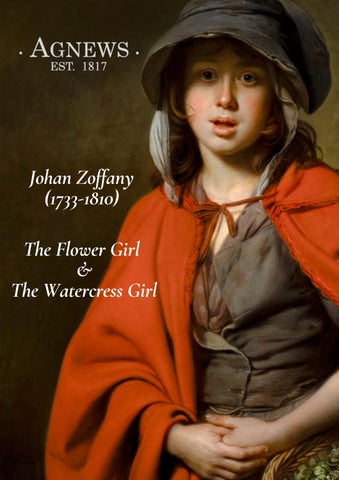

(Frankfurt-am-Main 1733-1810 Strand-on-the-Green)

The Flower Girl and The Watercress Girl Oil on canvas

35 7/8 x 27 7/8 in. (91.2 x 70.8 cm.)

35 1/16 x 28 in. (89 x 71.1 cm.)

Purchased from the artist by Jacob Wilkinson (c 1722-1799); his son, Thomas Wilkinson (1762 - 1837); his daughter, Jane Anne Brymer (1804-1870); William Ernest Brymer (1840-1909) of Ilsington House, Puddletown, Dorset; his son, Wilfred John Brymer (1883-1957); his sister, Constance Mary Brymer (1885-1963); her nephew, John Hanway Parr Brymer (1913-2005); by descent; sold Bonham’s, London, 4 December 2024, lot 27, as a pair.

Exhibited

The Watercress Girl (as ‘Girl with water cresses’), London, Royal Academy, 1780 (204)

Literature

Lady Victoria Manners and Dr G.C. Williamson, John Zoffany, R A His Life and Works. 1735-1810, London: John Lane, 1920, pp 76-77, 229, 283[i]

Mary Webster, Johan Zoffany, exhibition catalogue, National Portrait Gallery, London, 1976, pp.70-1, under cat. nos. 89 and 90

Martin Postle, Angels & Urchins, The Fancy Picture in 18th-Century British Art, exhibition catalogue, The Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood, and Nottingham University Art Gallery, 1998, pp.17-18, fig. 36 (‘The Flower Girl’); pp.79-80 under cat. no. 57 (‘The Watercress Girl’)

Penelope Treadwell, Johan Zoffany, Artist and adventurer, London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2006, pp.391-2, ill, pls.1 and 2; 2nd edition, 2009, pp.313-16, ill. pp.312, 314 Mary Webster, Johan Zoffany 1733-1810, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011, pp 399-401, figs 298, 299

Martin Postle, ed, Johan Zoffany RA Society Observed, exhibition catalogue, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Royal Academy of Arts, London, in association with Yale University Press, 2011, p 34, ill , fig 28, p 228, under cat no 52

The Flower Girl and The Watercress Girl are unique in Zoffany’s oeuvre in terms of their chosen genre They are also among the most virtuosic of his artistic accomplishments, both visually and technically Painted after his return from Italy to England in 1779, they represent Zoffany at the height of his powers, presenting at close quarters poignant images of two teenage girls, plying their precarious trade on the streets of London The images form part of a tradition of what came to be known as the ‘fancy picture’, a hybrid art-form which gained popularity in Britain during the eighteenth-century, although its roots were embedded in European traditions involving the depiction in the form of vignettes of a range of colourful characters, from ragged urchins, to alluring young street vendors, courtesans, musicians, gypsies, and even wizened old beggars To an artist such as Zoffany, alive to the warp and weft of everyday life, visceral subject matter of this nature was irresistible. In the present works, he pays meticulous attention to every detail, his fascination extending to the very fabric and the contents of the wicker baskets, bunches of glistening green watercress in one, and brightly coloured hedgerow blooms cascading over the rim of the other He scrutinizes his subjects’ appearance, from the makeshift fastenings of the pins on the bodice of the Watercress Girl and her grubby fingernails, to the delicate stem of the narcissus poised delicately between the finger and thumb of the ruddy-faced, rheumy-eyed, Flower Girl, and her thinly veiled breasts

Particularly arresting is the penetrating gaze of the girls, set against a plain background on the scale of life, ensuring that the relationship between subject and object involves direct, even unnerving, eye-to-eye contact Open-mouthed, their speaking likenesses communicate a world of sound as well as vision As to the girls themselves, they project an aura of combined innocence and experience They are neither children nor women, let alone young ladies Rather, they are ageless and nameless ‘girls’, their faces and features moulded by harsh personal circumstances in a world of unremitting labour

