Impressionist Painters

chAPter 7 William Blair Bruce (1859–1906) ■ 267

chAPter 8 Maurice Galbraith Cullen (1866–1934) ■ 297

chAPter 9 James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924) ■ 333

chAPter 10 William Brymner (1855–1925) ■ 379

chAPter 11 Peleg Franklin Brownell (1857–1946) ■ 399

chAPter 12 Laura Muntz Lyall (1860–1930) ■ 419

chAPter 13 Henri Beau (1863–1949) ■ 439

chAPter 1 4 Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (1869–1937) ■ 459

chAPter 15 Helen Galloway McNicoll (1879–1915) ■ 491

chAPter 16 Arthur-Dominique Rozaire (1879–1922) ■ 511

chAPter 17 William Henry Clapp (1879–1954) ■ 527

chAPter 18 Clarence-Alphonse Gagnon (1881–1942) ■ 555

chAPter 19 John Young Johnstone (1887–1930) ■ 601

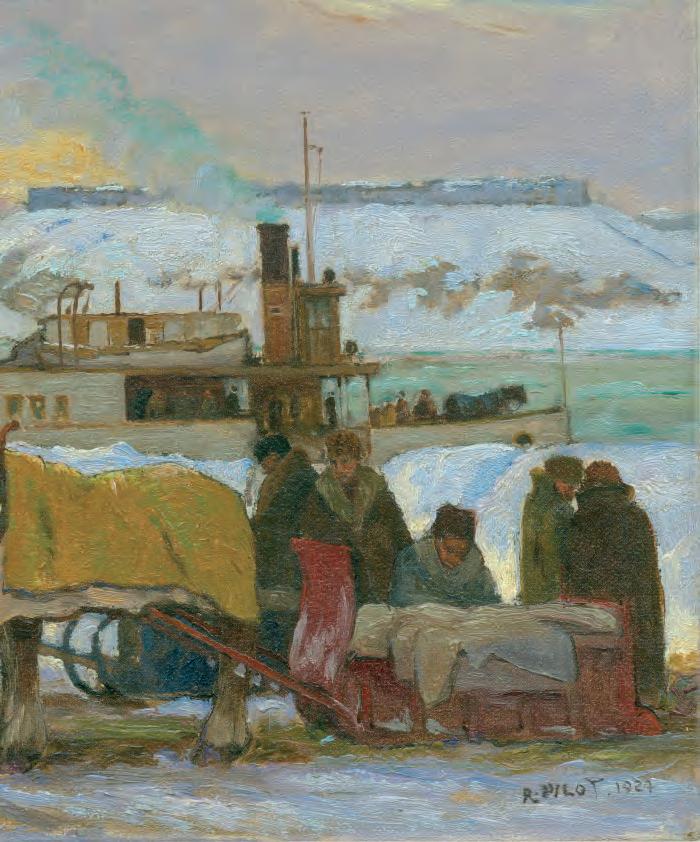

chAPter 20 Robert Wakeham Pilot (1898–1967) ■ 619

chAPter 2 1 Other Canadian Artists Influenced by Impressionism ■ 641

ePIlogue ■ 694

APPendIces ■ 697

A Br ymner’s Speech on Impressionism, April 13, 1897 ■ 698

B Addresses for Canadian Artists in Europe, 1878–1924 ■ 706

c Canadian Impressionist Painters Exhibiting in the Paris Salons, 1880–1922 ■ 712

d Loans and Sales to Canada from Durand-Ruel, 1892–1923 ■ 718

notes ■ 721

selected BIBlIogrAPhy ■ 735

LiSt Of iLLuStRAtiONS ■ 744

Index ■ 764

Foreword

At its origin, each artistic movement is determined by the innovations its founders bring to bear on tradition, but historians and theorists commenting on it tend at times to tread their own path and ser ve their own agendas. The significance of French Impressionism is firmly established, and it is unequivocally recognized that modern art – the art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – sprang from it. But such painters as Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Degas, Renoir, Sisley, and Morisot to a great extent managed to maintain their autonomy, and their revolutionary ideals were many and diverse. Their individual approaches to nature and their technical and interpretational solutions to pictorial and graphic problems were breakthroughs that gave their creations their dynamic thrust and inspired succeeding generations of painters and draftsmen in many countries.

Impressionism in Canada: A Journey of Rediscovery by A.K. Prakash contains a remarkable panoramic story of Impressionism from its inception in France to its importation into the United States and Canada. In it he characterizes the impact of the French Impressionists on the arts of North America. It is essentially a missing chapter from the world movement of Impressionism as a whole. In this book, he makes a fundamental contribution to art history by acknowledging the Canadian artists who gleaned much from the French but, in their improvisations, managed to transmute what they learned into an art reflecting the aesthetic concerns of their compatriots and the times in which they lived and worked. For this accomplishment, we congratulate him heartily.

