above Numerous ambitious Renaissance palazzos and churches offer seating to the public as part of the fabric of their structure, commonly in the form of a continuous stone ledge as the demarcation between a base molding or water-table and the wall. This example, with neighbors relaxing and chatting at the end of the day, is at the chapel of Santa Maria della Consolazione outside Todi in Umbria. sb 30, pen and ink, 1973

opposite While puzzling over these two examples of 17th-century furniture at the Villa Borghese—an elegant late rococo chair and bench—I suddenly realized the reason for the absence of a backrest. How was a person to sit in a chair or on a sofa if one was wearing a swallowtail coat or a voluminous dress or skirt with its structure of hoops, bustle, and train? Such parts of one’s costume needed to be allowed to extend and fall behind what really amounted to a bench or stool. sb 123, graphite pencil, 1999

top Furniture in the Villino at the American Academy in Rome: the first two items are small bedroom chairs, one peculiarly low to the floor, albeit extremely comfortable in a slouchy sort of way and probably intended for a child or a diminutive elderly person (a nonna or nonno); the larger armchair and sofa were covered in white linen canvas and equally comfortable. The fountain is in the Piazza of Santa Maria in Trastevere, which sits on a wedding cake of steps frequently seating many people. sb 147, Pen and ink, 2008

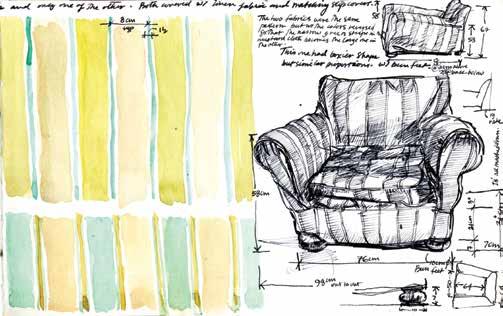

bottom These drawings are of two of the most comfortable armchairs ever. They are English country house pieces from the turn of the 19th/20th century, but were encountered in an old mill that had been converted for summer guests at Ribas in Provence. Their soft slouchy shape, cool linen fabric, and long arms and seats were delightful in the stone building and heat of summer. sb 83, pen and ink, watercolor, 1991

Calvert Vaux, Jacob Wrey Mould, and Frederick Clarke Withers were principal designers during this period in the Olmsted office; all English architects, they had been heavily influenced by Owen Jones, whose publication Grammar of Ornament had a marked impact on late-Victorian architecture. Oriental, Romanesque, medieval, Gothic, and neoclassical motifs were combined with the employment of mechanized processes to manufacture a diversity of site features and furniture in combinations of wood, metal, and stone. They also shared a predilection for floral motifs associated with transcendental and romantic attitudes. Like William Morris and others in England, these men wanted to create an environment of quality and amenity while using machine-tool processes to introduce art and educated taste to the public and working people.17

In the latter part of the 19th century, both Europe and America were industrializing at a rapid rate. As railroad engines rolled off production lines in Philadelphia, Birmingham, and Manchester, and steel rails were being laid across continents, as steel frame buildings with passenger elevators were being erected, along with elaborate metal-and-glass shopping arcades from Cleveland and Chicago to Paris and London, urban sophisticates developed a nostalgia for Europe’s agrarian past and America’s rapidly vanishing wilderness.

As a result, an alternative convention to this pervasive machinetool aesthetic began emerging in parks and gardens on both sides of the Atlantic—often within the same offices that were producing the industrialized furnishings. This outburst of design and construction encompassed a mélange of rustic pavilions, railings, benches, chairs, and footbridges that offered (manufactured, really) an image of rural simplicity and life in the wilderness and on the frontier. What might be described as something of a Daniel Boone–baroque or Paul Bunyan–rococo style of bark, thatch, and twisting branches appeared in parks in Paris, Philadelphia, and New York, as well as on the grounds of châteaux and villas throughout Europe.

In sharp contrast to the pared down, almost nautical classicism of replicable cast-iron features, this faux-rustic furnishing trend went so far as to employ reinforced ferro-cement techniques that had only recently been developed in architecture and engineering to construct fake log bridges and

that subsequently carried out social use studies of Bryant Park on a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation and produced guidelines for its renovation.

