4 Cobra 75

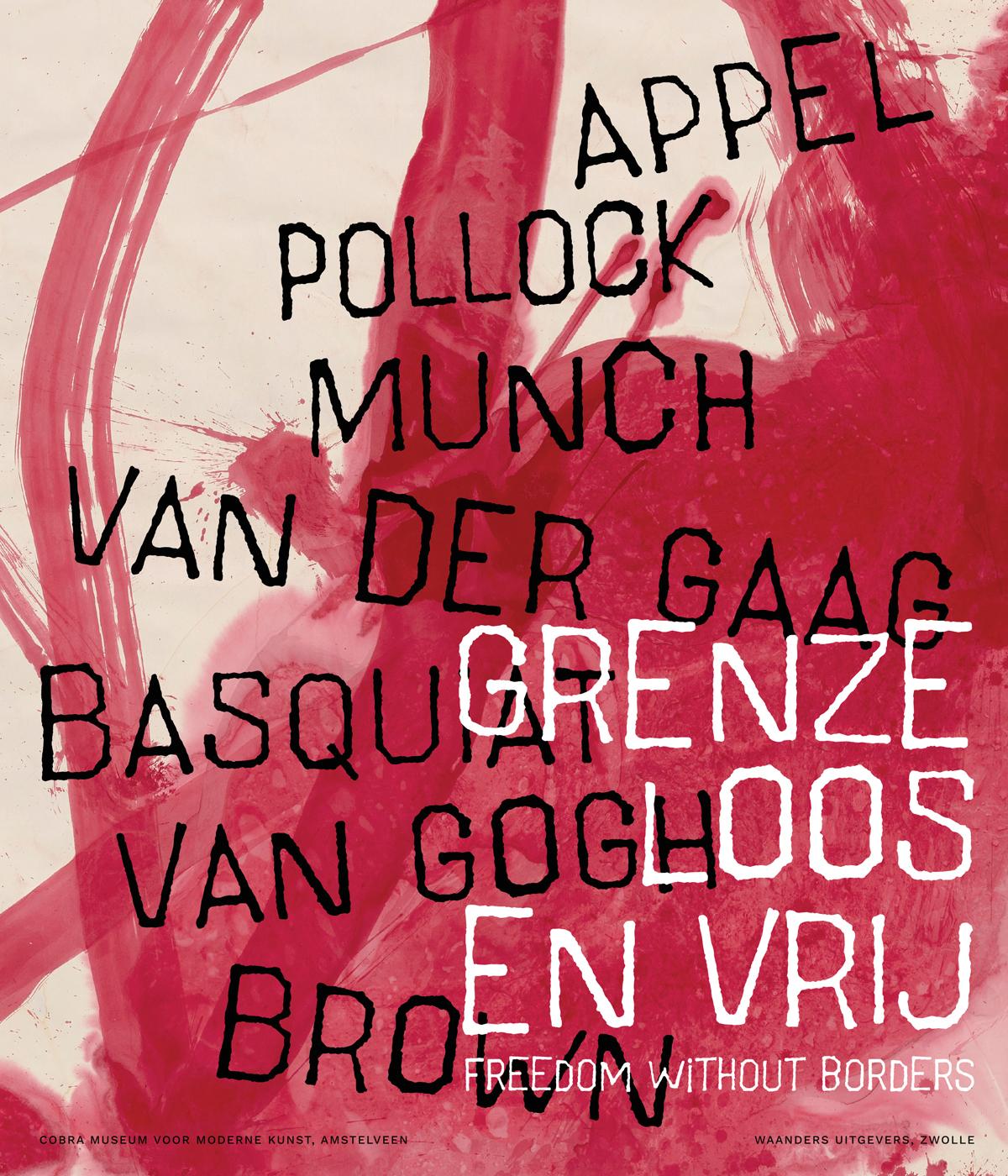

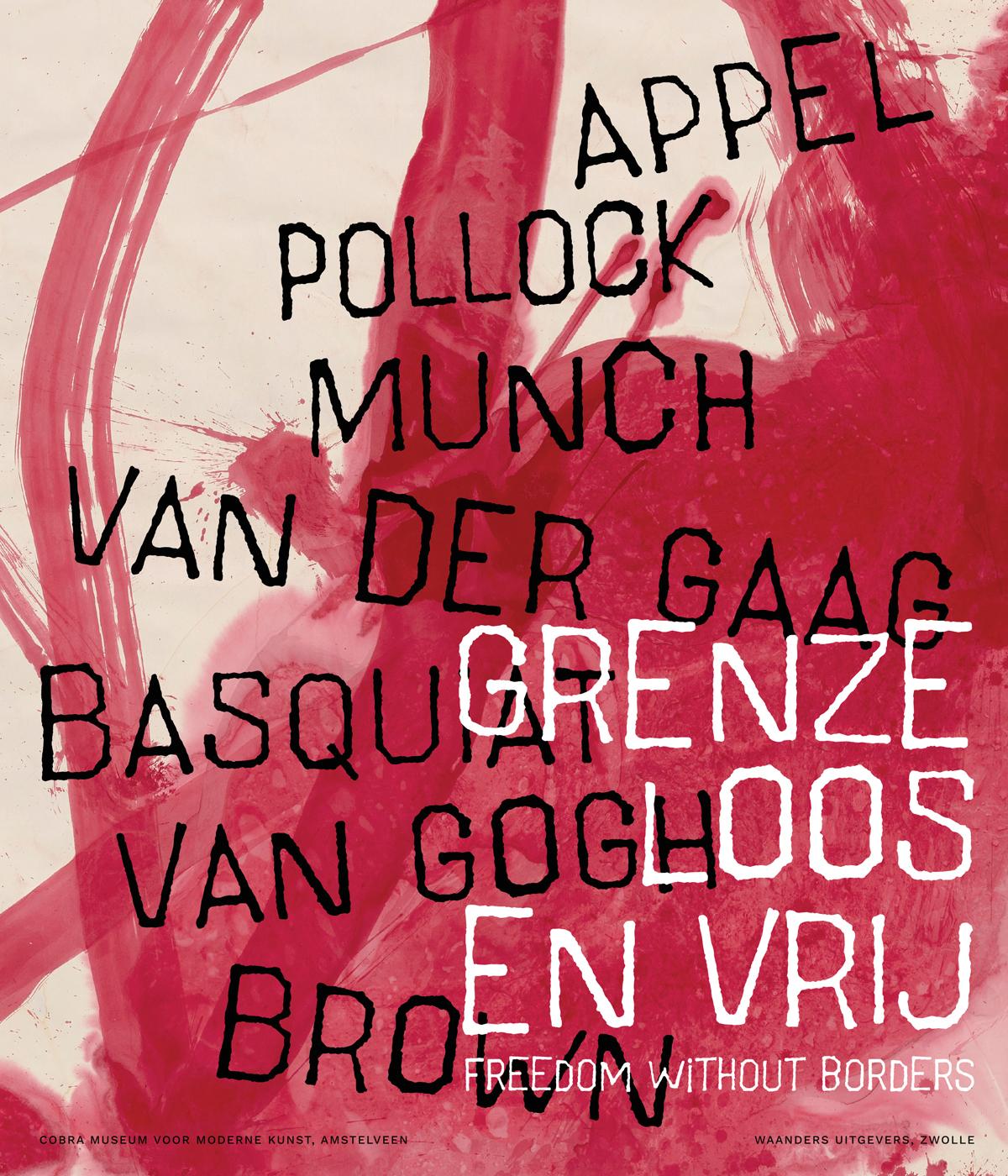

8 Grenzeloos en vrij | Freedom Without Borders

102 Het bezoek | The visit

112 Parijs: een voedingsbodem voor Cobra | Paris: A Breeding Ground for Cobra and Beyond

120 Lijst tentoongestelde werken | List of exhibited works

126 Noten | Notes

128 Colofon en fotoverantwoording | Colophon and photo credits

Cobra 75

In 2023 is het vijfenzeventig jaar geleden dat op 8 november 1948 Asger Jorn uit Denemarken, Christian Dotremont en Joseph Noiret uit België en Karel Appel, Corneille en Constant Nieuwenhuys uit Nederland in het café Notre-Dame in Parijs een kunstenaarsmanifest ondertekenden: de Cobra-beweging was geboren. Het was een pan-Europese, zelfs mondiale beweging met kunstenaars uit de voornoemde landen maar ook uit Frankrijk, Duitsland, het Verenigd Koninkrijk, Zweden, IJsland, Hongarije, Japan, Verenigde Staten en Zuid-Afrika.

In een reactie op de verschrikkingen en onderdrukking in de Tweede Wereldoorlog plaatsten zij de vrijheid en het denken over grenzen in het hart van hun manifest. Zij waren ervan overtuigd dat in ieder mens een kunstenaar schuilt en tot bloei komt, zolang er voldoende materiële middelen zijn om te overleven. Zij gaven de kunst van kinderen, van mensen met een neurodiverse achtergrond en van makers buiten Europa en de Verenigde Staten, een gelijke status als die van de Eurocentrische kunsthistorische canon. Experiment, spontaniteit en lef stonden hoog in het vaandel, alsook de kruisbestuiving tussen verschillende kunstvormen: beeldende kunst met muziek, met poëzie en literatuur en met architectuur bijvoorbeeld. Het jaar daarop, in 1949, werd in het Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, onder leiding van directeur Willem Sandberg, van 9 tot 28 november de eerste ruchtmakende tentoonstelling gehouden.

De Nederlandse schilder, acteur, regisseur en documentairemaker Jeroen Krabbé, die samen met Annefie van Itterzon ten tijde van deze tentoonstelling het belang van kinder-

In 2023, it will be seventy-five years since, on 8 November 1948, Asger Jorn from Denmark, Christian Dotremont and Joseph Noiret from Belgium and Karel Appel, Corneille and Constant Nieuwenhuys from the Netherlands signed an artists’ manifesto at the café Notre-Dame in Paris: the Cobra movement was born. It was a pan-European, in fact global, movement with artists from the above mentioned countries but also from France, Germany, the UK, Sweden, Iceland, Hungary, Japan, USA and South Africa.

In a reaction to the horrors and oppression of World War II, they placed freedom and thinking beyond borders, at the heart of their manifesto. They were convinced that there is an artist in every person and can flourish as long as there are sufficient material resources to survive. They gave the art of children, of people from neurodiverse backgrounds and of makers outside Europe and the United States, equal status with those of the Eurocentric art historical canon. Experimentation, spontaneity and boldness were highly valued, as was cross-pollination be-

tween different art forms: visual art with music, with poetry and literature and with architecture, for example. The following year, in 1949, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, led by director Willem Sandberg, hosted the first sensational exhibition from 9 to 28 November.

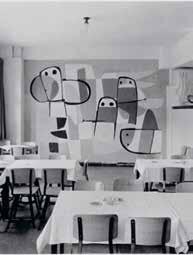

Dutch painter, actor, director and documentary filmmaker Jeroen Krabbé, who together with Annefie van Itterzon will highlight the importance of children’s drawings with two presentations at the time of this exhibition, remembers well how, as a five-year-old boy, his father took him to the exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum. His father published books on education in drawing, illustrated by drawings of the young Jeroen. The Dutch press completely dismissed the exhibition; this to the annoyance of father Krabbé, who particularly valued the great influence of children’s art on the Cobra artists. In 1949, when Appel had painted a mural in the canteen of the former Amsterdam City Hall (now Sofitel Legend The Grand Amsterdam), employees refused to eat there. Plans were made to repaint the mural and destroy the artwork. Krabbé vividly remembers going with his father to the City Hall where his father publicly denounced

tekeningen met twee presentaties benadrukt, herinnert zich goed hoe hij als vijfjarig jongentje door zijn vader werd meegenomen naar de tentoonstelling in het Stedelijk Museum. Zijn vader publiceerde boeken over tekenonderwijs, geïllustreerd met tekeningen van de jonge Jeroen. De Nederlandse pers kraakte de tentoonstelling volledig af; dit tot ergernis van vader Krabbé, die met name de grote invloed van kinderkunst op de Cobra-kunstenaars zeer hoog schatte. Toen Appel in 1949 een wandschildering in de kantine van het toenmalige Stadhuis van Amsterdam (tegenwoordig Sofitel Legend The Grand Amsterdam) had gemaakt, weigerden de ambtenaren om daar te eten. Er werden plannen gesmeed om de wandschildering over te schilderen en het kunstwerk te vernietigen. Krabbé herinnert zich levendig hoe hij met zijn vader naar het Stadhuis ging waar zijn vader met luide stem deze barbaarse plannen publiekelijk aan de kaak stelde. De wandschildering is toen afgedekt, maar nu weer als een van de schatten van het voormalig Stadhuis te zien. Het is een tekenend voorbeeld hoe heftig en verontwaardigd de reactie van de critici en het publiek op de experimentele Cobra-kunst was. De Cobra-beweging bestond drie jaar en eindigde met de tweede grote experimentele tentoonstelling in Luik in 1951, maar het gedachtegoed resoneert nog altijd door tot in de huidige tijd.

Het Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst Amstelveen is het enige museum in Nederland dat gewijd is aan het gedachtegoed van een internationale beweging met een manifest, de laatste in de 20ste eeuw. Dit gedachtegoed is nu net zo actueel als het in 1948 was: grenzeloos en vrij, verbindend en vooruitstrevend in een Europa, dat wordt bedreigd door oorlog, gesloten grenzen en isolatie.