Guy Wildenstein

The Wildenstein Institute, Paris

fAC

■ James Wilson Morrice, The Pink House, Montreal, c. 1905–8, oil on canvas, 59.7 x 48.3 cm, private collection.

Guy Wildenstein

a cknowledgments

Over the past thirty-five years I have studied the work of Canadian Impressionists and maintained an extensive archive on them. Had I limited my survey of Impressionism only to Canada, my challenge in writing this book would have been much simpler. Canadian Impressionism is, however, one national variation in the wider world movement of Impressionism – the most significant development in Western art since the Renaissance. It is therefore necessary to review the history of Impressionism in order to examine Canadian Impressionism. A survey following Impressionism from its birth in France to its evolution in North America provides a more informed basis from which to assess the contribution of Canadian Impressionists.

The research for this book has been carried out in several countries – France, England, Sweden, the Netherlands, the United States, and Canada. It has involved the participation of a number of distinguished scholars, curators, and art dealers as well as a review of archival sources in museums and galleries. I am indebted to all those who assisted me with their scholarship, expertise, and advice. Their encouragement helped me to expand my research beyond the bare facts necessary to present a full narrative of the story, one hitherto untold.

First and foremost, I want to thank four acclaimed scholars of Impressionism:

GUY WILDENSTEIN of the renowned Wildenstein Institute, Paris and New York, author of countless authoritative publications on Impressionism, who read the entire manuscript and wrote the Foreword to this volume.

FLAVIE DURAND-RUEL of the Durand-Ruel Archives, Paris, whose generous support in discovering critical information previously unknown has enabled me to fill in some gaps in the history of Impressionism in North America.

DR. WILLIAM H. GERDTS, Chairman and Professor Emeritus, Graduate School of Fine Art, City University of New York, who also read the text and wrote the Introduction. His essay provides an insightful survey of the comparative history of Impressionism as it emerged in the United States and Canada.

DR. CHARLES F. STUCKEY, former Curator, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, who also reviewed the manuscript and provided invaluable guidance on both facts and interpretation.

Facing page

Plate a.1 ■ Laura Muntz Lyall, A Florentine [detail], 1913, oil on canvas, 92.7 x 67.3 cm, private collection.

Fig. 1.5 ■ A lithograph by Honoré Daumier, best known for his political and satirical cartoons, shows an artist being comforted over the position of his works – hung well above eye level – at the 1859 Paris Salon. The text that appeared with the cartoon, published in the April 20, 1859, issue of Le Charivari magazine, reads, “You should be happy, my dear friend. Your little pictures have been hung above Meissonier [a celebrated artist in Second Empire France].”

exhibition: the Louvre, the École des Beaux-Arts, and the Salon de Paris. The opening ceremony for the Salon every year in the spring was a grand public occasion, and exhibiting there was the key to success, especially for the few artists who won medals or received honourable mentions, and for anyone who hoped to be a professional artist.

* Once the Salon jurors reached a consensus, they marked the backs of the frames with either an “A” (admis) or an “R” (refusé). The accepted paintings were then given a one, two, or three category, meaning that the first group would be hung at eye level, the second group in the line above, and the third group two lines above. Those without a number could be hung anywhere else in the room. In April 1870 the Paris-Journal published a letter from Degas which proposed better installation options at the Salon.

Writers such as Charles Baudelaire and Émile Zola often reviewed the exhibitions, and by these means the Salon not only established reputations but provided the market for purchases by the state, by major art dealers such as Goupil et Cie, and by wealthy private collectors.13 Inclusion or exclusion from the Salon could make or break an artist’s career, and the tensions surrounding acceptance or rejection by the jury affected painters and the interested public alike. “Yesterday was the last day of sending in for the Salon,” Canadian artist Robert Harris wrote home in 1882, “and the scene was very amusing. A great crowd had collected, trying to get glimpses of

the pictures as they went in. They hooted the bad ones and cheered the good ones and made things lively in general. There was as much excitement as there used to be around the hustings at one of our elections!”14 Even for the artists fortunate enough to be selected, much depended on the position their paintings occupied among the 2,500 or more pieces arranged on the crowded gallery walls: if a work was “skyed” near the ceiling or placed near the floor, it got little notice, but if it was “on the line,” at eye level, it might be reviewed by the critics or even attract a buyer (fig. 1.5).* Astute artists did whatever they could to make their works stand out – by painting large and imposing canvases, choosing subjects that appealed to viewers’ emotions, selecting distinctive frames, and even signing their names in bold letters.

