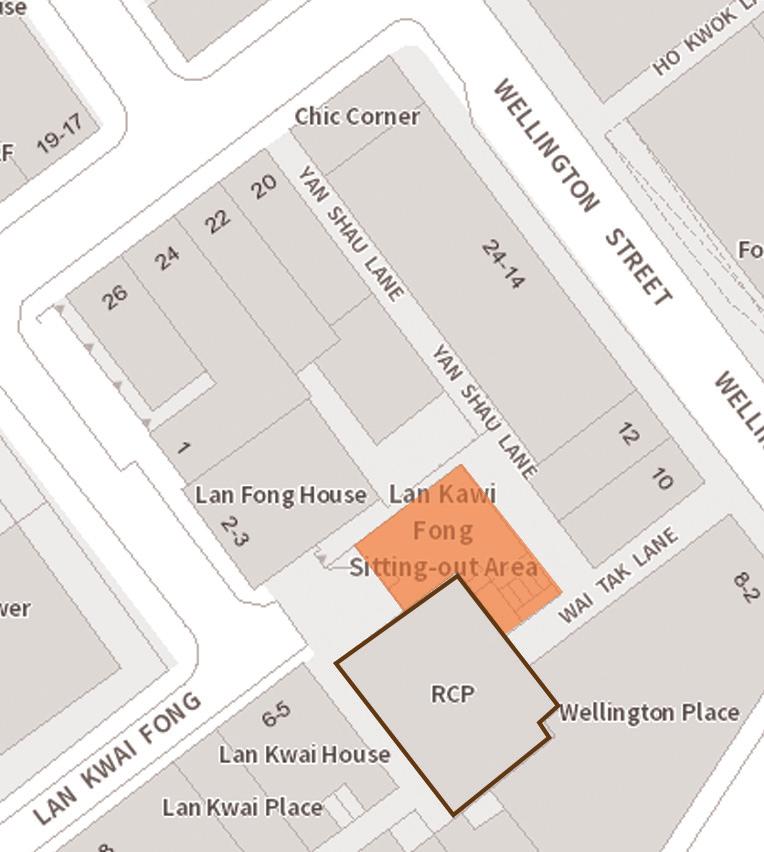

Lan Kwai Fong Sitting Out Area located at the centre of Lan Kwai Fong, which connected to Wellington Street and D’Aguilar Street through Wai Tak Lane and Yan Shau Lane respectively. Despite the convenience and the importance of the site, the planners had placed little attention on this public space.

Fig.22 Fig.21

Fig.23

Fig. 20 The entrance at Lan Kwai Fong of the sittingout area entrance is next to the refuse collection point

Fig.20

Fig19. Lan Kwai Fong Sitting Area and neighboring refuse collection point

Refuse Collection Point

Lan Kwai Fong Sittingout Area Lan Kwai Fong Public Toilet

CollectionRefusePoint 10 Wellington Street Wai Tak Lane Wellington Street

Fig. 21 Wai Tak Lane Entrance of the sitting-out area

Fig. 24 Diagrammatic Section of Lan Kwai Fong Sitting-Out Area

Fig. 22 Yan Shau Lane Entrance of the sitting-out area

Fig. 23 Lan Kwai Fong Public Toilet

The three entrances of the sitting-out area are not a welcoming space. Wai Tak Lane and Yan Shau Lane are dark and narrow back allies (Fig. 21 & 22). At the intersection of two back allies and under the public space is a public toilet (Fig. 23). They are hard to be notified by the pedestrian and feel unsafe to the residents, especially with bars and entertainment areas. The Lan Kwai Fong Entrance is just next to the refuse collecting point, which also gives an unwelcome, indecent and unhygienic sense (Fig. 20).

The site actually is the back of house of Lan Kwai Fong. The public space is a left-over space of the public toilet roof (Fig. 24). Though the public space quality is not satisfactory because it is originally a left-over space, the renovation and greenery are already a “bonus” brought by gentrification to improve the streetscape of Lan Kwai Fong.

Fig. 25. Environment of Lan Kwai Fong Sitting Out Area

Fig. 25. Environment of Lan Kwai Fong Sitting Out Area

c. Building program, typology, and façade

c.1. Building Programs

Lan Kwai Fong was a residential area in the 1950s. Nowadays, however, almost half of the residential buildings were replaced by commercial buildings. The remaining residential buildings are seldom owned by residents, which mostly rental flats. It is believed that most of the residents living in this area are not long-term residents. The original neighbourhood of this area had been mostly displaced. Apart from disrupting the neighbourhood network, the radicle changes of the building program also permanently decrease the residential capacity of the area. In the long run, the area will gradually be redeveloped into a commercial district. (Fig.26)

Commercial Residential Service Apartment

Fig. 26. Land use of Lan Kwai Fong and surrounding area

On the other hand, some office buildings are just renovated from an existing residential building to an office building. The mixed-use buildings provide flexibility for the buildings to totally or partially convert back to residential use, which maintains the residential capacity of the district. (Fig. 3) Although the mixed-mode renovation provides certain flexibility, the actual use of the buildings is still determined by the market.

For the hybrid use of buildings, the residential units had been elevated with multiple floors of commercial or retails floors. The increased commercial activities boosted the economy of the districts. The rent was increased due to the bloom. The establishment of full height commercial buildings even worsens the situation.

In addition, the hybrid mixing of commercial and residential use is beneficial to the district. According to Jane Jacobs (1992), a district with multiple primary uses could serve people with different schedule and purposes. This ensures the amenities in the district would be in full use. The office workers and residents would go to the restaurants in the daytime, and the outsiders and people from neighbouring commercial district would go to the bars at nighttime. It keeps the district operating 24 hours a day.

Fig. 27 Newly built commercial tower in Lan Kwai Fong

Fig. 28 Building that partially converted to commercial use

Fig. 27 Newly built commercial tower in Lan Kwai Fong

Fig. 28 Building that partially converted to commercial use

c2. Building Typology

The typology of the buildings is according to its program, as mentioned in the previous session. It also varies according to the building year. As the traditional gentrification does not involve the acquisition of the whole street blocks, the lands in each street block are still highly fragmented. When buildings with different programs and building year were assembled in the same street block, the building typology, as a result, also become diverse (Fig. 29-35).

