Dumas Uno Alexandre

Presented by Julie Anselmini

Professor of French Literature at the University of Caen Normandie, Julie Anselmini is one of the best specialists of Alexandre Dumas. A graduate of the Ecole Normale Supérieure, she holds a PhD and is an agrégé in French literature. Her research focuses on nineteenth century French literature, exploring the links between the press and literature, and between literature and criticism. She is the author of numerous books and articles on Alexandre Dumas, including Le Roman d’Alexandre Dumas père ou La Réinvention du merveilleux (2010) and L’écrivain critique au XIXe siècle : Dumas, Gautier, Barbey d’Aurevilly (2022). She has also recently published a new edition of Dumas’s last novel, Creation and Redemption (Gallimard, 2024). She is co-director of the Cahiers Alexandre Dumas and, together with Isabelle Safa, she has edited the Cahier Alexandre Dumas n° 45 : Alexandre Dumas en caricatures (2018).

Eugène Pierre François Giraud 1806 – Paris – 1881

Portrait of Alexandre Dumas (Père)

Pencil and watercolour on wove paper, 1836

Signed and dated lower right Giraud 1836

Annotated and signed lower left by Alexandre Dumas Elle me résistait, je l’ai assassinée ! Alex Dumas

Sheet 68 x 47 cm

Étienne Carjat 1828 Fareins – Paris 1906

Portrait of Alexandre Dumas

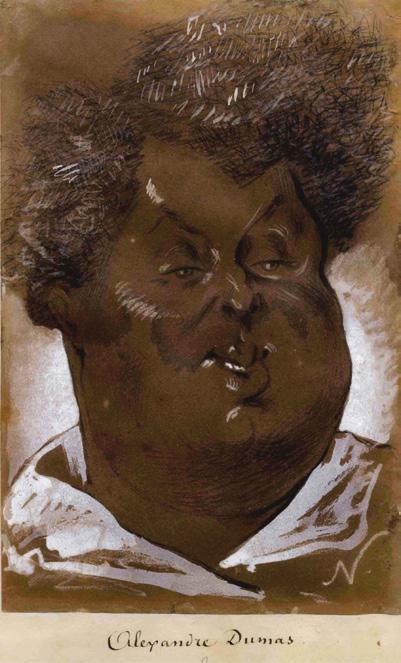

Charcoal and white chalk on paper, 1859

Signed lower right and dated ET.CARJAT. 1859

Caption lower center, signed by Joseph Méry Géant moral ou physique / prose ou vers chez lui tout plait / Hélas ! il n’est pas complet / il n’aime pas la musique !

Image 48.5 x 32 cm

Provenance Geneviève and Jean-Paul Kahn, Paris (major collection about Dumas)

In the nineteenth century, few public figures were targeted in newspapers and magazines as often as Alexandre Dumas.1 Journalists and caricaturists, whose professions were then flourishing as a result of the expanded press, found in Dumas an ideal subject, for several reasons. First, from the 1830s onwards, Dumas’s literary successes in the theatre, and then in narrative prose, made the French writer extraordinarily famous. By the peak of his celebrity in the 1840s, Dumas, alongside Balzac and others, was among the best-paid novelists of the time. And before being published as books, his novels were serialized in the “rez-de-chaussée” (bottom part of the page) of major daily newspapers (Le Journal des Débats, La Presse, and Le Siècle), introducing Dumas to a broad reading public – the same public amused by published caricatures – that was awed by his innate genius.

Readers were also astonished by Dumas’s remarkable prolixity, something that is partly explained by his practice of collaborating with co-authors on literary projects. Yet Dumas’s frequent publications were subject to equally frequent attacks in the press. These journalistic hatchet jobs, which took the form of both graphic caricature and written denunciation, were sometimes remarkably vicious.

