A RTEMISIA

Publisher’s Note Federico Ferrari

Artemisia’s Challenge Asia Graziano

On Her Own Terms Claudio Strinati

Our Lives with Artemisia Gregory Buchakjian

The Roman Education of the Talented Painter

Success and Acknowledgement in Medici Florence

Lights and Shadows of the Venetian Stay

The Neapolitan Consecration

Caritas Romana, or the Celebration of Feminine Virtue

Artemisia’s Letters

Artemisia in the Archives Sheila Barker

Bibliography

Index of the Artworks by Artemisia Gentileschi

L’impresa di Artemisia

Asia Graziano

Per presentare la complessa e affascinante figura di Artemisia Gentileschi è bene partire dalla sua opera manifesto: l’Allegoria dell’Inclinazione in Casa Buonarroti. Questo lavoro della giovinezza, per forza iconografica e splendore formale costituisce il vero biglietto da visita dell’artista e restituisce l’immagine, opacizzata dalla lettura in chiave femminista e psicoanalitica della sua esperienza, di Artemisia come artista completa. La Gentileschi era abile pittrice per sinuosità della pennellata, ma specialmente in ragione dei raffinati interessi culturali che sottendono le audaci scelte iconografiche. L’Allegoria dell’Inclinazione stringe tra le mani un curioso oggetto: un compasso magnetico, strumento di cui la pittrice era probabilmente venuta a conoscenza dallo scienziato Galileo Galilei. Il rapporto amicale tra i due, incontratisi per la prima volta a Roma, è testimoniato da un carteggio che continueranno a intrattenere anche quando Artemisia vivrà a Napoli e Galileo sarà relegato agli arresti domiciliari nella casa di Arcetri. La naturale abilità di Artemisia di legarsi ai massimi esponenti dell’élite culturale del tempo, la porteranno a frequentare i circoli letterari e le accademie di ogni città in cui è attestato il suo passaggio. La giovane era stata chiamata a contribuire al programma iconografico per celebrare il più grande artista del secolo scorso, nella sua dimora natale. L’Allegoria doveva raccontare la naturale predisposizione di Michelangelo alle arti. La figura femminile di incredibile bellezza e grazia che la pittrice ci regala, è però decisamente autoreferenziale: Artemisia ci parla della sua inclinazione alle arti, più che di quella del Buonarroti. L’opera è un chiaro autoritratto della pittrice, che nel corso della sua carriera artistica continuerà a rappresentarsi nei panni della pittura. Artemisia non solo si presenta come l’incarnazione dell’ispirazione, della forza creativa e dello spirito artistico, ma lo fa nella dimora che ha visto crescere il più grande artista mai esistito. La commissione diviene l’occasione per presentarsi nel capoluogo fiorentino – dove si era da poco trasferita –, con fierezza e ambizione, come nuova protagonista dell’Arte, paragonandosi e anzi proponendosi come erede di Michelangelo. Questo deliberato ribaltamento in chiave autobiografica dell’impianto iconografico previsto dal committente è significativa testimonianza della sfrontatezza e della determinazione di Artemisia. L’Allegoria cita la Battaglia dei Centauri: la pittrice omaggia il primo Michelangelo scultore e rafforza l’identificazione con la sua personale esperienza, di giovane promessa dell’arte. In quest’opera, troviamo già esplicitate le peculiarità del lessico artistico di Artemisia: l’identificazione con il soggetto rappresentato, la stratificazione di significati, la complessità iconografica, l’auto-affermazione attraverso la citazione dei grandi maestri e al contempo il guanto di sfida lanciato alla tradizione figurativa. L’esperienza di Artemisia costituisce un unicum nel panorama artistico moderno occidentale, non paragonabile a quella delle colleghe Giovanna Garzoni, Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani o Fede Galizia, cui viene spesso associata per il semplice denominatore comune della questione di genere. Artemisia non è solo una donna pittrice di successo in un mondo di

(pp. 8, 11, 12-13) Artemisia Gentileschi, Autoritratto come allegoria della Pittura, 1638-1639, olio su tela, 98,6 × 75,2 cm, Royal Collection Trust, Londra. Intero p. 240.