The diverse building typology allows the district characteristic and particular architectural style to be preserved during gentrification. When looking at the change in building typology in the district, it is possible to understand how it will be developed throughout history. The record of the historical changes would become the collective memory of the long-term residents and finally strengthen their identity. The strong identity to the district would probably create a more vital neighbourhood and reduce the rate of displacement. Community sustainability was improved.

From an economic perspective, the mixing of new and old buildings in a district can accommodate shops with different yields. The gentrified high-ended fine dining restaurants are ideal for newly built commercial blocks and the ground floor of buildings. Simultaneously, the upper floor of old buildings provides affordable rent for low to medium-yield stores and some small-scale local stores (Jacobs, 1992). When local retail stores can survive in the district, it also reduced the rate of displacement of both shop owners and residents (Fig 36-47).

CALIFORNIA TOWER

HO LEE COMMERCIAL BUILDING

Building Year: 1977 No. of floors: 23

YAU SHUN BUILDING

Building Year: 1977 No. of floors: 12

Building Year: 2014 No. of floors: 27 52 D’AGUILAR STREET Building Year: 1978 No. of floors: 5

1 2 3 4 5 6 LAN KWAI

WYNDHAM

D’AGUILARSTREET 1 2 3 4 5 6 29 30 31 32 33 34 35

54 D’AGUILAR STREET Building Year: 1973 No. of floors: 6 JAZMIN CASA HOUSE Building Year: 1976 No. of floors: 5 Example of various building typology in Lan Kwai Fong

FONG

STREET

Carlifonia Tower Bulding year: 2014 Number of Floors: 27

Programs in New Building : Califonia Tower

Fig. 36 Fittness Centre

Fig. 37 Italian Cuisine

Fig. 38 Office

Fig. 39. Japanese Cuisine

Fig. 40 Nightclub

Fig. 41 Califonia Tower

Fig. 42 Steak Bar

5 Wo On Lane Bulding year: 1960 Number of Floors: 5

Programs in gentrified old buildings: 5 Wo On Lane

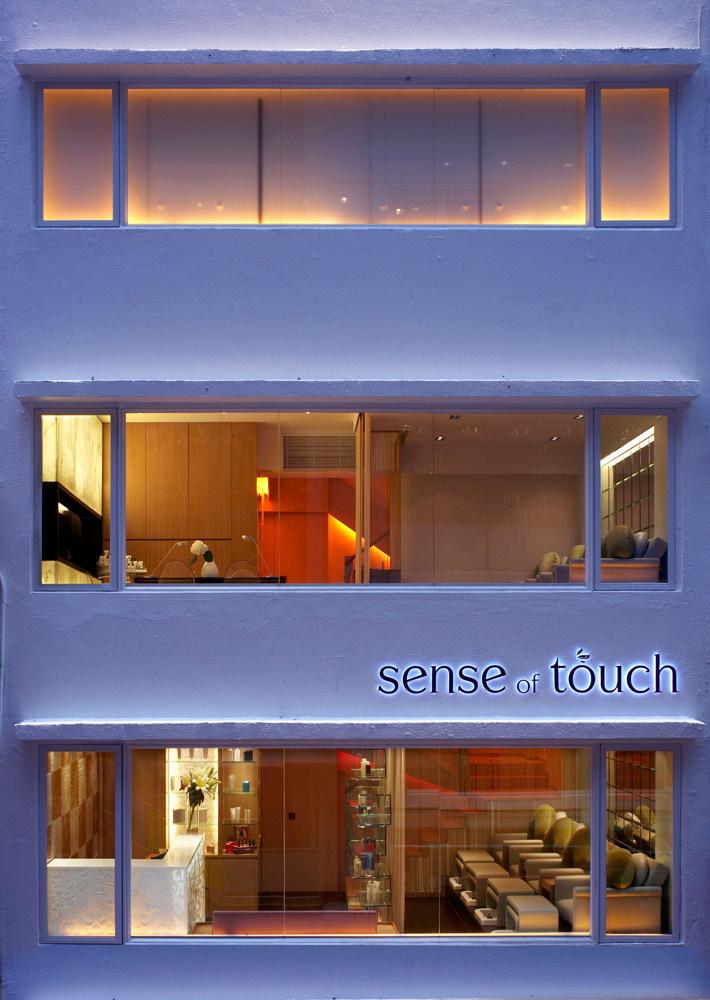

Fig. 43 Nail Care

Fig. 44 Man’s Beauty

Fig. 45 Interior Design Studio

Fig. 46 Hair Studio

Fig. 47 5 Wo On Lane

36

43 45 47 46 44 37 38 39 41 42 40

c3. Façade

The façade change is one of the signs of gentrification. During the gentrification during the 1940s to the 1970s, the building mass of Lan Kwai Fong are increased, which led to an increased floor area of the ground level stores (Fig. 48-49). The increasing floor area is directly exponential to the rent. The high rent is the prime cause of gentrification.

When comparing the elevation of the buildings in the 1940s and the 1970s, it is much privatized. The residents living activities had been internalized. The balconies of the residential units disappeared, and the windows are severely diminished. The shopfronts of the commercial floors are more emphasized.

The change has led to several consequences. First, the residents had more isolated from the street space. Second, the street space had been ‘purified’ by removing the chaotic living activities. Third, the street space is more flavoured to commercial activities, such as window shopping, street side bar and restaurants. Although human interaction is reduced sectionally, the ground floor activities are still preserved. When combining the second and the third point, the community image has been changed to a commercial image. This change led to the change of the dominant ideology of the whole district (Fig. 50-53).

Fig. 48 Small building mass in Lan Kwai Fong in 1955. (Left)

Fig. 49 Incresed building mass in Lan Kwai Fong in 1975. (Right)

Residential Residential Residential Residential

Commercial Commercial

Fig. 50 Expressive balcony from residential units in 1941 at D’Aguilar Street, Fig. 51. Diagram of street-to-unit interaction

Commercial Commercial Commercial Commercial

Fig. 52 Diminished windows and internalized residential unit in 1980s, Fig. 53. Diagram of street-to-unit interaction

During the 1970s to the 2020s, the gentrification continued, and the façade of the buildings have kept renovating to meet the requirement of the gentrifiers (bars, high-end restaurants). When the building was built in the era before gentrification, air-conditioning is not yet popular. The commercial buildings were not expected for vibrant commercial activities. As gentrification occurs, many air-conditioners were installed at the façade to provide comfort to the interior (Fig. 54). The windows were so small that it is only fit for office use, but not for displaying product. This is a disadvantage for upper floor shops to notify the pedestrian. Large scale billboards and the bizarre decorative window frame were installed for catching attention (Fig .56, 57).

