La vida y la tiniebla Babyn

Yar Synagogue,Kyiv (Ukraine)

BABI YAR, una zona boscosa con un profundo barranco al oeste de Kiev, marcaba la linde de la ciudad. Alli se produjo una de las peores masacres del siglo XX: entre el 29 y el 30 de septiembre de 1941 unos 35.000 judíos fueron asesinados a tiros por los oficiales de las SS alemanas, Ios Einsatz gruppen y soldados de la Wehrmacht apoyados por tropas locales. Durante las siguientes semanas y meses, otros 10.000 judios mås, asi como prisioneros de guerra soviéticos, comunistas, nacionalistas ucranios, gitanos y pacientes de un cercano hospital psiquiatrico fueron asesinados en las inmediaciones. Este ‘holocausto de las balas’ fue una de las mayores atrocidades de la era moderna.

Babi Yar es un terreno con una topografía accidentada: la misma, precisamente, que apro vecharon Ios oficiales de las SS para asesinar a esas decenas de miles de personas sin tener que abrir fosas comunes. La masacre creό, de hecho, una nueva topografía: una topografía física de la muerte y el asesinato. Por ello, el suelo de Babi Yar puede considerarse sagrado.

Construir sobre un lugar que ha sido testigo de más asesinatos y devastacion que la mayoría de lugares de la tierra, hace que caiga una enorme responsabilidad sobre el arquitecto. ¿Como honrar a las victimas? ¿Cuál es la respuesta acorde con la tragedia? Cuando en octubre de 2020 me encargaron una sinagoga en Babi Yar, todas estas preguntas rondaron mi cabeza. Por supuesto, los ecos del hermoso poema escrito por Yevgueni Yevtushenko en 1961 —«No hay monumentos en Babi Yar»— no hacían sino acrecentar mis dudas. ¿No es el poema, y su extraordinaria versi6n musical a cargo de Shostakovich, la conmemoracion más profunda que pueda imaginarse? Aunque esto sea cierto hasta cierto punto, creo que la arquitec tura puede desempeñar un papel conmemorativo diferente al procurado por otras disciplinas, como la literatura y la música.

Podria pensarse que la respuesta adecuada a esta increíble masacre debería ser una arquitectura sombría, minimalista y monumental. La historia de Ios monumentos del Holocausto esta Ilena de este tipo de ejemplos. Con todo, abordé el proyecto de un modo muy distinto. Es imposible que ninguna arquitectura monumental pueda dar cuenta de un monumental sufrimiento. Pero si podemos crear un edificio con una dimension transformadora que permitiera establecer nuevos rituales. En un lugar literal y metafóricamente empapado de sangre, no podemos erigir un edificio que se imponga al suelo

BABYN YAR is a wooded area with a deep ravine located in the west of Kyiv, Ukraine, that used to mark the edge of the city. It is the site of one of the worst massacres of the 20th century, when on 29 and 30 September 1941, approximately 35, 000 Jews were shot and killed by German SS officers, their Einsatzgruppen, and other soldiers of the Wehrmacht, supported by local Ukrainian troops. Over the following weeks and months tens of thousands of additional Jews, Soviet prisoners ofwar, communists, Ukrainian nationalists, Roma, andpatients ofa nearby psychiatric hospital were murdered within the grounds of Babyn Yar. A ‘ho locaust by bullets, ‘ it was one ofthe worst atrocities of our modern era.

The territory of Babyn Yar is marked by gorges and a strong topography. It was precisely this to pography that the SS officers utilized, killing these tens ofthousands ofpeople without having to exca vate mass graves. Through the mass killing, a new topography was created: a physical topography of death and murder. The very soil of Babyn Yar can therefore be considered sacred.

To build on land that has seen more murder and devastation than most otherplacesputs the architect under immense responsibility. How do we respect the dead? Can we develop a response that is appropriate to the gravity of the site‘s history? These questions were going through my head when I re ceived the commission to design a synagogue on the grounds ofBabyn Yar in October 2020. Of course the echoes ofYevgeni Yevtushenko ‘s majestic poem written in 1961 — “There are no monuments over Babi Yar” — accentuated my hesitation. Can we, or should we, build there at all? Isn ‘t the poem, and its extraordinary intonation by Shostakovich, the most profound commemoration we can imagine? While this is true to a certain extent, I also believe that architecture can bring a quality of commemoration to Babyn Yar that is truly differentfrom other artistic disciplines, such as literature and music.

One might think that the appropriate response to this unbelievably inhumane massacre should be an architecture that is somber, minimalist, and monu mental. The architectural history of Holocaust me morials isfull ofthese. But I wanted to approach the project in a vel’,’ different way. We will never match the monumental suffering of the massacre through a monumental architecture. Instead, I wanted to create aproject that has a transformative dimension and establishes a new ritual on the site. In view of the site, which is literally and metaphorically drenched with blood, we cannot respond to the massacre by y al relato historico. El mensaje categorico y ce-

