THE HEART OF ACADIA, GARDEN OF EARTHLY DELIGHTS, ISLAND SENTINELS, SUMMER ON SPRING GARDEN ROAD

seven Hotels & Resorts in Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick & Nova Scotia

THE HEART OF ACADIA, GARDEN OF EARTHLY DELIGHTS, ISLAND SENTINELS, SUMMER ON SPRING GARDEN ROAD

seven Hotels & Resorts in Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick & Nova Scotia

Publisher/Editor-in-Chief

Crystal Murray • cmurray@saltscapes.com

Vice-President of Sales

Fred Fiander • ffiander@saltscapes.com

Associate Publisher Lauren McKenney • laurenmckenney@advocatemediainc.com

Senior Editor

Jodi DeLong • jdelong@saltscapes.com

Senior Editor/Copy Chief

Trevor J. Adams • tadams@metroguide.ca

Account Executives

Pam Hancock • phancock@saltscapes.com

Michele White • white@metroguide.ca

Senior Director Creative Design and Production

Shawn Dalton • sdalton@saltscapes.com

Production Coordinator

Nicole McNeil • nicole@acgstudio.com

Production Assistant

Kathleen Hoang • khoang@metroguide.ca

Designers

Roxanna Boers • rboers@saltscapes.com

Lisa Gillis • lisa@acgstudio.com

Sharon Matson • sharon@acgstudio.com

Kazeem Onafuwa • kazeem@acgstudio.com

Saltscapes is published seven times annually by: Metro Guide Publishing, a division of Advocate Printing & Publishing Company Ltd. 2882 Gottingen St., Halifax, N.S. B3K 3E2 Tel: (902) 464-7258, Sales Toll Free: 1-877-311-5877

Contents copyright: No portion of this publication may be reprinted without the consent of the publisher. Saltscapes can assume no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts, photographs or other materials and cannot return same unless accompanied by self addressed stamped envelope.

Publisher cannot warranty claims made in advertisements. Saltscapes is committed to Atlantic Canada’s unique people, their culture, their heritage and their values.

Subscription Services

Enquiries please contact: Toll Free: 1-877-885-6344

subscriptions@saltscapes.com PO Box 190 Pictou, N.S. B0K 1H0

Subscriptions: Canada, one year (7 issues) $39.95, two years (14 issues) $59.95 (plus applicable tax) U.S. one year $39.95 (Cdn.) plus $17.00 shipping Overseas one year $39.95 (Cdn.) plus $29.00 shipping

Subscriptions are non-refundable. If a subscription needs to be cancelled, where applicable, credits can be applied to other Metro Guide Publishing titles. Please note that each circumstance is unique and election to make an offer in one instance does not create obligation to do so in another.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada.

Canada Post Publications Mail Agreement No. 40064799 ISSN 1492-3351

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: Saltscapes Subscriptions, PO Box 190 Pictou, NS B0K 1H0 Email: subscriptions@saltscapes.com

Printed by: Advocate Printing & Publishing, Pictou, N.S., Canada

On our cover

Saltscapes: Photography by New Brunswick Tourism / Jon Billings Sobeys: Photography by Tourism Nova Scotia / Dean Casavechia Bay Ferries & Northumberland Ferries: Photography by New Brunswick Tourism / Jon Billings

Saltscapes is a

of:

Golf and much more attract visitors to this village on the Canada/U.S. border

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY DALE DUNLOP

COVID had a devastating effect on tourism in Atlantic Canada.

The village of Perth-Andover in the Upper Saint John Valley suffered a serious financial blow when the venerable Castle Inn closed. To add insult to injury, Canadian members of nearby Aroostook Valley Golf Club were denied access to a route they had been using for more than 80 years to get to their club. However, as my wife Alison and I discovered on a visit to the area last summer, with adversity comes ingenuity. The inn has reopened not just as a hospice, but as a learning centre as well, and those resourceful golfers have come up with a unique way to reach their beloved course.

The Castle Inn is now the Pathsaala Inn, a Sanskrit word for “seat of learning.” It is one of four Canadian campuses of the Elephant Thoughts charity, which supports educational programs in India, Nepal, Tanzania, Mexico, and Cuba, primarily serving Indigenous communities.

The campuses offer a combination of programs that teach culinary,

hospitality, horticultural, and business skills. I was told that about 50 per cent of the students at the campus are Indigenous. Executive Director Jeremy Rhodes described the charity’s relationship with the Tobique First Nation.

“Elephant Thoughts has been working alongside their friend and strong partner Wolastoq Education Initiative (WEI) based in Tobique First Nation for over 10 years, co-delivering alternative education programs,” Rhodes says. “WEI is a partner in our youth programs taking place at Pathsaala.”

Built in 1936 by a local lumber baron, the inn resembles a small French chateau. Set amid well-tended flower and vegetable gardens, it has an ideal location overlooking the Saint John River. The interior is decorated with some unusual and beautiful artifacts and folk art from the countries where Elephant Thoughts does its work, including masks, statues, and ornamental boxes. You’ll want to explore the different common rooms

Step back into 19th century New

The first hole, appropriately dubbed the International, plays right along the border and a ball hit out of bounds is literally in another country

with your camera. The collection of exotic doors alone is worthy of a photo gallery.

Creature comforts include an indoor pool, steam room, hot tub, hiking paths, a bar and 13 rooms, all with unique décor. Breakfast is included. On Fridays and Saturdays renowned Indigenous Chef Ray Bear teams with local Chef Matt Francis to oversee an evening meal that features a combination of foraged ingredients, herbs, and vegetables from the garden and locally sourced seafood, meat, and poultry.

When I asked Ray why he would make the six-hour commute from his home in the Halifax area every week, he responded that he enjoys, “work in an environment where young individuals can learn at their own pace and thrive in their unique ways, free from the constraints of a traditional school setting.”

Ray added that he teaches through the lens of “Two-Eyed Seeing,” which integrates modern teaching methods with the philosophy of being one with the land.

The Aroostook Valley Golf Club is one of two Canadian courses that abut the United States border and has members from both countries. The course was built in 1929 by a group of Americans who deliberately positioned the clubhouse within Canada so that they could legally have a drink as, until 1933, Prohibition was still in effect in Maine.

On our first visit you could drive to a

parking lot on the Canadian side of the border, but it involved a short stretch on a road that was in Maine. American border officials nixed that option a few years ago. Today, Canadian access is via a dirt road through a potato field, to a parking lot where you take a golf cart another kilometre along the left side of a paved road that is actually in Maine. So just getting to the club house, which is entirely within Canada, is quite an adventure. There are more detailed directions on the website.

This part of New Brunswick is a land of rolling hardwood hills intermixed with farmland, perfect terrain for a golf course. It is one of the most scenic courses in Atlantic Canada with a few very memorable holes.

The first hole, appropriately dubbed the International, plays right along the border and a ball hit out of bounds is literally in another country. The Canada/U.S. border markers along this hole are a great place for a photo.

The Punch Bowl, the par-five 14th hole, has one of the most demanding approach shots you’ll find anywhere, requiring a precision downhill shot that must avoid a large pond that guards the tiny green. It is followed up the equally difficult par three Devil’s Hole, a daunting tee shot through a narrow chute that is all carry to the green 30 feet in elevation

below the tee box. These two holes alone are worth the trouble to make your way to Aroostook Valley. The 9th and 18th holes feature a huge double green with United States and Canadian flags on the pins.

After the round of golf, there are some great outdoor activities to pursue in Perth-Andover. The Cultural Waterfront Walkway, a portion of which is on the Trans-Canada Trail, features a series of plaques telling the story of settlements in the village from the Maliseet through the English, Irish, and Scottish periods. At the information booth you can rent kayaks, canoes, or paddleboards to explore the river or go fishing.

If you didn’t have lunch at the golf course, try one of the great croissant sandwiches at the 878 Waterfront Bistro or enjoy a cold one at the Tobique Trading Company that doubles as a craft brewery and a coffee roastery.

To make this a true golf getaway, consider playing the modern Covered Bridge Golf Course in Hartland and Mactaquac Golf Course, which hosts future PGA players at the Explore NB Open.

pathsaala.ca

avcc.ca

coveredbridgegolf.nb.ca

nbparks.ca/en/activities/1/mactaquac-golf

BY DARCY RHYNO

To eat a Chicken Bone, “bite through it, breaking the jacket,” says David Ganong, past president for more than 30 years of Canada’s oldest candy manufacturer, Ganong Brothers. He’s not talking poultry. The man sometimes referred to as Canada’s Willie Wonka is referring to a favourite Atlantic Canadian Christmas sweet, which resembles a pink bone.

“You’ve got the sweet, cinnamon-

flavoured jacket on the outside and the bittersweet chocolate in the centre, which is a nice combination,” says Ganong. In St. Stephen, across the border from Calais, Maine, the company established in 1873 is the first stop on one of New Brunswick’s three culinary road trips.

