This book was written by

the Youth Ambassadors for Queer History at One Institute in partnership with 826LA.

The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of 826LA. We support student publishing and are thrilled you picked up this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Este libro fue escrito por los Jóvenes Embajadores de la Historia Queer del One Institute en asociación con 826LA.

Las opiniones expresadas en este libro son las de los autores y no reflejan necesariamente las de 826LA. Apoyamos la publicación de jóvenes autores y estamos felices que hayan recogido este libro.

Todos los derechos reservados. Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de este libro sin autorización escrita del editor.

Editors:

Maddie Silva Trevor Ladner

Cover Artwork: Suzanne Yada

Book Design: Jodi Feigenbaum

The Home We Build Logo: Simon Ashford Echo Park 1714 Sunset Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90026 Mar Vista 12515 Venice Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90066

THE HOME WE BUILD: A QUEER VOICES ZINE

In celebration of our 20th Anniversary, 826LA dedicates this publication to all of those who have helped make our community what it is, what it was, and what it will become.

Thank you to the students, volunteers, educators, donors, staff, community partners, and time-travelers who have filled the last 20 years with such creativity, joy, and hope.

We look forward to another 20 years in partnership!

Introduction

I Am Glad I Am Homosexual. This simple, yet incredibly powerful phrase was written on a cover of ONEMagazinein August 1958.

As the nation’s first widely distributed queer publication, ONE Magazine printed all kinds of creative pieces, articles, and the like through an LGBTQ+ lens. It was seized twice by postal authorities in the 50s for containing what they considered “obscene” content. For years, the charges were fought and eventually the case was seen before the Supreme Court. This was the first case regarding homosexuality to be seen at the highest level. (“About One”).

History was made in 1958 when ONE Magazine won their case.

I Am Glad I Am Homosexual was a loud and clear message following their landmark win, making known the amazing power and resilience of queer people.

That message continues to ring proudly today through the pages of the zine you hold right now, The Home We Build.

Like the activists of the 1950s who started ONE Magazine, the authors of this publication have an important message to share: Queer and trans folks are not going anywhere.

The eight high school activists who participated in One Institute’s Youth Ambassadors for Queer History program spent a semester exploring, researching, and crafting the writing and projects you will find in this zine. They studied decades-old photographs,

posters, ID cards, and books at ONE Archives at the USC Libraries and engaged in rich discussion with historians, activists, and teachers.

The students then transformed what they learned into artistic projects and academic writing. From puppets representing the 1991 ACT UP protest at the Oscars to an in-depth timeline on the history of top surgery, their pieces uncover powerful and important moments in time that cannot be forgotten and which serve as our north star for forward momentum.

Though the language has evolved over time, the future that the activists demand in their pieces embodies the spirit of the joyful and unwavering phrase from 1958: I Am Glad I Am Homosexual. During a time where queer and trans rights continue to be under attack, the work you will see in this zine, that of which these student activists are profoundly dedicated to, is proof that queer resilience continues to reign.

–Maddie Silva

Oh My God… They’re Lesbians!

Eva Friedman, she/her

Los Angeles and lesbianism are the two characteristics that most define my perception of myself and my life, and my project explores the intersection of these identities and their manifestations in the experiences of others. My photography series aims to shed light on the lesbian experience by using portraiture to depict the lives of teenage lesbians in their homes around Los Angeles. Specifically, my project revolves around the question: How has the lesbian experience been depicted in photography, and how can I take inspiration from history for my own creative pursuits?

Through my research, I have explored work ranging from the 1970s to the 1990s by three different lesbian photographers known for their lesbian portraiture: Sunny Bak, Nancy Rosenblum, and JEB (a.k.a. Joan E. Biron). Exploring their works was incredibly eye-opening as it afforded me the ability to peek into the lives of lesbians from different time periods. As an artist, I am incredibly inspired by these photographers’ shared passion for lesbian visibility in their work, and I hope to infuse this same love and care into mine.

While researching in the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, I was surprised to come across Sunny Bak’s collection of photography printed on greeting cards as they were an example of explicitly lesbian photos having made it into the mainstream. A favorite find of mine was one card from 10% Productions, printed with the phrase “Ohmigod… they’re lesbians!” and sporting a 1995 photograph of a kiss over vintage cars (Bak). I also examined Nancy Rosenblum’s portraiture series Some of My Best Friends… Portraits of Lesbians, which is composed of photographs taken around Los Angeles from the years 1983 to 2008. One photograph of Pamela Hamanaka in her apartment in West LA, titled “#54” (1983), especially caught my eye for the way it intimately captured and tenderly humanized its subject. Hamanaka sits in an armchair

in the center of the frame, making eye contact with the camera and smiling softly. In Rosenblum’s exhibit description, she writes about her aim to create “positive images of lesbians that break through the myths and stereotypes,” as well as her hopes that the depiction of real lesbians in her work will contribute to overall growth in lesbian visibility and sense of community (Rosenblum).

As a group that had been subjugated to the shadows throughout history, the importance of increased levels of representation for and by lesbians themselves cannot be overstated. JEB’s 1979 photography book Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians is motivated by her desire to demonstrate “the strength, beauty and diversity of Lesbian women… our will to survive and our love of life are powerful. I have tried to convey some of that energy through these photographs” (Biron 6). The book provided not only portraiture inspiration but also a host of supplemental background information on the history of lesbian photography in the included 1979 essay “Lesbian Photography: A Long Tradition” by Judith Schwarz. Schwarz discusses the rise of lesbian-feminism politics in the early 1970s, which furthered the lesbian need for visibility. She also cites the 1970s as a period in which lesbian photography was able to establish itself and the work of lesbian photographers, such as JEB, grew in public recognition (Schwarz). Although my own project is occurring fifty years later, I can absolutely relate to this hunger for lesbian representation informing my photographs.

Despite the fact that my research centers around eras that occurred decades ago, many of the aims and goals of these photographers remain unresolved. For example, Rosenblum’s desire to increase visibility and break through pervasive stereotypes using positive images of lesbians is an important pursuit that continues to ring true today. Additionally, while JEB’s hunger for representation— “I couldn’t picture being a lesbian, life

as a lesbian, because there were no lesbians living out lives to see”— has come a long way since her book’s publishing entered lesbian visibility further into the mainstream, we still have a long way to go (Biron 85). Today, as lesbianism continues to either be dismissed and ignored, or tokenized and fetishized, lesbian photography remains relevant as a way to define our depictions and standings in society for ourselves.

Certain photographers today are working to transcend the boundaries of vying for simply an increase in representation, such as Maddie Keyes-Levine. Keyes-Levine, a Los Angeles photographer whose series Team Sport was exhibited at the One Gallery in West Hollywood this fall, explores the inner workings and members of the organization Dyke Soccer. Through her work, she aims “to show something specific, like how I feel about something in a way that feels more expansive than just positivity or representation.” When I asked her about her work’s importance, she said, “I like to think that the photos could serve as a future archive that queer, trans, nonbinary, lesbian, soccer freaks were doing something together for a long time and it was fun and cool and important for living in the way that friendship and play is actually super important because it’s kind of everything at the end of the day.”

I hope that my work is able to give audiences an intimate peek into the lives of my subjects in order to further understand not only one piece of the lesbian experience today but also how our lives fit into the human experience in general. As our society and world continue to evolve, I also hope to see continuous growth in our value of community, appreciation for others, and genuine desire to learn about one another’s unique experiences. While the photographers whose work informed my project fought hard for lesbian visibility, there are still gains to be made for the equal representation and depictions we deserve not only creatively, but also in general socially. I hope to see the unique lesbian experience continue to be respected and amplified, a pursuit that I hope will lead to growth in care and empathy both in our community and in wider society. Finally, working on this project

has allowed me to develop a further appreciation for portraiture as an art form for its unique and emotionally-charged ability to teach audiences about the lives of individual human beings. I would love to see future Youth Ambassadors study more portraiture of our queer elders.

Eva, 17, responds to a letter from "Helen," a lesbian from Kansas, who wrote to ONE in May 1957. Helen encourages ONE’s legal battle with the postal authorities: “There’s definitely a big place in the world for us if we aren’t afraid... Good luck.”

Helen shares that she has “woofed” back against a discriminatory District Attorney in Missouri as well as homophobes that have targeted her homosexual friends, and criticizes politicians that invade homosexuals’ privacy.

