First published in 2017 by Sansom and Company, a publishing imprint of Redclife Press Ltd., 81g Pembroke Road. Bristol bs8 3ea www.sansomandcompany.co.uk info@sansomandcompany.co.uk

Published in conjunction with the exhibition ‘Capture the Castle’, 26 May–2 September 2017, Southampton City Art Gallery, Civic Centre, Commercial Road, Southampton so14 7lp www.southamptoncityartgallery.com

Book and exhibition have been made possible with the support of:

© `e contributors

isbn 978-1-911408-05-5

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. Except for the purpose of review, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Design and typesetting by E&P Design

Printed and bound in the Czech Republic by Akcent Media

Frontispiece: Kenneth Steel, Durham [detail]; see page 107

Acknowledgements 6 Foreword 7 Stuart Southall Introduct Ion 9 Tim Craven cAstles A nd br It Ish l A ndsc A pe A rt 14 Sam Smiles cAstles cur Ated 18 Roy Porter t he c Astle In medIevA l engl A nd 23 Andy King buIldIng cAstles In the AIr 28 Anne Anderson lInes oF deFence 33 Steve Marshall cAtA logue 47 Steve Marshall Index 173 contents

Acknowledgements

Southampton City Art Gallery would like to thank the following:

• Stuart Southall and the Punter Southall Group for their great generosity in funding this publication.

• Friends of Southampton’s Museums, Archives and Galleries for their continued support of arts and heritage in Southampton.

• All of the contributing artists and lenders for kindly allowing their work to be included within the catalogue.

• Tim Craven and Steve Marshall, co-curators of the exhibition, Dan Matthews and Jess Whitfield for the catalogue production.

• Anne Anderson, Andy King, Steve Marshall, Roy Porter and Sam Smiles for contributing fine essays to the catalogue.

• All at Sansom & Co, including project manager, Clara Hudson, and Ian Parfitt for the catalogue design.

• Exhibitions, Conservation and Learning staf at the City Art Gallery: Dan Matthews, Jess Whitfield, Stu Rodda, Andrew Ball, Rebecca Moisan, Ambrose Scott-Moncrief, Benedict Hall, Joseph Hill, Richie Gooding, Caroline Piper and Kate Mitchell.

• Brynn Jones and Mike Evans at English Heritage.

• We thank UNIQA for supporting Southampton City Art Gallery, by providing insurance cover for the city’s world-class collection (www.artuniqa.at).

All efort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders for the reproductions included in this publication. In cases of errors or omissions please contact the publishers so that we can make corrections in future editions.

6 capture the castle

L IKE T IM C RAv EN, WHo SE INTRoDUCT oR y ESSAy oPENS THIS catalogue, I have vivid childhood memories of a castle obsession. My mother still speaks of a Welsh holiday when exploring castles was all I wanted to do and a generation later I had the same experience when my own son spent a day roaming the impressive fortifications surrounding Avila in Spain.

`is catalogue and the accompanying exhibition contain a cross-section of castle images from my print collection and, as I was reviewing possible candidates for inclusion, I realised just how frequently such scenes had captured the artistic imagination, both in the UK and further afield. In some cases, such as in the works of F.L. Griggs, the castles are almost entirely imaginary; in others, for example, the multiple images of Corfe castle, reality transcends the imagination producing views of mesmeric mystery.

Why a financial conglomerate might want to sponsor an exhibition on castles may be less clear. But perhaps the many castles still standing, and constantly engaging the interests of new generations, speak volumes for long-term wellbeing founded on sound investment decisions, protective strategies and forward thinking.

All a bit tenuous no doubt but, as the exhibition sponsor, the Punter Southall Group would like to congratulate Southampton City Art Gallery on producing a fascinating and innovative show and we hope it is greatly enjoyed by all its visitors.

Stuart Southall Co-founder, Punter Southall Group

capture the castle 7

Foreword

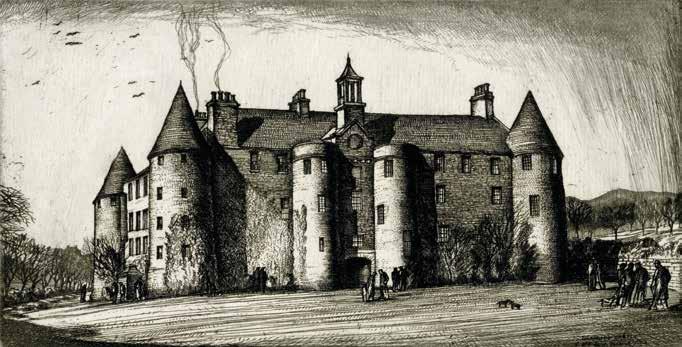

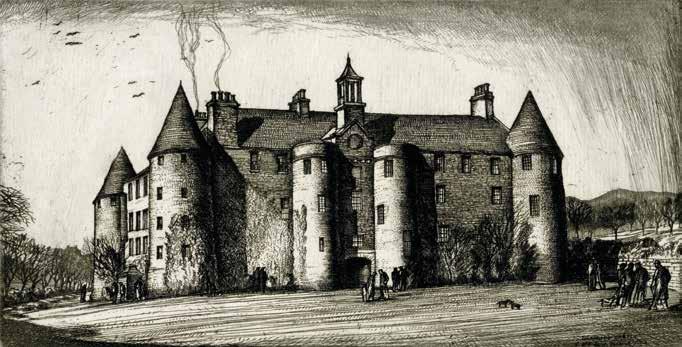

Sydney R. Jones / Durham / 1924 / etching / 163 x 172 mm

Stuart Southall collection

8 capture the castle

Introduct Ion

tim craven

IT ALL STARTED WHEN I READ MARC MoRRIS’S excellent book on King Edward i a few years ago. `is prompted a summer holiday in Snowdonia planned specifically to see his world-class, big-four castles (Conwy, Caernarfon, Harlech and Beaumaris). `e expedition rekindled my boyhood love of exploring castles and first sight of Conwy Castle was a jaw-dropping moment that remains vivid in my memory. Its powerful and brooding presence dominates a stunning location and the others were equally impressive. `e nearby native castles, though sited in strong, strategic places and appearing utterly romantic are puny by comparison, emphasising the unstoppable brute force of Edward i’s military campaigns in Wales. `ese relics of a long distant age still possess an intangible and potent force.

Later I related these experiences to the celebrated artist Graham Arnold who has long employed castles in his paintings and he announced that he would like to paint another one. Immediately I thought – perhaps I could paint a castle and because my mind works that way – is there an exhibition? For a long time though I believed that the subject was too specialist, too boys-own to enjoy universal appeal, but gradually, through sharing these ideas with friends and other artists I realised how wrong I was. `e resulting exhibition that accompanies this publication is the first major artistic project of its kind in recent times, relating the story of the castle from early times until the present through historic and contemporary paintings, prints and drawings. History is entwined with art.

Everyone it seems, loves castles. `ey exhibit an exceptional visual wow factor. No wonder Disneyland’s brand image is a fairy-tale castle, the associations are magical and exciting. Steeped in history and legend, many of these extraordinary buildings exude a compelling and dramatic magnetism. `ey are the stuf of knights in shining armour, derring-do, highborn heroines and deep scary dungeons. Part of the fabric of our land, they conjure up a past of high adventure and royal intrigue that we can only imagine. A chasm of understanding though now exists between their original functions and our present perception of castles as tourist attractions, leisure amenities and picnic-sites.

Castle visiting is more popular than ever and is big business. English Heritage manage around 400 sites of which 90 are

castles and attract over 4 million visitors each year. We expect as standard, certainly for the larger castles, a visitor centre, shop and café, and our experience is carefully orchestrated with audio guides and text panels. `e souvenir guide books relate how castles were rediscovered in the late eighteenth century after more than a century of neglect and ruination, by antiquarians, poets and – artists.