Follow the Bay of Fundy, beginning at the Chocolate Museum in the original

Ganong factory, where visitors sample the goods and watch as workers hand dip confections in chocolate. Ganong Brothers invented Chicken Bones in 1885, plus an early chocolate nut bar in 1909. Like Chicken Bones, Pal-o-Mine is still around today. Early every August, St. Stephen hosts Chocolate Fest, a sweets festival with events like a pudding eating contest, jellybean fun run, and “choctail” (chocolate cocktail) hour.

Departing Saint John, the province’s second culinary route follows the Saint John River, or Wolastoq in the Indigenous Maliseet-Passamaquoddy language, which flows through the entire province. The ostrich fern grows along its shores. Its fresh shoots called fiddleheads are harvested in spring and made into delicious dishes. Its curly fronds feature on New Brunswick’s coat of arms.

Mary Ellen Hudson with Fredericton Tourism talks about the capital city’s culinary prominence. “Fredericton boasts the largest number of craft brewers per capita in the Atlantic provinces with 26 local breweries, cideries, distilleries, meaderies, and wineries.” She suggests picking up a copy of the Taproom Trail, a map guiding visitors to 11 taprooms across the city. A stamp at each wins a prize.

The ploye, made with buckweat flour, is a tradition in the Madawaska Valley and area. Often a substitute for bread, ploye is a hearty pancake, a meal said to calm the appetites of hungry field workers. It’s served with molasses or maple syrup, and just plain butter. A ploye is never flipped while cooking, as it will bubble nicely from the bottom to hold those sweet toppings. Buckwheat is nutrient rich and gluten free, but in a pinch, whole wheat flour can be substituted.

In nearby Saint Andrews, funky cafés like Honeybeans and bistros like SeaBreeze are scattered among colourful shops and busy wharves where whale watching tours depart. Ferries based in neighbouring Blacks Harbour carry visitors to several islands, including Grand Manan, where harvesters fish lobster in the bay and dulse, a purple seaweed dried as a salty snack, is foraged.

In the port city of Saint John, the culinary scene revolves around the city market. Founded in 1876, it’s the oldest continuously run farmers market in Canada and a national historic site. Daily, the deputy market clerk rings a bell to mark the opening and closing of vendor stalls. Saint John is known for restaurants serving international cuisine, including Lebanese, Asian fusion, Irish, and Italian, plus for late nights at taprooms like Big Tide and wine bars like Happinez.

Hudson says that vendors at the Garrison Night Market and Boyce Farmers Market have spun off many restaurants. In 2019, Jenna White expanded from Jenna’s Nut-Free Dessertery stall at Boyce into her own restaurant. Venturing beyond desserts, her Indigenous roots show on a menu with wild rice and fiddleheads. “I serve our breakfast sandwiches on bannock because it’s important for me to share my culture. We grow vegetables, garlic, and herbs in my yard, and I showed my kids how to grow the three sisters: squash, pole beans, and corn.”

Driving north, you’ll see that potatoes are New Brunswick’s most important crop. They inspire festivals and museums like Potato World in Florenceville-Bristol. Endless fields of potatoes grow along the highway as it follows the river to Edmunston, a city also known for its buckwheat pancakes or ploye. A staple for early French settlers, the hearty treat is best served with butter and maple syrup.

Find more culturally connected foods along the Acadian coast from Shediac to Campbellton. Acadian restaurants are filled with more traditional cuisine, including chicken fricot or stew, and tartes aux coques or clam pie.

Seafood is prominent on menus along the coast, including at Shediac where a 90-tonne sculpture of a lobster

1 cup (250 mL) white flour

2 cups (500 mL) buckwheat flour (AKA green buckwheat flour or Tartary buckwheat)

2 cups (500 mL) cold water

1tsp (5 mL) fine salt

2 cups (500 mL) boiling water

2 tsp (10 mL) baking powder

Instructions

Mix first four ingredients. Add the boiling water and baking powder. Mix again. Cook in a hot, greased pan on one side only until cooked through. Serve with molasses, sugar, or maple syrup, and butter, or any other sweet condiment such as berry jam.

welcomes visitors. Today, restaurants offer a variety from traditional seafood chowder to sushi. At Adorable Chocolates, chocolate making has evolved to a fine art. Inside the artisan shop and cafe, sample a few of their handmade bites. I select the Taste of the Sea Assorted Chocolate box which includes Atlantic sea salt caramels, truffles, and chocolates in the shape of seashells. Unlike Ganong’s Chicken Bones, I won’t need any instruction on how to devour this box of goodies.

Tomlinson Lake Hike to Freedom Trail pays tribute to the Underground Railway

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY DALE DUNLOP

Many people have no idea that the Underground Railway that enslaved Americans used to escape to free states in the north and Canada had its northernmost terminus in New Brunswick. It’s a fascinating story that National Geographic featured as one of nine ways to enjoy Canada’s natural beauty.

The Underground Railway was a series of secretive routes that those on the run to freedom could use to move north. They received food and shelter from sympathetic people, many of whom were Quakers. Estimates vary widely as to the number of people who were emancipated over the many years the system was in place, but according to the Canadian Encyclopedia, between 30,000 and 40,000 made it to Canada. Of those, about half came between 1850 and 1860, largely due to a significant piece of American legislation in 1850.

Prior to 1850, escapees who made it to a free state were generally considered safe, but that changed with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act. This permitted southern bounty hunters to capture and bring back to the South any escapees they could capture in free states. The British had abolished slavery in 1834 in

the colonies that would become Canada, which made it imperative for fugitives to get across the border to be truly free.

The most northern place of refuge on this newly revived Underground Railway was at the small community of Fort Fairfield, Me. Here James Fitzherbert, a transplanted New Brunswicker, owned a tavern where he would hide the freedom seekers in a secret room. When it was safe, he would guide the people to a logging road that crossed the border. Once the fugitives reached Tomlinson Lake, they knew they were in Canada and safe.

Largely through the efforts of two volunteers, Joe Gee and Graham Nickerson, the Tomlinson Lake Hike to Freedom trail has been re-created, and now anyone can trace the steps of those whose lives were changed forever once they reached the lake. Joe’s family has been living in the Tomlinson Lake area since arriving as Loyalists after the American Revolution. Graham is a descendant of both Nova Scotian and New Brunswick Black Loyalists and is currently taking his PhD at the University of New Brunswick.

When asked about why he and Graham took on this project, Joe responds, “The

Tomlinson Lake project is important for a lot of different reasons. First, to keep this history alive. Also, sharing this story of the Underground Railroad and building up on its awareness has given folks better understanding of that history, what was happening in our community at that time.” He adds, “Our past, present and future is all connected, therefore it’s important to have a clear understanding of our past in order to create a better future for all.”

The trail begins at a parking lot on the south side of Tomlinson Lake where interpretive panels detail the people involved on both sides of the border. Based on his research, Graham surmises that the Tomlinson family, who were early settlers in the area and for whom the lake is named, aided the refugees once they were in Canada. From here, oral history has it that the newly minted Canadians made their way to one of the existing black communities in the region, many of which dated from the Loyalist migrations in 1786. The Underground Railway was a secret organization so there are few written records; oral history plays a large role in reconstructing what transpired in the 10 years that Tomlinson

For those who have hiked here previously, a return to Tomlinson Lake will provide a new experience.

Lake was used as an escape valve. Also at the trail head is a modern log cabin with a guest book, table, and wood stove. Just behind the cabin there is the entrance to the trail that has evolved over the years. The present trail starts at the lake and completely encircles it in a much more scenic route of about three kilometres. Much of the information about this trail online is outdated and refers to the old trail that no longer exists. For people who have hiked here before, a

return to Tomlinson Lake will provide a new experience and one that will take you to the spot where the fugitives would first know they had reached freedom.

Plans are underway to re-create, over the next two years, the squatter’s hut and pit house that were built on the old trail.

In the first weekend of October, the Tomlinson Lake Hike to Freedom organization hosts a walk around the lake with re-enactors, a pop-up museum from the New Brunswick Black History Society, and traditional food cooked over an open fire. During the 2025 event, the organization will unveil a new interpretive panel detailing the role many New Brunswickers played in the American Civil War, including the story of Sarah Edwards, who, disguised as a man, served as a Union spy and soldier.

Tomlinson Lake Hike to Freedom Trail 548 Miller Rd. Beaconsfield, N.B.

facebook.com/tomlinsonlakehiketofreedom/

caption

BY DARCY RHYNO

Following Camilla Vautour into the interpretation centre at Kouchibouquac National Park, the entire Acadian experience is contained in a single room. Vautour, formerly with the park’s visitor services, stands before a wall-sized map. She points out villages expropriated when government created the park.

