IN TEGR A

LI G H T W E I G HT C O N CR E TE SYS T E M S

Board

President Peter Laurenson

Vice President

Karel Boakes

Board Members

Jeff Fahrensohn

Cory Lang

Alana Reid

Peter Sparrow

Administration Chief Executive Nick Hill

Finance Manager

Deloitte Private

Business Development, Marketing, and Events Manager

Belinda Dunn

Professional Development Manager Jacqui Neilson

Membership & Communications Manager Dana Mackay

National Accreditation Division Manager Alysha Franklin Event and Training Administrator Rachael Chandler Executive Assistant Vivian Menard

Advertising/Editorial Contractors Advertising/Editorial Please contact the Building Officials Institute’s National Office via office@boinz.org.nz

Design & Print

no9.co.nz

ISSN 1175-9739 (print) ISSN 2230-2654 (online)

Building Officials Institute of New Zealand

PO Box 11424

Manners Street, Wellington Level 12, Grand Annexe 84 Boulcott St, Wellington Phone (04) 473 6002

The information contained within this publication is of a general nature only. Building Officials Institute of New Zealand does not accept any responsibility or liability for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, special, exemplary or punitive damage or for any loss of profit, income or any intangible losses, or any claims, costs expenses, or damage, whether in contract, tort (including negligence), equity or otherwise arising directly or indirectly from, or connected with, your use of this publication or your reliance on information contained within this publication. The Building Officials Institute of New Zealand reserves the right to reject or accept any article or advertisement submitted for publication.

CONTENTS

MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT

2022 in Review ....... ............................... 2

MBIE

Building Code Updates ......... .............. 4 INFOMETRICS Construction Market Begins to Turn as Pressures Build ...... ...............................7 MBIE

New Regulations for Building Products .... 9

BOINZ TRAINING BOINZ Pilot Training Programme Success – Entry to BCA ........... ............. 10

BRANZ

H1 Energy Efficiency Changes .............. 11

SPOTLIGHT ON A MEMBER Spotlight on a Member - Chris Randell ... 15

BUILDING SYSTEM PERFORMANCE, MBIE BuiltReady Modular Component Manufacturer Scheme ........... ............. 18

FUTURE SKILLS How Best to Teach and Mentor Building Consent Plan Processing ....... ............. 23 STANDARDS NZ Update on NZS 3404 Revision .............24

2022 in Review

As we approach the end of another year, it is interesting to reflect on what it has meant for us personally and for the Institute. Most of you will likely describe 2022 as challenging and a continuation of matters that have stemmed from the pandemic and high consent volumes.

How we work and live has also been impacted by outcomes to supply chains from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, tight Immigration policies, many legislative changes, and rising costs of supplies. So most of us are likely looking forward to a well-earned break allowing us to spring into 2023 with renewed energy.

The effects of COVID while arguably less this year than the past two, is still causing disruption and pressures for both our homes and workplaces. The postponement again of our May conference was disruptive and created pressures as we reworked plans for another joint SBCO/Conference combination event in Rotorua. This was a great success as shown in the results of the survey we sent out. The team at the National Office did a great

job in pulling off another fantastic annual event. The highlight being the Annual Awards ceremony at the Skyline in Rotorua, where everyone saw our well deserving award winners collect their trophies. Many people also participated in the James Bond theme; most notably Kerry Walsh and the team from MBIE.

Our engagement plan to increase face to face interaction with members and branches across New Zealand also took a hit in the first half of the year, but it was gratifying to see a lift on meetings from the previous two years, with all branches coordinating member events. A total of 32 meetings were held in 2022 where a great range of presenters and face to face events were held, along with some excellent site visits and networking. A big thank you to our branch chairs and secretaries for their fantastic efforts this year. Our branch network is our lifeblood, and it survives off the dedication and initiative of our nine Branch Executive teams.

It has also been a been a busy year for advocacy and consultations for our Chief Executive and the teams that

Our branch network is our lifeblood, and it survives off the dedication and initiative of our nine Branch Executive teams.

added input into our submissions. The Institutes goal is to provide well thought out analysis and balance to the outcomes needed to improve the building environment. With more than one submission a month this year, National Office has been extremely busy. While an election year may slowdown 2023, work in this space will likely continue at pace, particularly in the areas of Building for Climate Change and the Building Consent System review.

An initiative which BOINZ submitted to the Minister for Building and Construction was, a reduction in the frequency of competency assessments for Building Control Officials under Regulation 10(2) (Accreditation of Building Consent Authorities 2006). We requested to have the Regulations changed from an annual assessment to a maximum two-yearly option which has gained traction with MBIE and they have released that option for consultation recently, hopefully to be in place by mid-2023.

Our relationship with MBIE continues to prove extremely valuable, substantial commitment and effort goes into collaborating on a regular

basis and at our events which has proved a major success as both organisations work to grow the knowledge base. Members have been particularly vocal regarding this collaborative and transparent environment enabling positive outcomes across numerous issues.

Our Training Academy also had a busy year working closely with BCAs and stakeholder firms to provide a more flexible learning offer. We launched “Entry to BCA” in the latter half of the year and in November held a function for the first group of graduates in Wellington. Our course deliveries are now a hybrid of face to face and virtual, making use of technology with huge success. New courses have been supported with the training calendar being promoted weekly through our CodeTalk E-newsletter. The efforts of the training team and those who have contributed to the reshaping of our courses over the last few years are very much appreciated. As we move into 2023 members can look forward to continually improved content and more courses.

We also plan to introduce a revised (fit for purpose) constitution to members

which is on track and information will be available in the New Year.

I would like to wish you all a very relaxing and safe holiday season and look forward to catching up with you in 2023. Thank you for your continued support.

President

President

Building Code Updates –A Year in Review

Updating the Building Code

The Building Performance team at MBIE updates the acceptable solution and verification method Building Code documents regularly. We do this to ensure that the system is effective and keeps pace with modern methods of construction, products and technologies, and that our buildings are safe, healthy and durable.

We know these changes will have a direct impact on the work that you do, so it’s really important that you find out about them as early as possible and get the opportunity to let us know what you think. When we are proposing changes to the Building Code regulations or to the acceptable solutions and verification methods, we run a consultation first. This is your chance to submit feedback on the proposed changes, and we are keen to hear from you.

Recent consultations

It’s fair to say that the 2021-22 period has been a busy time for building consenting. There was a record number of 51,015 new homes consented in the year to May 2022, and the sector continues to feel pressures as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In May 2022 we consulted on changes to several acceptable solutions and verification methods. The proposed changes focussed on plumbing and drainage, protection from fire and structural stability of hollow-core floors. In early June 2022, we ran a second consultation on a proposed six-month extension of the transition period for the insulation requirements in new housing from the 2021 Building Code update. This was to provide the building and construction sector more time to prepare for the increase in insulation.

These consultations received record numbers of detailed submissions, which provided valuable input, and we wanted to thank you for taking the time to do this.

Summary of Building Code consultations

We know that there has been a lot of information to get up to speed with recently. Here are some of the key points from the Building Code updates that we wanted you to be aware of.

2022 Building Code updates

In 2022 we consulted on changes for plumbing and drainage, protection from fire and structural stability of hollow-core floors. You can read the proposal documents on our website www.mbie.govt.nz/have-your-say/ building-code-update-2022

This consultation closed on 1 July 2022 and received over 100 detailed submissions and comments.

The proposal that received the most interest was the changes to protection from fire for residential buildings with 58 submissions and over 100 pages of comments on the proposal. The plumbing and drainage proposals for lead in plumbing products and water temperatures also received a significant number of responses.

The Building Performance team have made decisions on two parts of the proposed changes to the Building Code - lead in plumbing products, and the structural stability of hollow-core floors.

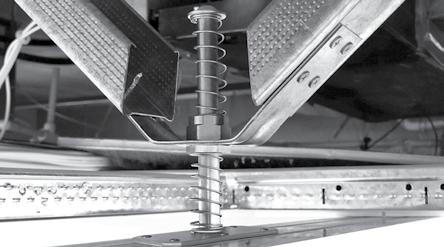

Decision on Hollow-core floors

The Building Performance team has removed the deemed to comply pathway in B1/VM1 for the design of the supports for hollow-core floor systems. We believe removing this deemed to comply solution from B1/VM1 will minimise the chance of poorly designed systems being specified in new building work.

