Barrister the

• Interest rate DECREASES at the two-year mark

• Legal fees & disbursements always take priority

• Approval within 24 hours

• No hidden fees or recurring charges

• Flat $250 administration fee

• No complicated application forms

• Sustainable and responsible lending decisions

We’ve got your back, so you can

Advocating for a strong civil justice system that protects the rights of all Albertans.

2023-24 BOARD MEMBERS

Chair: Mike McVey

Past Chair: Owen Lewis

Vice Chair: Jillian Gamez

Secretary: Laura Comfort

Treasurer: Travis Bissett

Members-at-Large:

Joseph A. Nagy

Clifford Headon

Dana Neilson

Geographical District Representatives:

North West: Leah Paslawski

North East: Waverly Mussle

Edmonton: Karamveer Lahl

Calgary: Peter Cline

Central: Evan Morden

South East: VACANT

South West: Thomas Kannanayakal

ACTLA STAFF

Executive Director

Joy Jeong | executivedirector@actla.com

Communications and Events Services

Administrator & Editor-In-Chief, The Barrister

Nash Calvert | communications@actla.com

Finance & Member Services Administrator

Lochlin Zhao | membership@actla.com

PAST CHAIRS

Owen Lewis - 2023-24

Angela Saccomani, KC - 2022-23

Maia Tomljanovic 2021-22

Jackie Halpern, KC, 2020 - 21

Shelagh McGregor, 2019-20

Mark Feehan, 2018-19

Michael Hoosein, 2017-18

Maureen McCartney-Cameron, 2016-17

Nore Aldein (Norm) Assiff, 2015-16

Craig G. Gillespie, 2014-15

Donna C. Purcell KC, 2013-14

George Somkuti, 2012-13

Constantine Pefanis, 2011-12

James M. Kalyta, 2010-11

James D. Cuming, 2009-10

Richard J. Mallett, 2008-09

Arthur A.E. Wilson KC, 2007-08

Walter W. Kubitz KC, 2006-07

William H. Hendsbee, KC, 2005-06

Kathleen A. Ryan KC, 2004-05

Ronald J. Everard KC, 2002-04

Stephanie J. Thomas, 2000-02

James A.T. Swanson, 1998-2000

Gary J. Bigg, 1996-98

Stephen English KC, 1994-96

Anne Ferguson Switzer, KC, 1992-94

Terry M. McGregor, 1990-92

J. Royal Nickerson KC, 1988-90

Derek Spitz KC, 1986-88

The Summer Edition of The Barrister is coming!

We are searching for tips, tricks, and stories of you using technology to improve your work efficiency, or that of your firm!

Whether you are an experienced trial lawyer, a law student, or an expert witness, contact communications@actla.com to contribute an article.

Articles should be between 500-2500 words. Longer research articles are accepted as well.

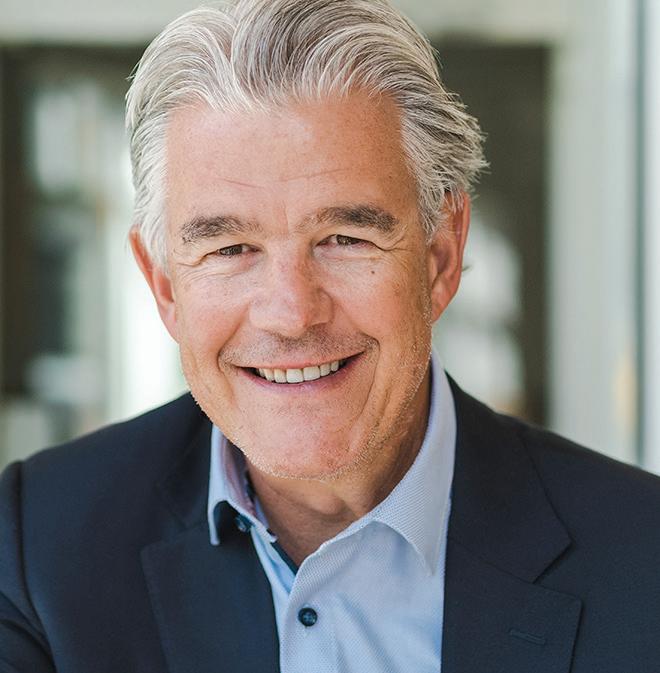

Iampleased to assume the role of Chair of the Alberta Civil Trial Lawyers Association (ACTLA). It is an honor and a privilege to be leading this organization which has an important role in protecting the rights of Albertans and ensuring that the civil justice system meets the needs of those Albertans accessing that system. I am committed to working with the ACTLA Board, ACTLA Members and ACTLA’s Executive Director and staff to continue the fantastic work that ACLTA has done in the past and will continue to do in the future.

As we move forward, ACTLA will continue to advocate against no-fault or hybrid no-fault insurance which would have a detrimental effect on the rights of injured Albertans. ACTLA’s advocacy in this respect is particularly important given that the Alberta Government is currently considering making significant changes to automobile insurance in Alberta and moving away from a tort system and towards a no-fault system.

ACTLA

ACTLA

We will continue to ensure that we advocate in favor of injured Albertans and to work with the Alberta Government and other stakeholders including the medical community, to ensure that the many flaws of no-fault insurance are highlighted. In addition, we will work hard to ensure that Albertans are aware of the possible changes and the negative impacts these changes will have on their civil rights. We will encourace Albertans concerned with the removal of their civil rights to voice their opinions to their MLAs and other government officials as well. ACTLA advocacy efforts will be essential to ensure that nofault or hybrid no-fault insurance does not become a reality in Alberta.

Throughout this year, ACTLA will continue with efforts to increase membership. Not only does a large membership base ensure the continued success of the organization, a large membership base has a large voice which is essential for advocacy efforts. I believe that ACTLA has an opportunity to build membership through working with non-ACTLA members of the civil bar in advocacy efforts for improvements in the civil justice system as a whole. Collaboration is an effective tool to increase membership. In addition, this may build membership by allowing ACTLA an opportunity to work and build relationships with lawyers who practice in areas which were not traditionally an area of focus for past ACTLA members.

As always, ACTLA will continue with its efforts to assist members and non-members with continuing legal education through in-person seminars and online webinars. ACTLA recognizes the importance of ensuring that lawyers have access to current, high-quality content to assist lawyers with providing exceptional services to their clients. In my view, this is important for ACTLAs continuing success as it raises ACTLA’s profile in the legal community and can also help accomplish the goal of increasing membership.

Finally, I want to take the opportunity to thank all of our outgoing volunteers for their dedication to ACTLA over the years. I would also like to thank our incoming volunteers for their willingness to put their time and talents to work in favor of ACTLA’s goals. I look forward to working with you all in ensuring ACTLA’s continuing success.

Yours truly,

Mike McVey

Are you a new parent, or soon to be new parent, in the legal profession in Edmonton?

Join Returnity Yeg, a "Baby & Me" group in Edmonton!

Jillian Gamez and Sasha Lallouz, lawyers in private practice in Edmonton, met at a local Baby & Me group at Nest Integrative Wellness while on maternity leave in 2023. In addition to all things new parent related, they found themselves chatting about returning to lawyering in private practice as parents, and juggling their new bundles of joy into their daily routine when back at the office. After learning about Calgary's Returnity YYC Baby & Me group, a group for lawyers in Calgary with over 40 participants, Jill and Sasha decided to pilot Edmonton's Returnity chapter.

Babies are welcome!

If you are a lawyer in Edmonton who will be on parental leave during that time, and are interested in joining Returnity Yeg, please email returnityyeg@gmail.com to indicate your interest and receive further information. As this is a pilot program, Returnity Yeg is considering the possibility of accommodating zoom attendance for flexibility and to include lawyers outside of Edmonton in northern Alberta.

For sponsorship inquiries to assist with costs, such as meeting space rental and speakers, please email returnityyeg@gmail.com for more information. We thank you in advance for your interest.

