Highlights

1830 1915 Selection of Ten Works

June 2024

Art is not just a decoration of life, but a source of inspiration and guidance for our own journey.

Henry Moore

If the world were clear, art wouldn’t be.

Albert Camus

Dear friends,

This year 2024 definitely hasn’t looked like 2023, let alone 2022! The world is constantly growing, adapting, tearing itself apart, and reconstituting itself anew. Yet art never ceases to inspire us, and it does even more: it makes us believe in a better world; it nourishes us (a gargantuan feast); and at the same time it transports us far away, into a realm of perfection and reverie. We don’t know of many other things that have this power, except perhaps love — love of ourselves and of others.

How fascinating it is to look upon these artworks, imbued as they are with such virtuosity and depth! It’s truly unbelievable. So, you can imagine how pleased we’ve been to encounter and collect this trove of treasures through our wanderings across Europe and in private collections, and to offer them to you here. Our only dream is for these works to change hands — to find a new home, new viewers, a new audience. The works are meant to be seen, admired, breathed in, almost eaten! And it’s in our body — under our skin — that we feel them too. There’s no excuse not to grab on. Love is calling us.

Happy discoveries!

Eric & Noémie

1 Jean-Antoine Théodore Gudin

1802 Paris – Boulogne-sur-Seine 1880

Fishing Boat at Sunset

Oil on paper laid down on panel, ca. 1830-1835

Signed lower right T Gudin

Sheet 232 x 310 mm

Provenance Private collection, Germany

The present work is a delightful example of Théodore Gudin’s famous seascapes, combining an elegant and delicate palette with the chiaroscuro and drama of a stormy atmosphere. Gudin was one of the most talented maritime painters of the 19th century. He studied with Ann-Louis Girodet and AntoineJean Gros, but very soon he grew fond of the romantic masters Delacroix and Gericault.1 His sea subjects — shipwrecks, views of harbors, etc. — were immediately noticed, starting at the 1822 Salon, where he exhibited five works. In 1824 he won the golden medal in the same Salon, and his fame only grew from there. He was quickly the protégé of the Duc d’Orleans, the future King Louis Philippe, for whom he made later a maritime series for the Galerie Historique of Versailles (1844). He was also close to the painter Horace Vernet (who taught Gudin’s brother), whom Théodore met in Rome in 1832.

Gudin’s œuvre is expansive, though it concentrates in the classic genre of sea painting. Beside these highly developed works, however, he made a few studies, such

as the present example, that seem more related to the practice of plein-air sketching. These display a certain maturation in their ability to convey an aesthetic emotion not through human subjects, but through their close attention to atmospheres, weather events, and specific times of day. In this delicate oil, Delacroix’s influence is particularly evident, reminiscent of the French Romantic’s pastels depicting a crepuscular sunset light. The influence of Cozens and Constable may also be detected. Gudin, however, differs from these models in his use of more controlled brushstrokes, which seem to suggest the artist’s search for peace and harmony, even in the midst of an oncoming tempest.

1. See: Jean-Antoine Théodore Gudin & Edmond Béraud, Souvenirs du Baron Gudin, Peintre de la marine (1820-1870), Edition, Plon, Paris, 1921.

2 Alexander Munro 1825 Inverness – Cannes 1871

Portrait of Pauline, Lady Trevelyan (1816-1866)

Original plaster with gilt border, framed in mahogany veneer frame, ca. 1855-1856

Plaster 48 cm, diameter

Literature Benedict Read and Joanna Barnes, Pre-Raphaelite Sculpture: Nature and Imagination in British Sculpture, 1848-1914, 1991, p. 64 (marble ill.)

Provenance Thence by descent; Raleigh Trevelyan, London; Private collection, England

A rare and unique original plaster cast, this work served as the preparatory model for the marble medallion depicting Lady Trevelyan that is still in its original place today: in the central hall of Northumberland’s Wallington House. Lady Trevelyan, the woman elegantly portrayed here by Munro, is a key personality of the Pre-Raphaelite circle. She was the wife of Sir Walter Calverley Trevelyan, 6th Baronet, a wealthy and intellectually minded aristocrat. Trevelyan and his wife shared a common passion for geology and art. An artist herself, Lady Trevelyan made Wallington Hall, her husband’s property, the centre of High Victorian cultural life. Amongst friend who visited her country home were the art critic John Ruskin, the poet Algernon Swinburn, the historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, and the various members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Lady Trevelyan also became one of the earliest northern English patrons of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). All these personalities and artists have left their mark within Wallington Hall, and crucial among these creative contributions is Munro’s marble medallion.