Painted Queens: A Century of Drag Makeup

Bailey Linares, she/her

Today, drag makeup is celebrated for its artistry and its ability to challenge and redefine gender norms. It continues to evolve, drawing inspiration from fashion, art, and technology. As society expands and restricts the acceptance of diverse expressions of identity, drag makeup remains a vibrant and dynamic form of selfexpression that celebrates individuality and creativity. The history of drag makeup is a testament to the resilience and creativity of those who have used it as a means of expression throughout the ages. From its theatrical origins to its current status as an LGBTQ+ cultural phenomenon, drag makeup has continually adapted and evolved, reflecting the changing tides of society and the enduring human desire to explore and celebrate identity.

In researching the history of drag makeup, I analyzed a variety of archival sources, including historical queer news publications, photographs of early drag performers, theater makeup guides, and LGBTQ+ zines. These materials provide a deeper understanding of how drag makeup has evolved—from its roots in theatrical performance to its current role as a powerful form of selfexpression within LGBTQ+ culture. For example, early 20th-century vaudeville and female impersonation performances reveal the ways makeup was used to exaggerate features for stage visibility, while zines and underground media from the 1980s and 1990s document how drag makeup became a form of political resistance during the AIDS crisis (Howe; Recker).

This topic is deeply personal to me because drag makeup represents more than just artistry— it is a tool for self-exploration, resistance, and empowerment. As an Afro-Latina and LGBTQ+ individual, I see drag makeup as a space where different aspects of my identity can intersect and thrive. The history of drag makeup reflects the resilience of marginalized communities, particularly Black and Latinx queer individuals, who have played a foundational role in shaping drag culture (Jamoo; Shane; Waxman).

Understanding this history allows me to appreciate the ways in which drag makeup has been used to challenge beauty standards, redefine gender norms, and celebrate cultural hybridity.

My project explores the evolution of drag makeup styles through a series of hand-painted masks to represent each era. Masks symbolize both concealment and revelation— core themes in the LGBTQ+ experience and the evolution of drag. Throughout history, masks have allowed marginalized communities to navigate restrictive societal norms while simultaneously expressing their true identities (Boswell; Daughters of Bilitis; Dotson). In the context of drag, makeup functions much like a mask, offering protection, transformation, and empowerment. By framing drag makeup through the lens of masks, I highlight its role as both a survival tool and an artistic medium that challenges traditional notions of gender and beauty.

The origins of drag can be traced back to ancient times when men performed female roles in theatrical productions. In ancient Greece and Rome, women were often prohibited from performing on stage, so men donned costumes and makeup to portray female characters. This early form of drag was more about practicality than artistry, with makeup used primarily to exaggerate features for visibility in large amphitheaters. During the Renaissance, theater became more sophisticated, and so did the use of makeup. In Elizabethan England, all female roles were played by men or boys, as women were not allowed to act. Makeup during this period was heavily influenced by the fashion of the time, with pale faces achieved through lead-based powders and rouge used to highlight cheeks (Howe; The Makeup Academy). The emphasis was on creating an idealized version of femininity, which was often dictated by societal standards.

The 18th century saw the rise of pantomime and burlesque, where exaggerated makeup became a tool for comedy and satire. The 19th century introduced vaudeville, where performers used makeup to create larger-than-life characters (Howe; The Makeup Academy). These performances often included elements of drag, though they were sometimes used for racist and sexist

portrayals as seen in minstrel shows (Howe;Comer). However, as early as formerly-enslaved drag queen William Dorsey Swann in the 1880s, Black queer people have organized underground drag balls to provide a space for LGBTQ+ individuals to express themselves freely, crystallizing in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s (Shane; Waxman). Here, makeup became a powerful tool for transformation and self-expression; the look was bold and glamorous, with heavy eyeliner, dark lipstick, and dramatic contouring (The Makeup Academy).

By the mid-20th century, drag had begun to enter mainstream culture and solidified its status as an LGBTQ+ cultural art form. The 1960s and 70s saw the rise of iconic drag queens like Divine and the influence of pop culture figures such as David Bowie and Boy George, who blurred gender lines with their androgynous looks. The late 20th century brought drag into the spotlight with the emergence of RuPaul, whose hit song “Supermodel (You Better Work)” and subsequent television show RuPaul’s Drag Race popularized drag culture globally (Jamoo; The Makeup Academy). RuPaul’s influence on drag makeup cannot be overstated; his signature style—flawless skin, bold eyes, and extravagant wigs— set new standards for drag aesthetics.

In the 21st century, drag makeup has become more diverse and innovative than ever before. Social media platforms like Instagram and YouTube have democratized access to makeup tutorials, allowing aspiring drag artists to learn from established queens and experiment with their own styles. The influence of digital culture has led to increasingly intricate and creative makeup looks, incorporating everything from avant-garde designs to hyperrealistic illusions (The Makeup Academy).

Learning about queer and trans history as it is is crucial for young people, especially in today’s political climate where LGBTQ+ rights are increasingly under threat. Understanding our history not only affirms our existence but also provides us with the tools to resist oppression. Too often, queer and trans stories have been erased, sanitized, or rewritten to fit dominant narratives. When we engage

with our past, we see that our struggles— and our victories— are part of a long continuum of resistance, resilience, and joy. My greatest fear for the future is that the erasure and repression of our history will deepen, making it harder for young people to find themselves and understand their place in the world. But, my hope lies in the fact that we continue to tell our stories, pass down our knowledge, and build spaces where we can thrive.

Oreo Girl

Bailey Linares, she/her

I would always get comments on how “I speak so well for my people” or “I’m so smarter than the others,” but I always wondered what people meant by that. My mother, raised in Compton as a child, and at the time already struggling to fit in racially for being African American, is as I would consider it very stern on how to represent myself well and represent my community.

“I’m too white for the black kids and too black for the other kids. What should I do?” as I look at my mom with my teary 7 year old eyes, after understanding the term of being called an Oreo at school that day.

I vividly remember the added judgement accompanying the numerous “you’re whitewashed” comments I would get constantly, even at an age that can’t fully grasp the idea of the border between curious and down-right racist. The features of me I couldn’t actually control – my hair being “nappy”, my skin being “too dark” usually from anyone who wasn’t black, or “not being ghetto enough” plus “being an Uncle Tom” from my very own people.

I wouldn’t say that I was raised in an affluent African American community. The way many people see or say how black people have a certain way of talking or presenting myself would make me wonder: what does a black person even “look” or “sound” like? Am I so wrong for wanting to enunciate my words or have a certain liking for nerdier hobbies? This feeling of being stuck in between multiple places, never feeling like I truly fit in with any group. So what did I do — try to immerse myself in the black agenda.

BSU, Spoken Word, BLM rallies, and other uplifting black communal events I remember attending. If they exist, I probably joined them. It was a beautiful experience to see my own people

in a group together to support a cause, but something wasn’t right.

“I came here looking to reconnect with my roots. But now I feel stupid for even thinking that was possible. I put on the honor of clothing I was given, and it feels like a costume. This is not my home. I’m a tourist here.”

This line of dialogue ran through my head as I stood in the mirror wearing my brand new Kente cloth dress, gifted to me by the Spoken Word host the night before. I cried — I felt like a white sheep. I was trying so hard to fit into my black culture, that I lost my true sense of identity.

Being ostracized from not only from any race group, but most importantly not even being able to accept myself ate at me. Even though if you look at me and can see pretty quickly that I was indeed black, the main issue despite my own problems was the message society preached through cartoons, commercials, toys and books, and through my interactions with peers in grade school. It was that physical and emotional appearance determined self worth. No one ever had to say this to me directly. This unspoken rule was common knowledge, even from a young age. It determined who was popular, who wanted to sit by whom and who was chosen first. It determined who was written up for not sitting quietly and whose naughty behavior was overlooked, who received extra help and who didn’t and who was worth the investment and who wasn’t. If you were dark skinned, fat, disabled, or black, which ironically I all am – your place in the hierarchy was a lot lower down. That much was clear.

But then I realized everyone has culture. While we are born into cultures, we are not born with culture. Culture is something that we learn. Culture is dynamic and adapts to changing circumstances.

I am black, black is me. But my culture is Bailey.

Sometimes, slapping a label on yourself is comforting, because otherwise, you’re just drifting through these communities, waiting for someone to accept you as you are without a need to provide a rehearsed explanation of caveats. But they’re both two worlds that I’m slightly removed from — and that’s okay. It’s okay to be confused and scared.