After the mass rejection in 1863, the feud between the two opposing sides could no longer be ignored, and a groundswell of discontent erupted among the two thousand or more artists who lived in Paris against

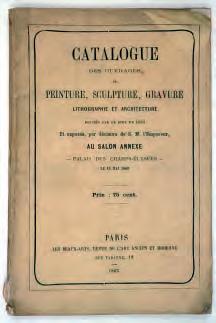

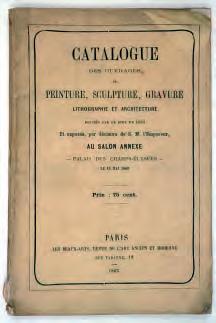

the authoritarian selection process imposed by the Salon. Napoleon III personally intervened and established an alternative exhibition space, known unofficially as the Salon des Refusés – the exhibition of the rejects. It was up to the people, he stated, to “judge the jury,” to decide on the best paintings of the year. The exhibition opened on May 15 and was a success – in the sense of providing an exhibition space for the artists and attracting an audience, even though many came only to mock the “bad” art. A hastily produced catalogue listed 781 works by many different artists, including Manet, Whistler, and Pissarro (fig. 1.6), and the exhibition launched Manet’s career as the leader of the avant-garde. In the following few years a determined opposition to the dictatorship of the Salon became a major force in bringing the rebels in the Impressionist fellowship together.

This defiant exhibition is an important milestone in the development of modern art in all its variety –Impressionism first, then Post-Impressionism, Fauvism,

Symbolism, and the myriad movements that followed as the century drew to a close. As painters increasingly drew their inspiration from the people and the scenes they saw around them, they all became flâneurs in a way – the strolling observers so extolled by Baudelaire, who, when they encountered individuals in cafés and public squares, at racetracks or theatres, on beaches and quais, quietly captured their attitude, clothing, and gestures, preserving them in sketches for posterity (plate 1.14). Zola expressed the feeling well when he said, “I am at ease in our generation.”15

Then, suddenly in 1870, the dream ended. Despite Napoleon III’s efforts, the economy lagged behind the industrial development in England and Prussia, though the French continued to have enormous confidence in their military prowess. Finally the emperor lost patience with his neighbour to the northeast and, unwisely, declared war on Prussia – now led by the efficient Otto von Bismarck who, as the “Iron Chancellor,” would go on to create a unified Germany after a series

opinion and the turning tides of

The refusés were heavily criticized in the press, but the attention the exhibition drew was an important step toward legitimizing the emerging avant-garde painters. Foremost among them was Manet, who exhibited three paintings, including his famously controversial Luncheon on the Grass, originally titled The Bath.

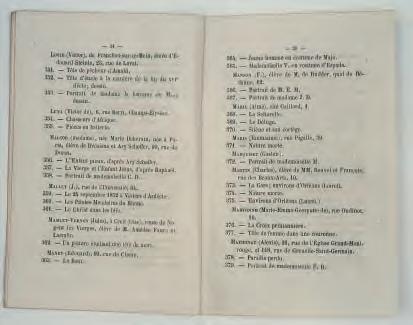

Fig. 1.6 ■ The catalogue of the Salon des Refusés exhibition of 1863. Although the emperor’s tastes were traditional, he was also sensitive to public

the art market.

above Fig. 2.2 ■ An 1857 engraving depicts the scene of the official Salon of painting and sculpture, held in the main gallery of the Palais de l’Industrie, a vast exhibition hall erected in Paris for the Exposition Universelle of 1855. Facing page Fig. 2.1 ■ The studio of Nadar at 35, boulevard des Capucines, where the first Impressionist group show was held in 1874.

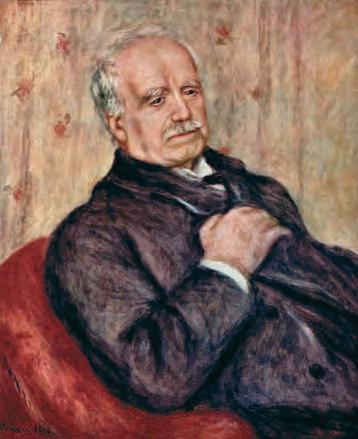

occupied. Durand-Ruel held the second Impressionist exhibition, of 1876, in his gallery, where, to promote individual artists, he gave each painter his own space on the walls. To encourage less confident collectors, he borrowed works he had already sold to clients and displayed them alongside the paintings that were for sale. When works by his artists went to auction at the state-sponsored Hôtel Drouot, he bid high to keep the prices elevated.

