By Klaus Honnef

Stahnsdorf South-Western Cemetery covers an area larger than 288 soccer fields. It ranks tenth among the world’s largest cemeteries, and within Germany it is the second-largest. The German past has shaped its history in ways that set it apart from all other cemeteries. It has done so from the day it opened in 1909, during imperial times, to the Nazi era, and all the way to the nation’s postwar partition and eventual reunification. Each of these eras massively intervened in the function, structure, and characteristics of what was originally the central cemetery of Berlin. It was affected by Albert Speer’s megalomaniac plans for the new German capital of Germania as much as by the later division of the country. That is because the site became part of East Germany after the collapse of the Nazi regime. As a result, it was entirely cut off from its West Berlin catchment areas that had been its lifeline, in a manner of speaking, even though it continued to serve as a burial ground. Although it did undergo a renaissance of sorts under the aegis of the Lutheran Church, it lost its former prominence as Berlin’s central cemetery.

Thus, the cemetery is not a tourist hotspot like Père Lachaise Cemetery on the east side of Paris. Then again, it is the resting place of many well-known persons, including— to name but three of the most celebrated artists—Friedrich Murnau, one of Germany’s cinematic pioneers, Heinrich Zille, the most stereotypical of Berlin’s artists, and Lovis Corinth, an extraordinary painter whose work has tremendously gained in recognition in the recent past. There is no shortage of landmark examples of sepulchral culture, including the cemetery chapel built of timber and a spectacular tomb sculpture by Otto Freundlich.

It was the sight of seemingly quotidian things that unexpectedly captivated the photographer

Anke Krey when she visited what seemed like a literal iteration of the term “memorial park.” Perhaps because what she saw was not what she had expected to see at a cemetery. Yet the sight proved inspirational to a degree that made her turn back to free artistic photography, years after she had successfully completed a degree program in photography, had won her first reassuring awards, and had subsequently practiced photography as a profession. “A 100-meter length of unrolled water hose concealed in the undergrowth and a junction box in the forest were clear signs of life hidden inside this ‘garden of the dead’.” Up to that point, being confronted with the graveyard had probably triggered but vague associations of the sort that haunt the minds of most people when faced with death and the deceased.

Today’s affluent societies have gradually eliminated death from the lives of people, causing the cemetery to lose its privileged status as man’s final resting place and as an eminent cultural institution. Just half a century ago, the French historian Philippe Ariès drafted his voluminous monograph about death and cemeteries, exhaustively discussing the significance of the institution in culturalhistorical and socio-psychological terms, only to have the filmmaker and writer Woody Allen quip about death a few decades later that he would not want to be there when it happens. Death has vacated the center of human existence and moved to its periphery. In many people, it inspires nothing but fear.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, the garden hose and junction box prompted Anke Krey to choose another type of approach to the cemetery subject than the common dreadfilled view. Motivated by an entirely different interest and a baffling point of view. Following

the chance discovery of the implements, she started exploring the rationale behind her slightly obscured finds in the lush verdure. Eventually, she came upon twenty employees of the Lutheran cemetery administration. As they warmed to each other right away, the conversation produced a number of insights she had not remotely associated with the context of a burial ground. She ended up accompanying the men and women with her camera for two years, 2016 through 2018. In her apposite images, she documented the fact that a cemetery is not just a burial site, but rather an extremely vibrant organism of complex and multiple decisions and processes that work hand in glove.