Turner and Constable, Britain’s greatest artists, Girtin, de Loutherbourg, Cotman, Ibbetson, Sandby, varley and many others travelled to castles throughout Britain in the search of the Picturesque and to make paintings as they were popular and sold well. Turner in particular painted many, he loved them. His Royal Academy diploma painting was Dolbadarn Castle, bigged-up to catch the eye. Castles were the perfect subject for the pre-eminent, high Romantic Movement of the early nineteenth century that embraced the heroic past. Artists are even part of the castle story, for the subsequent and related Gothic Revival architecture spawned a new wave of castle building and restoration such as Castell Coch in South Wales. Edwin Lutyens’s famous Castle Drogo, perched high on the edge of Dartmoor, was built in the early twentieth century, and in the 1940 s, Neo-Romantic artists such as John Piper and John Minton returned again to the subject.

Why were, and are, castles so attractive to artists? `ey are unusual and fascinating buildings, of irregular, strange shapes; they are full of mystery, history and association. Castles have become ruinous and their relationship with encroaching nature is an especially rich, visual seam for artists to mine. Wigmore Castle near Ludlow for instance, the home of the once mighty Mortimers, is managed by English Heritage especially as a nature reserve and the tumble-down walls and towers are so enmeshed in vegetation that it is hard to work out what the castle might have looked like. Perhaps the supreme reason for the attraction is that, as Norman Ackroyd ra pointed out to me, they were built in the most spectacular and dominant locations, and so have been irresistible to artists in search of an eye-catching composition. Castles were always meant to be highly visible. Dryslwyn Castle for example, due east and close to Carmarthen, sits on a most impressive, craq hilltop and perfectly commands the beautiful Tywi valley below. When castles were upgraded with the newest military features by later kings and barons, they rarely needed to be re-sited as

capture the castle 9

the Normans had always chosen the best possible sites – so good was their military knowhow and eye for country. Most castles therefore have been much modified over the years and are an amalgam of architecture of diferent ages.

As this exhibition illustrates, castles are also usually surrounded by hills, trees and water, all proper ingredients for an enticing pictorial drama:

`e di f erent combinations of the ruined towers of the castle with the fine trees immediately surrounding it, and with those of the foreground o f ered a succession of the richest and most beautiful compositions. sir richard grenville, 1801

Water especially was an essential part of a castle’s entity and survival plan and it is worth expanding upon this vital relationship for a singular insight into a castle’s modus operandi Now, there is nothing more enchanting and evocative than a moated medieval castle, but the present romance is far from the historic reality. Castles could be fearsome places and moats were stinking, death-trap sewers, the daily receptacle for the castle toilets (garderobe) and other nasty detritus. `e term moat derives from motte, the Norman word for a mound –the common early castle design being the motte-and-bailey. Initially the ditches were dry, but if the ground was low and marshy as at Berkhamstead, then they would fill with mud and water and their defensive properties were soon recognised and exploited; they could be designed with steep sides and filled with pointed wooden stakes. Roads were often so poor that the best way to transport goods was by river and coast. Castles such as Kidwelly and Bramber were sited at estuaries and river crossings to control access. others were built by the sea to ensure water-borne re-supply during sieges as at Harlech.

A most impressive engineering feat at Rhuddlan in the late 1270 s was the diversion and canalisation of the River Clwyd for a distance of over two miles to provide a deep-water channel from the sea to the castle so that supplies could be easily shipped from the coast. If possible, castles were sited over springs or underground streams. often one of the most expensive features, wells were a vital source of water and were marvels of medieval engineering and they could take many years to sink to the water table. Some castles incorporated sophisticated piping systems and cisterns to draw water to upper floors. Any water supply though that could be tampered with from outside the castle would invariably be poisoned with a rotting corpse by besieging forces, in order to encourage an early garrison surrender. Fire was used with devastating success against castles (hence the term ‘with fire and sword’) and well-water was a vital countermeasure in addition to a drinking supply.

Moats also prevented undermining, one of the great fears of any castle garrison and famously used by King John at Rochester in 1215. Miners would dig a tunnel under the wall which was then collapsed bringing the masonry above down with it. Defenders would place wide bowls of water in strategic places and watch for any vibration on the surface that would indicate digging below. `e only answer was to countermine and meet the enemy threat underground – a dangerous and scary ploy that was used in desperation on occasion. A castle built upon rock, as at Conwy, was of course safe from this devious tactic.

Among others, Caerphilly and Kenilworth Castles developed extensive water defences and became almost impregnable. Established as a motte-and-bailey by Henry i, Kenilworth was rebuilt by King John in 1200 on the side of a valley with a stream at its bottom. `is was ingeniously dammed in order to flood the entire valley and when the north-east walls were protected with a deep new moat, the castle became an island. It was tested in 1265 after the Battle of Evesham when Simon de Montford’s son, holed up in the castle, refused to submit to the King and the subsequent siege lasted from Easter until December. Prince Edward collected a variety of siege engines, including a great tower called Bear, and barges were sent down from Chester for deployment on the water. Abandoned by their allies and a lost cause, the starving garrison eventually surrendered on terms and were allowed to march out with full honours. `e defences though had survived everything the wealth of the kingdom could throw at them and had proved to be the business.

With the decline of the castle’s original dual function as both fortress and lordly residence from the fourteenth century onwards, the role of the moat changed and they were now employed largely for prestige purposes. Dunstanburgh Castle, famous for its last word in gatehouse-keep design, was originally surrounded by a network of artificial lakes, though these are not much in evidence today. Useful for keeping wildfowl and fish for the garrison, the predominant purpose of these bodies of water must have been for their outstanding visual impact rather than for defence. `e long and meandering pathway around the meres that lead up to the castle suggest that it was designed to exaggerate its appearance. `e multiple, mirror-like reflections of the magnificent and powerful architecture were supposed to overawe any visitor. At Bodiam too, where the castle dramatically rises from the middle of a wide moat, exactly the same efect is achieved. `e give-away here is that the moat edges are in-part banked up so that it could easily have been drained by any attacking force.

By the time of the Gothic Revival castles of the nineteenth century such as Eastnor, surrounding water, now usually a lake, was an entirely decorative feature but thanks to plumbing not quite so foul-smelling. `ese so-called castles can be frivolous, eccentric and even deluded; I well remember feeling distinctly short-changed when promised a trip to a castle as a boy, I was confronted by a big country house topped with feeble battlements. Restored castles too like Windsor or elements of Pembroke, Arundel and Caerphilly seem somehow unsatisfactory and almost fake. `ere is nothing to rival the physicality and raw environment of the real thing, however dilapidated. `e detective work required to read a ruined castle and understand how it functioned can be honed by lots of exploration. It can be addictive.

I hope that this exhibition will spark the imagination and encourage castle visiting. Look out for those small and often overlooked or fragmented architectural details that reveal the military and domestic conventions of the day and give insight into the ingenious medieval engineering achievements of the castle-builders. `ough we know few of their names today (Savoyard, Master James of St George was Edward i’s famed architect), we salute them with this exhibition.

10 capture the castle

introduction 11

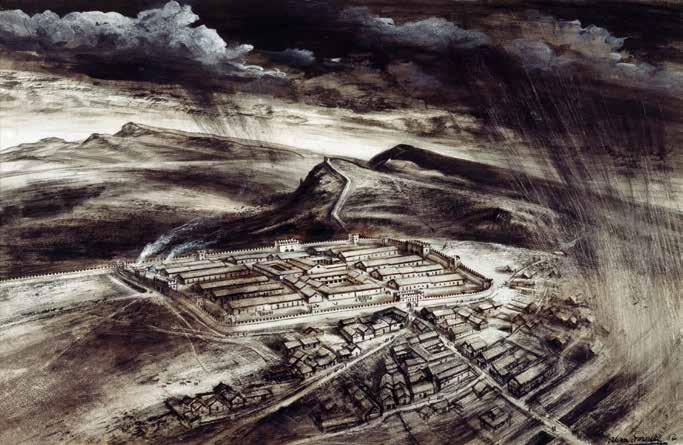

William Wilson / Edinburgh / 1928 / etching / 131 x 165 mm

Stuart Southall collection

12 capture the castle

sebastian pether (1790–1844)

moonlight scene, southampton

oil on canvas / 1500 x 1980 mm

Southampton Maritime and Local History Collection

Southampton Castle dominates this tranquil view of the town towards its southern and western walls. Constructed in the eleventh century, the original motte-and-bailey castle was rebuilt in stone and extended several times. `e Castle was at its strongest around 1400, the key to the defences of one of England’s richest and most important seaports. However, the castle fell into disuse during the fifteenth century as the defence of the town focused on the town walls, and the castle began to sufer from neglect. only fragments of the building exist today, including some of the wall foundations and a part of the Castle Hall and vault.

capture the castle 13

c Astles A nd br It Ish l A ndsc A pe A rt c.1750–1950

sam smiles

TH E DEPICTIoN oF CASTLES IN BRITISH ART has a very long early history, from idealized presentations in medieval manuscripts, through the more accurate notations of surveyors and topographers in the Tudor era to their presentation in the landscape paintings of the seventeenth century. `e majority of these early images depict buildings in everyday use; few of them are concerned with ruined structures. However, the Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar in the mid-seventeenth century and, following him, Francis Place, the first English artist to develop landscape as a specialist pursuit, included depictions of ruined castles as well as inhabited ones in their works and their example may be taken as the beginning of the modern fascination with castles.