Het Cobra75-jubileumjaar begon met een Deense drieluik; Wij kussen de aarde, Deense moderne kunst 1934-1948, Je est un autre, Ernest Mancoba & Sonja Ferlov en Becoming Ovartaci, alle drie tentoonstellingen een ware ontdekking en zelfs een verrassing voor de 25.000 bezoekers en media. In Wij kussen de aarde werd duidelijk hoe groot de invloed van de Deense kunstenaars, die tien tot vijftien jaar ouder waren dan de Nederlanders en Belgen, is geweest op de ontwikkeling en beeldentaal van de Cobra-beweging. De Deense beeldhouwer Sonja Ferlov en de Zuid-Afrikaanse beeldhouwer en schilder Ernest Mancoba waren niet alleen als echtpaar maar ook als artistiek koppel een unieke eenheid. Als leden van Høst, het Deense kunstenaarscollectief, maakten zij deel uit van de geboorte van de Cobra-

these barbaric plans. The mural was then covered, but can be seen again as one of the treasures of the former City Hall. It is a striking example of how fierce and dismaying the reaction of critics and the public was to Cobra experimental art. The Cobra movement existed three years and ended with a second major experimental exhibition in Liege in 1951, but its ideas still resonate today.

The Cobra Museum of Modern Art Amstelveen is the only museum in the Netherlands dedicated to the ideas of an international movement with a manifesto, the last in the 20th century. This ideology is as relevant today as it was in 1948: borderless and free, unifying and progressive in a Europe threatened by war, closed borders and isolation.

The Cobra75 anniversary year began with a Danish triptych; We kiss the earth, Danish modern art 1934-1948, Je est un autre, Ernest Mancoba & Sonja Ferlov and Becoming Ovartaci, all three exhibitions a real discovery and even a surprise for the 25,000 visitors and media. In We Kiss the Earth, it became clear how great an influence the Danish artists, who were a decade to 15 years older than the Dutch and Belgian artists, had on

the development and visual language of the Cobra movement. Danish sculptor Sonja Ferlov and South African sculptor and painter Ernest Mancoba were a unique pair not only as a married couple but also as an artistic union. As members of Høst, the Danish artists’ collective, they were part of the birth of the Cobra movement. Becoming Ovartaci movingly illustrated how the neurodiverse, transgender artist Ovartaci transformed her drive to be herself and longing for freedom into a stunning oeuvre. Asger Jorn deserves all the honours for discovering and persevering to draw attention to this artist.

The exhibition Freedom without Borders. From Appel to Basquiat places the Cobra artists in context. Among others, the late work of Vincent van Gogh and the works of Edvard Munch, Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee and Joan Miró, with their spontaneous, expressionist painting style, had a great influence on the Cobra artists. The Dutch artists, isolated during the occupation in World War II, visited exhibitions of these artists and others in Amsterdam, Denmark, Paris and Brussels after the liberation, and this opened their eyes. Also shown are contemporaries

beweging. Becoming Ovartaci illustreerde op ontroerende wijze hoe de neurodiverse, transgender kunstenaar Ovartaci haar drang naar zichzelf zijn en verlangen naar vrijheid omzette in een schitterend oeuvre. Jorn verdient alle honneurs voor zijn ontdekking en doorzettingsvermogen om aandacht voor deze kunstenaar te vragen.

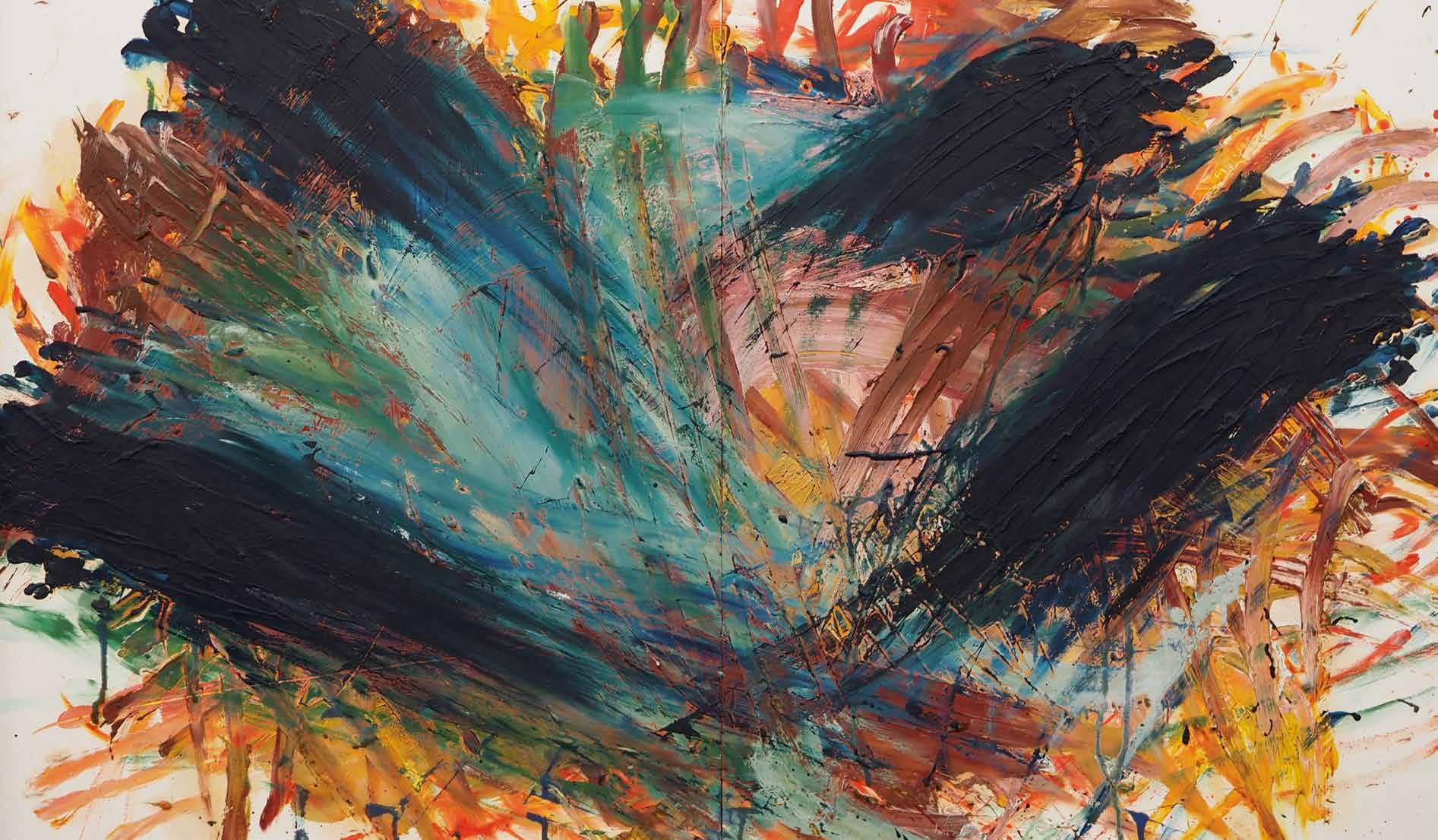

De tentoonstelling Grenzeloos en vrij, van Appel tot Basquiat plaatst de Cobra-kunstenaars in context. Onder anderen het late werk van Vincent van Gogh en de werken van Edvard Munch, Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee en Joan Miró hadden met hun spontane, expressionistische schilderstijl enorme invloed op de Cobra-kunstenaars. De Nederlandse kunstenaars, geïsoleerd tijdens de bezetting in de Tweede Wereldoorlog, bezochten na de bevrijding tentoonstellingen van deze en andere kunstenaars in Amsterdam, Denemarken, Parijs en Brussel en dat opende ook de ogen van de jonge Cobra-kunstenaars. Ook tijdgenoten worden getoond zoals Jean Dubuffet, de oprichter van de l’Art Brut Collection in Lausanne, en Jackson Pollock die het Amerikaanse abstract expressionisme vertegenwoordigt en later samen met de Cobrakunst onder de noemer Informele Kunst is gecategoriseerd. De spontane, expressieve manier van werken is nooit verdwenen met kunstenaars als Jean-Michel Basquiat, Cecily Brown en Arnulf Rainer. Het is een schitterende selectie werken uit nationale en internationale openbare en privécollecties, die de Cobra-kunstenaars plaatst samen met hun inspiratiebronnen en voorlopers, tijdgenoten en ‘navolgers’.

Tegelijkertijd tonen wij een exquise collectie werken van Pablo Picasso in De andere Picasso. Terug naar de bron ter gelegenheid van de sterfdag 50 jaar geleden, van een van de meest veelzijdige en invloedrijkste kunstenaars in de 20ste eeuw. Met werken op papier en keramiek uit Spaanse privé- en openbare collecties worden de Spaanse en mediterrane inspiratiebronnen voor Picasso getoond: literatuur, muziek, mythologie en natuurlijk ook zijn vader en schilder José Ruiz y Blasco. Het lijdt geen twijfel dat Picasso zijn schaduw werpt over veel kunstenaars waaronder ook de Cobra-kunstenaars. Terecht is er nu kritiek op het privéleven van de kunstenaar, met name over zijn ‘machismo’ en de soms schokkende manier waarop hij met vrouwen omging; wij besteden daar ook aandacht aan in onze programmering. Maar als kunstenaar staat zijn bijdrage aan de kunstgeschiedenis overeind, ondanks de bedenkelijke houding ten aanzien van vrouwen en zijn neiging om de ontwikkelingen bij

such as Jean Dubuffet, founder of the l’Art Brut Collection in Lausanne, and Jackson Pollock, who represented American abstract expressionism and was later categorised together with Cobra art under the heading Informal Art. The spontaneous, expressive way of working was never abandoned by artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Cecily Brown and Arnulf Rainer. A superb selection of works from national and international public and private collections, places the Cobra artists in the context of their inspirators and precursors, contemporaries and ‘followers’.

We are simultaneously showing an exquisite collection of works by Pablo Picasso in The Other Picasso. Back to the Origin to mark the 50th anniversary of the death of one of the most versatile and influential artists of the 20th century. With works on paper and ceramics from private and public collections, it showcases Picasso’s Spanish and Mediterranean inspirations: literature, music, mythology and, of course, his father and painter José Ruiz y Blasco. There is no doubt that Picasso has had a huge impact on many artists including the Cobra artists. Rightly, the artist’s private life is now criticised, especially his ‘machismo’ and the

sometimes upsetting way he treated women; we will pay attention to this in our programming. But as an artist, his contribution to art history stands firm, regardless of his questionable attitudes towards his partners and other women, and his tendency to quickly incorporate other artists’ developments into his own work. We thank the guest curators Helena Alonso and J. Óscar Carrascosa from Malaga, Spain, and Alex Susanna director of Expona from Bolsano, Italy, very much for making this exhibition happen.

Guest curator Maarten Bertheux is praised for his thorough and time-consuming research for this anniversary exhibition. Likewise, we are grateful for the generosity of the many lenders and artists.

With great thanks to sponsors Zabawas, Blockbuster Fund and the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, and our loayal partners municipality of Amstelveen, VriendenLoterij, our Founders Trebbe, BPD, Rabobank Amstel & Vecht and HIZKIA, our paint sponsor KEIM and the Cobra Business Club.

andere kunstenaars snel in zijn eigen werk in te lijven. Wij danken de gastconservatoren Helena Alonso en J. Óscar Carrascosa uit Malaga, Spanje, en Alex Susanna directeur van Expona uit Bolsano, Italië, zeer voor de totstandkoming van deze tentoonstelling.

De gastconservator Maarten Bertheux verdient alle lof voor zijn grondige en tijdrovende onderzoek voor de jubileumtentoonstelling. Ook zijn wij dankbaar voor de generositeit van de vele (particuliere) bruikleengevers en kunstenaars. Speciale dank aan de Fondation Constant, Appel Foundation en Tajiri Ferdi Foundation.

Met grote dank aan de sponsoren Zabawas, Blockbusterfonds en Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed en onze vaste partners Gemeente Amstelveen, VriendenLoterij, onze Founders Trebbe, BPD, Rabobank Amstel & Vecht en HIZKIA, onze verfsponsor KEIM en de Cobra Business Club.

Ten slotte, alleen met de enorme inzet van mijn collega’s is het mogelijk om deze projecten te realiseren, waarvoor mijn grote dank!

Stefan van Raay, Directeur | Director Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst Amstelveen

Finally, only with the immense commitment of my colleagues it is possible to realise these projects, for which my profound thanks!

Tentoonstelling | Exhibition

Gastconservator | Guest Curator

Maarten Bertheux

Projectleider | Project manager

Marieke van Zuilichem

Collectiebeheer| Collection management

Maxim de Nooij

Assistent Collectiebeheer | Assistant Collection management Rikkert Beek, Niels Vis, Martine Schäfer (Stagiaire)

Redactie | Editing

Esther van den Berg, Marieke van Zuilichem

Tentoonstellingsontwerp | Exhibition design Zsa Zsa Tuffy, Daphne Heemskerk

Tentoonstellingsopbouw | Exhibition installation

Guido Jelsma, Stefan Mirck & team

PR & Communicatie | PR & Communication

Sandra van Dongen, Anna Wiersma, Tanje van Lingen, Maarten Jeukens, Elske Schreurs

Fondsenwerving | Fund-raising Jeroen Bakker

Cobra en het modernisme

De Cobra-beweging is op 8 november 1948 opgericht. Het bestaan van Cobra was kort: slechts drie jaar (1948-1951). Na vijfenzeventig jaar kan de vraag gesteld worden: wat heeft Cobra betekend? Zeker in het begin heeft de beweging voor de nodige opschudding gezorgd. Binnen de naoorlogse situaties in Nederland, Denemarken, België, maar ook in veel andere Europese landen bleek het provocatieve karakter van Cobra een krachtig antwoord op de voornamelijk behoudende cultuur van na de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Maar hoe lang leefde het gedachtengoed voort? Werkte het provocatieve en bevrijdende karakter later nog steeds? Of zou Cobra toch vooral een kunstenaarsbeweging blijken te zijn met individuele kunstenaars die vernieuwing zochten in expressieve en bevrijdende beelden? De werken van Cobra-kunstenaars getuigen in ieder geval van de nieuwe energie die in hun tijd nodig was om de zaak op te schudden.

