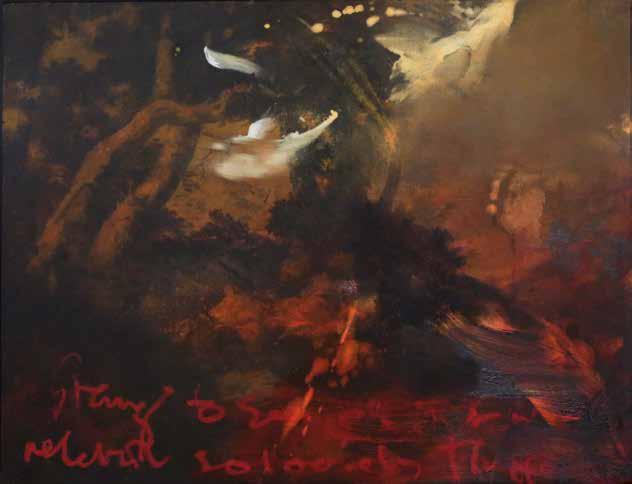

“Strange to see all that was once relation so loosely fluttering hither and thither in the breeze”

Rainer Maria Rilke

“Strange to see all that was once relation so loosely fluttering hither and thither in the breeze”

Rainer Maria Rilke

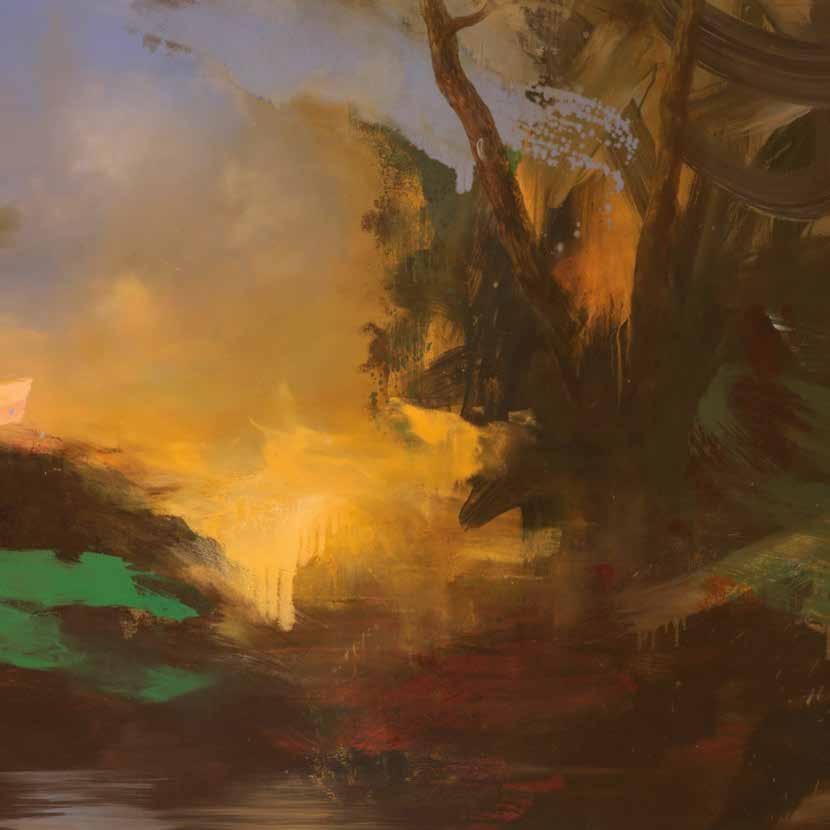

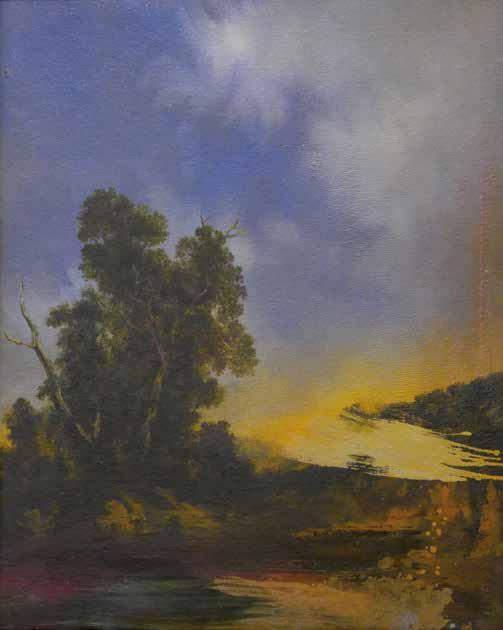

If you go down to the woods today, you might be in for something of a surprise, with dark disturbances insinuating their way through Arcadia’s rolling hills and fertile valleys. At first sight nature stretches out, bucolic, unchanging, idyllic, poetic, but look again at Alan Rankle’s work in his show, Pastoral Collateral, and his urgent messages soon become clear as he brings the past crashing through the now and into the future. Our natural surroundings become secondary, subordinate, collateral.

Rankle continues his preoccupation with revitalizing the tradition of landscape art within the context of our post-industrial, and arguably pre-apocalyptic, world.

In Rankle’s recent work, he seems to treat the whole history of landscape painting as a “found object.” He fuses aspects of Classical and Romantic painting with Abstract Expressionistic gestures; he paints trompe l’oeil elements as though from a 19th Century naturalist’s journal. He knowingly references conceptual asides to provide an undercurrent of contemporary unease. All these elements collide as portentous montages in the paintings, depicting a world splintering and fragmenting towards chaos, yet still evoking an eerie, and somehow threatening, illusion of harmony.

In 1998 Rankle said in conversation with writer and scholar, Anthony Wallersteiner, “My paintings represent re-workings of a single theme: that of a sudden encounter with a dark edge of water – a pond or river – on the outskirts of the city. A place reeking of desolation and the potential energy of decay,