The popularity of images depicting street vendors, such as Zoffany’s Flower Girl and Watercress Girl, was linked inextricably to the growth of a commercial consumer culture in eighteenth-century Britain, the so-called ‘fancy picture’ featuring, in the case of females, a range of street vendors, selling anything from flowers, fruit and vegetables to eels, oysters, ballads, and even their own bodies The visual roots of the fancy picture hark back to graphic traditions which evolved in the Middle Ages More immediately, the sound and well as the sight of the metropolitan street vendor, was epitomised by an influential publication of 1688 by the Dutch-born painter and engraver, Marcellus Laroon, entitled Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life Featuring over seventy engravings of a diverse range of characters, including not only trades people, such as milkmaids and chimney sweeps, but street performers, including assorted musicians and even ‘Posture Masters’ Images were accompanied by their relevant street cries, from ‘Buy a Rabbet a Rabbet’, and ‘Ripe Strawberryes’, to ‘New River Water’, and ‘Ripe Speragas’ (fig 1)

1.Marcellus Laroon, Ripe Speragas, 1688, etching and engraving, 24 7 x 15 8 cm (10¾ x 6¼ in) The Trustees of the British Museum, Museum number L,85 16

2 Richard Houston after Philip Mercier, The Fair Oysterinda c 1736-75, mezzotint engraving, 35 5 x 25 3 cm (14 x 10 in) The Trustees of the British Museum, Museum number 1872,0713 11

3.Bartolozzi after William Hogarth, Shrimps!, 1782, sanguine stipple engraving, 27 x 20 4 cm (10½ x 8 in) The Trustees of the British Museum, Museum number Cc,1 86

4 Charles Hardy after Joshua Reynolds, The Boy with Cabbage Nets, 1803, mezzotint engraving, 35 x 25 2 cm (13¾ x 10 in) Trustees of the British Museum, Museum number 1840,0808 117

By the early eighteenth century countless cheap prints celebrated not only types but specific individuals, such as ‘Betty Monro, fruit-girl at the Exchange in the Strand’, ‘Dunstan, the crier of wigs’, or ‘Old Coe’ the oyster seller Inevitably the most popular prints in the marketplace were those featuring nubile young women, whose physical attractions were emphasised to fuel male fantasies focused upon them as commodities in their own right Even the word ‘commodity’, was a coded reference to the vagina, as in the bawdy song penned by the seventeenth-century army officer and playwright, William Wycherley, who dwells upon the ‘Juicy, Salt Commodity’ proffered by the female oyster seller.[2] Wycherley’s salacious verses are echoed in the inscription on a later print after Philippe Mercier, entitled, The Fair Oysterinda: "The Oysters good! - The Nymph so fair! Who would not wish to taste her Ware? No need has she to Cry 'em Since all who see her Face must buy 'em'" (fig 2) By this time, the propensity of female street vendors to dispense sexual favours as well as wares was promoted via myriad obscene songs, ballads, and pamphlets Among the most celebrated eighteenth-century images of a female street vendor is Hogarth’s The Shrimp Girl (National Gallery, London), a lively unfinished oil sketch of a bright-eyed young woman balancing a tray of shrimps upon her head. In 1782, the image was reproduced in the form of a stipple engraving by the printmaker, Francesco Bartolozzi, with the title, ‘Shrimps!’ (fig 3) In addition to the title, Bartolozzi modified Hogarth’s image via the insertion into the composition of an exposed nipple, to produce a verbal and visual double-entendre As Edward Ward opined as early as 1709, in The London Spy, even ‘respectable’ women traders in London’s New Exchange, via the signals presented through their dress and deportment, tempt passers-by, ‘begging of Custom, with such amorous Looks, and after to Affable a manner, that I could not but fancy they had as much mind to dispose of themselves, as the Commodities they deal in’[3]