In de tentoonstelling Grenzeloos en vrij is te zien dat het werk van de Cobra-kunstenaars niet losstaat van wat er voor, tijdens en na Cobra is gemaakt. Ook andere kunstenaars creëerden nieuwe inzichten die veel gemeen hebben met de vernieuwingsdrang van Cobra. Deze tentoonstelling is geen polemische verhandeling over het gedachtengoed van Cobra, maar laat vooral de parallellen en verschillen met andere uitingen zien. Ze toont niet alleen individuele ontwikkelingen van kunstenaars, maar vertelt ook hoe grillig kunst steeds opnieuw reageert en anticipeert op nieuwe omstandigheden.

Terugkijkend op de afgelopen vijfenzeventig jaar hebben zich binnen de kunst veel veranderingen voorgedaan. Modernistische stromingen rekenden af met voorafgaande bewegingen; lange tijd was vooruitgang het credo. Het leek alsof de kunst zich ontwikkelde langs logische en doorlopende lijnen die liepen van Paul Cézanne (1939-1906) via het kubisme naar de abstracte composities van Piet Mondriaan (1872-1944) en Kazimir Malevitsj (1879-1935) en het minimalisme van de jaren

Door | By Maarten Bertheux

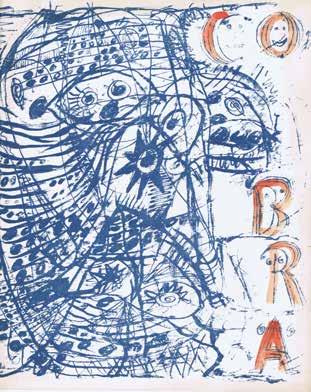

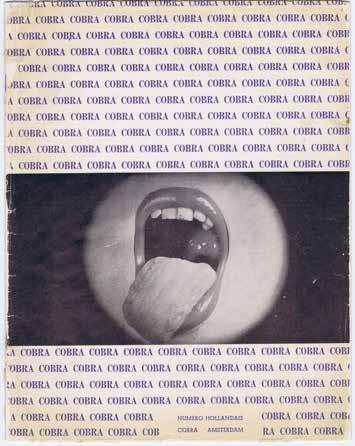

Asger Jorn, Egil Jacobsen, CarlHenning Pedersen, kleurenlitho | lithography, omslag | cover nr. 1 Cobra, 1948, Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen

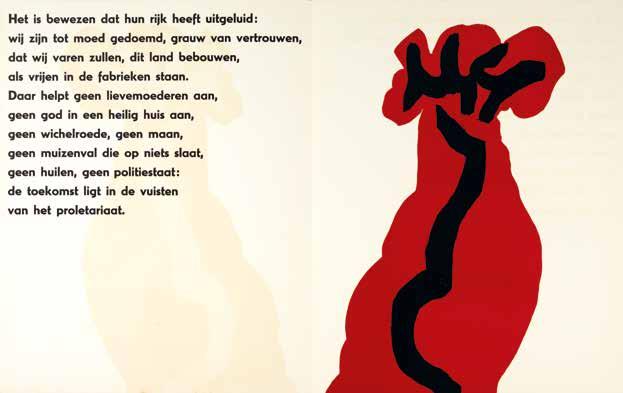

Constant & tekst | text Jan Elburg (1919-1992), Portfolio Het Uitzicht van de Duif-09 (The Dove’s View), 1952 ©Constant / Fondation Constant

Cobra and modernism

The Cobra movement was founded on November 8, 1948. Cobra’s existence was short: just three years (1948-1951). Seventy-five years after the movement, we can now ask the question: what has been the impact of Cobra? Certainly, in its beginning, the movement caused a stir within post-war Netherlands, Denmark, and Belgium, as well as many other European countries. Cobra’s provocative character proved to be a powerful response to the mainly conservative post-World War II culture. But how long did these ideas live on? Did its provocative and liberating character of Cobra continue to have an impact? Or would Cobra ultimately prove to be, primarily, a movement of individual artists who sought innovation in expressive and liberating images? In any case, the works of Cobra artists testify to the new energy needed to shake things up during their time.

The exhibition Freedom Without Borders reveals that the work of Cobra artists is not separate from what was made before, during, or after Cobra. Other artists beyond Cobra also created new insights that had much in common with Cobra’s similar drive for innovation. This exhibition is not a polemical treatise on Cobra’s ideas, but rather shows the parallels and differences it has with other expressions. The exhibition not only shows individual developments made by artists, but also tells how capriciously art constantly reacts and anticipates new circumstances.

Looking back over the past seventy-five years, many changes have occurred within art. Modernist movements did away with prior movements; for a long time, progress was the credo. It seemed that art developed along logical and continuous lines that ran from Paul Cézanne (1939-1906) through Cubism, to the abstract compositions of Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), Kazimir Malevich (18791935) and the minimalism of the 1960s in the twentieth century; or from Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) through the expressionism of Die Brücke (1905-1913) and Der Blaue Reiter (1911-1914), ephemeral movements in the visual arts, formed

zestig in de twintigste eeuw; of van Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) en Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) via het expressionisme van kortstondige bewegingen in de beeldende kunst zoals Die Brücke (19051913) en Der Blaue Reiter (1911-1914), gevormd door expressionistische kunstenaars in Duitsland, tot aan hedendaagse vormen van expressionisme zoals die van Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988). De invloedrijke criticus Clement Greenberg formuleerde in de jaren zestig hoe de schilderkunst zich steeds verder ontwikkelde in de richting van een nadrukkelijk plat vlak, gevuld met abstracte, voornamelijk monochrome vlakken en lijnen. Hij beschouwde de uitgesproken kleur, open vorm en vlakke compositie als de enige weg naar hoge picturale kunst in de nabije toekomst.1 Dit streven naar objectivering en abstractie leidde ertoe dat alleen concrete kleuren en vormen de inhoud van een werk zouden bepalen. Via het proces van reductie, met een nadruk op de concrete beeldelementen, zou ook de Minimal Art zijn ‘pure’ betekenis formuleren. Deze ontwikkeling stond haaks op de kleurige schilderijen met vogels, schreeuwende figuren en kinderlijke eenvoud die de Cobrakunstenaars hebben voortgebracht. Maar ook op de dwangbuis van het minimalisme zou een reactie volgen. Die reactie, die later postmodernisme werd genoemd, begon rond 1970 en liet alles weer toe, zoals een herkenbare voorstelling en het mixen van oude en nieuwe beelden, of van kitscherige of triviale met hoogstaande elementen. Met het wegvallen van een onderscheid tussen ‘high and low culture’ ontstond ook een nieuwe vrijheid. ‘Anything goes’ kwam in de plaats voor de utopische maar beperkende gedachten van vooruitgang. Deze ontwikkeling viel bovendien samen met een toenemende mondialisering waarin de westerse canon steeds minder maatgevend leek te worden. Vanaf dat moment werden in de kunst zelden nog proclamaties of manifesten geformuleerd voor nieuwe (lees: moderne) bewegingen en werd het verwerpen van het voorgaande zinloos. De beeldenstrijd om het voorafgaande te vervangen door alternatieven was voorbij.

Dat idee van vooruitgang en van het maken van vrije, compromisloze kunstwerken bestond nog wel bij de kunstenaars die op 8 november 1948 in Parijs de Cobra-beweging startten. De naamgeving Cobra kwam van de dichter Christian Dotremont (1922-1979) en is een acroniem voor (K)Copenhagen, Brussel en Amsterdam, de drie steden waar de jonge experimentele kunstenaars na de Tweede Wereldoorlog werkten. Op 5, 6 en 7 oktober 1948 troffen zij elkaar op een conferentie met voornamelijk Franse en Belgische revolutionaire surrealisten

by expressionist artists in Germany, to contemporary forms of expressionism such as that of Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988). The influential critic Clement Greenberg formulated in the 1960s how painting continued to move toward an emphatically flat plane, filled with abstract, mostly monochromatic planes and lines. He considered the distinct colour, open form and flat composition to be the only path to high pictorial art in the near future.1 This pursuit of objectification and abstraction led to the idea that only concrete colours and shapes would determine the content of a work. Through the process of reduction, with an emphasis on the concrete pictorial elements, Minimal Art would also formulate its “pure” meaning. This development was at odds with the colourful paintings with birds, screaming figures, and childlike simplicity produced by the Cobra artists. But even the straitjacket of minimalism would be met with a reaction. That reaction, later called postmodernism, began around 1970 and allowed for everything again, such as recognizable representation and the mixing of old and new images, or of kitschy or trivial with high-minded elements. With the elimination of a distinction between “high and low culture,” a new freedom also emerged. ‘Anything goes’ replaced utopian but restrictive thoughts of

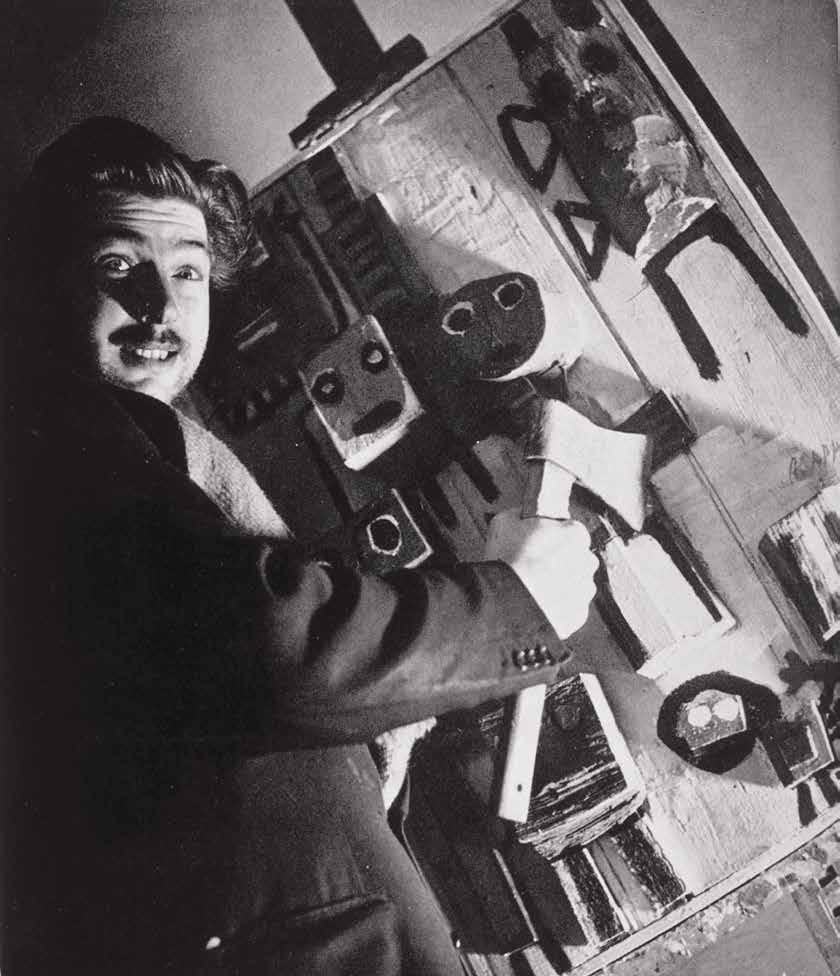

Karel Appel met bijl poserend voor Vragende Kinderen | with axe posing for Questioning Children (1949). Foto | Photo: E. Kokkoris-Syrier

progress. Moreover, this development coincided with an increasing globalization in which the Western canon seemed to become less and less normative. From then on, proclamations or manifestos for new (read: modern) movements were rarely formulated in art, and the rejection of the preceding became meaningless. The battle of images to replace the prior with alternatives was over.

That idea of progress and of making free, uncompromising works of art still existed among the artists who started the Cobra movement in Paris on November 8, 1948. The name Cobra came from the poet Christian Dotremont (1922-1979) and is an acronym for Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam, the three cities where the young experimental artists worked after World War II. On 5, 6, and 7 October 1948, the artists met at a conference with mostly French and Belgian revolutionary surrealists under the title ‘Conference du Centre International de Documentation sur l’Art d’Avant-Garde’. Here, the discussions were mainly theoretical - which was particularly disliked by the Danish, Dutch, and (some) Belgian participants. Furthermore, the surrealist artists,

onder de titel ‘Conference du Centre International de Documentation sur l’Art d’Avant-Garde’. Hier werd vooral theoretisch gediscussieerd – wat met name de Deense, Nederlandse en (sommige) Belgische deelnemers minder goed beviel. Verder maakten de surrealistische kunstenaars, bij monde van André Breton (1896-1966), bezwaar tegen de in hun ogen politieke, c.q. communistische intenties van Dotremont.

Hierop besloten de Deense dichter-schilder Asger Jorn (1914-1973), de Belgen Dotremont en Joseph Noiret (1927-2012) en de Nederlanders Karel Appel (1921-2006), Corneille (1922-2010) en Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920-2005) een eigen weg in te slaan. In hun eigen manifest verklaarden zij dat ze een gemeenschappelijk leef-, werk- en denkklimaat hadden gevonden. Hun plannen werden vooral beschreven en geïllustreerd in hun eigen tijdschrift met dezelfde naam: Cobra. Dotremont trachtte samen met Jorn ook andere kunstenaars te vinden die een experimentele koers waren ingeslagen die ver van het klassieke surrealisme zou staan.

