THE ARCHITECTURE OF SIR EDWIN LUTYENS COUNTRY HOUSES

I II III

LIST OF ARCHITECTURAL DRAWINGS 8

LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS 9 CHRONOLOGY 11 INTRODUCTION 15

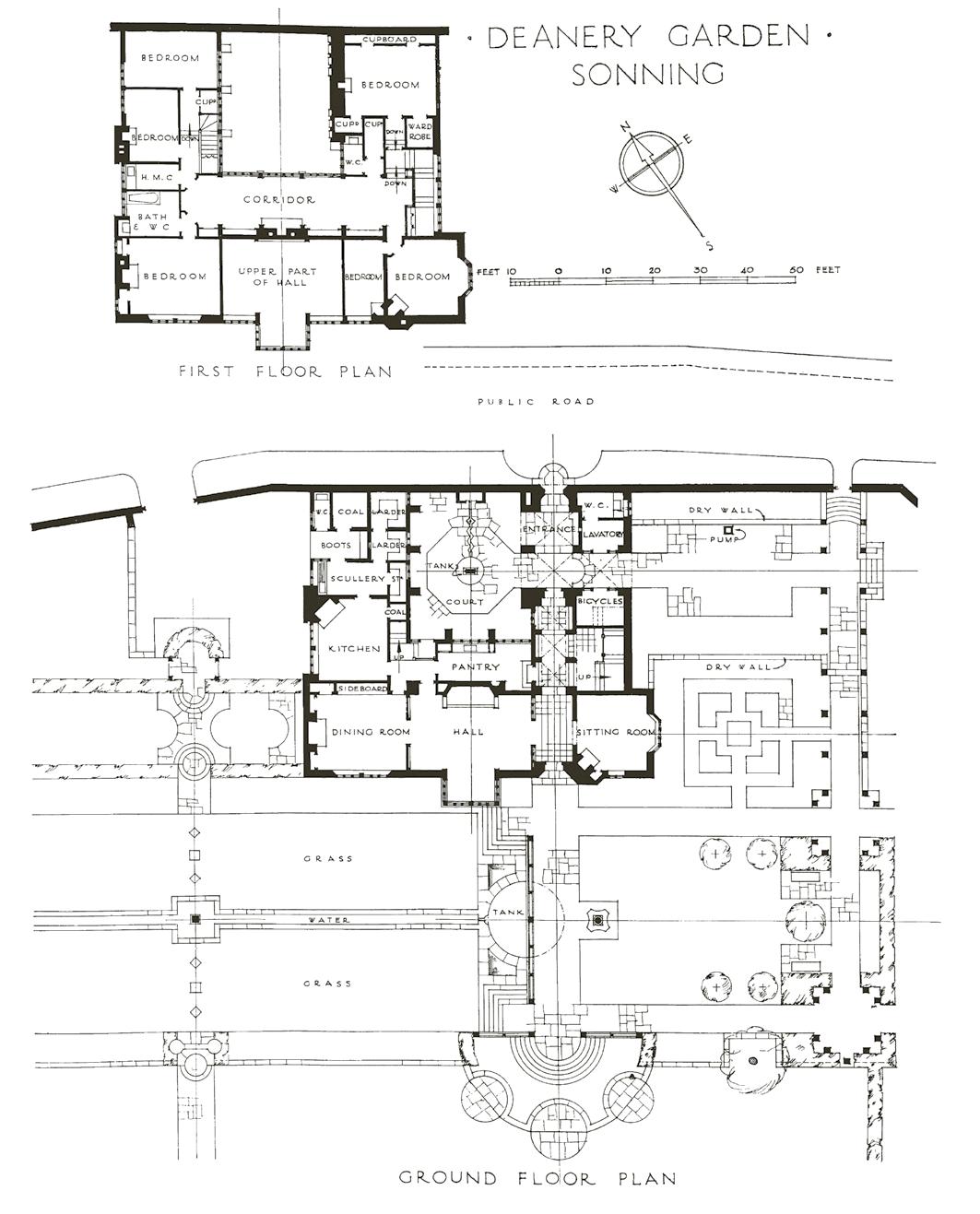

Munstead Wood page 21 Deanery Garden page 25 Orchards 23 Papillon Hall 26 Goddards 23 Grey Walls, Gullane 27

