PERRY KULPER

10 perry кulper Interview

Perry Kulper, portrait ©Perry Kulper

It is apparent that in your work, the choice of medium has an impact on the outcome of the design process. Could you elaborate on the aspects you focus on when you articulate a project through a drawing, and in particular, following your drawing methodology, as opposed to other processes and media you have worked in?

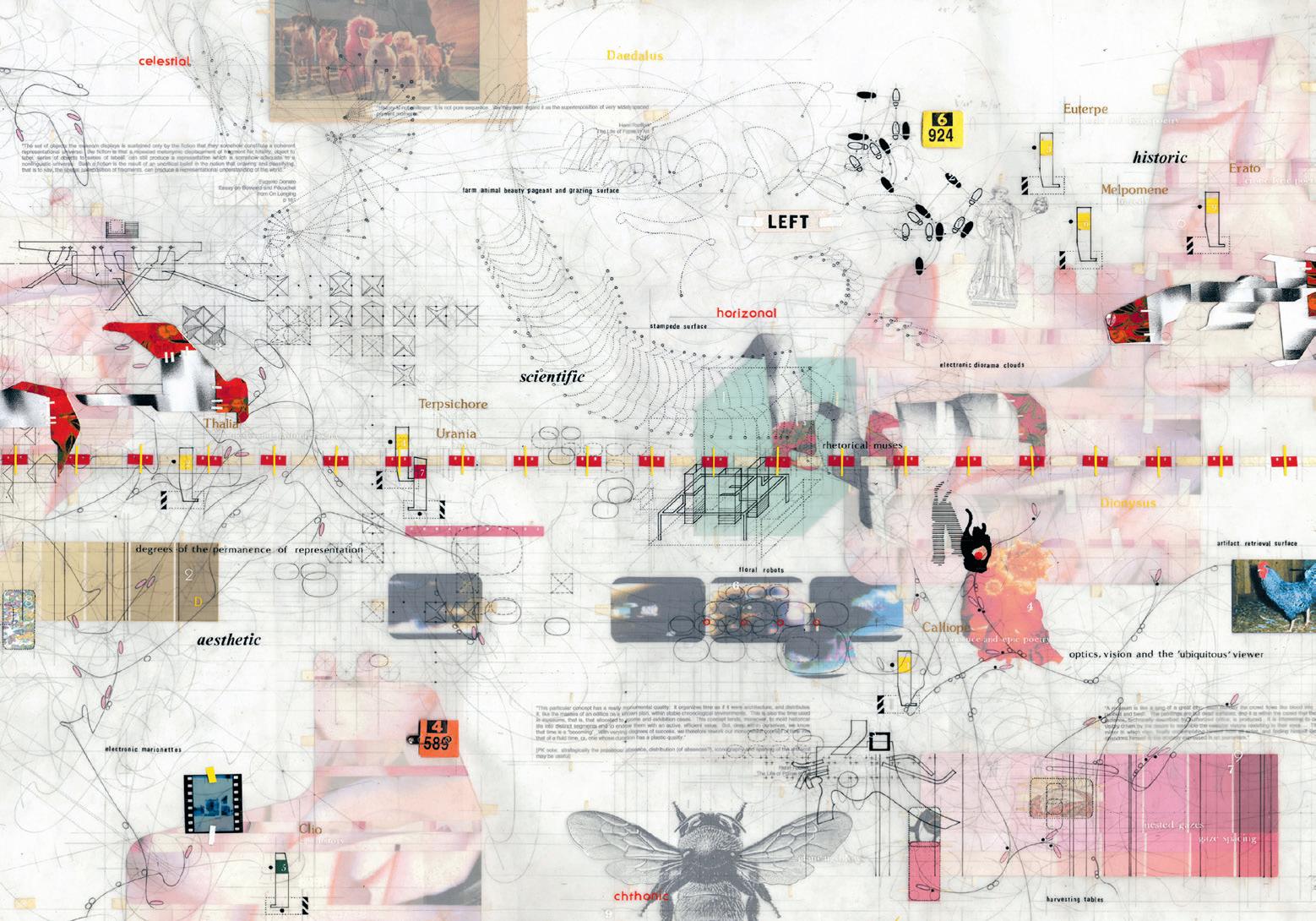

I’m interested in form(ational) specificity. This has to do with developing formations that are specifically structured to enable interactions with their communicative potential. I don’t tend to talk about meaning or content. I use the term ‘communicative potential,’ meaning there are varying degrees of spatial, or representational, legibility for different kinds of audiences in a project.

I care about form specificity. I’m not so interested in schematic, or generalized, formations, unless they are part of the intent of a project. A commitment to form specificity doesn’t have to do with detailing, it has more to do with formations – representationally, materially, and spatially – that structure particular relations – what I refer to as relational assemblies, or relational contours, in which we can participate with those relational dynamics and grasp certain kinds of communicative potential. How we perceive, how we experience things.

I’m also committed to producing drawings that are phase-specific – particular to the phase of the work I’m involved with at the time. If, for example, I’m interested in phasing and duration, and speeds of exchange within a landscape, then I’ll lean towards techniques and methods like notation, diagramming, or analog thinking that are specific to those interests. I think about which design methods are appropriate to work with on those phase-specific issues, topics and formations. I try to develop representational techniques that allow me to generate thinking and work relative to what I’m working on then.

I’m also interested in different speeds of working and teaching about that, because these afford different kinds of insights, intelligences, and latent knowledge

constructions. Largely what I try to do is augment schematic design and challenge the authority of the picture plane. I try to deal with what I call the ‘crisis of reduction,’ that is, reducing things too quickly when working. To me, my work is very much the same. So, the methods and representation techniques I work with partially have to do with not doing things the same way that I always do them. Many can have interesting, and even relevant, ideas. For me as an architect, as a teacher, it’s just as important to establish a discipline for working on things as what the content I’m working on is. It’s one of the key things that matters to me – how students and I work.

Many can have interesting, and even relevant ideas. For me as an architect, as a teacher, it’s just as important to establish a discipline for working on things as what the content I’m working on is.

You use different systems of notation, geometries, techniques or languages that come together in a single artifact. How do you construct your working process around this? How do you structure your ideas and thoughts in order to achieve clarity on the relations between things and introduce hierarchies among them?

There are two parts to the answer. The first is that I normally work early on on yellow legal pads. There I keep track of many ideas, interests and references and I go back to them and prioritize things – these are the primary interests, these are secondary and tertiary things. I also think about representations and spatial conditions in that way – there are primary, secondary and tertiary structuring conditions. I prioritize things that matter, and ideas I’m interested in, when I work relationally – the kinds, or types, of relationships that are established; their strength or weight; and their

11

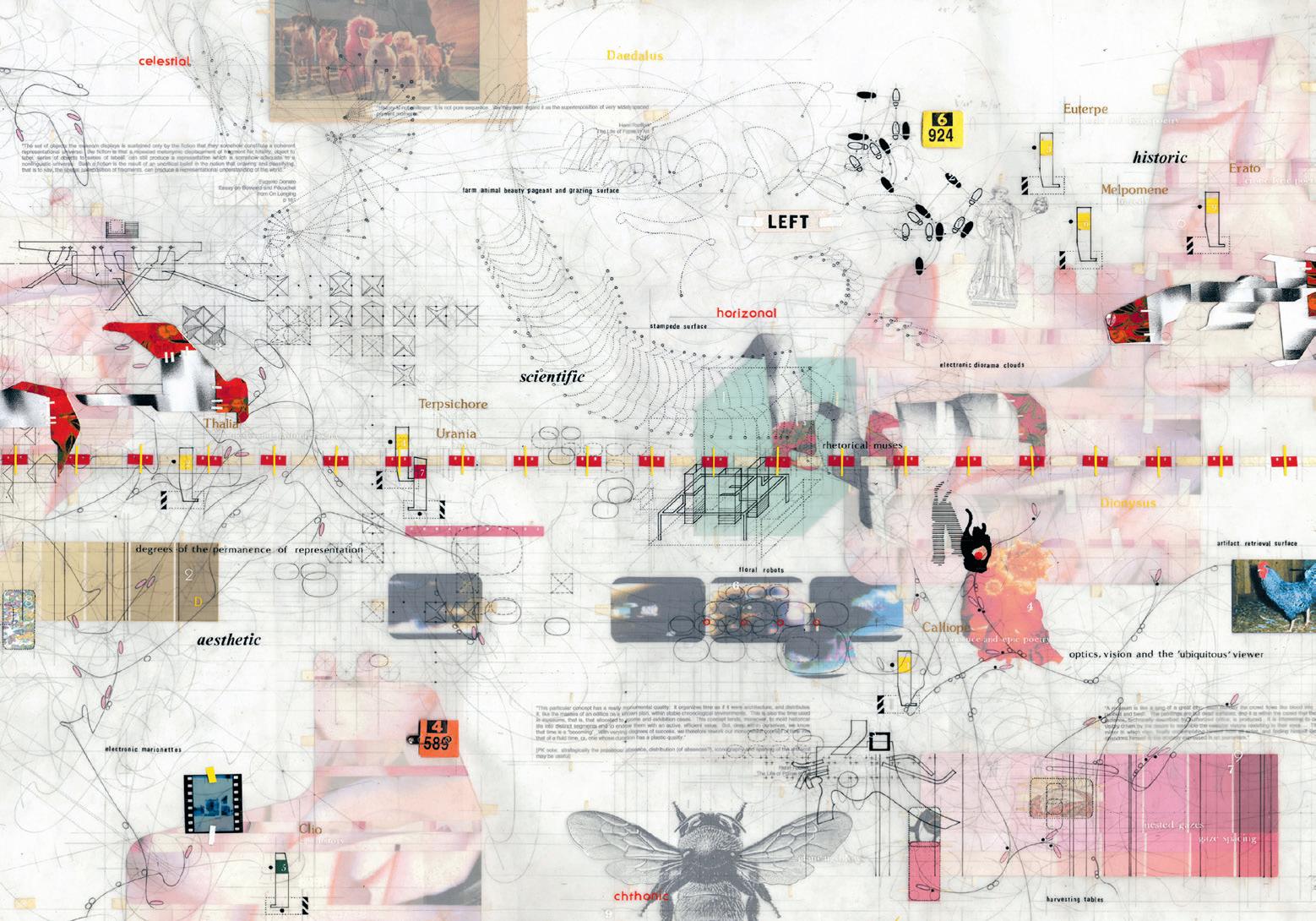

©Perry

or in local assemblies, because they each have their own fidelity, integrity and significance. For example, that diagram is made to work on these things, and those figurative pieces work in relationship to that map. How to listen collectively to the conversations which emerge when using different languages of representation – that’s the challenge. To be a deeper reader, I think of myself as something like a detective – the drawings are clues, kinds of fields of evidence, and I need to figure out what kinds of metaphorical crimes are being, or might be, committed there. perry

durational and temporal structure. For example, something might exist in a spatial condition for ten seconds, sacrificing itself to set up other relationships that are meant to communicate in particular ways. I care a lot about those relational dynamics. The other part is much harder – particularly when I use language, diagrams, and figurative pieces simultaneously in a drawing. The reason I use varied representational languages is to keep things in play as well as I know them at that moment. But it is then difficult to work out what those different families of representation are talking about, let’s say collectively,

12

кulper Interview (1)