In Nederland bestond die wil tot vernieuwing al toen Constant samen met Appel en Corneille de Experimentele Groep had opgericht. Tijdens de officiële oprichtingsvergadering op 16 juli 1948 zouden meerdere kunstenaars zich aansluiten. Naast Constant, Corneille en Appel waren dat Anton Rooskens (1906-1976), Theo Wolvecamp (1925-1992), Jan Nieuwenhuijs (19221986) en Eugène Brands (1913-2002). Enkele maanden later volgden de beeldhouwer Shinkichi Tajiri (1923-2009) en de dichters Jan Elburg (1919-1992), Gerrit Kouwenaar 1923-2014) en Lucebert (1924-1994). Volgens de uitgangspunten (omschreven in Reflex, het tijdschrift van de Experimentele Groep) zouden deze rebelse kunstenaars de strijd aangaan met de oude esthetische opvattingen die de nieuwe creativiteit in de weg stond. Constant, die de meeste theoretische bijdragen leverde, pleitte voor ‘een nieuw soort volkskunst’. ‘Een volkskunst echter is niet een kunst die aan door het volk gestelde normen beantwoordt […] Maar een volkskunst is die uiting van het leven, die uitsluitend gevoed wordt door een natuurlijke en daardoor al-

Cobra redactie vergadering in het atelier van | Cobra editing team in the atelier of Jean- Michel Atlan, Parijs | Paris c. 1950. V.l.n.r. | F.l.t.r. Doucet, Constant, Dotremont, Denise Atlan, Atlan, Corneille, Appel. Aan de muur tekening van Atlan | On the wall drawing by Atlan

De Experimentele

Groep Holland (1948), zittend v.l.n.r. | seated f.l.t.r. Wolvecamp, Corneille, Constant, Nieuwenhuijs, Brands, Rooskens; staand | standing Appel, Elburg, Kouwenaar

Constant stond al langer in contact met experimentele groepen in Frankrijk en Denemarken. Bij deze groepen groeide het besef dat er

led by André Breton (1896-1966), objected to what they saw as Dotremont’s political and/or communist intentions.

Following this, the Danish poet-painter Asger Jorn (1914-1973), the Belgians Dotremont and Joseph Noiret (1927-2012), and the Dutchmen Karel Appel (1921-2006), Corneille (1922-2010) and Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920-2005), decided to go their own way. In their own manifesto, they declared that they had found a common living, working, and thinking environment. Their plans were mainly described and illustrated in their magazine of the same name: Cobra. Together with Jorn, Dotremont also tried to find other artists who had embarked on an experimental course that would be far from classical surrealism.

In the Netherlands, this will to innovate already existed when Constant, together with Appel and Corneille, founded the Experimental Group. At the official founding meeting on July 16, 1948, several artists would join. Besides Constant, Corneille, and Appel, attending were Anton Rooskens (1906-1976), Theo Wolvecamp (1925-1992), Jan Nieuwenhuijs (1922-1986), and Eugène Brands (1913gemene drang naar levensexpressie. Een kunst […] die geen andere norm erkent dan expressiviteit, en spontaan schept wat de intuïtie ingeeft.’2 Om die vernieuwing te bereiken, maakte de groep experimentele kunstenaars gebruik van vormen van expressie die buiten de officiële kunst te vinden waren. Zij vonden die bijvoorbeeld in de onbelemmerde manier van uiten in kindertekeningen of in de zogenoemd ‘primitieve’ vormen in volkskunst die zowel in Europa als ver daarbuiten te vinden was en in de uitingen van geesteszieke personen. Constant stelde in zijn Manifest dat creativiteit geen privilege is van ‘begenadigde kunstenaars’. Hij wilde geen beperkingen en concludeerde: ‘Een schilderij is niet een bouwsel van kleuren en lijnen, maar een dier, een nacht, een schreeuw, een mens of dat alles samen.’3

Jorgen Roos & Wilhelm Freddie, fotomontage | photo montage, omslag | cover Cobra nr. 4, Amsterdam, 1949. Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen

een internationale bundeling van krachten nodig was om die doelstellingen te bereiken. In Denemarken hadden meerdere kunstenaars, zoals Else Alfelt (1910-1974), Ejler Bille (1910200), Henry Heerup (1907-1993), Egill Jacobsen (1910-1998), Carl-Henning Pedersen (1913-2007), Richard Mortensen (1910-1993) en Jorn tussen 1941 en 1945 bijgedragen aan het blad Helhesten (Het Hellepaard). Zij verzetten zich tegen de traditionele opvattingen over kunst en kozen, in tegenstelling tot de serieuze en op het individualisme georiënteerde kunst, juist voor een rauwe, ongepolijste of absurdistische benadering. Ook zochten ze naar manieren van samenwerken. In hun schilderen werden zij naast door het surrealisme – dat voor de oorlog in Europa nog dominant was – beïnvloed door het Duitse expressionisme en een schilder als Edvard Munch (18631944). In hun thematiek werden zij vooral geïnspireerd door de Noordse mythen en sagen, vol demonen en hybride dier- mensfiguren, en door de ‘primitieve’ kunst van Scandinavische landen. Het was in feite een romantisch streven naar de oorsprong van het leven en de natuurlijkste expressie die daarmee verbonden was. In hun onorthodoxe stellingname en hun streven naar een humanere samenleving verzetten zij zich ook tegen de opgelegde cultuuropvattingen van de Duitse bezetters tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog.

De eerste tentoonstellingen en het tijdschrift Cobra

In hetzelfde jaar van de oprichting van de Experimentele Groep raakten Appel, Constant en Corneille, samen met Dotremont en Jorn, betrokken bij de oprichting van Cobra. Daarna lijken de gebeurtenissen zich razendsnel te voltrekken. In de maand van de oprichting vertrokken zij, met in hun bagage enkele van hun schilderijen, naar Denemarken om deel te nemen aan een tentoonstelling in Kopenhagen. Zij werden gastvrij ontvangen en enthousiast bij het zien van zoveel geestverwant werk. Het werk van de drie Nederlanders werd eind november opgenomen in de tentoonstelling van de Deense kunstenaarsvereniging Høst.

In november 1949 volgde een tentoonstelling in het Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, die later een legendarisch moment zou blijken in de korte geschiedenis van Cobra. Directeur Willem Sandberg ging positief in op het verzoek van de groep voor een tentoonstelling die de naam Exposition Internationale d’Art Expérimental kreeg. De naam Cobra werd nog vermeden en de organisatoren benadrukten vooral het internationale karakter van de tentoonstelling, met

2002). Sculptor Shinkichi Tajiri (1923-2009) and poets Jan Elburg (1919-1992), Gerrit Kouwenaar 1923-2014), and Lucebert (1924-1994) followed a few months later. According to the principles described in Reflex, the magazine of the Experimental Group, these rebellious artists would fight the old aesthetic views that stood in the way of new creativity. Constant, who made most of the group’s theoretical contributions, advocated ‘a new kind of folk art’. ‘A folk art, however, is not an art that conforms to standards set by the people [...] But a folk art is that expression of life which is nourished exclusively by a natural and therefore general urge for the expression of life. An art [...] that recognises no norm other than expressiveness, and spontaneously creates what intuition inspires.’2 To achieve this innovation, the group of experimental artists used forms of expression that could be found outside official art. They found these, for example, in the unimpeded mode of expression found in children’s drawings, or in the so-called ‘primitive’ forms in folk art found both in Europe and far beyond, as well as in the expressions of mentally ill individuals. In his Manifesto, Constant argued that creativity was not a privilege of ‘gifted artists’. He wanted no restrictions. He said, in conclusion, that, ‘A painting is not an edifice

Cobra-kunstenaars brengen hun werk naar het | Cobra artists bring their work to the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (Exposition Internationale d’Art Expérimental), 1949 Foto | Photo: E. KokkorrisSyrier

of colours and lines, but an animal, a night, a scream, a human being, or all of these together.’3

For some time, Constant had been in contact with experimental groups in France and Denmark. Among these groups was a growing awareness that an international joining of forces was necessary to achieve their goals. In Denmark, several artists such as Else Alfelt (1910-1974), Ejler Bille (1910-200), Henry Heerup (1907-1993), Egill Jacobsen (1910-1998), Carl-Henning Pedersen (1913-2007), Richard Mortensen (1910-1993), and Jorn had contributed to the magazine Helhesten (The Hellhorse) between 1941 and 1945. They opposed traditional conceptions of art and, in contrast to serious and individualism-oriented art, opted instead for a raw, unpolished, or absurdist approach. They also sought ways of working together. In their paintings, besides being influenced by surrealism - which was still dominant in Europe before the war - they were influenced by German expressionism and painters like Edvard Munch (18631944). In their subject matter, they were mainly inspired by Nordic myths and sagas which were full of demons and hybrid animalhuman figures, and by the ‘primitive’ art of Scandinavian countries.

It was basically a romantic pursuit of the origins of life and the most natural expression associated with it. In their unorthodox stance and pursuit of a more humane society, they also resisted the imposed cultural views of the German occupiers during World War II.

In the same year the Experimental Group was established, Appel, Constant, and Corneille, together with Dotremont and Jorn, became involved in the formation of Cobra. After that, events seemed to unfold at lightning speed. Withing the first month after Cobra’s founding, the artists left for Denmark, carrying in their luggage some of their paintings, to participate in an exhibition in Copenhagen. They were hospitably received and were also thrilled to see so much kindred work in the exhibition. In late November, the work of the three Dutchmen was included in the exhibition of the Danish artists’ association Høst.

An exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam followed in November 1949, which would later prove to be a legendary moment in Cobra’s short history. Director Willem Sandberg

responded positively to the group’s request to create an exhibition called Exposition Internationale d’Art Expérimental. At the time, the name Cobra was still avoided, and the organisers particularly emphasised the international nature of the exhibition, with artists from the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Belgium, France, Britain, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. For many of these young artists, it was the first time they could present their work within the walls of a respected museum. The exhibition design was created by the architect Aldo van Eyck (1918-1999), who knew some members of the group and encouraged a number of the artists to create extremely large canvases on site in addition to paintings of relatively small size. Some of these canvases are still in presentable condition, including Downward Drift II by Brands, which is now on display in Freedom Without Borders.

A lecture evening was scheduled at the Stedelijk Museum on November 5th, during which Dotremont read his long manifesto Le Grand rendez-vous naturel in French. Partly because most of those present did not have a good command of French, while many others disagreed with Dotremont’s left-political narrative, skirmishes

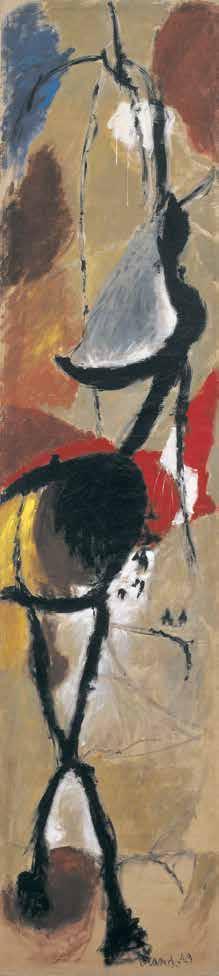

kunstenaars uit Nederland, Denemarken, Zweden, België, Frankrijk, Groot-Brittannië, Polen en Tsjecho-Slowakije. Het was voor veel van deze jonge kunstenaars de eerste keer dat zij hun werk binnen de muren van een gerespecteerd museum konden presenteren. De inrichting werd gedaan door de architect Aldo van Eyck (1918-1999) die enkele leden van de groep kende en een aantal kunstenaars aanmoedigde om naast schilderijen van relatief klein formaat, ter plekke een aantal extreem grote doeken te maken. Enkele daarvan zijn nog in toonbare conditie, waaronder Neergeschreven drift II van Brands dat nu in Grenzeloos en vrij te zien is.

Op 5 november stond er een voordrachtsavond in het Stedelijk Museum gepland waar Dotremont zijn lange manifest Le Grand rendez-vous naturel in het Frans voorlas. Mede omdat het merendeel van de aanwezigen het Frans niet goed beheerste en velen het oneens waren met het links-politieke verhaal van Dotremont, ontstonden er schermutselingen tussen kunstenaars en publiek. Het werd zelfs sommige Cobra-leden te veel en zij verlieten de groep. De uit de hand gelopen situatie moest uiteindelijk door de politie worden beëindigd. De rel werd de volgende dag breed in de kranten uitgemeten. Voor een deel droeg dat bij aan de mythische betekenis die de op dat moment nog kleine en onbekende Cobra-beweging zou krijgen. Na de tentoonstelling in Amsterdam volgde nog een kleine tentoonstelling in een Brusselse galerie en ten slotte, in 1951, een laatste tentoonstelling in het Musée Royal des Beaux-Arts in Luik. Dat was het jaar waarin Cobra zichzelf alweer had opgeheven.

In Cobra No 7 (1950, Brussel) beschrijft Dotremont hoe Cobra zich onderscheidde van andere modernistische bewegingen door mensen, zonder onderscheid en inclusief hun verschillen, bij elkaar te brengen.4 In een later artikel noemt Dotremont Cobra een manier van leven, een reële utopie die hij omschrijft als ‘de interactie van het individu en de gemeenschap, de

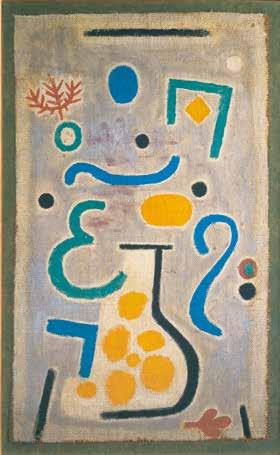

Paul Klee, die Vase (de vaas | The Vase), 1938, 122 (J2) Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

samenwerking tussen verschillende specialismen (schilderkunst, poëzie, etc.), de samenwerking tussen verschillende landen en van verschillende tijden […], van het verleden en het heden, de imaginaire tijd en verschillende tijdsgewrichten […] en de interactie tussen kunst en leven.’5

Dergelijke hooggestemde idealen bestonden vooral bij de meer theoretisch geïnteresseerde leden zoals Dotremont, Jorn en Constant; het is de vraag wat er van deze hooggespannen idealen is uitgekomen. Allereerst moet worden vastgesteld dat voor de meeste leden het maken van een gedicht of een schilderij voorop stond. Zij gaven vorm aan een vrije, spontane creatie en zochten elkaar op. Er bestond een algehele wil om te ontsnappen aan het benepen en traditionele klimaat van na de oorlog – maar niet in elk land werden de uitingen van de Cobra-leden begrepen en er was nog veel weerstand tegen deze nieuwlichters.

