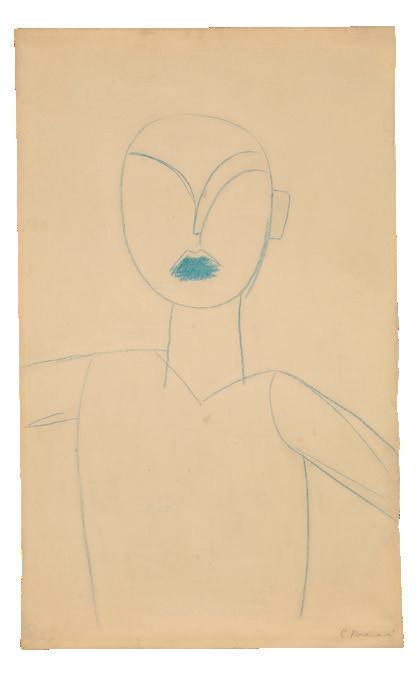

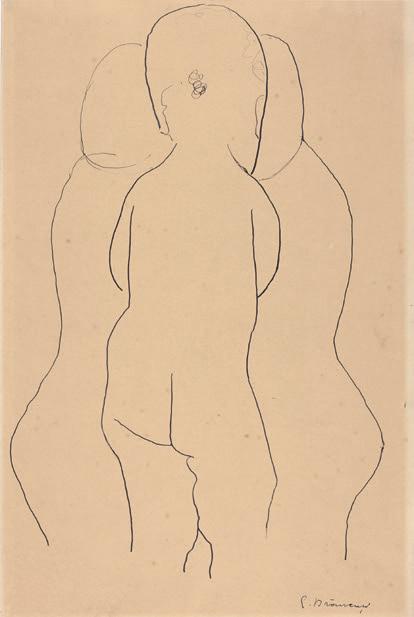

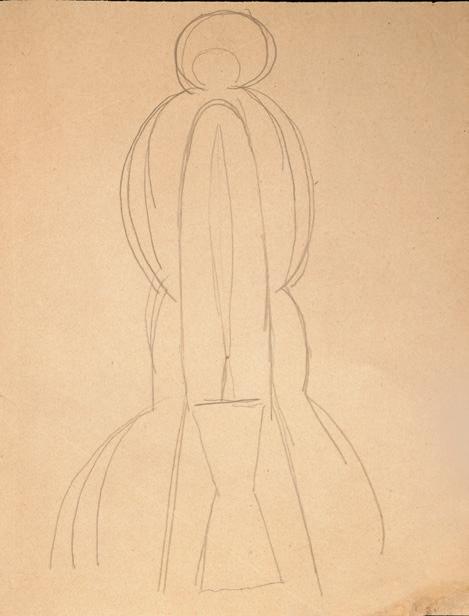

Study for The First Step, ca. 1913

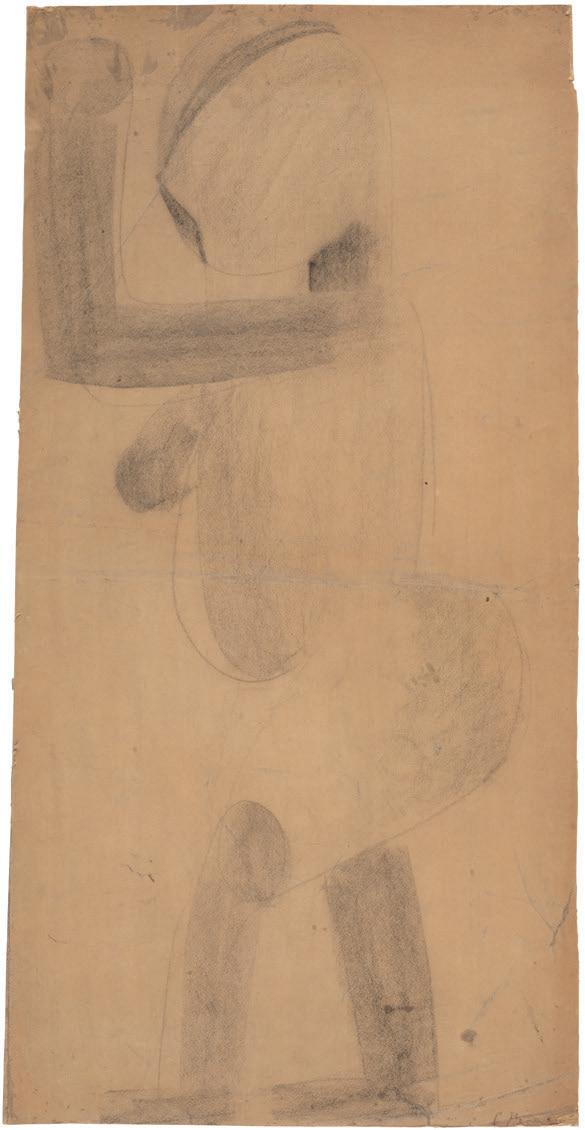

Study for The First Step, ca. 1913

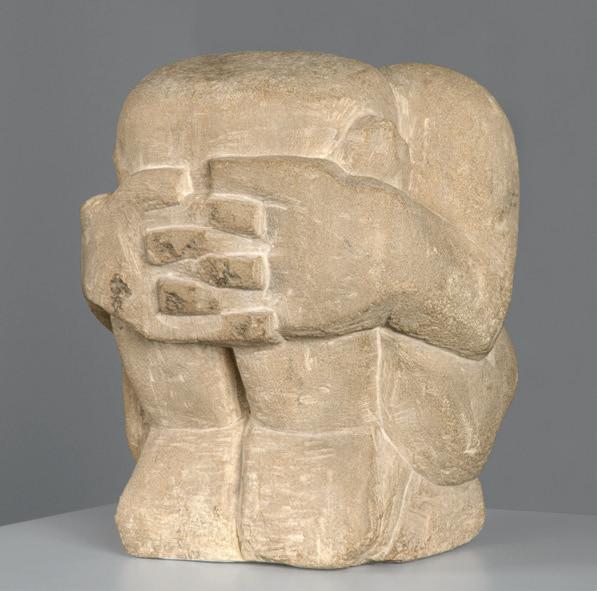

Among the modern artists in Paris who increasingly engaged with African art from 1905 onwards, Brancusi seems to have been the one with the greatest affinity for African sculpture. There are many similarities between the sculptor’s works and the major art forms of sub-Saharan Africa, whether masks or statuary, that point to intriguing convergences, such as segmented construction, which among the Yoruba people of Nigeria stems from a vision of the social world as composed of elements that are both independent and connected, fostering solidarity and individualism. Correspondences may also be found in the rejection of naturalism, the use of freestanding objects, vertical momentum, the symbolic proportions of different body parts (elongation of the neck and torso, shortening of the legs), the stylization of details, the principle of symmetry and frontality, and the rhythmic musicality of volumes.

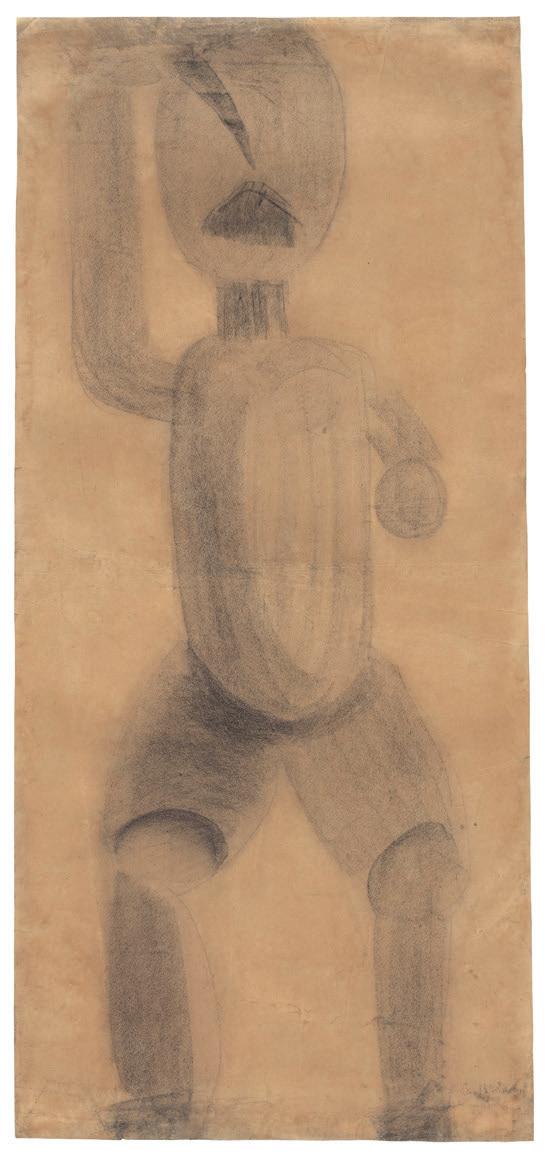

The sculpture Maiastra (1911) illustrates this uncanny dialogue. It closely resembles the motif of a Guro (Kweni) horned mask from Ivory Coast, in which a rounded forehead overhangs the triangular face and the mouth merges with the chin—the latter a device also used by Fang sculptors in Gabon and Equatorial Guinea. Are these references or convergences? The artist’s apparent closeness to certain African practices can perhaps be explained by his experience sculpting in wood and his natural sympathy with African wooden artworks, as illustrated by Portrait of Mme L. R. (1914–17), which rejects naturalistic representation in order to capture the spiritual essence of the subject; the face is similar to the elliptical construction of a Mahongwe reliquary from Gabon,1 or a statue from Mali by the Dogon artist known as the Master of Ogol.2 The morphology of the figure in Le Premier Pas, Brancusi’s first wooden sculpture, exhibited in New York in 1914 and then destroyed by the artist, who kept only the head, resonates directly with a pair of Bamana statues from Mali published by