As part of the national scene, medieval castles had the potential to be incorporated in landscape images but their inclusion was not inevitable, nor did their presence always signify the same thing. `ey might be regarded as architectural curiosities, as relics of feudalism, or as symbols of a lost chivalric sensibility. What unified these newer representations was a sense of the castle’s increasing separation from the modern world. Up until the seventeenth century castles could still be regarded as capable of fulfilling their original function and many of them were garrisoned during the Civil War. By the close of that century, however, what a castle stood for was becoming associated primarily with an epoch that was fast retreating into history. Although some were still inhabited, and could be further improved for domestic comfort, their ruined equivalents represented a world that had vanished entirely.

one of the earliest attempts to make extensive visual records of castles was Samuel and Nathaniel Buck’s survey of medieval architecture in Britain. `e prospectus was issued in 1726 and by 1742 they had recorded many of the castles in England and Wales, which appeared among over 400 designs in their series Views of Ruins of Castles & Abbeys 1 `is pioneering venture was intended to be topographical and informative and, in that respect, it is rather unjust that it would later be criticized for its artistic limitations. `e Bucks’ presentation of these buildings is admittedly prosaic but the imperative that motivated the project was to record them before they were destroyed or altered beyond recognition. As the prospectus stated, the engravings would ‘rescue the mangled remains’ of ‘these aged & venerable edifices from the inexorable jaws of time.’ 2

In the second half of the eighteenth century topography was increasingly in dialogue with landscape painting which, as a genre, would develop into something that encouraged the most ambitious creative eforts. Inevitably, the topographer’s need for accurate notation became of much less significance when aesthetic criteria became the norm for judging the quality of an image. Initially, however, the tension between these two ways of approaching landscape was much less marked and Paul Sandby’s `e Eagle Tower at Caernarfon is, in that respect, a transitional work (see page 134). often regarded as the founder of the British watercolour school, Sandby’s skilled use of the medium helped demonstrate its artistic potential. At the same time, much of his work in Wales was published as a series of aquatinted topographical views in the 1770 s and 1780 s, including the Eagle Tower.3 Much the same balance of priorities between topography and fine art practice can be seen in `omas Hearne’s watercolour of Newark Castle (see page 135). Painted in 1777, it was engraved in Hearne’s topographical publication Antiquities of Great Britain in 1796. Hearne produced several versions of the subject and a larger version of this composition was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1793.

`e dialogue in works like these between artistic and topographical understandings was challenged by more resolutely aesthetic approaches. `e Revd William Gilpin was the chief theorist of the Picturesque movement, publishing a number of books in the last quarter of the eighteenth century on the appreciation of landscape and championing an aesthetic that lay between the sublime and the beautiful. Gilpin celebrated visual variety, broken forms and intricacy, and for that reason he preferred his castles, real or imagined, to be ravaged. For example, he considered that Raglan ‘owes its present picturesque form to Cromwell; who laid his iron hands upon it; and shattered it into ruin.’ 4 But there were limits. As he noted at Brecknock, for a castle to be appreciated, to be still ‘a ruin of dignity,’ some sense of what it had once been needed to remain visible. He went on,

In many places indeed these works are too much ruined, even for picturesque use. Yet, ruined as they are, as far as they go, they are very amusing. `e arts of modern fortification are ill calculated for the purposes of landscape. `e angular and formal works of Vauban, and Cohorn, when it comes to their turn to be superseded by works of superior invention, will make a poor figure in the annals of picturesque

14 capture the castle

beauty. No eye will ever be delighted with their ruins: while not the least fragment of a British or a Norman castle exists, that is not surveyed with delight.5

Gilpin’s approach was doctrinaire, prioritizing landscapes that worked as pictorial compositions. Needless to say, his unrelenting elevation of aesthetic responses was vulnerable to satire. In `e Tour of Dr Syntax in Search of the Picturesque, William Combe made fun of it, even paraphrasing Gilpin’s remarks.6

`e eponymous and hapless hero of Combe’s poem hears how a violent thunderstorm has ruined the possessions of the villagers in whose inn he is lodging. Indiferent to their loss, he learns from his innkeeper that something of much more interest to him has also been struck by lightning.

‘ `e castle by the river side; A famous place, where, as folks say, Some great king liv’d in former day: But this fine building long has been A sad and ruinated scene, Where owls, and bats, and starlings dwell,And where, alas, as people tell,

At the dark hour when midnight reigns, Ghosts walk, all arm’d, and rattle chains.’

‘Peace, peace,’ said Syntax, ‘peace my friend, Nor to such tales attention lend.

– But this new thought I must pursue: A castle, and a ruin too;

I’ll hasten there, and take a view.’ 7

Combe’s choice of a castle as a focus for Syntax’s obsessions is thoroughly appropriate, given how often Gilpin described

castles in picturesque terms. Moreover, Syntax’s behaviour is shown to be blinkered, elevating visual appeal over social and historical understandings. But his aesthetic strait jacket is his undoing; in his search for the best composed view of the ruins he slips and tumbles into the river.

`e concentration of the picturesque on the purely visual was qualified by others who insisted that the mind’s response to the world necessarily involved a wider register. one of these was Archibald Alison whose Essays on the Nature and Principles of Taste (1790) argued that aesthetic reactions were not merely responses to formal features but were prompted by the beholder’s state of mind and its train of memories. In short, the historical associations of a place could afect the beholder as profoundly as its observable features. With respect to castles, in particular, Alison declared

`

e Sublimest of all the Mechanical Arts is Architecture, principally from the durableness of its productions; and these productions are in themselves Sublime, in proportion to their Antiquity, or to the extent of their Duration. `e Gothic Castle is still more sublime than all, because, besides the desolation of Time, it seems also to have withstood the assaults of War.8

To include a castle in a work of art was therefore to engage with the past, whether that be by invoking some of the historical events associated with the building, or simply by responding to the depredations of time as medieval masonry slowly succumbed to the elements. From Alison’s point of view, anyone looking at, say, Julius Caesar Ibbetson’s painting of Carisbrooke Castle (1787), with a diminutive figure approaching the massive towers of the gateway, would have had their appreciation

capture the castle 15

`omas Rowlandson / Dr Syntax Tumbling into the Water © The British Library Board (cup.410.g.425, opposite page 71)

coloured by what they knew of the imprisonment of Charles i in this place, shortly before his execution (see page 130).

Alison’s thoughts on the sublime should also be considered. He uses it in the context of the durability of castles, capable of resisting assaults from war and time itself. In the mideighteenth century Edmund Burke had characterized the sublime as ‘the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling,’ associating it with phenomena which ordinarily would occasion terror but which could be made agreeable once the actual danger was removed.9 Alison’s usage shows how by the century’s end the word sublime had become a catch-all term that stood for exceptional phenomena of various kinds. In the visual arts it was principally associated with the exaggerated efects of rugged terrain, wild weather, soaring height and vertiginous depth that many artists had made their own. Girtin’s watercolour of Bamburgh Castle is a good example of that tendency (see page 139). `e shattered ruins cling to a rock high above the sea, the drop made apparent by the seagulls floating in the air, and the viewer is invited to imagine the precarious ascent up the stone staircase on the right as threatening storm clouds mass above.

