INTRODUCTION

Jaś Elsner and Stefanie Lenk

Imagining the Divine sets out to explore the creation of the art of some of the world’s great religious traditions – the faiths we now know as Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam – in the first millennium a D It is easy to assume that the major religions of the world are fixed entities, distinct from each other in many respects, notably in their arts. Yet this book, and the exhibition that accompanies it, show that this has never been the case. Religious images, even the most iconic ones, are the product of encounter: dialogue, influence and differentiation.

All religions have developed images and symbols that are markers of identity – instantly recognisable to their followers and to adherents of other faiths. These images differ significantly from one another, effectively emphasising certain beliefs that each religion’s adherents have wanted to stress. Take a classic form of the Buddha, for example: a typical Tibetan thangka, or painting on silk (no.2) of the later fifteenth century shows him in the posture of touching the earth to quell the demons of illusion immediately before his enlightenment. Or take the icon painted on wood in Crete in the same century, showing Christ enthroned in glory between the Virgin Mary and St John the Baptist who intercede with him for the sake of believers (no.3). These images embody their faiths, manifesting the personal charisma of the religion’s founder in figural form.

They stand in contrast to what are usually viewed as the more abstract, or aniconic, affirmations of religions such as Judaism and Islam. One example is the parochet, or linen curtain, embroidered in silk and silver gilt thread; it was made in Venice in a D 1676 to cover the Ark that contained the biblical scrolls in a synagogue. The parochet portrays the tablets of the law in the centre and a series of Jewish festivals in the small scenes with oval borders containing Hebrew script which adorn the frame around the central image (no.1). Likewise, the beautifully ornamented certificate of pilgrimage to Mecca (the Hajj), made in ink and gold on paper and dating from a D 1432/3, shows some key sites, including the Ka’ba sanctuary in Mecca (with different stations of pilgrimage), Muhammad’s tomb at Medina and the relic of his sandal (no.4). Both these objects, visually typical of their religions, include sophisticated evocations of ideal artefacts and architecture, but are careful to avoid the depiction of persons or animals. By contrast again, Hinduism affirms not just multiple gods, but many aspects of the same god in different shapes, and in imagery that may include animals as well as the human form. A fine painting in watercolour

1 Parochet AD 1676

used in every religion, engaging the body of the worshipper with the moving dynamic of ritual action. These objects are decorated with imagery that marks them as distinctive to the religion concerned, imagery that is often extended to decorate the places where worship is conducted and to distinguish these as special. When people become involved actively and dynamically in the practice of religion, it is objects and the ways in which they are decorated – with distinctive signs such as the Buddhist wheel, the Zoroastrian fire altar, the Christian cross or the Jewish menorah (sevenbranched candelabrum) – that provide identity and self-definition. The most significant symbols in any religion refer back to the initial period of their visual formation. It is through objects that we can read both the rise of religious identities and the patterns of religious change.

o bjects an D the format I on of bel I ef

Imagining the Divine examines some of the different ways in which material objects transmit or accommodate new religious ideas. It does so while also tracing some of the historical development of the major religions as they evolved from early phases into initial periods of maturity. A recurrent motif in the formation of religious imagery is the use of images that carry ambiguous messages or combine elements that may seem incompatible to us today. While one side of an Egyptian amulet from the sixth century depicts scenes of the life of Christ, for example, the other side combines a depiction of the Egyptian god Horus in the upper half with Jewish symbolism in the lower half (no.29). Did the owner privilege one of these beliefs over the others? Were the magical powers of the various pictures and symbols used in different situations or in combination? The exclusive belief in one god is central to the Christian and Jewish doctrines, but was foreign to the religious understanding of most people of the ancient Mediterranean world. More than half a century after Christianity had emerged, the owner of this amulet was still convinced that Jewish, Christian and ancient Egyptian images could be of assistance, and were not mutually exclusive.

10

Coin of Heraclius c.AD 638–41

Constantinople Gold; Diam. 2.1 cm

Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, hr C 43807

Heraclius is portrayed on this coin between his sons and co-rulers Heraclius Constantine and Heraclonas. On the other side a cross is raised on a high pedestal (perhaps representing Calvary). It is accompanied by the legend ‘Victory of the emperors’.

Objects like this one remind us that personal beliefs are often more multifaceted than religious doctrine permits.

