40 AMAG

INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURE

INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURE

Since 2023, AMAG international architecture is out together with AMAG PT portuguese architecture. AMAG SUBSCRIPTIONS grants the OFFER of AMAG PT free of charges, 20% DISCOUNT at all titles from the LONG and the POCKET books COLLECTIONS and EXCLUSIVE PROMOTIONS.

LONG BOOKS brings together a unique selection of projects that establish new paradigms in architecture. With a contemporary conceptual graphic language, the 1000 numbered copies of each title document works with different scales and formal contexts that extend the boundaries of architectural expression. Each title features one single work, from one single studio.

4

4

POCKET BOOKS are an assembly of small books that compiles theoretical texts by different architects. Writings that reflect different areas of interest and performance, in a timeless book collection.

AMAG PUBLISHER is an international publisher that carefully conceive, develop, and publishes books and objects directed related to architecture and design. Mainly in 3 different series: MAGAZINE, BOOKS and OBJETS, with a deeply conceptual approach, each collection represents a challenge and a new opportunity for the production of unique and significant books, meeting the highest quality standards and a differentiating design, absent from standard trends, representing significant values and content to inspire each reader and client.

AMAG MAGAZINE (AMAG) is an architecture technical magazine, in print since December 2011, published from March 2023, quarterly and concomitantly, in two series: AMAG (international architecture) and AMAG PT (portuguese architecture).

AMAG PT 10 MENOS É MAIS ARQUITECTOS

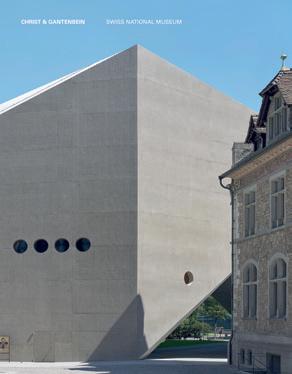

AMAG 38 AFF ARCHITEKTEN AMAG PT 09 RICARDO CARVALHO ARQUITETOS AMAG 37 CHRIST & GANTENBEIN AMAG PT 08 CAMILO REBELO

AMAG 36 SIMON PENDALL TAYLOR AND HINDS

VOKES AND PETERS

AMAG PT 07 NUNO MELO SOUSA

AMAG 35 LCLA MANTHEY KULA

SANDEN+HODNEKVAM

AMAG PT 06 SIA ARQUITECTURA AMAG 34 AMAA ASSOCIATES ARCHITECTURE STUDIO WOK

AMAG PT 05 AURORA ARQUITECTOS

AMAG 33 MILLER & MARANTA AMAG 32 ATELIER ORDINAIRE EGR ATELIER

JEAN-CHRISTOPH

William

LB 07 DAVID ADJAYE Winter Park Library & Events Center

LB 06 ANDRÉ CAMPOS | JOANA MENDES PEDRO GUEDES DE OLIVEIRA fábrica em barcelos

LB 05 ANDRÉ CAMPOS | JOANA MENDES centro coordenador de transportes

LB 04 CARVALHO ARAÚJO casa na caniçada

LB 03 DAVID ADJAYE the webster

LB 02 NICHOLAS BURNS chapel and meditation room

LB 01 DAVID ADJAYE mole house

POCKET BOOKS

PB 07 ÁLVARO SIZA UNBUILT WORKS | NOTES ON ARCHITECTURE

PB 06 IN CLASS WITH TÁVORA TEACHING AND LEARNING (LIVING) TODAY

PB 05 PAULO DAVID | THE LESSON OF THE CONTINUITY

PB 04 DOING GOOD FAZER BEM DOING WELL

PB 03 NOTES ON ARCHITECTURE | BUILDING AROUND ARCHITECTURE FRANCESCO VENEZIA OUTSIDE THE MAINSTREAM

PB 02 FORM, STRUCTURE, SPACE NOTES ON THE LUIGI MORETTI’S ARCHITECTURAL THEORY

PB 01 EDUARDO SOUTO DE MOURA LEARNING FROM HISTORY, DESIGNING INTO HISTORY

D.151.4 Armchair

D.151.4 Armchair

MOLTENI&C LISBOA FLAGSHIP STORE

AV. DA LIBERDADE, 254, 1250-143, LISBOA

MOLTENI&C LISBOA FLAGSHIP STORE

T +351 926 030 765 BY SERVÀNT

AV. DA LIBERDADE, 254, 1250-143, LISBOA

T +351 926 030 765 BY SERVÀNT

MOLTENI&C PORTO BOUTIQUE

RUA DA VENEZUELA, 245, 4150-744, PORTO

MOLTENI&C PORTO BOUTIQUE

T +351 229 421 285 BY STUDIO NONNO

RUA DA VENEZUELA, 245, 4150-744, PORTO

T +351 229 421 285 BY STUDIO NONNO

Nestled at the base of a rugged rockside in Henderson, Nevada, Module One is the personal residence of architect Daniel Joseph Chenin, FAIA. Designed as a study in restraint and resilience, the home draws its power from material honesty and a deep-rooted connection to its desert terrain.

Constructed from stacked concrete block and blackened steel, the

structure mirrors the geological formations that surround it, anchoring into the land with quiet force. To achieve a sense of both enclosure and transparency, Titoni Window Steel Systems were selected for their precision craftsmanship and minimal profiles. The slim sightlines allow the architecture to remain the visual focus while enhancing the fluidity between interior and exterior. Their raw steel finish

harmonizes with the material palette, reflecting the same elemental rigor that defines the home itself.

More than a residence, Module One is a personal manifesto, a place where architecture becomes a lived philosophy, shaped by climate, light, and landscape. Rooted in place, it stands in elemental dialogue with its environment: enduring, quiet, and undeniably of the desert.

These are some of the adjectives that define the wellness space at Herdade

designed by the

and with exclusive facial treatments in the

by the

THOUGHTS FROM THE EDITOR

by Ana Leal

UKIYO-E

by José Manuel Pedreirinho

by Mark Lee

HOUSE IN A FOREST

HOUSE IN GOTANDA

APARTMENT IN NERIMA

PILOTIS IN A FOREST HOUSE IN KOMAZAWA

HOUSE IN KYODO

ROW HOUSE IN AGEO APARTMENT IN OKACHIMACHI YOSHINO CEDAR HOUSE

Ana Leal is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of AMAG magazine and AMAG publisher since 2011.

She graduated in architecture in Porto, Portugal and has been dedicating her professional journey to editorial projects on the topic of architecture since 2006.

Ana Leal was also the co-founder of DARCO magazine in 2006 and AICO Architecture International Congress at Oporto in 2010 and 2018.

このタイトルは長谷川豪の厳選された主要作品を収録し、彼の建 築を空間的、文化的、そして詩的な側面で捉えている。戸建住宅か ら集合住宅、日本の田舎からヨーロッパの風景まで、この選集は場 所、身体、記憶への深い関与を明らかにしている。

「森のなかの住宅」や「森のピロティ」、「駒沢の住宅」の作品では、 構造の軽やかさと自然との対話を探究し、建物が浮遊し、フレーム となり、そして後退する様を表現する。一方で「吉野杉の家」は住居 であると同時にコミュニティーを象徴し、ヴァナキュラーの知恵に対 する感性を体現しながら、公と私をひとつ屋根の下に融合させる。

都市環境においては、「練馬のアパートメント」、「上尾の長屋」、「御 徒町のアパートメント」ではスケール・親密さ・共有空間を精密に 調整し、「五反田の住宅」と「経堂の住宅」では高密な都市環境にお ける新たな住まいの様式を垂直性や積層がいかに展開し得るか を提示している。

日本国外でも、長谷川の建築言語は同様の繊細さを繰り広げる。イ タリアの「グアスタッラの礼拝堂」では、壮大さではなく静けさ、幾 何学、光で神聖さを想起させる。

また「Villa beside a Lake」と「ICOR NISEKO」では気候、土地、知 覚との継続的な対話が、「せとのき」と「flying carpet」は構造の軽 やかさが叙情的かつ厳格に現れる。

出会いの場としての閾、身体的な関係性としてのプロポーション、 記憶や触覚の記録としての物質性といった反復されるテーマを、 これらの作品に共通して見ることができる。長谷川は単一の美学 に縛られることなく、敷地や利用者、光、時間と丁重に向き合い、各 プロジェクトが自然に現れることを受け入れている。

この一連の作品は答えを提示するのではなく、建築空間を問いか けの場として開いている。軽やかさに住まうことは可能か?丁寧に 建てることは何を意味するのか?建築はいかにして私たちの世界 意識を深められるのか?

This title gathers a selection of key projects from Go Hasegawa work, that offers a lens into the spatial, cultural, and poetic dimensions of his architecture.

From private dwellings to collective living, from rural Japan to European landscapes, this selection reveal a deep commitment to place, body, and memory.

Projects such as House in a Forest, Pilotis in a Forest, and House in Komazawa explore a lightness of structure and a dialogue with nature, where buildings hover, frame, and recede. On the other side, The Yoshino Cedar House, either a home and a gesture of community, embodies his sensitivity to vernacular knowledge, merging public and private life under a single roof.

In urban contexts, Apartment in Nerima, Row House in Ageo and Apartment in Okachimachi display his precision in negotiating scale, intimacy, and collective space, while House in Gotanda and House in Kyodo show how verticality and layering can unfold new modes of domesticity in dense metropolitan conditions.

Beyond Japan, Hasegawa’s language expands with equal subtlety. The Chapel in Guastalla in Italy evokes sacredness not through grandeur, but through silence, geometry, and light; Villa Beside a Lake and Icor Niseko reflects an ongoing dialogue with climate, land, and perception, as Setonoki and Flying Carpet manifest a structural lightness that is both lyrical and exacting.

Recurring themes like the threshold as a space of encounter; proportion as an embodied relationship; and materiality as a register of memory and tactility are find across these projects. Rather than imposing a singular aesthetic, Hasegawa allows each project to emerge through attentive listening to site, to users, to light, to time.

José Manuel Pedreirinho, architect, graduated from the Lisbon School of Fine Arts (ESBAL) in 1976 and has a PhD from the Architecture Faculty of the University of Seville (2012).

He has been working independently since 1980 and has also been a professor since 1985, teaching in Porto, as well taking on the role of director at Coimbra’s University School of Arts (EUAC) from 1990 to 2014. Since 1979 he has contributed to several newspapers and publications, and has authored several books on topics concerning the “History of Portuguese Architecture of the 20th Century”.

From January 2017 to 2020, José Manuel Pedreirinho was President of the Portuguese Association of Architects and of the Iberian Docomomo Foundation, as well as a member of the Executive Committee of the Architects’ Council of Europe (2018-2020). He is currently Vice-President of the International Council of PortugueseSpeaking Architects (CIALP).

