Contents

Foreword (Margarita Jover) / 8

Acknowledgements / 12

Introduction Bigness, Katrina, Conflict, Hybridity & Audience / 18

Backstory “from Times Beach…” / 32

Definintions Watershed, Architecture & Way Beyond Bigness / 44

Appreciate + Analyze [A+A] / 53

Description (Anthony Acciavatti) / 55

Why the Mississippi, Mekong, & Rhine? / 62

Who Manages the River Basins? / 66

Mississippi, Mekong, and Rhine River Basin Atlas / 84 (with Jess Vanecek, Paul Wu, Chenyu Zhang)

Mississippi River Basin & the World / 86

Missouri River Basin / 96

Erasure (Kees Lokman) / 121

Scar (Meghan Kirkwood) / 132

Upper Mississippi, Ohio, & Tennessee River Basins / 144

Reconnection (Chuck Theiling) / 169

Depth (Jesse Vogler) / 183

Between (Jennifer Colten) / 196

6

AR+D Publishing

Above (with Jess Vanecek) / 199

Lower Mississippi & Arkansas-White-Red River Basins / 202 Splitting (Forbes Lipschitz & Justine Holzman) / 227 Shifting (Alex Kolker) / 239

Mekong River Basin & the World / 250 Development (Dorothy Tang) / 260 Balance (Palakorn Chanbanyong & Simon Krohn) / 344 Adapt (Shelby Elizabeth Doyle) / 355 Monitor (Duong Van Ni) / 366

Rhine River Basin & the World / 378 Transform (Han Meyer) / 388 Revive (Robbert de Koning & Dale Morris) / 451

Speculate + Synthesize [S+S] /469

Context (Ian Caine) / 471

from the Big Six to the Birds Foot / 487 (with Jonathan Stitelman, Allison Méndez, L. Irene Compadre & Chad Fisk)

from the Third Pole to the Nine Dragons / 500 (with Jess Vanecek & Rob Birch)

from the Rheinquelle to the Leo Hollandicus / 518 (with Jess Vanecek, Paul Wu, & Han Meyer)

Collaborate + Catalyze [C+C] / 525

Advocacy (Neeraj Bhatia) / 527

Public Lab River Rat Pack / 539 (with Washington University in St. Louis)

Flood—Fight—Fail / 552

Territories—Watersheds—Infrastructures / 557 (with Washington University in St. Louis)

Tracing Our Mississippi / 584 (with Washington University in St. Louis)

Afterword “...to Quarantine Island” (“Big Muddy” Mike Clark) / 589

7

AR+D Publishing

Foreword

Margarita Jover

Way Beyond Bigness: The Need for a Watershed Architecture is a book on an essential contemporary topic: large-scale urban thinking. It is part of a lineage of the awakening of architecture’s discipline to the subject of large scale after five decades of progressive shrinking to smaller scales and the economically efficient production of buildings. In this sense, it is a book to celebrate. It offers a methodology for designers to urgently address the collective destiny of the built environment and its intertwined political, ecological, and social crises. In the United States, neoliberalism is hegemonic, which means it is an economic system and a cultural framework that implies suspicion of collectivism 1 and the public sphere while glorifying the market, the private sphere, and the individual. Added to this neoliberal hegemony is the citizen’s distrust of largescale national investments in the territory due to its historical tendency to favor the private interests of big companies and powerful individuals over the rest. This national investment’s legacy makes it difficult to promote large-scale projects from the top, even if they genuinely seek the common good, without generating a societal distrust.

Before the advent of neoliberalism and the acceptance of the market as the main leading force for the design and construction of the city, large-scale territorial and urban design decisions were inscribed into a public-private legal practice called urbanism. The word urbanism,2 coined during the mid-19th century in Europe, was the result of the search for new urban models and the construction of a new discipline to accommodate the transition from organic to industrial societies 3 Reimagined urban models allowed the overcoming of the social and ecological crises of the crowded and polluted cities of emergent industrial societies, while facilitating their spiritual, physical, and economic flourishing. Successful deployment of urbanism occurred when collaboration between private actors looking after maximizing profit was in friction

8

AR+D Publishing

with strong public actors looking at increasing social welfare across all social classes while supporting ecological needs. However, this successful deployment of urbanism did not always take place.