But Durand-Ruel was far more than a dealer to the Impressionists – he believed in them as artists (plate 2.17; fig. 2.11). When they initially experienced lean times, he gave them stipends in return for liens on their paintings, and, over several decades, purchased more than twelve thousand of their works. In the early 1880s, on the verge of bankruptcy himself, he had to refuse their requests, but as their reputations grew, his early trust and enthusiasm paid off handsomely for him. “My craziness has become wisdom,” he reflected late in life; “if I had died at sixty years old, I would have died crippled in debt, insolvent amongst undiscovered treasures.”16

One of Durand-Ruel’s rivals in promoting the Impressionists in Paris was the flamboyant Georges Petit, who exhibited works by Monet, Renoir, and Sisley after 1882 in a series of successful shows, initially called the Expositions internationales de peinture (fig. 2.12). He had been in business for several years but in 1881 opened the Galerie Georges Petit in a large space suited to exhibitions at 12, rue Godotde-Mauroy; later he moved it to even more opulent marble and red-velvet quarters at 8, rue de Sèze, in the centre of Paris near the Opéra. There he authenticated works of art, organized a variety of exhibitions with high-quality catalogues, and dispensed advice to his growing list of clients. Best known for bringing France’s premier sculptor, Auguste Rodin, to prominence, Georges Petit’s gallery remained in operation after his death until 1933, under the direction of the art dealers Bernheim-Jeune & Cie. Another Paris art dealer, Galerie Goupil, also organized one-man shows for Monet, Degas, and Pissarro in 1888 and 1889,

above Plate 2.17 ■ PierreAuguste Renoir, Paul Durand-Ruel, 1910, oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm, private collection.

Facing page Fig. 2.11 ■ DurandRuel was more than a dealer to the Impressionist painters: he was their friend and supporter. Here, members of DurandRuel’s family, including his son Georges, pose with Monet in the garden of the painter’s house at Giverny in 1900.

Chapter 3

And what a scene it was! Artists from all over Europe as well as distant countries such as Japan and Australia were flocking to Paris, hoping to study in one of the many educational institutions in the city. The best-known school was the old and established École des Beaux-Arts, on the Left Bank across the Seine from the Louvre, but it was difficult to obtain admission there (see Appendix B, figs. AB.10 and 11). The entrance examinations were rigorous, and applicants were required to produce recommendations from reputed teachers. Once an individual was accepted, however, the tuition was free. Instructors offered an Academic program designed to train students to construct large, heroic images, with particular focus on the human body. Students had therefore to master draftsmanship – first copying prints based on classical sculptures, then drawing from casts of those same sculptures, and finally drawing from live models, using line, contour, and shading to capture the pose. Basic instruction in art history and classical theory such as perspective was also on offer. Only in 1864, the year after the Salon des Refusés, was painting finally added to the curriculum, and thereafter the best students were encouraged to submit their works for possible exhibition at the official Salon, and perhaps to other exhibitions as well.

The faculty were all recognized artists in the Academic tradition – Academicism – including

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, and Léon Bonnat. The only language spoken was French, and although foreign students were not encouraged to apply, a few managed to join this elite group. No women were admitted until 1897: in this formal environment, it was inconceivable that wellbred women could be anything but talented amateur artists, and the school offered no “practical” courses in the decorative arts such as porcelain or fan painting for those who had to work to earn a living. Besides, the thinking went, it would be morally improper to have male and female students working together in the presence of nude models of either sex, so it was best to exclude women altogether.

* Among the Canadians who studied at the Julian were Peleg Franklin Brownell, William Blair Bruce, William Brymner, Florence Carlyle, William Henry Clapp, Maurice Cullen, Clarence Gagnon, A.Y. Jackson, John Goodman Lyman, James W. Morrice, Robert Pilot, Maurice Prendergast, George Agnew Reid, and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté. The Catalogue général des élèves from the Julian shows that, before the turn of the century, the school had provided training for more than sixty male students from Canada. Tobi Bruce and Patrick Shaw Cable, The French Connection: Canadian Painters at the Paris Salons, 1880–1900 (Hamilton, Ont.: Art Gallery of Hamilton, 2011), 20.

The atmosphere was quite different in the many private academies that were founded in the late 1860s and readily opened their doors to thousands of foreign students of all ages, with no required entrance examinations or recommendations. Art education soon became big business, though fees were reasonable and a variety of options were offered. Within a few years these schools welcomed women from all over Europe and abroad who chose to study in Paris. The most popular with American and Canadian artists were the Académie Julian* – the largest art school in the city, founded in 1868 by the École-trained artist and wrestler Rodolphe Julian (figs. 3.1 and 2, AB.12) – and the Facing page Plate 3.1 ■ William Clapp, By the Summer Sea [detail], c. 1906, oil on panel, 26 x 34.3 cm, private collection. Following pages Fig. 3.1 ■ Female art students crowd together in a classroom at the Académie Julian, 1885.

