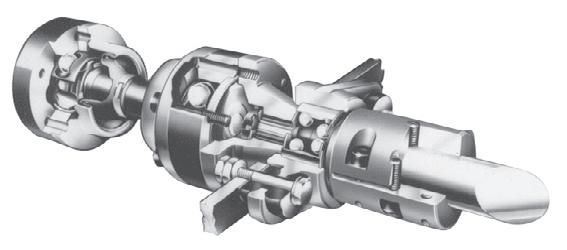

Velocity. Trimmers feel an increase first…before the numbers confirm. Using sheet as speed barometer, they’re also the first to know when pressure softens. And they respond. The 7 ceramic ball bearings in a new Zircon block overcome inertia from friction so easily, information flows acutely through the sheet. Simply put, trimmers feel and better match sail shape to the new condition–often the difference between winning and not. At top wind ranges, you need more purchase to trim harder. Go for it. When the breeze backs off, Zircon blocks let you ease… even through all those sheaves.

Andy Cross

By Meredith Anderson

By Marty McOmber

By David Casey

By Lisa Mighetto

Andy Cross

By Meredith Anderson

By Marty McOmber

By David Casey

By Lisa Mighetto

Cruising means something a little different to everyone. There are as many unique definitions as there are cruisers out chasing their dreams. Thankfully, the waters of the Pacific Northwest accommodate pretty much any cruising incentive.

I can recall my first experiences at some of the Salish Sea’s most famous and wellloved cruising gems, the heavy-hitter short-list of can’t-miss destinations. Each offered ample wonder and was entirely new to me. Each quickly revealed why they sit atop the PNW cruising-stop pyramid, drawing boaters back year after year with incredible beauty and rich shoreside attractions, natural or otherwise. Also, each offered crowds of breathtaking scale, for cruising anyway — snug anchorages, only a faint hope of dock space or mooring buoy availability, well worn paths ashore, and an inevitable community-living experience. Were those visits fun? Will I go again? Did I learn something about what motivates me as a cruiser? Heck yes, all around.

For me, and for the cruisers whose approaches resonate most with me, there's a desire to get off the beaten path, even in my home waters. In this age when information is so readily available, it can feel like there’s nothing left to discover. Still, I’ve found that it takes only a small effort to find your way to a much more remote version of cruising.

At the risk of a tantrum about algorithm-driven content, my impression on and off the water is that the ways we access information today tend to lead large percentages of folks to small percentages of the destinations. This has always been somewhat true with cruising guides, but I think the recommendations become more distilled through modern vehicles — in part because it is so much easier to happen upon the same suggestions that your dock mates have also seen (sometimes by design), and because authoritative-seeming resources can make you think you’ve tapped into curated expertise without needing to delve any deeper. These resources have value and serve their purpose. Importantly, though, they come with an encouraging reassurance: as some resources funnel throngs toward certain locations, alternative options are nearby and innumerable. Cruising guides are actually excellent resources to help you find these unsung alternatives.

Keep an eye out for situations when conventions and best practices limit awesome possibilities. There’s an obvious example in this issue (page 30), in which Washingtonbased cruisers decide to sail back from Alaska by foregoing the typical Inside Passage route. Yet, it need not be such a major adventure to capture this spirit. Think about “situationally great” anchorages. Truly ideal anchorages will have terrific protection if a storm comes from nearly any direction. However, some of my favorite nights on the hook have been in places where we go to sleep knowing that if some unforecast breeze comes in from the wrong direction, we will probably have to move. It’s tough for these places to make the top-ten lists, because they aren’t right for most folks in most situations. Nevertheless, they were magical to me.

Pacific Northwest boaters’ access to a range of cruising experiences is second to none — including some spots so remote and extraordinarily beautiful you’ll wonder why people aren’t there in droves. Happily, opportunities abound on our waters for cruisers seeking the course less traveled.

I’ll see you on the water Joe Cline, Managing Editor, 48° North

Volume XLII, Number 10, May 2023 (206) 789-7350 info@48north.com | www.48north.com

Publisher Northwest Maritime Center

Managing Editor Joe Cline joe@48north.com

Editor Andy Cross andy@48north.com

Designer Rainier Powers rainier@48north.com

Advertising Sales Kachele Yelaca kachele@48north.com

Classifieds classads48@48north.com

Photographer Jan Anderson

48° North is published as a project of the Northwest Maritime Center in Port Townsend, WA – a 501(c)3 non-profit organization whose mission is to engage and educate people of all generations in traditional and contemporary maritime life, in a spirit of adventure and discovery.

Northwest Maritime Center: 431 Water St, Port Townsend, WA 98368 (360) 385-3628

48° North encourages letters, photographs, manuscripts, burgees, and bribes. Emailed manuscripts and high quality digital images are best!

We are not responsible for unsolicited materials. Articles express the author’s thoughts and may not reflect the opinions of the magazine. Reprinting in whole or part is expressly forbidden except by permission from the editor.

SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS FOR 2023! $39/Year For The Magazine $75/Year For Premium (perks!) www.48north.com/subscribe for details.

Prices vary for international or first class.

Proud members:

THE PARTIES ARE BACK!

"Race

in Anacortes

our expectations in every way."

Spencer Kunath, Navigator TP52 GloryPhotos by Jan Anderson

Praise for the Hood Canal Article in the March Issue

Hello 48° North team,

Please let Wendell Crim know that I enjoyed his article, “Transiting the Hood Canal Bridge.”

Two years ago, we decided to venture into Hood Canal with our Outbound 44. I really didn’t like the idea of stopping traffic but we also really wanted to explore Hood Canal, so we made our opening reservation and hoped for the best. As we transited through, and we looked at all the stopped cars, my husband playfully texted our friend who lives in Port Ludlow, “We just stopped the traffic on the Hood Canal Bridge and are passing through. I hope you are not on the bridge!” Seconds later our friend responded, “In fact I am. I am returning from a doctors appointment.” Oops!

It was fun to explore Hood Canal, but I probably won’t do it again (our mast is 63 feet from the waterline), for the same reason I won’t transit the ship canal into Lake Union from the Sound anymore unless I have to. I’ve been stuck on the Ballard bridge too often! Anyway, good article. I really appreciate the calculations Wendell offered for smaller boats than mine.

Elena LeonardBeta Marine West (Distributor)

400 Harbor Dr, Sausalito, CA 94965 415-332-3507

Pacific Northwest Dealer Network

Emerald Marine

Anacortes, WA • 360-293-4161

www.emeraldmarine.com

Oregon Marine Industries Portland, OR • 503-702-0123

info@betamarineoregon.com

Access Marine

Seattle, WA • 206-819-2439

info@betamarineengines.com

www.betamarineengines.com

Sea Marine

Port Townsend, WA • 360-385-4000

info@betamarinepnw.com

www.betamarinepnw.com

Deer Harbor Boatworks

Deer Harbor, WA • 888-792-2382

customersupport@betamarinenw.com

www.betamarinenw.com

Auxiliary Engine

6701 Seaview Ave NW, Seattle WA 98117

206-789-8496

auxiliaryeng@gmail.com

Response to Jaelyn Wielbicki’s article “Preparing Our Mental Health for Success at Sea” from the April Issue

Hi 48° North,

Nice article about mental health preparedness! Well done and accurate. Good to see consciousness raising about this very important topic.

Thanks,

The crew from Olympic Adventure Ketch, S/V Galapagos littlecunningplan.com

Everett Sea Scouts Thank Their Supporters

Dear 48° North,

I had the pleasure of speaking with one of your representatives at the boat show about the possibility of publishing a “Thank You” message in 48° North to all the local businesses that support our Sea Scouts. As a 501c3 Non-profit organization, we greatly value the support we receive from our community and we would like to express our gratitude to the local businesses that make our mission possible.

Best regards,

Mike BellgardtSkipper, Everett Sea Scouts Ship 226 Constellation everettseascouts.org

48° North has been published by the Northwest Maritime Center (NWMC) since 2018. We are continually amazed and inspired by the important work of our colleagues and organization, and dedicate this page to sharing more about these activities with you. 48° North is part of something bigger, and we believe the mission-minded efforts of our organization matter to our readers.

Every corner of Northwest Maritime Center's (NWMC) Port Townsend campus is abuzz with activity. There's no offseason at NWMC, to be sure, but spring brings the inevitable feeling of revving-up to the Boatshop, the classrooms, even the office spaces have a different vibe as sunny summer approaches.