De tentoonstelling Grenzeloos en vrij beoogt geen historische terugblik of reflectie op typische kenmerken van Cobra-kunst te zijn. Het plaatst het werk van Cobra-kunstenaars in een bredere context. De Cobrakunstenaars wilden hun ideeën met anderen delen en zochten tot de verste (Europese) uithoeken contact met gelijkgestemden. Alle kunst die stond voor experimenteel, speels, provocatief en vrij kon rekenen op respons van de grondleggers van de beweging.

Door de kunstwerken van Cobra naast die van andere, niet aan Cobra gelinkte kunstenaars te plaatsen, ontstaan nieuwe dwarsverbanden. In een retrospectief van zo’n vijfenzeventig jaar wordt bovendien duidelijk dat er eigenlijk al vanaf het begin grote verschillen waren tussen de individuele Cobra-kunstenaars. Ook is ieders artistieke ontwikkeling totaal verschillend verlopen. Terugkijkend kan bovendien een voorlopige balans

ensued between the artists and audience. This was too much for some Cobra members, and they left the group. The situation got so out-of-control that it needed to be ended by the police. The riot was widely reported in the newspapers the next day. In part, it contributed to the mythical significance that the then small and unknown Cobra movement would acquire. The Amsterdam exhibition was followed by another small exhibition in a Brussels gallery and finally, in 1951, a final exhibition at the Musée Royal des Beaux-Arts in Liège. By that time, Cobra had already disbanded itself.

In Cobra No 7 (1950, Brussels), Dotremont describes how Cobra distinguished itself from other modernist movements by bringing people together, without distinction, even including their differences.4 In a later article, Dotremont calls Cobra a way of life, a real utopia that he describes as “the interaction of the individual and the community, the cooperation between different specialisms (painting, poetry, etc.), the cooperation between different countries and of different times [...], of the past and the present, the imaginary time and different temporalities [...] and the interaction between art and life.”5

Karel Appel, Drift op zolder | Passion in the Attic, 1947, Collectie Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Such lofty ideals existed mainly among the more theoretically interested members such as Dotremont, Jorn, and Constant; the question is what came out of these lofty ideals. First, it should be noted that for most members, creating a poem or a painting was paramount. They gave form to free, spontaneous creation and sought each other out. There was a general desire to escape the narrow and traditional post-war climate - but the expressions of Cobra members were not understood in every country, and there was still a lot of resistance to these newcomers.

The exhibition Freedom Without Borders does not aim to be a historical retrospective or a reflection on typical features of Cobra art. Instead, it places the work of Cobra artists in a broader context. The Cobra artists wanted to share their ideas with others and sought contact with like-minded people at the furthest corners of Europe. Any art that stood for experimentation, playfulness, provocation, and freedom could count on a response from the movement’s founders.

worden opgemaakt over hoe de Cobra-kunstwerken zich verhouden tot de internationale ontwikkelingen van die tijd.

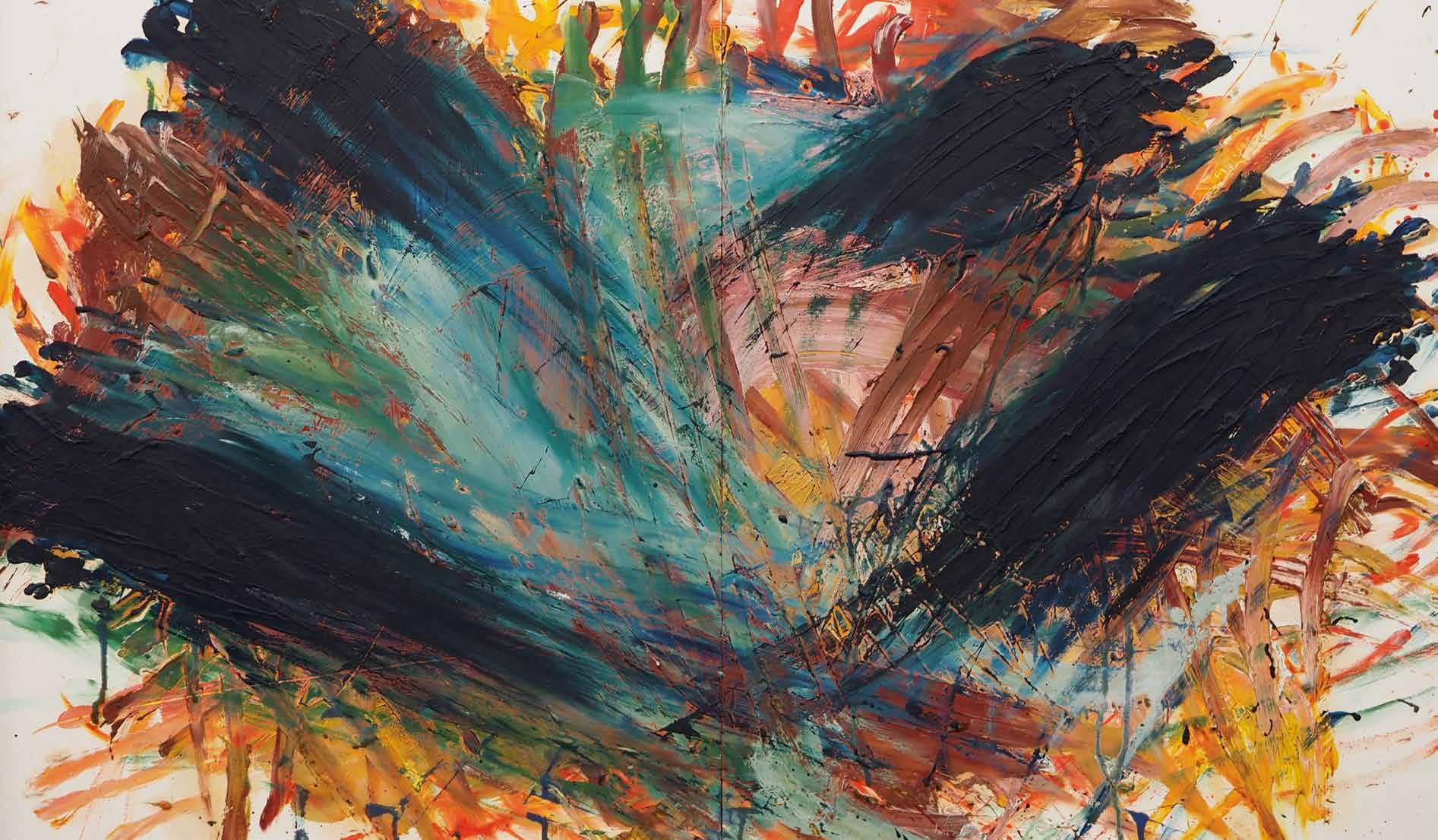

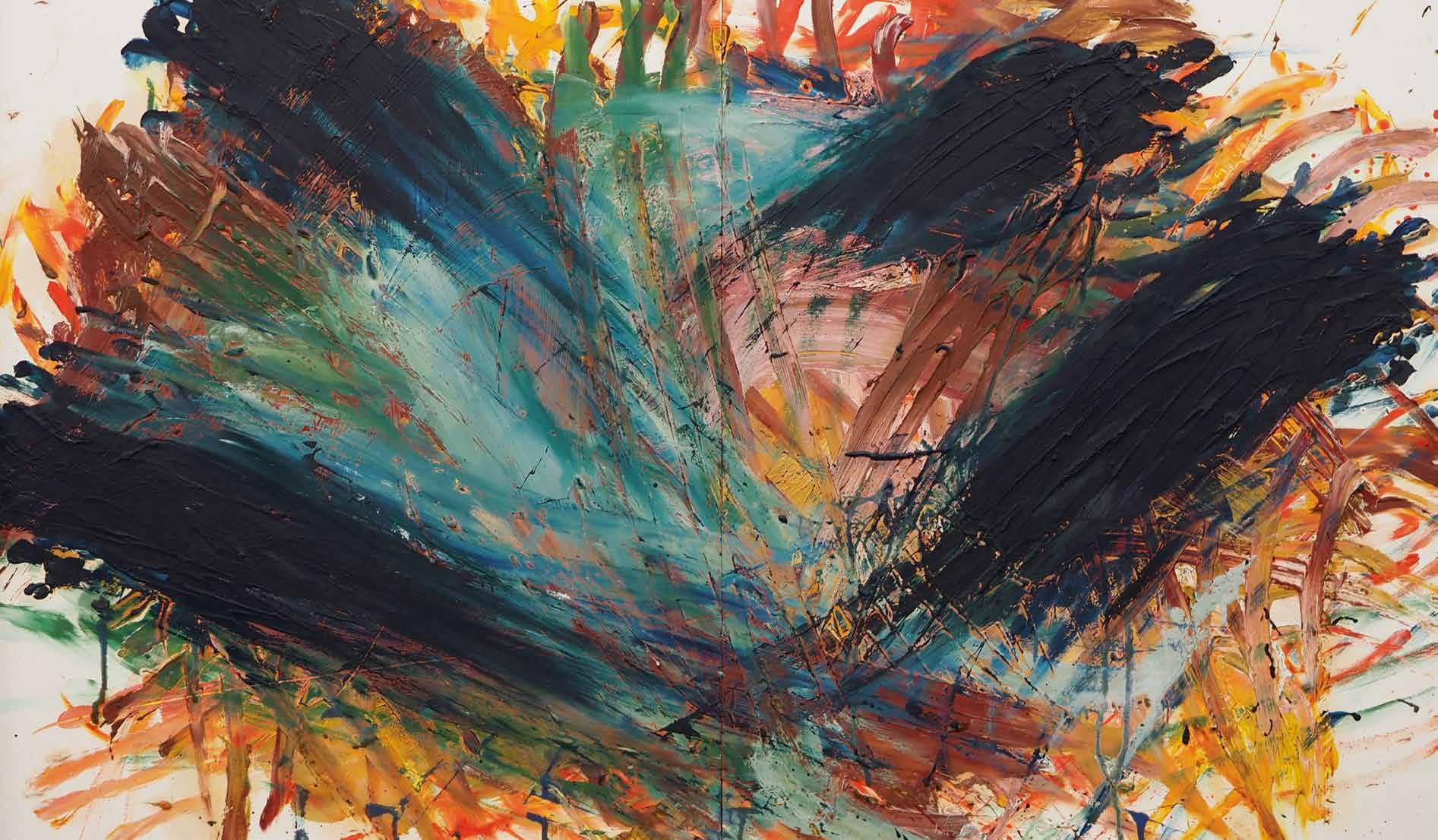

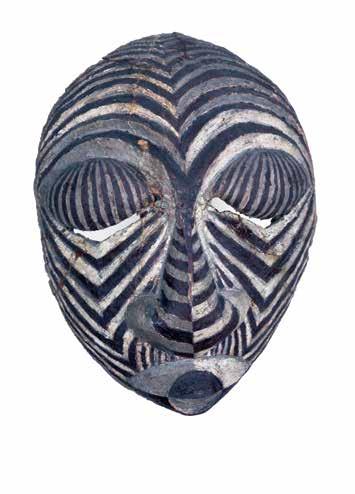

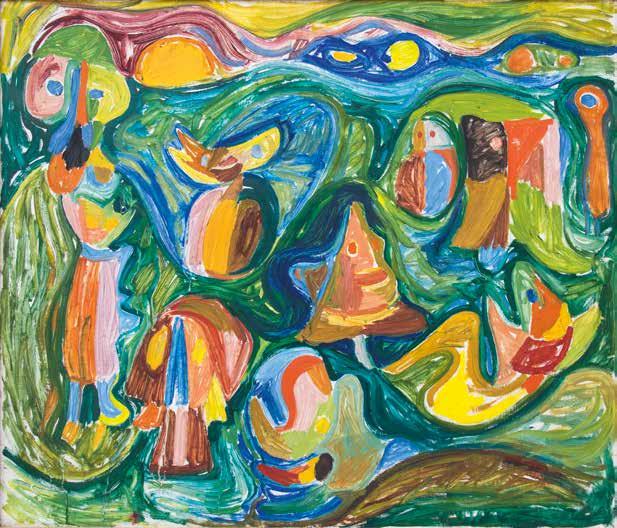

Om al die vergelijkingen niet in een eindeloze rij naast elkaar te plaatsen, zijn in de tentoonstelling enkele thema’s te herkennen. Die lopen van ‘Invloeden’ (kunstenaars die invloed hadden op Cobra), ‘Maskers en volkskunst’ (over de invloeden van kunst buiten Europa en Noord-Amerika, en volkskunst), ‘Natuur en mythische wezens’ (vooral belangrijk voor de Deense Cobra-kunstenaars), ‘Gebaar’ (verwijzend naar het abstract-expressionistische action painting in Amerika en het Europese tachisme), ‘Kind’ (over de invloed van de spontane ongekunstelde uitingen van het kind) en ten slotte ‘Cobra tussen Van Gogh en Jonathan Meese’, waar kunstwerken vanaf Van Gogh en het vroege Duitse expressionisme tot en met een jonge generatie kunstenaars worden getoond die in stijl of mentaliteit dicht bij Cobra staan.