Joy Jeong, Executive Director ACTLA

Joy Jeong, Executive Director ACTLA

The passing of March is a transitional time for our association as it marks the changing of our board. With that being said, I would like to start this letter with a tremendous thank you to the 2023-2024 board for all their hard work and service over the last year. I would like to extend an extra thank you to Owen Lewis for his time as the ACTLA Chair.

Looking forward, with Mike McVey taking over as the ACTLA Chair, I am hopeful and excited for the coming year and all we can accomplish.

Already 1 quarter into the year, our main event of the first half of the year is fast approaching. We have the Plaintiff’s Only Seminar coming up this May, and I’m looking forward to the great speakers we have lined up. I hope to see many of our members attend our first in person event of the year.

Additionally, we are already well into our lobbying efforts for the FAIR Campaign for this year. You may have already seen our commercials aired on Hockey Night in Canada, as well as heard our commercials on radio stations such as 630 CHED. We are maintaining our close relations with government, and continuing to advocate against no-fault insurance in Alberta. Thank you to all those who have donated so far to our efforts this year. Without the support of our donors, we would not be able to continue to advocate for our members and for Albertans. Your contributions are crucial to our work, and every single dollar counts. So thank you to all those who donate, and to those who continue to share our message and spread ACTLA’s reach.

Coming up soon, we also have our 2024 membership renewals, and members can expect notices for renewal to begin going out in May. We would love to continue growing our ACTLA Membership, so we encourage our members to invite their colleagues to join our association.

As always I invite you to reach out with questions, comments and suggestions (or even to just say hello). I can be reached directly at executivedirector@ actla.com.

Sincerely,

Joy Jeong Executive Director

Aswe stride into the second quarter of 2024, I am pleased to bring you an update on behalf of the Alberta Civil Trial Lawyers Association (ACTLA) regarding our membership and financial standing.

The heart of any association lies in its members, and I am delighted to share the exciting news that our membership has experienced a significant surge over the past year. From May 2023, we have seen a remarkable growth trajectory, transitioning from just scraping by with 350 members to nearly reaching the 500-member milestone. This accomplishment is a testament to the concerted efforts of our dedicated team, including our communications coordinator Nash, executive director Joy, and myself. Through strategic outreach initiatives and enhanced communication channels, we have successfully attracted new members and strengthened our community of legal professionals dedicated to civil trial practice in Alberta. We hope to bring membership figures above 550 before the next annual renewal date. Membership for existing members will be expiring on May 31st, 2023, so I would like to gently remind everyone to consider renewing soon.

In addition to our flourishing membership base, I am thrilled to report on the robust financial health of ACTLA. Thanks to the generosity and support of our members, we have received over $250,000 in donations, which have played a pivotal role in sustaining and advancing our mission. We are deeply grateful for your contributions, which have enabled us to continue providing valuable resources, advocacy, and networking opportunities for our members.

Looking ahead, we aspire to build upon this success and aim to surpass the milestone set by our previous fundraising efforts. Achieving this goal would not only signify a greater financial contribution towards our initiatives but also reflect the unwavering commitment and solidarity of our members towards the advancement of civil trial practice and access to justice in Alberta.

Rest assured, ACTLA is in a position of strength when it comes to our finances, and we are committed to upholding sound fiscal management practices to ensure the longevity and sustainability of our association. With prudent planning and execution, we are confident in our ability to maintain our current financial standing and continue serving the needs of our members effectively

I extend my heartfelt appreciation to each and every one of our members for your unwavering support and dedication to the Alberta Civil Trial Lawyers Association. Together, we have achieved remarkable milestones, and I am excited about the journey ahead as we continue to grow and thrive as a community.

Should you have any questions or require further information, please do not hesitate to reach out to me or our team. Thank you for your continued commitment to ACTLA.

Warm regards,

Lochlin Zhao Finance and Membership Services Alberta Civil Trial Lawyers Association

As my term as Chair draws to a close, I would like to convey how deeply honoured I am to have been able to serve on this Board alongside such incredible people. I am privileged to have served a membership dedicated to preserving the rights of innocent injured victims and tirelessly advocating for access to justice.

At the start of the year our Board set out with three main objectives: to increase membership, to offer meaningful educational opportunities, and, finally, to continue to advocate against changes to Alberta's automobile insurance regulations which would see a no-fault or hybrid no-fault system implemented in Alberta.

Throughout the year, our association diligently tracked progress, challenges, and achievements that ensured transparency and guided our actions. Despite facing numerous obstacles, our membership numbers increased by 15% where we currently have 456 paid members. We anticipate that this number will continue to increase on an annual basis as we have developed relationships at the University of Alberta, created inroads at the University of Calgary, and have expanded membership to numerous firms who were previously not members of our organization.

The Seminars Committee did an incredible job presenting numerous online seminars throughout the year and in-person conferences. The final in person Masterclass conference had amazing speakers and was well attended, considering post-Covid conditions, and will certainly be a springboard for the in-person seminars which will take place in 2024. The feedback received was universally positive.

2023 saw the election of a new UCP Government in Alberta and ACTLA has been faced with the challenge of countering the advocacy efforts of the IBC, who are seeking to further limit the rights of injured Albertans, which seems to arise every time the new provincial government is elected. ACTLA remained steadfast in advocating for the rights of injured Albertans. However, our efforts are particularly tested by the looming threat of the proposed no-fault or hybrid no-fault insurance systems. These proposals, actively promoted by industry stakeholders and supported by lobbying efforts, pose significant risks to the rights of innocent victims and the integrity of our justice system. With a report expected soon, which will likely tout the advantages of systems in jurisdictions like New Jersey and New South Wales, our advocacy efforts on behalf of injured Albertans will continue to be tested.

However, ACTLA can take some credit for the profit cap on insurance companies which was implemented by the Alberta Government as the first phase of their policy initiatives. This comes directly from the advocacy efforts of ACTLA members and is a testament to our standing as a stakeholder in these discussions. We hope to be included as a relevant stakeholder in any further discussions of legislative changes that the Alberta government may consider. It appears that ACTLA stands alone as one of the only consumer advocates in relation to private passenger automobile insurance in Alberta.

On a personal note, I would like to extend heartfelt gratitude to Angela Saccomani, Past Chair, for her invaluable assistance, guidance, and unwavering dedication to the mission of the association. Angela's leadership and the leadership of the Chairs before her have been instrumental in steering the organization through challenges and fostering a culture of excellence. I further extend my appreciation to the Board members for their unwavering commitment, diligence, and perseverance throughout the year. Their collective expertise, passion, and tireless efforts have been instrumental in advancing the goals of the association. Being a member of the Board entails more than simply attending board meetings, as each member is an advocate for the ideals of ACTLA and we have tasked the Board members with additional work during these challenging times.

Furthermore, I express gratitude to all Committee members for their invaluable contributions. Special mention goes out to the Barrister Committee for publishing engaging and educational publications and dealing with the challenges of going digital. Further mention goes out again to the Seminars Committee for coordinating the educational offerings this year and securing world-class speakers for the in-person events. Finally, thanks goes out to the membership of the Task Force Committee, many of whom spent countless hours educating medical professionals, legal professionals, and government officials on the negative implications of the IBC's proposals and of no-fault systems generally. No doubt we will require the continued efforts of all these Committees to accomplish our association's goals in the coming years.

A special acknowledgment is also due to our Executive Director, Joy Jeong, whose organizational skills, leadership, dedication, and tireless efforts have been instrumental in guiding the association forward. I extend my gratitude to Joy, as well as her staff, Nash Calvert and Lochlin Zhao, for their hard work and contribu-

tions throughout the year. As I step down from my role, I extend warm congratulations and best wishes to Mike McVey as the new Chair of the Alberta Civil Trial Lawyers Association. I have full confidence in Mike's leadership abilities, dedication, and commitment to upholding the values and mission of the association. I am confident that under his guidance, the association will continue to thrive and remain at the forefront of educating our members, advocating for injured Albertans, fighting against destructive tort reform, and ensuring access to justice for all Albertans.