Beyond the realm of projected male fantasies centred upon female street vendors, the lives of the hordes of anonymous individuals who peddled consumer goods in the metropolis involved long hours and back-breaking labour for little financial reward Conspicuous in this labour market were children, who often carried quite literally the same burden as adults In 1775, Sir Joshua Reynolds exhibited at the Royal Academy A Beggar boy and his Sister (The Faringdon Bequest, Buscot Park), acquired from him by the Duke of Dorset The print made from it was entitled ‘The Boy with Cabbage Nets’ (fig 4), a specific reference to the trade pursued by the child in question, who Reynolds referred to in his sitter books as the ‘Net Boy’. Unusually, we have a first-hand account of the boy, given by one of Reynolds’s friends, the Reverend William, who encountered him in Reynolds’s studio, ‘He was ’ , noted Mason, ‘ an orphan of the poorest parents, and left with three or four other brothers and sisters, whom he taught, as they were able, to make cabbage nets; and with these he went about him, offering them for sale, by which he provided both for their maintenance and his own ’.[4] The story is a familiar one, and certainly, parallels can be found between the real life experience of the young cabbage net vendor, and lives of working girls, such those featured in Zoffany’s Flower Girl and Watercress Girl

Watercress was in eighteenth-century England a popular and inexpensive foodstuff, relished for its peppery flavour Like cabbage, it had long been a staple of working-people’s diet, both crops having been introduced by the Romans. It is not surprising therefore that watercress sellers featured frequently in popular prints, such as ‘Water Cresses, come buy my Water Cresses’, one of a series of ‘Cries of London’, published by Thomas Rowlandson in 1799, where a young female street vendor and her child proffer their wares to a leery-eyed old man as he knocks upon the door of brothel in London’s Portland Street (fig 5)

5 Henri Merke after Thomas Rowlandson, ‘Water Cresses, come buy my Water Cresses’, Cries of London, No. 5, 1799, aquatint etching, 32 8 x 27 3 cm (13 x 10¾ in)

London Museum, Object ID: 60 75/8

6.John Zoffany, David Garrick and Mary Bradshaw in David Garrick’s ‘The Farmer’s Return’, c 1762, oil on canvas, 101 6 x 127 cm (40 x 50 in) Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Henry Mayhew, a journalist, who investigated the lives of London labourers and the poor several generations later, in the mid-nineteenth century, characterised the trade in the ‘ greenstuff’, including watercress, as a form of commerce pursued by ‘the very poorest of the poor; such as young children, who have been deserted by their parents, and whose strength is not equal to any great labour, or by old men and women, crippled by disease or accident’ [5] In the course of his investigations, Mayhew interviewed a young Watercress Girl, who ‘although only eight years of age, had entirely lost all childish ways, and was, indeed, in thoughts and manners, a woman ’ As she told him, ‘I used to go down to market along with another girl, as must be about fourteen, ‘ cos she does her hair back up When we ’ ve bought a lot, we sits down on a door-step, and ties up the bunches We never goes home to breakfast till we ’ ve sold out’.[6] Regarding London’s flowergirls, Mayhew found it difficult to relate them specifically to their trade, not least because ‘ a poor costermonger will on a fine summer ’ s day send out his children to sell flowers, while on other days they may be selling water-cresses or, perhaps, onions’ According to Mayhew, there were two classes of flower-girls, those, smaller in number, who ‘avail themselves of the sale of flower in the street for immoral purposes ’ , and those who ‘wholly or partially, depend upon the sale of flowers for their own support or as an assistance to their parents’ [7] Of two orphan flower-girls he encountered, Mayhew noted, ‘the elder was fifteen and the younger eleven Both were clad in old, but not torn, dark print frocks, hanging so closely, and yet so loosely, about them as the show the deficiency of underclothing; they wore old broken black chip bonnets’ [8] Although the description was made over half a century after Zoffany’s paintings, little had changed during the intervening period

The appeal of subject matter taken from street life may have related to Zoffany’s own peripatetic experiences beyond the trammels of polite society, where he freely indulged his interests in High Art and low life Born in the picturesque town of Heppenheim, near Frankfurt, in March 1733, the son of court cabinet maker, he was baptised Johannes Josephus Zauffaly in the cathedral of Frankfurt. His family, who had moved to Prague and then to Frankfurt, came from Pilsen, Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic As a young man, aged seventeen, Zoffany had walked from Augsburg to Rome, spending much of the 1750s honing his skills in the artistic hotbed of Rome, under the tutelage of Anton Raphael Mengs. Returning to Germany, bored by the claustrophobic life as a painter in a small south German court, in 1760 he travelled, newly married, to England, without any promise of employment. There, while working as a scene painter, he was introduced to the actor, David Garrick, upon which Zoffany built a successful career as a painter of stage actors and theatrical performances (fig 6) Effectively now a single man, following the swift departure of his wife for Germany, Zoffany forged a new artistic and personal identity, securing his fortunes through the cultivation of fellow Germans who prospered in the environs of the court of George III and Queen Charlotte, where he himself found lucrative patronage (fig 7) And it was through the auspices of the Queen that he travelled to Italy in 1772 with a prestigious commission to paint the octagonal exhibition hall, the so-called ‘Tribuna’, in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, which housed one of the finest art collections in Europe.