Nineteenth-century urbanism emerged as a set of rules and methodologies similar to this book’s spirit. Several architects, planners, landscape architects, and philanthropists advocating for reforms and new city models used different types of urbanism to respond to unregulated industrial cities and associated degradation. Thinkers such as Charles Fourier, William Morris, Otto Wagner, Patrick Geddes, Baron Haussman, Ildefons Cerda, Frederik Law Olmsted, Hendrik Petrus Berlage, Edwin Lutyens, and Tony Garnier, among many others, wrote about cities and designed parts of them. There were significant differences in each methodological approach and output, ranging from isolated utopian communities to the bulldozing of old cities or new cities’ design. However, despite differences, the standard tread was the ambition to transform the medieval city model to accommodate population growth and industrialization.

This 19th-century lineage of urban thinkers on a large territorial and urban scale had its last cultural manifestations during the Modern Movement, when architectural culture organized the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM 1928–1959). Confident optimism in technology and sciences, mass production, and new aesthetic values characterized this period. Working-class upheavals and their increased societal influence and power allowed progressive universal suffrage, universal primary education, decent wages, and regulation of working hours. Social ambitions of equality in accessing resources for life and a more isotropic distribution of wealth in the urban context are often part of modernity’s projects in Europe. Architectural projects, manifestoes, and regulations that came about in that period produced significant innovations and societal improvements. However, after this period of heroic modernity, the social and economic instability of the 1930s led to World War II, with more than 60 million deaths worldwide. Post–World War II reconstruction in Europe took time and used prewar modern principles that included societal ambitions of redistribution and new technologies and materials in the context of socialist democracies. Postwar United States took on modernity principles that were adapted and often cleansed of social ambitions. The suburban model of separated functions in the territory4 took the lead, leaving behind the mixed-use city model with better social and ecological performances. The suburban model is predatory, with high levels of energy, land, and resource consumption, but it is successful for being a more efficient model of driving capital accumulation.

The giant American war industry—which saved Europe from tyranny and fascism— mutated and integrated into industrial societal dynamics creating new markets for its survival and subsequent growth. Today the industry of war is one of the major causes of climate change, but it runs unquestioned.5 Consumerism, suburbanization, and a culture of abundant energy coincided with postmodernity 6 in architecture and planning, which meant skepticism towards grand narratives and a focus on building forms and their cultural meaning. During the 1980s, the discipline became an avoidable friction to capital accumulation and retreated into the building scale. In the meantime, market

AR+D Publishing

9

Designers, Bigness, Katrina, Conflict, Hybridity, & Audience

All

my daydreams are disasters

She’s the one I think I love Rivers burn and then run backwards For her, that’s enough.(1)

— Uncle Tupelo, “New Madrid” 1993

18

Introduction

AR+D Publishing

Bigness

Implies a web of umbilical cords to other disciplines whose performance is as critical as the architect’s: like mountain climbers tied together by life-saving ropes, the makers of Bigness are a team… Beyond signature, Bigness surrenders to technologies; to engineers, contractors, manufacturers; to politics; to others. It promises architecture a kind of post-heroic status—a realignment with neutrality.(2)

Katrina

Early in the morning on August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast of the United States. When the storm made landfall, it had a Category 3 rating on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale—it brought sustained winds of 100 to 140 miles per hour—and stretched some 400 miles across. The storm itself did a great deal of damage, but its aftermath was catastrophic. Levee breaches led to massive flooding, and many people charged that the federal government was slow to meet the needs of the people affected by the storm. Hundreds of thousands of people in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama were displaced from their homes, and experts estimate that Katrina caused more than $100 billion in damage.(3)

- https://www.history.com/topics/natural-disasters-and-environment/hurricane-katrina

19

- Rem Koolhaas, “Bigness, or the problem of Large,” in S,M,L,XL, 1995

AR+D Publishing

For context, two moments have led me to question my role as an architect in relation to larger, contemporary issues of the built environment, and by extension why architects, as well as other design disciplines, should be part of such efforts. At first glance, both may seem an odd couple, and a borderline, let alone superficial way to theoretically underpin a book about water-based design. But in all honesty, both are how I came to this body of work, so it’s kind of personal, and please take it as it is.

