Copyright © Anthony Rose, 2018, 2024

The right of Anthony Rose to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2018 by Infinite Ideas Limited

This edition published 2024 by Académie du Vin Library Ltd academieduvinlibrary.com

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of small passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978–1–913141–79–0

Brand and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners.

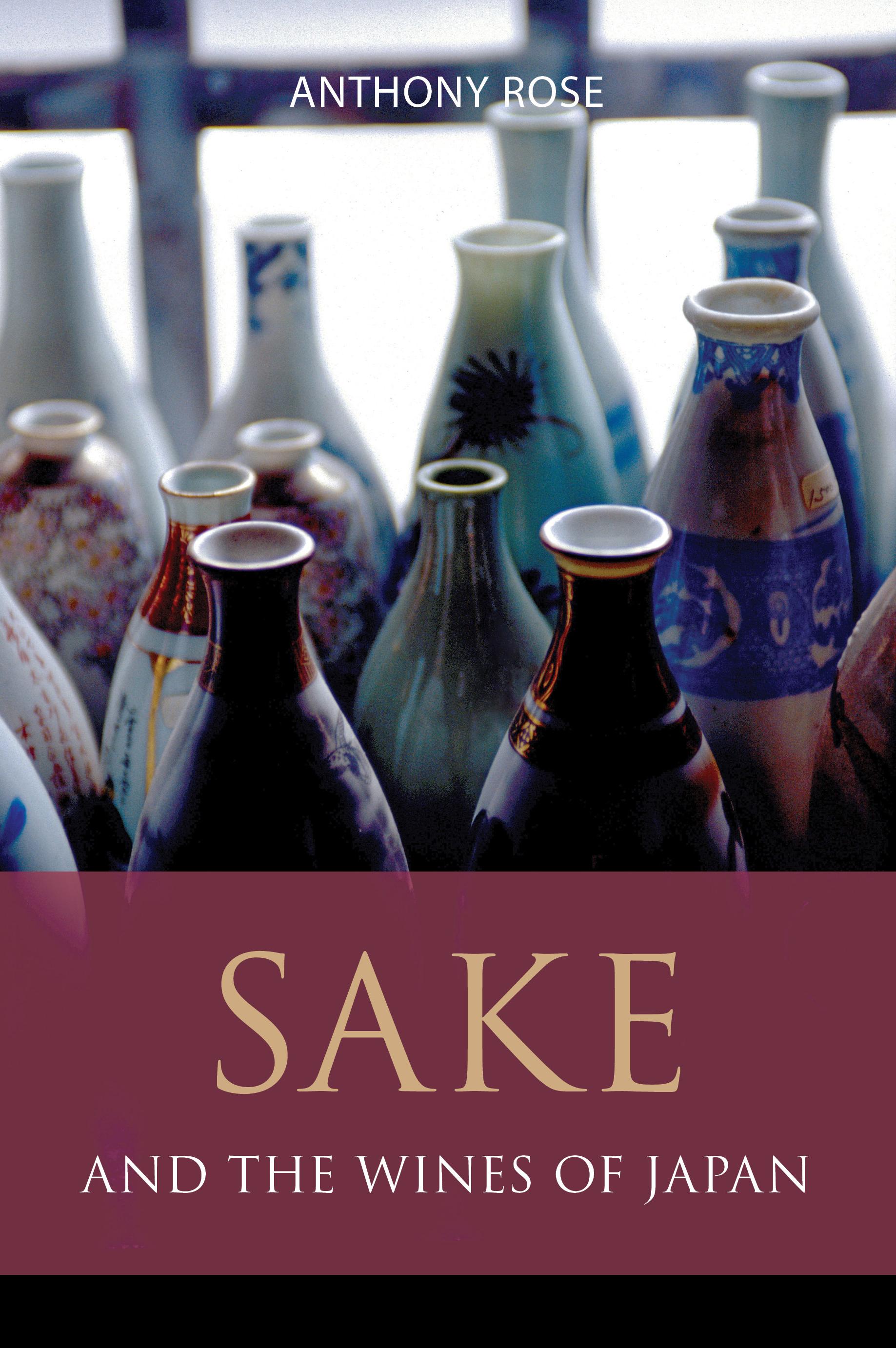

Front cover photo © Ulana Switucha/Alamy Stock Photo

Photo page 111 courtesy of Richie Hawtin.

Photos pages 262 and 280 courtesy of Charmaine Grieger.

All other photos © Anthony Rose.

Maps and illustrations by Darren Lingard; www.darrenlingard.co.uk

Aroma and flavour chart, page 92, redrawn from an original courtesy of Japan Sake and Sochu Makers Association.

All web addresses were checked and correct at time of going to press.

Printed in Great Britain

folklore and superstitions, a paradise of aesthetics that’s rich, diverse, profound, dramatic and tremendously satisfying to explore. In those rare moments that you manage to get under the skin, Japan is a wonder of revelation. And sake?

Sake is both a drink and a window onto Japanese society. In history, legend and ceremony, secular and religious, sake is the lifeblood of Japanese civilization. To delve into sake is to time-travel through centuries of ambition, grit in times of hardship, and outstanding imagination and achievement. Visiting one of the many sake breweries that date back to the Edo period (1603–1868), for instance, is a humbling experience. What extraordinary spirit lies behind an endeavour that has managed to survive, navigate and adapt its way through the challenges and hazards of the centuries to bring us the sake that we so enjoy today?