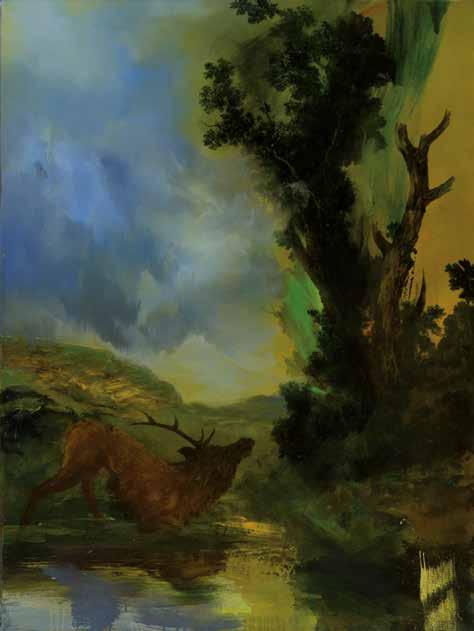

Study for River America 2012

Oil on canvas, Triptych each panel 84x60cm Collection Sam and Nadene Robertson

Courtesy Maerz Contemporary, Berlinthe meeting of urban and rural landscape.”

Now in the 21st Century that dark edge seems to loom somewhere between our whole planet and the abyss.

As with much of Rankle’s work this evolving series has a multi-layered aspect. The 2007 title Formal Concerns for example refers to the way abstract artists of the 1970s, when Rankle was a student, would distance their work from an involvement with so called ordinary life and political issues by using the term to describe their aims. It refers also to the belated pronouncement by the British Government’s Chief Scientist who recently expressed “Formal Concerns” on the subject of global warming.

To mark his place in the contemporary canon, Rankle could be described as a landscape conceptualist, influenced as he is by idiosyncratic and purposefully provocative artists of an earlier generation such as Antoni Tàpies, Joseph Beuys and Anselm Kiefer. You may ask yourself what do the fine art antics of these luminaries have to do with Rankle’s classical landscapes. You will not see Rankle lugging an old mattress out of a skip to create a sculpture like Tàpies. You will not see him sitting in a gallery window smearing his head with honey like Beuys. You will not see him piling up the surfaces of his canvases with dead flowers and broken glass like Keifer. Rankle’s conceptual and neo-expressionist influences are deeper and more subtle than all that, but they are, none the less, marked in many ways by the work of these artists. Like these avant garde provocateurs his work unarguably strives to reflect the world by distorting it radically for emotional effect, to excite the emotions,

change the status quo and ask questions, which only suggest more questions.

