Barrister the

In This Edition...

The Emerging Tort of Harrassment

Tuning the Crystal Ball: The Present & Potential Future of Earning Capacity Claims

Suing Well is the Best Revenge: The Tort of Public Disclosure of Private Facts

Alberta Election Results & the Implications for Auto Insurance

SUMMER 2023 ISSUE #137

MOVE FORWARD We’ve got your back, so you can

WhatIf?

WHY CHOOSE CASEMARK

• Interest rate DECREASES at the two-year mark

• Legal fees & disbursements always take priority

• Approval within 24 hours

• No hidden fees or recurring charges

• Flat $250 administration fee

• No complicated application forms

• Sustainable and responsible lending decisions

3 The Barrister FEATURES New Tort in Town: Tort of Harrassment Recognized in Alberta By Justin Monahan COLUMNS Letter from the Chair Letter from the Executive Director Letter from the Editor 10 3 The Barrister Alberta Election Results & the Implications for Auto Insurance: A Government Relations Perspective By Keith McLaughlin (New West Public Affairs) Barrister Case Law Review 45 8 13 15 6 Tuning the Crystal Ball: The Present & Potential Future of Earning Capacity Claims By Kyle T.H

Navigating the IME Request Process: A Quick-Start Guide for Young Lawyers By Erica Enstrom (Integra) Busted? Credit, Loans & Section 89 of the Indian Act By Hero Laird & Casey Caines The Emerging Tort of Harrassment By Dan Colborne, Megan Kunz, & Linda Jensen Suing Well is the Best Revenge: The Tort of Public Disclosure of Private Facts By Justin Monahan 18 21 27 30 41 Vision is A Beast By Dr. Anjana Sharma 43

Smith, C.S

THE BARRISTER EDITORIAL BOARD

The contents of The Barrister are for informational purposes only and do not constitute legal opinions by the Alberta Civil Trial Lawyers Association, its members or contributing authors, and should not be relied upon as such.

Statements and opinions expressed by the editors and contributing authors are not necessarily those of ACTLA. The official position or views of the Alberta Civil Trial Lawyers Association will be stated as such. Copyright © 2022 by the publisher, ACTLA. All rights reserved. Reproduction of any material herein without permission of the publisher is prohibited.

All advertising enquiries should be directed to the Editor-in-Chief at communications@actla.com

Publication Mail Agreement No. 40064387

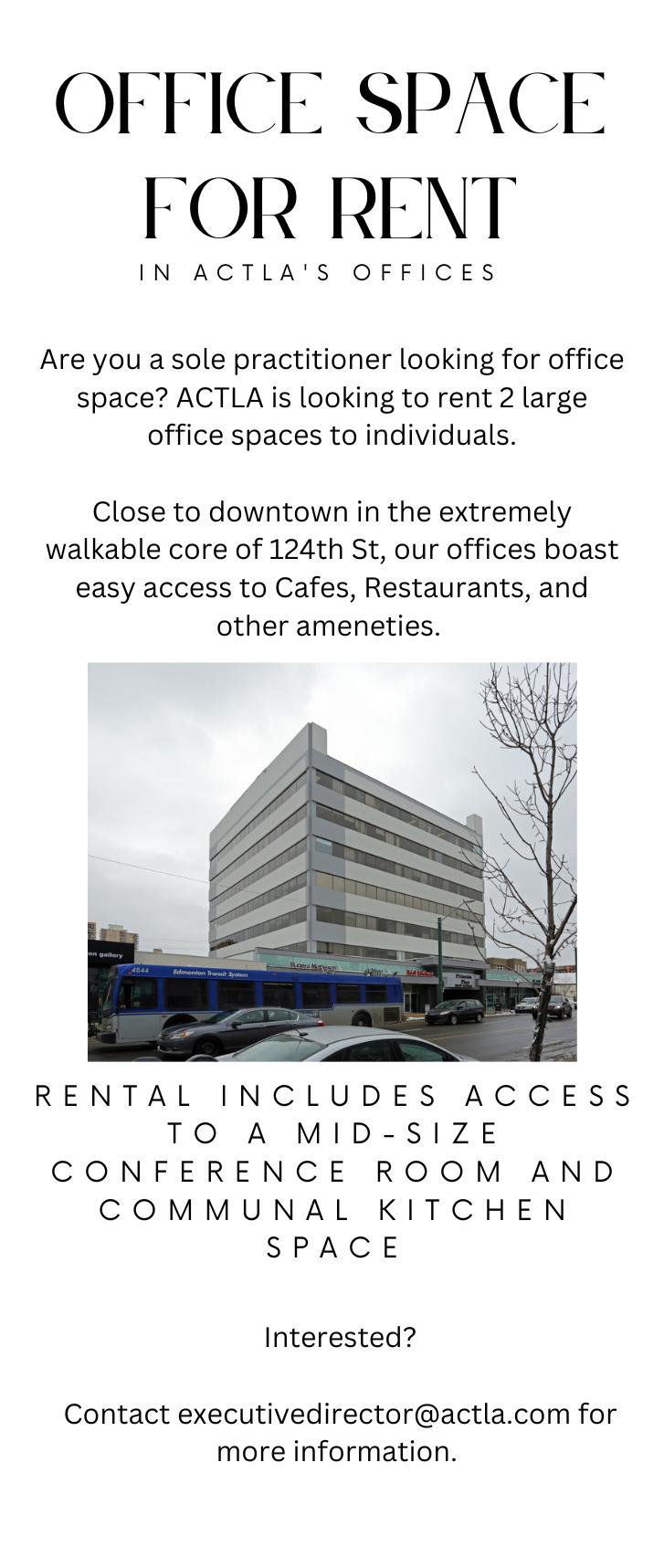

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: Alberta Civil Trial Lawyers Association 777-10339 124 Street, Edmonton, AB, T5N 3W1

4 Summer 2023

The Barrister is published quarterly by the Alberta Civil Trial Lawyers Association 777-10339 124 Street, Edmonton, AB, T5N 3W1 T: 780.429.1133 | 1.800.665.7248 | www.actla.com

Nash Calvert Editor in Chief

Amani Abdu Committee Member

Justin Monahan Committee Member

Peter Trieu Committee Member

ACTLA Mission Statement:

Advocating for a strong civil justice system that protects the rights of all Albertans.

2023-24 BOARD MEMBERS

Chair: Owen Lewis

Past Chair: Angela Saccomani, KC

Vice Chair: Mike McVey

Secretary: Jillian Gamez

Treasurer: Laura Comfort

Members-at-Large:

Jackie Halpern, KC

Joseph A. Nagy

Peter Cline

Geographical District Representatives:

North West: Leah Paslawski

North East: Waverly Mussle

Edmonton: Amani Abdu

Calgary: Sarah Coderre

Central: Ronke Omorodion

South East: R. Travis Bissett

ACTLA STAFF

Executive Director

Joy Jeong | executivedirector@actla.com

Communications and Events Services

Administrator & Editor-In-Chief, The Barrister

Nash Calvert | communications@actla.com

Finance & Member Services Administrator

Lochlin Zhao | membership@actla.com

PAST CHAIRS

Angela Saccomani, KC - 2022-23

Maia Tomljanovic 2021-22

Jackie Halpern, KC, 2020 - 21

Shelagh McGregor, 2019-20

Mark Feehan, 2018-19

Michael Hoosein, 2017-18

Maureen McCartney-Cameron, 2016-17

Nore Aldein (Norm) Assiff, 2015-16

Craig G. Gillespie, 2014-15

Donna C. Purcell KC, 2013-14

George Somkuti, 2012-13

Constantine Pefanis, 2011-12

James M. Kalyta, 2010-11

James D. Cuming, 2009-10

Richard J. Mallett, 2008-09

Arthur A.E. Wilson KC, 2007-08

Walter W. Kubitz KC, 2006-07

William H. Hendsbee, KC, 2005-06

Kathleen A. Ryan KC, 2004-05

Ronald J. Everard KC, 2002-04

Stephanie J. Thomas, 2000-02

James A.T. Swanson, 1998-2000

Gary J. Bigg, 1996-98

Stephen English KC, 1994-96

Anne Ferguson Switzer, KC, 1992-94

Terry M. McGregor, 1990-92

J. Royal Nickerson KC, 1988-90

Derek Spitz KC, 1986-88

5 The Barrister

Letter from the EXECUTIVEDIRECTOR

Joy Jeong, Executive Director ACTLA

Joy Jeong, Executive Director ACTLA

Summer

marks my one year anniversary of working at ACTLA. On June 6th, 2022, I came to this office for the first time and began my role as the Communications & Event Services Administrator. In October, I was happy to pass the torch to Nash and assume the role of Executive Director.