Marius de Zayas in 1916.3 In many African cultures, trees are considered living entities that may harbor benevolent or fearsome spirits. A piece of carved wood will retain this original spiritual imprint, augmented by a new status as a repository for an ancestral spirit or a supernatural force. Such notions seem to have been intuitive for Brancusi, who came from a region of forests where people observed a cult of the dead, who were commemorated, as in East Africa and Madagascar, by the use of funerary posts. Exposure to African art invigorated the avantgarde of intellectuals, artists, and collectors in Paris between 1905 and 1920, following in the footsteps of Maurice de Vlaminck and André Derain. They enthusiastically sought out and surrounded themselves with African objects, initiating a revolution in how we look at art. Their receptiveness to new sculptural modes seems to have prompted some of them to think more analytically, beyond the myth of “primitive spontaneity.” Brancusi’s rigorous attention to direct learning from a work of art, calling to mind the African tradition in which an apprentice is made to spend long periods in silent observation, opened up a space rich in polysemous inspirations, drawing on several sources to attain the universal.

1

Musée du quai Branly –Jacques Chirac, Paris, inv. no. 71.1886.77.2.

2

Musée du quai Branly –Jacques Chirac, Paris, inv. no. 71.1935.60.371.

3

Musée du quai Branly –Jacques Chirac, Paris, inv. no. 71.1896.6.1 and 71.1896.6.2.

Male Statue, Bamana, Mali, 19th century Wood, 65.5 × 14.5 × 11.8 cm Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris, 71.1896.6.1

Study in Profile, [1913] Charcoal on beige paper, 74.5 × 38 cm Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, AM 3771 D

Study related to The First Step, 1913 Pencil on paper, 82.1 × 38 cm The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Benjamin Scharps and David Scharps Fund, 1956 1.1956

“This is my last will and testament, which revokes all previous dispositions.

I institute Mr. and Mrs. Alexandre Istrati, residing at 11 impasse Ronsin, Paris, jointly as my sole legatees. [. . .] I bequeath to the French State, for the Musée national d’art moderne, absolutely everything contained on the day of my death in my studios located in Paris, number 11 impasse Ronsin, with the exception of any cash, securities, or valuables that may be found there, which will pass to my sole legatees.

This bequest is made on condition that the French State reconstruct, preferably on the premises of the Musée national d’art moderne, a studio containing my works, sketches, workbenches, tools, and furniture. In the event of one or more of my works having been removed from my studios for an exhibition or for any other reason, I intend that they be included in the present bequest.

I appoint Doctor Pasco Athanassiou, residing in Paris at the Institut Pasteur, as my executor.

My executor’s duties will include collaborating with the Musée d’art moderne to reconstruct the studio and distribute the bequeathed works within it.

Paris, April 12, 1956.”

Archives of the Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris

In the 1920s Brancusi had a female dog named Polaire, a Samoyed whose immaculate coat gave her the appearance of a sculpture among sculptures in the white-dusted studio. Polaire was hit by a car and killed in 1925. The sculptor never had another dog, but he often evoked her memory. There are few mammals in Brancusi’s bestiary, except perhaps Watchdog (ca. 1917), more inspired by architectural metopes than by the morphology of a pointer, of which the sculptor only retained its angular position. Penguins, fish, roosters, birds, seals, swans, turtles— two groups can be distinguished in this eccentric typology, at once exotic and prosaic, at any rate completely out of step with the canons of modern sculpture (a distant prefiguration can perhaps be seen in Giambologna’s Turkey, from the Mannerist period): birds on the one hand, aquatic animals on the other. (A possible exception is Nocturnal Animal, a maple wood sculpture from 1930, which was to remain a unicum in the Brancusian corpus.) Brancusi created multiple versions of his animals over the

Brancusi sitting at the foot of Endless Column at Voulangis with Steichen’s dog, Stoor, summer 1926

Gelatin silver print, 11.9 × 13.6 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, PH 530 A

course of his work (some thirty versions for Bird in Space), adopting different materials—marble, plaster, wood, or bronze—and modifying their dimensions so that the sculptures seem to respond less to a principle of singularity than to the naturalistic principle of the species, gradually transforming the studio into an aquarium or aviary. But the incessant repetition of the same animal motifs was also driven by a desire for purity, as Brancusi sought to isolate the dynamic curve of movement in the figure of the fish or bird.

As Christian Zervos pointed out, this process of stylization is less a search for abstraction than an affirmation of the vitalist powers of form, according to which the animal takes on a kind of textural and plastic self-evidence in metal or stone.1 James Johnson Sweeney described this in a striking phrase: “Not a copy of a seal in marble—nor a marble seal, but a seal-marble.”2 The animal, then, is not the terminus ad quem of the sculpture but its terminus a quo: not what it tends towards, driven by a concern for resemblance, but what it proceeds from and, to a certain extent, has freed itself from. In 1912, visiting the Salon de la locomotion aérienne with Marcel Duchamp and Fernand Léger, Brancusi raved about the shape of a propeller, a perfect match of form and function that can be seen again in the helical form

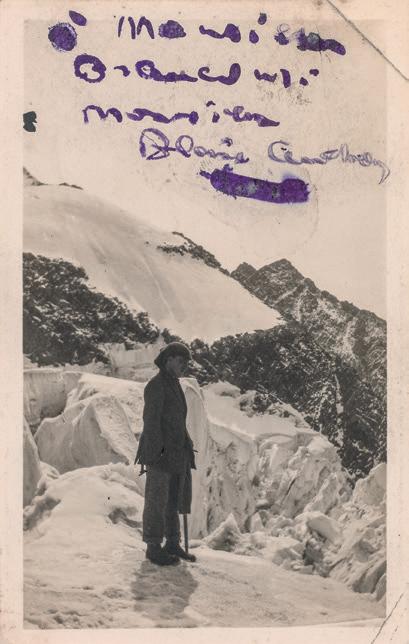

Blaise Cendrars in the Mont-Blanc massif

(at Les Grands Mulets, seracs of the Bossons Glacier?), summer 1919/1920

Signed photograph, dedicated to Brancusi

Gelatin silver print, 11.1 × 7 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, PH 1209 A

Photo: Anonymous

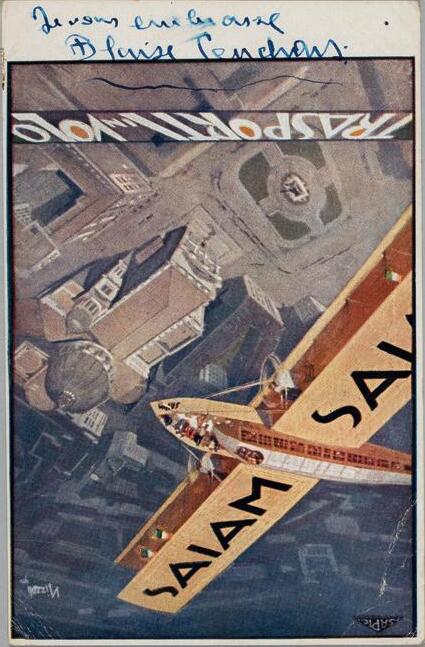

Postcard from Blaise and Raymonde Cendrars to Brancusi, sent from Rome, date unknown

Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris, Fonds Brancusi, BRAN 2

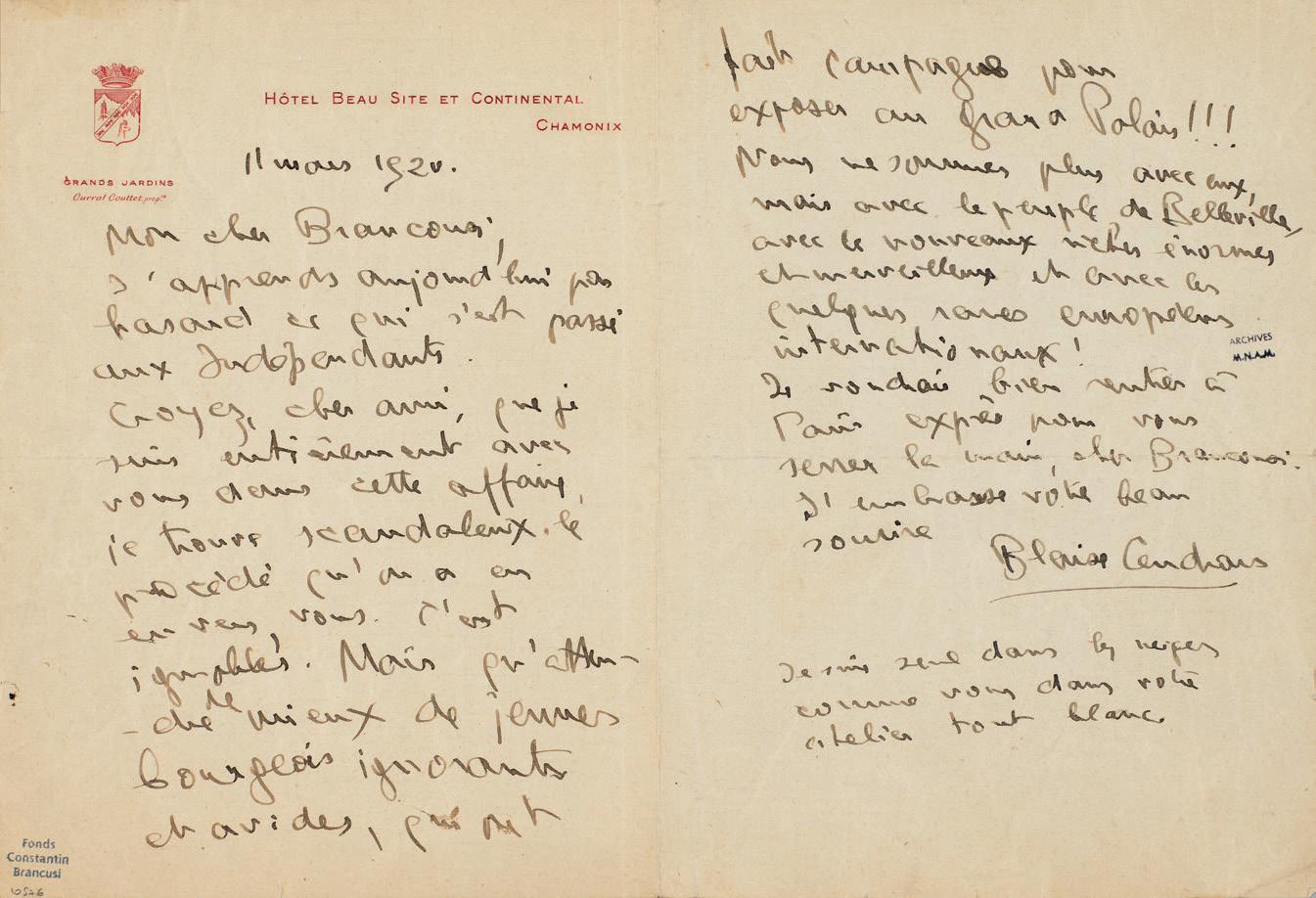

Letter from Blaise Cendrars to Brancusi regarding the Princess X scandal at the Salon des Indépendants, March 11, 1920

Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris, Fonds Brancusi, BRAN 2

1 Constantin Brancusi, “Aphorismes,” trans. Herschel B. Chipp, in This Quarter, 1, no. 1 (Spring 1925), p. 236, quoted in Herschel B. Chipp, Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968, p. 364.

2

Brancusi quoted in Pontus Hultén, Natalia Dumitresco, and Alexandre Istrati, Brancusi, Paris: Flammarion, 1986, p. 100.

“ When we are no longer children, we are already dead.”1

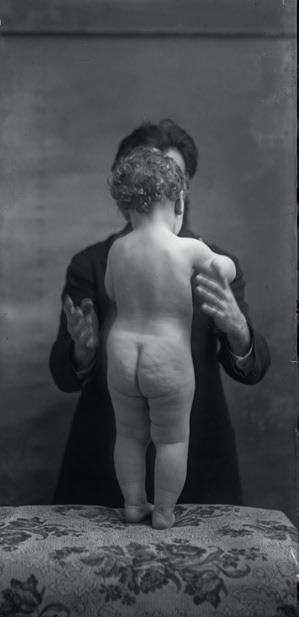

Bust of a Child, Head of a Sleeping Child, The First Step, The First Cry, Newborn, Beginning of the World: Many of Brancusi’s works relate to the theme of childhood and, beyond that, to the search for origins. Portraits of children were an important part of his creative output around 1906–10, inspired perhaps by Medardo Rosso’s sculptures or contact with his friends’ children, such as little George Farquhar (b. 1910), or his goddaughter Alicia Poiană (b. 1906). Taking a photo of George as its starting point, a 1911 drawing shows his outline in triplicate, in profile and from behind, evoking the rhythm of Rodin’s Three Shades (1886). The series Head of a Sleeping Child coincides with Brancusi’s shift from naturalism to a form of radical stylization marked by fragmentation (the bust becomes a head), with the figure tipped horizontally (a natural position for a baby) and the facial features reduced to a few lines on an oval volume. The child’s portrait turns into an egg or a cell, a metaphor at once for birth and the renewal of forms. Brancusi seems to explore this divergence in a photograph taken in around 1923 (PH 252C), in which he puts a 1906 Head of a Child, one of his modeled works, next to the plaster Newborn. In the latter, the mouth is inordinately wide, inscribing a curve that is interrupted by the projecting tongue. The mischievous grimace produces an expression that is full of feeling. “ What do you see when you look at a newborn? A mouth, wide open and gasping for air. [. . .] Newborns come into the world angry because they are brought into it against their will.”2 A. C.

Head of a Sleeping Child, colored plaster (1906–7), Newborn II, plaster? (before 1923), ca. 1923

Gelatin silver print, 23.9 × 29.9 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, PH 252 C

Portrait of George Farquhar as a baby, 1911

Gelatin silver negative on glass plate, 17.8 × 8.2 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, PH 806

Three Children, date unknown

Pen and black ink on cream wove card, discolored to tan, 47.6 × 321 cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Gift of Robert Allerton, 1924.930

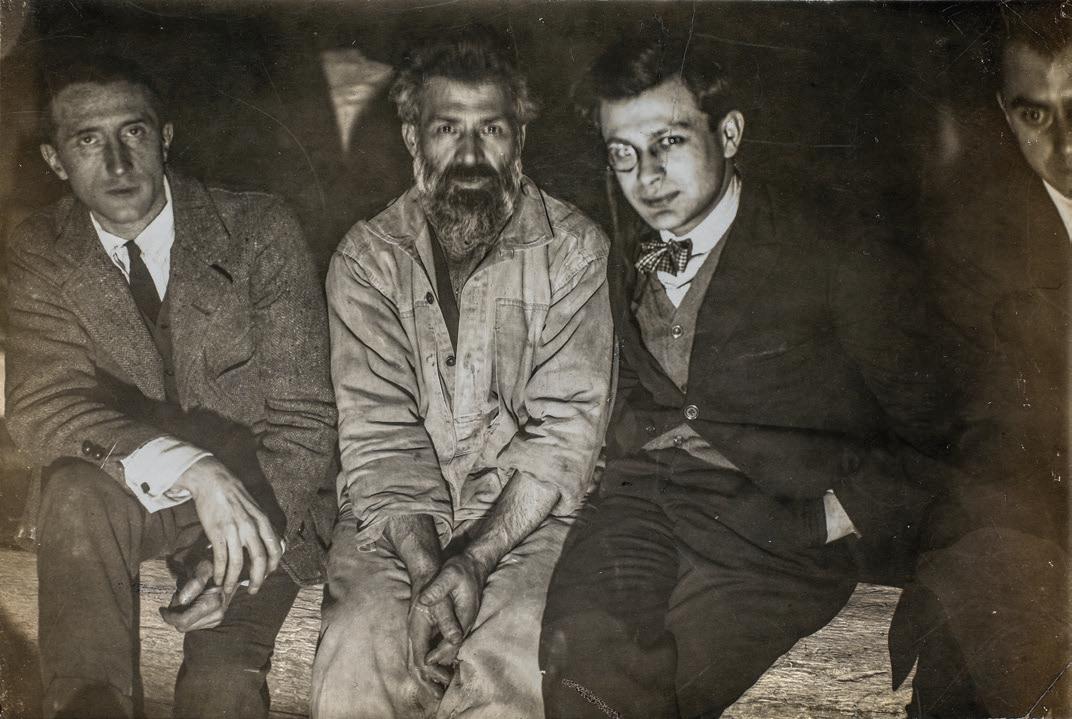

Marcel Duchamp, Brancusi, Tristan Tzara, and Man Ray in the studio, 1921

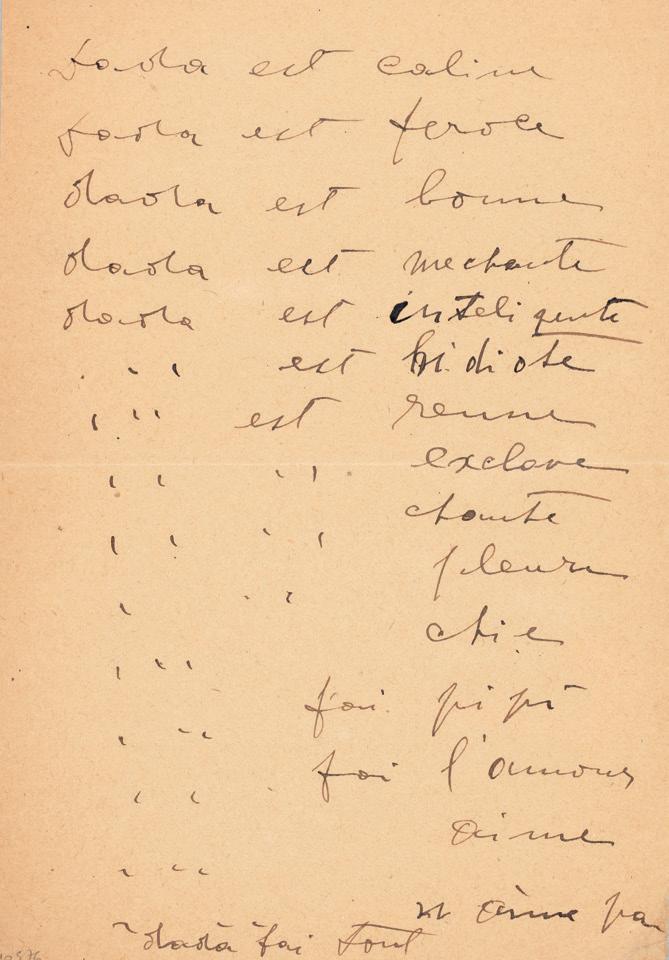

Gelatin silver print, 12 × 17.8 cm Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, PH 925 A Brancusi’s aphorism on Dada, date unknown Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris, Fonds Brancusi, BRAN 48