Family heads are justifiably proud of the fact that they are the umpteenth generation of the family to be running their brewery, although in many cases their families started up in other trades, such as soy sauce making, dried herring production or kimono sales. The traditional nature of the Japanese sake industry inevitably seeps through the pores. At one sake brewery, when I asked the president’s son the name of the tōji, the head brewer, he told me instantly, of course, but it was the tōji’s surname. He had to look up his first name. At some breweries, when it came to tasting their sake, tiny plastic cups were apologetically produced, not even an ochoko (sake cup) or wine glass, allowing little in the way of aromatics and flavour to emerge.

The aristocracy of the sake industry mirrors the traditional château system in Bordeaux, with a landed gentry aloof from its customer base. The big difference is that the Bordeaux aristocracy used the merchant classes to set up an enduring commercial network by which it became pre-eminent in selling its wines successfully not only in France but overseas. For the often insular landed gentry of the sake industry, exporting their products more likely meant selling them outside the prefecture of production to Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto. It is also the case that the sake industry has suffered a series of crises that might have led to terminal decline, had it not been for the foresight and ambition of a new generation determined to exorcise past demons and restore commercial success.

Traditionally, the sake industry is conservative and closely regulated by the tax authorities. As recently, in sake history terms, as the

aftermath of the Second World War, sake had become an endangered species. With a desperate shortage of the necessary raw materials, many breweries went to the wall or merged with others. Overdilution with alcohol and tarting up with sugar and acidity created a massive industry hangover that endured for decades to come. It’s hardly surprising then that sake lost its status as the national drink of choice in Japan. Since a peak of 17 million hectolitres in 1975, sake consumption in Japan has fallen year on year, so much so that the Japanese now drink just a third as much sake as they did 30 years ago – at a time when it accounted for a quarter of all alcoholic drink sales.

Yet for all that, while the image of sake took a knock and the industry spiralled into decline, the last two decades have seen a Phoenix-fromthe-ashes-like revival, with sake sales rising since 2011, principally in the all-important premium sector. When consumption tax rose from 5 to 8 per cent, it was claimed that a 1.8 litre bottle at over ¥3,000 (around £20.50) wouldn’t sell, but it did. Exports too are on the move, rising to an all time high of ¥18.17 million in 2017, with their value more than doubling in the last ten years.

How has this occurred? Old heads are rolling in favour of a younger, more open-minded generation. The early 1990s saw a rapid change in the traditional tōji system as family heads who’d been to university became their own brewers. According to the sake expert John Gauntner, ‘no longer does a brewery-owning family need to rely on an old codger from the boonies with a thick country accent. Just send the kids to brewing school, and keep in touch with friends running other breweries. That flow of information, and lots of patience and experience, is very commonly how sake is brewed in this modern era’.

The modern outlook is for brewers to support local rice growers and pay closer attention to, even integrating in some case, their sources of supply. As younger, educated brewery heads have taken over from their parents, their experiences abroad of other industries, such as wine, and the growing popularity of Japanese food, have given them the confidence to be more flexible in trying out new techniques, crafting new styles of sake, and adapting to a revival of interest from an eager younger generation of consumers. Revolutionary changes in technology, combined with the virtues of resilience and an increasingly go-ahead approach have played their part in the reinvention of Japanese sake in a

Q: How many calories are there in sake?

A: Typically, a honjōzō sake at 15% abv will contain roughly 100 calories per 100 ml.

Q: Is the polishing ratio a reliable guide to sake quality?

A: The polishing ratio (seimai-buai) is the percentage of white rice to brown rice after polishing to reduce the protein, mineral and lipid content. It’s an indication of quality, but to single out the polishing ratio as the be-all and end-all would be wrong.

Q: Does sake have regionality, like wine?

A: In general, it’s fair to say that there are regional differences but they’re not as pronounced as those of wine.

Q: Should sake always be drunk from a traditional Japanese cup (ochoko) or is a wine glass acceptable?

A: Sake can be drunk from any vessel you like and there are arguments in favour of both.

Q: Is it OK to drink sake warm or is it considered naff?

A: There’s still a prejudice against hot sake but it’s more than OK to drink sake warm, or hot, up to 50°C.

Q: Is sake better drunk with food, or on its own?

A: Low in acidity and high in umami savouriness, sake is a versatile drink that goes especially well not just with Japanese food but also with many Western foods.

Q: Should sake be drunk right away or cellared?

A: Most aromatic ginjō and daiginjō sakes are designed to be drunk chilled and are generally better drunk young, but as in all things sake, there are exceptions.

Q: Is sake good value and where can I buy it?

A: Sake is good value in Japan, but transport costs, profit margins and excise duties can make it expensive overseas.

Q: Is drinking sake good for your health?

A: Sake doesn’t contain the sulfites or other preservatives found in wines that can contribute to hangovers and other health problems. Having said that, like any alcoholic drink, sake should be drunk in moderation.

3 WHAT SAKE IS MADE OF –THE ELEMENTS

THE RICE REPORT

‘Do not waste a rice grain; do not treat a rice grain without respect; because the spirits live in there.’

Japanese proverb

Japan loves its festivals and the sake industry is no exception. One of its firm favourites is the Yamada-nishiki Rice Festival in Yokawa, which brings in 10,000 visitors over a weekend in March from local towns and villages in Hyōgo Prefecture. With food stalls, a vegetable and fruit market, sake-related displays and games and other activities for children, it’s a fun day out of Kobe and surrounds. There are booths where you can try different sakes, with explanations as to how sake is made and the importance of Yamada-nishiki to sake.