ArquitecturaViva 242 2022 33

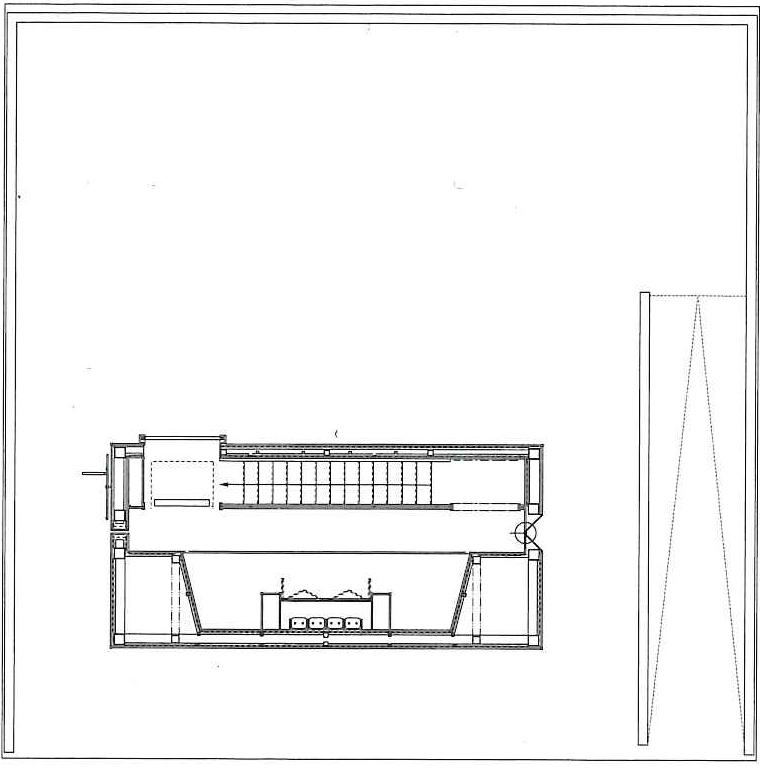

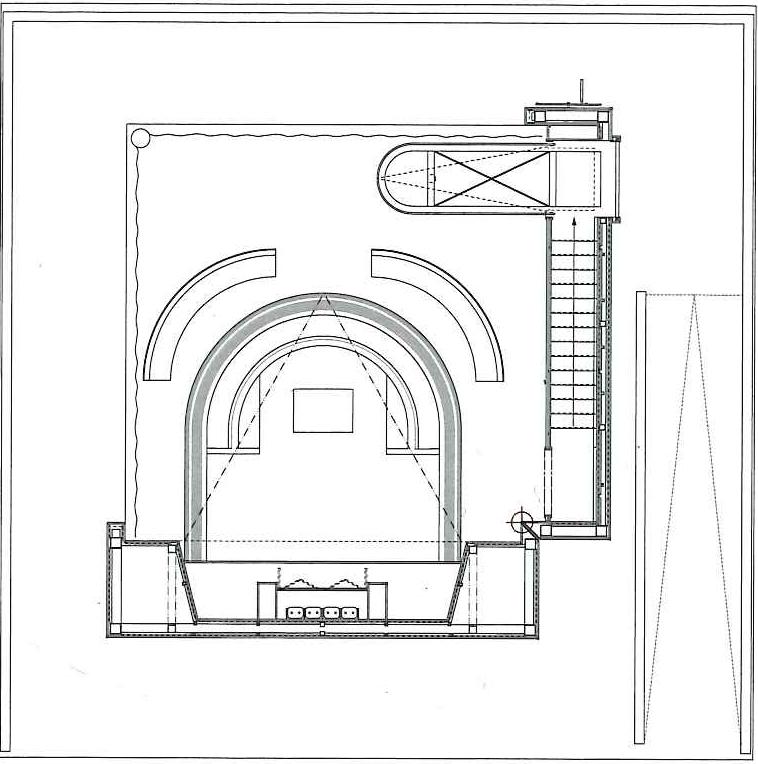

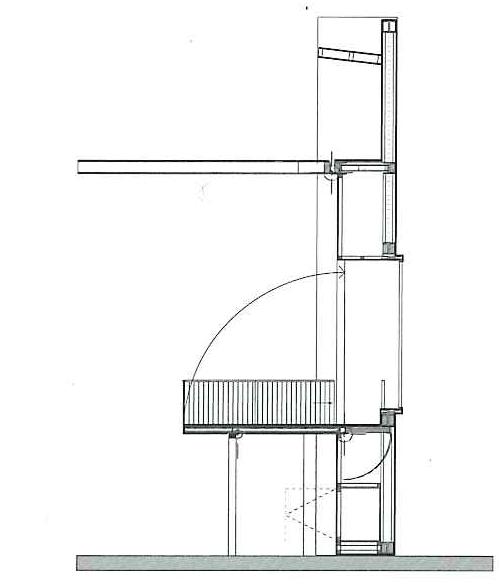

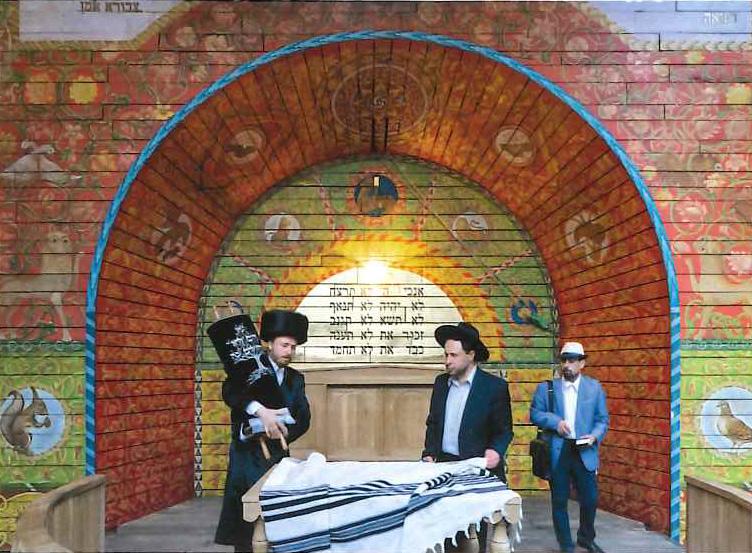

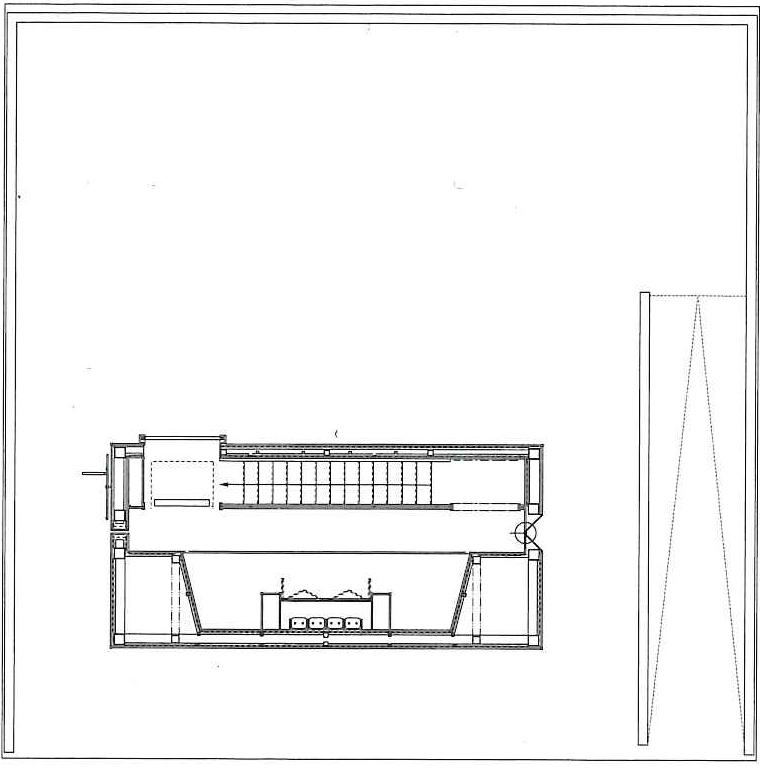

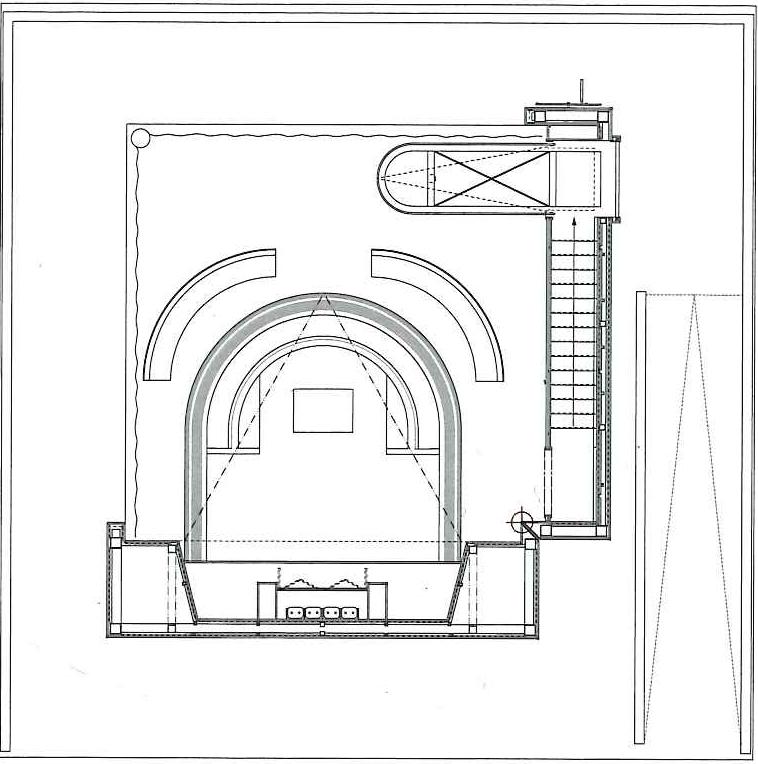

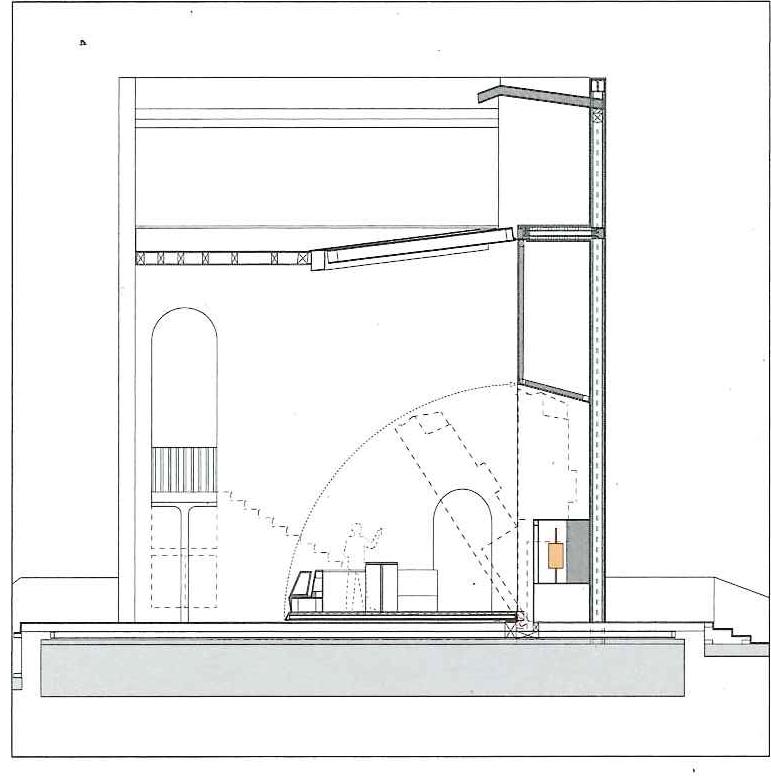

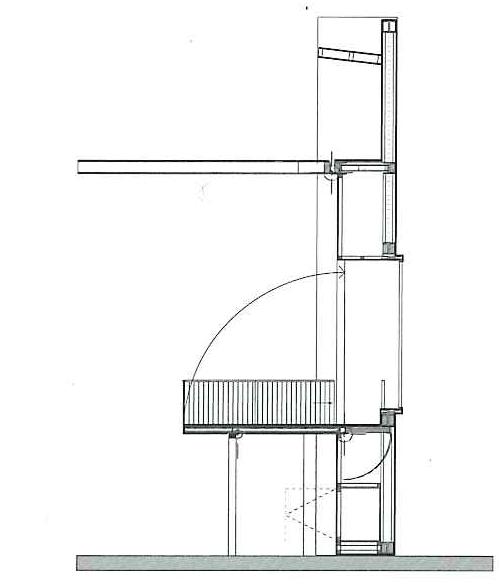

El íntimo vínculo del culto judío con las Escrituras se interpreta de manera literal y la construcción toma la forma de un gran libro desplegable, cuya apertura deliberadamente manual se convierte en una nueva ceremonia colectiva.

The close link betweer Jewish worship and the Scriptures is interpreted literally with the building shaped like a pop-up book, opened manually in what deliberately constitutes a new congregational rite.

rrado que podría sugerir un numento de estas características no haría justicia a las miles de voces concretas que perecieron en Babi Yar. Por ello, preferí una solución polivalente más que una estática y conclusiva. De ahí nació la idea de una arquitectura que instalara en el lugar un nuevo ritual colectivo; una arquitectura activa, transformadora, que es conmemorativa en la medida en que produce un sentimiento de asombro y temor.