Tàpies worked to undermine traditional fine art with his use of unconventional objects, for instance for his Matter Painting he mixed marble dust and clay and incorporated found objects such as straw, string, paper and cloth. Rankle’s work is often not so far from this approach with his method of adding textures and materials such as sand, plaster, collaged found objects and gold. Like Tàpies he channels his concern for the social and political role of the artist. Tàpies took the use of found objects to a new level in the early 1970s with the use of buckets and furniture in his work.

Beuys fuelled passionate and often acrimonious public debate, and like Rankle was a master of publicity. In 1940, as a volunteer for the Luftwaffe he may, or probably wasn’t, wrapped in oil and felt after his plane crashed at the Crimean Front, but these visceral materials came to symbolize healing and survival, often seen in his provocative and magnetic work. In the same way the viewer is drawn into the mystic concept of a Beuys work, that same viewer is pulled into a Rankle landscape with its dark and edgy pools, stricken stags and infinite vanishing points.

Keifer studied under and was inevitably influenced by Joseph Beuys in Dusseldorf and Keifer’s subject, according to art historian Robert Hughes, ‘is the fatal collision of German and Jewish history… Keifer’s talent is for the motif, the image.’ Like Keifer, Rankle takes issue with the past, although Rankle’s history may be less loaded than Keifer’s, but the motif and the image carry his messages.

Like these material magpies, Rankle seizes fragments of a different kind from many places, not least art galleries, repositories of our collective memory. He shares Keifer’s concern with recent history, but goes further back in time. Rankle explains his own magpie methodology through the technique of pentimenti.

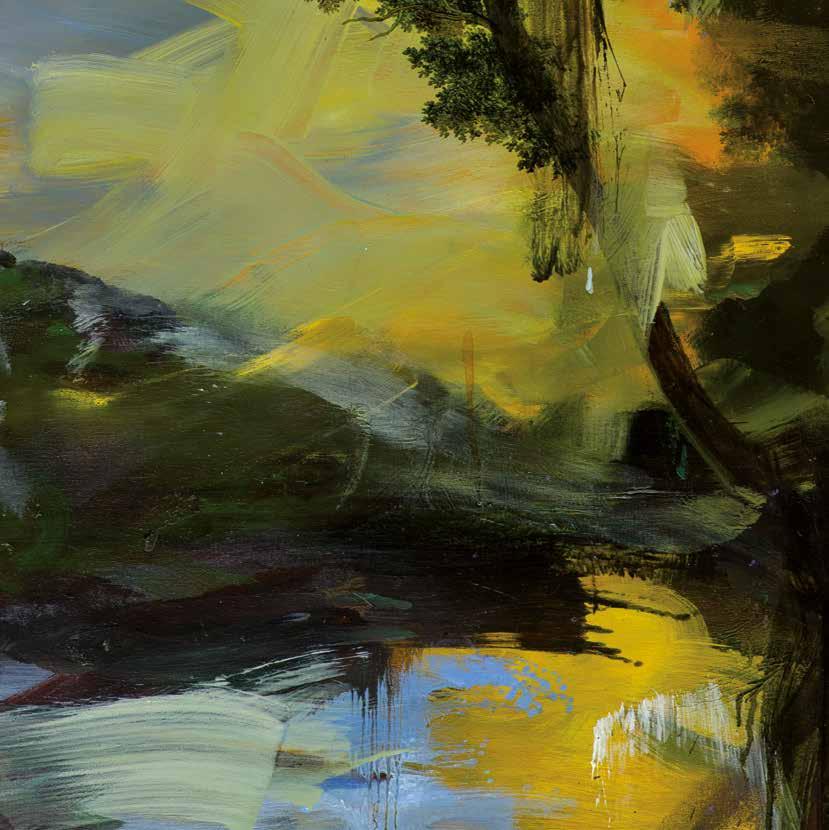

‘The virtuosity which became possible in oil painting with the beginning of the Venetian school, around the time of Titian, developed through many artists who inspired me, where the modern use of oil painting methods, wet into wet, glazing and scumbling allows a free spontaneously evolving way of creating the work.

