11 minute read

MAEID

Your recent work Magic Queen uses a new 3-D printing method with soil that you have been researching and developing. Can you describe the motivation behind this research and why new construction methods and materials are needed to support future ecologies?

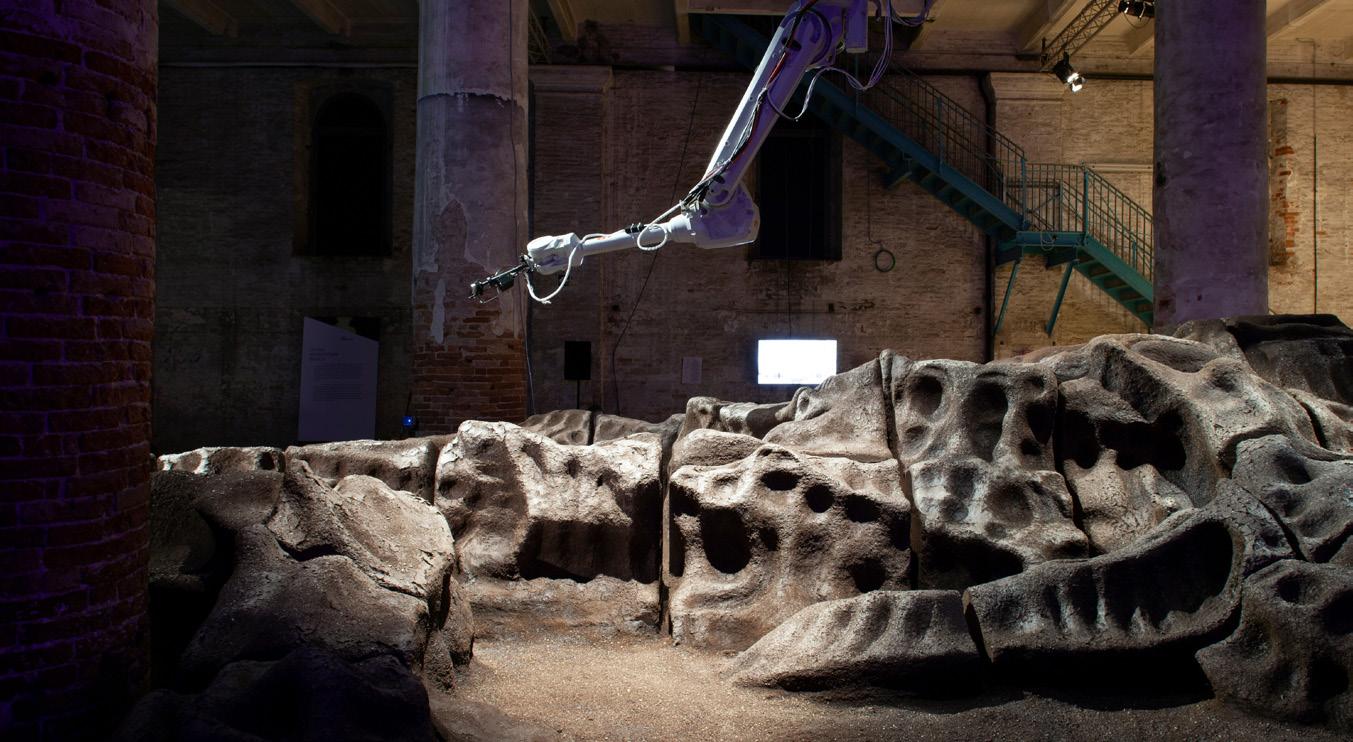

Daniela Mitterberger: For MagicQueen, we were using soil, which is a very interesting material, because it’s a substrate, which means it’s something that allows you to actually grow life, so it’s something that is not a dead entity.

Advertisement

We have this urge to produce, and when we talk about ecology, we talk about creating architecture that is not in contradiction to the natural environment. We believe it’s very important to actually be a truly biodegradable and sustainable building, which includes, of course, multiple steps. Especially in digital fabrication, we often hear this idea of sustainability of processes, but with soil, it really allowed us to be biodegradable throughout all the steps. So that means that throughout the whole process, we can actually reuse the material later. That means, even though we build architecture with it, we build a landscape with it, you can put it directly back into the garden where you got it from. Soil is a granular material, it behaves differently and it allows you to create complex forms at the same time. It makes it possible to be sustainable and host plants and other species within your environment.

I think that that is the super important thing. It changes how we see and understand architecture, because suddenly, it is not just a shell that is encapsulating us, but it’s actually more a medium for negotiating our presence with the environment.