Girtin’s contemporary, J.M.W. Turner, also found creative stimulus in castle subjects. Castles were a feature of the first oils and watercolours he exhibited at the Royal Academy in the 1790 s, all of them derived from trips he had made to the north east of England and to Wales. `ereafter the majority of his depictions of castles, over 100 of them, were painted in watercolours alone, most of them commissioned to be engraved in the various topographical series to which he contributed. `e most important of these for castle subjects was Picturesque Views in England and Wales (1827–38), over a third of whose designs contain them. Ten of the eighteen engravings in `e Rivers of England (1823 –27) also include castles. Turner’s watercolour of Norham Castle on the Tweed was one of the first to be engraved in that series (see page 138). He had first visited the castle in 1797 and it was a recurring feature throughout his career from his first watercolour of it in 1798 to his unfinished oil of c.1845. He had visited Rochester even earlier, in 1793, and returned to it two decades later to make studies for this watercolour, which was also engraved in `e Rivers of England (see page 70). Both watercolours show the extent to which the older topographical tradition had given ground to an approach to landscape painting that was as much concerned with colour and efects of light as it was with architectural exactitude.

As would be expected of a watercolour artist born in the late eighteenth century, John Sell Cotman depicted numerous castles in his oeuvre, beginning with one of his first exhibited works at the Royal Academy. Cotman’s architectural studies are characterized by their exactitude but, like Turner, his approach is insistent on the image’s coherence as a work of art, as opposed to its complete subordination to topographical accuracy. He visited Wales in 1800 and 1802, making drawings on the spot, but watercolours like this one of Powis Castle (see page 140) were worked up later and are striking in their use of relatively flat colour patterning to articulate the composition.

Josiah Whymper’s Richmond Castle in yorkshire (see page 73) dates from the year he was made a full member of the New Society of Painters in Water Colours. It is a good example

of the development of watercolour painting at mid century, taking its cue from the experiments of Turner and his contemporaries and working proficiently in what had become a British speciality. As a romantic ruin Richmond Castle had already been the subject of numerous artistic interpretations, including works by Sandby, Girtin, Turner and Cotman. Whymper’s presentation of the castle, as a relatively distant object, maintains this tradition. In any case, a closer view might perhaps have compromised its romantic appearance, insofar as parts of the castle had recently been modernized to accommodate its new function as the headquarters of the North york Militia.

`e pressure of modernity was increasingly a factor determining attitudes towards these buildings. `e late nineteenth century saw a number of initiatives develop to protect the historic heritage of Britain, with the establishment of William Morris’s Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (1877) and the National Trust (1896) and the passing of `e Ancient Monuments Protection Act (1882).10 Previous generations had regarded castles as features in a landscape, redolent of history and identity but susceptible to inevitable decay if no more adequate use could be found for them. Now they were o2cially listed as monuments to be preserved. `is new context necessarily afected their artistic treatment. Heywood Sumner’s watercolour of Badbury Rings (see page 52), in Dorset finds something of its meaning in this new respect for the monuments of the deep past. His early artistic oeuvre, from the 1880 s, is associated with the Arts and Crafts movement but by the 1910s he had turned to archaeolon and this watercolour is a product of both approaches.

`e artistic presentation of castles in the modern age brings into sharp focus their increasing distance from contemporary life. `e most successful images made of them in the twentieth century were made by artists associated with the etching revival, maintaining a link with earlier representational strategies at a time when the high modernism of Cubism and other contemporary art movements seemed to propose a clear break with the past. Frederick Landseer Griggs, for example, etched numerous subjects of invented medieval buildings and towns in a deliberately nostalgic evocation of a lost world. `e Quay shows an idealized townscape in which elements of civilian, military and religious life are all visible (see page 150). `e castle on the hill is interlocked with the town it defends, asserting the integral nature of medieval society. Griggs believed strongly that the modern world was discordant and material, unlike the harmonious and spiritual culture of the middle ages. `e Quay, as with similar images by him, is essentially a rebuke to modernity.

In both technique and subject matter Philip Wilson Steer’s oil painting of Chepstow Castle (see page 69) is also deliberately traditional. Steer had abandoned his earlier quasi-Impressionist approach to modern subjects, as seen in his paintings of the 1880 s and 90 s, and repositioned himself as the heir to Turner and Constable. `is view, for example, is very similar to the one published by Turner in 1812 in his Liber Studiorum, a miniature edition of which Steer took with him when making sketching tours.11 Steer’s invocation of tradition is worth remarking. Artists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries included castles in paintings that were as advanced as anything else being produced at the time. In contrast, Steer

16 capture the castle

seems to have chosen a castle subject precisely because it was traditional. `e artistic experimentation of the early twentieth century English art world tended to focus on the modern city and its new ways of life, not on these relics of the past.

McKnight Kaufer’s poster of Bodiam Castle (1932) (see page 101) reveals how the architectural heritage of castles was increasingly associated with leisure activities. `e Shell campaign selected landmarks that typified the variety and interest to be found in the British countryside, celebrating its deep history while simultaneously demonstrating how the petrol engine made it more accessible than ever. Much of McKnight Kaufer’s poster output for Shell and other companies made brilliant use of highly innovative graphic design, but when working on this commission he adopted a more traditional presentation of the image befitting its traditional subject matter.

As war threatened later in that decade, it became clear that much of the built heritage was vulnerable to damage or destruction. `e Committee for the Employment of Artists in Wartime ran a scheme between 1940 and 1943 in which artists would depict those places seen as crucial to national identity. Some 97 artists contributed over 1500 works to the scheme, ‘Recording the changing face of Britain’ or, more simply, ‘Recording Britain’. It was inaugurated by Kenneth Clark, who deliberately resurrected the old topographical tradition, and promoted the use of the traditional technique of watercolour. Barbara Jones’ Pendennis Castle (1943) is a good example of the results (see page 109). `e castle, originally built by Henry viii, had been equipped with new guns for coastal defence and was for that reason vulnerable. Jones depicts the historic structure and only two details, the iron fence and the radio aerial, incorporate it in the modern world.

Although a few images of castles continued to be made after the war, as for example in John Piper’s work, the topographical tradition was efectively exhausted. `e visual interest in castles has migrated from the fine arts to cinema and television, with over 140 productions using them as sets over the last 80 years. In that context, of course, the castle’s genuine historical identity is superfluous. Alnwick Castle, for example, has been the setting for King Arthur, Mary Queen of Scots, `omas à Beckett, Ivanhoe, `e Sherif of Nottingham, Dracula, Blackadder and Harry Potter among others. Clearly, the allure of castles persists. While they may no longer feature in the works of many visual artists their popular standing remains high as places to visit and as sites for imaginative engagement.

1. In 1774 a collected set of their engravings was published in three volumes, entitled Buck’s Antiquities or Venerable Remains of Above 400 Castles, &c., in England and Wales, with near 100 Views of Cities

2. Samuel Buck, ‘Proposals for the publication of … twenty-four views of castles … in the counties of Lincoln and Nottingham’, 1 November 1726, copy in private collection; quoted in Ralph Hyde, ‘Buck, Samuel (1696–1779)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/3850, accessed 24 Nov 2016].

3 Views in South Wales (1775), Views in North Wales (1776), Views in Wales (1777) and Twelve Views of North and South Wales (1786).

4. William Gilpin, Observations on the River Wye, and several parts of South Wales, &c. relative chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the summer of the year 1770 (London: R. Blamire, 1782), p. 49

5. Gilpin, Observations on the River Wye, p. 51

6. Compare Gilpin’s comments on castle living quarters in Observations on the River Wye, p. 48 with Combe’s Tour of Dr Syntax in Search of the Picturesque (London: Ackermann [1812], ninth edition, 1819), p. 71. Gilpin: ‘on viewing the comparative size of halls and chapels in old castles, one can hardly, at first, avoid observing, that the founders of these ancient structures supposed, a much greater number of people would meet together to feast, than to pray.’ Combe: ‘I fear our fathers took more care/of festive hall than house of prayer./I find these Barons fierce and bold,/Who proudly liv’d in days of old,/To pray’r preferr’d a sumptuous treat,/Nor went to pray when they could eat.’

7. William Combe, Tour of Dr Syntax in Search of the Picturesque (London: Ackermann [1812], ninth edition, 1819), p. 70

8. Archibald Alison, Essays on the Nature and Principles of Taste, Edinburgh: J.J.G. and G. Robinson, 1790, pp. 226 –7

9. Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (London: R. and J. Dodsley, 1757), p. 13.