Whyte recommended opening it up to the street while adding various amenities and uses such as food and beverage vending, ideas that were subsequently implemented experimentally by the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation. When these strategies yielded promising results, we were fortunate enough to be hired by bprc to design the project. This led us to contemplate the theories and proposals of Whyte and others closely, learning by doing—which is, of course, the most effective way to absorb and understand many things.

Whyte’s suggestions for amending New York City’s zoning code were equally instructive for thinking about Bryant Park. A great proponent of moveable seating, he also cautioned that such chairs should be a complement to benches and ledges, not a replacement for them. As he specified for the code itself, “Moveable seating or chairs, excluding seating of open air cafés, may be credited as 30 inches of linear seating per chair. No more than 50 percent of the credited seating capacity may be in moveable seats, which may be stored between the hours of 7:00 PM and 7:00 AM. Steps, seats in outdoor amphitheaters, and seating in outdoor open air cafés do not count toward the seating requirements.”36

Whyte wanted to insure that an adequate amount of seating would be truly public—that no one would be obliged to purchase refreshments to sit in a public space, or forced to sit upon the ground (steps, amphitheaters), especially in cold or wet weather. Among other recommendations, Whyte also discussed dimensions for the backs of benches and seats, but acknowledged that backless walls or benches, if wide enough so as to allow comfortable back-to-back seating, could be credited for double the linear quantum as required by code. He was also wise enough to know that what he was trying to do was establish minimum standards for ambience, and that places of genuine quality were often more generous, unique, and inventive, bending and shaping use and expectations. All these considerations would be critical to Bryant Park’s success.

Looking back through my sketchbooks, I found notes from observations I made about Paley Park on 53rd Street that same year. This “pocket park” was one of the spaces analyzed in Whyte’s work. Designed by landscape architect Robert Zion with the assistance of Preston Moore from I. M. Pei’s office, it is an outdoor room the size of the town house that it replaced, with a handsome masonry floor and side walls covered in ivy. A grove of honey locusts pleasingly fills the space, and a waterfall covers the entire back wall in a frothy sheet. There are sitting walls on the sides, twin kiosks that form a

be less attentive to their physical surroundings than ever, immersed as they are in both private and public with digital devices, cell phones, and virtual realms rather than the real thing. At the same time, millions of other people around the world today are struggling with matters of individual and family survival, contending with challenges of the most fundamental sort in their surroundings: drought, famine, flooding. In even the most developed regions of the world, many communities are fragmented by political repression, ethnic tensions, and economic disparities. Still, the need for adequate public space remains a constant as we witness the marches, parades, celebrations, memorials, and protests—both organized and unplanned—that are repeatedly enacted in the heart of our cities, great and small.

We have a need as citizens to be able to be physically together: this continues to be a demand of societies everywhere. And notions of place and identity are central to our consideration of those spaces. The way in which we choose to furnish them reveals attitudes regarding community, sociability, local history, and character. It speaks to where we are in the world, and how we know that we are in one place and not another.

The worldwide adoption of blue jeans and mobile phones, of standardized measures, phrases, vehicles, and inexpensive, mass-produced food, combined with the hegemony of a handful of languages, popular music, cinema, and sports, weaponry, and digital media, have led to a widespread loss of regional differences that has been remarked upon by many. The vast tourist industry of our era undermines these differences, even as it depends on them. By several important means of measurement, including public health, this hegemony has benefited hundreds of millions of people around the world. At the same time, many of these same people have experienced a troubling diminishment of invaluable heritage and sense of identity.

There is a widespread pleasure taken by people around the world in having a particular landscape that distinguishes them and is uniquely theirs. Unfortunately, a created civic space—like any other human product—can be placeless, tasteless, and generic, or it can be particular, full of character, and absolutely local. In our era, when so many individuals and nations are striving to find a way to participate in the modern world without losing themselves and their souls, the landscapes we make can not only resist such losses but also generate new possibilities for community. One humble but particularly effective device in this effort is the manner in which we frame and inhabit our public spaces. Strangely enough, one of the keys to that is how, where, and why we sit in them—both alone and together.