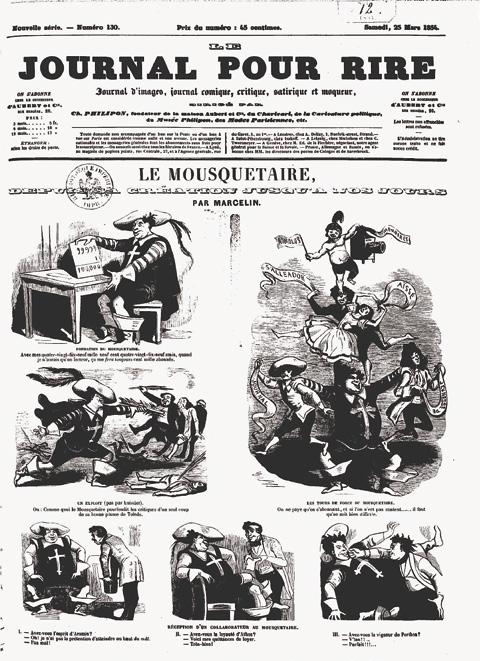

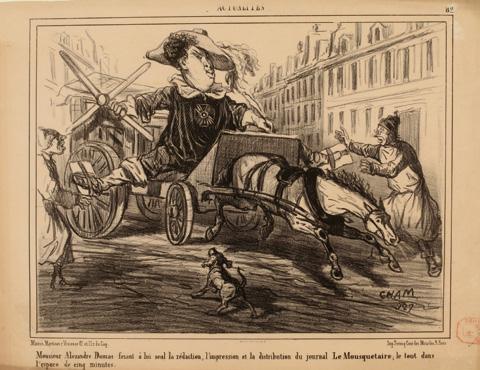

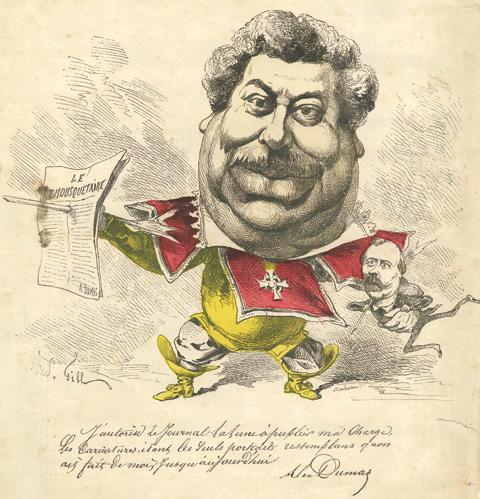

One notable example was Eugène de Mirecourt’s shamelessly racist pamphlet, Fabrique de romans : Maison Alexandre Dumas et compagnie (1845), which prompted Dumas to sue Mirecourt, successfully, for slander. In addition to making bigoted comments on Dumas’s appearance and character, Mirecourt claimed that Dumas actually didn’t write his works, but instead presided over a factory of ghostwriters that churned out his novels. Relatedly, many drawn caricatures of the period accuse Dumas of sacrificing his talent in favor of more lucrative opportunities as a writer – “selling out,” as it were, to create what C. A. Sainte-Beuve had already decried in 1839 as “industrial literature” (fig. 1)2 . In the Le Charivari of December 14, 1853, for example, the cartoonist known as “Cham” shows “Dumas single-handedly editing, printing and distributing Le Mousquetaire, all in the space of 5 minutes” (fig. 2). In Le Journal pour rire of March 25, 1854, Marcellin plays on the same motif (fig. 3), as does André Gill in La Lune, who alludes to a final “resurrection” of Le Mousquetaire in 1866 (fig. 4).

In addition to his literary fame, Dumas was a veritable “star” of his age: his turbulent personality, trials and tribulations, and flamboyant love affairs (such as with the young artist Adah Menken, which gave rise to a famous series of photographs by Liébert in 1867) were the talk of journalists and their cartoonist fellow travelers. Various picturesque

1. This introduction is based on our work for the Cahier Alexandre Dumas n° 45: Alexandre Dumas en caricatures, J. Anselmini et I. Safa (dir.), Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2018.