It will take time to revise the technical documentation and build awareness of the change. Therefore, the amended Verification Method B1/VM1 will be published along with other documents in November 2023. This change for hollow-core floor systems will take immediate effect when published – there will be no additional transition period. We are announcing this decision prior to the publication of the revised verification method to provide certainty and direction to the sector.

In the interim period prior to November 2023, structural engineers looking to use these types of floors or provide advice to building owners should review the advice on hollowcore floors issued by Engineering New Zealand, the Structural Engineering Society New Zealand and the New Zealand Society of Earthquake Engineering.

Advice on hollow-core floorssesoc.org.nz

Decision on lead in plumbing products

The Building Performance team is amending Acceptable Solution

G12/AS1 to limit the maximum allowable content of lead permitted in plumbing products. The amended document will limit the maximum lead content of any product that contains copper alloys, intended for use in contact with potable water for human consumption. This includes products such as pipe fittings, valves, taps, mixers, water heaters, and water meters. The transition period for this change will end on 1 September 2025.

As the transition period extends to 2025, the revised acceptable solution will be published in alignment with the rest of the plumbing and drainage updates in November 2023.

By announcing this decision prior to the publication of the revised acceptable solution, our aim is to provide certainty and direction to the sector and give manufacturers and suppliers additional time to implement the required change to the effected plumbing products.

Read information about what products are affected

Read the summary of the decisions on lead in plumbing products and the structural stability of hollow-core floors on our website www.building.govt.nz/bcu22

Decision on other proposals

Due to the breadth of in-depth submissions received for the 2022 consultations, we will announce the remaining decisions prior to publishing the Building Code acceptable solutions and verification methods in November 2023.

This additional time is required to thoroughly work through the submissions and ensure all points of view are considered. This timeframe will also allow us to prepare the necessary supporting educational material such as guidance documents, learning modules and webinars.

2021 Building Code updates

In 2021 we published updated acceptable solutions and verification methods for building code clauses B1, E2, G7 and H1. The transition period for the 2021 Building Code updates ended on 2 November 2022. This means that building consent applications submitted on or after 3 November 2022 that use one of the updated acceptable solutions or verification methods as a means of compliance should now use the most recent versions of the documents.

You can access these on our website at www.building.govt.nz/buildingcode-compliance

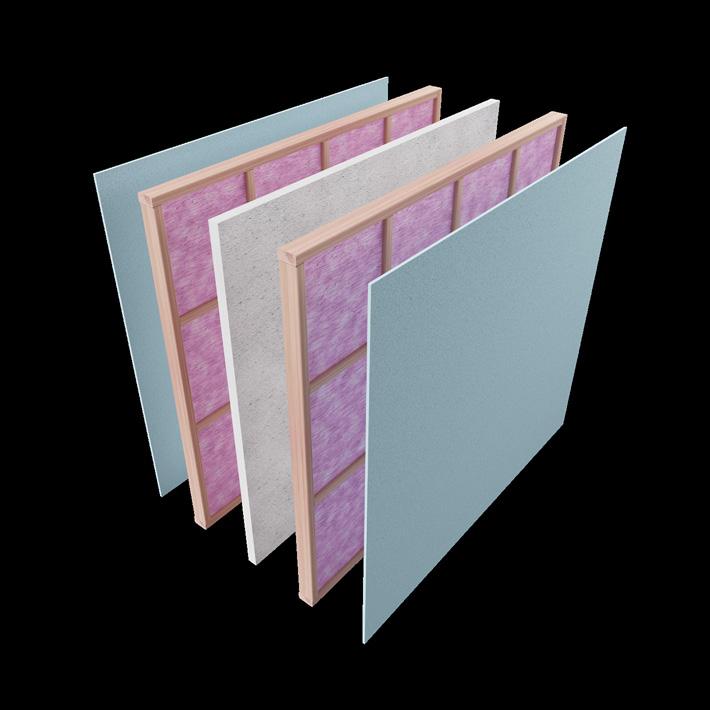

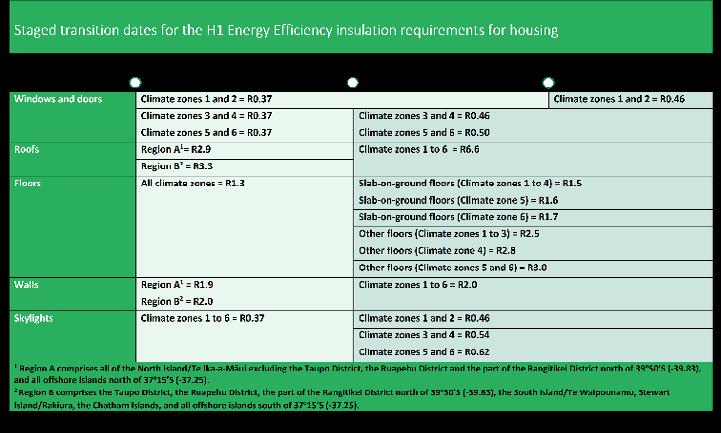

Staged implementation for H1 insulation requirements for housing

In November 2021 we also announced the biggest energy efficiency changes to the Building Code in over a decade which aim to reduce energy needed for heating residential homes by approximately 40 per cent. We published updates to the acceptable solutions and verification methods for H1 Energy efficiency.

Find these, along with a summary of the changes on our website at www.building.govt.nz/building-codecompliance/h-energy-efficiency/h1-energy-efficiency/

The changes to the H1 documents are effective now. The revised documents should be used to show compliance with the Building Code and there is a staged transition for housing as outlined in the Figure.

There will be an increase to the wall, floor and roof insulation performance requirements for new building work in housing on 1 May 2023. Requirements for window and door insulation in housing also see an increase on 1 May 2023 and will be required to meet the final increased performance levels in all parts of the country by 2 November 2023.

H1 education modules

To help people understand the updated H1 requirements, the Building Performance team have created two new learning modules covering insulation, energy efficiency and climate zones.

Module 1 is aimed at homeowners and the general public. It helps you understand why insulation is important in buildings to increase energy efficiency and the benefits of installing better insulation. It explains how to identify the climate zones that different parts of the country fall into and the background to the new requirements for houses that will apply from May next year.

Module 2 teaches you about the different compliance pathways for the Building Code’s energy efficiency requirements, including how to choose the appropriate acceptable solution or verification method for your building. It covers how to choose the compliance pathway for housing and other building uses.

Modules 3 and 4 are under development and will be published later this year.

The Building Performance Learning Centre has a wide range of free learning modules designed to help people from all over the sector improve their knowledge across different building-related topics.

Find building system learning modules at learning.building.govt.nz

Stay up to date with Building Code updates

We know that there have been a lot of different things to get up to speed with, but we are committed to working alongside the building and construction sector to ensure successful implementation of these important changes.

You can find out about consultations on changes to the building code, acceptable solutions and verification methods and stay up to date with changes when they come into effect by subscribing for updates on our website www.building.govt.nz

written by Liz Ashwin, Senior Advisor Information and Education, MBIE

Construction Market Begins to Turn as Pressures Build

Headwinds are hitting the broader construction sector, as rapidly rising interest rates, falling house prices, high build costs, labour shortages, and delays all combine to dampen enthusiasm for further building work.

House prices head lower

The slump in house prices so far in 2022 has been strong, with prices in October 2022 down 12% (seasonally adjusted) from the November 2021 peak according to Infometrics analysis of REINZ data.

The fall in house prices is broad-based. Although house prices have dropped the most so far in Wellington and Auckland, house prices sit below October 2021 levels in 14 of New Zealand’s 16 regions. Housing markets in the northern and southernmost regions have experienced the most modest price corrections in the last 12 months, with house prices in Northland and Southland up just 1.6% and 3.4% from October 2021 respectively.

House sales fell 9.6% (seasonally adjusted) in October. Sales activity across every region in New Zealand also remains lower than this time last year, with house sales in Auckland, Canterbury, and Wellington down 42%, 34%, and 18% respectively from October 2021. Sales in the last six months have consistently sat between 4,500 and 5,500 houses per month. House sales were last this low consistently through 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis and then again in 2010 and 2011.

Persistent and pervasive inflation is demanding a strong and rapid response from the Reserve Bank, with floating mortgage rates already above 7% and special 1-year fixed rates above 6%. The Reserve Bank is forecasting a peak official cash rate of 5.50% in 2023, and Infometrics is expecting something slightly stronger of 5.75% by mid-2023. These forecasts will see mortgage rates continue to rise in early 2023, putting further downwards pressure on house prices.