歌川広重(1790–1858)によるこの版画は、日本美術と多くの西洋 美術の主要な相違点の一つ、すなわち三次元空間を表現するそ れぞれの独特な手法としてしばしば取り上げられ、空間表現にお ける相違を明確に映し出している。この特徴は20世紀初頭にフラ ンク・ロイド・ライトが既に指摘しており、空間的連続性の表現に革 命をもたらしたと見なし、彼自身の設計手法に決定的な転換を促 したとされる。したがって広重の版画において、そしてライトや多く の後続する建築家の作品において、奥行きが水平・垂直座標より 優先されていることも納得できる。

日本の美術や建築におけるこの奥行きは、平面の連続性と、その 間に創出される開口部や透明性によって顕著なものになる。空間 はこうした層を通じて体系化され、自然と人工の関係性が成り立 つ。それに対して西洋ではこうした関係性は概ね遠近法の規則に 基づいて構築され、より記念碑的な作品を生み出す傾向がある。 階調(版画における色彩的階調、あるいは建築における構築され た壁の階調)によって、連続する平面が空間の多様な読み取りを 組織し、それによって周囲の環境の明確な奥行きを定義する。身体 に対し異なる寸法や高さを持つ開口部は、隣接する建物、都市景 観、あるいは自然そのものとの多様な関係性において、常に内部 空間を拡張する手段となる。またこの平面の連続は、外部から私的 な内部空間へと向かう開口部を構成し、前述の第三の次元を明ら かにしたり、あるいは単にほのめかしたりする。

この動的性質は、ここに示された作品群において、必然的に生じる 階段によって作りだされる複数の対角線の交差によってしばしば 豊かさを増幅する。階段は内部空間を構成する上で不可欠な要素 であり、単なる動線空間を超え、ほとんどの場合は居住空間でもあ る。1世紀半以上を経た今もなお、こうした関係性が日本建築の多 くを特徴づけている事実は、それらがいかに深く同化され、文化に 融合されてきたかを示している。

これらの特徴の多くは、程度の差はあれ、長谷川豪の建築に明確 に現れていると私は考える。唯一の例外はイタリア・グアスタッラ の小さな礼拝堂で、ここではルネサンス的な遠近法への回帰が見 られた。

これらの特性は、都市への介入と自然環境における住居との困難 な両立を可能にする。都市の作品は、小規模な敷地という厳しい 制約の解決に強く左右されており、特に統合が難しい状況下にあ

る。ここで紹介する二つの集合住宅はその縮図である。だがそれ は同時に、こうした介入を通じて、手つかずの真の主人公である自 然の詩情への敬意を表現する上で決定的な役割を果たしている。

一見矛盾するように見えるが、そのどちらもが、この流動的な現代 社会において、いわゆる浮世絵の精神を体現している。

An example of what is often regarded as one of the key differences between Japanese art and much of its Western counterpart, the woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige (1790–1858), which illustrates this text, reflects the distinctive way in which the third dimension of space is expressed in Japanese visual culture.

This characteristic was already noted by Frank Lloyd Wright in the early 20th century, who referred to it as having revolutionized the way spatial continuity is represented, and who credited it with having profoundly influenced his own design approach. It is thus understandable that in Hiroshige’s prints—as later in Wright’s work and in that of many architects who followed him—depth is emphasized over the conventional horizontal and vertical coordinates, pointing to a redefinition of spatial perception and composition in architectural thought.

This depth, in Japanese art and architecture, is revealed through a succession of planes and of openings or transparencies created between them. It is through these layers that spaces are organized and that the relationships between the natural and the artificial are articulated relationships which, in the West, are generally structured on the rules of perspective, potentially producing works of a more monumental tendency. It is by gradation (chromatic in the prints, or of built walls in architecture) that successive planes organize multiple readings of space, thereby defining the distinct depths of the surrounding environment. With varying dimensions and different heights in relation to the human body,

Mark Lee is a partner of Johnston Marklee.

He served as Chair of the Department of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the Artistic Co-Director of the 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial. He is a fan of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

ルイス・カーンは野球好きだった。フィラデルフィア・フィリーズの球 場の一塁ベース脇のボックス席を陣取り、友人であるランドスケー プアーキテクトのイアン・マクハーグやグラフィックデザイナーのリ チャード・ソール・ワーマンらと試合を観戦した。同じく野球好き だった父を持つ伊東豊雄は、レム・コールハースを「機械式ピッチン グマシーン」に例えたことがある。それに対してコールハースは、こ の賞賛は日本人からでなければ侮辱として受け止めるだろうと答 えた。

技術に重きを置き、接触がなく、ゆったりとしたペースのスポーツ である野球は、建築とは切っても切れない関係にある。どちらも動 きと優雅さの組み合わせを必要とした、戦略と時間のゲームであ る。

もし現代の建築家でチームを編成し、歴史上の他の世代の建築家 たちと対決させるとしたら、私は長谷川豪をリードオフに据えた打 順を組みたい。

打順とは、チームの選手が相手投手に対して打席に立つ攻撃の順 番のことである。野球チームの攻撃戦略の主要な要素であり、各ポ ジションを慎重に調整しなければならない。リードオフとは先頭打 者、2番打者はバントや犠打ができるコンタクトヒッター、3番打者 は通常打率が高いが必ずしもスピードはない、4番打者あるいは 「クリーンナップ」は最もパワーがあり走者を一掃する役目を担 う、という具合だ。

なぜ長谷川豪をリードオフに据えるのか? 第一に、リードオフは試合のペースを握る重要なポジションの一つ である。2005年に事務所を設立して以来、彼のキャリアの特徴は ゆっくりと確実に成長してきたことにある。日本の戸建住宅から始ま り、着実に他のタイポロジー、他の地域へと拡大してきた彼の仕事 の進化は、歴史への畏敬の念を抱きながらも、その歴史の重荷に 縛られることは決してない。屋根や柱やバルコニーの伝統から空 間構成に至るまで、建築の言語への深い理解が、都市の成長と同 義である周辺コンテクストに一定のペースを与える。タブラ・ラサ に直面したときでさえ彼は類型学的な基盤をプロジェクトに組み 込んで、より大きな歴史的系譜を新しいコンテクストの創造に持ち 込もうとする。

2019年に長谷川をハーバード大学デザイン大学院に招聘した際 に、彼のスタジオでは、クレオールのタウンハウスやショットガンハ ウス、ダブルギャラリーハウスまで、ニューオーリンズの伝統的な 住宅タイポロジーを研究し、新たなタイポロジーの足掛かりとした。 スタジオのタイトル「Cross Rhythm — ニューオーリンズの新たな 住宅」は、動きのある対照的な複数のリズムを融合することで建築 が周辺に一定のペースを与えるという、彼の事務所の設計手法を 反映している。

第二に、リードオフは必ずしもチーム最強の打者ではないが、後続 の打者のために常に塁に出る方法を見つける打者である。たとえ それがプライベートな依頼であったとしても長谷川がある程度の 平凡さを好むことは、彼の作品に大きな共同体的倫理観を映し出 している。常に彼の建築には、目に映る以上のものがある。一見す ると簡素だがその背後にあるのは根本的な寛大さであり、居住者 とその周辺環境を歓迎して両者に機会を誘発する。彼の建築は、 豊かで複雑な建築がいかに周囲の実際の平凡さを受け入れそれ を変容させるかという「欺瞞的な平凡さ」の模範である。

2017年にシカゴ建築ビエンナーレでサイトスペシフィックな展示 を行うために長谷川を招いたとき、彼は最も平凡な場所、つまりシ カゴ公共図書館の元の建物と文化センターの改築部分をつなぐ 何ら特徴のない通路を任された。彼の介入は、既存の窓を半透明 の幕で覆いすべての照明を消して、一群のキャンバスの背景を金 箔貼りにするというシンプルなものだったが、その空間的効果は 魔法のようだった。均一な拡散光と金箔の反射の組み合わせは、 文化センター内で他に類を見ない謎めいた雰囲気を生み出した。 一日の中で揺れ動く柔らかな自然光は、2つの建築史のあいだに 位置する一過性の空間をさりげなく品位あるものにしていた。 長谷川は、最も困難な場所においても必要最小限の方法で、平凡 さを転覆する方法を常に見つけ出すのだ。

第三に、リードオフには高い出塁率、優れたスピード、選球眼、バッ トコントロール、盗塁能力が求められる。長谷川は、常に磨かれ研 ぎ澄まされた道具一式、つまりいつでも使える切実なテーマを持っ ている。そのひとつがスケールとプロポーションだ。彼の著作では しばしば「大きさ」と呼ばれ、空間同士に新たな関係をもたらすた めにプロポーションを変化させる操作である。過剰な誇張であろう と極限まで追い込んだものであろうと、この新しいプロポーション の探求は、大小、高低といった単純な差異によって建築を生み出す

「経堂の住宅」や「御徒町のアパートメント」といったプロジェクト が例として挙げられる。

さらに長谷川が「重さ」と呼ぶ、物理的重さと視覚的な重さの配分 というテーマもある。予測される重さのバランスに揺さぶりをかけ ることで、空間に新たな認識をもたらす。建築の文字通りの重さと 形態上の視覚的な重さが等価であると仮定して、素材とその構法 のロジックが、形態の全体像や抽象的な構成と調和して機能する。 これは大理石に予測される重さや不透明さといった特性が、ニッ チの軽さや半透明さと対照をなす「グアスタッラの礼拝堂」に明確 に表れている。

もう一つのテーマは、新しさと古さのあいだの宙吊りであり、長谷 川はそれを「時間」と呼ぶ。それは儚いものと永続的なものの間の 曖昧な状態である。不活性な静止状態ではなく、常に動き続ける 量子的状態なのだ。時代錯誤的なものと未来的なもののダイナ ミックな交差点に、長谷川は現代性を見出している。

「吉野杉の家」、「Villa beside a Lake」、「ICOR NISEKO」などのプロ ジェクトは、このテーマの最たる例であり、それらは今日のもので あると同時に別の時代にも属している。

なぜなら、建築は最後には必ずその原点に立ち返るものだから だ。常に前進しようと絶え間なく奮闘しながら原点というものに対 する理解をより深く変容させたうえで、最終的にはそこに戻るので ある。T.S.エリオットはこう書いている。「我々は探究をやめない そしてすべての探究を終えたとき もとの出発点に到着し その 場所を初めて知る」始まりは継続と進歩を生む基礎であるという、 揺るぎない信念。T.S.エリオットはそれを知っていた。ルイス・カー ンも、伊東豊雄も、レム・コールハースも知っていた。そして長谷川 豪もそれを知っている。

だから、私のリードオフマンは長谷川豪なのだ。

Louis Kahn was a baseball fan. Occupying a box right behind first base at the Philadelphia Phillies’ stadium, he attended games with friends such as the landscape architect, Ian McHarg, and the graphic designer, Richard Saul Wurman. Toyo Ito, whose father was also a baseball fan, once compared Rem Koolhaas to a “mechanical baseball pitching machine,” to which Koolhaas responded that only from a Japanese would such a compliment not be considered as an insult.

As a skill-based, non-contact, and leisurely-paced sport, the game of baseball has a long and inextricable relation with architecture. Both require combinations of action and grace; both are games of strategy and time.