Dada is cuddly

Dada is fierce

Dada is good

Dada is mean

Dada is smart

Dada is silly

Dada is queen

Dada is a slave

Dada sings

Dada cries

Dada shits

Dada pees

Dada makes love

Dada loves

Dada dislikes

Dada does everything

Danaïde, ca. 1913

Bronze with black patina, 26.5 × 17 × 14 cm

Pedestal: stone (limestone), 21 × 22 × 22.5 cm

Kunst Museum Winterthur, Winterthur, Purchase, 1951, KV 805

Danaïde, 1913

Black patinated bronze (with gold-leaf gilding), 27.5 × 18 × 20.3 cm

Pedestal: AM 4002-48 (1); stone (limestone), 11.5 × 14 × 13.5 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, AM 4002-48

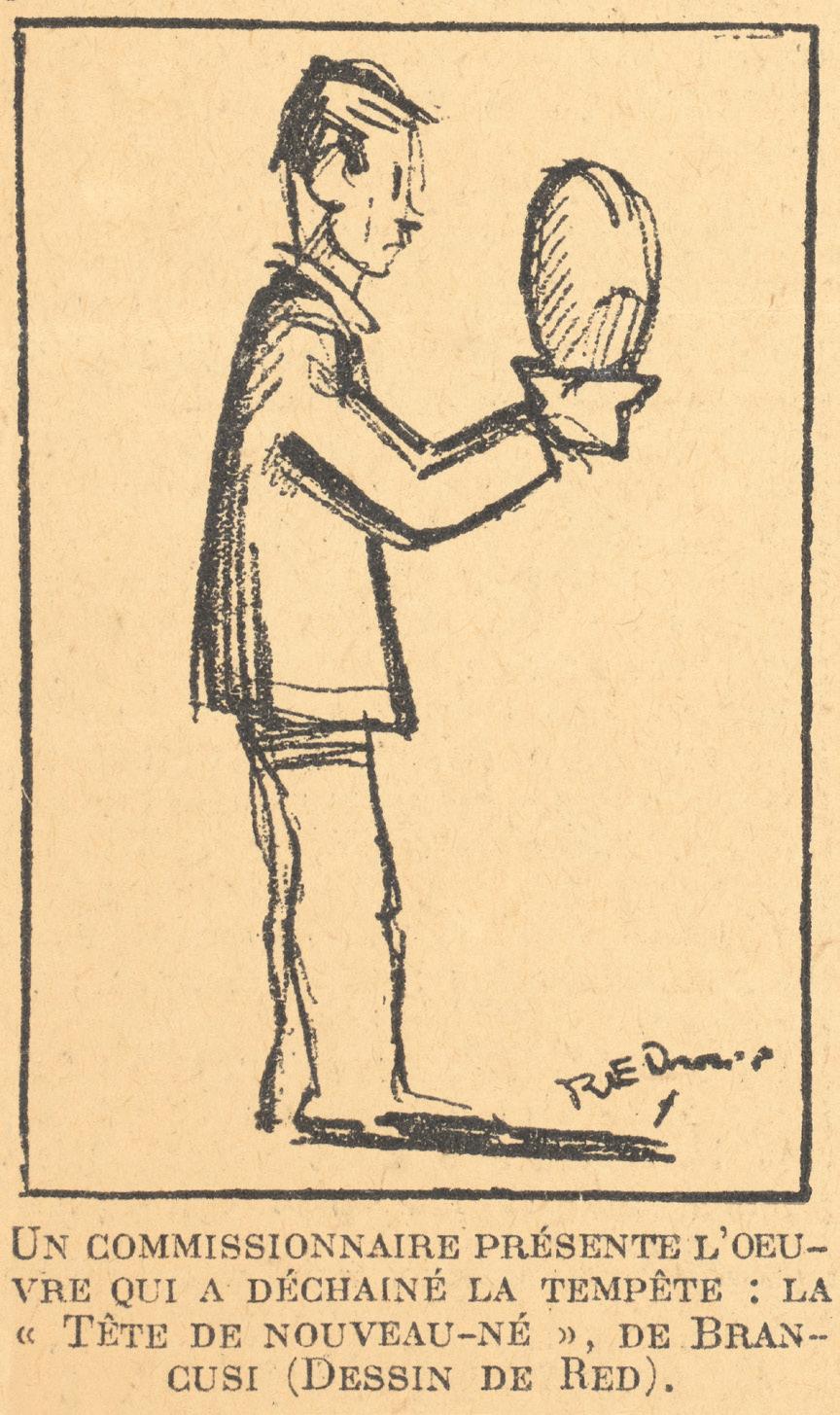

Cartoon by Red published in the journal Excelsior, October 30, 1926, p. 1

Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris, Fonds Brancusi, BRAN 53

Cartoon by Ralph Barton published in the New Yorker, February 20, 1926, p. 20 (“Heroes of the Week”)

Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris, BRAN 53

Far from being incomprehensible like Marcel Duchamp’s painting Nude Descending a Staircase (1912), Brancusi’s sculpture at the Armory Show in 1913 was mocked in the popular press because the simple forms could not only be easily read but could lead to laughable interpretations. The plaster Mlle Pogany I, a work also disseminated as a postcard, was derided as the “egg-shaped lady.”1

Gestalt psychology explores the mechanism involved in this form of perception, concluding that the human brain makes sense of the outside world by looking for simple shapes and imposing them on a form, even where none was intended. The fact that Brancusi was not thinking of an egg when he created his sculpture becomes irrelevant as the egg shape, once grasped, and discussed as it was in the press, becomes very difficult to undo. Unfortunately for Brancusi, this “egg” designation came to dominate the reception of his work to such an extent that he and his loyal critics were obliged to account for it when describing his work.

In a positive review of Brancusi’s first one-man show in 1914, at Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery in New York, the journalist Charles H. Caffin addresses at the outset the “egg-shaped lady” jokes and notes that the public at the Armory Show had only seen plasters of Brancusi’s art and not the refined, finished works in marble and bronze. Caffin is able to understand this form of sculpture, “purely abstract in expression,” by comparing it to ancient Egyptian and Chinese Song dynasty art and draws on a highly Symbolist language to describe the ideas that the Sleeping Muse evokes, ending his account: “when you accept its language, [this art] is exquisitely, poignantly beautiful.”2 This last remark takes us to the heart of the question. Brancusi’s sculptures

1 Mlle Pogany I and A Muse were among the postcards on sale at the exhibition. See the Walt Kuhn Papers on the Smithsonian’s dedicated website for the exhibition: www.si.edu/object/ walt-kuhn-scrapbook-pressclippings-documentingarmory-show-vol2:AAADCD_item_14643, accessed March 11, 2024.

2 Charles H. Caffin in the New York American, repr. in Camera Work, 45 (June 1914), p. 26.

3 Francis Picabia, untitled text in 291, 12 (February 1916), n.p. [p. 3].

4

Robert J. Coady, “American Art,” in The Soil, 1, no. 1 (December 1916), pp. 3–4, available at www.jstor.org/ stable/20542230.

5

Robert J. Coady, “Invention – Nativity by A. Chicken. Cluck, Cluck. A. Chicken,” in The Soil, 1, no. 2 (January 1917), n.p., available at www. jstor.org/stable/20542271.

6

Ezra Pound, “Brancusi,” in The Little Review, vol. 8 (Autumn 1921), available at https://modjourn.org/journal/ little-review.

7

For Everets, see Douglas Mao, Solid Objects: Modernism and the Test of Production, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998, p. 149.

did not conform to the kind of visual language based on naturalistic resemblance that the general public expected. In an article in Stieglitz’s journal 291, Francis Picabia explained that one had to shed the convention of “absolute realities” in order to understand this new art form, which was based on subjective experience: “it is necessary to let our imagination give a form to the metaphysical and invisible world.”3 However, the reach of such explanations was limited.

The critic and dealer Robert J. Coady denounced abstract art in his magazine The Soil, berating it as studio tomfoolery or absurd ideas imported from foreign parts that had no place in an America, whose art was “young, robust, energetic, naive, immature, daring and big spirited.”4 In 1917 Coady published a scathing parody of Brancusi’s art in the form of a photograph depicting an egg in chiaroscuro, captioned “Invention—Nativity” and signed “A. Chicken. Cluck, Cluck.”5 Coady had identified a cultural divide in America around the reception of abstract art, and he had chosen his side.

More surprising is the case of Ezra Pound, who was at the forefront of Imagist poetry and had participated in Vorticism. It is astonishing to see him also use the term “egg” to describe Brancusi’s sculpture in his groundbreaking essay in The Little Review in 1921, where the terms “egg” and “ovoid” are used to describe both Mlle Pogany II and Head of a Newborn, concluding that the ovoid is the “master-key” to the “world of form.”6 Indeed, to understand Pound’s text we must not lose sight of this term “form,” which guides the entire text: he cites at the beginning a line from T. J. Everets, “A work of art has in it no idea which is separable from the form,”7 declaring it to be the “best summary of our contemporary aesthetics.”8 He then applies this criterion to compare Brancusi’s work to the sculpture of his deceased friend the Vorticist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska: “Where Gaudier developed a sort of form-fugue or form-sonata by a combination of forms, Brancusi has set out on the maddeningly more difficult exploration toward getting all the forms into one form.”9 Alas for Brancusi, that “egg” label would stick, becoming for many the idea governing all his output.