During my time at ACTLA, I have gained an enormous level of respect and appreciation for this organization's long-standing history and passionate membership. I am honoured to serve and advocate on behalf of this organization.

The spring season was a busy time with the Alberta election on our radar, and we are now preparing for an even more exciting summer season. The ACTLA office is excited to welcome Lochlin Zhao, our new Finance & Member Services Administrator. The growth of our office team will allow us to improve our abilities to serve our members.

This summer is also the beginning of a new cabinet. Congratulations to all candidates on a race well fought. We were active throughout the provincial election with our FAIR campaign, which focused on key messaging surrounding affordability and insurance. ACTLA is looking forward to working collaboratively with government, continuing to advocate for transparency in the auto insurance industry and against any version of nofault insurance.

We are also spending this summer gearing up for an exciting calendar of events in the fall. Our October Masterclass is expected to be an outstanding educational event, and we hope to see you all there in person. I know our event committee has been hard at work putting together an exceptional lineup of speakers. Further, our webinar lineup for the fall will be filled with a diverse range of topics, ensuring we are bringing you a comprehensive package of educational opportunities.

I am proud to see everything that has been accomplished this past year at ACTLA, and it makes me even more excited to see what the future has in store.

As always, I welcome our members to reach out to me with any comments, questions or even to just say hello. You can best reach me through email at executivedirector@actla.com

Sincerely,

Joy Jeong Executive Director

6 Summer 2023

Thank you to our Supporters

SPONSORS

CaseMark Financial

Platinum Sponsor 2023

Integra

Gold Sponsor 2023

Bridgepoint Financial

McKellar Structured Settlements

Elite Experts

DONORS

Platinum Donors

Norm Assiff Yanko & Popovic Joseph Nagy McLeod Law

Cuming & Gillespie Rodin Law Firm Edwards Injury Law

Cassidy Hea Injury Law

Gold Donors

KMSC Law Brian Conway Tarrabain Law Pipella Law

Vic Vogel Jane Lang LT Lawyers CAM LLP

Crash Injury Lawyers

Silver Donors

Jackie Halpern Harman Toor Walter Kubitz Waverly Muessle

Ryan Berget Grover Law Firm Safi Law Group Angie Mijalska

Grace Parrotta-King Cameron Brightman Ryan O'Fee Norma Mayer

McKellar Structured Settlements Hollick Chipman Heather Steinke-Attia

Bronze Donors

Jillian Gamez Christopher Rappel Stephanie Whyte

Gillian Clarke Shawn Sipma Paul Anderson Izaak Atnikov

Assessmed Viewpoint

Thanks to you, ACTLA can continue to support Access to Justice across Alberta

7 The Barrister

Letter from the BOARDCHAIR

Thisedition of the Barrister focuses on developments in tort law in Alberta. We are privileged to be part of a group of dedicated legal professionals who tirelessly advocate for injured Albertans that are seeking compensation for damages caused by someone else’s negligence - the very essence of tort law.

We are all too aware of the threats that our clients and everyday Albertans face in the ongoing efforts of those who wish to limit common law rights under tort law. In the wake of the recent provincial election and in the face of lobbying efforts by the Insurance Bureau of Canada (“IBC”) to curtail the legal rights of Albertans, it is crucial to underscore the importance of maintaining access to tort remedies in Alberta and highlight the ongoing efforts of ACTLA in safeguarding the rights of our fellow citizens.

As we all know, tort law serves as a pillar of justice, ensuring that those who have suffered harm due to the negligence or wrongdoing of others are provided the means to seek redress in court. Tort

Owen Lewis, Board Chair ACTLA

law plays a pivotal role in enabling injured individuals to pursue fair compensation for physical injuries, emotional distress, medical expenses, loss of income and other damages resulting from motor vehicle accidents. Over the span of the past 20 years, we have seen IBC’s efforts result in legislative changes which have diminished the ability of injured Albertans to obtain full compensation for their injuries that would otherwise have been available under common law.

The IBC is continuously active in their government lobbying efforts. Moreover, it is a known fact that the IBC makes every effort to capitalize on new governments, post election, to advocate for further tort deform. Notwithstanding the windfall profits experienced by auto insurance companies in Alberta over the past three years and the statistics which show that injury claims have remained stable from 2016 to 2019 and decreased significantly from 2020 through 2022, IBC still claims that personal injury costs need to be reduced by further limiting injured Albertan’s rights. IBC’s recent proposals to government promoting “choice in the marketplace” is a thinly veiled attempt to bring in elements of a no-fault system for the vast majority of those who experience injuries in motor vehicle accidents.. There is simply no legitimate reason to further limit the rights of injured Albertans.

ACTLA is firmly committed to countering any attempts by the IBC or government to curtail the rights of injured Albertans. Through continued advocacy with those in government and by educating the public with FAIR Alberta alongside like-minded partners in the medical industry and beyond, we will continue to highlight the importance of maintaining a robust tort system that ensures fair compensation for victims of motor vehicle accidents in Alberta. ACTLA will continue to engage with policymakers, stakeholders and the public to emphasize the significance of preserving access to tort remedies, protecting the rights of injured individuals, and upholding the principles of justice and accountability.

In closing, I encourage our members to continue the good fight on behalf of our clients and all Albertans. Additionally, we seek your further support for the cause by encouraging clients, friends, colleagues, neighbours, and acquaintances to follow Fair Alberta on social media and to speak with elected officials about maintaining tort rights in Alberta. Now is the time to act to protect tort rights in Alberta.

Sincerely,

Owen Lewis, Board Chair

8 Summer 2023

Letter from the Editor

Thisedition has been the most challenging to prepare yet.

Tort Law is a topic that, frankly, is hard to write about with any significant excitement as a non-lawyer. Of course, that’s not to say there is no excitement to be had with recent developments, and I hope that the content in this edition reflects that. Rather, it’s difficult as someone who is working to put this magazine together to try and keep it interesting, rather than wall upon wall of content-heavy text. I hope that this edition delivers on being our most educational of the year.

We start, as always, with another political update from our friends at New West Public Affairs who help make the FAIR AB campaign run as smoothly as it does. Our own editorial committee member, Justin Monahan, has provided two articles on tort law updates in Alberta, discussing both the Tort of Harassment and the Tort of Public Disclosure of Private Facts – and Bottom Line Research has provided an incredibly well-developed paper that highlights the justification and development of the new Tort of Harassment. It is not only new torts we discuss in this edition – recent updates in tort law may also affect how the courts calculate earning capacity claims, as discussed by Kyle T.H Smith, C.S’ article, Tuning the Crystal Ball: The Present and Potential Future of Earning Capacity Claims.

Nash Calvert Editor-in-Chief, The Barrister Communications & Event Services Admin, ACTLA

In celebration of June as Indigenous History Month, the Wahkohtowin Law and Governance Lodge graciously provided us with a research article that discusses s.89 of the Indian Act and how it has affected the First Nations population in Alberta and Canada with regard to access to credit. I urge anyone reading to reach out to the Wahkohtowin Lodge and offer support for the incredible work they do as part of the University of Alberta.

Unfortunately, this issue also marks the end of the Alberta Weekly Law Digest. With Roy Nickerson’s retirement and Thomson-Reuters no longer publishing AWLDs, The Barrister will be changing the format of our quarterly roundup! More information on that on Page 46.

I would like to take this opportunity to call out the Editorial Committee, without whom The Barrister would not have been made. From their collective efforts with editing the edition (and dealing with me), to Justin coming in under the wire to help make the Case Law Review happen for this edition, they are truly the glue that keeps The Barrister together. I would also like to thank Kerry Gellrich for her many years of work with the committee, and wish her all the best in her future endeavors. Your contributions will be missed!

The September edition of The Barrister will be focusing on your war stories from the courtroom. Whether you have a full article’s worth of stories or just a paragraph, we plan to put together a collection of the best. From entertaining to absurd to frustrating, I hope you will share your stories with us for publication.

As always, I can be contacted via communications@actla.com for article submission or advertising inquiries.