Multivalent imagery could be used more systematically to adapt and appropriate religious ideas first formulated by other faiths. In fact there is a strong tradition in many cultures of a continuous use of visual formulae across religions. For instance, the image of a shepherd carrying a sheep was probably initially a form of votive offering in ancient Greece, becoming in the Roman empire a way of representing such gods as Hermes Kriophoros, ‘the ram bearer’ (no.33). Because of a powerful series of Scriptures that defined Jesus as the Good Shepherd, Christians could easily see the image of a sheep-bearer as a representation of Christ or as a symbol of their faith. In South Asia, various early cults and visual representations of a number of deities were conflated in the fifth and sixth centuries a D to create the visual culture of what subsequently became Hinduism. The deity Vishnu (no.5) is today understood as being manifested in ten avatars – different aspects of a single, multi-form divine identity that were gathered in the course of the first millennium. Rama and Krishna, originally local heroes later celebrated in epic poetry, were incorporated as avatars into the cult of Vishnu, as was the Buddha, a relatively late addition to the Vaishnavite pantheon. Here the integration of cults into a larger religious system was a result of competition and self-definition in relation to other local belief systems and religious practices. To this day, the idea of avatars as emanations of Vishnu is fundamental to Hindu belief and practice. In another example, the animal interlace that covers the richly ornamented pages of Britain’s early medieval gospel books (no.172) had a previous life before its inhabitants converted to the Christian faith (no.165). Here the amuletic significance of animal imagery and knotwork designs, apparently used as binding motifs as well as talismans to ward off evil, seems to have continued from pagan traditions into Christian art.

In the process of incorporating pre-existing religious ideas and playing with allusions, visual fluidity encountered limits. As religions become more established, they seek to standardise their imagery, despite continuing experimentation. When Vishnu was carved in mid-eleventh century Bengal, the images of avatars around his frame numbered ten, the standard quantity today (no.84). Earlier religious art had depicted varying constellations and often smaller numbers of avatars. Although the identities of avatars were sometimes modified in future centuries to reflect local traditions, the sculpture of Vishnu marks a discernible phase in the standardisation of images of, and beliefs about, the deity.

Standardised forms are particularly interesting in the ways they define religions in opposition to other beliefs. Whereas the pagan cults of the ancient world, for instance, used an extraordinarily rich range of statuary for all kinds of rituals and worship, Christians dropped almost any use of three-dimensional images by c a D 400 for several centuries. This is a striking

c.AD 100–200

Found in Cyrene, Libya Carved marble; H. 175 cm © The Trustees of the British Museum, 1861,0725.2

worship (as well as different expectations of the divine) existed at various sites and points in time, even before Greeks began to reinterpret this figure as Zeus.2

These combinations may appear remarkably straightforward: ‘Serapis’ or ‘Ammon’ were simply added to the name Zeus, and his image was supplemented with a headdress or ram’s horns respectively. The repetition of names and images, found in very similar combinations across the Greek and Roman worlds, do indeed attest to the uniformity and singularity of these gods. Yet these combinations also indicate a less rigid and more fluid sense of what an ancient god was.

All of these figures are the result of comparison, encounters and occasionally fusions between religious traditions, whether Egyptian, Greek or Roman. The construction of ancient gods can be seen as an attempt to grasp the divine and indefinable, by giving it a name and visualising it in material form. But such firm groundings could play host to a variety of interpretations, encompassing a range of religious beliefs and practices.

The names and images of deities brought together many of the dynamic, oscillating ideas that ancient peoples had about the supernatural. Far from curtailing concepts of the divine, they allowed for their transmission and development. We should understand the word ‘god’, in its ancient context, to denote a name and a group of image types to which people could pin all kinds of stories, beliefs, hopes, manners of worship and expectations, which were never expected to be consistent.3

o ne go D , many roles: D I onysus

Such flexibility in thinking about gods can be illustrated by considering the variety of contexts in which deities appear. As with Zeus or Jupiter, we may believe we have a strong sense of the god Dionysus (or Bacchus, to give him his Roman name): he was the god of wine, the grape harvest, theatre, fertility and ecstatic (‘Bacchic’) frenzy (no.18). His name summons up notions of orgies and mysteries; Renaissance paintings typically show a debauched youth surrounded by grapes and a crowd of wild-eyed followers. Yet the idea of Dionysus in antiquity was more subtle than this, and open to far wider interpretation. Nor were the images attached to the name Dionysus straightforward.