If I were to assemble a team of contemporary architects to face off against other generations of architects in history, I would like to have a batting lineup with Go Hasegawa as the lead-off.

The batting lineup is the offensive sequence in which a team’s players take turns batting against the opposing pitcher. It is the main component of a baseball team’s offensive strategy as each position must be carefully calibrated. The lead-off is the first batter; the second batter is a contact hitter who could bunt or sacrifice; the third usually has a high batting average but is not necessarily very fast; the fourth, or “cleanup” has the most power to drive in runs and “clean” the bases, and so forth.

Why put Go Hasegawa as the lead-off batter?

First, the lead-off is one of the most important spots in the order as it sets the pace of the game. Since the founding of his office in 2005, Hasegawa’s career has been characterized by a slow and steady pace of growth. Beginning with the single-family houses in Japan and steadily expanding to other typologies and geographies, the evolution of his work is rooted in a reverence for history without being bounded by the baggage of that very history. From the tradition of roof types, columns, balconies, to spatial partis, a deep understanding of architecture’s language establishes a pace for the surrounding context synonymous with the growth of cities. Even when facing a tabula rasa, the typological foundations embedded in his projects bring a larger historical lineage to the creation of that new context.

When I invited Hasegawa to teach at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 2019, his studio researched New Orleans’ traditional house typologies, from the creole townhouse and shotgun house to the double-gallery house, as a springboard for new typologies. The studio’s title, “Cross Rhythm - New House in New Orleans,” reflects the design method of his office whereby the architecture sets the pace for its surroundings through the amalgamation of dynamic and contrasting rhythms.

Second, the lead-off is not necessarily the most powerful hitter on the team, but one who always finds a way to get on base for the rest of the order to follow. Even with the most private of commissions, Hasegawa’s predilection

for a certain degree of banality reflects a larger collective ethos in his work. There is always more than meets the eye in his buildings. Often beneath a seeming austerity is a fundamental generosity that is welcoming and instigates opportunities for both occupants and their surroundings. His buildings are exemplary of a deceptive banality, how a rich and complex architecture could ingratiate itself with and transform the actual banality of its surroundings.

When we invited Hasegawa for a site-specific installation in the Chicago Architectural Biennial in 2017, he was assigned to the most banal of locations – an uncharismatic corridor at the intersection between the original Chicago Public Library building and the Cultural Center renovation. His intervention was simple – covering the existing historical windows with translucent scrims and turning off all electric lights to backdrop against a series of canvases burnished in gold foil but the spatial result was magical. The combination of an evenly shrouded light and the reflectivity of the gold foil produced an enigma unlike any other within the Cultural Center. The soft, natural light that fluctuated across the day subtly dignifed a transitory space situated between two architectural histories.

Hasegawa always manages to find a way to turn banality on its head, with the most minimal of means and the most challenging of sites.

Third, a lead-off must have high on-base percentage, great speed, plate discipline, bat control, and the ability to steal bases. Hasegawa has a kit of tools that he constantly polishes and sharpens, an arsenal of essential tropes ready to deploy. One of them is Scale and Proportion. Often referred to as “Dimensions” in his writings, this operation changes proportion to bring about new relations between spaces. This search for a new proportion, whether a grotesque exaggeration or one brought to its extremities, is exemplified in projects such as the House in Kyodo or the Apartment in Okachimachi, which create architecture through the simple differentiations between large and small, or high and low.

Another trope is the distribution of Physical and Visual weight, which Hasegawa refers to as “Gravity.” It is the shifting of an expected balance of weights to bring about a new comprehension of spaces. It presumes an equivalence among the literal weights of tectonics

and the visual weight of plastic form, where materials and their logics of assembly work in concert with the gestalt of plastic form and abstract composition. This is evident in the Chapel in Guastalla, where the expected qualities of marble, such as weight and opacity, are contrasted with the lightness and translucency in the niches.

Another trope of Hasegawa’s is the suspension between Newness and Oldness, which he often refers to as “Time.” It is the state of ambiguity between the ephemeral and permanent. Rather than an inert stasis, it is a quantum state of constant motion. Within this dynamic intersection between the anachronistic and futuristic, Hasegawa finds the contemporary. Projects such as Yoshino Cedar House, Villa beside a lake, or ICOR NISEKO are some of the best examples of this trope, whereby they belong to both today’s time and that of another.

Because at the end, architecture always comes back to its beginnings. While perpetually striving to move forward, it ultimately returns to its origins with a deeper and transformed understanding of those origins. As T.S. Eliot wrote, “We shall never cease from exploration. And the end of all our exploring. Will be to arrive where we started. And know the place for the first time.”

It is an unwavering belief that beginnings are the foundations that beget continuity and progress. T.S. Eliot knew that; Louis Kahn knew that; Toyo Ito knows it; Rem Koolhaas knows it; and Go Hasegawa knows it too.

That is why I have Go Hasegawa as my lead-off.

Louis Kahn era um apreciador de basebol. A partir do seu camarote, atrás da primeira base no estádio dos Philadelphia Phillies, assistia aos jogos na companhia de amigos, entre os quais o arquitecto paisagista Ian McHarg e o designer gráfico Richard Saul Wurman. Toyo Ito, cujo pai também era fã de basebol, comparou certa vez Rem Koolhaas a uma “máquina lançadora de basebol mecânica”, ao que Koolhaas respondeu que só de um japonês tal elogio não seria tomado como um insulto.

Enquanto desporto de perícia, sem contacto físico e de ritmo pausado, o basebol mantém uma longa e inextricável relação com a arquitectura.

Nagano, Japan

全体も部分の一つである 自然豊かな森のなかに建つ小さな週末住宅。矩勾 配の切妻屋根のヴォリュームのなかに、切妻天井を もつ様々な大きさの7部屋を並べる。屋根頂部に天 窓を設けているため、切妻屋根と切妻天井の間の 隙間=小屋裏は、半透明の天井を介してその下の部 屋に柔らかい光や木陰を落とす温室のようになった り、物見台に上がる階段室になったり、あるいは一方 の部屋から反対側上空の景色を見上げる奥行き数 メートルの深い窓になったりする。各部屋は隣り 合っているにも関わらず天井に差し込む光や風景が 刻一刻と変化するため、それぞれの経験はまるで森 のなかにバラバラに置かれた部屋のように独立した ものになる。さらに紅葉の樹冠の高さに浮かぶ物見 台からは、四季の変化を楽しむことができる。

建築は外観をもつため、外形がある種の全体性をも つ。建築のプランニングには外形ヴォリュームを分 割したり複数の部屋を連結したりと様々な方法があ るが、いずれにせよ部分と全体という強固な関係が 生まれる。しかし設計次第では、部分にいながら建築 全体を感じられるようにすることも、建築全体の大き さで外部環境を受け止めることもできる。それは最 初のこの住宅からこれまで一貫して考えてきたこと だ。全体も部分の一つである。

A small weekend house nestled in a rich forest. Within the volume of 45° gabled roof, seven rooms of various sizes all with gabled ceilings are arranged. Thanks to the skylights at the roof’s peak, the space between the gabled roof and gabled ceilings - the resultant attic space - acts as a greenhouse filtering soft light and tree shadows through a translucent ceiling into the rooms. The attic is also a stairwell to an observation deck, as well as a window several meters deep, orienting the rooms towards the sky on the opposite side of the house. Despite being adjacent to one another, the rooms maintain a feeling of independence, as if they were scattered throughout the forest, due to the ever-changing light and scenery filtering through the ceiling. Additionally, the observation deck, suspended at the height of the maple tree canopy, offers views of the changing seasons.

Considering architecture has an exterior appearance, its external form contains a sort of wholeness. There are countless ways to design it such as dividing the volume or connecting multiple rooms, but always a strong relation between part and whole emerges. Yet depending on the design, the experience can also be such that one feels the whole even within a part, or to take in the external environment with the size of the whole building. This spatial idea still remains relevant to me since this first house: the whole as one of the parts.

O todo como uma das partes

Uma pequena casa de fim-de-semana inserida numa densa floresta. No interior do volume, definido por uma cobertura de duas águas a 45°, dispõem-se sete compartimentos de diferentes dimensões, cujo tecto acompanha a inclinação da cobertura. Clarabóias, estrategicamente posicionadas no ponto mais elevado do telhado, permitem que o espaço entre a cobertura exterior e os tectos interiores funcione de forma similar a uma estufa, que filtra a luz e permite a entrada da sombra das árvores que envolvem a casa. O sótão, assume a função de caixa de escadas, que simultaneamente conduz a uma varanda, e orienta os quartos para o céu, na direcção oposta da casa. Apesar de adjacentes, os quartos garantem uma sensação de independência, como que dispersos pela floresta, em virtude da oscilação natural da luz e da paisagem visível através das claraboias, que permite observar a mudança das estações.

Considerando que a arquitectura representa uma identidade formal exterior, a sua forma inclui uma totalidade. Existem inúmeras possibilidades de a definir, nomeadamente quer pela fragmentação do volume ou pela articulação de múltiplos espaços, mas sempre indissociável de uma forte relação entre a parte e o todo. Contudo, de acordo com o seu propósito, a vivência espacial pode permitir que se perceba o todo a partir de uma parte, ou a apreensão da circunstância envolvente à escala do edifício, na sua totalidade. Esta ideia de espacialidade, continua pertinente para mim desde esta primeira casa: o todo como uma das partes.

Tokyo, Japan

副産物

東京都心の大小様々な建物が隙間をあけながら密 集するエリアの、敷地面積48平米の小さな角地に建 つ住宅。まず建物を2棟に分け、南棟を3階建て、北 棟を4階建てとする。2棟間の隙間のような幅1.2mの 空間を階段室を兼ねたホールとし、ガラス屋根を架 け、道路側に建物と同じ高さ約10mの大きな玄関扉 を設けた。気候が良い日には玄関扉を開放すれば 光や風が一瞬で住宅全体に流れ込む。また螺旋階 段が隣家との隙間に突き出しているため、階段を上 り下りすると南棟の部屋から、隣家との隙間、北棟 の部屋、ホール…といったように、インテリアと街を 交互に体験する。無意識のうちに建物の輪郭や敷地 境界を超えて、建物のなかというより都市の風景の なかで暮らしているように感じられる。

設計の主産物が建物そのものだとしても、設計する とどうしても生じてしまう副産物が気になる。具体的 には隣家とのあいだの隙間や、最初の「森のなかの 住宅」の小屋裏なども設計の副産物だといえるだろ う。試しに、主産物と副産物の図と地の関係を試しに 反転させてみよう。あるいは副産物には明確な機能 がないので、新たな使いかたを想像してみよう。設 計の無意識を意識することで、客観的な視点や思い がけない自由を得られるときがある。

A house on a small 48m² corner lot in central Tokyo where buildings of various sizes are crowded together, leaving small gaps between them. The volume is split into two wings: the south wing with three floors, the north wing with four. Between these two wings, a 1.2m wide space serves as a hall and stairwell, covered by a glass roof and closed on the street side by a 10m door which is as tall as the building. On days with pleasant weather, when this door is opened, light and wind instantly flow through the house. The spiral staircase protrudes into the gap shared with the neighbours. Ascending and descending it constantly alternates the experience between house and city, from a south wing room to the gap, from there to a north wing room, and to the hall. Unconsciously, one feels they live in the urban landscape rather than inside a house, transcending the building’s contour and site boundary.

