Kollwitz Uno Käthe

by Annette Seeler

Annette Seeler, Dr., studied art history, general and comparative literature, and philosophy in Munich and Berlin.

From 1989-1998, she was the main research assistant at the Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Berlin. Since then she has worked as a freelance curator, author and expert on Käthe Kollwitz on behalf of museums and the art trade in Germany, France, Great Britain, Ireland, Austria, Switzerland and the USA. She has received commissions from the Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Cologne; the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart; the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin; Christie’s and Sotheby’s (mainly in London and New York); and the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles; among others.

She is the author of numerous articles in magazines, catalogues and anthologies (focusing particularly on classical modernism), and she has written and edited a number of monographs, including the catalogue raisonné of Käthe Kollwitz’ sculptures (2016, the latest edition as a database is in preparation). She is currently establishing a research archive for the Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Cologne, and she is guest curator for the Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Berlin.

Kathe Kollwitz 1867 Königsberg – Moritzburg 1945

Black chalk on laid paper, 1909

Signed and dated lower left Kollwitz 09

Sheet 65 x 46.5 cm

Reference Nagel 531

Literature Artur Fürst, Das Reich der Kraft, Berlin 1912, p. 62 (ill.); Licht und Schatten, Year 4, 1914, no. 21 (ill.); Jahresweiser durch alte und neue Kunst, Berlin 1961, no. 62 (ill.)

Provenance Adolfine Erna Theodore, Bremen; Hauswedell & Nolte, Hamburg, Auction 10, 1971, lot 1101 (titled Sitzende); Günter Gaus, Berlin (acquired at the sale); Private collection, United Kingdom

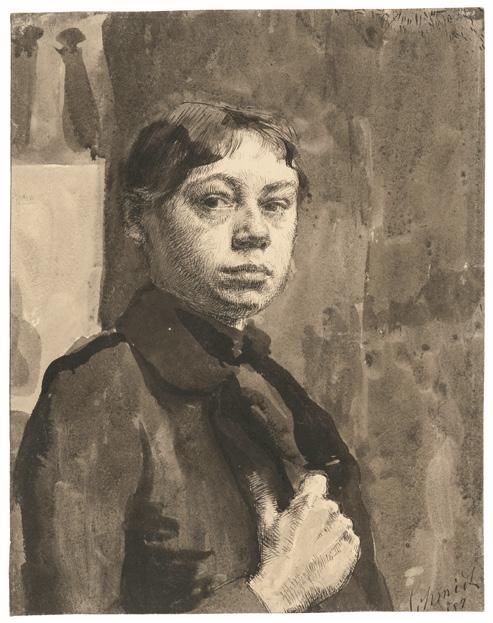

Fig. 1: Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), Self-Portrait, 1889, pen and black ink and brush and sepia on drawing cardboard, 312 x 244 mm, NT 12, Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln, Inv. Nr.: 70200/00013

We fade in: It is March 5, 1917, in Berlin, Germany. The graphic artist and sculptor Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) is standing in her studio looking through portfolios of drawings that she has created since her youth. Kollwitz is preparing for a large solo retrospective, celebrating her 50th birthday, that the art dealer Paul Cassirer organized from April to May 1917. This exhibition would mark the first time that the artist’s drawings and studies were shown extensively in public. That evening in her diary, Kollwitz recalled selecting possible works to exhibit, prompting her to reflect on her development as an artist:

“When looking through my drawings for the exhibition, I also found my very old ones from 14 to 17 years old. I still find it very difficult to cope with my old things. I find that very explainable. One overlooks one’s shortcomings at a glance and they are usually ones that are later pushed back but are still a danger. In my case, the narrative. My early drawings are almost all anecdotes. Everything that happens is drawn, things I’ve seen and things I’ve imagined. So even there, if you like, it’s a ‘dealing with life’.”1

Looking at the 1909 drawing Breakfast on the Stairs, the focus of this essay, one immediately sees that there is also a storyline in the background of this motif. Here, however, it is condensed into a snapshot. We can only understand it if we take a closer and deeper examination of the picture.

