Editors

Lisa-Marie Androsch

Jade Bailey

Adriana Boeck

Velina Iantcheva

Moritz Kuehn

Xavier Madden

Emma Sanson

Patricia Tibu

Viktoria Tudzharova

Editors

Lisa-Marie Androsch

Jade Bailey

Adriana Boeck

Velina Iantcheva

Moritz Kuehn

Xavier Madden

Emma Sanson

Patricia Tibu

Viktoria Tudzharova

The intent is to develop an inspiring and diverse perspective on how the future of architecture will be juxtaposed with other disciplines and expanded to a scope yet undiscovered, achieved by discussing matters of global, social and technological pertinence.

The third issue of Abstrakt is about ecology, defined as a circular and nonhierarchical mode of planet co-inhabitation. As a design approach, it foregrounds the aim to define the spatial conditions for multispecies’, coexistence, codependency and synchronicity, in an attempt to impede the increasing rate of climate interference, treating all constituents as equal stakeholders.

This issue aims to provide different perspectives and approaches and discusses the challenges of how to design non-anthropocentric environments by drawing on this deepened understanding of the systems that architecture is embedded in. The interviews conducted with Sean Lally, Lukas Allner, Elisa Iturbe and Stanley Cho (Outside Development), and Daniela Mitterberger and Tiziano Derme (MAEID) give an insight into their visions of the role of technology, materiality, cultural paradigms and future scenarios. These contributions are accompanied by a series of architectural designs gathered from students and alumni at the Institute of Architecture at the Angewandte that engage with this notion of ecology of the built environment.

Sean Lally is an architect based in Switzerland and a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago. At the heart of his work, he is dedicated to engaging with today’s greatest pressures: a changing climate and advances in healthcare and consumer devices that are redefining the human bodies that occupy our environments. He expands on these interests as the host of his podcast NightWhite Skies

Sean Lally

©Jordi Teres

In your podcast, Night White Skies, you often talk about science fiction. Is there a fictional world you would love to be living in right now?

I started NightWhiteSkiesbecause I thought that the podcast was a great way to meet people, read people’s work, and have conversations that I wasn’t having at the time.

I think that, for the most part, architecture likes to think that its most closely tied profession – to sort of prove its worth and their value – is that of the engineer. We often tie ourselves to the structural, mechanical or the civil, in an attempt to show that we have a kind of professionalism of worth and value. That’s quite real and important, but I also think we maybe have more in common with the science fiction author, because those of us in the discipline of architecture, in a very uncomfortable way, are not the masters of anything. In many ways, we’re the last great generalists of the humanities. If you created a Venn diagram, all these other professions and disciplines would overlap and produce a bounded area that makes up what architecture is. And I think we have a history of trying to create an autonomous subset area within that space that shows that architecture has value by saying, “No, there is a place in that diagram that’s very unique to architecture” – an air bubble in the Venn diagram that we try to designate as architecture. Instead, I like the idea of being able to step back and say that what we do is a little bit like science fiction. We encapsulate many trends and ideas that are a part of all these peripheral disciplines and we synthesize them in ways that none of them would or could ever do independently.

Maybe a kind of quick pick up on something that I’m doing now with NightWhiteSkiesis actually trying to move it onto a video game platform that will make it visual for the audience. And this is something that I’ve been working on now for almost two years, but hopefully by this fall, we’ll start producing these

videos. And these sapces will have designs by me and the office, while conversations happen within them, because I do think it’s important to actually take stabs at imagining what the future will be and try to understand how those spaces operate and how interaction and spatial typologies will evolve.

I wouldn’t be putting so much time into this if I didn’t think it was valuable to speculate on the future through design – not because I’m under the delusion that it’s about getting it right, but because it’s about building a conversation and discourse. It’s about foreshadowing opportunities and limitations that only come about through the synthesis that design is capable of revealing – a little bit like science fiction, which isn’t intended to predict the future, it’s intended to lay out possible or plausible scenarios for the future, just so we have a better grasp of them.

“I like the idea of being able to step back and say that what we do is a little bit like science fiction. We encapsulate many trends and ideas that are a part of all these peripheral disciplines and we synthesize them in ways that none of them would or could ever do independently.”

Do you have a specific ‘storyline’ in your mind that you can see being achieved as a future scenario?

For example, in your latest episode with Adam Frank, “Alien Anthropocenes,” you discuss this idea about our anthropocene maturing past this state of flux into a ‘condition’ of adulthood. How do you envisage this state?

Adam Frank is an astrophysicist and he has just written a great book, about the Anthropocene, which he refers to as the “Alien Anthropocene,” meaning he has performed equations and tests

“That way you realize maybe as a civilization, we are going through a kind of uncomfortable adolescence in the Anthropocene. And we will come through the other side, but any child that would beat themselves up thinking that they were being naive and silly for having adolescence, would be ridiculous. It is just simply part of growth.”

and mathematical modeling based on the likelihood that other civilizations have existed in the universe and that they have gone through Anthropocenes, meaning any global civilization that has existed and gotten to the scale of actually being simply a planet, or even being a multi-planetary civilization, has probably done something that has created an imbalance in their environment and caused it to go out of whack. And according to Frank’s equations, he says this has happened millions of times, so, of course, the question is, will we go over and cause a mass extinction that includes ourselves, or will we rebalance it?

I thought it was such a compelling book and conversation because it almost made me feel… Okay. We are not unique. And it puts me at ease when I realize I’m not unique. Some people get nervous when they feel like there are other things happening or that what they’re doing has been done a hundred times before. But to know that it has happened potentially millions of times already also means that we don’t have to beat ourselves up so much, as it’s almost an inevitability. Take adolescence: if you think about a child becoming an adult, they’re going to go through adolescence and they’re going to do dumb things. Hopefully, they come out the other side, having learned something and grows up and lives a full life. –

maybe have a child that becomes dumb themselves (laughing). It is okay, it is a process. In this way, you realize maybe, as a civilization, we are going through a kind of uncomfortable adolescence within the Anthropocene, and we will come through the other side, but any child that beats themselves up thinking they have been naive or silly just for going through adolescence would be ridiculous. It is just simply part of growth. This doesn’t excuse the atrocities or the greed or the actions of corporations and individuals, but as a civilization, when we think of ourselves as a collective, we don’t have to go to bed having beaten ourselves up. We’re not unique. And I think there’s something to that narrative when you think on the large scale: large-scale solar systems, universes, small or multiple civilizations, or even lifespans of the human species. I think that narrative helps us see things in a sort of broader context.

Within your office and writings it is apparent that you see technology as a mechanism for propelling ourselves towards a better mode of co-inhabitation. Are there technologies being developed that you believe will be integral to this process?

I don’t necessarily look to technologies to fix anything or solve anything, but I will say, avoiding them would be silly. It is a necessity we can’t get around. And so we’re better off trying to guide them as opposed to avoiding or belittling them. I don’t have any great faith that technologies will solve a problem, like a climate crisis or a political or humanitarian crisis. There are many other tools in the tool bag for those things. When it comes to technologies, we need to acknowledge and maybe think about who is in control of them. Maybe that’s the question. The idea that it’s often a capitalistic corporation behind them that is not being honest with their true intentions – that’s what

For example, look back at the skyscraper. It wasn’t just steel that gave us the skyscraper. It wasn’t just the architect’s vision that produced steel or that got us from iron to steel. It was also the elevator. It was that fact that it was a time of commerce. There were a lot of things going on and those combined forces resulted in the novel typology of the tower. And so when we think of the future going forward now, it’s important to think, what can the architect do that is unique, that is actually taking all these disparate forces and seeing them in a spatial manner, seeing how they help people interact with them as a community, as a group of people, as with an environment, as with programs and activities? That’s not something any of these corporations, technologies, research institutes are going to be doing, not if it causes any problems for their business model. So we should be doing that. And we should be thinking, how can we inform future discussions and future research? We should be helping guide that discourse, not simply responding to it. I get nervous when I see that architecture today is worried that we have no ’agency,’ while at the same time it is still embedded in self-referential forms in geometry, because in reality, there’s no better time to be an architect.

The way I would reframe this view would be to say

“It wasn’t just steel that gave us the skyscraper. It wasn’t just the architect’s vision that produced steel or that got us from iron to steel. It was also the elevator... There were a lot of things going on and those combined forces resulted in the novel typology of the tower. ”

that is there’s so much happening now. There are so many pressures. But this is really a great time for architects to be involved and for the discipline to play a role. I think we have the tool sets, we have the modes of thinking, modes of operating. How we create space, design for human interaction using materials, along with how these interact together on a community scale, is something that is so unique to architecture that we need to be addressing these pressures. And quite frankly, to do so is to be messy. It’s about getting it wrong. It’s about making mistakes, a little bit like the science fiction equation. It’s not about getting it right all the time. It’s about simply having the questions in the discipline so that we can move forward.

And so this sort of odd duality of regret, of agency yet continuous self-referentialism of the discipline, it boggles my mind. And I think we’re in this sort of unique period of time where we have to just simply generate discourse and ideas and not think we’re necessarily getting it right, but that we’re simply having a conversation, messy conversations that we can have as we try to move forward. It’s not an easy step, but it’s a step that has to happen. I think we’re still going to be in this process for decades from now.

Is there a way and a necessity to pull people towards a deeper understanding of ecology that not only takes into account the amount of green space but refers also to relationships of coexistence?

When it comes to plants, obviously there’s a coexistence occurring, which has been occurring for a long time, with agriculture: what we select, what we grow, and how we grow it. And now with some of the engineering going on, what corn looks like now in the United States looks nothing like it did a hundred years ago there. And so there is a coevolution that has been occuring... I think Geoff Manaugh posted at some point a short little piece about “Electronic Plant

Life.” Linköping University in Sweden was working and growing various silicon fibers through the xylem of the plant, where it gets its nutrients, and these were conductive materials. By doing so, the photosynthesis of the plant was then actually creating energy. That was then running through the conductive materials that were now in the plant, essentially making it act as a battery. That means that things like forests and plants and gardens could actually end up being sources of energy. It also means that you could store data, much like you do in your hard drive, into plant life. So plant life could become storage devices where information could be held, where information could be moved. We’re talking about plants being places of storing data and information – your home garden, that would become something altogether different. In that example, it would not just be a place of color, color therapy, or scents, smells and views. It would actually potentially even be a source of your energy and where you could store your gigabytes and terabytes of information. I mean, in that case, a ginkgo biloba tree on the street would look the same today as it did 30 years ago, except now it would have a completely different function. Another question would be: would it be an issue that we are now asking it to do something that we hadn’t even thought of or dreamed of asking of

“I think there’s going to be a need for a lot of compromise. And that compromise means if that street plant can both clean the air now as a city street specimen, and at the same time provide energy and still maybe exist as a species of tree that isn’t going to go extinct, is that a good in-between? There will be no absolutes without lots of consequences.”

it 20 years ago? What are the ramifications of such whimsical imagery?

It is somehow a very humancentric way of looking at ecology: to combine it with technology in another way to get something out of it that benefits us. In Donna Haraway’s book Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene she gives us the impression that we should be living with this trouble, we should be even enhancing it, living with the dark places, rather than trying to make all of these dark spaces work in our favor.

Yeah. I think her question is a good one in the sense that I think it touches on two parts: one is, as you stated it, the idea that maybe not all dark parts need to have light shined upon them or need to be corrected or cleaned, and that this is just an aspect of our existence. And then also the idea of “staying with the trouble,” which is just the sense that when things get difficult, we don’t shy away from them, or we don’t try to resolve them, and that these things are where growth occurs and where we exist.