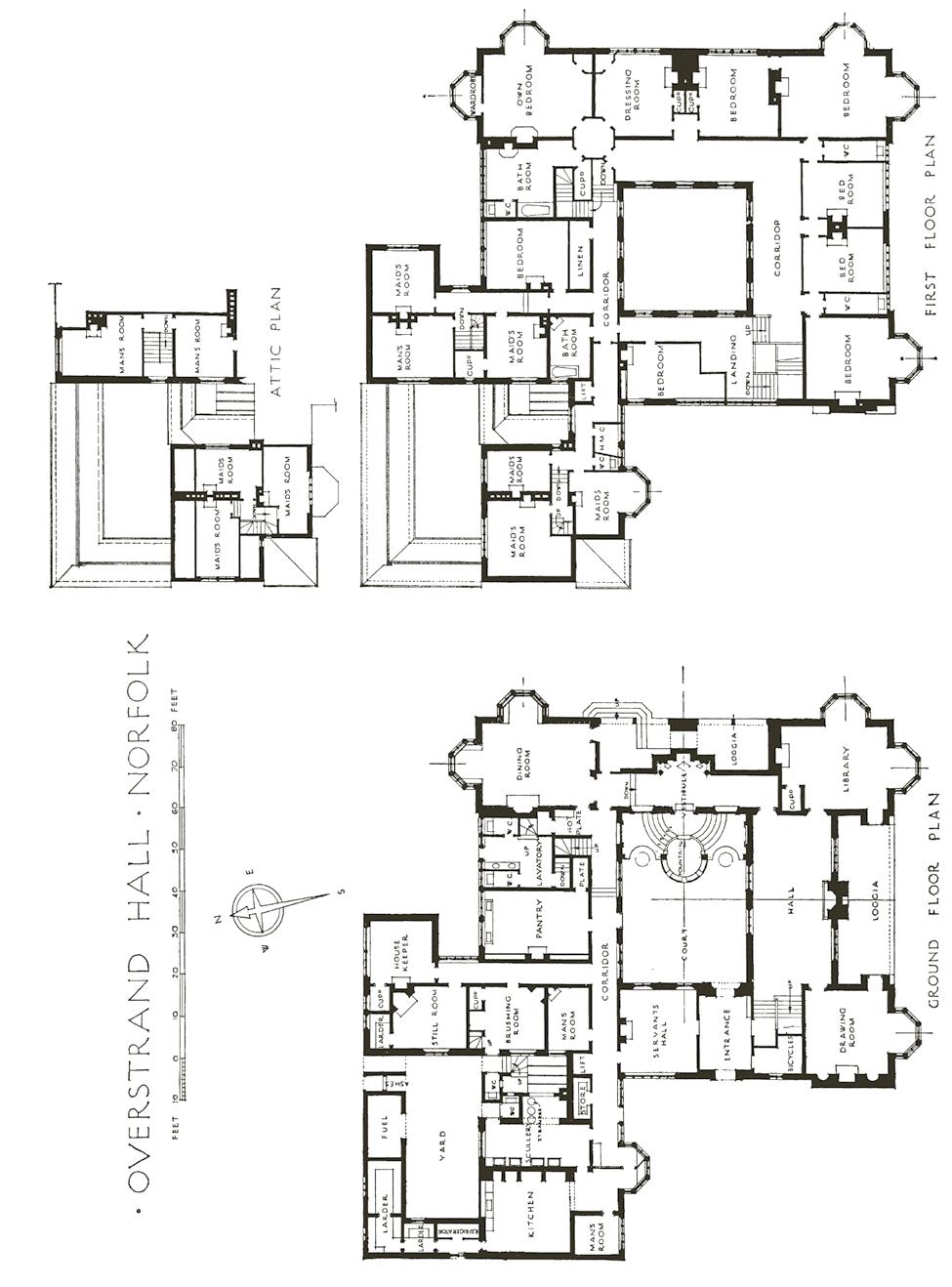

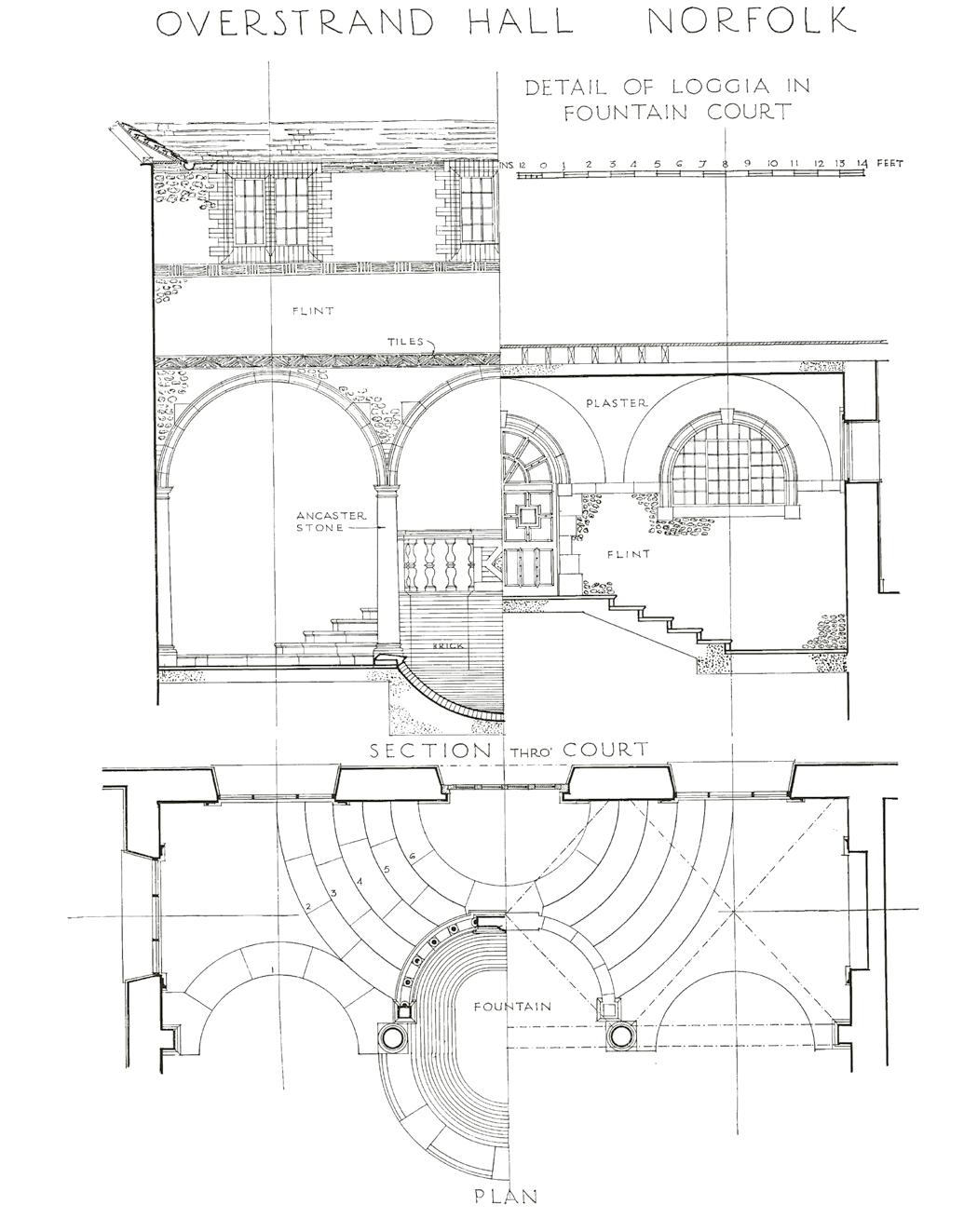

Tigboume Court 23 Marshcourt 27 Overstrand Hall 25 Little Thakeham 28

Homewood page 31 Great Maytham page 36 Monkton House 31 Nashdom 36 Heathcote 32 The Salutation 37 Middlefield 35

Temple Dinsley page 39 Great Dixter page 44 Folly Farm 41 Barham Court 45 Ashby St. Ledgers 42 Ashwell Bury 45 Whalton Manor 43 Lambay Island 45 Saunton Court 43 Lindisfarne Castle 46 Abbotswood 44 Castle Drogo 47

Littlecourt page 50 Gledstone Hall page 54 Ednaston Manor 50 Halnaker 56 Abbey House 52 Middleton Park 56