Hyōgo Prefecture is the stronghold of Yamada-nishiki rice and Yokawa is the capital of thirty-eight villages boasting the special A-grade designation for Yamada-nishiki. Other varieties are grown in Hyōgo, notably Gohyakuman-goku, Hyōgo-kitanishiki and Fukunohana, Hyōgoyumenishiki and Hakutsuru-nishiki, but Yamada-nishiki is king.

Ioo Toshihiro is a local rice grower with 1 hectare of Yamada-nishiki, which is roughly the average if you’re a rice grower in the area. From his single hectare, he produces around 4.3 tonnes of rice, which yields the equivalent of between 4,000 and 10,000 72 centilitre bottles of sake, depending on the processes used and the required grade. The price he gets is some ¥25,000 (£170) per hyō, or 60 kilogram sack. That’s around

break down starches as they grow. Japan’s ingredient du jour, shio kōji, is increasingly being used by professional and home chefs as an alternative to seasoning, thanks to the benefits of umami that it imparts.

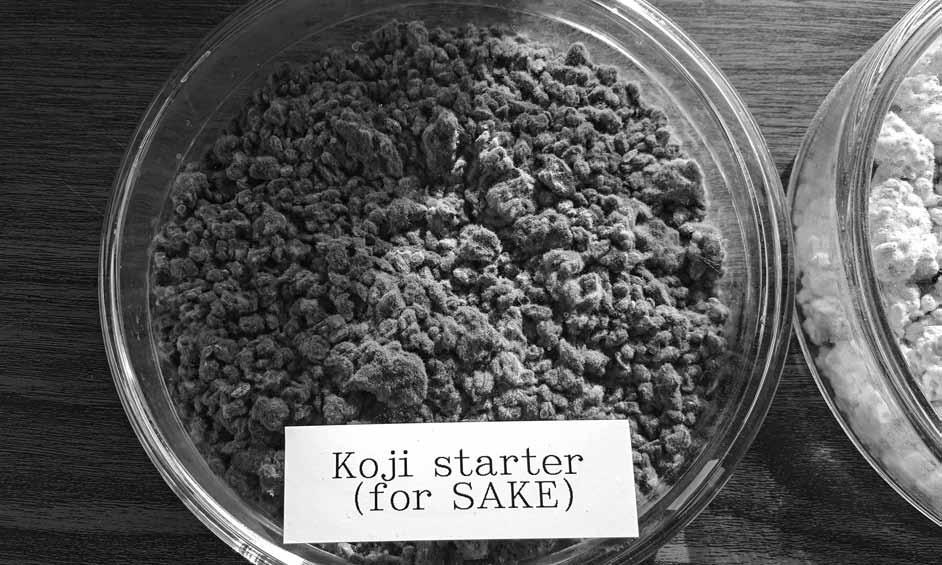

Not that the kōji mould, or Aspergillus oryzae, is confined to Japan. But if it weren’t for these essential micro-organisms used in the manufacture of almost all Japanese traditional fermented foods and beverages, there would be no miso, no soy sauce, no mirin, no shōchu, not to mention no sake. As an indicator of the importance to sake of the kōji mould, there’s a saying in the Japanese sake industry: ‘Ichi-kōji, nimoto, san-moromi’, meaning most important is the kōji, secondly the yeast starter and finally the fermentation.

There are three types of kōji mould, white, black and yellow, and it’s yellow kōji, actually coloured yellowish-green, that’s almost universally used in the sake industry for its low citric acid levels. With their higher acidity, black and white kōji are being used by a few breweries to make a more wine-like style of sake.

In the case of sake, the aim of the filamentous fungus is to secrete saccharifying enzymes, amylases (alpha-amylase and glucoamylase) that shred the starch (carbohydrate) into fermentable sugars (glucose). At the same time, other kōji enzymes break rice proteins down into their

Koshu project, Hiroshima

constituent peptides and amino acids, and these are the basis for the umami flavours in sake. If that’s not enough, kōji mould produces vitamins, lipids, proteins and other subtle aroma and flavour molecules. And it is responsible for flavin, the source of sake’s original pale green colour.

Some Aspergillus strains can have their toxic side, but one of the great mysteries of kōji is that the genes for the poisonous materials have been turned off and, by some microbiological Darwinian survival of the fittest, only the benevolent ones remain. So it is that over the centuries, spores were continually refined in such a way as to produce alcohol or soy sauce and other fermented foods.

In the kōji-making process, kōji spores, so-called tane-kōji, are sprinkled over about a fifth of the just-cooled, steamed, polished rice in the kōji-muro, the brewery’s little sauna, which is a great place to hang out in the cold of winter. In theory. In practice, if the brewery itself has to be as contamination-free as possible, this is all the more so in the case of the kōji-muro, where monitoring temperature and humidity is crucial to the final quality of the rice kōji

The standard volume of spores is 100 grams per 100 kilos of white rice, whereas with daiginjō, most will reduce the volume of spores for the fermentation starter (shubo) and first addition of rice in the main fermentation (moromi) to 30 grams, the middle addition to 20 grams, and the final addition to 10 grams. The still-warm rice is spread out and the kōji mould expertly ‘kneaded’ back and forth so that every rice grain is inoculated. This allows for the growth and extension of mini-feeding tubes, called hyphae, that secrete enzymes that break down the starch.