2. This is the title of an article written by Sainte-Beuve, published in September 1839 in La Revue des Deux-Mondes.

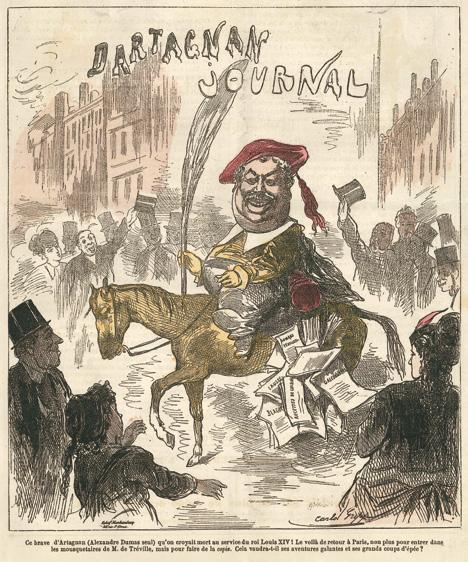

Fig. 1: Quillenbois, “Feuilletons, romans, drames et autres produits mécaniques”, Le Charivari, 25 December 1845, lithograph, cartoon 5.

Fig. 3: Marcellin, “Le Mousquetaire depuis sa création jusqu’à nos jours”, Le Journal pour rire, 25 March 1854, lithograph, cartoon 23.

Fig. 2: Cham, “Dumas faisant à lui seul la rédaction, l’impression et la distribution du Mousquetaire, le tout dans l’espace de 5 minutes”, Le Charivari, 14 December 1853, lithograph, cartoon 21.

Fig. 4: André Gill, “Le Mousquetaire”, La Lune, 2 December 1866, lithograph, cartoon 45

episodes from Dumas’s busy life inspired the latter. His journeys to Italy (made between the 1830s and the 1860s) and Russia (made in 1858–59) gave rise to veritable “comic strips” in the newspapers, and Cham depicted Dumas’s travels extensively in Le Charivari The 1847 opening of the Théâtre-Historique, Dumas’s 1853 return to the Paris stage after his exile in Brussels, and the founding of Dumas’s literary journal Le Mousquetaire that same year were similarly satirized. The turbulent fortunes of Le Mousquetaire, which ran until 1857, gave rise to graphic “gags” that spoofed its successive failures and revivals through comic repetition. Even the lectures Dumas gave between 1864 and 1866, in France and elsewhere in Europe, provoked two amusing cartoon series, in L’Univers illustré and Le Charivari respectively.

Dumas was clearly a colourful writer, but he was also a colourful character, and his unique physiognomy lent itself to graphic depictions that, no matter how distorted, pointed directly to their subject. The author’s tall stature, and his bush of untamed, frizzy hair, made him an irresistible target for caricaturists of the 1830s, 1840s, and onwards. In an era of endemic and blatant racism, these artists blithely exaggerated the African features of Dumas, the grandson of a white aristocrat and a black slave from Saint-Domingue, in ways that we now find repellent.3

The draughtsman and photographer Nadar (who had a great deal of sympathy for his writer friend) described him in this way (fig. 5):

Le teint bistré clair

Le nez fin

L’oreille microscopique

L’œil bleu

Les lèvres lippues à la mode de Mésopotamie, pleines de méandres, De cet ensemble, une irradiation magnétique, des effluves irrésistibles de bienveillance et de cordialité.

Light beige complexion

Fine nose

Microscopic ear

The blue eye

Mesopotamian lips, full of meanders, The whole thing radiates magnetism, an irresistible aura of benevolence and cordiality.

3. About Dumas’s afro-descendant origine and its influence on his work and public image, see Cahier Alexandre Dumas n° 50 : Dumas, écrire noir/blanc, J. Anselmini et D. Desormeaux (dir.), Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2023.