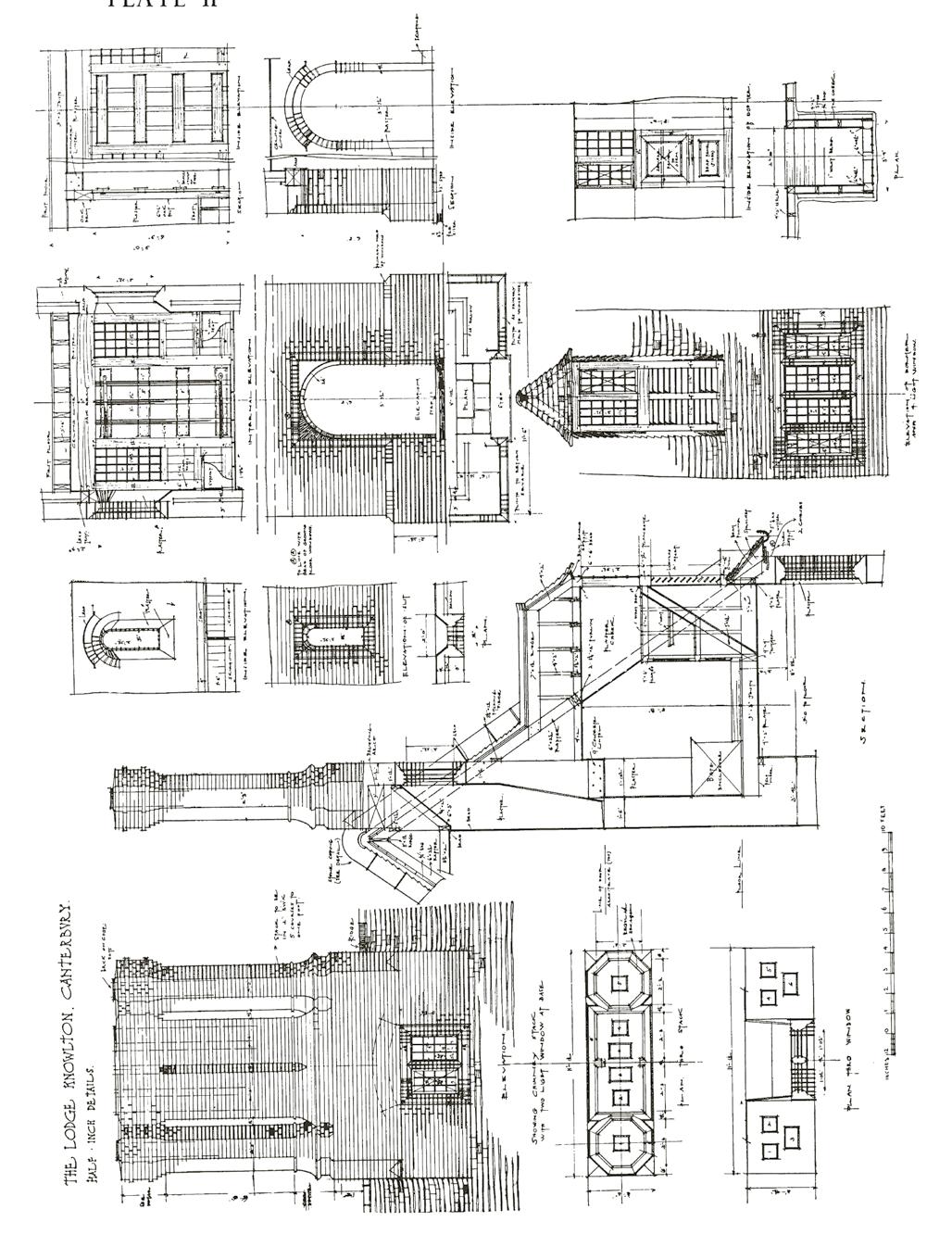

Witwood, Camberley page 59 Cottage at Abbey House, Estate Office, Ashby St. Barrow-in-Furness page 60 Ledgers 59 The Lodge, Knowlton 60

Two Houses at Knebworth 59 Cottage at Gerrard’s Cross 60 Marvells, Sussex 59 Cottages, Plumpton Place 60

Cedar House, Chobham 59 Cricket Pavilion, Reigate 61 Cottages, Ashby St. Ledgers 59 Guest-house, Lambay 61 Gardeners’ Cottages, Ashby The Drum Inn, Cockington 61 St. Ledgers 6o

I

MANY people, in studying the work of one artist, take a peculiar interest in his position in a sequence of other men’s lives and achievements. This is sometimes the only thing that interests them. It is certainly easier to point out that an architect was the pupil of somebody, came under the influence of somebody else or started a particular school, than it is to assess the value of his work as architecture. That is the kind of research many enjoy. The environment from which Lutyens sprang is described in the biographical volume of this memorial; but some indication should be made here of the broad impact on his own development of all the work being done during his youth and just before it.

There are, of course, the direct associations with other architects; but there must have been a strong, indirect influence from the building he saw going on. We cannot conceive him as being wholly oblivious to that. For there was much domestic work being done by men of note both in the neighbourhood where Sir Edwin started and, as well, for the wealthier class of client such as he immediately obtained. Therefore we cannot be surprised to discover that his first houses tended to resemble in design and detail those put up by Richard Norman Shaw, in or near Surrey, ten years or so before.

The house called Merrist Wood, built by the elder man near Guildford in 1878, is an instance. Here you have the whole grammar of a style which has persisted—chiefly in Suburbia—up to the present day. It is basically an irregular Elizabethan idiom of numerous gables, high and expansive roofs always tiled, brick walls sometimes hung with tiles as well, an occasional half-timber interpolation and a crowd of casement windows usually too large and painted too brightly white in contrast with the dark prevailing red. Tall brick chimney-stacks spring from the roofs at unrelated points; and thick creepers are encouraged to confuse and soften the asperities of design or material. Then, internally, there is some Tudor panelling, an abundance of oak darkly polished, a large open fireplace in the principal rooms and the restlessness of odd shelves, fixed high up, with pewter plates and pots strung along them.

