Marinco Shore Power systems are trusted by serious sailors for one reason: they work. Reliable connections, weatherproof hardware, and proven durability— designed for years of safe, uninterrupted charging at the dock.

When you’re offshore, everything depends on preparation. But at the dock, power should be one less thing to think about. Marinco makes rugged shore power inlets, cords, and accessories built for harsh marine environments— tested by thousands of miles, from Puget Sound to San Diego Bay.

Whether you’re plugged in for the night or prepping for the next leg, Marinco delivers dockside reliability that holds.

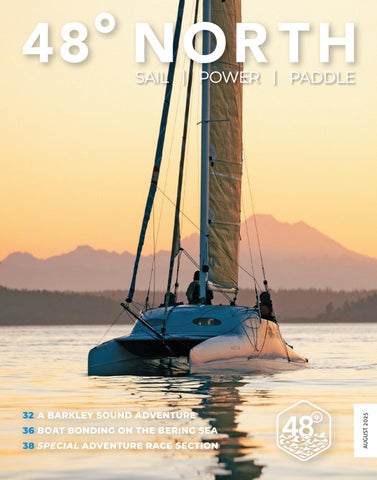

32 A Barkley Sound Adventure

New cruisers test their boat and skills with a voyage out the Strait. By Medeea

Popescu

36 Boat Bonding on the Bering Sea

Storm sailing on an Alaskan crossing for the One Ocean crew.

By Jennifer Dalton

SPECIAL Adventure Race Section

With nearly 200 participating boats between them, SEVENTY48 and WA360 offered summer highlights for racers and fans alike.

38 Rowing a Sailboat to Port Townsend

Steak Knives to a Gunfight's historically questionable SEVENTY48.

40 Puget Sound Navigation Company's WA360 Win Savvy sailors rediscover home waters and set a course record.

43 The Adventure We Chose

Team Salish Seasters share stories from their WA360 odyssey.

20 Close to the Water: No Grease, No Glory

Projects to puzzle the neighbors, from trailer hubs to new oars.

By Bruce Bateau

22 Hikes for Boaters: The Broughtons

By

Michael Boyd

Though rewarding, hiking options here are fairly spread out.

24 Necessary or Nice: Bow Thrusters

Is this system cheating, or just smart?

By Julie and Gio Cappelli

28 A Northwest Sailor Navigates the Past

Jolly Roger MacGregor and the pirates of the South Coast.

By Lisa Mighetto

46 Juan-Design Fun at Whidbey Summer Classic

Penn Cove racing at its finest for the San Juan 24s and others.

Sitting among dozens of J/70 racers who had sailed the 26 boats that made up that evening’s fleet, I drank in the fading summer twilight on the lakeside patio. The postrace din held everything from casual conversation to active education, and my attention was soon drawn back to the middle ground of a good-natured deliberation between some longtime sailing pals. I was equally envious of their enthusiasm as I was relieved not to be party to their voyage through contention to consensus. The content of their discussion wasn’t critically important to me that night, but I am intimately familiar with this kind of inquisitive discourse and its unique brand of import—honing the slightest details of set-up, trim, and boat handling; chasing that thousandth-of-a-knot; aching for reliable answers in an environment as inherently complex and dynamic as sailing. Such challenge and commitment, partnership and vulnerability, community and doubt and positive reinforcement—it all makes up the crucible of one-design racing. It’s fun, too, I swear.

Hardly an original idea, but I’ve always thought one-design racing is the best and most fun version of the game, and for me the sportboat sailed by a crew of three to five people is at the mountaintop. The J/70 nestles neatly into that category.

Though one-design has always had my heart, I’ve spent more time in the last decade racing under various handicap scoring systems, learning and experiencing more alongside incredible sailors than I would have thought possible—I count myself extremely lucky. But in part because of what I didn’t find in these recent years, it’s even easier for me to appreciate how valuable it is to sail the exact same boat as your fellow racers. It’s an open invitation to ask, to learn, and to lean into the collaborative camaraderie of competition. It’s possible to find a similar community when racing under a handicap, but in reality it’s just harder. If you’re sailing different boats, the sharing of knowledge often bypasses the directly actionable on its way to the theoretical. That’s part of what makes one-design racing such an accessible learning environment—mastering the processes that make the boat fast paves the way to understanding the principles that animate those mechanics. In essence, you get more enjoyment in the near term while still giving oxygen to the slow burn of deeper knowledge and nuance.