Dionysus and his followers are among the most frequently depicted motifs in Greek and Roman art, but the actual contexts of such images differ greatly. This is not surprising if we consider the range of media across which he was represented, including statues, reliefs, sarcophagi, vases, paintings and a whole host of other forms. Even though these images all show Dionysus, did they all necessarily have a religious function? Was his primary role as a god? Or did he play some other part in the mind of the person viewing or interacting with the object on which he was portrayed? 18

Found at a Temple of Dionysus, this was evidently a cult statue. The wreath of ivy leaves, the bunch of grapes in his left hand and the ivy-leaf detail on his sandals all emphasise Dionysus’s status as a god of wine.

Statue of Dionysus

ENVISIONING THE BUDDHA

Robert Bracey

Siddhartha Gautama was born as a royal prince sometime in the fourth or fifth century bc. As a religious preacher he is better known by his title of Buddha, meaning ‘the Awakened One’. Though images of the Buddha do not form a central part of every Buddhist sect’s practice, he is still one of the most widely recognised religious figures of the modern world. Even many non-Buddhists will know the serene figure dressed in simple monastic robes, his eyes half-closed in meditation (no.62).

b efore the f I rst I mage

The ubiquity of the Buddha’s image today contrasts dramatically with the early history of Buddhism. Following Gautama’s death in the fourth century bc, his teachings – originally preserved through memorisation – gradually developed into a complex religion with institutions and written texts. The Buddha’s core teaching was that each of us is trapped in a cycle of rebirths by our actions (karma); particular religious practices would allow his followers to break free of this cycle and perceive the insubstantial, illusionary nature of the world. That teaching, with much variation, was promulgated by an order of monks and nuns (the sangha), and spread throughout the Indian subcontinent as far as Pakistan and Afghanistan in the north and Sri Lanka in the south. Yet for generations, until at the earliest the first century a D, there were no images of the Buddha in human form.

Some Buddhist artists went to great lengths to avoid depicting the Buddha himself. They created complex scenes but invented symbols (footprints, a royal parasol) to represent the Buddha. Amaravati, located in the modern state of Andhra Pradesh on the east coast of India, was an important Buddhist centre in the early centuries a D. It possessed a stupa, a popular form of domed monument in early Buddhism, in which relics were often interred; a stupa could be circumambulated as an act of devotion but usually could not be entered. The exterior of the stupa at Amaravati was richly decorated with carved panels and encircled by an elaborate series of railing pillars. These were carved between the first and the third centuries a D and, at least initially, the Buddha was not portrayed in his human guise. Instead the artists would indicate the Buddha by showing some trace of his passing or an object associated with him, for example his footprints (no.63).

96

Statue of Parashurama with Varaha c.AD 1000–1200

Rajasthan (?)

Carved sandstone; H. 54.5 cm

© The Trustees of the British Museum, 1880.335

This fragment of a frame for a larger statue depicts Parashurama, the warriorascetic incarnation of Vishnu, and his boar avatar Varaha. Born into a priestly caste, Parashurama was motivated after his father’s death to rid humanity of the Kashatriya, or warrior caste.

97 Rama

c.AD 1300–1400

South India

Cast bronze; H. 22.3 cm

Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, EA 2013.98

Rama is the hero of the Ramayana epic, which recounts his life and struggles. Following exile into the forest for 14 years, together with his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana, he eventually returns triumphantly to his kingdom of Ayodhya. Rama’s status as an avatar of Vishnu has remained an enduring aspect of his persona.

98

Illustration from the Balagopalastuti, featuring the infant Krishna c.AD 1475–1500

Gujarat Watercolour and ink on paper H.23.2 cm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS .81-1963

This folio is from a dispersed manuscript of the Balagopalastuti, or ‘Hymns in Praise of the Infant Krishna’, by the poet Bilvamangala. Here the infant Krishna is shown playfully interrupting the churning of milk by the cowgirls (gopis).

Anglo-Saxon and British cultural zones, however, raises questions about the route by which the censer had travelled.