Big drivers of enthusiasm around NWMC at this time of year — and a unique and comparatively new way that the nonprofit's mission is served — are the fun and inspiring adventure races created by NWMC: Race to Alaska (R2AK) and Seventy48.

These races start in early June. In addition to the incredible adventurers who race, these events have become a flagship pathway for anyone who loves stories of human accomplishment, perseverance, and wonder to connect with NWMC's mission through the awesome experiences of those who undertake these journeys. It's about as good as it gets for those who are passionate about boats and the waters of the Pacific Northwest too!

Seventy48 is a human-powered boat race, running 70 miles between Tacoma and Port Townsend. The race begins on Friday evening June 2 on Tacoma's Foss Waterway, and this year's

EVENTS CALENDAR » www.nwmaritime.org/events

OUTBOARDS:

MAINTENANCE, CARE, AND TROUBLESHOOTING

May 6

NWMC Boatshop

NO IMPACT DOCKING

May 9-10

Online Class

RULES OF THE ROAD AND AIDS TO NAVIGATION

May 23-24

Online Class

ELECTRONIC NAVIGATION & VHF

May 30-31

Online Class

largest-ever fleet of more than 125 teams will have 48 hours to make it to Port Townsend. The organizers invite you to "Come and watch the horde row, paddle, pedal, and pray their way north for 48 hours of glory." Fans may attend in-person at the start or finish lines, or follow the online tracker and social media updates.

Most 48° North readers will be familiar with the Race to Alaska. While it has generated genuinely worldwide acclaim, the core fan base is right here in the Pacific Northwest. Started in 2015, the R2AK is 750 cold-water miles of unsupported engineless racing between Port Townsend, WA, and Ketchikan, AK, with a stopover between legs in beautiful Victoria, British Columbia.

This year's R2AK promises the same rich, rugged waterwilderness as ever, with dozens of new teams and characters any fan or follower will find fun, engaging, and inspiring. Come join the R2AK shenanigans in person at the Ruckus in Port Townsend on June 4, for the R2AK start in the wee hours of June 5, or in Victoria from whenever racers arrive until the Leg 2 start on June 8.

» www.r2ak.com | www.seventy48.com

LEARN TO SAIL! BASIC KEELBOAT COURSE

May 29 -June 2

June 5-9

July 10-14

July 17-21

NWMC Campus & Port Townsend Bay

RADAR, COLLISION AVOIDANCE, AND NIGHT NAVIGATION

June 13-14

Online Class

BUILD YOUR OWN SKERRY OR PASSAGEMAKER DINGHY FOR SAIL AND ROW

September 18-24

NWMC Boatshop

This year's Anacortes Boat and Yacht Show featuring Trawlerfest is a boating celebration produced in collaboration between the Northwest Marine Trade Association, Anacortes Chamber of Commerce, and Trawlerfest. Current and future boaters are invited to check out in-water and shoreside displays with hundreds of boats at beautiful Cap Sante Marina and neighboring boatyards.

Additionally, the show welcomes the return of Trawlerfest’s 25+ boating classes taking place May 16 - 20 at nearby walkable locations.

Stop in between 10 a.m. - 6 p.m. (Thursday, May 18 - Saturday, May 20) to stroll the docks of Cap Sante Marina at the Port of Anacortes. Enjoy exploring and learning about boats and yachts of all types and sizes.

» www.anacortesboatandyachtshow.com

D’Arcy Island Marine Park is a tiny 83-hectare park that was once used as a leper colony, and now invites visitors ashore to explore its interesting but sad past. The new mooring buoys will enhance access as anchoring is difficult due to rocks and kelp, with tidal currents and winds complicating matters. Day visitors may tie up free of charge while visiting. For overnight use, the cost is $14 per night from May 15 to Sept 30 and the maximum number of days per calendar year is 14.

The park offers seven wilderness/ walk-in campsites, picnic tables and a pit toilet. All services are available in nearby Sidney. Little D’Arcy Island to the east is private property, please respect it.

The BC Marine Parks Forever Society (MPFS) funded the project, which has been fulfilled by Parks Canada. MPFS has existed for 30 years and has contributed to the acquisition of desirable anchorages that have expanded the wonderful system of marine parks in BC that many boaters enjoy today. Additionally, MPFS has enhanced environmental protection and improved safety.

» www.bcmpfs.ca

Bellingham Yacht Club launches into the 2023 boating season on May 6 with an afternoon “Anchors Away” themed boat parade for all, which is preceded by a morning reception for members and dignitaries.

“We are all about social gatherings,” explained Commodore Cathy Herbold. “Whether at the Club during winter or on the water cruising or racing, we have fun and make new friends year-round. Since 1925 when the Club started with 50 members and 10 boats, friendships and social events have been who we are.”

“We have a full calendar of boating for 2023, and Opening Day marks the official season kick off,” explained Fleet Captain David Marod. “Check out the Club calendar for races and regattas as well as weekend and week(s) long cruises to Canada and Puget Sound. We have activities for boaters of every age, level, and interest,” Marod added.

Bellingham Yacht Club is the oldest yacht club in Bellingham. Located on the Squalicum waterfront, the facility has a full bar and event center which can be rented by the public. BYC invites you to join the opening day celebration!

» www.byc.org

A Northwest tradition for more than 40 years, the Perry Rendezvous is returning to Port Ludlow on August 18-20, 2023. The event is designed to celebrate Perry yachts and their owners, but anyone interested in great boats is welcome to attend. All are invited to come and meet Bob, and to tour a fleet of his beautiful creations.

Friday is an informal arrival day to meet and greet. Saturday’s schedule includes two guest speakers in the morning and a dock walk to look at the boats in the afternoon. A potluck dinner is planned for Saturday evening, which will be followed by live music and revelry. Sunday is your last chance to connect with newfound friends.

Perry boat owners are encouraged to bring their boat to the event, but arrival by car or private plane is also possible. For moorage info, please contact Port Ludlow Marina, and be sure to tell them you are part of the Rendezvous.

There is no charge for participation, but please send RSVPs to JLange1956@ gmail.com. Please include a contact email if you wish to be kept abreast of updates.

» Bobhperry@gmail.com

» JLange2010@gmail.com

Since 1984, Westside Marine has been a key part of Port Townsend's marine industry. Under the leadership of Randy Powers, the business followed a straightforward philosophy: stock top name brands, keep prices competitive, and provide great service. Westside secured dealership of Hewescraft boats, Yamaha motors and EZ Loader trailers, among other well-respected marine product lines.

When Randy began to think about retirement, he wanted to be sure new owners would carry on the legacy of Westside Marine — treat employees well and honor the relationships he’d established with manufacturers, suppliers, and customers. He saw that kindred spirit of integrity in the owners and staff of SEA Marine, a fullservice boatyard located at Point Hudson in Port Townsend. Westside Marine’s focus is outboard-powered recreational and commercial trailered boats; SEA Marine services sail and powerboats, commercial and larger vessels. The synergy between the two businesses is obvious and members of the maritime community have expressed appreciation that Westside will continue with local ownership.

» www.seamarineco.com

Waterline Boats, brokerage and dealership for Helmsman Trawlers, recently opened a new office in Port Townsend. The new location is already teeming with activity. Waterline Boats is excited to become a part of Port Townsend's seafaring tradition, which offers unparalleled access to expert marine tradesmen and tradeswomen.

At Waterline Boats, knowledgeable staff work to match the right mariner with the right boat. Waterline Boats Port Townsend is supported by the main office in Seattle and another in Everett. Between these three cooperative locations Waterline Boats has 10 highly experienced brokers ready to serve mariners. Waterline Boats Port Townsend is also a sales office and dealership for Helmsman Trawlers — rugged, safe, and reliable semi-custom trawler yachts ranging in size from 31 to 46 feet.

» www.waterlineboats.com

Cylindrical boat fenders have been around for decades and they haven’t exactly adapted to meet the needs of modern boat designs and types. From powerboats to sailboats, curved or flat hull shapes and rub rails and toe rails can make it difficult to properly position a fender on your boat. With this dilemma in mind, Mission Outdoors created SENTRY boat fenders, which rest flat against your boat and the dock, and have an integrated strap and cleat system that locks into place without the need to tie a knot. The fenders hug the contours of the hull and don’t roll around, providing reliable protection above or below the rub rail. Made with closed-cell foam, they are lightweight, extremely durable, and are easy to take on and off and stow. Measuring 22-inches by 9-inches by 5.5-inches, SENTRY boat fenders are available in four color options.