Sincerely,

Nash Calvert Editor-In-Chief

10 Summer 2023

DAVID P. STARK Contact Information 146 Wedgewood Dr SW Calgary, AB T3C 3G8 403.969.7967 starkd@shaw.ca www.starkmediation.ca B.Ed., LLB., FCIP Barrister, Solicitor, Mediator, Arbitrator, Conflict Resolution Trainer Member of the Canadian Academy of Distinguished Neutrals and Member of the BC Mediation Roster Society Member of the Law Society of Alberta

ALBERTA: (Servicing Calgary, Edmonton & surrounding areas)

Suite 338 – 11808 St. Albert Trail

Edmonton, AB T5L 4G4

(P) 780-328-6476

(F) 905-678-2939

BRITISH COLUMBIA: (Servicing Vancouver & surrounding areas) Suite 1080 – 777 Hornby Street Vancouver, BC V6Z 1S4

(P) 778-330-2080

(F) 905-678-2939

refer@assessmed.com

Assessments

Timely Reporting

Quality

–

AssessMed®

Alberta Election Results and the Implications for Auto Insurance: A Government Relations Perspective

By Keith McLaughlin New West Public Affairs

By Keith McLaughlin New West Public Affairs

Fromouranalysis,autoinsurancecompaniesoperating inAlbertahaveexperiencedwindfallprofits.Since 2020,autoinsurancecompaniesinAlbertahaveearned over$2.9billioninpre-taxprofit.

Therecent Alberta election saw a close competition between Danielle Smith's United Conservative Party and Rachel Notley’s Alberta NDP. While the UCP secured a majority government, the NDP emerged as the largest Official Opposition in the province's history, making significant gains in Calgary. Now that the election dust has settled, government’s attention is now focused on briefing the new cabinet and policy development on key files like energy, healthcare, and affordability (which includes issues like auto insurance).

Alberta's new cabinet features a mix of former ministers in new roles, some ministers in their old positions, and a few entirely new faces. The cabinet is larger than expected, consisting of 25 members, with a significant representation from battleground Calgary. Premier Smith prioritized competent, mature individuals who are good listeners and communicators, emphasizing qualities like discretion and good judgment. Loyalty is also a crucial factor, with cabinet members having to navigate decisions that balance loyalty to the premier, principles, conscience, and constituents. The cabinet's focus will be on addressing pressing issues in healthcare and relationships with the federal government, which requires ministers skilled in negotiation and discussion. Challenges include fixing issues within healthcare, dealing with

new climate and environmental regulations, and the impact of lower oil prices on the province's finances. Overall, the cabinet is positioned for stability and a mainstream approach under Premier Smith's leadership.

Throughout the election ACTLA and FAIR Alberta engaged in various government activities, including speaking with MLA candidates, raising awareness through social media about auto insurance, and post-election strategic planning. With the re-elected UCP now back in power, government relations and engagement are now a more critical priorities than ever.

Looking ahead, the following initiatives and engagements are planned by ACTLA, its partners at FAIR Alberta, and the medical community. First, an updated government relations strategy for the summer of 2023 will be developed to align with the UCP's renewed mandate. Second, introductions and congratulatory letters will be sent to new cabinet ministers and MLAs, emphasizing ACTLA's priorities and sharing recent polling data on auto insurance. Finally, FAIR will continue social media engagement, reaching Albertans and creating awareness about its stance on auto insurance matters.

13 The Barrister

The Alberta election results have brought about significant changes and raised questions about the future direction of government policies - including auto insurance. Organizations like ACTLA and FAIR are actively involved in government relations efforts to ensure the government understands key positions as it considers further reforms to the legal and regulatory landscape in which auto insurance operates.

Gathering support from MLAs and ministers in ensuring the rights of Albertans to access the court system are protected through continuation of the at-fault automobile insurance system is critical moving forward. In recent years, there have been calls to establish a no-fault auto insurance system in Alberta, like the system in British Columbia, but managed by private insurers. Since being implemented at the beginning of 2021, British Columbia’s no-fault system has seen many high-profile incidents where innocent victims have seen their lives changed forever at the hands of negligent drivers but have been left with no recourse to pursue lost employment income or pay for the treatment of their injuries.

Along with inflation and rising energy costs, large premium increases for auto insurance have been a major strain on many Albertans who continue to struggle with the ongoing affordability crisis. At the same time as Albertans struggle to afford premium increases, from our analysis, auto insurance companies operating in Alberta have experienced windfall profits. Since 2020, auto insurance companies in Alberta have earned over $2.9 billion in pre-tax profit.

Albertans deserve an auto insurance system that is affordable and protects their interests, rather than those of insurers. Government will be looking for policies that will lower premiums. What is important is that any reforms to Alberta’s insurance market must be fair to consumers and protect the civil rights of Albertans.

14 Summer 2023

New Tort in Town Tort of Harrassment Recognized in Alberta

By Justin Monahan

InAlberta Health Services v Johnston, 2023 ABKB 209 [Johnston], Honourable Justice Feasby determined it was necessary to recognize the tort of harassment in Alberta. Justice Feasby found that the defendant’s abusive and threatening behavior in this case, though it did not align with any previously established torts, caused considerable damages to one of the Plaintiffs. Accordingly, it was necessary and “long overdue” to recognize such a tort in this province and empower the courts to award damages when appropriate.

1. on a number of occasions, he threatened to financially harm AHS employees, stating, “My goal is to bankrupt AHS members....” 1;

2. he incited violence against AHS employees: “Now I don’t condone violence but when it happens to you, you’re going to deserve it” 2;

3. he compared AHS employees to “villains, Nazis, Gestapo, Communists, Fascists”3;

Though some aspects of the torts of defamation, assault, and privacy may address certain characteristics of harassment, the various specificities of said torts rendered them inapplicable in this case...

...The inability to apply existing torts to this case did not discount the tortious nature of the defendant’s actions. but rather demonstrated that it was time for the Court to recognize a new tort.

The facts of Johnston are as follows. The relevant Plaintiff was a public health inspector who was appointed as an “executive officer” under the Public Health Act [PHA]. Her responsibilities consisted of enforcing and educating Albertans about the PHA and the orders of the Chief Medical Officer of Health. In the period relevant to these proceedings, these orders mainly concerned the COVID-19 pandemic. The defendant, Mr. Johnston, was a resident of Calgary who publicly opposed the various measures that had been introduced throughout the province in an attempt to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic. Mr. Johnston was the host of an online talk show, creator of social media content, and former mayoral candidate in the City of Calgary. Mr. Johnston used his social media following to spread false and spurious claims regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and various public health or political officials.

Mr. Johnston engaged in the following behavior regarding the plaintiff:

4. as well as targeting the plaintiff directly on his talk show, he used various pejoratives to describe the plaintiff and her family; and

5. he circulated pictures from the plaintiff’s social media, continuously threatened baseless legal action against her, and on several occasions made defamatory and false statements about the plaintiff on national broadcasting platforms.4

15 The Barrister

1 Alberta Health Services v Johnston, ABKB 209 [17] 2 Alberta Health Services v Johnston, ABKB 209 [18] 3 Alberta Health Services v Johnston, ABKB 209 [19] 4 Alberta Health Services v Johnston, ABKB 209 [20/21]

The unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and events surrounding this case made it difficult for Justice Feasby to follow previous rulings on similar matters. In Merrifield v Canada (Attorney General), 2019 ONCA 205 [Merrifield], the Ontario Court of Appeal found that the facts of that case did not justify the recognition or creation of a tort of harassment. The Court also, however, did not rule out the possibility for the future development of a tort of harassment “that might apply in appropriate contexts.”5 Instead, the Court found only that, at that point in time, existing cases and the facts of Merrifield “presented no compelling reason to recognize a new tort of harassment.”6

Justice Feasby, however, concluded that the evidence before him in Johntson established that the defendant’s actions were tortious and that the current law failed to address the damages caused by such intentional harassment. Based upon Mr. Johnston’s constant use of pejoratives to describe the plaintiff to a potentially vast audience and repeated threatening or inciting of both physical and financial harm to the plaintiff and her family, it was reasonable to deduce the negative results of such actions.

Justice Feasby found that, despite the evident negative impact and fear created by this behaviour, no existing tort fully accounted for Mr. Johnston’s actions. Though some aspects of the torts of defamation, assault, and privacy may address certain characteristics of harassment, the various specificities of said torts rendered them inapplicable in this case. The inability to apply existing torts to this case did not discount the tortious nature of the defendant’s actions, but rather demonstrated that it was time for the Court to recognize a new tort.

Before concluding whether a tort of harassment was applicable in this case, Justice Feasby first had to create a definition encompassing the tortious actions consistent with harassment. He defined the requisite components of the tort as follows:

1. engaged in repeated communications, threats, insults, stalking, or other harassing behaviour in person or through or other means;

2. that he knew or ought to have known was unwelcome;

3. which impugn the dignity of the plaintiff, would cause a reasonable person to fear for her safety or the safety of her loved ones, or could foreseeably cause emotional distress; and

4. caused harm.7

Justice Feasby used similar guidelines to those already being used to grant restraining orders on the grounds of harassment in Alberta.