I am proud to be African American and still support the many struggles we have today. I also still struggle sometimes with trying to fit in, but am happy with myself that I try to not be boxed into one side or another. Culture is and will always be a never-ending topic that never has a solid answer, but some things are never to be found out. I am happy with Bailey, me.

Receiving Decades of Drag

Aymee Mendez, any pronouns

I would always get comments on how “I speak so well for my Today, drag has become a popular form of entertainment with the reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race, but it has not always been in the limelight. My project focuses on the contrast in society’s reception of these performances from the 1970s to the present. Drag culture is one of my favorite parts of the LGBTQ+ community; I’ve been enamored by the confidence and pizzazz the drag performers I watched have exhibited. They’ve given me the confidence to be as self-expressive as I want and not care about others’ opinions. Consequently, I desire to learn more about their history to see if they have always been so iconic and influential.

In the late twentieth century, drag performances by openly gay or transgender people were often only considered artistic performances by the queer community, and the outside world considered them as vulgar entertainment by psychopathic “transvestites” (Meyerowitz, 104; Newton, 3, 51). Cross-dressing, being transgender, and drag were understood as different yet interconnected by members of these communities, though conflated and ostracized by outsiders (Meyerowitz 193). Drag is more widely understood today as a form of self-expression typically seen through glamourous performances while being transgender is an identity where one transitions from their assigned gender to one they find more comfortable (GLAAD). This difference is perfectly described by a transgender performer in RuPaul’s Drag Race, Monica Beverly Hills, who states, “Drag is what I do. Trans is who I am” (RuPaul Charles).

Lee Brewster, founder of the Queens Liberation Front, published Drag magazine in the 1970s, preserved today in the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Drag was a form of news for the queer community, tailored for drag enthusiasts and trans women. According to historian Joanne Meyerowitz, “Few drag queen

activists identified as transsexual,” what we today call transgender, “but Drag published a number of columns on and by transsexuals who saw themselves as part of the movement” (236). One cartoon from 1972 can represent drag or gender dysphoria. The image shows a man and woman in the wilderness. On the floor lies their clothes; they seem to be wearing undergarments with the woman only wearing a bra and the man wearing her underwear. The woman has a distressed expression on her face as she covers her lower region; meanwhile, the man has a smile on his face as he poses with a knee slightly bent and an arm reaching towards the woman with his wrist flicked downwards. With his head slightly tilted, he says “This is thrilling Miriam— I’ve been wanting to get into your panties for months” (Brewster). This play on words goes from the popular interpretation of the man wanting to sleep with her to wanting to wear her clothes, or to experience being a woman. While appealing to men who like to dress up in feminine clothing, Drag also provided community to transgender women, who were often only able to be transgender through drag.

A video from the ONE Archives, filmed by Pat Rocco in 1970, shows how drag performances expressed themselves without caring for gender norms. Rocco captures a drag competition where multiple drag performers each come one-by-one or with a partner, fully dressed up in their glamorous drag costumes, and do a quick performance. Everyone was having the time of their lives with the audience cheering for each performance. There were a variety of performances: someone dressed up as Raggedy Ann, Colonel Sanders, and even a seemingly-straight couple! The performances weren’t only drag queens— there was even a clown. The audience didn’t care who was wearing the costume; they just enjoyed watching the drag performers’ engaging entrances (Rocco 1970).

Some people have understood drag’s beauty while others have considered it a disgraceful art form. An example of this is the life of Gangway Suzie, a famous drag performer in the 1970s. Suzie, also known as Alfred Slezewski, was a well-loved member of the Los Angeles and San Francisco gay communities, creating various

charity events as a member of the Imperial Court System. In the queer community, she was an icon; however, to heteronormative society, she was a disgrace. In the Gangway Suzie collection at ONE Archives, a newspaper clipping titled “Murder a Gay Man and Get Off” by Allen White states: “Douglas Toney admitted killing ‘Gangway Suzie.’ He has been found not guilty by a jury.” White continues, “The person who admitted to killing ‘Gangway Su[z] ie’ has been acquitted,” even though the Deputy District Attorney and prosecutor of this case, Tom Norman said, “‘The evidence is overwhelming.’” (White 1982). This popular drag performer in the community was murdered in “self-defense” by a person who later had his murder charges dropped simply because Suzie was a member of the queer community. Drag performers may have been loved by the community for their glamour and self-confidence but despised by the rest of society for challenging gender norms.

Drag has become a massive hit in pop culture with the reality TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race. Nowadays, most queer events will include a drag performance, of which I have experienced quite a few. In 2022, Kiena Sheldon from Psychiatric Times stated that with drag entering mainstream media, “many use it to explore sexual orientation and gender identity.” Drag is being wellreceived enough that people see it as a way to further explore themselves. Not to mention, Drag Race “also gives heterosexual audiences a glimpse into the lives of individuals from the LGBTQ+ community, including those who identify as transgender or nonbinary. Seeing [the queens] stressed about the competition, making friends, and supporting one another— all while crafting mind-blowing creations— shows that they are human beings like everyone else” (Sheldon). Drag Race has not only spread the influence of drag but also helps reduce homophobia and transphobia by showing society that queer people are also human.

Of course, some are against drag being normalized due to its “sexual” nature. In the Guardian, Katherine Rogers writes, “Drag is a fabulous, funny, and fascinating art form that has been around for more than 100 years. But it is also highly sexualized adult content.” Rogers believes that drag itself is okay; however, she has

issues with drag performers doing performances at schools or for children because it’s something to which they should not yet have exposure. Her viewpoint is understanding that no child should have exposure to sexual content until the right time. However, it is unjust and degrading to label drag as a performance that can only be sexual. Rogers shows how society, even as it gets more progressive and accepting, will still not fully accept drag performers, and the queer community; it seems to always find a way to bring it back down.

When I went into high school, my ninth-grade teacher, Mr. Lopez, taught me that I should cherish and learn more about my identity. I took this advice to heart and began to realize that while the people around me started to date or develop feelings for one another, I had felt no such spark and found the idea foreign. That’s when I realized that I was ace, or asexual. My discovery gave me some peace of mind, but I did not find myself to be any different than I was before. I was still an insecure teenager. This teenager never experienced anything related to the queer community other than being with queer friends— that is until Pride Day came around in June. This event at my high school features LGBTQ+ nonprofit organizations, food, vendors, and drag queens. That Pride Day was my very first drag show; there were two drag queens— one of which was Mr. Ladner, who is now the supervisor of Youth Ambassadors for Queer History. I was enamored by their performances; they had so much confidence and talent. No one could take their eyes away from them. The queens inspired me to be more self-confident and further explore ways to express myself so that one day I could radiate just as much as they did. I am just like the people in the past who felt pride and inspiration from drag performers.

In this research, I have aimed to show how influential and captivating drag performers are but also demonstrate the struggles of drag’s acceptance by greater society. I want people to be able to look at my work and feel prideful of the process and beauty of drag. They should feel the desire to go watch a drag show after seeing my work. I want a future in which everyone has

a love for drag. After all, as RuPaul says, “We’re all born naked, the rest is drag.” My hope is that doing drag or being queer in the future is considered normal. By then, I hope someone will continue my research and compare my present to their present.

Go watch a drag show!

Aymee, 17, responds to a letter from "Lori," a 25-year-old from Baltimore who wrote to ONE in November 1964. Lori struggles to come to terms with their gender identity: "Outwardly I’m a woman, but inside I have a male’s emotions... At times, I become 2 different people." Lori is attracted to women but does not identify as a lesbian. This anguish over identity and love has led to three suicide attempts; they ask ONE to connect them with an understanding friend or lover.

Receiving Decades of Drag Scavenger Hunt

1) What was the name of the bar where Gangway Susie got the name “Susie?”

Lemon Twist Bar - G

Gangway Bar - S

Orange Twist Bar - D

LA Bar - R

Gangway Suzie/Susie (Alfred K. Slezewski)

In 1928, in New York City, Alfred K. SLezewski was born on June 25th. He was later known as Gangway Suzie, a famous drag performer in San Francisco. His journey to becoming this icon started in Los Angeles where he adopted the name Suzie/Susie at the Lemon Twist Bar and started to perform “camp” at drag queen competitions and bars. Later he moved to San Francisco where he gained the name Gangway after bartending and doing drag performances at the Gangway Bar. Gangway Suzie earned a multitude of awards/certificates; one being from the Grand Ducal Court of San Francisco naming her the Prime Minister. She was a local celebrity in the queer community; however, the same could not be said about the rest of society. In 1982, Gangway Suzie was brutally stabbed to death by Douglas Toney. He was 27, and Suzie was 52. Toney admitted to the murder but was still acquitted of the crime even though there was enough evidence to charge him (White 1982; “Certificate appointing Gangway Suzie to ‘Prime Ministress’”; “Finding Aid to the Gangway Suzie Collection).