I think there’s going to be a need for a lot of compromise. And that compromise means if that street plant can both clean the air now as a city street specimen, and at the same time provide energy and still maybe exist as a species of tree that isn’t going to go extinct, is that a good in-between? There will be no absolutes without lots of consequences. And I think maybe with that, in “staying with the trouble,” the idea is that we have to be aware of some forms of compromise that are not defeat, rather a form of growth, and not all compromise is welcome and not all compromise is good, but maybe can be less harmful than absolutes.

interview from February 16, 2022 conducted by Jade Bailey, Adriana Boeck, Simon Schoemann

to be continued in the Public Space issue on page 56

“We maybe have more in common with the science fiction author, because those of us in the discipline of architecture, in a very uncomfortable way, are not the masters of anything. In many ways, we’re the last great generalists of the humanities.”

Sean Lally

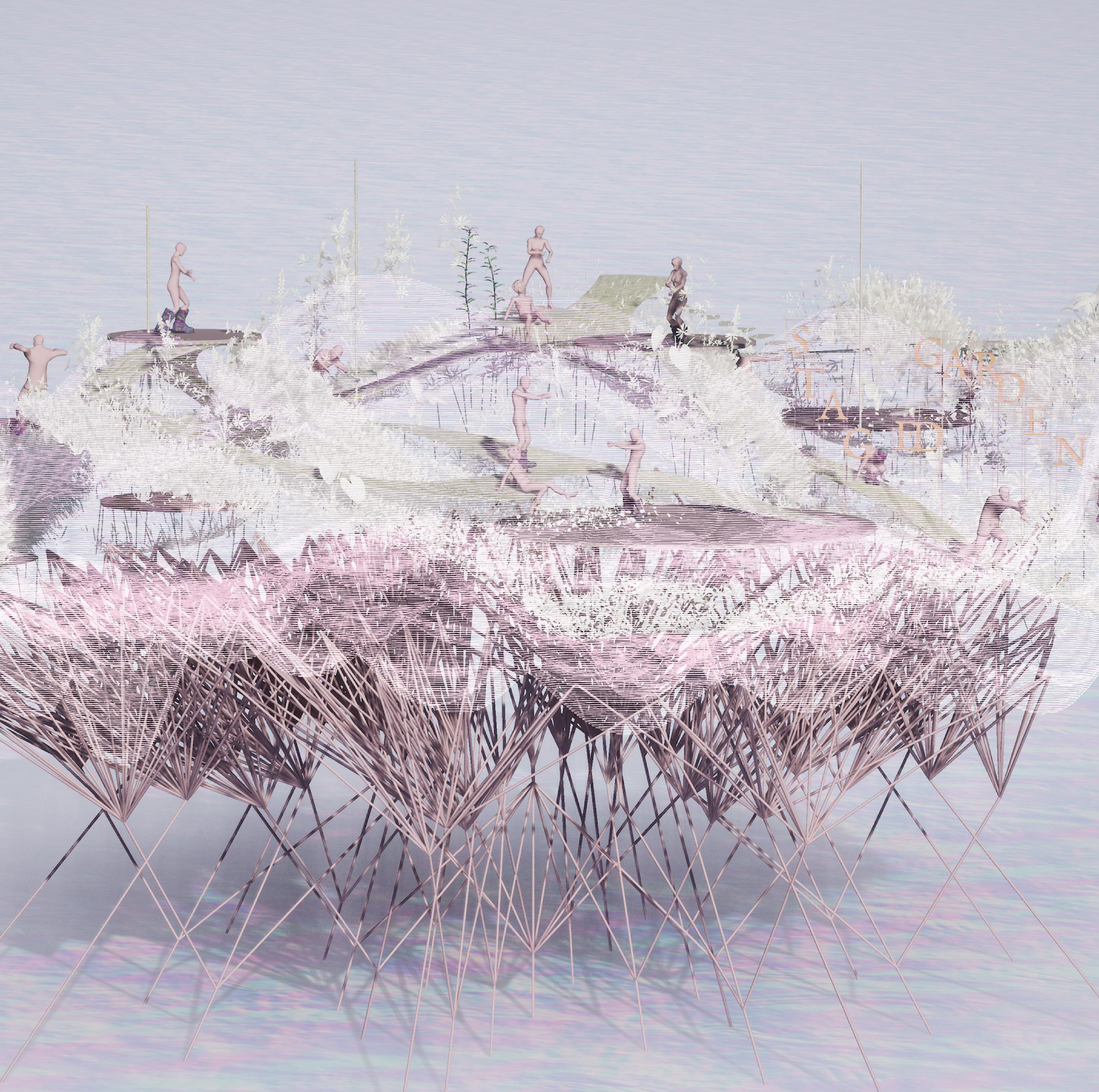

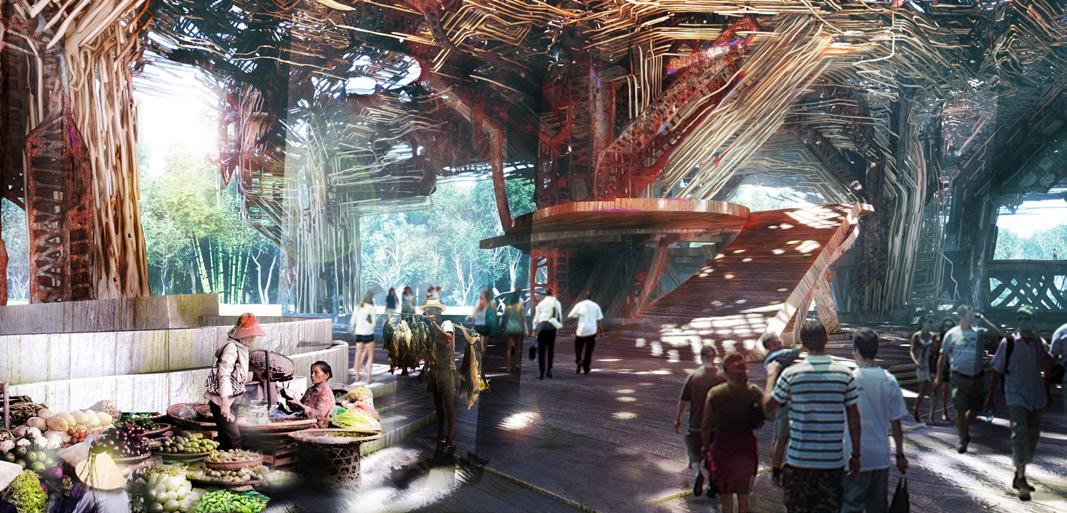

Project by Xavier Madden

Located in Tbilisi, Georgia, this project aims to bring microbes, humans and plants together in codependent relationships which happen beyond scientific labs, instead creating synergies between programs which have complementing constraints, such as a nightclub and production facility of an organic and biodegradable material. It is through these different modes of production that the building finds itself in a constant cycle of growth and decay, as well as sustaining itself as a community center for the White Noise Movement and the marginalized youth of the city.

