Lynn Holstein

Lynn Holstein

Lynn Holstein, author, After earning an M. A. with distinction in Middle Eastern Studies from Harvard University, where she focused on Islamic art and architecture, Lynn served in administrative posts in a number of educational and cultural institutions. They include the Jewish Museum in New York, The New York Public Library, Harvard University, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

From 2000–2004, she lived in Jerusalem directing Israeli industrialist Stef Wertheimer’s New Marshall Plan for the Middle East initiative. For the past decade, she has shared both her work and home life with Mr. Wertheimer and has continued to promote his various programs. All are aimed at bringing peace to the region by educating skilled professionals, developing industrial parks, and creating jobs for all sectors of Israeli society.

In addition to this book, she is writing another that examines the challenges of the rapidly changing Bedouin community in Israel’s Negev region. She also adapted Mr. Wertheimer’s very successful autobiography (originally published in Hebrew) for an international English readership. Entitled The Habit of Labor, Overlook Press released it in November 2015.

Foreword

Lynn Holstein

“Craftsign”

Where craft and design can merge into a new paradigm

Ezri Tarazi

Jewelry and Metalworking

Vered Babai

Doreen Mirvish Bahiri

Shirly Bar-Amotz

Ben Zion David

Indimaj Jewelry School

Vered Kaminski

Itay Noy

Sharon Sides

Rami Tareef

Ceramics and Glass

The Armenian Ceramics-Balian Ltd

Tenat Auka

Beit Gemal Ceramics

Zenab Garbia

Shamai Gibsh

Dafna Kaffeman

Meir Moheban

Ayala Serfaty

Simone Solomon

Fiber and Leather

Ahat Ahat

Hertzel Auster

Gali Cnaani

Irit Dulman

Yael Herman

Lakiya Negev Weaving Project

Maskit

Moshe Roas

Aleksandra (Sasha) Stoyanov

Nuni Yavnai Weaving Art

Zaitonat el Batof Visitor Center

Paper

Ido Agassi & Even Hoshen

The Gottesman Etching Center

Jerusalem Print Workshop-Djanogly

Graphic Arts Center

Tut Neyar

Wood and Soap

Eli Avisera

Amir Azoulai

Maia Halter

Muhamed Said Kalash

Erez Perelman

Asaf Weinbroom

Gamila Secret

Acknowledgments

Biographies

Bibliography

Artists’ Contact Information and Map

Arabic Translation – Basilius Bawardi

Hebrew Translation – Galia Vurgan

ly rigid rods into a family of stools that fit within one another like the parts of a Russian Matryoshka doll. In 1991, she showed new jewelry in a solo exhibition at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Some pieces were made of concrete, a substance no one would have considered a proper material for jewelry until recent times. In the late 1960s, two Dutch jewelers helped to usher in the New Jewelry movement in Europe that reassessed jewelry’s role in society by introducing items such as a stovepipe necklace. This bold redirecting of traditional ideas of jewelry making set the stage for unlikely new materials, such as concrete. But concrete too was a learning process, and Vered relates that she made trays and trays of concrete items before she developed the proper technique.

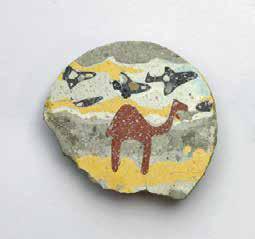

Her concrete jewelry displays many images, but the pieces with camels are a clever adaptation of a well-known tourist gift—a bottle into which different colors of sand are ingeniously poured to render the animal in its desert landscape. Using a process akin to that of terrazzo floor tiles, Vered has made brooches and bracelets showing camels and palm trees with cement, pigment, and sand from the Negev Desert.

Top left: earrings that demonstrate the mathematical principle of “two to the power of six”. Top right: a concrete brooch.