Munro was closely himself associated with the PreRaphaelite movement. He was a close friend of Thomas Woolner, one of the founding members of the Brotherhood, as well as its only sculptor. Munro’s œuvre consists of portraits, busts, monuments, historical statues, and works of imagination, and he developed

a unique decorative style. Munro was a close friend of Gabriel Rossetti, and his most famous work, Paolo and Francesca, was inspired by Rossetti’s illustrations of scenes from Canto V of Dante Alighieri’s Inferno William Michael Rossetti, the poet and son of Gabriel, wrote this about the two artists’ relationship: “ Gabriel never had a more admiring or attached friend than Munro.”1 Paolo and Francesca is an exemplar of the PreRaphaelite movement, and its original plaster version is also currently on display in Wallington Hall.

Above all, Munro was an excellent portraitist. The present medallion in high relief depicts the face of Lady Trevelyan with formal simplicity. Her hair is tied in a low bun; her lips betray a discreet smile. Munro’s sculpture is spare and clean of clutter, and the deep relief of Lady Trevelyan’s head casts strong shadows that vividly emphasize her features. There is a superbly intimate quality to this work, achieved first by its immaculate technique, and second by a touching detail: Lady Trevelyan herself wears a medallion with the portrait of her husband around her neck.

With this work, made by a master sculptor of his day, we are transported to the fascinating world of the PreRaphaelites.