The shop owners-initiated modification has created a chaotic scene for the buildings, and the additional elements on the façade are affecting the aesthetic of the buildings and streetscape. It also further blocking the light going into the buildings. Most of the additional elements were installed by a simple steel structure. The rust will stain the wall, and the drill hole also creates a leak point for rainwater, which accelerates the façade deterioration (Fig 55). The dripping caused by the air-conditioner also cause the hygienic problem to the street. The ground floor shops also need to install an additional canopy for shading the dripping water. It has made the situation even messy.

The renovation of the façade includes the clearance of window type air-conditioners which replaced by the split-type air conditioner installed at the rooftop. The wall has repainted into a single colour or in a colour theme (Fig. 57). Any suspended structure such as signage, banners are matched to the colour theme. Windows have been replaced with larger size with simpler window frame grids. This maximized the interior light and simplified the façade (Fig.58).

For Yau Shun Building, additional handrails were installed at the edge of each floor which providing extra balconies for some units. The balcony may be used as placing planters or hiding the air-conditioners (Fig. 59, 60).

People are more pleasant to a better quality of urban façade and more likely to revisit the place(Hollander, Anderson, 2019). It also improves the quality of life and strengthens the city identity of the residents (Alishah, Ebrahimi & Ghaffari, 2016).

Facade situation in Lan Kwai Fong

Fig. 54 Air conditioners hanging outside the facade

Fig. 55 Chaotic building service hanging outside the facade

Fig. 56 Decorative window and billboard done by shopowner

Fig. 57 Old building is repainted with colour theme

Fig. 58 Additional strustures are cleared, facade is repainted, window frame are renewed

Fig. 59 Extra balconies

Fig. 60 Extra balconies

54 57 59 55 56 58 60

d. Street Activities

Before the first wave of gentrification in Lan Kwai Fong, it was entirely a residential area, as the vehicles are not popular at that time. The traffic road was acted as a public space for residents hanging around, children playground. Numerous mobile hawker stores are placed on both sides of the street. The street is the public space for both commercial and leisure activities all the time (Fig. 61).

After gentrification, a lot of residential buildings has been replaced by commercial buildings. The population of residents has been reduced. Hawker stores were cleared, and the traffic in the district has become busier. The vehicles have taking more dominance on the street. The pedestrian was pushed to the side of the street as in many other places in Hong Kong (Fig. 62).

However, the vehicles did not dominate the use of the street in Lan Kwai Fong. The dense building environment has restricted the width of Lan Kwai Fong and D’Aguilar Street. These two streets remained single-way street with 2-lane width. Usually, heavy trucks and cars are parked at the roadside, which obstructed half of the traffic flow in the area. Moreover, Wo On lane is a dead-ended traffic road with only 2-lane width. It is challenging to turn around when the car gets into the lane. The pedestrian sidewalk is narrow and with the increasing number of visitors to the district due to gentrification, the people are pushed back to the traffic road. It makes driving in Lan Kwai Fong even more difficult.

The difficult traffic condition has hesitated the drivers to drive into the district. The pedestrian is actually sharing the traffic road space with the vehicles (Fig. 64). Starting from 2002, Lan Kwai Fong, part of the D’Aguilar Street and Wo On Lane, has become a part-time pedestrian street. On Friday, Saturday and public holidays nighttime, the pedestrian has full use of the street space (Transport Department, 2020)(Fig. 63).

Apart from the main road in Lan Kwai Fong area, the back alley space has also gentrified into commercial space. Wing Wa Lane, Wo On Lane and numerous staircases connected to Wellington Street and Wyndham Street are used as drinking space for bars.

The liberation of right-of-way makes Lan Kwai Fong a gathering space for drinkers and event space on public holidays. These street events have become the cultural identity of Lan Kwai Fong.

WoOnLane

D’AguilarStreet LanKwaiFong

Street Activities on Lan Kwai Fong

Fig. 61 Children used the street as playground in 1963

Fig. 62 Busy traffic in 1980s

Fig. 63 Part-time pedestrian street area

Fig. 64 People sharing street space with traffics

61 62 63 64

e. Maintenance Status and buildings age

There more than half of the buildings are built before 1980. 10 out of 42 buildings are even more than 50 years old (Building Department, 2021), regarded as functionally obsolete or probably in need of demolition (La Grange, Pretorius, 2013). By reviewing the façade and interior of those old-aged buildings, they are generally be maintained in good condition.

The building age distribution in Lan Kwai Fong actually proved the gentrification had sustained a longer service life of the buildings.