That was the type. Norman Shaw did it well; and he must have liked it because, after putting up in 1891 that really beautiful house Chesters in Northumberland, he reverted from a very chaste classical manner there to his neo-Gothic picturesqueness when he designed The Hallams near Bramley (Surrey) in 1894. It was an immensely popular style; and the owner of such a house was considered a cultured man, especially if he could say it was a ‘Norman Shaw’.

This notable, very successful and almost great English architect was born in 1831 and, in 1858, entered the office of George Edmund Street, a leading ‘Gothic’ man of that time and one who could be described most justly as the father of the romantic movement in Victorian design. Street’s supreme work was the London Law Courts, an intriguing mass of building in the dim light of a very early morning but not entirely suitable for its purpose. Philip Webb was also in Street’s office for some years from 1852 and we

shall enlarge on his influence on Lutyens later. Another member of the staff was W. E. Nesfield (born 1834) whose Specimens of Mediaeval Architecture had a considerable vogue.

This romantic movement was, as we know, the effect of a literary pre-occupation in art. It preferred the expression of an associative idea to the sensuous experience of form. A poetic excitement with the past supplanted the aesthetic interest and, encouraged by Ruskin, the qualities of Nature, so analogous to the romantic and the old, distracted our designers further from their primary purpose of pleasing the eye. They even delighted in an accidental crookedness and preferred a miscellany of shapes in natural disorder to any sort of arranged symmetry.

This phase in the story of English architecture was not without its merits. To begin with, it pleased a great many people. That simple statement may sound odd; but it is the first object of architecture to meet the demand of its age, even if that demand be thought, in the next age, a perverted one. And if it is perverted and at a tangent to the—let us say—spiral development of a main tradition, it is not impossible for a gifted man to meet the demand, not only fully, but beautifully. Secondly, these houses at their best always merge admirably into the English setting. Their long sloping roofs anchor them to the site; and their very irregularities meet the accidental lines of tufts of hedge, small woods and rocky ledges. Then the colour of their materials takes on, in age, a tone almost similar to that of the surroundings, and these buildings very rarely startle us. That is, they call attention to themselves less than a white stone or stucco mansion of the eighteenth century, standing haughtily in a wide expanse of park. And, thirdly, the pursuit of this romantic mode forced our architects to cultivate a real knowledge of the country’s natural building materials and all the tricks of their local use. That, indeed, was a contribution, and it was one of which Lutyens took instant advantage.