1. William Michael Rossetti, The Diary of W. M. Rossetti: 18701873, Odile Bornand ed., 1977, p. 39.

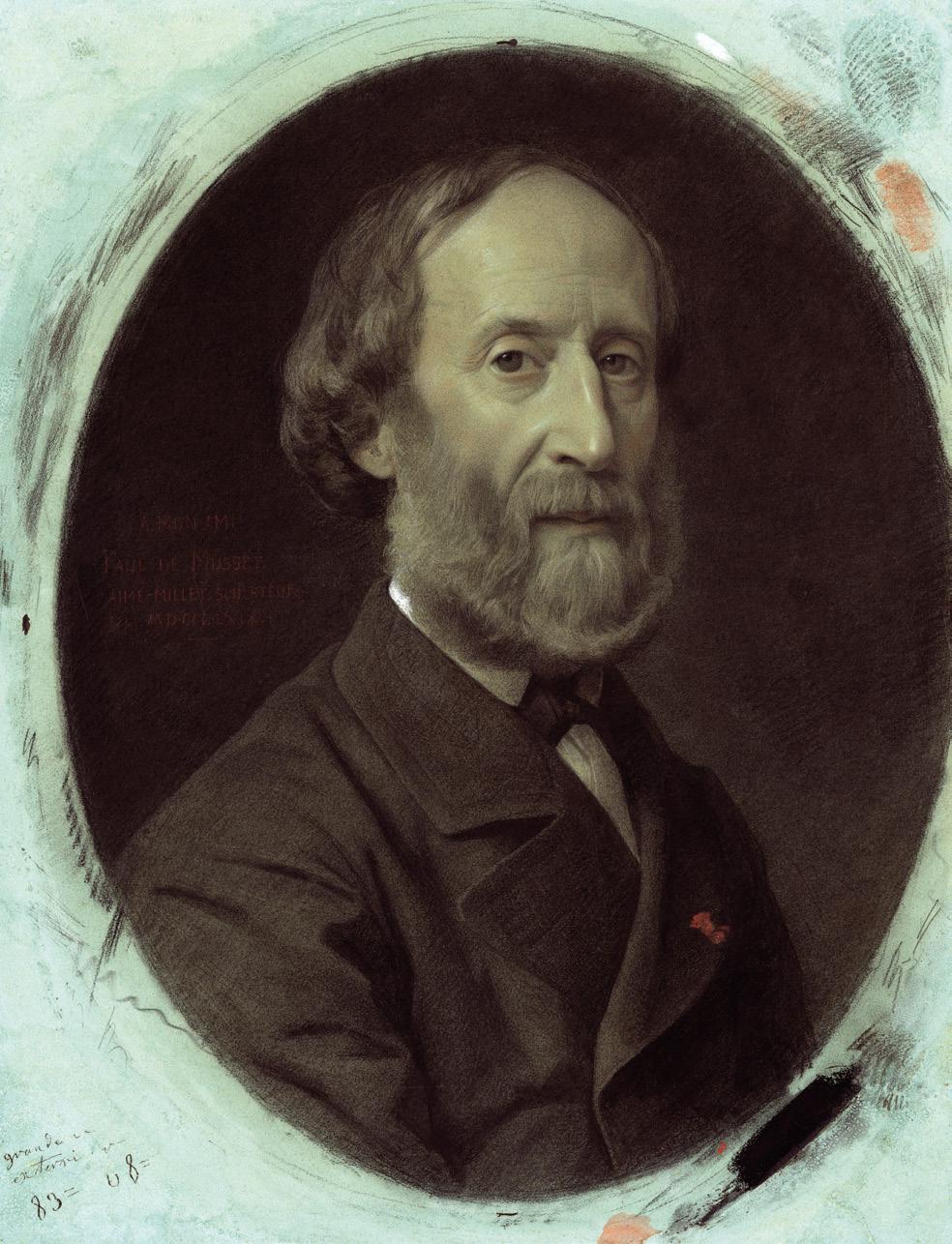

3 Aimé Millet

1819 – Paris – 1891

Portrait of Paul de Musset

Charcoal and pastel on blue paper, 1869

Signed and dated on the left side A mona mi / Paul de Musset / Aimé Millet Sculpteur / MDCCCLXIX

Size 560 x 437 mm

Exhibition Paris, Palais des Champs Elysées, Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture, Architecture, gravure et lithographie des artistes vivants exposés au Palais des Champs-Elysées le 1er mai 1868, 1868, cat.3134, p.398

Literature Frank Lestringant, Alfred de Musset, Paris, 1999 (ill.)

Provenance Private collection, France

The present work is an exceptional pastel by the French sculptor Aimé Millet, portraying the writer Paul de Musset (1804-1880). This portrait displays Millet’s fascinating technique: the subtle range of colours used to represent this elegant man’s skin, the texture of his beard, and the overall intensity of his glance and visage. An older brother of the poet Alfred de Musset, Paul is known today as the writer of his famous sibling’s biography, among other texts related to Alfred. Paul, however, had a strong personality: he was more social than his brother, frequented many Salons, and had an active and respected position in his cultural milieu. He was portrayed by various artists, including such as Gustave Richard, whose portrait of Paul is at the Orsay Museum, and he was photographed several times by Nadar. In the present work, as in many of his other portraits, Paul bears a red-ribbon on his vest: the decoration of Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur.

This pastel is a fine demonstration of Aimé Millet’s skills as a draftsman. Celebrated primarily as a sculptor, the artist excelled with pastel, which he often used to portray his friends. Henri Dumesnil, in his book entitled Aimé Millet, souvenirs intimes, writes: “Millet,

de temps à autre re-prenait le crayon, — pour ses amis — c’est ainsi qu’il a fait le portrait de P. de Musset, en 1868, et ceux de MM. de Marcère et Duclerc, anciens ministres. Ces derniers ont été exposés au Cercle Artistique et Littéraire, dont il faisait partie, au mois de février 1879”1. That Millet presented these portraits publicly at exhibitions means that he considered them to be an important aspect of his œuvre.

Dumesnil also writes about the social circle around the artist.2 Aimé and Paul were part of “Les Amis du Vendredi”: a group of artists and writers who organized a dinner every Friday for 25 years. Among Les Amis du Vendredi were famous personalities such as Barye, Corot, Cabanel, Carolus-Duran, and Viollet le Duc. This powerful portrait, then, gives testament not only to this artistic milieu, but also to the relationships made between artists and writers of the time, to the talent of a sculptor, and to the personality of a man who has been eclipsed in history by his celebrated brother.