Vered is one of Israel’s leading jewelers, a statement that was underscored in 2014 when she received the Andy Prize for Contemporary Crafts. Charles Bronfman had created the prize 10 years earlier to celebrate his late wife’s commitment to the arts. Vered has received other prestigious awards as well: First Prize in the Crate & Barrel Israeli Product Design Award for the Home and Its Surroundings; the Israeli Ministry of Science, Culture and Sport Prize for Design; the International Judaica Design Competition for the 3,000-year anniversary of Jerusalem (co-winner with Esther Knobel and Leo Contini); the Alix de Rothschild Foundation Prize for Judaica; and the Shapiro Prize for Judaica.

Recognition of one’s talents comes in different ways, however. Certainly it was an honor when President Shimon Peres commissioned her to make a gift for the Chancellor of Germany, Angela Merkel, to mark the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II. Vered made a brooch for her, and, as was fitting, she used the national stone of Israel called the Eilat stone, or the King Solomon Stone. This vivid, greenish-blue stone is a composite of several minerals, such as turquoise, malachite, and azurite. She used a complex pattern of wire to hold the stones and fastened it with a trombone clasp.

Her work has also been on exhibition in the world’s most distinguished museums and galleries, such as the Schmuckmuseum in Pforzheim, Germany; the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo and Kyoto; Kulturhuset in Stockholm; the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris; the Ra Gallery, Amsterdam; the

Royal Museum, Edinburgh; and the Racine Art Museum in Wisconsin, to name just a few.

Although much of her work is of an abstract nature, Vered sees a personal historical dimension in it. “Everyone is connected to something in the past,” she tells me. “Behind each item stands a person and a host of international memories.” She comes from a family who worked with their hands. In Poland, her grandmother made hats. On Kibbutz Revadim, where Vered was born in 1953, her father repaired cars. Her fascination with architectural forms and structures stems from the late 1980s, when she was studying for her master’s degree at the University of Paris VIII, Vincennes-Saint-Denis. Her son was playing in an enclosed area, and Vered became captivated by the fence. This interest has influenced a great deal of her works ever since.

A good mathematics student, some of her work is informed by geometrical progression. Consider her delicate mobile earrings, where each structural level doubles the weight of the one above it. Or her earrings that embody 64 small silver oblong pieces that are based on “two to the power of six.” Or her highly delicate metal branches that explore the concepts of coming together and coming apart.

Vered’s grid-like brooch, although seemingly abstract, is connected to her past. She states that “behind each item is ... a host of international memories.”

Respectful of her materials, she attributes to them a sense of geometry as well. She tells me of a time she wanted to make cubes, “but the silver wanted to be two pyramids, so I understood that I had made the structure of diamond-shaped forms.”

It is worth noting that Vered herself wears no jewelry. She feels that jewelry is worn to advance “emotional, spiritual, social, and other goals.” In a recent interview with curator Maya Vinitsky, Vered explained why she chooses to go unadorned. “I view it as a serious commitment to stand behind a piece of jewelry.”