Artemisia’s

Challenge

Asia Graziano

To present the complex and fascinating figure of Artemisia Gentileschi, it is best to start with her manifesto work: the Allegory of Inclination in Casa Buonarroti. This work from her youth, in terms of iconographic strength and formal splendour, constitutes the artist’s true calling card and restores the image, dulled by the feminist and psychoanalytic interpretation of her experience, of Artemisia as a complete artist. Gentileschi was a skilled painter due to the sinuosity of her brushstrokes, but especially to the refined cultural interests underlying her bold iconographic choices. The Allegory of Inclination clasps a curious object in her hands: a magnetic compass, an instrument that the painter had probably learned about from the scientist Galileo Galilei. The amicable relationship between the two, who met for the first time in Rome, is testified by a correspondence that they would continue to maintain even when Artemisia lived in Naples and Galileo was relegated to house arrest in the Arcetri house. Artemisia’s natural ability to bond with the leading exponents of the cultural elite of the time led her to frequent the literary circles and academies of every city in which her passage was attested. She was called upon to contribute to the iconographic programme to celebrate the greatest artist of the last century, in his birthplace. The Allegory was meant to tell of Michelangelo’s natural inclination to the arts. The female figure of incredible beauty and grace that the painter gives us, however, is decidedly self-referential: Artemisia tells us about her inclination to the arts, rather than that of Buonarroti. The piece of art is a clear self-portrait of the painter, who throughout her artistic career continued to represent herself in the guise of painting. Artemisia not only presents herself as the embodiment of inspiration, creative force and artistic spirit, but she does so in the home that witnessed the greatest artist who ever lived. The commission becomes an opportunity to present herself in the Florentine capital – where she had recently moved –, with pride and ambition, as the new protagonist of Art, comparing herself and indeed proposing herself as Michelangelo’s heir. This deliberate autobiographical overturning of the iconographic structure envisaged by the commissioner is significant evidence of Artemisia’s boldness and determination. The Allegory cites the Battle of the Centaurs: the painter pays homage to the first Michelangelo the sculptor and reinforces her identification with her personal experience as a young promise of art. In this work, we already find explicit the peculiarities of Artemisia’s artistic lexicon: identification with the represented subject, stratification of meanings, iconographic complexity, self-assertion through citation of the great masters and, at the same time, the gauntlet thrown down to the figurative tradition. Artemisia’s experience constitutes a unicum in modern Western art, not comparable to that of her colleagues Giovanna Garzoni, Lavinia Fontana, Elisabetta Sirani or Fede Galizia, with whom she is often associated due to the simple common denominator of gender issues. Artemisia is not only a successful woman painter in a world of male painters. Unlike her female colleagues, she is

(pp. 8, 11, 12-13) Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as Allegory of Painting, 1638-1639, oil on canvas, 98.6 × 75.2 cm, Royal Collection Trust, London. Entire p. 240.

pittori uomini. A differenza delle colleghe, è pittrice di istoria: la sua pratica non è relegata ai generi naturalmente destinati alle donne che si cimentavano nella pittura, il ritratto e la natura morta. La Gentileschi dipinge soggetti storici e biblici, partecipa a grandi commissioni come l’Apostolado per il Duca di Alcalá, ottiene incarichi pubblici e viene accolta nelle principali corti del Barocco europeo, anche oltre i confini nazionali. Intrattiene rapporti di sincera amicizia, condivisione culturale e di intenti con i principali artisti, umanisti, scienziati e intellettuali del periodo. Artemisia riesce a conquistarsi un posto d’onore nella cultura dell’epoca, trovando significativo riconoscimento presso i più importanti signori del tempo, tra cui Ferdinando de’ Medici e Filippo IV di Spagna, oltre che presso la critica contemporanea, che la celebra senza precedenti. Sarà proprio Artemisia la prima pittrice a fondare una bottega e gestire un atelier d’artista, dimostrandosi abile e caparbia agente di sé stessa. Invia opere dimostrative, doni e scrive forsennatamente per accaparrarsi le migliori committenze, rifiutandosi anche di contrattare il prezzo delle sue opere. Artemisia non è la vittima indifesa e impaurita, che cerca di superare il trauma biografico attraverso la catarsi artistica, ma una professionista instancabile, determinata, orgogliosa e sicura di sé e della sua arte, con la quale supera la tradizione, sfidandone i massimi esponenti.

a painter of history: her practice is not relegated to the genres naturally destined for women painters, the portrait and still life. Gentileschi painted historical and biblical subjects, participated in large commissions such as the Apostolado for the Duke of Alcalá, obtained public commissions and was received in the main courts of the European Baroque, even beyond national borders. She forged relationships of sincere friendship, cultural sharing and intentions with the leading artists, humanists, scientists and intellectuals of the period. Artemisia succeeded in gaining a place of honour in the culture of the time, finding significant recognition with the most important lords of the time, including Ferdinand de’ Medici and Philip IV of Spain, as well as with contemporary critics, who celebrated her without precedent. It was precisely Artemisia who was the first female painter to found a workshop and run an artist’s atelier, proving herself a skilful and stubborn agent. She sends demonstration works, gifts and writes frantically to grab the best commissions, even refusing to haggle over the price of her works. Artemisia is not the defenceless and frightened victim, who tries to overcome her biographical trauma through artistic catharsis, but a tireless, determined, proud and self-confident professional and her art, with which she surpasses tradition, challenging its greatest exponents.