10 `e Ancient Monuments Protection Act was initially concerned only with prehistoric remains. Its scope was widened with further legislation in 1900, 1910 and 1913 that brought castles within its remit.

11 River Wye, etching and mezzotint by Turner and W. Annis, published 23 May 1812. For Steer’s use of the Liber Studiorum see D.S. MacColl, Life, work and setting of Philip Wilson Steer (London: Faber and Faber, 1945) p. 80

castles and british landscape art 17

c Astles cur Ated t he treatment of castles by the office of works and its successors

roy porter

T HE TWENTIETH CENTUR y WITNESSED A significant change in the way that many medieval castles in the United Kingdom were cared for and made available for the public to visit, enjoy and understand. For the first time, a large number of buildings and places of archaeological and historical interest were placed in the care of the state with the explicit intention of improving their care and making them available for public enjoyment. `is was a consequence of the state’s evolving interest in the preservation of buildings and places of archaeological and historical importance. Although this process began formally in 1882 with the passing of the first Ancient Monuments Act, it was the passing of the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act in 1913 and the subsequent creation of the Ancient Monuments Department in the o2ce of Works which resulted in the transformation of many castles from either recently redundant military sites or objects of antiquarian interest to curated objects made available for informed public enjoyment. During the course of the next century over 130 castles in England, Wales and Scotland would transfer into the care of the o2ce of Works and its successor bodies.2

Castles were transferred into the care of the o2ce of Works either directly from other government departments and private owners or via guardianship, a process designed to enable the transfer of a castle’s management to the o2ce of Works while its owner retained the freehold. `e practical consequences of transfer were the same in either case: the maintenance of the castle and its presentation to visitors became the responsibility of the o2ce of Works.

`e philosophy governing the o2ce of Works approach to the care of monuments was set out by its First Commissioner in 1912: … the principles upon which the Commissioners are proceeding are to avoid, as far as possible, anything which can be considered in the nature of restoration, to do nothing which could impair the archaeological interest of the Monuments and to confine themselves rigorously to such works as may be necessary to ensure their stability, to accentuate their interest, and to perpetuate their existence in the form in which they have come down to us.3

Most of the castles in the care of the o2ce of Works were ruined structures and therefore presented particular challenges and

issues related to conservation, maintenance and presentation. For Charles Reed Peers, Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments from 1910 until 1933 and the head of the Ancient Monuments Department during its formative years, ruined buildings were set apart from those still in use: ‘Buildings which are in use are still adding to their history; they are alive. Buildings which are in ruin are dead; their history is ended.

`ere is all the diference in the world in their treatment. When a building is a ruin, you must do your best to preserve all that is left of it by every means in your power.’ 3

Underlying this approach was a primary concern to stabilise and ensure the long-term preservation of historic fabric without restoring lost elements or adulterating the physical evidence presented to visitors. But there was also a desire to make a castle’s remains explicable to visitors, aided by basic on-site signage and guidebooks.5 `e outcome of this efort was masonry cleared of vegetation, sometimes incorporating (usually) well-disguised structural interventions designed to stabilise inherently problematic ruined material, all set within neatly manicured lawns which allowed the plan of a castle to be fully legible.

In undertaking this work, and notwithstanding its o2cial line on restoration, the o2ce of Works set about not only the conservation of a castle’s historic fabric but often also the alteration of its physical form and setting. A useful case study, which illustrates the treatment of castles by the Ancient Monuments Department of the o2ce of Works in its early years, is Portchester Castle. Here there was a typical approach which sought to secure the preservation of the castle through physical intervention but which also went on to restore lost elements of the castle’s form. By so doing, it revealed the practical application of the o2ce of Works philosophy.

Portchester Castle had enjoyed an unusually long history of occupation and use, and it therefore presented many phases of physical evidence. Located at the northern end of Portsmouth harbour, the castle’s origins lie at the end of the second century ad, when a Roman shore fort was established in c.290, probably by the renegade emperor Carausius. Square in plan, the fort had principal entrances in its east and west walls, and its defensive circuit featured twenty hollow D-shaped bastions regularly spaced along the curtain wall, including at its corner angles. `e fort was reoccupied as an Anglo-Saxon

18 capture the castle

1

burh, though little survives above ground from this period. Following the Norman conquest, an inner bailey was constructed inside the fort’s northwest corner, the remainder of the fort providing an extensive outer bailey for the medieval fortification. While the Roman defences were periodically repaired, and their gatehouses rebuilt, the focus of building activity during the Middle Ages was the inner bailey, which by the 1120 s contained a tower keep (subsequently heightened), a hall, and ranges of accommodation protected by stone defences. In the reign of Henry ii Portchester became a royal castle, and its location made it a favoured embarkation point for kings travelling to the continent. Its high-water moment was perhaps the reorganisation of the inner bailey’s south and west ranges as a diminutive palace in the 1390 s, but by the turn of the seventeeth century its active use as an occasional residence by the monarch had diminished and in 1632 it was sold to Sir William Uvedale and subsequently descended through his heirs, the `istlethwaite family. `e castle served intermittently as a prisoner of war camp from the mid-seventeeth century through to the end of the Napoleonic War. At its peak, in the first decade of the nineteenth century, it accommodated some 7,000 men. During the rest of the century the castle became popular as a tourist destination, a function it still enjoyed in the early twentieth century despite its deteriorating condition.

Portchester Castle was transferred into the guardianship of the o2ce of Works on 23 June 1926 but intense consideration of the physical state of the castle and how to address its condition had first occurred a year earlier, when a visit was made by the Director of Works, who concluded that ‘Certain portions of the building are in a very serious state, and some attempt ought to be made to prevent falls before the winter.’ 6

`e Roman walls were covered with extensive ivy growth but it was not anticipated that extensive works would be required here; instead ivy removal, re-bedding of loose stones and

‘to some extent underpinning faulty foundations’ was all that was anticipated.7 of more concern was the east flank of the castle, the foundations of which had sufered from inundation by the sea.8 But the greatest concern was expressed about the condition of the medieval inner bailey, with, for example, the northeast tower presenting both loss of masonry at low level and severe structural movement. A technical report on the castle’s condition, prepared in July 1925, concluded that ‘It is impossible to form any accurate estimate of the total cost of the preservation work required upon this Monument. Its extent is very considerable, and at the moment many costly items of structural repair are urgently required, so that for a period of 5 to 6 years about £2,000 should be put aside annually for dealing with the accumulated dilapidations of the past hundred years or so.’ 9

`e situation presented by Portchester Castle was exactly that designed to be remedied by the 1913 Act. A ruined monument of national importance, which was beyond the resources of its owner to maintain, would be transferred to the care of the state and be put into good order. If this was a decision taken primarily because of what today would be called the castle’s significance, future opportunities to ofset the cost of the works through admissions income were also recognised. Lionel Earle, Permanent Secretary of the o2ce of Works, commented to the First Commissioner that ‘if proper intelligence is shown … [the castle] ought to produce a certain amount of revenue.’ 10

A massive clearance and consolidation operation was undertaken in order to realise the first priority of removing vegetation and stabilising the castle’s fabric. `e castle’s Roman and medieval building material was treated with the utmost respect, with, for example, special attention paid to ensuring that the work did not adulterate the evidence of phasing in structures such as the water gate or the inner bailey’s north wall.11 But, where

capture the castle 19

Portchester Castle: keep and western curtain wall, September 1926, before conservation by the o2ce of Works began Historic England Archive: AL0862/012/02/PA

Portchester Castle: keep and western curtain wall, 2016 author’s photo

the structural condition of the castle justified it, a thoroughly robust level of intervention was involved. In the west wall of the keep, for example, concrete beams were introduced to stitch the building together, an intervention which remains visible in the first-floor mural passage. And not all fabric was equal: in contrast to the reverence paid to earlier material, the castle’s post-Medieval fabric was generally considered of relatively little value – at best an irrelevance and at worst a confusing imposition on the evidence presented by the earlier work. Again, the keep demonstrates this view. Before the works commenced it had been noted how the keep’s interior had been rendered ‘displeasing’ by the introduction of several post-Medieval floors, that none of the existing floors were at the correct (Medieval) level, that some of the principal window openings had been altered to accommodate the new floor levels and that the interior wall surfaces were masked with whitewash and disfigured with brick insertions. `ese ‘displeasing’ features would, for the most part, be removed during the works: all the floors (and the roof) were replaced at the appropriate medieval levels and window openings restored to their historical width and depth. But at least enough value was placed on the later changes to leave many of the post-Medieval floor joists in situ as isolated – if more than slightly incongruous –features providing evidence of the keep’s later use.

