Learning From the Arcades:

an analysis of the 19th-century arcades in Paris and a comparison of the typologies of in-person shopping spaces

Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London 2023

Dissertation Submmative Submission April Chen

Abstract

This essay will be analysing what contemporary shopping spaces can learn from the 19th century arcades to solve the current decline in in-person shopping spaces. The research on arcades will mainly be based on the Arcades Project by Walter Benjamin (Benjamin, 1982), which has a great number of documentaries and quotes related to arcades. The concept of the flâneur will be discussed in this essay to look at in-person shopping spaces and analyse into horizontal and vertical shopping spaces, and compare them based on the circulation and user experiences. The M&S Oxford Street will be used as an example to highlight such lessons and act as a solution for the decline of in-store shopping.

Image:

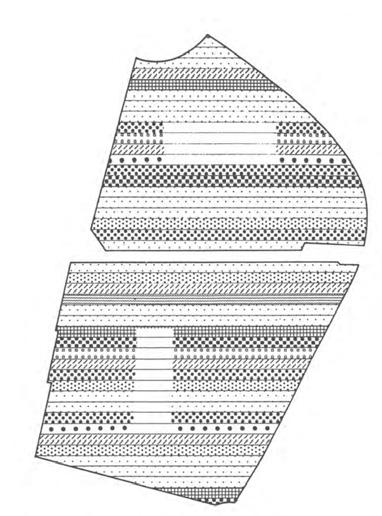

(image 1) ttg architects. (2018) ExistingBasementLevelPlan.ExistingGroundFloorLevel Plan.ExistingFirstFloorLevelPlan.M&S. Westminster City Council.

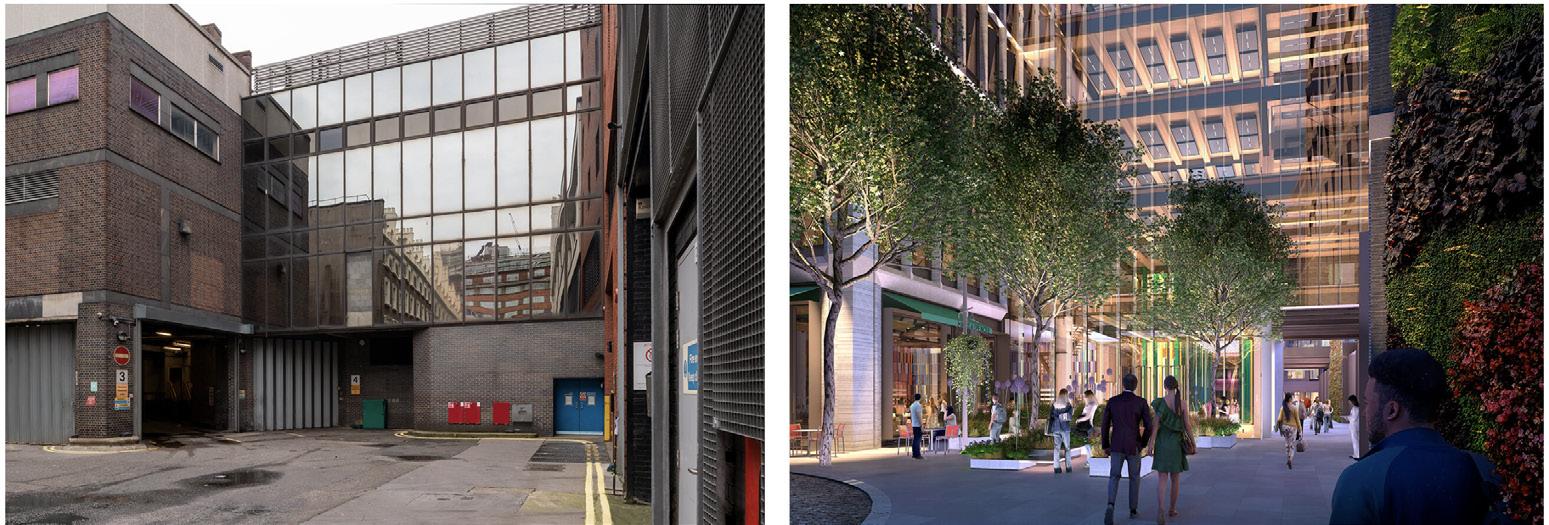

(image 2) Benjamin, W. (1982) PassageVéro-Dodat in theArcadesProject. Massachusetts, and London, England: Harvard University Press, pp.34.