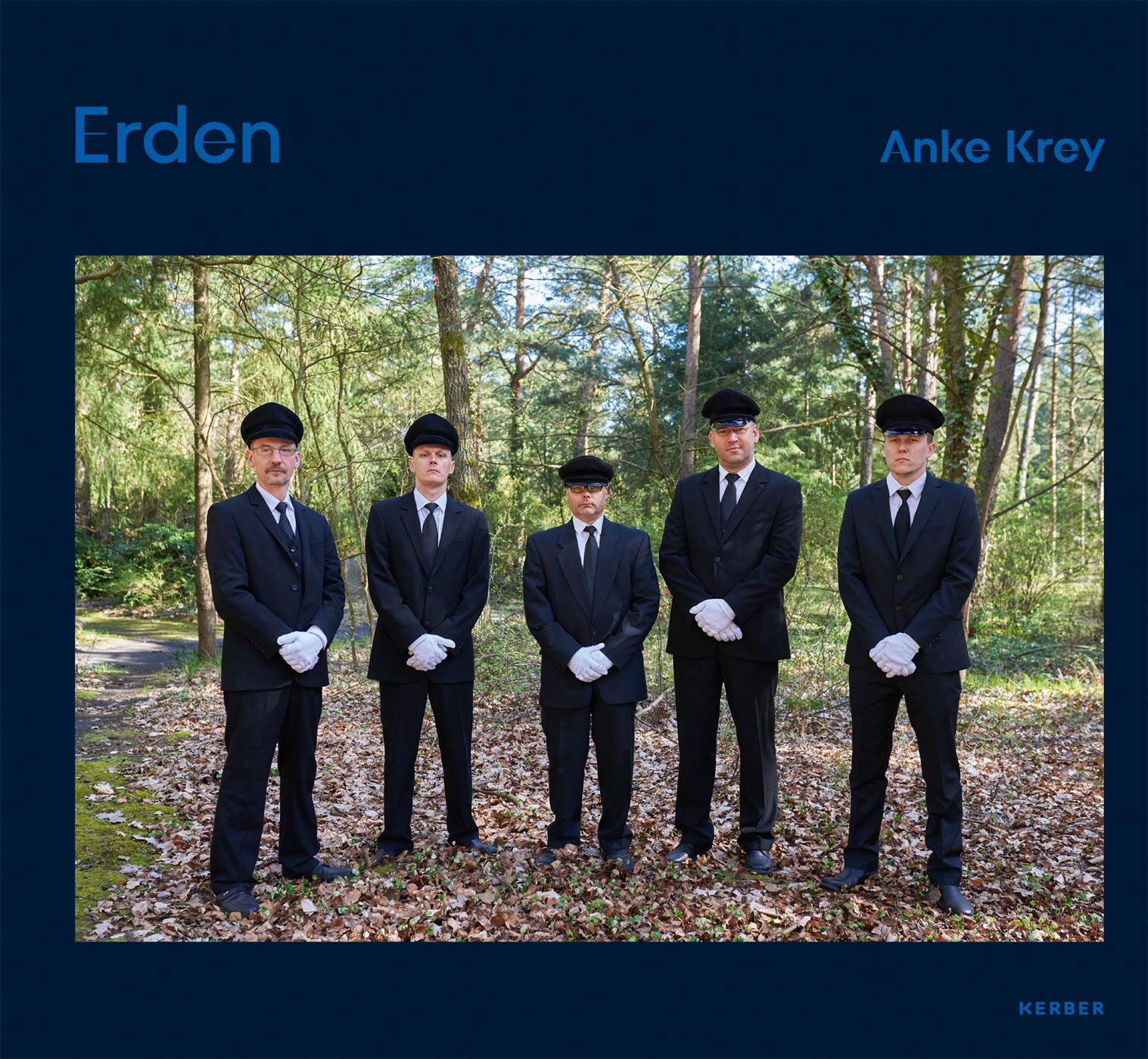

“Erden” is the title she chose for her amazingly plausible account of cemetery care in more than sixty colour images. She borrowed the term from the specific vocabulary of the cemetery workers. While literally implying a casket burial, its verbal form means to excavate, to dig or to bury—verbs designating the activities the workers are expected to perform. The purpose of the workers’ special jargon is to protect them from the explicit signifiers by overwriting them metaphorically.

In her images, Anke Krey unleashes the virtually endless possibilities of modern documentary photography, which has abandoned the painterly practice of visualizing in a single image an object with its diverse characteristics, meanings, angles, and effective impulses. Instead, it distributes the various aspects of a demanding subject matter across a wider range of images, much like films or cartoons do. The images circle, in a manner of speaking, around the core of their thematic challenge like the planets around the sun, bringing out its proper and therefore valid shape through a system of perpetually interweaving relations.