Il fatto suo

Claudio Strinati

Non c’è dubbio alcuno sul fatto che Artemisia Gentileschi sia una delle prime artiste in assoluto ad aver dato un forte significato autobiografico alle sue opere.

Non è un caso isolato e non è, beninteso, la prima ma tanto più interessante è il fatto che è stata proprio una donna, e di grandissimo talento e ferrea volontà, a rimarcare con tanta energia e intelligenza questa attitudine autobiografica all’interno del corpus delle opere, ovviamente ordinatele dai più diversi committenti e quindi sempre incentrate su soggetti non necessariamente scelti o interpretati dall’artista stessa.

Nella pittura o nella scultura, peraltro, l’autobiografismo è sempre trapelato in modi incerti e contraddittori, persino nei casi in cui l’artista abbia messo la propria immagine all’interno di composizioni prescrittegli dalla committenza e quindi non modificabili più di tanto rispetto all’obbligo iconografico.

Per Artemisia lo si è notato da subito, quasi che l’immissione del dato autobiografico nelle sue opere corrispondesse ad una insopprimibile esigenza personale, tanto più sentita da una donna già di per sé all’epoca repressa nelle libere manifestazioni del suo pensiero.

Ma è notevole osservare come proprio su questo punto si siano verificate nella storiografia, sia essa maschile sia femminile, delle vere e proprie deformazioni interpretative cui questo libro intende porre almeno in parte rimedio attraverso una analisi mista di grande passione emotiva e rigoroso controllo delle fonti.

Inutile quasi rimarcare come il luogo comune da cui non si riesce a liberarsi a proposito dell’autobiografismo evidente in alcune opere cruciali di Artemisia, stia nel rapporto pressoché necessitante e dato come per scontato, tra il processo per stupro del 1612 e le varie versioni del tema di Giuditta e Oloferne di cui le più celebrate sono quelle di Napoli e Firenze relative alla scena della decollazione. Artemisia, si è sempre detto e raccontato, subisce lo stupro poi, umiliata e offesa dallo svolgimento del processo, trova il modo dopo l’emanazione della sentenza di condanna verso Agostino Tassi, di – sia pur metaforicamente – vendicarsi raffigurando la scena di Giuditta che uccide Oloferne con una sorta di rabbioso e insieme disgustato compiacimento, là dove il maschio è nitidamente visto quale nemico, arrogante stupratore e fedifrago appunto.

Ecco, il fatto suo, verrebbe da dire guardando quei quadri indubbiamente notevolissimi e impressionanti.

Ma ci possono essere parecchie obbiezioni a questa tesi, certo espressa forse troppo radicalmente ma senza dubbio circolante nella esegesi gentileschiana e non certo da tempi recenti.

Del resto il tema della Giuditta con la testa di Oloferne (non la decapitazione vera e propria, a onor del vero) era già un topos della pittura femminile se non altro con le opere, più volte reiterate e datate tra gli ultimissimi anni del Cinquecento e i primi del Seicento, di Fede Galizia.

On Her Own Terms

Claudio Strinati

There is no doubt that Artemisia Gentileschi is one of the first artists ever to have given a strong autobiographical meaning to her works. This is not an isolated case and she is, of course, not the first, but all the more interesting is the fact that it was precisely a woman, of great talent and iron will, who so energetically and intelligently emphasised this autobiographical attitude within the corpus of her works, obviously ordered by the most diverse commissioners and therefore always centred on subjects not necessarily chosen or interpreted by the artist herself.

In painting or sculpture, moreover, autobiographism has always transpired in uncertain and contradictory ways, even in cases in which the artist has placed his or her own image within compositions prescribed to him or her by the commissioner and thus not altered more than the iconographic obligation.

In the case of Artemisia, it was noted from the outset almost as if the inclusion of autobiographical data in her works corresponded to an irrepressible personal need, all the more felt by a woman who at the time was already repressed in the free manifestation of her thought.

But it is remarkable to observe how precisely on this point there have been true interpretative distortions in historiography, both male and female, which this book intends to remedy at least in part through a mixed analysis of great emotional passion and rigorous control of the sources.

It almost goes without saying that the commonplace that one cannot get rid of regarding the autobiography evident in some of Artemisia’s crucial works lies in the almost necessary and taken for granted relationship between the rape trial of 1612 and the various versions of the Judith and Holofernes theme, the most celebrated of which are those of Naples and Florence relating to the scene of the beheading.

Artemisia, it has always been said and recounted, undergoes the rape and then, humiliated and offended by the course of the trial, finds a way – albeit metaphorically – to take her revenge after the sentencing of Agostino Tassi, by depicting the scene of Judith killing Holofernes with a sort of angry and at the same time disgusted satisfaction, where the male is clearly seen as the enemy, the arrogant rapist and the faithless one.

