John Hilliard: Not Black and White

Duncan WooldridgeIt is a relatively recent development that has permitted image-makers to embrace photographic abstraction, especially its extreme form, the monochrome. For many literalist advocates of ‘straight’ photographic representation, abstraction still seems antithetical: it is decried and diminished as a fad. And at the seemingly opposite pole, concrete and cameraless photographic approaches, with their love of the alchemy and stuff of photography, have been subjected to an equally overzealous enthusiasm that searches for the essence of the medium and regurgitates an etymological reading of photography as ‘drawing with light’. However reactionary, both positions nevertheless describe standard attitudes to photographic production and reception: concrete and cameraless photography privilege analogue materiality over the potential of new technology; the advocates of ‘straight’ imagery cling to equally nostalgic ideas of unmediated truth and simplicity in a culture of considerable complexity. Whilst appearing to be distinct, each attitude participates in, or demonstrates the force towards, what Vilém Flusser calls ‘the universe of technical images’, whether television, photography, or ultimately the web, those now ubiquitous surrounds of our everyday life. These practices produce complex or sophisticated-looking images to communicate simple messages, becoming participants in a ‘program’1 that perpetuates the consumption of cameras, the production of images (to test the camera and put it through its paces), and ultimately, the lingering

sense of obsolescence that leads once more back to consumption, production and so on. But such passive, uncritical pictures are counteracted by others more resistant to the disposable flow of successive images, more complex in their meanings and adopting visual strategies that may be direct but problematic, or requiring time. The work of British artist John Hilliard, and particularly his use of the monochrome, takes just such an approach.

Born in Lancaster in 1945 and trained at Saint Martins School of Art, London, Hilliard has for over 45 years developed a practice of photographic image production that resists interpretative simplicity and illusory transparency, and challenges the conventions of photographic image-making. Balanced between an interest in the mechanisms and limitations of the photograph, and its conventions of viewership, Hilliard has brought a rich and varied array of visual strategies to photography. This essay will attempt a reading of his extensive practice through its recurring call to abstraction, visual obstruction and monochromy. It will view his recourse to all-over, blanked out and occluded space – something that can be traced across his entire career – as a strategy inserting alternative pictorial logics into photography.

Such strategies align a medium often firmly entrenched in conventional representation with wider and more radical concerns and positions expressed in other media, and engage with a culture

of increasing technological and theoretical complexity in which forms of labour and even artistic production have moved progressively away from object production into propositions, concepts and language. David Joselit has suggested that contemporary art has its origins and subsequent ‘style’ in the approaches of Conceptualism,2 in which the proposition, document and logics of the readymade all dematerialise the art object by engaging with language, discourse and the urge towards communication. Hilliard, of course, is strongly aligned with conceptual practices of the 1960s and 1970s, and such contexts will necessarily inflect our readings of his photography. But I will also argue that his work with the recurring monochrome engages with other artistic approaches of the same period.3 Shifting from wall painting to blown-out (over-exposed) picture, to obstructed tableau, his intensive and rigorous abstraction, disruption and obstruction of the photograph’s illusionistic effects are demonstrations of photographic capabilities, and chart an early encounter of the medium with the full and rich history of abstraction.

Hilliard’s thoroughly iconic conceptual disassemblies of photographic objectivity are well known and documented, though his more recent and ongoing explorations are equally significant and have yet to receive similar consideration. A move into largescale, staged picture-making, begun in the late 1970s and early 1980s, demonstrated a concern for the large-format advertising and theatrical imagery of the period. It also marked a transition to considering alternatives to painting’s emphasis on tradition, rejuvenated by the hypertrophied Neo-expressionist painting that was emergent at that time. Hilliard’s interest in the earliest iterations of electronic photographic output, including the Scanachrome process, demonstrated a commitment to present technologies, which he has described as ‘less burdened by craft and history’.4 Work produced in the mid-1990s again moved towards new strategies and approaches, foregrounding the contexts of production, discourse and display that have also been prominent in Hilliard’s pre-eminent teaching in British art schools.5 Many works from this time depict scenes from, and make use of, art-school studios and spaces associated with practice, study, dialogue and sociability. With their obstructing central components made of studio backdrops, projector screens and free-standing walls, he displaces the image to the margins, leaving at the centre a blank and punctuating object. The late 1990s and 2000s have seen Hilliard addressing these spaces through a renewed play with pictorial orientation and movement. Pivoting and rotating, he has produced multiple-exposure works that address several objects from a single position, and single objects from multiple positions. Overlaid, they produce images of spatial complexity that describe the agency of the photographer in making decisions.

