Vorwort / Foreword

Johan Holten

Abstrakte Linien im Dazwischen des Dialogs / Abstract Lines in the In-Between of Dialogue

Susanna Baumgartner

Zeichnung: Raum, Zeit und Bewegung / Drawing: Space, Time and Motion

Thomas Köllhofer

Linie, Papier, Raum … Zwei Zeichnerinnen treffen sich / Line, Paper, Space … Two Draughtswomen Come Together

Petra Oelschlägel

Korrespondenz / Correspondence Monika Grzymala und / and Katharina Hinsberg

Interview Petra Oelschlägel mit / with Monika Grzymala und / and Katharina Hinsberg

Biografie, Bibliografie / Biography, Bibliography Monika Grzymala

Biografie, Bibliografie / Biography, Bibliography Katharina Hinsberg

Impressum / Colophon

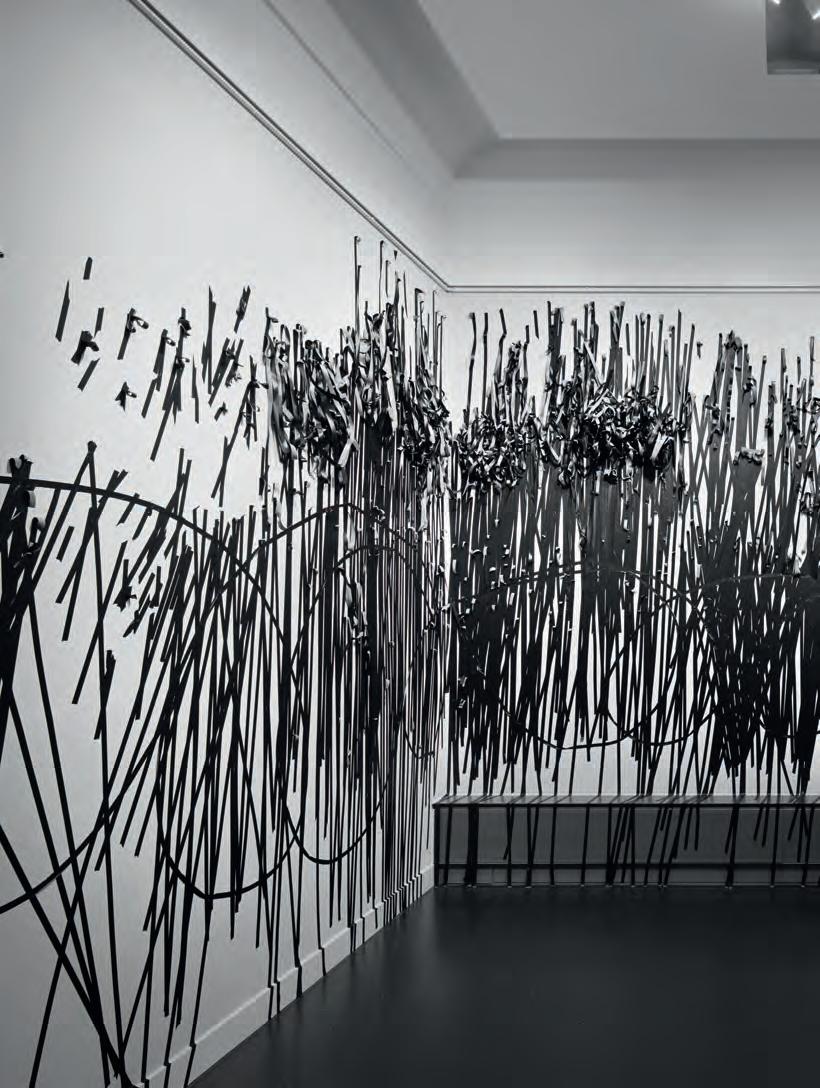

Monika Grzymala, Raumzeichnung Zwischen einer Linie (Detail), 2024

Es ist eine besondere Ausstellung, die den Anlass für diese Publikation gibt. Darin treffen zwei bedeutende Künstlerinnen aufeinander, die sich, ganz unabhängig voneinander, der sehr speziellen Technik einer Raumzeichnung gewidmet haben. Trotz ihrer Unterschiede arbeiten beide fast ausschließlich als Zeichnerinnen, aber sie tun es nicht nur in den traditionellen Medien der Zeichnung, sondern besetzen damit ganze Wände und Räume, wodurch ihre Werke eine geradezu bildhauerische Qualität erreichen.