Building Year 2001-2021 1981-2000 1971-1980 Before 1970

Fig. 65 Building age distribution in Lan Kwai Fong

Fig. 65 Building age distribution in Lan Kwai Fong

66 70 67 71 68 72 69 74 75 73

Fig. 66-75 Facade of buildings with over 50 years old in Lan Kwai Fong

Langham Place

Langham Hotel & Mongkok Complex Shan Tung Street

Shanghai Street Reclamation Street

Portland Street

Argyle Street Nelson Street

Fig. 76 Figure Ground of Langham Place Area

Langham Place

Langham Hotel & Mongkok Complex Shan Tung Street

Shanghai Street Reclamation Street

Portland Street

Argyle Street Nelson Street

Fig. 76 Figure Ground of Langham Place Area

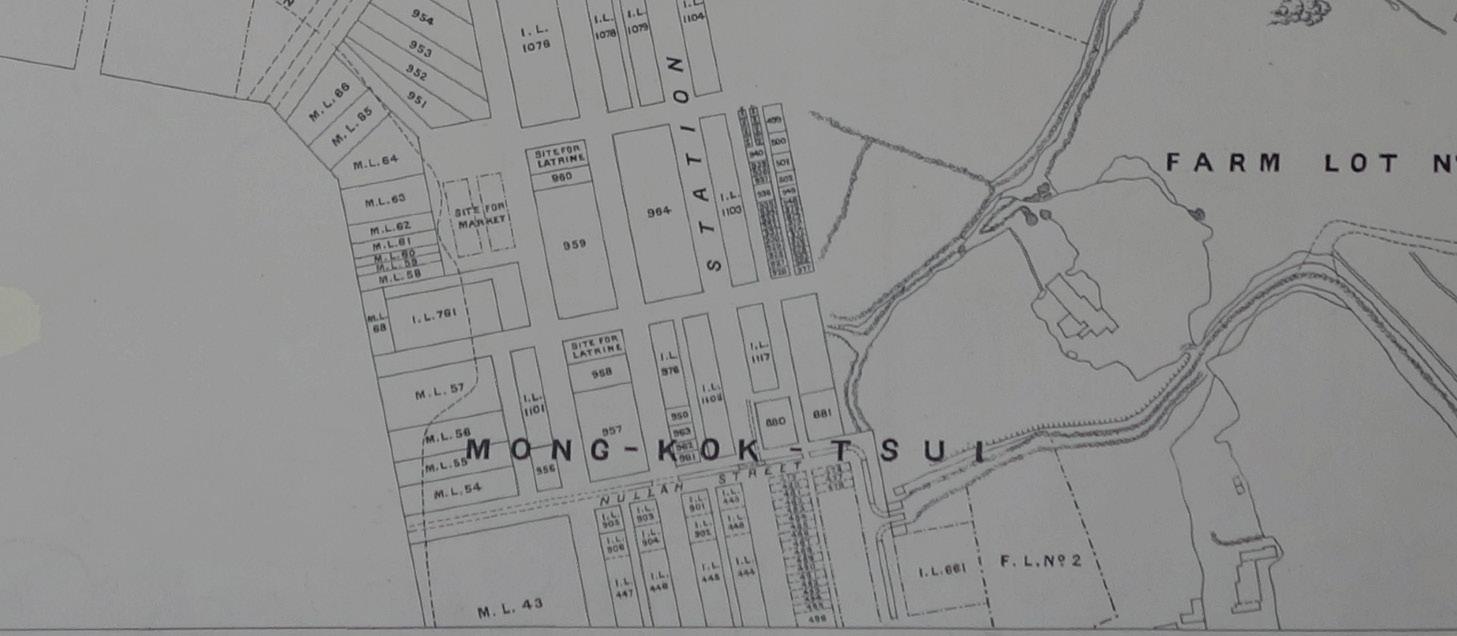

3.2 Langham Place

Historical development of Langham Place

Langham Place located at the intersection of Argyle Street and Shanghai Street. The redevelopment project has been started in 1988. This area initially consisted of many rundown buildings with many “one-woman brothels”. Hong Lok Street was called “bird street”, full of bird-selling shops on the ground floor. The Land Development Corporation (LDC) was approved to execute the acquisition procedure in 1991. The project originally planned to be completed before 1998. Due to the difficulties of negotiating with the residents, the acquisition procedure was not completed until 1996. Finally, the government execute the Land Resumption Ordinance (LR) to resume all the land and hand over the land to URA (substitute role of LDC). URA cooperate with the Great Eagle Holding Limited and develop into a comprehensive mix-used project including a hotel, shopping mall, office tower, community centre, food market, car park and public transport hub (Yau, 2011).

a. Urban Fabric

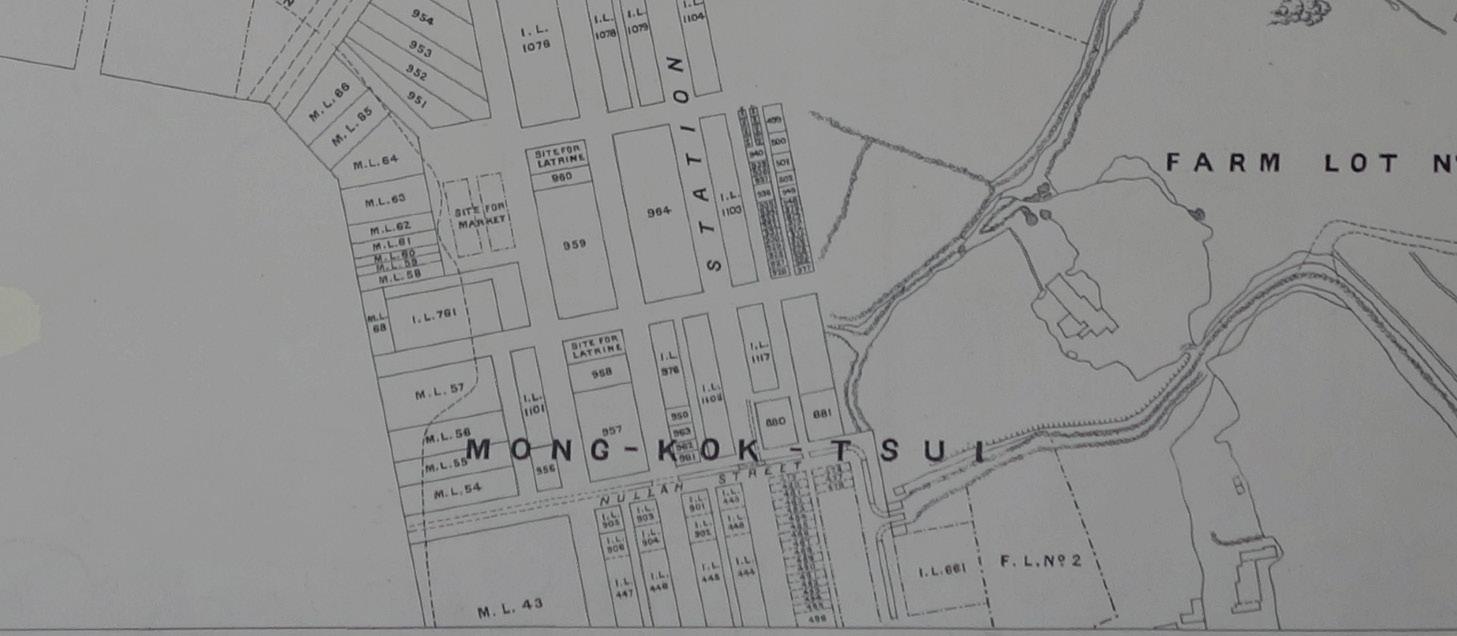

There is a significant urban fabric change in the redevelopment area. The site area is bounded by Argyle Street, Reclamation Street, Shan Tung Street and Portland street with Nelson Street, Shanghai Street and Hong Lok Street embedded in it (Fig. 76). After the redevelopment, Nelson Street and Hong Lok Street (Bird street) was removed from the site, which made Nelson Street became two separated parts, and the bird shops in Hong Lok Street has been relocated to the edge of Mongkok district (Yuen Po Street) (Fig. 78-82).