In closing, I am immensely proud of the accomplishments and progress achieved by the Alberta Civil Trial Lawyers Association in its relatively short 36-year history, and I am humbled to have been a small part of it. As we look ahead to the future, I am confident that our collective efforts will continue to make a meaningful impact in the pursuit of justice and fairness for all Albertans.

Ithink it is safe to say that Spring has officially sprung - despite the erratic mood swings of our province's weather this year. In the spirit of spring and renewals, I would like to officially welcome our new Board to their roles and thank the dedicated members of the Editorial Board for their assistance in putting together the Barrister.

While the previous edition was the largest ACTLA has ever prepared, this edition is decidedly smaller. We elected for a smaller edition to give ourselves time to recoup from the previous edition while also preparing content in advance for later editions. Rest assured, this edition may be smaller but it is no less dense.

In honour of the new year, ACTLA once again hosted our Case Law Review webinar, one of ACTLA's highest-attended educational programs ever. Laura Comfort has provided The Barrister with some additional case highlights that were not covered in the webinar - and the webinar materials and recordings are now available for purchase at the ACTLA we store for further review. If that's not enough for you, this edition's Rules Summaries, graciously provided by JSS Barristers, should be a veritable feast for your review.

Nash Calvert Editor-in-Chief, The Barrister Communications & Event Services Admin, ACTLA

Nash Calvert Editor-in-Chief, The Barrister Communications & Event Services Admin, ACTLA

In the previous edition, we set out to frame the discussion around No-Fault Insurance and proactively define many of the models (including British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Australia's New South Wales) that we know are referenced during these discussions. In this edition, I am happy to report that we were able to field an article from the Ontario Trial Lawyers Association discussing how No-Fault has affected their province. As a result, I am confident that these two editions taken together will provide a robust framework for our continuing discussions with the Alberta Government as we continue to advocate against No-Fault systems.

The final two articles in this edition discuss the brain. Priscilla Cicek's Case Law Corner submission for this edition focuses on aneurysms and stroke, particularly their affects on individuals' mental state from both a medical and legal perspective. From Bottom Line Research, the article "Assessing Remoteness in Family Members Claims of Psychological Injury" will be the perfect resource for determining if a psychological damages claim by an indirect plaintiff is likely to be successful or not.

While the content of this Barrister edition may be reduced from the previous, ACTLA is in no way cutting back on the opportunities for you to continue your education. This year's Plaintiff's Only Seminar will have been officially announced by the time this makes its way to you, and we look forward to hosting you and our roster of speakers at the Sandman Signature Downtown Edmonton on May 28th and The Dorian/Mariott Courtyard Downtown Calgary on May 30th.

As always, we are constantly seeking new contributors and advertisers for The Barrister - if you have an article, research paper, or any other contribution you feel would be of value to our publication, please contact communications@actla.com to send it in!

Sincerely,

Nash Calvert Editor-In-Chief & Communications/Event Services

In the midst of ongoing discussions around auto insurance reform in Alberta, a recent poll has shone a light on the attitudes of Albertans. Conducted by Janet Brown Opinion Research and commissioned by the advocacy coalition Fair Alberta Insurance Regulations (FAIR Alberta), the findings reveal a significant preference among Albertans for the existing "at-fault" insurance model over the proposed "no-fault" system. This article delves into the intricacies of the poll and digs into what is motivating opinions and their implications for future insurance policies.

Publicly released in early April, the survey outcomes are eye-opening. A commanding 63% of Albertans have voiced their support for the at-fault insurance system. This figure starkly contrasts with the mere 25% favoring a shift towards a no-fault system, alongside 4% showing interest in a mixed system, and 8% remaining undecided. This pattern of preference not only underscores a significant resistance to change but also mirrors sentiments captured in a similar 2021 survey, highlighting a consistent provincial stance over time.

Janet Brown, the pollster who conducted the research, pointed out the significance of these results, stating, "Our data shows a majority of the population is not only familiar with the current system but also prefers it over the alternative no-fault model.” This preference signals a deep-seated comfort and satisfaction with the status quo, wherein the financial responsibility for an accident falls upon the at-fault party, aligning with the principles of accountability and justice.

The survey also explored perceptions of fairness related to the no-fault insurance model, particularly its approach to treating responsible and non-responsible parties equally and its prohibition on suing at-fault drivers. The feedback was overwhelmingly against these aspects, with 61% opposing the equal treatment of victims and at-fault drivers, and 71% disapproving of the restriction on legal actions against at-fault individuals.

Jackie Halpern KC, a spokesperson for FAIR Alberta, emphasized the importance of accountability, stating, "Albertans are clearly saying victims of accidents caused by bad drivers should have the right to hold the responsible parties accountable – that’s just an Alberta value – personal responsibility.”

Despite the resistance to a no-fault system, there is a desire among Albertans for insurance reform, but they say it should be specifically aimed at reducing premiums within the at-fault framework. 68% of respondents advocated for government to explore reforms within the at-fault framework and only 16% said the government should considering no-fault systems as a solution. Halpern criticized the no-fault approach for its potential to diminish consumer power, stating, “A no-fault system takes power away from consumers and puts decisions solely in the hands of insurance companies.” FAIR Alberta continues to advocate for reforms strategy that promote affordability, accountability, and expanded consumer choices without compromising Albertan rights.

Interestingly, the survey also indicated a growing awareness among Albertans about no-fault insurance, with a 10-point increase in familiarity since 2021. This heightened awareness is not solely the result of public discourse; it's also significantly driven by FAIR Alberta's proactive engagement through various media channels.

The advocacy group has amplified its message across TV, radio, and online advertising platforms, casting a wider net to educate and inform Albertans about the implications of auto insurance reforms. This multi-pronged approach to communication ensures that the debate around no-fault versus at-fault insurance is not only more visible but also accessible to a broader audience. The strategy underscores FAIR Alberta's commitment to fostering informed discussions on the subject, promising more engaged and thoughtful dialogue among the public and policymakers alike. This concerted effort to raise awareness plays a crucial role in shaping the future of auto insurance in Alberta, aligning with

the preferences of Albertans for a system that embodies fairness, accountability, and affordability.

The survey, which polled 900 Albertans between January 8 to 15, 2024, has a margin of error of +/- 3.3 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. Its findings not only reflect a strong provincial consensus but also illuminate the path forward for policymakers, underscoring the need for reforms that align with the public's preference for fairness, accountability, and affordability in the auto insurance sector.

Stop hindering the ability to take on new files, manage operating expenses, and invest in growth.

The answer: specialized law firm funding solutions.

Unlike traditional lenders, we fully understand the litigation practice business model. Deferred legal fees, unpredictable file durations and increasingly onerous disbursement requirements result in unique funding challenges that banks cannot address. We can.

Expert Access combines two essential services for lawyers: sourcing qualified experts using our proprietary Expert Search tool and deferring payment until settlement with no interest for two years.

A flexible tool law firms can use to finance any disbursement, on any file, at their discretion. Repayment is deferred until settlement of the underlying file, perfectly in line with a firm’s cash flow.

BridgePoint not only understand the contingency fee business model better than any bank, their disbursement funding solutions are tailor designed for it, with payments perfectly mirroring my settlement cashflow.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…

Charles Dickens’ well-quoted line is an apt descriptor for 2023 from a civil caselaw perspective. With respect to this year’s plaintiffs, judges seemed to feel “it was the epoch of belief, [or] it was the epoch of incredulity.” While the decisions themselves were varied, in their substance, their outcomes, and even their writing styles, one simple fact remains consistent: evidence and its impact on credibility makes or breaks a claim. While this point may seem obvious to seasoned counsel, recent cases highlight the importance of keeping evidence in the fronts of our minds as we attempt to assess risk and resolve claims.

The two cases of Camacho v Lacroix, 2023 ABKB 610 and Armbruster v Nutting, 2024 ABKB 36 provide a useful look at the impact of evidence on damages in personal injury damages in Alberta. The plaintiffs in each of these cases were both injured in rear-end motor vehicle collisions. Looking at these two cases together demonstrates how different plaintiffs with similar injuries and similar general damages awards can still walk away with two very different overall settlement amounts.