× × × × × × × × ×

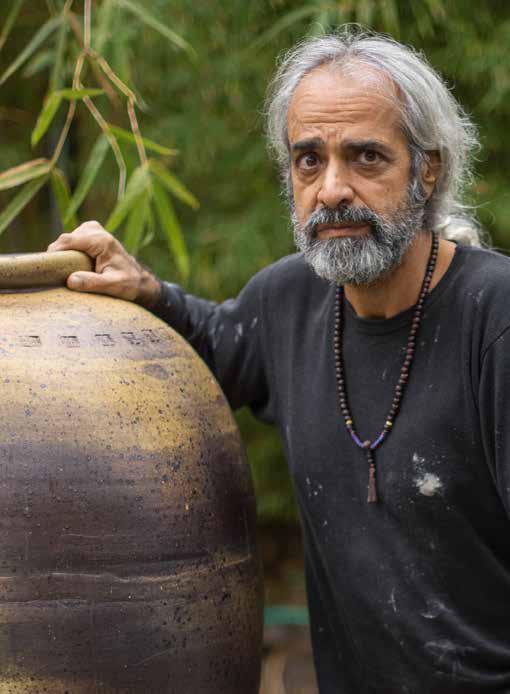

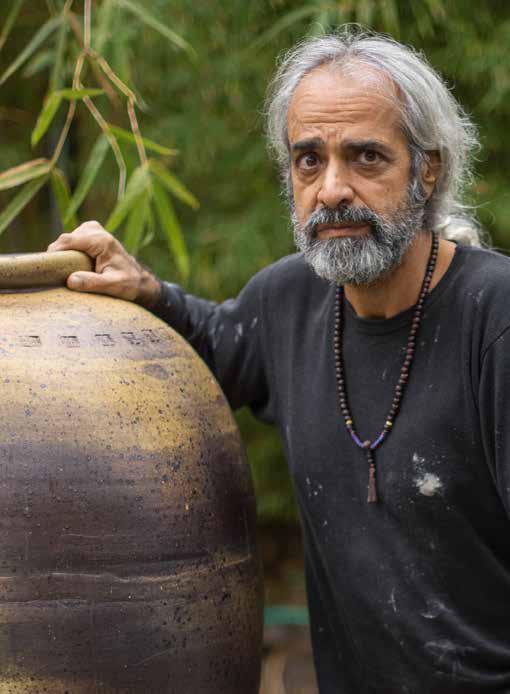

once a year

Like Nevada’s Burning Man event, Meir Moheban’s kiln is an annual attraction. It draws artists and ceramic lovers to his pastoral site in Pardes Hanna, where they come and go for seven days helping to keep his enormous kiln afire at 1,300 degrees Centigrade (ca. 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit).

The kiln, which Meir built himself in 2008, adheres to the ancient anagama method of firing that was transmitted from China to Korea around the 12th century. It uses a continuous supply of wood that produces fly ash and volatile salts in the curing process. The kiln is a curved-roofed structure 1.8 meters wide and 1.8 meters high (almost 6 feet) at its sole opening, which becomes more cramped as it

wends its way up a slight incline. It comprises 25 tons of bricks, and, if placed upright, it would be as tall as a three-story building. In its field of green vegetation, it looks like a half-buried archeological site.

This enormous structure comes to life only once a year. It takes three weeks to prepare the kiln, of which seven days are needed to reach the correct temperature. It provides heat to cure the clay, and its wood ash provides the glaze for the objects that remain in constant flames for five to six days. It takes Meir two days to unload the kiln, after which he holds a sale. He has no idea what his works will look like when they emerge. The variation in the

Meir’s work has been influenced from the artistic traditions of Iran, from which his parents came in 1950, as well as those of other Middle Eastern countries. He has particular esteem for Palestinian pottery.

glaze depends on the location of the items in the kiln, their proximity to one another, and the type of clay. Meir uses a variety of clays to achieve different results. Then another six weeks are required for him to review the remaining pieces. Sometimes the items get stuck together or damaged, and Meir states that he must “cure” them.

However, he has been influenced by wabi-sabi, the Japanese belief that beauty lies in the imperfect, so he makes no attempt to seal the cracks. “I seek out the perfect in the imperfect, and … it is often the random imperfection of a pot that gives the piece its own individual perfection.”

Although Meir never lived in Iran, the country where his parents left around 1950 to make their home in Israel, he has incorporated some of its artistic traditions. He grew up with Persian items that his parents had bought. In the 1970s, he took a trip with his mother to Isfahan, a city with many buildings bedecked with some of the world’s great ceramic tiles. This and art from other areas of the Middle East also inform his work. He also reveres the ceramic work of the Palestinians. “If I work another 50 years, I will not be able to achieve the skill of the Palestinian potters.”

His gallery is just steps from his kiln, and there one can find graceful bowls, irregularly shaped boxes, eggs, jars, plates, teapots and cups, works on three legs that he terms tripods, vases, and vessels. Some of his works are large, and these he makes in sections, using coiling and then the wheel.

Meir states that he was “old” when he started to learn pottery: 30. A certified public accountant by training (a career that still provides him with a livelihood), he took his first pottery course in Queens, New York, and “fell in love.” He then moved to Woodstock, New York, took pottery classes at the State University of New York at New Paltz, and became the apprentice of Paul Cheleff, whose works are in the collections of the leading American museums. Meir’s works have been shown in exhibitions throughout Israel and also in the Fifth International Ceramics Competition in Mino, Japan, where, in 1998, he received an honorable mention.

