Foreword

The work of Lotte Laserstein first entered my psyche when I visited Agnew’s pioneering exhibition of her work in 1987, which reintroduced the œuvre of this forgotten artist to the world. At that time I had just entered the commercial art market, and I was totally focussed on Old Masters. The term Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) would have been meaningless to me. However, I was so impressed with the body of work that I told my father, who was a client of Agnew’s and a great friend of Dick Kingzett, about the exhibition and we went back together. He too was mesmerised by her art, purchased two works for himself, one of which is in the current exhibition, and very generously bought another for me. So, I have actually been living with the work of Lotte since that time, and I never fail to look at my painting and marvel at its beauty.

It therefore seemed highly appropriate, thirty years later, and now running Agnews, to mount a show of her work as interest in her continues to rise, both as an example of one the many highly talented women painters, photographers, architects and sculptors whose work has unjustifiably been overlooked; but also as a German Jewish emigree who, with the rise of Nazism, was forced to flee from her country to Sweden.

Since the 1987 Agnews exhibition, which Lotte herself came to, as did her favourite model Traute Rose, critical acclaim for her work has steadily increased resulting in the first comprehensive retrospective of her of work at Museum Ephraim-Palais, Berlin in 2003, and another planned at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt and the Moderna Museet, Malmö in 2018/19. In October of this year, her work is included in the forthcoming exhibition at the Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Splendor and Misery in the Weimar Republic. Her work has also recently been purchased by the Nationalgalerie, Berlin and the Städel Museum, Frankfurt.

Expertly curated by Dr. Anna-Carola Krausse, this exhibition concentrates on Lotte’s female nudes and portraits, an important and intimate aspect of her art, characterised by Dr. Krausse as “sensual objectivity”. The immediacy and directness with which Laserstein paints her female nudes is still remarkable today. Indeed, she brilliantly manages to convey this in a way that blurs the distinction between nudes and portraits so that the two genres becomes intertwined and almost interchangeable.

Profound thanks for this endeavour are due to many, most of all to all the generous private and institutional lenders, but also to Anna-Carola Krausse for sharing her knowledge and understanding of the artist, as well as for all her hard work in producing such a beautiful catalogue. Thanks too, to my colleagues, Anna Cunningham and Cliff Schorer. And special thanks to my ever supportive, patient and understanding wife, Alison.

Anthony Crichton-Stuart

“I am unhappy when I don’t paint”

Notes on the life and art of Lotte Laserstein

In the Berlin of the twenties she was celebrated as a Cshining talentC with a “superb ascent” before her: “Lotte Laserstein, the great virtuosa!” Born in 1898 and one of the first women to complete a degree at the Academy of Art in Berlin she made a name for herself with astonishing speed within the city’s diverse artistic landscape. Laserstein’s exhibition debut came after graduation at the age of 29. In the spring of 1928, her painting In the tavern was included in the big annual show at the Prussian Academy. There was admiration for the fashionably dressed young woman sitting alone at a table in a tavern as if it were a perfectly natural place for her to be. There were several reviews in the press, and in the end the City of Berlin purchased the work. This was an encouraging start and heralded an extremely productive period: the next few years gave rise to some of Laserstein’s major works, among them Russian girl, In my studio, At the mirror and the magnum opus Evening over Potsdam (1930). The artist presented her latest paintings in rapid succession at exhibitions for the Berlin region and further afield. Current records indicate that she took part in more than twenty shows between 1928 and 1933. She performed well in competitions, won several awards and saw her works featured in magazines and anthologies. 1931 brought her first solo exhibition at the celebrated Berlin gallery Gurlitt (run by Wolfgang Gurlitt, not to be confused with the art dealer Hildebrandt Gurlitt who sold “degenerate” art under the Nazis). Art critics were soon referring to her as one of the “very best among the young generation of artists”. But after this promising start her career took an abrupt tumble in 1933. In the perfidious logic of the ruling Nazis, Lotte Laserstein, baptized a Christian and thoroughly assimilated into German society, was declared a “three-quarter Jew” on account of her paternal grandparents and subsequently debarred from the public exercise of her profession. In 1935 she was obliged to close her private painting school, set up after graduation to ensure her livelihood, and there were hurdles to buying materials. At best she managed to show her works privately or through the Jewish Cultural Association.

This institution was tolerated until 1941, and through its auspices Laserstein was able to send two paintings – one was In my studio – to the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1937. Life and work became increasingly difficult. At a major nationwide exhibition in summer 1937, the Nazis unmistakably proclaimed their “ethnic” art policy and launched a propagandistic satellite road show on “degenerate art”. A few months later, in the winter of that year, Lotte Laserstein decided to emigrate to Sweden. She had been invited to exhibit at the Galerie Moderne in Stockholm. Its manager was a woman who had recognized the political gravity of events in Germany. This was a timely opportunity to leave Germany with a few of her most important works. Other paintings and drawings were sent in the post by friends until the war broke out, or else brought to Sweden in person. This smuggling operation was not without its dangers, but thanks to these efforts a sizeable portion of her Berlin œuvre was salvaged. It proved far harder, and ultimately impossible, to save Lotte’s mother Meta and her younger sister Käte, still in Germany. Lotte Laserstein sent several applications to the Swedish authorities, after a marriage of convenience in the summer of 1938 had made her a Swedish citizen, but these were all rejected. Lotte’s sister Käte went underground in 1942, surviving the war and the persecution in hiding in Berlin; their mother Meta was arrested and died in the concentration camp at Ravensbrück in January 1943. After these devastating events, an “aversion” prevented Laserstein from returning to Germany after the war. Sweden became her second home, where she was able to build a new career as a painter and where she spent by far the greater part of her life. She could not resume her work with the old intensity and power, however, given the difficult emotional and financial conditions of exile and the pressures of painting to commission, which she experienced increasingly as stressful and artistically inhibiting. Today, her Berlin period is seen as the peak of almost eighty creative years.