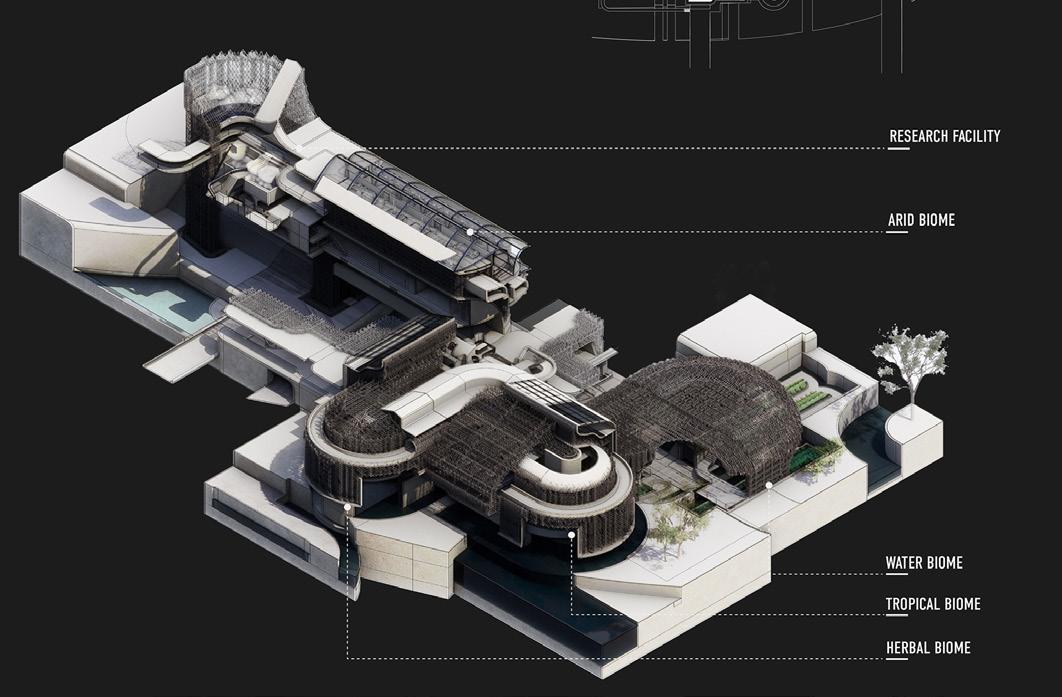

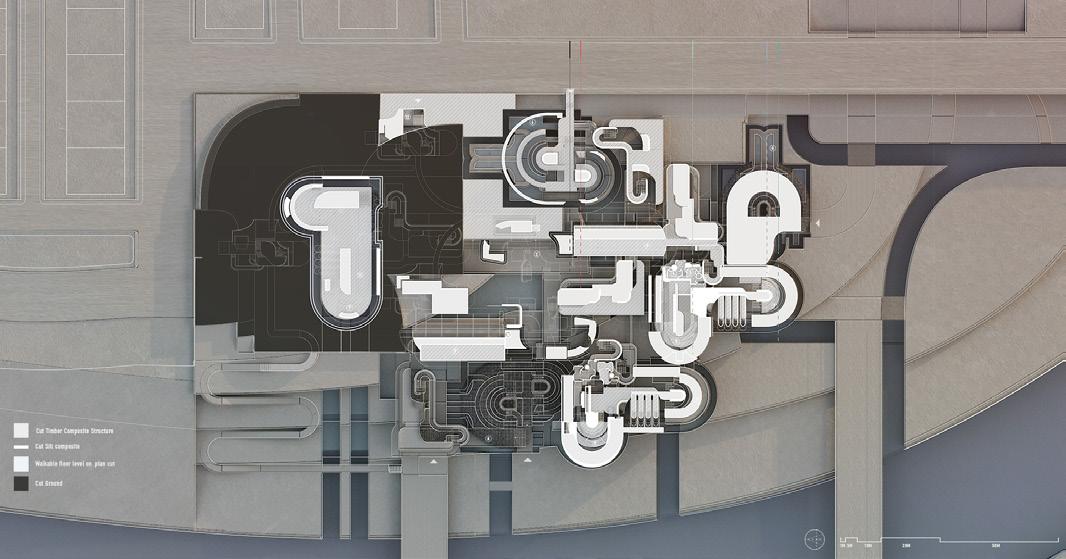

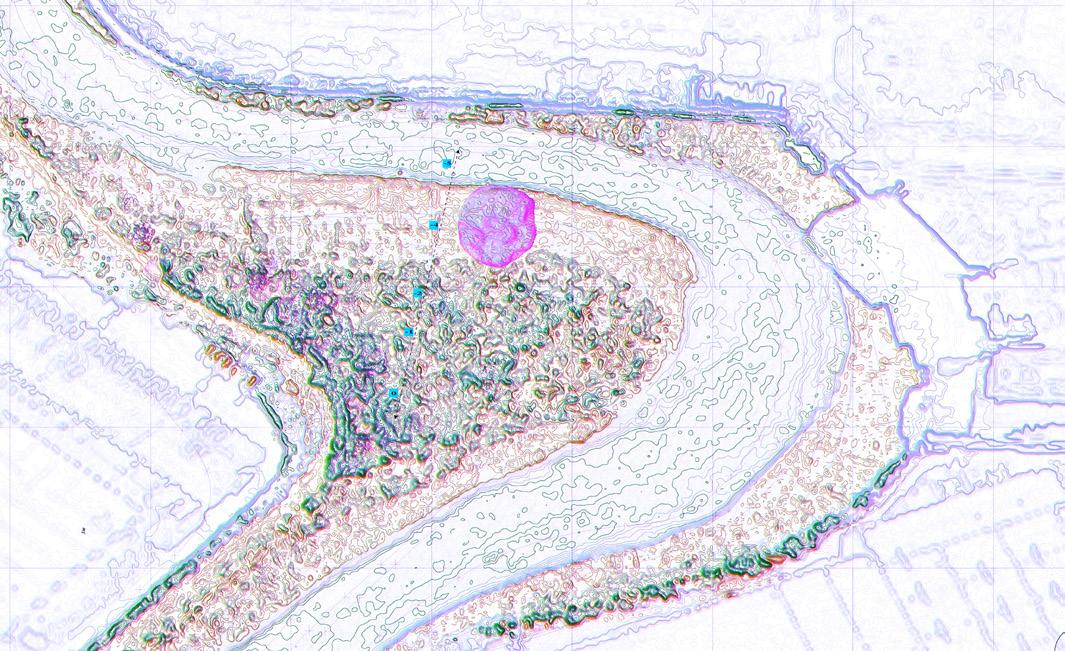

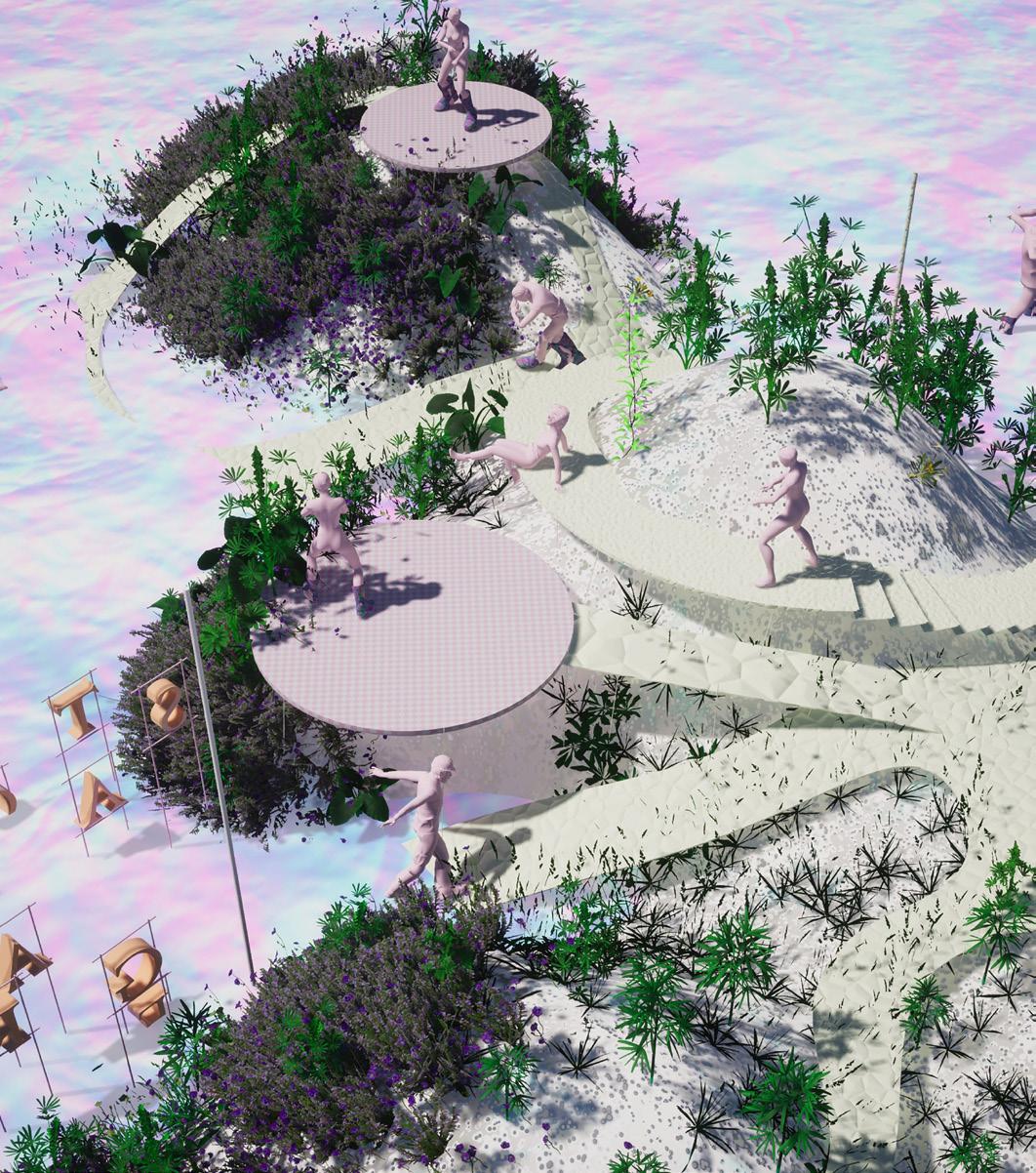

A medicinal plant sanctuary for a pharmaceutical future of Ayurveda medicine in Bangladesh

Traces outlines a concept for a medicinal plant repository in Bangladesh, that seeks to explore the future pharma of combining Ayurveda and Western medicine. The intent is to create an ambassadorial complex where medicine is grown, researched and distributed to the local community, to restore a historic culture of pharmacognosy, within an urban fabric, whilst providing sanctuary for endangered native medicinal plants, which are at risk due to rapid climate change.

The building aims to take on an ecologically sustainable approach by reducing construction emissions to a minimum, through materiality and using passive energy techniques that draw from the natural climate. In doing so, the little amount of energy needed to sustain the building can be generated on site. The building materials are sourced and fabricated locally from traces of climate change, giving the building an essence of belonging and eliminating the aspect of Awayness.

WS21/22

Project by Jade Bailey

(1) (3)

WS21/22

Project by Jade Bailey

(1) (3)

Lukas Allner is a lecturer and researcher at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, as well as at the institute for experimental architecture at the University of Innsbruck. In the recent publication, Conceptual Joining - Wood Structures from Detail to Utopia (Birkhäuser Verlag), he worked together with Daniela Kröhnert and others on experimental approaches towards the design and implementation of wooden structures in architecture and, at the same time, presents the results of an artistic research project.

Lukas Allner ©Mechthild Weber

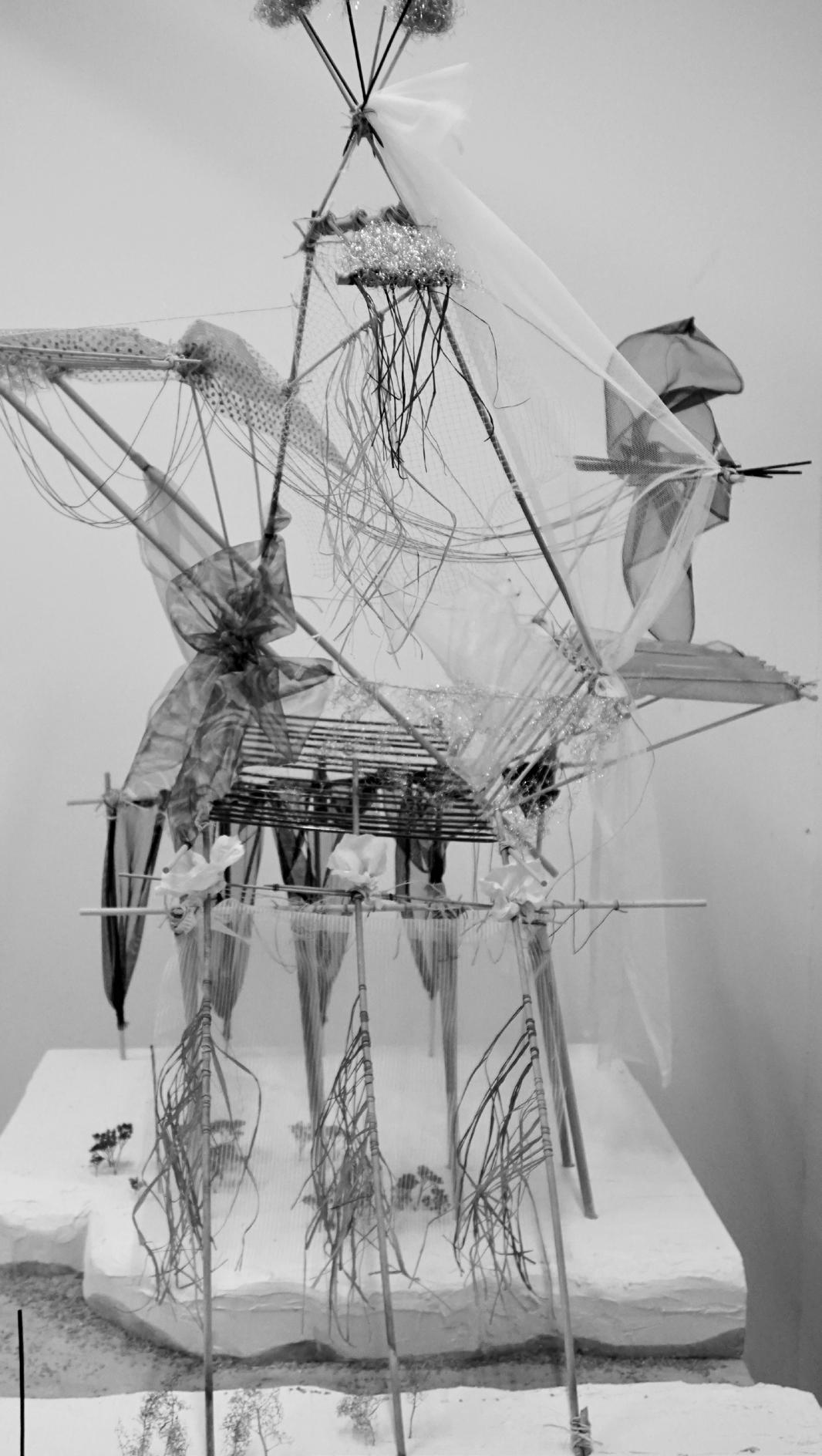

In your recent research project and publication, Conceptual Joining, you investigate material joining techniques for raw wood, where you bypass the traditional process of the conversion of a tree into an element of construction — the material production of timber. Can you describe the motivation behind this research and how certain tools and methods change the way we could approach the design of spaces?

The research question was: How could the immanent logic of wood as a construction material lead to a new understanding of a material-based architectural construction? Using an experimental, open-ended approach, we deliberately refused to find solutions to a predefined goal, such as a function or program. Our motivation with this bottom-up agenda was to find out what happens if we — listening to Hélène Frichot — “follow the material.”