‘Sake’ made using enzyme preparations to make it cheaper lacks sakelike aromas and can’t legally be called sake. With the advent of specialdesignation sake, the ratio of rice kōji was required by law to be more than 15 per cent. Most brewers use somewhere between 15 and 20 per cent but the proportion rises to 30 per cent in some batches, leading to an increase in umami and richness that might be undesirable in an elegant daiginjō. Since there’s an exception to every rule in sake, there are even sakes made with 100 per cent rice kōji. ‘Very weird but delicious stuff,’ according to the Wine and Spirit Education Trust’s (WSET) Antony Moss MW. A higher rice kōji ratio tends to lead to a fuller flavoured sake with more umami boldness.

KŌJI

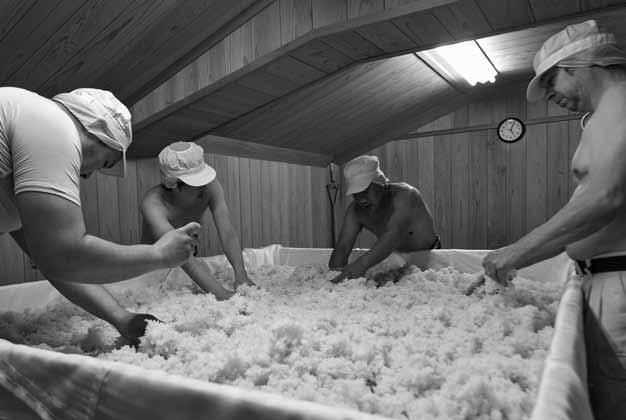

The enzymes for converting starch to sugar for fermentation by the yeast come from the kōji mould. The next step is critical in ensuring that each rice grain so treated emerges after the two-day process with its starch duly transformed. Between 20 and 25 per cent of the total amount of rice destined for fermentation is treated to create kōji, or rice kōji. It is taken to the kōji room (kōji-muro), and spread out on tables where, after it’s sufficiently cooled, it’s sprinkled, as if by a priest waving incense, with the yellow kōji mould. Semi-religious as the process may be, the difference is that as the kōji-muro is at near-sauna temperatures: staff strip to the waist and knead until every rice grain is inoculated before being bundled up to keep warm.

Working the kōji rice rice in the kōji-muro

After waiting about 24 hours to ensure every grain of rice has mould growing on it, the next step is to manage precisely how the mould grows within each grain. To achieve this, the rice is spread out and put into trays, usually the next day, for greater control of temperature and moisture. How labour intensive the process is depends on the type of sake the brewer wants. In the most labour-intensive process, the kōji rice is placed into small TV-dinner-size trays (futa), allowing for the handling

The rice is slightly cooled and, in the warmth of the kōji-muro, it is spread out thinly on a table to have the kōji mould spores sprinkled onto it and kneaded into it. It is wrapped in cloth to keep it moist and ensure evenness of temperature.

10–12 hours later, the inoculated rice is mixed well for evenness of temperature and humidity and bundled up in cloth again. Next day, as the spores have worked their magic, the batch is broken up and placed into small trays or racks to ensure a continuing, even spread of the mould growth.

The contents of the trays or racks are mixed a couple of times, and, thanks to the warmth and humidity of the kōji-muro, the mould spreads through each rice grain until the temperature eventually increases to some 43°C–45°C.

After the two day incubation, the kōji rice is made and ready to be brought out of the kōji-muro and cooled down, when it becomes hard, with a sweet, chestnut-like aroma.

The kōji-making process takes 40–48 hours in the insulated kōji room (kōji-muro)

There are some 20 amino-acids and sake contains a large number in varying combinations. Excessive amino-acid content from minimal rice polishing can lead to an unbalanced sake, whose rough, off-taste is known as zatsu-mi. So sake flavour quality depends on balance, above all of amino-acids and acidity.

The biggest effect is the polishing ratio. A low polishing ratio removes protein, so even if the level of protease in kōji is high, there is little protein to convert into amino acids. Daiginjō sakes then have the least umami and junmai daiginjō sakes are also generally low in umami, followed by ginjō and then junmai / honjōzō. The next effect is dilution. Because it’s full-strength, junmai genshu will have more umami than alcohol-added (aruten) sake. Added amino acids can enhance some futsūshu too. Honjōzō is somewhere in the middle, and junmai and futsū-shu range widely but include the sakes with the most umami (yamahai junmai muroka nama genshu, and rich styles of futsū-shu).

The umami effect, initially perhaps an acquired taste for palates weaned on sugar and fat, grows as your palate develops a taste for more sophisticated combinations of flavour. Complementing umami-rich foods, the umami is heightened. Sybil Kapoor sums up its quintessential savoury deliciousness neatly in Sight Smell Touch Taste Sound: A New Way to Cook: ‘It has a distinctive, easily recognisable savoury taste that makes you salivate and want to eat more, perhaps because it heightens your sensitivity to salty and sweet tastes. It may also lessen your perception of sour and bitter tastes’. Bring the soul of sake flavour to the table and, in combination with the subtleties of the umami in the food, a mouthwatering experience is guaranteed.

THE ALCOHOL CONUNDRUM

Many consumers coming to sake for the first time are unaware of the alcohol content and when they find out are rather surprised. Those who thought it was a spirit are amazed to discover that it’s only 15–17% abv on average. Those who think it’s a wine, a rice wine if you will, are discouraged to find out that it’s stronger than they supposed. So what of the alcohol content of sake?