The pre-existing grid-like urban fabric was established in the 1900s. It existed even earlier than Nathan Road (the busiest road in Yau Tsim Mong District nowadays). Nelson Street was connecting the Mongkok Tsui waterfront before reclamation in the 1990s, and the infinite sky view was not blocked when walking along the street until the Olympus city was built in 2000 (Fig.77).

The launch of Langham Place has further blocked the view of Nelson Street. The 21-meterhigh podium with a 255-meter-high tower has disrupted the sunlight and ventilation in Mongkok District. The exaggerated height of the building makes it visible anywhere in Mongkok, which amplified the role of being an urban edge (Lynch, 1960) (Fig.83-86).

Argyle Street Nelson Street Shan Tung Street

Shanghai Street Reclamation Street

Fig. 77 Map of Langham Place Area in 1900s 78 81

79 82

80

Fig. 78-82 Urban Fabric of Langham Place surrounding area in a) 1984 b) 1987 c) 1997 d) 2000 e) 2007

It also makes the west of Langham Place unimaginable when people are walking from the east. The disruption of urban fabric has erased the history that recorded the development of Mongkok District in the early 1920s.

Olympic City Construction Site (2000) Olympic City (2019)

Olympic City Construction Site (2000) Olympic City (2019)

83 84 85 86

Fig. 83-86 Visual distance and connectivityof Nelson Street

Nelson Street

Nelson Street

Langham Place Construction Site (2000) Langham Place (2019)

Nelson Street

Nelson Street

Langham Place Construction Site (2000) Langham Place (2019)

Pre-existing Nelson Street was deleted in the urban fabric. In Fig.87, we can see the need for the pedestrian walk along Nelson Street is not addressed. The footbridge across Shanghai Street was internalized and privatized. The Langham Place was therefore become a double edge that cut through Nelson Street.

The extended street block created by the Langham Place has significantly altered urban ecology. According to the short-block theory raised by Jane Jacobs (1992), the pedestrian circulation in Mongkok District would be altered. The community at the east and west of Langham Place would be isolated. For example, if someone who lives in an apartment in Canton Road needs to go to the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank Buildings, he/she actually have ten options for his/her journey before Langham Place was built. Nowadays, there are probably four routes left as the Langham hotel has blocked his/her way from west to east. He/she would probably have a very low chance to visit Portland Street, Shanghai Street, the east-side of Nelson Street, or even going into Langham Place. This example also applies to someone who needs to go from the east to the west. Thus, the alteration of circulation has isolated the community from the east and west side of Langham Place (Fig.88-89).

The impact is not only restricted to community bonding but the revenue of some smallscale commercial shops. Most of the people have diverted to Argyle Street or Shang Tung Street. Shops at the long face of the street block would be affected. Although the population has been shifted to Argyle Street and Shang Tung Street, the short edge of the street block actually cannot accommodate many shops, which do not help much for the local economy. Before Langham Place was built, the edge of the Mongkok district was actually located at Ferry street with an elevated West Kowloon Corridor. This 10-lane width traffic road gave a clear distinction of newly developed area in the 1990 by reclamation. It is now pushed inward to Portland Street, which making the area bounded by Argyle Street, Ferry Street and Langham Place into a peninsular area and isolated from the eastern side Mongkok.

Fig 87. Pedestrian crossing at the middle of Shanghai Street

Fig 87. Pedestrian crossing at the middle of Shanghai Street

Fig 88. Illustration demonstrate how the residents travel from Canton Road to HSBC before redevelopment

Fig 89. Illustration demonstrate how Langham Place affect the circulation of the residents

b. Public Space

Before the Langham Place redevelopment project, the only public space in the area would be Hong Lok Street (Bird Street). Hong Lok Street is not a planned and designed public space. The assemble of bird-related hawkers made this street being identified as a gathering space of bird lovers. The street was walled by two rows of old tenement buildings. One of the frontages is the back of house of the buildings. The unauthorized canopies were extended out of the street, noise from the birds and the smell of the bird faeces give an unpleasant, dark environment for this public space (Fig 90).

After the redevelopment of the area, the Shang Tung Street Sitting Area is the replacement of the public space. The amenities of the public space are much gentrified. Much of the greeneries has been planted, children playground with seats, building material matched with the language of Langham Place, which attempt to show the unity of the project (Fig. 91).

However, the design of the public area is not engaging the public use. First of all, there are just two controlled entrances. One of the park entrances is located at the middle of Shanghai street instead of the intersection of Shanghai street and Shan Tung Street, which have higher pedestrian flow (Fig. 92). Another entrance is facing the reclamation street, which is just a simple rectangular puncture hole at the massive hotel block. The benches at the shaded area are directly exposed to the pollutants from the traffic road and the sight from the pedestrian (Fig.93). Also, a large proportion of the public space boundary is fenced off. The entrance length is just 7.5% of the total site boundary of the public space. There is a 7.5-meter “featured wall” blocking the messy elevation of the Wing Cheong Building and blocking the sight of the pedestrian looking into the public space (Fig. 91,92, 95).

The children playground is elevated to the podium, but the ground level does not have any incentive to attract the children to walk to the podium. Thus, the playground has lost its function due to poor accessibility (Fig. 95).

Moreover, most events are invited or requested to hold inside the shopping mall instead of an outdoor area for commercial reasons and branding images. This reduced the opportunities for the public space to gather the neighbourhood (Fig. 94).