2) Who was the performer before Dominic the Singing Nun?

Raggedy Ann - L

Colonel Sanders & the Best Fries in Town - A

A man & a Woman - E

A Clown - T

Joani Presents Drag Show Video: tinyurl.com/dragshowvideo

3) What was the country who made gay marriage legal and had the drag queen Nymphia Wind perform for the president?

Taiwan - A

Thailand - C

China - O

Korea - U

Search Nymphia Wind on Google!

4) Look for the final letter to complete the word! ___ ___ ___ ___!

Medical Necessity

Jasper Chen, he/him

The term “top surgery” refers to a double mastectomy, usually undergone by transgender people who were assigned female at birth. Like all gender-affirming procedures, it is misunderstood. The very idea of top surgery is used by anti-trans crusaders to spur disgust against transgender people; “cutting healthy breasts off teenaged girls with mental health issues” is how JK Rowling described the procedure on Twitter/X (Rowling). I’m sick of this type of rhetoric—so I chose to focus on the history of top surgery to address these misunderstandings. Top surgery is not a new and terrifying procedure forced upon any mentally-ill girl who appears in a doctor’s office, but a well-researched and often life-saving procedure. In my project, I laid out a timeline of top surgery based on research at the ONE Archives and elsewhere. This timeline explores mastectomies as a medical procedure, the accounts of individual trans men, gender-affirming care in general, and outside perspectives of the procedure to examine what top surgery looked like in the past and what it looks like now.

At the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, I examined the Reed L. Erickson papers, consisting of correspondence and informational materials relating to the Erickson Educational Foundation (EEF). Reed Erickson, a transgender man, started EEF in 1964 to research “areas where human potential was limited by…mental or social conditions…where the scope of research was…new, controversial, or imaginative.” The EEF mostly focused on transsexualism, working closely with ONE Inc.—and even sometimes provided financial support for dolphin communication research (Coll2010001; “Reed Erickson and the Erickson Educational Foundation”).

Transmasculine people have always wanted top surgery as part of medical transition. Medical pamphlets published by EEF reference top surgery as a desired procedure for many men (“Reed Erickson and the Erickson Educational Foundation”). The desire goes further back. Michael Dillon was born in 1915, and wrote of his

childhood: “People thought I was a woman. But I wasn’t. I was just me. How could one live like that?” (Dillon 73). In the 1940s, Dillon received a double mastectomy (Ward and Jones). In 1966, Harry Benjamin’s groundbreaking book, The Transsexual Phenomenon laid the groundwork for modern trans medicine. Gender clinics slowly came into existence at universities across the country (Gaffney). Some eighty years after Dillon’s transition, trans people still undergo top surgery.

By September 2024, an estimated 110,00 American trans teens lived under a gender-affirming care ban (Simmons-Duffin). On January 28, 2025, the President of the United States released an executive order attempting to ban gender-affirming care for all Americans under the age of 19 (The White House). The order will likely be challenged—but promises of Department of Justice prosecutions and withholding of federal funds to institutions that provide gender-affirming care will lead to this care being less accessible. The order itself will lead to a resurgence in anti-trans sentiment. Trans people, particularly trans children, will die utterly preventable deaths because of this.

But, I have hope for the future. I truly believe that the anti-trans activists who have led us to this moment are on the wrong side of history. Someday, they will be remembered as just another failed group of bigots. In the meantime, there will still be trans kids. There will always be trans kids.

Timeline

Mastectomies have been performed since at least the 1500s, usually as treatment for breast cancer. In 1804, Japanese surgeon Seishu Hanaoka performed a mastectomy. This is believed to be the first surgical procedure ever conducted under general anesthesia (Freeman et al.)

In 1919, Magnus Hirschfeld, a gay Jewish German doctor, opened the Institute for Sexual Science. The facility offered medical care and community for those dealing with a wide variety of issues related to sexuality, but Hirschfeld was especially interested in same-sex attraction and gender identity (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

He coined the term “transvestit” (transvestite) to broadly describe those who wore clothing not matching their sex assigned at birth. At the Institute for Sexual Science, some of the first genderaffirming surgeries in the world were performed (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

In 1933, Nazis burned thousands of items stolen from the Institute. These books, papers, and clinical files contained irreplaceable information on homosexuality, gender identity, and medical transition. Soon, the Institute was forced to close. Hirschfeld left Germany before this event, and he never returned (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

In 1915, Michael Dillon was born in England. In the 1940s, he met a sympathetic plastic surgeon who, hearing of his gender

identity, offered to perform a double mastectomy (“Michael Dillon: A Biographical Exhibition”). This is one of the earliest examples of gender-affirming top surgery that I could find.

In 1946, Dillon published Self: a study in ethics and endocrinology. Without referring much to his own experiences, Dillon advocated for gender-affirming healthcare. “Surely, where the mind cannot be made to fit the body,” he writes, “the body should be made to fit, approximately, at any rate to the mind…” (Dillon 53).

In 1963, Reed Erickson began his gender transition as a patient of Dr. Harry Benjamin (“Reed Erickson and the Erickson Educational Foundation”). Benjamin was a friend of Magnus Hirschfeld, and one of the few doctors at the time who would aid transgender patients in medical transition (Li).

In 1964, Erickson founded the Erickson Educational Foundation (EEF), which mainly researched transsexualism (“Reed Erickson and the Erickson Educational Foundation”). EEF worked closely with ONE Inc. and published resources for trans people seeking legal help, medical treatment, religious counsel, and so on.

EEF’s pamphlets suggest that mastectomies were common procedures for FTM patients. “The female-to-male transexual will enter the hospital for hysterectomy and, in most cases, mastectomy…[there is] little or no scarring…the appearance of a normal male chest is achieved,” reads one (Erickson Educational Foundation 28).

In 1965, Johns Hopkins University opened one of the first gender clinics in the US (Gaffney). EEF pamphlets list a number of gender clinics that are hosted at universities: UCLA, University of Minnesota, University of Washington - Seattle, and Stanford University are among them.

In 1966, Harry Benjamin published The Transsexual Phenomenon. While later critiqued by trans people, the book undeniably helped create the modern field of trans medicine. As with EEF’s pamphlet, The Transsexual Phenomenon suggests that the two surgeries most desired by transgender men are hysterectomies and mastectomies (Benjamin 89).

In 1979, the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association was established. This later became the World

Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), a stillactive nonprofit that publishes Standards of Care for transgender people based on scientific research (USPATH And WPATH Respond To Ny Times Article “They Paused Puberty, But Is There A Cost?”)

In 1980, Lou Sullivan underwent top surgery (Surgery: From Top to Bottom). Sullivan was a community organizer and activist who was instrumental in helping other trans men get the care they needed (Highleyman). In 1986, Sullivan established FTM International, which published a monthly newsletter providing resources for members (Highleyman).

Transgender men were becoming more visible. In 1994, they marched in the San Francisco Gay Pride Parade as their own group for the first time (Surgery: From Top to Bottom). In 1996, Loren Cameron, a transgender man, published a book of intimate portraits of trans people: Body Alchemy: Transsexual Portraits. Again, Cameron’s book makes clear how crucial top surgery is to many trans men. “Many transsexual men feel discomfort with having breasts and usually obtain reconstructive chest surgery as

soon as possible” (Cameron 56). Cameron’s portraits show two subjects who obtained top surgery through different techniques, given their varying breast sizes.

In 2022, WPATH published updated standards of care. They are quite clear on the topic of top surgery. “The efficacy of top surgery has been demonstrated in multiple domains” including increased quality of life, decreased gender dysphoria, and increased satisfaction with one’s body. “Additionally, rates of regret remain very low, varying from 0 to 4%” (Coleman et al 128).

Timeline Essay

In America, the availability of top surgery (and all gender-affirming care) is under attack. The Trump administration has never been kind to trans people, but they flail into a second term with a particularly focused cruelty. The President seems determined to use the full power of the federal government to make trans children as miserable as humanly possible, until they leave either the country or the world.