Beyond the standing ruins, the works also involved largescale changes to their landscape setting. Extensive excavation was carried out to restore the medieval ground surface level inside the inner bailey and to restore the in-filled ditches and moats around the castle. Work of this scale required a large, experienced work force and this was provided by Welsh miners and unemployed people.12 Although at first glance the attitude shown toward restoration of the landscape around the castle may appear gung-ho compared with the more cautious approach to standing fabric, the activity in both areas was in fact founded on the basis that it was desirable to remove later alteration – be it masonry or the earth filling-in of former ditches – to restore the primary form of the castle.

At its conclusion this efort, which had taken several years to complete, had radically altered the form of Portchester Castle: its walls, divested of ivy and newly consolidated, now stood within sharply profiled earth and water-filled defences for the first time in centuries. Quite apart from conserving the castle as found, the o2ce of Works had removed later fabric and archaeological deposits to reveal its medieval (albeit ruined) form and had recreated aspects of its defences.

`is approach to castles in State care, exemplified by the treatment of Portchester, did not occur in isolation. other types of medieval monument were receiving similar attention, most notably perhaps the great ruined abbeys of the north, such as Rievaulx and Byland. A unifying factor in the treatment of the monuments by the o2ce of Works and its successors for most of the twentieth century was the prioritisation of archaeological interest over other aspects of their character.

`e consequences of this approach can be seen at Deal Castle.13

Built in 1539 as part of Henry viii’s device for securing the coast in the face of threat from Europe following his repudiation of papal authority over the English church, Deal was one of three neighbouring fortifications built to protect the important but vulnerable anchorage known as the Downs in east Kent.14 Built to a centralised plan, with a series of radiating lunettes and circular bastions positioned around a central tower, Deal was an exercise in artillery fortification, with rounded parapets designed to deflect shot, and multiple embrasures for the deployment of ordnance large and small as well as the traditional longbow. In the eighteenth century the accommodation at the castle was upgraded, with panelling introduced to its first-floor rooms and a tall brick extension built on its seaward side to provide a fashionable residence for its captains. over the course of the next two hundred years further alterations were carried out on the Tudor fabric of the castle, such as the conversion of original openings to doorways and sash windows, and the further sub-division of the interiors.

20 capture the castle

Portchester Castle: inner bailey’s southeast tower and across outer bailey, 19 June 1930, before restoration of the moat had occurred Historic England Archive: AL0862/017/02/PA

Portchester Castle: inner bailey’s southeast tower and across outer bailey, 2016 author’s photo

In october 1940 Deal Castle sustained damage from enemy bombing, resulting in substantial damage to the captain’s house built within it. A candid note in an o2ce of Works file written in the week that the bombing occurred reveals the evident glee felt by o2ce staf at the serious damage meted out on the postTudor fabric: ‘Gloria in excelsis. `e Huns have done what we desired but daren’t do.’ 15 `e damaged fabric was shored up but never repaired. After the war, with the o2ce of Captain suspended, the decision was taken to demolish the damaged building rather than attempt to repair it. `is allowed the restoration of the Tudor form of the castle. But the work was not restricted to the removal of war-damaged material. `e whole interior of the castle was divested of most of the features associated with its use as a residence over the previous two centuries, post-Tudor doorways were converted back into embrasures and archaeological features encountered during the works left exposed.

`e result of the work at Deal was to provide visitors with an opportunity, for the first time in two centuries, to gain an immediate sense of the Tudor form of the castle but this was achieved at the cost of important aspects of the castle’s historical character. `e loss of the later interiors left surviving post-Tudor features stranded and rather incongruous, with decontextualized sash-windows now rubbing shoulders with restored Tudor embrasures. `is approach allowed visitors to see the scars sustained by the castle’s fabric as a result of changes through time but provided little sense of why this had occurred and how the castle had been used.

Bearing in mind Charles Reed Peers’ distinction between living and dead buildings quoted above, it might be said that by the completion of its restoration Deal Castle had passed from this world to the next. `is occurred at least in part because until relatively recently, function as well as period defined how a castle should be conserved. Castles were treated primarily as examples of military architecture, their defensive character highlighted, revealed and occasionally

restored, sometimes at the cost of their broader history. `is approach reflected a wider academic understanding of what castles actually were. Broadly speaking, castles were conceived as primarily defensive structures, and their designers were understood to have prioritised defensibility over domestic planning or other considerations. In addition, it was argued that castle design was fundamentally the product of the exchange between developments in siege and defensive technolon `is meant that apparently defensive features in any particular castle could be used to place it within a broader linear narrative which set out how castles generally evolved from basic strongholds to sophisticated fortifications before ultimately succumbing to artillery technolon 16

More recent scholarship has explored other aspects of the historical significance of castles, such as their social history, their wider landscape setting and changing cultural meaning, and these are now considered worthy of equal consideration with the details of defensive planning.17 one consequence of this altered understanding of what castles were designed to do, how they were used and how they were regarded, is that their presentation to visitors is now likely to reflect these broader themes. So, for example, in its interpretation of the Great Tower at Dover Castle, English Heritage concentrates on the use of the building as part of a palatial residence by the Angevin kings, and at Portchester Castle a forthcoming presentation scheme will concentrate on the post-medieval use of the castle to house prisoners of war.

So too does an enhanced appreciation of the sweep of history embodied in the fabric and archaeolon of castles inform how they are conserved and presented. It is unlikely that current conservation practice would allow wholesale removal of postmedieval fabric in the manner undertaken in the past. And a project such as the restoration of the Elizabethan garden at Kenilworth Castle undertaken in 2009 seems some distance away from the spare and sanitised approach adopted by the o2ce of Works a century ago. Even more so does Wigmore

castles curated 21

Deal Castle: rebuilding the eastern lunettes, 5 May 1953 Historic England Archive: AL0631/037/01/PA

Deal Castle: eastern lunettes, 2016 author’s photo

Castle, which has been carefully conserved by English Heritage so as to retain the wild and overgrown character it possessed when it was taken into its care in 1996. In the words of English Heritage’s then chairman, the castle was consolidated in such a way that ‘it would remain a romantic ruin forever.’ 18

But many of the verities set forth in the earliest years of the o2ce of Works still hold today. Curation of castles by English Heritage still has as its primary purpose the securing of the long-term future of these monuments. Careful attention is paid to ensuring that any interventions respect character and evidential value. And if our understanding of the significance of the castles in our care is broader than a century ago, we emulate our predecessors in seeking to enable visitors to enjoy and understand these exceptional places.

1. I am very grateful to Jeremy Ashbee and Samantha Stones for reading a draft of this essay. `eir comments helped to improve it and any errors or infelicities remain wholly my responsibility.

2 `e o2ce of Works and Public Buildings could trace its origins to the reign of Richard ii. Its responsibilities descended to the following bodies: Ministry of Works and Buildings (1940), Ministry of Works (1943), Ministry of Public Buildings and Works (1962), Department of the Environment (1971). `e National Heritage Act of 1983 established the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England, commonly known as English Heritage, as the successor body in England; since 2015 the English Heritage Trust, an independent charity, has been responsible for the management and conservation of the English part of the historic estate discussed in this paper. In Scotland and Wales, the properties continue to be cared for by executive agencies of the government, Historic Environment Scotland and Cadw respectively.

3. ‘Ancient monuments and historic buildings: Report of the Inspector of Ancient Monuments for the year ending 31 March 1912. Presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of His Majesty’, London: HMSo; `e National Archives [tna] work 14 /2470. Quoted in Simon `urley, Men From the Ministry (New Haven and London, 2013), p. 133

4. W.A. Forsyth, ‘`e Repair of Ancient Buildings’, `e Architectural Journal, vol. 21, third series (1914), pp. 109 –137. Peers’ comment is found on p. 135.