Initially, we were mainly interested in looking into the rich cultures and histories of joinery to find potential guiding principles for an architectural aesthetic and spatial logic. In the process of digging deeper into the characteristics of the material itself, we found that wood in its natural state already comes with its own structural system, by which it is formed. The system of a tree consists of multiple members or structural axes that are ‘joined’ at bifurcating nodes. This led us to another question: Could these naturally optimized ‘joints’ or forked branches be used as ready-made components in a designed/ artificial framework? Especially in the course of industrialization, wood was standardized for the sake of control and efficiency, but wood does not lend itself well to idealization, and today, in the age of computers, it is possible to cope with the complexity of working with irregular building parts. Structures from components that are all different define spaces that are unique, just like no two trees are the same. The logic of these spaces is directly related to the material principles and, if transferred to a functional context, would challenge conventions of use and inhabitation. I believe such a practice would help

change in comparison to designs that are precisely controlled, allowing for only a very small

to empower architecture to be a dialogue partner for its users. Instead of only serving predefined requirements, it induces inhabitants to (partially) actively invent modes of appropriation. Since there might never be a perfect use case for which these structures have been designed, this process will perhaps never be concluded, leading to a lively and dynamic condition of possibly constant renewal. This way these environments could be seen as flexible spaces.

How do you see the role of the architect in the future — do you believe architects need to relinquish some of their control over the final product due to the constraints of particular materials and techniques?

I think the ability to embrace partially unexpected results and an appetite for experimentation could not only help to establish a healthier relationship to one‘s own work, but also open up materialized outcomes to participation and processes beyond a ‘genius mastermind.’ In situated practice, collaboration and interdisciplinary exchange are key, which I think is important in shaping — ecologically and socially — sustainable architecture. In regard to materials and techniques, I also believe that concepts that allow for a threshold of more-or-less, a range of possible outcomes as acceptable results, are more robust and open to change in comparison to designs that

“I believe that concepts that allow a threshold of more-or-less, a range of possible outcomes as acceptable results, are more robust and open to

margin of imprecision.”

are precisely controlled, allowing for only a very small margin of imprecision. The challenge with this is of course to balance or mediate control and to adopt the unforeseeable, to find a productive middle ground between order and chaos. Furthermore, I think that in this more-or-less approach to materializing architectural concepts lies potential for feedback and a mutual relationship between the virtual design and the physical realization.

Your approach towards the goal of a circular mode of practicing architecture involves questioning methods of building construction and material use. In your opinion, what are the cultural implications of this agenda? As architects, how can we instigate a shift in thinking about the natural world and our place within it?

We have to understand ourselves as part of a continuous process of change and transformation and, as architects, we have to foremost overcome the idea of creating buildings as eternal monuments, and instead think of them as transforming ecosystems. That means thinking beyond design and including into our thinking what was there before the design or project and also what will come after. This adds

another level of complexity to our work which (in real life/practice) we cannot handle by ourselves alone. We need interdisciplinary collaboration and teamwork.

Where do you see the biggest potentials in breaking a linear economy and aiming for a cyclical approach in architecture and urban development?

In the context of reusing building parts, I think two of the biggest problems in achieving a cyclical model are hampering regulations and construction-related laws, in combination with warranties for construction materials that together still foster a linear, capitalistic model. It is very difficult and often legally risky to use unconventional or innovative materials that don’t have a long history of documented applications. In the area of reuse, for example, it is very challenging but technically possible to identify quality standards of building parts from a demolished building. This is why contractors typically don’t offer warranties for reuse in a new building. In comparison, newly fabricated components run through quality check routines. However, I believe there is a huge potential for new business models that address this issue, especially when prices for products from raw materials would include the real costs for the planet, such as the long-term ecological effects of their fabrication and transport, carbon emissions, costs for disposal, etc. Much higher prices for such products would make reuse and recycling economically more attractive. Another aspect is globalization, we have to think more locally and use materials from close by as much as possible.

I don’t have a favorite material, because I strongly believe in the context dependency of a choice of

material, the context of project-dependent intention, function, location, availability, accessibility and cost. I don’t believe in universal solutions.

The integration of living organisms into architecture is a fascinating field that has been investigated by researchers such as Ferdinand Ludwig and Phil Ayres, but our focus was to question established wood construction practices on similar grounds, by using part-based systems that can be dis- and re-assembled. This also allowed us to operate within much shorter time frames.

In our upcoming follow-up PEEK project, “Inventorics,” we will expand the material palette beyond wood to further develop these ideas. Digital tools including CNC fabrication practices allow us to consider nonstandard materials for construction. Such materials could also include demolition debris, industrial

“

artifacts or trash, which would significantly expand the field of reuse and offering creative potentials at the same time.

By specializing in one materiality and the raw fabrication of this very natural product, do you see a potential there to ease the settlement of other species into artificially built environments?

Wood is generally vulnerable to moisture, which accelerates rotting, and interaction with other species usually involves water. In a forest, dead wood is very quickly populated by different species that effectively eat it to help close the circle in the ecosystem. Unless we want or accept fast decay of a building, wood is probably one of the worst materials for incorporating plants and animals into the structure or facade. It would probably require more durable materials for such a cohabitation were to last for a period similar to the common lifespan of a building. I am not an expert in this area, however, I find it a very interesting thought.

“We have to understand ourselves as part of a continuous process of change and transformation and, as architects, we have to foremost overcome the idea of creating buildings as eternal monuments, and instead think of them as transforming ecosystems. That means to think beyond design and include into our thinking what was there before the design or project and also what will come after.

Daniela Mitterberger and Tiziano Derme are architects, media artists, and researchers at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, as well as current PhD researchers at ETH Zurich. Together they founded MAEID, an interdisciplinary practice that questions the relationship between the human, space and performativity. Their work can be understood as a seamless interaction between computation, the material and virtual, living systems and machines. Their recent project, Magic Queen, was part of the Venice Architecture Biennale 2021.

Your recent work Magic Queen uses a new 3-D printing method with soil that you have been researching and developing. Can you describe the motivation behind this research and why new construction methods and materials are needed to support future ecologies?

Daniela Mitterberger: For MagicQueen, we were using soil, which is a very interesting material, because it’s a substrate, which means it’s something that allows you to actually grow life, so it’s something that is not a dead entity.

We have this urge to produce, and when we talk about ecology, we talk about creating architecture that is not in contradiction to the natural environment. We believe it’s very important to actually be a truly biodegradable and sustainable building, which includes, of course, multiple steps. Especially in digital fabrication, we often hear this idea of sustainability of processes, but with soil, it really allowed us to be biodegradable throughout all the steps. So that means that throughout the whole process, we can actually reuse the material later. That means, even though we build architecture with it, we build a landscape with it, you can put it directly back into the garden where you got it from. Soil is a granular material, it behaves differently and it allows you to create complex forms at the same time. It makes it possible to be sustainable and host plants and other species within your environment.

I think that that is the super important thing. It changes how we see and understand architecture, because suddenly, it is not just a shell that is encapsulating us, but it’s actually more a medium for negotiating our presence with the environment.

Tiziano Derme: For the first time, we really approached a scale of production and fabrication here that was quite ambitious. Because we are talking about almost a hundred tons of compressed soil and a robotically, fabricated structure, which is actually confronting this kind of use of robotic fabrication

of these new materials with a currently existing problem: How do we place these kinds of current biotechnologies or new ways of manufacturing on a scale that is beyond the lab scale? There is a lot of very interesting research, including that which we are currently doing, taking place here at the Angewandte with the Co-Corporeality project. They are having difficulty scaling up because of very specific requirements for the environment in which those structures of materials are being placed, as well as in terms of the complexity of processes. To make a large structure of concrete in terms of fabrication could be understood as a quite straightforward approach. But what if you have solutions that get contaminated and you have liters and liters of solutions that need to be prepared? What if the material dries too quickly? What if the material is highly responsive to environmental fluctuations, such as humidity or temperature? With this project, we wanted to confront ourselves a little bit with a different scale. What is really problematic in terms of a kind of larger picture for architecture, is the relationship between the architecture and the natural phenomenon, which was always a very problematic one, so if you understand architecture as something that is embedded in an environment, but as a kind of act of betrayal of the natural environment at the same time. Therefore, we need to contextualize critically: What is this natural relationship between how we assemble materials and how we consume or tend to natural resources?

“It changes how we see and understand architecture, because suddenly it is not just a shell that is encapsulating us, but it’s actually more a medium for negotiating our presence with the environment.”

Your projects often bring together both natural systems, such as soil and plants, and artificial systems, such as robots and AI, into one single environment. The relationships created between these contrasting systems in your work challenge our understanding of natural environments. Do you see our understanding of nature blurring and how would you define it?

DM: We have to be very careful when we use that term ‘nature’ because it is a term that has been widley discussed over and over in theoretical and built works. It’s something that we have to redefine continuously, especially in our times, we have to redefine what it means. This idea of ‘wild nature’ doesn’t exist anymore. We know that there are cultural landscapes, created only by us humans. This understanding of our influence on the natural environment is something that is starting to become more common knowledge. The more it becomes common knowledge, the more we are starting to understand that we are dealing with complex systems. At the same time, we are already interacting with them. That means we are already shaping them, so we better start to learn what we are doing faster. It’s a big job for the architect to start

to understand this. It also means incorporating the complexity of systems and ecological systems, this idea that machines are generating natural environments or being used to produce natural environments. We want to use machines, especially robots that are normally used to automate things, but we don’t want to use them to automate or control nature, but to actually produce a nature that is independent, that means nature can actually evolve by itself. And we have the technology to do that, it just depends on how you use it. Currently, we are using machines and landscapes to control soil, or control nature. That means that we have the feeling of control, but we are not looking at the long-term. We are more interested in creating environments that can sustain themselves or create something new: this kind of idea of a new ‘wildness’ that is generated by incorporating machines, and that these machines are then stimulating specific ecological processes or natural processes in the systems. And by doing that, we are actually creating an architecture that is not in this juxtaposition to nature or solid or opposite forces of, you know, human versus nature. Everything has an influence on each other, all agents are working together. This really works by just first isolating it and simplifying the problem, and then starting to bring the complexity of systems back, slowly incorporating more agents and more things. For this approach, we need to use materials and systems that allow us to do this. We use AI because

“We want to use machines, especially robots that are normally used to automate things, but we don’t want to use them to automate or to control nature, but to actually produce a nature that is independent, that means nature can actually evolve by itself. “

it allows us to learn without requiring our immediate input. It can use robots because they can work by themselves. They’re self-sufficient and at the same time, they are able to actually react to changes. It is very important to say it needs to react, so you give up control. You might set up a system or a framework, but you don’t have 100 percent control over what is happening. That means it might not grow. It might be contaminated. It might lead to a different result.

TD: Maybe I can add some reflections on the terminology. At the moment, when we talk about nature, we make a distinction between nature and our position. This results immediately in us talking about nature as something that we are not part of. This is the first very problematic use of the word. So first of all, the word “nature” was coined by Ernst Haeckel, and the way he described it was as this kind of dynamic exchange between living creatures and also the relationship between them and the environment, so it is something that is highly relational. And this, from our perspective, immediately falls into how we place technology within this.