1) The publication of S,M,L,XL in October 1995, featuring Rem Koolhaas’s manifesto Bigness, or the problem of Large.

2) The landfall of Hurricane Katrina just outside of New Orleans in August 2005.

In “Bigness,” Rem Koolhaas specifically targeted architects to surrender to complex modes of technologies, politics, and economics. When the essay was published in 1995, it was set within emerging issues of globalization in the 1990s, that is emerging at least to the architecture discipline. At the time, I was an architecture student and fascinated by Koolhaas’s provocation, albeit with naïveté. As he states in the above quote, Koolhaas challenged “the makers of Bigness [to be] a team.” But as time has passed and as I have moved through my academic and professional career, I now wonder if Koolhaas was actually charging architects to work outside of the scale of a building, or just to better work with consultants to design bigger and bigger buildings. And bigger buildings that

20

New Orleans, Louisiana, 2005 (image credit: Derek Hoeferlin)

AR+D Publishing

ultimately could consume the notion of the city, or become the city? All the while, set within a globalized, neoliberal economic context? I argue that we (architects, landscape architects, urban designers) need to go “Way Beyond” what I believe can be regarded in our contemporary context as a myopic definition of “Bigness.”

Rather, specific to the themes I present in this book, the contemporary question to ask is: Why should the term architecture, or any design discipline for that matter, be part of river basin–scale decision-making? And ones, particularly in the United States, that are designed both in policy and physicality through engineered forms?

In order to address the complex challenges impacting multiple scales set within river basin contexts, I believe a new synthetic notion of architecture, as well as landscape architecture, urban design, and other design disciplines needs to emerge and work far beyond an envelope of a building, or a definition of a landscape, or a boundary of a city, or a predominantly engineered system.

Designers need to be part of a new type of interdisciplinary, trans-boundary, decision-making design table. This table is a messy one for sure, and one rife with conflict. But designers possess a particularly unique toolset to negotiate possibilities within such a milieu.

Ten years later, in 2005, Hurricane Katrina catapulted the fields of design into an unprecedented human-altered “natural disaster,” and as such, challenged designers to prove their relevance. Although still the costliest “natural disaster” in U.S. history, we would soon realize that Hurricane Katrina was not just a one-off, let alone a disaster specific to the Gulf Coast of the United States, or other coastal contexts for that matter. Since Katrina in 2005, and especially since 2008, frequent extreme weather events and water-related catastrophes in the United States—both coastal and inland—have repeated over and over and over again. Couple this with the accelerating realities of the effects of climate change and crises in the U.S. and elsewhere, and we can only assume that more events will continue relentlessly and with intensity. While Koolhaas does not refer to water in “Bigness,” Hurricane Katrina was almost all about water. But both “Bigness” and Katrina are definitely what I define as “watershed,” or tippingpoint events for the design disciplines, and more selfishly for my research interests as an architect. To repeat, although Koolhaas targeted architecture in “Bigness,” I extend this is not limited to the discipline of architecture.

Highlighting U.S. water-based catastrophes since 2005:4

(NOTE: these do not include other water-based catastrophes representing lack of water, such as droughts or fires.)