A menudo el pueblo judío ha sido definido como el “pueblo del libro”, por eso la idea de aludir a un libro a través del proyecto tenía sentido. También me atraían los libros pop-up, tan fascinantes. De un objeto plano, casi bidimensional, emergen de repen te volúmenes tridimensionales que con frecuencia suelen ser escenarios arquitectónicos. Es difícil resistirse a la tentación de abrir estos libros para asistir

al despliegue de un mundo nuevo y sorprendente; y, en cierto modo, esto es Io que sucede cuando nos reunimos para orar en una sinagoga: abrimos juntos un libro, ya sea el Sidur—el libro de oraciones—, o bien la Biblia. Se trata de un mundo de cuentos, de historias, de moral, de amor, de sabiduría.

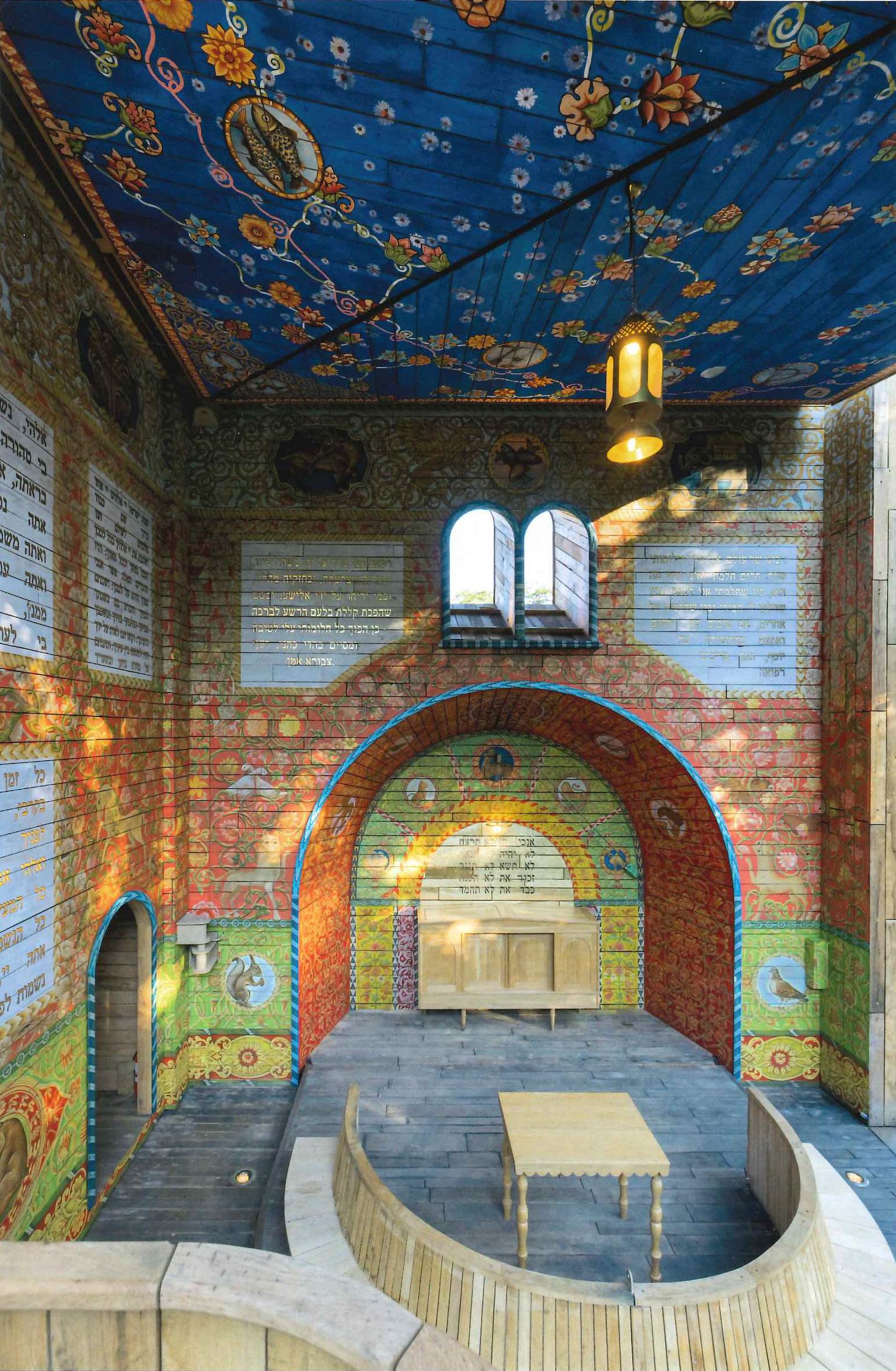

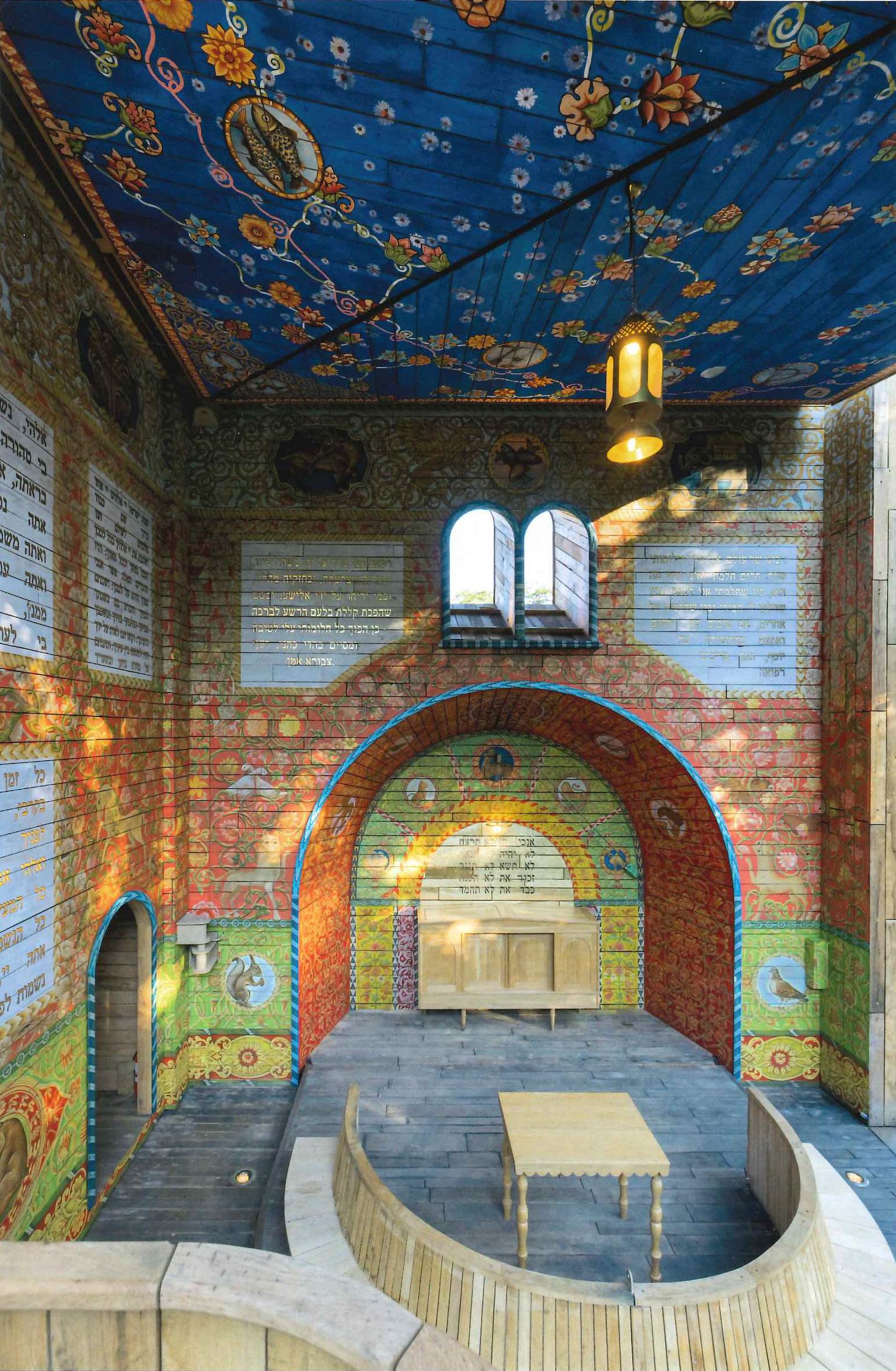

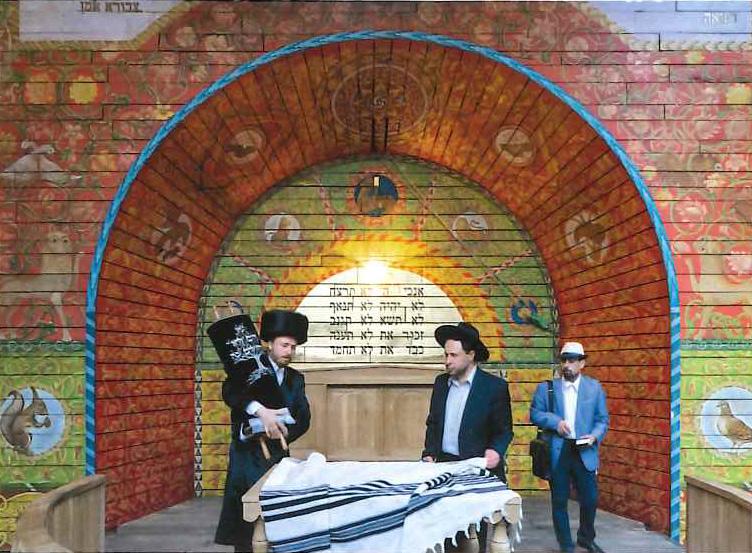

En cuanto a los interiores del edificio, quise evo car las sinagogas de madera del oeste de Ucrania, que databan del siglo XVI pero fueron destruidas por los nazis. Sus ornamentos y caligrafias aplicadas sobre las paredes resultan fascinantes. En especial me interesó una vieja fotografia de la sinagoga de Hvizdets, muy hermosa y que tenía un texto escrito sobre las paredes. Un texto que, sorprendentemente, contiene una bendición bastante lóbrega sobre la interpretación de los sueños, la posibilidad de con vertir las pesadillas en sueños felices. De inmediato

me di cuenta de que no había mejor leitmotiv para el proyecto, y esa bendición ocupa ahora la pared principal de la sinagoga de Babi Yar.