This egg coat and the iconic desert coat on the following page are updated versions of items that made Maskit famous decades ago. They are proof that good design lasts.

A visitor to Moshe Roas’s studio in southern Tel Aviv might think she has stumbled into a storage area for items found in archaeological digs. Lacy metal works with the patina of time, a partial suit of mail in the process of decomposition, a leather-like fragment with images that look like prehistoric art— these are the first objects to catch one’s eye. It all begins to make sense when Moshe describes his interest in the processes of construction and deconstruction and in the themes of history and memory. His delicately wrought works evoke fearful thoughts of natural and man-made catastrophes, as well as philosophic contemplations of where we have come from and where we are headed.

Textile design was Moshe’s field of study for his degree at the Shenkar College of Engineering and Design, and his passion for fabric can be seen in his work. But he has expanded his palette by etching

unlikely combinations of materials, such as sponge, sand, asphalt, glass, metals, and loofah.

He started his final project at Shenkar by studying the history of carpets. He purchased several types of carpets and took them apart, feeling as though he was delving into history in the process. He then chose the loofah plant, a member of the cucumber family, for his project, as it embodies the main elements of life, with veins and a skeletal structure. Through deconstructing and reconstructing the plant’s fibers, he came up with a new and unique process to make carpets. The result was a thin lace surface that he dyed with natural coloring and then coated with silicon for stability and cleaning purposes. For this achievement, he received the college’s Printing Master award. He then used this process to create large, colorful baskets that add a joyful dimension to an interior.

This innovative basket made of loofah is similar to the carpet that garnered Moshe the Printing Master award during his studies at Shenkar.

variety

Erez is one of only about 50 people worldwide who call themselves luthiers. He learned the field mainly on his own after studying classical guitar in California with Celin Romero.

wood-carving. One of Erez’s boyhood works in this medium, a wooden sculpture of an owl, stands sentry over his workshop. His mother was born in Israel to parents who came from Romania. Erez’s family moved to the United States when he was 10, and he chose to return here only a few years ago.

He is quick to point out that the most important aspects of a guitar are sound and comfort. He enjoys working with his clients to develop an instrument that is ideal for them. This might mean modifying the size of certain components of the guitar. Often people send him a tracing of their hand to determine the best size for the neck of the instrument. He is currently working with a client who had a motorcycle accident, building a guitar that will be comfortable for him to play while not compromising its tone. Erez is modest about his talents, so it is with some difficulty that he tells me that his intuition is his specialty. He knows wood and its properties and can determine through his hands which is the best wood and how to shape it to bring out the qualities that his clients desire. Finding the right wood is a critical part of his work, and after searching in various places, he found a source in the Swiss Alps near the German-Austrian border. A large stack of it occupies a corner of his workshop, where it undergoes the curing process that can take years before it is suitable for use.

Although Erez prides himself on a handmade product, he has used his engineering background to

devise a simple machine to bend the wood into the well-known curves of a guitar. His father built a temperature controller for the machine. And yet it is the hand tools that define Erez’s work. On a high shelf is a group of planes. He takes down his favorite, a 100-year-old tool that seems to work more smoothly than its modern counterparts.

While the various tools of the workshop are impressive, it is impossible to dismiss the aesthetics of his instruments. Erez scours carpet books for inspiration for his rosette, which he considers the signature of his guitars. This ornamental feature that encircles the opening behind the strings is made of inlaid wood and takes a month to complete. He cooks and dyes each segment. Another demand-

ing aspect is the French polish that provides the guitar with its external sheen. Applying successive thin coats of shellac made from the excretion of beetles in India is exacting work that also takes about a month and can cause injuries, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, from the repetitious hand movements it requires. The significant effort for the French polish is worthwhile, however, as it results in a very responsive instrument that is unsurpassed by any other polish.

Erez has trained for several careers—computer scientist, engineer, and luthier. A comment that he made in passing, however, perhaps describes him best: an architect of sound.