Building levels set to fall

New dwelling consent numbers are expected to decline sharply across New Zealand over the next two years. The backlog of work and capacity constraints might slow the rate of completion and keep work put in place at high levels for longer than consents, but there is an increasing risk of consented projects being cancelled given weaker demand conditions.

Residential consent levels in October 2022 were down 12%pa, the largest monthly fall since 2016, excluding the COVID-19 lockdown in April 2020. Importantly, the divergence in types of buildings being consented continues.

Standalone house consents have been clearly trending downwards since early 2022, and with attached dwellings continuing to grow strongly throughout most of the last year, standalone houses are comprising a smaller proportion of residential consents.

Townhouse consents in October were up 17% from a year ago, which is a stronger result than the -5.4% and +6.2% results recorded in August and September respectively. However, growth remains well down from the 51% growth averaged over the year to July 2022. This slower growth reinforces widespread anecdotes of developers starting to shy away from new projects. We expect numbers to continue softening as house prices trend downwards and rising interest rates undermine the affordability of new builds.

However, we expect townhouse consents to hold up better than other building types. Our forecasts see the annual townhouse consent total retreat from almost 21,000pa in 2022 to about 12,200 by mid-2024. Despite the large decline, this outlook sees townhouses maintaining a share of almost 40% of all new dwelling consents over the medium term. Persistently high house-price-toincome ratios, alongside scope for more intensification due to the

government’s Medium Density Residential Standards, pose upside risks to our forecasts of townhouse consents.

High interest rates, affordability constraints, and incentives for investors to purchase new homes will also favour construction of attached dwellings rather than standalone houses.

Standalone house consents are expected to continue declining, and by the end of next year, we expect annual house consent numbers to have dropped 33% from their mid2022 total and be at their lowest level since 2013. We predict that house consent numbers will drift lower in the second half of our forecast period as the government’s changes around zoning and density regulations enable more intensification to take place in the main urban centres.

Brad OlsenTechnical help on hand - we are just a phone call away.

Get the information right when you need it, for free.

A professional team of hugely experienced builders and building engineering experts are available by phone, online or face-to-face.

GIB ® technical literature is easy to find and download.

Independently tested and appraised systems for complete peace of mind.

For more information call the GIB® Helpline 0800 100 442 or visit gib.co.nz Technical Helpline 0800 100 442

New Regulations for Building Products

New regulations have been made by the Government to ensure a minimum level of information is provided about certain building products, increasing confidence in their use, and supporting better and more efficient decision making.

Key dates

The new regulations were made on 7 June 2022 and will come into force on 11 December 2023. This gives people 18 months to prepare to meet their obligations.

Who do the regulations apply to?

The regulations require building product manufacturers and importers to publicly disclose a minimum and consistent level of information about their building products.

Wholesalers, retailers, and distributors will need to check that the required information is available for the building products they sell or distribute.

Why were the regulations made?

Building products contribute to safe and durable buildings and yet until now, the level and type of information provided by manufacturers and importers has been variable.

Information on these products will help designers, builders and consumers choose the right products, install them in the correct way and make informed decisions about using alternative products where there are product shortages.

Building consent authorities will have adequate information to enable them to be satisfied on reasonable grounds that building work, the building products used will comply with the performance requirements of the Building Code. This should result in fewer requests for information, and therefore faster processing times.

In addition, the regulations will ensure homeowners are given the information they need to make good decisions about products, and use and maintain them as intended.

What products do the regulations apply to?

The regulations only apply to ‘designated’ building products. These are products that are required for the building to comply with the Building Code.

There are 2 classes of designated building products, with different information requirements for each:

• Class 1: batch or mass-produced products that are typically available for retail or wholesale purchase. For example: cladding products or systems, mechanical fixings, insulation products, internal lining products, structural wood-based products, sanitary plumbing and drainage products.

Class 2: custom-made lines of products that are made to order to client specifications. For example: external window joinery and doors that have been customised to the specifications of individual clients, and customised concrete mixes for a specific building or application.

What information must be provided?

Manufacturers or importers of designated building products will have a responsibility to collate and produce the required building product information and disclose it online to the public. Most manufacturers and importers already have this information, but it may not be disclosed all in one place or in a way that is accessible to the public.

Information requirements to be displayed online include:

• the name and a description of

the product (or product line from which the product is customised) and its intended use

• a product identifier (in most circumstances)

• the legal and trading name of manufacturers and, if applicable, importers

a statement specifying the relevant clauses of the Building Code and how the product is expected to contribute to compliance, as well as any limitations on the use of the product

any design, installation and maintenance requirements

• either a statement that the product is not subject to any warnings or bans or a description of warnings or bans applicable to the product.

See the regulations for a full list of the required information.

Where can I find more information?

The Building Performance team at MBIE is developing resources including information and guidance to help manufacturers, importers, wholesaler, retailers, and distributors with their responsibilities understand the changes.

Find out more about the new regulations: https://www.building. govt.nz/building-code-compliance/ product-assurance-and-certificationschemes/building-productinformation-requirements/

Conor Topp-Annan

Senior Advisor, Design and Implementation

Design and Implementation Building System Performance

BOINZ Pilot Training Programme Success –Entry to BCA

Earlier this year we launched Entry to BCA training in two parts and just recently we had five students’ complete part two which took them 12 weeks. At the end of it, they got to celebrate this achievement.

The need for this programme was identified and designed in conjunction with Building Control Authority (BCA) Managers with the purpose of quickly upskilling those in their new role at a BCA. Specific and relevant content was delivered online and in person at a Residential 1 level over a 12-week period, from August to October, with feedback throughout from both the managers and participants.

Congratulations was the order of the day for our Entry to BCA – Part two Graduates on Tuesday 22nd of November.

After successfully completing this Pilot programme, the group flew and drove from around the country to join us in Wellington for a final day of learning. The day concluded in a graduation ceremony that wrapped up the successful Entry to BCA Pilot programme.

The celebration day began with a morning tea at Niche Modular homes where Technical Manager, Nico Patchay, provided the group with a presentation and factory site tour of Niche Steel Framed Modular

Homes. This presentation provided an overview of the Niche business with a particular focus on best practice and highlighted to the group the importance of relationships and effective communication between all parties. After the factory tour, time was set aside for a Q&A session where the group learnt about the consenting and inspection process, from factory to delivery onsite, of NICHE modular buildings.

We then travelled to BRANZ for our second site visit of the day. Dr Chris Litten, General Manager of Research, spoke on the history of BRANZ, future plans, and the new building developments onsite, currently under construction. Peter Whiting, Fire Testing Team leader, then spoke about brand and product testing along with verification methods and the group came away with a thorough understanding of the key role BRANZ plays supporting the built environment.

Finally it was back to the BOINZ National office in Wellington Central where we were joined via zoom by managers and team members of the graduates for the Graduation presentation.

CEO Nick Hill and Professional Development Manager Jacqui Neilson presented the participants with their certificates of completion and the graduates spoke of their learning

experience and value the programme had provided. A strong theme of self -confidence and enthusiasm came through. The graduates attributed this to a shared collaborative learning environment with a group of individuals who were all at a similar stage in their development journey as a Building Control Official (BCO) and to the relevant learning content delivered at a level that could be practically applied to their daily duties.

Congratulations to Emily Harwood (Tasman DC), Juliette Gigg (South Wairarapa DC), Janette O’Leary (Rangitikei DC) , Carl Sherwood (Hurunui DC) and Partha Patra (Timaru DC) on successful completion of our Entry to BCA Pilot Programme.

It has been an excellent journey of learning for everyone involved and our pilot group and their managers have helped shape and further develop this programme which we are excited to offer again in 2023.

H1 Energy Efficiency Changes – Common Challenges Part 1

BRANZ is receiving numerous queries from the building industry about the new H1 Energy efficiency requirements. In this two-part series, we answer some of the most common questions. Part 1 focuses on windows and doors, and Part 2 will focus on secondary insulation layers and concrete slabs.

Q. How do I specify windows that comply?

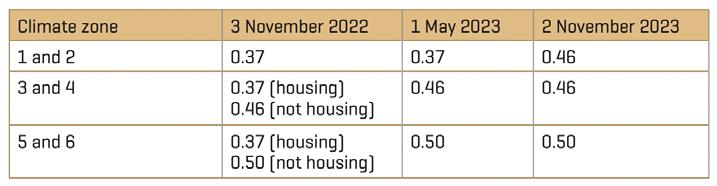

Under H1/AS1 and H1/VM1 5th edition amendment 1, there is a two-step transition for all windows and doors in climate zones 1 and 2 (the upper North Island) under the schedule method:

• From 3 November 2022, the minimum R-value is R0.37

From 2 November 2023, the minimum rises to R0.46.