2005: Hurricane Katrina, Gulf Coast ($125 billion USD damage, tied for costliest in U.S. history, 1,833 fatalities)

Hurricane Rita, Gulf Coast ($18.5 billion USD damage, 120 fatalities)

Hurricane Wilma, Florida ($22.4 billion USD damage, 62 fatalities)

2008: Hurricane Gustav, Louisiana ($8 billion USD damage, 153 fatalities)

Hurricane Ike, Texas ($34.8 billion USD damage, 195 fatalities)

Mississippi river spring floods

21

AR+D Publishing

Definitions

Watershed, Architecture

Way Beyond Bigness

Water is the reason we can say its name.(1)

— Edward Burtynsky, Water, 2003

44

AR+D Publishing

An area or ridge of land that separates waters flowing to different rivers, basins, or seas.

- Oxford Dictionary

An event or period marking a turning point in a course of action or state of affairs.

- Oxford Dictionary

Tonle Sekong River, Stung Treng, Cambodia, 2011

(bottom) Lower Ninth Ward neighborhood, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2005

(images credit: Derek Hoeferlin)

AR+D Publishing

45

wa · ter · shed wa · ter · shed

Watershed = Flows + Tipping Points

The

[WBB] questions why a watershed’s principle definition is “an area or ridge of land that separates waters flowing to different rivers, basins, or seas.”3 The scientist-geographer John Wesley Powell contextualized watersheds further, with his ubiquitously referenced view:

That area of land, a bounded hydrological system, within which all living things are inextricably linked by their common water course and where, as humans settled, simple logic demanded that they became part of a community.4

Powell emphasizes a watershed’s potential to prioritize a community’s interaction— and I would add manipulation—within the hydrological boundary of a certain scaled watershed. In other words, what Shafiqul Islam and Lawrence E. Susskind, in Water Diplomacy: A Negotiated Approach to Managing Complex Water Networks, interpret as the coupling of the natural and societal domains.5 But for designers, what skill sets can we contribute to better enable a watershed’s integration within the realities of the built environment, many of which do not obey the logic of hydrological boundaries? And by extension, how can a better appreciation for watersheds make us better designers? These realities include the need for designers to engage contested issues such as architecture, infrastructure, landscape, urbanism, regimes of control, societies, politics, community advocacy, and climatic and/or geopolitical influences, all of which may reside within or outside of a watershed. The alternate, and possibly just as important definition for a watershed, is “an event or period marking a turning point in a situation in a course of action or state of affairs.”6 A definition not about water per se, but rather one having to do with major jolts, or minor glitches, in what seem to be ordinary states of affairs. Think major jolts like a hurricane, or minor glitches like a tweet. Either have consequence, be they positive or negative, visible or invisible, immediate or distant, fact or fiction, and they can be what

46

tipping point is that magic moment when an idea, trend, or social behavior crosses a threshold, tips, and spreads like wildfire.(2)

— Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, 2000

AR+D Publishing

Malcolm Gladwell refers to as a “tipping point … that magic moment when an idea, trend, or social behavior crosses a threshold, tips, and spreads like wildfire.”7

[WBB] questions why architecture’s principle definition is the “practice of designing and constructing buildings.”8 Although this disciplinary strength remains the priority for most architects, it also reinforces the discipline potentially operating in a silo, and dangerously out of touch. Maybe a more pertinent question is: what really constitutes a “building”?

The National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) elaborates on what licensed architects are responsible for:

Licensed professionals trained in the art and science of the design and construction of buildings and structures that primarily provide shelter. An architect will create the overall aesthetic and look of buildings and structures, but the design of a building involves far more than its appearance. Buildings also must be functional, safe, and economical and must suit the specific needs of the people who use them. Most importantly, they must be built with the public’s health, safety and welfare in mind.9

AR+D Publishing

The last sentence is crucial. Not only is it a legal mandate, at least in the United States, but it raises three important external influences—health, safety, and welfare. These are complexities that can be considered outside the realm—or enclosure—of a building. [WBB]

47

Sand pile full of oil, BP Oil Spill cleanup, Grand Isle, Louisiana, 2010 (image credit: Derek Hoeferlin).