The Roman provinces of Britannia had been at the periphery of the empire, and the isolation of the British Isles after the Western Empire’s fall meant that they continued to be considered the edge of the world. St Patrick described his mission to Ireland as a dangerous expedition to ‘the most remote districts beyond which nobody lives’.139 An eleventh-century Anglo-Saxon map (no.153), based on a source of c a D 800, depicts the place of the British Isles within the world: the cartographer has squeezed

[ 172 ] chr I st I an I ty I n the br I t I sh I sles

151

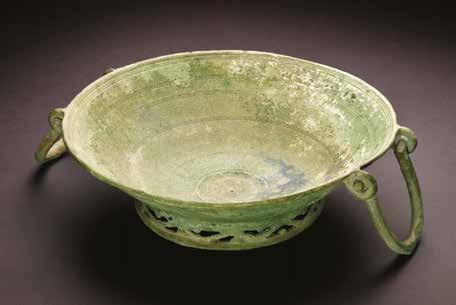

Decorated bowl

c.AD 500–700

Found at Faversham, Kent

Cast and engraved copper alloy; Diam .25.7 cm

Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, AN 1942.257

Vessels of this type have been discovered in central and western Europe, Anatolia and Egypt. They were evidently produced in the eastern Roman empire, then exported westward by land and sea.

152

Censer

c.AD 500–700

Found at Glastonbury Abbey, Somerset

Cast copper alloy; H. 7.2 cm

Eastern Mediterranean

© The Trustees of the British Museum, 1986,0705.1

This censer’s hemispherical body is decorated simply with concentric lines. It stands on three feet or may be suspended by a long chain. Deposits of ash and gum resin found inside the censer attest its use for burning incense and myrrh.

153 (opposite)

World map

c.AD 1025–1100

England

Tempera and ink on parchment; H. 26 cm

The British Library, London, Cotton MS

Tiberius B V.1, fol.56v

This map shows the continents of Europe, Asia and Africa (west is at the bottom). It precedes the fifth-century Latin translation of a description of the known world, composed originally in Greek c.AD 130.

SUBJECT INDEX

This index is in alphabetical, word by word order. It does not cover the contents list, list of contributors, acknowledgements, foreword, preface or endnotes. Location references are to page number and figure number, and appear in that order. For names of places, see Index of geographical names. For names of people, see Index of personal names.

Abbasid caliphate, 23, 27, 126, 140, 157, 160–61 coin, 157Fig142 map, 222

Agni Purana, 116, 123, 122Fig101 see also puranas

Allington Disc, 181, 185, 183Fig165 see also brooches

Alvar Saints, 121, 123 amulets, 47, 71, 46Fig29 amuletic gemstone, 71, 71Fig51 amuletic tablet, 47Fig30 fabric, 98, 99Fig78

rock crystal with kufic inscription, 78Fig57

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 193, 195, 193Fig178

Anglo-Saxon kingdoms coins, 175, 177Figs156–7 combining pagan/Christian traditions, 190, 192, 192Fig177 conversion to Christianity, 174–5 culture, 168–71 maps, 172, 174, 173Fig153 motifs adopted by Christians, 181, 185–7, 182–5Figs162–7 aniconism

Buddhism, 163–4 Islam, 147, 150–51, 157, 162–4 Judaism, 162–3

Arabic language, 135–6 architectural ornament, 27, 122–3, 143, 26Fig11, 144Figs122–3, 145–6Figs125–6 Ark of the Covenant, 69, 74 see also Judaism; Torah, The

Balagopalastuti, illustration from, 119Fig98

Ballycottin Cross, 177, 181, 204, 211–12, 180Fig161 see also brooches

Barmakid family, 157, 160–61 belt buckles, 168–9, 169Fig148

Bhagavata cult, 110–11, 115 Bhagavad Gita, 116 Bhagavata Purana, 78, 111, 113, 112–13Figs89–90

Bhagavata cult cont.

