Preface Sarah Lombardi

Art Brut, Created Through a Thousand Faces Pascal Roman On Deciphering Appearance Marc Décimo

Preface Sarah Lombardi

Art Brut, Created Through a Thousand Faces Pascal Roman On Deciphering Appearance Marc Décimo

Heinrich Anton Müller

untitled, between 1917 and 1922 paint and chalk on wrapping paper 75 x 45 cm cab-A307

1 Georges Didi-Huberman, Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde (Paris: Minuit, 1992).

2 Franta, interview in Artension, no. 178 (March-April 2023): 49.

3 Lucienne Peiry, ‘Le Visage dans l’Art Brut. Autoportraits, identités retrouvées, identités refoulées’, in Laurent Guido et al. (ed.), Visages - Histoires, représentations, créations (Geneva: BHMS, 2017), 89–109.

4 Donald Woods Winnicott, ‘Le rôle de miroir de la mère et de la famille dans le développement de l’enfant’, in Jeu et réalité (1957; repr. Paris: Payot, 1975), 203–14.

Art Brut, created through a thousand faces. This title contains a double meaning: on the one hand, it refers to the inexhaustible richness of Art Brut works, ‘whose thousand faces’ display the variety, ingenuity, and freedom that constitute the true madness of Art Brut; and on the other, it hints at the multifariousness of the expressions on the faces, whatever their lineaments or colour, or the material they are made of. This is the assembly we are invited to join.

Encountering a face, in its various depictions, is an unsettling experience, which can be described by borrowing the title of one of Georges Didi-Huberman’s books, Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde (What we See Looks Back).1 For, although a face-to-face encounter places the self before an other, it also means engaging with oneself. Herein lies the challenge of an exhibition devoted to the face, owing to the unavoidable engagement with the part of oneself to be found in the works of Art Brut artists. This engagement obliges us to come to terms with these works: for, what touches us in a responsive encounter with a face, what moves us or leaves us indifferent, or even stuns or repels us, what thrills or frightens us, is this part of us, often unseen, which is brought out of mothballs and suddenly put in the limelight: a portion of our inner life on public display.

And if, as the painter Franta says,2 ‘painting is an invitation to connect’, then the encounter with the depiction of a face is a double invitation to connect: with the artist and with oneself. After all, portraying faces has an anthropological pedigree that transcends eras and continents, styles and schools, materials and techniques.

Lucienne Peiry3 wonders exactly what to make of all the faces that populate Art Brut works: viewing them as proper self-portraits, ‘inner mirrors’, as she puts it, frameworks around which to build an identity through the idea of the double it conjures up, opens up heuristic possibilities that can be extended beyond. Indeed, on another level, the repeated, even obsessive, depiction of faces can be understood as an attempt to bring about the emergence of a helpful figure, a support in establishing identity by seeking the other. Pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Woods Winnicott4 describes the key function of the first sight of the face of a mother/mother figure: the face is reflected in

Marcello Cammi untitled, 1994

red wine and ballpoint pen on wallpaper

11 8 x 8 6 cm cab-10847

< Linda Naeff untitled, 2012

acrylic paint and felt-tip pen on mat board

136 5 x 101 cm ni-9611

16 To paraphrase Georges Didi-Huberman in Ce que nous voyons.

17 Sigmund Freud, ‘Le délire et les rêves dans la Gradiva de W. Jensen’, in Œuvres ComplètesPsychanalyse-vol. VIII [1906–1908] (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2007), 39–126, 57.

18 Jacques Roman, Visage (Vevey: Éditions de l’Aire, 2023), 25.

all materials that may be used in the struggle between determined and undetermined form. Art Brut artists invite us to take an active approach to flushing out these ambushing faces, which surprise us and hold us in their power: ‘what we don’t always see, and is watching us’.16 It could also be said that these works take us back to a prefigurative time, when lines were drawn together to form images, in the encounter with form and matter, opening the way to representation, to the other, to the other in oneself, to oneself.

Marcello Cammi’s work exemplifies this emerging face. His works are produced on a variety of supports (cardboard printed on the reverse, sheets of paper glued to cardboard or to each other, pieces of wallpaper), and the faces emerge from a cluttered background: one makes them out, the outlines begin to take shape – figures of spirits attached to each other by the loose outline that unites them. In a way, they play with absence and presence, presence and absence, according to the engagement of the viewer who, as in a dream, builds what is missing, hallucinating.

The poet always says with greater eloquence17 what the words of the experts try, often clumsily, to explain; so he will have the last word regarding faces:

‘The face, in every encounter, makes us aware of the immediate, the time of all promises. Not passing time, but a time when, in the exchange, being is born into being. The stranger in our vicinity ceases to bring the night with him.18

Pascal Roman

Professor of clinical Psychology, PsychoPathology, and Psychoanalysis curator of the exhibition

Juva (Alfred Antonin Juritzky)

L’Erynnie, between 1948 and 1949

flint, paint, and wood

29 x 19.5 x 7.5 cm cab-A695

‘A poet must leave signs of his passing, not proof. Only signs make us dream.’