The Plaintiff in Camacho suffered from chronic neck and right shoulder pain, right arm weakness and tingling, headaches, sleep disruption, cognitive issues, and a TMJ injury. Justice Devlin found her to be a largely credible and sympathetic witness –highlighting her background of receiving medical training in Columbia, her military service, and her immigration to Canada. He considered Ms. Camacho to be a hard-working individual who had overcome significant adversity. While her pre-accident mental health issues resulted in Ms. Camacho not being entirely forthcoming with her treatment providers after the accident and there being some gaps in her treatment records, Justice Devlin stated that it impacted liability more than credibility.

The Plaintiff in Armbruster suffered similar injuries – a mild traumatic brain injury with associated headaches, TMJ injury, cervical myofascial pain, adjustment disorder, and PTSD. Justice Wilson immediately identified issues with Mr. Armbruster’s credibility, noting that his testimony and medical records often did not align. There were also several gaps in his treatment records. Because of Justice Wilson’s profound concerns with Mr.

Armbruster’s credibility and reliability as a witness, he also took issue with the expert reports that were based on Mr. Armbruster’s self-reported injuries and symptoms.

Despite how differently these two plaintiffs were perceived by their respective trial judges, both were awarded fairly similar amounts for general damages: $95,000 for Ms. Camacho and $70,000 for Mr. Armbruster. Based on this metric alone, it may appear that these plaintiffs’ presentations did not significantly impact their awards. However, awards under other heads of damages, reductions for failure to mitigate, and the final outcomes of each of these cases demonstrates how that is not always the case.

In Camacho, despite some gaps in her treatment record, it was sufficiently clear that Ms. Camacho was consistent in receiving treatment and was experiencing chronic injuries. She was going to require further treatment for these injuries. As such, she was awarded a significant future care award of $99,250.00.

However, her award for loss of earning capacity was a major issue. Both methods used by her counsel to calculate this loss were considered too speculative. The first loss of earning capacity calculation was based on her qualifying as a doctor in Canada. While she had medical training from her home country of Columbia, Justice Devlin found that the difficulty of the qualification process, particularly for someone with Ms. Camacho’s language issues and mental health challenges, meant that the evidence did not prove on a balance of probabilities that she would have achieved the qualification if not for the accident. Justice Devlin further rejected the level of disability used by the Plaintiff’s

economic expert, noting that the medical record did not support the severity of the claim. Despite these issues, he held that the evidence supported, on a balance of probabilities, a 15% reduction in her future earnings due to her injuries. Her loss of earning capacity award was calculated based on this amount.

The total damages award for Ms. Camacho broke down as follows:

• General damages: $95,000.00

• Past Loss of Income: $0

• Future loss of income: $261,000.00

• Cost of future care: $99,250.00

• Special damages: $16,048.85

• Total: $471,298.85

Conversely, in Armbruster, the Plaintiff’s credibility remained a significant issue, which pervaded the judge’s view under each head of damages and saturated the judgment. As such, there was no demonstrable past or future loss of income award. Of note, the Plaintiff had taken a leave from work and then retroactively tried to get doctors’ notes to retroactively make it into a medical leave. Justice Wilson did not accept this as a medical leave, as he did not see sufficient support in the evidentiary record.

Further, Mr. Armbruster’s evidence suggested a failure to mitigate his injuries. There were several medical records indicating recommendations for treatment that Mr. Armbruster did not follow. As such, his entire award was reduced.

The total damages awarded to Mr. Armbruster were:

• General damages: $70,000.00

• Special damages: $51,898.00

• Future costs of care: $30,000.00

• Loss of income/earning capacity: $0

• Subrogated claim: $7,765.00

• Subtotal: $159,663.00

• Failure to mitigate: 40% (-$63,865.00)

• Total: $95,798 (plus interest, costs, and disbursements).

It is not revolutionary to conclude that a plaintiff who presents well, with consistent testimony and medical documentation, will fare better than an inconsistent, unreliable plaintiff with spotty records. However, these two cases show just how significant that difference can be. The plaintiff in Camacho walked away with over $375,000 more than the plaintiff in Armbruster, despite the similarities in their accidents and injuries. The value of strong and cogent evidence, together with a sympathetic and prepared plaintiff, cannot be overstated.

The decision of Couch v Olatiregun, 2023 ABKB 104 represents one of the first times we’ve seen a court award damages below the amount in the Minor Injury Regulation (also known as the “cap” for minor injuries). This case serves as a warning for counsel dealing with potentially capped claims to ensure that we are presenting our client’s best possible case to avoid getting caught under it.

The plaintiff was in a rear-end motor vehicle collision. His injuries included pain and stiffness in his neck, upper back, shoulder, middle back, and ribs. He also experienced some headaches. His symptoms lasted approximately 10 weeks, with his headaches persisting intermittently for 8-9 months more. The Plaintiff had treated for approximately nine months with massage, chiroprac-

tic, and acupuncture treatments. He reported returning to his baseline – which included some pre-existing neck and back pain.

Despite hearing no contradictory evidence (because the self-represented defendant did not appear at tri al), Justice Sullivan held that the plaintiff’s injuries fell under the declined to award the full cap – even at the unadjusted value – instead awarding $3,000.00 (plus limited special damages). While his reasons outline why he decided the claim was capped, there is no discussion explaining his reasons for awarding below the full cap amount.

Of note, there are some gaps in this decision. For exam ple, Mr. Couch’s doctor diagnosed him with a WAD II injury (see para 15). However, Justice Sullivan’s finding was that the injury was categorized as WAD I. It is un clear from a reading of the decision what evidence was relied upon as the basis for this finding.

This case serves as a clear warning that judges can and will award below the cap and that they may do so with out opposing evidence or detailed reasons. It reminds us that we must always put our best evidentiary foot forward at all stages of a claim, no matter who may or may not be defending the claim, to avoid a highly unfa vourable decision.

These recent Alberta cases all serve to remind us of the evidentiary burdens that we have as counsel, particularly those of us representing plaintiffs. Proving the plaintiff’s case on a balance of probabilities requires the utmost diligence in preparing the evidentiary record in such a way that it supports our position on damages while also addressing any gaps or concerning aspects the case.

Of note, in many of these cases, speculation was the downfall of the plaintiff’s position. For example, in Camacho, the speculative nature of the loss of earning capacity argument meant that the plaintiff’s award was significantly less than she had claimed. In Armbruster, the Plaintiff’s own speculation about his condition where there was a lack of medical evidence served as a death blow to his credibility.

While it may seem simple, a strong evidentiary foun dation remains the cornerstone of civil decisions and should always be front of mind for us as counsel. We should continue to have “great expectations” about the power of evidence in meeting our burdens under the law.

For more information on case law updates in 2023, purchase the 2023 Case Law Review webinar and materials at www.actla.com

To

Ontario’s no-fault regime is a broken system. It’s paperwork heavy, invites serious delay, too often offers empty benefits, and horribly short-changes people who have been hurt in auto collisions. It’s an unjust regime for the injured, and a beautiful one for insurers.

Ontario’s no fault auto system was created in 1990. Legislators called their creation “Statutory Accident Benefits” (“Accident Benefits”). But make no mistake, it came at a great cost, especially to those hurt in auto collisions because of another driver’s negligence. In exchange for these no-fault auto benefits, motor vehicle insurers needed something big in return. And they got it. The “protected defendant”.

What’s a “protected defendant”? It’s anyone who is responsible for an injury or death arising from the use or operation of an automobile who was either present at the scene or inside an automobile involved in the incident. But that only tells you who the protected defendant is and not how they’re protected.

A protected defendant (read the insurance company covering the protected defendant) does not have to pay for any income losses suffered in the first week after an auto crash. NOTHING! After that, insurers only have to pay for 70% of the income losses up to the date of trial.