Dumas’s physical characteristics evolved over the course of his life, and these changes were exaggerated by illustrators for comic effect. From the 1850s onwards, cartoonists accentuated his growing belly, which they ultimately came to depict as a grotesque obesity. By the 1860s onwards, caricaturists homed in on Dumas’s senescence (he was then reaching his seventh and final decade), and they assumed him to be senile. He was often depicted in the company of his son, who had also become famous, playing up a supposed rivalry between the two and presenting the elder Dumas as an inverted type: the prodigal father of a responsible son. A caricature by Hippolyte Mailly, published in Le Hanneton on June 20, 1867, seems to echo Dumas fils’s anecdotal comment that “Mon père est un grand enfant que j’ai eu quand j’étais tout petit !” (My father is a big child that I had when I was very little!) The cartoon also alludes, via the little rocking horse with a woman’s head on the ground, to the sultry affair between the ageing Dumas and the young Adah Menken, who was then the talk of the town for her role in a popular equestrian melodrama (fig. 6).

In addition to his distinguishing physical features, the famous characters, settings, and adventures that Dumas spawned in his writing became part and parcel of the author’s graphic portrayal. Notably, in many of the caricatures, Dumas inherits the attributes of his Musketeers, becoming the so-called “fifth” Musketeer. A cartoon by Carlo Gripp, published on the cover of L’Image on February 16, 1868, shows Dumas founding his Parisian newspaper Le Dartagnan by re-enacting the opening pages of Les Trois Mousquetaires, when d’Artagnan arrives in Paris on his “buttercup” horse. “This brave d’Artagnan,” the caption sneers, “who was thought to have died in the service of Louis XIV! Now he’s back in Paris, not to join M. de Tréville’s musketeers, but to make copies.” (fig. 7). Under the sharp point of the caricaturist’s pencil, Dumas’s life and his literary creations were interchangeable worlds. This went in the opposite direction as well: cartoons made of Dumas’s literary characters, such as the “Popular novels” series illustrated by Marcellin for Le Journal pour rire, were frequently imbued with aspects of Dumas’s own biography.

A source of constant inspiration for cartoonists, Dumas was caricatured from every angle, from the beginning of his career in the 1830s to his death in 1870, and even beyond. In fact, after 1870, cartoons and drawings began referring to episodes of Dumas’s posthumous celebrity. The erection of a statue in his honor in 1883, for example, gave rise to a rebus entitled “Dumas aura sa statue” (Dumas will have his statue) in Le Monde illustré on April 16, 1881. Much later, the entry of Dumas’s work into the public domain in 1952 was greeted by a cartoon by Hubert Giraud in the November 5 issue of the magazine Noir et Blanc.

To be sure, even during the author’s lifetime, caricatures of Dumas were not always cruel. A great deal of sympathy can often be found in these comic portraits, whose jest did not necessarily entail malice. Yet whether they came with good or with bad intentions, one thing is clear: these caricatures were an extraordinary organ of publicity for the author, contributing immensely to his widespread popularity and long-lasting renown.

Who exactly is the man that Eugène Giraud portrays in 1836 (cat.1)? This remarkably large drawing is one of the first, if not the very first, documented caricature of the writer.4 Born in 1802, Dumas began his literary career in his twenties, publishing Nouvelles contemporaines in 1826 and writing several plays. It was only in 1829, however, that Dumas would become a household name. This happened virtually overnight, after the breakthrough February 10 premiere of his Henri III et sa cour at the at the ComédieFrançaise. (The play premiered a year before Victor Hugo’s Hernani, and can thus be considered the first French Romantic drama, though it has been ultimately superseded by Hernani in the literary canon.)