1. Henri Dumesnil, Aimé Millet, souvenirs intimes, Paris, 1891, p.43.

2. Ibid., p.22.

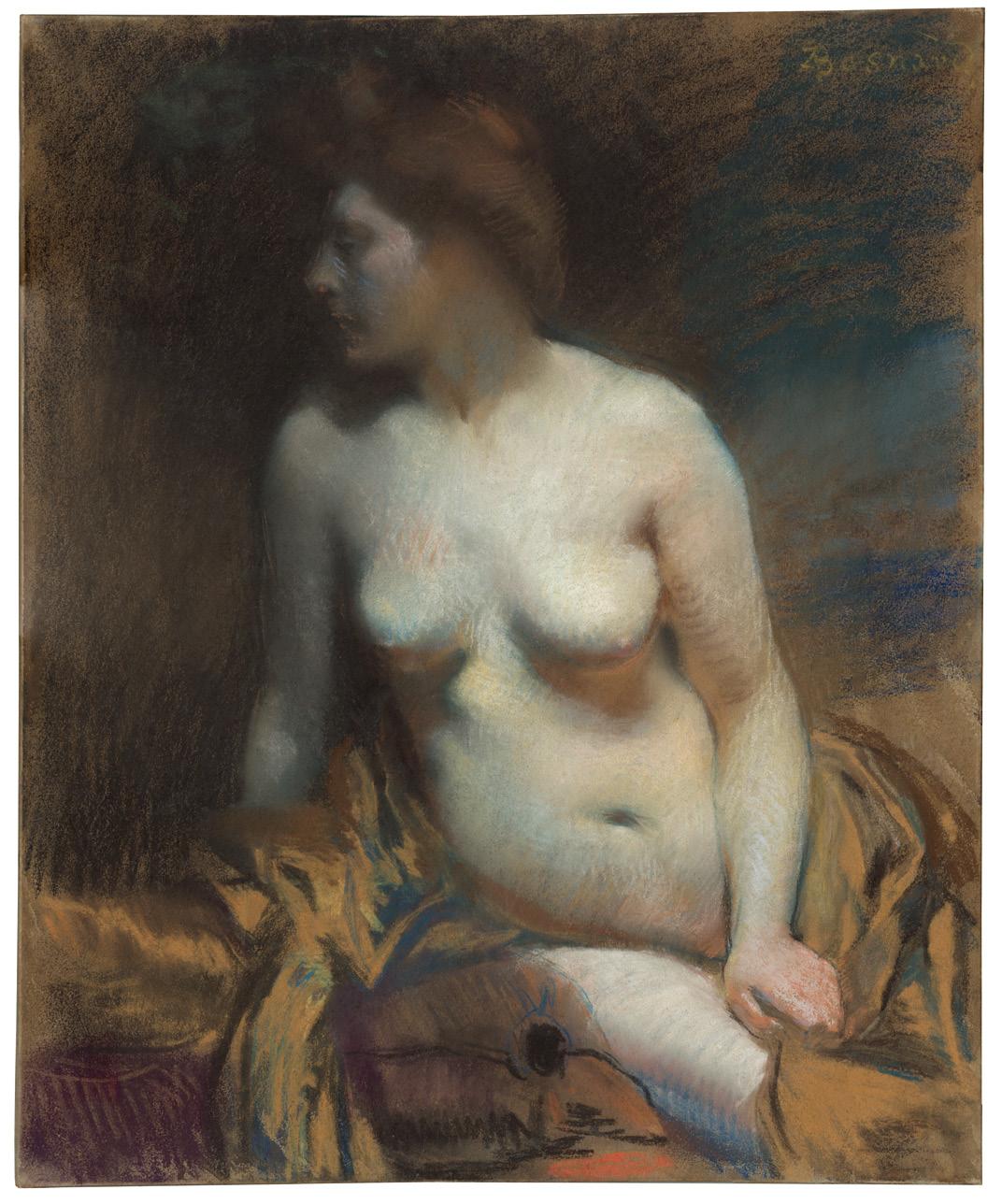

4 Albert

Besnard

1849 – Paris – 1934

Seated Female Nude

Pastel on wove paper laid down on canvas, ca. 1890

Signed upper right ABesnard

Sheet 503 x 604 mm

Provenance Sir Robert Abdy, London; Private collection, Paris

Albert Besnard was one of the great masters of pastel at the turn of the 20th century, and this superb work demonstrates why. Here Besnard captures a fleeting moment of intimacy, depicting the slight twist of his subject’s body in a perfectly controlled evolution of tones, from shadow to light. This nude bears the fruit of Besnard’s extensive research into tonal and chromatic gradations that, together with contour linework, cohere into sensitive vignettes. One finds a similarly expert manipulation of light to evoke texture in two other pastels by the artist, kept at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris: Femme nue se chauffant (1886), and Femme à demi-nue dans l’eau dite Baigneuse (ca. 1890-1900). As the artist himself once put it, “The flesh appears different from the tissues through the more intimate fusion of light rays.”1

These flawless pieces are evidence of Besnard’s mastery of the pastel medium. Their hazy, blurred values work in counterpoint to the small-scale cross-hatchings that provide both definition and light, as if paying homage to the pastel artists of the 18th century. The present pastel also owes a debt to Besnard’s contemporary Edgar Degas, particularly in its arrangement of tones and colours.

In approaching this subject, a favourite of the artist, Besnard seems to convey the enigma of women by exalting their beauty. The education he received from his mother must have cultivated his sensitivity towards the feminine, and the French writer Georges Lecomte attests to Besnard’s “sense of tense, vibrant, distinguished, languorous femininity, possessed by himself.”2 He painted this subject as well, as in the Nymphe endormie (Le Nu aux lapins), before 1911, in the Musée d’Arts de Nantes, and Nu, 1916, in the Musée d’Orsay. For Besnard, however, it was the medium of pastel that liberated his imagination, allowing him to follow his inspiration with spontaneous, immediate gestures. He was a virtuoso in rendering the sensuality of naked skin embellished by light, and he exhibited his works from the very beginning of the Société des Pastellistes, of which he was president until 1913.

1. Chantal Beauvalot, Albert Besnard (1849-1934) Modernités Belle Époque, Paris, 2016, p. 39.

2. Georges Lecomte, Albert Besnard , Paris, 1925, p. 48.