Roads to art

Art played its part in Lotte Laserstein’s life from an early age. Even as a child – the elderly painter liked to recall – she had turned down a suitor equally tender in years with the words: “Oh, you are wasting your time with me. I shall not marry, but devote my life to art.” The anecdote may well contain the seeds of legend, but it is indicative. The childish oath is interesting, and not only because she stuck to it: if we consider Laserstein’s prolific œuvre, now estimated as comprising over 10,000 works, and the persistence with which the painter pursued her art even under the most adverse conditions, the pledge to devote herself to art does not seem at all far-fetched. Most striking of all, however, is that a little girl was expressing her interest in a highly unusual career choice for the times. Whatever possessed the child? A glance at her family background is helpful here.

cat. 4

Rear view of sitting nude with long hair, c. 1925

Lotte was born in the little East Prussian town of Preussisch-Holland (now Pasłęk in Poland). Her mother Meta was the daughter of a well-respected district judge. Lotte’s father Hugo was a pharmacist with his own shop. When Hugo died early in 1902, Meta did not re-marry, but moved with her daughters to live with her own mother Ida Birnbaum, also widowed, who shared a home with her youngest daughter Elsa in Danzig (now Gdansk). In this wholly female household Käte and Lotte enjoyed a loving childhood, and the unconventional lack of a manly presence was a defining influence on the girls: both Lotte and Käte would later lead their lives as single working women – and in her art too, Laserstein primarily depicted women. Music, literature and the fine arts were part and parcel of the Birnbaum-Laserstein home, and painting was an almost everyday activity, as Lotte’s aunt Elsa ran a private school of painting where young middle-class ladies learnt the proper use of brush and pen. This is where Laserstein also took her first lessons from 1908.

Classes with Elsa came to an end in 1912 when Meta moved to Berlin with her daughters and mother. If Danzig was the city of Laserstein’s childhood, Berlin was the city of her youth, and ultimately her true home. She became an authentic local specimen, loving the coarse charm and no-frills bluntness of Berliners, their wit, and the dialect that was to colour her own idiom into old age.

Her passion for art took her on enthusiastic trips to Berlin’s great museums, which must surely have contributed to her artistic formation. The works of Hans Holbein and Roger van der Weyden, the art of nineteenth-century Berlin, the realism, naturalism and impressionism in its French and German variations, all made a strong impression on the budding painter, who had by no means relinquished her aspirations. However, her dream of studying art at the Academy was still beyond reach, at least for the time being: not until 1919 did that venerable institution open its doors to women. Lotte’s mother nevertheless accepted and encouraged her daughter’s choice of career. Economic crisis and inflation had not yet depleted the family assets, and so Laserstein was able to study art history at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universät, where she was admitted in 1918 after passing the advanced school certificate, and to take lessons from the reputed Berlin artist Leo von König (1871–1944). Three years later in 1921, she felt mature enough in her art to sit the examination for admission to the Academy. She passed and found herself being taught by the painter and graphic artist Erich Wolfsfeld (1884–1956), whom she greatly admired. Wolfsfeld was still deeply rooted in the artistic traditions of the late nineteenth century. He believed it was essential

6

to study the old masters and that a skilful command of craft was the sine qua non of all artistic production. “Genius is hard work”, the motto he borrowed from Adolph Menzel (1815–1905), became Laserstein’s professional maxim too.

Wolfsfeld was an excellent observer with a brilliant drawing and etching technique. The few known prints by Laserstein clearly reveal her teacher’s influence. With nuanced chiaroscuro shading as in Traute Rose with long hair (p. 9) or subtly reduced lights as in the Rear view of sitting nude with long hair (p. 8), these works are in every respect worthy of her instructor, demonstrating Laserstein’s astonishing gift for this technique, to which – the artist was later to lament – she devoted far too little attention. Her graphic output remained slight, but this makes the surviving specimens all the more precious. The talent for line evident in the etchings also emerges in the sketches that have been preserved. In the finest academic manner Laserstein drew the largeformat study Female nude with a stick, the basis for a little etched ex-libris. The crayon drawing Girl with brown hair (p. 36) with its painterly verve and the sensitive Head study, Traute with closed eyes (p. 26) are further examples of Laserstein’s great talent

in this field, which did not escape the attention of Käthe Kollwitz. In 1930 she was on the jury that awarded the prestigious Deutscher Staatspreis, for which Laserstein had been nominated. After the jury met, Kollwitz wrote almost apologetically to her colleague Wolfsfeld: “I thought the works by Miss Lotte Laserstein were very good, infinitely better drawn than those of [the eventual winner] Vax” (handwritten letter from Käthe Kollwitz to Erich Wolfsfeld dated 7 January 1930, private collection, USA).

The painter owed more than a solid training in technique to her revered “master”, as Lotte respectfully called Wolfsfeld throughout his life – apparently playing on the alternate connotations of virtuoso maestro and master of a medieval guild. Wolfsfeld’s empathetic realism, combining sober observation with subtle psychological perception, and his delicate naturalism free of loud, spectacular and expressive elements left tangible traces in Laserstein’s work. And for Laserstein, just as for Wolfsfeld, people were the central theme.

Faces of the time: typecast individuals and individualized types

With this fundamental interest in depicting people, Lotte Laserstein was well in tune with the spirit of the twenties. During the Weimar Republic the visual media devoted considerable space to human subjects. There was a notable renaissance of the portrait, a genre somewhat neglected in previous decades. Art dealers initiated a plethora of portrait exhibitions and themed competitions with the support of art writers, while the specialist and illustrated press alike featured broad debates about the nature and significance of a painted likeness. Bourgeois portrait painting, which sought to convey a specific character, was discarded in favour of a fondness for typologies and a levelling of personal traits. Now the focus was on categories, not individuals. This tendency to typecast cannot be ignored in Lotte Laserstein’s portraits. She too depicted the proxies of an age. The multiple manifestations of the modern female urbanite fascinated her in particular. In the late twenties, emancipated “New Woman” was a fashion phenomenon, moulded and nourished by the media. Lotte Laserstein, who had cast aside any ideas of marriage or family in order to pursue her profession, evidently identified greatly with this image of woman. She is not overtly critical of this role construction, but her portraits of women resist conventional clichés. Although she persuasively typecasts her subjects, the way she sees women never results in stereotyped reification.