One interesting feature of sake is that thanks to the fermentation process which continually redoubles the yeast’s efforts to gobble up the

fermentable sugars in the rice, sake ends up at around 20% abv at the end of the fermentation process but is then watered back to the desired alcohol level of some 15–17% abv. Why watered back? Because 20% is strong stuff. Why not water back down to a wine’s equivalent of 12–13% abv when surely that would be more refreshing? The answer comes down to one word: balance. Apart from all the other features a brewer is looking for in his or her sake, balance is not negotiable.

The first duty of most wines is to refresh, with food, and I rarely find a Bordeaux at 15% abv or more, or a Napa Valley Cabernet, at a similar level or higher, refreshing. A Grenache on the other hand, for instance, that needs that extra ripening, just might be. And there are other exceptions. The Veneto’s Amarone is consistently 15% abv or higher because of the concentration of dried grapes involved, but it’s not made to refresh any more than a port or whisky. The Italians have a wonderfully lyrical name for this kind of wine: vino da meditazione.

That’s fine as long as the wine’s in balance where that’s the intended style. A port may not be particularly refreshing but, as long as it’s not heavy and it’s balanced by sufficient acidity, its richness is not designed to refresh so much as give pause for thought, to go with cheese, or to be sipped slowly after dinner. Fortification with alcohol takes fino and manzanilla sherries to an average 15.5% abv and when nicely chilled down on a warm day, preferably sitting in the main square of Sanlucar de Barrameda, manzanilla can be genuinely refreshing.

Sake at 15–17% abv varies considerably in style. There’s a big regional difference between a delicate, pure and drier sake at this level from Akita and Niigata, for instance, in the north of Japan, and a richer, sweeter sake from Saga in the south-west. The grade of sake also contributes to the mouthfeel and the way we perceive the sake. Dextrins are a key feature of sake, and with the glucose, mask the presence of alcohol. A junmai daiginjō may be richer than a daiginjō with alcohol added for fragrance and slightly lighter body. A daiginjō may be richer than a junmai, a pure rice sake designed to go with a greater variety of food than a fragrant daiginjō.

On the question of alcohol, sake and premium sake are divided into two distinct types. On the one hand, there is the world of junmai, or pure rice sake, ascending the grade ladder to junmai ginjō and junmai daiginjō. On the other, there’s the world of alcohol-added sake, rising at

Tamagawa is the brand. A series of wooded buildings and refrigerated containers sit off the road, just a few minutes walk from scenic Kumihama Bay on the Sea of Japan.

Work is already under way as Philip, the only British tōji in Japan, comes out to meet me, a foreman’s cap keeping the tousled Harper mop in place. ‘Breathe in, you’re lucky. It’s normally cloudy and grey, but the air’s good and the sky unusually blue. We’re in end of season mode,’ says Philip, clearly happy that the final yeast starters are on the go.

Philip lives in Osaka but stays at Tamagawa during the brewing season, because the tōji needs to be on the qui vive, up early in the morning, finishing late, and mixing with the brewery staff. Over 15 years, Philip worked at three other sake breweries before joining Tamagawa in 2008 as a fully-fledged master brewer, or tōji, after the previous incumbent, Akio Nakai, passed away.

Philip Harper, Tamagawa

Following his appointment by Tamagawa’s owner, Yoshito Kinoshita, he didn’t bring a team of co-workers with him in the traditional way that head brewers once did when the old guild system was the main source of bringing in a brewing team. A man who had worked at the Osaka brewery with him came too and worked two seasons before retiring. Two men who had worked with Akio Nakai were still there. Hirabayashi, the local man who does the rice polishing, also joined the company the same year as Philip. There was a team of five in his first year, but as the brewery expanded, Philip gradually took on more staff.

As the day’s work gets under way, it dawns on me that everything I learnt on my Wine and Spirit Education Trust (WSET) Sake Level 3 course is going to have to be put on hold. Learning about sake takes you through a chronological process, following the rice grain from harvest to brewery to polishing, to washing, to steaming, to kōji-making, to fermentation, to pressing, to bottling, to market, to table. Convenient as it would be for all these processes to follow each other in the order taught, the reality is somewhat different. Still, knowing the theory has stood me in good stead.

At 8.15 am, the finished kōji, the rice into which kōji mould has secreted its starch-to-sugar enzymes, is arriving by chute from the kōjimaking room (kōji-muro) above, into a large box waiting to be used in tomorrow’s batch. It’s Gouriki rice, each rice grain polished to 71 per cent of its original size. Gouriki, Philip explains, is a rare variety from Tottori Prefecture, which he just happened to be offered so he thought he’d give it a whirl. The box is loosely covered and a fan turned on for the kōji to dry out in preparation for tomorrow.

We’re in the original building, a pretty, wooden structure from the outside, surprisingly airy, spacious and spotlessly clean and functional within. We walk to the new part, built three years ago, which contains the fermentation vats. Two members of staff are taking samples from each for analysis for nihonshu-do, alcohol, acidity and amino-acid content. They measure the temperature in each tank, with a different thermometer and mixing tools for each in order to avoid cross-contamination of different yeasts.

Estery aromas of banana, pear and spice waft through the room. There’s a tank with number 7 yeast, along with an in-house yeast rumoured to be a variant of number 9 yeast for junmai daiginjō, number

yeast but it’s difficult to do it every year. At the moment we’re making three or four tanks each year but that number is growing,’ he says. When he returned to the brewery, Aramasa was using the local soft water for its brewing but he switched to a source of subterranean hard water coming from a well beside the seashore, containing minerals that make the kimoto style easier.