The J/70s have it all right now, boasting big numbers and the panache of some of the region’s most successful sailors. Crucially, though, there are a lot of folks heading out to the same start line on Wednesday nights who are not as accomplished or experienced. Unique to the local J/70s is the role of fleet coach, Ron Rosenberg, whose leadership is not only helping the fleet get up to speed more quickly, but is also fostering a culture of investment in your competitors—like members of the same team. What Ron preaches is special and helps catalyze good practices, but I personally know similar wholesome community vibes are part of many one-design fleets.

None of that positivity precludes the effort, rigor, and desire within a given onedesign team, which brings us back to the table with my pals and their debate about boat handling and trim. I know this may not be everybody’s definition of a perfect evening—sailboat racing’s appeal has its limitations, and other approaches are growing (see the Adventure Racing section, page 38)—but to me it's truly special.

Stepping back into the one-design environment illuminated all the meaning and connection, the knowledge and reward that is available to anyone who joins a fleet like the PNW J/70s. It made me nostalgic for my own history with such communities and the fellowship with those debate-partner friends alongside whom I happily give my free time to solving sailing puzzles, getting faster, and having a legit blast along the way.

I'll see you on the water,

Joe Cline Managing Editor,

Volume XLV, Number 1, August 2025 (206) 789-7350

info@48north.com | www.48north.com

Publisher Northwest Maritime

Managing Editor Joe Cline joe@48north.com

Editor Andy Cross andy@48north.com

Designer Rainier Powers rainier@48north.com

Advertising Sales Ryan Carson ryan@48north.com

Classifieds classads48@48north.com

48° North is published as a project of Northwest Maritime in Port Townsend, WA – a 501(c)3 non-profit organization whose mission is to engage and educate people of all generations in traditional and contemporary maritime life, in a spirit of adventure and discovery.

Northwest Maritime Center: 431 Water St, Port Townsend, WA 98368 (360) 385-3628

48° North encourages letters, photographs, manuscripts, burgees, and bribes. Emailed manuscripts and high quality digital images are best!

We are not responsible for unsolicited materials. Articles express the author’s thoughts and may not reflect the opinions of the magazine. Reprinting in whole or part is expressly forbidden except by permission from the editor.

SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS FOR 2025

$39/Year For The Magazine

$100/Year For Premium (perks!) www.48north.com/subscribe for details.

Prices vary for international or first class. 48º

Proud members:

48° North has been published by the nonprofit Northwest Maritime since 2018. We are continually amazed and inspired by the important work of our colleagues and organization, and dedicate this page to sharing more about these activities with you.

Maritime High School (MHS), a regional choice public high school in Des Moines, WA, marked a historic milestone in June with the graduation of its inaugural Class of 2025. The ceremony celebrated 31 pioneering students who have become the first graduates of this innovative maritime-focused educational institution.

A collaborative project of Highline Public Schools, Northwest Maritime, Port of Seattle, and the Duwamish River Community Coalition, MHS’s educational approach combines traditional academics with hands-on maritime training, including real-world industry exposure and experiential learning—spanning three mastery-based learning pathways: Marine Science, Vessel Operations, and Marine Construction.

“The first graduating class of Maritime High School shows that the future of maritime for our region is one that will be accessible and inclusive to all of our local communities,” said Port of Seattle Commissioner Ryan Calkins.

Of the 31 graduates that made up the Class of 2025, 25 students completed all four years at Maritime High School, demonstrating the school’s ability to retain and engage students in its specialized maritime curriculum while achieving a remarkable 100% graduation rate.