5 Merrifield v Canada (Attorney General), 2019 ONCA 205 [53]

6 Merrifield v Canada (Attorney General), 2019 ONCA 205 [53]

7 Alberta Health Services v Johnston, ABKB 209[107]

Justice Feasby found that Mr. Johnston’s behaviour fell within the definition of the tort. According to Justice Feasby, Mr. Johnston incited violence against the plaintiff through continuous use of pejoratives such as “terrorist”, his mocking of the plaintiff and her family while displaying images from her personal social media accounts, and threatening legal action as well as physical and financial harm. As outlined by Justice Feasby, the defendant’s actions were repeated, known to be unwelcome, reasonably assumed to create fear for the Plaintiff’s safety or the safety of her family, and caused a substantial amount of harm to the plaintiff’s reputation.

Before concluding, it is important to explain the Court’s decision that Alberta Health Services’ harassment claim against Mr. Johnston could not stand. On this claim, Justice Feasby found that, although technically independent, AHS acts as a body of the government. Therefore, though Mr. Johnston repeatedly made defamatory and factually inaccurate statements about AHS, it was within his Charter-protected right to freedom of speech to speak out against a government institution. Because the other plaintiff was an un-elected AHS official (who, in pre-pandemic times, was largely anonymous to the general public) Mr. Johnston’s defamatory statements made against her were not protected by his freedom of speech rights. Accordingly, the Court ordered Mr. Johnston to pay only the individual plaintiff considerable general and aggravated damages on the grounds of defamation and harassment.

The author would like to thank Ethan Winnicky-Hussey for his assistance in drafting this article.

16 Summer 2023

Suite 303, 620 12th Avenue SW Calgary, AB davidkitchenmediation.com 403-620-2194 marneylutzmediation.com 403-612-7214 Connecting People. Finding Solutions. Marney Lutz, Q.C. & David Kitchen are proud members of

Are you using law firm capital to fund disbursements?

Stop hindering the ability to take on new files, manage operating expenses, and invest in growth.

The answer: specialized law firm funding solutions.

Unlike traditional lenders, we fully understand the litigation practice business model. Deferred legal fees, unpredictable file durations and increasingly onerous disbursement requirements result in unique funding challenges that banks cannot address. We can.

Expert search and report funding.

Expert Access combines two essential services for lawyers: sourcing qualified experts using our proprietary Expert Search tool and deferring payment until settlement with no interest for two years.

File specific disbursement funding.

A flexible tool law firms can use to finance any disbursement, on any file, at their discretion. Repayment is deferred until settlement of the underlying file, perfectly in line with a firm’s cash flow.

BridgePoint not only understand the contingency fee business model better than any bank, their disbursement funding solutions are tailor designed for it, with payments perfectly mirroring my settlement cashflow.

Consistently Voted Canada’s Top Litigation Funding Company bridgepointfinancial.ca Whatever your practice size or funding needs, we can help. Learn more and book an information session today: bridgepointfinancial.ca/law-firm-funding | 1 888 800 4966

Tuning the Crystal Ball

The Present and Potential Future of Earning Capacity Claims

By Kyle T.H Smith, C.S Litigator & Mediator Parlee McLaws LLP

Loss of earning capacity is very commonly the biggest swing factor in personal injury cases. It is not always the largest number among heads of damages, but it is very frequently the most variable number, in that it has the highest delta in the result you may receive on a good day in court versus a bad day in court.

Early in my career, I was in front of a Judge who referred to earning capacity claims as being “like gazing into a crystal ball.”

The analogy seemed fitting as these sorts of claims are inevitably about trying to predict the future and, as such, have an inherent level of uncertainty and subjectivity attached to them. While we like to think of the law as being a static predictable entity, the application of the law to contingent or future events leads to a high level of variability in results.

We see this reality in the recent Albertan caselaw on the issue of earning capacity claims, where the results have varied greatly, even in cases where the facts share many similarities.

There have been several very plaintiff-friendly decisions on earning capacity in recent years, with Smith v. Obuck1 being one of the most frequently cited. The case involved a Plaintiff who was 18 at the time of his car accident. The main injury was back pain that was found by the court to be permanent in nature. For general damages, he was awarded $70,000.

In relation to the loss of income claim in Obuck, the court found that the plaintiff was unable perform physical labour or jobs requiring the operation of heavy equipment. The court noted that the evidentiary foundation was lacking in terms of establishing the types of jobs the Plaintiff could do, and what he might earn. The Plaintiff had contemplated going back to school to retrain, and the court found that he was retrainable, and even stated that the Plaintiff, himself, was in control of his own career path.

The generally accepted test in Alberta for earning capacity claims is that there needs to be a “real and substantial possibility” of loss, as opposed to the loss being “mere speculation”2, and the court applied that test in Obuck. The Court found the test had been met, and while the Court was unable to quantify the loss on a mathematical basis, it found that a lump sum award was appropriate. Considering all of the factors in the case, the Court awarded the sum of $250,000 for loss of earning capacity/ competitive advantage.

Iwas in front of a Judge who referred to earning capacity claims as being “like gazing into a crystal ball. . . The analogy seemed fitting as these sorts of claims are inevitably about trying to predict the future

In that case, the court looked into its crystal ball, accepted the Plaintiff’s story about the potential for significant future loss, and despite a relatively low general damages award, and a retrainable Plaintiff, the Court saw in its crystal ball a significant future effect on the Plaintiff’s income, and awarded one of the highest earning capacity awards in recent Albertan history.

On the other end of the scale, the recent case of Jackson v. Cooper3 took a very different approach to the calculation of earning capacity, despite using the same test.

Jackson also involved similar chronic pain issues to Obuck, with the Court finding that the Plaintiff suffered from chronic pain to the neck and back, which was ongoing at trial and was not expected to substantially improve in the future. The Plaintiff was 31 years old at the time of the accident, and was awarded $55,000 in general damages.

18 Summer 2023

1 Smith v. Obuck, 2019 ABQB 593

2 Crisholm v. Lindsay, 2015 ABCA 179 3 Jackson v. Cooper, 2022 ABKB 609

The Plaintiff in Jackson argued that there was a loss of earning capacity due to the inability to perform physical labour. While his primary job was as a contract specialist or contract manager at Shell Canada, the Plaintiff had testified that he had wanted to work in a warehouse to supplement his income, but that the accident had robbed his ability to do so. The Court awarded a past income loss of $10,660, finding that it was reasonable for the Plaintiff to have pursued supplemental income during the COVID pandemic, when his primary income was reduced.

Interestingly, however, in terms of future earning capacity, the Court awarded nothing, finding that Mr. Jackson was capable of doing the essential tasks of his main employment, and stating that “it would be speculative to envisage scenarios in which Mr. Jackson would be suffering from a loss of earning capacity in the future”.

. . .the court looked into its crystal ball, accepted the Plaintiff’s story about the potential for significant future loss, and despite a relatively low general damages award, and a retrainable Plaintiff, the Court saw in its crystal ball a significant future effect on the Plaintiff’s income, and awarded one of the highest earning capacity awards in recent Albertan history.

Jackson applied the same “real and substantial possibility test”, but despite finding a past loss from the inability to do manual labour work, did not find a future loss. This was despite the fact that the disability which caused the past loss remained, and despite the fact that the Supreme Court in M.B. v. British Columbia4 had defined earning capacity claims as being about the “loss of a capital asset”. From the factual findings in Jackson, it was quite clear that the court had found that the plaintiff’s capital asset (his ability to earn an income) had been negatively impacted by the accident.

The contrast between the application of the same test used in Obuck and Jackson is striking. While the facts do vary, there are also a lot of similarities, and yet the results of the earning capacity analysis could not have been more different.

The contrast of those two cases illustrates how variable the 4 M.B. v British Columbia, 2003 SCC 53."

Court’s analysis of these claims can be, despite the same test being applied in both cases. The subjectivity of the crystal ball of each judge can result in widely variable results when applying the current test, due to how much discretion the current test leaves the trier of fact.

This situation raises the question of whether the court will make efforts to further clarify the test. Currently, the “real and substantial possibility” test is rather vague and leaves a lot of room for interpretation. One possible approach for further clarifying the test, however, may be found in the recent BC Court of Appeal decision of Ploskon-Ciesla v. Brophy5

In Ploskon, the court applied a Tripartite Test. The three parts of the test are as follows:

1. Evidence which discloses a potential future event that could lead to a loss of capacity;

2. A real and substantial possibility that the future event in question will cause a loss; and if such real and substantial possibility exists;

3. The value of that possible future loss is assessed, including an assessment of the relative likelihood of the possibility occurring.