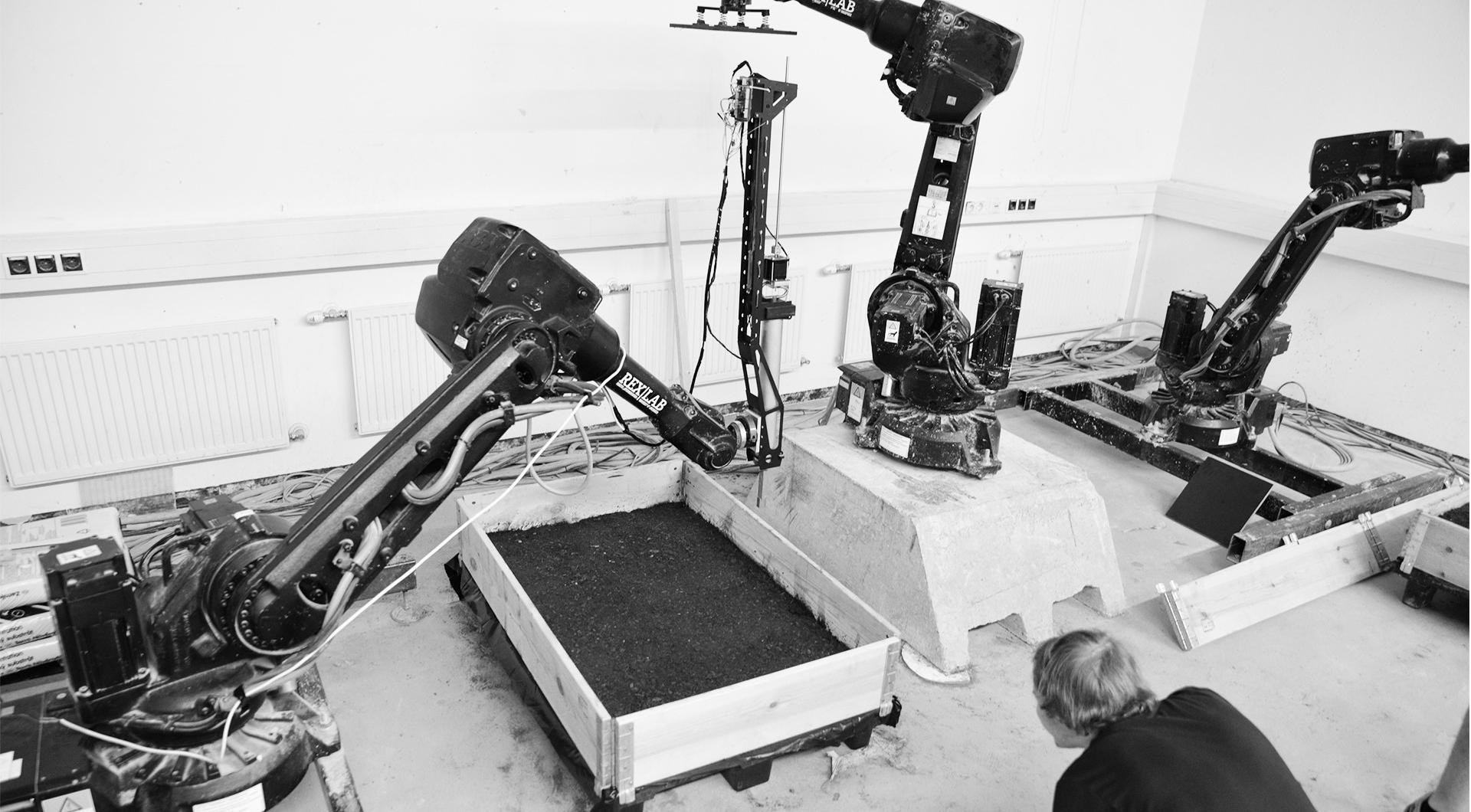

Tiziano Derme: For the first time, we really approached a scale of production and fabrication here that was quite ambitious. Because we are talking about almost a hundred tons of compressed soil and a robotically, fabricated structure, which is actually confronting this kind of use of robotic fabrication of these new materials with a currently existing problem: How do we place these kinds of current biotechnologies or new ways of manufacturing on a scale that is beyond the lab scale? There is a lot of very interesting research, including that which we are currently doing, taking place here at the Angewandte with the Co-Corporeality project. They are having difficulty scaling up because of very specific requirements for the environment in which those structures of materials are being placed, as well as in terms of the complexity of processes. To make a large structure of concrete in terms of fabrication could be understood as a quite straightforward approach. But what if you have solutions that get contaminated and you have liters and liters of solutions that need to be prepared? What if the material dries too quickly? What if the material is highly responsive to environmental fluctuations, such as humidity or temperature? With this project, we wanted to confront ourselves a little bit with a different scale. What is really problematic in terms of a kind of larger picture for architecture, is the relationship between the architecture and the natural phenomenon, which was always a very problematic one, so if you understand architecture as something that is embedded in an environment, but as a kind of act of betrayal of the natural environment at the same time. Therefore, we need to contextualize critically: What is this natural relationship between how we assemble materials and how we consume or tend to natural resources?