AR+D Publishing

152

Pool 25, Mississippi River, Missouri/Illinois, 2017 (image credit: Derek Hoeferlin)

AR+D Publishing

153

AR+D Publishing

197

AB.8221 (image credit: Jennifer Colten)

Mound.8714 (image credit: Jennifer Colten)

AR+D Publishing

198

AB.8447 (image credit: Jennifer Colten)

AB.8027 (image credit: Jennifer Colten)

200

[Figure 1] Levee separating Chain of Rocks Canal (left) and Chouteau Island (right), Illinois, 2019 (image credit: Jess Vanecek and Derek Hoeferlin)

[Figure 2] Floodwall separating Mississippi River (left) and Chouteau’s Landing (right), St. Louis, Missouri, 2019 (image credit: Jess Vanecek and Derek Hoeferlin)

AR+D Publishing

AR+D Publishing

201

[Figure 4] Gas Station at Alton Slough, West Alton, Missouri, 2019 (image credit: Jess Vanecek and Derek Hoeferlin)

[Figure 3] Floodwall separating Mississippi River (left) and East St. Louis (right), Illinois, 2019 (image credit: Jess Vanecek and Derek Hoeferlin)

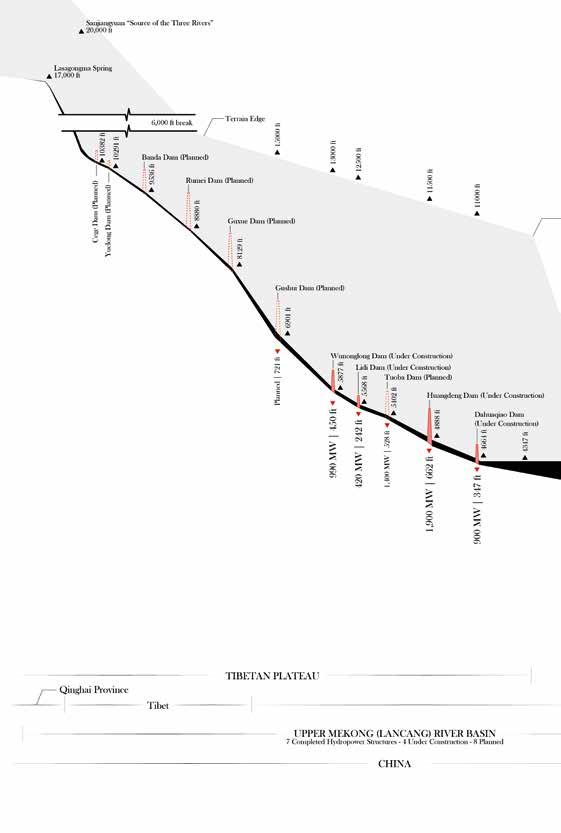

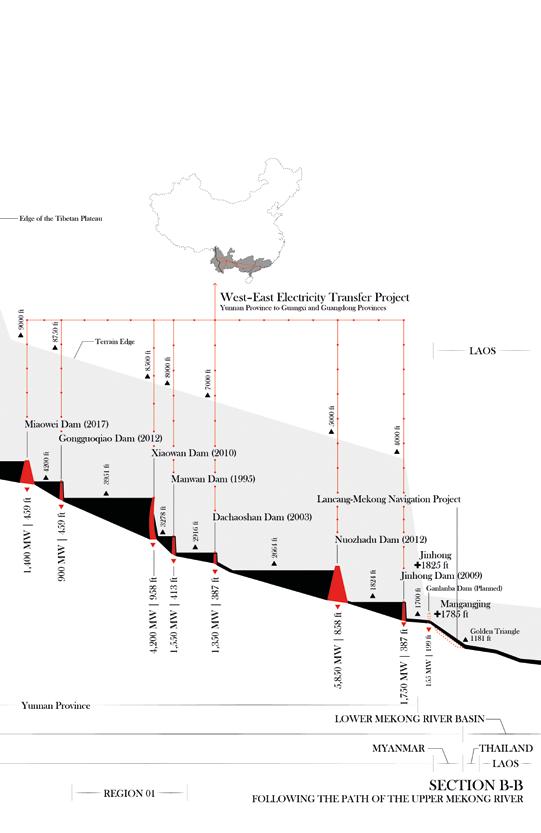

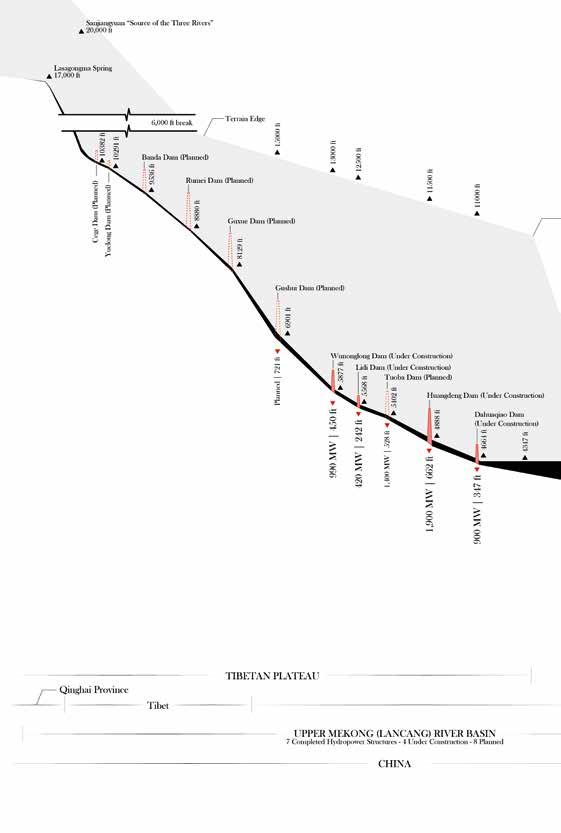

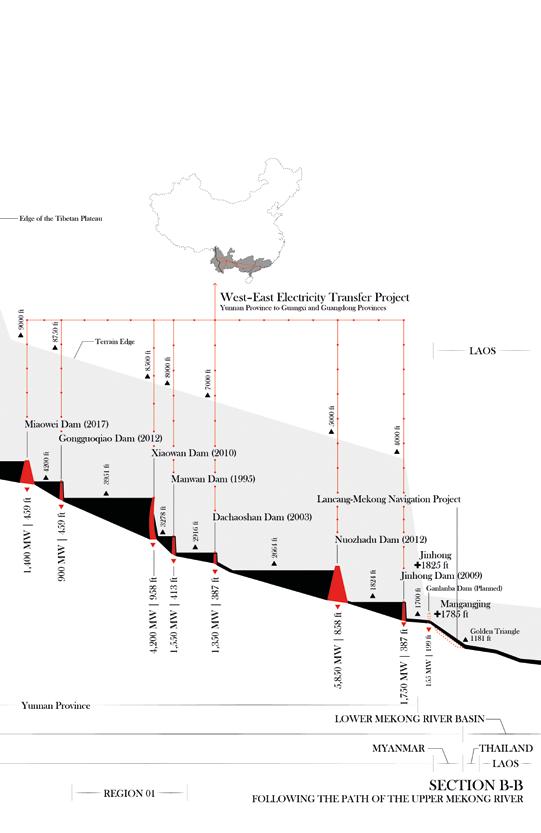

Territory 01: Upper Mekong River Basin

Territory 01 Plan

The Upper Mekong River Basin (UMRB) is a long and narrow territory, geologically shaped by the region’s steep terrain, and altered by recent main-stem developments. The path of the upper portion of the Mekong River begins in China’s Qinhai Province in the Tibetan Plateau and concludes at the tri-border point of Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos, known as the “Golden Triangle.” The upper stretch is approximately 1,400 miles and drains an area of 73,000 square miles.1 It accounts for more than half of the total length of the entire river, but only a quarter of the drainage basin. Both the upper Mekong River and its watershed are almost entirely located in China, which has a regional name for the river, the “Lancang.” The river’s headwaters, the Lasagongma Springs, originate in the Sanjiangyuan (or “Source of the Three Rivers”), where the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers also begin. While the Yellow and Yangtze travel to the east and remain exclusively in China, the Mekong travels in a southeast direction, where it is flanked by the Irrawaddy and Hong (Red) Rivers. Due