There her own terms, one would say looking at those undoubtedly remarkable and impressive paintings.

But there may be many objections to this thesis, certainly expressed perhaps too radically but undoubtedly circulating in Gentileschi exegesis and certainly not since recent times.

After all, the theme of Judith with the head of Holofernes (not the actual beheading, to tell the truth) was already a topos in female painting, if only with the works, repeated several times and dated between the very last years of the 16th century and the early 17th century, of Fede Galizia.

(pp. 14, 17, 18, 22-23, 86) Artemisia Gentileschi, Autoritratto come suonatrice di liuto, 1615-1618, olio su tela, 77,5 × 71,8 cm, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford. Intero pp. 86-87.

(pp. 14, 17, 18, 22-23, 86) Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as Lute Player, 1615-1618, oil on canvas, 77.5 × 71.8 cm, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford. Entire pp. 86-87.

Le nostre vite con Artemisia

Gregory Buchakjian

Il 21 dicembre 1976, Women Artists: 1550-1950 fu inaugurata al Los Angeles County Museum of Art. La mostra, che ha attirato 110.923 visitatori prima di spostarsi in altre tre città, e la pubblicazione che l’ha accompagnata sono state pietre miliari nello studio scientifico della “graduale emancipazione delle artiste dopo il XVI secolo e della loro lotta per superare le barriere sociali che impedivano la loro formazione artistica e i loro obiettivi di carriera”.1 Mary Garrard scrisse che “solo cinque anni fa, l’idea di una grande mostra storica sulle donne artiste sarebbe stata impensabile”.2 L’esposizione, al contrario, interrogava i più appassionati sulla questione delle artiste donne: se dovessero, in futuro, essere trattate come donne artiste o come artiste. A conclusione della sua recensione, la Garrard ha osservato che “concepire le artiste in quanto donne artiste è un modo furbo per rafforzare la loro alterità, relegandole a qualche anello distante di non competitività, dove non devono essere viste affatto, se non come una categoria speciale”, aggiungendo che “ora che sono state presentate come donne, è tempo di spostare l’enfasi e di esaminare i loro risultati come artiste, modellate da una varietà di esperienze personali, non ultima né la più importante delle quali è stata quella di essere nate di sesso femminile”.3

Women Artists: 1550-1950 comprendeva opere delle pioniere Sofonisba Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana e Artemisia Gentileschi. Rappresentata da cinque opere, la Gentileschi era tutt’altro che sconosciuta, soprattutto a causa della sua vita romanzata. Qualche anno prima, R. Ward Bissell ammetteva che “comprensibilmente, spesso i primi scritti più interessanti e illuminanti riguardano le norme morali della pittrice. Alcune osservazioni o insinuazioni sono reazioni a una donna che svolge un lavoro tradizionalmente maschile. Tuttavia, ancora più attraenti per gli aneddotisti sono stati il disprezzo di Artemisia per il marito e il processo contro Agostino Tassi nel 1612 per il presunto stupro subito nella primavera dell’anno precedente”.4 Come Caravaggio, ma per motivi opposti, la vita della Gentileschi è un perfetto insieme di dramma, passione, violenza e potere. Come ha affermato accuratamente la Garrard, “continuerà a essere romanzata fino all’ultima sillaba della sua storia documentata”.5 Nella vasta produzione di

Our Lives with Artemisia

Gregory Buchakjian

On the 21st of December 1976, Women Artists: 1550-1950 opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The exhibition that drove 110,923 visitors before traveling to three other cities and the publication that accompanied it were milestones in the scholarly study of “the gradual emancipation of women artists after the sixteenth century and their struggle to overcome the social barriers that impeded their artistic education and career goals.”1 Mary Garrard wrote that “as recently as five years ago, the idea of a major historical exhibition about women artists would have been unthinkable.”2 The display conversely questioned the most enthusiasts whether women artists should, in the future, be treated as women artists or as artists. In the conclusion of her review, Garrard noted that “to complement women artists as women artists is a clever way to enforce their otherness, consigning them to some distant ring of non-competitiveness, where they don’t have to be seen at all, except as a special class”, adding that “Now that they have been displayed as women, it is time to shift the emphasis and to examine their achievement as artists, shaped by a variety of personal experiences, not the least nor the most of which was being born female.”3

Women Artists: 1550-1950 included works by pioneer figures Sofonisba Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana and Artemisia Gentileschi. Represented by five pieces, Gentileschi was far from being unknown, notably due to her romanticized life. A few years before, R. Ward Bissell admitted that “understandably, often the most interesting the most illuminating of the early writings about her moral standards. Certain remarks or insinuations are predictable reactions to a woman performing what was traditionally a man’s job. However, even more attractive to anecdotists have been her disregard of her husband and the trial of Agostino Tassi in 1612 for the alleged rape of Artemisia in the spring of the previous year.”4 Like Caravaggio but for opposite reasons, the life of Artemisia Gentileschi is a perfect set of drama, passion, violence and power. As Garrard accurately asserted, it “will continue to be fictionalized until the last syllable of recorded time.”5 Among the abundant production of texts and movies that usually share the same title – the artist’s

1 Robert M. Isherwood, “Reviewed Work(s): Women Artists, 1550-1950 by Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin”, The American Historical Review, vol. 82, n. 5, dicembre 1977, pp. 1215-1216.