In May 1831, Dumas followed that success with Antony, a drama of contemporary life. Brimming with adulterous passion and biting jealousy, headlined by two “stars” of the time (Marie Dorval and Bocage), the play was perhaps “the greatest literary event of its time,” as Maxime du Camp wrote in his Souvenirs littéraires. 5 In the bottom left corner of Giraud’s drawing, Dumas himself inscribed the famous last lines of this play: “She resisted me, I murdered her!” With these words, proclaimed after our hero kills his mistress with her consent, Antony clears her name in the eyes of her husband, who had just burst into the room where the lovers were staying. (This was a different era, to be sure!)

In the ensuing years, Dumas’s renown as a playwright continued to rise following the successes of La Tour de Nesle, Richard Darlington, Angèle, and other dramas. In 1836 Dumas earned yet more acclaim with Kean, whose eponymous hero was played by Frédérick Lemaître, and that same year Dumas also began publishing other kinds of writings. After penning a few reviews for L’Impartial, for instance, Dumas became the official theater critic of the major daily newspaper La Presse, which further broadened his influence and fame. Around the same time, he also began publishing his “Scènes historiques” in La Presse, marking the beginnings of his efforts as a historical novelist, which would take off in full force in the 1840s.

4. The musée Carnavalet in Paris holds in its collection a copy of our drawing, formerly attributed to Eugène Cicéri (1813-1890).

5. Maxime du Camp, « Souvenirs littéraires », Revue des Deux Mondes, 3e période, t. 51, 1882, p. 815.

By 1836, Dumas was a Parisian, national, and even international celebrity (his Impressions de voyage document his travels abroad). As portrayed that year by Giraud in his fulllength portrait, he was a man of fashion, in every sense of the word, as well as confident and poised. In the painter’s fine watercolour, the model’s elegance is obvious, a quality enhanced by the delicacy of the work’s colours, which sing in subtle harmony with its cream background.

Dumas is dressed in grey pants that mold “the best made leg in the world” (as one of Dumas’s own novels puts it!) and which was adopted by young Romantics in the late 1820s, who adored all things medieval. The young man’s pointed boots are likewise a voguish reprise of the Middle Age “colts” that the Jeunes-France and other Romantic lions brought back into fashion and updated for modern times. The collar of his white shirt is doubled by a black scarf tied high and tight around the neck (styled “à la Saint-Just,” after the Jacobin leader of the late Revolutionary period), and Dumas dons a pearl grey jacket that matches his trousers, but with moiré highlights, accentuating his slimness. Over that jacket is a short-cut brown pourpoint, the lapels of which are of black velvet or silk. Finally, he sports, with elegant nonchalance, those must-have accessories for any dandy: a top hat and white gloves. In short, Giraud portrays an immaculately dressed Dumas, who looks as if he has just left the theatre or some electrifying social gathering. Having frequented Nodier’s Arsenal in the 1820s and the salon of his mistress, Mélanie Waldor, in the early 1830s, by 1836 Dumas was well established in Paris’s high-minded social circles, taking part in literary coteries such as Victor Hugo’s Cénacle.

Though it accentuates his physical peculiarities for comic effect, Giraud’s depiction is largely faithful to the thirty-four-year-old Dumas. The writer’s most striking feature was his tall stature, which Giraud elongates improbably. Dumas himself said that he was so appreciated in Nodier’s salons, for example, because he was so tall that he could light the chandeliers without resorting to any other expedient!6 Another distinguishing feature was Dumas’s hair, which the author himself described as unruly. In his Mémoires, he recounts the taunts he received for his frizzy tufts, and his despair at not being able to tame it, even with the help of Paris’s most experienced hairdressers.7 Giraud plays up this feature, as well as others that seem to have come from Dumas’s African heritage, in particular his fleshy mouth and his warm complexion.