Then there is also something called a “deductible” and the “threshold”. As of today, there is a $46,000 deductible on pain and suffering damages.1 It’s not $4,600, but $46,000! That means if a Judge or jury assesses your pain and suffering at $50,000, then $46,000 of that goes back to the insurer and you, the person actually hurt by someone else’s carelessness, only get to keep a whopping $4,000. Sound fair? What’s worse? The deductible

1 It’s actually $46,053.20.

goes up every year with inflation. And while the deductible completely vanishes for pain and suffering assessed at more than $153,500,2 that upper bar also gets higher and higher every year with inflation.

But that’s only the deductible. Don’t forget about the “threshold”. Plaintiffs are not entitled to any pain and suffering or health care costs unless they have a permanent and serious injury that affects an important function. So even if a jury assesses your pain and suffering thinking YOU will be given those funds as fair value for what was taken from you, the insurance company can then bring a threshold motion to have those funds TAKEN AWAY from you. Why? Judges decide if a plaintiff meets the threshold, not juries.

What’s even worse is that the jury will not even know about the threshold motion or that the money was taken away. And they can’t be told about the deductible either. These special rules must be kept a BIG SECRET.

The number of people who are covered by Accident Benefits is quite broad. It applies to occupants (drivers and passengers) and non-occupants (cyclists and pedestrians) involved in an Ontario “accident”3 with an insured automobile. In many cases, they can be provided to people who were involved in a crash outside of Ontario too.4 In certain scenarios, Accident Benefits are even available to people who were not involved in an accident themselves but who are nevertheless suffering psychologically

2 It’s actually $153,509.39.

3 “Accident” is a defined term. It is any incident in which the use or operation of an automobile directly causes an impairment or directly causes damage to any prescription eyewear, denture, hearing aid, prosthesis or other medical or dental device.

4 You must be a named insured in an Ontario auto policy, a specified driver under such a policy, the spouse of a named insured, or a dependent of a named insured or of his or her spouse. Or you must be an occupant of an insured automobile involved in the accident who resided in Ontario at any point within the last 60 days before the crash.

because a family member or dependent was hurt in one.5

There is a standard set of auto benefits that are provided. A list of them is as follows.

1. Death Benefits

2. Funeral Benefits

3. Income Replacement Benefits (IRBs)

4. Non-Earner Benefits (NEBs)

5. Med / Rehab

6. Attendant Care

However, if you have suffered a catastrophic impairment because of an auto crash then you also have access to certain additional benefits and certain extended benefit limits too. A list of what else you can access is as follows.

1. Housekeeping and home maintenance

2. Caregiver Benefits

3. Extended Med / Rehab and Attendant Care Benefits

When you are catastrophically impaired, your monthly attendant care limits go up from $3,000 to $6,000 per month, and your med / rehab and attendant care overall limits increase from $65,000 total over 5 years to $1,000,000 total over your lifetime.

This is the standard package. There are also add-ons you can get called “optional benefits”.

5 You must be a named insured, specified driver, spouse of a named insured, or dependent of a named insured or of his or her spouse who suffers a psychological or mental injury because of an accident inside or outside Ontario that resulted in a physical injury to their spouse, dependent, spouse’s dependent, child, grandchild, parent, grandparent, or sibling.

Sadly, benefits have been slashed over the last 10 years. The system was gutted before then too. But that’s the topic of another article. There are LOTS OF BIG PROBLEMS with what’s left. I will hit the highlights.

The big problem with IRBs is how they’re calculated.

First, your IRB only pays up to 70% of your income loss. And if you have a lawsuit, the IRB will be deducted from your income loss claim. This means that hefty 30% discount auto insurers get in your lawsuit can’t be recouped through no-fault benefits. Remember, if you start an action, insurers only have to pay 70% of your income losses to trial. I called it a discount but it’s really a gouge.

On top of that, the IRB is capped at $400/week! That’s only $20,800 annually! $20,800 per year is BELOW THE POVERTY LINE. And while the secret deductible increases every year with inflation, the IRB has NEVER been adjusted for inflation!!! It’s the same amount it was 34 years ago.

Approximately 70% of every dollar you earn after your crash is deducted from your IRB – not your loss. I can highlight the unfairness with an example. Let’s say you make $130,000 per year. However, after your horrible car collision you are only able to work at less than 25% of your capacity. Let’s say you’re only making $30,000 per year, which is an annual loss of $100,000. Now you might think that you’ll be entitled to 70% of that $100,000 loss up to $400/week. But you would be wrong! 70% of what you’re taking home is more than $400 per week and so your IRB amounts to ZERO!

But if you can’t work, you may qualify for social assistance or

Canada Pension Plan Disability. You may get LTD. You can stack the payments to recoup your losses, right? No! Everything gets deducted or offset one way or the other. You can’t stack! – not even to recoup your losses to make you whole again.

You may think that med / rehab in our no-fault world operates like health benefits through work. You have a certain limit, you go to treatment, submit your costs, and then get compensated. Perhaps, occasionally, your insurer may ask for a medical note to justify your claim. But that’s not how no-fault works.

Instead, your treatment providers must submit a treatment plan to your insurance adjuster for approval. Once that’s done, then another must be submitted. Then another, and another. The adjuster, who is not a physician or health care professional,

And like med / rehab, you must submit your plan to the insurance adjuster for approval. The adjuster will then determine if it is needed.

If you have not suffered a “minor injury” or a catastrophic impairment, then your med/rehab and attendant care benefits have a combined limit of $65,000 that’s available for 5 years.

While that may not sound too bad, you must remember that fewer than 20% of claimants fall into this category. The overwhelming majority are thrown into the Minor Injury Guideline (for an apparently “minor injury”).

"...adjusterswillonlypaysignificantlyreducedratesin accordancewithaguidelinecreatedbackin2014.That meansifyouneedtreatment,youmaynotbeabletofind anyonetotakeyouonasapatient..."

then decides whether the treatment your very OWN health professionals are recommending is needed. If they are unsure, they won’t ask for a report from the treating health professionals, but they will hire one of their preferred health professionals to do an insurer examination (“IE”). These IEs most often limit or rejects the proposed treatment plans by the treating health care provider.

Furthermore, adjusters will only pay SIGNIFICANTLY REDUCED rates in accordance with a guideline created back in 2014. That means if you need treatment, you may not be able to find anyone to take you on as a patient because the RATES ARE SO LOW! This begs the question: what’s the point of a benefit if you can’t access it when you need it most?

Attendant care is too often a phantom benefit. Why? Fees are paid in accordance with a 2018 guideline that ignores market realities (just like the 2014 fee guideline for med / rehab). Some of the fee rates are so low THEY DON’T EVEN MEET MINIMUM WAGE.

So, even if your insurer approves you for attendant care, you may not be able to find any professional to help you! Many PSWs can’t afford to do the work – as the insurer-approved rates are often below minimum wage!

If you’re lucky, family members or friends will help you. You may think that those people can be paid instead. But to get paid, they must prove that they have suffered an “economic loss”. So, someone who can’t afford to take time off work and does what they can after hours to help you at home won’t get paid a dime.

If you have suffered a “minor injury” you are placed into the Minor Injury Guideline (MIG). This category represents over 80% of all accident benefits claims. As long as you’re in the MIG, you’re not entitled to any attendant care and your med / rehab limits are only $3,500.

One of the major problems with this system is this: a “minor injury” includes conditions that are NOT MINOR – like partially torn ligaments, tendons, or muscles, or partially dislocated joints, and their “clinically associated sequalae”.

Further, if you have other injuries but your injury is still “predominantly” a “minor injury”, you still have a “minor injury”. And if you are suffering many, many, many “minor” injuries at one time from your auto crash, they are all collectively considered one “minor injury”. So, if you have multiple torn ligaments, tendons and muscles and multiple partially dislocated joints in many different parts of your body, you must be placed into the MIG.

Now, there are some conditions that may result in an injured insured being removed from the MIG (i.e. pre-existing condition), but removal from the MIG is onerous and insurance adjusters have ultimate discretion to deny a claim and force an insured to adjudicate a dispute before the governing administrative tribunal. This system is slow, complicated and unfair.

The determination of catastrophic impairment is too complicated and encourages insurer denials and delay and endless insurer

examinations.