Empece a trabajar en elproyecto solo dos sema nas después de que mi maravillosa esposa Xenia diera a luz a nuestro hijo Max. Me involucraba en un asunto relacionado con el asesinato y un sufrimiento insoportable al mismo tiempo que me maravillaba de la llegada de un nuevo y ‘tierno ser humano. Cuando miré el hermoso rostro de nuestro hijo, noté su gran curiosidad y su inmensa alegría de vivir. Mi hijo me enseñó que la sinagoga de Babi Yar no podía ser solo un lugar para conmemorar el pasado, sino también para inaugurar un futuro. Tenía que ser un proyecto que convirtiera la pesadilla en un sueño. Un proyecto que no se atrincherara en la muerte la destrucción, sino que celebrara la belleza de la vida.

34 2022 ArquitecturaViva 242

designing a building that imposes itself onto the ground and onto the narrative ofhistory. The categorical and definitive message that a monumental and static building would suggest stands at odds with the tens ofthousands ofdistinctive voices that perished in Babyn Yar. I was looking for a building that is polyvalent rather than demanding a conclu sive reading. Hence, the idea was born to design an architecture that creates a new collective ritual, that has a performative and transformative quality, that is commemorative, just as it also creates a feeling of wonder and wave and awe.

With the Jewishpeople often being referred to as the ‘People ofthe Book, ‘ the idea ofreferencing a book in the design is maybe not all that surpri sing. I was then thinking ofthe pop-up books that are so fascinating. From a flat, almost two-dimensional

object, they unfold into three-dimensional volumes, often into scenographies with an architectural character. I believe no one can resist the tempta tion to open these books and see how a new and surprising world unfolds. In a certain way, this is exactly what happens when we come together to pray in a synagogue: we open a book together (either the Siddur, i.e., the Jewish prayer book, or the Bible). Reading this book in the collective of the congregation also opens a new world to us. A world of stories, of histories, of morals, of love, and of wisdom.

For the interiors of the Babyn Yar Synagogue, wanted to reference the historic wooden synagogues ofwestern Ukraine, dating back to the 16th century but all destroyed in the Nazi era. Their use of ornament and writing on the walls is fascinat-