6. Dumas told this story in the first chapter of La Femme au collier de velours (1849).

7. Mes Mémoires, éd. C. Schopp, Paris, Robert Laffont, « Bouquins », 1989, t. I, chap. LXXIII, p. 537-538 and 572.

Yet despite the comic exaggerations described above, one finds no trace of cruelty in this gentle, sympathetic portrait. The painter Eugène Giraud (1808–1881), a few years younger than Dumas, was renowned for his penetrating observations of the subtleties and peculiarities of social life, but he never used his graphic aperçus as mean-spirited weapons against his models. He rose to fame at about the same time as Dumas. A student at the École des Beaux-Arts from 1821 to 1826, he won the Prix de Rome for engraving in 1826, then turned to illustration in order to support his family. He exhibited at the Salon for the first time in 1831, showing mainly portraits. By 1833, he was already well acquainted with Dumas, and he took part in the costume ball Dumas organized on March 30 in a flat at 25 rue de l’Université, which was decorated for the occasion by the city’s finest artists, including Delacroix. The two men would become close friends, as well as artistic collaborators: Giraud provided sketches of costumes and sets for some of Dumas’s plays, including Charles VII chez ses grands vassaux (1837), Caligula (1837), Les Demoiselles de Saint-Cyr (1843), and Une fille du Régent (1843).

In the autumn of 1846, the two companions met again in Madrid, Spain, where they attended the marriage of the Duc de Montpensier to the Spanish Infanta. They then journeyed as far as North Africa, with Dumas writing down his impressions of the trip while Giraud painted them. The Musée de Castres has 62 pen-and-ink drawings by Giraud on blue wove paper, most of them captioned by Dumas. Many of his vignettes were also included as engravings in the first edition of Le Véloce : De Paris à Cadix, Dumas’s account of this journey (1847). This same trip had an important influence on Giraud’s painting of Spanish and Orientalist subjects. The two men’s working relationship continued back in France with new theatrical collaborations after Dumas founded the Théâtre-Historique in 1847. All the while, Giraud became renowned as one of the most brilliant caricaturists, publishing in L’Artiste and Le Charivari, and he remained a prominent portraitist (his portraits of Flaubert and Delacroix are particularly memorable). He also designed the costumes for plays adapted from Dumas’s novels, including Le Comte de Monte-Christo (1848) and La Guerre des femmes (1849). Finally, Giraud drew new caricatures of Dumas in the 1850s, one of which featured in his famous series Les Soirées du Louvre (1858–1870).

As a counterpoint to the portrait of Dumas by Giraud, let us quote this written portrait of Giraud by Dumas: “Giraud is not a painter, he is painting itself. To draw, he doesn’t need any particular consecrated object; when the pencil is missing, when the charcoal is lacking, when the brush is absent, when the pen doesn’t answer the call, Giraud draws with charcoal, with a match, with a cane, with a toothpick; what strikes his subtle and mocking mind most of all is the ridiculous side of objects; his eye is like one of those disenchanting mirrors that exaggerate and distort all physiognomies.”8 But in distorting

8. Dumas, Le Véloce. De Paris à Cadix, Paris, Somogy, 2001, p. 57.

his friend’s face for the purposes of caricature, didn’t Giraud somehow capture Dumas in the most faithful and vivid way, revealing to us his indomitable determination and irresistible bonhomie?

The Dumas that Étienne Carjat depicts in the late 1850s is no longer the slender young man found by Giraud in 1836 (cat. 2). Having reached the age of fifty-seven in 1859, Dumas had already been overweight for several years. The notorious bon vivant had trouble resisting the temptations of consumption: he drank soberly, but loved to eat and cook! His talents as a maître-queux were renowned among his friends, and the newspapers soon asked him to write columns on food, which he compiled and completed at the end of his life into perhaps his last masterpiece, Le Grand Dictionnaire de cuisine

As it happens, Dumas’s overweight figure did not detract from his seductive powers. Carrying on vigorously into his sixties, Dumas kept his thick brown hair, and he continued to collect mistresses. With the smile of his fleshy lips and the smiling little “crow’s feet” that flanked his eyes, he radiated a continuously good humor and exuded an almost magnetic force of attraction. The friendly face reflected in Carjat’s caricature testifies to the sympathy that this talented, generous, and humorous man – this “genius of life,” in a phrase – inspired in those who knew him.9