8 Pound, “Brancusi,” p. 3.

9 Ibid., p. 4. Following Gaudier-Brzeska’s death, Pound had written Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir, London: John Lane, 1916.

10 Henri-Pierre Roché, letter to John Quinn, May 14, 1922, John Quinn Papers, MssCol 2513, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library.

We know that Pound’s essay failed to impress Brancusi, who had generously contributed twenty-four photographs to the journal. According to a letter from Henri-Pierre Roché to the collector John Quinn in May 1922, Brancusi referred to Pound’s article as his bête noire 10 Roché also reports that Brancusi much preferred Jeanne Robert Foster’s account of his work, which had appeared in Vanity Fair, where she views the fragmentary aspect of Brancusi’s sculpture not in terms of shape but as a form caught in the

A number of Brancusi’s sculptures were inspired by female models. Starting with realistic drawings, he gradually transformed these forms into refined objects: he elongated the faces, played with the transparency of the marble, and reduced the features until only simple lines remained, removing any element that might be associated with a body (a neck, a bust). In early 1910 he drew a series of Women with a Chignon, probably portraits of Marie Bonaparte, which resembled the first versions in stone (PH 407 and others) that would become Princess X. In his portraits, Brancusi rejected any physical similarity to the people depicted, endeavoring instead to show what he called “reality”—that is, “the essence of things” or of a personality. Thus, for Brancusi, his Portrait of Mrs. Eugene Meyer Jr. is what a portrait of her would really look like, not a posed, realistic portrait like the one Charles Despiau made of her in the same period. For the portraits of Mlle Pogany, he did some preliminary realistic tests in clay, which he destroyed in favor of an initial version in marble, dated 1912, which critics compared to “a hard-boiled egg on a sugar lump,” with a “beak” of a nose. Margit Pogany painted a self-portrait showing herself in the same pose, with her hand on her cheek, shadows round her eyes, and her hair pulled back. In 1931 she sent a photograph to Brancusi, who, most likely inspired by the painting, produced a third, more elongated and angular version the same year. V. L.

Head of a Woman, [ca. 1908]

Plaster, 30.5 × 16.5 × 15.5 cm

Pedestal (3 elements): AM 4002-35 (1); AM 4002-211, [1930]; AM 4002-204, [1930]; plaster, 9.4 × Ø 12 cm; marble, stone (limestone), 15 × 15 × 15 cm; stone (limestone), 88 × 31 × 25.5 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, AM 4002-35

Profile of a Woman with a Chignon, Face Inclined, [before 1924]

Oil on canvas, 55 × 46 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, AM 4478 P

Woman with Comb (Profile of a Woman with a Chignon), ca. 1912

Gouache on paper, 49 × 36 cm

Private collection, Paris

In his preface to George Oprescu’s L’Art du paysan roumain (The Art of the Romanian Peasant), Henri Focillon refers to Romanian folk art as “a powerful base” charged with a “poetic virtue [that] belongs to those sacred regions where every man retains the memory of his own.”1 Leaving Oltenia for Paris in 1904, Brancusi held on to the memory of the ancestral woodworking tradition of his native region. This art is expressed in small spoons and cattails— which Brancusi collected—but also in traditional architecture as practiced by his great-grandfather, a carpenter who built the village church. In this quest for origins, the gate—the quintessential place of passage—is significant for an artist in exile like Brancusi, as migration involves crossing many thresholds. Creating gates was a challenge for some of the greatest sculptors of their time, from Lorenzo Ghiberti to Auguste Rodin. But while Rodin’s The Gates of Hell was a response to the Florentine sculptor’s Gates of Paradise, Brancusi was confronting an entirely different tradition, that of the peasant art of the Carpathians, the bearer of another form of modernity.

His oak Gate is dated between 1923 and 1936, a period of recognition for both Romanian folk art and the artist. The uprights came from the old Bench, photographed by Brancusi in a vertical position in preparation for his exhibition at the Brummer Gallery in New York in 1933.2 The transformation of the Bench into a doorjamb is typical of the sculptor’s repurposing and reversals, as reuse is also common in folk art. The creation of the Bench followed Brancusi’s trip to Romania with his friend Eileen Lane in 1922, during which they visited places linked to the sculptor’s youth (Hobiţa, Craiova, Bucharest).

Brancusi’s Gate is both robust and slender, an effect achieved by the succession of pyramids on its outer sides. The symmetrical uprights give the impression of interlocking in a perfect union of materials. This interlocking effect evokes that of The Kiss, but also the skillful assembly of traditional Romanian farmhouse gates. The latter are the very symbol of Romanian folk art, according to art historian Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș, founder in 1906 of the National Museum of Ethnography. He evokes their unchanging character for fifty centuries, the power of the work of the peasant carpenter and joiner, and the multiple symbols of the motifs that cover them (spirals, ropes, sun crosses, rosettes), some of which are linked to the rhythm of walking, singing, and dancing.3 One of these gates, dated 1884 from Gorj in Oltenia, is part of the French public collections thanks to a donation from the Romanian commission for the 1937 Paris Exposition Internationale. It was destined for the exhibition’s international pavilion, where Brancusi’s Little Bird was displayed. Made of carved oak of monumental

dimensions, the gate was in the form of an arch surmounted by a canopy. Its pillars were carved with geometric motifs, spirals, and sun crosses. In addition to its shared history with L’Oiselet, it also shares certain characteristics with the sculptor’s Gate, such as the structure, material, and geometric forms. But the motifs on the latter are not engraved or overlaid; they are simplified and transposed into volume in space. The research was also reflected in Brancusi’s drawings for his Gate of the Kiss project, part of the sculptural ensemble he inaugurated at Târgu Jiu in 1938. With this creation, Brancusi, a Romanian of international renown, signaled a return from modernity to the tradition that nurtured it. Folk art, which had been gradually disappearing at a time when it was attracting growing interest, thereby gained a new lease of life through the creations of artists like Brancusi, who drew inspiration from it.

M.-Ch. C.

1 George Opresco [Oprescu], L’Art du paysan roumain, preface by Henri Focillon, Bucharest: Académie roumaine, 1937, p. 9 [translated].

2 Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, PH 707 A.

3 See Paul Morand, “Bucarest, portrait de ville,” in Marianne (August 28, 1935), p. 10.

WAYNE MILLER

The sculptor Constantin Brancusi in his studio, Paris, 1946 Gelatin silver print, 35.5 × 27.9 cm Blank postcard from Brancusi’s collection showing a farm in Romania, date unknown Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris, Fonds Brancusi, BRAN 44 Farm entrance, ca. 1900–1946 Print on Baryta paper mounted on card, 22.5 × 29.5 cm (montage format) Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris, PP0083971

Photo: O.T.N.

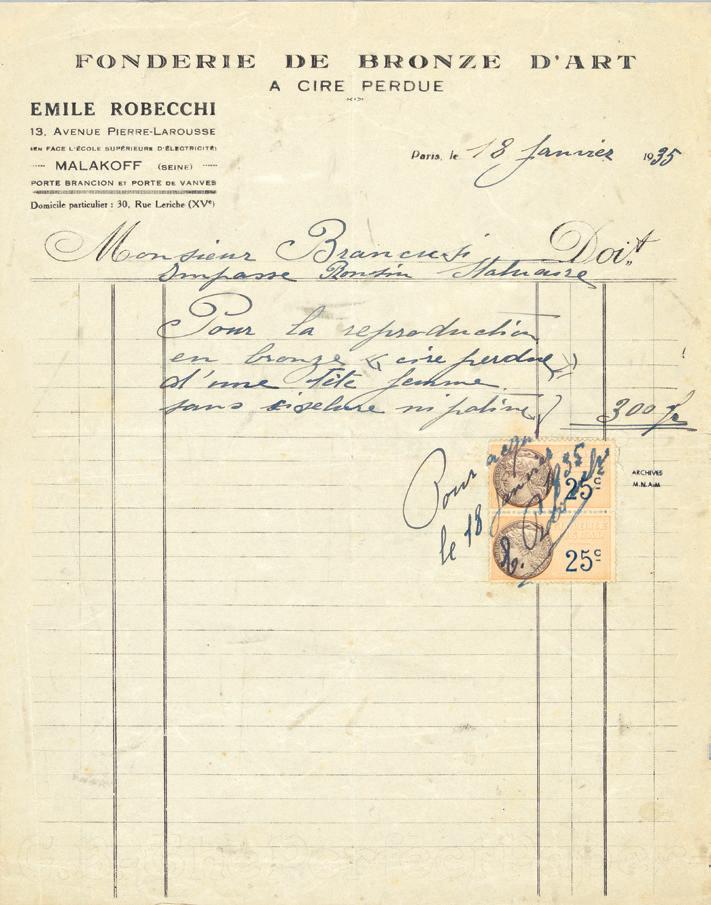

“High polish is a necessity which certain approximately absolute forms demand of some materials. It is not always appropriate; it is even very harmful for certain other forms.”1

Polishing is a stage in the practice of sculpture and concerns the finish of the surface. For Brancusi it was an integral part of the form, whatever the material used. In the Craiova Torso (1907), for example, he demonstrates an exceptional mastery in working marble, combining a polished face, leaving no trace of tool marks, with one left in its state of roughed-out stone. Working with wood, he was sensitive to different species and knew how to recognize those grains that lend themselves to polish, as in The Sorceress, carved in walnut (1916–24), Torso of a Young Man in maple (1917, Philadelphia Museum of Art), or Portrait of Nancy Cunard in cherrywood (1927, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City), which also use the found natural shape of the wood. Working with bronze, Brancusi gradually abandoned traditional methods of applying a final patina to the metal and started polishing the surface directly. In a letter to Alfred Stieglitz in 1914, he describes the exacting effort of this manual work, which results in unique bronzes that cannot be reproduced.2 Mlle Pogany I (1913) juxtaposes these two types of bronze finish to

great effect. Brancusi would eventually work only with uniformly polished surfaces. In the bronze and marble Birds in Space, polish works particularly well with the elongated shapes to convey the idea of ascension. By the early 1920s, Brancusi made use of mechanical tools to facilitate this task of polishing and obtained remarkable results, for instance in his bronze Leda (1926).