Among this year’s graduates was Kaylie G., who discovered her passion for vessel operations during her time at MHS. “I plan to attend Seattle Maritime Academy to pursue a career in the maritime industry as an engineer,” she shared. This summer, Kaylie will begin an internship with Washington State Ferries.

Members of the Class of 2025 are set to embark on exciting and diverse paths this fall, with some choosing to enter the workforce directly (equipped with knowledge and credentials to earn $60,000$80,000 per year) and others pursuing higher education at technical colleges and universities—many will continue maritime studies.

MHS’s success comes at a crucial time for the maritime industry, which faces significant workforce shortages—expert estimations suggest the need for 150,000 additional mariners this year.

The Class of 2025 is more than a group of students, it's a symbol of what’s possible when education meets opportunity.

Registration is now open for the 2025-26 school year.

» www.maritime.highlineschools.org

From inspiring presentations to captivating films, from hands-on demonstrations to daily live music—the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival is only a month away.

• Kiana Weltzien Brings Women & the Wind: Join Kiana at this year’s Festival for special presentations, a panel on Wharram catamarans, and a screening of the award-winning documentary Women & the Wind.

• Shipwrights: Keepers of the Fleet: Shipwrights from around the world bring the art of boat building to life.

• 76 Days Adrift Documentary: Don’t miss the screening of 76 Days Adrift, an award-winning film based on Steven Callahan’s bestselling book "Adrift: Seventy-Six Days Lost at Sea."

• Ropemakers Return to Festival: The Hardanger Ropemakers from Norway, masters of the ancient art of traditional rope-making, share their expertise all weekend long.

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 4

All Day: Festival Boats arriving 5 p.m. Lifetime Achievement Awards

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 5

9 a.m. The 2025 Festival officially opens! 4:30 p.m. Keepers of the Fleet: International Shipwrights Panel 7 p.m. 76 Days Adrift Screening

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 6

3 p.m. Haida Sails Resurgence Project 6:30 p.m. Women & the Wind Screening, Q&A with Kiana Weltzien

SUNDAY SEPTEMBER 7

11 a.m. Sea Birds with Peter Harrison 3 p.m. Traditional Sail By

A Gold Duck for the Henderson Family’s Vintage Dragon Hey Joe,

Model Shown Beta 38

Beta Marine West (Distributor) 400 Harbor Dr, Sausalito, CA 94965 415-332-3507

Pacific Northwest Dealer Network

Emerald Marine Anacortes, WA • 360-293-4161 www.emeraldmarine.com

Oregon Marine Industries Portland, OR • 503-702-0123 info@betamarineoregon.com

Access Marine Seattle, WA • 206-819-2439 info@betamarineengines.com www.betamarineengines.com

Sea Marine Port Townsend, WA • 360-385-4000

info@betamarinepnw.com www.betamarinepnw.com

Deer Harbor Boatworks Deer Harbor, WA • 844-792-2382 customersupport@betamarinenw.com www.betamarinenw.com

Auxiliary Engine 6701 Seaview Ave NW, Seattle WA 98117 206-789-8496 auxiliaryeng@gmail.com

Allan Johnson

Check out this photo taken by the skipper Kris Henderson of his brother Erik on their vintage Dragon US - 10, Sommerfugl. I’ve been sailing with (and against) these guys since the 1980s and this boat has been in their family since the 1970s. She has been sunk, dismasted, and lovingly restored by these shipwrights. Jon “Noj” Henderson built the sails at Doyle New Zealand. Tom Hellmann joined them to help get a gold duck that night.

Response to Lizzy Grim’s Van Isle 360 Report from the July Issue

From Tom Davis on Facebook: Nice write-up, Lizzy! The Van Isle is an epic sailing event, and I have had the privilege of participating in it several times. I thoroughly enjoyed following this year’s event from my armchair... and it brought back great memories.

A Beautiful Ballard Cup Sail!

Hi Joe,

I recently joined a friend’s crew for evening races here in Ballard. I’m a hobbyist photographer, and being on the water at sunset surrounded by so many gorgeous boats and smiling friends, you really can’t ask for a better photo opportunity.