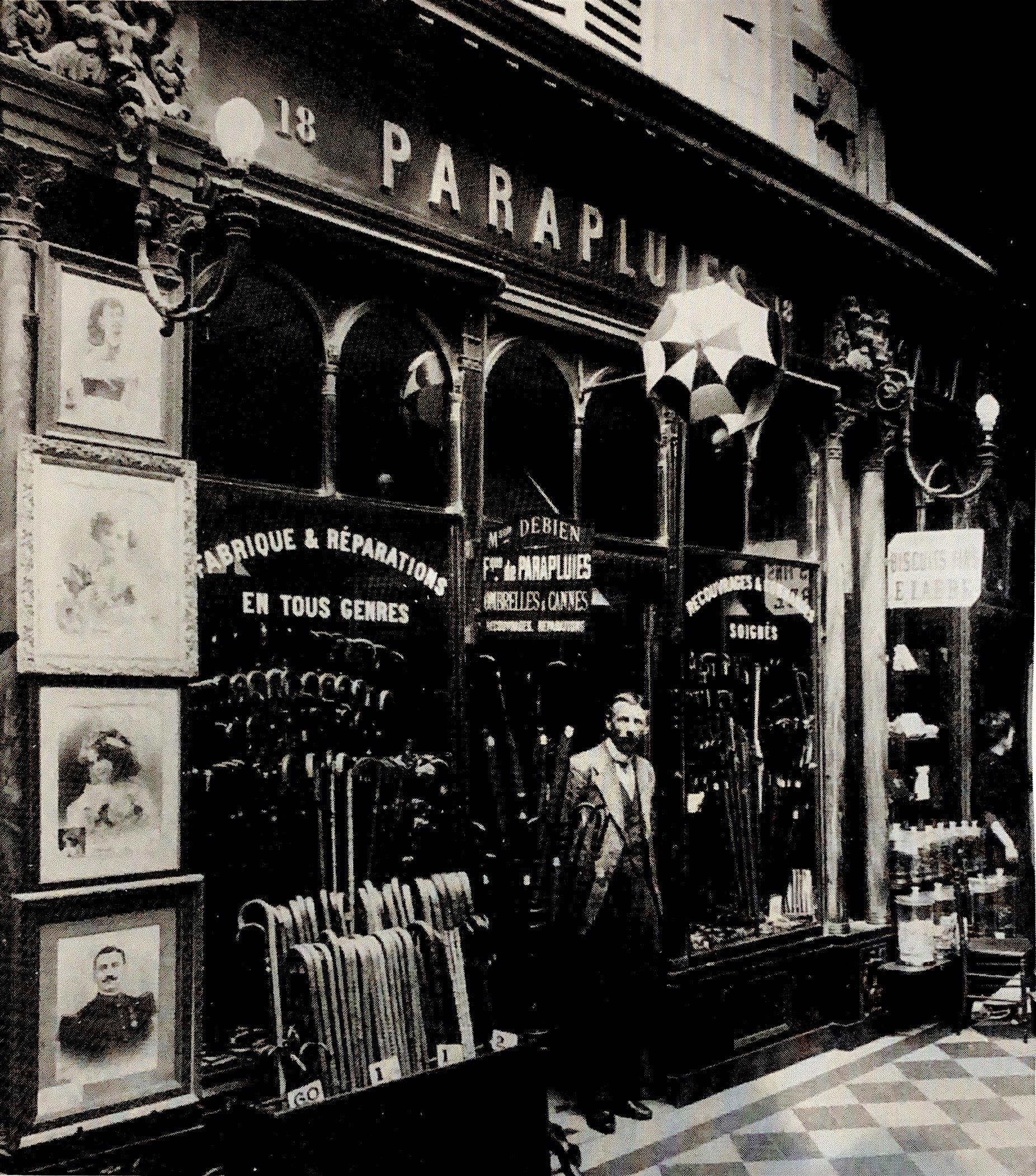

(image 3) Benjamin, W. (1982) Glassroofandirongirders,PassageVivienne.in the ArcadesProject.Massachusetts, and London, England: Harvard University Press, pp.35.