“It took about seven years to complete,” says Vautour of the expropriation process. “Some were looking at the establishment of the park in a good way, others not at all.” The creation in 1969 of the 238-square-kilometre park on New Brunswick’s Acadian coast required the forced removal or destruction of entire communities, including houses, churches,

and 1,200 people. I follow Vautour to a window etched with the names of those relocated, stories of individual families, and a wall of mailbox doors representing each family. This room is part of the park’s efforts to heal a deep wound.

In some ways, the park’s creation echoes le Grand Derangement or the Great Expulsion. In 1755, British forces deported Acadians from Atlantic Canada, where they’d lived for more than a century. Over 12,000 lost their homes, farms, and belongings, some even their lives, when they were shipped away. By 1764, the British permitted Acadians to return, scattered in isolated communities, some along this coastline.

Kouchibouquac sits smack dab in the

middle of the Acadian coast where those isolated settlements grew into towns like Shediac, Bouctouche, and Miramichi, pulsating with the life and history of a people determined to express their heritage in noisy festivals, traditional foods, and a bold flag. To the tricolour red, white,

and blue stripes of France’s flag, Acadians added a yellow star that shines like a homing beacon in its upper left corner. The flag decorates houses, mailboxes, even lighthouses across the region.

Each town distinguishes itself, often in big, boisterous ways. A 90-tonne, 11-metrelong lobster sculpture welcomes visitors to Shediac, the province’s lobster fishing capital. Francois Poirier, co-owner of the tour company, Viva Shediac, tells me about the weekend “picnic train” from Moncton that chugged out to Shediac, crammed with visitors for lazy summer days on the beach.

Shediac’s population triples in summer, Poirier says, so it has long been an exciting culinary destination. “It’s the dynamics of the restaurants and friendly competition. Everyone has their specialty.” His tour includes tasty bites at Kuro Sushi, quirky originals like the Alice in Wonderlandthemed Le Moque-Tortue bistro, and the decadent Adorable Chocolates.

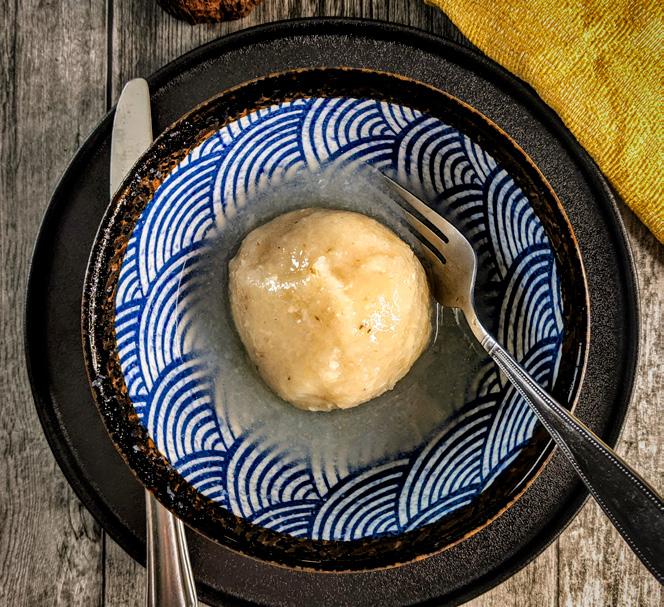

When it comes to more traditional fare, Poirier says, “Acadian food is simple food. Acadian poutine (poutine râpée) is really salty because Acadians were poor back in the day, so they had to salt everything to keep it.” This poutine has little in common with the famous Quebec version. A meatball is enfolded in shredded potatoes, then boiled and served with ketchup or brown sugar.

Bouctouche is best known for a single fictional character. Created by Acadian writer Antonine Maillet, La Sagouine, or the Washerwoman, is so beloved there’s a whole theme park dedicated to her, Le Pays de la Sagouine. I ask actor Abel Cormier, who plays Walk Alone, another Maillet character in the washerwoman universe, what it means to honour the greatest Acadian author.

“I think of my ancestors,” says Cormier. “You have to realize, they were taken from their homes and deported, some of them never to be seen again. Imagine. That’s why, whenever we talk about Acadian history, I always get a little tear. Today, we celebrate like crazy for ourselves and for our ancestors because they did not have that chance.”

Caraquet is located on the Acadian peninsula, tipped with Miscou Island, home to the Miscou Island Lighthouse, a New Brunswick landmark that appears in many tourism ads. Caraquet, population 4,300,

is best known as the place to celebrate Tintamarre. Every Aug. 15, thousands descend on the town to march, shout, bang pots and pans, reunite with fellow Acadians, and generally make a great noise to celebrate their culture and identity.

Bathurst and Miramichi bookend the peninsula, the latter famous for its river, fished by American presidents and movie stars. Near the mouth of the river, Beaubear’s Island, a national historic site is named for Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot, who led a resistance against the British during le Grand Derangment and established a refugee camp here for Acadians and Indigenous Mi’kmaq.

Between Bathurst and Miramichi, the Village Historique Acadien depicts daily Acadian life from 1770 to 1949. Construction of a 2.2-kilometre circuit leading through an artificial town of 40 buildings began in 1969, the year Kouchibouquac was established. That process stands in sharp contrast to Kouchibouquac’s relocation program and two centuries earlier, the expulsion by the British. Rather than a dismantling, the village is a complete re-creation of l’Acadie through the ages.

Karine of Viva Shediac shares this fricot (Acadian chicken stew) recipe from her grandmother, Marie-Jeanne Boudreau.

Ingredients

1 chicken

4 carrots

4 potatoes

1 onion

1 stalk celery salt, pepper to taste summer savory to taste

To make dumplings

1 tsp (5 mL) baking powder

1 cup (250 mL) flour fricot liquid

Directions

In a large pot, boil a chicken until cooked, 165F/74C internal temperature. Remove chicken. Keep stock simmering. Peel, wash, and cut carrots, then add to pot. Peel, wash, and cut potatoes into small cubes. When carrots are partly cooked, add potatoes. Add salt and pepper to taste. Thinly dice onion, and add to pot. Slice celery and add to pot. Summer savory is the key to a good fricot; add it last, a bit at a time to taste. Don’t overcook. When the end of a knife can pass through the potatoes, remove from heat and don’t boil again. Cut up the chicken and add to the pot. For dumplings, blend baking powder and flour with a little fricot liquid. When everything holds together, drop by the spoonful into the pot.

Even though Marie-Jeanne grew up eating fricot, her mother never had a specific recipe, and recipes are transmitted verbally through the generations, as this one was. The origins of fricot are simple: the first Acadian settlers were farmers and fishermen with large families, just as Marie-Jeanne and Roméo Boudreau’s. They would make the most of all the food, having worked hard to get it. They would start their soup by boiling a chicken to make stock, then they would add in vegetables that would keep for long periods, potatoes, and carrots.

Fricot is a hearty meal, and soup is the easiest to add to when unexpected company arrives, or can be a simple leftover. On fricot nights, after working long shifts as a nurse, Marie-Jeanne would haul her big pot to her mother-inlaw Marie’s house, and she would teach her how to make the dish.

BY DARCY RHYNO

When our tour group enters the Cupids Legacy Centre, we’re greeted with the sweet strains of Edward Ryan’s accordion. The centre’s friendly lead interpreter plays until everyone is gathered. Setting the accordion aside, he begins the story of his beloved Cupids, a village at the base of Newfoundland’s Avalon Peninsula about an 85-kilometre drive from St. John’s.

Sailing out of Bristol, England, in August 1610 and funded by a group of London and Bristol merchants known as the Newfoundland Company, John Guy led his band of settlers to Cuper’s Cove, a location he’d selected on a visit two years earlier. Over time, the name morphed into Cupids. This modern interpretation centre opened in 2010 on the 400th anniversary of Guy’s arrival. The year before, the Prince of Wales and Duchess of Cornwall visited the settlement. Why all the fuss about a single ship delivering a few people to a remote corner of the continent?

“Aboard the Fleming, there would have been 40 people, including John Guy, all their cattle and supplies on a ship the size of a school bus,” says Ryan. To give a sense of the cramped quarters, he lists off the Fleming’s supplies: blacksmith and carpentry tools, shovels, axes, muskets, crossbows, barrels of food, pigs, poultry, and goats. “It would have been a very tightly packed ship, not to mention the trip across the Atlantic would have taken three to four weeks. You can only imagine.”

Interpreter Heather Burry guides our group through Spracklin House, cautioning us to duck through the low doorways. Built in 1847, this house sits on stone salvaged from the John Guy settlement

Top: Spracklin House, the site of the archeological dig. Above: Excavations have been going on since the site’s discovery in 1995.

established on this site more than two centuries earlier. The main attraction is a diorama of John Guy’s settlement, its remains unearthed behind this house.