2 Mary Garrard, “Women Artists in Los Angeles”, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 119, n. 892, luglio 1977, pp. 530-532.

3 Ibid.

4 R. Ward Bissell, “Artemisia Gentileschi-A New Documented Chronology”, The Art Bulletin, vol. 50, n. 2, giugno 1968, pp. 153-168.

5 Mary Garrard, “Inventing Artemisia”, Art in America, vol. 89, n. 1, 2001, pp. 35-39.

(pp. 24, 27, 30, 32-33, 113, 114-115, 116-117) Artemisia Gentileschi, Giuditta e la sua ancella, 1625-1627, olio su tela, 182,2 × 142,2 cm, Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit. Intero p. 112.

1 Robert M. Isherwood, “Reviewed Work(s): Women Artists, 1550-1950 by Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin”, The American Historical Review, Vol. 82, No. 5, December 1977, pp. 1215- 1216.

2 Mary Garrard, “Women Artists in Los Angeles”, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 119, No. 892, July 1977, pp. 530-532.

3 Ibid.

4 R. Ward Bissell, “Artemisia Gentileschi-A New Documented Chronology”, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 50, No. 2, June 1968, pp. 153-168.

5 Mary Garrard, “Inventing Artemisia”, Art in America, Vol. 89, No. 1, 2001, pp. 35-39.

(pp. 24, 27, 30, 32-33, 113, 114-115, 116-117) Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith with Her Maidservant, 1625-1627, oil on canvas, 182.2 × 142.2 cm, Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit. Entire p. 112.

Caritas Romana , ovvero la celebrazione della virtù femminile

Quella della Caritas Romana di Artemisia Gentileschi è una vicenda intricata e avvincente. Non tanto per le cronache giudiziarie che la vedono protagonista, ma specialmente per la storia della sua genesi e le implicazioni con l’avventurosa biografia del committente.

L’opera ha acquisito una certa notorietà quando nel 2019 ha oltrepassato il confine italiano per essere venduta all’asta a Vienna. Lo stesso era accaduto anche a un’altra opera della pittrice, la Lucrezia della collezione Jatta di Ruvo di Puglia, venduta dalla Dorhoteum, implicata anche nel commercio della Caritas. Due tele di Artemisia partite dalla Puglia e dirette in Austria, trasportate dalla stessa ditta con l’autorizzazione dello stesso Ufficio esportazioni e messe in vendita dalla medesima casa d’aste. Una serie di sospette coincidenze rilevate dalla Procura di Bari, nell’ambito di un’indagine dei carabinieri del Nucleo tutela patrimonio. I proprietari della Caritas, ereditata dall’ultimo discendente dei conti di Conversano Acquaviva d’Aragona, avevano ottenuto l’attestato di libera circolazione dichiarando un valore economico inferiore, celando il nome della Gentileschi e il legame documentato con contesti architettonici vincolati come le proprietà dei duchi di Conversano, dove la tela era stata custodita dalla metà del XVII secolo. Nell’Inventario del 1666 di Giangirolamo III figuravano quasi cinquecento quadri all’interno del castello, mentre un altro centinaio era sparso fra le residenze del nobile, tra cui “La Carita d’Armitia Gentilesca con cornice indorata”. Nell’attesa di ulteriori sviluppi, certamente interessanti sul piano del diritto dei beni culturali, ciò che si desidera fare in questa sede, è ricostruire le vicende storiche e artistiche legate alla committenza della Caritas e analizzarne gli aspetti formali, inserendola nel contesto della produzione contemporanea della Gentileschi. In un’ambientazione scura e appena accennata, un fioco raggio di luce da una finestrella illumina la scena: un anziano, dalla barba incolta e dal corpo asciutto, viene nutrito dal seno di una giovane donna, che guarda nella direzione opposta, oltre i confini della tela, per accertarsi di non essere scorta dal secondino. Il soggetto è il celebre exemplum di pietà filiale, tramandato per la prima volta nei Factorum et dictorum memorabilium di Valerio Massimo. Sicuramente Artemisia conosceva l’interpretazione caravaggesca del tema per le Sette opere di Misericordia, commissionata dal Pio Monte della Misericordia a Napoli, ma la sua versione sembra rifarsi alla composizione di analoga tematica di Bartolomeo Manfredi, caravaggista attivo a Roma dal 1609 al 1622, il quale ebbe particolare seguito, soprattutto tra i maestri fiamminghi attivi nell’Urbe, come Gerrit van Honthorst. Un fatto degno di nota è che Orazio Gentileschi a Londra lavorò per George Villiers, duca di Buckingham, presso la cui dimora ricevette anche ospitalità. Nel 1635, una Carità Romana è attestata nelle collezioni del duca e una missiva testimonia che la famiglia sabauda allora