to the mountainous terrain in this UMRB, only a few small cities have been established in the watershed, but countless villages are dotted along its riverbanks. In total, the UMRB contributes 16 percent of the annual water flow in the river, which peaks at 40 percent during the dry season, and it also supplies up to half of all the sediment in the Mekong River.2 As a result, the UMRB has been disproportionately developed in terms of main-stem hydropower. Since the late 20th century, China has been constructing hydroelectric dams in the Lancang to address both regional and national growth.3 By 2020, seven main-stem hydroelectric dams were completed, with five currently under construction, and seven more planned. All nineteen main-stem upper Mekong River dams are located in China. In the early 2000s, the Chinese government created the state-owned corporation Hydrolancang, which has been rebranded to Huaneng Lancang River Hydropower Inc., tasked to be the sole legal entity responsible for the coordination and development of hydroelectric projects in the Mekong River.4 While China has undeniably benefited from the hydroelectricity generated from the UMRB, a 2008

AR+D Publishing

276

study estimated that the rate of construction would displace 300,000 people by 2020.5 The majority of people who live along the riverbank of the Mekong who have been displaced by the dams are ethnic minorities.6 A developing story strikingly similar to the Mississippi River Basin’s history, the past, present, and future damming of the UMRB will irreversibly change the character of the Mekong River Basin, privileging development, urbanization, and modernization above all else.

Territory 01 Section B-B

Steep and confined in a narrow gorge, the Upper Mekong River Basin is a formidable and impressive landscape. The upper Mekong River begins at an estimated elevation of 17,000 feet, descends 15,800 feet through the mountainous terrain in the Tibetan Plateau and Yunnan Province, then travels as the border between Laos and Myanmar, ending at the “Golden Triangle” intersection of Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand. While the Upper Mekong River Basin only contributes 16 percent of the water to the entire basin, the steep slope grants the main-stem river a significant amount of hydroelectric