photographers attempt to conceal in the process of production, a contingency that is squeezed out. By pulling the film off the shelf and using it in its most straightforward mass-produced form, Hilliard echoes Palermo’s and Richter’s address to some of the properties of a capitalist realism, and demonstrates cultural and pictorial abstraction through photography. In fact, in two remarkable but rarely seen works, Hilliard constructs his own colour charts of variance and choice: Grey Scale (1972) and Colour Patches (And Seven Representations – Negative Film Stock) (1972; p.63) are sly and comic adoptions of the amateur’s obsession with technical comparison, utilised as a rejoinder to those accusations that photography is fundamentally representational.

The Image – Refusal and Obstruction

When the writer and curator John Szarkowski stated in his 1966 publication The Photographer’s Eye that photographs, unlike images in other artistic media, were ‘taken and not made’, he may well have intended to argue for the unique properties of the photographic image. Indeed, Szarkowski’s ‘taken’ photograph demonstrated the contingency of the image, and related it once more to the world. If Abstract Expressionist painting had refused to engage with the cultural and political events of the time – and was robustly criticised for it – hard-edge abstraction, and many of its European, systemsbased counterparts, embraced contingency and their conditions of production and reception, as we have seen in Benjamin Buchloh’s definition of diagrammatic abstraction. Marcel Duchamp’s return to prominence as a result of his 1963 Pasadena Museum of Art retrospective reintroduced values of selection, extraction, representation and nominalism as strategies for artists to adopt. It might appear curious, then, that those same terms, selection and extraction, are introduced as properties that distinguish the photographic image from other arts. Whilst Szarkowski’s call for a distinct category of photographic practice might appear ineffective in such a light, what is at stake should not be Szarkowski’s intention to distance photography from the other arts, but photography’s potential to be contemporary and relevant, which is demonstrated when it chooses, removes, abstracts and makes strange.

In each and every version of its manifestation, a photograph is always an extraction, an abstraction of sorts. It selects, lifts, removes and transfers the image to the dark chamber of the camera, to be received by another surface, remote from the object photographed. It resurfaces on the negative or sensor, in the darkroom, and onto the