The French Scene: Pari S and Be yond

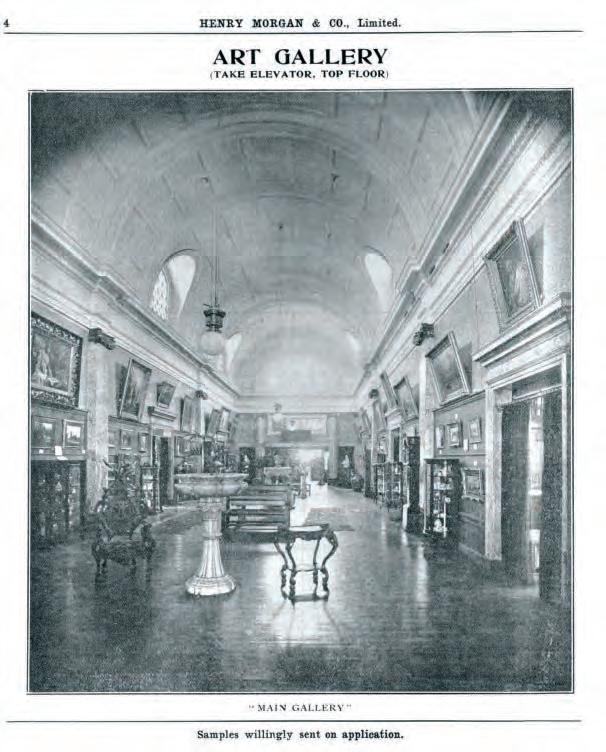

sculptures changing every four or six weeks.7 Around the turn of the century, James Morgan opened a gallery in the large department store owned by his family, Morgan and Co., and in 1906 he was joined by his son F. Cleveland Morgan (figs. 5.6–8). Between 1901 and 1914 they held several exhibitions and came to play a significant role in the life of Clarence Gagnon (see chapter 18).

In 1897 John Ogilvy, a dignified Scot, opened the first gallery in Montreal devoted exclusively to art, at 83 St. François Xavier Street.8 He sold contemporary English, French, and Dutch paintings and, given his location near the Montreal Stock Exchange, had many brokers among his clients. In his opinion, however, Canadian art was “too noisy to mix with quiet Dutch pictures,” so he didn’t feature it or the local artists in his gallery.9

above Fig. 5.6 ■ Morgan & Co. department store on St. Catherine Street, c. 1890.

right Fig. 5.7 ■ James Morgan, Montreal, 1891.

facing page Fig. 5.8 ■ An advertisement in the Henry Morgan & Co. 1909 spring/summer catalogue for the picture gallery that James Morgan Jr. opened on the top floor of the department store around the turn of the century. Morgan’s prided itself on selling the highest-quality goods. The gallery, trading in works by Corot, Poussin, and other masters, reinforced this image.

* Here Reid exaggerates: many serious artists could not afford to go to Paris, and others preferred to go to the Art Students League in New York, for example, or to study with Thomas Eakins in Philadelphia.

† In the cold air of the Canadian winter, everything in the landscape appears to be more brightly coloured and clearly defined than in the misty air of Western Europe or the milder temperatures of most parts of the United States. As A.Y. Jackson remarked, “After the soft atmosphere of France, the clear, crisp air and sharp shadows of my native country … were exciting.” A.Y. Jackson, A Painter’s Country: The Autobiography of A.Y. Jackson (Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1958; reprinted 1976), 16.

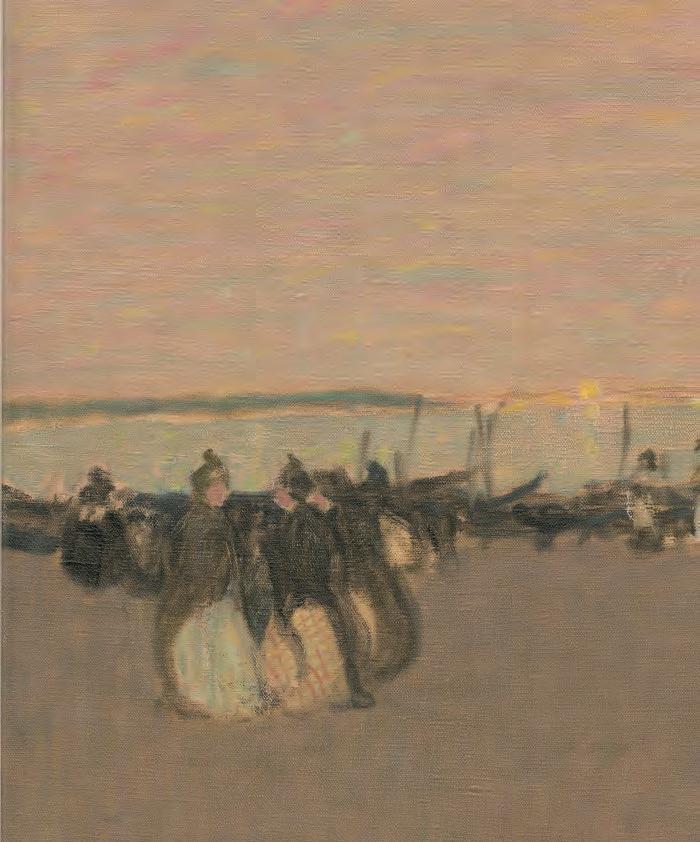

Previous Pages Plate P.1 ■ James Wilson Morrice, Evening Stroll, Venice [detail], c. 1905, oil on canvas, 50.2 x 60.7 cm, private collection.