This presupposes that the images, despite their differences in motif, framing, and settings, share a common theme, picking up on their relationship to the other images and using their messages to keep supplementing, expanding, or refocusing the visual context. It is a documentary feat that “Erden” convincingly accomplishes. However, unlike motion pictures, it leaves it up to the beholder to draw his or her own relational lines.

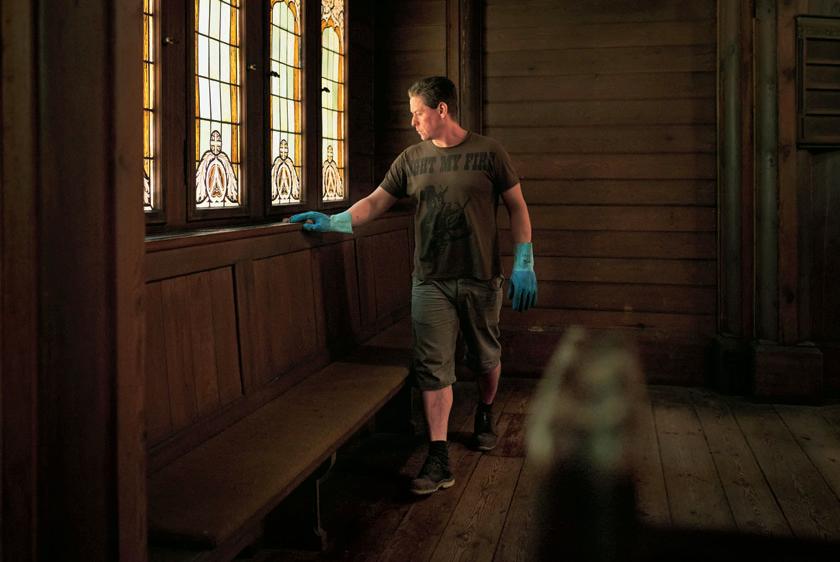

Using the example of Berlin’s former central cemetery, Anke Krey outlines an autonomous cosmos in her mosaic of images. At the same time, each of her pictures retains its intrinsic aesthetic weight. For instance, she portrays the cemetery workers in various functional roles. Several times a day, the six undertakers in their dark suits and peaked caps transform into foresters, animal carers, and conservationists—in a literal physical sense. Another group of workers excavates pits for the coffins, sometimes digging in sync. Yet another one trims the lawn areas or prepares the wooden cemetery chapel for the funeral service. The workers ensure that the chapel looks pictureperfect, even wiping down the benches beneath the splendid Art Nouveau windows. They arrange flowers and wreaths on the grave sites. Baskets of blossoms are on hand to bid the dead a final farewell. A small snack from the lunch box in between, when changing outfits, is as much a part of it all as the careful shining of shoes before the next ceremony.

Not least, it is the cemetery workers’ job to keep the vegetation in check, which used the times of neglect to reclaim much of the terrain. They trim trees, remove dead branches, sweep up woody debris and burn it. Without their efforts, nature would concurrently destroy the encroachments of civilization

and reverse the changes it has wrought. Indeed, some images convey the impression of a densely overgrown and carefully groomed woodland with mossy aisles that happens to double as a cemetery. The sepulchral artifacts, some of them dilapidated, demand just as much of the workers’ attention.

Anke Krey devoted only a few pictures to the funeral processions in which morticians take the deceased to their final places of rest, her images covering summer, autumn, and winter. The photographer’s subtle visual direction cultivates a calibrated detachment. At the same time, it reveals that hosting the funeral procession represents but one of many tasks the cemetery staff perform. Only to the outside observer does it appear to be the most prominent one. A number of still life photographs—white gloves on a parapet, large coffee pots on a table, and enormous file cabinets—point to a wide variety of other tasks. A fleeting glance captures the pastoral worker, getting dressed for the funeral ceremony. Notwithstanding the more than sixty visual takes that range from panoramic views to close-ups, the mosaic of images provides a marvelous account of man and nature in harmony. And suddenly I am reminded of Georges Bataille’s observation that each life is the product of a thousand deaths.