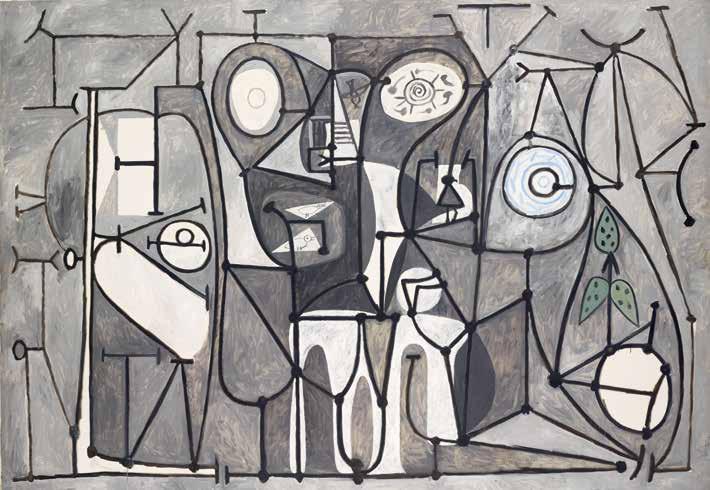

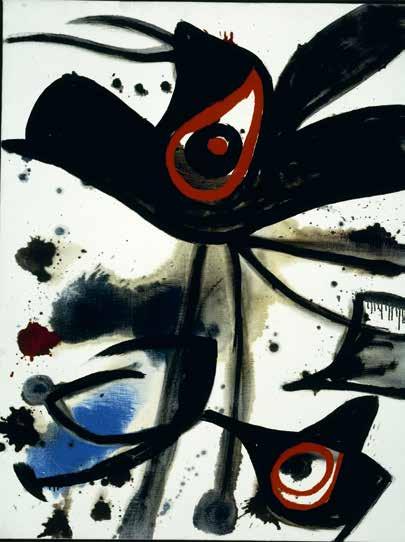

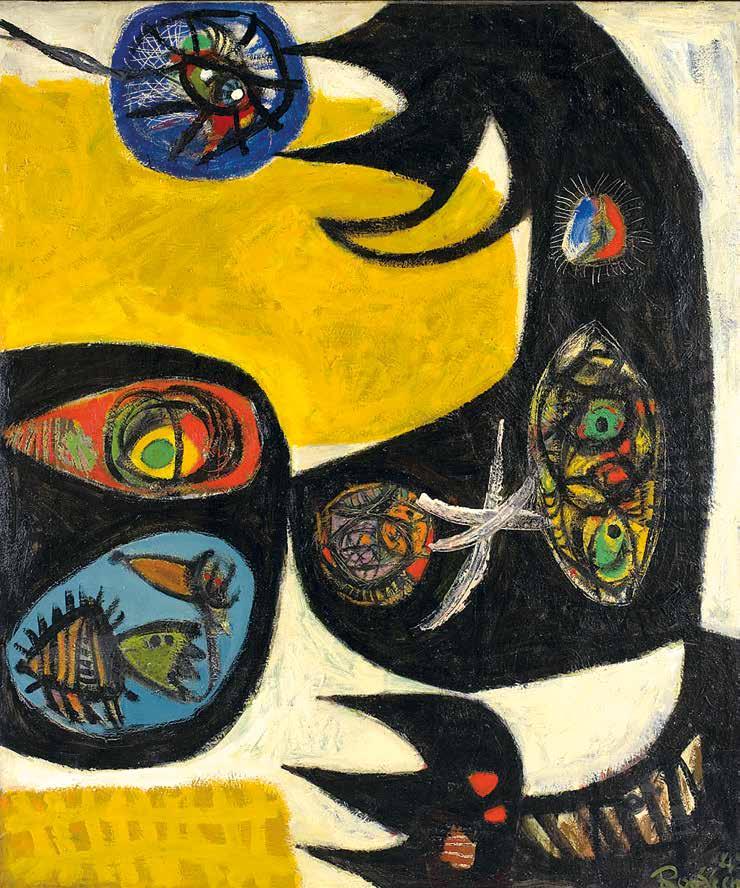

Het uitgangspunt van deze tentoonstelling is om een mise-en-scène te creëren waarin een werk van Appel kan worden vergeleken met een Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), en waarin een reliëf van Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) wordt getoond naast een reliëf van Brands. Je kunt ervaren hoe de speelsheid van Paul Klee (1879-1940) en de sprookjesachtige vormen van Joan Miró (1893-1983) belangrijk zijn geweest voor schilders als Brands, Wolvecamp en Rooskens. Deze opzet geeft de kijker de vrijheid om verbanden te volgen of te ontdekken, of andere visies te ontwikkelen.

In het thema ‘Invloeden’ wordt een aantal kunstenaars getoond die van invloed zijn geweest op het werk van Cobra-kunstenaars. Net na de oorlog was bij de Cobra-kunstenaars de blik op wat zich buiten Nederland in de kunst afspeelde nog gering. Moderne kunst was nog geen gebruikelijk onderdeel van wat de musea aanboden. Dat wil niet zeggen dat grote figuren als Picasso, Miró, Klee, Schwitters en de Duitse expressionisten voor deze jonge kunstenaars totaal onbekend waren. Vooral Picasso gold als een groot voorbeeld, evenals de kinderlijke speelsheid die ze herkenden in het werk van Klee. De surreële taal van Miró met bewegelijke mens- en dierfiguren die in de ruimte lijken te zweven, komt vooral terug in de composities van Rooskens, Wolvecamp en Constant.

By placing Cobra’s artworks alongside those of other artists not linked to Cobra, new cross-connections emerge. Moreover, in a retrospective occurring some seventy-five years after the movement’s founding, it becomes clear, by looking back, that there were major differences between the individual Cobra artists right from the start, and that everyone’s artistic development proceeded differently. Moreover, a preliminary assessment can now be made of how Cobra artworks related to the international developments of the time.

To avoid juxtaposing all these comparisons in an endless row, some themes can be identified in the exhibition. These run from ‘Influences’ (artists who influenced Cobra), ‘Masks and Folk Art’ (about the influences of art outside Europe and North America, and folk art), ‘Nature and Mythical Creatures’ (especially important for the Danish Cobra artists), ‘Gesture’ (referring to abstract-expressionist action painting in America and European tachisme), ‘Child’ (on the influence of the spontaneous, unsophisticated expressions of the child) and finally ‘Cobra between Van Gogh and Jonathan Meese’ (which shows artworks from Van Gogh and early German expressionism to a young generation of artists close to Cobra in style or mentality).

Pablo Picasso, Tête, (Hoofd | Head) Cannes, 1958, Musée national PicassoParis. Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979. MP358

Max Beckmann, Winterlandschaft (Winterlandschap | Winter Landscape), 1930, Collectie Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

Vanaf 1948 maakt Brands een serie assemblages van gevonden voorwerpen die hij op houten planken monteert. Binnen deze serie van zo een vijf tot zes reliëfs hebben sommige een compositie met een opbouw van rechthoekige vlakken, andere zijn losser van structuur. In alle gevallen gebruikt Brands felle, heldere kleuren – rood, blauw, geel, groen of oranje – en brengt hij andere materialen aan, zoals een uitgesponnen streng touw, een lapje bont of een ring van kurk beplakt met paardenhaar. In het gebruik van primaire en secundaire kleuren toont Brands zijn bewondering voor de werken van de De Stijlkunstenaars (een Nederlandse kunstbeweging, vernoemd naar het in 1917 in Leiden opgerichte tijdschrift De Stijl), maar er zijn ook duidelijke verwijzingen naar de etnografische objecten die hij al vroeg verzamelde. Bovendien zijn er parallellen met het reliëf Relief in relief (19421945) van Schwitters, die al direct na de Eerste Wereldoorlog alle ketenen van zich afschudde en met zijn ‘anti-kunstwerken’ begon. In Relief in relief monteert Schwitters stukjes hout en gips en dat levert onverwachte wendingen op. Dit ongepolijste, bevrijdende gebruik van ‘arme’ materialen zal voor veel Cobra-kunstenaars inspirerend zijn geweest. Ook het gipsen beeld Personage van Appel uit 1950 heeft op een bijzondere manier verwantschappen met de sculpturen die Schwitters al in de jaren 1920 heeft gemaakt.

The premise of this exhibition is to create a mise-en-scène in which a work by Appel can be compared to a Pablo Picasso (18811973), and in which a relief by Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) is shown next to a relief by Brands. You can experience how the playfulness of Paul Klee (1879-1940) and the fairy tale-like forms of Joan Miró (1893-1983) were important for painters like Brands, Wolvecamp and Rooskens. This format gives the viewer the freedom to follow or discover connections or develop other visions.

In the exhibition, ‘Influences’ shows several artists who influenced the work of Cobra artists. Just after the war, Cobra artists had a narrow view of what was happening in art outside the Netherlands. Modern art was not yet a common offering of museums. That is not to say that great figures like Picasso, Miró, Klee, Schwitters, and the German expressionists were completely unknown to these young artists. Picasso in particular was considered a great role model, as was the childlike playfulness they recognised in Klee’s work. Miró’s surreal language of moving human and animal figures, who seemed to float in space, was

Eugène Brands, Reliëf IX, 1948, Collectie Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Kurt Schwitters, Relief in Relief, c. 1942-45, Tate

particularly evident in the compositions of Rooskens, Wolvecamp, and Constant.

In 1948, Brands started making a series of assemblages using found objects which he mounted on wooden boards. Within this series of about five to six reliefs, some have a composition that used a structure of rectangular planes, while others were looser in structure. In all cases, Brands used bright colours - red, blue, yellow, green, or orange - and applied other materials, such as a spun-out strand of rope, a piece of fur, or a ring of cork plastered with horsehair. In the use of primary and secondary colours, Brands shows his admiration for the works of the De Stijl artists (a Dutch art movement named after the magazine De Stijl, founded in Leiden in 1917), but there are also clear references to the ethnographic objects he collected early on. Moreover, there are parallels with Relief in Relief (1942-1945) by Schwitters, who had already shaken off all shackles immediately after World War I and started his ‘anti-art works’. In Relief in Relief, Schwitters assembled pieces of wood and plaster, producing unexpected twists and turns. This unpolished, liberating use of

In zijn schilderij La Cuisine (De keuken; 1948) gebruikt Picasso contouren van vormen en kleuren die losstaan van een realistische weergave. Bij Schwitters is die relatie tussen contour en object nog verder uit elkaar komen te liggen. Hij ‘brak de vormen open’ en ‘monteerde’ ze weer aan elkaar, iets wat Appel vooral toepast in zijn reliëfs en zijn latere schilderijen. In hun reliëfs gebruiken Appel en Picasso de gevonden objecten en materialen op vergelijkbare manier. In Picasso’s Tête (Hoofd; 1958) is het een kistje, kurkdoppen en houten latjes; in Appels Drift op zolder (1947) stukjes hout met een paar vegen verf.

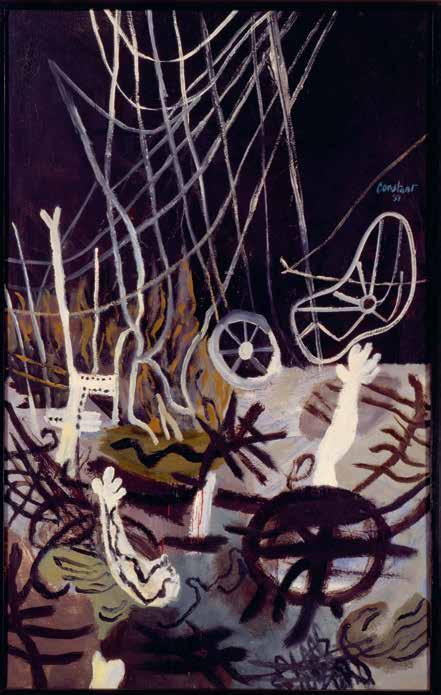

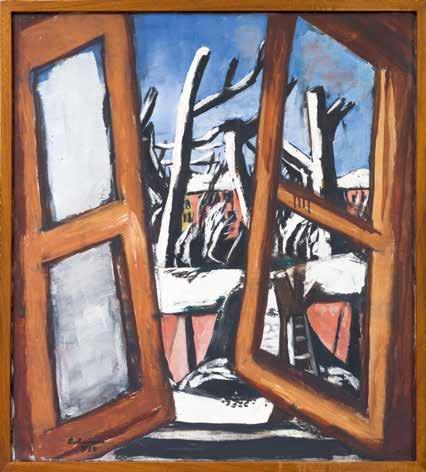

Een bijzondere combinatie binnen deze groep van ‘Invloeden’ zijn de schilderijen Verschroeide aarde III (1951) van Constant en Winterlandschaft (Winterlandschap; 1930) van Max Beckmann (1884-1950). Beckmann schilderde het uitzicht op een binnenplaats met zwarte takken en beschadigde huizen op de achtergrond. De ramen van het venster zijn ontwricht. Waarschijnlijk schilderde hij deze scène als herinnering aan de verwoestingen van de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Het schilderij Verschroeide aarde toont de verwoestingen van de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Zowel voor Constant als voor Beckmann is de oorlog zo een ingrijpende gebeurtenis geweest, dat zij hier wel op moesten reageerden. Beide schilderijen zijn een aanklacht tegen het oorlogsgeweld.

Wat in de kunst direct na de Tweede Wereldoorlog opvalt, is het terugkerend verlangen naar ‘het primitieve’. Dit leidde tot een nieuwe oriëntatie op de uitingen van andere culturen en

‘poor’ materials would inspire many Cobra artists. Appel’s 1950 plaster sculpture Personage also shows special affinities with the sculptures Schwitters had made in the 1920s.

In his painting The Kitchen (1948), Picasso uses contours of shapes and colours that are separate from a realistic representation. With Schwitters, that relationship between contour and object is even further separated. He ‘broke open’ the forms and ‘reassembled’ them, something Appel applies especially in his reliefs and later paintings. In their reliefs, Appel and Picasso used found objects and materials in similar ways. In Picasso’s Head (1958), this takes form as a box, cork caps and wooden slats; in Appel’s Passion in the Attic (1947), pieces of wood with a few smudges of paint.