Heliodorus Pillar, Besnagar, India, 110Fig86

Bible, The see also Christianity; Gospel books; scripture in Arabic, 135 colour scheme of early Bibles, 154 formation of visual narrative, 59 Royal Bible, 175, 178Fig158 biblical scenes ewers, 61Fig43 glass roundels, 60Fig41 ivory panels, 58Fig40 replacement of Roman art by biblical narratives, 56–9 sarcophagi, 56–7, 59, 56Fig38 textiles, 60Fig62 Vinica tiles, 64–7, 65–7Fig46(a–i) wall paintings, 21–2, 69, 22Fig28, 54Fig37 book covers, 116Fig93, 179Fig159 books see also Bible, The; Quran; Torah, The adoption of Indian stories into Islam, 161

book-page with pen trials, 184Fig166 Karaites Book of Exodus, 136Fig112 Lives of the Hermits Paul and Guthlac, 190, 192, 191Fig176 bottles, 140Fig117 bowls decorated copper alloy, 171, 172Fig151 hanging bowl bases, 190Figs173–5 incantation bowl, 82–3, 83Fig61 lustreware, 160–61, 160Fig144 magico-medicinal, 157, 156Fig140 silver with mounts, 186, 186Figs168–9 silver with St Sergius, 149Fig132 brooches

Allington Disc, 181, 185, 183Fig165 Ballycottin Cross, 177, 181, 204, 211–12, 180Fig161

disc-shaped, 170, 171Fig150, 183Fig164 Rogart Brooch, 181, 182Fig162 Buddhism, 13, 18, 110

Buddhism cont. adaptation of images from other religions, 90, 93 aniconism, 163–4 Buddhist images in early-Islamic art, 160–61, 160Fig144 development of faith, 110, 113 Divya Prabandha, 202 early history, 21, 85 female patronage, 105, 107, 107Fig83 Heart sutra, 77, 80, 204, 82Fig59

Hellenistic influence on images, 97–8 imagery, effect of inter-cultural encounters on, 93–6, 157 imagery, effect of trade on, 96–8 reliquaries, 95, 95Fig72 stupas, see stupas sutras, 77, 98, 204, 81Fig59 busts, 33Figs16–17, 209Fig186 see also heads

Byzantine Empire, 17, 23, 154, 222

caskets, 192–3, 195, 192Fig177 censers, 171, 62Fig45, 172Fig152 ‘chi-ro’ symbol, 45, 51, 42Figs25–6, 44Fig27

Cholas, rulers of southern India, 121 chrismatory, 180Fig160 Christianity, 13, 24, 77 see also Bible, The; biblical scenes; Christ adoption of earlier motifs in representations, 40–41, 51, 55–8, 181, 185–7, 190, 182–5Figs162–7, 186–90Figs168–75 combining with pagan traditions, 190, 192–3, 195, 192–4Figs177–9 conversion of Angle-Saxon kingdoms to, 174–5 creation of specific representations, 51–2

Crucifixion scenes, 58–9 early regional context, 21 establishment of in British Isles, 167–9 establishment of in Roman Empire, 51 icon of Christ, 63

Christianity cont. idolatry, fear of, 22, 27 networks across Europe, 170–5, 177, 181 patriarchal sees, 51

Reformation, 17–18

symbolic representation, 55–6 translation of writings, 21 use of images from Jewish tradition, 59–61 chronological table, 218–21 coins, 23, 29

Abd Allah b. Khazim, 127Fig106

Abd al-Malik, 147, 147–8Figs128–31

Agathocles, 97Fig74

Anglo-Saxon, 175, 177Figs156–7

Bar Kochba, 70Fig48

Chandragupta, 124Fig103

Claudius II, 40Fig23 coin pendant, 170, 170Fig149

facilitation of spread of symbols, 205

Gratian, 124Fig102

Heraclius, 24Fig10

Islamic coinage, removal of figurative imagery, 147–9

Kanishka, 94, 94Figs70–71

Khosro I, 139Fig115

Majorian, 44Fig27

Maues, 98Fig77, 111Fig87

Menander, 97Fig75–6

Muqtadir Billah, al-, 157, 157Fig142

Salm b. Ziyad, 139Fig116 use of Roman coins by Anglo-Saxons, 170 conch shell symbol, 114, 114Fig91, 121Fig100

Crondall Hoard, 175, 177Figs156–7 crosses

adoption as Christian symbol, 51 Ixworth Cross, 181, 182Fig163

St Cuthbert’s Cross, 182Fig173

Staffordshire Hoard cross, 181,185Fig167 cults, integration into religious systems, 25