Price: $79.99 » www.MissionOutdoor.com

When a problem happens in open water, it is up to you to solve it, and if it’s a leak, you need a reliable solution that temporarily contains it in seconds so a permanent fix can be found. If you need to quickly seal hull impact leaks, accidental punctures, drain leaks, and fuel tank or line pin-hole leaks, most bungs, tapes, putties, or foam plugs aren’t ideal solutions. RuptureSeal Marine Emergency Leak Response Kits allow you to quickly handle leaks even on sharp, jagged, dirty, and uneven surfaces. Deployment of this industrial grade leak sealant is fast and easy, with no additional tools required. Simply compress the silicone pad into the rupture, pull back easily on the handle, and the seal is mechanically fastened in place. RuptureSeal protection lasts for up to 10 hours until a permanent fix can be made and is available in four sizes to address leaks from ⅛-inch to 2-inch by 6-inch holes.

Price: $29.95 » www.RuptureSeal.com

Whether you’re racing dinghies or keelboats, Gill’s Stealth Timer is ideal for starts on any race course, and is their most technical timer to date. The Stealth Timer has been designed with a digital compass mode that includes a “Course Shift” feature, allowing the wearer to quickly set a new heading. Offering the clearest definition full dot matrix display, it can be easily read, even in driving rain. Water-resistant up to 50 meters and shock and impact resistant, it has a 50 lap memory, recall lap time, and total time. In addition, the timer comes with four countdown modes, including vibrate mode for a silent countdown. The updated module mount with safety release also prevents accidental release during use. The timer has audible alert sounds and a “Sleep” mode to preserve battery life.

Price: $135.00 » www.GillMarine.com

The Georgia Aquarium is the only aquarium in the Western Hemisphere to have whale sharks.

Lake Nicaragua is the only freshwater lake in the world that’s home to oceanic sharks.

The giant freshwater stingray can grow to 16 feet long and six feet wide and has the longest stinging spine of any stingray.

Amatignak Island, part of the Aleutian Islands chain, is the westernmost point in the United States, while Point Barrow in Alaska is the northernmost point in the United States.

The United States spans 57 degrees of longitude.

Farmed seafood represents more than one-third of global seafood consumption.

1 Position of an anchor just clear of the bottom

Across

4 Rope used to control the setting of a sail

8 Serious hazard where cold temperatures combine with high wind speed

Down

1 Type of compass that finds the position of the sun in relation to magnetic north

1 Position of an anchor just clear of the bottom

2 Sends out

4 Rope used to control the setting of a sail

3 Snorkler’s equipment

8 Serious hazard where cold temperatures combine with high wind speed

9 Rope that ties something off 11 Ship initials

9 Rope that ties something off

4 Offshore ridge, 2 words

5 Distinctive period

6 Smidge

7 Steep cliffs

The first estimate of ocean depths by scientific methods was made in 1856 by Alexander Dallas Bache, a great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin and superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey.

1 Type of compass that finds the position of the sun in relation to magnetic north

2 Sends out

When word reached England that George Washington had died, ships in the English Channel fired a salute of 20 guns.

3 Snorkler's equipment

The only enemy of leopard seals are orcas.

4 Offshore ridge, 2 words

11 Ship initials

12 They are used to get the crew to safety if something happens to the main ship

14 Sound signals from a ship

10 Unwanted rodent

5 Distinctive period

Giant clams can live more than a century.

12 They are used to get the crew to safety if something happens to the main ship

13 Adjoin

6 Smidge

15 System of masts and lines on ships and sailing vessels

7 Steep cliffs

Hurricanes range in size from 50 to 1,000 miles in diameter.

14 Sound signals from a ship

16 Standing rigging running from a mast to the sides of ships

19 Area where a ship’s power is generated, 2 words

10 Unwanted rodent

17 Shine with a flickering light

16 Standing rigging running from a mast to the sides of ships

18 Played a TV show again

19 Where the sun rises

13 Adjoin

Ormond Beach in Florida has orange sand, the result of crushed and worn coquina shells.

23 Two way

24 ‘’Are you a man ___ mouse?’’2 words

19 Area where a ship's power is generated, 2 words

20 Things you don’t do, 2 words

15 System of masts and lines on ships and sailing vessels

21 Collects leaves from the lawn

22 Moved a canoe

17 Shine with a flickering light

Pfeiffer Beach in California contains purple sand, the result of manganese garnet deposits.

23 Two way

25 “Emeril Live” exclamation

26 Large sail flown in front of the vessel while heading downwind

23 Prevent

24 ''Are you a man ___ mouse?''- 2 words

25 Chesapeake and San Francisco

25 "Emeril Live" exclamation

18 Played a TV show again

19 Where the sun rises

27 Loudspeaker system, abbr.

26 Large sail flown in front of the vessel while heading downwind

28 Projection into the sea

29 Enjoy the sun

20 Things you don't do, 2 words

21 Collects leaves from the lawn

Pink sand beaches are found in the Bahamas, Bermuda, Crete, Indonesia, Barbados, and the Philippines, while Hawaii has red and black sand beaches.

» See solution on page 50

22 Moved a canoe

23 Prevent

25 Chesapeake and San Francisco

Let a handful of beach sand drizzle into a pile, and it will always form a cone with sides that are angled at 35 degrees.

27 Loudspeaker system, abbr.

Become a part of the 48° North crew! In addition to your magazine each month, with this exciting new subscription offering, you’ll also be supporting 48° North in a more meaningful way. But, warmed cockles are far from the only benefit. Others include:

• Discounts at Fisheries Supply Co.

• One free three-day to the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival ($40 value)

• 10% off of Northwest Maritime Center classes, excluding Sailing Club

• Discounts on registration fees for events

• Cool bumper sticker and decals.

• $75/year (additional fees for First Class forwarding or International)

JUST THE MAGAZINE, PLEASE:

Our standard subscription gets you 12 months of 48° North and its associated special publications (SARC, Setting Sail, and the Official R2AK Program).

• $39/year (additional fees for First Class forwarding or International)

INSTALL

Business or Pleasure, AquaDrive will make your boat smoother, quieter and vibration free.

The AquaDrive system solves a problem nearly a century old; the fact that marine engines are installed on soft engine mounts and attached almost rigidly to the propeller shaft.

The very logic of AquaDrive is inescapable. An engine that is vibrating

on soft mounts needs total freedom of movement from its propshaft if noise and vibration are not to be transmitted to the hull. The AquaDrive provides just this freedom of movement. Tests proved that the AquaDrive with its softer engine mountings can reduce vibration by 95% and structure borne noise by 50% or more. For information, call Drivelines NW today.

Don't

Whether

“A‑Northwest Legend for Over 25 Years”

The day has come to untie those dock lines and head out on the water. As you motor out of your slip, the last things you want to think about are repairs, spare parts, or what could go wrong. But things do happen and it’s in the best interest of the boat and crew to be as prepared as possible — carrying engine spares is a big part of that preparation.

There is a long list of spares we could choose to carry. Still, when I am helping out folks on the water, they often don’t actually have what they need. It is important to prepare for the type of cruising you’re planning to do, so you have the right tools and parts while you’re away from the dock. Knowing how to install these items with the correct tools is also critical, since a mechanic is seldom nearby; or if there is one, you aren’t forking out “vacation” prices for a simple service.

Preparation does begin long before you are underway. While oddball things can fail, an engine that receives proper maintenance and an annual inspection should avoid most issues. Many things that fail are due to neglect, not random failure. But if you want to enjoy the wonders of cruising in the Pacific Northwest, it means declaring your preparations complete and heading out — hopefully with the appropriate redundancies and resources.

The following recommendations about spare parts and tools are cumulative, so be sure to include the suggestions for shorter cruises even if you are cruising longer distances. Starting with a focus on near-coastal and inland cruising, here is what I recommend having aboard when you leave the dock.