Very early in Brancusi’s career, critics like Roger Fry admired the exceptional finish of his work,3 and Roger Vitrac compared the sculptor to a “sorcerer” with “a disturbing grasp of materials.”4 But others were not so positive. Ezra Pound described the polished bronze surfaces visible in Brancusi’s superb photographs of works like Mlle Pogany II (1920, Museu de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro) as possessing “transient glory,” adding that “the dazzle of crystal” distracted from the contemplation of “form leading into the infinite.”5 In 1957 Alberto Giacometti derided these polished surfaces in his response to the question “What relationship exists between the art of sculpture and the beauty of a finished car?,” arguing that Brancusi’s abstract sculptures no longer belong to the world of Auguste Rodin or Chaldean sculpture but “to a world of their own, very close to the world of machines, the world of objects.”6 Giacometti could not have known that his words would perfectly describe the finish of the posthumous bronzes produced by Brancusi’s heirs, using similar tools but lacking the master’s touch and eye.7 A. P.

1

“Propos by Brancusi,” in Brancusi, exh. cat., Brummer Gallery, New York, 1926, n.p. [p. 5]. Translated from the French, “Réponses de Brancusi sur la taille directe, le poli et la simplicité dans l’art,” in This Quarter, no. 1 (Spring 1925), p. 235.

2

Constantin Brancusi, letter to Alfred Stieglitz, April 10, 1914, Alfred Stieglitz Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven.

3

Roger Fry, “Salon of the Allied Artists,” in The Nation (August 2, 1913), cited in Deborah Menaker Magid, “A Note on Brancusi and the London Salon,” in Art Journal, 35, no. 2 (Winter 1975–76), p. 105.

4

Roger Vitrac, “Constantin Brancusi,” in Cahiers d’art, 4, nos. 8–9 (1929), p. 384.

5

Ezra Pound, “Brancusi,” in The Little Review, 8 (Autumn 1921), p. 6.

6

Alberto Giacometti, “La Voiture démystifiée,” in Arts, no. 639 (October 9–15, 1957), p. 1, repr. in Alberto Giacometti, Écrits, Paris: Hermann, [1991] 2001, p. 78.

7

These works can be viewed on the website of the Kasmin Gallery, New York, whose catalogues attempt to legitimate the posthumous works by giving them a history that is not rightfully theirs. See Sharon Hecker and Peter Karol, eds., Posthumous Art, Law and the Art Market: The Afterlife of Art, New York: Routledge, 2022, pp. 47–57.

Invoice from art caster Émile Robecchi dated January 18, 1935

Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris, Fonds Brancusi, BRAN 39

Prometheus, 1911

Polished bronze, 13.3 × 17 × 13.4 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, AM 4002-22

In January 1916 Brancusi moved into a studio at 8 impasse Ronsin, behind the Necker Hospital in the fifteenth arrondissement. The 125-meter-long cul-de-sac was lined with small houses surrounded by patches of garden. It was also home to the luxurious Villa Steinheil—the scene of a double murder in 1908 that was never solved—a warehouse, a printing works consisting of a large building flanked by a chimney, and artists’ studios at numbers 6, 8, 11, and 12, mostly set back from the street out of sight.

Most of the artists present in 1916, such as painters Raphaël Collin, Gabriel Dussart, Stephen Seymour Thomas, and Pierre and Germaine Marcel-Béronneau, have been forgotten. Among the sculptors, Pierre-Luc and Germaine Feitu lived in a studio next to Brancusi’s, while Paul-Gabriel Capellaro, André de Manneville, Georges Armand Vérez, and Jeanne Lot-Eyquem were housed at number 11. During the First World War, the Appui aux artistes (Support for Artists) association opened a canteen reserved for them.

In 1922 an American reporter described the approach to Brancusi’s studio: “The path [. . .] leads through a graveled garden-court planted with shrubs and trees. After the clatter of the Paris streets, this sylvan approach prepares one for the spaciousness of his workshop. It almost seems to be without walls.”1 Here, Brancusi received artists, poets, and art lovers, some with ties to the Romanian community. He hosted meals in the studio in winter and in the garden in summer.

Daily life in the impasse Ronsin was also punctuated by the comings and goings of the three hundred employees of the Vaugirard printing works, which among other things printed the magazines Art et décoration and Fémina L’Intransigeant (June 2, 1908) described the noise of the machines as “A continuous rumbling, erratic banging, and

the whoosh of a jet of steam escaping at regular intervals.”2 In July 1927 Brancusi was made to leave his studio by the printing house, which owned several houses and plots in the street. He moved into number 11, comprising twenty-four workshops and a house nestled in the greenery. In 1931 twelve people lived in this artists’ residence, including five sculptors: Jeanne Eyquem, Maurice Rondest, Vérez, Laurent-Pierre Roustan, and a fellow Romanian, Constantin Fărâmă.

Recalling the solidarity of the impasse Ronsin, the painter Natalia Dumitresco said: “when someone wanted for something, [Brancusi] would try to see what they needed and help them.”3 As Michel Ragon pointed out, however, “it was impossible to enter Brancusi’s studio if you admitted to being a journalist, and an art critic all the more so.”4

In 1943 demolitions began in the street, as little by little the public hospitals service acquired the buildings to expand Necker Hospital. In 1954 number 11 had twelve permanent residents. Brancusi mainly spent time with his Romanian friends Alexandre Istrati and Dumitresco, but also with the young François-Xavier Lalanne. The following year, Eva Aeppli and Jean Tinguely moved into studios opposite Brancusi’s, where Daniel Spoerri and Yves Klein were regular guests. The demolition work intensified in 1956, leaving a vast wasteland in its wake. For the artists, the future of the site depended on Brancusi’s presence, as Tinguely explained in January 1957: “He’s the reason we’re still here. [. . .] As soon as he dies [. . .] they’ll get a bulldozer in there and be done with it.”5

Brancusi died on March 17, 1957, bequeathing his studio to the French state with the proviso that it be reconstructed. The last artists to leave the premises were the painter Gaston-Louis Roux in 1970 and sculptor André Almo Del Debbio in 1971. The workshops were demolished in the winter of 1972. The last vestige of impasse Ronsin as it was when Brancusi arrived, the brasserie at 150 rue de Vaugirard, survived until 2021.

E. N.-G. and C.-E. D. D.

1 Jeanne Robert Foster, “New Sculptures by Constantin Brancusi: A Note on the Man and the Formal Perfection of His Carvings,” Vanity Fair, 18 (May 1922), p. 68.

2 Pierre Larue, “Mme Steinheil parle: Les Détails du drame,” L’Intransigeant, 10184 (June 2, 1908), p. 1.

3 Rushes of an interview with Alexandre Istrati and Natalia Dumitresco by Jean-Marie Drot, for L’Art et les hommes: Inventaire Montparnasse, 1964, Archives INA Médiapro. 4 Michel Ragon, D’une berge à l’autre: Pour mémoire, 1943–1953, Paris: Albin Michel, 1997, p. 159.