Cheers,

Matt Johnson

T EM B E R

T EM B E R

& 7, 2 02 5

& 7, 2 02 5

©LucSchoonjans 5,6, & 7, 2 02 5

©LucSchoonjans

Women & the Wind Special presentations, a Wharram catamaran panel, and a screening of the award-winning documentary Women & the Wind.

Special presentations, a Wharram catamaran panel, and Women & the Wind.

Women & the Wind Special presentations, a Wharram catamaran panel, and a screening of the award-winning documentary Women & the Wind.

Shipwrights: Keepers of the Fleet Shipwrights from around the world gather to showcase craftsmanship and celebrate the art of boatbuilding.

Shipwrights from around the world gather

Shipwrights: Keepers of the Fleet Shipwrights from around the world gather to showcase craftsmanship and celebrate the art of boatbuilding.

76 Days Adrift Documentary Screening of the award-winning film based on a gripping true story of survival and resilience.

Ropemakers Return to Festival Norway’s Hardanger Ropemakers will demo traditional rope-making techniques all weekend long.

76 Days Adrift Documentary Screening of the award-winning film based on a gripping true story of survival and resilience.

Ropemakers Return to Festival Norway’s Hardanger Ropemakers will demo traditional rope-making techniques all weekend long.

Screening of the award-winning film based Norway’s Hardanger Ropemakers will

of Stunning Wooden Boats | Live Music All Day | Craft Beer & Local Food |

and schedule available at Woodenboat.org

|

Tickets and schedule available at Woodenboat.org

|

• Boats

• Kayaks & SUPs

• Trailers

• Gear

• Boat

• Bilge

• Motor

• Live-wells

Fully before moving to a new lake, river, or waterway.

Invasive species such as quagga and zebra mussels threaten our outdoor recreation, economy, infrastructure, environment, and public health. Help stop the spread by cleaning, draining, and drying your gear, equipment, and watercraft every time you leave the water.

Learn more: dfw.wa.gov/ clean-drain-dry

Request this information in an alternative format or language at wdfw.wa.gov/accessibility/requestsaccommodation, 833-885-1012, TTY (711), or CivilRightsTeam@dfw.wa.gov.

If you find a suspected European green crab or their shell, photograph it, note the location, and report it.

wdfw.wa.gov/greencrab

The European green crab is a damaging invasive species that poses a threat to native shellfish and habitat for salmon and many other species. They are not always green and may be orange, red or yellow. These shore crabs are found in less than 25 feet of water often in estuaries, mudflats, and intertidal zones. They are not likely to be caught in deeper water, but may be encountered by beach anglers, waders, clam and oyster harvesters, or those crabbing off docks or piers in shallow areas. As a Prohibited species, it is illegal to possess or transport live European green crabs in Washington. Shellfish growers and private tidelands owners in areas with European green crabs should contact WDFW for management support or permits. Please email at ais@dfw.wa.gov.

Request this information in an alternative format or language at wdfw.wa.gov/accessibility/requests-accommodation, 833-885-1012, TTY (711), or CivilRightsTeam@dfw.wa.gov.

The Fall Boats Afloat Show will be coming to Seattle’s South Lake Union from Thursday, September 11 to Sunday, September 14, spotlighting a world-class fleet of sailing yachts and high performance craft. New for 2025, the show has expanded and now has in-water boats on display at H.C. Henry Piers, directly accessible from inside the main show.

This must-attend show offers a wide variety of boats from the U.S. and Canada in one exquisite location—powerboats, sailboats, day boats, long range cruising yachts—and much more. Show-goers can learn about the latest boating lifestyle and technology trends, and also enjoy a full line-up of curated events while charting their next adventure: live music, delicious beverages, and fun activities for the whole family. A boating tradition since 1978, it is the largest floating boat show in the Pacific Northwest and is presented by the Northwest Yacht Brokers Association (NYBA).

Early Bird tickets are available for purchase on or before August 28, which provide the best discounted prices on Thursday Opening Day, Adult Single Day, and Adult Multi-Day tickets. Teen tickets are not subject to early bird discounts. Children 12 and under are always free!