Caritas Romana, or the Celebration of Feminine Virtue

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Caritas Romana is an intricate and compelling affair. Not so much for the judicial chronicles surrounding it, but especially for the story of its genesis and the implications with the adventurous biography of the commissioner.

The work gained notoriety when it crossed the Italian border to be sold at auction in Vienna in 2019. The same happened to another work by the painter, the Lucretia from the Jatta collection in Ruvo di Puglia, which was sold by Dorhoteum, also involved in the Caritas trade. Two canvases by Artemisia left Apulia and went to Austria, transported by the same company with the authorisation of the same Export Office and put up for sale by the same auction house. A series of suspected tangencies detected by the Bari Public Prosecutor’s Office, as part of an investigation by the Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Heritage. The owners of the Caritas, inherited by the last descendant of the Counts of Conversano Acquaviva d’Aragona, had obtained the certificate of free circulation by declaring a lower economic value, concealing Gentileschi’s name and the documented connection to such architecturally bound contexts as the properties of the Dukes of Conversano, where the painting had been kept since the mid-17th century. Giangirolamo III’s 1666 Inventory listed almost five hundred paintings inside the castle, while another hundred were scattered among the nobleman’s residences, including “La Carita d’Armitia Gentilesca con cornice indorata”. While awaiting further developments, which will certainly be interesting in terms of cultural heritage law, what we wish to do here is to reconstruct the historical and artistic events linked to the commissioning of the Caritas and analyse its formal aspects, placing it in the context of Gentileschi’s contemporary production.

In a dark and barely visible setting, a dim ray of light from a small window illuminates the scene: an old man, with an unkempt beard and a dry body, is being fed by the breast of a young woman, who looks in the opposite direction, beyond the confines of the canvas, to make sure she is not being escorted by the guard. The subject is the famous exemplum of filial piety, first recorded in Valerius Maximus’ Factorum et dictorum memorabilium. Artemisia was certainly familiar with Caravaggio’s interpretation of the theme for the Seven Works of Mercy, commissioned by the Pio Monte della Misericordia in Naples, but her version seems to be based on the composition of a similar theme by Bartolomeo Manfredi, a Caravaggist active in Rome from 1609 to 1622, who had a particular following, especially among the Flemish masters active in the Urbe, such as Gerrit van Honthorst. A remarkable fact is that Orazio Gentileschi in London worked for George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, at whose residence he also received hospitality. In 1635, a Caritas Romana is attested in the duke’s collections and a missive testifies that the Savoy family then

Le lettere di Artemisia

Asia Graziano

L’appendice riporta una breve selezione di lettere di Artemisia, significative per esemplificare al meglio, attraverso le sue stesse parole, alcuni caratteri peculiari della personalità e della produzione artistica della pittrice. Si è scelto di trascrive e commentare la lettera allo scienziato Galileo Galilei, una missiva del carteggio al committente e protettore romano Cassiano dal Pozzo e due lettere al mecenate Antonio Ruffo. Tali scritti, oltre al fascino dell’incontro diretto con il pensiero e la vita dell’artista narrata in prima persona, permettono, più di qualsiasi altra fonte, una chiara ricostruzione del profilo personale, artistico e professionale della Gentileschi. Artemisia chiedeva ostinata, pressante e quasi superba, protezione e aiuti a principi e importanti signori, ribadendo il proprio talento e il pregio di una carriera internazionale, condizioni in grado di favorirle nuove committenze e lauti guadagni. Non importa che tali lettere, diversamente da quelle indirizzate al Maringhi, siano dettate a scribi e segretari e non scritte di suo pugno, anzi. Ciò è ulteriore conferma del costante impegno artistico e professionale di Artemisia, che non si avvale solo di collaboratori pittori nell’atelier, ma anche di personale di segreteria. Le lettere che indirizza a committenti, signori e intellettuali dimostrano rapporti amicali profondi e duraturi nel tempo. La pittrice è franca con i suoi destinatari: esige cortesie, pretende favori e raccomandazioni. Nell’arco della sua carriera Artemisia fu capace di instaurare e mantenere contatti diretti con esponenti dell’élite culturale europea e con una clientela importante, inseguendo intercessioni, piazzando abilmente opere già eseguite, conquistando nuovi incarichi e compensi, vincendo più che ogni altra pittrice quel pregiudizio lamentato al Ruffo in una lettera del 30 gennaio del 1649 per cui “il nome di donna fa star in dubito sinché non si è visto l’opra”.