Ihre Arbeiten hinterfragen und erweitern somit die traditionelle Vorstellung von Zeichnung, die üblicherweise als Lineament oder Schraffur einen Bildraum auf dem zweidimensionalen Papier oder einem anderen Zeichengrund entstehen lassen. Die Zeichnung ist die direkteste künstlerische Technik, die innere Vorstellungen der Künstler*innen spontan und ungefiltert aufs Papier bringen kann. Diese Spontanität bleibt erhalten in den Raumzeichnungen von Monika Grzymala und Katharina Hinsberg, ihrer Größe und physischen Komplexität zum Trotz.

Ihre in den Ausstellungsräumen dreidimensional sich entfaltenden Werke entstehen aus gänzlich gegensätzlichen Dynamiken, aus unterschiedlichen Bewegungsabläufen, die auch den verschiedenen Persönlichkeiten der beiden Künstlerinnen ein Stück weit entsprechen. Während Katharina Hinsberg mit einer frei schwebend durch den Raum gezogenen Linie aus Knetkugeln eine geradezu tänzerische Leichtigkeit erreicht, mit der sie die räumliche Ausdehnung auslotet, besetzt Monika Grzymala Raumbereiche mit einer spontan energetischen, geradezu eruptiven Raumzeichnung aus Linienbündeln, die sie mit Klebebändern entstehen lässt.

Die Kunsthalle Mannheim ist mit seinen großen skulpturalen und plastischen Sammlungen vom ausgehenden 19. bis ins 21. Jahrhundert eines der bedeutendsten Bildhauermuseen der Republik. So ist es auch folgerichtig, dass sich Thomas Köllhofer nach Ausstellungen zur Plastischen Graphik und zur Bildhauerzeichnung nun auch dem Thema der Raumzeichnung widmet, einem Thema, das die Zeichnung anders definiert und Gattungsgrenzen erweitert.

Die Ausstellung entstand in intensiver Zusammenarbeit zwischen den beiden Künstlerinnen und dem Kuratorenteam mit Thomas Köllhofer und Susanna Baumgartner. Nicht zuletzt konnte die Ausstellung auch dank der großzügigen Unterstützung durch die Kunststiftung der LBBW sowie durch die VR-Bank zustande kommen. Beiden Sponsoren sei an dieser Stelle ausdrücklich gedankt. Mein besonderer Dank gilt den beiden Künstlerinnen, die intensive Auseinandersetzungen und den fortwährenden Dialog nicht gescheut haben, um diese installative Ausstellung einzurichten. Ebenso danke ich Petra Oelschlägel, die einen ausgesprochen erhellenden Textbeitrag für diesen Katalog verfasst hat, Jennifer Eckert für die überaus gelungene Gestaltung und dem Kerber Verlag für die hervorragende Zusammenarbeit.

Susanna Baumgartner und Thomas Köllhofer wie dem gesamten Team der Kunsthalle gilt mein Dank für das große Engagement für die Ausstellung und die begleitende Publikation.

Johan Holten

Direktor der Kunsthalle Mannheim

turn, the mesh of lines becomes concentrated to form a sort of physiogram of the artist’s space-related sequences of movement. Accordingly, for her drawings in space made with adhesive tape, she also fundamentally calculates the corresponding number of kilometres of tape used, so as to convey at least an approximately comprehensible measure of time.

In a Spatial Drawing, in contrast to a drawing on paper, walls, or objects, no other reality is suggested or expansion of the present imagined. Instead, lines lead through the third dimension, cover long distances, or encircle interior spaces. Here as well, the line as such is not a space-containing element: it changes and expands in its relationship to what it surrounds and as a result of the space of three-dimensional experience that it ‘sketches and indicates’.

Katharina Hinsberg has created a line marked by spheres that meanders, rising and falling, through all the rooms of the exhibition. Although clearly one single line, this line in space arises, so to say, from a synthesis of two sequences of movement, since the artist first drew a curved line on the floor with chalk and another one in pencil over the walls. Based on points marked on both lines at intervals of 10 centimetres, it was then possible to fix successive intersections of the two lines in the space and for a sphere to be hung at each of these intersections.

An essential characteristic of the line in space produced in this way is that it seeks its own path, despite all the precision in the preparations, to which it owes its formal appearance. Even though the line on the wall and on the floor results from an explorative sequence of movement that is as intentional as it is intuitive, the combining of the two gave rise to a spatial drawing whose course was visualized accordingly by the artist, but could not be conceived in detail in advance. It is, however, based on its contingent freedom that the curiously oblivious line in space, rolling by in waves, generates its dancelike-seeming poetry.