In both the United States and Canada, as had happened earlier in France, interest in Impressionist art began soon after major political changes in each country. Artists, along with the rest of the population, felt optimistic about the future and rejoiced in their freedom from past restraints. In this new environment, a few painters and their supporters on both sides of the forty-ninth parallel turned away from traditional Academic forms of artistic expression and experimented with new techniques and subject matter. What defined these artists as Impressionists was not only the way they painted but their choice of subject matter as well.1

For the Americans, the end of the bitter Civil War in 1865 provided the kickstart. In the following several years the now united country enjoyed a period of great prosperity and industrial development, and artists reflected the resulting sense of civic pride in their images. For Canadians, the achievement of Confederation in 1867 and the building of the transcontinental railway began the process of unifying the country coast to coast and fostered a burgeoning sense of nationalism. Over the next two decades, several major national institutions of culture were founded – the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, the Royal Society of Canada, and the National Gallery of Canada – along with a small number of local art associations and magazines that covered the arts and hoped to educate the populace about these finer aspects of life. It seems that in both countries, despite the political and economic challenges and ambiguities stemming from the transition from an agrarian to an industrial society, a new-found confidence inspired the most ambitious among painters to go abroad for further education in the art capitals of the world, particularly to France. Dennis Reid made the point well: “Every serious young artist in Canada aspired to study in Paris, and by the early 1890s they all did.” 2 *

Both Canadian and American painters of the time created portraits, interior scenes, and figural images –of middle-class women reading or sewing, of young

people enjoying leisure pursuits, and of children, often with their mothers – all subjects that reflected the bourgeois aspirations of the collectors who were expected to buy the paintings for their homes. They tended to avoid representations of hard labour, class tension, or destitution, such as Pissarro’s peasants in the fields or Degas’s laundresses and solitary drinkers, though they did portray fruit-pickers and children doing light chores around the farmyard.

Among painters who focused on landscape, however, the Canadian Impressionist artists who painted in their own country depicted a somewhat different subject matter from their American counterparts. True, they all sketched, if not painted, outdoors, so they captured whatever landscape or figures or objects they saw before them.† But aside from such regional variations, there is another significant distinction in their work. The American Impressionist artists, with an eye to the future, were fascinated by progress: they included automobiles, multi-storey buildings, electrical wires, and fashionably dressed city dwellers in their urban scenes, while their rural images featured prosperous working mills and people relaxing in boats or on beaches along the coast.

The Canadian Impressionist painters, in contrast, generally favoured nostalgic themes over the contemporary – the Old Towns of Montreal and Quebec City, river crossings, horse-drawn vehicles, and unchanging small villages and rural scenes of habitant life north along the St. Lawrence River to the Côte-de-Beaupré. In particular, they painted winter landscapes of abundant snow in all weathers and times of day, and scenes of the annual spring thaw along the streams in the mountains. Perhaps they regarded the cold northern winter and this traditional way of life, already passing, as the most distinctive aspects of Canada, or perhaps they simply found that the people who bought their works had conservative tastes and preferred to buy paintings with these familiar themes.

What more can we say in general to introduce the Canadians who chose to paint in an Impressionist style and to distinguish them from their American counterparts? Most of the Canadians were from Quebec and spoke English as their first language, though some who had a French-speaking parent were perfectly bilingual. Very few were women, and proportionately more of them came from provinces other than Quebec. Although most of these artists are best known as landscape painters, some were talented in other areas too: Laura Muntz Lyall earned her living primarily from portraits of women and children; Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté was as famous for his sculptures as his canvases; and Clarence Gagnon excelled also as an engraver and an illustrator.

Almost all these young artists had already received some art education in schools that followed the traditional French Academic curriculum – drawing first from plaster casts and then from live models, always in the classical style. Once they arrived in Paris they tended to live in the student areas on the Left Bank and to register in three academies in particular, often working under the same professors at the privately owned Académie Julian or Académie Colarossi or at the staterun École des Beaux-Arts. In the long summer break, many of them visited the popular “painting places” in Normandy and Brittany or the art colonies at Grèzsur-Loing and Moret-sur-Loing, where they painted outdoors, en plein air. William Blair Bruce alone went to Giverny, where he was influenced by Monet and his own group of American friends. Others went further afield to paint, into Holland, Spain, and Italy, or even in search of the exotic Al-Maghrib in Algiers and Morocco in North Africa. Not surprisingly, the young Canadians came to share many memories and, for some, a similar aesthetic sensibility.

The course of study they followed at the academies in Paris was again the Academic program. Their greatest ambition was to have a work accepted for exhibition at one of the Paris salons, and they submitted paintings year after year, often with success (see Appendix C). Anxious to make their reputations in Canada as well,

they regularly sent canvases home to the annual shows sponsored by the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, the Art Association of Montreal, and the Ontario Society of Artists, as well as to exhibitions in Chicago, Buffalo, St. Louis, and other American cities. Overall, they took their fair share of medals and prizes.