Even if the main product of our design is the building itself, I am always curious about its inevitable byproducts: the gaps between buildings, or the attic space in the ‘House in a Forest’ project. For example, reversing the figure-ground relationship between main product and byproduct. Seeing as byproducts do not have a clear function, I suggest finding new ways to use them. The consciousness about the “unconsciousness of the design” can sometimes reveal objective perspective and unexpected freedom.

Subproduto

Uma casa num pequeno gaveto de 48m² no centro de Tóquio, onde edifícios de vários tamanhos se aglomeram e deixam pequenos vãos entre si. O volume divide-se em dois: a sul com três pisos e a norte com quatro. Entre eles, um espaço com 1,2m de largura acolhe o hall e a escada, coberto por um teto de vidro e fechado para a rua por uma porta de entrada tão alta como o edifício, com cerca de 10m de altura. Nos dias agradáveis, quando esta porta é aberta, a luz e o vento entram instantaneamente pela casa. A escada em espiral projeta-se no vão com os vizinhos, de modo que subir e descer alterne constantemente a experiência entre a casa e a cidade, uma divisão no volume a sul para o vão, para uma divisão no volume norte e vice versa. Inconscientemente, a sensação é a de viver numa parte da cidade, em vez de dentro de uma casa, transcendendo o contorno do edifício e os limites do terreno.

Mesmo que o produto principal do nosso projecto seja o próprio edifício, tenho curiosidade sobre os seus inevitáveis subprodutos: os vãos entre os edifícios ou o sótão no projeto “Casa na Floresta”. Por exemplo, invertendo a relação figura-fundo entre principal e subproduto: como os subprodutos não têm uma função clara, sugiro novas formas de utilização. Estar consciente da “inconsciência do projecto” pode, por vezes, revelar uma perspetiva objetiva e uma liberdade inesperada.

Tokyo, Japan

匿名性と開放性 都内の駅前通りに建つ20戸の賃貸集合住宅。社会 人と学生の両方をターゲットにするため住戸にいく つかのヴァリエーションをつくることが求められた。 戸建て住宅の庭のように、インテリアと同じくらい大 きなテラスを各住戸に用意する。しかも居室に従属 するようなバルコニーではなく、角部屋の住戸にはL 型テラス、細長い住戸には細長テラス、3層メゾネッ ト住戸には3層吹抜けの縦長テラスといったように、 強烈な個性をもった半屋外空間をインテリアに併置 する。テラスを介して街を見下ろしたり空を見上げた りと住人の意識が外部環境に向かい、生活が ファサードに現れる。

都市生活には匿名性がある。雑踏に紛れ込むと人を 見失うのと同様に、多くの他者と集まって暮らしてい れば隠れなくてもある程度のプライバシーが確保さ れる。それは田舎では成立しない都市生活の質だ。

にもかかわらず集合住宅の多くは開口を最小にし てカーテンを閉め切りプライバシーをただ堅固にし ている。様々な個性をもつ大きなテラスが不均一に レイアウトされるこの集合住宅においては、どのテ ラスがどの住戸のものなのか外から判別できない ため、テラスに滞在していても外の目が気にならな い。匿名性を利用すれば、都市住宅はもっと開放で きるはずだ。

A 20-unit apartment building located near a subway station in Tokyo. As the target audience includes both workers and students, it was necessary to offer various unit types. Each dwelling has a terrace similarly as large as its interior, not as an auxiliary balcony, but as a semi-open space with a strong character: the corner units have L-shaped terraces, the linear units have narrow and long terraces, and three-storey maisonettes have void terraces of the same height. Each unique balcony offers residents views of the street below and the sky above, sharpening the residents’ awareness of the exterior and reflecting everyday life on the façade.

Urban life comes with a certain anonymity: just as it is easy to lose sight of someone in a crowd, living alongside many others allows you to maintain a degree of privacy in plain sight. This paradigm does not often exist in the countryside. However, most apartment buildings merely consolidate their privacy through minimal openings and closed curtains. In this project, the large terraces arranged in an irregular layout make it impossible to distinguish from the outside which unit they belong to. Thereby, even when on the terrace, one does not feel the gaze of others. By facilitating anonymity, urban housing could produce greater openness.

Anonimato e abertura

Um edifício com 20 apartamentos localizado perto de uma estação de metro em Tóquio. Como o público-alvo inclui trabalhadores e estudantes, foi necessário oferecer várias tipologias. Cada unidade residencial possui um terraço quase tão grande como o seu interior, não como uma varanda subordinada, mas como um espaço semiaberto com um forte carácter: terraços em L para as tipologias de esquina, terraços estreitos e longos para tipologias lineares e terraços com altura de três pisos em duplexes de três andares. Oferecem aos moradores vistas da rua abaixo e do céu acima, aguçando a perceção do exterior e refletindo a vida quotidiana na fachada.

A vida urbana contém um certo anonimato: tal como é fácil perder alguém de vista no meio da multidão, viver ao lado de muitas outras pessoas permite manter um certo grau de privacidade sem se esconder. Este é um valor que não existe no campo. No entanto, a maioria dos edifícios de apartamentos apenas consolida a sua privacidade através de aberturas mínimas e cortinas fechadas. Neste projecto, a disposiçao dos grandes terraços num layout irregular tornam impossível distinguir do exterior a que tipologia pertencem. Mesmo estando no terraço, não se sente o olhar alheio. Ao utilizar o anonimato, a habitação urbana consegue usufruir de uma maior abertura para o exterior.

33.

34.

38.

Gunma, Japan

中立のプロポーション

深い森に建つ週末住宅。建物の下にいても高木の 幹まで見える高さ6.5mの軽快な鉄骨ブレース構造 のピロティによって、森にヴォイドをつくる。床はコン クリートの土間、天井は木梁、そして壁は既存の木々 の緑につくってもらってできる、大きな半屋外の部 屋。それとは対照的に上階は在来木造とし、低いとこ ろで梁下高さ1.9mのコンパクトな居室をつくる。

テーブル下に設けられたガラス床や天窓を介して、自 分がいる場所の高さが確認される。日中はピロティ に下りて森に囲まれてのんびり寛ぎ、日が暮れたら 上階に上って木の傍で眠る。

振り返ってみると自分の設計は、都市より自然のな かのプロジェクトのほうが自律的になる傾向があ る。自然のなかのほうが法規や敷地境界などの外在 条件が比較的緩く、建築エレメントやプロポーション などの建築の内在性が先鋭化するからであろう。こ の週末住宅ではピロティのプロポーションの検討が スタディの大部分を占めた。いくつも模型を作って辿 り着いた6.5mという寸法は、人間の身体に寄り過ぎ ず、かといってピロティが自然に溶け込まない高さ である。西洋的な美のためのプロポーションよりも、 人間と自然のあいだに新たな平衡状態をつくる、中 立のプロポーションに興味がある。

A weekend house built deep in a forest. Light pilotis, a 6.5m high steel braced structure creates a void in the forest, allowing the trunks of tall trees to be seen even from underneath the house. A large semi-open space is framed by a concrete floor, the wooden beam ceiling, and walls are naturally formed by the greenery of the existing trees. In contrast, the upper storey is a conventional wooden structure, with compact rooms of 1.9m high at the beams’ lowest point. Glass floors under the table and skylights allow you to perceive the height at which you are. During the day, you relax in the pilotis surrounded by the forest; after dusk, you sleep among the trees.

I realise that my projects in nature tend to be more autonomous than urban ones. As the natural environment imposes fewer external constraints such as regulations or site restrictions, it sharpens the inherent aspects of architecture such as element and proportion. In this house, defining the pilotis proportion was central to the design: the 6.5m height reached after examining with many models, is not too close to the human scale, nor too high to dissolve completely into nature. Rather than a Western proportion for beauty, I am more interested in such a proportion for neutrality that creates a new equilibrium state between human and nature.

Proporção para neutralidade

Uma casa de fim de semana construída numa floresta densa. Um pilotis leve com uma estrutura em ferro de 6,5m de altura proporciona um vazio na floresta, e permite que os troncos das árvores altas sejam vistos de baixo da casa. Um generoso espaço semiaberto é definido pelo pavimento em betão, pelo tecto com vigas de madeira e paredes formadas pela vegetação das árvores existentes. Em contraste, o piso superior é uma estrutura de madeira convencional, com divisões compactas de 1,9m de altura no ponto mais baixo das vigas. Os pavimentos de vidro sob a mesa e as claraboias permitem percecionar a altura. Durante o dia, relaxa-se nos pilotis rodeados pela floresta; ao anoitecer, dorme-se entre as árvores.

Noto que os meus projetos na natureza tendem a ser mais autónomos do que os urbanos. Como a natureza impõe menos restrições externas, incluindo regulamentos ou limites de terreno, aguça os aspetos inerentes da arquitetura, como o elemento e a proporção. Nesta casa, definir a proporção do pilotis foi fundamental: os 6,5m alcançados, após muitas maquetes, não se aproximam muito da escala humana, nem se dissolvem completamente na natureza. Em vez da proporção ocidental de beleza, interessa-me a proporção para uma neutralidade que crie um novo estado de equilíbrio entre o homem e a natureza.

Tokyo, Japan

建築が湛える気配

都内の住宅地に建つ木造2階建ての住宅。1階は地 面と地続きの土間のスペースにして階高を高くし、 向かいの梅林の眺めを大窓で切り取る開放的なリ ビングにする。2階は低い部分で1.3mの小屋裏のよ うな空間で、棟梁から中央で吊られた鉄骨梁の上に 38×64mmの華奢な小梁を30mmの隙間をあけて 並べ、2階の半分は合板を張って寝室や水回りとし、 もう半分はルーバー状の床の書斎とする。1階の大 窓と2階のトップライトをこのルーバー状の床がつな ぐ。1階からは頭上に明るさや広がりを、2階からは 足元に公共的な雰囲気をといったように、それぞれ がお互いの環境を求め合う2階建ての新たな経験 を目指した。

ルーバー越しに差し込むストライプ状の光がいつの まにかリビングの壁をぐるりと半周回っていた。そし て太陽が雲に隠れたのかじんわりと暗くなりまた明 るくなった。特定の瞬間よりも、この住宅全体の様相 が非常にゆっくりと変化していくさまが印象に残っ ている。それは時間をかけて感受される余韻のよう なものだ。建築は地面に固定されていて動かないが ゆえに、そしてその大きさゆえに、微かな内外の環境 の動きや変化を増幅させ、それを気配として湛えて いる。建築ならではの、ゆっくりと動く大きな気配に ついて考えている。

Aura filled in architecture

A two-storey wooden house in a Tokyo residential area. The ground floor is an open living room with traditional Japanese doma -like floor connected to the ground, high ceiling, and a large window framing the neighbouring plum orchard. The first floor is an attic-like space: only 1.3m high at its lowest point. Three steel beams hung from the roof framework support a row of 38×64mm joists at 30mm intervals. Half of the first floor is finished with plywood as it houses the bedroom and sanitary space, while the other half is a slatted-floor study room. This slatted-floor connects the large ground level window and the skylight on the upper level, bringing overhead light and spaciousness to the ground level, while the first floor participates in the public atmosphere below. The aim was to allow the two environments to reinforce each other as a new experience of a two-storey house.