With discerning technique she chronicles fashionable urban ladies in cafés, athletic young women playing tennis and girls applying their make-up. Nevertheless, although she is a neutral observer, Laserstein is not simply placing her sitters on show. Matter-of-fact precision blends here with sympathetic identification; her brush always retain their dignity and individuality in facial expression, eyes and posture.

This is doubtless why these works have lost none of their suggestive impact and are enduringly contemporary.

At first sight Lotte Laserstein’s sober, unsentimental realism betrays an affinity to Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), the representational style that evolved in manifold ways during the twenties. And yet her works do not quite fit inside this pigeonhole. We will search in vain for the aloof perspective and sleek, metallic lack of warmth that are its usual hallmarks. She does not indict social evils, she does not exaggerate or caricature, but she does express her view of the everyday world in brushwork that highlights material textures with a well-controlled sensuality. Laserstein’s paintings are unusually calm. The roaring twenties fall quiet here, giving way to a prescient silence and often a touch of melancholy. Her visual universe oscillates between objectivity and sensitivity, monumentality and intimacy, detachment and

proximity. It reflects a “different Modernism”, a kind of realism which, unlike those avant-garde movements which cast tradition over board, draws consciously on the prototypes of art history and seeks to renew art out of the old spirit without lapsing into epigonal eclecticism.

This is a very particular approach to taking stock of her surroundings: in a dual sense, Laserstein’s paintings express an age defined, to quote the philosopher Ernst Bloch, by the simultaneity of non-simultaneous, heterogeneous phenomena. This non-simultaneity is also a feature of Laserstein’s art: in style and technical command her work is distinctly traditional, and yet in motif, composition and statement it is irresistibly contemporary.

The painter draws with virtuosity on the rich repository of art history, quoting, alluding, modifying. With the same facility, she taps into the aesthetic vocabulary of pictorial practices of her own day such as photography and advertising. She was surely familiar with the portrait photography which, from the mid-twenties onwards, made growing use of head-on close-ups as a stylistic device. There are evident similarities between Laserstein’s compositional technique and works by photographers of her time who adopted this novel, direct angle. Not unlike these camera portraits, Lotte Laserstein’s Russian girl derives its particular effect from the contrast between juxtaposed light and dark. The black hair merges into the fur of the upturned collar caressing the girl’s chin, and her bright face stands out in a regular, concentrated oval.

On first sight the young Russian exudes a strong presence with her glistening red lips and dark eyes – and yet she is strangely unapproachable. The longer one looks at this picture, the more the girl’s gaze seems to turn inwards. This clever mix of direct close-up and simultaneous retreat lends the en-face portrait a psychological dynamic and a suggestive impact that is in no way diminished today. A similarly austere composition characterizes the Renaissance-style Self-portrait in black, where

before trees, c. 1932

the broad-brimmed hat and dark scarf create a frame for a three-quarter profile which fills the format. In painting herself, the artist not only focuses on the face, but adds the hint of a hand holding a brush in the bottom left-hand corner.

Me, myself and I: Lotte Laserstein’s self-portraits

Self-portraits are a constant thread in Laserstein’s work. When they are exhibited together, these exercises in painterly self-mirroring can be read as a lifelong journal with insights into the artistic and emotional disposition of the painter. The earliest portrait of the artist of which we are currently aware is the Self-portrait with white collar (cat. no. 1) from around 1923. Its striking feature is the intense look the artist casts at the viewer, or at herself in a mirror, oscillating between uncertainty and selfwilled defiance. We encounter a similarly powerful gaze in the Self-portrait with hand on breast painted not long afterwards. There is greater assurance, and possibly greater knowledge, in the way the painter looks into herself and out of the frame in the Study with two self-portraits (p. 23) and the Self-portrait before trees, which date from the early thirties.

2

Self-portrait with hand on breast, c. 1924

It is noteworthy how often Laserstein depicted herself in her profession as a painter. We see her absorbed in her work in the manifesto-like In my studio (p. 29), and her first self-portrait in Swedish exile again shows her in mid-process (p. 49). Even when Lotte Laserstein presents herself in delicate pastels as a fashionable woman in a little green hat (p. 25), this turns out on closer scrutiny to be a mirrored studio scene. Sketchily discernible on the left is a hand with a brush. The painted role play Mackie Messer and me (p. 47), unusually featuring Laserstein without the tools of her trade, is in many respects an exceptional self-portrait. Here we find the artist at the side of Mack the Knife, the anti-hero of Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera.

Friend, muse, model: working with Traute Rose

More frequently than herself, Lotte Laserstein painted her friend Traute. In late 1924 Laserstein met Gertrud Süssenbach, known as Traute, who took the surname Rose on marriage. Their friendship was of huge significance to Lotte, both personally and in her artistic development. Traute Rose became Lotte Laserstein’s “favourite model”. With her tremendous talent for acting, Rose seems to have been a most stimulating subject for Laserstein. Although usually captured portrait-fashion, the model tended to adopt a specific role. Athletic and androgynous, Traute was perfectly cast as the

modern woman. She is the boyish garçonne with tie or the fine lady with white gloves, the young woman casually sporting a green pullover or trimly turned out in a chequered blouse and fashionable brown pinafore dress.

It was in the twenties that Coco Chanel set out her creed, declaring fashion and dress style to be part of how a woman expressed her personality. The fashion-conscious artist probably endorsed this opinion wholeheartedly. Underlying this ethos there is a commitment to self-determination for women, something the artist expressed again and again in her portraits. Her sitters are certainly en vogue, but never faceless mannequins, female clothes racks or peel-away transfers of some contemporary cliché. The painter lends her protagonists self-assurance. Even in relatively unspectacular poses or ordinary scenes, they are individuals exuding vitality and composure.

Traute not only stood in for different types of women; she was also the artist’s preferred nude. Although Laserstein sometimes hired other friends or acquaintances to sit for her in fashionable clothes, there is no evidence that anyone other than Traute Rose posed for the Berlin nudes.