For housing only, in zones 3-6, there is also a two-step process:

From 3 November 2022, the minimum R-value is R0.37 for climate zones 3-6.

From 1 May 2023, the minimum rises to R0.46 for climate zones 3 and 4.

From 1 May 2023, the minimum rises to R0.50 for climate zones 5 and 6.

It is possible to reduce the construction R-values of windows and doors below the levels required in the schedule method by instead

using the calculation or modelling methods to demonstrate Building Code compliance. The calculation method is explained in H1/AS1 and the modelling method in H1/VM1.

These methods allow the use of windows and doors with lower construction R-values if the construction R-values of other building elements – floor, walls or roof – are increased to compensate.

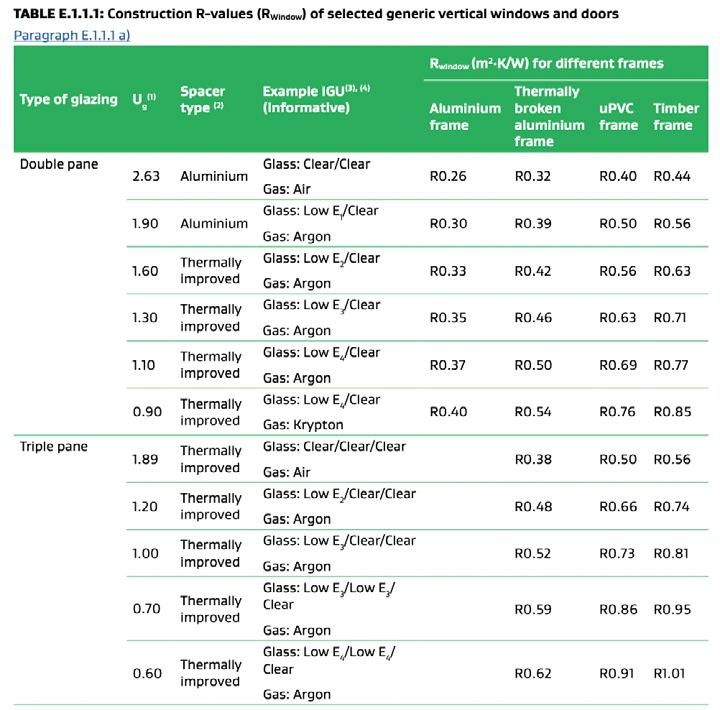

Q. How do you know that a particular set of windows will comply with the Building Code construction R-values?

The requirements for working out the construction R-value of windows,

doors and skylights are given in Appendix E in H1/AS1 and H1/VM1.

Table E.1.1.1 for vertical windows and doors in Appendix E in H1/ AS1 is to be used for housing only. For other building types, use the calculation method in H1/VM1.

The table does not apply to opaque doors or opaque door panels – see the next question.

The table for vertical windows cannot be used for skylights. Ask skylight suppliers for details.

Q. How do I find out more about doors, including opaque doors?

Windows and doors are treated together H1/AS1 and H1/VM1

5th edition amendment 1. The requirements for windows and doors cover opaque doors or doors with opaque panels.

The schedule method

Table 1. Vertical window and door R-value requirements under the schedule method

The schedule method currently requires (since 3 November 2022) a minimum construction R-value for

windows and doors in housing in all climate zones of R0.37. This changes in several steps:

On 1 May 2023, the minimum R-value goes up to R0.46 in zones 3 and 4 and R0.50 in zones 5 and 6. (These are the current requirements for buildings up to 300m2 other than housing.)

On 2 November 2023, the minimum R-value goes up to R0.46 in zones 1 and 2 for housing, and all buildings up to 300m2.

One of the restrictions with the schedule method is that you can only use it if the opaque door area is no more than 6 m2 or 6% of the total wall area, whichever is greater. If your opaque door area exceeds this, or you want to be able to install windows and doors with lower thermal performance than the schedule method requires, you must use the calculation or modelling methods.

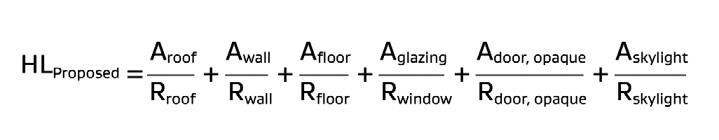

The calculation and modelling methods

The calculation method in H1/AS1 and the modelling method in H1/ VM1 can be used to reduce any of the elemental schedule method figures if insulation in other building elements (unheated floors, walls or roofs) is increased to compensate. The calculation method can only be used on buildings where glazing makes up 40% or less of the total wall area, but the definitions of ‘glazing area’ and ‘wall area’ both exclude opaque doors or door panels.

Clause 2.1.3.6 in H1/AS1 shows where opaque door areas fit into the calculation method heat loss equation for the proposed building.

In the equation, HLProposed is the heat loss of the proposed building, Adoor, opaque is the opaque door area in m2 and Rdoor, opaque is the construction R-value of the opaque door area.

In the equation, the opaque door area is the total area of opaque doors and opaque panels of doors in the thermal envelope, including frames and opening tolerances. If there are two separate opaque doors with different levels of thermal performance, you can treat them separately, splitting them into two parts in the equation.

Acceptable methods for determining the construction R-values of opaque doors and opaque door panels are given in NZS 4214: 2006 Methods of determining the total thermal resistance of parts of buildings.

Clause 2.1.3.9 in H1/AS1 states that where the construction R-value of a building element is not known, default construction R-values of 0.18 m2 ·K/W for an opaque building element must be used in the heat loss equation for the proposed building.

For the modelling method, section D2.4 in H1/VM1 states that in the reference building:

a. The opaque door area that is no more than either 6 m2 or 6% of the total wall area (whichever is greater) shall have the same construction R-value as the reference building windows (or higher at the designer’s discretion); and

b. Any remaining opaque door area shall have the same construction R-value as the reference building wall.

A comment in E.1.2.3 of H1/VM1 states that the door construction R-value includes the effects of the frame, any glazing, and any opaque panels.

You can find more guidance around specifying windows and doors in this free, online webinar presented by experts from BRANZ, WGANZ and MBIE: https://www.branz.co.nz/shop/ catalogue/webinar-h1-windowsdoors-and-skylights_1041/

More guidance can also be found in this BRANZ bulletin:

Introducing the H1 Hub – a new, smart, one-stop search tool

BRANZ and partner organisations are committed to helping you make the transition to the new building design and construction requirements under the Acceptable Solutions and Verification Methods for New Zealand Building Code clause H1 Energy Efficiency.

Our H1 Hub is a one-stop search tool that provides search results across all partner websites on H1related content.

that BRANZ, and its partners, have developed to help designers, builders and BCAs to manage the H1 transition.

The transition to the new H1 requirements is an important step in our journey towards a netzero carbon built environment by 2050.

https://www.branz.co.nz/shop/ catalogue/bu670-specifyingwindows-and-doors-under-h1_1015/

The Hub is a collaborative initiative between BRANZ, MBIE, ADNZ, NZIA, WGANZ, IAoNZ, NZGBC, and FTMA. It’s one of many tools, guidance and advice

If your organisation has resources and or information about H1 and would like to be part of this Hub, please email us: website@branz.co.nz.

Visit the H1 Hub: h1hub.branz.nz/H1Hub/s

THE NEW KIDS ON THE BUILDING CONTROL BLOCK INTRODUCING

Attention Building Control Managers!

Are you struggling to meet statutory KPI s, or need a hand with other compliance tasks?

Give us a shout at info@dnacompliance.co.nz we are ready to help.

Heads up Building Control Superstars!

Are you keen to join our team?

If you’re a good sort and have skills and experience in any area of building control including processing, inspections, BWOFs, code compliance certs, CPUs or COAs, we would love to hear from you. Send your CV and cover letter to careers@dnacompliance.co.nz or jump on the blower and have a chat with Aimee or Neil. We will make you an offer you can’t refuse. www.dnacompliance.co.nz P: 03 595 1179 or 03 595 1173

TRIBOARD

With mainstream products in short supply, Triboard wall linings are finding favour with residential and commercial builders. Triboard stands out as a premium wood solution with proven wall bracing values.

Triboard is composed of engineered strands orientated in such a way as to maximise strength and durability with an additional MDF fibre surface giving a smooth paint ready finish.