Who is Käthe Kollwitz? The note of self-criticism that we find in her journal entry quoted above is typical of her. From the outside, however, we must conclude: This artist is a phenomenon! Today, Kollwitz’s name echoes around the world and in the spring of 2024 alone, major solo shows of her work were presented at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. At the end of 2023, a survey show of the artist’s œuvre was organized at the Kunsthaus Zürich, and this winter a selection of her works will be shown at the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen. Yet unlike many, particularly female, artists whose well-deserved international fame came belatedly and posthumously, Kollwitz was in fact already recognized well outside Germany’s borders during her lifetime. Her prints were shown in Paris as early as 1905, a solo exhibition was presented in New York in 1912, and in the 1920s her reputation spread as far as the Soviet Union and even China.

Yes, she is a phenomenon (fig. 1). That she made her breakthrough in 1898, at the age of 31 in a male-dominated society, is amazing. It is even more astonishing when we realize that she received an inferior education in so-called “ladies’ schools”, first in Berlin (18961897) and then in Munich (1888-1890). Most art academies in Germany at the time were reserved exclusively for young men, and only them were taught to create history paintings, the most prestigious genre of art since the Renaissance. Women were further excluded from the artistic elite as a result of the male-dominated collegial networks created by these same academies. Towards the end of the 19th century, however, general upheaval in the art world was to make way for the avant-garde, the spearhead of what is now known as classical modernism. Traditional academic ideas were increasingly questioned, and conventional training was no longer necessarily a requisite for success.

It was fitting that the young Käthe Schmidt from Königsberg in East Prussia (now Kaliningrad), who had been married to Karl Kollwitz and had been living in Berlin since 1891, was largely self-taught, acquiring on her own many of the skills she would later use to great effect. She did undertake limited studies under more experienced artists. As a child she received lessons in drawing, and she was later introduced to rudimentary printmaking and sculpting practices. The latter took place in 1904 at the Académie Julian in Paris. Yet throughout her life, Kollwitz primarily followed the motto of learning by doing.

When Kollwitz set out as an independent artist in Königsberg in 1890 and in Berlin from 1891, she was only moderately equipped to do so. At this point, she was turning her back on painting to focus her efforts exclusively on printmaking. This was a courageous decision, given that printmaking had long been thought of as merely a reproductive technique, down on the lower rungs of the academic hierarchy. At the time, printmaking

was only just beginning to regain its status as a relevant means of independent expression, thanks in part to the pioneering graphic work of Max Klinger (1857-1920).

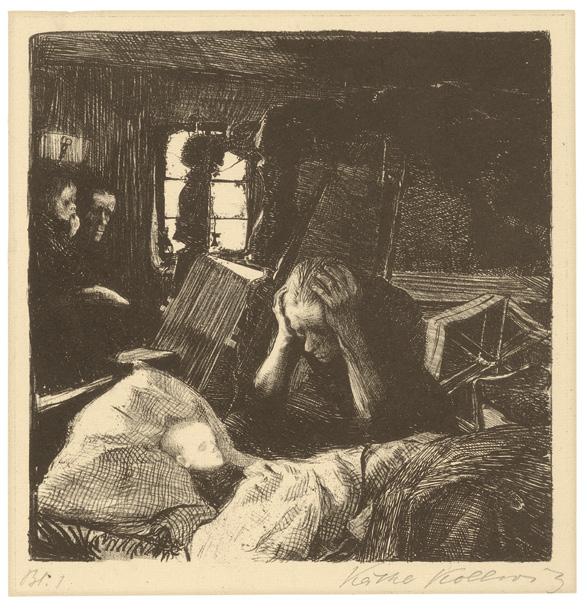

Kollwitz was thus at the forefront of a movement that had something new in mind. She was first rewarded for this grit and her tireless exercises in this material when she presented her print cycle Ein Weberaufstand ( A Weavers Revolt, 1893-1897) at the major Berlin art exhibition in 1898 (fig. 2). It was probably her masterly technique, which won Kollwitz the immediate recognition of her male colleagues. Yet the politically revolutionary subject matter, which caused a stir in the German Empire, as well as her furious visual language, also played a part in attracting attention to the work. In 1941, she wrote in her autobiographical text In Retrospect : “From then on, at one blow, I was counted among the foremost artists of the country.”2