Many of the definitions for catastrophic impairment are very technical and very challenging to meet. This means that far too many people who desperately need more than $65,000 worth of med / rehab and attendant care fall through the cracks. The CAT category represents approximately 1% of accident benefits claimants. The test has been amended for over a decade to become more restrictive.

What about the limits? $1,000,000 sounds like a lot of money, but it’s not when you’re catastrophically impaired. Picture someone who needs extensive therapy multiple times per week; significant renovations to their home to make it accessible; weekly help with dressing, washing, eating, and preparing meals; and regular monitoring for their safety FOR THE REST OF THEIR LIFE. The costs add up fast. The money runs out fast.

In theory, you can always opt for a better plan. But you need to know your options. You need to know what they are, why you may want them and what they cost. They’re typically cheap – by the way. The problem is that too often brokers and insurers are not properly informing people of these options or making recommendations about them. I can only think of ONE CLIENT…JUST ONE…who had them. And I’ve been a lawyer for almost 14 years. The vast majority have never even heard of them. Optional Benefits? What are those?

The Dispute Resolution System: The Licence Appeal Tribunal (LAT)

If you are denied any of your benefits by your insurer, you have two years to dispute the denial. You dispute the denial by filing an application with the Licence Appeal Tribunal (the LAT). My concerns with the LAT could be a large article unto itself. I will highlight only thing: time. It generally takes well over a year to get to your hearing. Sometimes it takes much longer.

In the meantime, people who are catastrophically impaired and in desperate need of treatment and help at home must wait…and wait…and wait.

If you’re not catastrophically impaired, one denial of needed med / rehab can certainly set you back BIG TIME in your progress, but it can also cost you one or more of your valuable 5 years of treatment – even if the denial was obviously wrong.

There are also no legal costs awarded to an insured that successfully disputes an insurer denial before the LAT. Nothing for legal fees and nothing for disbursements. The system often has self-represented insureds battling insurers and their legal counsel.

I could write so much more about the tragedies of Ontario’s no-fault regime. But here’s the point. If you happen to be dreaming of a world where no-fault auto benefits are brought to your province to work harmoniously with a fair tort system, remember…remember…dreams can quickly become nightmares. They’re part of the same realm.

James Page was called to the Bar in 2010 and practices exclusively in the areas of personal injury and civil litigation.

Along with his colleague, Laura Hillyer, James was among the first lawyers in Ontario to successfully move to strike a civil jury as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Shortly thereafter, James and Laura were among the first lawyers in the Province to conduct a completely virtual personal injury trial via Zoom.

James is the Vice President of the Halton County Law Association (HCLA), a Past President of the Brain Injury Association of Peel & Halton (BIAPH) and a board of director for the Ontario Trial Lawyers’ Association (OTLA). James is also former participant in the Ontario Justice Network (OJEN) as a mock trial coach for local high school students.

In addition to chairing and co-chairing seminars for Halton County Law Association, James has spoken at seminars for a number of different lawyers’ associations, including OTLA, BIAPH, the Canadian Defence Lawyers (CDL) and the Hamilton Law Association (HLA). He is a quarterly contributor to the HCLA Newsletter (Civil Litigation Law News) and a regular contributor to weekly case summaries for the Ontario Trial Lawyers Association (OTLA), which highlights the most recent important decisions in personal injury law.

We have seen several cases in the Courts across Canada dealing with medical malpractice claims analyzing the issue of standard of care and causation relating to aneurysms and resulting stroke.

Today we will share a few facts about this type of brain bleed. Typically symptoms may include a history of headaches, fever, nausea, vomiting, blurry vision, and neck stiffness to name a few. At times, these symptoms may be confused with migraine headaches. An angiogram is a test that would be conducted to identify a ruptured aneurysm. For a diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage, a lumbar puncture may also be undertaken to assist in such a diagnosis. Recommendations for a clear diagnosis on aneurysms, including assessments of headaches that may be linked to a ruptured aneurysm, would be a neurologist and/or a neuro-surgeon.

“The most frequent cause of SAH is head trauma in seventy percent (70%) of cases. A traumatic SAH is a self-limiting condition for which there is generally no treatment other than medication prescribed. However, in almost thirty percent (30%) of cases, blood found in the subarachnoid space is caused by spontaneous and life-threatening conditions, the most frequent of which is due to leaking or ruptured aneurysm. A small percentage of cases of spontaneous SAH may also be due to arteriovenous malformation, another life-threatening condition.” This quote is referenced in Williams v. Bowler, 2005 CanLII 27526 (ON SC).

In another decision of the Court, we review a case regarding an unfortunate situation in 2006 dealing with ruptured aneurysm and symptoms that follow. This case is referenced as Borglund v. Fraser Valley Health Region et al, 2006 BCSC 1338 (CanLII).

The Plaintiff was involved in a road rage altercation wherein

another driver punched the Plaintiff in the head. A few days later an existing aneurysm ruptured, resulting in a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

The initial diagnosis in this case was concussion as opposed to aneurysm. As a result of the concussion diagnosis, a CT scan was not ordered on the 1st or 2nd visit to the hospital, resulting in a delay in diagnosis of aneurysm and necessary treatment.

Here is the timeline:

Dec 17, 1999 – road rage incident

Dec 19, 1999 – attended emergency

Dec 20, 1999 – attended emergency again

Dec 21, 1999 – attended emergency again, referred to neurologist, CT scan ordered

Dec 22, 1999 – diagnosis was made

An important fact outlined in this case was that the rupture of the existing aneurysm was not caused by the road rage incident. “The parties agree that the ruptured aneurysm was not caused by the earlier punch to the head, suffered in the road rage incident.”

This claim names the Fraser Valley Health Region and various doctors as Defendants. The legal theory in this case as presented by the Plaintiff is that the named Defendants allegedly failed to meet the standard of care in failing to diagnose the subarachnoid hemorrhage and initiate treatment. An urgent CT scan was not ordered on the 1st or 2nd visit to hospital, nor was the Plaintiff referral to a neurologist until the 3rd visit to hospital. It is the

Plaintiff’s position that this delay resulted and caused the severe and prolonged vasospasm. In other words, had the diagnosis of aneurysm been made earlier, it is argued that earlier treatment may have prevented the resulting vasospasm.

The Court did not agree with the Plaintiff. The claim was not successful. The action was dismissed with costs to the Defendants. There is a lot to learn, however, from reviewing this case.

A subarachnoid haemorrhage means that there is bleeding in the space that surrounds the brain. Most often, it occurs when a weak area in a blood vessel (aneurysm) on the surface of the brain bursts and leaks. The blood then builds up around the brain and inside the skull increasing pressure on the brain.

Humans rely on blood vessels called arteries to carry oxygen-rich blood to all parts of our bodies. Vasospasm occurs when an artery suddenly narrows and the blood supply is drastically reduced. It most often happens in the brain or in the heart. The results can be serious. Sometimes the term vasospasm is used to describe the narrowing of small blood vessels in the hands.

“Vaso” means vessel. A spasm is a sudden muscular contraction. A vasospasm is a sudden contraction of the muscular walls of a blood vessel. In some cases, we know what causes the muscles to contract. Other times it’s a mystery.

Cerebral relates to the brain. A cerebral vasospasm almost always follows another major event inside the skull, called a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH). This is a kind of stroke that happens when a blood vessel on the surface of the brain breaks. Blood fills the space between the skull and the brain. It leaks beneath the arachnoid membrane.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage or SAH is most often caused by an

aneurysm. An aneurysm is a weak place in a blood vessel often resulting in a balloon-like bulge. SAH is the most dangerous type of stroke. You might survive the stroke but then have a cerebral vasospasm, which puts your health and life at risk for a second time.