The Ploskon framework is not law in Alberta; however, it is now the leading case on earning capacity in BC and, as with many precedents from our neighbours to the West, it is likely inevitable that we will see counsel in Alberta argue for this framework’s adoption in Alberta. It may or may not be adopted here, but the argument will be put forward by someone.

While the Ploskon framework is new, and has not yet been given much judicial interpretation, it seems like this framework would favour Defendants over Plaintiffs. Since it is the Plaintiff’s onus to prove losses, the specific evidentiary requirements of the test would tend to make the Plaintiff’s job more difficult, and would leave less discretion in the hands of the Court to find for a Plaintiff who has not met the specific test.

That having been said, there is also a benefit in knowing the case

5 Ploskon-Ciela v. Brophy 2022 BCCA 217

19 The Barrister

you have to meet in a trial, and whether Ploskon is adopted in Alberta or not, it does provide a useful guide for how a Plaintiff should construct their earning capacity claim.

Probably the most significant aspect of the Ploskon test is the focus on specific future events that could affect earning capacity

The seminal Supreme Court case of M.B. v. British Columbia makes it clear that what is being assessed in a loss of earning capacity case is the capital asset of a person’s ability to earn; however, the same case also assesses the value of that lost asset as being the value of the lost earnings that he or she would have received over time, had the tort not been committed.

The Court has often used the M.B. precedent with a focus on the loss of a capital asset, while sometimes using less scrutiny on the value of the lost earnings. Obuck is one of these cases, as the court overly states that there was insufficient evidence to assess the loss, and instead uses a lump sum assessment meant to be an estimate of the value of the lost capital asset of the Plaintiff’s ability to earn.

In essence, the court in Obuck, and many other cases, has essentially taken a two-part approach. First of all, the court has determined whether the “real and substantial possibility” test has been met. Then, if that test has been met, they assess the loss as best as they can with the evidence before them.

The difference in Ploskon appears to be that the Tripartite Test appears to require a more focused analysis at the first stage of assessing the “real and substantial possibility” test. Instead of being able to vaguely satisfy the court that there is a possibility of loss in the future, the case requires that the Plaintiff more specifically identify and prove (on a balance of probabilities) the actual future events that will cause a loss and analyze the actual likelihood of those possibilities. This process contrasts to the more all-encompassing approach that the Court would often take of rolling all the possibilities together and ballparking a loss number.

new job if the Plaintiff’s current one is lost, the potential of early retirement, or any other specific future events which could result in a loss of income.

Many times Plaintiff counsel will take a less specific approach of focusing on the injuries and essentially asking the court to draw the conclusion that decades of symptoms will inevitably lead to a substantial possibility of loss without putting forth much, if any, specific evidence of how that loss will come to pass. I have seen this strategy work several times, as judges who like a Plaintiff, and think the individual will somehow experience a loss, will utilize the vagaries of the “real and substantial possibility” test to compensate the Plaintiff. That having been said, this approach will not be successful if the Court imports Ploskon, and even if it is not adopted in Alberta, the decision is likely to be referenced by defence counsel, and will likely have persuasive authority, making the Court less likely to accept a poorly defined earning capacity claim.

As such, if you are preparing a case, I would recommend looking at the Tripartite Test in Ploskon, and preparing your earning capacity claim in such a way as to meet that test. Identify the specific events that you think will result in your client’s future loss. Provide evidence for as many possible loss scenarios as you can, while focussing on the most likely ones that you think will persuade the Court. Utilize your experts to provide support to the specific scenarios on which you are focussing your earning capacity claim.

Ultimately, this approach is more likely to satisfy the Court of the legitimacy of your client’s earning capacity claim, and give them the reasoning they need to provide your client with a sizeable award.

Conclusion and Takeaways

Ploskon may get imported into Albertan law, or it may just remain in BC, but for lawyers in Alberta, it still provides some guidelines for how to present an earning capacity claim at trial.

While, as Plaintiff counsel, you may not wish to advocate for the Tripartite Test to be applied in your case, it is advisable to present your case in such a way that you would meet the Tripartite Test if it were applied.

In order to do this, I would recommend focusing your evidence on the specific future events which could cause your client to suffer a future income loss. Such events may include the potential for future surgery, the potential of competitive disadvantage in competing for promotions, the potential of difficulty finding a

20 Summer 2023

V. LAVOIE M.D., F.R.C.S.

Certified Independent Medical Examiner Orthopedic Surgeon Suite 109, 11910-111 Avenue Edmonton, AB 780-483-8311 Fax: 780-930-2121 mvlavoiemd@shawbiz.ca

MICHEL

(C)

Busted? Credit, Loans & Section 89 of the Indian Act

By Hero Laird, Senior Researcher & Casey Caines, Articling Student Wahkohtowin Law and Governance Lodge

The Indian Act - a deeply problematic piece of legislation long overdue for change1 - includes provisions that apply to some Indigenous people, specifically those who fall under the Act's defined categories of “Indians” and bands.2 These categories exclude non-Status, Metis, Inuit Peoples, and settlers. There are a few sections of the Act that are relevant to civil procedure3 and at least as many myths.

A key part of the Act on this subject is Section 89(1) which reads:

Subject to this Act, the real and personal property of an Indian or a band situated on a reserve is not subject to charge, pledge, mortgage, attachment, levy, seizure, distress or execution in favour or at the instance of any person other than an Indian or a band. Notwithstanding subsection (1), a leasehold interest in designated lands is subject to charge, pledge, mortgage, attachment, levy, seizure, distress and execution.

(2) A person who sells to a band or a member of a band a chattel under an agreement whereby the right of property or right of possession thereto remains wholly or in part in the seller may exercise his rights under the agreement notwithstanding that the chattel is situated on a reserve.

This section restricts the seizure of on-reserve property by anyone who does not have Indian or band status, and includes both secured and unsecured property. Such property includes land, chattel and intangibles like wages. Section 89(1) does not apply to any property that is off-reserve, even if the owner resides on reserve and has Indian status.

Created to provide measures against non-Indigenous people acting to erode or exploit reserve land and assets, this section of the Act has since proven to be a challenge for status First Nations interests.4 For example, ordinarily someone living on reserve is precluded from obtaining a mortgage, which can cause significant housing challenges. Creditors cannot receive an order to execute property on reserve, which diminishes the creditor's willingness to provide either secured or unsecured credit to individuals with Status living or Indian Act Bands.

This article gives a brief review of some of the most current issues related to section 89 by identifying and dispelling three myths:

21 The Barrister

1

S.C.L.R.

[

]. 2

117

[1990] 2 S.C.R.

131

SCC

On this topic, see Anna Lund, ‘Judgment Enforcement Law in Indigenous Communities’ (2018) 83

(2d) 279

Lund

Indian Act, RSC 1985, c I-5 [Act]. The terms "Indian" and "band" are considered by many to be outdated and offensive. This article references them only in relation to their defined legal terms. 3 See for e.g. ss 29 and 30. 4 Lund, supra note 1 at 291 and 294. See also Mitchell v. Peguis Indian Band, 1990 CanLII

(SCC),

85 at

for

discussion on the intention of s 89.

Myth #1: Section 89 is being used improperly by Indigenous people

Section 89 acts as a bar to seizure on-reserve, which has been viewed as an unfair action against creditors. However, the Indian Act was created by the Government of Canada without input or partnership from Indigenous Nations.5 Section 89 has been thrust upon those who fall under the Indian Act without consultation or accommodation. Despite this, people with Indian status and band affiliation, bound by the Act, have continued to find ways to assert their best interests — including economic and entrepreneurial interests.

As the Ontario Court of Appeal recently rearticulated in Bogue v. Miracle, section 89 is not intended to confer privileges but rather insulate property interests to prevent dispossession of entitlements.6 The application of the Act is the application of the law, not a way to avoid the law. Unlike other government entities, First Nations are not privy to protections for core funding and instead face the possibility of seizure of all funds upon judgment. Section 89 serves a purpose in providing a way for First Nations to protect their public resources like other governments.7

Unfortunately, even legal writing can miss this point when it characterizes the use of section 89 as a tactic of people with Indian status, or even something to "be concerned" about.8 Even if section 89 was originally motivated by paternalistic attitudes towards Indigenous people in developing the Act, 9 the power imbalances between some large corporations and most First Nations remain relevant. If some Status First Nations people and Indian Act Bands find section 89 useful in protecting their reserve as a "safe-haven,"10 that approach is aligned with the legislation’s intended purpose, and is their prerogative at law.