The striped light passing through the slats slowly had circled halfway around the living room walls, before I knew it. The room darkens and brightens gently, as if breathing with the clouds. More striking than any specific moment is the continuous and very slow transformation of the entire house, resonating through time. Fixed to the ground and due to its scale, the architecture amplifies the small movements of its surroundings, retaining them as an aura. I constantly think about this uniqueness of architecture; this large, slow-moving aura.

Aura presente na arquitectura

Uma casa de madeira de dois pisos numa zona residencial de Tóquio. O piso térreo é uma sala de estar aberta com piso tradicional japonês doma directamente assente no solo, pé-direito alto e uma grande janela que emoldura o pomar de ameixas vizinho. O primeiro piso é um espaço semelhante a um sótão: com apenas 1,3m de altura no seu ponto mais baixo. Três vigas de ferro pendem da estrutura do telhado, e suportam uma serie de vigas de 38x64mm com intervalos de 30mm. Metade deste piso é revestido com contraplacado, no quarto e casa de banho, enquanto a outra metade, uma sala de estudo, é mantida aberta atraves de portadas. Este piso de portadas estabelece a ligação atraves de uma grande janela do piso inferior e a claraboia do piso superior, que garante a entrada de luz e amplitude ao piso térreo. Enquanto o primeiro piso participa na atmosfera pública que se encontra por baixo. O objetivo era permitir que os dois ambientes se reforçassem mutuamente como uma nova experiência de uma casa de dois andares.

A luz que passava pelas portadas circula lentamente até metade das paredes da sala de estar. O quarto escurece e clareia suavemente, como se respirasse com as nuvens. Mais impressionante do que um momento específico é a transformação contínua e muito lenta de toda a casa, ao longo do tempo. Fixada ao solo e devido à sua escala, a arquitetura amplifica as pequenas variações da envolvente, mantendo-as como uma presença. Penso nesta singularidade da arquitectura; nesta aura ampla e em movimento lento.

Tokyo, Japan

非凡な平凡

閑静な住宅地に建つ編集者夫婦のための小住宅。 蔵書量が多いため本棚を並べて1階をいわば「本の 家」にして、浴槽や書斎机やベッドなどを本棚の間 に挿入して住人はそこに棲みつく。1.8mに抑えた天 井高が本と身体の関係を親密にする。2階はリビン グとテラスだけの広々とした空間にして、鉄板構造 による総厚60mmの薄い屋根をそっと架ける。光や 周囲の緑が鉄板の天井面に柔らかく反射して室内 はまるで屋上のような開放感になる。壁は内外とも に繊維強化セメント板で構成する。巣穴のような1階 と開かれた2階という、強く対比づけられた空間を行 き来しながら2人は生活する。

新しさを提示しようとして建築家は周囲とまったく異 なる孤立した建物をつくりがちだが、特に住宅地の ようにほとんど同じ敷地条件のなかでは、むしろ周 りと同じであることを認めることでより大きな世界と 繋がることができる。同時期に設計していた「駒沢の 住宅」とこの住宅は木造家型2階建てというありふれ た形式から設計を始めているという点で共通する。 誰もが知る形式を用いて思いがけない新鮮な経験 をつくる。非凡な平凡に関心がある。

A small house for an editor couple in a quiet residential neighbourhood. Due to their extensive book collection, the ground floor was turned into a “house of books”, where bookshelves line the ground level space, which includes a bathtub, a writing desk, and a bed inserted among them: the residents live nestled within the shelves. The ceiling height is restricted to 1.8m, making the relationship between body and books more intimate. The upper floor is spacious, consisting only of the living room and terrace, lightly covered by a thin 60mm roof made of steel-plate. Light and surrounding greenery softly reflect on the metal ceiling, giving the interior a rooftoplike openness. Both interior and exterior walls are configured with standardsize fibre cement board. The couple lives between this contrast: a cave-like ground floor and an open upper floor.

Architects often seek novelty by creating isolated buildings entirely different from their surroundings. Yet, especially in residential areas with homogeneous site conditions, acknowledging sameness with the surroundings allows a strong connection to the larger world. This house, along with the ‘House in Komazawa’ designed during the same period, begins from an ordinary typology — a two-storey wooden house — to create an unexpectedly fresh experience. I am interested in such a special banality.

Banalidade especial

Uma pequena casa para um casal de editores num tranquilo bairro residencial. Com a sua extensa biblioteca, o piso térreo foi transformado numa “casa de livros”, no qual estantes se alinham com o espaço, entre uma banheira, uma secretária e uma cama: os moradores vivem “aninhados dentro de prateleiras”. O pé-direito está limitado a 1,8m, o que torna a relação entre o corpo e os livros ainda mais íntima. O primeiro piso é espaçoso, e acolhe apenas a sala de estar e o terraço, ligeiramente coberto por uma chapa de 60mm de espessura. A luz e a vegetação circundante refletem-se suavemente no tecto metálico, conferindo ao interior uma abertura semelhante à de um telhado. As paredes interiores e exteriores são feitas em placas de fibrocimento de tamanho standard. O casal vive entre o piso térreo, semelhante a uma caverna, e o piso superior, semelhante a uma clareira.

Os arquitectos procuram frequentemente a novidade criando edifícios isolados, totalmente diferentes dos edificios próximos. No entanto, em áreas residenciais nas quais as condições do terreno são semelhantes, reconhecer a semelhança com a envolvente permite uma forte ligação com o mundo exterior. Esta casa, tal como a “Casa em Komazawa”, projectada no mesmo período, parte de uma tipologia comum. Uma casa de madeira de dois pisos, que proporciona uma experiência inesperadamente nova. Interessa-me esta banalidade especial.

Tokyo, Japan

新たな集合のかたち

都心の賑やかなエリアに建つ16戸の賃貸集合住 宅。喧噪から程よく守られた住環境をつくることが 求められた。一般的な階高だと8層になるところを、 階高を2.6mに抑えて10層入れる。それだと容積が 余るため各階の2住戸のあいだに幅800mmの隙間 をあけて平面形を変化させながら積層させ、10層の 吹抜けで立体的に繋がるポーラス状の立体をつく る。この隙間に向けて各住戸に窓や天窓を注意深く 穿ち、例えば2階住人が天窓と吹抜け介しに空を見 上げ、西側住人が隙間を介して東に上がる花火を楽 しむような、建物全体を縦横に串刺しにする視線の 抜けをつくる。まるで階数や方位による優劣を解消 するかのように住戸同士が譲り合って環境を分配し ている。

集合住宅が個の集合であることは、外観から少しは 分かるが内部からは全く知覚できないつくりになっ ている。壁や床の向こう側に隣人がいるのに互いに 存在しないふりをしながら暮らしていることにずっ と気持ち悪さを感じていた。この集合住宅の吹き抜 けには幾何学化された様々な隣人の生活のかたち が浮かぶ。個の集合であることが抽象的に可視化さ れ、自分自身の存在も客観視される。全体から切り だされた部分としての個ではなく、独立した個が思 い思いに居ることを認め合うアジア的な集合のかた ち風景を考えたいと思っている。

A 16-unit rental apartment building constructed in a bustling part of central Tokyo. The aim was to create a living environment gently shielded from noise. In a volume a housing complex usually fits 8 floors, the floor height was reduced to 2.6m, allowing to fit 10 floors. To adjust the volume, an 800mm gap was left between two units on each floor, creating a stack of units, a porous structure, linked by a continuous 10-floor void. Each unit’s window and skylight open into this gap: a resident on the first floor can see the sky through the skylight and void, while a resident on the west-side can enjoy fireworks bursting in the east through the gap. Light, air, and views are fairly shared, dissolving inequalities of floor level or orientation, as if units are considerate of each other.

Strangely enough, in the typical apartments complex, collectivity is visible on the façade but not perceived on the inside — neighbours share walls and floors, yet acting as if the other does not exist. The void of this apartment is filled with geometric representations of the lives of various neighbours. The collection of individuals is abstractly visualised, reflecting our own existence objectively. The project proposes an alternative collectivity: not individuals cut out from a whole, but individuals coexisting freely, recognising each other’s presence, as is common in East Asia.

Colectividade alternativa

Um edifício de 16 apartamentos para arrendamento construído numa zona movimentada do centro de Tóquio. O objectivo era proporcionar um ambiente de convívio protegido do ruído. Num volume que geralmente teria 8 pisos, o pé-direito foi reduzido para 2,6m, para permitir a construção de 10. Para ajustar o volume, foi deixado um vão de 80cm entre dois apartamentos por piso, criando um conjunto de unidades cuja ligação é estabelecida através de um vazio contínuo que constitui uma estrutura porosa. Cada apartamento abre uma janela e uma claraboia para este vão: um morador do primeiro andar pode ver o céu através da claraboia e do vazio, enquanto um morador da zona oeste pode apreciar o fogo de artifício a subir para leste através do vão. A luz, o ar e as vistas são partilhados de forma justa, dissolvendo as desigualdades de nível ou de orientação do piso, como se todos os apartamentos se respeitassem mutuamente.

Curiosamente em apartamentos comuns, a colectividade é visível na fachada, mas não percebida no interior. Os vizinhos partilham paredes e andares, agindo como se o outro não existisse. O vazio de cada apartamento é preenchido por representações geométricas da vida de vários vizinhos. O conjunto dos indivíduos é visualizado abstratamente, refletindo objectivamente a nossa própria existência. Este projecto propõe uma coletividade alternativa: não indivíduos separados de um todo, mas uma coexistencia livre de indivíduos que reconhecem a presença uns dos outros, como é comum no Leste Asiático.