We can think, then, of that romantic outburst as a kind of infection which the architects of this country caught during the second half of the nineteenth century. Many of them succumbed to it; but the best, like Norman Shaw, were able to shake it off when the occasion arose and reassert themselves as heirs of the Renaissance. Instances of this in Shaw’s career—as well as Chesters—were the London house No. 170 Queen’s Gate, the country mansion Bryanston in Dorset, the Piccadilly Hotel and—probably best of all—the Gaiety Theatre in the Strand, with its plain round belly, surmounted by a charming circular feature in the Ionic order.

E. J. May, who died a few years ago at a great age, was a man much less well-known. He was a typically able exponent of the picturesque. Nevertheless, all through his life he hoped secretly for a chance to break out into a really rich composition of Roman detail. That he had been a pupil of Decimus Burton in that great classicist’s last years may have been the reason; but the gentle career of this good architect illustrates how the romantic movement in our design was a transient fever more than a fatal illness which—in its after effects—purged Victorian buildings at least of their dullness and, in the end, enriched our technique. It was part

of Sir Edwin’s achievement to graft that enriching on to the main stem of tradition.

Clearly Lutyens was fortunate in having to play an instrument in which, for centuries, the English have taken a peculiar delight. We can, on the whole, be proud of our country-houses as they have developed in the last four hundred years. It is the kind of building which reflects our character well. Its quality is that of intimate charm rather than nobility. And the variety of these houses is surprising and important. We have no stock design for a country-house. Nearly always their design has been influenced in one way or another by the materials available locally. This has been accepted as a limitation, with the result that few even of our greatest mansions are unduly grand. They exhibit hardly ever the dull mangificence of European palaces with their reiterated salons, ending perhaps in one great hall or a chapel. The Continent is dotted with the residences of mediatized royalty and the homes of the higher ranks in the Almanach of Gotha. Small country-seats are relatively rare in Europe: but, in England, the houses of noblemen and the humbler landed gentry have nearly always shared a character of gentle beauty individually expressed. They are superlatively places to live in comfortably; and even the stately eighteenth century houses, like Kedleston or Holkham, had ‘family wings’ in which the owners could escape from the more rigid splendour of the State Rooms. Real pomp in the English country-house is restrained. But elegance is different. That abounds, even in the quite small manors and in poor secluded rectories.

As the wealth of our feudal aristocracy dwindled, the leaders of industry discovered the pleasure to be obtained from possessing a ‘seat’ in the country. They took as much pride in them as the old owners, though their idea of a beautiful house tended to mean a rich and possibly handsome residence. Later still—and up to quite recently—it became the ambition of the average well-to-do Englishman to have what he called a place in the country; and most business men, in 1939, kept their real homes outside London or other big centre and travelled daily to their work in the city.

The period from 1890 to 1914 was probably the richest in the history of the English country-house. The city-men’s residences, fringing large towns and aping—often quite well—the old rural examples, had not developed then quite fully. A country-house in 1900 was still much the same as its predecessors of two centuries. It was the very self-contained home of a privileged class with the intelligence to appreciate a little the fine quality such a setting could give them. The privilege was accepted more than abused. The owners of these houses and lands assumed their right to them; but quite a high proportion understood—more in an instinctive than a learned way—how, at least, such buildings should not look. For anything large, loud and flamboyant was received with ridicule, and a pointed display of wealth in a new building was considered shocking.

Living in these houses depended, naturally, on a plentiful supply of servants. The owners’ lives were filled partly by voluntary work in the County, a great deal by sport and, to some extent, by the sheer act of living elegantly. The dressing-gong, for instance, struck a note (in two senses) which had to be obeyed. Sport, however, dominated most things. It was taken very seriously; and an eminent novelist once said that the best people visited the stables on a Sunday afternoon in the same frame of mind as that in which they attended the village church in the morning.

It was a smooth life and, quite often, as pleasant as any the world could provide. On the whole, too, it was a happy one. There were

class distinctions but little rancour. The footman did not hate the lady of the house when she rang for more coal to be put on. He admitted her incapacity and deftly did it. For the servants were well-treated—as servants, that is. They had, in the greater houses, their own class distinctions, strictly adhered to; and they expected the arrangements and rooms to give this effect. So it will be found that, in the big houses built in the reign of Edward VII, much thought was given to the accommodation of the staff, usually with a view rather to their reasonable comfort than to save labour. For there was plenty of labour available, and devices for saving it were then in their infancy. And that is why, in studying the plans of houses by Sir Edwin Lutyens, we maintain it is important to bear in mind that he belonged to the last years of the nineteenth century and the first years of the twentieth. It was not so much his concern to make these houses easy to live in as to create something very delightful to inhabit. Even in his latest designs, one can discover a certain inconvenience in the placing of rooms. The relation of a servants’ hall to a kitchen, for instance. These were not always contiguous; and meals had to be carried some distance from one to the other. But there was a girl to do that. It was her job. One would not have sacrificed the symmetry of an exterior then, to save her a few steps, as we should doubtless do now. Moreover, Sir Edwin belonged to this society which was rooted in the country-house. He began, therefore, with the advantage of knowing how they were lived in; and his plans exhibit pretty accurately—in their practical aspects—what was considered a first-class machinery of life nearly fifty years ago. That machinery will be found a little rusty now and difficult to keep oiled and running; but it does not alter the fact that these houses, when they were put up, did fulfil their purpose adequately.