While it is not possible to overlook Katharina Hinsberg’s line in space in its entirety, even in one and the same room, the corresponding partial piece can only be experienced successively. The idiosyncratic dynamic of this oscillating line also contributes to this, since our gaze follows a straight line more easily, is able to grasp it more quickly than irregular curves moving back and forth or up and down. The eyes of viewers nonetheless rapidly adapt themselves to the movement of the line with its swift drifting-away, winding deceleration, and loss of momentum when moving upwards, to then pause floating weightlessly for a moment at its apex before continuing once again, accelerating while gliding downwards.

Hinsberg’s spatial drawing can only be comprehended in its conceptual entirety when one truly walks along it while looking—when not only the eyes but also the feet are in motion. Correspondingly, just as the line on the floor and wall on the one hand and the

spatial drawing on the other temporalize different sequences of movement, the movement of viewers is itself individual with respect to its time scale.

Unlike Katharina Hinsberg, whose linear work meanders through the rooms like the notes of a melody, with her drawings in space made with black, white, and/or reflective adhesive tape, Monika Grzymala practically occupies the rooms of the exhibition. Her language of the line calls to mind dynamic symbols of movement in comics, or trick motifs from film such as the threads that Spiderman slings constantly and every which way as adhesive climbing holds and lifelines, but it also makes one think of the bundles of rays in Roy Lichtenstein’s brightly coloured paintings, whose explosive power is intensified further by an onomatopoeic WHAAMM!, BRATATATA, or BLAM! Paradoxically, with her colourless structures of lines tautly spanned between floor, wall, and corner, Monika Grzymala succeeds in generating a comparably crackling-explosive atmosphere. Grzymala works with lines that she seems to sling through the air, twists in a rope-like manner, balls together and bundles as layers—in part whirling, in part intersecting, in part fluttering like flames between vehemence and frozen movement, and again and again petering out in arcs like an exhaling, inwardly concentrated coming-to-rest.

Since Grzymala always executes these drawings in space herself, they are visibly shaped by the artist’s speed and motor skills and become a drawing in space whose intriguing forces call the static equilibrium of the walls into question in a seemingly playful manner. Under Grzymala’s approach, the space—and in particular its interior space—is transformed into a sort of sculptural graphic work. In it, Grzymala also begins at times with a two-dimensional application of tape to wall and floor, and then develops line structures from a swirling concentration.

Fundamentally, Grzymala does not correct a line once it has been drawn. The linear movement as a whole remains an authentic expression of a one-off process of creation in the moment. This means that the artist has to have an approximate notion of the outcome of

her drawing in space and to work with great concentration, while also surrendering to the flow of the work and being open to relinquishing control over what occurs. Not least owing to the ‘sticky’ material, she has to reckon with the unanticipated and react spontaneously to the unforeseen. Thus Grzymala, very much like Hinsberg, produces her drawings in space based on conceptual coordinates and determines them to only a limited extent with respect to their actual progression.

Grzymala’s combative appropriation and interrogation of spatial situations is communicated directly to viewers of her works. At the same time, their dynamics, which seem to take possession of everything and everyone, necessitate an ‘optical stability’, specifically also where reflective adhesive tape begins to dissolve spatial boundaries and itself stands opposite viewers shimmeringly and iridescent. While Grzymala

sounds out the boundaries of a space ‘combatively’, Hinsberg allows her line to draw through a sequence of spaces with a light, free movement. Nonetheless, whether lyrically restrained or powerfully gripping, the two artists’ drawings in space literally tackle their viewers and confront them with a physical experience that thwarts purely superficial perception in passing.

Monika Grzymala’s bundles of lines and Katharina Hinsberg’s filigree ‘line in space’ are both drawing and sculpture. What at first seems contradictory can be rendered more intelligible with a brief look back.

In the post-war Federal Republic of Germany, the sculptor and draughtsman Norbert Kricke (1922–1984) occupied himself in particular with questions of space, movement, and time: ‘I don’t want real space or real movement (mobiles), I want to represent movement. I try to endow the unity of space and time with form.’1

Kricke produced dynamic layers full of tension, bundles, and structures of lines with great expansive, radiant power; he frequently executed the works in stainless steel so as to concentrate the mass and material of the linear sculptural form optically by means of the shiny surface (see fig. 2).