Technology is also a very, very relational construct. Technology does not exist in a vacuum, it always plays critically with cultural context. And this is what we are trying to do, to mediate ecology through technology. That’s also what Daniela mentioned before, and this is what leads us to reflect on terms such as this idea of ‘wildness,’ which is very different from ‘wilderness.’ So if something is wild, we normally associate it with something that is very far from any human presence, which depicts this image of, untouched, nature, but in fact, ‘wildness’ refers rather to a behavior. It’s a behavior of a very specific living organism or environment actually. So that is defining a sort of a system of rules and relationships. So this is what we have experienced somehow with blurring the limit between what is natural and what is technological, which is very different from using technology to maintain or domesticate an environment. Agriculture was the very first example of the domination of nature. Also, the garden is actually a spatial construct where nature is domesticated, in common terms. So now, when we use the term ‘garden,’ it is actually used to discuss this relationship.

(1) The Eye of the Other, 2021 ©MAEID

(1) The Eye of the Other, 2021 ©MAEID

Has art been a better and easier medium to translate your ideas and visions and to communicate them to other people? Do you have the desire to translate your projects outside of exhibition spaces?

TD: Generally, the practice, for us, is a very expanded domain of action that doesn’t fall within a boundary where we need to defend the fact that we are architects. I’m not worried. I think also, Daniela, you’re not worried at all, when, you know, they call us artists. I think we should not be scared of this. But we should try to place our work within different contexts and today, especially as a young practice, this means expanding a lot of the domains of action, which are sometimes videos, sometimes installations, sometimes buildings.

We have projects that are dealing with a different temporality. The exhibition is something that exists in a very specific timeframe, while the building, as we normally understand it, exists forever. And this is also something that we would like to question as well. How long does this architecture need to last? And of

course, we have the intention to expand what we do outside the exhibition, but in terms of temporality, not in terms of doing a building for the sake of doing a building, but more as a kind of form of exposure.

DM: In a lot of our exhibitions, we never exhibit the same things twice. So we always use an exhibition as a driving force to push a project further. Exhibitions are actually these moments of coming together with people and discussing them and the most interesting discussion points actually always come up when the things that we are producing are at the build-up phase. All of the projects we produce are really sitespecific, they’re produced on location and have a build period that is essential. And actually, during this buildup period, we have a lot of architectural discussions with people related to the project. And this is also a mode of generating knowledge for us, because you don’t just discuss the final object, you discuss the whole process with people that normally don’t link a process to architecture. People forget that there is a process related to the build-up. We love to see the final object, but the moment of

building it up, growing it, producing it, being involved in it, and having to make the decision of what is done by a machine, what is done by a human — all these things are in an exhibition because you have to do them. You have to produce an ecosystem that takes time, that takes love, that takes care. It allows us to expand a discussion on architecture on a lot of different levels. It challenges us because you have to be active and knowledgeable in a lot of different areas and fields. I think that’s also something that keeps us active and allows us to combine a lot of different types of knowledge from many different fields.

What would you see as an honest alternative to today’s constantly referred-to notions of ‘green,’ ‘sustainability,’ to avoid ‘greenwashing,’ in the context of architecture?

TD: MagicQueen is very dark, black, it’s not ugly, it’s not pretty, which actually led us to interesting discussions with a lot of visitors as well, not only professionals, who understand the ‘natural’ as something ‘green.’ And this is a cultural construct that we constantly deal with everyday. And it’s problematic. Personally, we don’t have a formula for getting out of this, but I think we have the opportunity and somehow

the chance to critically engage with it. In reference to the Glasgow meeting that just happened, the COP26, there was a very interesting project that was initiated by the leader of the band, Massive Attack. They put up a platform to track all the advertisements, all these kinds of greenwashing. I think it was the first time that it had ever been done. To really understand the dimension of this issue, we should start to critically engage to make it evident first and then start to reconstruct our way back.

DM: It’s a very difficult topic, because it’s very political. You can never say how to prevent greenwashing from happening. The moment you have it as a selling point, people use it. The moment that you put two, three trees on a roof and that gets you ‘in,’ then yes, of course you do it, these excuses we come up with how to make something sustainable, placing some trees here, producing some oxygen. But to actually allow to be created, this little bit of oxygen, this little bit of green, you end up using so much energy to do that, that you kind of eradicate whatever you promised before. The ground rule for everyone should be to build a very sustainable building, in the best way possible. It should not be a, plus point, anymore. By taking that out as a ‘plus point,’ you take it out as an excuse to defend something that might be not sustainable in its essence.

I think one big thing is also to discuss this idea of, do we need to build buildings that stay forever? We always want to design our buildings so they live on like the pyramids for thousands of years, but this is not our reality anymore.

“In working with biological materials and new technologies, you will fail. But there’s a beauty in a failure that you really need to acknowledge and that makes you push ideas and thoughts further. And by doing that, you automatically adopt a more holistic approach because you go from one question to the next one. “

“You have to produce an ecosystem that takes time, that takes love, that takes care. It allows us to expand a discussion on architecture on a lot of different levels. “

What would you tell the next generation of architects, how could they approach design more holistically in order to work towards future ecologies?

TD: To think in terms of a more complex context for architecture — not complex for the sake of being complex, but because we cannot isolate our critical decisions from the context in which they are placed. Which brings us to the questions: Why do we need to build? What do we need to build? What does it mean to build now? So for me as a young architect, I think we should question the medium, expand the questions of architecture, and also find and create a context for the projects.

DM: There’s also the question of, what is architecture? We don’t seem to ask this question anymore. Like, what is architecture for you personally, now? It’s not just about what you have learned, but when you look at what is happening in the world, at the technology, the knowledge we have — what is architecture then? Just by asking these questions, starting a project like this, you get to a different point or different result.

This question of what architecture is nowadays requires agility on behalf of the architect. We need to be way more knowledgeable in a variety of fields, we need to see and almost hunt down things that could be interesting for us as architects. Going to other fields where we say, this is very interesting — this is knowledge that should come into architecture. This requires that we broaden our horizons to other fields, talk more with other fields and other disciplines, where we can really ask, what does it mean to do what we do? What’s the impact that I have when I do this and for whom am I building it?

I think the development of new approaches to architecture is a braver approach than going backwards and picking up topics that have already been discussed, because to just carry them over to our timeframe now might not be fitting anymore, we have evolved and we continuously evolve.

So we need to push this further and actually try to find new approaches to how we can do it and what it means for us to be architect, nowadays. And I think for that, you need to be brave and you must not be scared of failure and actually even find the beauty in this failure. In working with biological materials and new technologies, you will fail. But there’s a beauty in a failure that you really need to acknowledge and that makes you push ideas and thoughts further. And by doing that, you automatically adopt a more holistic approach because you go from one question to the next one. That’s a very potent way of doing architecture: if you don’t end up with a solution, but end up with more questions and more problems, because then you have created a machine of productivity where you say, okay, you’re trying to reach a final solution because you understand that the final solution simlpy lies in the production of a new, novel system. It’s not easy, but I think it’s fun and it requires a change in how we work and how we design.

interview from December 21, 2021 conducted by Lisa-Marie Androsch, Moritz Kuehn, Xavier Madden

“It changes how we see and understand architecture, because suddenly it is not just a shell that is encapsulating us, but it’s actually more a medium for negotiating our presence with the environment.”

Daniela Mitterberger

diploma project

La Cité de la Foudre is a periurban approach on the riverine farmland between the outskirts of the capital city Kinshasa and the Congo River. It consists of six vertical structures, all of which relate to different meteorological phenomena, animistic characters, and programs. Collective spaces for the expression of ritualistic and agricultural performances invite people to go out into the fields at night and under any weather conditions. The Counter City concept features a porous occupancy system for public gatherings on an acupuncture scale. Entering the marshland should no longer be associated only with essential agricultural activities, but also with cultural and festive occasions, overcoming uncertain perceptions of atmospheric forces.

WS21/22

Project by Carmen Egger

(1)

WS21/22

Project by Carmen Egger

(1)

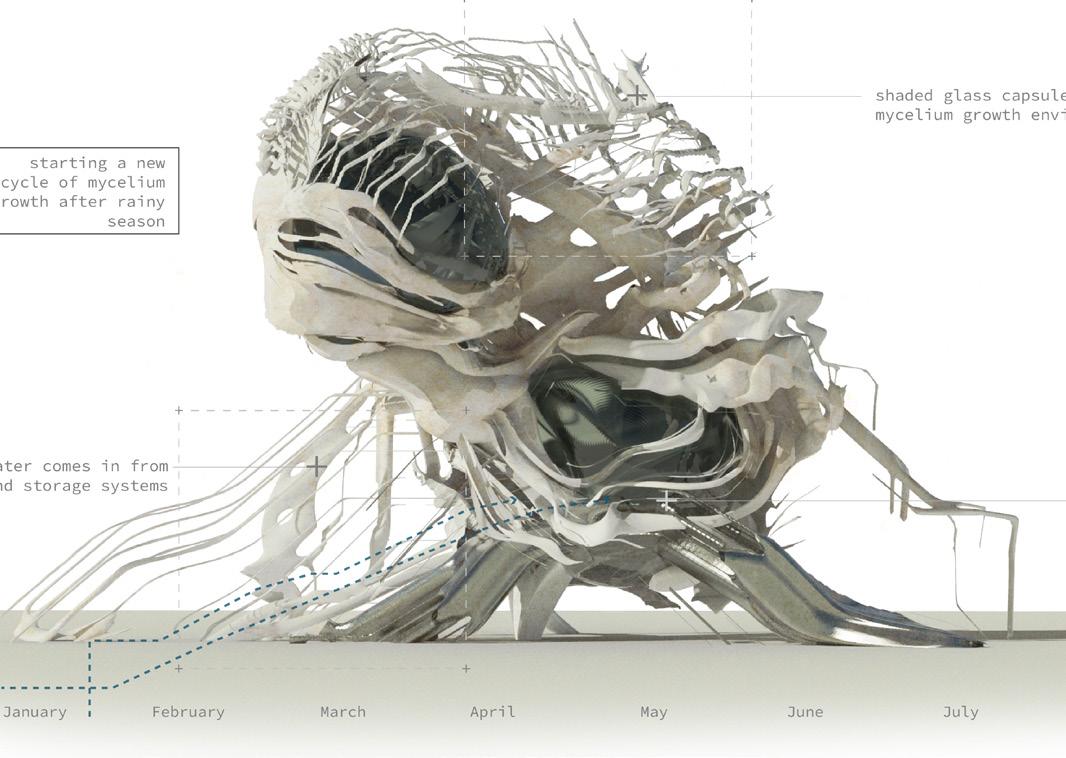

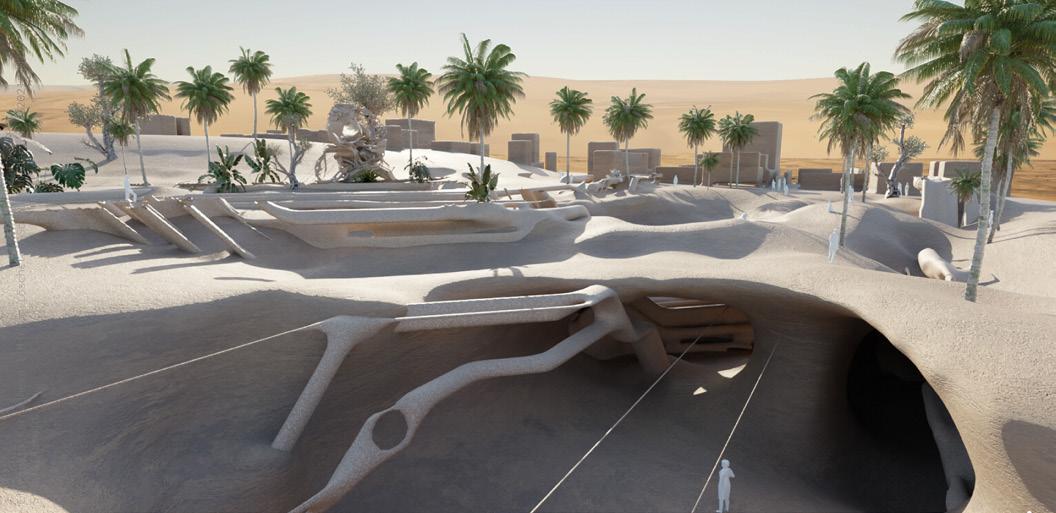

Considering the problem of desertification as a point of departure, this project is not about fighting climate change, but instead about learning how to coexist with it and use it as a driving factor. With the use of solidified sand, the dune barrier is preserving the city from the Sahara, while creating recreational areas, which are semi-shaded, as is the architectural tradition of the region. Providing a shelter from wind, sun and sand, a pathway alongside the border with the desert is the perfect place for leisure activities. By storing and directing the water available from the annual flood of the river, the water system helps the irrigation and greeneries. Condensators are low-tech devices located in the irrigation areas which utilize the water cycle and grow mycelium-bound shading structures in the rainy season from desert shaggy mane mushrooms. While drying the final product, water is condensated and brought back to the vegetation. These systems work together and try to not only ensure a more pleasant environment for humans, but also to stop (and hopefully reverse) the negative impact of the current climatic situation in desert regions.