In 1901, Kollwitz became a member of the Berlin Secession, the artistic movement founded in 1898, in whose exhibitions she had participated from the very beginning. Within this community of opponents to Wilhelmine cultural policy, Kollwitz realized that a more intensive engagement with the French avant-garde would benefit her pictorial vision. She paid a short visit to Paris in 1901 and traveled to the metropolis on the Seine again in 1904 for a two-month stay. There, Kollwitz became more familiar with the work of the Nabis, among others, and she bought a drawing by a young Pablo Picasso.

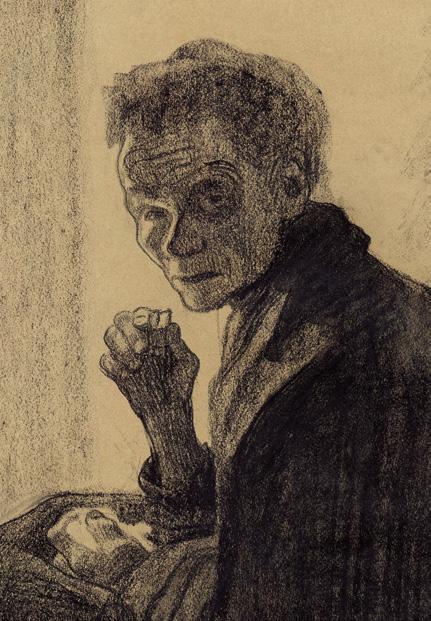

One may identify three main developments in Kollwitz’s works on paper that arose from these new influences. Firstly, the artist introduced colour as an important graphic element, which she then experimented with extensively until around 1910. These experiments also included the incorporation of coloured paper into her designs. Secondly, an antiillusionistic tendency in her works became stronger, as she instead sought to emphasize the process of handcraft production. This went hand in hand with a reduction of narrative details and a concentration on the expressive possibilities of the human body (fig. 3). Certainly, this reflects her new experience of sculptural shaping as well. Finally, Kollwitz’s time in Paris prompted her to take on new subjects in her art. After completing her etching cycle Peasants’ War in 1908, which had been commissioned by the Association for Historical Art in 1904, she withdrew from depicting such literary and historical subject matter and turned instead to the quotidian events that surrounded her in the large city. All these characteristics of Kollwitz’s modernism can be identified in her drawing Breakfast on the Stairs, which we will discuss in depth below.

Between 1908 and 1910, the artist published a total of 14 works in the satirical magazine Simplicissimus, including the suite of six Pictures of Misery. As she wrote to a friend, this work reflecting “the many quiet and loud tragedies of city life” was extraordinary

Fig. 2: Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), Need, Sheet 1 of the cycle “A Weawers' Revolt”, 1893-1897, crayon, and pen litograph with scratch technique, 154 x 153 mm, Kn 33 A III a., Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln, Inv. Nr.: 70300/84005

Fig. 3: Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), The Ploughmen, sheet 1 of the cycle “Peasant War”, 1907, line and etching, drypoint, aquatint, reservage, sandpaper, needle bundle and soft ground with imprint of Ziegler's transfer paper, 315 x 454 mm Kn 99 VIII b, Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln, Inv. Nr.: 70300/93007

4: Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), Woman squatting on the stairs, 1909, black crayon, heightened in whiteon brownish paper, 483 x 629 mm, NT 532, Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln, Inv. no.: 70200/19002

dear to her, not least because she had to express her message for this commissioner in a popular way without compromising on artistic quality.3

Though Kollwitz’s socially critical depictions for the satirical Simplicissimus are of a piece with her entire œuvre, these sheets are an exception in that they are among the very few drawings that she produced as autonomous artworks. Typically, the artist used the medium merely as a form of study — to prepare the compositions of her prints and the forms of her sculptures, the distribution of light and shadow, the posture and facial expressions of the figures, etc.