Standard discounted online ticket prices begin August 29, and are available for purchase through September 14. Skip the lines and get the best prices by purchasing your tickets online.

The Magenta Project has launched the 2×25 global survey, marking the start of the most ambitious equity and inclusion review ever undertaken in sailing and the wider marine industry.

Building on the landmark 2019 Women in Sailing Strategic Review, where 59% of women reported personal discrimination and 80% said gender imbalance was a problem, through this new survey Magenta Project intends to expand the lens to include more research into race, ableism, and age.

Backed by 11 th Hour Racing and supported by World Sailing, 2x25 is led by The Magenta Project, a global initiative committed to equity and inclusion in sailing, in collaboration with a team of researchers and advisors.

Everyone that is involved in sailing and/or the marine industry, all genders and backgrounds, is invited to complete this survey to help build a more inclusive future for the sport.

The survey runs from July to September 2025, with results to be presented in November 2025. Take the survey here: » themagentaproj ect25. qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_0VPakFDbA84Ahj8

On-site ticket types can be purchased at full price at the Boats Afloat Show entrance, September 11-14.

• Thursday Opening Day Ticket: $24 (price includes one wine, beer, or non-alcoholic drink at the Breakwater Bar; valid Thursday only)

• Single Day Admission: Adults: $24, Teens (13-17): $7, Children 12 and under are Free!

• Multi Day Admission: Adults: $40, Teens (13-17): $12, Children 12 and Under are Free!

• Discounted Military Tickets available on-site only - must show valid, current military ID, tickets valid for ID holder only. $15 - Adult Single Day Military Ticket.

» www.boatsafloat show.com

American Sailing’s Performance Race Week presented by North U will once again be coming to the Seattle Sailing Club to help refine your racing skills. Held from September 15-19, 2025, seasoned coaches aboard J/80s are there to guide participants through practical onwater training and races, shoreside seminars, and insightful video reviews. The intensive five-day clinic sailed out of Shilshole Bay Marina is designed to elevate your competitive sailing skills, with

special attention given to tactical decision-making. The aim is to help sailors improve their skills in every facet of racing—trim, tactics, boat handling, and driving—and return home a better, more versatile racer. North U coaches combine championship racing skills with years of coaching experience. With just four sailors plus a coach aboard each boat, participants will get close personal attention. And to be clear: The coaches will NOT be sailing the boats. Participants and their teams do all the sailing. The format of each day will vary slightly depending on what skills are being taught and, by the end of the week, sailors are likely to have done more starts than in an entire season of racing at their local clubs.

» americansailing.com

The inaugural edition of the New York Yacht Club International Women’s Championship will take place September 12 to 19, 2026, at the New York Yacht

Club Harbour Court in Newport, R.I. The New York Yacht Club recently announced a slate of skippers and teams to contest the inaugural International Women’s Championship next September. Among them is 2023 Rolex Yachtswoman of the Year (and 48° North contributor), Christina Wolfe, leading a team of experienced and talented women from Washington and British Columbia.

Chris Wolfe will be well known to most 48° North readers, if not because of her international acclaim and amazing race results in doublehanded offshore competition here and abroad, then for her articles and interviews in this publication. This newly-formed PNW team includes other accomplished local sailors, including Joy Dahlgren, Jen Morgan Glass, and Maura Dewey. Congratulations to Chris and all of these awesome sailors.

After 25 years of proudly supporting the home boatbuilding community, Duckworks Boat Builders Supply will be closing its warehouse and ceasing operations. This decision has not come easily. Rising costs, increased tariffs, slimmer margins, and increasingly complex shipping logistics have made it unsustainable to continue operating the business at break-even levels. Duckworks is deeply grateful to the customers, designers, and makers who have been part of their journey for the past two and a half decades.

“Duckworks has always been about more than just plans and supplies—it’s been a hub for creativity, craftsmanship, and community,” said Sommer Ueda, VP of Sales & Operations. “We’ve been honored to serve generations of builders around the world.”