As they strolled though Paris and talked about art with their friends and their instructors in the cafés, the Canadian students quickly came under the influence of the new Impressionist art on display in the more progressive exhibitions and the galleries of avant-garde art dealers such as Paul Durand-Ruel and Georges Petit. And, as they painted outdoors in the warmer months, they experimented with this style themselves – striving to catch the light of the transient moment in quick, flickering brushstrokes of bright, pure colour. The particular influence they experienced, however, depended on the exact period of their stay in France. The earliest of them, such as William Brymner and James Barnsley, arrived at the height of French Impressionism, when the rebellious “intransigents” were organizing their own group exhibitions. The majority of the Canadians, however – including the best known among them, Maurice Cullen, James W. Morrice, Suzor-Coté, and Gagnon – arrived after the final Impressionist show in 1886, so they experienced a far wider range of influences, from the Impressionism of Monet, Renoir, and Degas to the Pointillism of Sisley and Seurat, the Post-Impressionism of Cézanne, the Expressionism of Van Gogh, and the Fauvism of Gauguin and Matisse.*

As a result of their training and their exposure to a variety of progressive art movements in Europe, each of the Canadian Impressionist painters developed a unique style, albeit one that shared certain characteristics with other members of the group. In general, like the French Post-Impressionist artists and the American Impressionists, they were dedicated to form, giving a three-dimensional appearance to the figures, buildings, and objects in their paintings, though the backgrounds of their images were often more Impressionist in tone – atmospheric and rendered

* Many Canadian art students in Paris were also attracted to the Japanese prints and decorative objects that had been popular there since the 1860s. In 1890 a large exhibition of Japanese art at the École des Beaux-Arts caused considerable excitement among the Impressionist artists in the city.

of the “finished” canvases by late-eighteenth-century English artists or by nineteenth-century artists from the Barbizon and Hague schools, and they considered this pioneering artist’s works gaudy, if not crude. Blair Bruce did what he could to help his friend and arranged for the sale of two paintings, The Dam, Passy and Wash Houses on the Seine, to Hamilton collector W.D. Long.

Some experts have written that Cullen returned to Paris for a few months during the spring of 1896, but although several of his paintings from this period depict Canadian scenes, there are none of Europe. Cullen was, moreover, impoverished and had only recently come back from France, so it seems implausible that he would return there after only a few months.3 There is, however, evidence that he registered at the Louvre in April to copy paintings by Greuze and Velázquez, so the trip he planned may have been a brief one, specifically to fulfil a copying commission.4

In the early summer of 1896 Cullen, along with Brymner, travelled north along the St. Lawrence River to Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, just north of Quebec City. He would repeat this trip often over the coming years, sometimes with Morrice and Brymner, painting Cap Diamant, the shipyards at Lévis, the houses and glowing shop windows in the Old Towns of Montreal and Quebec City, and the Beaupré region in all seasons and weathers, from lush summer landscapes to frozen rivers, blizzards, and snowstorms (plates 8.4 and 5). He excelled in crisp winter landscapes in the radiant northern light, scenes such as his well-known Logging in Winter, Beaupré from 1896 (see plate I.5). He was determined to record the texture and varied colours of his country in impasto layers of paint – and no other Impressionist artist did it better.

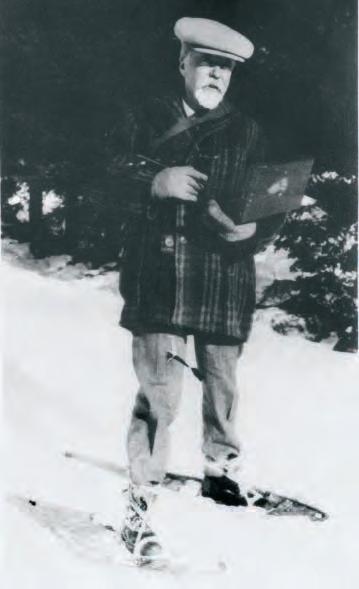

Gradually Cullen developed his own method and techniques. He always sketched out-of-doors, even if it meant standing in freezing temperatures on snowshoes (fig. 8.2). He made his own small painting boards from the wood of young poplars; after dr ying them in heat, he plunged them in boiling linseed oil and painted them with a layer of white lead.

Fig. 8.2 ■ Cullen, equipped with snowshoes and his painting kit, at Saint-Jovite, Quebec, in 1925.

Maurice Galbraith

Plate 8.4 ■ Quebec from Lévis, 1897, oil on canvas, 58.8 x 80 cm, private collection.

in London and in Dordrecht, Holland, to view the museums and the galleries there. He would never live permanently in Canada again.