The present sheet, for which a preparatory study exists (fig. 4), was executed during the same creative period as the Simplicissimus works and is also an autonomous drawing. Kollwitz dated the sheet “09” while she signed it, indicating that she did so immediately after executing her last stroke. It is exceptional to find this among Kollwitz’s drawings, which suggests that she felt a special pride in the piece upon its completion (fig. 5). The subject itself suggests a further connection with a planned work for Simplicissimus Here Kollwitz depicts an emaciated, prematurely aged woman, wrapped in a dark shawl and sitting on a stair landing with her back turned to us. Her left hand holds a lightcoloured bundle in her lap, while her right hand brings a small piece of bread towards her mouth. The woman turns towards us in three-quarter profile, facing upwards, as if we, descending the stairs, had just interrupted her small meal (fig. 6).

Kollwitz uses lighting to create the suggestion of the scene as a sudden, unpleasant discovery. A window illuminates the dark figure from the top left in dramatic chiaroscuro, as if she had been struck by an unexpected spotlight at the very moment that we find her in this dim, hidden corner. We are, so to speak, witnessing a negatively charged illumination that is also voyeuristic in character, like looking through a keyhole. Just as the light here is associated with a sense of revelation, insight, even enlightenment, there is a meaningful tension that is held between the top and bottom of the picture. Because the figure is a little bellow our view, we also figuratively look down on her. Indeed, the balance of power is clearly distributed; we, the viewers, are in a superior position, from which the woman is subordinate to us. It is as if our eyes are being opened and we are being granted an insight into an otherwise hidden existence for the first time.

There are other evocative aspects to this composition. Kollwitz places the figure against the sheet’s right edge, suggesting her marginal existence. Further, that she succumbs to taking up temporary residence in such a draughty passageway illustrates her rootlessness in this world. Whether the drawing’s subject is a maid eating a quick, meagre breakfast between two cleaning jobs, or a homeless person who has begged for a few crumbs at the doors, does not play a decisive role in our understanding of the scene. What is certain, however, is that we are looking at an urban tragedy of a piece with those which Kollwitz wanted to present to the large readership of Simplicissmus, but which in this case failed to happen

for unknown reasons. This is no grand tragedy that loudly demands the Aristotelian effects of fear and pity from its viewer. Rather, it is a quiet scene whose message is found between the lines, as it were, and which even holds a measure of picturesque tranquility. The surely intended social criticism is presented here rather subtly and not quite clearly, and perhaps that was the reason why the artist ultimately did not publish the work in the satirical magazine.

We explained above that we can infer, from the way the artist apparently signed and dated this drawing immediately after its completion, the pride with which she regarded her achievement. As becomes obvious when we take a closer look at the way in which she put her motif on paper, Kollwitz had every reason to be pleased with the work. For starters, one is immediately impressed by the confidence with which she put her figure on the page. There are only a few corrected strokes of black chalk, especially around the knees and lower legs, which are wrapped in a skirt, and on the right shoulder. But Kollwitz shows no mistakes in capturing the head, the face and the raised hand. Here even the artist’s first lines were already in the right place.

It is also remarkable how economically Kollwitz uses her chosen materials. The colour of the paper plays an important role. Having recently been carefully restored to its original hue, the paper support now reappears as a meaningful element of Kollwitz’s design. The bright gray shade, now only slightly yellowed, is an active part in the composition, appearing as light itself, or as illuminated surfaces, as we see in the bundle in the left hand, which could be a handkerchief or a piece of sandwich paper. There the light of the sheet gathers, appearing brighter, in the context of its dark surroundings, than elsewhere in the composition. In this way, Kollwitz directs our attention to the object that the woman is carefully holding in her lap as her only treasure. In some places, the artist subtly demonstrates her technical mastery by smudging the chalk with her fingers, allowing us to literally experience her handwriting (fig. 7). At the same time, Kollwitz gives us a gentle hint that we should feel touched by the scene depicted in a figurative sense.