Sensual objectivity: nudes

The first major nude painting that Laserstein worked on with Traute was In my studio (p. 29), monumental in its impact but actually quite small. The eye-catching magnet here is doubtless the naked, slumbering Traute, stretched out across the full width of the horizontal format. Sensitively adapting her technique, now dabbing alla prima, now building up layers, Laserstein celebrates her friend’s beautiful physique with Titian-like contours. The impression is sensual, but the brushwork is painstaking. Every detail – fingernail, earlobe or stray hair – is recorded in the manner of the old masters. This boldly exhibited command of the painter’s craft is an effective way for a young woman who has stormed the academy gates to demonstrate that she is the professional equal of her male fellows, for she is tackling a genre that was for many centuries a purely masculine domain. Just as she seizes on the classical iconography of the sleeping Venus for her studio painting, so too she renders traditional topoi contemporary in her other depictions of nudes. In works like Rear view of sitting nude (Traute Rose) (p. 33), Rear nude with raised arms (p. 31), Rear view of nude with washbowl (p. 27) or At the mirror (p. 32), she transports the woman washing or looking at herself in a mirror into the modern day. Both are long-established motifs in Western art, and Laserstein consciously accepts this continuity, but her sympathetic depictions of the model do not emulate the voyeuristic male gaze. Excelling here with a painterly verve, she is at the pinnacle of her artistic output. The intimacy with the way she both presents and paints her models at times reminding us of the work of Edgar Degas.

Given the multitude of paintings, studies and sketches that Lotte made of her modelfriend Traute, whom she lovingly and imperiously nicknamed “Puppy”, it is hard to credit her admiring claim that the appeal derived entirely from Traute’s “ability to retain even difficult poses for a long time”. In many works there is an intimacy and (erotically charged) sensuality that makes a closer relationship between these two women conceivable. There is no concrete evidence that any such relationship occurred, not even in the correspondence that lasted almost forty years. What the post-war letters do express, however, is the decisive role the painter attributes her friend in her own artistic output. When recalling the Traute paintings, Laserstein consistently refers to “our pictures”, emphasizing that the painter and the model were on an equal footing, working together in a spirit of creative collaboration.

The contact between Lotte and Traute broke off during the war, but it was restored in 1946 on the initiative of Traute’s husband Ernst, and the friendship continued for the rest of their lives. When they visited each other, Rose frequently resumed her role as a model, and so more Traute pictures emerged as the years went by. As a nude sitter, however, the “still beautiful woman” with the “splendid body”, as Laserstein described her, was no longer available. Nevertheless, Traute Rose was naturally at Lotte’s side when the exhibition at Agnew’s opened in 1987.

In Swedish exile

Laserstein’s fresh start in Sweden began well. Although her exhibition at the Galerie Moderne met with a subdued response in the Swedish press, the painter was offered a number of prestigious commissions to paint Swedish society portraits. Her clients included aristocrats and celebrities from the arts, politics and industry. Laserstein’s painterly virtuosity was much appreciated by clients with the resources to award commissions, and these had a particularly strong interest in portraits. One of her first clients was Count Erik Trolle, chamberlain to the Swedish king. During the breaks while she worked on Trolle’s portrait, Laserstein made her first self-portrait in the country in the spring of 1938 (p. 49). This is her painted calling card, and it shows her as she would like her new audience to perceive her: as a professional painter and a self-assured, attractive woman. This self-portrait betrays none of the deprivations or anxieties she suffered as an emigrée. And yet there is a touch of scepticism in this initially confident pose. The quizzical glance in the mirror reveals mixed feelings; pleasure at new commercial success comes hand in glove with doubts about whether she has done the right thing.

Laserstein was fortunate, unlike many other artists who went into exile, in that she managed to salvage some of her art. Not wanting to jeopardize her situation in

The painter and Madeleine,

Sweden, she turned increasingly to landscape painting, a genre that had only played a minor role during her Berlin period, essentially from the early thirties when she took regular study trips into the countryside with her pupils. To improve her sales, she also incorporated still life into her repertoire, a genre that she claimed was not really her forte, but which was very popular with the public. This shift in motif, as well as an evident change in the style of her portrait painting towards a lighter, airier technique and a paler palette, illustrates the need to adjust to a different public taste to retain her commercial viability. At the same time, a new mood breaks ground in her paintings, reflecting the uprooting and uncertainty she experienced as an artist in exile. The variegated, almost probing style of those early Swedish years is far removed from the strong composure of the Berlin period. The sense that she has lost her artistic home is conveyed in Laserstein’s letters to Traute Rose. In 1946 she wrote to her friend: “Sweden is nice, the people are friendly, but for all their sympathy it doesn’t touch them. […] So for all the amiability and cordial relations there is always a gulf. […] That is the fate we émigrés face. Only my work earths and roots me, and that is my good fortune, even if the artistic environment is unfavourable. One experiments, if anything more wildly, or at least with less talent than during the last years there [in Berlin]. My master [Erich Wolfsfeld] would not have liked it, and neither do I. But as people always want to recognize natural forms in a portrait, my work is nevertheless held in esteem, in private more than in the press. The good master writes that I shouldn’t care tuppence about public opinion but just get on with what I am doing, and I have no other choice.”

Not only did the urbanite need to acclimatize to the much quieter cultural atmosphere in Stockholm, but the separation from her model Traute proved a painful loss. She sought to compensate with the attractive Margarete Jaraczewsky, known as Madeleine, another emigrée from Germany. She was fifteen years younger, held a doctorate in economics, was happy to sit for the artist and did so as a favour for many years from 1939.

In the double-portrait The artist and Madeleine (p. 19) Lotte Laserstein formulates her yearning for the kind of symbiotic artist-model relationship which she had enjoyed with Traute Rose. The contours of the two half-figures are almost congruent. Looking in opposite directions, the two women create the impression of a Janus-headed figure, from which a unique circular motion draws its dynamics. However, the many portraits and nudes which Laserstein was to paint of Madeleine in the coming years reflect a quite different relationship with her sitter. We rarely encounter the intimate duologue between painter and model which marked the early works with Traute Rose.