An unusual combination within this group of ‘Influences’ are the paintings Scorched Earth III (1951) by Constant and Winter Landscape (1930) by Max Beckmann (1884-1950). Beckmann painted the view of a courtyard with black branches and damaged houses in the background. The panes of the window are dislocated. He probably painted this scene as a reminder of the devastation of the First

World War. The painting Scorched Earth, on the other hand, shows the devastation of World War II. For both Constant and Beckmann, the war had been such a profound event that they were required to react to it. Both paintings are an indictment of the violence of war.

What is striking in the art immediately after World War II is the recurring desire for ‘the primitive’. This led to a new orientation towards the expressions of other cultures and the ‘untainted’ creations of children and the ‘mentally ill’. Members of the Experimental Group also sought a much more open view of what could be counted as ‘art’. In his article Authentic Folk Music, Brands argues for more attention to world music.6 He proposes organising an evening at which he will: ‘feature music from the Caucasian mountains, from Persia, Arabia, Turkey, Hindustan, Pre-India (Meerut), Java, Bali, Sunda, China, Japan, West Africa (Gold Coast), up to and including Congo expedition recordings of the Pygmies, in which one hears jungle drums and jungle xylophones, interspersed with spontaneous collective singing.’ This interest of Brands in world music paralleled his interest in ethnography and the universe. In all

de ‘onbesmette’ creaties van kinderen en ‘geesteszieken’. Ook de leden van de Experimentele Groep streefden naar een veel opener kijk op wat tot ‘de kunst’ gerekend kan worden. In zijn artikel ‘Authentieke Volksmuziek’ pleit Brands voor meer aandacht voor wereldmuziek.6 Hij stelt voor een avond te organiseren waarop hij: ‘muziek laat horen uit het Kaukasische gebergte, uit Perzië, Arabië, Turkije, Hindoestan, Voor-Indië (Meerut), Java, Bali, Soenda, China, Japan, WestAfrika (goudkust), tot en met Congo-expeditie-opnamen van de Pygmeeën, waarin men jungle drums en jungle-xylofoons hoort, afgewisseld met spontaan collectief gezang.’ Deze interesse van Brands voor wereldmuziek liep parallel aan zijn interesse voor etnografica en het heelal. In al die gebieden zijn vooral de magische krachten het centrale onderwerp, en de objecten waarin hij die vooral terugvond zijn de etnografische maskers. Als Brands tijdelijk werkt in de zaak van Louis Lemaire, een Amsterdamse handelaar in aziatica en etnografica, tekent hij de daar aanwezige maskers. Iets daarna begint hij, geïnspireerd op de voorbeelden die hij had leren kennen, zelf maskers te maken met papier-maché, stof, kralen, veren en stukjes glas. Hij liet zich, getooid met de maskers en poserend in verschillende houdingen en kledij, fotograferen door Frits Lemaire, de zoon van Louis Lemaire.

Zowel Brands als Constant waren kritisch ten opzichte van het koloniale bewind en de zogenaamde superioriteit van de westerse cultuur. Zij zetten zelfs vraagtekens bij de rol van hun voorbeelden Klee en Gauguin, maar uiteindelijk maakten ook zij gebruik van de handel in etnografische objecten uit Oceanië en Afrika.7

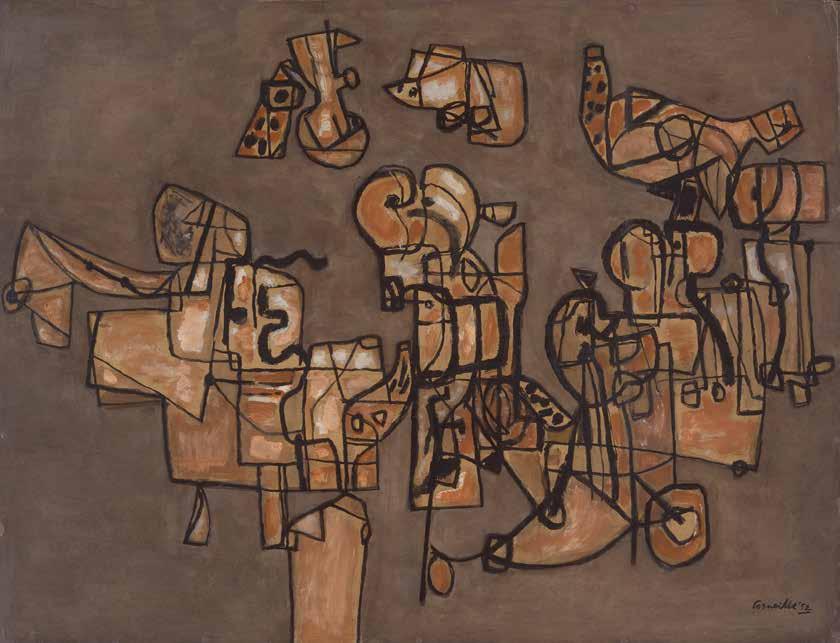

Al snel deelden de andere Nederlandse Cobra-leden deze interesse in het ‘volkse’ en ‘onbedorven’ karakter van culturen buiten Europa en de Verenigde Staten. Zo reisde Corneille, samen met Van Eyck, in 1950 naar Noord-Afrika en later ook naar Azië en Noord- en ZuidAmerika. Geïnspireerd door de eerdere reizen van Klee ging Corneille in Afrika op zoek naar

Robert Jacobsen, Zonder titel (Untitled), 1958, Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen

Eugène Brands, Masker (Mask), 1947, Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen

these areas, magical forces were the central subject, and the objects in which he found them, in particular, were ethnographic masks. Brands worked temporarily in the business of Louis Lemaire, an Amsterdam dealer in Asian art and ethnographic objects. There, he started drawing the displayed masks. Later, inspired by the examples he’d seen in the shop, Brands began making his own masks with papier-mâché, fabric, beads, feathers, and pieces of glass. He had himself photographed by Frits Lemaire, Louis Lemaire’s son, adorned with the masks and posing in various poses and attire.

Both Brands and Constant were critical of colonial rule and the so-called ‘superiority’ of Western culture. They even questioned the role of their inspirations, Klee and Gauguin; but, ultimately, they also took advantage of the trade in ethnographic objects from Oceania and Africa.7

Soon the other Dutch Cobra members shared this interest in the ‘vernacular’ and ‘unspoilt’ nature of cultures outside Europe and the United States. Corneille, together with Van Eyck, travelled to North Africa in 1950 and later to Asia and North and South

Zoltán Kemény, Head of a Horse (Paardenkop), 1949, privécollectie

Romuald Hazoumè, J.K., 2020, met dank aan MAGNIN-A Gallery, Parijs

America. Inspired by Klee’s earlier trips, Corneille went to Africa in search of authentic images and colours. The first trip to the Hoggar mountains in Algeria in 1952 led to paintings filled with abstracted groups of people in the earthy colours of yellow and brown.

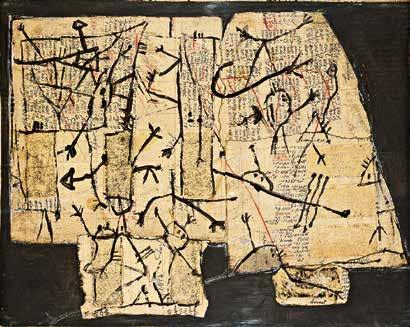

The primal characters Corneille used in The Nomads (1952) are also present in the paintings by Jean-Michel Atlan (1913-1960) and Jacques Doucet (1924). These French artists joined the Cobra group early on. Doucet made paintings in which he mainly used primitive ‘signs and scribbles’ like those found in prehistoric rock walls. Atlan painted mostly abstract animal or human signs that seem to be derived from African mythical figures. Like Atlan and Doucet, Belgian Raoul Ubac (1910-1985) was initially inspired by surrealism. Through Dotremont, he would become involved in Cobra activities after 1949, including exhibitions in Amsterdam and Liège. A snake head engraved by Ubac was used for the cover of the magazine Cobra No. 7.

In Denmark, artists from the artists’ association Høst advocated for free art in the magazine Helhesten (The Hell’s Horse). Heerup

authentieke beelden en kleuren. De eerste reis naar het Hoggargebergte in Algerije leidde in 1952 tot schilderijen met geabstraheerde groepen mensen in de aardse kleuren geel en bruin.

De oertekens die Corneille gebruikte in Les Nomads (De nomaden; 1952) zijn ook aanwezig in schilderijen van JeanMichel Atlan (1913-1960) en Jacques Doucet (1924). Deze Franse kunstenaars hadden zich al vroeg bij de Cobra-groep aangesloten. Doucet maakte schilderijen waarin hij vooral primitieve ‘tekens en krabbels’ gebruikte zoals je die ook in prehistorische rotswanden kunt vinden. Atlan schilderde vooral abstracte dier- of menstekens die afgeleid lijken te zijn van Afrikaanse mythische figuren. Net als Atlan en Doucet was de Belg Raoul Ubac (1910-1985) aanvankelijk geïnspireerd door het surrealisme. Via Dotremont zou hij na 1949 betrokken raken bij Cobra-activiteiten, waar-onder de tentoonstellingen in Amsterdam en Luik. Een door Ubac gegraveerde slangenkop werd gebruikt voor de omslag van het tijdschrift Cobra No. 7.

In Denemarken waren het kunstenaars van de kunstenaarsvereniging Høst die in het tijdschrift Helhesten (Het Hellepaard) pleitten voor een vrije kunst. Misschien beantwoordt Heerup nog wel het meeste aan het ideaal van de ‘volkse’, niet aan academische regels gebonden kunstenaar. Al vanaf 1930 maakte hij geassembleerde sculpturen uit gevonden voorwerpen en materialen. In een veld bij zijn huis plaatste hij bewerkte en soms beschilderde granieten stenen. Deze sculpturen zijn ontstaan nadat hij op Jutland de zogenoemde ‘Jelling-stenen’ of runenstenen had leren kennen.

perhaps most closely corresponds to the ideal of the ‘vernacular’ artist not bound by academic rules. As early as 1930, he had made assembled sculptures from found objects and materials. He arranged, worked, and sometimes painted granite stones in a field near his house. These sculptures were created after he had learned about the so-called Jelling Stones, or runic stones, found in Jutland.

Romuald Hazoumè (1962), from a very different starting point than Heerup, but with the same lightness and precision, created his sculptures from found materials. For his head, J.K. (2020), he used discarded plastic oil tanks and coloured strands of yarn. His ‘heads’ are not only humorous assemblages but also have cultural and political meanings. It is precisely by not making a traditional ‘mask’ that he detaches himself from the ritual function a mask fulfils in African tradition. The use of old jerry cans and decorative strands of colour could be interpreted as a reference to the exploitation of African raw materials by Western countries, while the ‘exotic’ masks made of cheap materials are reminiscent of tourist commodities and the mainly Western waste of consumer goods.

Henry Heerup, Napoleon, 1944, Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen

Shinkichi Tajiri, Warrior (Krijger), 1961, Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen

The Dane, Robert Jacobsen (1912-1993) who, although in contact with several Cobra members, was never officially part of it, used leftover iron to create a head with a dramatic expression. Tajiri also created standing figures (warriors, guerrillas, or samurai) with leftover iron. Tajiri had taken classes in Paris around 1948 with the sculptors Ossip Zadkine (1888-1967) and Fernand Léger (1881-1955). In Paris, Tajiri met some members of the Experimental Group, which led to him joining the Cobra group in 1949. Tajiri had fought as a soldier in the US army and his war experiences make appearances in many of his sculptures. Another recurring theme is the samurai figure who, as an unconditional guardian, keeps communities safe from danger. Tajiri stated in regard to his stately sculptures, “They expressed my need to purify myself from the horrors of war. Both Warrior and Untitled (Samurai), both from 1961, consist of iron parts welded together. Through the intermingling of acids and weldedon nails a rough and vibrant surface is created, a ‘battered skin’ that for Tajiri refers to the scorched earth, where nature nevertheless finds the strength to recover.

Vanuit een heel ander startpunt dan Heerup, maar met dezelfde lichtheid en precisie, maakt Romuald Hazoumè (1962) zijn sculpturen uit gevonden materialen. Voor zijn ‘kop’ J.K. (2020) gebruikt hij afgedankte jerry cans en gekleurde strengen garens. Zijn ‘koppen’ zijn niet alleen humorvolle assemblages maar hebben ook culturele en politieke betekenissen. Juist door niet een traditioneel ‘masker’ te maken, maakt hij zich los van de rituele functie die een masker in de Afrikaanse traditie vervult. Het gebruik van oude jerrycans en het gebruik van de decoratieve kleurstrengen zou je kunnen opvatten als een verwijzing naar de exploitatie van Afrikaanse grondstoffen door westerse landen, terwijl de ‘exotische’ maskers van goedkope materialen doen denken aan toeristische handelswaar en de, vooral westerse, verspilling van consumentenartikelen.

De Deen Robert Jacobsen (1912-1993) – die weliswaar in contact stond met verschillende Cobra-leden maar er nooit officieel deel van uitmaakte – gebruikt restanten ijzer om een kop met een dramatische expressie te maken. Ook Tajiri maakte met restanten ijzer staande figuren (warriors, gueriers - krijgers - of samoerai). Tajiri heeft in Parijs rond 1948 lessen gevolgd bij de beeldhouwer Ossip Zadkine (1888-1967) en Fernand Léger (1881-1955). In Parijs ontmoette hij enkele leden van de Experimentele Groep en dat leidde ertoe dat hij in 1949 toetrad tot de Cobra-groep. Tajiri heeft als soldaat in het Amerikaanse leger gevochten en zijn oorlogservaringen spelen door in veel van zijn sculpturen. Een ander terugkerend thema is de samoerai-figuur die als onvoorwaardelijke bewaker de gemeenschappen behoedt voor gevaren. Over zijn statige sculpturen verklaarde Tajiri: ‘Zij drukten mijn behoefte uit mij te zuiveren van de gruwelen van de oorlog.’ Zowel Warrior (Krijger) als Zonder titel (Samoerai ), beide uit 1961, bestaan uit ijzeren, aan elkaar gelaste onderdelen. Door de inwerking van zuren en opgelaste spijkers is een ruw en levendig oppervlak ontstaan, een ‘gehavende huid’ die voor Tajiri verwijst naar de verschroeide aarde, waar de natuur toch weer de kracht vindt om te herstellen.