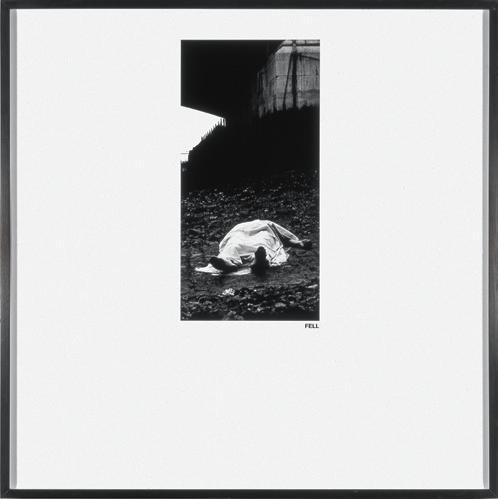

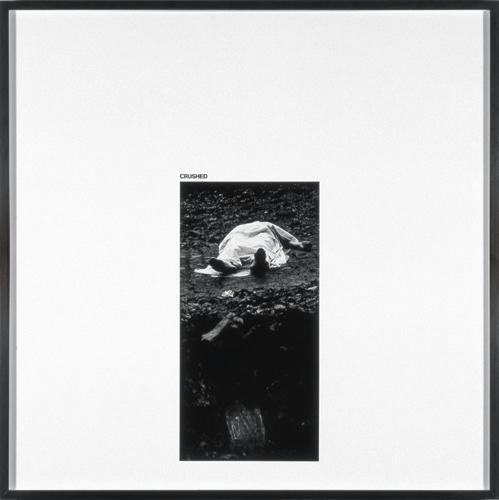

Cause Of Death? (3) 1974

Black-and-white photographs and Letraset

on museum board, framed

Four panels

Each: 52 × 52 cm | 20½ × 20½ in

made visible. Considering the photograph and its staging, he draws upon a renewed strategy of obstructing the image. Main Feature (1995) presents presentation. The rectangular light of the projector is beamed onto a curtain, isolating a section of fabric towards which one’s eyes are drawn. Expectantly waiting for a film that is about to begin, the curtains are about to be withdrawn. And yet anticipation and suspense are presented to us instead, permanently. It is a film we will not see, cannot see, the photograph’s stasis prohibiting a moment of cinematic unfolding. Such strategies are reminiscent of theatrical staging’s prolonged to antagonistic effect. In June of 1967, at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, the French group bmpt, comprising Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier and Niele Toroni, hung their paintings above the stage in the lecture theatre of the museum. Viewers entered the arena, encountering the paintings, which they took to be decoration, as they sat down and awaited the start of an event, discussion, performance or happening. Allowing the theatre to fill, and grow restless, bmpt did not begin any such performance: after an hour they simply circulated to the agitated audience a notice stating ‘you have seen what you need to see’. In attending to the state of inattentive, distracted viewing that prefigures the main feature, the artists remind us of the theatricality of events as they are presented to us, their staging, formality and decor. Main Feature slowly draws our eyes to the blue velour fabric and the stylised usher, who shines a light onto the floor. Such ceremonies provide drama, but are usually just a prelude conditioning that which is about to be seen. Hilliard teases the viewer’s sense of expectation, presenting the moment before an event unfolds, drawing our attention instead to the conditions of cinematic presentability. Presenting presentability would return in Hilliard’s work (in Exhibition (1), 2001; p.91), but for now, we will consider his address to the studio.

For Hilliard, the studio is a pivotal space. In his work of the 1990s, this site might be considered in at least four distinct ways. Firstly, in etymological terms, the studio is a place of study, originating in the Latin, studium: it is the site of artistic education and discussion. Secondly, the studio is the site of artistic production, an atelier in which the work is primed before going out into the world. If the work is not finished, it does not exit the studio. Honoré de Balzac’s Unknown Masterpiece (1831) tells the story of just such a painting, produced by the fictional artist Frenhofer, whose virtuosity is met by a reluctance to be satisfied with the work and call it complete. The painting reveals itself not to be figurative (as was the tradition of the time), but a nebulous abstraction, a representation pushed beyond all recognition.18 Thirdly, the studio as a site of designated activity is not just an artist’s studio, but a site of dance (see Fit, 2010) or of

photography. Although they could be interchangeable with the artist’s studio, such spaces are often sited in academic and commercial environments, and come with specific requirements and tools that are not necessarily present in the artist’s working space. Finally, the studio is a place of looking and waiting, just prior to the work’s departure into the world of exhibitions. Here we return to the Latin studium again, that term infamously adopted by semioticians and applied by Roland Barthes to the photograph to describe the viewer’s comprehension of the image. Such notions of the studio transform this space from the artist’s workshop to a site of complexity, variation and discourse. Hilliard has returned frequently to these possible uses of spaces in order to reveal the more complex labours of artistic practice that the rapidity of photography can often disguise. We shall see that he does so by depicting those sites, but at the same time, concealing them from us.

Screening (1998; p.75) and Plain Cover (3) (1996; p.68) record processes of research and study. In both works, the exact object of study is blocked. What is apparent to us is the carrying out of the activity, and our temptation to read menace into an event that we cannot fully perceive. Continuing our temptation towards narrative, these early images of research are fraught with events that are squeezed out by Hilliard’s strategy of de-centring the pictorial incident to the margins. As we saw in White Expanse and Black Depths, what takes place at the margins requires a heightened awareness, free from the givens of prescribed information and assumption. Off Screen (1) (1999; p.49) records a seminar or discussion. The object of discussion is again blocked – what is made apparent to us is only that discourse is taking place, behind a fold-down screen. In its stasis, the photograph excludes us from this discussion, its live, durational experience captured from afar. A screen is used to preserve privacy or modesty, as in One Night (1999), which depicts an improvised sheet curtain to divide the room in an echo of Frank Capra’s film It Happened One Night (1934). Whilst modesty conceals the initial activities of the artist, in the seminar or the critique, what artists must do is expose themselves: they must make visible their interests, and discuss how and to some extent why they have chosen to approach their subject or media in a specific manner. Off Screen might describe such a moment, just as it might equally describe the moment of one’s exposure to another’s film, image or idea, played in front of a receptive audience. Untitled Interior (15.7.00 And 18.7.00) (2000; p.37) represents a newly clean working space, cleared from a cold and graffitied interior. The whited out, cleaned-up space is in effect laid onto the graffitied space (produced by the artist just a couple of days before). By replacing the used or defaced space with a renovated area of the studio, Hilliard places pictorial incident at the edges, as in his