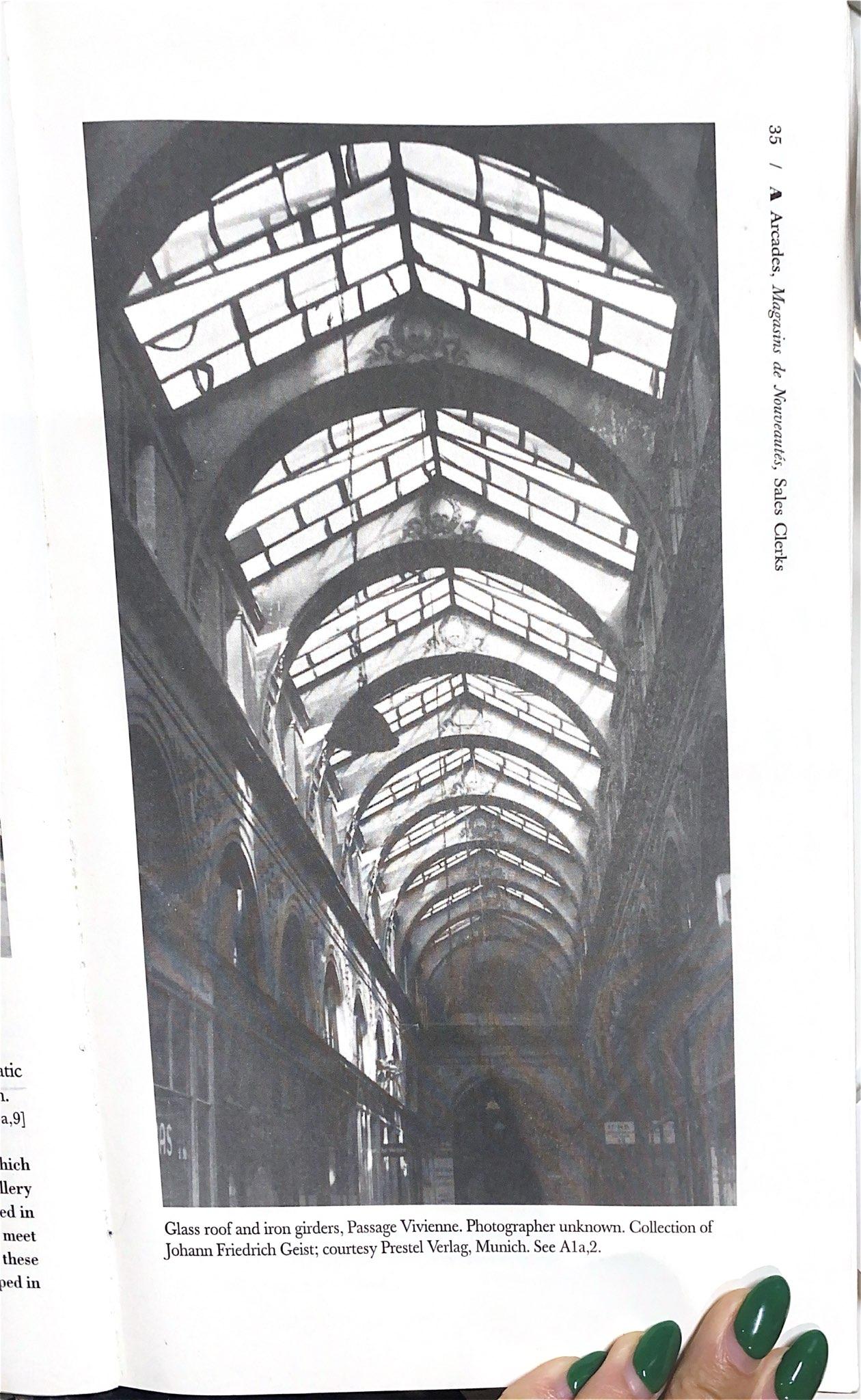

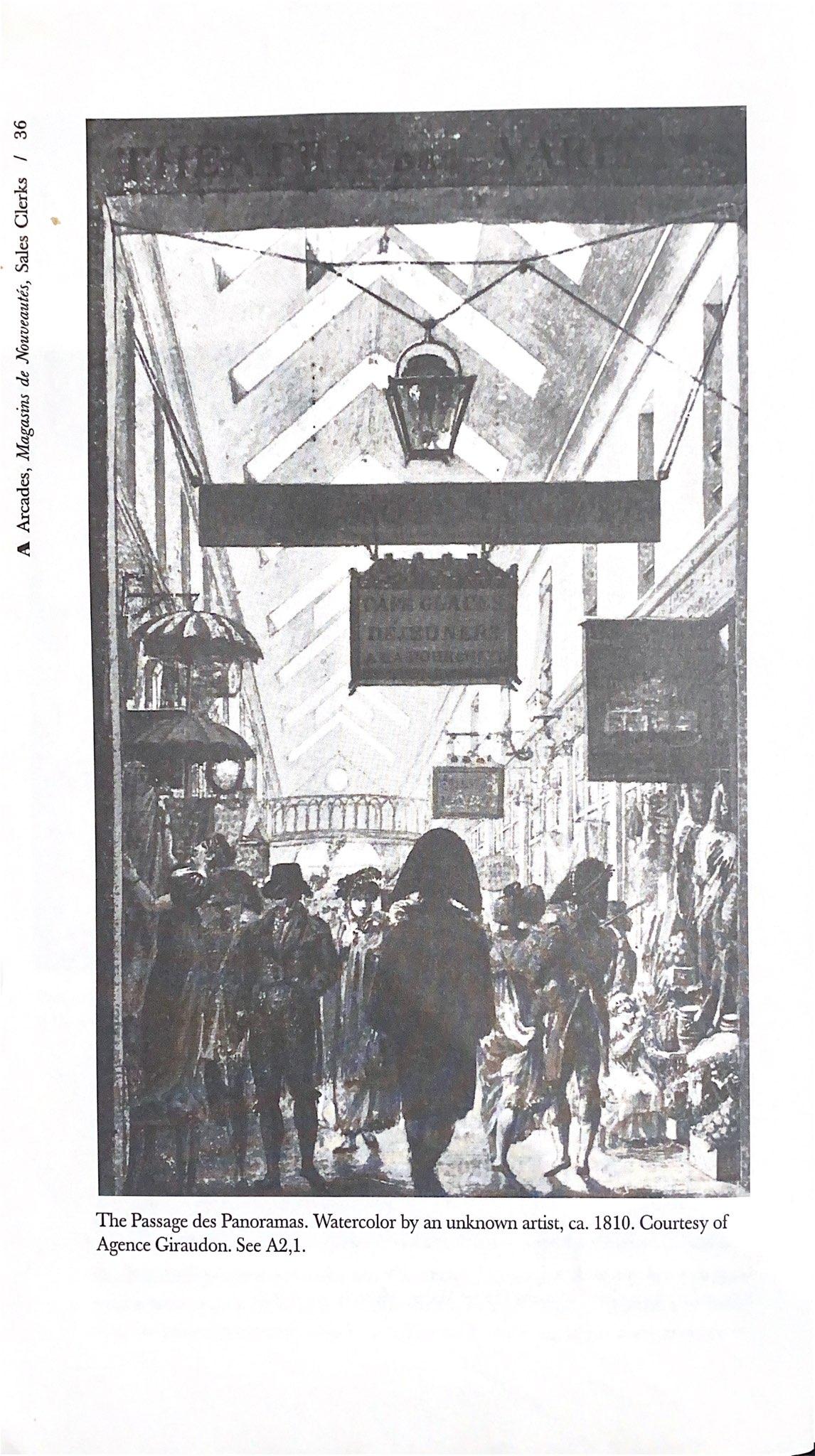

(image 4) Benjamin, W. (1982) PassagedePanoramas1810. in theArcadesProject. Massachusetts, and London, England: Harvard University Press, pp.36.

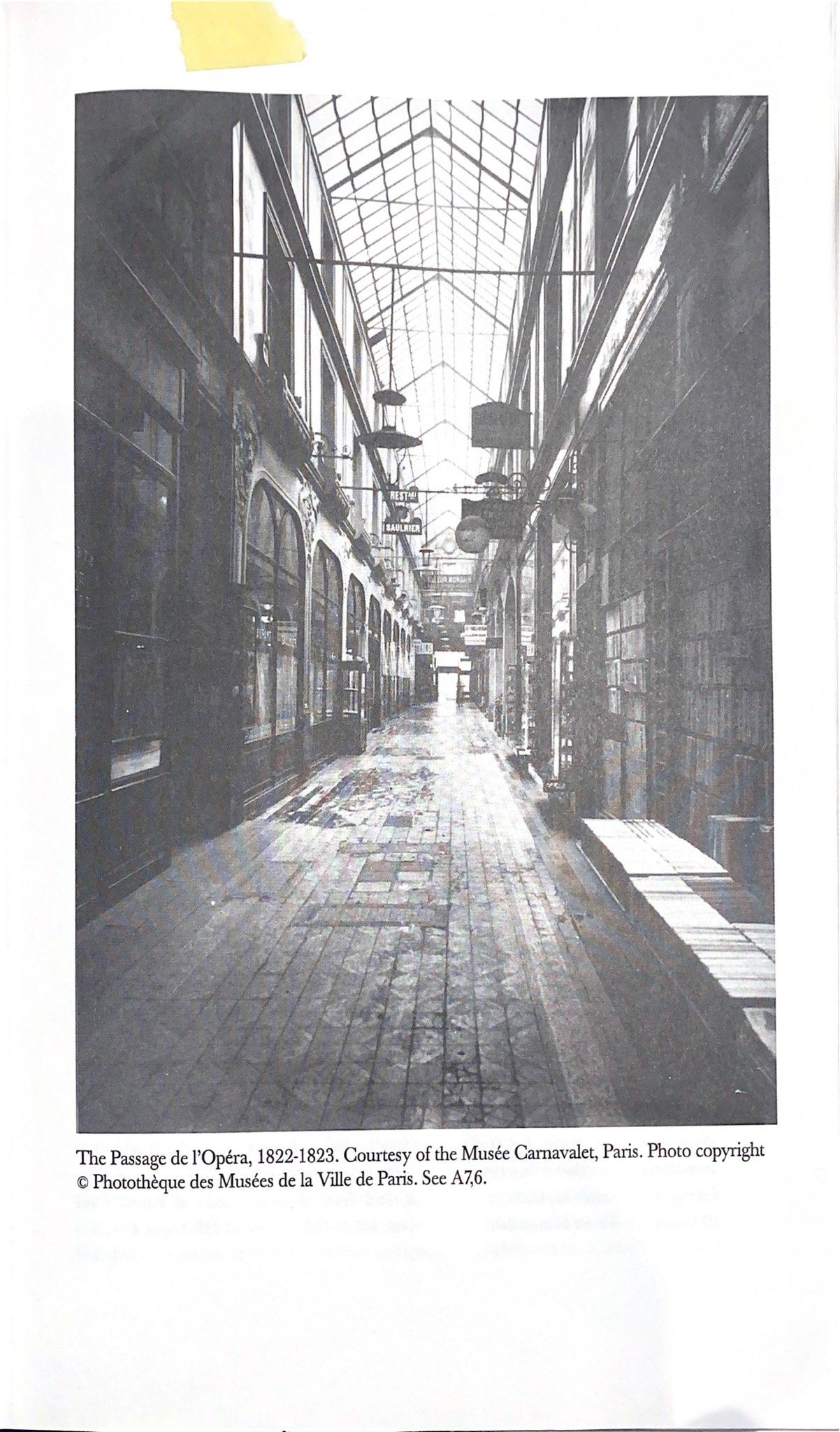

(image 5) Benjamin, W. (1982) ThePassagedel’Opera,1822-23.in theArcadesProject. Massachusetts, and London, England: Harvard University Press, pp.49.