Certified uniform strength throughout its core gives Triboard Panels excellent wall bracing capabilities.

Triboard bracing information has been developed from tests carried out in the Timber Laboratory of SCION. For Triboard bracing details go to www.jnl.co.nz/product/triboard/ Brochures and Specs or scan the QR code.

Spotlight on a MemberChris Randell

Chris Randell grew up in Sydney, Australia and has been in the building industry in some capacity for over 40 years.

His technical education started at TAFE in Australia with a certificate in Carpentry and Joinery. Five years later, Chris was back for another qualification and achieved his Certificate in Building Supervision (Clerk of Works) after three years

While on a cruise around the pacific islands, Chris met his future wife and later decided to move to what Chris calls ‘the most peaceful place on earth’ – Dunedin, New Zealand. They wanted to get away from the hustle and bustle of city life in Sydney and move to New Zealand to start a family.

After moving from Sydney to Dunedin in 1993 Chris joined Amalgamated Builders Limited as their Construction Foreman and stayed for over 9 years. Chris moved into Building Control In 2002 when he joined the Dunedin City Council (DCC) as a multi-skilled Building Control Officer (BCO). After six years at the Council, he moved into the role of Building Compliance

Officer. Then in 2014, he left to establish his own business - Building Compliance Solutions Ltd where he still is today.

We thought we would ask Chris a few questions about growing up, moving to NZ and his career in the building industry.

1. How did coming from a carpentry/joinery background help you with being a BCO?

That background provided me with knowledge of construction products, techniques, methods, loads, forces, and construction sequencing, all of which are essential for a BCO to understand. My prior experience gave me an advantage.

2. Where did you grow up?

I grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney in a suburb called Auburn. Up to 1970, it was a quintessential Australian place. As time went on it became a very multicultural suburb in the 70s and changed rapidly. Auburn is now one of Australia's drive-by shooting capitals, and it's a tough

place to live. In the nine years before moving to New Zealand, I was building in the eastern suburbs which was challenging for different reasons.

3. What made you move to NZ?

My wife is from Dunedin, and we knew we would have family and support which was a large part of the move as we were planning on starting a family.

4.

When I started at the Council it was 2002 and we were working under the 1991 Building Act. This was vastly different to the 2004 Building Act, although you would think it would be the same thing. Under the 1991 Act, the Building Inspector on the site was responsible for making Building Code Compliance decisions. There was nothing expressly stated about the building consent complying with the Building Code, and there was nothing specifically stated about building in accordance with the building consent.

That all changed with the 2004 Building Act. The building consent had to demonstrate compliance with the Building Code, and you had to build in compliance with the building consent. That and other changes to the Building Act meant that our roles changed. The other significant change I saw was the introduction of BCA accreditation. Before this, BCAs did things their own way and their way did not always align well with the Building Act or Code.

5. What has been the most interesting or challenging project you worked on to date regarding building surveying?

The rebuild of the Farmers building in Dunedin. I processed the building aspects of the building consent and did all the inspections of the building aspects. It was a large job that required a lot of groundwork in the form of piling, specified systems, and large building techniques. Being a commercial job there was time pressure which meant we had to be available at short notice to do inspections. It was a good thing that the site was 150 metres from the DCC office.

This project was interesting in terms of access and facilities for people with disabilities. What I found was what you saw on the plans, while it was being built, you couldn’t always see these things like isolated steps or locked doors that shut off access to accessible toilets. Those types of issues were challenging but it was a good, fun job.

6. What made you decide to move from being a Construction Foreman to a Building officer?

A couple of things happened, I was working on a job of three motels and would often have two – three inspections a day on different aspects. One of the Inspectors approached me and said they were looking for a Building Inspector and that I should think about it.

Around that time there was a lot happening and things were getting so much harder in the building industry. The construction times were getting shorter, the projects were getting more complex, and the demand and expectations of designers and clients were increasing.

The next day I saw that same Inspector, and he gave me forms to fill out for the position. That was the point where everything changed. I thought it couldn’t be that hard, so I completed the application and sent it in.

I remember the interview clearly, there were four guys with shorts, long socks with their pens tucked in their socks, and clipboards writing down all my answers. They grilled me for about two hours. I didn’t hear anything about my application for about three weeks. I was starting to think I missed out on the role and my future was always going to be on building sites. Then I got the call, and the rest is history!

7. What advice would you give to someone just starting their career in Building Control?

Have patience, perseverance, and willingness to learn. The learning never

stops, I don’t know anyone who knows it all, I certainly don’t. You learn new things all the time.

8. Next year our conference theme is ‘Building Competency and Capability’, what is the most pressing concern you see in that area moving forward?

To make sure the building work complies with the Building Act and the Building Code, one needs to be knowledgeable and understand the Building Act and how the Building Code works. It is important to understand the distinction between acceptable solutions and the Building Code and remember it is the Building Code and not the acceptable solution that we should be applying. There needs to be more focus on developing critical thinking skills.

The second is continual learning and professional development. I think people get comfortable in their roles, reach a level of competence and their professional development stops or at least slows down. It shouldn’t matter what level you are at, keep the learning going.

9. What do you do to relax outside of work?

I enjoy things like fishing, home distilling, boating, and motorcycling. Having a beer and playing the guitar is also a great way to wind down.

What major changes did you see in the 10 years you worked as a Building Officer at Dunedin City Council?

ICC Oceania - Providing Building Safety Solutions

The International Code Council (ICC) is bringing its diverse services, skills and experience to Australia and New Zealand to help promote building safety, provide practical solutions for practitioners who work in the building sector, and collaborate with local authorities.

As part of this program, we have established an ICC Oceania office to help broaden the awareness, understanding of and access to the International Code Council’s Family of Solutions.

Leading the World in Building Safety - The International Code Council is the leading global source of building safety solutions that include product evaluation, certification, accreditation, and technology. The International Code Council’s solutions are used to ensure safe, affordable, and sustainable communities and buildings worldwide.

What We Do - The International Code Council provides expert advice that takes into account local building requirements to help develop Performance (Alternative) Solutions. Our experts take the effort needed to understand the unique needs of each partner, user or client. ICC offers the following resources:

¾ The International Codes (I-Codes) and Standards – The International Code Council is the developer and publisher of the most recognised and adopted codes and standards for buildings globally. While not for direct application in Australia and New Zealand, the I-Codes and ICC Standards may contain evidence that in Australia and New Zealand can be used for the purpose of a Performance (Alternative) Solution through an expert opinion provided by one of ICC’s services assessing equivalence to local requirements.

¾ Product Certification – ICC Evaluation Service (ICC-ES) maintains accreditation for product evaluation to Australian and New Zealand building codes in our scope of services. Equivalence Reports produced by ICC-ES can be used as evidence of compliance to the Building Code of Australia as well as the New Zealand Building Code.

¾ WaterMark Certification - The ICC-ES Plumbing, Mechanical and Fuel Gas (PMG) program is accredited by JAS-ANZ to provide plumbing product certification for WaterMark under the Plumbing Code of Australia.

¾ Testing and Evaluation – In conjunction with ICC’s ILAC-recognized product testing group, NTA, ICC-ES provides product testing, inspection, design review and evaluation for plumbing and building products, including off-site/modular construction.

¾ Accreditation – The International Code Council’s International Accreditation Service is an IAF member with expertise in verifying the technical competence and processes of bodies such as building departments, professional membership-based organisations and quality assurance processes to ISO standards.

¾ Technology/Digitization – The International Code Council offers building code solutions that digitally link planning ordinances, land-use zoning, building codes, planning and building approval documentation and other essential content for the procedures and service platforms utilized by local government and building officials.

BuiltReady Modular Component Manufacturer Scheme

Offsite construction, also known as prefabricated or modular construction, is on the rise in Aotearoa New Zealand as innovation, sustainability, efficiency and productivity increases are sought in the design and construction industry. Prefabricated panels, 3-D pods and whole buildings are manufactured in factories, transported and then installed on site.

While offsite construction is complementary to traditional

construction methods, there are some key differences in the design, manufacturing and installation processes for prefabricated buildings or components that has meant this type of construction has not historically been a straightforward fit with the building consent process.

To encourage the use of offsite construction and provide a more streamlined pathway through the consent process, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) has recently

implemented the new voluntary modular component certification scheme called BuiltReady.