Many folks choose to do short runs, whether it’s a day trip or an overnighter for the weekend. Being close to home does not mean you’re immune from running into trouble. While a very basic list, these issues are the most common that I come across when people call me with spring or summer emergencies. Assuming your engine is reasonably maintained as far as hoses and general servicing goes, having this minimum amount of spares will, in most cases, enable you to limp your boat home without a tow.

Rigid external oil lines can and will break from rust or chafe, if not inspected or maintained. I have also seen a few oil plugs/oil pressure sending units literally blow out. The typical result is that all the oil is lost in a matter of seconds.

It goes without saying that you cannot run your engine in that condition. Hopefully, you will be able to plug the hole to get them home, but in order to do so you must have spare oil on hand.

by Meredith AndersonEspecially if your boat has been sitting unused for a while, getting underway can stir-up algae and other crud in your fuel tank, mixing it with your diesel. As such, be prepared with one complete set of replacement fuel filters for whatever filterset you’ve already got. Having more than one of each is better, especially if the tank is dirty. Changing filters usually requires bleeding the fuel lines for the engine to run smoothly again, so there’s also a key skill that comes with these physical replacements.

Nothing stops the fun faster than no water coming from your exhaust. A failed impeller is easy to fix, as long as you have a replacement that fits your engine with you.

AT LEAST ONE OF EACH TYPE OF BELT THAT THE ENGINE MAY HAVE

Belts often go neglected and tend to break when used for the first time in a season. Also, it’s important to know how to change your belts and how much tension they should have.

For longer trips up to and beyond the San Juan and Gulf islands, it is important to bring a few more items. These beautiful places often bring you farther away from easily accessible parts and services, but not so far that you will be completely on your own when it comes to repairing the basics on your engine.

I tend to plan routes in such a way that I have checkpoints along the way to my destination. Though I know of various places to stop and buy or order parts if I need to, it’s best to have the basics covered, including tools to remove and install these things if I am at anchor with no one close by. Towing is truly a last resort, and waiting for parts at marinas far from your homeport is expensive.

The items below are things I actually carry while cruising

north each summer. Most of the larger maintenance items such as injectors, hoses, and exhaust elbows have hopefully been usually replaced throughout the year so they are not a problem while underway.

It is easy to find wire-reinforced or rubber hoses in many places around Puget Sound, but not so easy to find engine specific pre-bent cooling hoses, because most places do not stock these and will have to special order them. If a pinhole in the heat exchanger forms, you will likely need to replace coolant more often until the heat exchanger can be replaced. Additionally, hoses that have been on the engine for a long time will most likely be damaged in the process of removing them, so it’s handy to have these ready to go when taking on this project.

Faulty glow plugs can leave you stranded at random, inconvenient, or even dangerous times. Those of you with Universals, Westerbekes and more modern Yanmars will have glow plugs. Some of us will have a relay, and those are notorious for random failures. Carrying a butane heat gun can help diagnose this too and even get you started if you don’t have a relay on hand. My Universal diesel engine had this problem last summer and I had to use my torch for a few starts until I had the time to replace the relay at the dock.

Universal, Westerbeke, Kubota, and Nanni tend to use breakerstyle circuit protection that is mounted on the back side of the engine. Carry an extra if your engine has one. If you have a starting battery fuse or breaker, it is also a smart idea to carry a spare.

Don’t get stuck with a leaking raw water pump. While this is not a critical issue, a leaking pump can lead to further problems if you’re cruising for several weeks. Having a rebuild kit or a spare pump handy can save you problems later. If you’re using a rebuild kit, remember you will need a gear puller and a vice to pull the drive gear in some cases, and a vice to press the shaft out.

Starters can randomly fail and, while some engines have a hand crank, most don’t actually have enough access to use the handle. I have a used spare that is functional so I can slap it on and go.

An ill-maintained prop can definitely fail under load. Also, a good hit with a log or other obstruction can also take out a blade

or the whole prop. While you may be able to limp into a marina, it sure is nice to have the spare on hand so you don’t have to search and wait for one while at a guest slip.

What cruiser doesn’t love the freedom of being away from the dock? It’s the feeling we live for! Whether in the islands or closer to home, these adventures require elements of self-sufficiency. Having some essential spares for your engine, and the tools and know-how to employ them is a central aspect of nautical self-reliance. The list of spares above should ably cover Salish Sea cruising. If you’re headed to much more remote areas, including offshore, the parts list and skill set becomes more extensive — which I’ll discuss in my next column. With routine maintenance at home and few parts and skills, you’ll be able to focus on the fun of cruising knowing you’ve given yourself a simple safety net.

Meredith Anderson is the owner of Meredith’s Marine Services, where she operates a mobile mechanic service and teaches handson marine diesel classes to groups and in private classes aboard their own vessels.

For nearly 20 years, we kept a series of boats at our homeport, Elliott Bay Marina; the latest being our 1984 Passport 40 Rounder. A few weeks ago, I backed out of our slip on J Dock, pointed the bow down the fairway toward the massive breakwater that has held dozens of storms at bay, and began slowly passing familiar sterns with their familiar names.

How many times have I traveled this same path to sailing adventures near and far? How many evenings have we sat in the cockpit watching the lingering sunsets over the Olympic Mountains? How many times did I fall into conversations with perfect strangers about the weather, cruising plans, or the latest improvement project? How many harbor seals have popped their heads up to say hello? How many times have I paused under the little gatehouse roof at the top of our dock to enjoy the hanging flower baskets in summer, or for temporary relief from the wind and rain in winter?

There was no fanfare, no music, no goodbyes from neighbors or staff. I just quietly left our homeport, for good this time.

There are an endless number of topics we discuss and obsess about as boaters, from destinations and weather to motors, batteries, and the latest must-have technology. But the one topic that I haven’t given a lot of thought to is the marina where many of those topics have been discussed.

After all, for those who keep their boats in the water throughout the year, a homeport is the place where your boat likely spends most of its time — and for us, who have lived aboard for months at a stretch in the past, where we did as well.

Perhaps those of us who cruise a lot are conditioned to view marinas as transactional places. You pay someone to let you tie your boat up for a night or two while you run errands, fill the water tanks, and top up the battery bank.

But when you love the marina where you keep your boat, it becomes a far more meaningful place.

This idea dawned on me recently when, after decades of living in Seattle, we sold our townhouse and moved to a new house on Bainbridge Island. At first, we decided to keep the boat moored at Elliott Bay Marina with the assumption that we would use it as a little home away from home after a night out in the city or a visit with my mom just up the road in Ballard. My wife, Deborah, dubbed it our “pied-á-mer.”

But we found we used it as such far less than we thought we would. And we learned the hard way just how messed up the ferry service between Seattle and Bainbridge can be on weekends, when we typically wanted to visit the boat either to use it, enjoy it, or work on it.

When my mom passed away late last year, I just couldn’t see a good reason to keep the boat there any longer. I mentioned to Deborah that we could start looking for a marina on the west side of Puget Sound, closer to our home.

She wasn’t enthusiastic about the idea.

Our dating relationship had just become a serious relationship back in 2004 when we last switched marinas. I had lived aboard for years at Lee’s Landing, a charming, family-owned marina under the Aurora Bridge on Lake Union.

That marina was where I started learning how to own and skipper a sailboat. Getting into the slip wasn’t exactly easy, requiring a tight turn that brought the stern within kissing distance of the floating home across the fairway from me. I’d wave at my neighbor, who probably never stopped worrying that I would shatter the kitchen window with my dinghy davits.

I loved looking at the cathedral-like arches of the Aurora Bridge soaring above me almost as much as I enjoyed the calland-response horns from boats transiting the nearby Fremont Bridge.

But that bridge and the Ballard locks seemed to lose their charms when they became obstacles to getting out on the

WHEN SWITCHING MARINAS IS MORE SENTIMENTAL THAN ANTICIPATED

wider waters of Puget Sound on weekends and vacations. So we decided to relocate our homeport to salt water.

I remember being gobsmacked by the splendor of Elliott Bay Marina when we first arrived. It was more like a nicely designed park than a marina. The grounds were immaculate, the parking was plentiful, and the views of the Space Needle and downtown Seattle were incredible.

We loved the low-key Thursday night sailboat races and the outdoor party that followed. We enjoyed getting to know the group of boaters who happened to moor near us on J Dock. Over many years, we met their families, watched their kids grow up, made lifelong friendships, celebrated holidays, traded sea stories, and shared tips on our favorite anchorages. We commiserated when the repair guy pronounced their engine beyond saving and celebrated when they hoisted those new sails for the first time.