Once he arrived in Paris, Morrice enrolled at the Académie Julian, but his stay was short – from January 20 to March 10, 1890. When a boisterous student hit him on his already balding head with a baguette one day, he left in a huff – and with no later regrets. As his early biographer Donald Buchanan explained, he “at once left Julian’s for ever, and glad he was to have done so, for as he used to tell his friends, his sudden departure prevented him from ever falling under the horrible influence of [William] Bouguereau.” 3

Morrice arranged to take lessons for a few months with the elderly painter Henri Harpignies, who had a

studio at 14, rue de l’Abbaye. Though traditional in his style, Harpignies understood the Impressionist artists’ concern for atmosphere and the effects of light in their works, and he encouraged his students to paint outdoors. This tuition was probably the only formal instruction and critique the basically self-taught Morrice ever received. From Harpignies, Morrice developed a taste for a delicate touch and a subtle, subdued palette, broken only by strokes of heightened colour to represent figures in his landscapes (plate 9.1). The influence of Harpignies was, however, short-lived: by the early 1890s Morrice had shifted his interest from rural to urban life (plate 9.2).

Despite his regular stipend from his family, Morrice always lived quite frugally in Paris. After a few

Plate 9.2 ■ A Street in Paris, c. 1895, oil on canvas, 22.9 x 30.5 cm, private collection.

temporary lodgings, he rented a studio at 41, rue SaintGeorges in Montmartre (where he met the famous art dealer and publisher Ambroise Vollard in his shop on nearby rue Laffitte),4 then in 1899 moved to an apartment in the Latin Quarter, at 45, quai des GrandsAugustins. The view of the Seine and the imposing Palais de Justice opposite was splendid, but the rooms were sparsely furnished and untidily kept – his tweed suits, however, were always immaculately tailored and his beard well trimmed, complementing his gentlemanly demeanour (fig. 9.3). Finally, in 1916 he went to a slightly larger space further along the Seine at 23, quai de la Tournelle, overlooking Notre-Dame, but he never felt really at home there.

By day Morrice tended to be a loner, sketching what

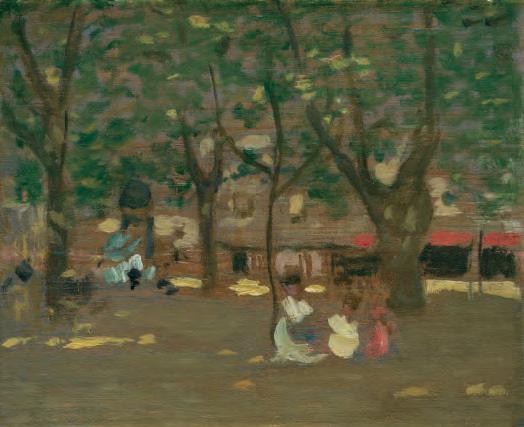

he observed as he sat in a public square or café, often with a liqueur to hand. He was attracted by tranquil scenes from a passing age – elegantly dressed women and men at leisure, horse-drawn vehicles, and garden squares, but never by signs of urban progress. The art critic Marius-Ary Leblond expressed it well: “One has the impression always that he is painting on a Sunday afternoon.” 5 The figures in his paintings often have an air of being alone, even when in the company of others (plates 9.3–5). At night Morrice became more gregarious and headed to one of the cafés where he knew he would find a group of friends.

In his early years in Paris, Morrice was not fluent in French, so his companions were almost all Englishspeakers. He was well read and loved poetry, and he

Plate 9.3 ■ Place du Tertre, c. 1902, oil on panel, 11.4 x 16.5 cm, private collection.

Plate 9.30 ■ The Crossing, c. 1912, oil on board, 12.7 x 15.2 cm, private collection.

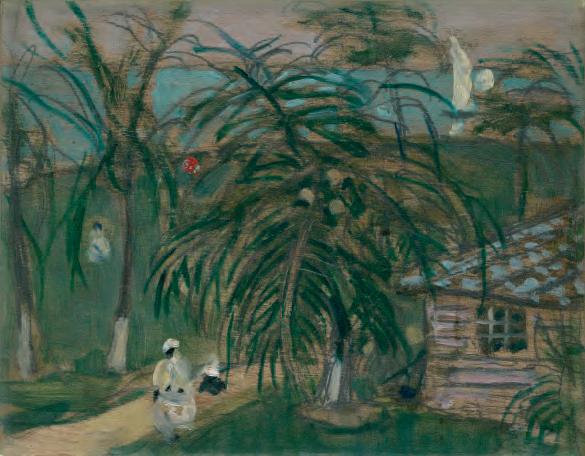

Plate 9.31 ■ Jamaica Landscape, c. 1921, oil on panel, 12.7 x 16.5 cm, private collection.

Plate 9.32 ■ The Regatta at Cancale, c. 1905–10, oil on panel, 23.7 x 33 cm, private collection.