‘Related to these historical techniques I decided to explore other ideas about the nature of painting. The illusions of pentimenti, which used on layered paintings are coming from observations on the way some Renaissance and Baroque paintings become more transparent with age to reveal the under-painting and also any changes and alterations the artist made on the surface of the canvas.

‘The painting may be read as an evolving presence – significantly sometimes a figure previously painted out emerges from the shadows years later; often a portrait can be discerned to have several expressions.

‘I find this an intriguing technique. It’s a metaphor for the effects of time in landscapes and for allowing the mystery of places and past events to be alluded to and of course it evokes such theatrical devices as sub-plots, undercurrents, hidden dealings and the implied ability to ‘re-write’ history as so many powers and shady characters have tried to do.’

Over the last four years Rankle’s work has intensified, it is more incisive and unafraid to address current events. His aesthetic demands ever deeper scrutiny. He says: ‘Ideas evolve as you go you expand your vocabulary, themes are revisited and you do things in different ways.’ Rankle’s landscapes may be created in the 21st Century, but their message is as clear as John Berger’s interpretation of Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews which was painted in 1750. True to his socialist roots, Rankle seizes left wing opinion on Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews commissioned by the couple. Mike Gonzalez in Socialist Review, December 2007, saw them as “complacent bourgeois farmers” with “safe landscapes neatly trimmed and fenced off behind”. As the art critic John Berger noted in his 1972 Booker Prize winning book, Ways of Seeing, Mr and Mrs Andrews are painted as “landowners and their proprietary attitude towards what surrounds them is visible in their stance and their expressions”. To be fair to Gainsborough these “complacent bourgeois” are indeed painted as complacent and bourgeois — and Gainsborough in this sense proves himself as an accomplished realist artist. This was the great age of the landscape gardener, designing manicured bucolic vistas. But the stance and body language of the Andrews could not be clearer, particularly that of Mr Andrews. He seems to say, ‘This is my land. This is my wife. This is my gun. This is my dog. This is my legacy.’ Note the unfinished area on Mrs Andrews’ lap which, it must be assumed, would eventually be filled in with an heir to the Andrews fortune. But overshadowing

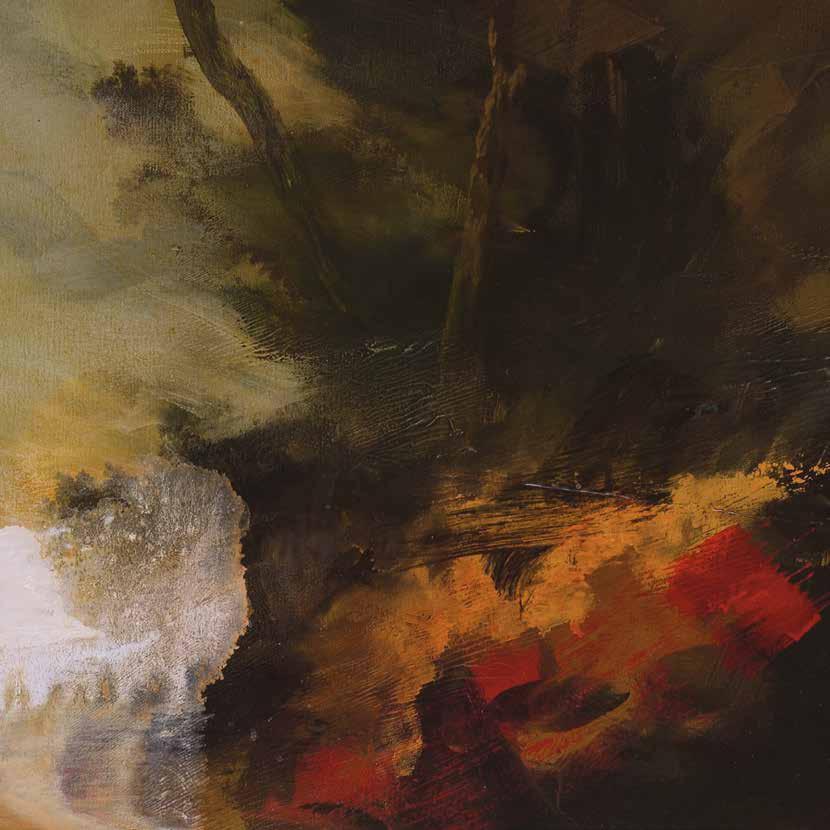

Montsegur 2011 Oil on canvas, 80x100cm

this patronage of the arts was the trade in slavery and environmental pollution.