BuiltReady will allow modular component manufacturers to be certified and registered to design and/ or manufacture modular building components that will be deemed to comply with the Building Code. In most cases, the scheme will allow for faster, more consistent building consent processing and reduced inspections, which will aid in reducing costs and onsite building time.

What is the BuiltReady scheme?

Under the BuiltReady scheme, the entire prefabricated construction process from design (where applicable), to manufacture, assembly, transportation, and onsite installation of modular components will be assessed and certified.

The BuiltReady scheme operates under the legislative framework provided by the Building Act 2004, Building (Modular Component Manufacturer Scheme) Regulations 2022 and the BuiltReady scheme rules (refer to Figure 1 below). The Regulations and scheme rules commenced on 7 September 2022.

The process flow diagram below shows how the BuiltReady framework works.

Certification bodies accredited under the BuiltReady scheme will be responsible for certifying manufacturers. To ensure they are competent to perform this function, certification bodies must be both accredited by the appointed accreditation body and registered with MBIE before they can perform their functions under the scheme. Similarly, manufacturers must be certified by an accredited and registered certification body and then registered with MBIE before they can utilise the scheme’s compliance pathways.

BuiltReady scheme rules

The BuiltReady scheme rules are secondary legislation made by the Chief Executive of MBIE. They

align with the Building Act and Regulations, and provide much of the operational detail for the BuiltReady scheme.

Both the Building Act and the Regulations require scheme parties to comply with the scheme rules. Failure to do so could result in suspension or revocation of accreditation, certification, or registration.

The scheme rules apply to all scheme parties, including:

• the accreditation body

• accredited modular component manufacturer certification bodies (MCMCBs) whether or not they are registered, and certified modular component manufacturers (whether or not they are registered).

Certification

BuiltReady certification does not just cover the manufacture of modular components but the entire endto-end process, including design (if applicable), transportation, storage, and on-site installation. A certification body will evaluate a manufacturer’s policies, procedures, and systems to ensure that the design and/or manufacture of modular components is done competently and reliably to a standard that complies with the Building Code. These systems include:

• an appropriate quality plan and quality management system documented design and/or manufacturing processes

• employee and contractor systems including competency and training requirements, and complaints and disputes processes.

Ongoing monitoring of a manufacturer will include regular third-party audits and installation inspections.

A manufacturer can apply for BuiltReady certification in one of two ways:

• design and manufacture –manufacture modular building components to a Building Code compliant design that the manufacturer has developed or adapted themselves or

• manufacture only – manufacture modular building components to a Building Code compliant design.

The three types of modular components that can be certified are defined by the Regulations and include:

• prefabricated frames and panels. These include open frames or trusses, or enclosed frames or panels. Examples include floor, wall and ceiling panels or cassettes, frames and trusses, panelised building systems, and structural insulated panels (SIP panels). Prefabricated frames and panels may also include mechanical, electrical, or other systems.

• prefabricated volumetric structures. These are threedimensional products that are comprised of one or more prefabricated frame or panel products described above. Examples include laundry and bathroom pods, and types of modular units. They may also include mechanical, electrical or other systems.

• prefabricated whole buildings (ie the entire building is manufactured off site).

Registration with MBIE

The registration process for an accredited certification body includes a declaration regarding relevant conflicts of interest (including confirmation that the applicant has written procedures for transparently and appropriately managing any identified conflicts of interest) and a fit and proper person assessment.

The registration process for a certified manufacturer includes a declaration regarding relevant conflicts of interest (as above), a fit and proper person assessment and an adequate means assessment.

Modular component manufacturers and the consent process

Once certified and registered, a manufacturer may issue a manufacturer’s certificate to accompany a building consent application and a second certificate to accompany a code compliance application for the modular components it produces that fall within its scope of certification.

For manufacturers certified to design and manufacture, the manufacturer’s certificate will cover both the design and manufacture of the modular component included in the building consent and is evidence that the modular component complies with the Building Code.

The following process flow diagrams show how the modular component consent process works:

not covered by a manufacturer’s certificate must also still be approved by the building consent authority as per standard practice. Parts of the design may be deemed to comply through other schemes such as MultiProof for whole buildings, or CodeMark for building products or methods contained within the

assess or inspect any work covered by the manufacturer’s certificate except where there are connections with site specific work. This should significantly reduce processing and inspection costs and time for modular components produced by a manufacturer certified to manufacture only.

Restricted building work

The manufacture only pathway is for modular components where a manufacturer is only certified to manufacture modular components under the scheme. No aspects of the design are included within their scope of certification and the design must therefore be assessed by the building consent authority to ascertain whether it complies with the Building Code. Any building work

overall design (if this pathway is used in conjunction with the MultiProof scheme for a whole building, the building consent authority consent timeframe is reduced to ten working days).

Although the manufacture only path is not a deemed to comply pathway like the design and manufacture path, a BCA will not

For traditional construction, any Licenced Building Practitioner (LBP) who carries out restricted building work must provide a Certificate of Design Work or Record of Building Work. However, the Building (Definition of Restricted Building Work) Order 2011 has been amended to specify that the order does not apply to building or design work carried out by a registered manufacturer designing or manufacturing a modular component off site. All relevant records related to Licenced Building Practitioner work by a registered manufacturer will be part of the manufacturers’ own quality management systems, ensuring there is a record of building work for that building.

A Record of Building Work is still required for site works such as foundations/subfloor framing and any work that falls outside what is specified in a manufacturer’s certificate. A Certificate of Design Work will be required if a manufacturer is certified to only manufacture modular components.

Where can I find more information?

BuiltReady will be open for applications from manufacturers from mid-2023. A register of certified manufacturers will be available at www.building.govt.nz

The BuiltReady pages at www.building.govt.nz contain detailed information about the scheme including scheme rules and guidance material.

Please send your enquiries to builtready@mbie.govt.nz

Article written by Amanda Macauley

Article written by Amanda Macauley

PROGRAMMES ON OFFER :

NZ Diploma in Building Surveying (In employment) (Level 6)

The ‘no-brainer’ for your new technical hires who do not currently meet Regulation 18 requirements. The most relevant, suitable, and convenient programme for the role of a Building Control Officer or an equivalent technical role. The programme is delivered through a combination of face-to-face block courses, online sessions, and self-study on our Future Skills Moodle platform.

*Pending confirmed enrolments.

STARTS: Hamilton, Christchurch and Dunedin: 24 January 2023

Auckland Council: 17 March 2023. DELIVERY: In employment DURATION: 2 years

LOCATIONS: Auckland, Hamilton, Christchurch, Dunedin* FEES: $7,216 per year

NZ Certificate in Building Regulatory Environment (Level 4) STARTS: 21 February 2023

This programme is aimed at staff at Building Consent Authorities involved in processing and vetting of building consents AND now staff at construction companies, design firms, architecture firms and similar who are involved in the building consent submission process. Join from anywhere in Aotearoa and help build efficiency in the building consent process by reducing RFIs and building timelines.

How Best to Teach and Mentor Building Consent Plan Processing

I have been a competent Plan Processing Officer at all competency levels in both Residential and Commercial for many years at several Councils.

Then when I started to teach plan processing a student asked me a question that made me stop and think (Q so how do you know that?) I stopped and thought that I was trying to teach new BCO students the experience that I had, and they did not.

How do you teach or at the very least simulate experience? I thought about it and remembered a quote I was once told:

“That you hire a young person before they forget they know it all.” Then I thought about how I taught my son to drive a car. He did some driver simulator training and he thought this was easy and he knew how to drive, then the first time he got behind the wheel of a real car he drove over a roundabout.

I carry out plan processing a particular way, although how do other experienced processors go about it?

I surveyed fourteen experienced plan processors that I knew, and they all said basically the same thing.

They look at, review, and make notes, and/or mark up the issues on the plans. They either red pen the plans, use electronic post-it notes, or write up notes manually on paper, or onto a word document. These then become the base of the most RFI’s.

That said in reality they had then processed the building consent; their main problem was how best to record their reasons for decisions Regulation 6 b, c, & d.

Regulation 6 is the most awkward thing to correctly record, and my question was how best to teach that.

So now I try to teach and show students what the main risk areas of a building maybe, normally these are ground bearing, hazards, foundations, structure, durability, and weathertightness, (the entire building envelope). I try teaching them to concentrate on the main risk areas and write/record noticeably apparent reasons for decision, clearly reference to where they found the information and show the evidence, they accessed in making their decision.

No one really sues a Council because they do not have enough lights or windows in a building, although people do not like and councils get sued if the foundations or the structure fails, or the most common one is that people do not like it, if their house or building leaks, they also don’t like flood water, landslides coming through their building either.