7 Johan Zoffany, Queen Charlotte with her two Eldest Sons, 1764-65, oil on canvas, 112 4 x 129 2 cm (44 ¼ x 50 7/8 in) The Royal Collection, His Majesty King Charles III

8 Johan Zoffany, A Porter with a Hare, 1768-69, oil on canvas, 76 2 x 63 cm (30 x 24 ¾ in) Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry

9.Johan Zoffany, Beggars on the Road to Stanmore, c 1769-70, oil on canvas, 91 5 x 76 cm (36 x 29 7/8 in). Private collection.

10 Johan Zoffany, John Cuff and his Assistant, 1772, oil on canvas, 89.5 x 69.2 cm (35 ¼ x 27 ¼ in). The Royal Collection, His Majesty King Charles III

Following his arrival in England, Zoffany developed an interest in subject matter relating to modern everyday life, notably in works such as A Porter with a Hare (fig.8), and Beggars on the Road to Stanmore (fig 9), which he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1771, the itinerant subjects forming a secularised evocation of the Holy Family In 1772, just prior to his departure for Italy, he had also painted a remarkable portrayal of John Cuff, a London-based scientific instrument maker, with his assistant (fig 10), a work that showcased his exceptional eye for detail and characterisation, as well as his intimate knowledge of the traditions of Dutch genre painting A few years later, while in Italy, he produced two fascinating genre paintings, A Florentine Fruit Stall (fig 11), and ‘La Scartocciata’, the Festival of the Maize Harvest (Gallerie Nazionale di Parma), which celebrated aspects of unbuttoned peasant life in town and country In the Fruit Stall, Zoffany deliberately introduced an element of sexual innuendo in the figure of the young female fruit vendor, who attracts the attention of by passers as she flutters her eyes while toying with the melons in her basket and the grape she holds up between her thumb and forefinger It was also in Italy that Zoffany scandalized polite society by his association with a teenage girl named Mary Thomas, who he had made pregnant, having previously stalked her to her parents’ ‘humble dwelling’.[9] And while his portrait of Mary (fig 12), made around the same time as The Flower Girl and The Watercress Girl, proclaims, through the prominence of the wedding ring on her left hand, her status as a married woman, the relationship, as many suspected, was bigamous, since his first wife was alive and well in Germany.

Although they married many years later, upon her eventual death, the rumours that circulated concerning his illicit relationship with Mary Thomas served to bolster the impression of Zoffany as a rake and a ladies’ man, an impression he made little effort to quell during his subsequent time in India, where he fathered several children, including a son, by his Indian mistress. Viewed in this context, Zoffany’s interest in young female street vendors takes an additional layer of ambiguity, their open mouths and direct gazes denoting not merely the cries they call out to potential customers in relation to their wares, but his awareness of their potential as objects of male desire, uncomfortable as that proposition is to modern eyes

The Watercress Girl was one of three pictures he exhibited at RA in 1780 at its inaugural exhibition at New Somerset House in purposebuilt built top lit galleries designed by Sir William Chambers [10] Although he was a member of the Royal Academy, Zoffany had not exhibited there since 1775, when he was based in Florence. As Horace Walpole noted, the exhibition of 1780 contained ‘excellent pictures by Gainsborough, Zoffani, Wright and others’, Zoffany’s Tribuna of the Uffizi (fig 13), which he had painted in Florence, being one of the main attractions, not least for the controversial manner in which the lewd antics of the assorted connoisseurs in the painting eclipsed the Old Masters and antique statuary on display Walpole, who labelled the protagonists in Zoffany’s Tribuna ‘ a flock of travelling boys’, admired The Watercress Girl, which was, he opined, ‘ very natural’. As another viewer observed, Zoffany ‘has been very fortunate in a choice of a most beautiful Girl for his subject and he has copied nature so exactly, that it is not easy to determine whether it is real life or a painting’.[11]

11 Johan Zoffany, A Florentine Fruit Stall, c 1777, oil on canvas, 57.8 x 49.2 cm (22 ¾ x 19 3/8 in). Tate, London

12 Johan Zoffany, Mary Thomas (Mrs Zoffany), c 1781, oil on canvas, 75 x 61 5 cm (29 ½ x 24 ¼ in). Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