potential. In Yunnan Province, it is estimated that the main stem of the river has the potential to generate up to 25,000 MW of hydroelectricity.7 By 2020, the seven completed hydroelectric projects were all located in Yunnan Province, and each one is different in size and typology. The hydroelectric projects in the Lancang form a staircase-like cascade of integrated reservoirs, designed to take full advantage of its water storage and maximize hydroelectric generation regardless of the seasonal water flow into the river.8 Together, the seven projects have a combined capacity of 17,000 MW. These projects are part of China’s goal to develop infrastructural projects in its western territories, and have a key role in the West-East Electricity Transfer (WEET) project, concurrently being developed.9 The WEET project consists of new transmission lines that will export power generated from China’s western territories to its urban centers in the east. The power generated in the UMRB will be exported to the southeastern provinces of Guangxi and Guangdong.10 For regional growth, the dams and reservoirs manage downstream flows to also facilitate improved irrigation, navigation, and flood regulation.11 Throughout the process of creating the dams, the projects were criticized for potentially disrupting or harming fish populations and water flows, especially downstream in the Lower Mekong River Basin.12 A recent study of sedimentation in the Mekong River between 1965 and 2003 concluded that mainstem Lancang dam construction decreased the sediment load being discharged into the Pacific Ocean by nearly 25 percent, and expects such phenomena to be worse in the future.13 As a result, the Chinese government has been intensely scrutinized by transboundary activists for its perceived irresponsible decisions.14 In a rare critique from a government leader, the Vietnamese president, Truong Tan Sang, implied of China’s Lancang developments, “Dam construction and stream adjustments by some countries in upstream rivers constitute a growing concern for many countries and implicitly impinge on relations between relevant countries.”15 While China has undoubtedly benefited from the damming of the UMRB, these infrastructural projects strain both the natural environment and political dynamics in Southeast Asia.