Fig 90. “Bird Street” before redeveelopment

Fig 93. Low Profile Entrance

Fig 95. Elevated children playground

Fig 94. Public event held in the mall

Fig 92. Large proportion of public space edge had been fenced off

Fig 91. New Shan Tung Street Sitting Out Area

Fig 90. “Bird Street” before redeveelopment

Fig 93. Low Profile Entrance

Fig 95. Elevated children playground

Fig 94. Public event held in the mall

Fig 92. Large proportion of public space edge had been fenced off

Fig 91. New Shan Tung Street Sitting Out Area

c. Building program, typology, and façade

c1. Building Programs

The buildings are generally divided into hotel, retail, entertainment, and office buildings into three separate building blocks. No residential units are provided in the project and the residents have been totally displaced. Although the relocation unit is just located 1 street block away from the redevelopment site (12 Soy Street), the residents-local stores’ relationship, bird street community, the historical streetscape of Shanghai Street was eliminated. As the relocation units are managed by the URA, only affected residents are entitled to move into the relocation unit at that time. Nowadays, the affected residents are relocated to public housing instead of these relocation units owned by URA. Therefore, the net move out of the unit has made the original community fail to “metabolize” itself and it die out finally (hk. on.cc, 2015).

The redevelopment project is designed to be a multiple function complex. Programs are seemed to be diverse, with around 200 shops, cinema, food court, hotel, and office (Fig.97). However, it is actually a homogenous development. All programs are dedicated to commercial activities with middle to high range consumption. The retails stores are high in number but narrow in types. Most of the stores are dining, entertainment and personal outfits but no market, small scale industry (e.g. warehouse) or small tuck shop or newspaper hawkers etc. (Fig 98). The existing shops actually do not fit the needs of the residents.

There are low range and non-governmental organization in the project. However, it was designed implicitly. The Mongkok Complex is located at the podium of Langham Hotel. It contained a community hall, a cooked food market, a non-government organization (Hong Kong Playground Association) and a nursery school.

The entrance is located below the connecting bridge of the project were at the middle of Shanghai Street. As mentioned before, Langham Place is a double edge in the district. Shanghai Street is in the middle of two edges which do not have any ground floor shops, crossing road facilities. There is no signage or exposing any of these programs on the façade. People also do not expect a low-range consumption, and community facilities would locate on the second floor of a 5-stared hotel. The unreasonable program planning with low accessibility makes this complex block almost not practical.

The failure of conserving the local community and community facilities cause the project unable to sustain an existing community.

Fig .97 Program arrangement in

Fig 96.Relocation Unit away from original site Fig 98. Category of shops could be found in Langham Place

Fig 99. Mongkok Complex located in the podium of Langham hotel.

Fig 100. Mongkok Complex Entrance under the conncting bridge

Entrance

Langham Place

Fig 96.Relocation Unit away from original site Fig 98. Category of shops could be found in Langham Place

Fig 99. Mongkok Complex located in the podium of Langham hotel.

Fig 100. Mongkok Complex Entrance under the conncting bridge

Entrance

Langham Place

b. Building Typology

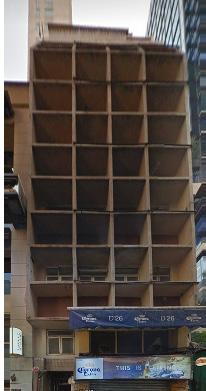

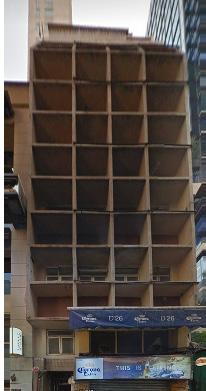

Unlike Lan Kwai Fong, Langham Place only consists of 3 building typologies: Shopping mall, Office tower and hotel on an area equivalent to 6 neighbouring street blocks.

The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) of this project is 11.6, which is higher than the neighbouring tenement buildings, approximately equal to the commercial building next to Nathan Road. However, with the excavated atrium in the shopping mall and other allowance, the floor has been stacked on top of the office tower and the hotel building. The final height of the hotel and the office building are 175m and 255m respectively. The height of the shopping mall is about 90 m. The glass that sealed the atrium of the mall even makes the mass of the project more gigantic.

Only four old buildings were kept in the redevelopment site, which were built in the 1960s - the 1970s. It is difficult to trace the progressive change of the district by these remaining buildings as they were still relatively new buildings when LDC acquired the site in the 1990. The history of this area could be deducted by observing the northern and southern part of the site along Shanghai Street, but the solid evidence on site has been deleted. The solely new buildings on the site also seem not possible to provide opportunities for lowyield or no-yield industry except in the almost hidden Mongkok Complex.

Fig 101. Massing of Langham Place when compared with neighboring buildings

Façade

The façade of Langham Place is much gentrified, tidier than before. The contemporary, business glazing wall combined with irregular geometric tiles cladding with no relationship with the neighboring existing buildings. In the perspective of local residents, it is an alien project, but it became a landmark for the visitors of Mongkok.

The programs of Langham Place are internalized, no human or few commercial activities would be seen on the façade. The architect also wanted to separate the interior with the chaotic street scene at Portland Street, the atrium is elevated to the 4th floor (Lai,2016). This disconnected the visual connection between the consumer in the mall and the street pedestrian.

According to Adam et al. (2016), the blank wall ratio at ground level of Langham Place is 15%. In fact, most of the non-blank wall part is window display and entrance area, there are no commercial activities happened at the external ground level. The most crowded side at Portland Street, people just using the covered corridor for smoking and waiting area.

Although the architects already attempted to break the scale down by diversify the façade elements by using both stone cladding and glazing as façade, but the mass of each separated parts are still too massive.

Although it is noted that blank wall has significantly affect the willingness of the visitors to revisit the place again (Hollander, Anderson, 2019). However, this is not the case for Langham Place. This is because the main circulation is from Nelson Street and Argyle Street and from the underground exit of the MTR station. The visitor is not required to walk along the blank wall to get access to the mall. Therefore, the architect does not need to care about the blank wall as the façade has less opportunities to interact with the visitors, but the façade is interacting with the local residents 365 days per year. This is another example which has shown the ignorance to the local community from the architectural element (Fig. 102).

c.

d. Street Activities

The street activities have been greatly reduced after the redevelopment. Before the old buildings were demolished in the 1990’s, the commercial activities of small-scale local retails store are vibrant in Shanghai Street and bird market.

As mentioned at the façade session, Blank wall and the controlled entrance location have greatly reduced the time that the pedestrian staying on the street. Also, the alteration of urban fabric has pushed pedestrian to Shan Tung Street and Argyle Street. This reduced the number of people going into Shanghai Street and Reclamation Street. When the visitors arrive the project, they are immediately dragged into the interior instead of hanging on the street. This approach may be due to the complex context of Portland Street, a red-light district including nightclubs, massage parlous, mahjong parlous, brothels and other criminal scene (Fig. 102).