Your projects often bring together both natural systems, such as soil and plants, and artificial systems, such as robots and AI, into one single environment. The relationships created between these contrasting systems in your work challenge our understanding of natural environments. Do you see our understanding of nature blurring and how would you define it?

DM: We have to be very careful when we use that term ‘nature’ because it is a term that has been widley discussed over and over in theoretical and built works. It’s something that we have to redefine continuously, especially in our times, we have to redefine what it means. This idea of ‘wild nature’ doesn’t exist anymore. We know that there are cultural landscapes, created only by us humans. This understanding of our influence on the natural environment is something that is starting to become more common knowledge. The more it becomes common knowledge, the more we are starting to understand that we are dealing with complex systems. At the same time, we are already interacting with them. That means we are already shaping them, so we better start to learn what we are doing faster. It’s a big job for the architect to start to understand this. It also means incorporating the complexity of systems and ecological systems, this idea that machines are generating natural environments or being used to produce natural environments. We want to use machines, especially robots that are normally used to automate things, but we don’t want to use them to automate or control nature, but to actually produce a nature that is independent, that means nature can actually evolve by itself. And we have the technology to do that, it just depends on how you use it. Currently, we are using machines and landscapes to control soil, or control nature. That means that we have the feeling of control, but we are not looking at the long-term. We are more interested in creating environments that can sustain themselves or create something new: this kind of idea of a new ‘wildness’ that is generated by incorporating machines, and that these machines are then stimulating specific ecological processes or natural processes in the systems. And by doing that, we are actually creating an architecture that is not in this juxtaposition to nature or solid or opposite forces of, you know, human versus nature. Everything has an influence on each other, all agents are working together. This really works by just first isolating it and simplifying the problem, and then starting to bring the complexity of systems back, slowly incorporating more agents and more things. For this approach, we need to use materials and systems that allow us to do this. We use AI because it allows us to learn without requiring our immediate input. It can use robots because they can work by themselves. They’re self-sufficient and at the same time, they are able to actually react to changes. It is very important to say it needs to react, so you give up control. You might set up a system or a framework, but you don’t have 100 percent control over what is happening. That means it might not grow. It might be contaminated. It might lead to a different result.

TD: Maybe I can add some reflections on the terminology. At the moment, when we talk about nature, we make a distinction between nature and our position. This results immediately in us talking about nature as something that we are not part of. This is the first very problematic use of the word. So first of all, the word “nature” was coined by Ernst Haeckel, and the way he described it was as this kind of dynamic exchange between living creatures and also the relationship between them and the environment, so it is something that is highly relational. And this, from our perspective, immediately falls into how we place technology within this.

Technology is also a very, very relational construct. Technology does not exist in a vacuum, it always plays critically with cultural context. And this is what we are trying to do, to mediate ecology through technology. That’s also what Daniela mentioned before, and this is what leads us to reflect on terms such as this idea of ‘wildness,’ which is very different from ‘wilderness.’ So if something is wild, we normally associate it with something that is very far from any human presence, which depicts this image of, untouched, nature, but in fact, ‘wildness’ refers rather to a behavior. It’s a behavior of a very specific living organism or environment actually. So that is defining a sort of a system of rules and relationships. So this is what we have experienced somehow with blurring the limit between what is natural and what is technological, which is very different from using technology to maintain or domesticate an environment. Agriculture was the very first example of the domination of nature. Also, the garden is actually a spatial construct where nature is domesticated, in common terms. So now, when we use the term ‘garden,’ it is actually used to discuss this relationship.

Has art been a better and easier medium to translate your ideas and visions and to communicate them to other people? Do you have the desire to translate your projects outside of exhibition spaces?

TD: Generally, the practice, for us, is a very expanded domain of action that doesn’t fall within a boundary where we need to defend the fact that we are architects. I’m not worried. I think also, Daniela, you’re not worried at all, when, you know, they call us artists. I think we should not be scared of this. But we should try to place our work within different contexts and today, especially as a young practice, this means expanding a lot of the domains of action, which are sometimes videos, sometimes installations, sometimes buildings.

We have projects that are dealing with a different temporality. The exhibition is something that exists in a very specific timeframe, while the building, as we normally understand it, exists forever. And this is also something that we would like to question as well. How long does this architecture need to last? And of course, we have the intention to expand what we do outside the exhibition, but in terms of temporality, not in terms of doing a building for the sake of doing a building, but more as a kind of form of exposure.