Outside, up a narrow, winding path, Burry leads us past recently excavated stone foundations to a frame-only ghost structure on the footprint of the building at the centre of the 16

structures that once stood here, including a blacksmith shop and a brewhouse. Dorset, Beothuk, Mi’kmaq, Viking: these peoples and others lived on Newfoundland well before English settlers arrived on Canada’s fourth largest island (16th in the world). But, says Burry, this tiny foothold four centuries old makes it the second oldest continuously-settled

1608 John Guy visits Newfoundland as its first governor.

1610 Guy and colonialists establish North America’s second English settlement.

English community in North America, behind only Jamestown, Virginia. John Guy’s attempted colonization in Cupids was difficult and fleeting.

“We know that in addition to the ones that we found, there were two sawpits and a gristmill.” Burry explains that a sawpit is a human powered sawmill. One man stands in the pit, the other above ground inside the timber house, and together they operate a long ripsaw that cuts logs into lumber. “There was a wooden palisade built around everything. We also have uncovered stone defence works and mounts for three cannons to protect the colony.”

Guy chose this location for the good soil and the tall trees. The colonialists cut timber to build the settlement and even a ship, the Endeavour, completed in 1610 or 1611. The vessel was to sail from Conception Bay around to Trinity Bay, where they traded with the Beothuk. Records show that they shared a meal with the Indigenous people in 1612. Despite this friendly encounter, disease and conflict killed the last of the Beothuk by 1830.

As for the colonists, Burry says written records speak volumes. John Guy wrote that Thomas Percy died of thought. Burry explains, “Thomas killed somebody before he left to come over. He didn’t tell anyone what he had done. The day before he died, he confessed it to John Guy.

1612 Threatened by pirates, Guy abandons a second Newfoundland settlement.

1613 Nicholas Guy is born, the first English child born in Newfoundland.

1614 Guy returns permanently to England where he was elected Mayor of Bristol.

1629 John Guy dies.

1838 Records show 16 ships with 365 men hunted seal from Cupids.

1847 Workers build the Spracklin House.

1910 Newfoundland issues a commemorative John Guy stamp.

1910 Villigars sew a giant Union Jack flag to commemorate Cupids’ 300th anniversary.

1983 A replica of the giant flag flies in the village, continuing today.

1995 The Cupids Historical Society hires archeologist Bill Gilbert to search for the Guy settlement. In eight days, he discovers its location.

2009 The Prince of Wales and Duchess of Cornwall visit.

2010 The Cupids Legacy Centre opens for the 400th anniversary.

2024 Excavations of the Guy colony continue, unearthing 170,000 artifacts to date.

So, he died of thought.” Smallpox killed others. One died of a bruise suggesting internal bleeding, and another of stiffness in the knees that kept one colonist bedridden for 10 weeks, prompting Guy to assign his demise to laziness. None of these single causes likely led to the end of Guy’s settlement, however. “We did find that the palisade wall was breached by cannons,” says Burry. “We found cannonballs, so at some time it was

attacked.” No one knows for sure who the assailants were during those attacks. Whatever the causes, the colony of Cuper’s Cove inside those palisade walls likely ended around 1621. But these shores were never completely abandoned There are gaps in the timeline, but in the first census of Newfoundland in 1836, some 840 people lived in the Cupids area. When you fall in love with a little corner of Newfoundland, there’s no going back.

STORY AND

PHOTOGRAPHY

BY DARCY RHYNO

It’s home to many animals, but Salmonier Nature Park in Eastern

Newfoundland isn’t a zoo. As the main facility for the Newfoundland and Labrador Wildlife Rehabilitation Program, its goal is to care for and release injured and orphaned animals back into the wild.

“They know the best way to benefit the animals,” says visitor Aaron Power, who first came to the park as a kid. Now, the park’s unique characteristics draw his family here once or twice a year. Power is a teacher in a middle school near St. John’s, so he also leads school trips.

“It was a good day,” he says of his most recent visit with his two kids. “We saw just about all the animals, some of which we hadn’t seen before, such as the woodchuck.” Sometimes, they

don’t see many animals. In those cases, he says, it’s more of a nature walk on the three-kilometre trail. “If people are aware of what the park is used for, they’re more appreciative when not seeing all the animals all the time.”

The park opened in 1978 as an environmental education centre. Today, its priorities are wildlife rehabilitation, research, environmental monitoring, animal welfare, and education. Of the park’s 40,000 annual visitors, 5,000 are Newfoundland kids learning about the island’s flora, fauna, and ecosystems.

Setting off along the boardwalk, I follow the trail through dense thickets of young firs and open, mature forest bearded in moss and lichen. Across the shaded expanse beneath them,

woodland plants like bunchberry and fern spread in carpets of green. As I walk through these shaded groves, I look for the park’s wildlife.

The first enclosure, designed more to protect the animals than to confine them, houses a lynx, but there’s no sign of it. The shy cat could be snoozing inside its house or recovering from injury. Other animals just happen to live around here. Settled in a patch of fresh grass, a snowshoe hare nibbles green shoots. It must feel safe living near predators like the lynx because it doesn’t flee when I lean over the railing to take its picture.

Further along the boardwalk, I find enclosures for mink, peregrine falcon, and woodchuck. “It was the first time we’d seen the woodchuck,” says Power.

“The kids were impressed by its shape, much plumper than they expected. It came out of its hole and nibbled some lettuce. They found that fun.”

Other animals live in wide open spaces. When the boardwalk leads over a marsh to a babbling brook, I spot bald eagles, their white heads glowing against the greenery. They don’t fly away because they can’t. One has a broken wing, so it will live out the rest of its life here, surveying its private wilderness and catching the odd frog and trout from the stream.

The largest animals are near the end of the trail. In enclosures so large I can’t see where the fencing ends, I spot a moose standing in the open. In the next, two woodland caribou lay in a grassy field, their antlers covered in soft velvet, slowly chewing their cud. It’s a privilege to be in their company, seeing them as relaxed as in the wild, and yet well cared for.

Salmonier has always taken its caregiver role seriously. Park staff were involved in the recovery of the Newfoundland marten. About the size of a cat, it looks like a cross between a mink and a weasel. Its round brown ears are set against a distinguishing orange patch on its throat. The marten that lives at Salmonier is from a captive breeding program.

“We’ve seen the Newfoundland marten before,” says Power, “and it was particularly active. It was going up the fence and really running around, putting on a bit of a show.”

This flavourful soup by Chef Barrie Hall makes a nice starter for a trout dinner at the Wilds Resort in Salmonier, N.L.

In 1996, with about 300 individuals left, the National Committee for the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada declared the Newfoundland marten an endangered species. By 1999, a first litter was born at the park. Some were released at Terra Nova National Park, and biologists are now seeing marten living beyond its borders. At last count, they number 556 island-wide, a total that removed them from the endangered list.

Just before the end of the trail, two juvenile Canada jays flit out of the trees to land on the boardwalk railing for a closer look at me. In youthful black rather than the more formal white, grey, and black plumage of adulthood, they seem fearless, as if to communicate that this is their woods, and I’m just some exotic creature from a faraway place, on display to satisfy their curiosity.

¼ cup (60 mL) vegetable oil

2 large onions

4 garlic cloves, minced

4 cups (1L) vegetable stock

2 large sweet potatoes, washed, peeled and diced

1 chipotle pepper

¼ tsp (1 mL) cinnamon

1 tsp (5 mL) cumin

A dash of adobe sauce

Place large stock pot over medium-high heat. Heat the oil and add onions. Stir occasionally, allowing onions to become golden brown. Add garlic and continue stirring. Add broth and turn pot up to high. Once broth comes to a boil, add remaining ingredients, turning heat back to medium. Add a dash of adobe sauce, if you have it. Let soup simmer, stirring occasionally. Once potatoes soften, carefully blend soup using immersion blender. Garnish with sour cream or yogurt.

BY DARCY RHYNO

If Mars had an atmosphere so we could walk on its surface, Gros Morne might be what it would look like. Among the red stones, a few plants struggle. Century-old juniper and yellow-flowering potentilla stretch their grey stems horizontally over the rocks where cushionshaped moss campion blooms in pink stars. With visions of wildflower meadows dancing in my head, I set out on the Green Gardens Trail in Gros Morne National Park on Newfoundland’s West Coast.

In fact, nothing could be more earthly than this sparse landscape. The trailhead begins at the edge of the Tablelands, a hunk of our planet’s mantle heaved to the surface, a process that took half a billion years and is replicated almost nowhere else on Earth. Down the trail, the landscape changes quickly.

“The descent takes you through boreal forest, thick with balsam fir, black spruce, and larch,” says Sheldon Stone, a visitor experience officer at Gros Morne for more than 30 years. “On the forest floor, look for bunchberry, called crackerberry in Newfoundland. You can see the white flowers in spring or bunches of red berries in summer.”

Stepping into a clearing, I sense I’m not alone. Across an expanse of low-growing conifers stunted by harsh winds, called tuckamore in the province, I spot a moose staring at me. We regard each other with suspicion until the big brown beast takes a step and fades into the forest.

