Jean-Yves Mollier

Found on every continent, traditionally in the form of a stall open to the street but today endowed with handsome display windows, bookstores have been part of the urban landscape for over five thousand years. Bookstores as we know them appeared in Athens by the sixth or fifth century bce, and in Rome in the days of Cicero, Horace, Martial, and Seneca. It was in the latter city, with over a million inhabitants, that tabernae librariae became lasting features of everyday life. In an 1866 illustration by Heinrich Leutemann reflecting archaeological discoveries at Pompeii, the beholder is deliberately drawn into the interior of a shop run by the bibliopola, a merchant who kept perhaps a dozen slaves, including librarii. The librarii copied manuscripts to be reread by another enslaved worker, who was literate, as were those who showed parchment scrolls to customers. Such customers were wealthy Romans in search of novelty, their curiosity piqued by a sheet of parchment chained to a post outside the taberna libraria as well as by ads painted in red on the whitewashed walls of the shop, in a neighborhood close to the forum, where Romans habitually strolled.

A close look at such illustrations, designed to inform the nineteenth-century German public of scholarly discoveries, reveals several interior features that survived right up to the fall of the Roman Empire. The wooden cupboard and shelves held books, whether still in the form of a volumen (scroll) or already a codex (the bound pages used as early as the first centuries bce). The bookdealer often enslaved rather than free, educated by teachers with a Hellenistic background and thus aware of the importance of reading appeared in the literature of the day: poets like Martial and Horace mentioned several of them (such as Secundus, a freedman), as did orators like Cicero, who complained of the poor

In the West, the book trade was born with the emergence of universities in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Booksellers set up shop in the surrounding area to supply manuscripts to teachers and students. Invented by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany, in the 1450s, the movable-type printing press profoundly changed the book market. It reached Italy as early as 1464–65, France in 1470, Spain in 1472, Belgium and the Netherlands in 1473, and England in 1476. Alongside the merchant-booksellers, a new profession now emerged: printers.

In the seventeenth century, the major trading centers, notably Venice, became the main publishing centers. The rapid spread of the Lutheran Reformation was due in large part to printing hence attempts to control its output. In most European countries, publishers were required to obtain authorization to print. State censorship was joined by that of the Catholic Church with the introduction, in 1558, of the Index librorum prohibitorum, a list of works banned by Rome that continued to be regularly updated until the mid-twentieth century. In the second half of the sixteenth and at the beginning of the seventeenth century, book professionals formed guilds. The Stationers’ Company in London, local booksellers’ guilds in the Netherlands, and communities of printers and booksellers in France regulated the book trade and access to it. A new geography of publishing also took shape. With the end of the Wars of Religion in 1598 (Edict of Nantes), France became the center of gravity for publishing. However, it faced competition from the United Provinces the northern part of the Netherlands separated in 1579 from the Spanish-ruled southern part which experienced spectacular growth in the seventeenth century. The Elzevier dynasty of printers and booksellers, established in Leiden and then Amsterdam, was particularly prominent.

While books remained relatively rare and expensive in preindustrial Europe, there was a form of

In North America, the first print shops followed a little later by the first real bookstores were the product of colonization. Some native peoples had writing systems, but no business activity similar to a book trade. It was colonial missionaries and administrators who brought the first Bibles, and who imported the equipment for printing the documents indispensable to governance. Private printers followed, notably to service the press, and thus North America experienced an explosion of newspapers in English, German, French, and Spanish.

In rapidly developing cities such as New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Montreal, the publishing trade emerged by the early eighteenth century. Benjamin Franklin started as a printer in Boston and New York before settling in Philadelphia, enjoying great success with his Poor Richard’s Almanack , which was soon imitated elsewhere, including in

Europe, under titles such as Pauvre Richard and Bonhomme Richard. Early bookstores appeared in the same era as the first libraries and reading rooms, just as school systems encouraged more immigrants to begin reading. From 1750 to 1800, booksellers in New York and Montreal did not usually specialize; they worked out of shops that were less like today’s bookstores and more like emporia offering kitchen wares, furs, and various other goods. Yet the vitality of the New World book trade was confirmed as big European printer-publishers, such as Bossange in Bordeaux and Mame in Angers (later Tours), sent several of their offspring to North America to open bookstores between 1800 and 1810.