Experienced processors do not sweat the small stuff, they concentrate on the key issues and record these decisions well.

In the end you cannot really teach experience the processor gets that by practice, practice, practice and by going onto building sites to view things and understand building construction in reality, in 3-D.

Finally: It is especially important that Council BCAs provide an experienced mentor and different consent types for processing training. Just like my car example you need to drive it to learn it.

You cannot teach experience although as a good employer and teacher you can help to facilitate and speed up the knowledge transfer.

Written by Patrick SchofieldHOD/Lecturer, Building Surveying Department Future Skills Academy.

Update on NZS 3404 Revision

- Fire Section Takes Form

The revision of NZS 3404: 1997 progresses with updated content proposed under Section 11 - Fire section

Background

Building System Performance commissioned a robust review of NZS 3404: 1997 (Parts 1 and 2) in December 2021. This standard is considered a primary reference that is a critical part of the Building Code compliance routes as well as a key citation within the Verification Method, B1/VM1.

NZS3404 supports the design and construction of steel buildings in in New Zealand. It sets out the minimum requirements for the selection of materials, corrosion protection

regarding the drafting of the fire section (Section 11). This incredibly important piece of work is being undertaken by a group of Fire specialists who are members of the Fire Working Group.

The proposed changes to this section have been made to ensure that it reflects current accepted practice. In addition,

a. New equations are provided (but this does not reflect a significant increase in workload)

b. Scope has been clarified stating that the fire provisions apply to non-composite steel members and systems, with no separating elements of construction. The design of individual members assumes they are isolated.

c. The Basis of design covers the principles for standard fires and natural fires. Performance criteria are discussed with an explanation of design criteria for individual members and systems.

d. The content regarding material properties aligns with the content in AS/NZS 2327

e. A temperature incremental approach is used for unprotected and protected members

systems, and the fabrication, erection and construction of steel structures.

It applies to building structures; crane support girders; highway, railway and pedestrian bridges; and composite steel and concrete beams and columns.

Section 11 - fire section takes form

This is an update of the progress

f. Simple analyses in the domains of time, temperature and strength, including equations to estimate the time to failure for unprotected and protected steel.

Further updates will follow as the project progresses through 2023 – to keep up to date follow Standards New Zealand on LinkedIn or subscribe to ‘Keep me up to date’ for NZS 3404 or the building and construction sector news.

Ryanfire Façade / Curtain Wall System

Background

In November 2020, MBIE issued a revision to guidance for the “Fire Performance of External Wall Cladding Systems”.

The guidance referenced two standards as pathways to compliance for “in wall cavities” within curtain walling, EN1364.4 or ASTM E2307.

This case study explores the standard, the critical elements require to pass the fire test

standards and Engineered Judgements (EJ’s) / Alternate Solutions.

https://www.building.govt.nz/ building-code-compliance/cprotection-from-fire/c-clausesc1-c6/fire-performance-ofexternal-wall-cladding-systems/ fire-test-methods-for-external-wallcladding-systems/

EN 1364.4 / ASTM E2307 Fire Test

The two referenced standards focus

on the fire performance of fire seals fitted in the cavity between the floor slab edge and curtain walling.

The test standard assemblies are different, ASTM E2307 requires a “window” opening to be built below the transom / floor level to allow fire to simulate breaking through the glazing and out of the building exposing the frame to heat inside and out, whereas EN 1364.4 has no window opening but is a closed system under potentially greater heat exposure.

Both are robust internationally recognised test standards of aluminium curtain walling, its arguable that EN1364.4 is more onerous as heat can’t vent through an opening (think of an oven door open during cooking), however ASTM E2307 reflects the blownout windows which is commonly questioned.

Aluminium Melting Temperature

One of the many challenges of fire protecting aluminium curtain walling is the low melting temperature of Aluminium (660C).

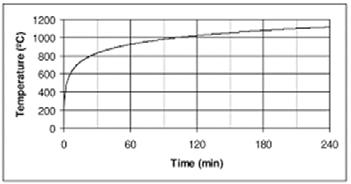

Both standards follow a “time temperature curve” which details the heat build-up in the test furnace over a given time.

fire test with products such as fire rated plasterboard, rockwool insulation or similar fire protection products.

The furnace will reach 660C in approx. 10 minutes during the fire test.

Test Specimen Construction

Due to the risk of the aluminium curtain walling melting and collapsing during a fire test, it’s important exposed aluminium framing be protected during the

Our research has yet to find any evidence of a system achieving a 60-minute fire rating to ASTM E2307 or EN 1364.4 without some form of aluminium frame protection.

PS – exposed aluminium frame protection is not provided by steel back pans alone, they are only one part of an overall solution!

EN1364.4 Fire Test 1 - PF21022

In June 2021, Ryanfire signed a contract to undertake a full

scale EN1364.4 fire test at Fire TS laboratory in Auckland.

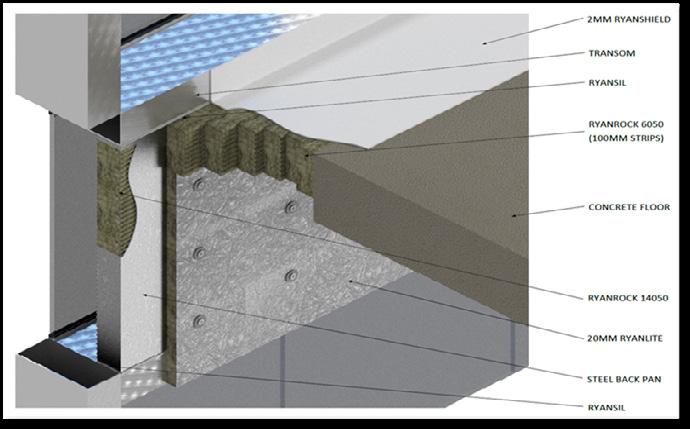

Galvanised steel back pans were installed between the horizontal transom and vertical mullions as a fixing substrate for the Ryanrock 14020 frame protection board as fixing directly into mullions or transoms is not permitted due to water ingress warranties.

The back pans were insulated, and fire protected using 140kg density foil faced Ryanrock rockwool slab to help prevent radiant heat damaging the curtain wall framing.

We installed Ryanrock rockwool board, 20mm thick foil faced spanning across the exposed aluminium mullions and transoms secured with screw fixings into the steel back pans.

The horizontal fire seal between floor slab and transom sealed with 60kg/m3 density 100mm thick Ryanrock rockwool insulation fitted under compression and over coated with Ryanshield fire rated water-resistant sealer coating.

Fire Test 1 PF21022 Results

On the 29 th June 2021 Fire TS Auckland fire tested our EN 1364.4 fire protection system.

Ryanfire was the first company to undertake an EN1364.4 test in New Zealand using an NZ aluminium curtain walling system.

The test was witnessed by three Auckland Council Fire Engineers.

The new system achieving 111 minutes fire protection (DWG V52.3).

EN1364.4 is part of EN1363.1

Product Launch

In July 2021, Ryanfire launched our newly tested system in New Zealand.

Almost immediately we received negative push back.

The feedback was that Ryanrock 20mm thick protection board spanning the aluminium framing wasn’t liked and that there were competitors issuing Engineered Judgments (EJ’s) / alternate solutions / systems that didn’t detail frame protection which councils were consenting “all the time councils keep consenting engineered judgments / alternate solutions / systems not requiring frame protection, we will keep proposing them”.

Ryanrock Rockwool 14020 board used to protect the framing costs approximately $25/m2 and can be easily factory installed and delivered to site as a complete curtain walling system ready for installation.

Note – an EJ or Engineered Judgment / alternate solution is an “opinion” usually issued in NZ by manufacturers. It’s not a fully tested system.

Further Investigation

We couldn’t understand how competitors could claim 60-minute fire rating to either standard without aluminium frame protection and thinking ASTM E2307 might be an easier test to pass. We contacted a fire testing laboratory in North America to

discuss the differences between EN 1364.4 and ASTM E2307.

During conversations, it was confirmed that in their opinion EN 1364.4 is probably a more onerous test standard than ASTM E2307 although the test standard configurations are different.

What was reassuring was the recommendation that if we wanted to pass an ASTM E2307 fire test it was highly recommended that we fit cover plates, also known as frame covers secured to the aluminium framing, because if you don’t install protection covers the frame will probably melt and you will likely fail the test.