Torn from oblivion

Escape to Sweden saved Laserstein, and yet leaving Germany snapped her life in two. In the eighties the artist wrote a short passage describing this huge rift in her life and in the role her art played in forging her identity: “Reality? To me, that has always been my work, ever since I was a child. My life was carved into two chunks of almost equal size: childhood, youth, training, my first independent work and leaving Germany. Then a new, laborious start in Sweden. If I had not had my own reality in my paintbox, that little case that led me from Skåne via Stockholm to Jämtland, I could not have borne those years when everything was taken from me: family, friends and home. I retrieved some of it thanks to ‘my only reality’.”

Moreover, expulsion from Germany also meant expulsion from art history, an effect the National Socialists had certainly intended. Emigration deleted the painter from collective memory. After 1945 hardly anyone recalled the young artist with the promising career. Works purchased by public institutions, which might have testified to Lotte Laserstein’s existence and her art, had fallen prey to air raids or the Nazi iconoclasm. Her first sale, the painting In the tavern, had been confiscated as “degenerate” and was thought lost until it surprisingly turned up again at an auction in 2012. Although Laserstein’s name was officially indexed for purging by the Nazis, she was never mentioned in the German art journalism that set out to rehabilitate defamed artists: in the post-war years, all sights were on abstract art, and the work of this once lauded realist sank into oblivion. Almost half a century passed before her splendid rediscovery.

When Agnew’s and Belgrave Gallery staged their Laserstein show in London in 1987, reviewers were just as enthusiastic as their colleagues in the twenties and thirties, and people were surprised that nobody had ever heard of this exceptional artist. The Times celebrated the painter, unjustly forgotten by passing time and changing artistic fashion, as one of the “most exciting discoveries”, praising the “fresh intelligence and unusual sensuality” of her works. The exhibition initiated and curated by Caroline Stroude (now Caroline Gee) was Laserstein’s first outside Sweden, and it was the prelude to her international reclamation. Berlin hosted a further highlight in 2003 with the retrospective Lotte Laserstein – My Only Reality (a partnership between Das Verborgene Museum and Stadtmuseum Berlin based in Museum Ephraim-Palais).

After many years of research into Laserstein’s life and œuvre, this event brought together over 150 works and yielded a comprehensive monograph with a catalogue raisonné.

By 2010, when the Nationalgalerie in Berlin announced its spectacular purchase of Laserstein’s masterpiece Evening over Potsdam (sold at Agnew’s in 1987), the painter’s place on the map of art history had finally been restored. Purchases by other museums and her inclusion in major themed exhibitions such as Vienna–Berlin: The Art of Two Cities (Berlinische Galerie, Berlin/Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna 2014/2015), Twilight over Berlin (Israel Museum, Jerusalem 2016) and Splendor and Misery in the Weimar Republic (Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt 2017) are clear endorsements of Laserstein’s artistic significance. Today her works can be seen, for example, at the Nationalgalerie and Kupferstichkabinett – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, the Stadtmuseum Berlin, the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, the New Walk Museum and Art Gallery in Leicester, the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington.

The art market has likewise responded to this growing interest. Not only have prices risen, but as the artist gained visibility in recent years private collections turned up works that were either previously unknown or believed lost. The two works Lady in black evening dress with cigarette (p. 41) and Lady with red beret (p. 43) are both formidable specimens of these new discoveries. Another première here is the presentation of the painting Rear view of sitting nude (Traute Rose) (p. 33), which has never been shown in public before.

Lotte Laserstein’s life lasted almost a century. She nearly did fulfil her heartfelt desire to “paint till the end”. Until shortly before her death, the old lady would sit at her easel for a few hours of every day. Lotte Laserstein died on 21 January 1993 aged 94 in the southern Swedish city of Kalmar.

Plates

cat. 16 Study with two self-portraits, c. 1930

In my studio

The painting with the unassuming, programmatic title was produced in 1928 in the first studio the artist called her own, and it is one of Laserstein’s major works. With this insight into her workplace, Laserstein presents her own view of art and defines her role as a professional painter. She looks earnest, as so often in her self-portraits. The main attraction in this surprisingly small canvas is doubtless the nude stretching the full width of the format in the classical pose of a “sleeping Venus” – the slumbering Traute. The painter remains in the background, almost vanishing behind the radiant beauty of her model and thus demonstrating the vital role played by Traute in Lotte’s creative process. The sleeping figure is doubtless the eye-catching element in the picture, and yet also a barrier holding the viewer at bay.

We watch the scene as though it were taking place on a stage we cannot enter. The painter and the model are locked in their own world, diligently performing their functions with only each other for company. The pale snowy light falling through the broad panoramic window casts a subdued, concentrated silence.

Despite the charged atmosphere and painstaking depiction, there is a mystery to the scene: What is the artist actually painting? What we ourselves can see, observing her model from the front through a big mirror? If we look at the canvas on the easel in the centre, it is obvious that the wood-based studio painting in front of us cannot have been generated by this situation. The scene may look authentic, but it does not reflect the facts. Instead, it is a sophisticated pictorial invention, allowing Laserstein to shift attention from the ‘reality’ she is depicting to the situation in the painting. We cannot tell from the scene whether she is working on a nude. The only evidence is the picture before us. It is a kind of double exposure, showing the artist at work and at the same time the fruits of her labour: a brilliant specimen of painting.

Rear nude with raised arms

Nudes were a major feature of Lotte Laserstein’s work in the late twenties and early thirties. This genre had been a purely male domain for hundreds of years, but in the early twentieth century female artists advanced into this long-forbidden terrain, among them Paula Modersohn-Becker and Zinaïda Serebryakova. In this sense Laserstein’s intensive engagement with the subject was no longer exceptional. What is special, however, is the painterly vigour she devotes to the female body and her skilful ability to translate established traditions into a contemporary formula. The model for this half-nude,Traute Rose, also adopts a classical pose. The naked breast and the hands clasped behind the head are reminiscent of the earlier etching Rear view of sitting nude with long hair (p.8).