other monochromes. In Untitled Interior he practises another of his distinct approaches to the photograph, literally affixing one version of the photograph onto another, a blocking that is the very erasure of the image below it. It is not difficult to see how this represents the starting over, whether through the occupation of a new space or the making of a new work, that is the continuous cycle of artistic production.

Hilliard continues his puncturing of the photograph’s central space in Backdrop and Exhibition (1) (both 2001). Backdrop shows a workshop on studio photography. A technician is visible in the corner, looking through the viewfinder to make the exposure; an audience, of viewers and perhaps participants, watch as the photograph is taken. We might imagine an embarrassed model being subjected to the lens of the camera and the eyes of the crowd; we might equally imagine an image or an object being documented, a work of art being reproduced photographically. The grey backdrop hides part of the performance, registering only its witnesses. Exhibition (1), however, projects a different reading. Moving away from the studio and into the space of display, Hilliard depicts the moment of looking. A Thomas Struth-like ‘Museum Photograph’, without its object of attention and value, Hilliard’s work finds in the central freestanding white wall of the gallery another object of punctuation. The gallery wall, and its pristine, spot-lit surface draws our attention until we become aware of the hustle and bustle of the gallery itself. Its offices in the spaces on either side are visible and tease with their partial visibility. In 1974, at the Claire Copley Gallery, Los Angeles – when Hilliard first began to push his images to the edge of the frame in Black Depths and White Expanse – Michael Asher removed a dividing wall so as to reveal the commercial transactions of the gallery space (p.26). Having absorbed the lessons of Asher’s institutional critique, galleries operate within a notion of controlled transparency – sufficient to describe busy activity and trade, and opaque enough to conceal the object of such labour. It seems no coincidence that Hilliard’s image is concerned with the perceptible and yet inaccessible spaces of the gallery. It is as if Asher’s wall has landed straight in the centre of the photograph. And yet at the same time, it is true that artists now trade in largely immaterial commodities –ideas. Perhaps Hilliard points to the changing emphasis on visibility and tangibility in practice, and makes possible the viewing of the immaterial artwork in showing us empty space. After all, where are the artworks in Hilliard’s sites of artistic production?

In Hilliard’s hard-edged monochromes, pictorial detail is pushed to the edges, and at the centre is a punctuation or erasure that disrupts simple viewership. His most recent completed body of work continues to revolve around the singular blank space, though here we witness a partial return of the object. Extending the strategies begun

in his earliest work – using multiple images and their connotations –Hilliard has begun to expand upon the layered photographic image begun in Untitled Interior. The compression of time and space in the photograph is synthesised in a series of works pivoting around objects and spaces. 1, 2, 3 (2004; p.33) demonstrates most clearly the construction of overlaid exposures, as Hilliard rotates around a triangular hat resting on a sculpted head. Each exposure depicts the object from the same perspective, and aligns, with some misregistration, the three planes, creating a sparse and clean white field in the centre of the image. All that resides here is an informative overlaying of the numbers 1, 2 and 3, describing the sides of the object as the camera swings around the room. On each of the three walls represented within the image are the monochromatic fields of cyan, yellow and magenta, the three colours of the darkroom and cmyk printing processes. Returning us to the very beginning of Hilliard’s recurring monochromes, 1, 2, 3 is both wall-painting and image simultaneously.