While warehouse operations are ending, the Duckworks legacy will continue in a new way. Duckworks founder Chuck Leinweber is working closely with plan designers to establish a new marketplace where customers can continue to access the highquality plans they’ve come to know and love, and more information will be shared as details are finalized.

Gig Harbor Boat Works, Duckworks’ sister company, remains open and committed to building small rowing and sailing craft in Gig Harbor, Washington.

The International Women’s Championship will be an exciting event to follow. We’ll certainly be cheering for this team!

“There is a lot of talent in the Pacific Northwest,” says Wolfe, who has made a name for herself in the doublehanded division of some of the world’s most prestigious ocean races. “The NYYC International Women’s Championship seemed like a great opportunity to pull together an international team for the event. Many of us race against each other in various regattas, but we’ll now have the opportunity to race with each other.”

The regatta will utilize the Club’s fleet of 20 IC37s. The 37-foot keelboat was designed by Mark Mills to a brief developed by the Club. The IC37 is a powerful, sporty platform that rewards cohesive crew work and athleticism. » nyyc.org/2026-womenschamp

The fan favorite Northern Century Race is making a shift in 2025, moving to Labor Day weekend August 29 to September 1. With a reformatted plan for the event this year, the racers reception will be on Friday evening August 29 with live rock music for all featuring Skagit’s own Chill DeVille. Saturday morning will feature a pancake breakfast and then the skippers meeting at 9:30 a.m. The start of the race will be at noon on Saturday.

Racers now have 48 hours to finish (versus 40 hrs in the old format). The Century and the Fifty Cent are still a go, and events and trophies, beer and camaraderie on the lawn will be Monday from 12-3 p.m. This will be a great weekend, and if you’re joining as shore support, Anacortes has a lot of fun things happening Labor Day Weekend. » anacortesyachtclub.com .

Anchors

by Bryan Henry

The first lightship on the Pacific coast was stationed off the mouth of the Columbia River in 1892.

The first lightship to be moored in the open ocean began operation off Sandy Hook, New Jersey, in 1823.

The first American lightship, then called a “light boat,” was stationed off Willoughby Spit, Virginia, in Chesapeake Bay in 1820.

For its first 15 years of existence, the Statue of Liberty was overseen by the United States Lighthouse Board.

The seven spikes in the crown of the Statue of Liberty stand for the seven continents and seven seas.

The French frigate Isere that transported the Statue of Liberty to New York in 1885 fought rough seas that nearly sank the vessel on its journey.

1 Vessel with two hulls

Area between two headlands perhaps

Resting on or touching the bottom

Rotates as a vessel from side to side

Frozen water

They shelter ships from rough seas

Warrant Officer, abbr.

Football position, abbr.

Narrow passageway used to enter a ship

Sudden powerful forward movement

23 Significant historical period

24 Slang word for a sailor

25 One of the San Juan islands

27 Fastened with a heavy pin

30 Edward, for short

Majestic bird with sharp vision

1 Wear on a line or sail caused by constant rubbing

2 Rocky hill

3 River’s end

4 Object location system

5 Area of sea closely bordered by two pieces of land

6 Seabirds

7 The Northwest ____ : sea lane from the Pacific to the Arctic Ocean

11 Extremely long time period

13 Miles away

14 Planned path of a voyage

16 Fairy tale fiend

18 At sea its often salty

19 Horizon where the sun sets

20 Either end of the yard of a square-rigged ship

22 Rope ladder providing access to the top of the mast

25 Vast body of saltwater

26 Havana is a well-known one

28 Suddenly changes direction

29 Depth of a vessel

Handles (used on radios)

NY time, abbr.

The ninth statute enacted by Congress in 1789 was “An Act for the Establishment of Lighthouses, Beacons, and Buoys,” after passage known as the Lighthouses Act of 1789.

Historians have identified about 30 Roman lighthouses from the Black Sea to the Atlantic Ocean that were built before the empire collapsed in the sixth century.

Among ancient sealife was the saber-toothed herring (Enchodus petrosus).

The oldest known vertebrate was the Anatolepis, a jawless fish that lived more than 500 million years ago.