5 `urley, op cit, p. 68

6 tna work 14 /414, 12 June 1925

7 tna work 14 /414, Technical Report July 1925, 2

8 tna work 14 /414, Technical Report July 1925, 3

9 tna work 14 /414, Technical Report July 1925, 10

10 tna work 14 /414, 4 August 1925

11. tna work 14 /414, Technical Report July 1925, 4 and 6.

12. John Goodall, Portchester Castle (London, 2008), pp. 39 –40 `at the excavation of the ditches could provide work for unemployed people had been anticipated in the technical report produced before the castle came into guardianship. Having observed the section of a grave being dug in the churchyard, the report’s author recommended general excavation of the castle’s interior to a depth of 3 feet 8 inches, which would ‘give employment to some 25 to 30 unemployed during the winter months for several years, provided an experienced Antiquarian could be found to supervise the works and that funds were available.’ tna work 14 /414, Technical Report, July 1925, pp. 10 –11

13. Deal, along with the other fortifications of Henry viii’s device, has long enjoyed a liminal position in castle historiography, with its function as a garrisoned fort being quite diferent to a medieval defensible lordly residence. However, its inclusion here is justified by its identification by contemporaries as a castle: notwithstanding the conceptual and typological boundaries imposed by historians, people in 1540 thought that the fortification at Deal was a castle and called it such.

14 `e other castles were Walmer and Sandown. All three were originally connected by a ditch with earthen bulwarks.

15 tna work 14 /1943, 8 october 1940

16. See, for example, R Allen Brown, English Castles, London 1976 for a celebrated exposition of this view.

17. Examples of this approach are Matthew Johnson, Behind the Castle Gate (London, 2002), Charles Coulson, Castles in Medieval Society (oxford, 2003), Abigail Wheatley, `e Idea of the Castle (york, 2004), Robert Liddiard, Castles in Context (Macclesfield, 2005), and John Goodall, `e English Castle (London and yale, 2011)

18. Taken from a speech by Sir Jocelyn Stevens made at the opening of the castle in 1999 `e speech is reproduced in `e Castle Studies Group Journal, no. 30 (2016 –17), p. 92

22 capture the castle

the c Astle In medIevA l engl A nd Aesthetics, symbolism and status

Andy k ing

I T IS C HRISTMAS Ev E , AND S IR G AWAIN, THE protagonist of the late-fourteenth century poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, is struggling across the desolate wilderness of the Wirral peninsula, pursuing a knightly quest. He prays to the virgin Mary to grant him shelter where he may celebrate the feast of Christmas. Looking up, he sees:

[ A] castle most comely that ever a king possessed, Placed amid a pleasance, with a park all about it.

Approaching it, he observes that:

`

e wall waded in the water wondrous deeply and up again to a huge height in the air it mounted, all of hard hewn stone to the high cornice fortified under the battlement in the best fashion and topped with fair turrets set by turns about

Many chalk-white chimneys he chanced to espy upon the roofs of towers all radiant white; so many a painted pinnacle was peppered about, among the crenelles of the castle clustered so thickly that all pared out of paper it appeared to have been.1

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight – one of the great masterpieces of English literature – tells of a series of games designed to put the courtesy and chivalry of Sir Gawain to the ultimate test. Set in the ‘historical’ world of King Arthur, the castle portrayed in the poem is nevertheless built to the very heights of contemporary fashion.2 And this passage encapsulates how castles were perceived in the Middle Ages in terms of aesthetics and status: the Green Knight’s castle is presented not as a forbidding, invincible stronghold; rather, it is a work of architectural refinement so graceful that it appears to be made of paper: an island of civilized gentility in the wilderness. Above all, it serves as a symbol, lovingly depicted, of the courtly status of its lord.

`e castle might perhaps be defined as a lordly residence provided with the architectural accoutrements of defence.3 While this may seem straightforward enough, the question of what constituted a castle has in fact been a matter of considerable controversy. For most of the twentieth century, historians of castles took the view that the primary function of a castle was defensive; therefore, buildings which lacked

‘serious’ fortifications were not ‘proper’ castles.4 And this led to long-running, and often rather acrimonious, disputes over whether particular buildings should be considered as ‘real’ castles or not; perhaps the most heated of these debates has concerned Bodiam, Sussex (see page 101), which has been described as an ‘old soldier’s dream house’.5 Contemporaries, however, took a much more catholic view of what constituted a castle; thus while historians have designated buildings such as Aydon, Northumberland, with terms such as ‘fortified manor houses’, on the grounds that they are too slightly fortified to count, they are generally referred to in medieval records straightforwardly as ‘castles’. Nevertheless, while definition was of no great consequence to those who inhabited them, designation was a matter of great importance. Just how important is revealed by a royal charter obtained by the Northumbrian squire William Heron in 1340; together with other markers of lordship such as a market and fairs, the king granted that ‘of special grace, and for good service rendered … [Heron] may hold his manor house of Ford, county Northumberland, which is enclosed with a high em-battled wall, by the name of a castle … for the defence of those parts against the attacks of the Scots, the king’s enemies’.6 In other words, Heron had gone to the trouble of obtaining royal confirmation that his fortified dwelling should be called a castle. Clearly, this did not make it a stronger fortress; rather, Heron was concerned about how it should be perceived.7

`is concern is demonstrated by royal writs (dubbed by historians ‘licences to crenellate’), granting permission for lords to fortify their residences. Some such 550 licences are recorded as being issued between 1200 (when the Crown started to keep records of its writs) and 1657. But licensing was not proscriptive; many castle builders never bothered to obtain one, yet very few faced any repercussions for their omission. Indeed, only very rarely, at times of prolonged political turmoil, did the Crown actively attempt to control the building of castles – mainly in the aftermath of the civil wars of the reigns of King Stephen (‘the Anarchy’, c.1138 –c.1153) and King John (‘the Baron’s War’, 1215 –17). Rather, it appears that demand for these licences originated with the builders of the castles themselves; and they served as what amounted to a royal foundation charter, bestowing both the cachet of royal recognition of a residence as a castle, and a declaration of the status of its lord.8 `e original licence to crenellate for

the castle in medieval england 23

Chillingham Castle, Northumberland, is still displayed there for the edification of tourists; and it probably still fulfils much the same function as it did in 1344, when it was first issued.9

Clearly then, the medieval castle was far more than just a fortress; rather, it was a structure whose symbolic and aesthetic qualities were at least as important as its military and defensive function. And castles remained a vital marker of social standing throughout the Middle Ages. Medieval scholastic tradition held that society was divided into three estates, ordained by God: the oratores, those who pray; the bellatores, those who fight; and the laboratores, those who labour (a tripartite division embodied in the idealised pilgrims, the Priest, the Knight and the Plowman of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales). `e nobility were the bellatores; it is thus hardly surprising that their dwellings should have taken on a martial aspect. But more than this, castles were an embodiment of noble, knightly identity.

Castles were introduced to Britain by the Normans, the most common early form being a motte (or mound) with a tower at its summit, surrounded by a ditch, and with a bailey enclosed by a palisade and ditch. Such castles could be constructed quickly, and had an obvious defensive purpose. In the aftermath of the Conquest of 1066, such castles might, in the first instance, be intended to overawe the newly-subjected English tenants of a newly created lordship. And in this respect, a vital part of its function was symbolic: a tall tower on top of a motte served as a very visible sign of the lordship of its owner – and the fact that he could command the considerable resources and labour necessary to construct it (particularly as such labour was usually forced, so that tenants were obliged to erect these

symbols of their own subjugation). Although, conditioned as we are by surviving masonry ruins, we now think of the castle as a construct of stone, most early castles were initially constructed with wood; and many were never rebuilt in stone. Unfortunately, only the earthworks of these wooden castles now survive, but archaeological digs have revealed that they could be very elaborate and impressive buildings.