13 Johan Zoffany, The Tribuna of the Uffizi, 1772-77, The Royal Collection, His Majesty, King Charles III.

While The Watercress Girl was a pendant or companion to The Flower Girl, it is uncertain whether they were painted at the same time, given that Zoffany exhibited only the present painting at the Royal Academy The Watercress Girl, which Zoffany painted presumably sometime between the spring of 1779 and the spring of 1780 was published as a mezzotint engraving in September 1780 by John Raphael Smith, a leading London printmaker, who must have approached Zoffany after the closing of the exhibition in early June (fig 14) A clue to the possible identity of the model for The Watercress Girl was provided via the pen and ink inscription, ‘Jane Wallis’, on the lower margin an impression of the print now in the British Museum, possibly added by Smith himself as a putative title [12] In the opinion of the Zoffany scholar, Mary Webster, she may have been a niece of Albany Wallis, a London lawyer, a close friend of David Garrick. Alternatively, she may have been the child actress, Tryphosa Jane Wallis, although her stage career did not take off until the later 1780s [13] Whoever she was, a model playing the role of a street vendor, or the real thing, it was not until January 1785, by which time Zoffany was in India, that a print after Zoffany’s Flower Girl was produced (fig 15), this time by John Young, who also made a second print of The Watercress Girl [14] In Young’s print, the pose of The Flower Girl has been reversed, with the basket now on the right arm [15] Significantly, the paired prints were the first engravings to be published by Young, who was then still apprenticed to the engraver, Valentine Green.

By this time, as the inscriptions on the prints stated, the paintings themselves belonged to Zoffany’s friend, Jacob Wilkinson, a wealthy merchant banker and Director of the East India Company, who had supported his petition to travel to India, and whose portrait Zoffany painted c 1782 (fig 16), just prior to his departure for India The Flower Girl, if it was not painted in 1779-80, must therefore have been completed by this time Regarding the engraving made from it, comparison may be made not only with Zoffany’s Watercress Girl, but with a similar print featuring a young female flower-seller, published in 1785 by John Dean, after John Hoppner (fig 17) In this instance, the model was the artist’s young wife, Phoebe, daughter of the wax modeller, Patience Wright, who also posed to Hoppner in the guise of a salad vendor [16]

14.Left: John Raphael Smith after Johan Zoffany, The Watercress Girl (‘Jane Wallis’), 1780, mezzotint engraving, 38.2 x 27.5 cm (15¼ x 10¾ in). Trustees of the British Museum, Museum number 1902,1011 5086

15 Right: John Young after Johan Zoffany, The Flower Girl, 1785, mezzotint engraving, 38 x 27.9 cm (15 x 11 in) Trustees of the British Museum, Museum number 2010,7081 3572

Zoffany returned to England from India in 1789 following a six-year sojourn, in which he witnessed extremes of wealth and poverty, excess and deprivation, far beyond anything he had encountered in his previous life in England and Europe He returned a wealthy man, albeit in poor health And while he continued to be a presence in the metropolis and in the environs of the Royal Academy, by the mid-1790s he operated from his rural retreat at Strand-on-theGreen, Chiswick From now on, he rarely strayed far from home, although in the summer of 1798 he went on an expedition to Norwood, south of London, to pay a visit to a colony of gypsies, his interest piqued not only by their vagabond associations, but the shared vocabulary of the Romany language and the natives of Bengal In Norwood, he was captivated by the appearance of gypsy girl, ‘ a young Egyptian from Norwood, whom he believed to involve in her proportions the beauties of Pharoah’s daughter’.[17] The gypsy girl, aside from her personal charms, was also, as Zoffany knew, a stock figure in fancy pictures, as for example in Joshua Reynolds’s Fortune-Teller (The Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood) Who Zoffany’s gypsy girl was, or what she looked like is unknown, since, although a sketch of ‘The Gypsies at Norwood’ featured in his posthumous studio sale of 1811, there is no surviving visual record Thankfully, after being hidden from view for nearly two hundred and fifty years, The Flower Girl and The Watercress Girl have re-emerged as among Zoffany’s most impressive characterisations of individuals, whose lives were otherwise lived in the shadows, paired fancy pictures which serve to highlight the complex cultural and sexual politics which underpin such images, and, through their mesmerising presence, Zoffany’s extraordinary virtuosity and unerring eye for detail

16 Johan Zoffany, Jacob Wilkinson, oil on canvas, c 1782-83, oil on canvas, 73 7 x 61 cm (29 x 24 in) Government Art Collection, Chequers Court

17 John Dean after John Hoppner, The Flower Girl, 1785, mezzotint engraving, 37 5 x 27 5 cm (14¾ x 10¾ in) Trustees of the British Museum, Museum number 2010,7081.