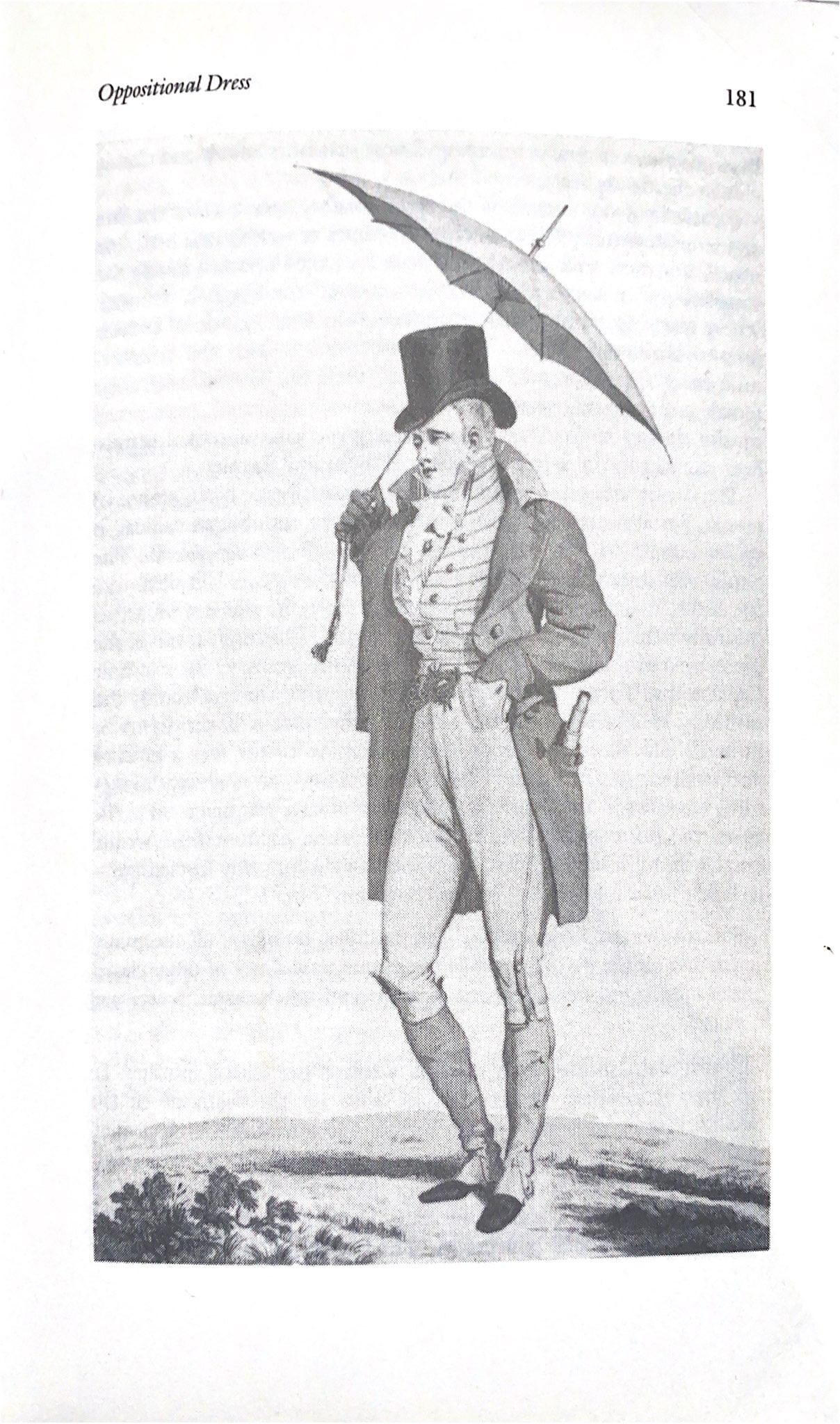

(image 6) Wilson, E. (2003) Flâneur. in Adorned in dreams: Fashion and modernity. London, London: I.B. Tauris &CO Ltd, pp.181.