5 Albert Trachsel 1863 Nidau – Geneva 1929

The Sun

Watercolour and gouache on wove paper, ca. 1890-1895

Signed lower left A. Trachsel

Sheet 510 x 420 mm

Provenance Private collection, Switzerland

The present sheet is one of the most beautiful works by the Swiss artist Albert Trachsel we have ever seen. As outlined below, this Symbolist watercolour and gouache painting dated from the time Trachsel was in Paris in the 1890s, when he first painted symbolist figures within a space divided by rays of bright, ethereal colours, and when he created an œuvre of symbolist landscapes — the so-called Paysages de Rêve. Symbolist works by the artist are extremely rare: not a single example has come up at auction in the past thirty years. Most were held in a small number of important private collections in Solothurn, Switzerland, such as those of Oscar Miller, Josef Müller, and his sister, Gertrud Dübi-Müller, before going to public institutions such as the Kunstmuseum of Solothurn and Geneva’s Musée Barbier-Mueller. The rarity of these works in the private marketplace underlines the importance of the painting we are now offering.

Albert Trachsel, architect, painter, and poet, led perhaps one of the most captivating lives in the history of Swiss culture around the turn of the 20th century. A first pivotal step on his path was his move to Paris in 1889, and his involvement there in Symbolist circles such as that of the literary journal La Plume, or in literary circles such as that of the Mercure de France. He assiduously cultivated acquaintances with Eugène Carrière, Auguste Rodin, Stéphane Mallarmé, Stuart Merrill, Charles Verlaine, Jean Moréas, Charles Morice, and Edouard Dubus, and he even befriended Paul Gauguin. In 1892, he exhibited at the first Salon de la Rose-Croix, where he showed thirty-one works alongside other important artists, including Trachsel’s compatriots Hodler, Vallotton, Schwabe, and Grasset. In 1893, Stuart Merrill published an article about Trachsel in La Plume

The present work’s mysterious air evokes the spirit of Odilon Redon, a painter whom Trachsel certainly knew among the artists of Gauguin’s orbit. Yet Trachsel never mentions Redon in his writings, although he does make

reference to Eugène Carrière, whom he describes as a brilliant artist. In this work, Trachsel combines light colours and clean-cut figures typical of the Jugendstil. Its ethereal, magical forms also bear a relationship to the PreRaphaelites, as well as, via Gustave Moreau, to the Swiss artist Carlos Schwabe and the Dutch painter Jan Toorop, who also showed at the first Salon de la Rose-Croix.