People and boats came and went, but that sense of community in our little corner of the marina never changed.

I understood Deborah’s reluctance to say goodbye to the marina. Despite that, we decided we should at least explore options close to home.

And so on a Monday morning in January, I pulled together a list of marinas and started making calls, fully aware that most of them would not respond, or if they did, likely offer me condolences and a spot on the waiting list.

But then Eagle Harbor Marina called back. They had a slip available and asked if I’d like to come take a look. I jumped in the car minutes later.

I knew from my research that Eagle Harbor is one of four well-regarded marinas operated locally by the Marsh Andersen Company.

The drive from our house to the marina took exactly eight minutes. I turned down the narrow residential street leading to the marina, then into the ample parking lot. Across the bay, I could see the ferry dock and the old Elwha tied up nearby. Winter rowers were leaning into their synchronized strokes as the chase boat followed close behind. A series of dock carts were tipped up at attention by the gatehouse.

I walked down the ramp to the sturdy, recently built docks alternating between squares of concrete and salmon-friendly grates. As I made my way to the slip, I noticed that the electrical pedestals and the water standpipes were all in excellent condition. And in a sign of the commitment to clean water, each slip had access to a quick and convenient dockside pump-out.

There was no breakwater, but the high hills that rose above the marina to the south would be more than enough to handle any winter storm in the Pacific Northwest. I soon got talking with several resident boat owners, whose only complaint was that the huge dockside flower baskets in summer sometimes left petals on the deck of downwind boats.

I called Deborah and convinced her to come down to have a look as well. And within a few minutes, we decided to take the slip. It happened so fast that at first the magnitude of the decision hardly registered.

Were we really ready to leave behind a place that meant so much to us for so long?

A few days later, we cleared the breakwater at Elliott Bay

Marina for the last time, made the 4-mile crossing of Puget Sound, and nudged Rounder safely into her new slip at Eagle Harbor Marina.

I began to wonder, how many times would we leave this new slip for sailing adventures near and far? How many evenings would we sit in the cockpit watching the ferries come and go? How many times would we fall into conversations with our boat neighbors about the weather, cruising plans, or the latest improvement project?

There was no one to greet us that day. No band played. It felt a little strange tying up to the dock, looking around at the sterns of unfamiliar boats with unfamiliar names.

But it also felt right. It was time for a change. We had a slew of new memories to make. And with time, this marina, too, would transform into a homeport for the boat and for us.

Marty McOmber is a Pacific Northwest sailor, writer, and strategic communications professional. He is currently working on refitting and improving his 1984 Passport 40, Rounder, for continued cruising adventures near and far.

by David Casey

by David Casey

“There was a Small Craft Advisory for Puget Sound and Hood Canal. Local winds are predicted to be 13-16 mph. That is why I selected the leeward side of Fox Island (Hale Passage) for today’s paddle. Does the wind get through to that side? Of course there were sections where the winds were felt but nowhere near what it would have been if we were fully exposed. Patrick (a fellow kayaker) checked out the windy side of the Fox Island Sand Spit and paddled over to the calm side before we departed. There were a couple of sea lions out there checking him out.”

For the ultra-fit 68 year old, kayaking began as something to do on his time off from delivering mail. Since he walked all week on the job, hiking held no allure. But the upper body workout that comes from paddling and the effective use of core muscles in the torso were appealing. Combine that with a therapeutic recovery from his rotator cuff surgery in 2010 and Kaz was all in!

Afew years before Ariel , our Columbia 28 sailboat, became part of our world, my wife and I explored the local lakes of Sonoma County, California on a sit-on-top inflatable kayak called an Advanced Element. When we moved to the Pacific Northwest to be closer to our son, we realized that we had a lot to learn if we were to continue our paddling adventures on the Salish Sea.

Our first venture onto Commencement Bay with our tandem kayak was tenuous, and even a bit unnerving. We resolved to gain a bit more knowledge of the area, hoping to find others with local experience. Fortunately, we soon got to know Kazuhiko Griffin, or “Kaz,” as he is known to his friends and family, who became a good friend and deepened our understanding of the equipment, knowledge, and experience of kayaking in the PNW.

We first met Kaz, a retired postal delivery man, about three years ago while walking around the neighborhood on one of our frequent trips to Tacoma to visit our son. He was out in his front

yard, installing stepping stones across the sidewalk median strip, one of many DIY jobs in which he demonstrates his construction skills and his creativity.

Speaking with both confidence and humility, Kaz gave us a little background on his yard improvement project and his life in Tacoma with wife Sandy, son Kazuhiko, Jr., and daughter Allison. Kaz is a dyed-in-the-wool tinkerer, with evidence of his handiwork seen in the camper top of his 1975 Ford 150 pickup truck, the traveling home of his NC 15foot kayak. However, on that day the truck bed carried varying sizes of lumber for his yard project.

It didn’t take long before the conversation shifted to kayaking, with Kaz energetically recounting some of his recent paddling excursions with an informal club that he had created. He invited Laura and I to join. Kaz sends weekly emails out to all of the folks on the list, informing them of a departure location, route, and weather conditions, along with some of his personal editorials, as seen in the following excerpt from one of Kaz’s recent messages:

The first time that you meet the avid kayaker you feel like you’ve been friends with him for years. His exuberant and effusive demeanor radiate equally to anyone in range. We’ve gotten to know Kaz better on a few kayaking excursions, and even playing a little ping pong in my garage.

Sometimes on a walk, we run into Kaz and Sandy on their weekday bicycle rides along the Point Ruston waterfront. (Now that he’s retired from postal deliveries, he doesn’t mind the lower body workout.) We notice that he’ll strike up a conversation with a stranger as easily as an old friend, and more often than not he’ll take your picture. Kaz never goes anywhere without his camera, taking stills or video of friends or wildlife along the shore. But more than anything, his favorite scene to record is the waters of Puget Sound, and he keeps an extensive and complete documentation of his weekly paddling ventures.

While he doesn’t have a favorite route, Kaz spends most of his time around the Tacoma peninsula, rarely driving far for his launches, which usually take place from Owen Beach, Titlow, and the Ruston Way waterfront.

He has on occasion driven to Shelton and Southworth, but the long drives on highways take time away from relaxing

paddles on the water. Kaz would much rather utilize the beautiful, close, and available bays and inlets than drive to destinations farther away. Additionally, Kaz advises, “familiarity with local waters increases awareness and hence, safety.”

Reviewing his logs since he began his kayaking hobby in 2011, Kaz can accurately report over 700 paddling excursions in those nearly 12 years. He began those adventures in an Equinox 10foot recreational kayak from Costco, using it for nearly 9 years and 549 recorded outings.

His current boat is an NC Kayaks 15, a fiberglass vessel which he serendipitously obtained in December of 2019 from Travis Goldman, the owner of NC Kayaks. Kaz met Travis on the water, of course, as he was returning from his weekly constitutional in the waters of Dalco Passage, just south of Vashon Island.

After a few shared paddles in the next couple of months, Travis offered Kaz a slightly blemished, almost-new sea kayak in exchange for feedback on the protype connection between the hatch and the hull. NC was experimenting with adhesives to make the bond, and Travis figured that the permanent loan to Kaz would take the kayak through its paces out in the open water.

Initially, Kaz was undecided about the V-shaped, curved hull. It was tippy at first, making it easier to capsize than his previous vessel. But the avid paddler concedes that it is faster. And after 158 outings on the streamline kayak, Kaz is not turning back. Although true to his humility, he still believes that he doesn’t deserve to be paddling such a nice kayak.

Safety is of paramount importance

to the de-facto group leader and his fellowship of paddlers. To the point, his favorite book about kayaking is The Sea Kayaker – Deep Trouble, a book that deals almost exclusively with safety.

In addition to the requisite life vest, Kaz carries a waterproof/floating charged VHF Radio (tuned into Channel 16), a whistle, an extra paddle, a first aid kit, a signal mirror, a paddle float (for self-rescue), his cell phone, navigation charts, along with a water bottle, fruit and other snacks, depending on the length of the trip. His camera sits perched atop a small tripod affixed to the foredeck of the kayak.