For this study, dating from the thirties, Laserstein used an oil-on-paper technique of her own. The vitality and sensual presence indicate that she had reached the height of her artistic prowess. With a firmly composed line and delicate brush she creates a rear view of a nude which gathers its particular aesthetic appeal from a blend of rapid background expressivity and a subtly glazed modulation of the body. With the model turned away and the muted warmth of the browns, the calm emanating from this composition sets off the lively play of light to even better effect.

Sitting model – Madeleine

During her exile in Sweden, Lotte Laserstein continued to paint the occasional nude. This was, in a way, her artistic antidote to the commissions. “Here one can experiment now and then, something one cannot afford to do when portraying fine gentlemen,” she wrote appreciatively to her friend Traute Rose. Her preferred sitter when creating these “pictures for myself” was Margarete Jaraczewsky, known as Madeleine, her junior by 15 years. Laserstein worked with her on some very personal artist-with-model studies and several nudes, including this rear view bathed in soft light. The way the model has turned away and the fine modelling of her back inevitably recall earlier works, such as Rear view of sitting nude (Traute Rose) and Rear view of nude with washbowl. The vivid brushstrokes lend the figure a lively presence. Although the position seems casual, it is carefully constructed. A closer examination of the composition reveals an interesting interplay of assorted triangles that virtually surround the figure: one, for instance, formed by the legs, one between the left arm, leg and body, and another from the right arm downwards. These subtle geometric shapes form a stimulating contrast to both the soft contours of the body and the loose, expressive suggestion of the sofa Madeleine is sitting on, the blanket or dress to her right and the undefined background.

Lady in black evening dress with cigarette

For Lotte Laserstein the modern “New Woman” of the twenties was no vamp, no bleary-eyed sophisticate or emphatically masculine type of the kind so often portrayed by Otto Dix or Christian Schad. To the unmarried, professional artist, she was the natural expression of a way of life and a frequent motif. Laserstein’s delight in depicting beautiful women is unmistakable; apart from later commissions in Sweden, her portraits of men are extremely rare. In her portraits of women, she pays tribute to various contemporary types – the casual flapper and the athlete, the elegant lady and the intellectual – but she resists cliché to capture her sitter’s essence. Permitted their individuality and executed with class, Laserstein’s women are a counterweight to the mass of stylized fantasy women in the media.

The Lady in black evening dress with cigarette is feminine and self-assured. Given the painterly differentiation in this recently discovered work, it seems almost inappropriate to call it a drawing. The delicately superimposed layers of variegated shading, the skilful touches of coloured pastel and the white chalk highlights to evoke shimmering light on skin are fine examples of Laserstein’s masterly technique. She cunningly uses the brown of the unworked paper to create a warm fleshy tone, while in the folds of the dress the visible underlay reinforces the sense of heavy material and glistening cloth.

Lady with red beret

Although the clothes and haircut – the famous bob – indicate the 1920s, there is a fresh, contemporary feel to this work that prises it out of its own time and captivates the viewer. Questions soon arise: What is the young woman looking at? Where is her focus? Is it on something in her mind’s eye? Is she watching a scene outside the frame or listening to a companion we cannot see? Laserstein deliberately dispenses with any spatial indications or narrative accessories, keeping the scenario unequivocally open. Despite the situational uncertainty and the sketchy quality where the figure fades away around the legs, the artist has accomplished a work of powerful concentration and atmospheric charge centered on the young woman. This is about her. She is the sole theme of the work.

The Lady with red beret is the result of a complex mixed technique. The combination of wet and dry pigment is technically ingenious; apart from chalk, charcoal, pastel and watercolour, there is even a little oil paint, applied wafer-thin to lend a hidden sheen to the dress and scarf. The modelling of the face also draws life from these meticulously superimposed layers that never quite conceal the underlying surface, incorporating the shade of the paper itself as a creative element. The many different nuances of colour in their layered and interlacing flows – the dress is a veritable symphony of multiple reds – and the technically intricate combination of different materials yield a delicate yet compact surface. Sensitivity and strength work hand in hand.

Mackie Messer and me

The self-portrait Mackie Messer and me has a place of its own in Laserstein’s œuvre.

Not only is this one of her very rare self-portraits featuring a male figure – with one other exception, Laserstein always painted herself with Traute Rose during her Berlin period. It is also one of the few examples where we do not see the artist at work.

Dressed in a sumptuous feather hat and graciously sporting a little parasol in her finely gloved hand, she glances vigilantly out of the frame. Her shady companion Mackie Messer, the anti-hero of Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, keeps a low profile behind the costumed painter. He is muted in colour and conspicuously unformed.

The garb in which Laserstein appears here, combining baroque flamboyance with the iridescence of operetta, is not merely uncustomary for the painter, but hard to reconcile with Brecht’s idea of epic theatre.

Laserstein’s painting is not actually a reference to the stage production premiered in 1928 at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm in Berlin, but to the film version directed three years later by G. W. Pabst. As a fan of Brecht and passionate cinema-goer, Laserstein must have seen the box office hit. It is not hard to tell from the costume what role she has chosen for herself: she is Polly, Mackie Messer’s bride and the daughter of his adversary, the beggar king Peachum.

The release of the film triggered right-wing protests. By identifying with the cinematic Polly, she is expressing support for the film, which – like the play – was banned by the Nazis in 1933.

Self-portrait at the easel

Self-portrait at the easel, itself resembling a tall mirror, was the first self-portrait Laserstein painted in Swedish exile. It was done in early summer 1938 while she was working on the portrait of an eminent model, the king’s chamberlain Count Erik Trolle – in other words, during a highly promising period when business was flourishing. Laserstein is looking very feminine. The open smock and the clothes hugging her contours beneath have none of the buttoned-up severity of earlier self-portraits. The artist has chosen an anonymous background with nothing to suggest the elegant surroundings at the count’s residence. The painter is literally in a void. The only thing filling this vacant environment is herself – her person and her work. And so Laserstein portrays herself painting, her hand frozen in mid-air with the brush. In the iconography of artists’ self portraits there is nothing unusual about this stance, but the direction of the implement is noteworthy here. The brush is not pointing in the customary manner at the canvas, but at the artist. It blends so closely with her hair that one might think Laserstein were painting herself. Not only that, but the position of the easel creates an optical illusion, as if the painting hand does not belong to the person portrayed, but has sprung from the painting in progress, from the art itself. The painter appears in the work as a creative force, lending herself shape – and thereby identity – by the act of painting. With this auto-creation in painterly form, Lotte Laserstein adopts a convincing metaphor to express how important her work is to her in exile: she achieves self-realization through her art and records it in her art.

cat. 30 Self-portrait at the easel, 1938

List

of exhibited works

1 Self-portrait with white collar, c. 1923

Oil on cardboard, 32 x 24 cm. | 12 5/8 x 9 1/2 in.