Rankle is only too aware of current parallels with the past: ‘Much of my recent work reflects the sense of irony in how the money that created the Romantic movement came about. It started with the Enclosures Acts and the privatization of peoples’ livelihoods and the monetization of nature itself. Peasants were kicked off common land and went to work in the factories and mills. There was slavery on one side of planet and industrial, environmental and social pollution on the other. Today the equivalent of Blake’s ‘dark satanic mills’ are located in the Far East where low paid workers make iPhones and garments for western consumers. The working classes of Britain are themselves collateral damage.’

‘We are ignoring the desecration of nature in pursuit of more wealth for fewer people. Nature itself is collateral damage. The pastoral is the collateral.’

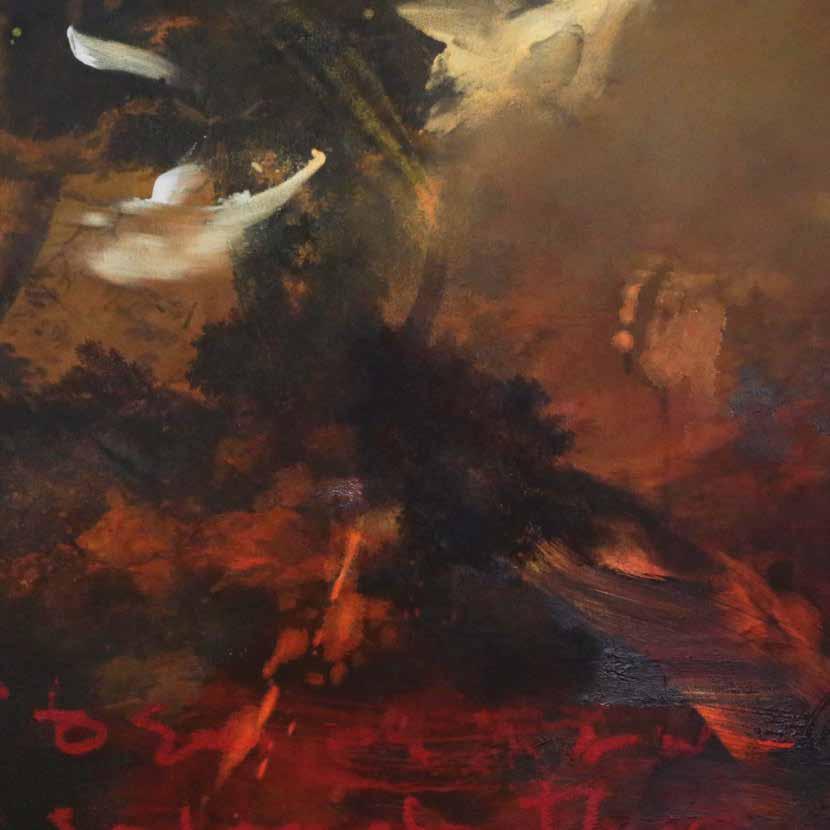

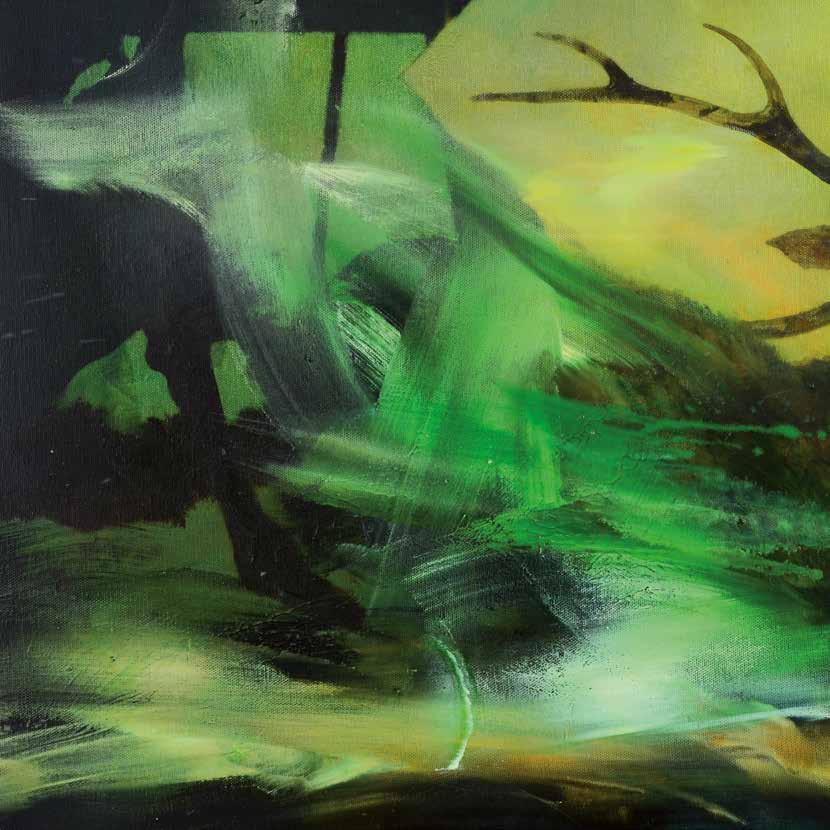

Rankle’s iconic and powerful landscapes have other, perhaps more subtle meanings hidden within their layers as the invisible becomes visible. In Untitled Painting XII (Herne) Rankle continues the theme from his 2009 exhibition at Hans Alf Gallery, Copenhagen Running from the House and develops the idea of Nature being ‘on the run’, a theme occurring in earlier works such as the Journey of the City to the Sea series of 1998.

In her catalogue essay Sarah Lloyd quotes Rankle discussing the painting, an image of a fleeing stag which he based on an unknown 19th Century artist’s work in the Musee de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris: ‘You see a stag

in the forest and in an instant it’s gone, like a phantom. My paintings are also about how images combine in the mind. I might be staring at the sea, but thinking about my mother. The physicality of paint embodies these ideas, painting can become an emblem of thought and memory as figurative elements disappear and reappear until they hold meaning. It’s one thing if the stag is running from a hunter, or a forest-fire or a loud noise, but now when nature itself is on the run, this is fear of another order, the stag is running, but the air and trees and snow are also running.’