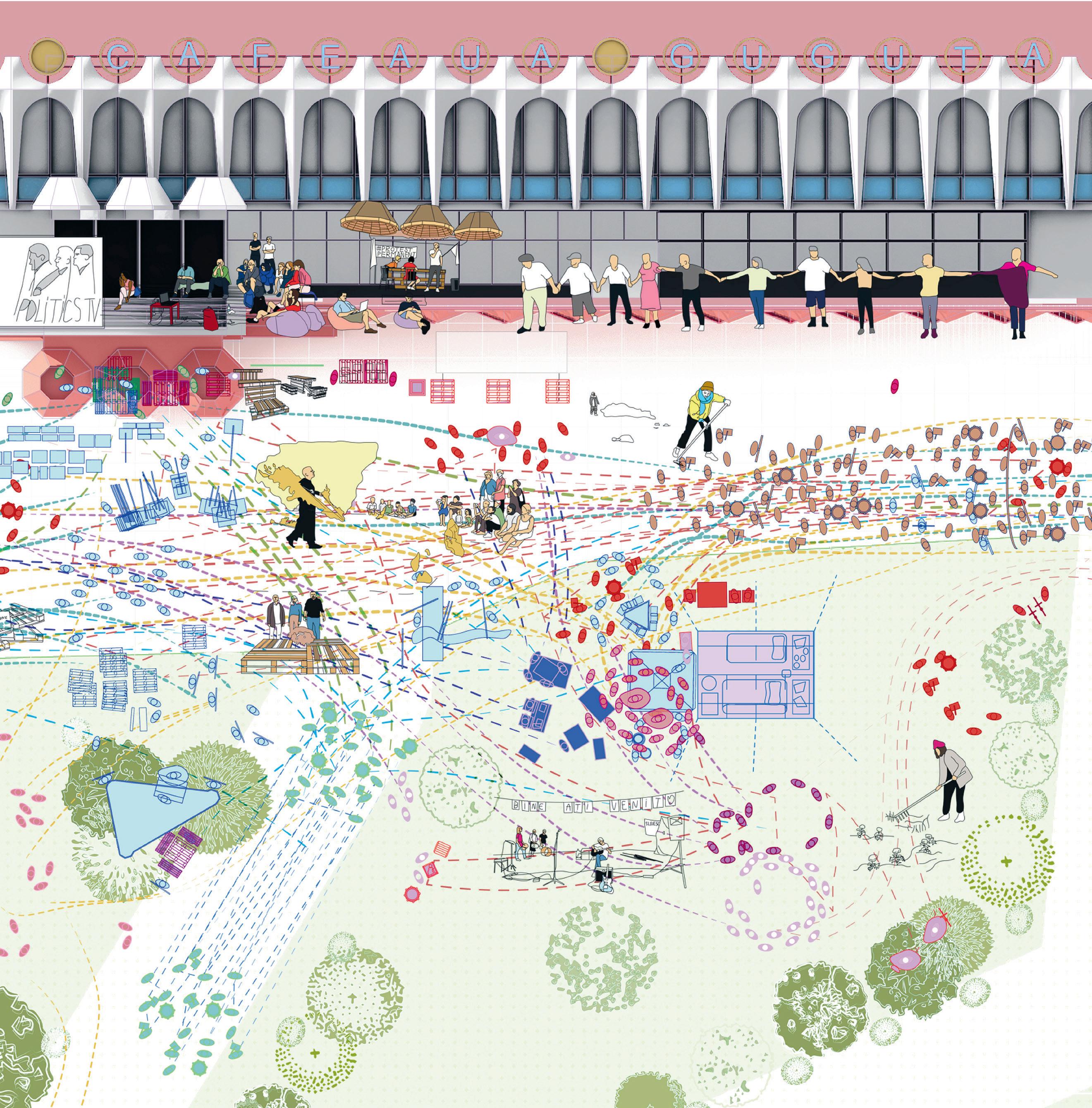

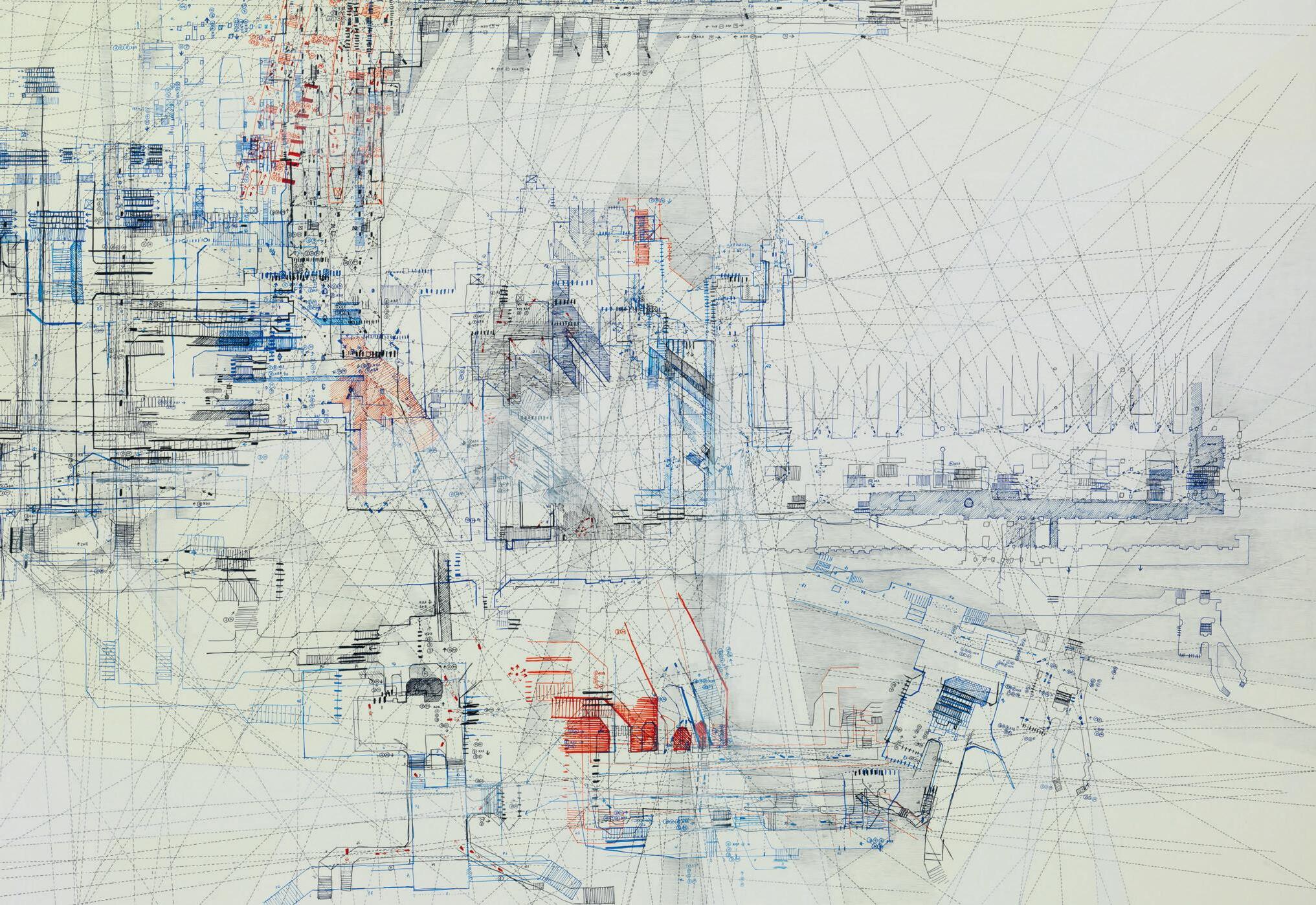

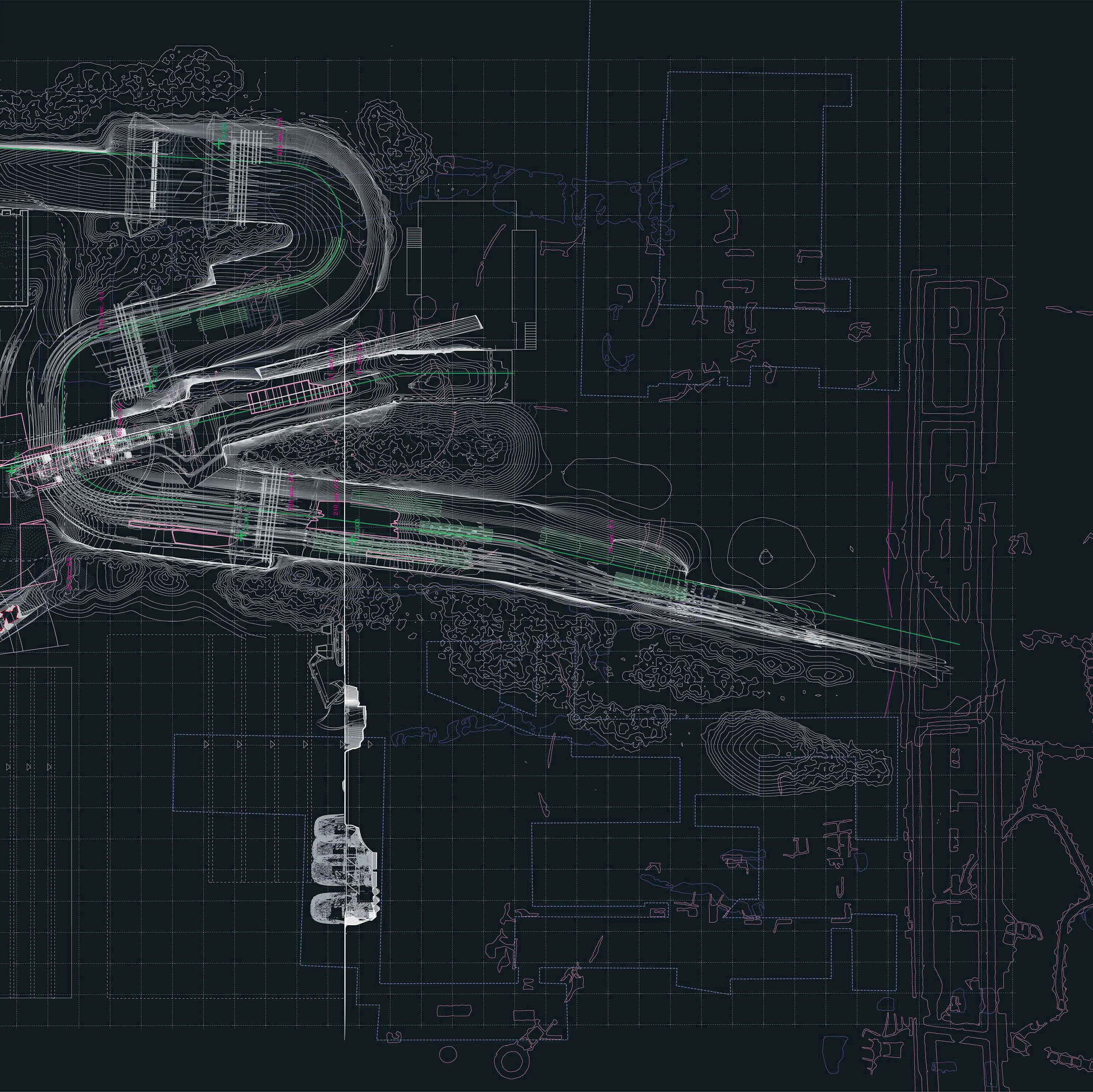

Central California History Museum, Thematic Drawing, 2001

Kulper (1)

How to listen collectively to the conversations which emerge when using different languages of representation –that’s the challenge.

I have a lot of things that interest me. The question that you’re asking is important because in the layered drawings, there are no brakes. I can go forever. I could have a hundred ideas in a drawing. Curating, managing hierarchies, prioritizing how to read things, and then translating them spatially – that’s the discipline. That’s my work.

In your articulation of projects, you tend to reject the classical approaches, such as labeling programs or traditional formats of representation, such as plans and sections. What do you gain from the freedom of rejecting the established vocabulary?

To be simple, what I talk about is the naming problem. Historically, we name things so that we can share knowledge, have common understanding. But in my world, naming and structuring are different. Let’s say we asked someone to design a house. They might design an interesting house that would likely have bedrooms, bathrooms, a kitchen, maybe a garage, and a place for the dog to sleep. No problem.

But the difference between starting with a program, or even the program of drawing a plan, a section or a perspective, is that those are destinations already predetermined by history, precedents, conventions – bedrooms, bathrooms, kitchens, living spaces, and family rooms, let’s say. But if I ask you rather to work on dreaming, the privatization of sexuality, nocturnal and diurnal cycles, and illness, there might not be a bed with nice windows and materials as we know them. There might not necessarily be those elements because to structure and engage with celestial movements, the nocturnal and dream states, horizontality, sexuality – to work on those issues is, for me, a different discussion than to work on a bedroom.

I don’t have anything against architectural programs. But I think we need to be careful with them, because of what they predict, or we might simply repeat what is known, expected. The example I like to use is if I ask you to design a foyer: you come into a building, it’s two storeys high. There’s an information desk over there, some potted plants nearby, and a bank of elevators on the other side. There’s probably a set of glass doors that you came through, and there’s an exit stair behind the elevator. That can be an amazing spatial setup, but in my world, that may not be working on what might be structured relative to entering a spatial world.

Another example: I’m holding a wooden pencil in my hand. It is a Ticonderoga No. 2. In my world, depending on its situational conditions, it belongs to relations connected to deforestation, the history of writing, mass production, the erasure as a form of censorship, the gestural structure of the body, and so on. Its name is a Ticonderoga No. 2 pencil. When thinking through relational structuring, the pencil belongs to a whole network of relations that are more or less graspable. You would say, what are you talking about? Deforestation? The wood that makes the pencil might have come from the Amazon rainforest, for example. It also belongs, relationally, to labor forces, cultural practices, and legal protocols, and to many other relational assemblies. That is the simple answer to the question. It is the naming problem for me. That’s how I refer to it. I’m interested in

[T]he difference between starting with a program [...] is that those are destinations already predetermined by history, precedents, conventions. [...] But if I ask you rather to work on dreaming, the privatization of sexuality, nocturnal and diurnal cycles, and illness, there might not be a bed with nice windows and materials as we know them.

13

structuring, rather than naming, to augment things, to avoid the crisis of reduction.

When you’re asked to make a plan, a perspective, or a digital model, in my world, you have to know a lot at the same time to make relational decisions. That’s why I’m interested in multiple languages of representation, critical fragments, and the way digital workspaces get set up. It’s often difficult to get everything up to the same speed at the same time. The same thing is true when it comes to drawings. When I don’t know how to get an idea into form or a drawing, I need to look at structuring and the techniques by which I work. I use a lot of section[ish], plan[ish] visualizations, but 40% of the plan might not be there and 20% of the drawing might not be a plan.

In your project, “Aerial Diptych Follies,” you transition from physical drawings to digital drawings – from drawings constructed of points-lines-surfaces into drawings composed of three-dimensional objects, occlusions, reflections, and the absence of lines. We are curious: when did you start including different digital processes in your drawings, why did the digital interest you initially and what did it offer to you?

This is my biggest challenge now. I don’t have digital modeling skills, but there are people that I’ve been fortunate to work with – eight, nine of them – over the last several years. I think of them as collaborators. My biggest problem right now is that the way I work and think through, say, the layered drawings, yellow pads and so on – those aspects are incredibly difficult to transcribe to someone. So how to communicate

The digital world is phenomenally interesting. I think we’re touching 3, 4, 5% of what digitality can allow conceptually and spatially. It’s incredibly powerful and has deep potential.

with them what I’m thinking about, and then to develop techniques to work on that in collaboration, is challenging.

Essentially, what we do is digital modeling because it’s the most immediate, expedient way – with the limited amount of time we have – to get projects like the Aerial Diptych Follies in play, and the work accomplished.

So, for example, the bird motels – those are direct, analogic thinking, this should be organized like a circus and these objects should be more like a bird alphabet crossed with a topiary garden. We’re modeling things. In the early days of me working – on manual drawings, let’s say – these projects might go through several phases, but in digital work, we’re modeling them quickly, directly.

And to be honest, they’re not ready to be things. They always turn out as things regardless of the temporal interests – for example, I might be interested in an object that has phase shifts and can move from an indexical phase, to a mathematical, and on to a material state, in different timeframes and in different places, or split geographies. It’s hard to work on those kinds of interests in digital modeling, so there’s often a real reduction in the work.

(2)

14

кulper Interview

perry

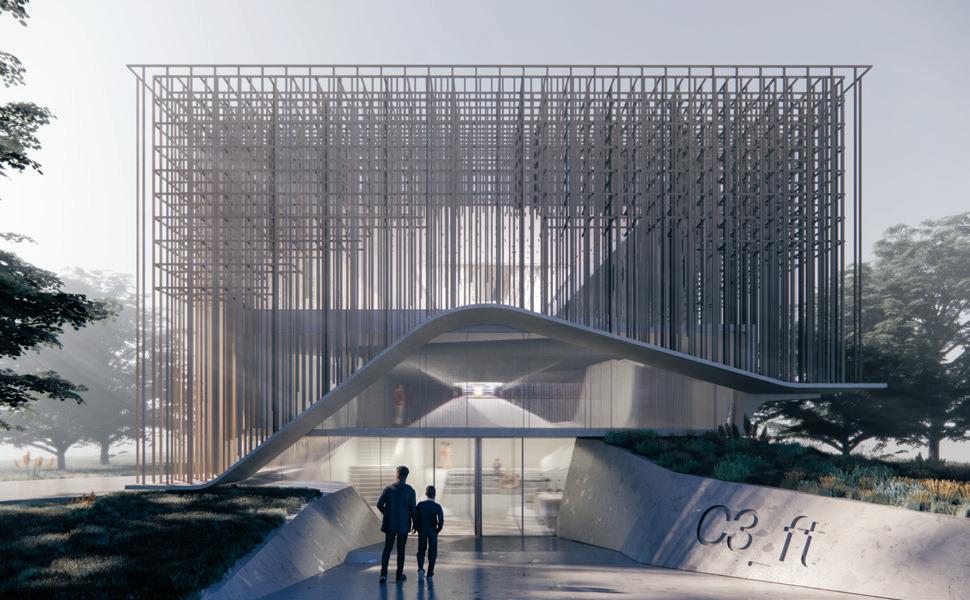

Aerial Diptych Folly, v.01, Frontal, w/ Oliver Popadich, 2018 ©Perry Kulper (3)

Aerial Diptych Folly, v.01, Frontal, Wireframe, w/ Oliver Popadich, 2018 ©Perry Kulper

(2)

(2)

What have you observed in terms of representational complexity and reduction of information when using different media? What further architectural elements are you able to communicate with different media in an effort to expand the content of a classical architectural plan? perry

There are huge differences between the physicality of working on a drawing like the David’s Island Strategic Plot. That’s a 125-hour drawing – technically, not to do with the thinking. There are six layers in it. There are animal x-rays, aluminum foil and cut paper pieces, drawn things, press-type letters that go on one letter at a time, and so on. The latent and tacit knowledge, which is gained by that means of working, can contribute significantly in relation to keyboard commands. But the keyboard has huge potential. The digital world is phenomenally interesting. I think we’re touching 3, 4, 5% of what digitality can allow

conceptually and spatially. It’s incredibly powerful and has deep potential. I’m not against digital modeling – AR, VR and XR – at all. But I don’t have the skills to work through certain kinds of interests through those mediums.

That’s why I’m trying to work on composite and hybrid visualizations and working techniques. I am going to try to work on some physical constructs now that might have filmic techniques, diagrammatic and figurative things, happening simultaneously. I’m still trying to work on how to work.

Ideally, I’d like to have a think tank that would likely take about a million euros, with a half a dozen people, with deep curiosities, and a lot of gear to work on questions like you’re asking me. That’s what I would like to do.

It’s interesting to know that you think the reduction of information is actually due to more of a lack of time, lack of knowledge of using a certain medium, and issues in communication and collaboration, rather than the limitation of the digital itself. So the medium still has a lot of potential.

I think that the setup of a digital workspace is very interesting relative to what I think about. Not just producing things in Rhino, Blender and Maya, but how to set that workspace up, what kind of information is there, wondering what kind of potential it might have. That whole space, and the operations to construct it, is more like my drawing workspace. I don’t know how many people set that space up, as a rich condition, as a kind of digital construction site. Everything about that workspace is very interesting to me.

16

кulper Interview (3)

I use things that I call ‘language folds.’ I imagine in a conventional plan, it would be hard for me to think about a spatial condition that splices information from nine stock markets around the world, tracks four different timeframes – fictional, real and unimagined – and morphs into zero-ness in a split second. That’s hard for me to work on in a traditional plan. I often use things like language folds and analogous thinking to help create a bridge between what I’m thinking and what I might do. For example, according to some intent, that ‘plan’ might be organized like the game of Go crossed with political policies from 17thcentury Florence.

Analogous thinking and language folds allow me to work on temporally structured things – that might have to do with phase shifting, wondering if a spatial condition could move into a mathematical state and then trigger nine other material states in other parts of the world. What’s harder to do is to learn how to work on those things amongst many other ones that interest me: phase shifts, durations, different geographies, mathematical, physical, indexical states, material emergence, and cross-breeding with machinic logics, for example. I’m interested in opening the conceptions of architecture as part of what I do, and I’m interested in developing my imagination. When I was your age, I didn’t have an imagination. Now, I’m trying to find ways to navigate the world and to contribute in some small way, trying to open things up conceptually. I use multiple languages, analogous thinking, lots of other things when trying to invent ways in which I can think about the world and engage people.

For our annual publication of ABSTRAKT, there are always two issues with two topics that could potentially have a dialogue. While the fifth issue is focused around the artifact as a snapshot of architectural design processes, the sixth issue looks into time-based media and the opportunities presented by the dimension of duration. We are fascinated by the fact that the aspect of time is so present in your

drawings. Why is the temporal dimension important to you and how do you approach it in your work?

This, I think, is one of the critical questions of your generation. My generation is represented by brick stackers, stone layers, steel erectors. In your lifetime, there’s no question – architectures will get up and walk around sites, they’ll change their material states, programmatic logics, they will negotiate social conditions, and so on. You see it in robotics, machine learning, AI.