He’s been accused of carrying everything but the kitchen sink. “But,” says Kaz, “If you don’t take it, you don’t have it.” He recalls going for a paddle with a friend a few years ago. “The only problem,” said Kaz, “was that he forgot his paddle in his car. So there he was, literally ‘up a creek without a paddle.’” Kaz just gave him the spare paddle that he had packed and off they went.

To fend off the cold of Pacific Northwest winters, Kaz layers up with two wetsuits — a 3mm Farmer John and a 3mm shorty below his outer layers. He completes the ensemble with neoprene booties and appropriate head covering, based on the weather report for the wind, temperature, and water conditions.

Kaz — and nearly every other boater that we have met — reminds Laura and I of the three most important things to remember when on the waters of Puget Sound: don’t fall in, don’t fall in, don’t fall in! With water temperatures around 50 degrees, hypothermia sets in, muscles cramp, and drowning can occur within minutes.

With his camera always at the ready, Kaz caught this stunning reflection of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

Should disaster strike, Kaz and his fellow paddlers are prepared. He puts together an annual practice rescue drill for anyone on his email list. The drill starts with a shoreside demonstration of the technique to empty an overturned kayak of water and then climb back into the vessel. Then, with other kayakers in the water just off the shore, the practitioner paddles into the 6-10 foot depths and proceeds with the drill in the water. Returning to the cockpit is probably the most challenging part, although spending a minute or two in the ice cold waters is a close second. Bystanders at last year’s drill, we were impressed with the commitment of these amateur boaters in the informal club, as they volunteered to practice the maneuver.

While it seems like his dedication to kayaking would supplant his approval of any other sea craft, Kaz always encourages Laura and I to participate in boating activities any way that we can. His daily bike rides take him by the marina that berths Ariel, allowing him to check on her and remind us when she is missing our tender loving care.

We have yet to have Kaz and Sandy out on our Columbia 28, although not for lack of trying. Yet for all the wonders of sailing, I’m sure he’ll miss the feel of a paddle across the bow, a watertight spray skirt around his waist, and the splash of the cold waters of Puget Sound on his face.

David Casey is a retired math teacher and semi-professional woodworker and bass player. He plans on using his retirement to build a small sailboat and a kayak, and to explore the waters of southern Puget Sound.

by Lisa Mighetto

by Lisa Mighetto

You know a place like this. It is a secluded, cherished cove seemingly frozen in time. Most boaters have at least one. Mine is located on the east side of the Key Peninsula in south Puget Sound. The site is hardly a secret — it includes a highly-publicized state park — yet it remains an “in between” spot, off the heavily trafficked route between Olympia and Tacoma. My husband Frank and I spent a memorable weekend here with our friend Mike, who camped on shore near Murrelet , our docked sailboat.

Mike drove his truck while Frank and I arrived as we often do — by water. Coast Salish canoes made of cedar have landed in this spot for centuries, bringing Sqauxin, Nisqually, and Puyallup people to harvest salmon, gather shellfish, and trade. Settler colonists came by boat in the days before paved highways allowed cars to probe the nooks and crannies of the South Sound.

“How do I get there?” asked Mike when I invited him to join us on the key-shaped peninsula extending into Carr Inlet to the east and Case Inlet to the west. His question stumped me. Here is what I knew: sail east through Dana Passage, round Devil’s Head, then cruise northward through Balch Passage and around Penrose Point. Of course, such directions were not helpful to a driver. Like many places in the Salish Sea, Mayo Cove is best approached in a boat, chart in hand.

At first, we are disappointed that it is raining. Water flows, trickles, drips, and condenses throughout Mayo Cove, seeping into everything: the structures dotting the shoreline, the wooden docks, our boat, even our foulies. The three of us decide to explore anyway, climbing into the dinghy and leaving Murrelet at the Penrose Point State Park dock. The depth is shallow here, and we poke through the marshy vegetation, admiring the deep greens of the Douglas fir and cedar trees and the yellows and reds of the late September maples. We pass a boathouse that had seen better days. “How old is that?” Frank asks the two historians on board. “Probably built last year,” jokes Mike, noting that water seems to weather a building faster than any other element.

In Mayo Cove, the old and new blend seamlessly, making it easy to imagine the scene before us in previous eras. This is a good place to read the waterscape, and we spot evidence of past logging and farming, including stumps, berms, and remnants of orchards. Turning west, we notice old pilings under a dock at the Lakebay Marina, and stop to investigate a store at the deep end of the pier. Inside, the elderly proprietor serves us coffee and informs us that this once served as a landing for the Mosquito Fleet.

The Mosquito Fleet, a group of steamers and sternwheelers, carried passengers and freight throughout the waterways of Puget Sound during the early twentieth century, stopping at various settlements. While the original pier at Lakebay in Mayo Cove dates from the 1880s, the main building on the wharf was erected in 1928 and housed the Washington Cooperative Egg and Poultry Association. Here the Mosquito Fleet picked up local eggs, which were distributed throughout the region and transported to the East Coast and Europe, where inexpensive protein was highly valued during the Great Depression and World War II. Many residents of the Key Peninsula were members of the co-op. “The eggs were called cackleberries,” Catherine Williams, president of the Key Peninsula Historical Society, explained recently. “They had so much fruit out here… so why not?” (Key Peninsula News, April 1, 2019).

The co-op became an important site for social activities on the peninsula, attracting people to the pier and building. According to Williams, they arrived by boat, as the dirt roads were often muddy. Virginia Seavy, who arrived in Lakebay in 1918, recalled that “there were very few roads — mostly trails in the woods.” By the late 1950s, a network of paved highways and bridges had connected the Key Peninsula with the outside world, and the co-op’s Lakebay station closed. Throughout the late twentieth century, the dock and warehouse operated as a marina. The Pierce County Register of Historic Places listed the site in 2019, recognizing its significance in the development of

the South Sound.

Across Mayo Cove just a few yards from the marina, the area around Penrose Point became a state park in 1987. Stephen Penrose, president of Whitman College, had owned this site, bringing his six children here every summer during the early twentieth century. The Penroses typically arrived on the steamer Tyrus to reach their family camp. Thanks to the state park, kids today continue to play on the shoreline and explore the forest trails winding along the water.

The combination of marina and park makes Mayo Cove an ideal destination for cruisers, offering early waterfront charm in a rural setting, as well as boating amenities. Penrose Park State Park provides docks on the Mayo Cove side, while buoys lure boaters to the Carr Inlet side. So appealing is the location that the Salish 100 small boat cruise stops here on its annual voyage from Olympia to Port Townsend. It is a perfect meeting spot for boaters and those arriving by land, which is what drew Frank, me, and our friend Mike here.

The last stop on our dinghy ride is Von Geldern Cove (also called “Joe’s Bay”), just around the bluff on the northwest side of Mayo Cove. We putter toward the waterfront community of Home, armed with our well-worn, rain-soaked copy of Bailey and Nyberg’s Gunkholing in the South Sound, which informs us that this was once a “haven for free thinkers,” including vegetarians and nudists. As we glide along the forested shoreline, I read aloud to Frank and Mike, recounting how this quiet community made a splash in the region’s history.

Home was one of several utopian communities that emerged in western Washington during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1898, a group of settlers formed the Mutual Home Association, which intended to bring together individuals who valued “maximum liberty” without central organization or government. Local newspapers with evocative titles like New Era and Discontent: Mother of Progress, examined anarchist ideals and reported on the progress of Home, hoping to attract like-minded people.

Jay Fox, a Chicago anarchist and editor, arrived in Home in 1910 and began publishing The Agitator. “Home is a community of free spirits,” he explained in an issue in 1911. Its residents “came out into the woods to escape the polluted

atmosphere of… conventional society.” The Agitator was filled with passionate and colorful rhetoric. Fox described President Theodore Roosevelt, for instance, as a “blatherskite,” “jabbering jawsmith,” and “inflated windbag.”

By 1910, Home had reached a population of 213, with nearly 70 residences. That year, Lucy Robins Lang and her husband Bob arrived in Joe’s Bay on a steamer, hoping to stoke their interest in anarchism and put down roots. The couple had lived in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, demonstrating the connections of Home to the larger world. “We felt at once the fine atmosphere of freedom,” she wrote. “When we looked out… at the snow-covered peaks of Mount Rainier, glistening like a tiara of diamonds, we were sure that we should want to live here for the rest of or lives” (Lucy Robins Lang, Tomorrow is Beautiful, 1948).