We then searched publicly accessible online directories of ASTM E2307 tested systems showing systems with frame protection in many forms, from “frame covers” to “mullion & transom covers” as part of tested solutions.

EN1364.4 Fire Test 2 - PF22009

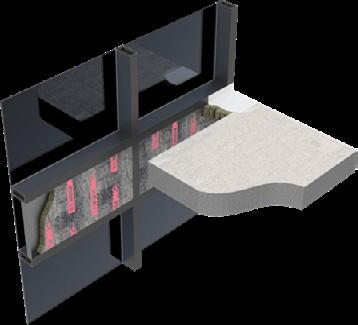

As final confirmation of our opinion that frame protection is essential to passing either test standards referenced in MBIE guidance, we commissioned a second full scale EN1364.4 test on 16th September 2022. It was a repeat of the first successful test but this time we removed the rockwool 14020 frame protection.

Example with frame protection removed

As anticipated, the fire test failed in 27 minutes even though EJ’s/ alternate solutions claimed a system with no frame protection or covers would provide 60 minutes fire protection.

Outcome

Our research to date has proven the requirement for aluminium

frame protection to curtain walling tested to either EN 1364.4 or ASTM E2307 to achieve a 60-minute fire rating and above.

We have reviewed many consented EJs / alternate solutions / systems across New Zealand and none appear to include frame protection. We also came across misunderstanding in industry by some consultants believing installing mild steel back pans would solely provide the protection to the frame.

Many of the EJs / alternate solutions / systems reviewed had disclaimers moving the risk to BCAs, cladding manufacturers, consultants, installers, and others. The disclaimer stresses the system proposal will only work if all curtain wall components are also fire tested to 60-minute fire rating, presumably to the same MBIE standards?

Discussion

Ryanfire has received negative pushback from industry to the research we have carried out surrounding ASTM E2307 and EN 1364.4. We are a passive fire protection material manufacturer. We are not fire engineers or fire designers. Government departments set the standards; BCA’s enforce the standards and we test and deliver systems that meet the standards.

Currently, we don’t believe it’s possible to pass an EN 1364.4 or ASTM E2307 test without protecting the aluminium curtain wall framing.

Curtain walling manufacturers think Ryanfire have an agenda; that we are trying to drive an

testing to either ASTM E2307 or EN 1364.4 and in our opinion it is critical, because of the aluminium’s vulnerability to heat, that you install a tested system or as close as possible to a tested system to ensure it performs as required in a fire scenario.

When dealing with products that don’t perform well in a fire test, the smallest item such as a frame cover really can mean the difference between pass or fail.

It is important to note that this case study is based upon our research to date. It is possible that there are systems that differ from our findings. Make sure the system you are proposing is fit for purpose and you are confident in what is sighed off as compliant. If there is any doubt, ask to see the original test report, preferably tested in New Zealand utilising a New Zealand curtain walling system.

over complicated over expensive system to market compared to a competitor removing part of their tested system making it more user friendly.

BCAs have perhaps unknowingly consented EJs / alternate solutions / systems with no frame protection but hopefully this research will highlight the fact that working with aluminium, with a low melting temperature is difficult when fire

Our research has highlighted the need for a much wider conversation surrounding aluminium curtain walling and the part it plays in fire design, but for now MBIE has provided guidance which we are following.

by Paul RyanRevision 1.9

...the smallest item such as a frame cover really can mean the difference between pass or fail.

Tested and trusted for 60 years.

We make SEISMIC® reinforcing steel to a high standard. Then we put it through a rigorous testing regime to prove it.

All SEISMIC® products are tested in our dedicated IANZ-certified laboratory to ensure they meet the stringent AS/NZS 4671 Standard.

Our products are designed for New Zealand’s unique conditions, by a team which has been manufacturing locally for 60 years.

That’s why we’ve been entrusted with some of the country’s most significant infrastructure and

building projects, and why people continue to turn to us for strength they can count on.

For assurance, confidence and credibility, choose SEISMIC® by Pacific Steel.

For more information, contact us at info@pacificsteel.co.nz or visit pacificsteel.co.nz

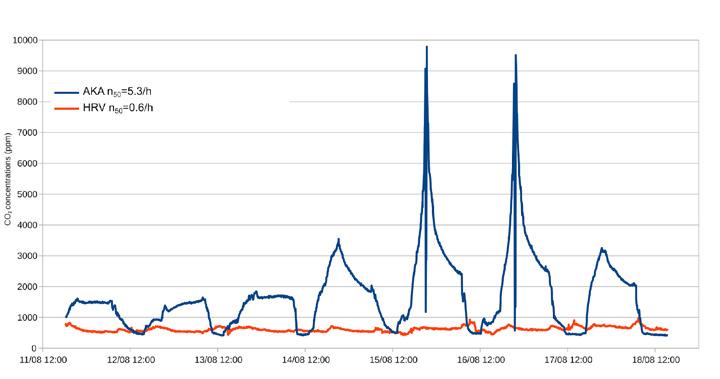

Time for a Rethink? Ventilation of Houses

Introduction

The effectiveness of building ventilation, particularly those managed isolation facilities (MIQ) used as part of the Covid-19 response, was questioned when it was suspected that contaminate air containing Covid-19 travelled from one room to another room, across the corridor. Correspondingly the ventilation systems of the MIQ facilities were altered to specifically prevent this occurrence happening again. While this is a very specific ventilation requirement, it made me think about ventilation of all buildings, but specifically houses.

For new buildings and houses

ventilation must comply with Building Code clause G4 Ventilation. This clause contains the following performances for:

• ventilation with outdoor air to provide enough air changes to maintain air purity

ventilation systems to be constructed and maintained to stop growing harmful bacteria, allergens and pathogens with in them

the removal of a list of situations and contaminants from the spaces in which they are generated

contaminated air to be

discharged to prevent hazard to people or other property ventilation to meet the additional demand for combustion appliances

The predominant way of complying with the Building Code for ventilation of houses is to use the Acceptable Solution G4/AS1 which uses 5% of the floor area as opening windows and doors. Five percent opening windows has been the ventilation requirement for New Zealand houses in the New Zealand Standard NZS 1900 Model Building Bylaws, the ‘Building Code’ before the current Building Code, and the Housing Improvement Regulations 1947.

Early European settlers to New Zealand constructed houses from timber. Wall frames, roof framing, foundations, subfloor, and floors were all timber. Strip timber was used for walls and ceilings, sometimes lined with scrim (hessian) and papered over. Wall cladding was timber weatherboards and roof cladding was mostly corrugated iron. Windows were rise and fall sash type with relatively small glass panes.

Opening windows were used for ventilation in houses, even though the type of construction allowed infiltration rates at a level far greater than found in today’s houses.

Changes in house construction

Over time, houses were increasingly constructed with sheet materials. Solid plaster exterior was used for the Art Deco 1930s style, and over the following decades the use of fibrous plaster for interior linings and ceilings and the frequency of concrete floors increased. Together with advancing glass technology, which allowed for larger pane sizes and changed window design, reduced the use of fanlights and small ventilating windows. Also, airtight aluminium frames reduced draughts and led to houses achieving low infiltration rates of 0.5 to 1 .0 air-changes per hour.

The requirement to insulate houses was introduced in 1978, which enabled possible saving in energy costs, or warmer indoor temperatures for the same energy cost. Additionally, emphasis was given to sealing construction draughts including those around timber window frames. Thus, further reduced the infiltration, placing greater demand on opening windows for ventilation. However, by drawing the occupant’s attention to the reduction of draughts from infiltration, this drew attention to the feel of airflow associated with ventilation, leading to a further reduction in ventilation of houses because it was not energy efficient to open windows, consequentially increasing the likelihood of damp and mould.

While ventilation of houses has stayed the same for generations, at 5% of the floor area in opening windows, the way we live in our houses has dramatically changed over the years.

In the 1900s, family dynamics were such that one parent went out to work, the other was at home using the house and ventilating the house. In 2000s there is a wider range of family dynamics with it being probable that all the occupants are not at home during the day and the house not being ventilated.

This is compounded by the increasing water-vapour producing activities, such as bathing, drying clothes inside and cooking in the morning before the house is shut up for the day and the same happens at the end of the day before shutting the house up for the evening. This situation is worse in winter, where the water vapour is more likely to condense on cold surfaces, leading to the growth of mould and mildew.

Ventilation options

One solution is to increase the use of technology to override human behaviour. Mechanical heat recovery ventilation systems where the in-coming air is heated by the out-going air, maintaining