DM: In a lot of our exhibitions, we never exhibit the same things twice. So we always use an exhibition as a driving force to push a project further. Exhibitions are actually these moments of coming together with people and discussing them and the most interesting discussion points actually always come up when the things that we are producing are at the build-up phase. All of the projects we produce are really sitespecific, they’re produced on location and have a build period that is essential. And actually, during this buildup period, we have a lot of architectural discussions with people related to the project. And this is also a mode of generating knowledge for us, because you don’t just discuss the final object, you discuss the whole process with people that normally don’t link a process to architecture. People forget that there is a process related to the build-up. We love to see the final object, but the moment of building it up, growing it, producing it, being involved in it, and having to make the decision of what is done by a machine, what is done by a human — all these things are in an exhibition because you have to do them. You have to produce an ecosystem that takes time, that takes love, that takes care. It allows us to expand a discussion on architecture on a lot of different levels. It challenges us because you have to be active and knowledgeable in a lot of different areas and fields. I think that’s also something that keeps us active and allows us to combine a lot of different types of knowledge from many different fields.

What would you see as an honest alternative to today’s constantly referred-to notions of ‘green,’ ‘sustainability,’ to avoid ‘greenwashing,’ in the context of architecture?

TD: MagicQueen is very dark, black, it’s not ugly, it’s not pretty, which actually led us to interesting discussions with a lot of visitors as well, not only professionals, who understand the ‘natural’ as something ‘green.’ And this is a cultural construct that we constantly deal with everyday. And it’s problematic. Personally, we don’t have a formula for getting out of this, but I think we have the opportunity and somehow the chance to critically engage with it. In reference to the Glasgow meeting that just happened, the COP26, there was a very interesting project that was initiated by the leader of the band, Massive Attack. They put up a platform to track all the advertisements, all these kinds of greenwashing. I think it was the first time that it had ever been done. To really understand the dimension of this issue, we should start to critically engage to make it evident first and then start to reconstruct our way back. interview from December 21, 2021 conducted by Lisa-Marie Androsch, Moritz Kuehn, Xavier Madden

DM: It’s a very difficult topic, because it’s very political. You can never say how to prevent greenwashing from happening. The moment you have it as a selling point, people use it. The moment that you put two, three trees on a roof and that gets you ‘in,’ then yes, of course you do it, these excuses we come up with how to make something sustainable, placing some trees here, producing some oxygen. But to actually allow to be created, this little bit of oxygen, this little bit of green, you end up using so much energy to do that, that you kind of eradicate whatever you promised before. The ground rule for everyone should be to build a very sustainable building, in the best way possible. It should not be a, plus point, anymore. By taking that out as a ‘plus point,’ you take it out as an excuse to defend something that might be not sustainable in its essence.

I think one big thing is also to discuss this idea of, do we need to build buildings that stay forever? We always want to design our buildings so they live on like the pyramids for thousands of years, but this is not our reality anymore.

What would you tell the next generation of architects, how could they approach design more holistically in order to work towards future ecologies?

TD: To think in terms of a more complex context for architecture — not complex for the sake of being complex, but because we cannot isolate our critical decisions from the context in which they are placed. Which brings us to the questions: Why do we need to build? What do we need to build? What does it mean to build now? So for me as a young architect, I think we should question the medium, expand the questions of architecture, and also find and create a context for the projects.

DM: There’s also the question of, what is architecture? We don’t seem to ask this question anymore. Like, what is architecture for you personally, now? It’s not just about what you have learned, but when you look at what is happening in the world, at the technology, the knowledge we have — what is architecture then? Just by asking these questions, starting a project like this, you get to a different point or different result.

This question of what architecture is nowadays requires agility on behalf of the architect. We need to be way more knowledgeable in a variety of fields, we need to see and almost hunt down things that could be interesting for us as architects. Going to other fields where we say, this is very interesting — this is knowledge that should come into architecture. This requires that we broaden our horizons to other fields, talk more with other fields and other disciplines, where we can really ask, what does it mean to do what we do? What’s the impact that I have when I do this and for whom am I building it?

I think the development of new approaches to architecture is a braver approach than going backwards and picking up topics that have already been discussed, because to just carry them over to our timeframe now might not be fitting anymore, we have evolved and we continuously evolve.

So we need to push this further and actually try to find new approaches to how we can do it and what it means for us to be architect, nowadays. And I think for that, you need to be brave and you must not be scared of failure and actually even find the beauty in this failure. In working with biological materials and new technologies, you will fail. But there’s a beauty in a failure that you really need to acknowledge and that makes you push ideas and thoughts further. And by doing that, you automatically adopt a more holistic approach because you go from one question to the next one. That’s a very potent way of doing architecture: if you don’t end up with a solution, but end up with more questions and more problems, because then you have created a machine of productivity where you say, okay, you’re trying to reach a final solution because you understand that the final solution simlpy lies in the production of a new, novel system. It’s not easy, but I think it’s fun and it requires a change in how we work and how we design.