DETAIL

DETAIL

DETAIL

DETAIL DETAIL

Nara, Japan

全身的感覚の復権

東京の展覧会 “HOUSE VISION 2016” 2016 に建て、会期後に奈良県吉野町に移築したコミュニ ティスペース併設のゲストハウス。奈良の民家に見 られる二段勾配屋根のタイポロジー「大和棟」を参 照した細長い建物を吉野川沿いに建てる。間口いっ ぱいの縁側を屋内に拡張した開放的な1階のコミュ ニティスペースは内装と家具のすべてを吉野杉で、 小屋裏階の三角形断面のゲストハウスはすべて吉 野檜で仕上げる。自然に対峙する縁側と小屋裏とい う二つの建築エレメントを肥大化させて積層した建 築で、吉野の豊かな環境を体感する。

床やテーブルの杉に身体が触れるよう掘りごたつ 式にしたり、寝たときに全身が檜に接近するように 小屋裏の寸法を絞るなど素材と身体のコンタクトを 増やす。吉野材の木目の美しさを活かすだけでなく 手触りや匂いを意識したのは、視覚情報よりも手触 りや匂いのほうが長く記憶に残るということに関心 があったからだ。ただし私たちは感覚単体の寄せ集 めで世界を感受しているわけではないから、手触り は触覚、匂いは嗅覚と、感覚と器官を機械部品のよ うに一対一対応させる設計はしない。人間の全身的 な感覚を復権する建築を考えたいのである。

A guesthouse with a community space, first built for the exhibition ‘HOUSE VISION 2016’ in Tokyo and later relocated to Yoshino, Nara. Referencing the local two-step gabled roof typology Yamatomune, a longitudinal building stands now along the Yoshino River. The open ground floor community space unified with full frontage engawa is finished entirely in Yoshino cedar for both interiors and furniture. The attic-level guesthouse with its triangular section is finished entirely in Yoshino cypress. By enlarging and layering two architectural elements facing nature—the engawa and the attic—this project aimed to create an architecture that fully conveys the rich environment of Yoshino.

Contact between body and material is heightened: sunken seating lets the body touch the cedar floor and table, while the reduced attic size surrounds the body with cypress when lying down. Beyond the beauty of Yoshino wood grain, the project engages touch and scent, out of interest in how these memories last longer than visual impressions. Yet, because we do not perceive daily life through a mere collection of isolated senses, touch is not treated as merely tactile, nor scent as merely olfactory—as if sense and organ could be mapped one-to-one like mechanical parts. I intend to imagine an architecture that restores the full-body sense of human experience.

Recuperar o sentido do corpo por inteiro

Uma casa de hóspedes e espaço comunitário, construída para a exposição HOUSE VISION 2016 em Tóquio e depois transferida para Yoshino, Nara. Inspirada na tipologia local de telhado em duas águas, Yamatomune, um edifício longitudinal ao longo do rio Yoshino. O espaço comunitário no piso térreo, é unificado por uma fachada contínua, engawa, construida em madeira de cedro de Yoshino, tanto no interior quanto no mobiliário. Por sua vez o sótão, de secção triangular é destinado ao acolhimento de hóspedes e construido em madeira cipreste de Yoshino. Ao ampliar e sobrepor dois elementos arquitetónicos voltados para a natureza, a engawa e o sótão, o projecto procurou criar uma arquitectura que reflectisse profundamente a riqueza da circunstancia envolvente.

O contacto entre o corpo e o material é reforçado: os bancos permitem tocar diretamente o pavimento e a mesa é de cedro; no sótão, reduzido, o corpo deitado é envolvido por madeira cipreste. Para além da beleza dos veios da madeira de Yoshino, o projecto abraça o tacto e o cheiro, procurando perceber como estas memórias perduram mais do que impressões visuais. No entanto, como não percebemos a vida cotidiana por meio de um mero conjunto de sentidos isolados, o tacto não foi tratado como meramente tátil, nem o olfato como meramente olfativo, como se sentido e órgão pudessem ser mapeados um a um, como peças mecânicas. Pretendo imaginar uma arquitectura que restaure a sensação corporal completa da experiência humana, e recuperar o sentido do corpo por inteiro.

Kanagawa, Japan

宙吊り

東京近郊の傾斜地に建つ二世帯住宅。敷地は高さ 4.5mの擁壁のうえに高低差4mの斜面がある。既存 擁壁の造り直しを避けるために4本の杭を打ちヴォ リュームを宙に待ち上げ、そこから地形をトレースす るように斜床を吊り下げて地表面に建物の荷重をか けないようにする。上階ではリビングと南北にはね 出した母寝室やバルコニーから富士山を眺める。ま た地面からわずかに浮かぶ下階の斜床から両側に 並走する斜面の庭を間近に楽しみ、庭師の夫が手入 れする。斜床は座って本を読んだり昼寝ができる第2 のリビングになるとともに、上階で生活する母と下階 の夫婦のあいだに程よい距離感を生む。

これまで設計してきたどの個人住宅においても、個 が独占できない場をどこかにつくろうとしてきた。住 宅のなかに地形がなだれ込んだかのようなこの斜 床は、床下であり、庭の延長であり、地形そのもので あり、第2のリビングであり下階にアクセスする スロープでもある。どこにも誰にも属さない、意味的 にも構造的にも宙吊りになった斜床は、小さな住宅 に大きな他者として迎え入れられている。宙吊りの 場が、住宅を解放する。

A two-family house on sloping land near Tokyo. The site features an existing 4.5m retaining wall, supporting the 4m slope above it. To avoid reconstructing the existing retaining wall, four piles lift the main volume into the air, from which a sloping floor is suspended, as if tracing the terrain, without transferring building loads directly to the ground. On the upper floor, the living room, the mother’s bedroom and the balcony cantilevered to the north and south offer views of Mount Fuji. On the lower level, which is slightly lifted from the ground, the sloping floor opens directly to gardens running along both sides, maintained by the gardener husband. The sloping floor becomes a “second living room” where one can sit, read, or nap. This space also creates a gentle distance between the mother living above and the couple living below.

In every private house I have designed, I have sought to create a place that cannot be monopolised by an individual. Here, the sloping floor, spilling into the house as if the terrain had flowed inside, is simultaneously underfloor, garden extension, topography itself, a second living room and a sloped access to the lower floor. Belonging to no one and nowhere, suspended both structurally and semantically, this sloping floor enters the small house as a significant “other”: a place held in suspension that liberates the dwelling.

Mantido em suspensão

Uma casa para duas famílias num terreno inclinado perto de Tóquio. O terreno possui um muro de contenção de 4,5m, seguido de um declive de 4m. Para evitar a reconstrução do muro de contenção existente, quatro estacas elevam o volume principal, a partir do qual se suspende um piso inclinado, como se traçasse o terreno, sem transferir as cargas da construção diretamente para o solo. Do piso superior, a sala de estar, o quarto da mãe e a varanda em balanço a norte e a sul oferecem vistas para o Monte Fuji. No nível inferior, ligeiramente elevado do solo, o piso inclinado abre-se diretamente para os jardins que se estendem por ambos os lados, cuidados pelo marido, que é jardineiro. O piso inclinado torna-se uma “segunda sala de estar”, na qual se pode sentar, ler ou dormir uma sesta, e que garante também uma distância suave entre a mãe que vive no andar de cima e o casal que vive no andar de baixo.

Em cada casa particular que desenhei, procurei criar um espaço que não pudesse ser monopolizado por um indivíduo. Aqui, o piso inclinado, que se extende para dentro da casa como se o proprio terreno tivesse fluído para dentro, é simultaneamente subsolo, extensão do jardim, ou topografia em si mesmo. Uma segunda sala de estar e um acesso inclinado ao andar inferior. Não pertencendo a ninguém e a lugar nenhum, suspenso estrutural e semanticamente, este piso inclinado adentra a pequena casa como um “outro” significativo: um lugar mantido em suspensão que liberta a habitação.

Plasterboard 9.5t, AEP

12. Diagonal brace: 150x150

13. Tokonoma: Beech 12t, OSCL

14. Floor: Tatami 15t; Structural plywood 12t; Floor beam 45x75 @455

15. Beam 150x150

Guastalla, Italy

物質と時間の厚み

イタリアのヴェローナで国際的な石の展覧会 “Marmomac”に展示した後にグアスタッラ市の公 共墓地に移築した礼拝堂。近年、西ヨーロッパでは 火葬が増えて遺族が散骨の儀式をするための礼拝 堂を新設する動きがある。ヨーロッパの城などでよ く見られるニッチ+ベンチ+窓という「窓辺3要素」 を、380mm厚の大理石の12枚のプレートをくり抜く という単純な操作だけでつくる。くり抜いた半ドーム 型のニッチは地面から450mmの高さにあるのでベ ンチになり、10mm厚の大理石の最薄部は光が透け て「窓」になっている。

前作の「吉野杉の家」と同様に展覧会のために依頼 された仮設のパビリオンを、移築して恒久の建築と して設計するプロジェクト。3日間という展覧会の時 間と、移築後の建築的時間。レファレンスにしたアー チのプロポーションや「窓辺3要素」など建築のヴォ キャブラリーに蓄積された時間。太陽の動きに合わ せて「窓」が1つずつ輝く時間と、オルドビス期に生 成された大理石に流れる5億年という時間。これまで 手がけたなかで最小の、屋根すらないプロジェクト だが、さまざまな時間が流れている。物質と時間の 両方の厚みでできた、大理石の建築。

Breadth of matter and time

A chapel first exhibited at “Marmomac”, an international stone fair in Verona, and later relocated to the public cemetery of Guastalla. In recent years, cremation has increased in Western Europe, leading to the construction of new chapels for ceremonies of ash-scattering. This chapel was made through a simple operation: carving out 12 marble plates, each 380mm thick, to create the “three window-side elements” often seen in European castles— niche, bench, and window. The halfdome shaped niches, set at 450mm above the ground, serve as benches; where the marble thins to 10mm, light passes through to form “windows”.

Similarly to the ‘Yoshino Cedar House’, this project was a temporary pavilion commissioned for an exhibition, and later relocated as a permanent building. Within it, embodied multiple layers of time: the three days of the exhibition and the ongoing architectural time after relocation; the time in the history stored in vernacular architectural vocabulary, such as local arch proportions and the “three window-side elements”; the time marked by the daily passage of the sun and the windows light up one by one; and the 500 million years of geological time flowing through the Ordovician marble itself. Though the smallest project among those handled so far— without even a roof—it contains multiple timescales. A marble architecture made of the breadth of both matter and time.

Espessura da matéria e do tempo

Uma capela exposta pela primeira vez na “Marmomac”, uma feira internacional de pedra em Verona, e posteriormente transferida para o cemitério público de Guastalla. Nos últimos anos, a cremação aumentou na Europa Ocidental, levando à construção de novas capelas para as cerimónias de aspersão de cinzas. Esta capela foi construída através de uma operação simples: esculpir 12 placas de mármore, cada uma com 380mm de espessura, para criar os “três elementos laterais da janela” frequentemente vistos nos castelos europeus, nicho, banco e janela. Os nichos em forma de meia cúpula, colocados a 450mm de altura do solo, assumem a função de bancos; nos quais o mármore reduz de espessura até aos 10 mm, e permite a passagem de luz como uma “janela”.

Tal como na anterior “Casa de Cedro Yoshino”, este projecto é um pavilhão temporário encomendado para uma exposição, que é transferido posteriormente como edifício permanente. Incorpora múltiplas camadas de tempo: os três dias da exposição e o tempo arquitectónico contínuo após a mudança; o tempo armazenado no vocabulário arquitectónico, como proporções de arcos locais e os “três elementos laterais das janelas”; o tempo de passagem diária do sol, à medida que as janelas se iluminam uma a uma; e os 500 milhões de anos de tempo geológico que fluem através do próprio mármore ordovícico. Embora seja o projecto mais pequeno entre os já realizados, sem sequer ter um telhado, contém múltiplas escalas de tempo. Uma arquitectura de mármore feita da espessura da matéria e do tempo.