[Temporality] is one of the critical questions of your generation. My generation is represented by brick stackers, stone layers, steel erectors. In your lifetime, [...] architectures will get up and walk around sites, they’ll change their material states, programmatic logics, they will negotiate social conditions, and so on. You see it in robotics, machine learning, AI.

For me, temporality is the largest organizational structure of the universe. Conditions of change are what structure what we know. Whatever we constitute, whatever our belief systems are, temporality is the key principle. It’s why we get up each day, because each day is going to change. It’s why we’re engaged in things, because change allows us to encounter things differently and to reframe our relations to the world.

Your generation, I think, can think representationally, spatially and materially, but also conceptually, about how temporal structuring might be framed and advanced. Your generation is going to be inundated with questions linked to temporality. I don’t use the

17

word “time” because it normally has to do with a sequence, a chronological unfolding. And for me, temporality is not structured that way. Temporality is very complex. For me, it has to do with, again, speeds and durations and phases and shifts of certain kinds. It has to do with reconstructing relational assemblies in particular kinds of ways.

The best I’ve done is to illustrate things to do with temporality. Sadly, I’ve not figured out how to work on it. When Eadweard Muybridge and others were developing early time-lapse photography, they were working on change, on temporal shifts. They were working in that space, they were not simply imaging it. This is one of the critical problems these days –imaging things. I don’t actually work on the subjects at hand. The best I do is make a picture, a diagram, or a notation as a kind of image of compressed times or elongated and spaced phases. That’s imaging it, not actually working in that space. That’s what I would like to try to get towards – to work on, and in, those areas rather than simply illustrating, imaging or picturing them.

So, this is where the think tank would be great. How do you work on an architecture that can shift its geometries and its material states and talk to three different timeframes in the world? How do you actually work on that rather than illustrate it? For

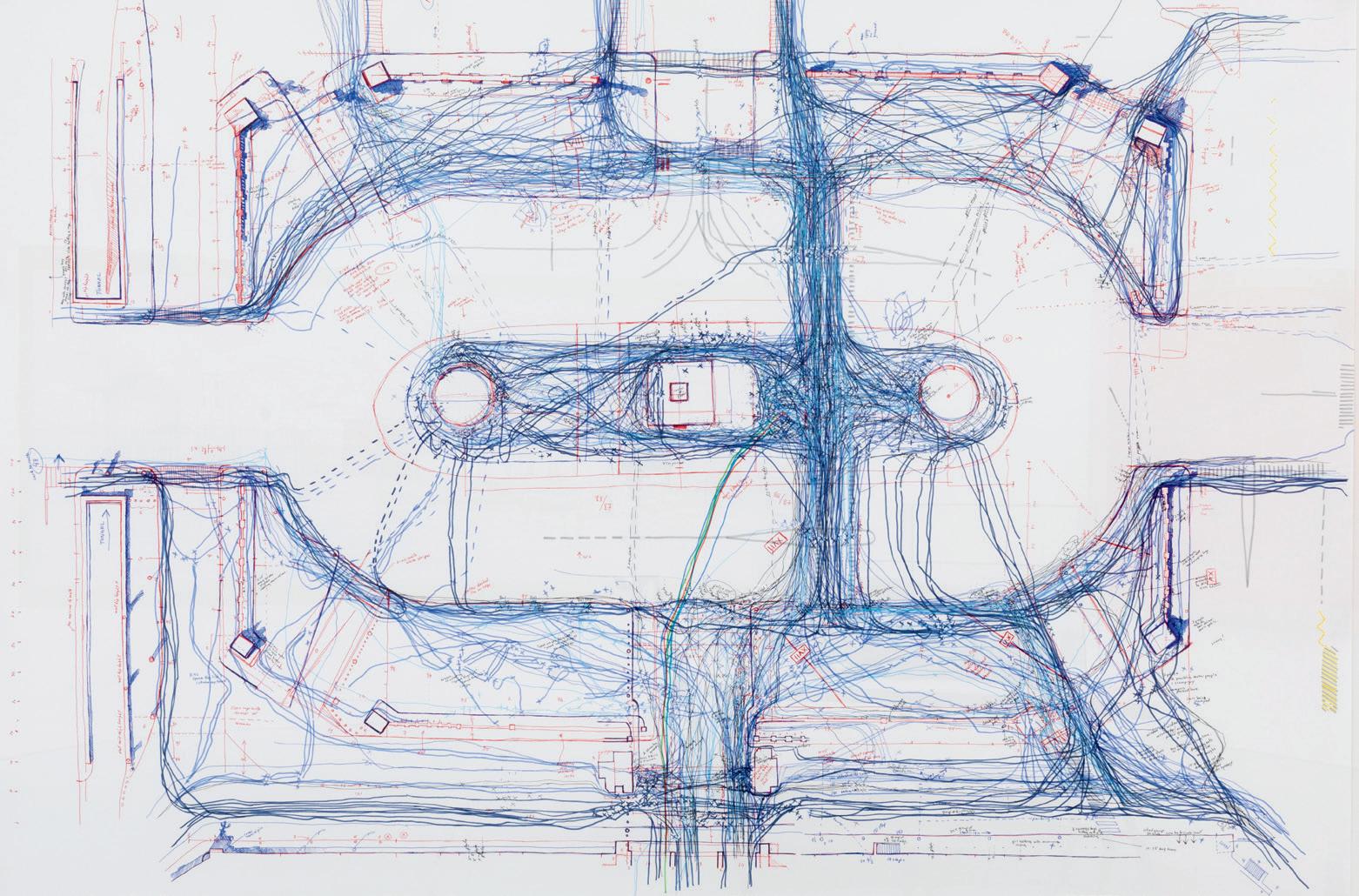

The David’s Island Strategic Plot points to the greatest range of temporal conditions. It has to do with the temporalities of vision – panoptic and panoramic vision. It has to do with the potential of the changes of seasons. It summons temporal conditions linked to nautical mythologies and navigational mapping, and it points to several distant and immediate temporal circumstances. The way materials behave temporally, for example, kelp harvesting in relation to polyp labs that are doing research, in relation to mythical sea travelers that might move through their landings. The drawing points to, or tries to attest to, the greatest range of speeds, cycles, and fictional, abstract and real temporalities. Those interests aren’t really worked on, but I tried to make visual notes about them. And in my thinking, I see those mythical sea travelers moving through the steel walls and kelp harvesting, and data feeds, and information logics. I see those moments as unusual temporalities that are being stretched, compressed, but not worked on in the Strategic Plot. They are simply diagrams, images, or a set of words to keep things in play. They would need several levels of translation and development – representationally, spatially and materially – to communicate appropriately. perry

The best I’ve done is to illustrate things to do with temporality. Sadly, I’ve not figured out how to work on it. When Eadweard Muybridge and others were developing early time-lapse photography, they were working on change, on temporal shifts. They were working in that space, they were not simply imaging it. [...] That’s what I would like to try to get towards.

me, illustrations are generally not insightful, because there’s seldom knowledge construction. There’s an image construction. I tend to image what I’ve basically known through techniques of representation. It’s not getting in the mud and working on the issues. I think, for your generation, it’s an incredibly interesting question and it’s one of the reasons I’m interested in the digital workspace. How do you cross-splice data feeds into a digital model in relation to historical events? How do you set that up so we can work on the kinds of conditions you’re pointing to? And that question, which I’ve tried to touch on, I can only imagine engaging with analogously. I can only know things through likenesses.

In your work, is there a particular drawing that is addressing longer time-span conditions?

18

кulper Interview

19

(2)

David’s Island Strategic Plot, 1996 ©Perry Kulper

(4)

Do you ever consider how a viewer would interact with your drawings, or are these solely an outcome of your process?

I think a lot about cultural perception. That is how, as human, and non-human species, we navigate a world. What are the things at stake when we negotiate worlds? Like you’re talking with me right now in a particular way. There are a lot of things that happen in terms of structuring and cultural expectations and perception to make our conversation possible. We’re social bodies and I take the body as complex – the body is a fleshy, chemical, biological body, and we’re also liminal bodies, we’re data sets, we’re a relational set of properties. We’re not simply things. I parked my car out in the parking lot today. When we co-construct the world, there are several key things that allow us to encounter it. Our senses: touch, smell, sight, hearing. That’s part of it. Our deep memories, our actionable memories, and our imaginations, are critical. In the situational conditions in which we find ourselves, those things conspire to allow me to go out and get in my car later today. I have to remember that I have a car. I must imagine that I have the body mobility to get to it. I need to imagine the navigational space through which to move 200 meters to get there. There’s a very complex set of relational conditions, temporally structured, for me to get to my car. So when you’re asking about different degrees of legibility, of people viewing, seeing, perceiving, grasping, participating – we’re talking about audience

What I try to do in my work, especially the early work like the David’s Island Strategic Plot, or some of the thematic drawings or notational drawings, is to produce worksheets, things that allow me to advance my thinking on a project.

To be honest, because I was trying to get those drawings to develop the work, I wasn’t thinking so much about whether people would understand them, if they would know what they’re looking at, or if they might be interested in them.

constructions. Who participates, how do they participate, and what do they know? What do they need to know to participate? Cultural perception –who hears what, how do they hear it, and what do they do with that is a very complex set of relations. What I try to do in my work, especially the early work like the David’s Island Strategic Plot, or some of the thematic drawings or notational drawings, is to produce worksheets, things that allow me to advance my thinking on a project. To be honest, because I was trying to get those drawings to develop the work, I wasn’t thinking so much about whether people would understand them, if they would know what they’re looking at, or if they might be interested in them – in the layered drawings, for example.

I used to not pay attention to audiences because I was trying to work on things towards a spatial projection, let’s say, in which then I am interested in what’s being structured, how it’s structured, who participates. I was trying to work out how to get to a spatial condition for audiences, participants. However, I’ve been asked to exhibit and publish my work, for example. Increasingly, I pay attention to who might see it, what they might get out of it, and what they might do with it. There’s that part of it – cultural perception, and who are we speaking to? Which audiences? How long are those audiences in play? What kind of awareness do they need – or not need – to navigate, to perceive, to grasp, to participate in something we do? Then there’s another part of it. I’m interested in audiences now, in terms of how I make work, and if it

20

perry кulper Interview

is out in the world. What are audience backgrounds? What needs to be legible to whom? What do they do with what’s legible? Those kinds of questions matter to me a lot, but I wasn’t so aware of those questions years ago, which I now am, increasingly, over the last three, four years, especially with respect to marginalized populations, and conditions of racism and equity, for example. Histories – who wrote them? Who’s in, what are their biases? What are the political and ethical ramifications? I’m now increasingly interested in who we are talking with in work and that has to do with the scope, or responsibilities, of a piece of work. Who are we talking about? And I don’t think of

Increasingly, I pay attention to who might see [my work], what they might get out of it, and what they might do with it. [...] Cultural perception, and who are we speaking to? Which audiences? How long are those audiences in play? What kind of awareness do they need – or not need – to navigate, to perceive, to grasp, to participate in something we do?

people as subjects. For me, the world is not subjectobject-oriented. The object, the world, is out there, and I’m the subject. I’m not a station point, I’m not a point of view. I’m not any of that. It’s a set of temporarily constructed relational contours that are constantly changing, and we are co-constructing those relational assemblies. The world is more like that for me.

So, I need to be increasingly considerate of the scope of work. What’s a project responsible for? What does it take on? Who does it speak to? Why does it speak to them? In what ways do you do things with the work or not? If I’m working properly, which I seldom do, there’s one other part to the answer.

The other part is that sometimes when people have exhibitions, or even when they post on Instagram, ten times as many people like the things that are physically made. For me, they’re not more or less interesting than digitally produced work, let’s say. We have empathy for making things – techne, everything that constitutes the deep structures of the crafting of things, not techne and logos, not technology. That’s making coupled with logic, rationality, systemic thinking. We respond differently to those crafted things. So that’s another aspect. People might not have a clear understanding of something, but they respond affirmatively to the labor of making something by someone.

To what extent does architectural representation, and in particular, architectural drawing, possess cultural, spatial and political agency in the midst of pressing societal and environmental issues? How does the medium used for representing these issues aid the understanding of the message?

Admittedly, this is a huge strategical mistake of mine – I set out to be a designer. My ambition in the world was to be a good designer when I went to school and when I started to teach.

Bird motels, animals, humans – there are a few things, in David’s Island, for example, in which I try to work on cultural things: histories, references, rituals, storytelling, mythologies. Regrettably, I don’t work on critical contemporary issues and those are important – environmental, ecological, political, ethical, and social issues. I should be working in those kinds of areas. My hope is that in the kind of work that I have done, and the work with students, there is the possibility that through analogous thinking, or through parallel thinking styles – and some students work on environmental things, politically charged worlds and so on – there might be some evidence, traits, or some characteristics that are transferable to different topics, and critical issues, as the students act as cultural agents, as agents of change.

21

What would be your most important message to the next generation of architects?

Architecture must, first and foremost, be a generous discipline. That’s the first thing I say to the students. When I meet students for the first time, I say, health and family are always more important than school, and what we do must absolutely work from a position of generosity – generosity to enable the deepest potential in human and non-human species, to engage with and navigate the world. That’s the extended part of generosity.

Secondly, we need to think of ourselves as cultural and non-human agents, not simply professionally trained architects. I don’t have anything against architects – I’m a licensed architect in California and I’ve paid fees for 38 years, not having built anything. But think of yourselves as cultural agents, agents of change. You’re not problem solvers, you’re not simply service-oriented. You could do those things. That’s not where the differences are made: cultural agency, agents of change.

The third thing has to do with relational structuring, relational assemblies, relational contours. This has to do with thinking more ecologically, not from a biological perspective (although that can also be useful at times), but thinking that considers sets of negotiated, counteracting, interacting relational and material formations. It is not simply about what it looks like, it is not limited to typological thinking, but rather foregrounds temporally structured relationships. Generosity, cultural agency, and temporal, ecological,

[R]elational structuring, relational assemblies, relational contours.

[...T]hinking more ecologically, [...] thinking that considers sets of negotiated, counteracting, interacting relational and material formations.

relational thinking – those would be three key things for me – and mostly deeply caring for and loving the world. The other part of it is to chase your curiosities and fascinations. The best work in the world – that’s what happens. Things you’re fascinated with. And if you can locate those things culturally and historically and so forth, that’s a bonus, but chase your curiosities. The people I respect, dead and alive, basically chase their fascinations and curiosities and work out how to share those curiosities and fascinations with others.

interview from March 5, 2023

conducted by Jasmy Chieh Hsuan Chen, Moritz Kühn, Viktoriya Tudzharova perry кulper Interview

22

[...I]n the layered drawings there are no brakes. I can go forever. I could have a hundred ideas in a drawing. Curating, managing hierarchies, prioritizing how to read things, and then translating them spatially – [...] that’s my work.