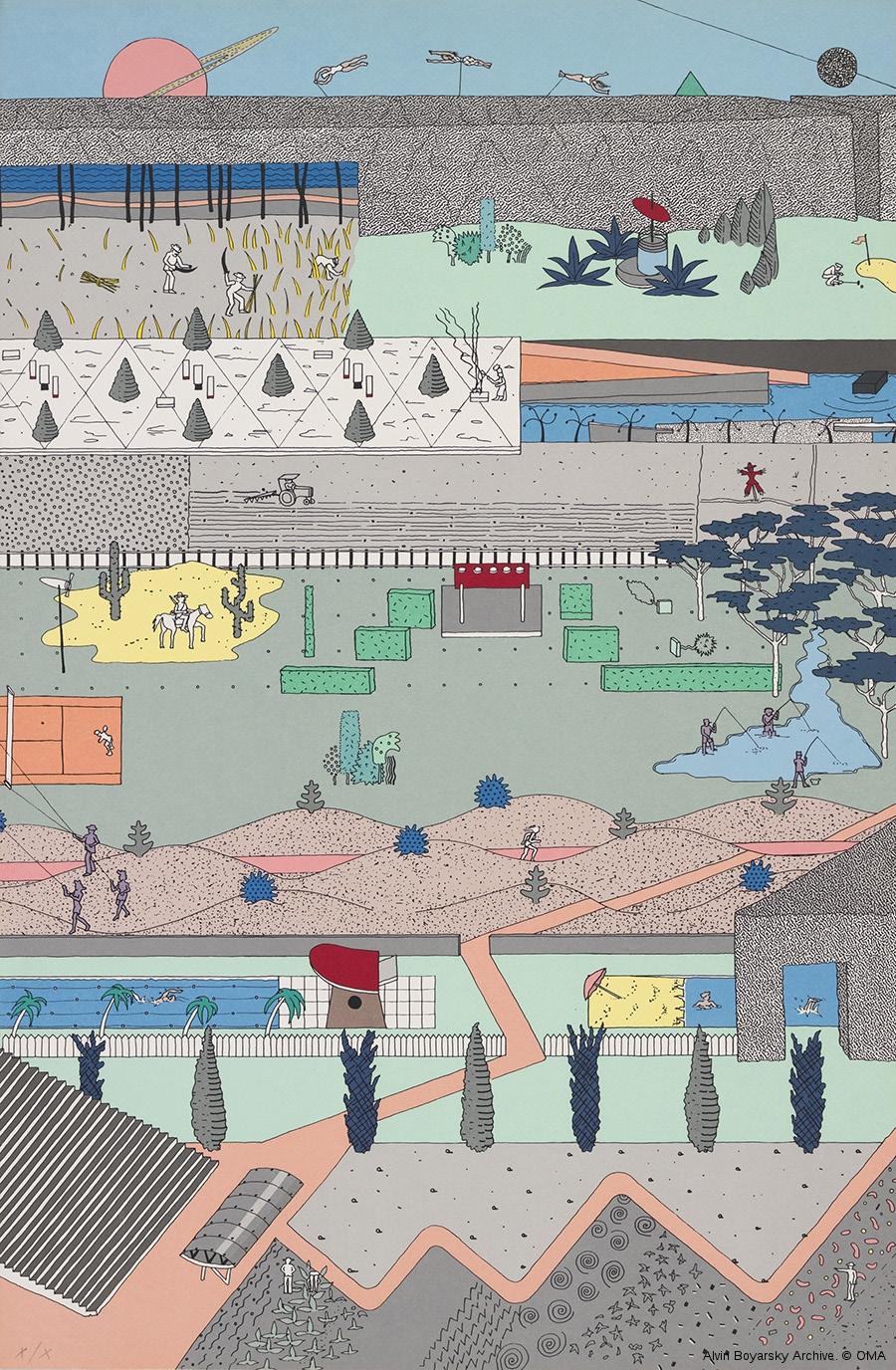

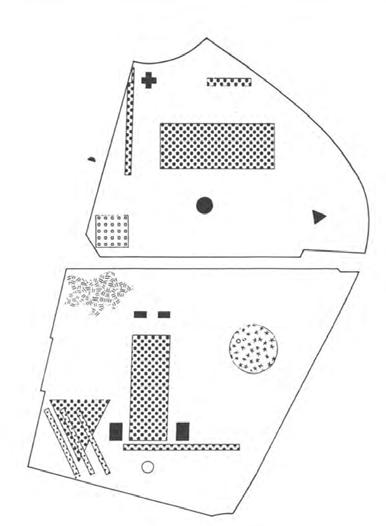

(image 7) Parc de la Villette: OMA Team (1985) ParcdelaVillettebyOMAforCityofParis. Available at: https://www.oma.com/projects/parc-de-la-villette (Accessed: December 8, 2022).

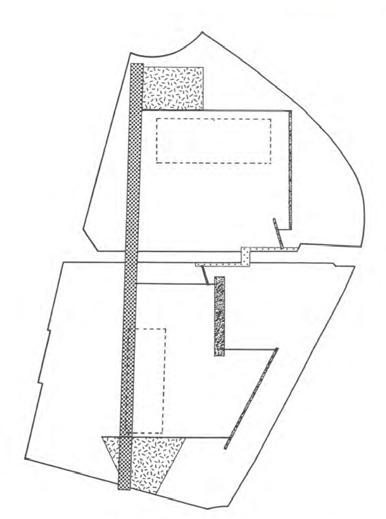

(image 8) Parc de la Villette: OMA Team (1985) ParcdelaVillette:thestrip,accessand circulation,thefinallayer.Available at: https://www.oma.com/projects/parc-de-la-villette (Accessed: December 8, 2022).

(image 9) Theorem 1909: Koolhaas, R. (2020) Theorem1909.1909 theorem, Architectural Context Part 7: Rem Koolhaas. Available at: https://geometrein. medium. com/architectural-context-part-7-rem-koolhaas-b9a2d20dde32 (Accessed: December 8, 2022).

(image 10) Koolhaas, R. (2020) DowntownathleticsclubbyStarrett&VanVleck. Architectural Context Part 7: Rem Koolhaas. Available at: https://geometrein.medium. com/architectural-context-part-7-rem-koolhaas-b9a2d20dde32 (Accessed: December 8, 2022).

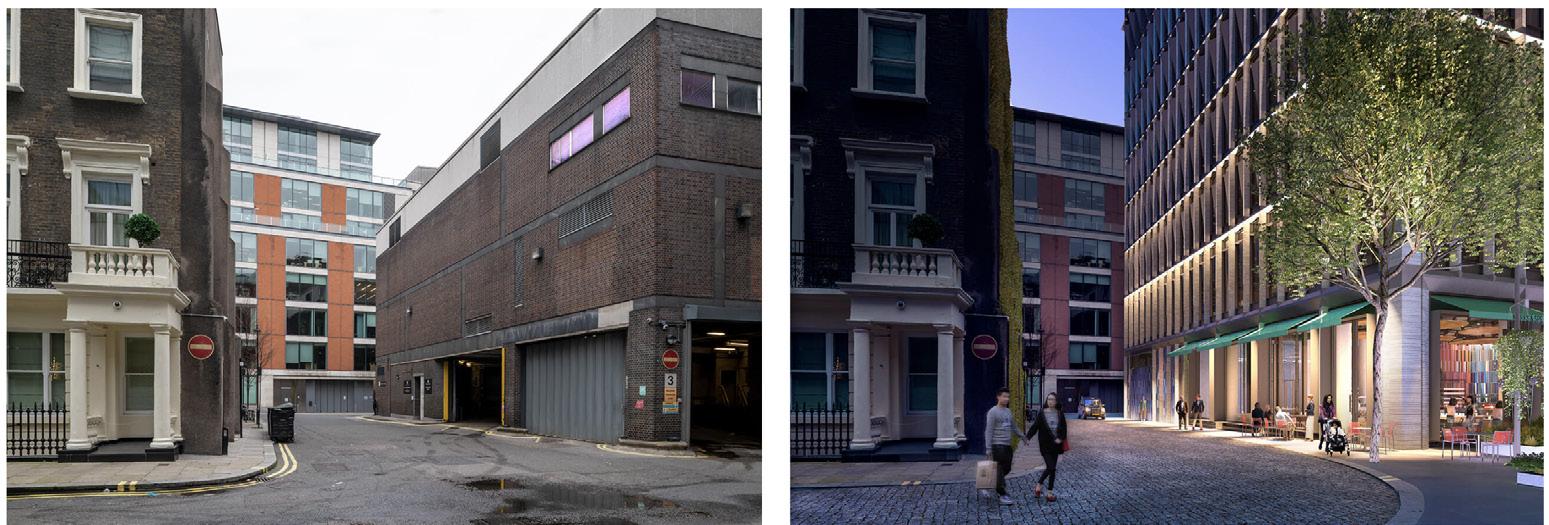

(image 11-18) Pilbrow & Partners. (2022) TRANSFORMEDPUBLICREALM.Virtual Exhibition. Marks & Spencers. Available at: https://458oxfordstreet. co.uk/virtualexhibition/ (Accessed: December 8, 2022).

(image 19) Pilbrow & Partners: (2022) M&Smasterplan.Virtual Exhibition. Marks & Spencers. Available at: https://458oxfordstreet. co.uk/virtual-exhibition/ (Accessed: December 8, 2022).