When I reach the cliffs, the view stops me in my tracks, as it did Jami Savage.

“You’re in this green, lush forest, and you come out of it into the clearing, and see the cliff’s edges. That’s where the hike was a wow to me,” says Savage, an experienced hiker from British Columbia

who’s not easily wowed by coastal mountain trails.

“I didn’t know there was a huge view, waiting,” she says. “You’re right on the coast, and those huge, multi-storey cliffs are hanging in front of you, and you’re like, holy crow, how did this happen? You scale down to the beach at Old Man Cove, and you’re looking back up at the cliffs. It was just phenomenal. The sea stacks are castlesque with ocean vibes.”

Sheldon Stone explains the landscape’s origins. “There’s a variety of volcanic rocks that were formed in shallow water during the birth of an ancient ocean, about 550 million years ago. The ocean is long gone, but at Green Gardens, we can see layers of volcanic ash, conglomerate, and most striking, rounded pillow basalts, formed as lava cooled in mound shapes as it contacted seawater.”

Savage hiked the beach to a waterfall and to an enormous, rounded sea stack that finally blocked the way. She found herself intrigued even by the stones beneath her feet. “There are definitely unique types at the beach. When you hold them in your hands, they are shades of jade and teal.”

“It’s cool for someone from B.C. to swim in both the Pacific and the Atlantic,” says Savage. She took a quick dip, but within 20 minutes, the clouds rolled in.

“It was a very sudden change. From a safety perspective, definitely be prepared,” she warns, “but I wholeheartedly recommend the hike because you get that physical challenge, especially on the return.”

The return hike is nearly all uphill. When I climb back onto a low headland, Green Gardens explodes in colour. Groomed

by generations of sheep that still wander these cliffs, flower-flecked meadows give shape to the zephyrs off the Gulf of St. Lawrence as they play with the grasses. Dandelions and buttercups pop their yellow faces above the waves of green. Blue flag irises bloom in masses, and blue harebells, known to gardeners as a species of campanula, pop from crevices around the meadows. Spruce, bonsaied

by the incessant wind and short growing seasons, sprout from rocky outcrops.

“Spending time walking the meadows and along the beach is one of the highlights of summer in Gros Morne,” says Stone. “You need a few hours just to hike to the coastline and back. The fact that it takes some time and effort to get there makes it all that more special.”

For Savage, the challenging hike out was like reliving the best of Green Gardens. “I’m standing there overlooking this incredibly mountainous region with those huge, jagged cliff lines and big crevices with the waves crashing in at that circular beach. It really was a stunning view, and to me, any hike that’s worthwhile ends with a stunning view.”

One more stunning view remains. The hike of earthly Green Gardens delights continues to be rewarding right to the end with that Mars-scape of the tablelands looming in the distance. The hardest part is getting back in the car and driving away.

The park offers 23 hiking trails, totalling more than 100 kilometres. They range from the strenuous eight-hour, 16-kilometre return trek to the top of Gros Morne Mountain itself, to several hikes under two kilometres. Among them is the gentle Berry Hill Pond loop at the campground of the same name, which includes a wheelchair accessible section. All park trails are marked and include bridges, stairs, and boardwalks.

Learn about the multi-day Long Range and North Rim Traverse through the park’s back country at parks. canada.ca/pn-np/nl/grosmorne.

Several communities also maintain hiking trails. The Eastern Point Trail in Trout River leads to a coastal headline with views of the village. At Cow Head, the Lighthouse Trail follows the footsteps of early settlers, winding to the lighthouse for panoramic views.

• Get a waterproof trail map at the park’s visitor centre.

• Bring water, food, a headlamp, and extra clothes.

• Give somebody your destination, return time, and an emergency contact.

• Cell phone coverage is unreliable throughout the park.

• Hiking poles are helpful on steep and rugged terrain.

• Check the latest conditions at parks. canada.ca/pn-np/nl/grosmorne/ activ/experiences/randonnee-hiking/ etat-sentiers-trail-conditions

BY DARCY RHYNO

Snow crab cakes, lightly battered cod, and seared scallops. I’m savouring samples of this heavenly trinity at the Dock Restaurant in what I think of as one of Newfoundland’s prettiest towns, Trinity, the jewel of the Bonavista Peninsula. Trinity’s good looks begin right here in what the restaurant refers to as a restored fishing premises. Today, it’s a restaurant, marina, and gallery. The two-storey wooden building on the Trinity waterfront opened 300 years ago as a salt cod storage shed when Trinity was a wealthy salt fish capital. Today, its simple red façade stands out against the harbour, one of the last from a generation of buildings designed to serve the fishing industry. It’s easy to imagine moored Spanish and Portuguese schooners, ready to load their salted cargo.

Adirondack chairs and picnic tables painted yellow, blue, red, and green line the narrow dock. Ramps lead down to where small boats are tied, ready for a buzz around the bay. Inside, the building retains its storage shed feel with creaky wooden floors beneath the open joists of the second-floor gallery and gift shop.

The seafood-first menu is as straightforward and unadorned as the building itself: fish and chips, seafood chowder, snow crab claws and shoulders, fried cod tongues with pork scrunchions (bits of fried salt pork), and cod au gratin (baked in white sauce topped with cheese). Sampling such traditional dishes is like tasting Trinity’s history as a centuries-old seafaring town.

With the fishery in Newfoundland and Trinity a mere shadow of its former

industrial-scale self, the town has evolved while honouring its past. My favourite place to immerse myself in Trinity history is the Mercantile Premises Provincial Historic Site, a 19th-century general store stocked with period goods including handmade lace, bowler hats, shoes, yarn, children’s games, Morses Tea, and Post Toasties cereal. Another immersion experience awaits next door. Inside the Green Family Forge, a blacksmith is at work, hammering out everything from hinges and knives to delicate jewelry.

More recently, folks who locals affectionately refer to as “people with accents” have helped breathe new life into the town. The Gow family has been here for decades and are among the most active in revitalizing Trinity. Across town from the dock via quiet,

flower-edged lanes, is the Gow family’s Artisan Inn & Twine Loft Dining, built in another traditional waterfront building. Before they opened in 2000, Tineke Gow says there were few dining options around Trinity. On one occasion, after a long wait for a salad at one of the few restaurants in the area, a server arrived at their table, saying sheepishly, “I have to apologize. The truck didn’t come in. I have got nothing but greens from the garden.” It was a different time, she says.

The Gows’ Trinity adventure began when they bought a little house to fix up as a cottage. It had no running water. “This is a little bit of old world tucked into the new world,” Tineke Gow says. “There’s a sense of belonging, a sense of community. You feel very grounded here. I think that happens to a lot of people.”

Today, she and her husband and their daughter, Marieke, a sommelier, own a few buildings and rent some to visitors. Sitting down to dinner at the Twine Loft, Marieke recommends wines to go with dinner from those she procures for the restaurant. I order herb-brined pork with rhubarb chutney alongside potato whipped with apple, turnip, and parsnip, and a side of candied rosemary carrots.

“Pork goes with red wine, but I find you’re thinking about the sides, the sauces, too,” says Marieke. “I personally like going with white for pork because the rhubarb chutney is a bit tart. The rosé would meet nicely in the middle. If you were going with red, I’d go with a pinot noir because that’s also got a bit of that lightness, too.”

As we wait for our dinner, Tineke Gow points out the window to the rocky bluff overlooking town. “I’m hoping you go up the hill before you leave,” she says. “It’s stupendous. It has the highest elevation in the area. You’ll get a 360-degree view. If you do it in late afternoon on a sunny day, you’ll get fantastic light.”

I climb the hill the next morning as the previous day’s rainclouds lift. It’s not afternoon light, but the view is as promised. I see the bay and beyond to the islands and the open Atlantic. As if I’m looking down upon a perfect diorama, Trinity is radiant, bathed in fresh sunlight after a quenching rain, memories of sailing ships in the dark clouds retreating to the horizon.

Barren’s Blend Pudding with Hot Screech Sauce

From Artisan Inn and Vacation Homes, Twine Loft Dining in Trinity, by Twine Loft consulting Chef Bob Arniel. Twine Loft cooks Coreine Johnson and Cecily Marsden developed a gluten-free variant.

Ingredients for pudding

½ cup (125 mL) butter

1½ cups (375 mL) brown sugar

2 eggs

¼ cup (75 mL) flour*

1 tbsp (15 mL) baking powder

2 tsp (10 mL) cinnamon

2 tsp (10 mL) allspice

3 cups (750 mL) bread crumbs*

1 cup (250 mL) buttermilk

¼ cup (75 mL) blueberries

¼ cup (75 mL) partridgeberries or cranberries

Directions

Beat butter and brown sugar until light and fluffy. Beat in eggs until smooth. Add dry ingredients and milk. **Fold in berries. Pour in parchment-lined pan. Place a piece of parchment on top. Bake at 350F/177C for 50 minutes. **Remove top parchment. Bake for 10 more minutes.