The first ten years of Sir Edwin’s career, then, may be described as a blossoming development from these roots. That is to say, he combined a knowledge of domestic building from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries with a complete grasp of how the materials of a locality had been used in the past and could be used by him equally well. He added to an understanding of what the better-off middle-class families wanted an ability to create from that demand considerably more than a jumbled prettiness. He maintained a perpetual interest in the possibilities of beauty in plan, coupled with an appreciation of the English love of gardens and their close intimacy with our homes. That is, Lutyens gave his clients not only what they wanted, but his translation of their wishes was, even in the hands of so young a man, an epitome of what every relatively educated person, in that period of wealth and cheap labour, would have liked. Out of his exercises in meeting this demand on his power, he built up gradually a reputation for going beyond the apt expression of a general trend and for making each of his houses a distinct work of art. For, beyond fulfilling their purpose as durable shelters reasonably arranged and successfully built with materials in the local idiom, they had—for those who could see—an enchantment.

That is—we think—the code word, so to speak. Because it always appeared to us younger men that there was this architectural profession, struggling to do what its clients wanted with varying degrees of success; and then there was Lutyens, rather apart and almost irritatingly so, doing all we tried to do quite easily and— it seemed sometimes—backed by limitless means, yet achieving results which we went out of our way to see and admire with astonished awe. Only a few of us realized then that he worked much

harder than anybody and that he rarely—if ever—thought of much except the designing of buildings.

Figure 1 is a view of Munstead Wood. It is the right sort of view of that house, withdrawn and only partly disclosed. Lutyens built it for Miss Jekyll in 1896, in the clearing of a chestnut copse not far from Godalming: and, in the hands of those two experts, the house and the garden are fused into one work which might have been there for a century. The propriety of the walls in local stone, the steep roofs covered with hand-made tiles and the small brickwork of the chimneys is matched by the degree to which the garden is cultivated while retaining its look of virginal forest. But, on top of that, the eye, following the bent line of the path, dwells with continuing pleasure on the smallness of those six casements perfectly set in a plain gable and —next this and in harmony with its solidity—the massiveness of the great chimney thrusting upwards, a feature which not only suggests—and actually ventilates—a big open fireplace burning wood within, but has in its proportions and lines the utmost aesthetic value.

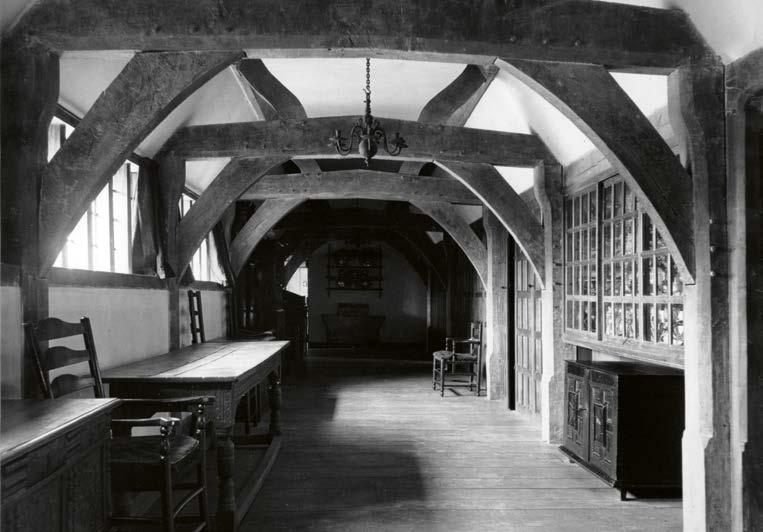

There is more of this quality inside the house as well. Its plan is an unequal H, and the waist is taken up by a hall for general living purposes. This is a long room, about 20 feet wide, with windows on both sides and, naturally, smaller ones to the north. But we are surprised to discover, over this hall, both a bedroom 15 feet wide and the twelvefoot corridor shown on figure 2. One would think that a passage 5 feet wide plus the bedroom, exactly fitting over the width of the hall underneath, was the obvious thing to provide—and quite adequate for a seven-bedroomed house. Anyone else would have been satisfied with that; but it is one of the outstanding notes in Sir Edwin’s work that he did not do the quite obvious thing. In fact, he seemed to go out of his way to create and then solve charmingly a more difficult problem.