Myth #2: The primary risk falls on creditors

While the Act has had reverberating consequences throughout Canada, its most significant have been on First Nations themselves.11 Section 89 is no exception. While there tends to be a general feeling by creditors that section 89 leaves them without redress for collection and is thus unfair, there are also legal impacts on First Nation communities.

5 See Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (Ottawa: TRC, 2015) for detailed discussion on the impact of the Indian Act and other intergenerational injustices [TRC].

6 Bogue v. Miracle, 2022 ONCA 672 at para 25 citing Mitchell v. Peguis Indian Band, where La Forest J. explained, at p. 133.

7 See Lund, supra note 1, especially at 314-315 for discussion of Crown immunity from execution and other protections.

8 David Macaulay et al, "Indian Property - Lien and Seizure Restrictions" (January 8, 2010), online: Bennett Jones <https://www.bennettjones.com/Publications-Section/Updates/ Indian-Property---Lien-and-Seizure-Restriction> [Macaulay]. See Lund, supra note 1 at 279, specifically footnote 3 for discussion re: legal writing that limits and potentially distorts understanding in this area. See also e.g. McDiarmid Lumber Ltd. v. God's Lake First Nation, 2006 SCC 58 at 66-68.

9 See Lund, supra note 1 at 291 and 294.

10 Macaulay, supra note 8.

11 See generally TRC, supra note 5.

22 Summer 2023

Pictured: Hero Laird & Casey Caines at a Wahkohtowin Law and Governance Lodge Community Workshop

While some kinds of loans are possible, particularly if the business entity is incorporated, section 89 creates a situation where secured business loans "are impossible when the assets of a person or business are located on reserve.”12 This leaves status Indians living on-reserve in a complex quandary when pursuing business goals. On the one hand, the protections offered by the Act provide an important barrier to the erosion of public services and land on reserve. At the same time, those same protections - or lender’s perceptions of them - destabilize economic investments on reserve, leading to diminished economic opportunities for on-reserve communities and businesses.13 First Nations must navigate risk as they build infrastructure and provide public services to their citizens. Status First Nations business owners need to consider risk when seeking credit, whether from Indigenous or non-Indigenous creditors. Creditors are one actor among many that must assess risks related to section 89.

Myth #3: There is only one way to do business

Proposals to reform section 89 include abolishing the section or creating broad exemptions.14 This kind of thinking can create a false dichotomy: either we have the Indian Act, or reserve land and assets are treated just like assets and land off reserve. However, there are many ways to do business, and Indigenous governments, business owners, and individuals — whether or not the Act applies to them — are finding ways to protect their land and assets, and engage in entrepreneurial activity.15

There are highly successful on-reserve businesses across Canada, despite section 89, such as Tsuut'ina First Nation, who opened the first on-reserve Costco in 202016, Westbank First Nation, who has more than 500 businesses operating on reserve land17, and Enoch Cree Nation, owner and operator of the River Cree Resort and Casino, a casino, hotel and sports and entertainment complex located on-reserve.18

Closing Note

The difficulties with section 89 are a small piece of a larger puzzle. To address them in a meaningful way, we need to look at the bigger picture. For example, multiple legal orders are present in Canada: English, French, and many Indigenous legal orders.19 Attention to this rich legal landscape can provide insight into section 89's history, purpose, and paths forward for this area of civil law. Unlike the Indian Act, any solution that works across Indigenous, provincial, and federal governments must respect Indigenous law with Indigenous people as leaders in crafting it.20

Careful attention to this section, and the nuances of Canada’s relationship to Indigenous people, can also begin to ameliorate access to justice issues. At present, s 89 creates a complex legal framework that often requires specialized knowledge to navigate. With specialized knowledge comes specialized costs, and these costs operate as barriers to Indigenous peoples, bands, and business owners, as well as non-Indigenous creditors and business owners looking to form partnerships or provide credit. Section 89 is a complex area that requires thoughtful reasoning. It requires a deeper understanding of not only the purpose of section 89 but also the nuanced effects it has on creditors as well as Indian Act bands, business owners, and individuals.

With our thanks to Koren Lightning-Earle, Legal Director, Wahkohtowin Law and Governance Lodge, Hadley Friedland Academic Director, Wahkohtowin Law and Governance Lodge and Anna Lund, Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Alberta for their thoughtful reviews. They have much improved our thinking, and this piece, and all errors remain our own.

12 Douglas Sanderson, “Overlapping Consensus, Legislative Reform and the Indian Act” (2014) 39:2 Queen’s LJ 511 at 546.

13 See Lund, supra note 1 at 279 for a discussion of legal risk in this area and perception of that risk.

14 See Adrian Pel, "Reforming Section 89 of the Indian Act: Tinker, Waiver, Soldier (On), Sigh?" (2020) 4:1 Lakehead Law Journal 65 for discussion on benefits and pitfalls.

15 See generally Lund, supra note 1 especially 314-315.

16 See “Costco opens massive new store on Tsuut'ina Reserve, the first on a First Nation in North America” (2020), CBC <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/taza-tsuut-inacostco-calgary-1.5703536>.

17 See Westbank First Nation, “Business and Development” (2023), online: Westbank First Nation <https://www.wfn.ca/business-development.htm>.

18 Enoch Cree Nation, “River Cree Development Corporation” (2023), online: Enoch Cree Nation <https://www.ecncorporate.ca/enoch-corporate-entity/>.

19 See generally Roderick A. Macdonald & Jason MacLean, “No Toilets in the Park” (2005) 50:4 McGill L.J. and Hadley Friedland & Val Napoleon, “Gathering the Threads: Developing a Methodology for Researching and Rebuilding Indigenous Legal Traditions” (2015) 1:1 Lakehead Law Journal 16.

20 For discussion on this point in a legal context, see e.g. A Duty to Act, Remarks of the Honourable Robert J. Bauman, Chief Justice of British Columbia (Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice’s 2021 Annual Conference: Indigenous Peoples and the Law (Vancouver, BC) at para 8 [http://perma.cc/UPX3-V3LN]. See also Frankie Young, “A Trojan Horse Can Indian Self-Government Be Promoted Through The Indian Act?” (2019) 97:3 Can Bar Rev 697 for innovative examples on s 89 reform.

24 Summer 2023

Clae Willis MHA MSc FAAPM CRTWC CCVE CLCP CVRP(F) An experienced, credible, objective expert; serving all of Canada Vocational Analysis & Reintegration Services Life/Future & Attendant Care Cost Assessments Forensic Critiques: Reviews & Tasks Assignments 1-877-CARE PLAN (227-3752) clae@bellnet.ca

Navigating the IME Request Process: A Quick Start Guide for Young Lawyers

By Erica Enstrom Integra

Most trial lawyers will at some point find themselves needing to request an Independent Medical Examination (IME). This process, while integral, can be daunting to younger lawyers. This article is meant to provide guidance, a step-by-step approach, and a checklist to ensure the best evidence-informed outcomes for your case.

What is an Independent Medical Evaluation (IME)?

An independent medical examination is conducted when an individual has been injured or has become ill, and an entity supporting or adjudicating the illness or injury requires third-party documentation to confirm the extent of their impairment and disability, causation, prognosis, treatment and recovery plans, and by extension, the need for some type of benefit. Those benefits may include current, past and future wage loss, current, past and future treatment and supports, and in the case of tort claims, damages for pain and suffering, among other things.

But what is an IME, exactly?

An independent medical examination (also referred to as an independent medical evaluation or IME) is a medical interview and examination, requested by a third party, to be done by a non-treating healthcare professional (examiner) who has no pre-existing relationship with the examinee, and who is therefore independent. IME is often a bucket term to delineate any type of assessment and can include independent medical evaluations conducted by medical doctors (MDs), as well as allied health assessments including: Functional Capacity Evaluations; Future Cost of Care Assessments; In Home or Worksite Evaluations; Vocational Assessments; Neuropsychological and Psychological Evaluations; and many others.

Who Organizes an IME?

An IME agency such as Integra organizes and manages the independent medical examination process from start to finish. The client (for instance, an insurer or a lawyer or their support teams) contacts the IME agency to manage the coordination for an individual claimant or examinee. The IME agency is responsible for finding highly-qualified, independent and suitably trained healthcare professionals located within the examinee’s geographical location. There is a robust credentialing and vetting process that goes on behind the scenes when sourcing healthcare professionals to provide such services.