WS21/22

WS21/22

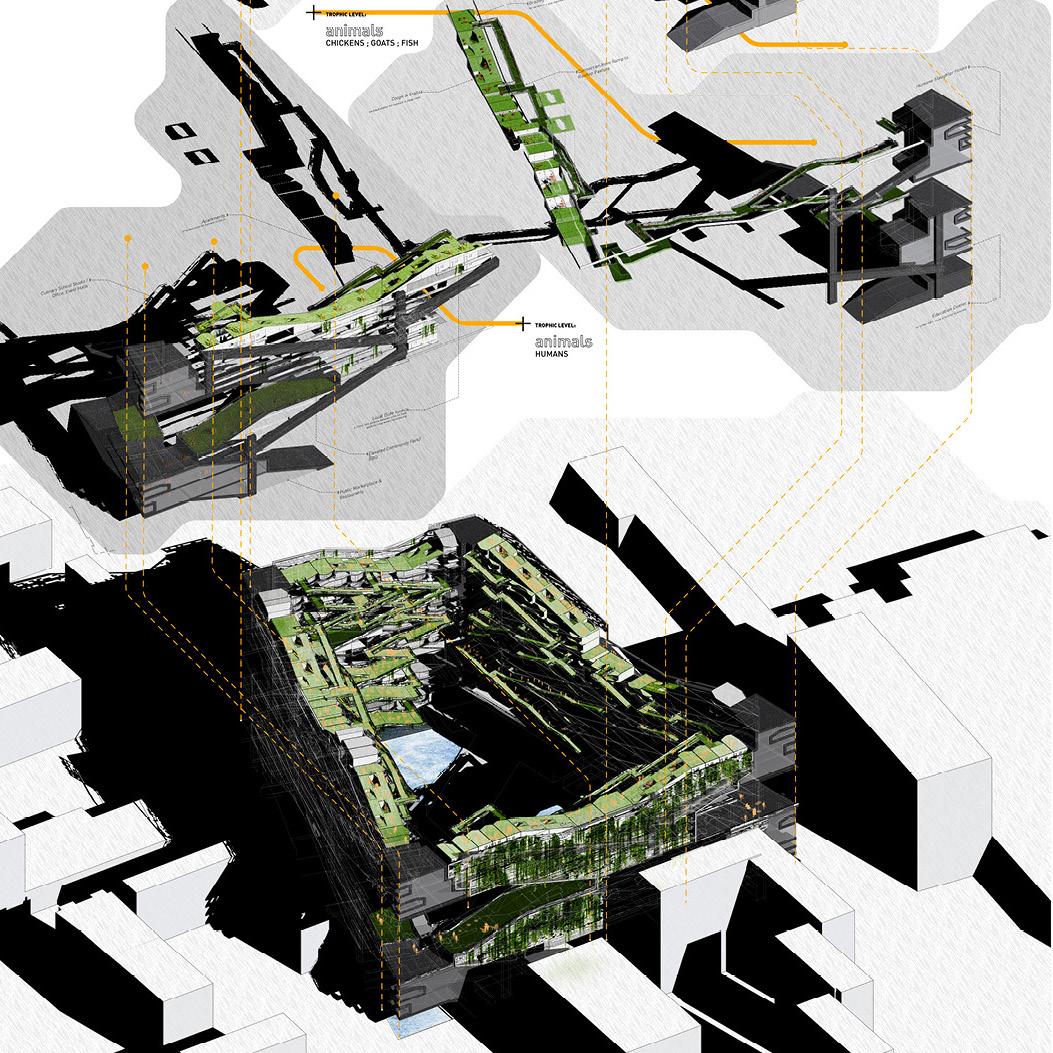

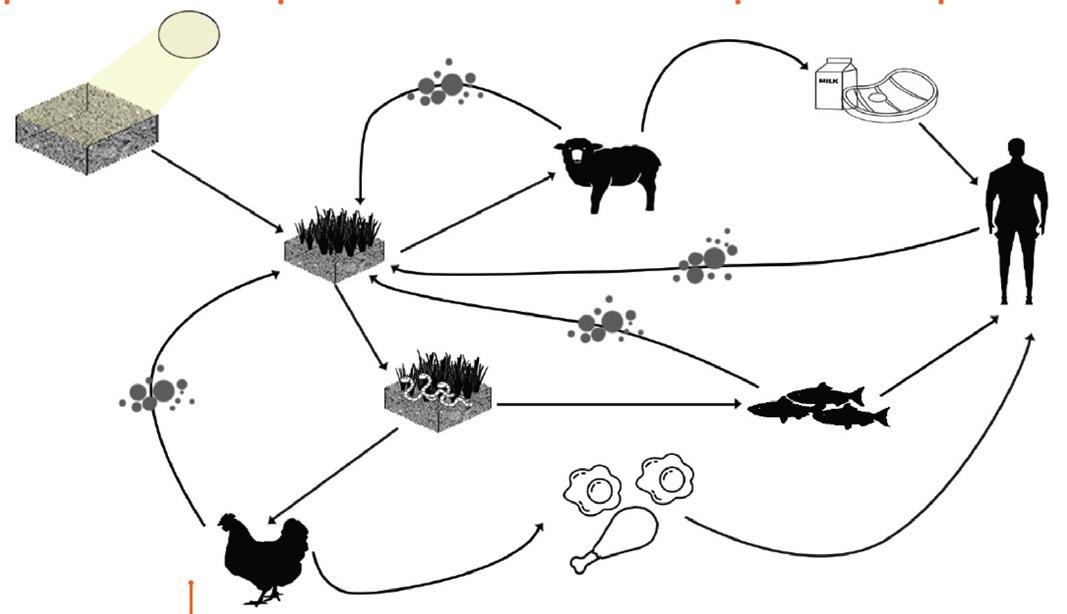

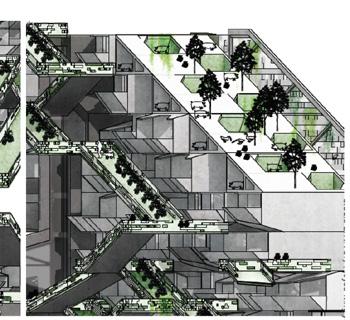

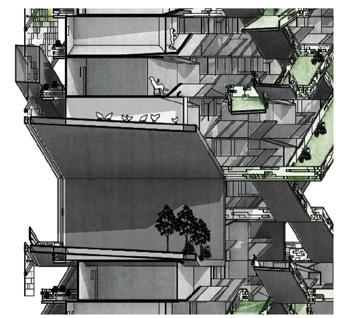

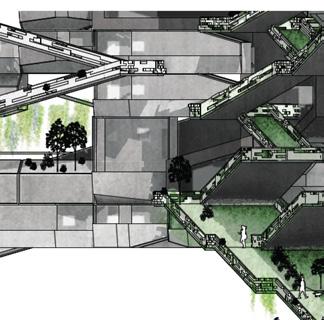

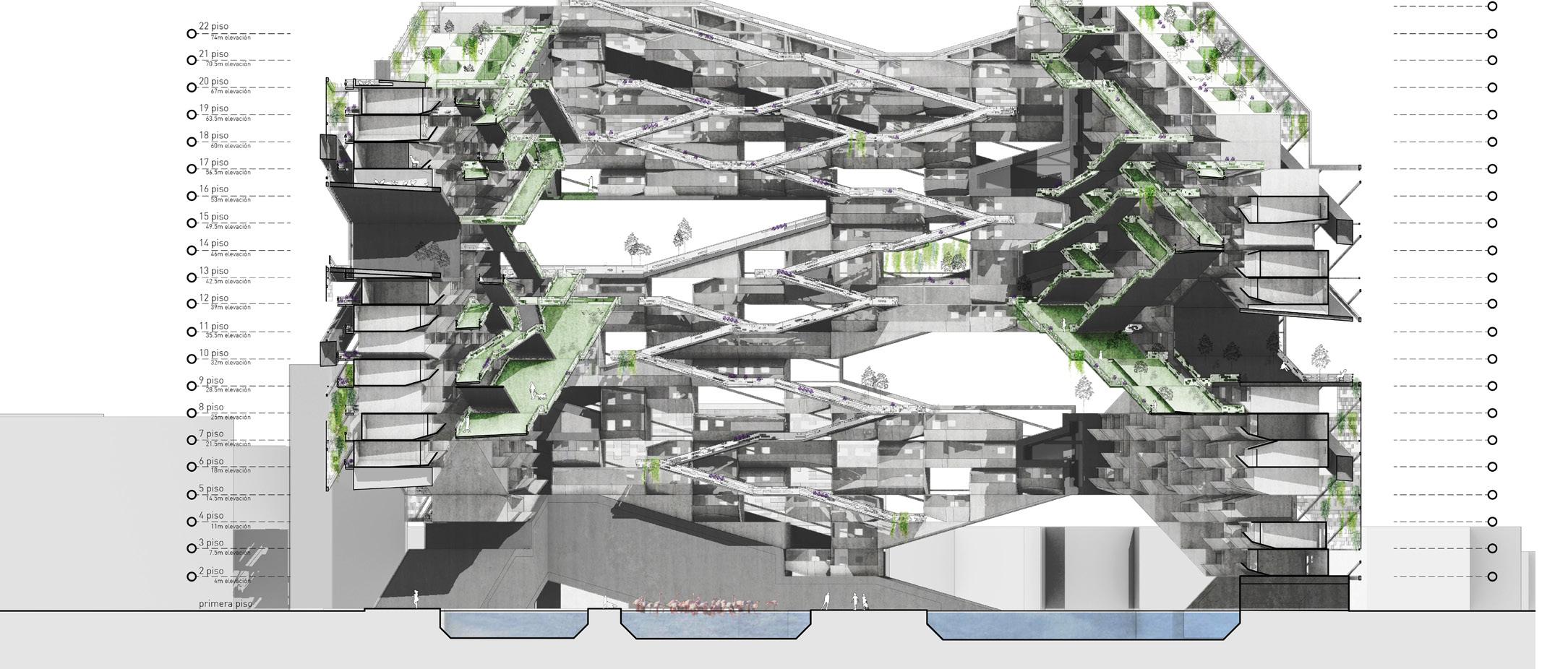

700-unit mixed-use residential tower in Madrid, Spain

We sought to develop a new typology which is a 50/50 blend of a high-density, urban, mixed-use landscape and a rural agricultural landscape. We proposed a radical interpretation of amenities typically associated with large-scale residential towers. The tower, thin and porous, is wrapped in an artificial landscape, creating an interconnected ground condition on every level. This ground, highly coveted free space in the city, presents opportunities for parking spaces and urban agriculture. In this manner, the form of the building responds to and creates affordances for multispecies cohabitation, presenting an alternative model of urban density and public space.