In Hilliard’s multiple exposures, what can be traced is a planning and schema for the photograph that allows us to chart the decisions of the photographer. In the present context of photography, where a culture has developed that seems to accept, even consider as voguish, the abstract nature of photography, George Baker has described how such abstractions need to continue to perform a role, and not merely withdraw into aesthetic formalism. For him, the present –data transmission, the removal of material currency, and paperless books – is the realisation of a culture of abstraction. Baker calls upon photography to represent that very abstractedness: that is to say, to make abstraction relevant to and contingent upon the abstractions we experience in day-to-day life, to again make them diagrammatic. He urges us to straddle a line between what can and cannot be seen, and to return to a project of revealing the seemingly transparent architectures (physical and virtual) that are present to us. Hilliard’s Division Of Labour (2004; p.87) seems to break up and yet merge the discrete disciplines of a studio practice and demystify the process of art-making. Circling the central object are the tools of different practices, which, whether medium-specific or interdisciplinary, coalesce as an artwork, representing choices that the artist must make. Right And Wrong (2010; p.47) along with Balance Of Power (3) (2010; p.77), are unusual for being two of a small series of works that can be hung with different orientations. Right And Wrong pivots around two collections of the artist’s body of work, prompting us to consider ideas of choice – hopefully unpicking the false dichotomy of good and bad that is implied in the title of the work, just as we might unpick the unnecessary dichotomy between representation and abstraction.

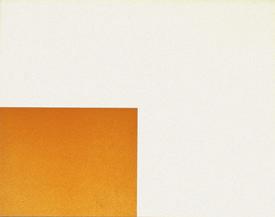

The Yellow Of An Enamelled Coffee Pot 1973

C-type photographs on card

20 panels

Each: 30 × 38 cm | 11¾ × 15 in

White Expanse 1974

Black-and-white photographs and Letraset on museum board, framed

Two panels

Each: 80 × 80 cm | 31½ × 31½ in

The Pleasure of Erasure

John Hilliard March 1996Their picturesque vistas screened by a hail of unruly streaks and blotches, the battered, splattered and beaten canvases of Constable’s large, late oil sketches from the 1830s (A River Scene, with Farmhouse Near the Water’s Edge; Cottage at East Bergholt) crackle with an energy far less ardently exhibited in their more pacific, more finished counterparts. In a series of paintings of lions and tourists (1975), Gerhard Richter chooses to obscure those very objects from our hopelessly searching gaze, both vexing and intriguing us, the anarchy of a muddied camouflage of pigment more challenging, finally, than the soft-focus, photo-real perfection of other works from within his extensive oeuvre of shifting styles. And Rauschenberg’s Erased De Kooning Drawing (1953) seems more austerely purged even than his own white monochromes, yet remains as spikily, angrily and indelibly inscribed into the distressed paper as any other work styled with the signature of the Dutch-American donor. In all these cases, an unimpeded gaze is not merely refused but redirected to another site – that of the obstruction itself. The attack on the image is also an endorsement of the instrument of destruction (the very medium or tool normally employed to fashion that image now turned against it, boldly asserting instead its own presence, yet in so doing re-inflecting the original subject from a re-positioned perspective). In music, Jimi Hendrix’s feedback is both raucous cacophony and fluent articulation of sound, his inspired rendering

Oil on canvas

190 × 230 cm | 74¾ × 90½ in

Erased De Kooning Drawing 1953

Traces of drawing media on paper with label and gilded frame

64.1 × 55.3 cm | 25¼ × 21¾ in

of the Star-Spangled Banner (1969) ambivalently abusive and celebratory. In writing, William Burroughs’s cut-up texts are destructive yet productive, Doctor Benway’s antics in The Naked Lunch (1959) driven to even greater extremes by the bizarre verbal juxtapositions conjured out of this chance technique. In cinema, the chain of nuclear bursts that ends Stanley Kubrick’s Doctor Strangelove (1964) is both awful and awesome, annihilating and exhilerating, each at its blinding vertex cancelling the film and everything else, yet impacting upon us in an explosion of aesthetic pleasure.

If the cathartic excitement of controlled violence constitutes one dimension of the spectator’s perverse fascination for such creative acts, obliteration is also enjoyed as a purgative, annihilation as a cleansing, a purification. The image may be razed or erased to attain such purity, but it may equally be screened, obstructed or blockaded in a defiant act of refusal, obscured by a white noise of impenetrability or a blank wall of silence.

Such draining, reducing and veiling recurrently features throughout my own previous work, the evident symptom of an incurable discomfort with that very means that is also the medium of choice. Light both illuminates and extinguishes the instrument recording the timed increments in Sixty Seconds Of Light (1970; pp.40–41), the bleached over-exposure of the final image being increased to its zenith in the vacant squares of White Expanse (1974; pp.78–79) or reduced to its nadir in Black Depths (1974; pp.80–81) – blanks signifying nothing without the dubious assistance of a peripheral caption. And so on – excesses of contrast and exposure, fogs of unfocused uncertainty, mobility blurred into oblivion, all in turn collude in a rebuttal of the aspiring transparency of photography.