The IME agency will assist with confirming the appointment details, coordinating necessary ancillary services (such as translation and transportation services), organizing and collating the medical brief from the referral agency, and facilitating the assessment.

Post-examination, the IME agency is responsible for assisting the healthcare professional in providing an appropriate IME report and securely providing that report to the referring client.

What Can You Expect From an IME?

IMEs are conducted by a healthcare professional who has the appropriate credentials, training and experience, to provide an opinion. Generally, the IME agency has a process of credentialing to determine the suitability of healthcare professionals for such work. The healthcare professional will review your medical, social, recreational and occupational (work) history in the report.

The purpose of the independent medical examination is for the healthcare professional to assess your medical circumstances related to your accident, injury, or illness. They will evaluate your current medical symptoms, past and current treatment, and may provide opinions on one or more of the following:

27 The Barrister

• Diagnosis

• Causation

• Residual work capacity

• Housekeeping and home maintenance abilities

• Future treatment needs

• Attendant care and support requirements

• Impairment and disability

• Prognosis

These healthcare professionals may also make recommendations or provide restrictions on your ability to perform daily activities at work, in the case of all IME referral sources, and in the case of litigation for bodily injury claims, recommendations or restrictions for activities at home and in recreation.

The examining healthcare professional will conduct the exam objectively and with respect for all stakeholders . In advance of your appointment, the IME agency will conduct routine procedures such as confirming your identity, identifying the party who requested the IME, and explaining the procedures and reporting that will occur during and after the examination. The healthcare professional will also be able to answer any questions you have before and during the process.

The IME Checklist:

Step 1: Know When to Request an IME

Recognizing when an IME is appropriate is vital. It can be considered in situations where there is a lack of clarity around the issues outlined above, namely diagnosis, causation, residual work capacity, housekeeping and home maintenance abilities, future treatment needs, attendant care and support requirements, impairment and disability, and prognosis.

Step 2: Choose the Right Medical Expert

The choice of medical expert is critical, and it is important to match the right kind of expert to the injury or illness in question. Ensure that the expert has the correct qualifications, experience, and reputation. It is important to work with an IME provider who can manage the process smoothly and transparently – providing you with guidance, advice and support along the way.

Step 3: Preparing the Letter of Instruction

When instructing an IME, clarity is crucial. Your letter of instruction to the medical expert should include:

• A brief summary of the case.

• Detailed information about the examinee’s medical history.

• Any specific questions you want the expert to answer.

• Any deadlines or legislative requirements the expert should know.

Step 4: Preparing the Examinee

Ensure that the examinee understands the purpose of the IME and that they are aware it is not a treatment relationship. Make sure they have a clear picture of the process and what to expect, how long the appointment will take, any information that may be requested, etc.

Step 5: Review the IME Report Thoroughly

Once you receive the IME report, review it carefully to ensure it answers all your questions. If anything is unclear, you can typically ask the IME agency for clarification.

Checklist for Requesting an IME

Here is a handy checklist to guide you through the IME request process:

1. Case Evaluation: Is an IME necessary? Does it have the potential to resolve a dispute or provide critical information about the examinee’s circumstances?

2. Choosing an Expert: Is the expert appropriate for the type of injury or illness? Do they have the right qualifications, experience, and reputation?

3. Letter of Instruction: Have you included all the necessary information? Is your summary of the case clear? Have you included all relevant medical history and posed specific questions?

4. Examinee Preparation: Does the examinee understand the purpose and process of the IME?

5. Review of IME Report: Does the report answer all your questions? Is anything unclear or in need of further clarification?

Throughout the IME process, your biggest asset as legal counsel is partnering with an IME provider that has decades of experience and understands how to ensure that the right medical experts are selected, the exam/assessment run smoothly, and that your reports are informative, accurate, and effective.

28 Summer 2023

ACTLA MEMBERS, MEET

ERICA ENSTROM

Co-Owner and Managing Director, British Columbia & Alberta

Erica is known for building strong, lasting relationships based on mutual trust and solid advice. She works transparently and honestly to connect assessment and rehabilitation allies. With over 20 years experience in the medical assessment industry, she is a court-qualified medical legal expert, clinical consultant, and evaluator in the areas of functional capacity and cost of future care.

OUR SERVICES

Our core assessment services include:

• Independent medical evaluation

• Psychological and neuropsychological assessment

• Vocational rehabilitation evaluation

• Functional capacity evaluation

• In home assessment

• Cost of future care assessment

THE INTEGRA WAY

Integrity

We are a business that places integrity at the foundation of how we work.

Our core consultation service include:

• Expert opinion review and responsive opinions

• Expert testimony preparation and delivery

• Clinical triage of complex medical issues

• Brief medical review of standard of care and causation matters

• Cognitive functional assessment

• File Reviews

Support

We understand our role supporting, guiding and advising throughout client relationships.

Accountability

We are focused on trust-based relationships that deliver transparency and fairness.

WE ARE HERE TO GUIDE AND SUPPORT YOU CALGARY | EDMONTON | KELOWNA | VANCOUVER | TORONTO | HALIFAX t 403.621.1179 e erica@integraconnects.com w www.integraconnects.com t 403.621.1179 e erica@integraconnects.com Learn more about our capabilities and our roster of experts and professionals at www.integraconnects.com

In recent years, courts have increasingly been asked to provide adjudication on circumstances involving various forms of harassing behaviour. In civil matters, this has given rise to case law considering how tort law might best respond to claims of that nature. One potential response that has received some judicial treatment is the development of a new tort of harassment.

Courts across Canada have so far taken a very cautious approach to developments in the law related to civil harassment claims. In most jurisdictions, the tort is not expressly recognized, and some decisions have expressed doubts about whether creation of a separate tort is appropriate.1

In Alberta however, lower court decisions have favoured adoption of a tort of harassment, and have provided some guidance on its contours. This development in Alberta has evolved out of cases dealing with the availability of civil restraining orders to prohibit harassing and vexatious conduct, and coincides with tentative consideration of other new, related torts in Alberta and elsewhere in Canada.

not only the right to live in safety but also the right to be free from vexatious or harassing conduct. A citizen who has been plagued by harassing behaviour but told that the court cannot do anything to protect them from that behaviour would be further vexed upon learning that courts protect themselves from vexatious litigants by making orders restricting access of those litigants to judicial process; vexatious litigant orders do not depend on evidence that courts fear for the safety of the judges.

[38] Do citizens have the right to be free from vexatious conduct by another?

[39] I have concluded that there is such a right. The Criminal Code criminalizes certain types of harassment.

Civil Recourses for Harassing Behaviour in Alberta

One of the earlier Alberta decisions considering the ability of civil courts to provide redress for harassing behaviour, as separate from concerns for physical safety, is Boychuk v Boychuk, 2017 ABQB 428, 60 Alta LR (6th) 149. In that family law matter, the wife sought extension of a civil restraining order she had obtained against the husband. Veit J found that the wife had not fully informed the chambers judge of all relevant facts at the time of obtaining the original order and there was in fact no objective basis to justify the restraining order, which was consequently set aside. In the course of her reasons, however, Veit J opined on the court’s power to provide protection from harassment. She concluded that judicial authority to grant restraining orders against unwanted behaviour did not derive only from statute and was not limited to circumstances of physical violence or fear for physical safety:

[37] […] [A] superior court has inherent jurisdiction and is not limited to any statutory standard; it is entitled, and indeed expected, to administer equity, i.e. to do what is fair as between litigants. The rights of citizens include

1 See for example Merrifield v Canada (Attorney General) (2019), 145 OR (3d) 494, 2019 ONCA 205, leave to appeal refused [2019] SCCA No 174, holding that the trial judge erred by recognizing a tort of harassment; Ilic v British Columbia (Minister of Justice), 2023 BCSC 167, [2023] BCJ No 200, observing that “There is no recognized tort of harassment” (at para 196).

[40] It is excessively rare for there to be criminal redress for conduct which cannot also be dealt with civilly. In my respectful view, a person who repeatedly communicates with another after having been told that the communications are unwelcome is harassing the other person. That unwelcome communication should, and can, be stopped. [Emphasis added]

Following Boychuck, the ability of civil courts to provide protection against behaviour that did not create a fear for physical safety, but was nonetheless harassing and vexatious, was recognized in other decisions. In Muslim Counsel of Calgary v Mourra, 2018 ABQB 118, [2018] AJ No 391, which concerned a dispute between a not-for-profit organization and one of its former members, Nixon J affirmed that threats of violence or fear for physical safety were no longer required in order for courts to issue a restraining order. A risk of harassing, intimidating, or molesting behaviour that was likely to continue was sufficient:

70 […] there is no longer a general requirement for an applicant to demonstrate an objective fear for their safety before a common law restraining order can be granted. While older jurisprudence required that prerequisite, more recent jurisprudence has lowered the threshold: Boychuk v Boychuk, 2017 ABQB 428 at paras 50-52 [Boychuk]; see also C (AT) v S (N), 2014 ABQB 132 at para 18.