Yet Lucy and Bob soon noticed “signs of strain at Home Colony.” External threats included national concern about the 1910 bombing of the Los Angeles Times building by labor activists, which cast suspicion on several Home residents. Around the same time, an internal rift between the “nudes” (those who wished to bathe naked in the waters of Joe’s Bay) and the “prudes” (who watched the unclothed with indignation and horror) emerged. Fox’s editorial on the controversy, which began “Clothing was made to protect the body, not to hide it,” got him arrested. He left Washington soon after, as did the Langs. In the end, the Home Colony “proved too much of a disillusionment” for the couple. In 1919 the Home Association dissolved, and the anarchist community broke apart (Lucy Robins Lang, Tomorrow is Beautiful, 1948).

Frank points our dinghy toward Carr Inlet, heading back toward Mayo Cove. The clouds have lifted and Mt. Rainier towers above the water. This is the scene that had enchanted Lucy Robins Lang, fueling her utopian dreams. That night, we build a campfire on shore and toast the early seafarers of Mayo Cove and the free spirits of Home.

Recent efforts to bring Lakebay Marina back to its former glory will ensure that this historical site continues to charm boaters and inspire excursions like mine. The Recreational Boating Association of Washington (RBAW), Washington State Parks, and Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR) have joined forces to preserve the pier, building, boat ramp, and tidelands for public recreational access. The marina has been purchased and the restoration project, which will likely take 3 to 4 years, has begun. While the site’s components have deteriorated over the years, the marina retains much of the character that has made it a beloved landmark for boaters and locals.

Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz, who oversees the DNR, praised these efforts. “I love this facility and the value it has for recreational boaters in the South Sound,” she commented recently, adding that “the history of this facility is… critical to hold onto” (Key Peninsula News, January 1, 2022). Andrea Pierantozzi, vice president of the RBAW, agrees. “We’re creating a South Sound boating destination that keeps the look and feel of the past,” she explained. “The goal is to convert this gem into a marine park” with boating opportunities for generations to come (personal communication with author).

Bob Wise, president of the RBAW, compares Lakebay Marina to Sucia Island, which has become a favorite place for boaters in the San Juans. In 1960, the parent organization of the RBAW purchased and donated Sucia to the state, to be managed for public use. The hope is that the waters around Mayo Cove, enhanced by the restored marina and adjacent state park, will fill a similar role as a key destination in the South Sound.

Lisa Mighetto is a sailor and historian living in Seattle. She is grateful to the Key Peninsula Historical Society for images, documents, and stories.

by Mac Fraley

by Mac Fraley

The lightning started at 1 a.m. on night four of our 600-mile offshore passage from Craig, Alaska, to Neah Bay, Washington. We were 40 miles west of Vancouver Island and our 50 foot aluminum mast was providing the highest point within hundreds of square miles. As lightning provided the only light in an otherwise pitch black environment, my wife, Jenny, and I, sat huddled underneath the dodger, questioning every decision made that led us to that moment. Below deck, our dog, Disco, was undoubtedly questioning her loyalty to us as we slowly made our way towards shore, waiting to be struck by lightning and swallowed up by the cold, dark sea.

How did we find ourselves in this situation? In late June 2021, we embarked on a path less traveled to return to Washington from a season cruising Southeast Alaska aboard our 1980 Alberg 37, Maya. As many Pacific Northwest boaters know, British Columbia’s section of the Inside Passage offers an excellent route when transiting to and from Alaska. That path provides shelter from the mighty Pacific Ocean and many safe anchorages in which to rest along the way, not to mention breathtaking scenery and wildlife.

The Inside Passage was the route we selected for our journey north from Anacortes, Washington (see “Cruising in Closed Waters” 48° North, January 2022). At the time of our departure in the early spring of 2021, the border between the U.S. and Canada was shut down due to Covid-19. Fortunately for us, the Canadian Border Patrol allowed us to pass through their waters under the stipulation that we make no unnecessary stops and that we not step foot on land except for fuel and water. No problem. We complied and 18 days later (5 days of weather delay) we arrived in Ketchikan, Alaska ready to spend the season cruising Southeast Alaska.

The idea to take the offshore route back arose even before we arrived in Alaska. Instead of spending two weeks transiting the myriad of fjords, motoring for long stretches, and endlessly scanning the water for logs and debris, we figured, “Why not do a straight shot home?” That would afford us an extra week to enjoy Southeast Alaska. We had spent so much energy to get up there, we might as well stay as long as possible.

The offshore route was roughly 600 miles, which we estimated would take us 6 days. As you’d expect, we had lots of questions: Can we handle a passage

like that? Probably. Did we have any overnight sailing experience? No. Did we have any offshore experience? Well, sort of… Our circumnavigation of Vancouver Island a few years back gave us about 200 miles of the open ocean experience, although it was never at night and we carefully picked our travel days. At least we could call ourselves accomplished sailors though, right? Not exactly. We had spent the last few summers cruising, but we never considered ourselves diehard sailors. We often opted to use our boat’s 30hp diesel if conditions weren’t ideal. We had flown our spinnaker a handful of times, but we hadn’t gotten around to experimenting with the pole.

Even though we were a little green for a trip of this magnitude, there were positives. Maya is a great boat and, while she is what some would consider vintage, is well constructed and designed for offshore use. We also know her very well. We’d been living aboard Maya for several years, managing all the maintenance ourselves — electrical, mechanical, rigging, and so much more. Maya was in good shape and she was ready to be offshore.

Another incentive was that we already had plans to sail Maya to Mexico in just a few months — a journey which, of

course, would take us offshore. Why not just jump into this whole offshore thing a little early?

All of these questions played in our minds the entire time we cruised Southeast Alaska, and we waffled about the ideal return trip route. Ultimately, the desire to spend more time in Alaska won and we decided to go offshore on our way home to Washington.

So, after several months of wonderful cruising, we positioned ourselves in Craig, which would serve as our launch point for the southbound voyage. Tied to the transient dock of North Cove Harbor Marina, we stowed all unnecessary items from the deck, including the outboard engine, fenders, and grill, which all fit in the V-berth. We assembled a ditch bag, ran jacklines from bow to stern, and put up the lee cloth to make our seagoing berth in the salon. We had been in contact with a weather router and it looked like we had a decent weather window. The night before launch, we put on antiseasickness scopolamine patches in preparation for the ocean swell, although the medicine did nothing to calm our nerves. This was it. We were ready.

At 6 a.m. on the morning of June 26, we untied the lines and shoved off the dock, slowly motoring away from Craig in thick

fog. Passing through Ursua Channel and into Bucareli Bay, the fog began to lift and the offshore breeze started to fill in. It was here we got our first taste of Pacific swell. With northwest winds around 15 knots, we hoisted the sails and began cruising south.

Day one was sunny and the sailing was brisk. With good wind off our starboard quarter and the swell pushing us along, we were steadily making miles toward our destination. To port, we got our last view of Alaska as we passed by Forrester Island, which was draped in a dramatic layer of cloudy fog. Farewell, Alaska, you’ve been wonderful.

On that first night, we entered the outer reaches of Dixon Entrance, the wind picked up, and the sea state became much more pronounced. We reefed once; then put in a second. Finally, with winds consistently at 30 knots, we put a third reef in the mainsail. And there we sat in the cockpit, wet and freezing cold, rolling back and forth in the swell in the absolute middle of nowhere. I would love to say we confidently and bravely rode out that night, but most of my thoughts were of the “what the hell am I doing out here?” variety.

As dawn approached, the winds decreased, the sky lightened and we

were treated with a sunrise over the mountains of Haida Gwaii. We had put Dixon Entrance behind us and had survived our first night passage! It was one small step for this passage, one giant leap for our cruising careers. Now, we only had four more nights to go.

The next two days saw us making good progress south. The winds calmed down considerably, forcing us to rely on the engine, however the seastate never seemed to relent. Thankfully, the weather was mostly clear — the sunrises over the mountains and sunsets sinking over the endless Pacific were stunning. One pleasant surprise was the amount of daylight we had. Since it was late June at

northern latitudes, we only had several hours of complete darkness before the sky would lighten as dawn approached.