Gluten Free Variation:

* Substitute gluten-free flour for regular. Add 1 tsp xanthan gum, if the gluten-free flour has none.

** Before folding in the berries, allow batter to rest 30 to 60 minutes. For gluten-free, turn off oven at the end, and leave pudding until edges are brown and the middle is springy.

Ingredients for screech sauce

½ cup (125 mL) unsalted butter

½ cup (125 mL) lightly packed dark brown sugar

3 tbsp (45 mL) Newfoundland Screech or dark rum

1 cup (250 mL) whipping cream

⅛ tsp (1 mL) salt

Directions

Combine butter and dark brown sugar in small saucepan over medium heat. Stir constantly. After sugar is incorporated, add Screech and stir to combine. Add whipping cream and bring to a boil, stirring constantly until thickened, about 3-4 minutes. Set aside.

BY DARCY RHYNO

Halifax’s Spring Garden Road

is one of the main west-east arteries into the city’s downtown, relatively short at about eight blocks, bookended with busy Robie and Barrington streets. There’s tons of history, dining, and retail in these few blocks.

Just off Robie Street, a pair of dining options hint at the variety to come. Across the street from the classy, Italianthemed Mappatura Bistro is the LGBTQ+ owned and operated Glitter Bean Cafe. This co-op is as much a community hub as a pleasant cafe that serves fair trade coffee, sweets, and light lunches.

A lifelong love affair with the Halifax Public Gardens, a national historic site,

pulls me into the formal Victorian gardens beneath tall shade trees and bordering wrought-iron fence. It takes up a block, providing a retreat from the bustle of the city since 1874. I follow the path of many pedestrians, tempted off the sidewalk into the gardens at one corner to emerge through the main gate at the other. Inside, I meander amongst the serpentine flower beds, exotic trees and shrubs, and features like statues, fountains, the duck pond, and the central bandstand.

Soft piano music wafts through the rhododendrons. Intrigued, I follow it to a grey-bearded man seated in a sunny spot, his fingers flitting across the keys of his electric piano. After I listen for a few

minutes, he smiles and introduces himself.

“Name’s Peter March,” he says. “I live in the apartment building across the street.”

I ask why he likes living in the heart of Halifax on Spring Garden Road.

“Where do I start?” he laughs. “There’s a beautiful park opposite me. I volunteer here because I’m retired. And God keeps this spot sunny for me.” March says he plays here every afternoon almost year-round, as long as the temperature is above freezing. He tells me about the convenience of walking to his bank, a grocery store, the magnificent library, and his favourite restaurant, La Frasca Cibi and Vini. “This is all within a 20-minute walk.”

Suddenly, he breaks off mid-sentence and gives a joyous shout in greeting to an old friend. They launch into lighthearted conversation, so I leave the two to catch up. From the main gate, the sidewalk traffic at South Park Street is suddenly shoulder-to-shoulder. Cars, buses, and taxis inch along the busiest five blocks in Halifax. From fast food and chain fashion shops at street level, to shopping malls, to independent eateries, pubs, and art shops, this stretch attracts people with its sheer variety and density.

Many storefronts have come and gone over the years, but one stands out as an anchor, an icon of Spring Garden Road since 1982. At the corner with Dresden Row, Jennifer’s of Nova Scotia, painted a shade of blueberry and adorned with a small mural of familiar city and provincial landmarks, is filled with Atlantic Canadian arts, crafts, preserves, books, jewelry, and clothing.

From there, the walk turns into a history lesson. A statue of the controversial Winston Churchill caught mid stride sits on a grassy resting spot across the street from the Halifax Provincial Court. The sturdy columns around the arched doors and windows of this classic sandstone building, completed in 1863, are topped with carved lions and faces. Spring Garden Road ends at three national historic sites, the towering Saint Mary’s Basilica, Government House (the residence of Nova Scotia’s lieutenant-governor), and the downtown cemetery known as the Old Burying Ground, with its unique concentration of gravestone art, now restored as an outdoor museum and park.

Enjoy a variety of cuisines from the many restaurants along the street.

On my way back up Spring Garden, I pause before the new Halifax Central Library, a magnificent example of modern architecture that’s won awards and public admiration. The multi-coloured glass exterior resembles a loose stack of books. Inside, a labyrinth of central stairways reminiscent of Harry Potter’s Hogwarts twists and turns up five storeys.

Back on the street, the restaurants have stirred my appetite. I visit Chicking,

a Korean-style chicken restaurant. I order the Galbi sandwich, a fried chicken thigh burger with spicy mayo, pickle, coleslaw, and knight sauce, a version of bechamel.

After a short wait, I’m off with my takeaway lunch to the Public Gardens in search of a shaded bench to enjoy my lunch in this peaceful Spring Garden Road setting, a highlight of summer in Halifax.

By Sam Paikowsky, executive chef at La Frasca Cibi & Vini on Spring Garden Road.

Ingredients

9 oz (250 g) Pane e Circo’s fresh fettuccine

2 tbsp (10 mL) freshly cracked black peppercorns

1/3 cup (95 mL) Pane e Circo pecorino (grated)

1/2 cup (120 mL) butter

2 X 4 oz (115 g) beef tenderloin

Instructions

Season beef tenderloin generously with salt and pepper. Pan-sear to preferred doneness. Rest 5 minutes after cooking to keep juicy.

To a pot of salted, boiling water, add fettuccine. Cook 2-3 minutes until just tender. Reserve 1 cup pasta water before draining.

In a dry pan on medium, toast some cracked black peppercorns until fragrant. Add a ladle of hot pasta water to pan. Simmer gently, reducing by half.

Add cooked pasta to pan with toasted pepper and pasta water. Toss in 3 tbsp each pecorino and butter. Stir and toss pasta continuously until cheese and butter melt into a creamy sauce. Add more pasta water if needed.

Twirl pasta onto plates and garnish with remaining pecorino. Slice the beef tenderloin and arrange on pasta. Serve immediately.

BY DARCY RHYNO

My day begins in the town of Antigonish where I’ve booked a room at the Antigonish Victorian Inn. With its many accommodation and dining options, Antigonish is a good base for exploring the 97-kilometre Cape George loop, part of the Sunrise Trail. From here, you can drive west to east on the Trans-Canada Highway and begin at Sutherlands River or take Bay Street east from town onto Route 337.

I prefer the east-west option because I like the sequence of stops, beginning at Crystal Cliffs Farm Road. This short detour gets me out to a quiet beach that ends at a low gypsum cliff. The soft stone in shades of chalk, salmon, and smoke are sculpted by the waves into organic oddities and smooth gems.

Back on Route 337, I follow the undulating coastline, up and down

hills and through villages. In pretty Ballantynes Cove, I walk the length of the wharf to check out the fishing boats, then visit the Bluefin Tuna Interpretative Centre to learn about local tuna fishing history and the lifecycle of the great fish. At lunchtime, the nautically themed Fish & Ships takeout across the street serves fresh local haddock and fries.

A few kilometres up the road at the Cape George Point Day Park, the star of the show is the Cape George Lighthouse. Since 1861, a beacon has shone from atop this cliff 123 metres above the water. It’s an octagonal white tower, tapered to a red cap. Simplicity is its eloquence, a tall sentry beaming its warning over the choppy waters below, keeping mariners safe.

Two kilometres farther along, the road veers southwest. I stop at Livingstone’s Cove Wharf Park for a few photos of the

coastline rising in gentle slopes from the ocean. Back in the car, I admire the view all the way to Big Island Beach where I stretch my legs. Refreshed, I double back about 14 kilometres to Knoydart Farm. At the cheese shop, a jolly Frazer Hunter offers samples of the flavoured cheddars he makes from his “happy” cows’ organic milk.

“If you buy my young cheese today and keep it for a year,” says Hunter, “it’s better growth in value than mutual funds.” I’m not sure where he’s going with this until he delivers his punchline that’s also a sales pitch. “So, when you leave here, you should be carrying two wheels of cheese.”

Cheese purchased, although not two wheels, I backtrack five kilometres to the seaside cliffs at Arisaig Provincial Park where I turn over a piece of shale to find a cluster of half a dozen brachiopod fossils. These clam-like creatures the size of my

fingernail lived on the floor of a shallow sea almost half a billion years ago, twice as far in the distant past as the oldest dinosaurs, and hundreds of times further than any of my humanoid relatives.

Holding their stony imprints, I’m humbled by the magnificent work of evolution. Walking back to the Arisaig wharf and lighthouse, I see Steinhart Distillery up the hill, my destination for an evening cocktail and a view of the sunset over the Northumberland Strait.