31 The Barrister

[…] […]

"Anapplicantnolongerneedstodemonstrateanobjectivefear fortheirsafety.Rather,itissufficienttodemonstratealegitimate riskthattheharassingintimidating,molestingorthreatening behaviourwillpersist."

72 Given the lower threshold in the recent jurisprudence, an applicant for a permanent order need only demonstrate that there is a legitimate risk that the respondent's harassing, intimidating, molesting, or threatening behaviour will continue. To emphasize this point, impugned behaviour need only be disruptive; it is not a requirement that it be violent: […]

73 […] we are in a new era. As stated above, the Courts are moving to a lower threshold in certain cases.

74 With that context in mind, I further note that a superior court has the jurisdiction to grant injunctions to effect justice. This jurisdiction exists even when there is no underlying threat of violence: […]. [Emphasis added]

The ability of courts to issue restraining orders to prevent harassment was also affirmed in Sun v Huang, 2021 ABQB 782, [2021] AJ No 1338, where Armstrong J reiterated the language from Muslim Council indicating that the applicable test no longer hinged on the applicant showing a fear for physical safety:

13 The test for a restraining order has evolved somewhat since the decision in P(R). An applicant no longer needs to demonstrate an objective fear for their safety. Rather, it is sufficient to demonstrate a legitimate risk that the harassing intimidating, molesting or threatening behaviour will persist. As the Court said in Muslim Counsel of Calgary v Mourra, 2018 ABQB 118 at para 72, “. . .impugned behaviour need only be disruptive; it is not a requirement that it be violent. . .”. [Emphasis added]

In Sun, Armstrong J also considered the applicant’s claim for tort damages related to the harassing behaviour, which had been framed under the tort of intentional infliction of mental suffering. Armstrong J found that in the absence of a provable mental injury resulting from the alleged conduct, tort damages were not available pursuant to that particular tort, which did not extend to behaviour causing annoyance or even alarm:

10 Mr. Sun claims damages for intentional infliction of emotional distress or, as the tort is more commonly known, intentional infliction of nervous shock. In the recent decision of Dubé v RCMP, 2021 ABQB 451, the elements of the tort were succinctly summarized at para 157:

The elements of the tort of intentional infliction of harm (also known as intentional infliction of nervous shock or mental suffering) are: (1) flagrant or outrageous conduct; (2) calculated to produce harm;

32 Summer 2023 […]

and (3) resulting in a visible provable illness: […] A mental injury is a serious and prolonged disturbance going beyond the annoyance, anxieties and fears that come with living in a civil society. The court may consider factors such as the seriousness of the impairment, the length of the impairment, and the nature and effect of any treatment in order to distinguish between upset and injury: Mustapha v Culligan Ltd, 2008 SCC 27 at para 9, Saadati v Moorhead, 2017 SCC 28 at para 38.

11 Mr. Sun has not established the required elements of the tort. While he was clearly annoyed, or may have even been alarmed, by Ms. Wang's correspondence and by his interactions with Ms. Wang and Mr. Huang, his evidence does not disclose any actual injury, mental or otherwise, attributable to the actions of Ms. Wang or Mr. Huang. In the absence of any injury, Mr. Sun's claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress must fail. [Emphasis added]

The inadequacy of existing categories of tort law to address certain forms of unwanted conduct other than physical violence was acknowledged in ES v Shillington, 2021 ABQB 739, 34 Alta LR (7th) 324. The plaintiff in that case sought recognition of a new tort of public disclosure of private facts in response to the defendant’s ongoing campaign of publishing private images of her on the internet. Inglis J found that the circumstances of the injury suffered by the plaintiff, which were “appalling and warrants a significant response from the court” (para 115), met the criteria set out in Nevsun Resources Ltd v Araya, 2020 SCC 5 at para 237, 443 DLR (4th) 183 for recognition of a new tort, and awarded general damages of $80,000 and punitive damages of $50,000, in addition to a restraining order. In determining that recognition of the new tort was appropriate, Inglis J noted the uneven development of new torts addressing related types of behaviour, including harassment, in jurisdictions across Canada (paras 36 et seq). A critical consideration in those cases, which Inglis J found was also present in the instant case, was the absence of any tort or other remedy that sufficiently addressed the harm:

63 The existence of a right of action for Public Disclosure of Private Facts is thus confirmed in Alberta. To do so recognizes these particular facts where a wrong exists for which there are no other adequate remedies. The tort reflects wrongdoing that the court should address. Finally, declaring the existence of this tort in Alberta is a determinate incremental change that identifies action that is appropriate for judicial adjudication.

The reasoning from Shillington was relied on in Ford v Jivraj, 2023 ABKB 92, [2023] AJ No 182, in which the defendant applied to set aside a restraining order issued against him, as a corollary to an action instituted by the plaintiff alleging defamation and seeking to prohibit the defendant from publishing any further comments about her. While the plaintiff did not specifically seek recognition of a tort

33 The Barrister

Thelawofdefamation providessome recourseforthe targetsofthiskind ofconduct,but thatrecourseisnot sufficienttobring theconducttoan endortocontrol thebehaviourofthe wrongdoer.

of harassment, Graesser J opined that there was good justification for its existence, and considered that it could be relied upon as a basis for the restraining order granted in the case before him. After noting that “[t]he common law in Canada has been slow to recognize a tort of harassment” (para 255), Graesser J sought to extend the reasoning from Shillington:

263 In Alberta, Justice Inglis awarded damages against a defendant for claims including harassment in ES v Shillington, 2021 ABQB 739. I agree with her analysis and conclusions in that case and recognize that this new tort now has a toe hold in Alberta. Her award did not depend entirely on harassment.

264 I feel compelled to say that I am surprised by the pushback on the development of this potential tort. I fail to see what competing interests or rights need to triumph over an individual's privacy interests, as opposed to their being a reasonable balance.

[…]

271 Harassment appears to me to be an obvious invasion of a person's privacy interests, and to date has been subsumed (if at all) in the recognized tort of intentional infliction of mental suffering. That itself is a 20th Century tort.

272 The criminal law has recognized harassment as a criminal offence since 1993.

[…]

274 "Fearing for safety" in section 264 is not restricted to physical safety and has been interpreted to include psychological safety. "Injury" in section 372 is similarly not limited to physical injury and has been interpreted as including psychological and financial safety.

[…]

276 I fail to see that if a deliberate course of harassment is a criminal offence why it is also not a civil wrong. In my view, it is time for the civil law to catch up to the Criminal law and recognize harassment as a tort. [Emphasis added]

Most recently, the tort of harassment was expressly stated to be part of the law in Alberta in Alberta Health Services v Johnston, 2023 ABKB 209, [2023] AJ No 373. The defendant in that case was found to have engaged in an ongoing vitriolic campaign of defamatory remarks and threats made against AHS employees generally, and in particular the co-plaintiff Nunn, on his online talk show, in interviews with the press, and through other media. Feasby J awarded Ms Nunn $400,000 in general damages, which included $100,000 spe-

34 Summer 2023

cifically for the tort of harassment, and $250,000 in aggravated damages, as well as a permanent restraining order. Feasby J noted that restraining orders addressing harassment are regularly issued by the courts but typically not reported, and held that a development in the law that would establish a framework to guide what courts were already doing was needed.

Feasby J held that the essence of tortious harassment is “repeated and persistent behaviour” that “creates an oppressive atmosphere”. He set out a four-element test for determining whether a defendant has committed the tort of harassment:

98 The fact that this Court regularly grants restraining orders to address harassment indicates that harassment is a justiciable issue. A recognition that the wrong that is being restrained in these cases is tortious harassment is an incremental change in the law. The recognition of the tort of harassment, in turn, allows damages to be awarded in circumstances where the Court now can only issue restraining orders. Arming the Court to redress the problem of harassment by adding the power to award damages in appropriate cases is long overdue.

ment as follows. A defendant has committed the tort of harassment where he has:

1. engaged in repeated communications, threats, insults, stalking, or other harassing behaviour in person or through or other means;

2. that he knew or ought to have known was unwelcome;

3. which impugn the dignity of the plaintiff, would cause a reasonable person to fear for her safety or the safety of her loved ones, or could foreseeably cause emotional distress; and

4. caused harm.