Perry Kulper

23

(1)

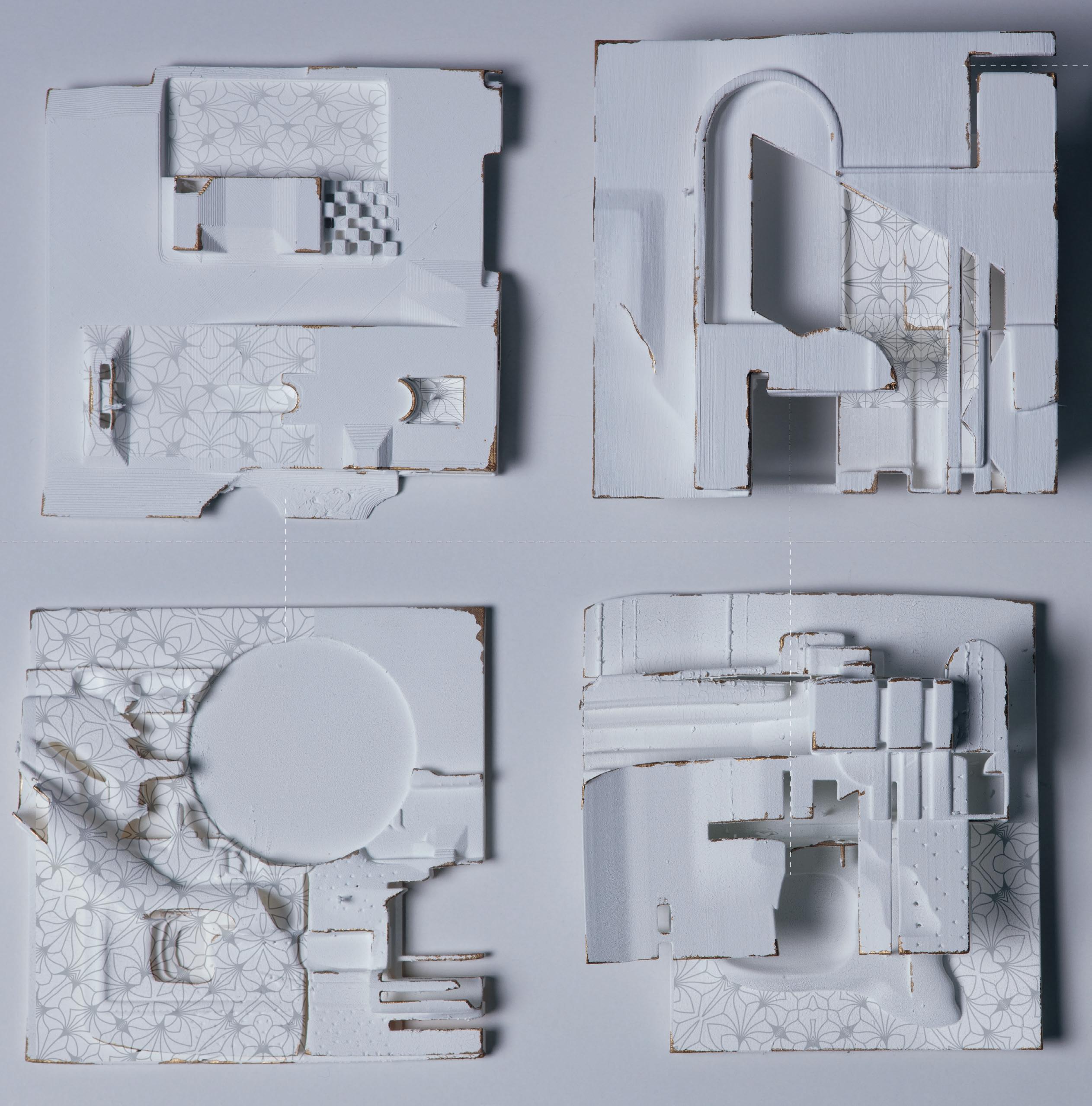

Filtered Transmition

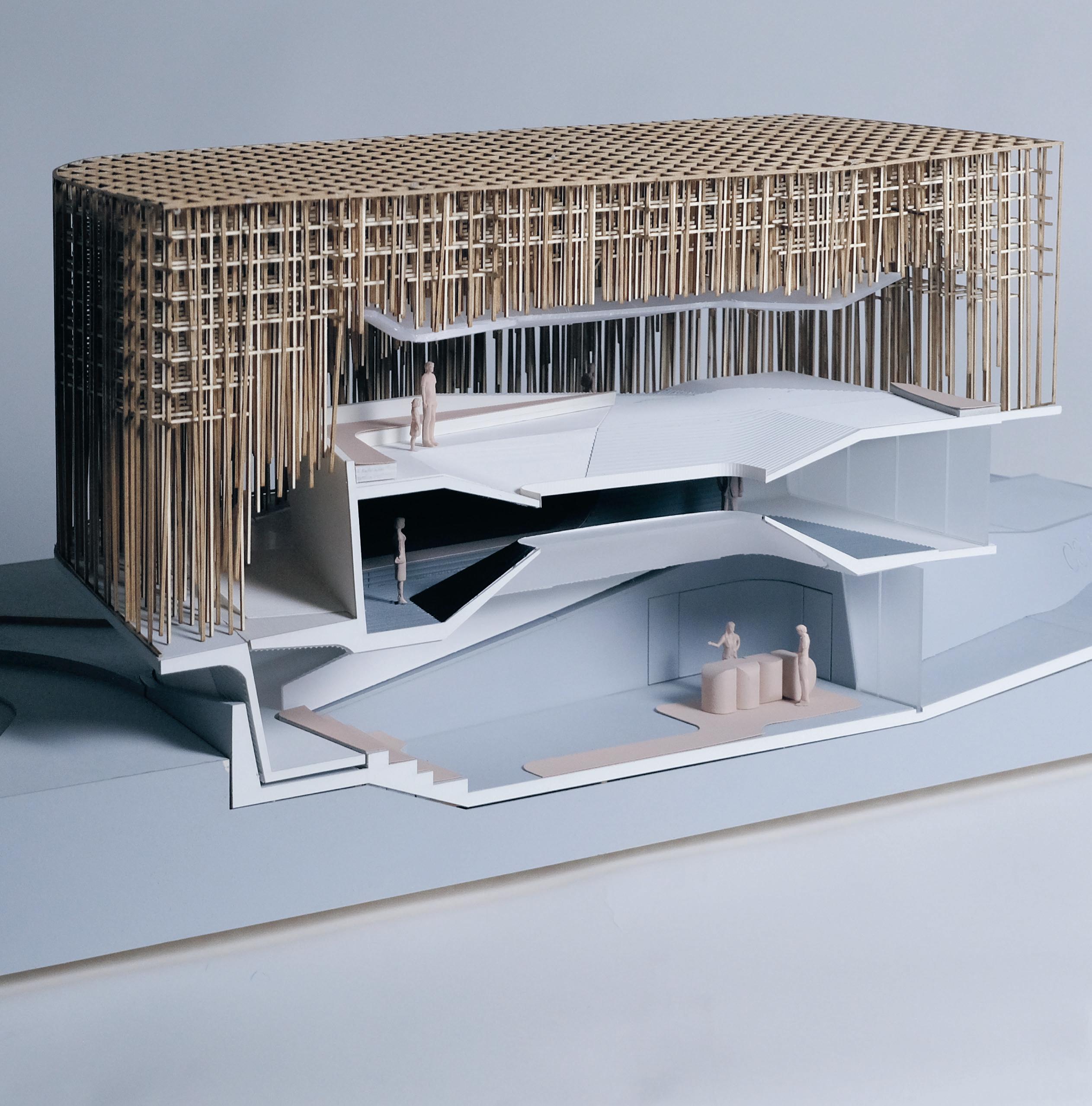

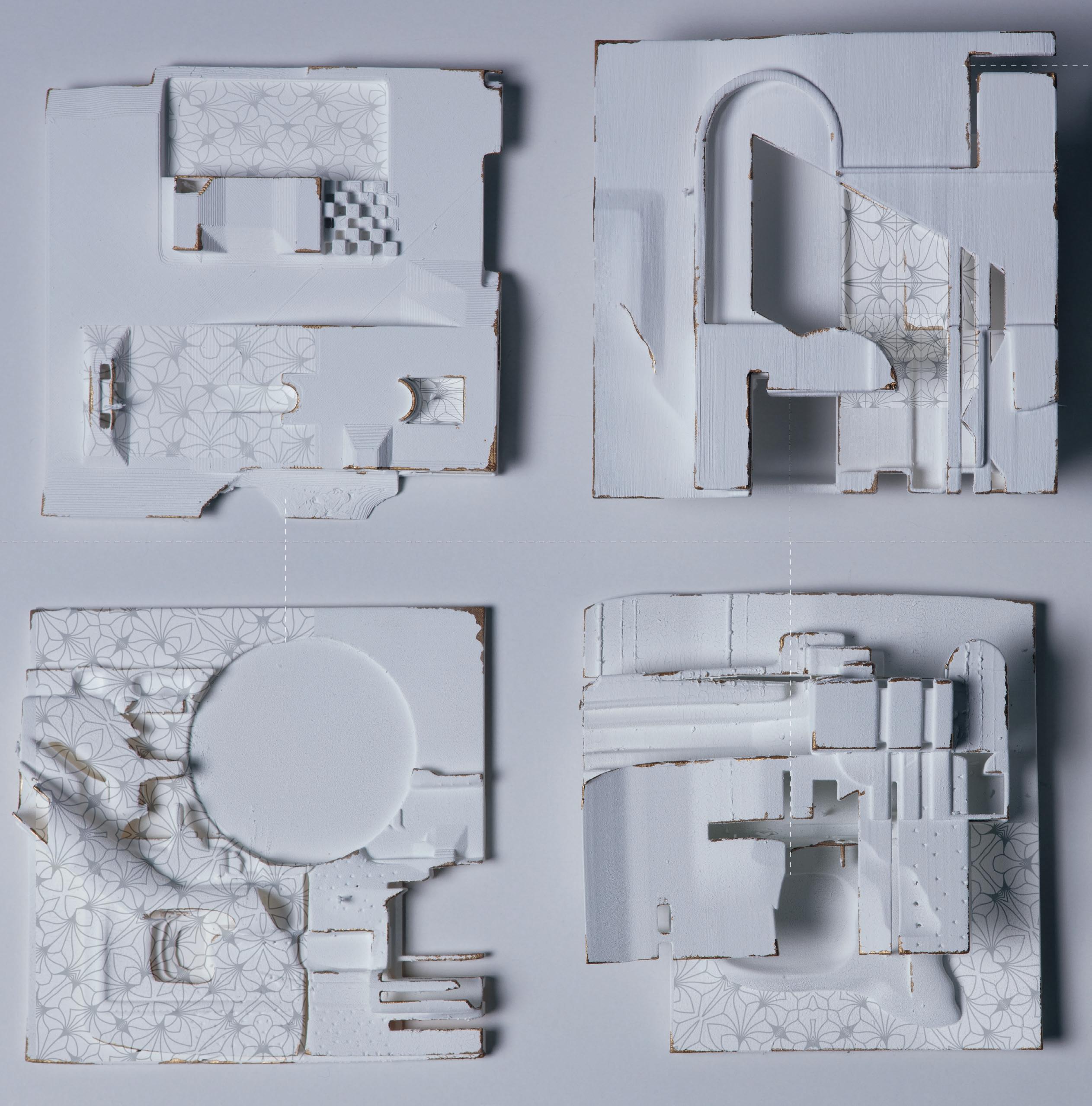

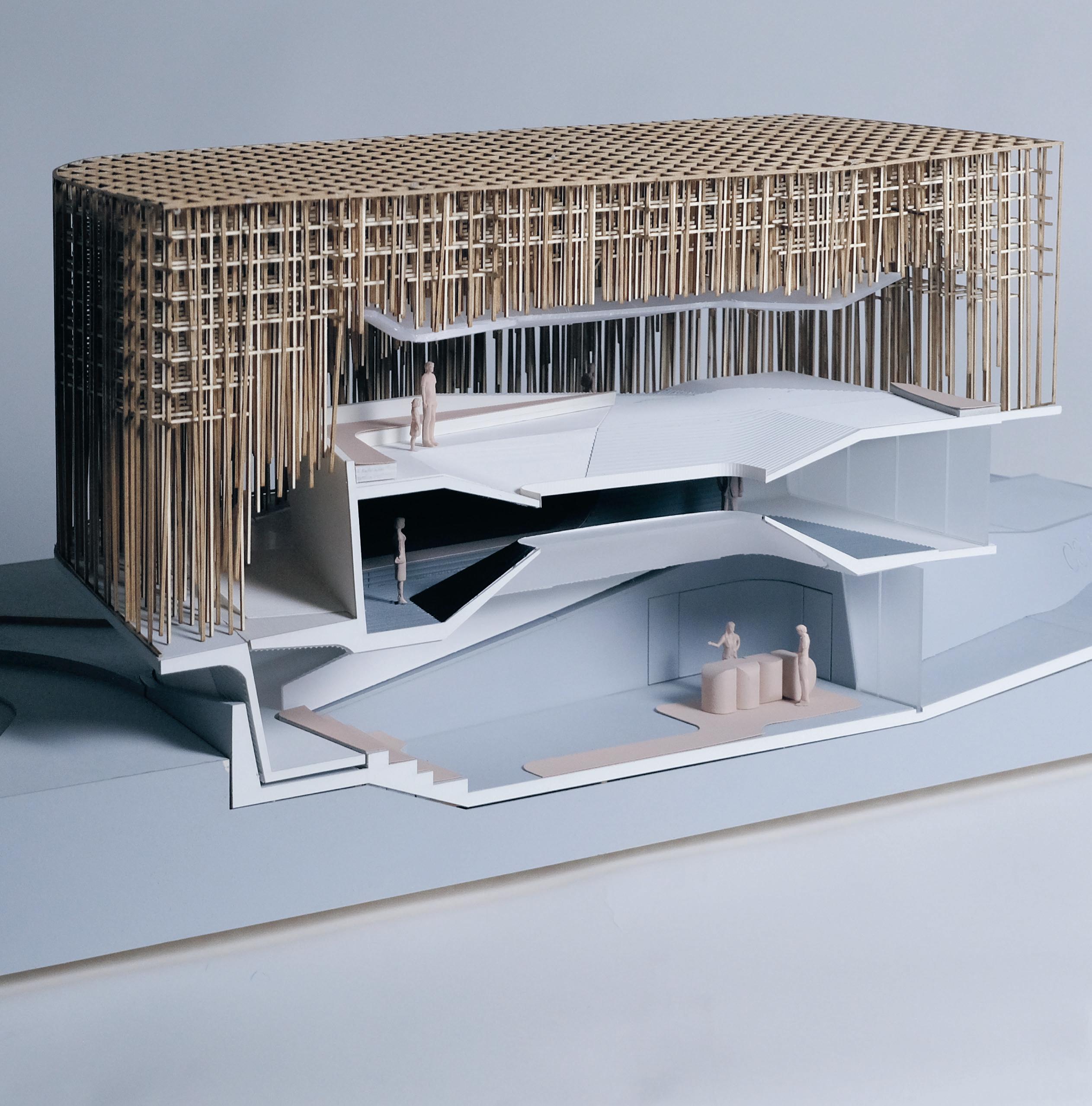

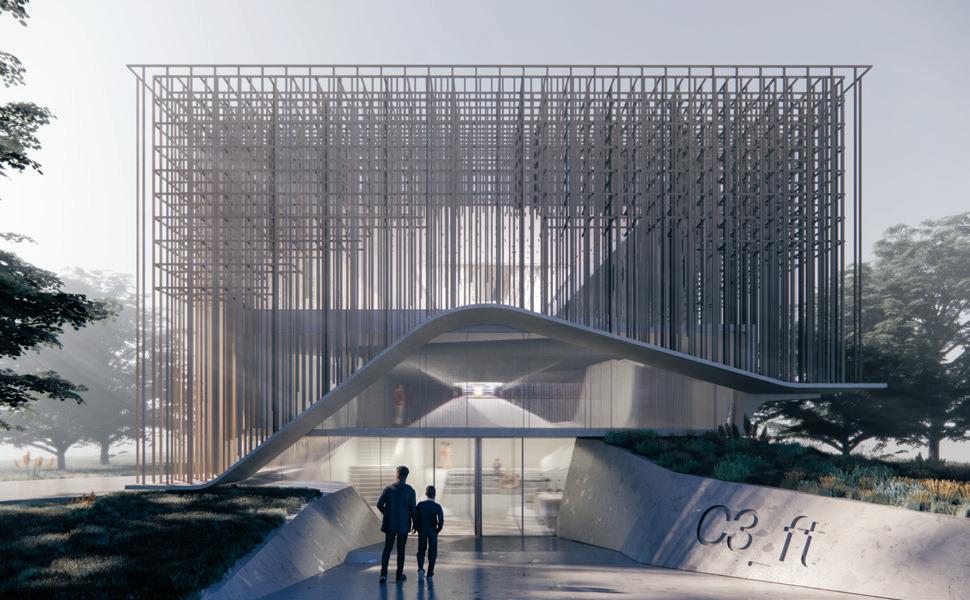

The dialogue with the RB 19 incorporates a series of architectural filters that progressively unveil more information about the vehicle. These filters are designed to manipulate the perception of light, speed, material texture, and social interaction, carefully controlling the transmission and interpretation of information. By gradually enhancing these parameters and detaching the visitor from external influences, the sensory experience is intensified, ultimately aiming to create an immersive experience.The physical model was an essential tool in the design process. It allowed the spatial and aesthetic aspects of the project to be explored in a tangible way. Key decisions were made based on models at different scales. At a scale of 1:20, the manipulation of light through geometry and material texture, as well as the joining and assembly strategy, were explored.