[1] The owner of the pictures was given incorrectly by Manners and Williamson as John Baring, 2nd Baron Revelstoke, who, it was claimed, had purchased them ‘about fourteen years ago ’ from Colnaghi They also stated, incorrectly, that a previous owner was Mr Moberley Bell, editor of The Times. The dimensions of the pictures were given as 49 x 40 inches, which is again incorrect The pictures referred to were possibly either copies of the present works or, more likely, paintings misidentified as them.

[2] William Wycherley, ‘To a Pretty Young Woman, who opening Oisters said, /She wou’d open for Her, and Me too; since ‘twas for her Pleasure A Song’, in Montague Summers, ed, The Complete Works of William Wycherley, 4 vols , London: Nonesuch Press, 1924, vol 3, pp 169-70

[3] Postle 1998, p.18.

[4] David Mannings and Martin Postle, Sir Joshua Reynolds A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings, 2 vols, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000, vol 1, p 510, no 2016

[5] Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor; Cyclopaedia of the Conditions and Earnings of those that will work, those that cannot work, and those that will not work, 4 vols, London: William Clowes and Sons, 1861, vol 1, p 145

[6] Mayhew 1861, vol 1, p.151.

[7] Mayhew 1861, vol 1, p 134

[8] Mayhew 1861, vol 1, p 135

[9] Postle 2011, p 261, Webster 2011, pp 274-76

Mary Thomas’s age at the time of her death in 1832, was given as seventy-seven, so she was therefore born c 1755

[10] The other work exhibited by Zoffany was a ‘Portrait of a Gentleman’, who Walpole identified as john Burke, the Recorder of Carshalton, and which commended in the London Courant as ‘ an excellent portrait and a very striking likeness’ Webster 2011, p 399

[11] A Candid Review of the Exhibition (being the twelfth) of the Royal Academy London, 1780.

[12] British Museum, Museum number 1902,1011 5086

[13] See Webster 2011, p 400; Postle 2011, p 228

[14] ‘The Water Cress Girl’, 1785, mezzotint engraving, British Museum, Museum number 1878,0511 1015

[15] In 1796, the glass painter, Margaret Pearson, made a copy of The Flower Girl on a glass panel, based upon Young’s print As it reversed the image in Young’s engraving, the glass panel was the same way round as the original painting, although the colours were different Stained glass panel, 36 5 x 29 2 cm, signed ‘E Marg t Pearson 1796’ Victoria & Albert Museum, C 701980 See Andreas Petzold, ‘Stained glass in the Age of Neoclassicism: The case of Eglington Margaret Pearson’, The British Art Journal, Autumn 2000, Vol 2, No 1, p 57, fig 5

[16] William Ward after John Hoppner, The Sallad Girl, 1783, mezzotint engraving, 38 2 x 27 7

cm The Trustees of the British Museum, Museum number 1940, 1109.36

[17] Postle 2011, p 13

These canvases are two striking and beautifully preserved examples by one of the most significant foreign-born artists to make his mark on British art history, Johann Zoffany The Watercress Girl, exhibited in the same 1780 Royal Academy exhibition which featured his masterpiece The Tribuna of the Uffizi (fig 1), and The Flower Girl are supreme character studies inspired by the streets of eighteenth-century London Having until recently been preserved in one single private collection for over two centuries, thus retaining their original gilded frames, this is the first time these works have been offered in full splendour following delicate and painstaking conservation

The Artist & His Influences

Born the son of Court Cabinetmaker and Architect in Regensburg, the young and talented Johann trained under a pupil of Francesco Solimena, an apprenticeship which imbued him with an almost lifelong passion for travel and adventure In 1750 he left Germany for Rome, where he met and came under the influence of portrait painters Agostino Masuc (1691-1758) and Anton Raphael Mengs (1728-1779) After several trips to southern Europe, his first great commissions were to produce Baroque frescos for the Prince-Archbishop and Elector of Trier, blending both complex mythology, religious and decorative painting in one In 1760 Zoffany left to pursue a career as a decorative painter in London, where connections in the world of theatrical and portrait painting gained him the attention of actor David Garrick (1717-1779) that resulted in collaborations which soon made his fame.