Cedars Sinai provides the following list of symptoms as it relates to vasospasm:

Symptoms of a vasospasm can vary depending on the area of the body affected. When the condition occurs in the brain, symptoms may include:

• Fever

• Neck stiffness

• Confusion

• Difficulty with speaking

• Weakness on one side of the body

• Patients who have experienced a cerebral vasospasm often also have stroke-like symptoms:

• Numbness or weakness of the face, arm or leg, especially on one side of the body

• Confusion

• Trouble speaking

• Trouble seeing in one or both eyes

• Trouble walking

• Dizziness, loss of balance or coordination

• Severe headache with no known cause

The Plaintiff in this case had the following symptoms as reported by the emergency room physician

• Intense headache described as “severe”

• Numbness and tingling on right side of head

• Nausea with vomiting

While the Plaintiff attended hospital a few times reporting severe headaches with nausea and vomiting, he was diagnosed with concussion and released from hospital. A third attendance to hospital resulted in further symptoms of dehydration and looking quite unwell, and the emergency room physician referred the Plaintiff

to a neurologist for consultation.

Neurologist recorded the following further symptoms

• Head trauma

• No loss of consciousness after being struck to the head

• Discomfort in temporal frontal area

• Numbness in right arm and leg

• Constant headache since the incident of assault

• Nausea

• Not eating well

• Dehydrated with dry mouth and mucous membranes

As a result, the Plaintiff was hospitalized for observation and a CT scan was finally ordered. Intravenous fluids were also commenced. CT Scan showed subarachnoid blood and surgery was required by a neuro-surgeon as 3 aneurysms were found and 2 of the 3 aneurysms were clipped in surgery. Medication was also prescribed to reduce the risk of secondary ischemic injury or stroke following an aneurysm. His symptoms continued post surgery with right-sided drift, increased focal deficit to his right leg and further imaging showed vasospasm of the anterior cerebral complex. Although treated, his condition deteriorated.

The Plaintiff developed pulmonary edema, pneumonia and a seizure – he suffered “severe and prolonged vasospasm which left him with infarcts in the area of his left anterior cerebral artery. He was left with problems of receptive and expressive speech as well as other cognitive deficits.” He attended GF Strong for rehabilitation but continued to suffer from symptoms of decreased cognition, reasoning, right-sided weakness, and speech deficits. He required supervision in self-care. The Plaintiff also had problems with safety awareness, judgment and problems with balance and coordination.

The Issues

1. Did the physicians owe this Plaintiff a duty of care?

2. Was there a breach of the duty of care?

3. Did such breach cause or contribute to the injury that resulted?

While it is fairly straight forward to establish that a duty of care may be owed to a Plaintiff (patient), that is not always the case as it relates to proving that a breach of the said duty occurred or more importantly, the test of causation.

The legal theory of the Plaintiff in this case is that the delay in diagnosis and in treatment resulted in the outcome, and had treatment been initiated earlier, and prior to Dec. 22, 1999, the outcome would not have been as serious, leaving him with the resulting injury.

The legal theory of the Defendants is that a delay in treatment did not worsen the Plaintiff’s condition, and therefore, causation is not established, and this claim must be dismissed.

The conclusion in this case is noted:

In the result, I find that the defendants owed the plaintiff a duty of care to provide medical treatment consistent with that of reasonable emergency room physicians in the circumstances and that the defendants failed to meet that standard

of care. I find, however, that the defendants’ failure to diagnose the plaintiff’s condition did not ultimately worsen the plaintiff’s outcome. The action is dismissed, with costs to the defendants.

I will identify some of the evidence directly from this decision that was put before the Courts, sharing the interesting points as it relates to aneurysms.

Standard of care (Plaintiff)

• The onus is on the emergency room physician to exclude the presence of significant underlying pathology.

• The most important cause of this pattern of headache is subarachnoid haemorrhage.

• A CT scan and, if necessary, a lumbar puncture are indicated.

• Subarachnoid haemorrhage is a neurological and neurosurgical emergency which must be considered by all physicians evaluating acute headaches, particularly in the emergency department setting.

• The persisting complaints of a severe headache in a patient who has no prior history of similar headaches and the fact that the headaches were accompanied by persisting nausea and vomiting to the point of dehydration should have alerted the assessing physicians to the possibility of a potentially catastrophic intracerebral condition.

• There is a positive family history for cerebral aneurysms.

• The failure to take steps easily available to rule out a serious underlying condition (with potentially catastrophic consequences) amounts to conduct below the standard of regular practice.

Standard of Care (Defence)

• The record also indicates a normal neurological examination.

• The record also indicates that the patient responded very well to relatively conservative treatment

• Very good follow-up instructions was given.

• The diagnosis of concussion is entirely reasonable given this presentation.

• CT would be strictly a judgment call.

• There is also a continued pressure on physicians to manage resources.

• Every patient that presents cannot obviously be investigated.

Following is a very interesting comment that most members of the public do not consider when they attend at emergency or even at their doctor’s office. A statement from the Court:

In my view, each of Drs. X and Y were distracted by the assault which Mr. x had experienced earlier in the day of December 17, 1999. They associated the headache with the assault, likely because Mr. x associated his headache with the assault.

The question then is – should a patient be explaining what hap-

pened ? The incident itself – if it is a potential to cause a “distraction” – or are physicians trained enough to not be “distracted” by associating the cause of the “symptoms” to the incident. Would a doctor opine differently if they did not have a reason for the headaches ?

The Court further agreed with the following medical opinion provided by experts retained by the Plaintiff:

“it is the emergency physician’s duty to obtain sufficient information in the history to distinguish potentially life threatening headaches from more benign headaches, that is, to distinguish those that require urgent treatment from those which may be treated conservatively.”

As it relates to breaching the standard of care, the Court stated the following:

“In failing to ask questions necessary to rule out a serious underlying cause when the plaintiff was capable of providing informative responses, Drs. X and Y failed to meet the standard of care of a reasonable emergency room physician in the circumstances.”

On the topic of causation, here are a few facts derived from the case from both sides:

• The standard treatment for subarachnoid hemorrhage is to institute the drug Nimodipine immediately, to operate to repair the aneurysm, to rehydrate the patient to euvolemic levels and, if vasospasm develops, to raise the plaintiff’s blood pressure and blood volume.

• Cerebral vasospasm occurs as a direct result of the subarachnoid hemorrhage.

• It is a serious and often devastating condition, caused by the breakdown of blood components in the subarachnoid space and their effect on the cerebral blood vessels.

• The incidence and severity of spasm is related to the amount of blood at the time of the bleed.

• The amount of blood revealed on a CT scan of a patient’s brain can predict the likelihood that vasospasm will develop.

• When severe, it causes cerebral infarction, neurological deficit and death.

While both parties had different positions on whether delayed treatment caused the serious vasospasm, the Court found, as a finding of fact, that causation had not been established, and the case was dismissed with costs to the Defendants.

Receive expedited access to the best expert assessors in the country, when and where you need it. Viewpoint court-qualified experts are credible, highly experienced and well respected in their fields.

Tort law has historically been cautious in granting relief for injuries to mental well-being. While in modern times the scope for compensation related to psychological injury has expanded beyond the limited sphere that was permitted in the early nervous shock cases, the common law’s concern for open-ended liability continues to be reflected in the case law. In particular, where psychological injury is alleged, remoteness and foreseeability are typically key issues.

Claims by indirect plaintiffs – for example, family members who were not present at the scene of an accident but nonetheless suffer emotional distress or shock as a result of a loved one’s injury – continue to be interesting and challenging cases where the analysis of remoteness and foreseeability is key. Case law indicates that the analysis is factually driven, and there is no “bright line” determining which types of facts will or will not support a successful claim.

Negligence claims for psychological injury have been considered by the Supreme Court of Canada in two prominent cases, Mustapha v. Culligan of Canada Ltd., 2008 SCC 27, [2008] SCJ No 27 and Saadati v. Moorhead, 2017 SCC 28, [2017] SCJ No 28.

In Mustapha, McLachlin CJ confirmed that like any negligence claim, a claim for psychological injury requires that the plaintiff demonstrate 1) that the defendant owed him a duty of care; 2) that the defendant’s conduct breached the standard of care; 3) that the plaintiff sustained damage; and 4) that the damage was caused, in fact and in law, by the defendant’s breach. While McLachlin CJ declined to define compensable injury exhaustively, she noted that it must be serious and prolonged and “rise above the ordinary annoyances, anxieties and fears that people living in society routinely, if sometimes reluctantly, accept” (at para 9).