5 Jean Tinguely quoted in “Impasse Ronsin,” Tribune de Lausanne, 13 (January 13, 1957), p. 5.

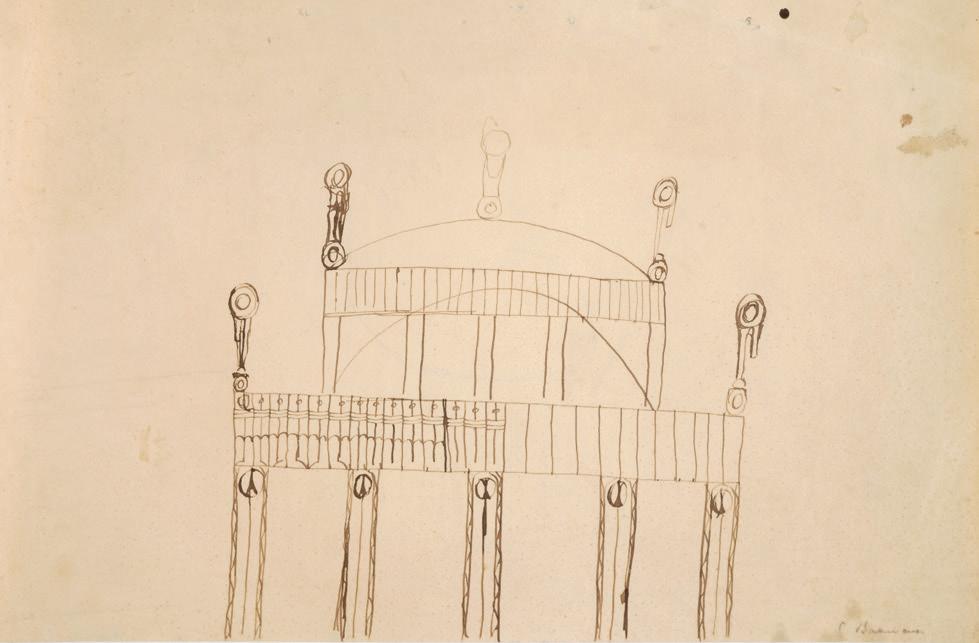

Project for the Temple of Deliverance at Indore, 1936

Graphite pencil on paper, 26 × 20 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Gift, 2001, AM 2001-189 (14)

Project for a Temple, ca. 1930–36

Brown ink on paper, 27.5 × 42 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Gift, 2001, AM 2001-153

Through Henri-Pierre Roché, Yeshwant Rao Holkar II, Maharaja of Indore, purchased a bronze Bird in Space in 1931 and two others in black and white marble, which were delivered in 1936. From that point, the plan for a temple to be built in Indore was born. Roché acted as an intermediary and passed on many instructions to Brancusi: a circular vault that would let the sun shine through and light up the Bird, an interior pool in which the sculptures would be reflected, an electrified space at night to illuminate them, and raised elements on the floor for sitting. This “Temple of Meditation” was to be a place of contemplation, showcasing the bronze Bird in Space. The project was commissioned on April 25, 1936. In late 1937 Brancusi sailed for India, where he stayed for the whole of January 1938, visiting several temples around Mumbai. But by the summer of 1938, the project had stalled; the maharaja and his relatives, who were unwell, finally abandoned it. V. L.

“I realized to what extent the reflection of the exterior shape of two beings is removed from the essential truth. How remote such sculptures are from the great events of their birth, their joys and tragedies, as well as the grandeur of life and death itself. [. . .] I wanted to embody not only that unique couple but all those pairs that lived and loved on this earth.”1

A cornerstone of Brancusi’s art, The Kiss was the first motif the sculptor focused on in the form of a series, one that was to last four decades.

The first version of the motif dates to 1907 (Muzeul de Artă, Craiova), three years after the artist’s arrival in Paris. Rejecting all forms of academicism, Brancusi embarked on his own path at the age of thirty-two: “[The Kiss] has been my road to Damascus,” he confided to his friend Henri-Pierre Roché.2 This new language was based on a novel process: abandoning modeling in favor of direct carving, which demanded a respect for the block of stone and involved frontality and a simplification of forms. The two bust figures, their faces touching, have barely sketched features and neither nose nor ears. The woman is distinguished from the man by the slight protrusion of her chest and her long hair. Prior to 1907, Brancusi’s art was mainly devoted to portraiture. Here, on the contrary, he refuses all personalization. Faces are reduced to Cubist-style signs: an almond for the eye, a line for the mouth. Although no study preceded The Kiss, it has rightly been compared to Wisdom of the Earth (1907–8),

of which it seems to be a duplicated, reversed version. This play of mirroring immediately located Brancusi’s work in an engagement with sameness and difference, repetition, and reflection.

The invention of this new sculptural language followed Brancusi’s brief time at Rodin’s studio in early 1907. For Sidney Geist, author of an in-depth study of the series, “The Kiss has all the appearance of a declaration of independence, designed to oppose Rodin’s at every point. The two works, in any case, constitute a paradigm of artistic polarity.”3 A famous allegory of Love originally conceived for The Gates of Hell, Rodin’s Kiss was exhibited as an autonomous group as early as 1887, inspiring a generation of emulators. In 1907 Brancusi took the opposite approach. While the master of Meudon’s streamlined marble shows two lovers sitting on a rock in perfect balance between fullness and emptiness, in Brancusi’s version the lovers themselves form the rock, the block’s rediscovered unity having no spatial existence other than their embracing bodies. Neither figure dominates the other: man and woman are equal in the impulse of love.

The Kiss is also revolutionary for its technique, direct carving, of which it is one of the earliest examples by Brancusi. The break is both stylistic and conceptual. The elemental stylization of the limestone contrasts with the elegance of Symbolist sculptures. Brancusi rejected the tradition of modeling, which involved transposition into marble by skilled assistants. The statue-cube draws instead from the most archaic sources of sculpture. It reflects the avant-garde’s fascination with the “primitive,” embodied by the art of Paul Gauguin, which had been celebrated at the Salon d’Automne

1 Sanda Miller, Constantin Brancusi: A Survey of His Work, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995, p. 79.

2 Henri-Pierre Roché, “L’Enterrement de Brancusi,” in Hommage de la sculpture à Brancusi, ed. Suzanne de Connick, Paris: Éditions de Beaune, 1957, p. 29.

3 Sidney Geist, Brancusi/ The Kiss, New York: Harper & Row, 1978, p. 22.

ANDRÉ DERAIN

Crouching Figure, 1907 Sandstone, 33 × 28 × 26 cm Mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna, Acquired in 1964, P 45/0

The Kiss, 1923–25 Stone, 36.5 × 24.5 × 23 cm Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Constantin Brancusi Bequest, 1957, AM 4002-3

The Kiss, 1916 Limestone, 58.4 × 33.7 × 25.4 cm Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950, 1950-134-4

References to Brancusi’s Aphorisms, p. 23

1. Handwritten note at the bottom of the collective resolution written in defense of Tristan Tzara after the Congrès de Paris in defense of the Spirit of Modernity, 1922.

2. Quoted in Pontus Hultén, Natalia Dumitresco, and Alexandre Istrati, Brancusi, ed. Patricia Egan, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987, p. 182.

3. Quoted in Carola Giedion-Welcker, Constantin Brancusi, trans. Maria Jolas and Anne Leroy, New York: George Braziller Inc., 1959, p. 220.

4. Quoted ibid., p. 220.

5. Quoted in Ionel Jianou, Brancusi, New York: Tudor Publishing, 1963, p. 67.

6. Quoted in Vintila Russu-Sirianu, Vinurile lor: Ore petrecute cu George Enescu, Constantin Brancusi, etc. Bucharest: Editura pentru Literatura, 1969, p. 60. Translated into English in Sorana Georgescu-Gorjan, Aşa grăit-a Brâncuşi / Ainsi parlait Brancusi / Thus Spoke Brancusi, Bucharest: Criterion, 2010, p. 124.

7. Quoted in Hultén, Dumitresco, and Istrati, Brancusi, p. 264.

8. Quoted ibid., p. 269.

Artwork Credits

All works by Constantin Brancusi: © Succession Brancusi – All rights reserved. ADAGP, Paris, 2024

© ADAGP, Paris, 2024: Carl Andre, Max Bill, André Derain, Bertrand Lavier, Fernand Léger, Lucia Moholy, Isamu Noguchi, Jean Prouvé, Simon Starling, Didier Vermeiren

© 2024 Calder Foundation, New York/ ADAGP, Paris

© ADAGP / Comité Cocteau, Paris, 2024

© Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris 2024

© Judd Foundation / ADAGP, Paris, 2024

© Fondation Oskar Kokoschka / ADAGP, Paris, 2024

© Man Ray 2015 Trust/Adagp, Paris 2024

© Successió Miró/ADAGP, Paris, 2024

© 2024 The Estate of Robert Morris/ ADAGP

© The Estate of Edward Steichen / ADAGP, Paris, 2024

© The Estate of Hollis Frampton

André Kertész © RMN-Grand Palais— copyright management

© Jeff Koons

© Estate Germaine Krull, Museum Folkwang, Essen

© Succession H. Matisse

© Wayne Miller | Magnum Photos

© Succession Picasso 2024

© Charles Ray, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

© Evariste Richer

Hans “John” D. Schiff © The Leo Baeck Institute

© Paul Sharits

François Vizzavona © RMN-Grand Palais—copyright management

© Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts/ Happy Valley Foundation

Publication Credits

André Breton, “Genèse et perspective artistiques du surréalisme” (1941), in Le Surréalisme et la peinture, Paris: Gallimard, 1965, p. 72: © Éditions Gallimard

Clement Greenberg, “The New Sculpture,” in Art and Culture: Critical Essays, Boston: Beacon Press, 1961, p. 141. Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Sculpture: Its Pictorial Past,” in Art and Culture: Critical Essays Boston: Beacon Press, 1961, p. 162. Eugène Ionesco, Notes and Counter Notes: Writings on the Theatre, trans. Donald Watson, New York: Grove Press, 1964, pp. 262–263.