This corridor—or rather gallery—at Munstead Wood is a small instance but very typical. Sir Edwin—and probably Miss Jekyll too—wanted something more than a mere passage to link the wings of his house together. So he constructed this inviting gallery to hang nearly 6 feet over the north wall of the hall below. But in doing so—and this is the point—he provided at the same time a covered terrace on which to sit, well sheltered by the two wings of the house and permanently shaded in the hottest weather. One might almost say that he killed here two delightful birds with the one stone of courageous invention.

Figure 3 shows the terrace and the overhanging gallery. It illustrates well that union between house and garden which Lutyens could bring about. They grow into each other, both in design and—as time passes—in fact. But, looking at the photograph, we might criticise the abrupt contrast of the half-timber work with the plain stone walls of the house. Sir Edwin would have avoided that a few years later. But he was not yet thirty when he created Munstead Wood, and he was probably influenced by the emphatic demand for truth in building prevalent at the time. That is to say, we all thought it was more moral—and therefore better art—to allow your construction to show. Fifty years later, in a world of looser moral values, that point of view does not fetter design to the same extent. It has, however, been transformed into another attitude towards architecture summed-up in the awkward term ‘functionalism’. And it is necessary to discuss that here inasmuch as it affects an appreciation of Sir Edwin’s earlier work.

This idea that a building should be ‘functional’ in order to be successfully modern has been developed recently—much more recently than when Lutyens was building his first houses. That point should be noted. It is derived from our living to-day in an age domi-

nated by machines and science. It is maintained that, unless a house looks more like a machine to live in than what it did in preceding centuries, its design should be disregarded as modern architecture. This may be a fallacy. It is at least an exaggeration; just as much as the view taken at the peak of the Gothic Revival when a house was not up-to-date unless it looked like part of a church. Then Pugin would make a doorway to a domestic building so tall and penitentially narrow that you could only pass through it with a wrench. That is analogous to and as strange as those extremely modern dwellings which are so excited with their thin and almost invisible supports, sustaining vast transparent walls between them, that it is difficult to imagine where an occupier could undress with discretion. The one was a submission to the fierce influence of mediaeval art: the other is a surrender of architecture, under the sway of machines, to the ideals of the engineer and the adoption of an aesthetic which insists that the construction of a building be truthfully displayed.

But an emphasis on the claims of naked structure such as this is not quite new and not entirely due to the engineer influence. For it began half a century before their material—steel—had achieved its present pre-eminence. It arose, quite properly, from the discovery and revival of the right use of much older English building materials. It developed gradually from the pleasure we took in the handling of such things as natural oak. This pleasure was such that it became the fashionable thing to show off as many of the structural ingredients of a house as possible; so that, in time, any part of a building which was not actually doing something to support the whole but, instead, exercised a decorative or even a clothing function came to be viewed with suspicion. And, when this was carried to its logical conclusion, we find the walls of rooms left unplastered, so as to show the brick, and ceilings without plaster on them in order to expose the floor joists and, presumably, to obviate our distress at the thought of sand and lime suspended in some invisible—and therefore untruthful way—above our heads. Doors of untouched oak, fitted with noisy iron latches, were admired more than the earlier kind of smooth panelled deal, painted and furnished with a concealed mortice lock. Rough brick openings, with massive oak beams across them, took the place of the older neat iron grates with their falsely grand marble surrounds, because these gaping—and often inefficient—fireplaces showed more truthfully what their intention was and how they were built.

It was, to begin with, a wholesome revolt from mid-Victorian gentility; and the powerful sway of this passion for truth was encouraged by a kind of nostalgic sentiment for the old as such. Beams across a room had to be very heavy and tiresomely crooked, because they looked like the ‘dear old’ beams in a fifteenth-century cottage: and a front-door bell which jangled visibly in the hall, when it was jerked by a bent bit of iron outside, was enjoyed more than the convenient shrilling of an electric bell in the pantry, invisibly worked by pressing a button. The first was the ancient method and therefore good. As well, it displayed the structure of an appliance for drawing attention to a caller at the door and was therefore better still. Even the design of the heavy and entangled bell-pull, inviting a tug, tried to express the purpose of the contrivance. In a word, that bell-pull was ‘functional’.

But not quite in its accepted modern sense. For the tendencies to delight in a romantic past and to recapture its atmosphere by mimicking its architectural character have disappeared, except when a mock-mediaeval style of building is chosen deliberately. A new church, for instance, has to be more or less Gothic because the

2. MUNSTEAD WOOD: THE FIRST FLOOR GALLERY

3. THE SHELTERED TERRACE BELOW

2. MUNSTEAD WOOD: THE FIRST FLOOR GALLERY

3. THE SHELTERED TERRACE BELOW

4.