His relatively quick acceptance amongst aristocratic patrons eventually occasioned in his introduction to George III and Queen Charlotte, for whom he produced several portraits and conversation pieces which remain amongst the greatest achievements of the period. In 1772, assured of his position and having been nominated as a painter of the Royal Academy in 1769, Zoffany embarked on another journey back to Italy and central Europe to increase his fame on the continent. These years saw him elected to many of Italy’s prestigious academies, alongside his work painting the Italian aristocracy and later the Hapsburg Emperors in Vienna

The creation of the Watercress and Flower girls were undertaken on Zoffany’s return from the continent in 1779 They were executed at a particularly poignant moment in the artist’s career His return from Italy had coincided with his producing The Tribuna of the Uffizi (fig. 1) for Queen Charlotte, a celebration of the artistic treasures of Florence which is rightly described as his masterpiece Despite the acceptance of this work into the Royal Collection, adding to the fact the picture had received mixed reviews, a quick change in tac was required from the painter. After being absent for seven years, Zoffany was quick to observe the shift in public taste since his departure in 1772 This was particularly the case in the growing disinterest in his preferred conversation pieces Scholars have highlighted the Watercress and Flower girls as responses to the increasing fashion for the Royal Academy’s president Sir Joshua Reynolds’ (1723-1792) celebrated ‘fancy pictures’ exhibited during his years of absence This had included Strawberry Girl (1773) (fig. 2), An Infant Jupiter (1774), A Beggar Boy and His Sister (1775) and A Fortune Teller (1779) Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), who also followed this trend, was yet to exhibit any of the rustic country figures widely known from his later years.

The influences at play in Zoffany’s pair, and the ‘fancy picture’ genre in general, are varied and interesting The artist’s experience of Italy is likely to have had some lasting influence. Despite the predominantly aristocratic nature of his work for imperial and princely patrons during his Italian years, evidence attests to painter’s diversion and experimentation with other less noble characters in the years preceding his return In the autumn of 1777 Zoffany produced A Florentine Fruit Stall (fig 3), a strikingly complex and intensely coloured scene featuring humble vendors, clients and beggars which he is presumed to have painted for himself It is plausible that Zoffany may have encountered the lowly-persons painted by Giacomo Ceruti (1698-1767) (fig 4) and Giacomo Francesco Cipper (1664-1736), whose works could be found in collections in Northern Italy during his travels there If these Italians had any influence on Zoffany’s ideas for the street sellers, ultimately, the rough handling found in the Fruit Stall did give way to smooth brushwork and rich yet silvery tones found in these two girls, another sign perhaps of the artist adjusting to contemporary British taste.

Despite the continental influences at play in these images, the enduring popularity of the characters and figures of London provide a vital context for these works London’s female street fruit and market sellers had been a continuing source of inspiration for ballad writers and artistic figures across the centuries. Associated with youthful beauty and a playful and at times alluring innocence, the precarious position of selling wares on the streets of this metropolis came with its own risks

The hazards of prostitution were never far away although some did rise through the ranks in other ways Famously in the case of Nell Gwyn (1650-1687) and King Charles II (1630-1685), even monarchs had taken fruit-sellers-turnedactresses to their beds and bestowed them titles of nobility

In terms of the visual arts, Marcellus Laroon’s (1652-1702) Cryes of the City of London (1688) provided one of the first significant collections of the city’s traders and characters, treated in a playful and caricatured manner However, it was the German-born Philippe Mercier (1689-1760) who made the leap to the painted ‘fancy picture’ in Britain inspired by servants, labourers and working types found in domestic and lowlyspheres A sign of the fancy picture’s early acceptance into the national canon was the fact that the Londoner and ‘father of British art’, William Hogarth (1697-1764), had experiment with this genre himself Hogarth’s Shrimp Girl (The National Gallery, London) (fig 5), a picture which remained with his widow after his death, is perhaps the most famous and comparable example to the works under discussion.

Victorian writers, publishing a history of London characters a few decades later, suggested that watercress sellers were amongst the lowest strata of the city’s street traders [1] Their position had apparently been well below those who carried oranges, chestnuts and walnuts but were more associated with those who sold sprats (cheap fish) and winkles (molluscs) Watercress, commonly grown all year around from the outskirts of the city, bore meagre financial returns It would be hard to imagine a sharper contrast to Zoffany’s refined and extravagant Tribuna, exhibited in the very same 1780 Academy exhibition, than this subject.