Fig 102. The pedestrian do not need walk along to the facade due to controlled entrance

f. Maintenance Status and buildings age

Before the redevelopment project, there are a lot of pre-war shophouse at the site. Those pre-war buildings ususally have pillered walkway with cantilevered balcony covering the walkway (Lee, 2009). This type of shophouses are almost extinct as the building department have prohibit it since 1960 (Yung, Langston & Chan, 2014).

The building condition of those old building is not satisfactory when assessing the façade. By reviewing the historical map, 8-10 Argyle Street was built in 1930’s. It was about 50-60 years old when it was demolished. The paint on the façade has almost all peeled off and exposing the concrete wall surface with dirt accumulated on it. The windows were damaged and covered by wooden board.

The other buildings at Shanghai Street also in similar condition except the Tung Cheong Pawn Shop (同昌大押). The only good condition buildings were not able to be preserved on site. The pillars under the Pawn shops were separated and being displayed in Stanley just next to Murray House.

Discussion

4.1 Urban sustainability of gentrification and urban regeneration – comparative study

The case studies result will be compared in the perspective in urban sustainability.

1. Urban Fabric

Lan Kwai Fong (Classic gentrification) Langham Place (Urban redevelopment) Preserved Distorted Cultural sustainability (positive) Community sustainability (positive) Cultural sustainability (negative) Community sustainability (negative)

The classical gentrification model does not require acquisition of large piece of land. The preservation of urban fabric is an important historical record. When the historical and current map and photos are read side by side, it gives some imaginability for the readers to know how the city evolved with time. The urban fabric also explained a lot of urban phenomenon. For example, why there are a lot of pre-war shophouses located at the west side of Mongkok (e.g. Shanghai Street). This is because Shanghai Street was the coastline of Kowloon since 19th century with piers. Therefore, it is the earliest developed area in Mongkok. If the urban fabric were distorted, these historical clues would be eliminated. It severely affects the cultural sustainability.

The distorted urban fabric also affects the interaction of the community as mentioned in the case of Langham Place. The community is sensitive to these changes which may lead to vanish of a community. This is important to the community sustainability.

Chapter 4

2. Public Space

Lan Kwai Fong (Classic gentrification) Langham Place (Urban redevelopment)

Lan Kwai Fong Amphitheatre: Social Condenser High usage Good urban strategy

Lan Kwai Fong Sitting out area: Isolated Low usage Neutral Urban Strategy

Isolated Low usage Poor urban strategy Community sustainability (positive) Community sustainability (negative)

It is observed that the public space in classic gentrification have better quality. Although Lan Kwai Fong Sitting Out Area is not an ideal public space, the Lan Kwai Fong amphitheatre has already taking the main role of the public space for the community. The amphitheatre has already sufficiently serving the community.

The reason of the better public space quality in gentrification case may be due to the ownership of the public space. In urban redevelopment project, the public space was built by the developers, the location and entrance would be chosen to the best benefit for the project. Take Langham Place as example, the shopping mall is the main source of circulation and revenue of the project, public space with no revenue of course will diverting the circulation.

As the developers want to build a public space for exchanging more GFA allowance from the government, the public space would be designed “carelessly” to protect the best of their benefits.

On the other hands, public space in classic gentrification does not owned by any landlord. All users with different stakes are sharing the public space. With the disadvantage of small footprint, no owner could afford to build a privately-owned public space (POPS). Thus, the public space would be served as the extension of some business (bars, restaurants) and one of the ways to attract people to stay in the district.

3. Façade

Lan Kwai Fong (Classic gentrification) Langham Place (Urban redevelopment)

Commercial activities preserved Residential activities isolated Façade repainted or redesigned

Commercial activities internalised Residential activities eliminated

Community sustainability (slightly negative) Community sustainability (negative)

The façade design of urban redevelopment project and classic gentrification project also have negative impact on showing the residential activities. That means there are less interaction between the residential unit with the street level. It seems ideal to have such interaction, but this is actually not practical in Hong Kong context. The intimate building-to-building distance and dense population and traffic flow on the street may cause privacy and noise issue. Such interaction could be replaced by using the public space and public facilities.

However, the classic gentrification has preserved the commercial activities on the façade, both ground floor and upper floors. This encouraged the street activities and gave an idea of the building program to the visitors. The specific program distribution gave an identity to the district. This improved the cultural sustainability.

4. Building Programs

Lan Kwai Fong (Classic gentrification) Langham Place (Urban redevelopment) Mix-used Diverse Commercial Homogenic

Economic sustainability (neutral) Community sustainability (neutral)

Economic sustainability (negative) Community sustainability (negative)

The diverse program in Lan Kwai Fong can balance the proportion of tenant of different yield in the district, also serving users from different class. Thus, the rate of displacement could be slowed down.

The situation in Lan Kwai Fong seems better than that of Langham Place, however, the diversity is actually done by squeezing the low to middle yield tenant to the upper floors. This makes them more difficult to approach walk-in customers. With the widely use of social media, the situation may alleviate the situation but also implied that there is potential risk of

raising the rent of upper floor. The use of upper floor for commercial use also results in decrease in residential capacity and displacement of residents at the end.

We may need to pay attention to the homogenic programs at the ground floor may not be the most sustainable solution for the community. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic has banned the bars and restaurants to operate for a long period of time. This has severely affected the street life of Lan Kwai Fong.

5. Street Activities

Lan Kwai Fong (Classic gentrification) Langham Place (Urban redevelopment)

Vibrant

Community sustainability (positive)

Inactive

Community sustainability (negative)

Urban redevelopment reconfigured the urban fabric has significantly affected the population of certain street. The internalised program arrangement also reduced street activities. On the other hand, the domination of pedestrian would increase street activities.

Although an extrovert configuration of shops at ground level may increase street activities. However, the type of shops to be opened at the ground level is also an important determinant for a sustainable community.

For example, The Avenue is also an urban redevelopment project led by URA. The project has preserved the extrovert configuration of ground floor shops, preserving the urban fabric. This is true that the street activities are vibrant in the area, but the shops that opened is much gentrified and homogenic to high-end consumption. As a result, the main users of the street are the gentrifiers that newly move into the district and visitors from other social class instead of local residents.