(image 20) Simitch, A. and Warke, V. (2019) 19thcenturyarcadesinParis.The Arcades in Paris, The News Lens. The language of architecture. Available at: https://www. thenewslens.com/article/123252/page2 (Accessed: March 23, 2023).

Cover Abstract Images Content page

1. Introduction

2. Decline of Contemporary In-Person Shopping Spaces

3. The 19th Century Arcades

3.1. Arcades created a sense of community

3.2. Arcades were advanced in material and technology

3.3. Arcades provide immersive shopping experiences

4. Reflections

5. Use the Concept of Flâneur and the Experience to Analyse Shopping Spaces

5.1.1 Flâneur and horizontal experience

5.1.2 The the Horizontal Experience with the High Street and the Arcade

5.2.1 Flâneur and the Vertical Experience

5.2.2 Discuss the Vertical Experience with the Department Store

5.3 Compare the Horizontal Shopping Space and the Vertical Shopping Space

6. A Contemporary Application of Using the Concept of Arcades and Flâneur - M&S oxford street

7. Conclusion Reference

1. Introduction

Currently, in-person shopping spaces are facing a major decline. This is due to several factors ranging from the recent global pandemic to the ever-increasing rise of online shopping behaviour. As a result, companies are reflecting on the design of their spaces with the goal of attracting the masses back to their stores. Some of them, such as Marks and Spencer (M&S), which will be used as an example in this dissertation, are drawing inspiration from the past for their redesigns.

The main focus of this dissertation is an analysis of the ancestor of the department store, the 19th-century arcades in Paris, which were successful in their day. The research on arcades will mainly be based on the Arcades Project by Walter Benjamin (Benjamin, 1982), which has a great number of documentaries and quotes related to arcades. The concept discussed in the arcades is the figure of the Flâneur, the main user of the arcades, who strolled along them around the city and which has formed a concept that highlights the user experience, has been taken into consideration in architectural practices.

The concept of the flâneur will also be used to analyse both horizontal and vertical shopping spaces. The horizontal experience in shopping spaces is just like the arcades, and the Parc de la Villette by OMA will be used as a precedent to discuss the experience and circulation. The vertical experience, on the other hand, is similar to department stores, having the experiences layered on top of one another. The Downtown Athletics Club by Starrett & Van Vle will be used to discuss the experience, circulation and efficiency. After comparing the horizontal and vertical experiences, it will be concluded that the horizontal shopping space can allow users to experience more and stay longer, eventually leading to higher sales compared to the vertical space.

By analysing the layout of the arcades and the concept of the flâneur, it will be possible to identify several lessons that contemporary shopping spaces could learn from the past so they can attract customers back to their stores, and ultimately increase their in-person shopping sales. The example of M&S Oxford Street will be used to highlight such lessons and act as a solution for the decline of in-store shopping. The proposal for the redesign of M&S Oxford Street is yet to be approved and built, but it clearly shows what the current situation of in-person shopping spaces needs without being affected by external voices. The current building is facing a decline, therefore their recent proposal is to reduce the size of the retail area and have offices to rent.

The analysis of M&S’s proposal will focus on three points: it is recreating a sense of community by creating space to engage people and connect the two main roads; it is using advanced technology and materials to reuse the old building’s material, making it more sustainable, and also visually appealing by creating a modern atmosphere; it is creating an immersive shopping experience by connecting the neighbourhood with a walkway that will allow people to stroll from one place to another, thus creating a space that has ‘everything.’

Ultimately, this dissertation aims to answer the question:

What can contemporary shopping spaces learn from the 19th-century flâneur and arcades?

To answer this question, the decline of contemporary in-person shopping spaces will be discussed. Following this, a detailed description of the 19th-century arcades will be given, including the sense of community they created, the advanced technology and materials that were used to build them, and the immersive shopping experiences they provided their customers. The concept of the flâneur will then be used to analyse both horizontal and vertical shopping spaces followed by a discussion on which layout is more successful in attracting customers. Finally, the lessons that can be learned from the 19th-century arcades and how they can be applied will be analysed based on the proposal of M&S Oxford Street.

2. Decline of Contemporary In-Person Shopping Spaces

“Not only is shopping melting into everything, but everything is melting into shopping (Leong et al., 2001, p.129).” The behaviour of people has a direct impact on how shopping spaces are formed. Shopping has become a part of our basic way of life, the most significant and fundamental development to form modern life. It is the standard of the global market economy and the most up-to-date. Public spaces such as institutions, hospitals, or churches, whose need is to fulfil users’ basic needs in the city, are different to shopping spaces, which require constant reform, reshaping, and reformulating to sustain any micro changes within the society Koolhaas (Leong et al., 2001, p.131).

In-person shopping spaces are where customers buy the items they desire in a physical space full of product displays, such as malls, individual shops, and department stores. These spaces are built so that people can buy goods in one place, and putting products alongside one another can increase the chance of customers buying what they see and eventually increase sales. However, in-store shopping has been facing a decline, the main cause of which can be identified as a change in shopping behaviour. For example, online shopping platforms such as Amazon have a wide range of products at various prices and different brands that can be chosen at the click of a button. Additionally, during the Covid-19 pandemic, people were restricted from going outside, so they could only do their shopping online to avoid spreading the virus through interaction with others.

The department store, Marks & Spencer (M&S) on Oxford street, is a good example that shows the decline of in-store shopping and enables us to see how a company can earn more profit based on design decisions. The M&S flagship store is at the junction of Oxford Street and Orchard Street, right beside Selfridges. Currently, M&S is demolishing its Orchard House, Neale House and Orchard Street House buildings. It is a heritage site in London and is one of the city’s representative department stores (Marks & Spencer, 2022)

M&S claims that the current layout of the building, with many columns and levels of changes, was affecting the circulation of the shopping experience. The non-opened frontages created a disconnection between the store and the street (Marks & Spencer, 2022). Their proposal is very controversial due to the issue of sustainability as they are demolishing instead of refurbishing the building. There is also the issue of demolishing a historic building, which is a heritage site in London. The new proposal shows that the current M&S Marble Arch building is not making money from in-store shopping but instead from online shopping. This is because they are proposing to put the entire existing M&S retail on the ground, lower ground and first floor, thus decreasing the size of the retail shops. They are also proposing to have a large grocery store on the lower ground level, which is not affected too much by online shopping due to the nature of selling fresh food (e.g. short expiration dates and people’s necessity to have fresh groceries every few days) (Marks & Spencers, 2022). In the proposal, the first to the seventh floor will be converted into offices. The fact that they are proposing to build office spaces shows that renting office space in central London could make more profit than selling goods in the shopping space itself. This case is a clear example that shows the situation of shopping spaces in 2022.