Shizuoka, Japan

土の隣

湖畔に建つ住宅。遊歩道からのプライバシーに配慮 しつつ湖の景色を楽しめる住宅が求められた。敷地 境界線をインセットしてフットプリントを最大化した 住宅の真ん中に、基礎工事で発生した残土を捨て ずに直径20.6mの巨大な土のシリンダーとして据え る。床は敷地の1.8mの高低差に沿わせてスロープ で繋いでいるため、場所によってシリンダーの高さ が変化する。シリンダー上面はフラットな土の中庭 になっており、スロープを上ったリビングから見ると 緩勾配の屋根に穿った円形の大きな穴が湖の眺め を切り取っている。

建築の断面や立面に描かれる一本の水平線は、本 来は大地と空が出会う境界面に過ぎない。にも関わ らず私たちはそれをグラウンドラインと呼び、屋根 の輪郭線をスカイラインと呼ぶ。つまり建築は大地 と空のあいだに割り込んで一本の水平線を二本の 線に引き裂いたわけだ。この住宅ではグラウンドラ インとスカイラインの間に、土のシリンダー上端とい う第2のグラウンドラインが身体的な高さに引かれ ている。土の上に立ち、座り、下に潜る。シリンダーの 周りをぐるぐる回りながら、土の隣で生活する。一本 の地球の輪郭線を建築が二本の線に分岐している ことを忘れないでこれからも設計していきたいと 思っている。

A lakeside villa designed to maintain privacy from a nearby promenade while offering views of the lake. The site boundary was set back to maximize the footprint. The soil excavated for the foundation was not discarded, rather it was reinstalled as a massive 20.6m diameter cylinder at the centre of the house. Because the floor follows the site’s 1.8m level difference with slopes, the height of the cylinder varies depending on the location. Its flat top becomes an earthen courtyard, and from the living room accessed from the slope, the large circular opening cut into the low-pitched roof frames the lake beyond.

A single horizontal line drawn in an architectural section or elevation is actually merely the boundary where earth meets sky. Yet we call it the ground line, and we call the roof’s outline the skyline. In other words, architecture inserts itself between earth and sky, tearing one line into two. In this house, there is another line defined by the upper edge of the soil cylinder, drawn at a human scale height. One can stand, sit, or go beneath the soil. Life unfolds beside the soil, circling around it. I want to continue designing architecture without forgetting that the single contour line of the Earth is split into two by its presence.

Junto ao solo

Uma casa junto ao lago concebida para manter a privacidade dos passeios marítimos próximos, ao mesmo tempo que oferece vistas para o lago. O limite do local foi recuado para maximizar a pegada, e o solo escavado para as fundações foi reutilizado como um enorme cilindro de 20,6m de diâmetro no centro da casa. Como o piso acompanha o desnível de 1,8m do terreno, a altura do cilindro varia consoante a localização na casa. A superficie superior transforma-se num pátio de terra batida e, a partir da sala de estar, que é acedida por uma grande rampa circular, a configuração disnivelada do telhado emoldura o lago.

Uma única linha horizontal desenhada numa secção ou elevação, é na verdade, apenas o limite onde a terra encontra o céu. No entanto, chamamos-lhe linha do solo e chamamos ao contorno do telhado horizonte. Por outras palavras, a arquitectura insere-se entre a terra e o céu, dividindo uma linha em duas. Nesta casa, uma outra linha, definida pelo limite superior do cilindro no solo, é desenhada à altura da escala humana. Pode-se estar de pé, sentar-se ou ir abaixo do solo. A vida desenvolve-se junto ao solo, circulando em torno dele. Quero continuar a desenhar arquitectura sem esquecer que a única linha de contorno da Terra está dividida em duas, pela sua presença.

Hokkaido, Japan

交響する

世界有数のスキーリゾートとして知られるニセコ町 に建つカフェ併用住宅。交通量の多い国道沿いの敷 地の反対側に土手があり、下りていくと羊蹄山の雪 解け水が注ぐ小川が流れ、国道の車の音は土手で 遮られてせせらぎ の音だけが聞こえた。土手上端の 等高線の形状に沿わせて、長さ51mの線状の片流 れ屋根を緩やかなS字形に配置する。細長いプラン をさらに長手方向に二等分して土手側をロッジアに する。土手に向かって大きく跳ね出した白樺の軒天 井がまるでスクリーンのように土手の反射光や草花 の色を映し出し、小川のせせらぎ の音が響くロッジ アで食事を楽しむ。

豊かな自然環境だからこそ、受け身の箱で建築を終 わらせない。地形に沿って緩やかにカーブする雄大 でランドスケープ的なスケールの屋根の下は、1.6m に抑えられた軒天の高さと1.8mピッチで反復する 逆V字柱によって親密で身体的なスケールになって いる。建築スケールが意図的に除外された、ランドス ケープ 的かつ身体的な屋根は、自然界のさまざまな 現象をその大きな面で受け止めて増幅し、建築の内 に、そして人間の体内に響かせる。身体を環境に同 期させ、自然界の要素が交わり響き渡る、交響する 屋根を考えたいと思っている。

A residence with a café in Niseko, a town renowned worldwide for its ski resort. The site lies between a busy road and a riverbank, where the stream fed by the snowmelt from Mount Yotei flows. Down by the water, the traffic noise disappears, leaving only the murmur of the stream. Following the contour of the riverbank, a linear, 51 m long single-slope roof was installed in a gentle S-shape. Beneath it, the space is divided lengthwise to create a loggia on the bank side. The birch-clad eaves extend out towards the riverbank, and act as a screen, softly reflecting the light from the bank and the colours of the flowers and plants. Here, one can sit and enjoy meals in this loggia, surrounded by the echoing sound of the babbling brook.

Precisely because of the rich natural environment, the architecture should not be merely an indifferent box. Beneath the vast roof, curving gently within the terrain at a landscape-like scale, lies an intimate, human-scaled space. This space is defined by the eaves restrained to a height of 1.6 m and by inverted V-shaped columns repeated at 1.8 m intervals. This roof refers only to the body and the landscape scale, deliberately excluding conventional architectural scale. Its broad surface amplifies natural phenomena, resonating through both architecture and body. I am interested in a symphonic roof that synchronises the human body with the environment, where varied natural elements intersect and reverberate.

Sinfónico

Uma casa com um café em Niseko, cidade conhecida pela sua estação de esqui. O terreno situa-se entre uma estrada movimentada e a margem de um rio, alimentado pelo degelo do Monte Yotei. O ruído do tráfego desaparece, e dá lugar ao som da água. A acompanhar o contorno da margem do rio, extende-se um só volume com um telhado de uma água, com 51m de comprimento e 4m de largura, em forma de S. O espaço interior foi dividido longitudinalmente. O beiral, em madeira de bétula, projecta-se em direcção ao rio, e actua como uma tela, que permite uma percepção e reflexão suave da luz e das cores das flores e plantas, no qual se pode desfrutar de refeições e do som do rio.

Por entre a natureza, a arquitectura evita ser uma caixa passiva. Sob o grande telhado surge um espaço íntimo e humano, que acompanha suavemente o terreno, através da altura do beiral, contido, de 1,6m, e do jogo de pilares e vigas em V, invertidos, que se repetem a cada 1,8m. O telhado reflecte a escala do corpo e da paisagem, excluindo deliberadamente a escala arquitectónica. A sua grande superfície amplifica as características naturais do local, tanto na arquitectura quanto no corpo humano. O meu objectivo foi construir um telhado sinfónico, capaz de sincronizar o corpo humano com a natureza, no qual diferentes elementos da natureza se cruzam e reverberam.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

Setouchi region, Japan

群れあるいは怪獣

瀬戸内海に面した南斜面に建つ長屋形式の15戸の 社宅。L型の外形のなかにジグザクに界壁を配置す ることでどの住戸からも南東に広がる海の眺望が見 えるようにする。さらに屋根の単位を建物でも住戸 でもなく一部屋くらいのサイズにまで細分化し、隣戸 に跨が せたT型断面の木造の屋根架構を複雑な地 形に沿わせて反復する。合計62枚の屋根が平面的 にも断面的にもずれることで、屋根や梁の隙間から 光が差し込む軒下のような居住空間が生まれる。周 りの瓦屋根の民家のように軒を低く抑えた小さな屋 根が、隙間をあけながら寄せ集まっている。

日本語には軒を連ねるという慣用句がある。軒を並 べるほど近接して隙間なく家や店などが立ち並ぶ 様子を意味し、路地や商店街などの通りの界隈性を 表すときに使われるが、この長屋の特徴は外周だけ でなく室内にも軒を連ねていることだ。まるで半屋 外のような住戸内にいると、自らの環境が両隣につ くられていることが実感される。レオ・レオニの「スイ ミー」は仲間の小魚と群れになって大きな魚のふり をして泳ぐことで巨大魚に立ち向かったが、この長 屋はその逆で、小さな軒の群れのふりをして巨大な フットプリントを小さな集落に忍び込ませて静かに 建つ、いわば軒の怪獣である。

Silent monster

A company housing complex of 15 row house units, built on a south-facing slope overlooking the Seto Inland Sea. The dividing walls were arranged in a zigzag configuration, to ensure that all units have the benefit of the view of the sea. The roof is fragmented to the size of a single room, instead of the scale of the building or dwelling. A T-shaped timber roof structure, extending over the neighbouring unit, is repeated to follow the uneven terrain. 62 individual roofs overlap and shift both in plan and section. It lets light filter through the gaps between roofs and beams, creating living environments similar to a space under the eaves. These small roofs with low eaves, similar to the surrounding tiled roof houses, are assembled together, leaving slight gaps between them.

The Japanese idiom “rows of eaves” refers to houses and shops lined up side by side, without gaps, found in alleys and commercial streets, expressing the neighbourhood’s character. Here, this feature also extends to the interior: standing within a dwelling that feels almost semioutdoor, residents feel their own interior space shaped by their neighbours on either side. Leo Lionni’s ‘Swimmy’ depicts a swarm of small fish pretending to be one large fish to confront a giant fish. This row house does the opposite: pretending to be a swarm of small eaves, it silently settles its enormous footprint into the small village. It is, in other words, a monster of eaves.

Monstro silencioso

Um complexo habitacional de 15 casas em banda, construído numa encosta a sul com vista para o Mar Interior de Seto. Para garantir que todas as unidades desfrutassem da paisagem marítima, as paredes interiores foram dispostas em zigue-zague, gerando plantas recortadas. Os telhados são subdivididos à escala de cada espaço, e não de cada casa como um todo. Estruturas de madeira em T, que se estendem entre unidades vizinhas, repetem-se acompanhando a irregularidade do terreno. 62 telhados individuais sobrepõem-se e deslocam-se em planta e em corte, permitindo a entrada de luz atraves de um jogo de desniveis reconstruindo um ambiente semelhante a um espaço sob beirais. Telhados pequenos, com beirais baixos como os das casas vizinhas de telha, agrupam-se deixando leves intervalos entre si.