– René Char, La Parole en archipel, 1962.

Choosing the face as a metonym, at the expense of the rest of the body, makes it clear that it is not merely an anatomical support that can be reduced to bare essentials: hair, skull, forehead, eyebrows, eyelashes, eyes, nose, ears, mouth, chin, and skin. Preparing for this type of portrait follows in the footsteps of the physiognomonists of yore, who believed it best represented a totality that is undoubtedly more psychological than physical: that a face is inhabited by a subject whose morphological and expressive features can certainly be settled, but who slips out of focus if the portraitist sticks only to this mask. Capturing a physical likeness alone, as in the system developed in France by Alphonse Bertillon (1853–1914), can only really be of use for police identification purposes. All that was required in 1889 to establish a person’s identity by means of an anthropometric description were two mugshots – full face and profile – and the recording of a few distinctive features (height, eye colour, scars, etc.) followed by fingerprints for confirmation. Depicting a face is especially delicate, as a portrait never fixes more than a moment in time, and the face is by nature changeable, switching from one expression to another, betraying emotion or, on the contrary, hoodwinking others or remaining ambiguous. Since a face also exists only in relation to others, it is essential to go beyond the semiological aspect – what makes a sign, what makes sense – and the coded, socially shared expressions that can be immediately interpreted as such: anger, joy, sorrow, desire, and so on. What the portraitist, like the detective, is looking for, then, are clues, the details that seem to point from the outer towards the psychological inner, from appearance to depth. In this scrutinising dispositif (‘device’, in Foucault’s sense), a face is never assumed to be unambiguous but to carry hidden meanings that need to be deciphered. This means learning to read between the lines of a face the marks of character traits and the scars left by traumas. The physician, who is also in search of clues, does this. He calls them symptoms. He collects them and links them together (syndrome) so that they eventually make sense. He can then diagnose the disease. For the ‘alienists’ of the late nineteenth century, the focus was on the face. For example, after

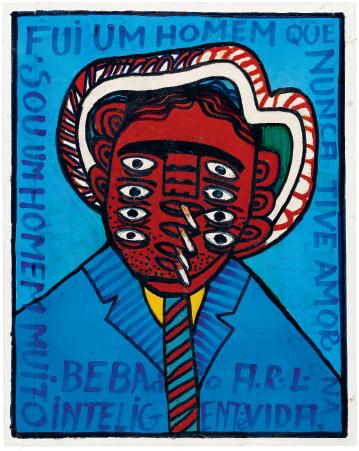

ARL (Antonio Roseno de Lima)

Bebado, s.d. undated

peinture et feutre sur bois aggloméré et cadre de bois paint and felt-tip pen on chipboard and wooden frame

49 x 39,5 x 2,4 cm cab-16242

ARL (Antonio Roseno de Lima) Moça, 1979

peinture, feutre et mine de plomb sur papier paint, felt-tip pen and graphite on paper

30 x 22 cm cab-16192

ARL (Antonio Roseno de Lima) Moça, 1979

peinture, feutre et mine de plomb sur papier paint, felt-tip pen and graphite on paper

30,3 x 22 cm cab-16193

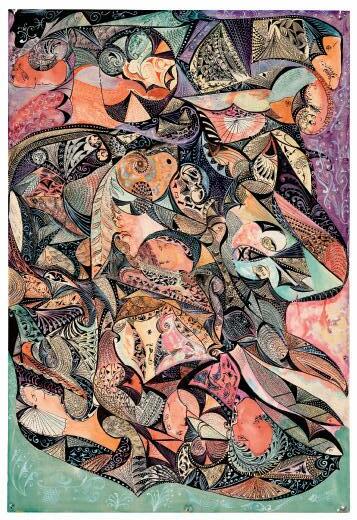

Emmanuel Derriennic

La création du monde, 1963

aquarelle et encre de Chine sur papier watercolour and India ink on paper

110 x 74 cm

cab-1223

Emmanuel Derriennic No 28, 1963

aquarelle et encre de Chine sur papier watercolour and India ink on paper

50 x 65,5 cm cab-1098

Duhem sans titre untitled, 1996 craie grasse et feutre sur papier crayon and felt-tip pen on paper

30,4 x 20,5 cm cab-11723

Paul Duhem sans titre untitled, 1993 peinture à l’huile sur papier oil paint on paper