Dumas’s appetite for life was reflected in his prolific literary and journalistic output, and Carjat alludes to this quality in his portrait. In the 1840s, Dumas became known as a “king” of French serial novels, reigning alongside Eugène Sue and Frédéric Soulié. This was a particularly productive decade for Dumas: with the collaboration of Auguste Maquet, he wrote and published a great many novels, from the Trois Mousquetaires to the Comte de Monte-Christo, La Reine Margot, Joseph Balsamo, Le Collier de la reine, and several other works. All the while, Dumas also wrote travelogues, chronicles, and fantastic tales.

In the early 1850s, however, the popular writer encountered hard times. In the aftermath of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s coup d’état on December 2, 1851, Dumas left France for Brussels – though, admittedly, for financial rather than political reasons (the ThéâtreHistorique he had founded in 1847 went bankrupt, and Dumas hoped to escape the clutch of his creditors). When he returned to Paris in the autumn of 1853, he could no longer count on Maquet, who no longer wanted to do business with him, and the Parisian public had seemingly forgotten Dumas in favor of his own son, whose La Dame aux

9. “Génie de la vie”: This expression was written by George Sand to describe Dumas, after his death, in a letter to his son, Dumas Fils. Claude Schopp used it as sub-title for his biography of Dumas (Paris, Fayard, 1997).

camélias had triumphed first as a novel (in 1848) and then as a play (in 1852). For Dumas père, winning back the public’s attention would involve a new venture: the founding of a newspaper, Le Mousquetaire, in which he would publish his own Mémoires (the beginning of which appeared in Girardin’s La Presse) as well as talks, literary and dramatic criticism, and various other kinds of writing.

Le Mousquetaire was a remarkable attempt to popularize literature, and it was typical of the daily cultural press that flourished under the Second Empire while its political press was muzzled by the censorious government of “Napoleon the Lesser.” Dumas, hoping to make the most of his celebrity, turned his paper into a monument to his own glory and to that of Romanticism. As Dumas’s secretary, Noël Parfait, put it, this was the most extraordinary “monument to egotism” that could be erected! Likewise, many journalists and cartoonists (notably Marcellin, in Le Journal pour rire) poked fun (more or less gently) at the megalomaniacal character of Dumas’s undertaking. Le Mousquetaire folded for good in 1857, but it would not be Dumas’s last adventure in journalistic selfaggrandizement. In 1857, he began printing Le Monte-Cristo, a newspaper that Dumas proudly wrote entirely by himself, as he boasted on its title page: “Le Monte-Cristo, journal hebdomadaire de romans, d’histoire, de voyages et de poésie, publié et rédigé par Alexandre Dumas, seul” (Le Monte-Cristo, weekly journal of novels, history, travel and

poetry, published and written by Alexandre Dumas, alone). This seemingly outlandish claim in turn became a popular recurring joke for journalists and satirists.

It was Dumas’s insatiable appetite for journalism and literature (or was it bulimia?) that Carjat burlesqued in his 1859 caricature, poking fun at on the various enterprises with which Dumas was thought by some to have squandered his talent. In Carjat’s drawing, Dumas’s pockets overflow with sundry writings: newspapers, Le Mousquetaire, Le Monte-Cristo, his Mémoires, travelogues, and more. Georges, La Reine Margot, and other titles decipherable on the drawing’s left side refer to Dumas’s ongoing output of novels. (His historical novel Les Mohicans de Paris, for instance, was then being serialized in Le Mousquetaire.) Likewise, the two inkwells that the writer has strapped to his clothing, along with the oversized quill that he has slipped into his pocket, bear witness to his intrepid writerly efforts: Carjat’s Dumas, we find, has devoted his life to filling in columns and pages, even while on the move! Dumas, who never ceased working on innumerable projects at once, seems to define himself as he did his great hero, the Count of Monte Cristo: a “desirer of the impossible.”