Käthe Kollwitz herself was not the only one to appreciate this drawing, as a glance at its provenance shows. While the work was probably still owned by the artist in 1914, when it appeared in the magazine Licht und Schatten 4, it probably was in a private collection in Bremen, Germany, before 1920. The direct or indirect mediator of this translocation must have been the reform pedagogue Gustav Adolf Wyneken (1895-1964), whose name first appears in the artist’s diaries in 1914 and who became known to her through his involvement in the youth movement via her sons, Hans and Peter.5 The drawing ended up

with Wyneken’s sister Adolfine Erna Theodore (1889-1954) and her husband, a Bremen entrepreneur who sold it at the Hamburg auction house Hauswedell & Nolte in 1971.

As a result, Kollwitz’s drawing was acquired by an extremely important personality in post-war German history: the prominent journalist and politician Günter Gaus 6 (1929-2004) who was appointed by Willy Brandt as the first Permanent Representative of the Federal Republic of Germany in the German Democratic Republic from 1974 to 1981. Gaus’s decision to acquire Breakfast on the Stairs in 1971 demonstrates not only his open-mindedness towards art, but also his interest in social issues. In this sense, he was one of the few persons in West Germany at the time to cultivate close relationships with artists in the GDR. Although nothing has yet been published about his art collection, it can be assumed that this excellent drawing by Kollwitz hung in the Gaus household in the illustrious company of works by contemporary East German artists until his death.7

1. Cf. Kollwitz 2012, p. 308 (diary entry from March 5, 1917).

2. The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz , edited by Hans Kollwitz and translated by Richard and Clara Winston, Chicago, Henry Regnery Compagny, 1955, p. 37.

3. Cf. Bonus-Jeep 1948, p. 102.

4. The title means “Light and Shadow” (4th year, 1914, no. 21), Our drawing was published in this magazine under the title Mittagsmahl [Lunch].

5. Cf. the diary entry from April 1914, in: Kollwitz 2012, p. 144.

6. This information is taken from Lucia Seiß, Zentralarchiv für deutsche und internationale Kunstmarkforschung, Universität zu Köln (ZADIK), in an email to the author dated September 26, 2024. The ZADIK contains the auction house’s business papers (A 100 Hauswedell & Nolte Auktionen, Hamburg).

7. After Gaus’s death, the drawing apparently remained in his family until his daughter’s death in 2021, as the auction at Kettererkunst, Munich, in 2022 stated that the sheet had been in the possession of a single family since 1971. It is unclear why the auction catalogue located this family in southern Germany or Bavaria, as the Gaus couple lived in a house in Reinbek near Hamburg from 1969 to 2004. It is possible, however, that the heirs of Gaus’ daughter (who was also a famous journalist), who consigned the drawing to KettererKunst, lived in southern Germany.

Abbreviated literature cited

Bonus-Jeep, 1948

Beate Bonus-Jeep, 60 Jahre Freundschaft mit Käthe Kollwitz (60 years of friendship with Käthe Kollwitz), Boppard: Karl Rauch Verlag, 1948.

Kollwitz, 2012

Käthe Kollwitz, Die Tagebücher, 1908-1943 (The Diaries, 1908-1943), edited by Jutta Bohnke-Kollwitz, München: btb Verlag, 2012 (1st edition: Berlin, Siedler, 1989).

Author

Annette Seeler

Design

Tia Džamonja

Editing

Eric Gillis, Catherine Gimonnet, Noémie Goldman & Andrew Shea

Scans & Photographs

Jérôme Allard – Numérisart; Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln

Special thanks to Valérie Quelen

© Agnews – November 2024