7 & 8. TIGBOURNE COURT, HINDHEAD, SURREY

9. NEW PLACE, SHEDFIELD, HAMPSHIRE

7 & 8. TIGBOURNE COURT, HINDHEAD, SURREY

9. NEW PLACE, SHEDFIELD, HAMPSHIRE

10. OVERSTRAND HALL, NEAR CROMER, NORFOLK: INTERIOR COURT 11. MAIN STAIRCASE 12. HALL FIREPLACE

10. OVERSTRAND HALL, NEAR CROMER, NORFOLK: INTERIOR COURT 11. MAIN STAIRCASE 12. HALL FIREPLACE

260. SIX COTTAGES AT ASHBY ST. LEDGERS

261. LODGE AT KNOWLTON, NEAR CANTERBURY, KENT

260. SIX COTTAGES AT ASHBY ST. LEDGERS

261. LODGE AT KNOWLTON, NEAR CANTERBURY, KENT

262. PLUMPTON PLACE, SUSSEX: COTTAGES

263. ENTRANCE FROM ROAD 264. FROM BACK OF COTTAGES TO HOUSE

262. PLUMPTON PLACE, SUSSEX: COTTAGES

263. ENTRANCE FROM ROAD 264. FROM BACK OF COTTAGES TO HOUSE

265. PLUMPTON PLACE COTTAGES: THE LUTYENS BRIDGE

266. ROSE GARDEN BETWEEN THE WINGS

265. PLUMPTON PLACE COTTAGES: THE LUTYENS BRIDGE

266. ROSE GARDEN BETWEEN THE WINGS

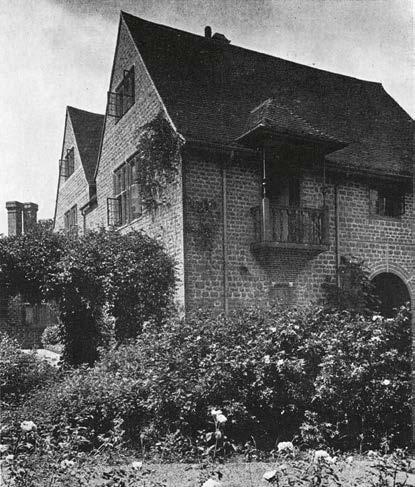

267. GUEST-HOUSE AT LAMBAY, IRELAND

268. CRICKET PAVILION AT REIGATE, SURREY

267. GUEST-HOUSE AT LAMBAY, IRELAND

268. CRICKET PAVILION AT REIGATE, SURREY

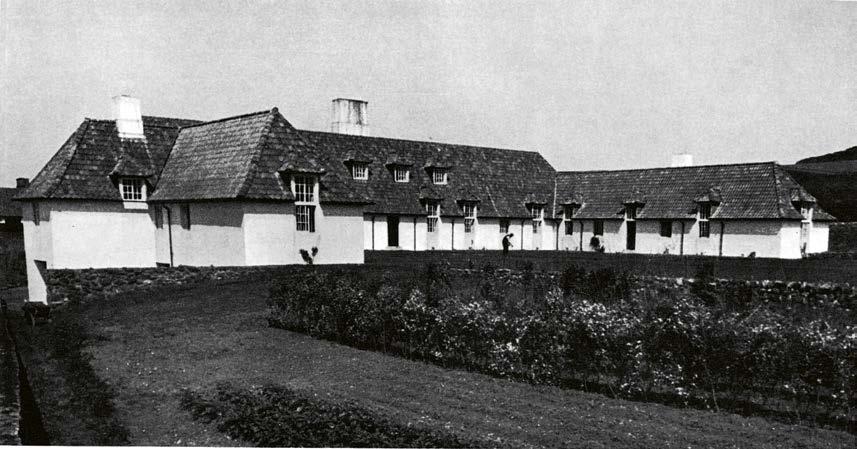

269. THE DRUM INN, COCKINGTON, DEVON: THE ENTRANCE

270. GENERAL VIEW

269. THE DRUM INN, COCKINGTON, DEVON: THE ENTRANCE

270. GENERAL VIEW

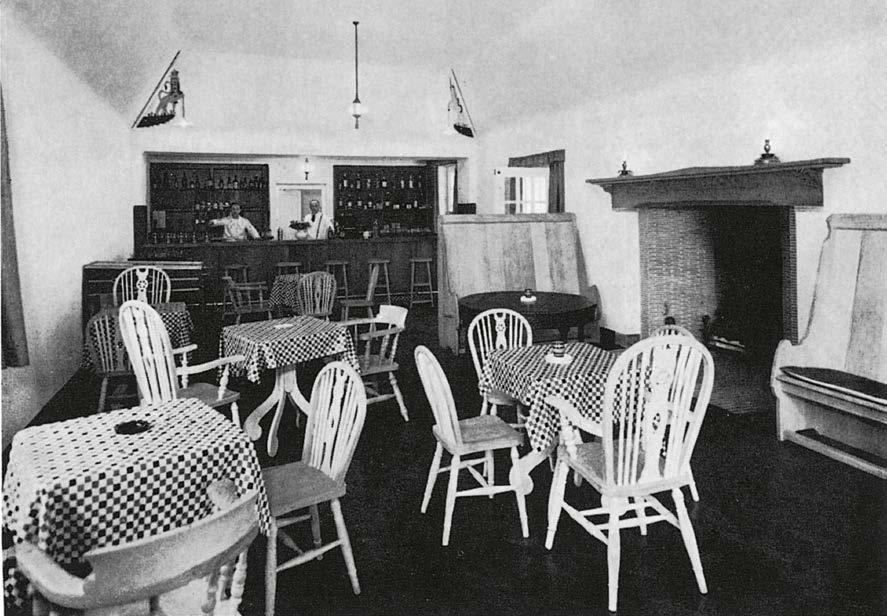

271. THE PUBLIC BAR

271. THE PUBLIC BAR