In this work the stag itself is painted like a reverent historical study, before exploitation, as default, became the norm. Look again and Rankle has found the idea of this image on the canvases of history and he has supplanted it down in the woods, terrified, amid a flurry of abstracted water… blood… haze… pollution… confusion… collateral…

Judy Parkinson St Leonards-on-Sea 2016Oil on canvas, Dyptich 120x100 & 120x150cm Collection Sam and Nadene Robertson

Untitled (Herne Study II) 2015

Oil, pigmented inkjet on canvas, 66x88cm Collection House of St Barnabas

Running from the House Study I 2012 Oil, pigmented inkjet on canvas, 44x58cm

Federico Rui Arte Contemporania, Milan

Enigma: Ruisdael in

Oil on canvas, 50x40cm

Maerz

Enigma: Patricia Kalitzca + The Object of Change

Oil on canvas, 50x40cm

BORN

1952 Oldham, Lancashire

1968-70 Rochdale College of Art

1970-73 Goldsmiths’ College School of Art, BA (Hons) London

1973 The Pardonner’s Tale, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

1976 Landskip Reflections, University of Manchester

1982 Endless River Landscapes, Paintings Drawings Prints, Oldham Art Gallery & Museum

Landscape & Romance, Hastings Art Gallery & Museum

1993 Riverfall & Other Works, City Art Gallery Southampton

1995 Paintings, Beatrice Royal Contemporary Art, Eastleigh

1996 Landscapes for the North, Maidstone Art Gallery & Museum; Radicev Museum, Saratov, Russia

1998 Terre Verte, Danielle Arnaud/Clink Wharf Gallery, London

2002 Further Tales, Charles Everritt Fine Art/The Air Gallery, London

2003 Gates to the Garden, Galleri Sult, Stavanger, Norway

2004 For the Cave of the Sea, Rock-a-Nore Art Gallery, Hastings

2006 Light + Meaning Galleria Seriola, Tampere Strange Territory, Galleri Nordlys, Copenhagen

2007 Formal Concerns, Galleri København, Copenhagen

Landscapes for the Turning Earth, Gallery Oldham

2009 Running from the House, Hans Alf Gallery, Copenhagen

2010 Selected works, Fondazione Stelline, Milan

On the Edge of Wrong, collaboration with Kirsten Reynolds, Fondazione Stelline, Milan