There’s a very specific narrative surrounding gender-affirming

care. Conservatives and insane people say it like this: Innocent young girls are being given puberty blockers, hormones, and surgery by incompetent doctors who bow to powerful leftist interests. These girls are not really trans, but are perhaps suffering from a social contagion of some sort. And several years from now, these girls will bolt awake from their yearslong daze, throw away their testosterone gel, and scream with horror for what they have done to their bodies.

Liberals and slightly saner people say it like this: Yes, of course, I support human rights, but these kids are far too young to understand what they are doing to their bodies and we should be researching these treatments properly and of course that cannot be done in today’s partisan environment.

Mainstream news outlets have helped this rhetoric become popular. In particular, the New York Times has repeatedly published front-page stories which lend credence to the false idea that the science on trans healthcare is not settled. In 2022, WPATH published a multi-page rebuttal to a Times story about the potential danger of puberty blockers. By 2023, over 100 LGBTQ+ organizations and figures had signed an open letter to the Times demanding that they end their biased coverage. The Times ignored their advice. Over here in the real world, every major medical association supports gender-affirming care and detransition rates vary by study but are generally low (GLAAD, “Medical Association Statements”). A 2021 study of 8,000 trans patients who underwent gender-affirming surgery found only around 1% of patients regretted the decision (Bustos et al.)

(In the wake of the 2024 election, while LGBTQ+ youth called suicide hotlines, the Times published a story that began, “To get on the wrong side of transgender activists is often to endure their unsparing criticism” (Peters). The article proceeds to misrepresent the views of JK Rowling to a point that it would take about three more pages to explain everything they got wrong.)

This is the exhausting type of bigotry which attempts to disguise itself as genuine concern. Andrea Long Chu writes, “I suspect… the anti-trans liberal sees himself as a concerned citizen, not an ideologue.”

But of course, that’s just what they are. They’re uncomfortable with

gender nonconformity, so they’re willing to destroy our lives. They want to promote anti-trans ideology and use pseudoscience to chip away at every essential right trans people have, but they want to be seen as respectable citizen journalists in the meantime.

Republicans also pretend their issue with trans people stems from reasonable anxiety, but they’re more likely to let the mask slip. Trump’s executive order banning trans people from the military barely bothered with misrepresenting scientific studies, skipping straight to outright hatred: “adoption of a gender identity inconsistent with an individual’s sex conflicts with a soldier’s commitment to an honorable, truthful, and disciplined lifestyle, even in one’s personal life” (The White House).

None of these concerns are based in science, and giving in to anti-trans demands on gender-affirming care will do nothing but ensure their next push will erode trans rights further.

Jasper, 17, responds to a letter from "Lori," a 25-year-old from Baltimore who wrote to ONE in November 1964. Lori struggles to come to terms with their gender identity: "Outwardly I’m a woman, but inside I have a male’s emotions At times, I become 2 different people." Lori is attracted to women but does not identify as a lesbian. This anguish over identity and love has led to three suicide attempts; they ask ONE to connect them with an understanding friend or lover.

Lights, Camera, Action: ACT UP in the Fight for AIDs Action

andQueer Representation

Piper Lohse, she/her

OSCARS EQUALS MONEY

MONEY EQUALS POWER

EQUALS

This was one of many chants yelled outside the entrance to the 1991 Oscars by ACT UP to urge Hollywood to take action during the AIDS crisis (“Oscars chant”).

This project centers on the ACT UP protest at the 1991 Academy Awards, or Oscars, examining how it challenged Hollywood’s actions during the AIDS crisis and contributed to the broader effort to evolve LGBTQ representation in film. It is important to understand how Hollywood’s power and influence impact real issues affecting real people and that films, and the individuals who create them, hold immense social and political sway. As a queer person, I feel and see the impact of Hollywood’s portrayal of LGBTQ people and its role in representation.

My focus is on the impact of Hollywood during the AIDS epidemic, beginning with an ACT UP demonstration at the 1991 Oscars. This protest condemned Hollywood for ignoring the AIDS crisis and implored the industry to invest in treatment and research, use its influence to raise awareness, and “eliminate homophobic images in movies that bash gays and lesbians and don’t take gays with AIDS seriously” (ACT UP Los Angeles). For the exhibition, I created a puppet of David Lacaillade, one of the ACT UP members who snuck into the Oscars and made a scene to bring attention to Hollywood’s inaction concerning AIDS (Gallagher). This medium, a puppet, explores a nontraditional form of portraiture, aiming to

represent and introduce this story through symbolic objects, like the puppet and replicas of the buttons handed out during the protest. Each element of the puppet is designed to represent the activism and resilience of the era. Lacaillade’s story as a framing device immerses viewers in the protest: ACT UP members holding Oscars posters in front of the building, writing letters to celebrities, and distributing buttons with the slogan “SILENCE = DEATH”.

At the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, I explored many articles and leaflets from the protest, including ACT UP’s proposal for national action and media demands, posters for the event, and letters sent to celebrities with buttons, urging them to take action and represent by wearing them on air. One of the posters stood out, depicting an Oscar statuette wearing a condom. It juxtaposed the polished, proper image of the Oscars with the provocative image of the condom, creating an intentionally shocking and memorable visual (ACT UP Los Angeles and Critical Mass). The boldness of this imagery leveraged the power of controversy to grab attention and leave a lasting impression.

One of the highlights of my research was speaking with Judy Sisneros, another key activist who participated in the same protest. She provided additional insight into the creation of the statuette, which added deeper meaning to its symbolism. For instance, organizers were granted permission to use Dorothy Malone’s Oscar for Best Actress (which she won for Written on the Wind in 1956), a film that co-starred Rock Hudson (Sirk). Rock Hudson’s death from AIDS-related complications in 1985 is considered a flashpoint in the AIDS epidemic. His death helped generate awareness in Hollywood and spark public support (Shaw). The connection between Hudson and Malone’s Oscar was intentional and poignant, underscoring the protest’s message. The inclusion of the condom was a direct reference to AIDS prevention, meant to be evocative and arresting.

Additional key artifacts from the event include buttons featuring a pink triangle and the phrase “SILENCE = DEATH,” which were distributed at the protest, and leaflets thrown into the air that

highlighted key facts about the AIDS epidemic. David Lacaillade recounted his firsthand experience of the protest. Renting a limo and tuxedo, he managed to sneak into the Shrine Auditorium. In front of the orchestra pit, he stood up and yelled, “AIDS ACTION NOW! 102,000 DEAD! PEOPLE ARE DYING!” before being seized by security. The audience “never had a chance to consider Lacaillade’s message, because he had fallen victim to an age-old Hollywood axiom: ‘What the camera doesn’t catch does not exist’” (Green). Even more disappointing, the three actors who wore “SILENCE = DEATH” buttons provided by ACT UP— Bruce Davison (star of the 1989 AIDS-focused film Longtime Companion), Tim Robbins, and Susan Sarandon— did not make it on camera either. Interestingly, Susan Sarandon removed hers— whether freely or at the behest of a publicist is unknown–before she accepted her Oscar, so none were seen on screen (Gallagher). “Three out of a thousand! But at least not zero,” commented Lacaillade (Green).

Following the disappointing results of the first protest, ACT UP returned to the Oscars in 1992. This time, the focus broadened to the harmful films with numerous gay antagonists and harmful stereotypes nominated that year, such as Basic Instinct (Verhoeven), The Silence of the Lambs (Demme), and JFK (Stone). These films portrayed queer people as dangerous or untrustworthy, focusing their archetypes on their sexualities and in an overall negative light (Broerman). Some progress, however, was made following the initial 1991 protest. At the 1992 Oscars, more actors publicly wore red ribbons to show support for AIDS awareness, including Oscars host Billy Crystal (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences). The year after the second protest, steps toward progress were finally visible with the release of Philadelphia (Demme), the first major Hollywood film about AIDS. Starring Tom Hanks, the film was based on the true story of a lawyer with AIDS and was a significant milestone in mainstream awareness.

During the 1991 protest, ACT UP sent letters to various Hollywood figures. In one letter to Johnny Depp, activists outlined the “Six Sins of Hollywood”: homophobia, misogyny, racism, no positive

portrayal of people with AIDS (PWAs), classism, and refusal by entertainment figures in Los Angeles to condemn the murder by local officials of PWAs (ACT UP Los Angeles). This emphasis on representation remains vital. Representation in film has made progress, with more LGBTQ actors, characters, and storylines today, but these depictions must evolve beyond stereotypes and superficial inclusion. Stories should reflect the richness of people’s lives, allowing audiences to connect on a basic, human level, regardless of background or identity.