ArquitecturaViva 242 2022 35

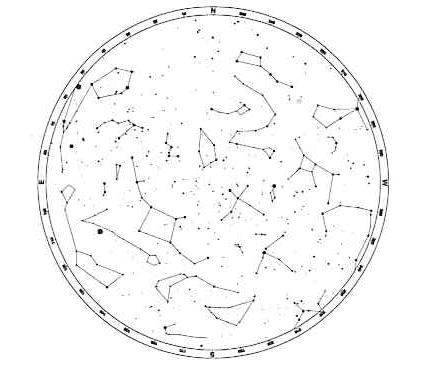

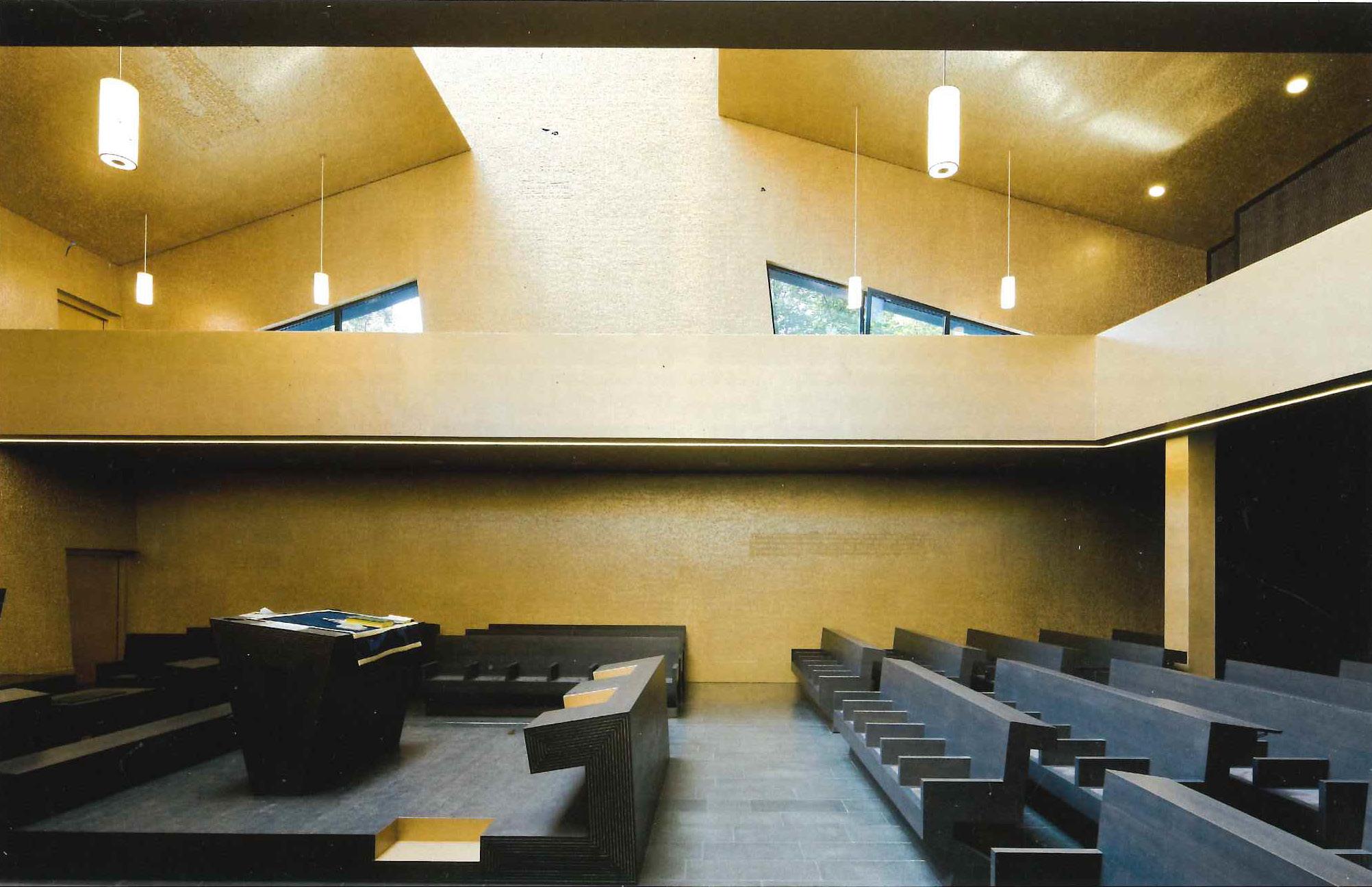

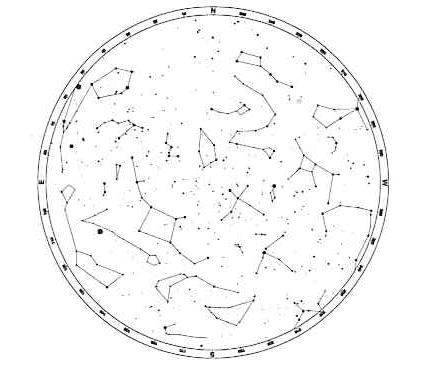

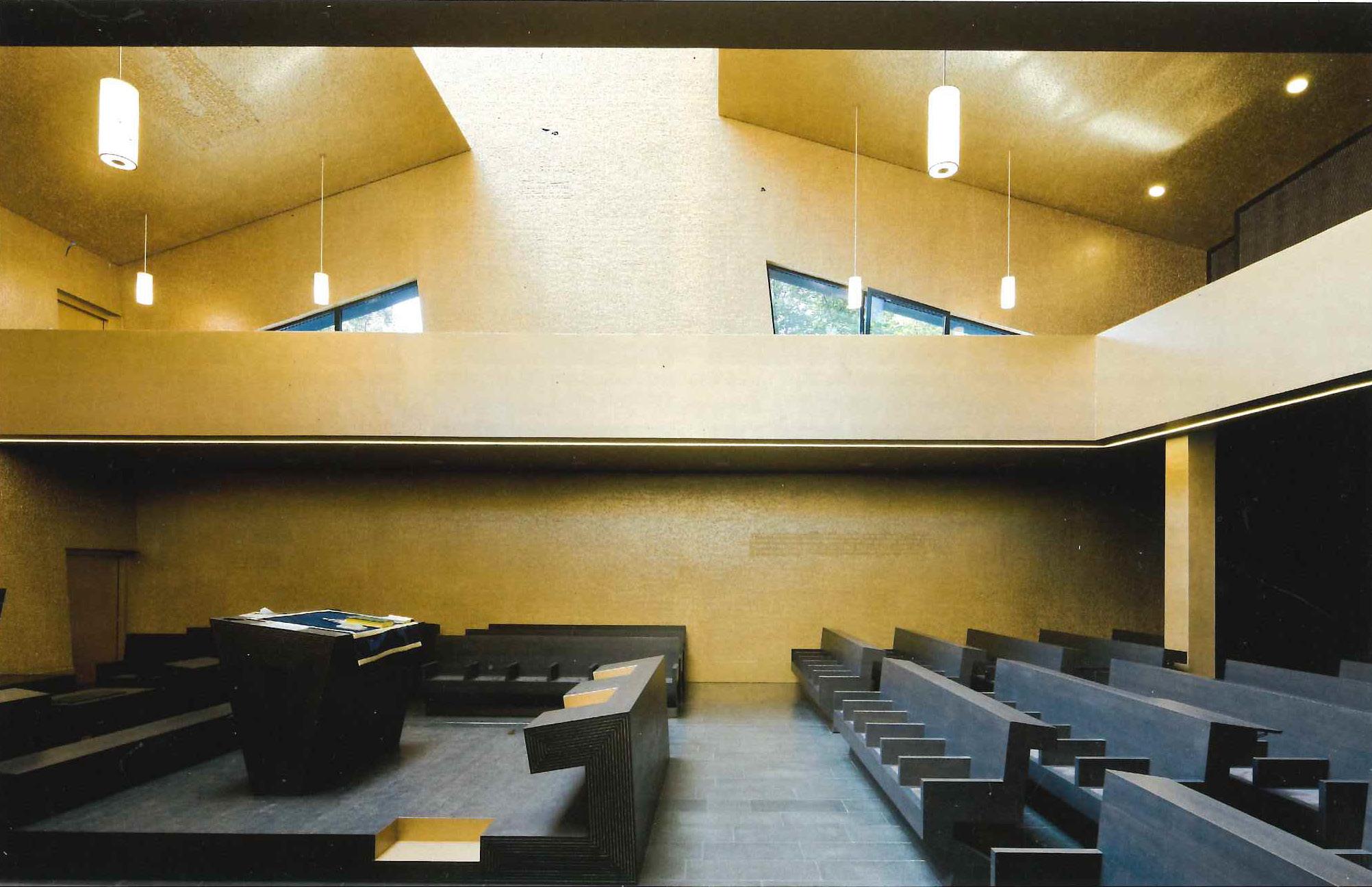

Bendiciones y alegorías se entrelazan en las paredes recuperando el colorido de los tradicionales templos en madera destruidos por los nazis, mientras las constelaciones que decoran la cubierta evocan el cielo en la noche de la tragedia.

Blessings and allegories intertwine on the walls, recalling the colors of the traditional wooden temples that the Nazis destroyed, while the constellations on the ceiling evoke the sky on the night of the tragedy.

Mientras escribo estas líncas, Babi Y ar está siendo bombardeado. El enclave donde se produjo una de las peores masacres del siglo xx, donde decenas de miles de personas fueron asesinadas en apenas unos días a manos de los nazis, se ha convertido de nuevo en un lugar de guerra y matanza. Cinco personas murieron en el ataque a la torre de la televisión esta tal y a un centro deportiva ubicados en las inmedia ciones. Los ataques, más allá de la trágica pérdida de vidas, suponen la destrucción de la histona y la violación de la memoria de las 33.000 personas que perecieron hace ochenta años. En el contexto de una guerra, la destrucción de un lugar conmemorativo tan importante constiuye un homble capitulo más que degrada nuestra condición humana.

Como he apuntado antes, el encargo de la si nagoga ca Babi Yar —una de las ‘‘zonas cero’ de la historia curopea y acaso mundial—supuso para mí una responsabilidad muy grande. Con esta frágil construcción de madera, quise diseñar un edificio en el que los judios pudieran orar, pero que también estuvicra abierto a la celebración de la belleza de la vida. Dado que la sinagoga debía inaugurarse con ocasión de los ochenta años de la masacre, cl 29 y el 30 de septiembre de 2021, el perrado de diseño y construcción duró solo seis meses y fue intenso. Durante este tiempo, conoci a un grupo de personas asombrosas y profundamen te comprometidas en Kiev. que desde entonces son amigos cercanos. A la semana de la invasión rusa de Ucrania, éstos amigos se han visto envueltos en una amarga guerra y muchos de ellos han acabado como refugiados.

El 1 de marzo de 2022, los misiles impactaron a 150 metros de la sinagoga. Solo unos meses des pués de su inauguración, cl edificio se vio inmso ca una guerra que solo celcbra la muerte. ¿De qué sirve conmemorar la historia si las enseñanzas que deberían extraerse se olvidan e ignoran tan fácil mente? A diferencia de la robustez de otros edificios conmemorativos de picdra y hormigón, la fragali dad de la sinagoga de madera implica su cuidado diaro. Este cuidado, esta fragiliad, constituyen la verdadera conmemoración. La sinagoga necesita a su comunidad, a su público y a sus visitantes. Con el lugar convertido en un escenano bélico, la sinagoga ha perdido a su comunidad. Rezo por el pueblo de Kiev y de Ucrama, para que la guerra salvaje ter mine cuanto antes, y espero que la sinagoga acabe recuperando a sus fieles de manera que las lecciones de fragilidad na queden del todo ahogadas por el cruel fragor de la guerra.

El cruel fragor de la guerra

36 2022 ArquitecturaViva 242

ing. There was in particular one historic photo graph of the Gwozdziec Synagogue that i had been studying which was striltangly beautiful, featuring also a text on the walls. Surprisingly, lí is quite an obscure blessing involving the interpretation of dreams, to transform nightmares into good dreams. I immediately thought that there can be no better leitmotiv for the Babyn Yar Synagogue than this blessing that turns nightmares into good dreams. This blessing now occupies the main wall of the Babyn Yar Synagogue.

Í started worlung on the Babyn Yar Synagogue just two weeks after my wonderful wife, Xenía, gave birth to our son, Max. Hence I was engaged in a topic of murder and unbearable suffering, and at the same time marveling at this new, tender human being. When I looked mwso the beautiful face of our little son, I saw his great curiosity and his immense joy of experiencing life. My son taught me that the Babyn Yar Synagogue cannot only be about commemorating the past, but must also be about opening up a new future. lt needs to be a project that turns a nightmare into a good dream. A project that is not entrenched in death and destruction, but celebrates the beauty of life.

The Cruel Noise of War

As I write this, Babyn Yar is being attacked. The site of one of the worss massacres of the 20th century, where in 1941 tens of thousands of people were killed within a few days at the hands of the Nazis, has again become a site of war and killing. Five people died when a TV tower and a sports center located on the grounds of Babyn Yar, on the outskirts of Kyiv, were hit. Beyond the incredibly tragic loss of life, it represents a destruction of history, and a violation of all the over 33,000 victims who died there eighty years ago. Within a horrendous war, the looming destruction of a memorial site of this scale and meaning ls another horrific chapter debasing our humanity.

When in October 2020 i was commissioned to design a synagogue for the site of Babyn Yar, I was extremely moved by the honor to build on this territory that represents one of the ‘Ground Zeros’ of European (or even World) history, and by the responsibility that this imposed on me as an architect. Of course one aim was to shape a building that commemorates the past. Even more, with its fragile wooden construction, transformative quality, and colorful painting, making ts differera from any other kind of ‘monumental ‘ and commemorative architecture known to me, I wanted to design a building

in which Jews could pray, but also one that would be open to visitors and citizens of Kyiv. lt was to be a place in which together they could celebrate the beauty of life. As the buildirrg was to open with the commemoration of eighty years since the massacre on 29 and 30 September 2021, the period of design and construction, taking a mere six months, was as intense as the practice of architecture can get. During this time, 1 got to know an astounding and deeply committed group of people in Kyiv who have since become close friends. Within only seven days of Russian invasion into Ukraine, they have been drawn into a bitter war, and many of them have become refugees.

On 1 March 2022, rockets struck just 150 meters from the synagogue. Only a few months after its inauguration, the synagogue ls caught up in war,

which only celebrates death. What is the point of commemorating history ifthe lessons to be learned are forgotten and ignored so easily? It leaves me speechless, numb, and powerless. Compared to other commemorative architecture that is mostly built of stone and concrete, the fragulity of the wooden synagogue means that is must be cared for every day. This duily care, and its fragility, is precisely what represents actual commemoration The synagogue needs ¡ts community, lts audience, and its visitors. With the site now a war zone, it has been robbed of this community pray for the people of Kyiv and of Ukraine, that the savagery of the war end as soon as possible, and | hope that the synagogue can eventually regaín lis community,so that the lessons of fragility are not drowned out by the cruel noise of war.