Signed later lower left: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection, Germany

2 Self-portrait with hand on breast, c. 1924

Graphite on paper, 48.8 x 37.4 cm. | 19 1/4 x 14 3/4 in.

Signed upper left: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection

Illustrated page 15

3 Traute Rose with long hair, c. 1925

Etching, 14.8 x 11.5 cm. | 5 7/8 x 4 1/2 in.

Not signed

Private collection, Germany

Illustrated page 9

4 Rear view of sitting nude with long hair, c. 1925

Etching, 34.5 x 24 cm. | 13 5/8 x 9 1/2 in.

Signed lower left under the plate:

Lotte Laserstein

Private collection, UK

Illustrated page 8

5 Nude leaning forward (Traute Rose), c. 1927

Chalk and charcoal on paper, 45 x 56 cm. | 17 3/4 x 22 in.

Signed later lower left: Lotte Laserstein

Illustrated page 17

6 Female nude with a stick (study for an ex-libris for Traute Rose), 1927

Graphite, charcoal, red chalk and gouache on paper, 67.8 x 37.6 cm. | 26 3/4 x 14 3/4 in.

Signed later lower right: Lotte Lasertein

Illustrated page 10

7 In my studio, 1928

Oil on panel, 46 x 73 cm. | 18 1/8 x 28 3/4 in.

Private collection, USA

Signed lower right: Lotte Laserstein

Illustrated page 29

8 Russian girl, c. 1928

Oil on panel, 32 x 23 cm. | 12 5/8 x 9 in.

Signed upper left: Lotte Laserstein

Linda Sutton & Roger Cooper, London

Illustrated page 12

9 Self-portrait in black, c. 1928

Oil on plywood, 20 x 20 cm. | 7 7/8 x 7 7/8 in.

Not signed

Private collection, Berlin

Illustrated page 13

10 Girl with brown hair, profile to the left, c. 1929

Charcoal and chalk on paper, 44 x 30.5 cm. | 17 3/8 x 12 in.

Signed later lower right: Lotte Laserstein

Illustrated page 36

11 Head study, Traute with closed eyes, c. 1929

Charcoal and coloured chalk on paper, 50 x 30 cm. | 17 3/4 x 11 3/4 in.

Signed later lower right: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection, Germany

Illustrated page 26

12 Rear view of nude with washbowl, c. 1929

Charcoal and chalk on cardboard, 60 x 44 cm. | 23 5/8 x 17 3/8 in.

Signed upper right: Lotte Laserstein

Illustrated page 27

13

Rear view of sitting nude (Traute Rose), c. 1930

Oil on canvas,

70.5 x 55.8 cm. | 27 3/4 x 22 in.

Signed upper right: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection

Illustrated page 33

14 Lady in red with white hat, c. 1930

Oil and chalk on paper,

43.5 x 31.9 cm. (irregular) |

17 1/8 x 12 1/2 in.

Signed later lower right: Las.

Illustrated page 44

15

Self-portrait in a green hat, c. 1930

Pastel, chalk and charcoal on paper,

56 x 40 cm. | 22 x 15 3/4 in.

Signed later upper left: Lotte Laserstein

Illustrated page 25

16 Study with two self-portraits, c. 1930

Charcoal on paper,

56.7 x 36.4 cm. | 22 3/8 x 14 3/8 in.

Signed and inscribed later lower left:

Lotte Laserstein (Berlin)

Illustrated page 23

17 Traute Rose, profile to the right, c. 1930

Charcoal on paper,

49 x 35 cm. | 19 1/4 x 13 3/4 in.

Signed later lower right: Lotte Laserstein

Illustrated page 24

18 At the mirror, 1930/31

Oil on canvas,

124.5 x 88.8 cm. | 49 x 35 in.

Signed lower right: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection

Illustrated page 32

19 Rear nude with raised arms, 1930s

Oil on paper, 65 x 50 cm. | 25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in.

Signed upper left: Lotte Laserstein

Illustrated page 31

20 Lady in black evening dress with cigarette, c. 1931

Chalk, charcoal, pastel and gouache on paper, 65 x 50 cm. | 25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in.

Signed lower right: Lotte Laserstein

Dr. Michael Nöth, Kunsthandel und Galerie

Illustrated page 41

21 Lady with red beret, c. 1931

Oil and pastel on paper, 65 x 50 cm. | 25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in.

Signed lower left: Lotte Laserstein

Dr. Michael Nöth, Kunsthandel und Galerie

Illustrated page 43

22 Traute Rose with tie, c. 1931

Oil, watercolours and crayon on paper, 43 x 49 cm. | 16 7/8 x 19 1/4 in.

Signed later upper right: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection, Berlin

Illustrated page 16

23 Traute Rose with red cap and chequered blouse, c. 1931

Oil on paper, 92 x 69 cm. | 36 1/4 x 27 1/8 in.