Dashavatara Temple (Deogarh, India), 109–110, 109Fig85 diplomatic gifts, 171, 177, 204 discus (chakra), 114, 108Fig85, 112Fig88, 120–21Figs99–100 dishes, 23Fig9

Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem, 126, 149–50, 154, 162, 202, 163Fig145 donors, see females, donors

empires of the ancient world, 18 ewers, 61, 61Fig43, 141Fig118

Fatimid rulers, 150, 150Fig133

females

donors, 104–5, 107, 104–7Figs80–83 figures, 89, 90, 89Fig66 sacred females, 102–3 figures, male, 89–90, 20Fig7 floor mosaics

Hinton St Mary, Dorset, 42, 45, 124, 42–3Figs25–6, 44Fig28 synagogues, 22, 69, 70Fig49 footprints, 85, 87, 163–4, 86Fig63 friezes, 145Fig124, 150Fig133

Glorification of Germanicus, The (Peter Paul Rubens), 38Fig21

Gods/demigods conflating of imagery, 49, 49Fig32 difficulty of defining, 39 simultaneous worship of deities from different religions, 46–9, 51 Gospel books, 25, 77, 174Fig154 decoration with pagan designs, 186–7 Northumbrian Gospels, 187, 187Fig170 Rawlinson Gospels, 77Fig56 St Augustine Gospels, 175, 190, 176Fig155

St Chad Gospels, 80, 187, 190, 188Fig172 grave goods, 168, 182Fig163, 183Fig165 Gupta kings (India), 109, 111, 113

Hajj, 203 pilgrimage certificate, 13, 16Fig4 heads, 32Fig15, 90–91Figs67–8 see also busts

Heart sutra, 77, 80, 204, 82Fig59

Heliodorus Pillar, Besnagar, India, 110–11, 110Fig86 Hinduism, 13, 17, 21, 25, 109, 157

iconoclasm, 128–33, 129–32Figs107–10 idolatry

Christianity, 27, 37 Islam, 147, 155, 157, 161 Judaism, 69 incantation bowls, 82–3, 83Fig61 see also bowls

inscriptions amulets, 71–2Figs51–2, 78Fig57 Cave of Hoq, Socotra, 137 combining multiple traditions, 195–6, 192Fig177, 197Fig180 disc brooch, 171Fig150 incantation bowl, 83Fig61 Islamic inscriptions in public spaces, 150 ladle, 157, 156Fig141

Lancaster Cross, 196, 167Fig147

Llywel Stone, 167, 196, 197Fig180 magico-medicinal bowl, 157, 156Fig140

inscriptions cont. plate, 135Fig111

scriptural texts on personal objects, 78 Tiraz fabric bands, 126, 126Fig105, 150Fig134 tomb-marker, 52Fig34 tombstones, 53Fig35, 82Fig60 wooden frieze, 150Fig133 intaglio, with menorah, 68Fig47 interlace designs, 181, 185, 167Fig147, 182–5Figs162–7

Iranian Empire, 18 Islam, 13, 77 see also Muslim caliphate; Quran aniconism, 147, 150–51, 157, 162–4 coinage, replacement of figurative images, 147–8, 147–8Figs128–31 continuity of artistic production under, 139–43, 140–41Figs117–18 cross-cultural influences on art, 157, 159–61, 157–8Figs142–3, 160Fig144 epigraphy, 147, 149–51 figurative imagery, avoidance of, 27, 147 figurative imagery, in conquered lands, 136–7 foundation, 135 jihad, 135 mihrab (prayer niche), 131–2, 131Fig109 rise of, 17–18, 27 transformation of visual traditions, 147–9 Umm al-Kitab, 155 ivories

book cover, 175, 179Fig159

panel: Bellerophon killing the Chimera, 28Fig12

panel: Christ enthroned, 41Fig24 panel: New Testament scenes, 59, 58Fig50

Ixworth Cross, 181, 182Fig163 see also crosses; pendants

Jain religion, 88, 90, 107, 157 development of faith, 110, 113 head of a Jina, 91Fig68 head of Parshavanatha, 90Fig67 seated Jina, 107Fig83 jars, 159, 158Fig143 jihad, 135 see also Islam Judaism, 13, 21–2 see also menorah; synagogues aniconism, 162–3 destruction of the Temple, 74 symbols on domestic and funerary objects, 70–71 use of imagery, 69–72