ArquitecturaViva 242 2022 37

La palabra renacida

New Synagogue, Mainz (Germany)

Al no haber una tradición tipológica bien perfilada en relación con las sinagogas, se ha entroncado con la hermenéutica judía para dar valor a la palabra escrita como elemento ornamental.

In the absence of a clearly defined typological tradition in relation to synagogues, the project connects with Jewish hermeneutics to exalt the written word as an ornamental element.

POCAS COΜUNIDADES judías superan a la de Ma guncia en importancia y tradición. Durante la Edad Media, la ciudad fue el principal centro de enseñanza religiosa y escenario del magisterio de una serie de rabinos influyentes, en especial Gershom ben Judah, cuyos preceptos tuvieron un fuerte impacto en el ju daismo: su sabiduria era tan grande como para hacerle merecedor del apelativo “luz del exilio”. El nuevo centro comunitario judio de Maguncia se sosticne sobre esta tradición.

Aunque el edificio se erige en el emplazamiento de una sinagoga incendiada durante la noche de los cristales rotos, no quería hacer referencia al Holo causto. En los años ochenta se habian colocado en el solar algunos de los restos y las mantuve por respeto, aunque yo nunca los hubiese recuperado. Por varias razones, me propuse firmemente no hacer del edificio destruido el sustento del nuevo. Antes de la guerra ya existian otras sinagogas en la ciudad; además, no quería que la barbarie nazi fuese ‘coautora’ de mi proyecto. Por último, pero no menos importante, en Maguncia se dio forma a la religión judia tal como la conocemos hoy, y este aspecto positivo es el que debe celebrar el diseño. El capitulo del Holocausto debe ser rememorado, pero en otra parte.