3. The 19th Century Arcades

Arcades were the most popular shopping spaces in 19th-century Paris and are considered the ancestors of department stores. The arcades will be analysed in three parts in this chapter, and whether they are an inspiration for the current decline of in-person shopping spaces will be discussed.

Arcades were naturally developed after boulevards using the space between two buildings. Boulevards separated buildings into blocks and vehicles could move freely in the area. However, arcades were pedestrian-only, internally covered streets within blocks that connected boulevards. Arcades were places for people to walk safely, meet and shop. They were places for the community, places that were inside but also outside, places that had advanced technology and were luxurious, and places to have an immersive shopping experience.

3.1. Arcades created a sense of community

Arcades were naturally developed to appear after boulevards, and the covered streets expanded from boulevards between buildings. Arcades were linear architecture connecting two or more communities and were a place for people, especially flâneurs, which was the name given to pedestrians that strolled along these walkways, to socialise and shop. In the arcades, flâneurs were seeing and wanted to be seen, were meeting and wanted to be met. Arcades were not only a place to shop but also a sense of community was created there.

Passagedel’Opera(1823), as an example, was located beside the Opera on the Rue Le Peletier, and the opening of the Opera in 1821 brought this passage into vogue (Benjamin, 1982, p.32) Before the development of arcades, the roads were full of carriages, especially when there was a show at the Opera. It was dangerous to be a pedestrian at that time. The development of arcades provided a pedestrian-only street that used the dead space created by the buildings and could act as a shortcut to the boulevard. Pedestrians’ safety was ensured as there were no vehicles. Arcades were formed as a gathering space for people between communities, moreover, they became a community itself. Likewise, PassageVéro-Dodat(1823) was an immense development that owed its name to two rich pork butchers, Messieurs Véro and Dodat. This arcade was described as “alovelyworkofartframedbytwoneighbourhoods”at the time (Benjamin, 1982, p.33). This clearly shows that Passage Vero-Dodat acted as a bridge between the two neighbourhoods, which were connected by two roads, thus creating a community.

Arcades not only provided a place for flâneurs to shop in the individual stores on the ground floor but most importantly, they provided a place to gather and further form a community. Arcades created a sense of community as Walter Benjamin (1982, p.446) mentioned in the Arcade Project, “in the arcade, everything can be shared: gossip, insights, sorrows. It is as if the arcade were an immense collective chamber.” Many people used arcades as a gathering space, such as the young surrealists, who met in the café to exchange their ideas and go on their daily strolls. The famous French surrealist poet Louis Aragon, devoted a novel to pursue his appreciation towards Passage de l’Opera. (Aragon, 1994) “The father of Surrealism was Dada; its mother was an Arcade,” states Benjamin (1982, p. 82). From the quote, the mother of Surrealism was an arcade, and because arcades were a space for surrealists to gather, they also served as an inspiration to observe people’s behaviour. Arcades physically connected two neighbourhoods to provide a space for people to gather and also formed a space that allowed people to explore and be explored, therefore creating a community.

3.2. Arcades were advanced in material and technology

“ForsomeoneenteringthePassagedesPanoramasin1817,thesirensofgaslight wouldbesingingtohimononeside,whileoil-lampodalisquesofferedenticements fromtheother.Withthekindlingofelectriclights,theirreproachableglowwas extinguishedinthesegalleries,whichsuddenlybecamemoredifficulttofind-which wroughtablackmagicatentranceways,andwhichlookedwithinthemselvesoutof blindwindows.”-WalterBenjamin.(Benjamin,1982.p.564)

Arcades were the “industry luxury” and used materials that were advanced for the time (Benjamin, 1982, p.3). They were covered with a steel-framed glass roof, allowing natural sunlight to come in during the day. The covered space created a pedestrian rain shelter or winter gardens from the cold weather. Iron and glass were modern and luxurious in the 19th century, same as the marble-panelled corridors and the gas lighting extending through whole blocks of buildings (Schiermer, 2019). The range of architectural applications for the steel-framed glass roof and gaslighting was advanced for the time. The common use of glass as a building material would only come to the foreground a hundred years later (Weston, 2011). Gaslighting was the latest technology and was expensive. By using this novel product in the arcades, it brought a luxurious atmosphere to them. The marble flooring and decoration inside also show that the arcades provided people with a palatial interior and spatial experience.

Arcades were advanced in material and technology, which created a luxurious spatial atmosphere. The patrons were higher-class women or flâneurs, who were higher-class male strollers, both of whom had the money to shop and spend time in these spaces. This demonstrates that having an advanced design in the shopping space brings the user a novel atmosphere and attracts customers.

3.3. Arcades provide immersive shopping experiences

Arcades were within the blocks between buildings connecting boulevards in the whole of Paris. They were full of shops, cafés, and restaurants. Arcades could be seen as a typology to build markets in the city, and to expand the pleasure of consumption spread over the city by entering them. The arcades were a type of building but also an interior, that merged with the street, blurring the boundary. They were connected by buildings but also connected by people. People strolled from one arcade to the other. They spread throughout the city and merged with the city. Arcades were places with shops, but more importantly, they were places of atmosphere, blending, and immersion.

“Thecafesarefilled Withgourmets,withsmokers; Thetheatersarepacked Withcheerfulspectators. Thearcadesareswarming Withgawkers,withenthusiasts, Andpickpocketswriggle Behindtheflâneurs”

-WalterBenjamin.

(Benjamin,1982.p.43)

The people in the arcades were not only there to shop, but also to encounter. People were there for the atmosphere, for the experience of the spaces and people. The arcades went beyond simply purchasing goods. The space provided an immersive shopping experience which had various objectives that combined all the leisure activities for people to enjoy, and the atmosphere of strolling and experiencing was highlighted by the flâneurs. The arcades were considered as a city in miniature, which shows that they had everything in one place.

As Alfred de Musset observed, Arcades were mainly luxury shops or places for leisure activities. “On Sundays, one went en masse to the Panoramas or else to the boulevards” (Benjamin, 1982, p.41). Walter Benjamin’s list of the shops in Passage de Panoramas included: “Restaurant Véron, reading room, music shop, Marquis (chocolate shop), wine merchants, hosier, haberdashers, tailors, bootmakers, hosiers, bookshops, caricaturist, Théâtre des Variétés” (Benjamin, 1982, p.37). The luxurious shops targeted those with a higher social status and the financial ability to afford it. The retail business grew in the arcades because respectful women were willing to shop there. They were people who were seen as icons and acted as natural advertisements for the merchants. We can see that many shops in Passage de Panoramas were respectful-women-focused. Imagine a day of theirs: they went to their private tailor, had their boots made, purchased tailoring material in haberdashers, and had a cup of coffee while they rested. In the afternoon, they continued getting their portrait drawn by the caricaturist who had yet not finished. Before they went home, they could get some chocolate in Marquis and wine at the wine merchants. Via imaging based on the shops in Passage de Panoramas, one of the Paris arcades, we can see that at the time, there were around 300 arcades before Haussmann’s renovation of Paris (Benjamin, 1982, p.23). Based on the scale of the mini world within each arcade, we can start to see how arcades formed Paris as a whole.