In psychological injury claims, it is not uncommon for debate to focus in particular around the fourth element of the test – namely, causation in fact and law – where issues of remoteness and foreseeability are addressed. The remoteness issue asks whether the harm is too unrelated to the wrongful conduct to hold the defendant fairly liable. It depends on the degree of probability required to meet the reasonable foreseeability requirement and also on whether the plaintiff’s harm is considered objectively or subjectively.

The law has consistently held that the question is what a person of ordinary fortitude would suffer. In Mustapha, McLachlin CJ explained how distinctions may be drawn between psychological injuries that are foreseeable, and those that are not:

[15] […] the requirement that a mental injury would occur in a person of ordinary fortitude, set out in Vanek, at paras. 59-61, is inherent in the notion of foreseeability. […] As stated in Tame v. New South Wales (2002), 211 C.L.R. 317, [2002] HCA 35, per Gleeson C.J., this “is a way of expressing the idea that there are some people with such a degree of susceptibility to psychiatric injury that it is ordinarily unreasonable to require strangers to have in contemplation the possibility of harm to them, or to expect strangers to take care to avoid such harm” (para. 16). To put it another way, unusual or extreme reactions to events caused by negligence are imaginable but not reasonably foreseeable.

[16] To say this is not to marginalize or penalize those particularly vulnerable to mental injury. It is merely to confirm that the law of tort imposes an obligation to compensate for any harm done on the basis of reasonable foresight, not as insurance. […] Once a plaintiff establishes the foreseeability that a mental injury would occur in a person of ordinary fortitude, by contrast, the defendant must take the plaintiff as it finds him for purposes of damages. As stated in White, at p. 1512, focusing on the person of ordinary fortitude for the purposes of determining foreseeability “is not to be confused with the ‘eggshell skull’ situation, where as a result of a breach of duty the damage inflicted proves to be more serious than expected”. Rather, it is a threshold test for establishing compensability of damage at law. [emphasis added]

The degree of probability that would satisfy the reasonable foreseeability requirement is a “real risk”, one which would occur to the mind of a reasonable person in the position of the defendant and which they would not brush aside as far-fetched (para 13).

In Mustapha, the plaintiff claimed damages for psychological injuries sustained as a result of seeing dead flies in a bottle of water supplied by the defendant. Although successful at trial, the Supreme Court of Canada found a cause of action in negligence had not been established. It was accepted that the defendant’s breach of its duty of care in fact caused the plaintiff’s psychiatric injury. However, at issue was whether the breach also caused the plaintiff’s damage in law or whether it was too removed to warrant recovery. The plaintiff had failed to establish his damage was caused in law by the defendant’s negligence. The plaintiff had failed to show it was foreseeable that a person of ordinary fortitude would suffer serious injury from seeing the flies in the water bottle. His damages were too remote to allow recovery.

Mustapha thus recognized that a duty exists at common law to take reasonable care to avoid causing foreseeable mental injury. The ordinary duty of care analysis is to be applied. It is unnecessary to mandate formal, separate consideration of certain dimensions of proximity. Temporal, geographic and relational considerations might inform the proximity analysis but the proximity analysis is to be sufficiently flexible to capture all relevant circumstances that might in any given case be relevant to determining a close and direct relationship, which is the hallmark of the common law duty of care.

In Saadati, the Supreme Court of Canada confirmed the elements of the cause of action in negligence as well as the threshold for proving mental injury as outlined in Mustapha. Brown J. further confirmed that Mustapha stands for the proposition that recoverability of mental injury depends on the claimant satisfying the criteria applicable to any successful action in negligence and that each of the four criteria can pose a significant hurdle as, for example, not all claimants alleging mental injury will be in a relationship of sufficient proximity with the defendants to ground a duty of care, and not all mental injury is caused, in fact or in law, by the defendant’s negligent conduct:

[20] Mustapha thus serves as a salutary reminder that, even where a duty of care, a breach, damage and factual causation are established, there remains the pertinent threshold question of legal causation, or remoteness -- that is, whether the occurrence of mental harm in a person of ordinary fortitude was the rea-

sonably foreseeable result of the defendant's negligent conduct (Mustapha, at paras. 14-16). And, just as recovery for physical injury will not be possible where injury of that kind was not the foreseeable result of the defendant's negligence, so too will claimants be denied recovery (as the claimant in Mustapha was denied recovery) where mental injury could not have been foreseen to result from the defendant's negligence.

However, Saadati also rejected authorities suggesting that requirements of "relational", "locational", and "temporal" proximity should be formally applied as part of the test for establishing a viable claim:

[16] Further obstacles to recovery for mental injury arose in English law. In McLoughlin v. O'Brian, at pp. 419-21, Lord Wilberforce posited three considerations that could limit the boundaries of compensable "nervous shock": the class of persons whose claims should be recognized (often referred to as relational proximity), the proximity of such persons to the accident (locational, or geographical proximity), and the means by which the "shock" is caused (temporal proximity). [...] […]

[24] […] it is in my view unnecessary and indeed futile to re-structure that analysis so as to mandate formal, separate consideration of certain dimensions of proximity, as was done in McLoughlin v. O'Brian. Certainly, "temporal", "geographic" and "relational" considerations might well inform the proximity analysis to be performed in some cases. But the proximity analysis as formulated by this Court is, and is intended to be, sufficiently flexible to capture all relevant circumstances that might in any given case go to seeking out the "close and direct" relationship which is the hallmark of the common law duty of care […].

Saadati further confirmed that a recognizable psychiatric illness is not a precondition to recovery for mental injury or nervous shock (at para 2).

The principles regarding reasonable foreseeability in negligence cases outlined in Mustapha and Saadati were recently recognized by the Alberta Court of King’s Bench in the medical negligence case of KY v. Bahler, 2023 ABKB 280, [2023] AJ No 486. Renke J. noted that foreseeability is assessed in the circumstances of the defendant. The injury or loss must not simply have been possible but rather, the injury must have been a “real risk”, as described in Mustapha. The issue is whether the class, type, or kind of injury was foreseeable, not the extent of the actual injury or the precise manner of its occurrence (at paras 862-864).

Cases post-Saadati have wrestled with whether or not a claim for psychological injury is sustainable when the claimant was not present at the accident scene. The cases suggest that although refuting remoteness and foreseeability concerns may be challenging, each case turns on its own facts, and successful claims are not precluded.

In Cox v. Fleming, [1995] BCJ No 2499, 15 BCLR (3d) 2011 (CA), the plaintiffs were the parents of an 18-year-

old who was critically injured in a motor vehicle accident and who later died in hospital. Although accepting expert evidence that the father did not suffer from PTSD, the court nonetheless allowed the father ’s claim for psychological injury, finding that the sight of his son so badly injured in the hospital did have a lasting impact on him, and qualified this type of impact as an "emotional scar" that is compensable (at paras 13-15).

In Labrosse v. Jones, 2021 ONSC 8031, [2021] OJ No 6829, the plaintiff claimed for psychological injuries suffered after she was called by her daughter from the scene of an accident in which the daughter was seriously injured. The plaintiff was traumatized by what she heard on the telephone, by her inability to provide assistance to her daughter and by the traumatic nature of her daughter’s injuries. MacLeod RSJ found that foreseeability, whether at the duty of care stage or the remoteness stage, was the key issue. He further found it appeared “far fetched” to include a person phoned by an accident victim in the same class as a person who is present at an accident, noting there is a significant body of case law that has refused to award damages for mental injury to family members who were simply informed of an accident. However, given the “omnipresence of digital communication” and the rejection of arbitrary proximity factors in Saadati, it was difficult to justify a distinction between a plaintiff who was present at an accident and saw or heard it and a plaintiff that was able to hear the accident while connected by a phone. The foreseeability analysis required nuanced findings of fact that were genuine issues best resolved at trial, sufficient to defeat the defendants’ motion for summary judgment.