2011 Alan Rankle Kirsten

Reynolds: Recent Works, Federico Rui Arte Contemporanea, Milan

Wilderness Approaching, Gallery B15, Copenhagen

2014 Rankle & Reynolds: On the Edge of Wrong, The Underdog Gallery, London

2015 To a Hidden Place, The House of St. Barnabas, London

2015 Enigma, Casa sull’Albero, Lake Como

2015 Lost Horizon, Maerz Contemporary, Berlin Enigma, Federico Rui Arte Contemporanea, Como

2016 Pastoral Collateral, Art Bermondsey Project Space, London

1975 SPACE Open Studios, Charlton House, London

1982 Andy Goldsworthy/Michael Jepson/Alan Rankle, LYC Gallery, Cumbria

1985 New Figurative Works Patrick Boyd-Carpenter, London

1988 Order out of Chaos, Artists Unlimited, Bieldefeld, Germany

1990 Travel: Real & Imagined Journeys, Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne

1991 Earthscape, Hastings Pier

1995 Driven to Abstraction, Rye Art Gallery

Arcade, Brighton University Gallery Inspirit Maidstone Museum & Art Gallery

1996 A Different Pursuit, Danielle Arnaud, London

Endangered Spaces, Christies, London

1997 The Best of British, Musée de Prieure, Honfleur, France

1998 Downs & Marsh, Folkestone Art Gallery & Museums Sublimate Sublime Subliminal, Clink Wharf Gallery, London

2000 Serena Banham, Per Fronth, Alan Rankle, Anderson

Stewart Fine Art, London Art in Romley Marsh, St Mary in the Marsh

2006/7 Landscapes for the Turning Earth, Gallery Oldham, Greater Manchester

2006/7 On the Edge of Arcadia, Installation with Tom Burke, Tim Nathan, Colin Gibson, Kent Barker, Gallery Oldham, Greater Manchester

2009 Klimakunst på Bestilling, Hans Alf Gallery, Copenhagen

2011 Rankle & Reynolds, Enrico Savi: Empathy and Abstraction, Mya Lurgo Gallery, Lugano Iconoclasts, curated by Katie Heller, The Lloyds Club, London

Layers of Landscape, Touchstones Rochdale

2012 Wild Bleibt Wild, Haftentor 7, Hamburg

Paddaggi Animati, Castello di Mornico, Mornico Losana

2013 32 Paintings, Phoenix Art Centre, Brighton

Axis: Copenhagen – London, 24/8, London

Looking at Landscape: Pastoral to Present, Gallery Oldham

Multiplied 2013, Christie’s, London

2014 RELATIONS(s), Art Stays

2014, Ptuj, Slovenia

How the Light Gets In, Galleri Aveny, Gothenburg

Arte Padova, Federico Rui Arte Contemporanea

2015 The Collective, House of St Barnabas, London

2015 On Paper, Lucy Bell Gallery, St Leonards-on-Sea

2015 Point of Decay, Coastal Currents Festival, St Leonards-on-Sea

Southampton City Art Gallery

Hastings Art Galley & Museum

Oldham Art Galley & Museum

Bankfield Museum, Halifax Calderdale Museums

Fondazione Stelline, Milan

Blackburn Museum & Art Gallery

Stellar International Art Foundation

Hammerson plc

Baker McKenzie plc

PriceWaterhouseCoopers plc

Sun Alliance plc

Bain Capital London

Thames Water plc

Tonbridge School

Southampton Hospital Trust

Chemical Materials Recycling (UK) De Lessac Settlement

Arc & Thostle Press

Paintings in Hospitals

COMMISSIONS

Sun Alliance plc

J Sainsbuy plc

Coutts & Co

Chemical Materials Recycling (U K)

Afia Carpets

Robertsbridge Community College

Hastings Trust Tonbridge School

Hastings Urban Conservation Project Exxon Chemicals