Production today is just 25 per cent of the volume produced when Yusuke returned in 2007, but all Aramasa sake is junmai and its reputation is such that it commands a price undreamt of 10 years ago. ‘We could call it ginjō or daiginjō by grade, but I don’t like the ginjō name. Japanese law dictates the grade but that’s based solely on the rice polishing ratio, so you can have a less good sake at a higher polishing ratio. That’s meaningless. For us, quality is more than just the grade or polishing ratio’. Not convinced that polishing ratios necessarily correspond to quality, he’s polished rice to 90 per cent and 96 per cent in a couple of cases, a two-fingers message to the breweries falling over each other to reach the lowest polishing ratios.

Yusuke becomes even more animated when it comes to the new sake brewery he’s planning. Aramasa buys in its rice, 65-hectares worth of Akita varieties such as Sake-komachi, Miyama-nishiki, Misato-nishiki, and Kairyo-shinko, from local farmers, Aramasa’s own workers, and it has five hectares of its own organic rice fields some 30-minutes drive from the city centre. Yusuke’s new baby is a small sakagura he’s planning in the rice fields, making sake with natural yeasts only, and using Kameno-o, an ancient Edo rice variety: ‘Akita is famous for its rice fields and our rice fields are like Burgundy’s crus, while Yamada-nishiki from warmer Hyōgo is more like Bordeaux.’

Suzuki Shuzoten

Brand: Hideyoshi

9 Aza Futsūkamachi, Nagano, Daisen-city, Akita, 014-0207

Tel.: + 81 187 56 2121; email: info@hideyoshi.co.jp www.hideyoshi.co.jp

If you saw ‘Joanna Lumley’s Japan’, the British actress’s three-part 2016 TV mini-series, you won’t have missed the historic brewery of Suzuki Shuzoten founded in 1689 by the son of a merchant who moved to Akita from Ise Province (modern day Mie Prefecture). The brand Hideyoshi takes its name from the local feudal warlord, Satake, who adjudged

Suzuki Shuzoten’s sake, then called Hatsu Arashi, to be the best in a sake competition, proclaiming it ‘Hide’, meaning extremely and ‘Yoshi’ meaning good. Shortly after that, Suzuki Brewing Co. renamed its sake Hideyoshi, which is coincidentally also the name of the great Shōgun, Hideyoshi Toyotomi. The feudal lord declared Hideyoshi his sake of choice in 1848.

Naoko Suzuki, Hideyoshi, Akita

The brewery’s reputation blossomed in the nineteenth century after the famous tōji Tomoshichiokina Hoshino was invited to Akita to help with the development of sake brewing techniques and settled near Hideyoshi in Nagano village because of the high quality of the water. This pristine, sweet and soft groundwater from the nearby Ōu Mountain range is an astonishing natural blue with the right balance between hard and soft that allows for excellent fermentation and a softness in the

wooded cliffs tumbling to the sea and a misty, undulating green landscape reminiscent of Ireland. During the Edo period, there were 100 sake breweries on Sado. It also became a centre for Noh theatre (some 30 of which still remain), thanks to the government’s despatch of Nagayusu Okubo, a member of a family of actors, to help in the exploitation of the gold mine at Aikawa. Today, quiet village streets lined with timbered shack-style houses and neat front gardens testify to an undramatic picture in which emerald green rice fields and tuna, squid and oyster fishing are the mainstay of the island economy.

Only five sake breweries remain on Sado, among them Obata Shuzo, established by Yososaku Obata in 1892. It continues to use traditional, handcrafted techniques with a particular sensitivity to the local environment. Sado has focused conservation efforts on creating a sanctuary for the Japanese crested ibis, known as toki, an endangered species and the

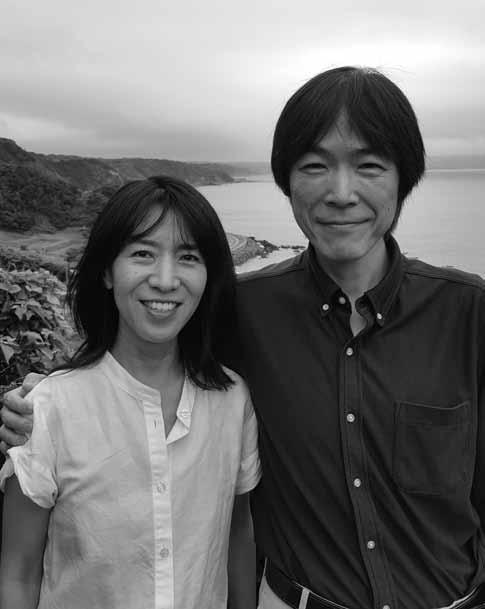

Rumiko Obata and Ken Hirashima, Obata, Sado Island, Niigata

symbol of the island. ‘An island that is kind to the toki is kind to humans as well,’ say Rumiko Obata, daughter of the Mr Obata who gave Angus Waycott the brewery tour, and her husband, Ken Hirashima.

A feature of Obata is the Gakkogura Project, a conversion in 2014 of the abandoned elementary school, Nishimikawa, into a microbrewery. The microbrewery produces sake outside the brewing season and holds an annual workshop, training up sake students, who come from far and wide to learn the craft of sake-making. Obata is open seven days a week and reservations are only needed for bus tours. A few staff speak English. For eating out in Sado, Goshima, Itoya and Chozaburou are recommended. For things to see and do on Sado island visit www.visitsado.com/en/.