4. Reflections

Based on the analysis of the arcades, the following chapter will reflect on the architectural and social elements from which contemporary shopping spaces could learn.

As mentioned, arcades created a sense of community, which is meaningful for in-person spaces as we need to create more encounters for people, build connections between them, and have a physical community that is formed by people. This physical connection created by people through the space is irreplaceable when it comes to online shopping, thus highlighting this would bring people back to in-person shopping spaces. When designing these spaces, besides taking into account the importance of raising sales to earn more profit, shopping spaces should be considered civic spaces, which are owned by people, similar to what the arcades were doing. Instead of thinking about how to fit more shops in a department store on each floor, we could also consider people as the focal point. For example, we could try to create a better layout for people to encounter, meet, stay in the space, and eventually create a sense of community in the shopping space. Having a community in the shopping space, which is the first step we learnt from the arcades, could bring back the masses to the in-person space, and it is the most important part of the solution for in-person shopping.

Furthermore, modern shopping spaces need to be advanced in materials and technology as they should be constantly reshaped and reformed to be the most up-to-date and to fit current shopping habits. Today, we can learn from the arcades by using advanced technology in shopping spaces to enhance the shopping experience for customers, and by creating spaces that are efficient, sustainable, and visually appealing. Advanced technology can increase the efficiency of building shopping spaces. The faster it takes to complete construction, the more money is saved. It can also reach the goal of becoming sustainable by using engineering technology to calculate and minimise the use of unsustainable material; having an advanced glass facade or roof that allows natural sunlight to go into the space to reduce artificial lighting in the commercial space, but also reduce the thermal energy from heating the space; creating a better thermal envelope to protect the internal climate from being affected from the outside, therefore reducing energy, etc. Additionally, the advanced technology could be used to create a visually appealing space for the customers which has the most direct impact on bringing people back to in-person spaces. Having the newest materials could provide the space with a modern atmosphere that could visually attract people due to its modernity and luxuriousness. As the shopping industry is about constantly having the newest products, having a shopping space with the most advanced technology and materials would give a feeling of modernity, and would ultimately appeal to customers.

Lastly, providing an immersive shopping experience for customers would allow people to not only see the shopping space as a place to buy goods, but also to enjoy the atmosphere it creates, and allow the user to blend with the physical experience. The flâneurs, who were the main users of the arcades, were higher-class white males who were taking a stroll. Also, the luxurious interior of the arcades was to attract higher-class customers. In the contemporary case, the shopping space should be for everyone, so it should be inclusive. People who have a different class, gender, or race to that of the flâneurs, may not experience the same anonymity or safety as they once did. However, the concept of flâneurs strolling along the arcades is a worthwhile-learning element for architectural practice as it highlights the experience of users. Therefore, contemporary shopping spaces should be designed for everyone to have a sense of community, and to experience and shop safely.

5. Use the Concept of Flâneur and the Experience to analyse Shopping Spaces

The figure of the flâneur, which was discovered in the 19th-century arcades, was seen as an important awareness of experience in architectural practice. Flâneur was later seen as a tool to explore places and ways of travelling and used to reflect on the relationship between people and spaces. The purpose of discussing flâneurs and their experience is to apply this concept to contemporary shopping spaces and further analyse different types of shopping spaces with regard to experience and circulation. This chapter will discuss the concept through two conceptual precedents and analyse in detail the comparison with in-store shopping spaces. The conceptual experiences will be separated into the horizontal manner and the vertical manner. The horizontal experience will be exemplified by Parc de la Villette by OMA, and this concept will be taken further by looking at high streets and arcades in depth. The vertical experience will be exemplified in the Downtown Athletics Club and the experience of users within it. This concept will be applied to the analysis of department stores.

5.1.1 Flâneur and horizontal experience

Flâneur is considered to be a crucial element in enhancing the experience of users for architectural practice, especially in the modernist movement. Parc de la Villette, by OMA in 1982, was a project to design a park for the City of Paris. They proposed a conceptual park, as they said, a “provisional enumeration” of desirable ingredients (OMA, 1985). In the proposal, they put different layers of activities on the site in a striped manner, side by side, and created a linear path to cross all the striped areas with different activities. This proposal was tactically efficient and explosive to offer stable experiences throughout the path (OMA, 1985).

The initial hypothesis was to create the park as a dense forest of social instruments. The park was too small, so they proposed it as a concept to be taken over on a larger scale in the future. They put the original hypothesis on site, shown as strips, and used access and circulation of the journey in the park (OMA, 1985). The main journey was the path perpendicular to strips that could cross the entire site vertically to experience every activity at once. The final layer was to put down large-scale attractions in the park that were surreal in form but attracted people’s eyes.

The Strips

5.1.2 The the Horizontal Experience with the High Street and the Arcade

Flâneurs in the 19th-century arcades strongly inspired the concept, and we can see they enhanced the ideology of aesthetic experience through the path created in an urban realm. The proposal itself is a method to combine architectural specificity with programmatic indeterminacy (OMA, 1985). This concept will be used as a lens to look at high streets and arcades as shopping spaces. The architectural specificity of highstreet and arcades is limited to the ground floor of the building which has a facade facing the street. The programmatic indeterminacy of high streets and arcades are, at least most of them unplanned, due to the individual owners of each ground floor shop, who decide on the location of their own shops. The layout of the shops on a high street are firstly a cluster that gathers all similar shops in the same place such as clothing, food, cameras, fabrics, and so on. This created a special type of high street to attract customers with the same needs to boost each other’s visibility and therefore boost sales. Another totally different type of high street is where each shop owner is aware of the location of similar types of shops, so when they are deciding on their location, they keep a distance to avoid dividing up existing customers with other shops, which could reduce sales for both. Therefore they can boost sales by developing potential customers that do not already have a usual place to go.

Using the concept of Flâneur to look at high streets and arcades, the relationship between people and the spaces could be seen in the same way as Parc de la Villette, with each shop representing a strip of different experiences, and the street representing the walkway crossing all the experiences. The high street and the arcade could be seen as an existing example of a dense forest of social instruments which forced the user to go through all the experiences, or in this case, all the shops linearly. If the user wished to go from shop A to shop E, they would have to go through every shop in between. Therefore, shops B, C and D might have had a higher chance to make a sale as the longer the customers spent in a shop, the higher the possibility of a sale (Leong and Weiss, 2001, p.108)