As day four arrived, the weather changed. We were about 50 miles northwest of Vancouver Island’s Cape Scott when the clouds rolled in. During the course of this passage, our only means of communication with the outside world was through a Garmin InReach device which allowed for basic text messages. We had been in close contact with our weather router as well as another sailor friend who had been keeping a close eye on the weather for us. Almost simultaneously, we received texts from both alerting us to a fast

approaching storm front. The forecast was calling for southeast winds, rain, and possibly lightning.

Equipped with this information, we reefed our sails and continued on our course waiting for the storm to hit. Jenny woke me up around 1 a.m. to let me know that the lightning was here. Lots of it. Poking my head out of the companionway, a bolt of lightning streaked across the sky followed by a thunderous boom. The storm was real and, just as forecast, it had arrived. Quickly donning my foul weather gear, both Jenny and I huddled under the dodger as the rain came down in sheets and the wind howled — all the while, the lightning and thunder blasted on.

We elected to turn east and head directly to shore. We could deal with the wind, rain, and sea state, but the lightning… we were helpless against that. I am not an expert about lightning, but I am fully aware that tall metal objects attract lightning. With our aluminum mast 50 feet in the air, and the tallest thing in at least a 40 mile radius, we felt exposed and worried. We motored Maya toward shore, where we could at least be surrounded by land and trees taller than us. There was one small problem with our plan, though. We had not checked into Canadian customs and therefore we were not allowed to be there. However, when faced with the proposition of being struck by lightning in the middle of the ocean, and bureaucratic customs issues, the latter was by far more appealing.

As luck would have it, about 10 miles off Vancouver Island the lightning dissipated and the sky lightened. The storm had passed. Both Jenny and I had been up all night and were completely exhausted. Nothing sounded better than dropping the hook and resting in a safe anchorage, but with the storm now behind us, the thought of illegally entering Canada was a much bigger deal.

Begrudgingly, we adjusted our course to the south and continued on. The storm left an unpleasant and jumbled sea state, and essentially no wind. Still exhausted, we motored, happy to accept rough seas in place of lightning.

Day five quickly turned into night five and then day six. We entered the Strait of Juan de Fuca, carefully timing our crossing to avoid the steady stream

of tankers and big ships transiting in and out. That afternoon, we pulled into Neah Bay, Washington and dropped the anchor. We had done it. Our first offshore passage was in the books and we were back in Washington.

Having accomplished our goal, we look back now with some lessons learned from the experience. First and foremost, the scariest and most uncomfortable part of the whole trip occurred before we even left the dock in Craig. The weeks leading up to our launch day were filled with anxiety and doubt about our decision to go offshore. While our guts told us it was the right move, our minds would not let us rest, brewing up all sorts of terrifying situations to push us back down the safe and standard inside route. Almost all of those thoughts vanished once we were on our way — actually doing it was far easier than dwelling on the scariest wonderings about the unknown.

Secondly, reaching out to fellow sailors in the community provided helpful insight about what we could expect out there, and was instrumental in our decision to go offshore. We got into contact with several people (including 48° North Editor, Andy Cross), and they each had positive and encouraging words for us. Just knowing that others had completed a similar route was extremely comforting and made everything feel less daunting.

This passage was a major milestone for me and Jenny. We had gotten into cruising only a few years prior and, from the very start, it has been an educational journey that has led to immense growth. I can recall losing sleep for weeks prior to backing out of our slip for the first time, terrified of hitting another boat or making a mistake. In hindsight, I have to laugh about how nervous I was to simply back out of a marina slip, but the terror was real. We eventually did back out of that slip, thus taking our first step on a much bigger adventure. Over the years, cruising has continued to present these situations, often forcing us to second guess our skills and abilities when facing a new challenge. And yet in practice, every time we have pushed past those fears, we’ve been rewarded with rich experiences and further developed our skills, allowing us to tackle bigger and

more challenging goals. We are still not the best sailors, we still get nervous, and cruising still challenges us. Through those moments of struggle, however, I can wholeheartedly say that it’s all been worth it. Now, we very much look forward to the next horizon… hopefully free of lightning.

Mac, Jenny, and Disco have continued to cruise aboard Maya, most recently spending several winters cruising Pacific Mexico. You can find videos, photos, and lots more about their travels at www.cruisingmaya.com and www.youtube.com/c/cruisingmaya.

by Andy Cross

by Andy Cross

Like many sailors, I love sailing fast. I love the interaction of wind pressing on the rig, flowing through the sails, and water rushing by the rail. Sending it downwind with a spinnaker up in a big breeze always brings me back for more. Racing on the ocean or around the buoys, getting every last bit of speed out of the boat as possible, is positively thrilling to me. Yet over my years cruising the Pacific Northwest, I came to truly appreciate the times when I needed to brush the hellbent racer in me aside and say, “You don’t need to sail fast to get somewhere special.”

So it was while ghosting over the top of North Broughton Island on a gentle following zephyr and a flood tide. Not far from our next anchorage in Greenway Sound, only the rustle of water trickling from Yahtzee’s stern could be heard. Shrouded in veils of misty fog, mountain peaks slid by and I watched as

our boatspeed leisurely climbed above 2 knots. Perfectly slow. As expected, a northerly breeze soon filled in and when we turned south into the sound we were welcomed by a pod of Pacific white-sided dolphins playing in our bow waves. Having our choice of spots to drop the hook with no other boats in sight, I felt like we’d found an idyllic place to laze away a few days before moving on. Indeed, we had.

Located in the northern section of the Broughton Archipelago — roughly 35 miles from Port Hardy — Greenway Sound is easily accessible from nearby Sullivan Bay Marina. A 6-milelong channel between Broughton and North Broughton islands, Greenway runs east-west for the first 3 miles before making a turn south for the last 3. At its elbow is the eastern terminus

“Hello, bears!” Porter called out in his biggest voice. “We’re here!” We never saw any bears.

of Carter Passage, which completes the cut that splits the land masses into two separate islands. Entering the sound, you can easily see why the word “green” was applied when naming this body of water. Much like the rest of the area, vibrant green rain forests flow from the mountain and hilltops down to the sea. And even though a fair bit of past logging activity is evident as you travel up and down the sound, its effects don’t diminish the overall beauty of the anchorages within.

Our first stop on this late June afternoon was at the eastern end of Carter Passage, just inside the mouth of Broughton Point. We tucked into a one-boat cove behind a tiny islet with suitable depths and swing room, dropped the hook and settled in. It was one of those out of the way places that was almost too good to be true.

Eager to explore the adjacent shoreline, we quickly dropped the kayak in the water and made for shore to poke around tide pools and stretch our legs in the forest. Under the canopy of tall cedar and fir trees, the mossy forest floor was the perfect playground for our sons, Porter and Magnus, to climb, jump, and balance on logs. Easily hike-able, which isn’t always the case in the Broughtons, we meandered up a hill and came across several piles of bear scat. It didn’t look fresh, but we did our best to make noise to let any nearby bruins know that we were hanging out near their home. “Hello, bears!” Porter called out in his biggest voice. “We’re here!” We never saw any bears.

Back aboard Yahtzee, Porter and Jill donned wetsuits and bravely swam in the sound’s not-so-warm waters as I fiddled with fishing gear. That evening, while enjoying dinner in the cockpit, the clouds parted just enough to reveal spots of blue sky and for the sun to make a brief appearance, giving us a shred of hope that it would make a glorious return the following day.

Alas, it was not to be. We awoke the next morning to the pitterpatter of rain dancing on deck, not the abundant sunshine that we were craving. Oh well, we’d have to wait a bit longer.

While planning our route through the Broughtons over the past week, Jill was fairly adamant that we visit Greenway Sound before leaving the area; partly because of a hike we could take on Broughton Island. We’re not big on setting hard and fast plans while cruising, but she isn’t one to steer us wrong either, so we brushed off the rain and motored eastward through the sound over glassy water to a large bay that dips south into Broughton Island on the east side of Greenway Point.

Many years ago there was a floating post office, store, and landing for steamships in the bay and at one point a small marina was operated here by a couple. Few remnants of this past activity remain, and a search on Google Maps shows it as Greenway Sound Recreation Site. What we happened upon was a very small float put in by the BC Forest Service that grants users access to two maintained hiking trails: one to Broughton and Silver King lakes, and the other to a lookout point over Broughton Lake.