Takeda Shuzo

Brand: Katafune

171 Kamikobunatsuhama, Ogata-ku, Jōetsu-shi, Niigata 949–3114

Tel.: +81 (0)25 534 2320; email: s-takeda@joetsu.ne.jp www.katafune.jp/sake.html

Takeda Shuzo is a microbrewery owned by the ninth generation, Shigenori Takeda, and established in 1866 in Jōetsu, Niigata Prefecture, over 150 years ago. Its brand, Katafune, means ‘Lagoon boat’. While the Niigata tanrei karakuchi boom began some two decades ago, Takeda Shuzo stayed loyal to its original style in crafting characterfully bold, umami-rich sake using number 9 yeast, aimed at bringing out the delicious notes of the rice used. ‘To drink Katafune,’ says Shigenori Takeda, ‘is to enjoy the essence of sake.’

The brewery uses Koshi-tanrei rice and smaller quantities of Koshiibuki and Yamada-nishiki with yeast number 9, and its kōji is Akita Ginno. Soft to medium-hard water, which Shigenori Takeda believes contributes to Katafune’s richness and sharpness, is sourced from a subterranean well on the premises. Pasteurization is meticulously carried out by immersion of the bottle in hot water in the bin-hi-ire method.

Takeda Shuzo has won a number of medals for its sake, notably the IWC Honjōzō Trophy for its Katafune Tokubetsu Honjōzō, which is fully deserved for such a high quality, smooth, rich, beautifully balanced honjōzō. The brewery also produces a Katafune Daiginjō Tobin sake, made by the labour intensive drip press method direct to a beautiful turquoise blue bottle.

Edo period, chiku meaning bamboo, while sen, meaning spring (also ‘izumi’ in Japanese), is derived from Izumi (present day Osaka), their ancestors’ birthplace.

Naoko Tajime, Chikusen, Tajime Partnership, Hyōgo

‘No-one forgets their umbrella in this area,’ says the bubbly Naoko Tajime who, with her husband, Hirotaka, is involved in all aspects of the brewery. The son of the eighteenth generation owner, Sadahiko Tajime, was tragically killed in a car crash in 1996. So, in 1999, after meeting her at the National Sake Research Institute in Saijō, Hiroshima, Hirotaka Tajime joined Sadahiko’s second daughter Naoko in the running of Tajime. Hirotaka, whose family brewery, Kanbai, is in Saitama, where he was born, teamed up with Keiji Takahashi, the tōji at Tajime since 2005, and they began focusing on junmai. By 2012, they had decided to brew only junmai sake, in the firm belief that junmai, with its umami

content, is the best marriage with food, not least the local vegetables from the area such as the soft, sweet Iwatsu leeks, and Tajima beef.

The Tajimes are focused on making sake from local rice (98 per cent of the rice they use is local with just 2 per cent from Hyōgo) bought from contract growers. From using only organic Gohyakuman-goku rice konotori hagukumu, they have expanded to organic Yamada-nishiki konotori hagukumu. This is a stork-friendly, pesticide-free rice grown by farms branded Konotori Hagukumu Okome (‘rice to foster storks’) to allow the endangered Oriental White Stork to forage in the natural ecosystem. Konotori hagukumu is the heart and soul of Tajime’s sake and even embodied in the prayers of the local people for a revival of the natural habitat. They also use Omachi, Hyōgo-nishiki, and Dentokoi.

Chikusen Organic Junmai Konotori (15% abv), polished to 40 per cent, is spicy, dry and umami-rich. Chikusen Junkara (jun – rich and flavoursome, kara – dry) Nama Junmai Genshu (18% abv), made from Gohyakuman-goku is a powerful, juicy-textured unpasteurized sake the power of which is offset by its zingy freshness. Chikusen Junmai Daiginjō Konotori Shizuku (the most expensive in the range at ¥21,600, using rice polished down to 40 per cent), is an impressively rich and concentrated sake with real depth and intensity of flavour. The Chikusen Junmai Yamahai Nama, is a super-dry, mellow-textured sake shot through with savoury umami notes. Juicy local plums meanwhile go into their refreshingly sour, home-made-style Umeshu Junmai Yamada-nishiki.

Chikusen is open for visits on weekdays and Saturdays. An appointment is needed and only Japanese is spoken. There is a showcase rather than shop as such, as part of the brewery where visitors can buy bottles of sake. The local area is home to the impressive ruins of medieval Takeda Castle, the Ikuno-Ginzan Silver Mines, Asago Art Village, Asago Geijyutsunomori museum (forest of the arts museum) and the Meiji-era Road of Ores.

Hakutsuru Sake Brewing Co., Ltd

4-5-5 Sumiyoshi Minami-machi, Higashinada-ku, Kobe, Hyōgo, Japan 658–0041

Tel.: + 81 (0)78 822 8921; email: exports@ Hakutsuru.co.jp; soumu@Hakutsuru.co.jp www.hakutsuru.co.jp/english

If Hakutsuru’s cool, young president, Kenji Kano, had wanted to make a point about the growing number of young women drinking sake, he

polishing ratio 82 statistics (2013–2014) 351

typicity 92

see also sake styles sake retailers see sake shops in Tokyo sake shops in Tokyo 334