25 studio lynn

Project

PreDiploma

SS23 Project by Tobias Haas

(2) (3) (4)

(1-4) Tobias Haas

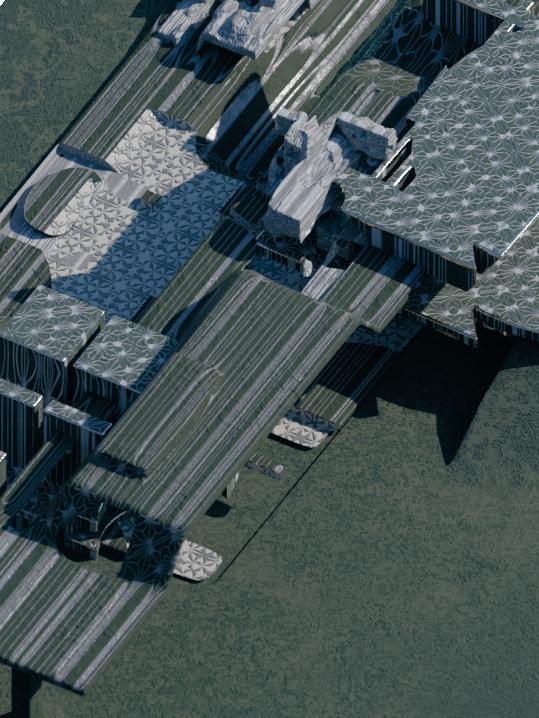

Terrestrial Post-Anthropocene Microperformative Artificial Biospheres

Constantly increasing temperatures are resulting in climatic shifts and habitat loss due to the growing urbanization rate. We are standing on the verge of a sixth mass extinction. By integrating both pre-existing and AI-generated biomimetic patterns into structurally sound designs, we can create the structures depicted in the images. These structures are built to scale, resulting in a complex, porous system featuring flaps and ridges, providing an ideal habitat for both plants and animals. These models are like glimpses into an ongoing time-lapse, forever evolving, never appearing the same twice. 3D printing plays a role in the initial construction, but the process continues through the continuous natural cycle of growth and decay. Water steadily infiltrates the material, nourishing the dry areas and providing a substrate for moss, which gradually extends its roots through the sculpture, disrupting and breaking down the material, thus promoting thriving ecosystems.

26

(1-4) Miriam Löscher

studio rashid Diploma Project

SS23

Project by Miriam Löscher

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

Terrestrial Post-Anthropocene, Microperformative Artificial Biospheres, by Miriam Löscher

Terrestrial Post-Anthropocene, Microperformative Artificial Biospheres, by Miriam Löscher

(1)

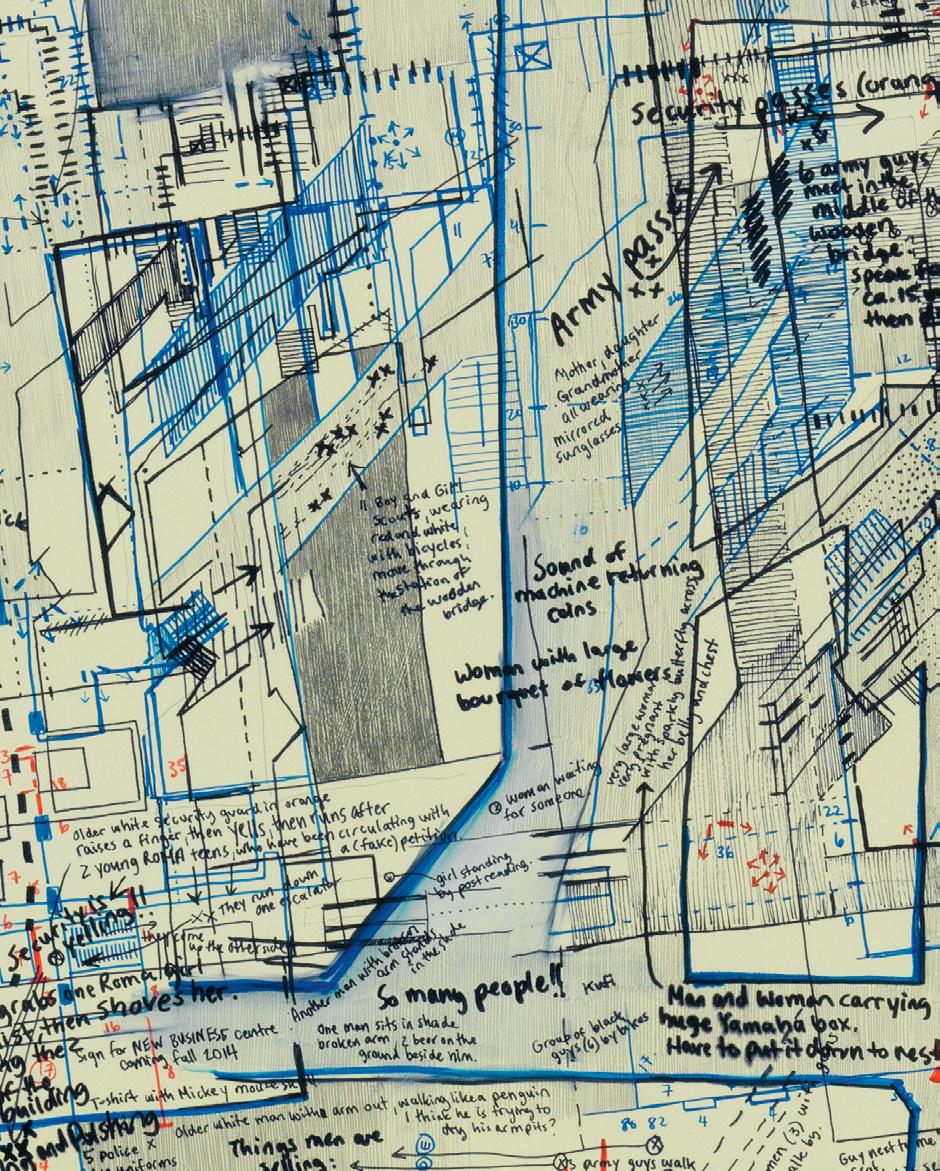

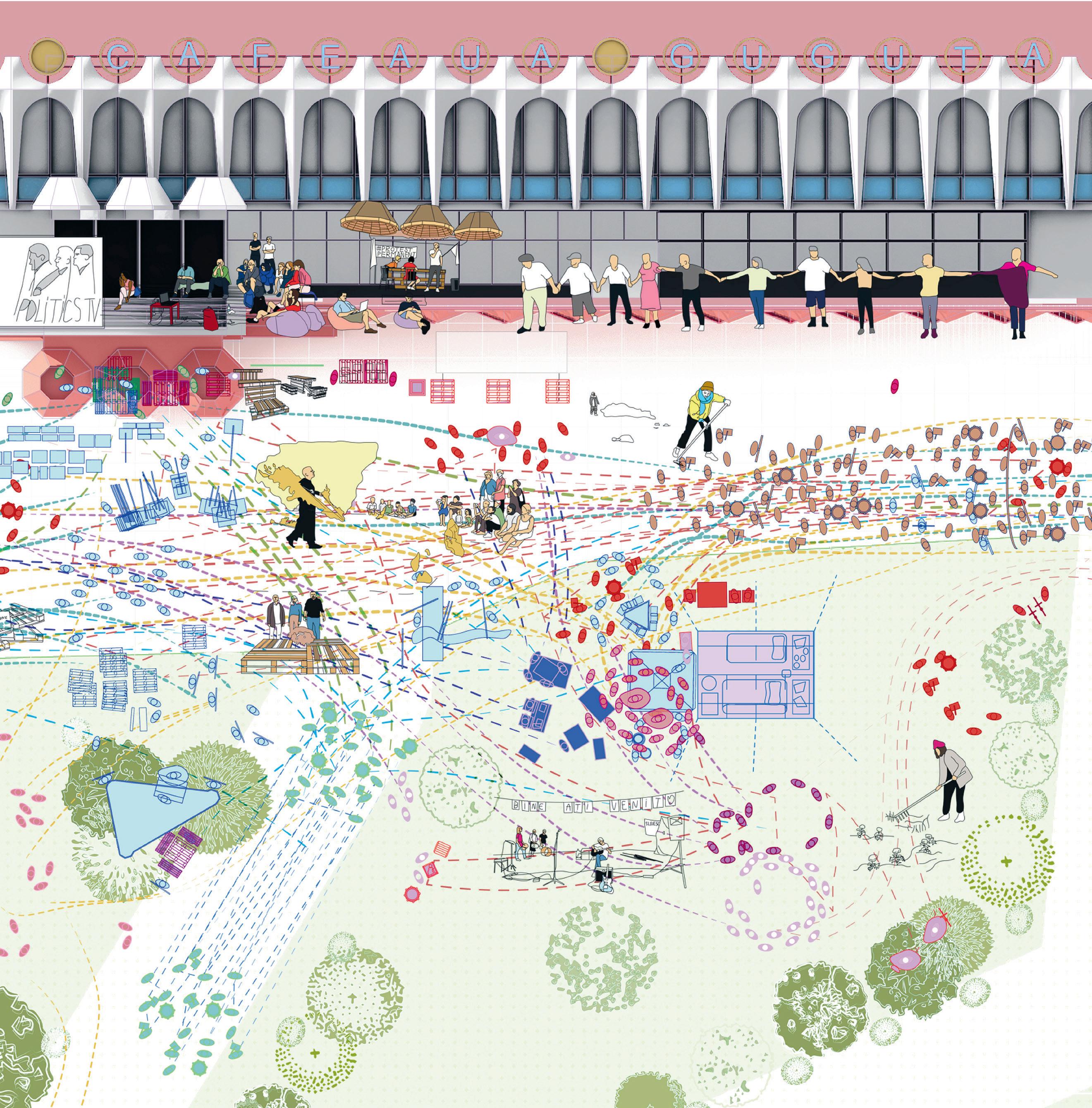

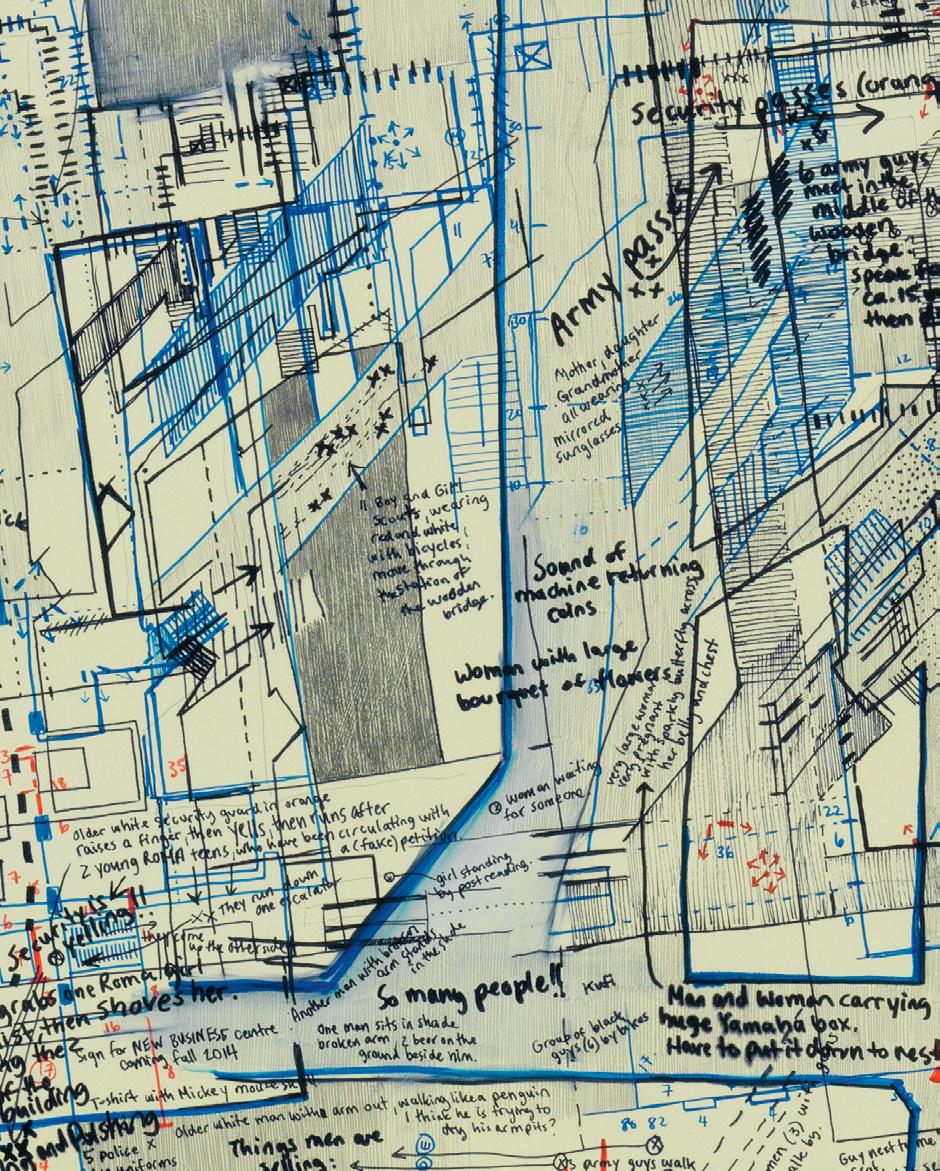

The Bridge of Flowers

The Bridge of Flowers proposes a new social and cultural infrastructure in Chisinau, Moldova, which aims to revitalize and activate the bridge and the river into a new urban center. The infrastructure consists of a new pathway network that extends into the landscape, reconnecting the city with the river-urban wasteland. Along this network, pavilions of various sizes form a public space network where modern culture and tradition meet, with activities such as handcraft, performance, gardening, music and celebration. The initial drawings serve as a tool for investigating and visualizing the density and use of public space over time. Through layering, the movements of various groups of people at different points in time coincide at one space coordinate, telling stories about density, velocity, direction of movement, and moments of stagnation. These patterns intentionally inform the layout of the new public space, creating moments of transit and circulation, as well as moments of slowing down and rest. The design of the pavilions and the pathway network also incorporates elements of the city’s cultural heritage, blending modernity and tradition to create a unique cultural experience.

31

SS22 Project by Ana-Maria Chiriac

(2) (3)