However, just as the ecclesiastical dominion of the Church was marked out in cathedrals and abbeys of stone, so secular lords increasingly marked out their earthly dominion with castles of stone. Huge stone towers such as the Tower of London, built by William the Conqueror, Chepstow, constructed during William’s reign, or Dover, built by Henry ii in the 1180 s, were intended to dominate their surroundings. `is is reflected in the very term donjon by which these towers were commonly referred to by contemporaries; it is derived from Latin dominus, meaning ‘lord’ (the English term ‘dungeon’ in turn derives from donjon, because of their frequent use as prisons).10

Great towers fell somewhat out of fashion after the end of the twelfth century, as increasingly elaborate and dramatic gatehouses came into vogue. But they continued to be built until the end of the Middle Ages. In the 1380 s, Henry Percy, newly ennobled as earl of Northumberland, marked his advance by building a magnificent palatial new great tower at his castle at Warkworth, Northumberland. And as late as the 1440 s, Ralph, Lord Cromwell, the former treasurer of the realm, built a spectacular new great tower at his ancestral castle at Tattershall, Lincolnshire, referred to in his building

24 capture the castle

Warkworth Castle: the great tower displaying the Percy lion, the heraldic sign of its builder author’s photo

accounts as ‘le Dongeon’,11 though it was constructed in fashionable brick, rather than stone.

`e fine demeanour presented by Tattershall’s bright red brickwork highlights the importance of aesthetic efect in castle design. Like the Green Knight’s castle, with its ‘towers all radiant white’, many castles were painted with whitewash –notably the Tower of London, and White Castle (Monmouthshire), rebuilt in stone by Henry ii. Gatehouses often carried colourful displays of heraldry, marking out the lord’s lineage and standing in noble society; at Warkworth, carvings of the Percy lion prominently adorned both the outside of the great tower built by the first earl of Northumberland, in the 1380 s (see previous page), and the porch of the hall (rebuilt by the fourth earl, in the 1480 s). Castles might also be decorated with statuary, such as the eagles that topped the ‘Eagle Tower’ at Caernarfon (see page 104); or the stone guards that adorned the battlements of Marten’s tower at Chepstow, and a number of northern castles such as Alnwick. `e great tower at Norwich castle, built by William ii at the end of the eleventh century, is decorated with elaborate arcading, mirroring the detail of the city’s cathedral, which was being built at the same time. Similarly, the forebuilding of the great tower at Castle Rising in the same county, built in around 1140, is decorated with blind arcading (above, left), a feature frequently found in contemporary churches. Halls became increasingly splendid, often provided with impressive traceried windows, sometimes decorated with stained glass; particularly sumptuous was the palatial hall built by John of Gaunt at Kenilworth in the 1370 s (above, right), fitting for his status as the son of Edward iii, Duke of Lancaster and titular king of Castile.

Indeed, castle halls would have been far more colourful than their bare stone ruins now suggest; the wall-painting at Belsay, Northumberland, built by Sir John de Middleton at the end of the fourteenth century, is a very rare survival of what would once have commonplace (below).

But even before a visitor reached the castle gate, the authority, gentility and good taste of its lord would have been forcibly impressed upon them. Castles were generally set in a carefullycrafted landscape, designed specifically to this end, an intention skilfully evoked by the poet’s description of Sir Gawain’s first impression of the Green Knight’s castle.12 Parks, enclosed with walls or palisades, provided a picturesque background and a venue for hunting – that most noble of pastimes (they could

the castle in medieval england 25

Castle Rising: decorative blind arcading on the forebuilding of the great tower author’s photo

Kenilworth: traceried window in John of Gaunt’s hall author’s photo

Belsay: fragments of fifteenth-century wall painting. Such decoration would have been common in castle halls and chambers author’s photo

also provide an economic resource; in the fifteenth century, venison from the deer park at Barnard Castle, Durham, seems to have been sold as far afield as London).13 Water features provided a suitably dramatic setting, and reflections on the water’s surface enhanced and heightened the visual impact of a castle. ornamental gardens served to enhance the aesthetic appeal of the castle; James i, King of Scots, imprisoned in England after being captured in 1406, praised the ‘garden fair’ and the ‘arbour green’ at Windsor castle.14 A church or a monastery associated with a castle emphasized both the piety of the lord, and the power and wealth that enabled such a display of piety. So Ralph Cromwell demolished the parish church at Tattershall, which lay beside his castle, and refounded it as an impressive new collegiate church, to complement his new great tower. Conversely, castles were sometimes fitted into a specific landscape. It is surely no coincidence that Cromwell, a prolific builder, chose to construct his tower at Tattershall in lowland Lincolnshire – there was no better place for him to make his mark, for it can be seen from Lincoln cathedral, some twenty miles away.

one of the grandest of these designed castle landscapes was Kenilworth (Warwickshire), first constructed in the 1120 s, by Geofrey de Clinton, Henry i’s chamberlain, and a man on the make.15 It was furnished with a monumental great tower, and surrounded by carefully maintained artificial lakes, transforming it into a virtual island. Sited next to the castle were an Augustinian Priory and the borough of Kenilworth, both also founded by Clinton. `e castle and lake were surrounded by a huge park; and a large pleasance, or pleasure garden, was constructed by Henry v on the banks of the lake about half a mile from the castle. `e contemporary chronicler `omas Elmham made an allegory of Henry’s work:

`ere was a fox-ridden place overgrown with briars and thorns. He [the king] removes these and cleanses the site so that wild creatures are driven o f. Where it had been nasty now becomes peaceful marshland; the coarse ground is sweetened with running water and the site made nice. So the king considers how to overcome the di 2 culties confronting his own Kingdom. He remembers the foxy tricks of the French both in deed and in writing and is mortified by the recollection.16

Kenilworth was undoubtedly a strongly defensible fortification: it withstood a six-month siege by Henry iii in 1266. But it was also designed to impress.

Such considerations remained true even where the needs of defence were urgent. `omas, Earl of Lancaster, the cousin of Edward ii, started work on his formidable castle at Dunstanburgh, Northumberland, in 1313 –14, just a year or two after he had led a rebellion against Edward and put his hated favourite, Piers Gaveston, to death. `omas intended Dunstanburgh as a bolt-hole against Edward’s wrath. But it also reflected `omas’ pretensions, being furnished with a series of meres to highlight its dramatic setting, for the castle itself was spectacularly sited on top of a steep promontory by the sea; and the approach was carefully laid out so that visitors were presented with the most impressive views of the place. Even the name Dunstanburgh seems to have been specially coined from new, to lend `omas’ castle a spurious air of antiquity to match the venerable royal castle of Bamburgh, a few miles up the coast.17

An imagined antiquity became attached to many castles. `ere was a widespread late-medieval tradition that the Tower of London had been built by Julius Caesar. Similarly, in his Morte D’Arthur, Sir `omas Malory comments in passing of Lancelot’s castle Joyous Garde, that ‘some men say it was Alnwick, and some men say it was Bamburgh’.18 Some lords deliberately fostered the development of historical associations; when, in the fourteenth century, the Beauchamp earls of Warwick built a new tower at their castle at Warwick, they called it ‘Guy’s Tower’, after Guy of Warwick, the pseudo-historical Saxon hero of a chivalric romance.19 Such associations were intended to anchor a lord and his lineage in the historical traditions of their ‘country’, emphasizing the longstanding heritage to which they were the heirs. Castles provided a potent and enduring symbol of that heritage.

However, it was perhaps Edward i who went to the greatest lengths to evoke historical precedent. After conquering Wales in 1282–3, he began work on three gargantuan state-of-the-art castles at Harlech, Conwy and Caernarfon. All were designed to be invincible fortresses, intended to serve as fortifications to protect against Welsh rebellion. But Caernarfon, in particular, was also designed with deliberate symbolic reference to the past. `e castle was built with polygonal towers (instead of the more fashionable round towers employed at Conwy and Harlech), and the walls had bands of coloured stone, in imitation of Roman building styles. `is linked the castle with the ruins of the neighbouring Roman fort of Segontium, which was associated with tales of King Arthur, and of the Roman Emperor Constantine.20 `us Edward’s castle marked out his claim to be the rightful heir to the authority of Arthur and the Romans.

`e author of a contemporary English chronicle, `e Flowers of History, commented, ‘by God’s providence, the glory of the Welsh was transferred to the English’.21 Caernarfon castle was a powerful symbol of this transfer, set in stone. And if anyone missed the point, they could hardly miss the castle; like Conwy and Harlech, Caernarfon was one of the largest and most forbiddingly impressive buildings in Wales, dwarfing even the Welsh cathedrals – and especially (and pointedly) the castles of the Welsh princes.