Like Giraud, Carjat drew his model with humor yet sympathy. Unlike Giraud, he emphasizes Dumas’s intellectual and cerebral dimension by giving him a disproportionately large head, under which his tiny body almost disappears. The features of Dumas’s face are only slightly distorted, bearing witness the more realistic tendencies of this caricaturist and artist. Étienne Carjat (1828–1906), sixteen years Dumas’s junior, was born to a modest family, and he discovered drawing as a teenager while apprenticed to a silk manufacturer. His caricatures, which became exceedingly popular, were published in various periodicals, including Le Boulevard, which Carjat founded, and Le Diogène, which he co-founded. From the late 1850s onwards, the artist turned his attentions to photography, which he had learned from Pierre Petit, before opening his own studio in Paris, rue Laffitte, in 1861. He soon became, alongside Nadar, one of the most famous celebrity photographers of his time.

Both Carjat’s drawn portraits and his photographs (many of which are now famous, including those of Rossini, Hugo, Baudelaire, and Verne) are generally distinguished by their spare compositions, largely devoid of unnecessary decoration. One of his bestknown portraits is that of a young Arthur Rimbaud (1871). Carjat frequented the “Vilains Bonshommes” circle, which from 1869 brought together artists such as Banville, FantinLatour, Verlaine, and Rimbaud. On one notable 1872 occasion, Carjat quarreled with Rimbaud, after which Rimbaud struck him with a sword and cane. In retaliation, Carjat destroyed his negatives of the famous poet. Carjat was also a close friend of Gustave

Courbet, and as politically headstrong as the realist painter: he supported the Commune and contributed political poems to the newspaper La Commune, as well as a collection entitled Artiste et Citoyen (1883). In addition to depicting Dumas in the present caricature, Carjat made a fine full-length wood engraving of the writer that he printed in Le Diogène of August 17, 1856, as well as a famous bust-length photograph (probably dating from 1867), which he published in the Galerie contemporaine, littéraire, artistique (a weekly review) in 1876.10

Dumas’s immense figure and his immoderate tendencies are also reflected in the caption, written by Joseph Méry (1797–1866), at the bottom of Carjat’s drawing: “A moral and physical giant, / Prose or verse, everything pleases him / Alas, he is not complete / He does not like music.” Méry’s epigram is a friendly one: he was close to Dumas and collaborated with him in the writing of Le Mousquetaire. His last line, moreover, was somewhat facetious: although Dumas did not compose opera librettos (which Méry did), music is often represented and staged in Dumas’s work. The writer had frequent contact with Liszt and Rossini, and he reflected on both the bewitching beauty and the magnetic dangers of music. In any case, it is certain that Dumas did not, on the whole, disdain music, any more than he did painting or sculpture. Indeed, Dumas was a great lover of the arts in general, as well as a fervent collector of Delacroix.

Dumas did not hold this humorous legend against Méry, whom he held in high esteem; nor did he begrudge Carjat for his biting and witty caricature. Let us end with these words from the writer about his friend Méry – a high compliment that, in our view, could equally serve as Dumas’s self-portrait: “He is one of those special creatures whom God made smiling, and in whom he has put all that is good, elevated and spiritual in other men. Méry has the heart of an angel, the head of a poet, and the mind of a demon.”

10. The preliminary drawing, with pencil on brown paper, was acquired by the Société des Amis d’Alexandre Dumas.

Author

Julie Anselmini

Design

Tia Džamonja

Editing

Catherine Gimonnet, Noémie Goldman & Andrew Shea

Scans & Photographs

Jérôme Allard – Numérisart; Université de Caen Normandie – service d’infographie; CCO Paris-Musées / Musée

Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

Special thanks to (by alphabetical order) Melissa Hughes and her team, Valérie Quelen & David Simonneau

© Agnews – September 2024