A expressão japonesa “filas de beirais” refere-se a casas e lojas alinhadas lado a lado, sem vãos, como em becos e ruas comerciais. Aqui, esta característica estende-se também ao interior: espaços que parecem semi-externos. Os moradores sentem que possuem um espaço interior moldado pelos espeçaos vizinhos de ambos os lados. “Swimmy”, de Leo Lionni, retrata um cardume de peixes pequenos que fingem ser um peixe grande para enfrentar um peixe ainda maior. Este conjunto de casas faz o oposto: finge ser um aglomerado de pequenos beirais, atraves do qual instala silenciosamente a sua enorme pegada na pequena aldeia. É um monstro silencioso de beirais.

Mexico City, Mexico

テキスタイル的

メキシコ・シティのバラガン自邸の向かいの庭 “Jardín17”でのテンポラリープロジェクト。バラガン が設計したこの庭に来訪者の休憩スペースをつく る。一段高いレベルにあるコンクリートの通路を分 岐させるようにして、庭の中央部の茂みの上に「絨 毯」を浮かべる。直径21mmの水道管を並べた絨毯 の形状はミトラ遺跡の幾何学模様を参照しつつ既 存の樹木や草花の間を縫うように設計し、植物の根 を傷つけないように地面に挿入した鉄の柱脚で支 持する。訪問者は絨毯に腰を下ろし、樹肌や青い壁 に寄り掛かり草花の匂いを楽しみながら休憩するこ とができる。

「吉野杉の家」や「グアスタッラの礼拝堂」と同様 に、終わったら廃棄されるような仮設物には興味が なかった。「細い線」(水道管)を紡いだ「太い線」(通 路)を既存の樹木や草花と縫合することで「粗い面」 (絨毯)を作るというテキスタイル的な介入であれ ば、植物のスケールと合うしこの庭と上手く共存で きるのではないかと考えた。総長3.217kmに及ぶ水 道管は会期後に地元の設備業者に再利用されるこ とになり、絨毯は解体されメキシコ・シティの工事現 場に散った。この再利用のプロセスもまたテキスタイ ル的だった。

Textile-like

A temporary installation in ‘Jardín 17’, the garden designed by Luis Barragán opposite his private residence in Mexico City. A resting space was created by branching off from the concrete walkway: a “carpet” suspended above the garden’s central thicket. The carpet is made of 21mm water pipes, arranged in patterns inspired by the Mitla ruins. It weaves between existing trees and plants, supported by steel pillars inserted into the ground without harming the roots. Visitors can sit on the carpet, lean against tree trunks or the blue wall, and rest while enjoying the scent of the garden.

As with the ‘Yoshino Cedar House’ and the ‘Chapel in Guastalla’, the intention was never to build a temporary structure destined for disposal once its purpose was complete. I thought that a textilelike intervention – weaving a “thick line” (pathway) spun from “thin lines” (water pipes) to stitch together existing trees and plants, thereby creating a “rough surface” (carpet) – would align with the scale of the vegetation and coexist harmoniously with this garden. The 3.2km of water pipes were reused by local contractors after the exhibition: the carpet was dismantled and dispersed across construction sites in Mexico City. This process of reuse, too, was textile-like.

Semelhante a um tecido

Uma instalação temporária no jardim “jardín 17”, em frente à residência privada de Barragán, na Cidade do México. É criado um espaço de descanso para os visitantes deste jardim desenhado por Barragán. A partir de um passadiço de betão, é como que suspenso um “tapete” sobre as arvores centrais do jardim. O tapete é construido por canos de água de 21mm, dispostos em padrões inspirados nas ruínas de Mitla. Entrelaça-se por entre as árvores e as plantas existentes, e é suportado por inumeros perfis de ferro de pequeno perfil inseridos no solo sem danificar as raízes. Os visitantes podem sentar-se no tapete, encostar-se aos troncos das árvores ou à parede azul e descansar enquanto disfrutam do aroma do jardim.

Não me interessava uma estrutura temporária que fosse descartada após o cumprimento do seu propósito. Tal como na “Casa de Cedro Yoshino” e da “Capela em Guastalla”, procurei uma mesma abordagem e neste caso uma intervenção semelhante a um tecido: com “linhas grossas” (caminhos) a partir de “linhas finas” (canos de água) para costurar árvores e plantas existentes, e tecer uma “superfície áspera” (tapete), que se alinha à escala da vegetação e coexiste harmoniosamente com o jardim. Após o período da exposição, os canos de água com 3,2km de extensão total, foram reutilizados por empreiteiros locais: o tecido foi desmontado e dividido por estaleiros de construcção na Cidade do México. Um processo de reutilização semelhante a um tecido.

HOUSE IN A FOREST

project: 2005 - 2006

location: Nagano, Japan

client: Private program: Weekend House

architect: Go Hasegawa

structural engineer: Kanebako Structual Engineers

construction firm: Kiuchi Contractor area: 89.75m² images: © Go Hasegawa and Associates

HOUSE IN GOTANDA

project: 2005 - 2006

Location: Tokyo, Japan

client: Private

program: Single-family house

architect: Go Hasegawa and Junpei Nosaku

structural engineer: Kanebako Structural Engineers construction firm: Fukasawa Contractor area: 105.15m²

images: pages 028, 032 and 039 © Shinkenchiku-Sha page 034 and 036 © Takumi Ota

APARTMENT IN NERIMA

project: 2007 - 2010

location: Tokyo, Japan

client: Private program: Apartment + Shop + Office

architect: Go Hasegawa and Junpei Nosaku

structural engineer: Kanebako Structural Engineers project coordination : Misawa Homes A Project construction firm: Misawa Homes Tokyo area: 1054.26m²

images: pages 040 and 044 © Iwan Baan pages 046, 048 and 051 © Shinkenchiku-Sha

PILOTIS IN A FOREST

project: 2009 - 2010

location: Gunma, Japan

client: Private

program : Weekend House

architect: Go Hasegawa and Shu Yamamoto

structural engineer: Ohno Japan construction firm: Niitsu-gumi area: 77.22m²

images: pages 052, 058 and 060 © Shinkenchiku-Sha pages 056 and 065 © Hisao Suzuki

HOUSE IN KOMAZAWA

project: 2010 - 2011

location: Tokyo, Japan

client: Private

program: Single-family house

architect: Go Hasegawa and Shu Yamamoto

structural engineer: Ohno Japan

construction firm: Taishin Contractor area : 64.03m²

images: page 066 © Hisao Suzuki

pages 070, 073 and 076 © Iwan Baan

HOUSE IN KYODO

project: 2010 - 2011

location: Tokyo, Japan

client: Private

program: Single-family house

architect: Go Hasegawa and Hayako Ohba

structural engineer: Ohno Japan

construction firm: Taishin Contractor area: 69.52m²

images: © Iwan Baan

ROW HOUSE IN AGEO

project: 2013 - 2014

location: Saitama, Japan

client: Private program: Two-family house

architect: Go Hasegawa and Marina Takahashi

structural engineer: Ohno Japan

construction firm: Kudo Contractor area: 139.12m²

images: © Shinkenchiku-Sha

APARTMENT IN OKACHIMACHI

project: 2012 - 2014

location: Tokyo, Japan

client: Private

program: Apartment + Shop

architect: Go Hasegawa and Shu Yamamoto

structural engineer: Ohno Japan

project coordination: Misawa Homes A Project

construction firm: Misawa Homes West Kanto area: 701.80m²

images: pages 102, 106, 108, 110 and 112 © Shinkenchiku-Sha page 115 © Takaya Sakano

YOSHINO CEDAR HOUSE

project: 2015 - 2016

location: Nara, Japan

client: Airbnb, Yoshino Town, Community hosts

program: Guest House + Community Space

architect: Go Hasegawa and Taichi Asai

structural engineer: Ohno Japan

construction firm: Minami Contractor

area: 106.37m²

images: © Hisao Suzuki

HOUSE IN KAWASAKI

project: 2015 - 2017

location: Kanagawa, Japan

client: Private program: Two-family house

architect: Go Hasegawa and Taiki Yoshino

structural engineer: Ohno Japan

construction firm: Taishin Contractor

area: 78.42m²

images: pages 126 and 133 © Shinkenchiku-Sha pages 130 and 135 © Hisao Suzuki

CHAPEL IN GUASTALLA project: 2016 - 2017 location: Guastalla, Italy

client: Guastalla City, PibaMarmi srl program: Chapel architect: Go Hasegawa, Suguru Nozaki, Samuele Squassabia and Oreste Sanese

construction firm: PibaMarmi srl, Ediliza Emmevi srl area: 13.72m²

images: page 136 © Go Hasegawa and Associates pages 140 and 142 © Davide Galli

VILLA BESIDE A LAKE COVER PROJECT | INDEX PROJECT project: 2017 - 2020

location: Shizuoka, Japan

client: Private program: Single-family house

architect: Go Hasegawa and Taichi Asai structural engineer: Ohno Japan construction firm: Nakamura Contractor area: 342.13m² images: © Go Hasegawa and Associates

ICOR NISEKO project: 2019 - 2021 location: Hokkaido, Japan client: Private program: Shop + House architect: Go Hasegawa and Megumi Katayama structural engineer: Ohno Japan landscape: parsley area: 114.1m² images: pages 156, 164 and 166 © Shinkenchiku-Sha pages 160 © parsley

SETONOKI project: 2021 - 2023 location: Setouchi region, Japan client: Corporate program: Company Housing architect: Go Hasegawa, Taichi Asai and Hikari Masuyama structural engineer: Ohno Japan mechanical engineer: Enegreen project coordination: Office Ferrier constructor: PENTA-OCEAN CONSTRUCTION area: 1356.52m images: © Go Hasegawa and Associates

FLYING CARPET (installation) project: 2019

location: Mexico City, Mexico program: Rest Space

architect: Go Hasegawa, Hikari Masuyama, Taichi Asai, Henry Peters and Virginia Grimaldi

construction firm: Factor Eficiencia images: pages 180 and 186 © Jaime Navarro pages 183 and 184 © Cesar Bejar

Go Hasegawa is director of Go Hasegawa and Associates, based in Tokyo.

Born in 1977.

Master’s degree in engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2002. Establishment of Go Hasegawa and Associates in 2005, after working at Taira Nishizawa Architects.

Doctoral degree in engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2014.

Guest lecturer, Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2009–2011; Visiting professor, Academy of Architecture of Mendrisio in 2012–2014; Oslo School of Architecture and Design in 2014; University of California in Los Angeles in 2016; Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 2017 and 2019.

Awards include Kajima Prize for SD Review in 2005; Gold Prize of Residential Architecture Award from Tokyo Society of Architects and Building Engineers in 2007; 24th Shinkenchiku Prize in 2008; Architectural Record Design Vanguard in 2014.