Space, time, and movement, about which Kricke was unable to think independently of one another, are also perceived by Hinsberg and Grzymala as an indissoluble whole. In contrast to Kricke’s structures of lines, which point far beyond themselves and into the boundless vastness of space, it nonetheless becomes particularly clear that the target-oriented energy of Grzymala’s drawings in space always remains site- and work-immanent and is formally fed back into them: instead of a breaking-out into open space, thus a testing-out and trial-of-strength— a densification, tension, and concentration of energy. What connects Hinsberg to Kricke on the other hand is essentially also the intensive interrogation of the beauty of slowly curving lines. That is why even Kricke’s late work Große Raumplastik (Large Spatial Sculpture) on the sculpture plaza of the Kunsthalle Mannheim (see fig. 3) , which unfolds in a seemingly right-angled manner, is also related to Katharina Hinsberg’s ‘line in space’. What characterizes Hinsberg, however, despite the extreme formal reduction, is a path of movement that is considerably more multifaceted, playful, and incalculable than Kricke’s austere line management. And Hinsberg succeeds in particular in communicating in the linear what Kricke also strove for, but managed to do fully and entirely in drawing: the line floating freely in space.

Besides the work of Norbert Kricke, the American ‘action painting’ of, for instance, Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) also turns out to be a formative context for the artists Hinsberg and Grzymala. Just as Pollock slung paint at large-format canvases and thus regarded his works produced using the entire body as a direct expression of physical as well as mental movement, Hinsberg and Grzymala’s drawings, too, are an expression of the movements of their bodies in space and the result of a management of the line profoundly influenced by personal life and experience.

A comparative look at Norbert Kricke’s linear space sculptures or Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings was taken up by the art of Informel with its focus on process-oriented modes of creation, gestural notations of movement, and formally open structures as

Monika Grzymala, Kinesphere, 2020–2024

27.2.2024

Why this red? I’ve often asked myself that question. And, naturally, this red is always a somewhat different red, depending on which pen, which paint, or which paper I use. There are various answers: the one is that red holds less meaning for me than, for instance, green or blue, which are associated with plants, water, or the sky. Or perhaps, if nonetheless significant, I find the connection to blood and arteries stronger? Red is a signal colour, and best represents colour itself. And I think that red is close to me as well because red is the colour that we also see when our eyes are closed.

Warum dieses Rot? Das frage ich mich auch oft. Und natürlich ist dieses Rot immer ein etwas anderes Rot, je nachdem, welchen Stift, welchen Lack oder welches Papier ich nehme. Es gibt verschiedene Antworten: die eine ist, dass Rot für mich weniger Bedeutungsträger ist als etwa Grün oder Blau, die mit Pflanzen, Wasser oder Himmel assoziiert werden. Oder vielleicht finde ich, wenn doch Bedeutung, die Verbindung zu Blut und Adern stärker? Rot ist eine Signalfarbe, sie steht am ehesten für Farbe selbst. Und ich denke, Rot ist mir auch deshalb nah, weil Rot die Farbe ist, die wir auch mit geschlossenen Augen sehen.

27.02.2024

How aptly and plausibly described and responded to, how simply and poetically explained.

I posed the question because I generally forgo colour in my work in order to give the form more space. Colour overtaxes me, since I don’t know how to deal with colour. As a sculptor who draws, I prefer to leave the play with colour to other people. Colour occurs in the eyes and in the mind. Form arises from the body and is perceived with the body.

So treffend und plausibel beschrieben und beantwortet, so einfach und poetisch zugleich erklärt.

Die Frage stellte ich, weil ich in meiner Arbeit meistens auf Farbe verzichte, um der Form mehr Raum zu geben. Farbe überfordert mich, ich weiß nicht, wie mit Farbe umzugehen ist. Als Bildhauerin, die zeichnet, überlasse ich das Farbenspiel lieber den anderen. Farbe findet in den Augen und im Gehirn statt. Form entsteht aus dem Körper heraus und wird damit wahrgenommen.

27.12.2023

And then, dear Katharina, I also constructed a staircase for your cuts in the other sketchbook.

When leafing through the pages, a space is now generated.

Und dann noch habe ich im anderen Heft eine Treppe gebaut für Deine Schnitte, liebe Katharina.

Beim Durchblättern der Seiten entsteht nun ein Raum.