SS19

SS19

In ancient Athens, the happiest person to ever live was a man named Tellus. He was famed for his honorable life and treated with respect and admiration. His Roman namesake, Tellus Mater, (“Earth”), and the Greek counterpart, Gaia, were praised and worshipped as personifications of Earth itself. Treating Earth like a divine human, these ancient civilizations were aware that their actions had repercussions and lived their lives accordingly. With this respect for nature’s boundaries for the planet as a general rule of conduct in society, people and nature lived in a symbiotic relationship. Crops and prey were grown and hunted seasonally, habitation depended on the resources in the area, and natural phenomena such as storms and droughts were believed to be Gaia herself expressing her dismay at how the people were treating her – often resulting in offerings, more prayers, and reconsiderations as to whether the current practices were sufficient for their gods. Being at the mercy of the elements, the civilization of the fif century BC had a minimal impact on the planet compared to that of today’s overconsumption – like the other species cohabiting on, under and above the surface of the Earth, homo sapiens were simply another organism thriving on the fertile ground of Gaia.

Time and time again, Tellus has been proven to be happy and perfectly self-sustaining, as was seen in the aftermaths of dramatic events such as the Pompeii eruption or the Shaanxi earthquake, as well as more modern disasters like the 2003 heat wave or the partly man-made incident of Chernobyl. Today, the fauna and flora flourishing in the area surrounding the Ukrainian nuclear factory shows perfectly well the incredibly adaptive and healing abilities of the planet. It does not need humans to perform specific tasks for it to thrive – however, like a person, it does need

their respect. And for the longest of time, mankind held on to the esteem they had for the powers found in nature.

For centuries, humans, like other species, spoke the language of Gaia. Like seagulls seeking land for shelter in the silence before the storm –humans read the warning signs of nature and acted thereupon. They knew that overharvesting would lead to not only their own dismay the following year, but it would also disrupt the balance in the ecosystem surrounding them. Taking a step back to ancient Athens, Mr. Tellus lived a healthy life, respected for his honor and his kind children, the sum of which made him happy. Should his namesake Gaia be viewed in the same manner, a personification of Planet Earth, it could be said that as long as the ecosystem is balanced with no species dominating the other, like misbehaving children, she will remain happy and healthy. However, as recent years have shown, this is no longer the case. As humans enlightened and invented, they developed more advanced techniques to defend themselves against the elements, and such also against natural warning signs. As a consequence, similarly to the bodily decay of a person falling into depression, the planet is today showing severe symptoms of a no longer happy and balanced system. There is no longer a dialogue between Gaia and humanity. Like spoiled children, the people of the Earth have taken more than the planet can manage to replace, ignoring all warning signs. No longer seeing Gaia as a divine entity, but as a hostile land in need of taming, humans have taken possession of the surface of the Earth, as well as the air and the oceans. With a diminishing range of species in all categories, and a more and more monocultural environment slowly tearing itself apart, humans have industrialized themselves into such a broad definition of habitat that, no other species have any rights any longer to the surface of the Earth. However, unlike the ancient

Greeks, humans today are no longer planning for the following year, e.g., sparingly using their resources so that it will last until the next harvest without affecting it. Today, they already know that Earth is a lost cause. Thinking further into the future than any generation before, people have set their eyes upon space, dreaming far beyond of their own lifespans. A common denominator for all future visions of the species, as Carl Sagan explained in his “lost” 1994 lecture, “Age of Exploration,” involves humans placing themselves at the center of life, the universe and everything.

“We’re in or at least near an obscure spiral arm 30,000 lightyears from the center of the Milky Way Galaxy, in the galactic boondocks. If you were an intergalactic traveller coming into the Milky Way, what would you think of someone who said, Excuse me, Captain, that’s the center of the Milky Way, that’s true, but count out spiral arms with me. There is one. There is another one, big and beautiful. There is another one. Then over there you see that somewhat obscure spiral arm. Well, don’t look exactly in it, but just a little out of it. See over there? I know it’s hard to see. Take a closer look. Right, right there? No no, not that one! That one! See? Yeah? Yeah, The guys who live on that one say they’re at the center of the universe and the entire universe is made for their benefit.” This culture of egocentrism has grown significantly over the last few years, heavily influenced by strong political factors in the global game that is capitalism. Joined in 2019 by a new key actor, the pandemic, it seems that the current trend is no longer one of respect and compassion, but one of publicly proclaiming both bigotry and indifference towards the suffering of others. In an era of post-truth and post-politics, where authenticity is decided by whoever owns the media, the human species is no longer a harmless epiphyte living in harmony with Gaia. They have become parasites. James Lovelock

argues that Earth itself is thriving, happy, when it is in equilibrium. Just like there was a correlation between Tellus’s perfect life and his happiness, there is a cause and effect relationship between Earth’s ability to stay healthy and the level of human interference with its ecosystem. When there is a coevolution of environment and life, an unconscious homeostasis, the sentiment of Gaia can be personified as happiness.

With Earth slowly being rendered uninhabitable by human consumption and space still being the place of dreams, the current state of human occupation of the Earth’s surface has become a battleground of varying ideologies and values. Today, a person’s value commonly depends on his or her contribution to the local or global community. Like Karl Marx explained in his manifesto, contributing, earning or producing something of value is what makes us human. However, as logical as this statement may seem at surface level, diving deeper into its meaning, a vast territory of potentially unethical pitfalls will reveal themselves. In its purest form, this ideology can be used to discriminate against those who cannot work. Like a capitalist CAPTCHA test, people with psychological or physical illnesses, traumas or inabilities get filtered out. If working is our species’, essence, then whoever does not participate cannot be counted as human. As far-fetched as this observation may sound, it is acted out every day, in every city, in every country – where the most fragile members of society can be found wandering the streets, only able to catch some sleep in dark corners where they do not interrupt those who are contributing. It is a reality where urban settlements disperse into the farmlands surrounding them, a gradient of wealth emitting from the cities’ center points, fading towards the peripherals, forcing those who earn the least to travel the furthest to participate in this collective organism called human society.

In the winter of 2019, the global population was yet again made aware of the massive gaps that had been carved for centuries between people. When the world went into lockdown, it was quickly revealed that the innate level of humanity displayed in a functioning society could evaporate just as quickly as germicidal liquids. While ancient settlements relied on strength in numbers and a united front, the virus of early 2020 divided the people of Earth more than ever before. Confined to their homes, hatred, frustration, panic, jealousy and anger were fueled through global news. The pandemic had not only made it clear that many leading political systems were malfunctioning, it was also displaying the uneven dispersion of wealth on a global scale – with death rates and anti-mask protests as evidence. Taking a step back to get an overview, a string of signs, messages and warnings that has not been acted upon can be traced back throughout history. For decades, Tellus has been begging us to stop our materialistic mudlark for happiness. Building up, these rapidly escalating foreshadowing have now gained speed and ricoched

Homeless people sleep in a temporary parking lot shelter at Cashman Center, with spaces marked for social distancing to help slow the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Las Vegas, Nevada, US. Marcus, S. March 30, 2020.

TPX Images of the Day, [Online]. [Accessed 20/04/19] Available at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/ health/las-vegas-marking-parkingplaces-for-homeless-encampment

back to their causation – humans. The Anthropocene epoch has so far done little to convince anyone that humans meddling with nature can do good. With man’s curiosity now entering orbit into the abyss of space, it begs the question, what will be left behind? Once the capitalistic value of land transfers to another planet, what will be left on this one? Perhaps the question ought to be, who will be left? No longer bound to worship the ground they live on, praying to Gaia for another prosperous year, humans have reached a point in history where they for the first time are able to edit their own evolution, molding the planet that once molded them. As described in Yuval Noah Harari’s Homo Deus , humanity has, in a medical sense, reached apotheosis – divinity (or such was the truth before the virus hit). In the 1960’s, Gerard O’Neill asked whether the surface of a planet was the right place for an expanding technological civilization.

(Shcarmen, 2019, p 15) Questioning this train of thought through the smogged-up glasses of today’s society, a little shuffle of words makes for a more

interesting interrogation. Is the expanding technological civilization right for the surface of the planet? Judging by the exploitations reaching the news today – the short answer would be no. With survival of the fittest on the agenda, both the world’s richest ecosystems and the most fragile members of human society have become victims of man’s definition of value. While rainforests are being replaced hectare by hectare with palm oil plantations, eradicating hundreds of plant and animal species on an annual basis, skyscrapers are forming continuously expanding concrete jungles, pushing the homeless part of society to patches of land from which no further value can be extracted.

With space as the new frontier, the recovery of Tellus seems to have left the minds of the masses. Once a divine being, now deprived of all her personal attributes, her last remaining idiosyncrasies are awaiting superimposed human values. With capitalism as the new religion and shopping malls its cathedrals, money is believed to be the new cause of happiness. As written by Marc Auge in 1995, “We could start by saying – again somewhat paradoxically – that the excess of space is correlative with the shrinking of the planet: with the distancing from ourselves embodied in the feats of our astronauts and the endless circling of our satellites.” Today, people conglomerate towards epicenters of high materialistic profitability – the life of the regular farmer is no longer deemed as attractive as its urban counterpart – the hinterland yields to motorways killing off ecosystems in favour of our egosystems. It is inherently clear from the crisis we’re facing today that wastelands are not only physical manifestations of human decisions forced upon the surface of the Earth, they are also deeply engraved into people’s “species-essence,” as Marx would put it. The collective consciousness has evolved over time to become emotionally arid, synapses reacting to transactions not interactions. As in a real-life enactment of a BlackMirrorstoryline, people’s capitalistic values have become their defining feature, placing highincome individuals on the top floors of skyscrapers, and leaving low-income specimens to beg outside their entrance doors.

Bibliography / References

Adams, D. TheHitchhiker’sGuidetotheGalaxy New York: Harmony Books, 1979.

Auge, M. Non-Places:IntroductiontoanAnthropologyof Supermodernity . New York: Verso, 1995. pp. 103-104

Bratton, B. (2019). “Space is the Place.” Lecture 01, Sci-Arc. (online)

Di Palma, V. Wasteland:AHistory . New Haven/ London: Yale University Press, 2014.

Fuller, R.B. IdeasandIntegrities . Zürich: Lars Muller Publishers, 1963. pp. 165-193

Harari, Y. N. Homo Deus. London: Harvill Secker, 2015. Harvard University. “Gaia Hypothesis.” Accessed June 2, 2020. https://courses.seas.harvard.edu/climate/eli/Courses/EPS281r/ Sources/Gaia/Gaia-hypothesis-wikipedia.pdf

Latour, B. DowntoEarth . Translated by Porter, C. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017.