(1-2) Ana-Maria Chiriac

studio díazmoreno garcíagrinda Diploma Project

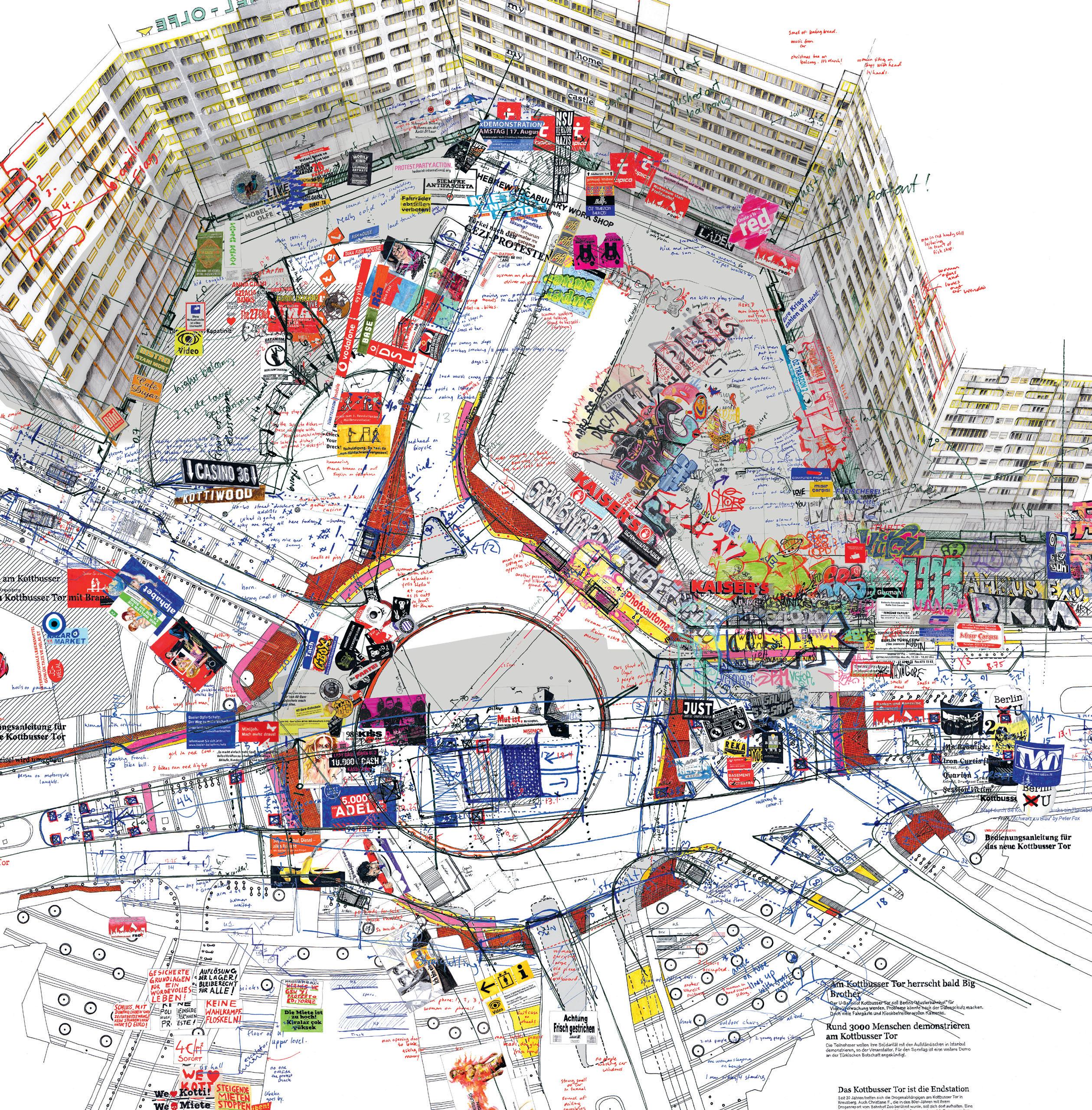

LARISSA FASSLER

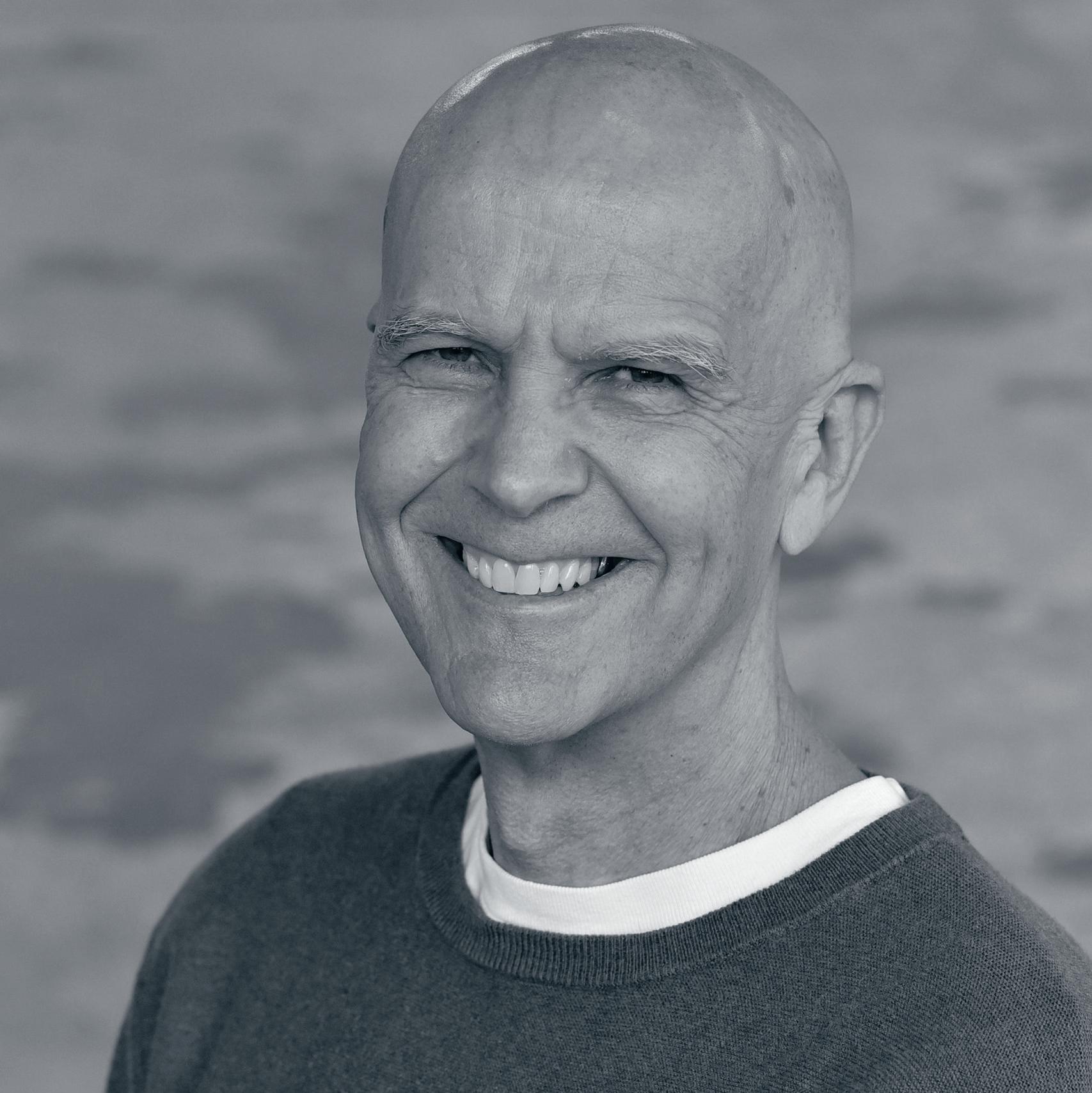

Larissa Fassler is a Canadian visual artist based in Berlin. She earned a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in visual arts. Her solo exhibitions have taken place at prominent galleries and museums such as the Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH (US); the Bröhan-Museum, Berlin (DE), the Esker Foundation, Calgary (CA) and many others.

Larissa’s art captures data about the geospatial politics in cities. Her works consist of cartographic paintings, drawings and sculptures, in which she documents observations of the existing socioeconomic and cultural relations in urban spaces.

32

larissa fassler Interview

Larissa Fassler portrait ©Trevor Good

What kind of projects are you currently working on?

I am currently working on a series of sculptures. I need a better title, but for now, I am calling them

“Timeline Sculptures.” In these works, I am looking at sites where buildings have been taken down and rebuilt repeatedly. My goal is to create sculptures that move through time and represent the different built forms and political complexities of these spaces. The first sculpture in this new series, Palaces/ Palaces, from 2022, depicts an extremely complex and contested site in the heart of Berlin: Schlossplatz. The sculpture incorporates model versions of the former Berlin city castle, the Palast der Republik, and the newly rebuilt Berliner Schloss. Over the next year, I plan to continue creating sculptures like this one, choosing other sites and exploring their history through sculptures that move through time.

How do you define the characteristics, identity or unique qualities of a space which you want to map?

Could you elaborate as well on the methods you choose for actually tracking and mapping?

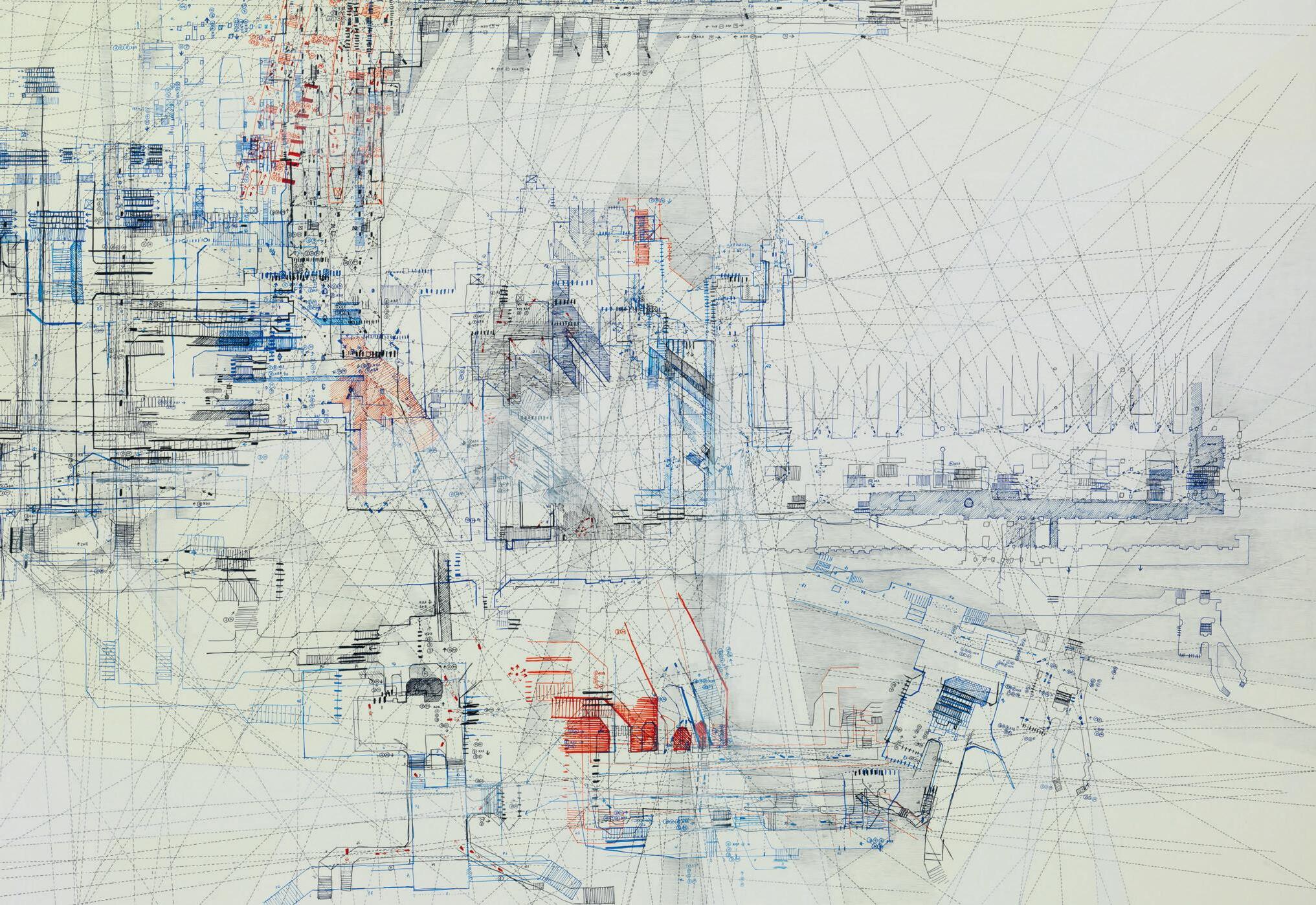

The tools I rely on today in my work emerged from the process of creating my very first model work, Alexanderplatz. Ideally, I would have built off of plans, but I was new to Germany, I didn’t speak German well, and I had no idea how to get the plans of an underground network. That’s when I decided, okay, I’m just going to walk and measure it myself. Initially, I had no idea that this decision would be so important or what it would lead to. But the process of spending significant time on site, walking, counting footsteps, measuring space with my own body, became key, and are tools and strategies that I now try to use on all of my projects. Over my twenty years of practice, I have added many other tools to my toolbox. Another one would be recording language in public space. I love to watch how spaces speak about themselves and I think one can really see this in signage, postering, graffiti and advertising, and how different this can

be from site to site. I like to hang out in places and watch how people use them, who is using them, what language they are speaking, what they’re wearing, for example. While I have a whole collection of strategies, I always try to approach a site without preconceptions. For example, the Gare du Nord in Paris. I like to choose sites that people may not like. Maybe they are aggressive places. Maybe they are places of social tension. Maybe they are places with complicated histories, or sites that people think are failing. A well-designed public plaza is not as interesting as some of these more challenging sites. When I am unsure about how to begin, I turn to my toolbox and use my strategies. Otherwise, I let the site speak to me and discover new things, which leads me to develop new tools to reflect what I find.

My goal is to create sculptures that move through time and represent the different built forms and political complexities of these spaces.

Would you say that there is a certain criterion based on which you decide to map a certain site? Is there a specific reason or is it based on your subjective experience?

I choose sites in two ways. First, based on my own interests, like when I chose to work on the Gare du Nord. The station reflects French society in many ways, making manifest issues of access to the city, mobility, security, poverty, and discrimination based on color. It’s an emblematic site that speaks to these broader societal concerns. In Berlin, for example, I chose Moritzplatz because it reflects the current issues of housing shortages and gentrification. So my choice depends on what I want to reflect and address and which sites speak to these experiences and realities.

33

The second way I choose a site is through an invitation. For example, in 2019, I was invited by the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire, to participate in an artist residency. In this case, the city was predetermined, but the choice of the site was open. I started by walking around the city, identifying its issues, and trying to find places where these are most evident.

We’re curious, did you develop strategies or standards of notation of these issues? For example, did you define for yourself specific ways of documenting time, movement, the social and cultural aspects of a site?

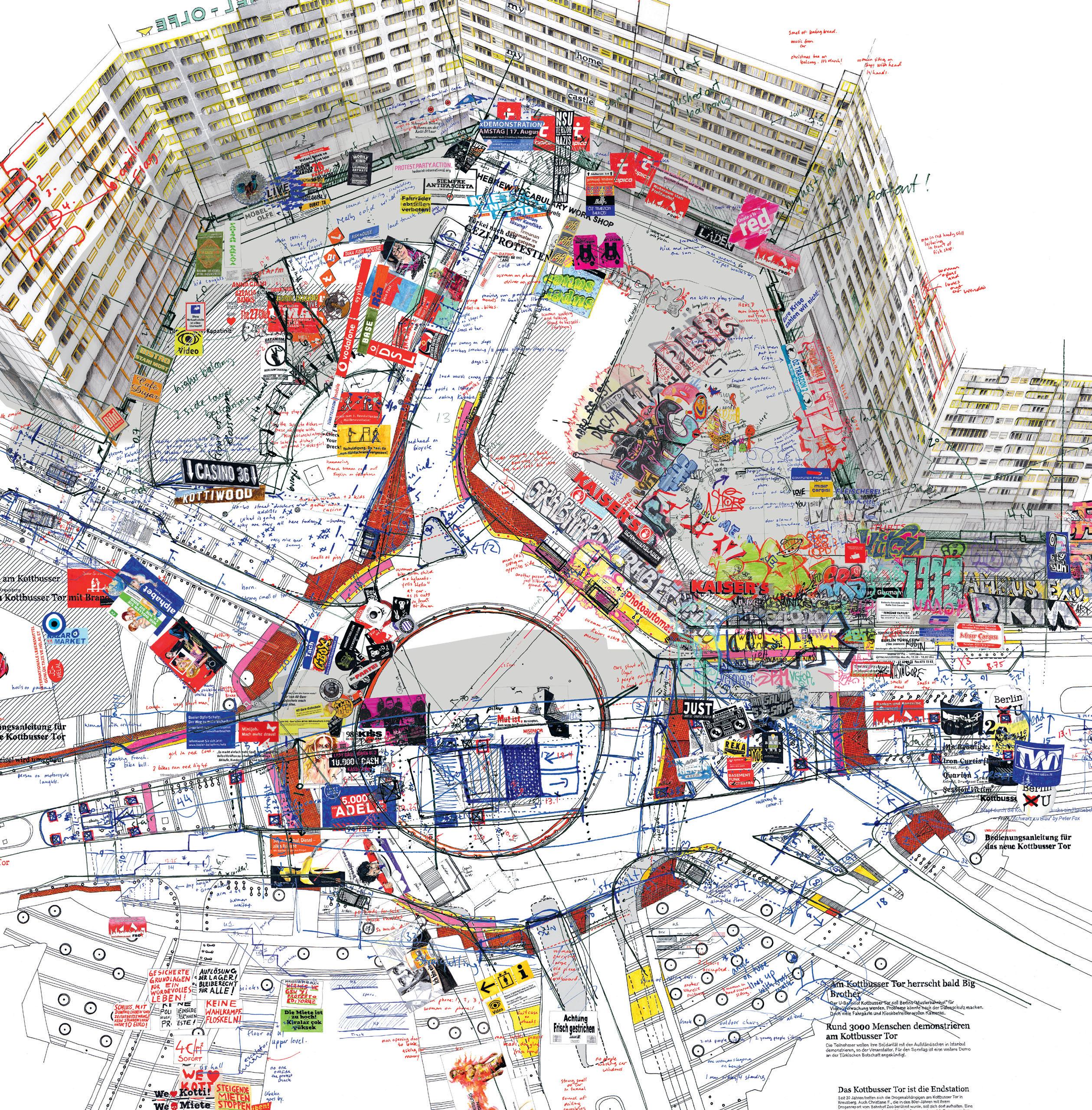

In early works like Kottbusser Tor, I thought I was doing something objective. I wanted to ‘map everything’ – I collected how people moved, where they gathered, what they did. I collected all the signage, billboards, advertising, graffiti and posters, also historical and archival material. I naively thought that that was somehow a neutral act. And then very quickly in this process, I realized how subjective it is, that I am speaking from a certain kind of background and perspective. Then of course it makes you realize that all maps are subjective – what is being represented, how they are laid out, what they portray, and how those maps in fact build reality. As I became

34

larissa fassler Interview

(1)

Place de la Concorde V, 2013

©Guillaume Le Baube (1)

In early works like Kottbusser Tor, I thought I was doing something objective. I wanted to ‘map everything’ [...] And then very quickly in this process, I realized how subjective it is, that I am speaking from a certain kind of background and perspective.

more confident in my work, I allowed my voice to be more present in the pieces. So sometimes I allow humor to come through or a sarcastic comment or anger.