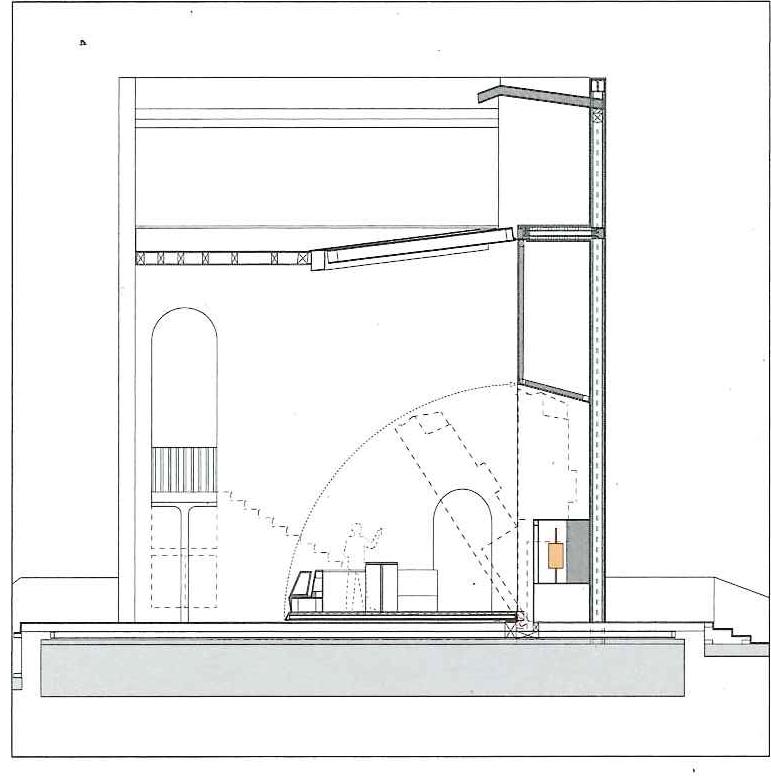

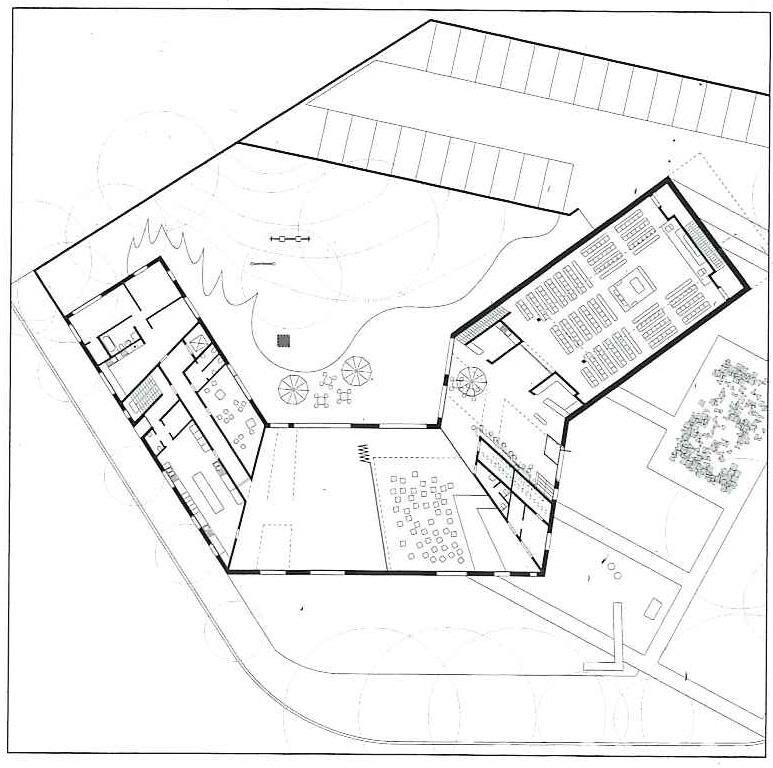

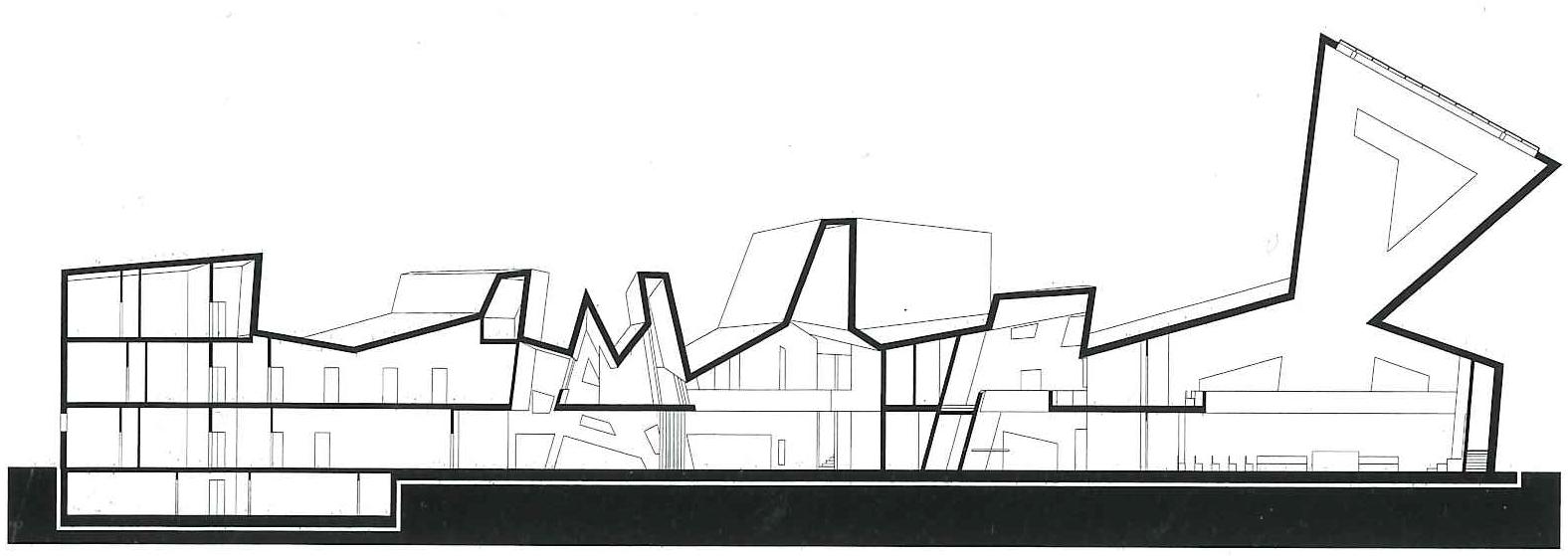

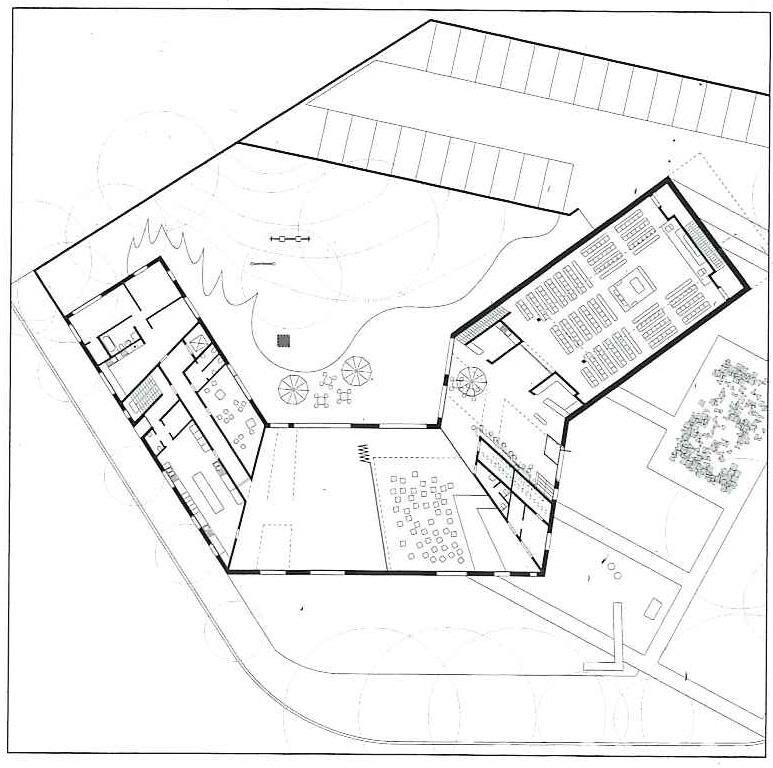

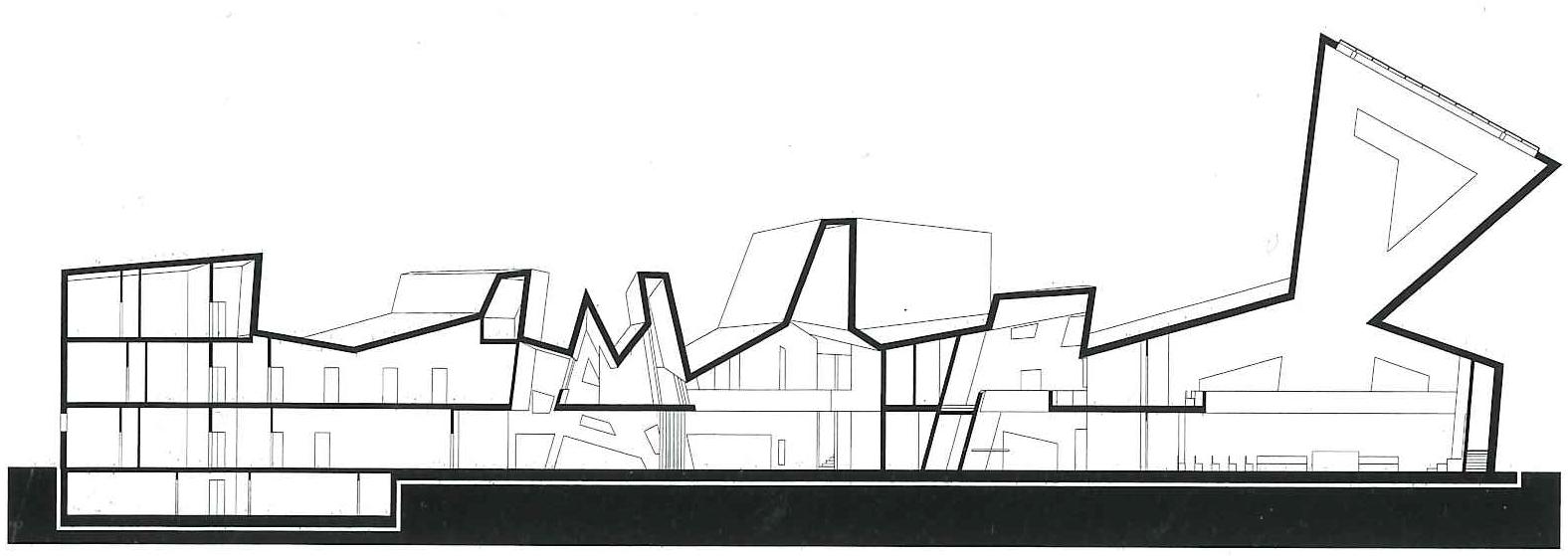

La sinagoga está situada en un barno residencial de finales del siglo XIX, caracterizado por su trama de bloques perimetrales. Asumimos esta forma urbana, de suerte que el volumen del edificio se situase pa ralelo a las calles y sus fachadas quedaran enrasadas con los edificios colindantes. La utilización del tipo de bloque perimetral en un edificio sagrado dista de ser frecuente: cuando se piensa en este tipo de construcciones, el tópico es imaginarse un volumen aislado y retirado de la calle.

Al orientar hacia el este la sala de oración se crean dos espacios exteriores: un jardin intemo, destinado a los fieles, que puede utilizarse con fines recreativos o celebratorios; y una plaza publica frente a la entrada principal, abierta al bario en un contexto de trama urbana muy densa. La ausencia de cualquier tipo de puerta o barrera sugicre que la plaza pueda funcionar como un espacio en verdad público y de uso cotidia no, algo poco común en un edificio religioso, espocial mente si se trata de una sinagoga en Alemania.

A lo largo de su historia, el judaismo nunca ha teni do una fuerte tradición constructiva. A diferencia de otras religiones, no ha ercado estilos arquitectónicos que intentaran traducir en términos espaciales sus va lores y credos. Sí ha utilizado, en cambio, la escritura, en especial el Talmud elaborado tras la destrucción del segundo Templo y el comienzo de la diáspora, y que es una respuesta a la pérdida de Jerusalen como

FEW JEWISH communities can surpass the one of Mainz in importance and tradition. During the Middle Ages the city was a major center of religious instruction, and this can be traced back to a series of influential rabbis, especially Gershom ben Judah, whose teachings and legal decisions had an impact on Judaism at large. His wisdom was deemed so great that he was given the name ‘Light of Diaspora’. The new synagogue of Mainz builds on this tradition.

Even though the building site is the location of a previous synagogue, destroyed during the Nazi era, it was my intention that the new syna gogue not reference the Holocaust. Fragments of the old synagogue had been placed there in the 1980s by a previous generation. I kept them there out of respect for that decision, but it would not have been my decision. For a number of reasons, it was my very intention that the destruction of the old synagogue not be the foundation of my new synagogue. First of all, there were several synagogues of Mainz before that war, across the city. Secondly, I did not want to make the Nazi destruction a ‘co-author’ of the new design. And last but not least, the city of Mainz has literally shaped the Jewish religion we know today.This positive force had to be celebrated in my design. The Mainz chapter of the Holocaust needs to be commemorated somewhere else.

The site for the synagogue is located in a late 19th-century residential neighborhood, charac terized by its perimeter block pattern. We chose to use this urban figure for the overall lavout of the synagogue. The volume of the building is situated parallel to the streets and its facades are in line with the existing neighboring buildings, thus creating a contained street space. The use of the perimeter block typology for a sacral building is highly unusual, as one would usually expect a religious building to sit like a solitary volume, withdrawn from the street.

By orienting the part of the building contain ing the prayer hall towards the east, two squares or open spaces are created: an internal garden for the community offering room for recreation and celebration, and a public square in front of the main entrance offering an open place for the neighborhood within a densely built-up urban fabric. The absence of any kind of gating or barriers is what makes this square a truly civic space, used for everyday activities by the general public, which is rare for a religious building, especially for a Synagogue, in Germany.

ArquitecturaViva 242 2022 39

centro del judaísmo y el desarraigo en general. El tema del espacio impregna todo el Talmud, desde el contenido de sus capítulos hasta las técnicas dialéc ticas de los rabinos, pasado por el propio modo en que está escrito. Sus palabras y letras poseen además una cualidad objetual. Estas dos características —el concepto de Talmud y la cualidad objetual de la es critura—dan forma al centro comunitario.