Alongside his visionary architectural drawings and his Paysages de Rêve landscapes, Trachsel made a very small body of symbolist figurative work, comprising around fifteen examples plus a small notebook, dating from the 1890s and circa 1902-1905. These works were almost all made on paper; there are few oils on canvas. As the Swiss historian Hans A. Lüthy speculates, this may have been in part due to his close friendship with the elder painter Ferdinand Hodler, whose superior mastery of oil painting may have intimidated Trachsel.

Amazingly, in 1905, Trachsel exhibited at the Galerie Serrurier in Paris along with Pablo Picasso and Auguste Gérardin. We cannot help but see Picasso’s influence in the most powerful face we’ve ever seen in Trachsel’s work. We have given this composition the title The Sun, as other drawings from this period seem to examine celestial phenomena, bearing titles such as Lightning, Moonrise, and Shooting Star. This composition may also relate to a set of illustrations called Poème that Trachsel planned in 1885-1890. Poème was to comprise three volumes, Fêtes Réelles, Le Chant de l’Océan, and Apparitions, that would depict Trachsel’s personal vision of a utopian universe — a dreamlike world of images, events, and atmospheres drawn from the cosmos and nature. Ultimately, only the first of these series, Fêtes Réelles, was published (in 1897); Trachsel’s other compositions for the project never saw the light of day in album form. Nevertheless, over the ensuing years Trachsel periodically produced standalone artworks based on his initial ideas for the Poème — including the present, glorious example.

6

Armand Seguin 1869 Paris – Châteauneuf-du-Faou 1903

On the Riverbank in Brittany

Watercolour on sketch paper, ca. 1892-1894

Signed lower left A.S.

Sheet 200 x 265 mm

Provenance Paul Sérusier, Châteauneuf-du-Faou; Henriette Boutaric, Paris; Private collection, France

This is a superb and extremely rare landscape watercolour by Armand Seguin, made during his stay between Pouldu and Pont-Avenin circa 1892-1894, and probably in the summer of 1894, when he was in this area with Paul Gauguin.

Seguin moved from Paris to Pont-Aven in spring 1892. That year, he met Émile Bernard and Auguste Renoir at the Hotel Julia in Pont-Aven; he also visited Maufra and Filiger at the inn of Marie Henry in Le Pouldu. There he composed the first landscapes of his œuvre, in painting and charcoal, but mostly in etching (there are seven examples in this medium recorded by Richard Field). This present composition could be dated to this year. Yet in the summer of 1894, Gauguin also appears to have twice depicted what seems to be the same place in Brittany, in a monotype (Les Chaumières, Field 27) and a painting (The David Mill, Wildenstein 528). Seguin and Gauguin spent much time together during this summer.

The present composition is remarkable for its strong contours and linear sensibility combined with its elaborate and delightful use of colours. Seguin’s

drawings are extremely rare; only one other landscape drawing from the same period, in pencil and charcoal, has been recorded.

It is worth mentioning this work’s interesting provenance. The drawing, unrecorded in the literature, comes from the artist Paul Sérusier, whom Seguin met in 1892 in Brittany, probably at Marie Henry inn. In June 1903, overwhelmed by disease and poverty, Seguin was taken in by Sérusier at Châteauneuf-duFaou, where he died in December of the same year. Henriette Boutaric was the best friend of Sérusier’s wife, Marguerite. In 1950, upon Marguerite’s death, Boutaric inherited the Sérusier atelier and its collection, whence the present sheet comes. Henriette spent the rest of her life promoting Sérusier’s work, as well as that of the Nabi and other Pont-Aven artists, until her death in the 1980s.