Evenals Tajiri had Ferdi (Ferdina Tajiri-Jansen; 1927-1969) tijdens haar verblijf in Parijs (1951-1952) lessen gevolgd bij Zadkine. In Parijs leerde zij naast Tajiri Nederlandse kunstenaars kennen zoals Appel, Constant, Corneille, Bram Bogart (1921-2012), de schrijver Simon Vinkenoog (1928-2009) en de Belgische schrijver Hugo Claus (1929-2008).

Like Tajiri, Ferdi (Ferdina Tajiri-Jansen; 1927-1969) had taken classes with Zadkine during her stay in Paris (1951-1952). Besides Tajiri, Ferdi got to know Dutch artists such as Appel, Constant, Corneille, Bram Bogart (1921-2012), the writer Simon Vinkenoog (1928-2009) and the Belgian writer Hugo Claus (1929-2008) during her time in Paris. Initially, Ferdi mainly made jewellery and iron sculptures, but after several trips to the United States and Mexico (between 1966 and 1969), and after observing the vegetation with its exorbitant shapes and colours, her sculptures changed. These later sculptures are composed of steel palisades covered with foam plastic, fur, and other textile materials. They are sumptuously organic objects, often with a sensual and erotic character. These ‘Hortus sculptures’ grew in her studio, so to speak. Using nature as a sexual metaphor, Ferdi anticipated a period of sexual freedom in her work. In an interview, she marvelled at the exclusive right of male artists to display erotically tinged elements. “There are people who say it is not befitting for a woman to put things to do with sex so openly in a museum. Why not? That’s not a man’s private domain, is it?”8

Aanvankelijk maakte Ferdi vooral sieraden en ijzerplastieken, maar na een aantal reizen naar de Verenigde Staten en Mexico (tussen 1966 en 1969) zou de daar aanwezige vegetatie met haar exorbitante vormen en kleuren een grote invloed hebben op haar plastieken. Die zijn opgebouwd uit stalen staketsels, omkleed met schuimplastic, bont en andere textiele materialen. Het zijn weelderig organische objecten, vaak met een sensueel en erotisch karakter. Deze ‘Hortussculpturen’ groeiden als het ware voort in haar atelier. Met de natuur als seksuele metafoor liep Ferdi in haar werk voor op een periode van seksuele vrijheid. In een interview verwonderde zij zich over het alleenrecht van mannelijke kunstenaars om erotisch getinte elementen te tonen: ‘Er zijn mensen die zeggen dat het een vrouw niet past om zo openlijk dingen in een museum te zetten die met seks te maken hebben. Waarom niet? Dat is toch geen privéterrein voor de man?’8

Frieda Hunziker (1908-1866) was geen lid van de Cobra-beweging maar van de kunstenaarsgroep Vrij Beelden (1947-1955). De leden van deze groep hadden gemeen dat zij een abstractere stijl van werken hadden en zij stonden daarmee tegenover de uitgangspunten van Cobra, die minder formeel waren. Maar haar werk is een periode sterk beïnvloed geweest door Appel. Na een reis naar Curaçao raakte zij geïnspireerd door de heldere kleuren in het landschap en transformeerde zij haar indrukken in heldere gestileerde vormen en kleuren.

Frieda Hunziker, No. 5, 1954, Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen

Frieda Hunziker (1908-1866) was not a member of the Cobra movement but of the artist group Vrij Beelden (1947-1955). The members of this group had a more abstract style of working and they were thus opposed to Cobra’s principles, which were less formal. But for a period, Hunziker’s work was strongly influenced by Appel. After a trip to Curaçao, she was inspired by the bright colours in the landscape and transformed her impressions into bright, stylised shapes and colours.

Munch’s position within the development of modern art is that of an outsider rather than a pioneer. Whereas Van Gogh can be called the earthly father of expressionism, and Cézanne was at the cradle of cubism and geometric-abstract art, Munch’s early work was seen mainly as symbolist. This links him more to the 19th than to the 20th century.

However, in his later paintings, in which he became much freer and more expressive, the emphasis was increasingly on the intrinsic meaning of painting. Artists like Jorn, Per Kirkeby (1938-2018),

Jacques Doucet, Nachtelijk feest in Rue Blomet, 1948, Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen, langdurige bruikleen

Jean-Michel Atlan, Zonder titel (Untitled), 1949, Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen, langdurige bruikleen

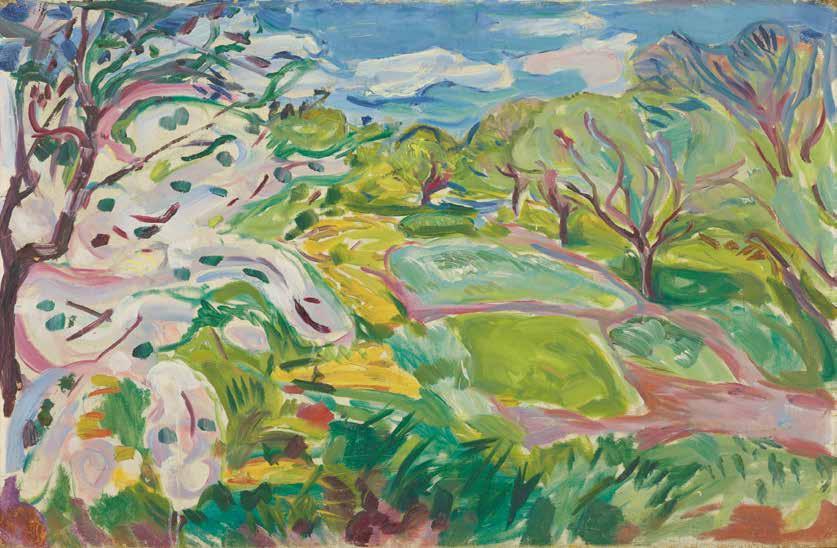

and Georg Baselitz (1938) recognised the expressive power and freedom in these later landscapes and portraits. Jorn visited a major retrospective of Munch in Oslo in 1945. There he saw not only Munch’s symbolist paintings (which he already knew from pictures), but also the paintings from the last three or four decades. This introduction was of great importance to Jorn, and afterwards his paintings became “freer and more direct” and had a “liberating effect of colour”.9

Munch’s influence can already be seen in the 1946 painting Midsummer Games. The wavy lines and loose way of painting with bright colours were surprisingly close to Munch’s thinly painted and moving Fruit Trees in Blossom in the Wind from 19171919. Probably thanks to Munch, Jorn understood even better

De positie van Munch binnen de ontwikkeling van de moderne kunst is eerder die van een buitenstaander dan van een pionier. Waar Van Gogh als aardsvader van het expressionisme genoemd kan worden en Cézanne aan de wieg stond van het kubisme en de geometrischabstracte kunst, werd Munchs vroege werk vooral als symbolistisch gezien. Dat verbindt hem meer met de negentiende dan met de twintigste eeuw.

In zijn latere schilderijen, waarin hij veel vrijer en expressiever werd, ligt de nadruk echter steeds meer op de intrinsieke betekenis van het schilderen. Kunstenaars als Jorn, Per Kirkeby (1938-2018) en Georg Baselitz (1938) herkenden de expressieve kracht en vrijheid in deze latere landschappen en portretten. Jorn bezocht in 1945 een grote overzichtstentoonstelling van Munch in Oslo. Hij zag er niet alleen Munchs symbolistische schilderijen (die hij al van afbeeldingen kende), maar ook de schilderijen uit de laatste drie of vier decennia. Deze kennismaking was van groot belang voor Jorn en zijn schilderen werd ‘vrijer en directer’ en had een ‘bevrijdende werking van kleur’.9

In het schilderij Jeux d’été (Zomerspelen) uit 1946 is de invloed van Munch al terug te vinden. De golvende lijnen en de losse manier van schilderen met heldere kleuren komen verrassend dicht bij het dun geschilderde en bewegelijke Blomstrende frukttrær i vind (Bloeiende fruitbomen in de wind) uit 1917-1919 van Munch. Waarschijnlijk heeft Jorn dankzij Munch nog

Edvard Munch, Blomstrende frukttrær i vind (Bloeiende fruitbomen in de wind | Fruit Trees in Blossom in the Wind), 1917–1919 c/o Munchmuseet

Asger Jorn, Jeux d’été (Zomerspelen/ Midsummer Games), 1945, Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Aalborg

that painting is not always about an idealised representation of nature, but the transformation of nature imbued with a psychic or mysterious charge.10

Carl-Henning Pedersen’s 1946 painting Beyond the Dream is populated by oppressive fantasy creatures reminiscent of the poignant figure in Munch’s The Scream (1893). This atmosphere of threat and agony can also be seen in an early painting by Jacqueline de Jong (1939). Her paintings, which originated around 1960, have direct brush movements and bright and clear colours.

Erik Ortvad (1917-2008) was one of the youngest members of the Danish artists’ association Høst. In the painting People and Horses (1944) the undulating shapes of tree branches, people, and

horses predominate in a palette of soft colours of green, yellow, and pink. Both humans and animals are one with nature. The painting seems to be a homage to life. On the right, a mythical figure towers over the scene and on the left an upside-down creature appears to protect the couple and the new-born child. In Movement, from 1948, the figurative elements have disappeared, and it is as if only the small green, yellow, and soft-brown colour areas still refer to nature.

With primitive trolls and mythical creatures, Jacobsen’s paintings are the opposite of cosy or harmonious. Rather, they match the raw expressive style of Nieuwenhuijs and Lotti van der Gaag (1923-1999). Nieuwenhuijs’ world is filled with fantasy creatures like cyclopes and animal-human figures that seem to float in

beter begrepen dat het niet gaat om een geïdealiseerde voorstelling van de natuur, maar om de transformatie van de natuur doortrokken van een psychische of mysterieuze lading.10

Carl-Henning Pedersens schilderij Drømmen over byei (De droom voorbij) uit 1946 wordt bevolkt door beklemmende fantasiewezens die doen denken aan de aangrijpende figuur uit The Scream (De Schreeuw; 1893) van Munch. Die sfeer van dreiging en agonie is ook te zien in een vroeg schilderij van Jacqueline de Jong (1939). Haar schilderijen die rond 1960 ontstaan hebben directe penseelbewegingen en felle en heldere kleuren.

Erik Ortvad (1917-2008) was een van de jongste leden van de Deense kunstenaarsvereniging Høst. In het schilderij People and Horses (Mensen en paarden, 1944) overheersen de golvende vormen van boomtakken, mensen en paarden in een palet van zachte kleuren groen, geel en roze. Zowel mens als dier is één geheel met de natuur. Het schilderij lijkt een hommage aan het leven. Aan de rechterzijde torent een mythisch figuur hoog boven de scène uit, en aan de linkerzijde is een op zijn kop geschilderd wezen te zien dat het paar en het pasgeboren kind lijken te beschermen. In Bevaegelse (Beweging) uit 1948 zijn de figuratieve elementen verdwenen en is het alsof alleen de kleine groene, gele en zacht-bruine kleurvlakjes nog aan de natuur refereren.

De schilderijen van Jacobsen zijn met de primitieve trollen en mythische wezens het tegenovergestelde van behaaglijk of harmonieus. Zij sluiten eerder aan bij de rauwe expressieve stijl van Nieuwenhuijs en Lotti van der Gaag (1923-1999). De wereld van Nieuwenhuijs is gevuld met fantasiewezens als cyclopen en dier-mensfiguren die lijken te zweven in een nachtelijke droomwereld. Harde witte en gele lijnen steken af tegen een donkere achtergrond met heldere kleuren rood, violet, geel, groen en blauw. In zijn werk ontwikkelt Nieuwenhuijs een eigen versie van een surreëel expressionisme. Ook in het werk van Van der Gaag duiken voortdurend fantasiewezens op. Naast haar schilderijen zou zij vooral bekend worden met haar sculpturen.

Het zijn antropomorfe wezens die vaak zijn afgebeeld in geagiteerde of dreigende houdingen. De open beelden die in klei of gips zijn opgebouwd, hebben een wilde en primitieve uitstraling

Jacqueline de Jong, Le vent s’enfolle (Nachtdieren | Night Animals), 1961. Collectie Ambassade Hotel Amsterdam

Carl-Henning Pedersen, Drømmen over byen (Bloeiende fruitbomen in de wind | Fruit Trees in Blossom in the Wind), 1946, Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen, langdurige bruikleen

a nocturnal dream world. Harsh white and yellow lines stand out against a dark background with bright colours such as red, violet, yellow, green, and blue. In his work, Nieuwenhuijs develops his own version of surreal expressionism. Fantasy creatures also constantly appear in Van der Gaag’s work. Aside from her paintings, she would become best known for her sculptures.

They are anthropomorphic creatures often depicted in agitated or menacing poses. The open sculptures constructed in clay or plaster have a wild and primitive look that has much in common with Cobra’s visual language. From 1950, Van der Gaag would work in the same complex on Rue Santeuil in Paris as Appel, Corneille, and other Dutch artists such as Dora Tuynman (1926-1979), Bogart, and Kees van Bohemen (1928-1985). The complex was in fact a tannery, some rooms of which were rented out as studios. The foul air and the cold in winter months were harsh on everyone.