Artemisia’s Letters

Asia Graziano

The appendix contains a short selection of Artemisia’s letters, which are significant in exemplifying, through her own words, some of the distinctive features of the painter’s personality and artistic production. We have chosen to transcribe and comment on the letter to the scientist Galileo Galilei, a missive from the correspondence to the Roman patron and protector Cassiano dal Pozzo and two letters to the patron Antonio Ruffo. These writings, in addition to the fascination of the direct encounter with the artist’s thought and life narrated in the first person, allow, more than any other source, a clear reconstruction of Gentileschi’s personal, artistic and professional profile. Artemisia stubbornly, pressingly and almost haughtily requested protection and aid from princes and important lords, reaffirming her talent and the value of an international career, conditions that would favour her new commissions and lavish earnings. It does not matter that these letters, unlike those addressed to Maringhi, are dictated to scribes and secretaries and not written in her own hand, quite the contrary. This is further confirmation of Artemisia’s constant artistic and professional endeavours, as she did not only employ painterly collaborators in her atelier, but also secretarial staff. Artemisia’s letters to patrons, gentlemen and intellectuals demonstrate deep and lasting friendship. The painter is direct with her recipients: she demands courtesies, favours and recommendations. Throughout her career, Artemisia was able to establish and maintain direct contacts with members of the European cultural elite and with an important clientele, pursuing intercessions, skilfully placing works that had already been executed, winning new commissions and rewards, overcoming more than any other painter that prejudice complained of to Ruffo in a letter of 30 January 1649, according to which “the name of a woman makes one feel in doubt until one has seen the work”.