Signed lower left: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection, Bremen

Illustrated page 38

24 Traute Rose with white gloves, c. 1931 Oil on paper, mounted on cardboard, 94 x 65 cm. | 37 x 25 5/8 in.

Signed later upper right: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection, London

Illustrated page 39

25 Traute in a green pullover, c. 1931 Oil on paper, 76 x 54 cm. | 29 7/8 x 21 1/4 in.

Signed lower left: Lotte Laserstein

Maria Duke, Stockholm

Illustrated page 45

26 Portrait of a girl, c. 1932 Oil on paper, 40 x 30 cm. | 15 3/4 x 11 3/4 in.

Signed lower left: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection, UK

27 Self-portrait before trees, c. 1932 Oil on canvas, 36 x 31 cm. | 14 1/8 x 12 1/4 in.

Signed lower left: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection, UK

Illustrated page 14

28 Mackie Messer and me, c. 1932 Oil on plywood, 53.5 x 43.7 cm. | 21 x 17 1/4 in.

Signed lower right: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection

Illustrated page 47

29 Lady with hat, profile to the left, c. 1936 Oil on paper, 36 x 30 cm. | 14 1/8 x 11 3/4 in.

Not signed

30 Self-portrait at the easel, 1938 Oil on plywood, 128 x 47.5 cm. | 50 3/8 x 18 3/4 in.

Signed upper right: Lotte Laserstein

Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin

Illustrated page 49

31 Lady in blue with hat and veil, c. 1939

Oil on paper, 63.5 x 45.5 cm. | 25 x 17 7/8 in.

Not signed

Thilo Herrmann, Offenbach/Main

Illustrated page 2

32 The painter and Madeleine, c. 1940

Chalk, pastel and charcoal on paper, 60 x 46.5 cm. | 23 5/8 x 18 1/4 in.

Signed lower right: Lotte Laserstein

Private collection, UK

Illustrated page 19

33 Nude, sitting in a chair, c. 1941

Oil on panel, 60.5 x 50 cm. | 23 7/8 x 19 3/4 in.

Signed upper left: Lotte Laserstein

Illustrated page 37

34

Sitting model – Madeleine, c. 1943

Oil on canvas, 61.5 x 50 cm. | 24 x 19 3/4 in.

Signed lower right: Lotte Laserstein

Illustrated page 35

35 Self-portrait, 1950

Oil on canvas, 35 x 32.5 cm. | 13 3/4 x 12 3/4 in.

Private collection, UK

This is both a loan and selling exhibition. If no whereabouts are listed the work is for sale. There is also a small group of drawings, oil paintings and sketches by the artist which are not exhibited, but which are available for viewing and purchase by request.

Biography

1898 Lotte Laserstein is born in Preussisch-Holland (now Pasłęk in Poland) on 28 November, the first daughter of Hugo Laserstein, a prosperous pharmacist, and his wife Meta, née Birnbaum.

1902 Death of her father. Meta and her two daughters Lotte and Käte move to Danzig to share a household with Meta’s mother Ida Birnbaum and sister Elsa.

1908 First art lessons in Elsa Birnbaum’s private school of painting.

1912 The family moves to Berlin.

1918 Lotte studies philosophy and art history at Friedrich Wilhelm University, Berlin. She also attends a school of applied arts.

1920–1921 Private art training with Leo von König (1871–1944).

1921–1927 Lotte studies at the Berlin Art Academy under Erich Wolfsfeld (1884–1956), from 1925 to 1927 in his master class.

1924 Lotte meets her model Traute Rose.

1925 Medal for artistic achievement from the Ministry of Art and Science.

1927 First studio of her own, where she also runs a private painting school.

1928–1933 Very productive years when she produced many of her best works.

1928 The City of Berlin purchases her painting In the tavern.

1931 Personal exhibition at Galerie Gurlitt, Berlin.

1931–1935 Lengthy summer trips to the country with her pupils. from 1933 As a Jew, Laserstein is no longer allowed to exhibit.

1935 Her private teaching studio is closed. She is not allowed to buy paint or materials. She earns a living as an art teacher at a private Jewish school.

1937 Emigration to Sweden.

December exhibition at the Galerie Moderne in Stockholm, followed by prestigious portrait commissions.

1938 Pro-forma marriage to Sven Marcus to obtain Swedish citizenship.

Fruitless efforts to help her mother and her sister Käte leave Germany.

1943 Meta Laserstein dies in Ravensbrück concentration camp; Käte goes into hiding, surviving the war in Berlin.

1946–1950s Difficult years professionally and personally.

Contact resumes with her friend Traute Rose and Traute’s husband Ernst in Germany.

1954 Purchase of a summer home on the island of Öland.

1959 Lotte moves from Stockholm to Kalmar.

1960s Trips to France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Israel and the United States. Lengthy visits to Ascona, Switzerland.

1987 Exhibition at Agnew‘s and Belgrave Gallery, London, heralding Lotte Laserstein’s international rediscovery.

1993 Lotte Laserstein dies in Kalmar on 21 January, aged 94.

2003 Major Laserstein retrospective at Museum Ephraim-Palais, Berlin.

2010 The Nationalgalerie in Berlin purchases Laserstein’s magnum opus Evening over Potsdam (1930).

2013/14 Moderna Museet, Stockholm, and Städel Museum, Frankfurt, purchase works by Lotte Laserstein.

2017 Premiere of the stage play Evening over Potsdam (by Lutz Hübner, Sarah Nemitz) at Hans-Otto-Theater, Potsdam.

Imprint

Lotte Laserstein’s Women

9 November – 15 December 2017

Agnews, London

Text Anna-Carola Krausse

Translation Kate Vanovitch

Design Kai-Olaf Hesse

Color Management Hannes Wanderer

Printed in Germany by Wanderer

© Text: Anna-Carola Krausse

© Illustrations: DACS, London 2017

© Photographs: Fotostudio Bartsch, Berlin (p. 33); Geoffrey Hodgdon Photography (cover); Matthew Hollow Photography (pp. 33, 37, 45); Michelangelo Miskulin, Kalmar (pp. 10, 23, 25).

All other photographs: Agnews, London; Laserstein-Archiv Krausse, Berlin.

Cover illustration

In my studio (detail), 1928

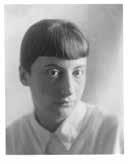

Frontispiece

Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski: Lotte Laserstein in front of ‘Evening over Potsdam’ (1930), Lotte-Laserstein-Archiv, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin

Illustration page 2: Lady in blue with hat and veil, c. 1939

Photographs in biography

Lotte-Laserstein-Archiv, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, and private collection, Berlin

Back cover

Rear nude with raised arms, 1930s

First Edition 2017 © 2017 Agnews, London

6 St. James’s Place | London | SW1A 1NP

www.agnewsgallery.com