Ebisu Kimijimaya 335

Furumaiya 335

Hasegawa Saketen 335

Meishu Center Ochanomizu 335–6

Sennen Kojiya 153, 336 Suzuden 336

see also Japan; restaurants in Tokyo sake styles 31–8, 126

bodaimoto 14

genshu (original state) 31–2, 105 ginjō 22, 24, 30, 140, 141, 360 happō-sei-seishu (sparkling) 35–7 of individual breweries see breweries by prefecture jizake (local sake) 26

junmai (pure rice sake) 71, 79, 83–4, 89, 124, 194–5

kimoto 79

koshu (aged) 17, 23, 32–4, 86–7, 353 hizo-shu 240

low alcohol 32 mamushi-zake (a home brew) 159 nama-zake 34–5 nigori-zake 35 otoko-zake 49

tanrei karakuchi 153 taru-zake 37

ume-shu (plum sake) 79, 240 yamahai 79 yuzu sake 79

see also sake grades sake tourism 320–21

Sakurai, Hiroshi 226

Sakurai, Kazuhiro 226–7

Satake, Riichi 21–2

Sato, Joji 128

Sato, Jumpei 142–3

Sato, Yauemon 147

Sato, Yusuke 46, 121–4

Saura, Koichi 138

Sayburn, Ronan, MS 264

Sessen-Junigo area 17

Sherriff, Lynne, MW 263

Shichida, Kensuke 77, 236

Shimakazi, Dai 298

Shingu, Susumu 252

Shirai, Erik, The Birth of Sake 179

Shirakashi, Masataka 199, 199–200

Shiraki, Hitoshi 172

Soga, Akihiko 294–6 Spain 244–5

Stithem, Byron 247 storks 195

Sudo, Gen-uemon 148

Sugarawa, Akihiko 137

Suzuki, Naoko 125, 126

Suzuki, Hiromi 289

Suzuki, Takui 289

Tajime, Naoko 194, 194

Takamine, Jōkichi 22

Takano, Eiichi 302

Takano, Masanari 258, 288

Takasawa, Daisuke 157, 158

Takeda, Shigenobu 270

Takeda, Shigenori 161

Takeshi Sake Bar and Restaurant 107

Takeshita, Masahiko 4

Tamada, Yoshihide 9

Tamamura, Toyoo 301–2

Tamon’in Diary 15 taste 33, 37, 77–80, 85 and aroma 91 umami 80–82 tasting 90–93 sake competitions 93–5 from Tamagawa range 108–9 tax system (Zoukokuzei) 23, 32–3 temperature 95–6 warming sake 96

Teraoka, Yohji 170–71

Tōhoku region 43, 115 tōji

Abe, Takao 150

Akita, Toru 150 Bennett, Brock 243 Conti, Humbert 244 Fujio, Masahiko 134

Harper, Philip 4–5, 27, 32, 50, 77, 85, 97–107, 98

Hoshino, Tomoshichiokina 125

Igarashi, Tetsuro 164–5

Ikeda, Kenshi 230

Imada, Miho 220, 221

Iwabuchi, Toru 209–10

Kiichi 169

Kushibiki, Reiko 252

Kuwabara, Takumi 249

Nakamura, Shinji 211

Ono, Makoto 151

Onodera, Kujio 138

Sato, Takanobu 144

Stithem, Byron 247

Tada, Nobuo 170

Takahashi, Ryoji 129

Tsuji, Maiko 217

Yokoyama, Fukuji 170

Yonezawa, Kimio 192

tōji system 3, 56, 104–5, 113–14

guilds 133, 149, 154, 170, 180

Tokyo see bars in Tokyo; restaurants in Tokyo; sake shops in Tokyo

Toshihiro, Ioo 39–40

Trump, Donald 299

transport 18–19

Tsubosaka, Yoshiaki 214, 215, 216

Tsuchiya, Ryuken 258, 286, 288

Tsuji, Soichiro and Maiko 216–17

Ueki, Noriya 239

United Kingdom 127, 238, 242–3

United States of America 210, 228, 238, 245–53

Vuylsteke, Steve 249

Watanabe, Naoki 291 water 46–51

Waycott, Angus, Sado, Japan’s Island in Exile, 159

Wilson, Lucy and Tom 242

wine bars see bars in Tokyo wineries and vineyards

Hiroshima: Hiroshima Miyoshi 313

Hokkaidō 271–2, 312

Chuo Budoshu Chitose Winery 272, 306–8

Domaine Takahiko 272, 312

Hokkaidō Wine Company 264, 308–10

Nakazawa Vineyard 272, 312

Yamazaki Winery 272, 310–12

Iwate

Edel Wein 312

Kuzumaki Wine 312

Katsunuma 258, 260, 267

Katsunuma Winery 298

market statistics 354

winery numbers and production volumes 352

Miyazaki: Tsuno Wine 313

Nagano 267–9, 288, 290, 313

Domaine Sogga (Obusé) 294–6

Izutsu Vineyard 258, 259, 268, 313

Kido Winery 296–8

Manns Wine Komoro Winery 298–9

Rue de Vin 313

Shinshu Takayama (cooperative) 299–301

Villa d’Est Gardenfarm and Winery 301–2

Niigata 273, 290, 313

Iwanohawa Vineyard 313

Fermier 313

Ōita: Ajimu Budoshu Kobo 313

organic 294–6

Osaka-Fu

Katashimo Winery 313

Nakamura Wine Kobo 313

Shimane: Okuizumo Budoen 313

Shizuoka: Nakaizu Winery 313

Tochigi

Chichibu Wine 313

Coco Farm & Winery 312

Saitama 312

Toyama: Says Farm 313

Yamagata 270–71

Gassan Wine 312

Sakai Winery 312

Takahata Winery 303–4

Takeda Winery 305–6

Yamanashi 259, 262–3, 265–7, 313

Chateau Mercian 274–5

Diamond Shuzo 313

Grace Wine 276–8