6. Building Typology

Lan Kwai Fong (Classic gentrification) Langham Place (Urban redevelopment)

Diverse

Community sustainability (positive)

Cultural sustainability (positive)

Homogenic

Community sustainability (negative)

Cultural sustainability (negative)

The classic gentrification may temporarily control building mass and the density of the district as some of the old buildings are able to keep in the district. The diversity of the building typology also preserves the development history in the same way as urban fabric.

It is noted that the model can only temporarily slow down the building torn down rate, once over-gentrification occurs in the area, the redevelopment potential has overpassed the gentrified acquisition cost. The old buildings also have the possibilities to be demolished. For instance, half of the Lan Kwai Fong has been converted to commercial buildings already, the remaining residential buildings would be endangered if the district continued to gentrify.

When concluding the comparison between two model, it is obvious that classic gentrification is a preferable way for urban renewal. The better quality of public space, diverse building programs and vibrant street activities fulfilled the need of the long-term residents, consolidate the engagement to the community. This result in increase the sense of belongings and finally establishment of identity.

The preservation of urban fabric, façade and building typology are beneficial to the local culture. The historical record stored in these architectural elements have established an urban image for the district. This would be part of the collective memory of the residents and visitors and finally contributed to the identity as well.

The establishment of identity of the district is important that it strengthen the sense of belonging to the district. That would be the motivation for the residents to resist the buying force from the developers. As the acquisition depends on the percentage of residents are willing to sell their properties.

The above conclusion is just considered in an architectural perspective, the concerns of rising rent, displacement are yet to be solved. The result only concluded classic gentrification is better than urban redevelopment but does not mean classic gentrification is a hundred percent beneficial to the community.

While the classic gentrification is a better model of urban renewal, however, the developers are less preferring the classic gentrification as the small footprint would greatly restricting th

revenue of the project. As the density of the old buildings are very low, usually with 5-6 FAR. Preserving the street block and existing buildings cannot compensate the exaggerate land price in the old city centre. The only way to execute classic gentrification is rely on the current landlord and shop owners to gentrify their properties.

4.2 Possibility of gentrification as a mean to against the government and developers

When comparing the old buildings (more than 50 years old) in Lan Kwai Fong and those buildings previously in Langham Place site, well maintained buildings seem able to survive in the district. However, this effect only feasible if most of the buildings are also well maintained. This is because Tung Cheong Pawn Shop (同昌大押), the only well-maintained building in the district, was not able to resist the acquisition in the Langham Place Project. The good building condition also resist the government using the Land resumption Ordinance or Land (Compulsory Sale for Redevelopment) Ordinance as an excuse to launch the redevelopment project.

In social aspect, the moving in of middle class would increase the resistance to the government and the developers. The knowledgeable middle class would more possible to raise lawsuit during acquisition and land resumption. The raised value of the land and gentrified buildings have also raised the acquisition cost of developer the cultural value established in gentrification may have tourism potential or other economic potential to the government which may resist the redevelopment process.

4.3 Suggestion & recommendation

The classic gentrification model in Hong Kong is purely rely on private owners and free market. However, there are successful case in overseas case. For example, the Dihua Street project (迪化街) in Taipei. The gentrification is led by the government but cooperating with the existing tenants instead of big developers. With the enormous power of the government, the gentrification process is controlled by the government instead of free market. Therefore, the renovation and the rent are also controlled by the government. The intension of preserving existing tenants also preventing displacement. This model has combined the power of government and the advantage of preserving social

and architectural elements of the district.

The Hong Kong government may take reference to this model of development. However, there are some questions have to be solved before applying this model.

1. Cooperating with existing tenants and preserving building blocks and urban fabric may implies sacrificing large amount of land selling revenue. Is there any solution to compensate the loss of revenue?

2. The Taipei government is willing to preserve the Dihua street due to its commercial value and historical value. Is there any justification to preserve an old district with no historical value, cultural value but only active residential community? (e.g. Sham Shui Po, Tai Kok Tsui)

4.4 Conclusion

From the case studies result, it is believed that gentrification is a preferable urban renewal method than urban redevelopment. Gentrification preserved the diversity of shops and building typology of the district. Although the displacement of long-term residents still occurs in gentrification, the time taken is lengthened. Some of the gentrification case has created a new theme for the district, thus, giving a new identity for the place. Moreover, the naturally gentrified district has improved the social amenities quality and ensured the buildings have proper maintenance. This reduced the incentive for the government and the developers to resume the old building blocks.

URA, 2021. About URA - Urban Renewal Authority - URA. [online] Ura.org.hk. Available at: <https://www.ura.org.hk/en/about-ura> [Accessed 7 March 2021].

La Grange, A. and Pretorius, F., 2013. State-led gentrification in Hong Kong. Urban Studies, 53(3), pp.506-523.

Tang, W.S., 2017. Beyond gentrification: hegemonic redevelopment in Hong Kong. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(3), pp.487-499.

Poon, J., 2020. 深水埗社區復興的背後:我們都不要成為膚淺的文青。. [Blog] HolidaySmart, Available at: <https://holiday.presslogic.com/article/191270/%E6%B7%B1%E6%B0%B4%E5%9F%97%E7%A4% BE%E5%8D%80%E5%BE%A9%E8%88%88%E7%9A%84%E8%83%8C%E5%BE%8C%E6%88%91%E5%80%91%E9%83%BD%E4%B8%8D%E8%A6%81%E6%88%90%E7%82%BA%E8% 86%9A%E6%B7%BA%E7%9A%84%E6%96%87%E9%9D%92> [Accessed 18 November 2020].

Brown-Saracino, J., 2010. The Gentrification Debates. London: Taylor and Francis.

Pérez, G., 2004. The Near Northwest Side Story: Migration, Displacement, And Puerto Rican Families. 1st ed. California: University of California Press, p.139.

Ye, M., Vojnovic, I. and Chen, G., 2015. The landscape of gentrification: exploring the diversity of “upgrading” processes in Hong Kong, 1986–2006. Urban Geography, 36(4), pp.471503.

Gotham, K.F., 2001. Urban redevelopment, past and present. In Critical perspectives on urban redevelopment. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Harvey, D., 1989. From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: the transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 71(1), pp.3-17.

Peck, J., 2006. Liberating the city: Between New York and New Orleans. Urban Geography, 27(8), pp.681-713.