“Vodka making is a science. Gin making is an art,” says Thomas Steinhart. “You could do a hundred batches and never quite get it where you want it. Juniper is vital. You want it to stand out, but everything else shouldn’t be so prominent.” His technique for making his

award-winning gin is otherwise a long-held family secret learned on his grandfather’s farm back in Germany, but he also adds a little citrus, which his grandfather couldn’t afford. Steinhart offers a unique weekend-long “GINstitute By the Sea” experience. That tour is much longer and more educational because participants learn how to make gin, then distill a bottle of their own design with a mini still.

This evening, however, I’m just here for a cocktail and a perch where I can sip and savour. I choose the Eastside, a cocktail of East Coast ingredients: Steinhart Wild Blueberry Gin, fresh mint leaves, and Nova Scotian blueberries. Here’s to the many flavours and experiences on the Cape George loop!

Directions

Grab a shaker, add mint and fresh blueberries, and gently muddle. Add the remaining ingredients, ice, and shake well.

Double strain into your favourite cocktail glass. Garnish with a mint sprig. Enjoy!

BY DARCY RHYNO

Hubert d’Eon, a retired fisherman playing a boat builder, holds up a knee in the boat shop at Le Village Historique Acadien de la NouvelleÉcosse (the Historic Acadian Village of Nova Scotia) in West Pubnico. Behind him, a punt is under construction. Tools are arranged on the walls and the aroma of fresh wood fills the air.

“A punt is a small boat fishermen used to go from shore to boats moored nearby,” explains d’Eon. “This piece joins the bottom of the boat to the side. It looks like a hockey stick. This is the strongest

part of the tree, the trunk and root. I look for trees that have blown over with the root system sticking out the ground.”

All over the village, skilled interpreters work their time-consuming crafts. In the blacksmith shop, Ronnie d’Entremont builds up his coal fire before heating, then hammering, a white-hot length of metal into a wedge-shaped nail. “There’s an old saying,” he says as he works, “strike while the iron is hot.”

In the next building, Olen d’Entremont weaves a net. “I was a fisherman. Now, I pretend I’m a fisherman. That’s pretty

cool,” he says. “I’m making a gill net, a winter project for fishermen.” By passing the shuttle strung with twine this way and that, he makes a single mesh, one of the openings in the net that catches a single herring. For a 185-square-metre (2,000-square-foot) net, he makes this series of passes 210,000 times, taking 10 weeks.

Roger d’Entremont, the village board president, joins me for a stroll around the seven-hectare site. “Here, you can step back in time and see how Acadians lived in the early 1900s,” he says. Laundry

flaps on a clothesline in the coastal breeze, a woman mends a stick fence, a wheelwright builds a wagon wheel. Children tend gardens, bake biscuits, dip candles, and roll down a hill for fun. Cows graze in a pasture overlooking a salt marsh where haystacks stand like giant mushroom caps on wooden platforms.

“The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree around here,” d’Entremont says. The Pubnicos are one of the oldest Acadian communities in Canada. Founded in 1653, this is where French settlers Philippe Muis d’Entremont, Marie Helie, and their daughter Marguerite built the first home in what the Indigenous Mi’kmaw called Pogomkook. A century later, on July 28, 1755, British Governor Charles Lawrence ordered the expulsion of Acadians from what is now Eastern Canada, including Pubnico. After government lifted the expulsion order in 1763, some families returned to discover that English settlers had established themselves on the east side of the harbour.

Even today, some 250 years later, Acadians are concentrated in Pubnico and West Pubnico with a presence in East Pubnico. Together, the Pubnicos are a thriving community that takes pride in its history. Fishing boats are docked several abreast at Dennis Point wharf, the largest commercial fishing wharf in Atlantic Canada, testifying to

A traditional recipe using leftovers from a typical salt cod dinner called Patates, Molue et d’la graisse from the Café du Crique at the Historic Acadian Village.

Ingredients

1 yellow onion, chopped

1-2 tbsp (15-30 mL) fat from making lard scrunchions (fat pork scraps)

1-2 tbsp (15-30 mL) scrunchions

3 cups (700 mL) cooked mashed potatoes

1-1 ½ cups (250-375 mL) salt cod, rinsed, soaked and boiled

A little flour

1 egg

Salt, pepper, and summer savory

Directions

Cook onion in fat. When golden brown, add to mashed potatoes, smashed scrunchions, and pulled salt cod. You may use half salt cod and half fresh haddock to give a lighter taste. Add salt, savory, and pepper to taste and mix well. Add egg to help bind the mixture. Form into balls and flatten into patties. Roll in flour and fry until golden brown on both sides. Serve with homemade chow chow, AKA green tomato salsa. Fishcakes can also be frozen.

the rural lifestyle beside the Atlantic Ocean on which Pubnico depends. More than 1,000 fishers make their living here. The day of my visit, an experience called Living Wharves is under way.

“It’s very hard work,” says interpreter Louise Deveau of fishing. She talks about the dangers of working at sea and the best way to cook lobster, steamed in just a little water. As seagulls screech overhead, Deveau shows me how to splice rope with a tool called a fid. Living Wharves is a hands-on experience, so after her demonstration, she encourages me to try.

Acadians grew and harvested everything they needed for their pantries and medicine cabinets. At the nearby Musée des Acadiens des Pubnicos, Elaine Surette, president of the historical society that runs the museum, says,

“The Acadians learned how to use Indigenous medicinal plants and herbs.” As we walk the historically accurate gardens, our tour is set to the rhythm of Indigenous drummers celebrating centuries-deep ties with Acadians.

I complete my visit at Boatskeg Distilling, where two fishermen, Roddy d’Eon and Justin d’Entremont, craft spirits in a former boat-building shop. Both of d’Eon’s grandfathers were bootleggers, and when d’Entremont was looking for a purpose for the now unused boat shop, the idea of the distillery was born.

“That’s a boat skeg,” says D’Eon, pointing to the wall where one is displayed. “Underneath the propeller, the piece of wood that sticks out is a skeg.” Because of the rumours that kegs of booze were once buried here during prohibition, the name “boats keg” has a clever double meaning.

I order their top seller, salted caramel vodka on ice and toast the view: a seagrass meadow before shimmering waters. It seems the salt of the sea and the spirit of the Pubnicos are distilled right into my Boatskeg cocktail.

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY DARCY RHYNO

The air is so steamy, I can’t see across the sauna at Mysa Nordic Spa on St. Peter’s Bay, Prince Edward Island. Rubber-legged, I step outside where I pull a rope that pours a bucket of icy water over my head. At the plunge pool, I force myself into the frigid water for 30 seconds. This process is on the advice of Pippa, an attendant at Mysa.

“The Nordic spa works on the premise of heat, cold, rest, repeat cycles,” says Pippa. “We get our bodies really hot and sweaty in our sauna or steam room, which activates our muscles, then we need to cool down and stop our muscles from working, so we do a shock of cold.”

Recovering from my heat-induced stupor, I seek out the chairs overlooking

the bay where a cormorant dives, then resurfaces with its catch. Reclining here in a plush bathrobe, I let out a sigh that gives voice to the state of relaxation I’ve reached on my St. Peter’s weekender.

I’ve booked a night in one of Mysa’s on-site cottages, so dinner comes with the package. At the restaurant reserved for spa and cottage guests, Chef Seth Shaw

carefully builds dishes that highlight local ingredients, including those he grows in the Mysa greenhouse. Intrigued by the name, I order the lion’s mane mushroom steak finished with harissa and chimichurri sauce. A celery root hot pot topped with cheddar is the side. The flavours are so surprising and pleasantly rich, I slow myself down, enjoying every savoury mouthful.

Slowing down and savouring the moment becomes the weekend theme. After a sound sleep, I drive around the bay where Nature Space Eco Resort’s Heather Gunn McQuillan, co-owner with husband Jerrod, is holding a 90-minute morning yoga and meditation session. She instructs me and the other dozen participants to hold each posture for three

Left: The main office yurt at Nature Space Resort. Above: The Dragonfly Labyrinth at Nature Space Resort.

to five minutes. “The goal of yin yoga is not to engage the muscles,” she says.

“It’s actually to stretch the connective tissue. You’ll hear me cue things like release, relax, feel into your body. You’ll hear a lot of ‘let it go’ language.”

Her preferred practice is yin yoga, a combination of Chinese medicine and Indian yoga. Arranging our mats on the

PEGGY’S COVE NS

Nestled in iconic Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia, Six by the Sea is a collection of six historic buildings that have been lovingly restored to host East Coast-inspired businesses and cultural experiences.

Celebrating pride of place, Holy Mackerel is a whimsical retail shop.

Featuring a curated collection of unique products and crafts by over 100 Atlantic Canadian artisans and vendors, Holy Mackerel showcases the best the East Coast region has to offer.

Originally constructed as an auxiliary building to a family home, Spindrift Gallery has been transformed into a mainfloor art gallery. The gallery showcases historical exhibits and fine art by Atlantic Canadian artists.