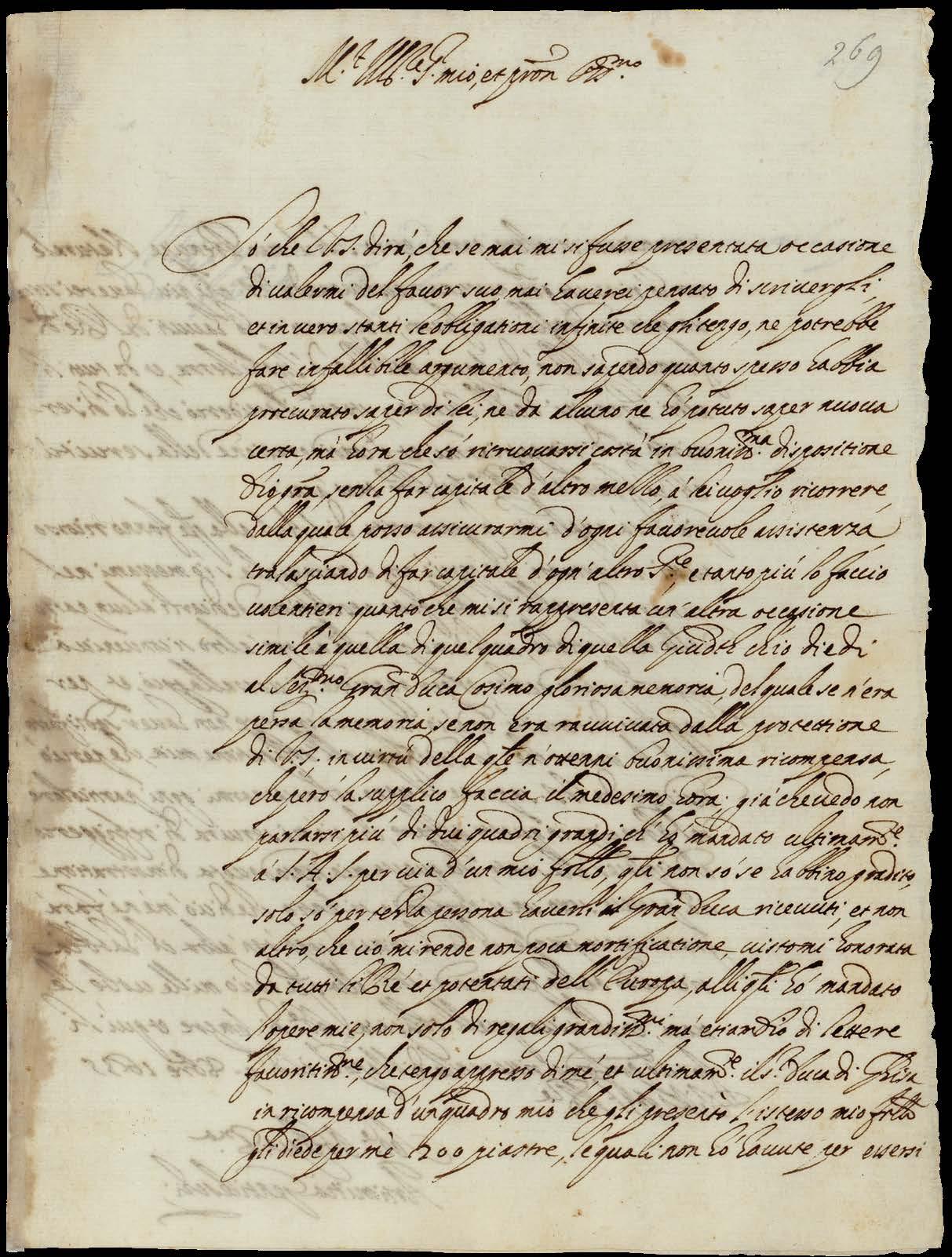

Artemisia Gentileschi a Galileo Galilei Napoli, 9 ottobre 1635

Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze, Manoscritti Galileiani 23, Gal. 23, cc. 269-270

Molto Illustre Signor mio et padron Osservandissimo, So che Vostra Signoria dirà che se mai mi si fusse presentata occasione di valermi del favor suo, mai haverei pensato di scrivergli, et invero stanti le obbligationi infinite che gli tengo, ne potrebbe fare infallibile argumento, non sapendo quanto spesso abbia procurato saper di lei, né da alcuno ne ho potuto saper nuova certa. Ma hora che so ritruovarsi costà in buonissima disposizione Dio gratia, senza far capitale d’altro mezzo, a lei voglio ricorrere dalla quale posso assicurarmi d’ogni favorevole assistenza,

(pp. 294, 297, 298, 301) Artemisia Gentileschi, Lettere a Galileo Galilei, Napoli, 9 ottobre 1635. Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze, Manoscritti Galileiani 23, Gal. 23, cc. 269-270.

Artemisia Gentileschi to Galileo Galilei Naples, 9 October 1635

Florence National Library, Manoscritti Galileiani 23, Gal. 23, ff. 269-270

Very Illustrious My Lord and Most Observant Master, I know that Your Lordship will say that if the occasion ever arose for me to avail myself of your favour, I would never have thought of writing to you, and indeed, given the infinite obligations that I hold to you, you could make a faultless argument about it, not knowing how often I have sought to know about you, nor have I been able to learn any certain news from anyone. But now that I know that you are in a very good situation Thank God, without making capital by any other means, I want to have recourse to you from whom I can be assured of every favourable assistance, omitting to make capital from

(pp. 294, 297, 298, 301) Artemisia Gentileschi Letter to Galileo Galilei, Naples, 9 October 1635. Florence National Library, Manoscritti Galileiani 23, Gal. 23, ff. 269-270.

Artemisia Gentileschi è stata oggetto di un’attenzione privilegiata negli ultimi decenni. Le ricerche a lei dedicate hanno però, spesso restituito un’immagine stereotipata e riduttiva dell’universo artistico e della personalità della pittrice. La figura professionale della Gentileschi, in grado di muoversi con grande successo in quello che oggi definiamo sistema dell’arte, trova finalmente inedita dignità. Nuove attribuzioni da collezioni private si affiancano ai capolavori della pittrice, ricostruendo il quadro delle committenze internazionali che l’hanno consacrata a protagonista del Barocco europeo, nel più completo e aggiornato volume dedicato all’artista. La carica innovativa del linguaggio e l’eccezionalità delle scelte iconografiche di Artemisia rivelano i documentati interessi e le frequentazioni letterarie, scientifiche e musicali che la pittrice ha sapientemente coltivato in ogni città che ne ha registrato il passaggio. / Artemisia Gentileschi has been the subject of much attention in recent decades. Research dedicated to her has, however, often returned a stereotyped and reductive image of the artistic universe and personality of the painter. The professional figure of Gentileschi, who was able to move with great success in what we now call the art system, finally finds new dignity. Unpublished attributions from private collections are flanked by the painter’s masterpieces, reconstructing the framework of the international commissions that consecrated her as a protagonist of the European Baroque, in the most complete and up-to-date volume dedicated to the artist. The innovative charge of language and the exceptional nature of Artemisia’s iconographic choices reveal the documented interests and literary, scientific and musical frequentations that the painter skilfully cultivated in every city that recorded her passage.

© Scripta Maneant Edizioni 2025

Il marchio Scripta Maneant è di proprietà di Scripta Maneant Group, Bologna, Italia.

The Scripta Maneant brand is owned by Scripta Maneant Group, Bologna, Italy.

Via dell’Arcoveggio, 74/2 | 40129 - Bologna - Italy | Tel. +39 051 223535

Numero verde / Toll-free Number 800 144 944 www.scriptamaneant.it | segreteria@scriptamaneant.it