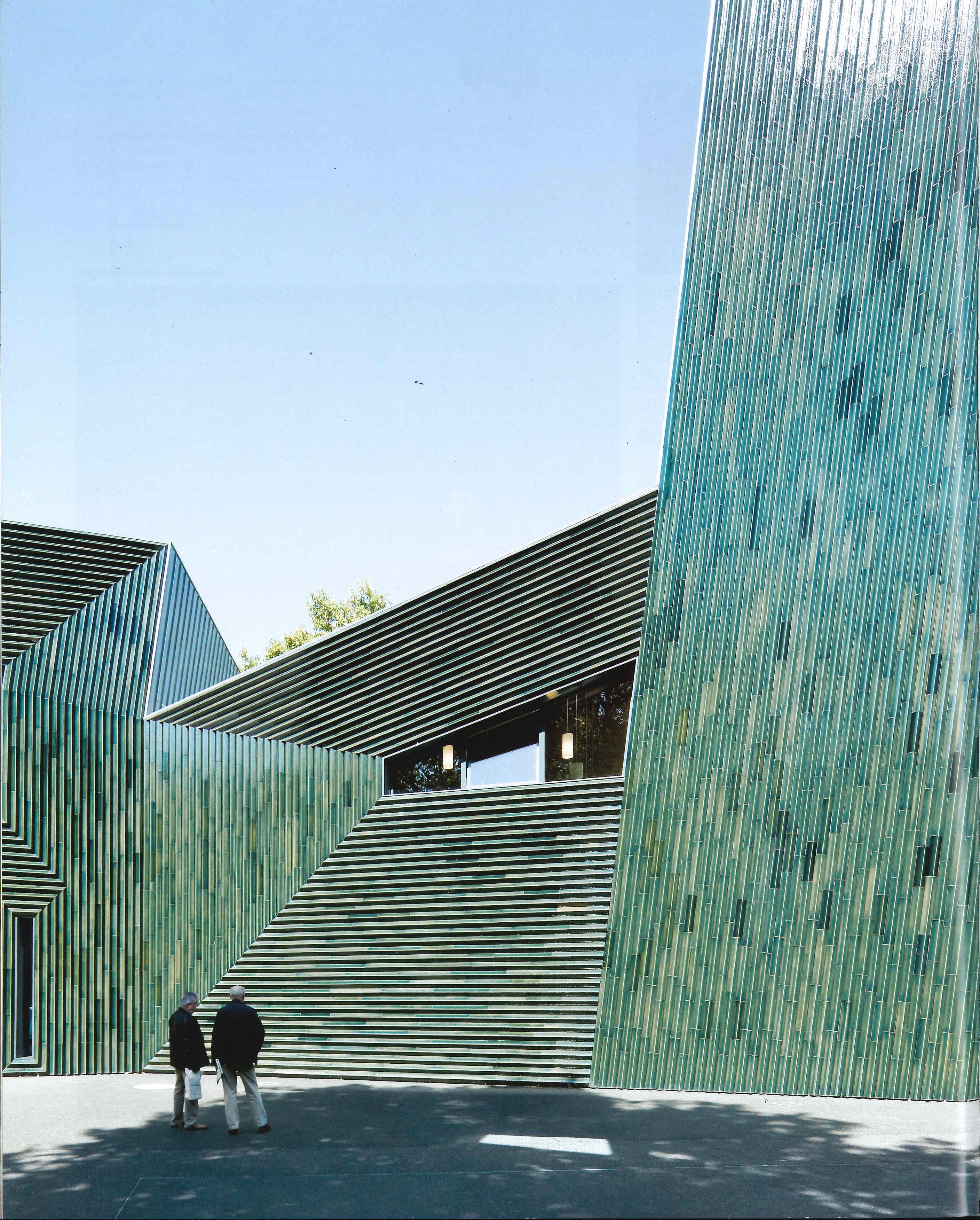

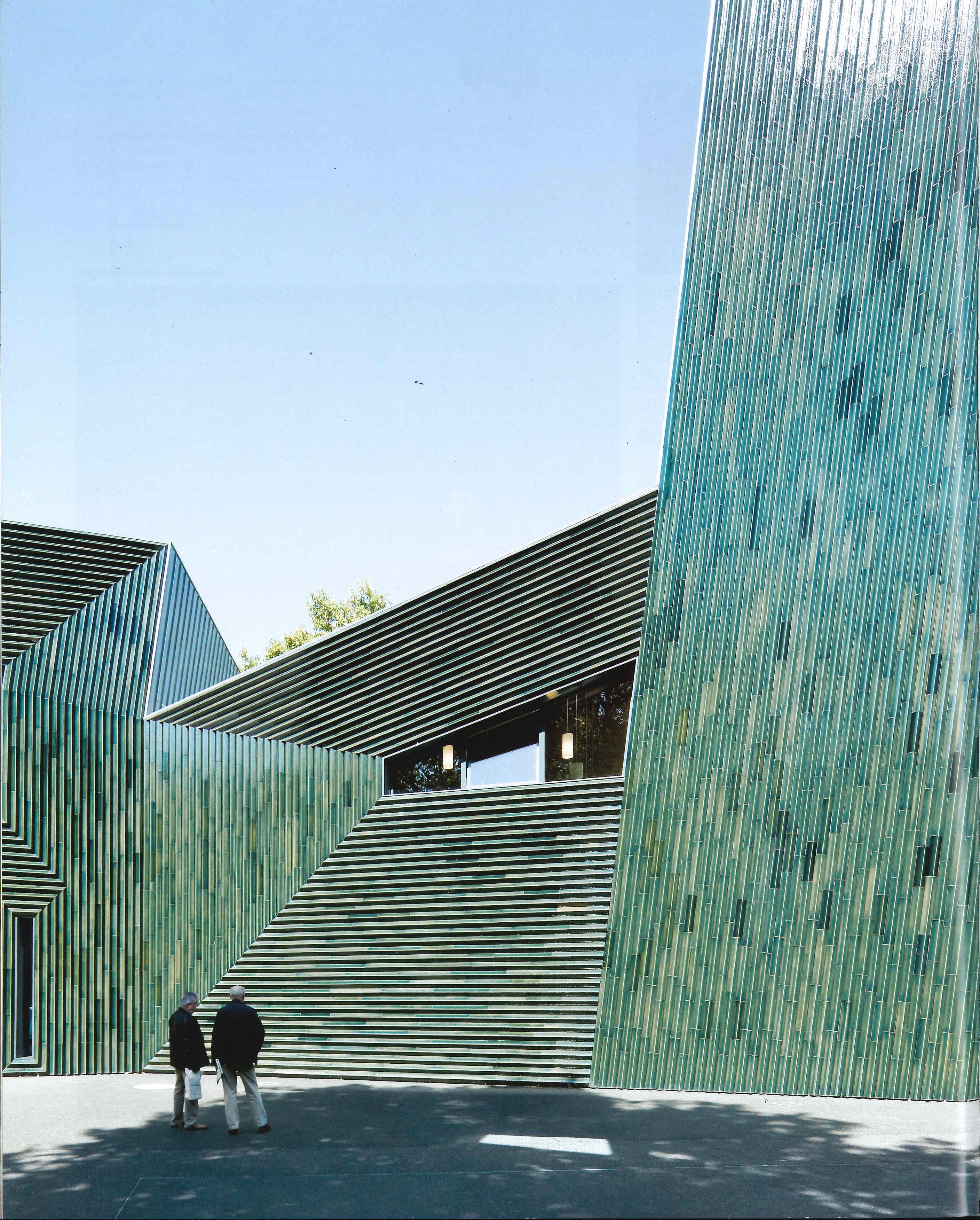

La fachada muestra el proceso de inscripción o tallado de un patrón, y está formada por una super ficie tridimensional de azulejos vidriados. El patrón está dispuesto de manera concéntrica alrededor de las ventanas y sugiere un juego de trampantojos, de manera que un conjunto de múltiples perspectivas con las ventanas como puntos de fuga emerge en la fachada. Esta calidad espacial se ve reforzada por el vidriado verdoso de los azulejos, que refleja la

luz cambiante del entorno por medio de un amplio registro de matices.

Las superficies interiores están revestidas con letras hebreas densamente empaquetadas que con forman un patrón de ornamentación ilegible, casi ilimitado y semejante a un mosaico. En ciertas partes, la densidad se reduce para que el texto pueda leerse. Fragmentos de los llamados piyutim —textos de poesía religiosa escrita por los rabinos de Maguncia en los siglos X y XI— se tallan en las superficies inte riores. Se trata de palabras muy puras y hermosas que narran el amor por la Torá aludiendo al Cantar de los Cantares o a la destrucción de la comunidad durante las primeras cruzadas, y muestran la importancia de Maguncia para el judaísmo. Son textos que celebran la producción cultural de la ciudad y, por extensión, el poder creativo de la diáspora judía.

40 2022 ArquitecturaViva 242

In the course of its history Judaism has never developed a strong tradition of building. Unlike other religions, it has not developed architectural styles that try to convey certain values and credos inspatial terms. Instead, there was text. In Judaism, writing can be seen as taking the place of spatial production. Specifically the Talmud, written after the destruction ofthe second Temple and the begin ning of the Diaspora, can be viewed as a response to the loss of Jerusalem as Judaism’s central place, as an answer to uprootedness in general, and as an alternative spatial model. The theme of space traverses the whole Talmud, from the content of individual chapters to the dialectical techniques of the rabbis (their methods ofarguing and debating), not to mention the very manner in which the text is written. Also, on the level of individual words and letters, an object quality is expressed in the writings. This object quality of writing, combined with the concept of the Talmud (which found its central place of learning in the city of Mainz) as a notion of space, informs the design of the Jewish community center of Mainz.

The facade shows the process of inscribing or carving a pattern, creating a three-dimensional

the building’s facade. This spatial quality is enhanced by the green glazing of the ceramic tiles, which reflects the shifting light conditions of the surroundings by means of a wide array of hues and shades.

The interior surfaces of the synagogue are shaped by densely packed Hebrew letters forming an unreadable, almost endless, mosaic-like orna mented pattern. In certain areas this density of letters is reduced, and the text becomes readable. Piyutim (religious poetry) written by the rabbis of Mainz in the 10th and 11th centuries are carved onto the surfaces of the synagogue. In a very pure and beautiful language they tell of love for the Torah, alluding to the ‘Song of Songs’ or the events around the destruction of the community during the first crusades, and reference the central role played by Mainz in the history of Judaism. They celebrate the cultural production of Mainz, and by extension the creative power of the Diaspora.

Lejos de ensimismarse en el interior de la manzana, el centro crea ante sí una plaza de barrio, perfilada por los planos facetados de una fachada vidriada cuya ornamentación se inspira en la caligrafía hebrea y en la escuela talmúdica.

Far from withdrawing inward, the complex creates a neighborhood square, formed by the faceted planes of a glazed facade decorated with inspirations from Hebrew calligraphy and the Talmud Torah school.

surface formed with glazed ceramic tiles. The pat tern is arranged concentrically around the win dows, resulting in a perspectival play of dimen sionality, in such a way that multiple perspectives with the windows as vanishing points emerge on