Do you use a similar approach for every site, or is it always site-specific?

No, my approach comes from the site. For example, when I worked on Place de la Concorde, my usual tools didn’t work. I wanted to watch how people hang out on the plaza, but people don’t hang out on that plaza. They cross it. It’s a fast-moving place. I wanted to collect signage – it’s empty of signs. So the way the place represents and speaks about itself is not very present. Despite this, I knew I wanted to work on that site because I was interested in what grand plazas offer the urban environment. I had to rethink my approach and be open to the space: as I watched,

Those movement lines became very interesting and seemed to speak about that place much better than any of the other tools I had previously developed. I think for me it is about being open to the space and allowing things to shift, being playful and testing what works.

I realized that it was a place all about movement. So, I took a stack of A4 pieces of paper with a pre-given map traced very lightly on them, and I selected people and followed them across the plaza, marking their path as we walked. Those movement lines became very interesting and seemed to speak about that place much better than any of the other tools I had previously developed. I think for me it is about being open to the space and allowing things to shift, being playful and testing what works.

In your drawing series Place de la Concorde, you track people’s movement on an hourly basis and overlay these results into a drawing. Do you think that the design of urban spaces could be informed by the process of tracking?

One thing I’m committed to in all my work is this idea that one must spend time on site. Simply going to a site for an hour and walking around and assuming that you know a place is not valid. For my Gare du Nord project, I spent one to six hours on site, daily, over a period of two months. Place de la Concorde was shorter – these were hour-long studies, but every day. I think it’s fascinating what you can learn. People are desperately trying to cross that plaza to get to the Champs-Élysées, and they end up going onto sections where they have to run across eight lanes of traffic or turn around. Therefore, studying a place’s natural gathering points or movement patterns should inform its design. For instance, there should be a traffic light or a crossing on those far-right traffic islands. There is undoubtedly an issue with how that plaza is designed, and Paris is looking to rectify it. They actually want to turn the space into a park and green it.

Based on the significance of the site you choose and the project’s ambition, we can see a change in your method of measuring the city. For example, in the project Forms of Brutality, the method changed from using the body as a measuring tool into seeking more

35

larissa fassler Interview

I find it interesting how much the way I perceive cities is now so strongly influenced and infected by my devices. [...] My experience of walking through a plaza and my experience of navigating Google Maps are now intertwined.

historical or online information about rent prices and gentrification. We wonder how you understand this relationship between the physical space and the virtual, intangible, informational realm. How much is the physical space in a specific moment separable from the digital information in your work?

My practice has definitely evolved over time. At the beginning, it was much more about the relation of the body to space and walking and individual experience. Then, I guess, about midway through my practice, I became increasingly reliant on my phone. In Forms of Brutality, I moved away from the act of walking to map. I definitely was walking the site all the time, but I was not creating drawings based on it. In Forms of Brutality, one can definitely see a relationship to the screen – the map has been rotated and pushed back into space. The perspective is exactly how, with Google Maps, we now can twist and push and pull. I find it interesting how much the way I perceive cities is now so strongly influenced and infected by my devices. I no longer see them as separate entities. My experience of walking through a plaza and my experience of navigating Google Maps are now intertwined. Researching a city’s history and context through online archives and other resources has now also become an essential part of my practice. While walking and experiencing a location physically is still important, I also want to include the historical and archival understandings in my pieces. This allows for a more nuanced and comprehensive depiction of a location.

In your studies, you also used the large-scale models in addition to the large urban mappings. But in some models, it seems like the quantity of complex layers of information relating to the occupancy of the space is reduced in comparison to the drawings. Why is this physical dimension important to you? What qualities and layers of information do you prefer to represent in each medium and why?

The drawings are definitely denser, more text-heavy, and filled with observations. It’s a medium that much better allows for the transportation of information. As an artist, as an architect as well I imagine, there is a joy and a pleasure in making, in building with one’s hands. Sometimes when I do too much painting and drawing, I have a strong desire to build. The sculptures also allow me to explore and understand shape and space far better than the 2D drawings. So, yes, I think I gain a completely different understanding from working in the two modes. You mentioned layering, I think that is what’s interesting in the new piece I spoke about at the beginning, Palaces/Palaces, it became quite text-heavy as well. It contains quotes, figures and lists. It is the first object I have made that is a kind of hybrid between drawing/text/information and sculpture.

How important for you is a sense of temporality, both in your drawings and physical models, and what are the limitations of representing time in terms of scope and span?

Many different aspects of time are present in these works. For example, again, Gare du Nord – when I’m

The drawings are definitely denser, more text-heavy, and filled with observations. It’s a medium that much better allows for the transportation of information.

36

37

(2) Palaces/Palaces, 2022

©Burkhard Peter

in the station, the notes I’m taking are chronological and follow a sequence. However, when transferred to the flat surface of the canvas, they are simultaneous, and time gets compressed in a strange way. I don’t fully understand what that shift means, but I think it speaks to crowds, simultaneity, and many things happening at once.

Another interesting aspect of time in these works is that they function as documents representing a present condition while I’m working on them. But once finished, they quickly become historic documents. The early Kotti works from 2008, 2010, and 2014 capture moments in Berlin that now only exist in the past.

You have revisited Kottbusser Tor a few times over several years. Maybe depending on your state of mind or your understanding of the place, it seems that the

drawings have become a little bit different every time. Can you speak more about that?

I think that some of the differences simply come from being an artist. The 2008 piece is very dense, while in 2010, I wanted to try something different and to make a more reduced piece. The 2010 piece addresses accessibility and the shape of the built environment and it doesn’t have any notes, graffiti, or text on it. The 2014 piece, on the other hand, is again dense. The site changed. A new mosque was being built. There was more cultural and social activity happening, and even more text covered Kotti’s surfaces, so the final drawing shifted once again.

There are sites that I return to again and again, such as Les Halles in Paris, because it’s interesting to build on the understanding of these places that I already have.

(3)

Kotti, 2008, detail

©Larissa Fassler

(4)

©Larissa Fassler larissa

Kotti (revisited), 2014

38

fassler Interview (3)

(4)

40

larissa fassler

Interview

(5)

Gare du Nord III, 2014 – 2015

©Jens Ziehe

(6)

Gare du Nord III, 2014 – 2015, detail ©Jens Ziehe

(5)

So do you ever see your work as finished, or is there always a possibility that you might revisit it in the future with a different understanding?

Of course. No, these works don’t really finish.

Your works represent a subjective measurement system that aims to reveal a new experience of existing built conditions. Are they also suggesting that established architectural practices are obsolete and how would you suggest that these practices should change in future when designing space for people?

I find that question really provocative. I’m not saying that architectural practices today are obsolete. I also can’t really comment on architectural practices today because I’m not in architectural schools or in that field. So I’m not actually aware of how you are taught or the conversations that happen in your classes. However, I strongly believe that one cannot design for a space without a deep understanding of it, and that that deep understanding can only be achieved, in part, through actual site visits – spending time on sites, and getting away from the digital tools.

To introduce you shortly to our university: we have three different studios, led by different professors. The first studio, led by Diaz Moreno and Garcia Grinda, is particularly focused on looking at a specific urban situation, trying to understand the different complex layers and trying to visualize them in any medium, be it drawings, models or animations. In the second studio, led by Greg Lynn, for a few semesters, the focus was on studying or predicting people’s movement patterns through a site at different times of the day, but using a very different methodology – agent-based simulations. We got really interested in your work because it deals exactly with those issues but from an artist’s point of view. We find it very inspiring to see how you understand time and change at a certain site, the tools and methods you have developed to measure

it, as well as how highly you value subjective understanding of place. We find all of this very provocative and insightful.

Let me add something here about subjective understanding and some of the newer tools that I am exploring now in my work – such as color, mark-making and gesture – to carry knowledge and meaning. In the Gare du Nord works or in Forms of Brutality, I allowed mark-making to become more expressive. In fact, there’s almost a plastering or hitting of the surfaces. When you’re close, the marks are quite violent, fast and aggressive. In the Gare du Nord series, there are smears of yellow paint and

41

(6)

larissa fassler Interview

As my practice has matured, I have come to realize that the non-verbal –color, linework and mark-making – also transport and carry emotion, meaning and knowledge.[...] In later works, I allowed for more complexity and perhaps more of the non-verbal or body-based understanding to come into the works. graphite reminiscent of dirt, smears, or urine stains. As my practice has matured, I have come to realize that the non-verbal – color, linework and mark-making – also transport and carry emotion, meaning and knowledge.

My earlier works are much more graphic and more easily readable. In later works, I allowed for more complexity and perhaps more of the non-verbal or body-based understanding to come into the works.

What would you suggest to the future generations who are designing urban spaces?

That’s not quite the intent of what I’m doing, I mean, making suggestions for the design of public space. I know that that is a question from the field of architecture or urban design – how to improve or make a space more successful? I think my work is primarily focused on the creating of thick descriptions of existing places in order to understand the societies in which we live. To be honest, my mind does not necessarily go into how to fix places or how to make places better.

As for advice to people coming up in the field – again, what I feel I can add to that conversation would be the idea of coming back to spending real time on sites and avoiding preconceived notions about them. It’s funny, even in my own work, there have been moments when I’ve taken a shortcut and have

just used Google Maps to explore a site. You get so caught up in these powerful digital tools, their speed and ease, and then all of a sudden you realize that you haven’t even walked to the next corner. I am very committed to and convinced by the tools I have developed over the last twenty years, but then I too forget about them and fall right back into designing from a laptop or from a computer. I think that’s what I would really underline – the importance of getting out into the world and observing how people use spaces, rather than relying solely on our assumptions about how a space should work.

We are convinced that more actors should be taking part in a conversation about urban spaces, and not only the people who are designing the spaces. That’s why your opinion is really important for us.

interview from March 7, 2023

conducted by Jasmy Chieh Hsuan Chen and Viktoriya Tudzharova

42

When I’m [on the site], the notes

I’m taking are chronological and follow a sequence. However, when transferred to the flat surface of the canvas, they are simultaneous, and time gets compressed in a strange way.