Sagan, C. “Carl Sagan’s 1994 ‘Lost’ Lecture: The Age of Exploration.”Accessed May 26, 2020 - https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=6_-jtyhAVTc&t=3785s

Wikipedia. “Gaia.” Accessed June 2, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Gaia

Wikipedia. “Tellus of Athens.” Accessed June 2, 2020. https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tellus_of_Athens

Philosophy Overdose. “Marx on Alienation.” Accessed June 2, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yIg-THMBzsU

In many of the conversations and projects that make up this issue of Abstrakt , a running theme of speculative futures can be found, with specific notations towards ecology and living in a multispecies environment, along with new paradigms that superimpose nonanthropogenic environments and our obsession with new and progressive technologies in the hopes of creating a better, more cohesive world and built environment for us all. It is becoming more apparent that our awareness and attention to design could facilitate this, a better equilibrium between humans and the Earth’s other inhabitants and natural resources, and has therefore been explored via conversations that can bring attention to this and instigate inspiration to begin to formulate a society that can and wants to cope with drastic change. To encourage thought and internal discussion, we looked to Werner Sobek for his creativity and hopeful resilience. His positive outlook allows a glimpse of hope into how we can afford to imagine a positive future. Throughout his work, publications and interviews, he makes clear that change is a mindset, and we can start to change ours now. The first step is to transform our ways of living, reduce our consumption, and optimize our excessive demand for resources. It is on us to use our skills and ingenuity, build beautiful architecture with resource-friendly techniques, spread knowledge, and put pressure on the policy agenda of the construction industry.

sources: Werner Sobek. Zumtobel Group, 2019/20

Turning away from fossil fuels has to happen gradually. Therefore, we need to put restrictions and limitations in place. We need to consider how many roads, how much living space, how much energy, how many car rides and flight journeys are appropriate per person. Giving people an unlimited availability of energy and resources is fatal and naturally leads to overconsumption.

The world’s growing population, combined with rising levels of wealth in many developing regions, has continued the exponential demand for quality and more durable forms of infrastructure. The construction industry currently accounts for around 60% of global resource consumption. To compensate for this, we have to think of ways to create more living space while minimizing the use of the heavily carbon-intensive materials that are typically being used. In order to do this, we need to rethink our building practices to allow for the reuse of all materials, along with developing new ways of constructing and building with innovative materials.

Reducing the amount of concrete in the construction industry is vital towards creating a future for the planet as we know it. Yet due to the lack of alternatives, it is nearly impossible to cut it out completely. Because of its static properties, low price, availability and flexibility, as well as its superior fire and sound insulation qualities, it is set apart from all other building materials.

Wood, on the other hand, is seen as the most sustainable building material on the market. It is renewable, it stores carbon, and it is generally less energy-intensive to process compared to other construction materials, including concrete and steel. Used in lightweight constructions, it can be more cost-effective due to its ability to be used in a relatively quick construction method, as well as being light and easy to transport. Natural materials such as wood also have a great emotional and psychological benefit and contribute to our health and well-being.

Despite its apparent ecological advantages, wood cannot be considered a solution to the problem. Not only is there not enough timber available, more importantly, taking too much wood out of the forests would disturb the overall ecologic cycle. Newly planted seedlings bind far less CO2 than their just-felled predecessors.

But there are other ways of optimizing the usage of materials and implementing them in a more skillful way. The design process of each building needs to be carefully planned, alternative materials such as clay and natural stone need to be explored, local resources and transport routes need to be taken advantage of, and more trees need to be planted. Forestation is one of the most important investments for our future.

Good design can be an important part of a sustainability strategy, since aesthetics are essential to people’s perceptions of their homes. When people love the spaces they spend time in, they tend to take good care of them and maintain them better. In the end, the most sustainable building is the one that stands the longest.

The only way to radically reduce energy consumption and emissions in the construction sector is to completely transform the way we build. Resource-friendly building will require the consistent use of lightweight construction materials, recycling-friendly techniques, and the application of secondary raw materials such as recycled aggregates in order to avoid creating “tomorrow’s hazardous waste.” We have to look at the emissions that arise during the manufacture, transportation, operation, conversion and dismantling of buildings. Furthermore, carefully remodeling and giving new purpose to already existing buildings will become more and more imperative.

Prof. Werner Sobek is an internationally renowned architect and civil engineer, and considered a pioneer on lightweight, sustainable and resource-saving construction. Since 1992, his own practice has extended to 16 offices around the world with over 400 employers. Between 1994 and 2020, he was head of the Institute for Lightweight Structures and Conceptual Design (ILEK) at the University of Stuttgart. He is cofounder of the German Sustainable Building Council (DGNB) and founder and chairman of the renowned Initiative for the Promotion of Architecture, Engineering and Design (aed). He has published multiple books, including his latest book, Nonnobis–überdas BaueninderZukunftBand1(Avedition 2022), and has received numerous awards and honors.

Elisa Iturbe and Stanley Cho together run Outside Development, an independent firm that bases its work, on research and questioning the premise of what architecture is, to engage with how it can and should be at the forefront of social constructs and urban communities. Their work largely revolves around design consultation for futureoriented urban realms that seek to question and resolve land ownership models, governmental strategies, and a push towards new energy paradigms.

Elisa, in your introductory article for Log magazine, “Overcoming Carbon Form,” you point out the incapacity of architecture to make a difference in addressing the current climate crisis, and also the futility of a compartmentalized and purely technical response to a cultural problem. How do you see the role of architects both in proposing and also realizing new scenarios of human coexistence?

Elisa Iturbe: I’m glad you ask this because I think it gives me a chance to clarify.

I don’t believe that architecture has an inherent incapacity to address the climate crisis, I think that architecture has an extraordinary amount of power. But the power of architecture is not always for good, and in any case, power is not inherently good or bad. It simply is an asymmetry. The problem is that architecture has been used to reify and support an industrial system and to create a spatial paradigm that we now don’t know how to get out of. In fact, architecture has been at the center of the climate crisis since the beginning, because it produced a spatial paradigm for a mode of production that is based on dense and abundant energy. We created all of this built form, and we shaped all of our lives and created a certain subjectivity and a mode of life such that we don’t know how to change in many ways, because it got written into space, in concrete, brick and mortar, etc.

But in that sense, I feel like architecture is one of the most important disciplines. And this is in contrast to the discourse that architecture has no agency, and it all has to come from policy. But that is because we have compartmentalized architecture so severely, and so we don’t see the agency of architecture when we think about practice as it is, especially in the US context, where we are so constrained to economies of development, that there are basically no ways to work outside of the desires of the developer. And so in that context, of course architecture has no agency, and with no context, architecture is just decoration

for capitalism. But, I don’t think it inherently has to be that, I don’t think that the boundaries of the profession are the boundaries of the discipline. I think we have to understand that in order to propose something different, we can propose new ways of life through architecture. That’s something that we’ve done before, sometimes for better and sometimes for worse.

Do you consider such a necessity for a new social form to be independent of the present energy paradigm? Also, besides our relationship to resources, do you believe it is important to rethink the relationship between humans and other living beings?

EI: I don’t know if we can really separate our social form from our energy paradigm. I think that the way that we draw energy from the environment is inseparable from how we think about our modes of production, and that drives our social forms. All of these things are related to each other. Of course, we have to think about our relationship to other living beings because ultimately, everything that we make and everything that we use and everything that we eat, all of it comes from the ecosystems that support human life. I really liked the work of Jason Moore and Raj Patel, and they use the term “web of life” to talk about capitalism existing within that web of life. They recognize that we pretend like our human systems exist apart from this thing we call ‘Nature,’ but actually nothing is outside of nature, all of it is fully implicated. And we pretend as though it’s separate, but it’s really not. We often like to pretend that there

“Architecture has been at the centre of the climate crisis since the beginning, because it produced a spatial paradigm for a mode of production that is based on dense and abundant energy.“

are things like labor and wealth that we can calculate outside of all of the larger flows of energy and materials but really, the general economy (as defined by Georges Bataille) is the recognition that energy is flowing into the earth from the sun, and everything that moves on the surface of the Earth is related to that. There are all of these things that are so much bigger than the human systems that we create, and the human systems we create are inevitably always inside of this.

So I don’t know if we really have the option to not think about other living beings. If anything, we’re building on the legacy of having pretended as though they were separate and now we see where we are, right? Climate change is a symptom that shows just how wrong that is. The more that we pretend that they’re not related, the more extreme the relationship becomes. I think it’s just inevitable that we have to see them as connected.

Within your practice, Outside Development, you research a lot about carbon form, carbon modernity, and social methods of perhaps solutions for reducing this trend within architecture. How do you see a relationship between natural ecologies and materials, in an attempt to create a new, non-carbon-intensive paradigm?

Stanley Cho: We need to be smart about the resources we use and current practice. But I think what Elisa was getting at is, we are trying to understand what got us to this place. How did we arrive here in the first place? A lot of it has to do with social relationships and the habits that we’ve created under a capitalist regime. A lot of architects will talk about making skyscrapers out of cross-laminated timber. We want to ask, Why are we even making skyscrapers? We are trying to understand more of the core issue of how we arrived in this kind of wasteful economy.

Of course, we have to be realistic too and understand

that this economy does exist. And instead of using carbon-intensive materials, we need to look for more natural ones to build with, or ways that are obviously less extractive and destructive.

What would you see as an alternative definition or alternative notion of ‘sustainability’ that moves away from such an overused term and strategy and focuses on the deeper issue at hand?

EI: I think it probably doesn’t boil down to one term. But the project of carbon form has led us to thinking about the concept of energy transition and how we achieve an energy transition. For me, this is a more important question than Can we create something sustainable?, because the word ‘sustainable’ is too elusive. What really needs to happen is an energy transition. If we look at the history of energy transition, it’s not a fuel transition. An energy transition is a fundamental transformation in our relationship to energy. There have only been two energy transitions: when we moved from being a hunter-gatherer society to an agrarian society, and then from an agrarian to industrial society. These were profound changes in modes of production and social structure. Both of them also brought about revolutions in built form and in space. So if there’s going to be another energy transition, it’s not going to be just that we figured out a way to make a lot of solar panels, it’s going to be about fundamentally questioning our relationship to energy. Right now, the assumption is always that we just have unlimited amounts of it, but that was never the case before fossil fuels. That is something that is

“A lot of architects will talk about making skyscrapers out of crosslaminated timber. We want to ask, Why are we even making skyscrapers?”

very much part of the carbon imaginary. This energy is coming from outside of time, essentially, it’s coming from millions of years ago, it’s coming from outside of the biosphere, it’s coming from underground and not from the forest or the field, it kind of creates this illusion of infinity. We absorb that ideologically, and it becomes reflected in our economies, in our cities, in our patterns of consumption. So the question, Can we be sustainable? is a surface question, because it depends on what you’re sustaining. I think a lot of people think about it as, How do we sustain capitalism? How do we sustain our current patterns of modernization?

We’re just interested in asking a different question. If we’re going to address it at its root, then there needs to be a different kind of transition, where it can’t just be a fuel transition, it has to be an energy transition. And an energy transition means that everything changes: social relations change, modes of production change, our way of life changes, our relationship to land changes, the distribution where things are produced changes. This is ultimately a change in urban form and in settlement patterns.

In response, I think that architects have to play a very important role. But again, it’s not just about looking at the existing built environment and our existing ideas about the city and asking ourselves, How do we make this more sustainable? It’s about saying, Can we have a new concept for the city in the first place? We need to generate new ideas for how settlement patterns even work, and what it takes to sustain a human life and what it takes to sustain human communities and to preserve biodiversity and to respect that web of life that brings everything into existence. And so we have to reinvent it all. That’s why I think sustainability is insufficient.

SC: Just adding to that, greenwashing is a superficial kind of thing that obfuscates us looking at the question of form. In a way, it’s like a decorated shed,

it’s not allowing us as architects to question and to stand a critique of form, which, of course has to do with all those things that Elisa just talked about, the social relationships, the modes of production, etc.