Ezra Pound, letter to Brancusi dated December 30, 1927. By Ezra Pound, from New Directions Pub. acting as agent, copyright © 2023 by Mary de

Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

André Salmon, Souvenirs sans fin 1903–1940, Paris: Gallimard, 2004, pp. 1011–1017: © Éditions Gallimard

William Carlos Williams, “Brancusi,” in The Arts, 30 (November 1955), pp. 21–25: By William Carlos Williams, from A RECOGNIZABLE IMAGE, copyright © 1939 by William Carlos Williams. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Photo Credits © Agence photographique du musée Rodin – Pauline Hisbacq: p. 21 bottom left

Photograph by Ronald Amstutz

© Jeff Koons: p. 176 bottom

Photo © Art Institute of Chicago, Dist. RMN-GP/image The Art Institute of Chicago: pp. 47 bottom right, 159 top Reproduction © Bibliothèque Kandinsky, MNAM-CCI, Centre Pompidou: pp. 22, 24, 39, 40, 41, 46 top right and bottom, 64, 66, 67 bottom left and bottom right, 72 bottom, 75 bottom, 76 bottom, 83, 88, 119, 120, 129 bottom left, 134, 138, 144, 162 centre right, 172 left, 180, 183, 185, 186, 188, 189, 194, 195, 200, 221, 222–223, 224, 226, 234, 238, 239, 249 top left and bottom, 262, 267, 285 top, 289, 290, 291, 292, 299 top right, 302; [Photo Jacques Faujour]: pp. 101, 102, 103

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris: p. 61 top left

Photo Constantin Brancusi © Succession Brancusi—All rights reserved (ADAGP) 2024. Reproduction © Akama/ Fontenoy : pp. 71, 257 right

Photo Constantin Brancusi © Succession Brancusi—All rights reserved (ADAGP) 2024. Reproduction © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Dist.

RMN-GP: back cover, pp. 47 bottom left, 62, 97, 161, 165, 170, 171 left, 178, 204, 216 top, 251 left, 268, 287; [Audrey Laurans]: pp. 77, 155 bottom, 235; [Georges Meguerditchian]: pp. 21 bottom right, 31, 32 bottom, 42, 47 top, 50, 115, 117, 123 top, 159 bottom, 162 top left, 166, 172 right, 215, 220, 233, 260 left, 300 bottom right, 301; [Philippe Migeat]: pp. 61 top right, 67 top, 72 top, 75 top left, 93 top right and bottom right, 118 bottom right, 121 top left and top right, 133, 152 top left, 167, 213, 216 bottom left and bottom right, 217, 261, 300 top; [Jean-Claude Planchet]: p. 303; [Bertrand Prévost]: pp. 214, 225 right; [Adam Rzepka]: p. 277 top left

Photo © Centre Pompidou: p. 171 right; [Janeth Rodriguez-Garcia]: p. 19 centre right; [IMA Solutions]: p. 269 bottom

Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/ Dist. RMN-GP: pp. 35, 253; [Jacques Faujour]: pp. 152 bottom left, 279; [Georges Meguerditchian]: pp. 16, 19 bottom right, 29, 36 top right, 49 top left, 79 bottom left, 80 bottom right and bottom left, 81 bottom, 93 top left, 95, 106, 108 bottom, 121 bottom left, 123 bottom, 124, 125 centre left, centre right, bottom left and bottom right, 143, 147 top left and bottom left, 152 centre left, 155 top, 158, 208, 256, 258, 269 top, 273 left; [Philippe Migeat]: pp. 27, 79 top, 80 top and bottom right, 176 top, 250 top, 259 bottom; [Jean-Claude Planchet]: pp. 147 top right, 154 top, 245, 251 bottom right; [Bertrand Prévost]: pp. 51, 87, 107 top, 187, 198 top, 250 bottom, 288; [Janeth Rodriguez-Garcia]: pp. 181 bottom, 251 top, 298; [Adam Rzepka]: cover, pp. 15 bottom left, 21 top right, 33 top, 36 bottom, 45, 48 bottom, 49 bottom, 52 left, 68, 69 left, 73 bottom, 81 top left and top right, 97, 108 top, 114, 121 bottom right, 125 top right and top left, 127, 139, 147 bottom right, 151 top, 152 right, 157, 169 bottom, 173, 197, 209, 219, 227, 255, 272; [Hervé Véronèse]:

pp. 74, 76 top, 105, 110, 112, 113, 225 left; [Peter Willy]: p. 53

Photo Lizica Codreano © Alkama/ Fontenoy: p. 274

Collection Friedrich Teja Bach, Munich: p. 277 top right

Collection David Grob, United Kingdom: p. 275

Collège de France. Archives. Fonds Marey: p. 32 top

© Image: Joaquín Cortés: pp. 75 top right, 181 top

Photo Ariane Coulondre: p. 283

Image courtesy Dallas Museum of Art: p. 206

Photo rights reserved: pp. 107 bottom, 297 right

Photo rights reserved. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Item ID: 9518: p. 25

Photo rights reserved. Reproduction © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP [Guy Carrard]: pp. 281, 299 bottom; [Georges Meguerditchian]: pp. 46 top left, 260 right, 295, 299 centre left; [Philippe Migeat]: pp. 56, 61 bottom, 92, 162 top right, 229, 299 top left, 300 bottom left

Photo rights reserved. Gorjan Archives: p. 282 bottom

Photo © François Fernandez: p. 116

Photo by Hollis Frampton © The Estate of Hollis Frampton. Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York: p. 177

Photo Ștefan Georgescu-Gorjan, Gorjan Archives: p. 282 top

© Jean-Pol Grandmont: p. 202 right

Photograph by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York: pp. 33 bottom, 57, 109, 179, 257 left

Photo Florence Homolka. Reproduction © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Guy Carrard/Dist. RMN-GP: pp. 141, 169 top

Photo Nathan Keay, Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago: p. 37

Photo Germaine Krull © Estate Germaine Krull, Museum Folkwang, Essen. Digital image: The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence: p. 277 bottom right

Photo Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Reproduction © Bibliothèque Kandinsky, MNAM-CCI, Centre Pompidou/Dist. RMN-GP: p. 43

Photographic data in the public domain—Kunstmuseum Basel: p. 160 Kunst Museum Winterthur, purchase, 1951 © SIK-ISEA, Zurich (Jean-Pierre Kuhn): p. 73 top

Bernard Lagacé and Lysandre Le Cleac’h: p. 284 top; [after a diagram by Doïna Lemny]: p. 284 bottom

Photographer: Paul Laib, courtesy the De Laszlo collection of Paul Laib negatives. Courtauld Institute of Art, London/Bowness: p. 137

Library of Congress, Washington, DC: p. 174

Photo Man Ray © Man Ray 2015 Trust/ ADAGP, Paris 2024. Reproduction © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/ Dist. RMN-GP: p. 69 right

© Wayne Miller | Magnum Photos: pp. 13, 129 top

Photo © Ministère de la Culture –Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie, Dist. RMN-GP/André Kertész: p. 285 bottom

Photo Moderna Museet Stockholm: p. 259 top

Photo Lucia Moholy © ADAGP, Paris, 2024. Reproduction © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist. RMN-GP/image of the MMA: p. 277 bottom left

© Monde et Caméra/Coll. Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace – Le Bourget/MC 7893: p. 162 bottom

Photo © mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien: p. 150

Photo © Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-GP/image Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac: p. 15 top

© Musée Rodin [photo Angèle Dequier]: p. 21 top left; [photo Christian Baraja]: p. 240

Photo O.T.N. Reproduction © Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-GP/image Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac: p. 129 bottom right

Photo Mircea Popa, 29.06.2023: p. 48 top left

Photo Evariste Richer: p. 198 bottom

Photo © RMN-GP [(Musée d’Orsay)/ Hervé Lewandowski]: p. 297 left; [(Musée du Louvre)/Franck Raux]: p. 20 right; [(Musée du Louvre)/ Hervé Lewandowski]: p. 19 centre left

Photo V. Sakayan, rights reserved. Reproduction © Bibliothèque Kandinsky, MNAM-CCI, Centre Pompidou: p. 231 bottom

Photo Hans “John” D. Schiff © The Leo Baeck Institute. Reproduction Charles Duprat: p. 84

Photo Edward Steichen © The Estate of Edward Steichen/ADAGP, Paris, 2024. Reproduction © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP [Guy Carrard]: p. 91; [Georges Meguerditchian]: p. 94, 193, 263, 264

Photo Alfred Stieglitz. Reproduction The Modernist Journals Project (searchable database). Brown and Tulsa Universities, ongoing. www.modjourn. org: p. 265

Photo Studio Hamelle. Reproduction © Bibliothèque Kandinsky, MNAM-CCI, Centre Pompidou: p. 249 top right

Photo © Soichi Sunami. Reproduction © Bibliothèque Kandinsky, MNAM-CCI, Centre Pompidou: pp. 34 left, 96, 154 bottom

Photo © Tate: p. 36 top left

The Art Museum of Craiova, Romania: p. 149

Courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art: p. 203

Photo © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist. RMN-GP/image of the MMA: pp. 14, 90

Digital Image © 2024, The Museum of Modern Art/Scala, Florence: pp. 15 bottom right, 52 right, 118 top right, 218 left, 231 top, 270, 273 right

The National Museum of Art of Romania: pp. 20 left, 241, 242

Photo © The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Dist. RMN-GP/image Philadelphia Museum of Art: pp. 49 top right, 118 left, 151 bottom, 191, 218 top and bottom right

Photo © Didier Vermeiren/ADAGP, Paris, 2024: p. 207

Photo © Ville de Marseille, Dist. RMN-GP/Virginie Louis: p. 34 right

Photo François Vizzavona © RMN-Grand Palais—copyright management. Reproduction © Musée Rodin: p. 19 top

Photograph by Midge Wattles © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York: p. 48 top right

Photograph by Josh White: p. 202 left

We are committed to respecting the intellectual property rights of others. All reasonable efforts have been made to locate copyright holders. Any oversights will be rectified in future reprintings. Individuals or companies who hold the reproduction rights for their works are asked to contact the publisher.