43

Larissa Fassler

studio rashid

Studio Project

Project by Saba Mahdavi, Soroush Naderi, Anastasia Smirnova, Humeyra Cam

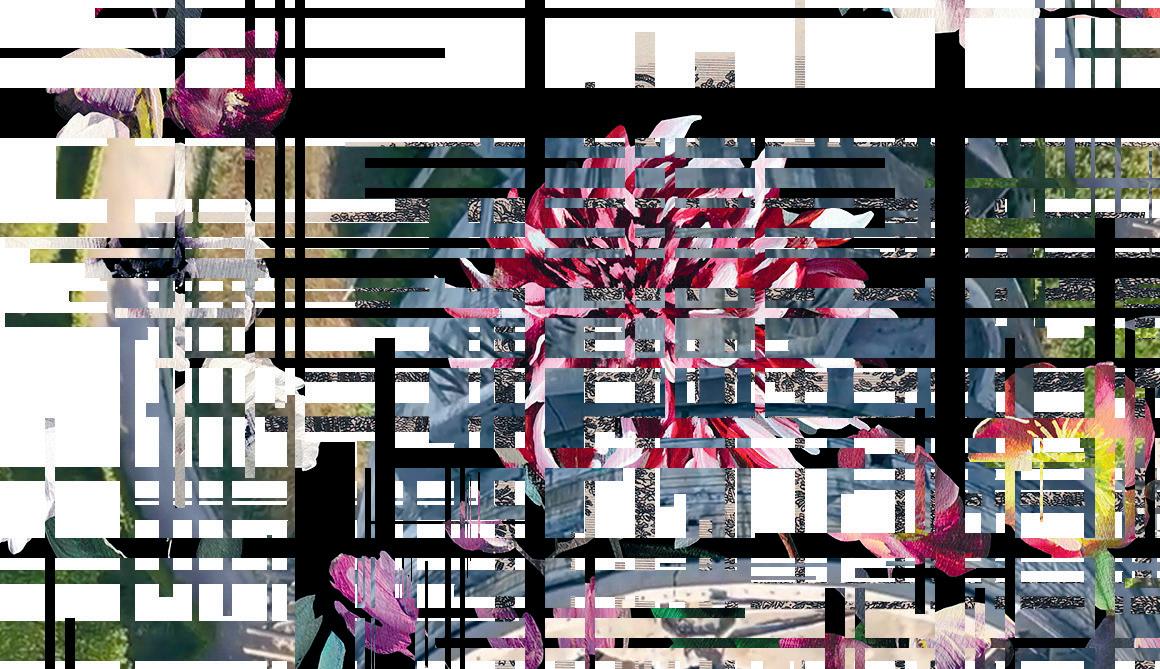

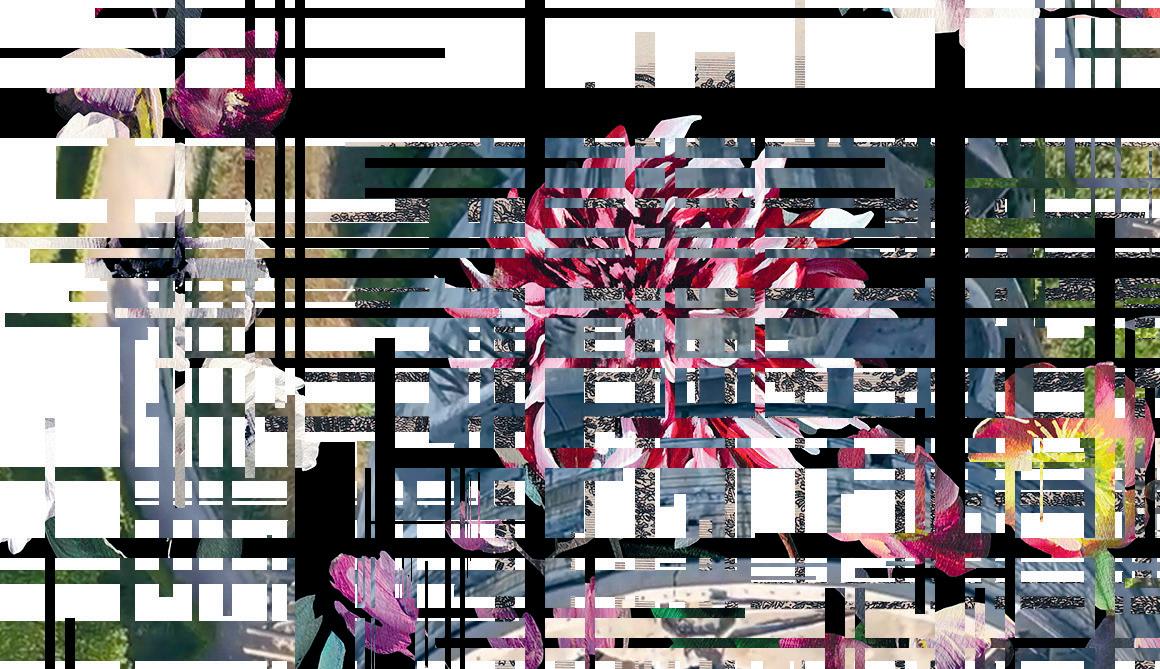

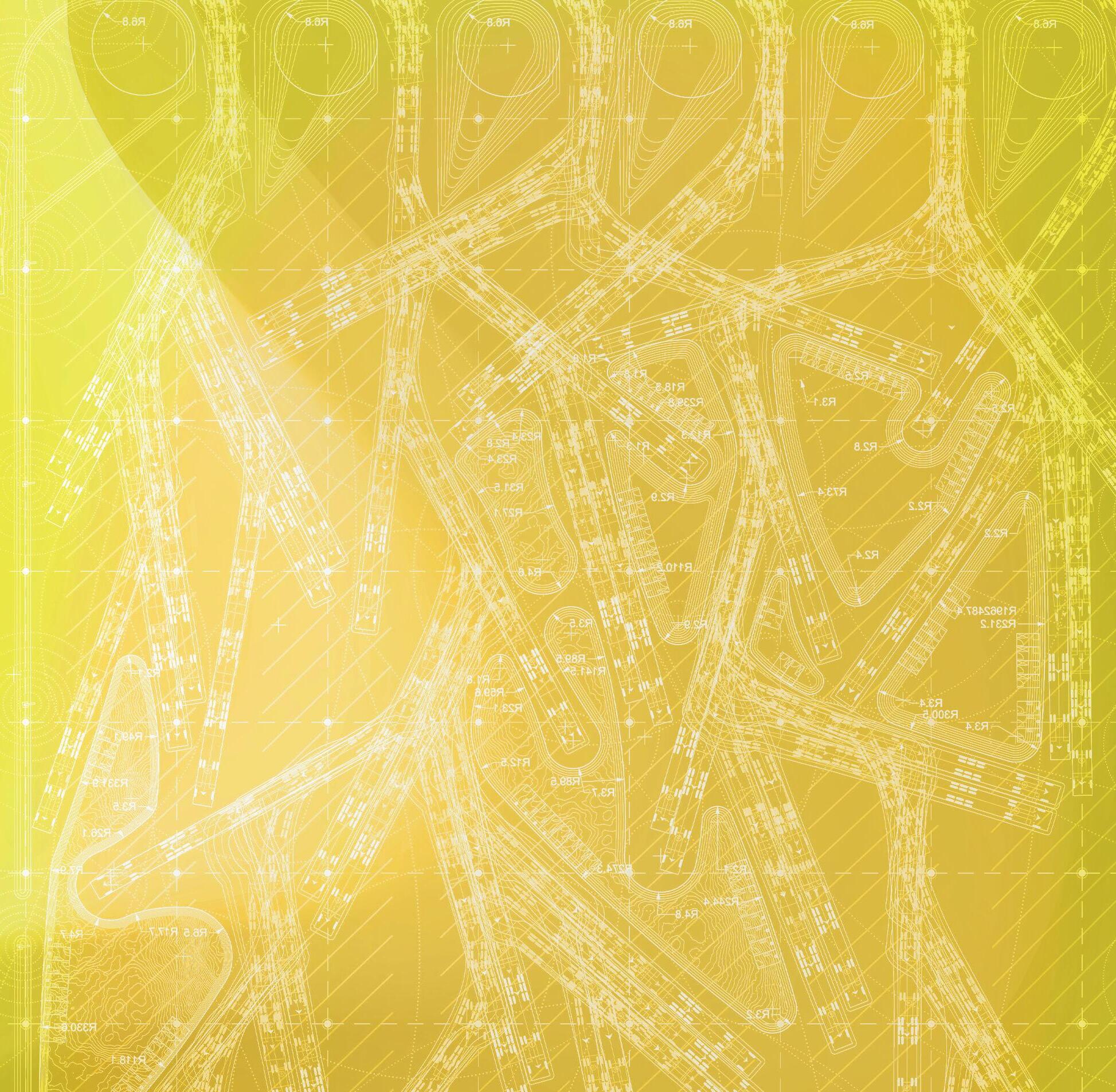

Paradigm Park

This project offers a landscape responding to temporal fluctuations, a time-oriented approach. An architecture over the temporal scales of ecology with inherent aesthetic quality. A colorful 3D tapestry of flow and density map are created, which brings conglomeration, idiosyncrasies and unpredictability. The aim is to map all of the forces of deep ground (landscape) as formal figures and not as a contextual approach, or a referential take (architecture). We worked on the components as an x-ray representation or an opacity play with the landscape object in order to input imagery into landscape systems and reassemble the outputs artistically and procedurally. Looking particularly carefully toward patterns, colors, textures allows for a contemporary design look which is quite literal, with landscape visual and analytical data.

44

SS22

(1-3) Saba Mahdavi, Soroush Naderi, Anastasia Smirnova, Humeyra Cam

(1)

(2)

(3)

(1)

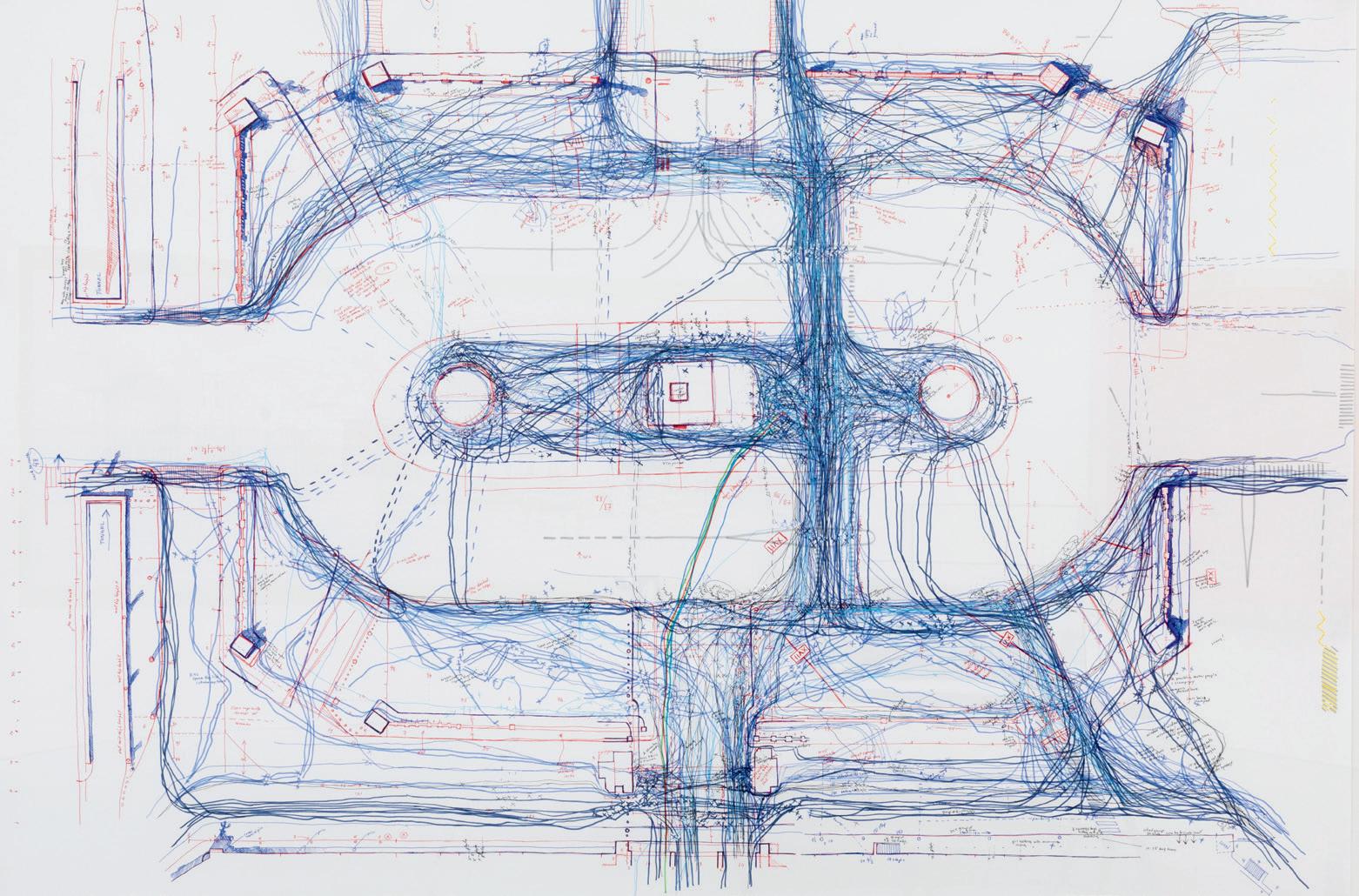

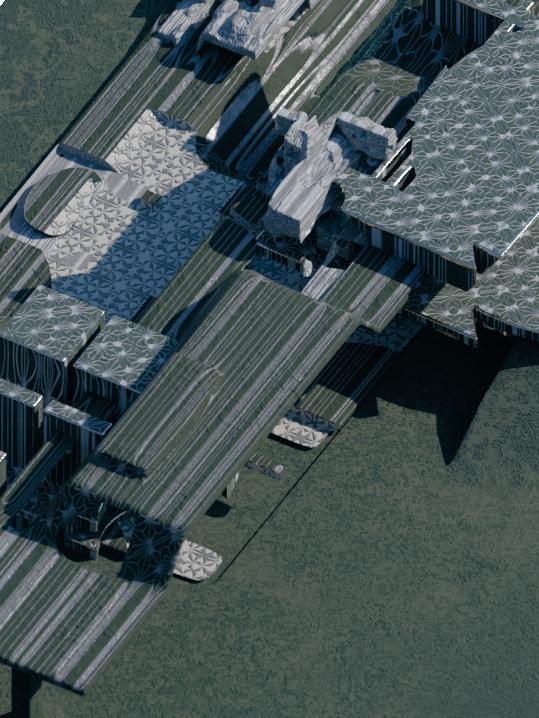

Within Milieus of Movement

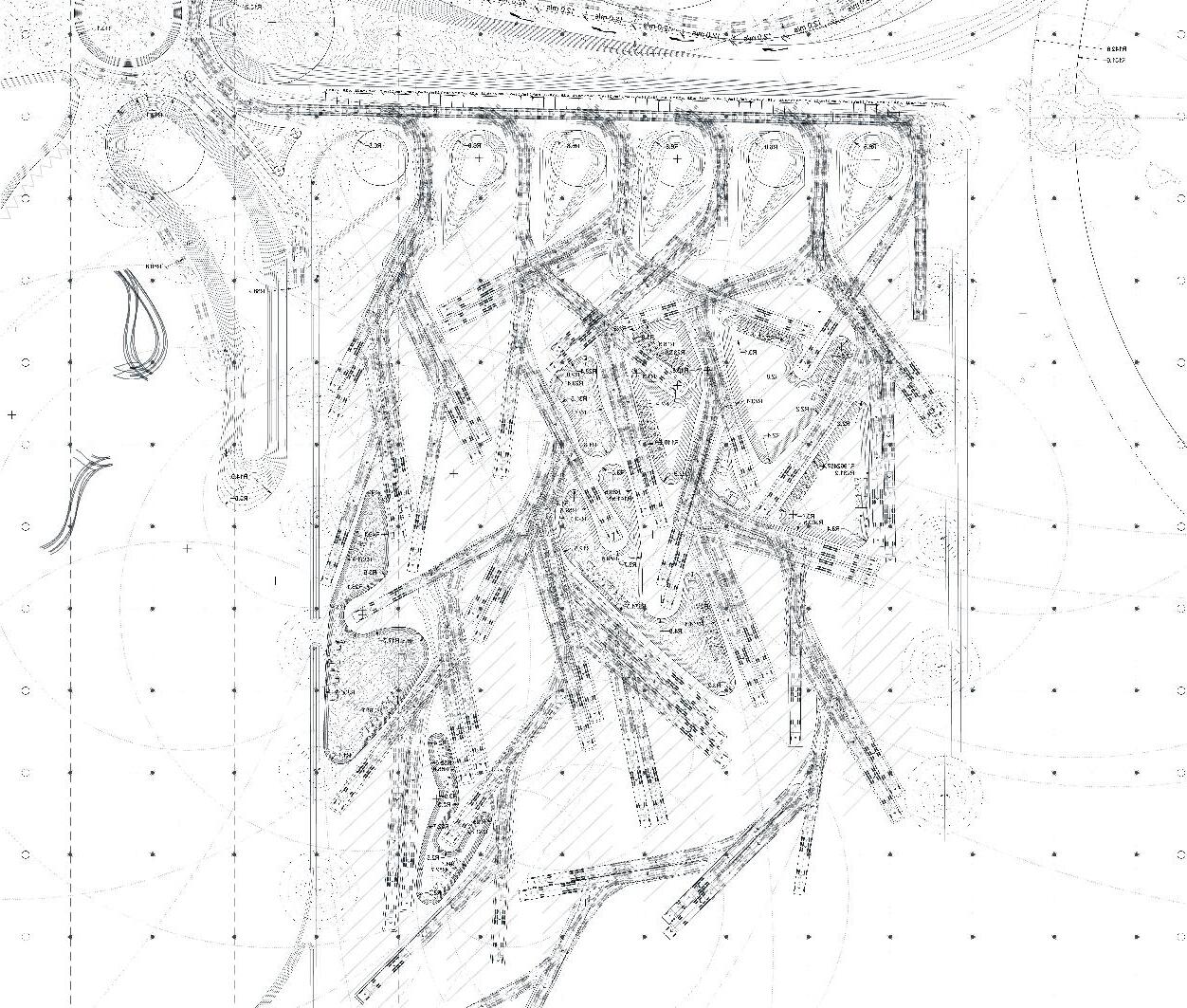

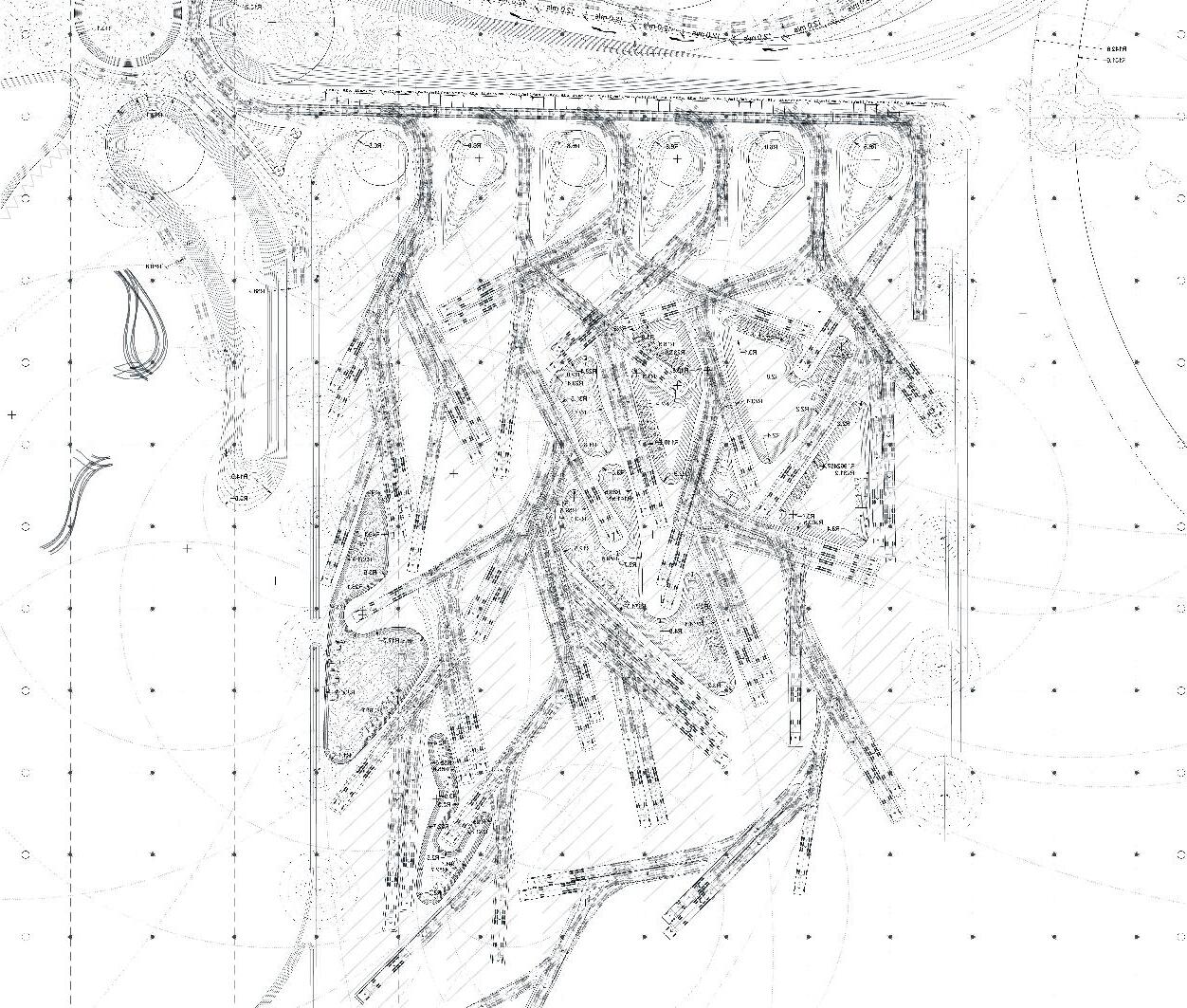

This project works on different scales of European logistics and explores the impact of how economic forces are physically manifested in the built environment in the form of infrastructure spaces. In a study of a logistics park in the Czech Republic, the project investigates how to deal with the local impact of such an infrastructural node point and proposes an urban system that would reconnect it to its surroundings. The project introduces models of temporary inhabitation and dwelling in infrastructure

space, by hybridizing different programs in vacant spaces between warehouses through roof modules, earthworks, and paths of humans and machines. The drawings and models show different studies of world-making within infrastructure space. In order to design in the world of infrastructure, the various elements must be read, reproduced, and further developed, following their own logic. The logic becomes the medium of the design development.

47 studio díazmoreno garcíagrinda Diploma Project

SS23

Project by Moritz Kühn

(1-3) Moritz Kühn (2) (3)

Geologies of Accumulation, by Diana Cuc

Geologies of Accumulation, by Diana Cuc

(2)

(2)

Terrestrial Post-Anthropocene, Microperformative Artificial Biospheres, by Miriam Löscher

Terrestrial Post-Anthropocene, Microperformative Artificial Biospheres, by Miriam Löscher