Hunky Dory celebrates the beloved french fry and the renowned East Coast success story that influenced its take-out menu. Alongside the savoury, Hunky Dory serves gourmet soft serve ice cream treats.

Built in 1839, The Schoolhouse has been a place of learning and worship, a gathering space, and the scene of artistic presentation. In 2025, its doors are open for The Schoolhouse Tour

PEGGY’S COVE, NS SIXBYTHESEANS.CA

Overlooking iconic fishing boats, Margaret’s is a cozy East Coast café serving freshly brewed coffee and tea, Maritime-inspired baked goods, seafood chowder, and delicious gourmet paninis.

Grandmother’s Pound Cake

From Barbara Hansenbohler of 45 Steps.

Ingredients

9 oz (250 g) flour

9 oz (250 g) butter

9 oz (250 g) sugar

5 free-range eggs

1 tbsp (15 mL) baking powder

9 oz (250 g) yogurt

9 oz (250 g) ground nuts (coconut, almonds, or hazelnuts)

9 oz (250 g) or more of fruits, but 18 oz (500 g) maximum

Directions

Beat eggs with sugar and butter until frothy. Mix flour with baking powder, and stir into foamy mixture. Add yogurt. Add nuts and stir. Add flavouring ingredients as desired. Examples include cocoa, rum, lemon zest. Depending on preference and season, you can also add fruit combinations like apple with hazelnut and cinnamon, cherry with almond and kirsch, pineapple with coconut and rum. Be creative. The cake is called equal-weight cake because all the ingredients are equally heavy. You can reduce or increase the batter accordingly. Pour cake batter into a baking tray or small tins or muffins. Bake in a cake pan at 350F/180C for about one hour. Or on a tray, bake at 350F/180C for about 30 minutes, or as muffins for about 25 minutes.

floor of the Mongolian yurt where Gunn McQuillan hosts her sessions, we begin.

“Last week, we were looking at coming to stillness in the busyness, heat, and energy of summer,” she says. “Today, I want us to think about tuning into the nature around us and getting our energy from it.” As she speaks, a blend of harmonic tones and music fill the space. She asks us to settle into a connection with the Earth beneath us and to breathe deeply.

Nearly two hours later, Gunn McQuillan finishes with, “I hope you have a wonderful sunny Sunday,” and invites us back for her Wednesday sessions on the beach. Folks slowly pack up their mats and depart, some reluctantly. I stick around to chat.

“I came into yoga mostly for the mental healing,” says Gunn McQuillan, a veterinarian who endured postpartum depression. “When I suffered from that, I integrated mindfulness and yoga together, and it was like a door opened,” she says. After experiencing such significant benefits, she decided to train as a yoga and mindfulness instructor. Even now, she combines her occupations by integrating mindfulness into the curriculum at the vet school where she teaches.

Retracing my steps through St. Peter’s, I arrive at my last stop, the 45 Steps Inn. Swiss couple Barbara Hansenbohler

and Thomas Range fulfilled a lifetime dream in 2021 when they bought this big house 45 steps from the beach and opened their culinary beachside inn. “A lot of people come just to relax,” says Hansenbohler, who interned at a European Michelin Star restaurant. I too am here to relax, but also to participate in her Kitchen Club experience.

In the kitchen, I work at an unhurried pace, helping prepare my own evening meal. I cut ingredients for a melon cucumber salad to go with the salmon and asparagus main dish. Dessert is cake from her grandmother’s recipe. “My family is big,” she says. “My mom has three siblings, and they each have three kids. Everybody was often at our house, so eating and spending time together has always been important. My recipes are basic, so everybody who likes cooking can do it.”

Back in my turret room, I enjoy the sunset over the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the panoramic views over the beach. Something Gunn McQuillan told me comes to mind. “There’s a wellness story happening here in Eastern P.E.I.,” she said. “Nature Space, 45 Steps, and Mysa are really well aligned. All three of us are dedicated to well-being through the food that nourishes, the sensations around us, and the activities. It’s about being taken care of.”

Discovering the unique attractions of one of P.E.I.’s best day-trips

BY DALE DUNLOP

Most visitors to Prince Edward Island spend much of their time on the North Shore exploring the national park and enjoying the beaches for which the island is justly famous. But take a 30-minute drive east of Charlottetown and you’ll find out why the Point Prim area and its unique attractions make for one of P.E.I.’s best day trips.

Most people make the drive to the tip of Point Prim, jutting into Hillsborough Bay, to photograph and climb the oldest lighthouse on the island. Built in 1845, it is one of only three circular brick lighthouses in Canada, (although white shingles cover the bricks today). Unlike many of Atlantic Canada’s lighthouses, Point Prim is a designated heritage site under the aegis of Parks Canada, which means it’s properly maintained. Aside from being one of the prettiest lighthouses on the island, Point Prim is one of the few that allows visitors to climb to the top. Once inside, you can blow an old-fashioned foghorn. The entrance fee is a modest $6 for adults and includes a guided tour on request.

The former lightkeeper’s cottage is now a gift shop that sells P.E.I. handicrafts, all having a nautical theme. If you are feeling flush, you can spend $150 to buy a $20 Canadian coin that was minted for the 150th anniversary of the province’s entry into Confederation and features the lighthouse.

Your next stop should be the Point Prim Chowder House, which has been serving up local seafood and more for

decades. While its seafood chowder is famous, this is the only restaurant in the world where you can taste Pinette River oysters. Co-owner Paul Lavender explains why they are so popular, “Considered wild, these oysters grow naturally on the riverbed. They are unique in both taste and texture, which is why we have many repeat customers who come from far and wide to enjoy them at the Point Prim Chowder House.” Place your order at a service window and enjoy

your meal on the outdoor terrace which has a great view of the lighthouse. If it’s a bit chilly, you can eat inside.

Your next stop on Point Prim should be at Hannah’s Bottle Village, which is a labour of love by Gar Gillis to raise money for the IWK Children’s Hospital in Halifax. Started in 2002 with a church dedicated to his grandson, there are now about a dozen different miniature buildings including a school, general store, sports complex, and lighthouse.

It is a photogenic treat to explore this place, both inside and out. There is no admission fee, but each building has an IWK donation box and recently Mr. Gillis passed the $100,000 mark in donations. Also nearby is Lord Selkirk Provincial Park, 10 kilometres west from the entrance to Point Prim Road. Most Canadians learned in school about the Selkirk Settlers who founded the Red River Colony in the future province of Manitoba in 1811. They were Scots who

were displaced from their land in the infamous Highland Clearances, when property owners evicted thousands of tenant farmers from the lands they had tended for centuries, in favour of raising sheep. What most don’t know is that Lord Selkirk had already brought three boatloads of Scots to P.E.I. in 1803, where they settled on lands once occupied by Acadians before they were expelled by the British in 1758. A visit to this place tells the story of both groups.

The starting point is the replica of a typical Scottish croft house which contains many interesting artifacts found around the former Acadian village. These include a French coin dated 1680.

Outside interpretive panels tell the story of Lord Selkirk, who, although

a noble, felt deeply disturbed by the eviction of crofters from their homes in favour of sheep. He used his wealth to buy land in what was already the post-Acadian settlement of Belfast and paid for the transportation of 800 displaced Highlanders to start new lives here. The descendants of these Scots include two Fathers of Confederation and many other prominent Prince Edward Islanders. The upshot was that this event revived interest in the island as a destination for immigrants.

The final stop on this day trip should be at the Sir Andrew MacPhail Homestead in nearby Orwell. MacPhail was one of P.E.I.’s most distinguished citizens, earning a worldwide reputation for his skills as a physician, agriculturist and

novelist. His 1939 semi-autobiographical novel The Master’s Wife tells the story of life in rural P.E.I. in the late 19th century. J.M. Bumstead in The Peoples of Canada: A Post-Confederation History called it “A classic of Canadian social history.” Learn more about this polymath on a guided tour and then stroll through the MacPhail Woods Forestry Project, 57 hectares of deciduous trees that are alive with birdsong. Finally, return to the house for afternoon tea or a light snack in as bucolic a setting as you’ll find anywhere.

pointprimlighthouse.com chowderhouse.online facebook.com/HannahsBottleVillagePEI macphailhomestead.ca

BY SAM WANDIO

Repeat visitors to the gentle island won’t be surprised by its vibrant craft beer scene, but cider is its newest offering, and adventurous tasters can take in all four of the island’s cideries in one day. From the rolling hills of Bonshaw to the picturesque forests and farmland of Caledonia, to the pleasant rural sweep of Warren Grove, to historic Charlottetown, a cider outing will show you some of the best landscapes Prince Edward Island has to offer.

A trip to a cidery offers a winery-style outing. For the orchard experience, three of the Island’s four cideries grow many (or all) of their apples on site. If you wish you can tour the orchards, and then head to one of the tasting rooms to enjoy the fruits of their labour.

Close to Bonshaw and Strathgartney provincial parks and their hiking