1 Johan Zoffany, The Tribuna of the Uffizi, 177277, The Royal Collection, His Majesty, King Charles III

2 Top right: Joshua Reynolds (1723 - 1792), The Strawberry Girl, 1772 – 1773, The Wallace Collection

4

Zoffany’s girl appears dressed in thick red garments with a bonnet on top casting a shadow across her eyes in a manner not uncommon in Reynolds’ work.[2] Overall, the fashion may suggest an attempt to keep out the elements

In contrast to the above, Zoffany’s Flower Girl is far more overt in its sensuality befitting a seller of beautiful blooms. In this case sweet smelling roses are contrasted with a trio of tall-stemmed miniature narcissi (daffodils), which can on occasion resemble the odour of another kind The maiden’s inviting open-mouthed smile, imitating speech or singing, coupled with her open bodice, translucent white undershirt and bosom, draws the viewer into the realms of fantasy and desire

Ultimately, it was initially the physical beauty of the model chosen for the watercress seller that attracted the attention of an anonymous writer in A Candid Review of the [1780 RA] Exhibition who exclaimed 'The artist has been very fortunate in a choice of a most beautiful Girl for his subject and he has copied nature so exactly, that it is not easy to determine whether it is real life or a painting' [3] Curiously, an inscription on John Raphael Smith’s mezzotint engraving of the subject, in the collection of The British Museum, London, explains that ‘the most beautiful girl’ chosen as the subject for this composition was a Jane Wallis [4] It was suggested in a 2011 publication that this may have been a niece of David Garrick’s lawyer, Albany Wallis (17131800) [5] Other suggestions that the model may have been the Irish actress Tryphosa Jane Wallis (1774-1848) do not readily tally with the age of the girl depicted here.

The exact relationship between these two paintings invites speculation It is a mystery why the Flower Girl was never exhibited at the Academy, although they were both compositions were engraved in similar formats by Smith in 1780 and together by John Young in 1784/5 respectively Perhaps the blatant eroticism, as highlighted above, may have been one reason for its non-inclusion. The contrasting visual and thematic content, which might be interpreted as modesty versus sensuality, might lend weight to the suggestion that they were always conceived as a pair

John Raphael Smith’s engraving of the Watercress Girl attested that this painting was in the collection of Zoffany’s patron and director of the East India Company, Jacob Wilkinson (c 17221799). It seems likely that Wilkinson acquired the works directly from Zoffany’s studio They had descended directly through his heirs until recently and were apparently unobserved by scholars until two decades ago or so Wilkinson’s portrait by Zoffany, completed before he left for India in 1782-3, survives at the Prime Minister’s residence at Chequers, Aylesbury

The popularity of these compositions is attested by the fact that copies of them are recorded.[6]

An unattributed pair of paintings identified as a ‘Watercress girl and Market girl’ were also recorded in the London residence of the Earl of St Germans in 1823 [7]

1 H Mayhew, London Labour, vol 2, London 1851, p. 79.

2 See Joshua Reynolds’ Self Portrait (The National Portrait Gallery, London), or Nelly O’Brien (The Wallace Collection, London) for examples for this trend, which ultimately is likely to have been inspired by such shadows found in Rembrandt’s tronies

3 A Candid Review of the Exhibition (being the twelfth) of the Royal Academy. MDCCLXXX. Dedicated to History Majesty By an artist, London, 1780.

4 https://www britishmuseum org/collection/object/P 18 78-0511-1015

5 M Webster 2011 (see Literature)

6 Sold London, Sotheby's, 17 February 1988, lot 252 (as ‘Studio of Zoffany’ with Baring Provenance); A copy of the Flower Girl by James Pearson (active late 18th / early 19th century), was sold London, 20 May 1800, lot 20; An oval ‘Market Girl’, given to Zoffany, was sold from the collection of Henry F Bodicote, London, 15 March 1823, lot 21.

7 MS, An Inventory of the Household Furniture of the Right Honourable Earl of St Germains taken at his late Residence at St James Square Kersen Kernow, Redruth, EL/665.

Self-portrait, c 1775 – 6

Black chalk on white paper (oval),

12 x 11 in (30 5 x 28 cm )

The British Museum, Department of Prints and Drawings