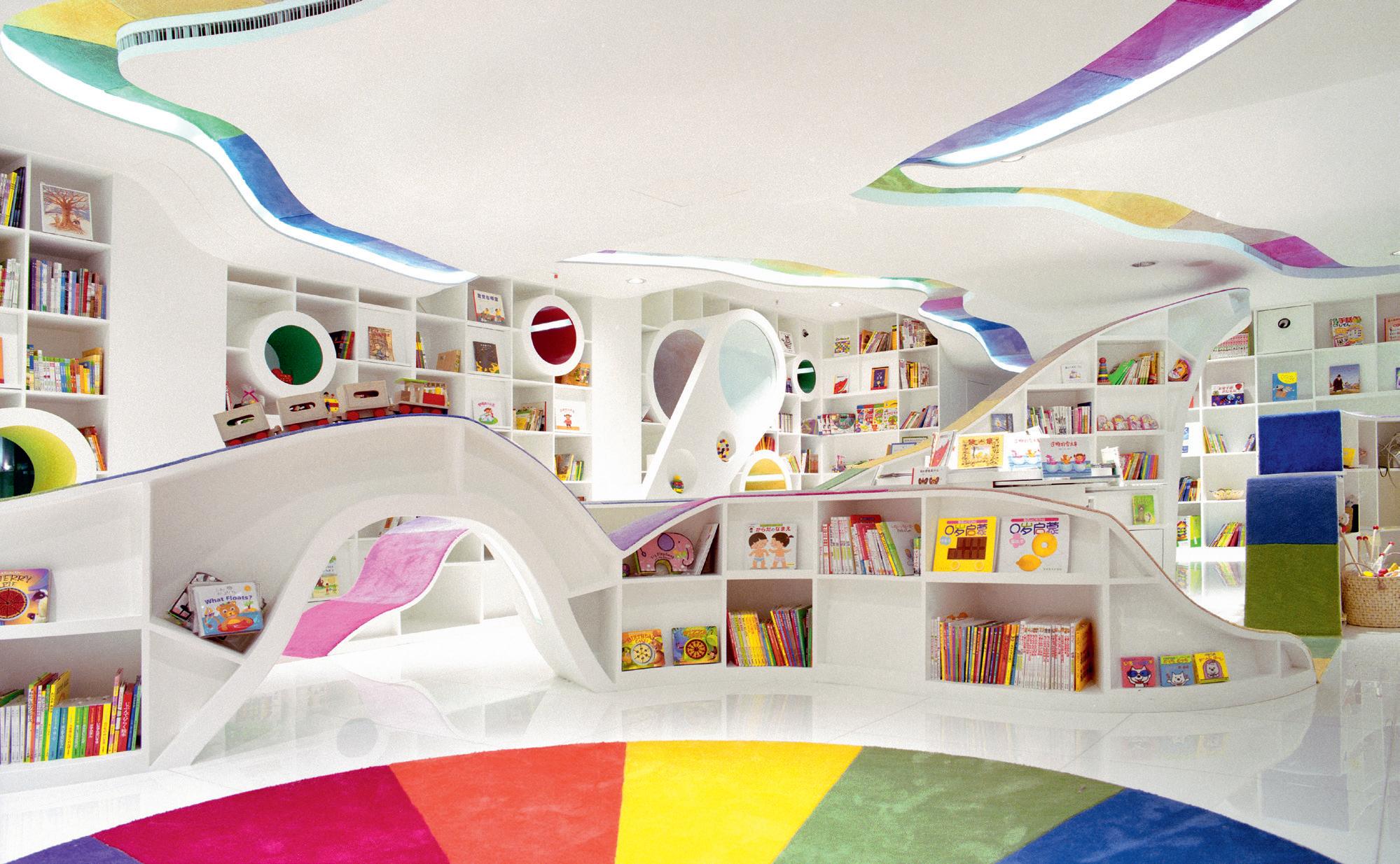

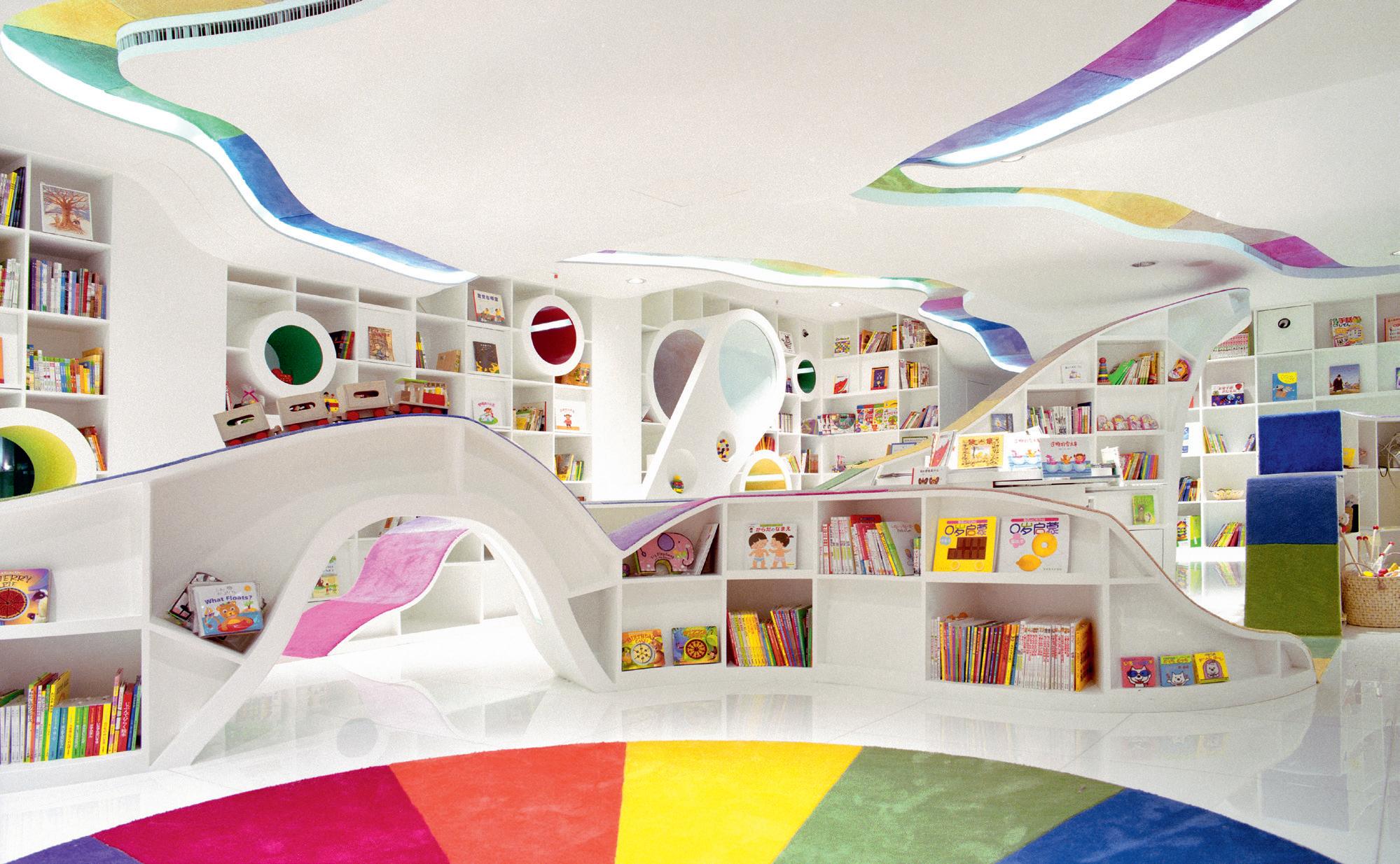

Beijing

This bookstore is an ode to joy the joy of reading and living. Its cheerful, harmonious colors evoke the pleasure and leisure associated with reading from childhood onward. This is a kid’s republic.

hues. As in Alice’s Wonderland, where rabbits talk and carry watches, the children who wander through Poplar Kid’s Republic forget the real world as they embark on an extraordinary adventure, drifting farther and farther away from adults. The permission to lie down wherever they wish, adopting the most comfortable position, must have surprised young Beijingers when the store first opened, but its popularity proves that they like the new freedom. Just

watching them, totally absorbed in what they’re reading, reveals Japan’s masterstroke in offering Beijing children open access to a freely chosen cultural pastime. Without acknowledging it, this bookstore is a synthesis of every experiment in children’s literature from Babar the Elephant and the Père Castor series in France to Mickey Mouse and cartoons in the United States, via innovative graphic design in Czechoslovakia and Russia in the interwar period.

For the original edition

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR: Geneviève Rudolf

PROOFREADER: Jean-Claude Baillieul

PHOTO RESEARCH: Salomé Perrineau

DESIGN AND LAYOUT: Bastien Forato

PRODUCTION: Luc Martin

PREPRESS: IGS, L’Isle-d’Espagnac

For the English-language edition

EDITORS: David Fabricant and Austin Allen

PROOFREADER: Bridget Manzella

TYPESETTER: Angela C. Taormina

PRODUCTION MANAGER: Louise Kurtz

The portions of the text by Jean-Yves Mollier were translated by Deke Dusinberre, and those by Patricia Sorel were translated by Charles Penwarden.

First published in English in 2025 by Abbeville Press, 655 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

First published in French in 2025 by Citadelles & Mazenod, 8, rue Gaston de Saint-Paul, 75116 Paris

Copyright © 2025 Editio–Citadelles & Mazenod. English translation copyright © 2025 Abbeville Press. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries should be addressed to Abbeville Press, 655 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017.

Printed and bound by Printer Trento SPA, Italy

First edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978-0-7892-1516-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request

For bulk and premium sales and for text adoption procedures, write to Customer Service Manager, Abbeville Press, 655 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, or call 1-800-A rtbook.

Visit Abbeville Press online at www.abbeville.com.