40 x 30,5 cm cab-11953

Dominique Hérion sans titre untitled, entre between 1979 et and 1981 mine de plomb et crayon de couleur sur papier graphite and coloured pencil on paper 37 x 27,3 cm ni-3513

33 x 22 cm ni-3511

et and 1981

and 1988

titre untitled, juillet July 1946 encre sur papier ink

Scottie Wilson sans titre untitled, entre between 1938 et and 1940 encre, crayon de couleur et pastel sur papier collé sur carton ink, coloured pencil and pastel on paper glued to cardboard 51,2 x 28 cm cab-A318

Scottie Wilson sans titre untitled, entre between 1938 et and 1940 encre, crayon de couleur et pastel sur papier ink, coloured pencil and pastel on paper 54 x 28 cm cab-A720

All the photographs were provided by Atelier de numérisation, Ville de Lausanne: Charlotte Aebischer, Jean-Marie Almonte, Sarah Baehler, Pierre Battistolo, Christian Bérard, Amélie Blanc, Danielle Caputo, Julie Casolo, Arnaud Conne, Morgane Détraz, Garance Dupuis, Claudina Garcia, Marie Humair, Olivier Laffely, Giuseppe Pocetti, Margot Roth, Kevin Seisdedos, and Caroline Smyrliadis.

Except for the pages mentioned below:

pp. 10, 22, 97: Claude Bornand p. 26: Luc Chessex

coPyriGHts

Filippo Bentivegna: by permission of the Soprintendenza per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali di Agrigento

Merhdad Rashidi: courtesy of Henry Boxer Gallery Marie-Rose Lortet: © 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich

All rights reserved for the other artists.

Despite our efforts, we have been unable to establish copyright in certain cases. For any request, please contact the Collection de l’Art Brut.

This book has been published in connection with the exhibition Visages, 6e biennale de l’Art Brut, held at the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne, from 8 December 2023 to 28 April 2024.

exHiBitioN

GeNeral commissioNer

Sarah Lombardi Director, Collection de l’Art Brut

exHiBitioN commissioNer

Pascal Roman Professor of Clinical Psychology, Psychopathology and Psychoanalysis, University of Lausanne

coordiNatioN

Pauline Mack

collaBoratioN

Émilie Cleeremans and Juliette Mesple

tHe Book

editorial coordiNatioN

Pauline Mack

BioGraPHies

Pauline Mack and Émilie Cleeremans

BiBlioGraPHy

Vincent Monod

icoNoGraPHy

Sarah Lombardi, Pauline Mack, Vincent Monod

admiNistratioN

5 coNtiNeNts editioNs art directioN aNd GraPHic desiGN

Stefano Montagnana

editorial coordiNatioN

Aldo Carioli in collaboration with Lucia Moretti

traNslatioN

Julian Comoy

editiNG

Charles Gute

Pre-Press

Collection de l’Art Brut Av. des Bergières, 11 CH-1004 Lausanne www.artbrut.ch

All rights reserved – Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

For the present edition © Copyright 2023 5 Continents Editions srl

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Collection de l’Art Brut thanks Nicole Babilas, Henry Boxer (Henry Boxer Gallery), Josine Cardon Marchal, Luc Chessex, Mario Del Curto, Hélène Ferbos and Émilie Hervé (Musée de la Création Franche), Jean-Jacques Fleury, Bruno Gérard (Fondation Paul Duhem), Edward M. Gómez, Betty Legrand (La Clairière), Teresa Maranzano, Yutaka Miyawaki (Galerie Miyawaki), Jessica Mondego (La Ferme des Tilleuls), Giovanni Crisostomo Nucera, Manon Pélissier, Milo Petrovic, Pascal Rigeade, Vincenzo Rinaldi, Anne-Françoise Rouche (La « S » Grand Atelier), Isabelle Sanz Naeff, Tom Stanley, Claire Viallat-Patonnier.

Expressions of appreciation to Nicole Bayle, Ko¯mei Bekki, Christiane Chardon, Curzio Di Giovanni, Véronique Goffin, Dominique Hérion, Danielle Jacqui, Marie-Rose Lortet, Issei Nishimura and Junko Nishimura, Mehrdad Rashidi, Ody Saban, Shuzo Yoshida.

Expressions of gratitude are extended to the supporting partners: Fondation Guignard and Retraites populaires, as well as the Association des Amis de l’Art Brut.

5 Continents Editions

Piazza Caiazzo, 1 20124 Milan, Italy www.fivecontinentseditions.com

Distributed by ACC Art Books throughout the world, excluding Italy. Distributed in Italy and Switzerland by Messaggerie Libri S.p.A.

Printed in Italy in October 2023 by Tecnostampa - Pigini Group Printing Division, Loreto – Trevi, Italy for

Cover: reelaboration of a detail from the work by Heinrich Anton Müller published at page 10 of this book