This ostensive transparence, cuing the uncritical acceptance of photography’s ‘window’ into an unmediated reality, is observable as a present convenience within contemporary art, feeding a straightforward quick-fix documentary need, or satisfying the quest for a ‘new objectivity’, in amnesiac disregard for the deconstructive attentions of the 1970s. Perhaps in reaction to such re-grouping, and doubtless as confirmation of a personal reluctance to concede an easily secured image, the litany of obstructions continues.

These purgative measures can also be seen as a corrective to a perceived deficiency in a body of my own work from the 1990s – triple exposures from the same viewpoint, each successive shot differentiated merely by selective re-focusing. In spite of ensuing layers of unsharpness, these pieces open up the appearance of a deep space whose imaginary recesses give encouragement to their narrative and pictorial tendencies. The apogee of this practice is registered by the aptly titled Wrong (1992; p.94), whose overlays of

The Less Said the Better

John Hilliard 1999/2000The most uncompromising, the most apposite written exposition on this theme should, by strict definition, be a succession of perfectly blank pages. Equally, its most complete counterpart from within the realm of the art object should be replete with omission to the point of virtual disappearance. Clearly, though, a page is beginning to be filled, just as that ideally invisible work of art persists in being made. The shortfall, then, between imagined ideal and actual realisation, the need after all to speak of or present the very subject of notspeaking or not-presenting, provides a space for production and an excuse for utterance.

Setting aside for the moment the specific, perverse and possibly scopophobic phenomenon of image-erasure as a subject for the artist, ‘saying less’ as a beneficial condition may emerge as a consideration at two stages: the primary process of creation and the secondary process of dissemination. In the first instance, saying less may mean saying less to oneself. This by no means suggests the abandonment of conscious, nameable, considered prescriptions that guide the mechanics of conception and production (in favour of a wholly unconscious spontaneity). Rather, it means making an admission – that however analytical and rational one’s inclination, the unheralded influence of the subjective or the accidental may in fact add a certain je ne sais quoi that turns out to be crucial in the finished work, and there are times when it may be wise to curb an inquisitorial

bent, and allow such intrusions some licence. In the second instance, saying less may mean saying less to the percipient of that work.

Marshall McLuhan, in Understanding Media (1964), refers to the ‘act of completion’ – the spectator’s struggle to grasp a work of art, the profound understanding that devolves from a necessary participation in making that struggle, and the ensuing satisfaction which is the result of that participatory act. In order to allow the spectator this experience, to permit them to contribute, the artist needs to leave some space, giving them room to enter and room to manoeuvre without being over-instructed.

Nevertheless, there is a subsidiary voice that the artist may be tempted to deploy as a persuasive tactic to secure influence. It is the voice of explanation: the articulation of a theory or argument that surrounds and contextualises the work itself, legitimising it and making it comprehensible. One source for such commentary might be the wealth of contemporary theoretical writing on the subject of representation (from a linguistic, sociological, philosophical and psychoanalytical position), which has been particularly relevant for the visual arts, not least because visual material (painting, photography, film, architecture) is often the subject of analysis and the source of examples. The temptation, though, is not in the actual resort to such theory or indeed to any complementary text, but in the attempt to shore up one’s work with it in order to stave off a collapse.

After Words

John Hilliard February 2013Pre-scription

While still at art school, making sculpture, I often commenced from a fully fledged vision, a mental image of a completed work, given preliminary substance through a rough sketch or diagram (to preserve it from forgetfulness and to serve as a basic prescription for its subsequent materialisation). Such drafting is a commonplace within the creative process of artists and designers (Renzo Piano’s ‘Shard’ building in London reputedly originated as a sketch on the back of a menu in a Berlin restaurant), although perhaps not so readily associated with photography. Even so, there are instances from within the diversity of that medium, as when the art director of an advertising campaign produces a visual guide for a stills photographer. My own use of drawing in relation to photography (a direct continuation of its original deployment for sculptural purposes) may be comparable to that example, although doubtless less skilled. In Aspects No.16 (1981, Newcastle-upon-Tyne) I published an article called ‘Drawings (In Anticipation) Of Photographs’, describing a practice in which photographs are pre-visualised through drawing, in contradistinction to a more common order of procedure where artists use photographs as a reference source from which to produce drawings and paintings (a convention that I also eventually found the need to employ, albeit for unorthodox ends).