Since the protests of 1992, there has been progress on queer issues, yet opportunities for improvement remain. Following the release of Philadelphia (Demme), films about AIDS became more mainstream. Many credit the musical RENT (Columbus) as the first time they saw AIDS portrayed in the media. Other films, such as It’s My Party (Klieser) and Dallas Buyers Club (Vallée), focused on main characters with AIDS (Broerman). However, these roles were often played by straight, White men, which alienated many queer individuals from seeing themselves represented in these stories. Protests for better LGBTQ representation in Hollywood continue. More recently, nonbinary actor Liv Hewson of Yellowjackets (Lyle and Nickerson) declined to submit their name for Emmy consideration in 2023, telling Variety that “there’s no place for me in the acting categories” (Zuckerman). This highlights the ongoing evolution of Hollywood’s acceptance and the distance still left to cover.

I want a future where storytelling in film transcends identity labels and instead focuses on the universal experiences that connect us all. Filmmakers should allow audiences to connect on a basic, human level, regardless of background or identity. By focusing on human experiences and journeys, stories can resonate broadly and inspire empathy without capitalizing on differences. I hope these stories shed light on the fight to spread AIDS awareness and eliminate the stigma. Hollywood’s immense influence in shaping opinions and perceptions can be incredibly powerful and incredibly dangerous; it must be used responsibly. To me, a queer future looks like acceptance, visibility, and normalcy.

Harmful stereotypes must be erased for this to become reality. I hope that in 50 years, the Youth Ambassadors will study this era as a reminder of how far we’ve come—and how much progress is possible when acceptance and representation are simply a normal part of life and art.

Piper, 17, responds to a letter from "Miss A," a homosexual woman from New Jersey, who wrote to ONE in March 1956. Miss A praises ONE Magazine, particularly “The Feminine Viewpoint” issue from February 1954, the only issue created by and for queer women. Nevertheless, she challenges ONE to provide more coverage of homosexual women: “Why have just an occasional issue for women? I’m sure you’re not prejudiced against us... Please, don’t neglect us.”

Briggs

Sadie Davis, she/her

Against the politically-divisive backdrop of the 1970s, California State Senator John Briggs proposed Proposition 6, dubbed the “Briggs Initiative.” The statewide ballot measure proposed that all openly gay men, lesbians, and supporters of the queer rights movement be banned from working in California public schools. In response, Harvey Milk, an openly gay member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, teamed up with lesbian activist and teacher Sally Gearhart to form a campaign against Prop 6. Largely due to their campaign— which brought together a coalition of activists, unions, and even prominent politicians, including previous California governor and future president Ronald Reagan—the proposition was voted down by over 1 million votes, against the 2.8 million who voted for it, on November 7th, 1978 (Goldberg).

The work of the grassroots organizations who fought the initiative remains a model for effective campaign advocacy today when, in 2024 alone, over 750 pieces of LGBTQ+-related legislation have been introduced or are pending in state legislative sessions (Human Rights Campaign). As a current queer high school student—in the setting at which most of these bills are targeted—I understand profoundly the value of having LGBTQ+ teachers with whom I can connect. I also am deeply aware of the merit of an education that highlights queerness rather than erases it, something I have learned in the Youth Ambassadors for Queer History program at One Institute. As queerness and transness is being erased from schools by legislatures and courts across the country, I utilize a short documentary film to examine how the Briggs Initiative influenced current anti-LGBTQ+ legislation and what our community can learn today from the successful campaign against it.

From my research in the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, I learned that one reason the campaign against Briggs was so successful was that it appealed to average voters; the campaign portrayed Briggs as not a gay issue but an issue of personal and

worker rights. For instance, organizers hosted a “State-Wide Workers Conference Against Briggs,” which was advertised “for straight, gay, organized and unorganized workers.” In the flyer for this event, it is written that not only does Briggs “scapegoat” gays but that it will eventually lead to “a network that will attack all working people” (East Bay Area Coalition Against the Briggs Initiative et al.). Clearly, the strategy was to appeal to the largest number of voters possible. Furthermore, a newspaper clipping from 1977, contains a picture of a seemingly-normal classroom with the caption “Gay Teacher in Action,” thus destigmatizing the idea of gay teachers by presenting it as normal and even wholesome (Ramirez).

On the other hand, when analyzing materials used by the proBriggs coalition and other related conservative movements, I found blatant fear mongering, aiming to divide America between gay and straight. The pro-Briggs campaign drew upon the well of anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment, which was reinvigorated in the wake of out-and-proud gay rights movements around the country in the 1970s. Briggs was clearly inspired by the successful “Save Our Children” campaign, appealing to Christians worried that their children could be recruited by gay adults (Eugenios). In one 1977 newspaper article from The Torch, a heading reads “GAS GAYS” with subheadings of “Homosexual attacks on children are increasing” and “Save our children from homosexuals!” The article argues openly that “all homosexuals” deserve “execution” simply for existing (White People’s Committee to Restore God’s Laws). Similarly, other archival materials such as a mail-in petition to preserve “Bible Morality in America” through compulsory Bible lessons in public schools and banning queer teachers show how the Briggs Initiative corresponded with the Christian religious culture in America at the time (Todd). It is evident not only how eerily familiar the conservative rhetoric during the 1970s is to the present day but also how the anti-Briggs queer rights organizations appealed to humanity and logic while conservatives, such as the Briggs campaign, appealed to fear and anger.

With a second Trump administration in action, it is striking how similar the rhetoric behind the Briggs Initiative and “Save Our Children” is to rightwing politics in modern day America. Donald

Trump himself has already, in the few weeks he has been in office, repealed Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) policies for transgender people in the military, signed an executive order claiming gender identity will no longer be recognized because there are only “two sexes, male and female” and signed an executive order to restrict gender-affirming healthcare for those under 19 (Alfonseca; Archie; Burga and Lee). Likewise, from 2018 to 2023, a record-breaking 100 anti-LGBTQ+ laws were passed in state legislatures (Radcliffe and Rogers). While the majority of these bills were not passed by popular vote like Briggs, the public still exercises a significant degree of control over whether they are able to pass because we choose who to elect. At the moment, many Americans are voting for elected officials who are committed to passing bills which will further discriminate against the LGBTQ+ community.

One such bill that has been passed recently is Florida’s infamous “Don’t Say Gay” bill in 2022, which bears many similarities to Briggs. It forbids public school teachers from so much as mentioning anything related to sexual orientation or gender identity (Diaz). Because of this policy, the bill essentially implies that exposing students to queerness is inherently immoral and wrong. Both Briggs and Don’t Say Gay have been politically legitimized under the guise of “Parental Rights,” but only for parents who view being LGBTQ+ as a crime. However, recent anti-LGBTQ+ legislation is compounded in a way Briggs was not by the fact that it is often accompanied by book bannings, severely restricting race-related courses, and the fact that most bills are targeted at detrimentally affecting students. While Briggs would have harmed queer students who needed older role models to look up to, it was not aimed at directly policing LGBTQ+ youth’s identities. Also, modern bills are disproportionately targeted at trans youth who become in turn even more at risk of persecution and mental health difficulties. Given the legal protections that have recently been afforded to queer people in America (for example, marriage equality and anti-discrimination legislation), it is clear that right-wing politicians have refocused their vitriol onto trans people due to their status as a more marginalized and less legally safeguarded group within the LGBTQ+ community.

The legacies of those involved in the fight against the Briggs Initiative have evolved over time just as legislation has. Harvey Milk is viewed as a trailblazer of queer representation in government now that we had over 1,300 LGBTQ+ elected officials nation-wide last year (LGBTQ+ Victory Institute). However, his legacy is depleted by the fact that he was assassinated mere days after Briggs was defeated and less than a year after his initial election. With all the progress Milk made with only a year in office, it is tragic to imagine all the good he could have done for the community if not for his assassination.

As mentioned, when Briggs was defeated, there were incredibly few queer politicians in the USA and queer rights were in their relative infancy. Now that we have made strides in both of those areas, I am confident that we can defeat similar legislation again. The queer community has always faced persecution and has experienced worse than what we are going through now, so there is no doubt in my mind that we will overcome the current wave of anti-LGBTQ+ persecution just as we have always done in the past.