277

Publishing

AR+D

AR+D Publishing

AR+D Publishing

The Golden Triangle, confluence of the Ruak and Mekong rivers, Laos/Myanmar/Thailand, 2019

The Golden Triangle, confluence of the Ruak and Mekong rivers, Laos/Myanmar/Thailand, 2019

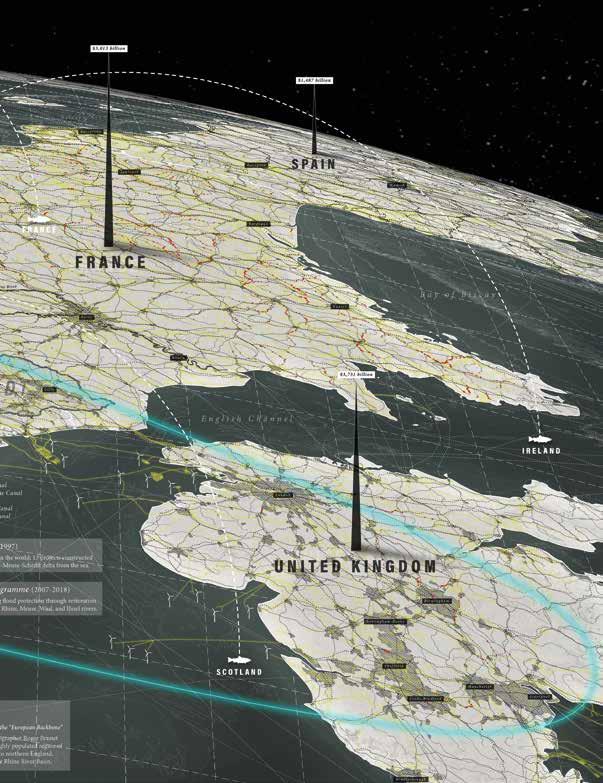

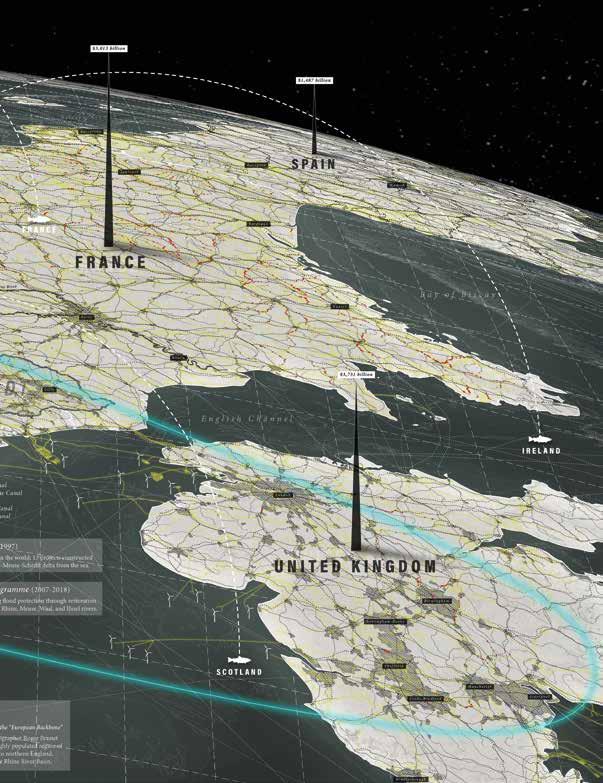

The Watershed Architecture of the Rhine River Basin, situated in context within the central European “Blue Banana” economic and urbanization corridor (image credit: Derek Hoeferlin, Jess Vanecek, Paul Wu, Han Meyer)

AR+D Publishing

522

AR+D Publishing

523

AR+D Publishing

The Golden Triangle, confluence of the Ruak and Mekong rivers, Laos/Myanmar/Thailand, 2019

The Golden Triangle, confluence of the Ruak and Mekong rivers, Laos/Myanmar/Thailand, 2019