Since the late-1960s, this relationship between a prescriptive drawing and a completed image has characterised all my photographic work. However, commencing in 2002, in a series of pieces comprising multiple exposures of the same subject from different points of view (so that distinct profiles are aligned or misaligned within a composite whole), drawing is deeply embedded as an underlying structure. Specifically, the analogy of drawing something and then re-drawing it, again and again, to ‘get it right’, is central to the thinking behind this particular project.

Post-scription

Having previously drawn a rough likeness of my own photographs before ever commencing on their production, I now decided first to re-draw the finished images and then to make photographic prints from those drawings, establishing a repetitive chain of transcription from drawing to photograph to drawing to photograph. In other words, the end product would now be a photograph of a drawing of a photograph from a drawing. One objective in doing this was to direct attention to drawing as a core component in the conception and execution of these particular works, and to give emphasis to the

Credits

Bibliographic References

‘The Pleasure of Erasure’, first published in John Hilliard: Works 1990–96, Kunst.Halle. Krems, Austria and ar / ge Kunst Bolzano, Italy, 1997.

‘The Less Said the Better’, first published in The Less Said the Better, Städtische Galerie, Erlangen and Verlag Das Wunderhorn, Heidelberg, Germany, 2003.

Collection credits

Courtesy the artist, London: pp.2–9, 14 (bottom), 20 (top), 23 (top), 24, 31, 37, 43–47, 52–63, 68–71, 75–77, 83–87, 91, 94, 95 (top), 96–101, 105, 107–12, cover

British Council Collection, London: pp.11, 30

Tate Collection, London: pp.12, 39–41

Private collection: pp.17 (top), 78–79

Private collection, Italy: pp.17 (bottom), 80–81

Collection Angelo Baldassarre, Bari: p.19

dz bank Art Collection, Frankfurt: pp.21 (bottom), 73

coff – Colección Ordóñez-Falcón de Fotografía, tea – Tenerife Espacio de las Artes: pp.22 (top), 67

Municipal Collection Erlangen: pp. 49

Studio d’Arte Contemporanea Dabbeni, Lugano: pp.33, 65

Galerie Raum mit Licht, Vienna: pp.34, 106 Colección Helga de Alvear, Madrid/Cáceres, España: p.51

Private collection, Switzerland: p.89

The Rolla Collection, Switzerland: p.95 (bottom)

museion Foundation. Museum of modern and contemporary art Bolzano: p.102

Works by other artists

Lawrence Weiner (American, b.1942).

Photo courtesy the artist & Moved Pictures Archive, nyc , and Harald Szeemann Archive, Switzerland. © lawrence weiner , ars, ny and dacs, London 2014. Collection: Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Shunk-Kender: p.14 (top)

Jan Dibbets (Dutch, b.1941). © ars, ny and dacs, London 2014. Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands. Photo: Peter Cox, Eindhoven, The Netherlands: p.16

Daniel Buren (French, b.1938). © db - adagp Paris and dacs, London 2014: p.22 (bottom) © Everett/ rex : p.23 (bottom)

Michael Asher (American, 1943–2012).

Photograph courtesy Claire Copley. Photo: Gary Krueger: p.26 (top)

Robert Ryman (American, b.1930). Medway, 1968. Installation at Dia:Beacon, Beacon, ny. Dia Art Foundation. © 2014 Robert Ryman/ dacs, London. Photo: Bill Jacobson: p.26 (bottom)

John Constable (British, 1776–1837). Courtesy National Museums Liverpool, Lady Lever Art Gallery: p.92

Gerhard Richter (German, b.1932). © Gerhard Richter 2014: p.93 (top)

Robert Rauschenberg (American, 1925–2008). © Estate of Robert Rauschenberg. dacs, London/ vaga , New York 2014. Collection sfmoma , purchase through a gift of Phyllis Wattis. Photo: Ben Blackwell: p.93 (bottom)

Great care has been taken to identify all copyright holders correctly. In cases of errors or omissions please contact the publisher so that we can make corrections in future editions.