To do that, we, especially the younger generation, have to fight for our basic right to education. We also must learn about our community’s long history of resilience so that we understand how to fight bigotry and discrimination in modern day successfully. In 50 years, I want Youth Ambassadors for Queer History to learn about how our generation rose above adversity to protect our fundamental educational rights. I want them to learn how we fought to give them an education where they are not subject to book bannings, targeting queer students and teachers, and can express their identities in school without fear of intolerance or outing. To eventually achieve this goal, the first step for me was to analyze how California’s activists combatted flagrant homophobia, fearmongering, and scapegoating through effective, compassionate grassroots organizing in 1978. The next steps are to teach others what I have learned and to apply these lessons to my community.

Link to film: tinyurl.com/briggsshortfilm

Sadie, 16, responds to a letter from "Ray," a 16-year-old from Michigan who wrote to ONE in February 1964 Ray thanks ONE for pointing him towards Christ and the Homosexual, which has helped with self-acceptance; he imagines liberation: “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if homosexuals today could walk with head high, proud of the fact– instead of hiding in the dark crevices of society like Medieval monsters?” Ray advocates for the youth involvement in the homophile movement, given the 21+ age restrictions on ONE Magazine: “The gay teen agers will be the leaders of the movement– why are we excluded from it today when it could help so many?”

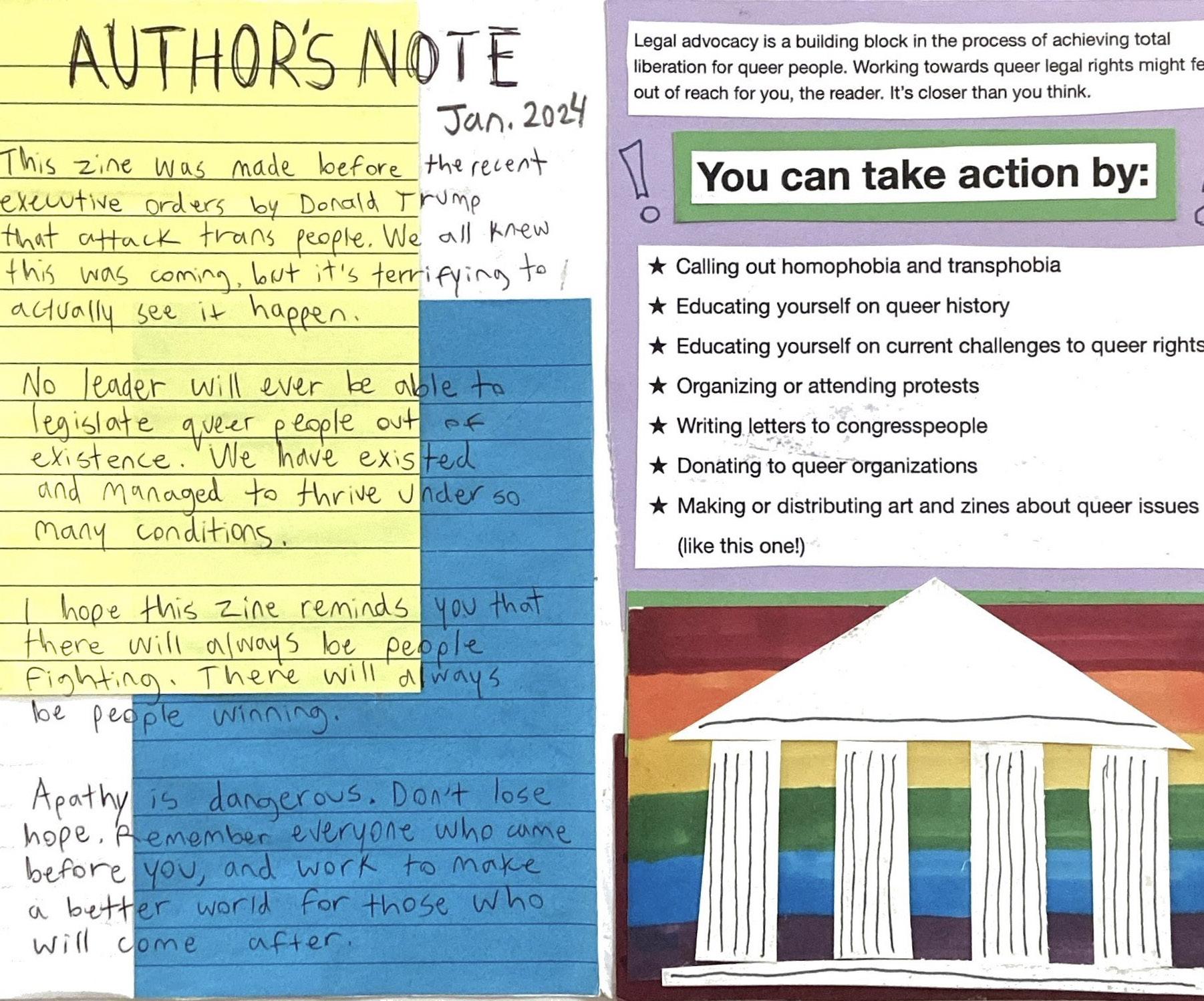

Created Equal: A History of Queer Legal Victories

Simon Ashford, he/him

As an aspiring lawyer, I am fascinated by the workings of the legal system and how it can be improved for marginalized communities. As a trans person navigating a legal name change and constant debates about my right to exist, queer legal issues hit close to home. Using historical documents, photos, and my own comics, I hope to informatively and creatively explain landmark legal victories for the queer community. My zine—“Created Equal: A History of Queer Legal Victories”—showcases how queer people have advocated for legal rights from the 1950s through the present.

In researching the Lynn Edward Harris papers from the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, I learned that Harris was an intersex individual who won a California Superior Court victory to change his legal name and gender in 1983. This case was particularly impactful because he was the first person to change his name and gender without proof of gender-affirming surgery. At the time, gender transition was thought of as only complete after a “sex change” surgery. Harris, although raised female, wanted to live and be recognized as a male. As an intersex person, he already had the traits that he felt he needed to be a man. After his initial petition for a male birth certificate was rejected for a lack of medical evidence, he continued fighting. Eventually, he won Superior Court approval for a gender and name change without a sex change (Hawkins).

Harris was a pioneer, expanding the definition of trans past the binary, medicalized ideas so popular in the late twentieth century. He collected resources about trans legal battles, including information about hormone access in prison and the importance of legal recognition of trans identity (Whittle “Legislating for Transsexual Rights”). I found his collection of books about legislating for transsexual rights, like legal sex and gender changes, fascinating. Seeing Harris challenging the rigid definitions and laws around trans people inspired me. Today, as

people attempt to gate-keep transness and make it impossible for trans people to live comfortably, it is important to remember Harris’s work. Harris’s case serves as a reminder of the strides queer people can make towards achieving respect under the law.

Beyond Harris, my zine highlights a number of impactful Supreme Court cases for the LGBTQ+ community. One, Inc. v. Olesen (1958), which ruled that speech in favor of homosexuals is not inherently obscene, broke legal barriers that prevented queer people from organizing and sharing information under the First Amendment (Zonkel). Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), which ensured the right to gay marriage, overrode discriminatory state laws in favor of more equal federal laws under the Fourteenth Amendment (Cornell Law School). Finally, Bostock v. Clayton County (2020), established protections against workplace discrimination based on sexuality or gender identity, citing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Davidson). These foundational cases demonstrate how queer activists have shown that the Constitution includes queer people. Drawing parallels to current events, I examined the pending case United States v. Skrmetti (2024), which will determine legal protections for hormone replacement therapy and gender-affirming surgery for minors, and its implications for trans youth. As the moral panic of conservatives begins to focus on trans people, legal battles shift too. This case forces the Supreme Court to directly consider the Equal Protection Clause’s applications to gender-affirming care for minors (Redfield).

The ongoing attack on queer and trans rights by our government raises the importance of remembering the histories of how we have pushed back and won. My project has made me think about the dedication queer activists have given to the fight for free speech, protection against discrimination, and bodily autonomy. Looking at archival sources in the ONE Archives— like magazines, photos, and books— motivated me to continue my advocacy for my community.

Link to full zine: tinyurl.com/YAQHCreatedEqual

Lost Latino History

Kim, she/her

My project exemplifies the activism that LGBTQ+ Latino individuals contributed to significant political progress in the 1960s to the present. As a LGBTQ+ Latina individual born in 2009, far-reaching activism from Latino LGBTQ+ groups in the late twentieth century has directly shaped my life today. They were responsible for not only bridging the gap between the LGBTQ+ and Latino communities, but providing a safe space for LGBTQ+ Latino youth who struggled to find support in their households. Overall, the impact that it has made on me is immeasurable; without their activism, perhaps I would not feel as comfortable in my own skin.

For my research, I used a variety of archival sources from the collections at ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. I explored materials on Latina lesbians from the ONE Subject Files collection with different types of prints that demonstrated the fight for LGBTQ+ and human rights, including cards or meeting minutes from LGBTQ+ groups, invites to lesbian parties, and political activism letters sent to Central and South American politicians. For example, the Gay and Lesbian Committee of the Echo Park Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES), in a 1983 letter asking for collaboration between CISPES and Christopher Street West Gay Pride, issued the powerful statement: “The only common view which we should agree to unite around is ‘Stop U.S. Intervention in El Salvador.’” This letter highlights the political aspect of Latino LGBTQ+ organization’s activism, and the significant role they took in making lasting change in many Latin-American countries, such as promoting anti-imperialism and lasting peace among LGBTQ+ groups and the heterosexual population. Artifacts like this one reveal the central role of activism in many People of Color (POC) LGBTQ+ communities, specifically political and humanitarian activism, which was a focal point of many of these groups.

Building a community that feels welcoming to all individuals was a significant goal that many Latino LGBTQ+ organizations sought to achieve. An article titled “Lesbian Scare as Latin Feminists

Gather” by Tatiana de La Tierra, published by Lesbian News (LN) in 1994, described the adamant homophobic disapproval of CISPES’ involvement in the Feminist Convention in El Salvador. De La Tierra details the significant hatred that many LGBTQ+ groups, especially those in Latino spaces, encountered. Eventually however, the bond between the women that were a part of this conference overshadowed the hatred. Another significant source I found was a flyer from Gay & Lesbian Latinos Unidos (GLLU), founded in Los Angeles in 1981, which described the mission statement of their organization: “a political, cultural, social and consciousness- raising organization whose purpose is to unite the gay and lesbian latino community of the Los Angeles area for a better life and future” (“Join Us!”). GLLU was open to LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ people (“Join Us!”). The organizers wanted to create an equal and peaceful relationship between Latinos and the LGBTQ+ community, two cultures who often clashed, and still do today. This source is a pivotal piece in understanding the impact of organizations that prioritized People of Color and creating lasting positive relationships, promoting intersectionality.

Individuals also stood out in the lasting impact of their activism. Sylvia Rivera, a prominent AIDS and Gay Liberation activist, was a tireless advocate for those silenced and disregarded by larger movements. Rivera— a Puerto Rican and Venezuelan-American transgender woman— was a key protester during the Stonewall Riots; she fought for the rights of countless people, including by founding Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) for trans street youth (Brewster; Rothberg). After her death, the Sylvia Rivera Law Project has continued her legacy, working diligently to erase the consistent discrimination, violence, and harassment that many LGBTQ+ individuals, especially transgender and nonbinary people, face (Rothberg). As a closested individual, my research holds a unique place in my heart; not many people know about my sexuality, and I don’t intend for anyone to find out. However, through research, I discovered that for many, their sexualities were not determinant for what they advocated. Despite the central theme of LGBTQ+ advocacy in these groups, many of them oftentimes focused also on issues such as human rights, immigration, HIV/AIDS awareness. Despite being excluded from certain groups, LGBTQ+ activists of color fought harder for their voices to be heard. Their legacy, including Rivera’s work with the

Sylvia Rivera Law Project (SRLP), continues to inspire progress today.

My project provides insight into the history and contributions of Latino LGBTQ+ activists in the late 20th century. This period laid the groundwork for continued activism today, influencing organizations like Familia: Trans Queer Liberation Movement, which “works at local and national levels to achieve the collective liberation of trans, queer, and gender nonconforming Latinxs through building community, organizing, advocacy, and education” while also enhancing the struggles and accomplishments of many Latino LGBTQ+ individuals in continuing the fight for equality (“Familia: TQLM…”). Only by recognizing our shared struggles can we move forward together to create a more inclusive future. In fifty years time, I hope that LGBTQ+ people will no longer feel ashamed of themselves, that they will have the confidence to be themselves, and that they will recognize that they can be so much more than just a silhouette in the background. That it was what so many Latinos and other POC fought for—our striking presence.

Kim, 15, writes a fictionalized letter to the editors of ONE from "Sarah," a high school cheerleader living in Wisconsin in 1972. Sarah's letter represents the scores of young homosexuals who wrote to ONE from across the United States, often detailing their own personal experiences with family, religion, and relationships; seeking advice; and thanking ONE for its coverage of gay issues, even as the magazine was restricted to ages 21+ for legal protection.

Innocence

Kim, she/her

Her body was a temple, Decorated with relics

You saw not the sacred, nor the hymns within,

Till you chose to desecrate, and raid her with sin

You weren’t there to worship,

You weren’t there to pray

Your pithy excuses were no match for the game you played

You plundered the entrance

You looted without any remorse,

You desecrated the shrines

You took her offerings

Her innocence was destroyed

Yet they told her, this was God’s plan

They say it wasn’t his fault

It was meant to be destroyed by a man

Her cries of anger cover her cross

She weeps in silence---God is not around to listen

They refuse to acknowledge

They refuse to understand

I was that angel

I was that temple

I no longer call myself holy

I no longer am

We must call out these unholy men, Put them on the stand, let truth be laid

Expose the havoc their hands have made

If the angels’ cries aren’t heard,

We will never stop the desecration Never let this destruction be repeated, And hope heaven will soon be greeted

Works Cited

Works Cited

Oh My God… They’re Lesbians!

Bak, Sunny. “Ohmigod... they’re lesbians!”. 1995. Coll2013-037 Sunny Bak Photography collection, box 1. ONE Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries, Los Angeles, CA.

Biron, Joan E., et al. Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians. Anthology Editions, 2021.

Corinne, Tee A. “When There Were No Images: The Remarkable Achievements of JEB.” Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians, by Joan E. Biron, Anthology Editions, 2021.

“Finding aid of the Nancy Rosenblum Photographs.” Online Archive of California, oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ ark:/13030/ kt396nd93t/. Accessed 18 Jan. 2025.

Flash, Lola. Introduction. Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians, by Joan E. Biron, Anthology Editions, 2021.

Keyes-Levine, Maddie. E-mail interview with the author. 14 Jan. 2025.

Lindsey, Lori. Afterword. Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians, by Joan E. Biron, Anthology Editions, 2021.

“Mary Whitlock & Nancy Rosenblum.” LiveJournal, 31 Aug. 2015, elisa-rolle.livejournal.com/2343513. html. Accessed 18 Jan. 2025.

Rosenblum, Nancy. Some of My Best Friends... Portraits of Lesbians exhibit description. 1983. Coll2008-048 Nancy Rosenblum Photographs, box 1:7. ONE Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries, Los Angeles, CA.

Rosenblum, Nancy. #52 -Joan Boisclair. 16 July 1983. Coll2008048 Nancy Rosenblum Photographs, box 1:6. ONE Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries,

Los Angeles, CA.

Rosenblum, Nancy. #54 - Pamela Hamanaka. 1984. Coll2008-048 Nancy Rosenblum Photographs, box 1:7. ONE Archives at the University of Southern California Libraries, Los Angeles, CA.

Schwarz, Judith. “Lesbian Photography: A Long Tradition.” Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians, by Joan E. Biron, Anthology Editions, 2021.

Works Cited

Painted Queens: A Century of Drag Makeup

Boswell, Holly. “Gender Unmasked,” Transgender Tapestry, no. 87, Summer 1999, p. 54-56. Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at University of Southern California Libraries, Los Angeles, CA.

Comer, Jim. “Rite, Reversal, and the end of blackface minstrelsy,” Jim Crow Museum, https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris. edu/links/essays/comer.htm#:~:text=Minstrel%20 Transvestites&text=As%20early%20as%201843%2C%20 in,dancing%20and%20flirting%20with%20everyone. Accessed Feb. 2025.

Daughters of Bilitis. The Ladder, vol. 2, no. 1, Oct. 1957. Periodicals collection, ONE Archives at University of Southern California Libraries, Los Angeles, CA.

Dotson, Bill. “Project Underway to Digitize Mattachine Society and ONE Inc. Records,” University of Southern California Libraries, 27 July 2018, https://libraries.usc.edu/article/ project-underway- digitize-mattachine-society-and-oneinc.-records#:~:text=The%20Mattachine%20Society%20 traces%20its,forced%20to%20hide%20behind%20masks. Accessed Feb. 2025.