The earliest known four-legged vertebrate, or tetrapod, was the amphibian Ichthyostega, a descendant of fishes that lived around 375 million years ago.

The Japanese giant spider crab is the world’s largest crustacean and the largest living arthropod.

Once the world's rarest organism, the last living Pinta Island tortoise of the Galapagos known as Lonesome George died in 2012 marking the extinction of his species.

Some species of shrimp live for only several days to 120 days; others can live as long as six years.

Some giant clams on the Great Barrier Reef are more than 120 years old.

Having a reliable cooler backpack is a must for cruisers going on provisioning trips or simply heading to shore for a picnic with cold food and beverages. The new TravelR Soft Cooler Backpack is a convenient piece of kit that is big enough to carry food and drinks for the crew and comfortable enough to haul on even the longest beer run. The TravelR features water resistant zippers, ColdR™ Tech XPE insulating foam, and a TPUcoated inner liner that keeps the cold in and the sand out. The LoadR Wide Top makes it easy to stock the cooler up with goodies and keep them secure. The backpack has a 24 liter capacity and fits 24 cans comfortably with ice. Color choices include Coral, Charcoal, and South Pacific Blue.

Price: $149.99 » www.rovrproducts.com

Perfect for beachgoers, surfers, dinghy sailors, small boat adventurers, and cruisers with kids and dogs, the Ocean Rise 2.1 gallon Portable Shower is a logical addition to your gear list. Powered by a manual hand pump for effortless pressurized water flow, there are no batteries needed. You can choose from 10 shower head modes, with 2-6 minutes of water run time depending on the mode. The 4mm insulated neoprene cover keeps water warm in winter or cool in summer, while the black tank prevents algae and bacteria growth for cleaner, longer-lasting water. A tangle-free 6.8 foot hose allows it to be hung overhead and a stable base design prevents tipping.

Price: $135 » www.beachsoul.com

One problem with conventional rope clutches is that there tends to be some amount of slip that occurs when the line is under a heavy load. Spinlock’s new XX range of clutches aims to reduce this issue by holding loads 50% higher than any conventional clutch. Their XX Powerclutches present an ideal solution for genoa and spinnaker halyards on performance yachts in various sizes. Yachts from 35 to 50 feet will choose from the XXA range and for those looking for enhanced performance on small diameter blended covered lines check out the new XXB. Spinlock’s latest jaw technology offers consistent holding of blended covered rope and a smooth controlled release action. The one-piece jaw set is easy to remove and clean and there are access ports for fresh water flushing. The clutches are available in white coated, black anodized, or silver polished alloy to match the deck or rig.

Price: Starting at $625 » www.spinlock.co.uk

by Bruce Bateau

Aneighbor stares up my driveway and his dubious look says it all, “What’s that boat-obsessed guy up to now?”

Most of my neighbors are used to the myriad projects that happen in my driveway or in the parking spaces in front of my house; either that, or they’re annoyed by the frequent comings and goings of my various craft, and the chores that go with them. With a fleet of small boats, there’s almost always something happening around my backyard boatyard, and I like it that way.

“No grease, no glory!” I call, hoisting a yellow rubber-gloved fist in the air. This particular job could have been offloaded to professionals at my local Les Schwab Tire Center for a hundred bucks and a lot less effort. But unlike diagnosing malfunctioning household appliances or climbing a 40-foot ladder to clean the second story gutters (an activity my wife has forbidden middleaged me from doing) this is a project I can successfully complete.

The gloves are covered in a gloss of blue gray marine grease, as if I’ve just

done surgery on a robot. Which in a way, I have. I’ve jacked up Row Bird’s trailer, unbolted the lug nuts on the wheel, disassembled the hub and bearings hidden below, and cleaned them of last year’s grease. Midway through the process of greasing the bearings and inner workings, I’ve made a substantial, but critical mess. For land-based sailors, keeping our trailer hubs adequately lubricated is crucial—if we omit this task, they’ll overheat and we’ll end up stuck on the side of the highway, smelling scorched metal instead of the tang of low tide. An hour later, the hub is reassembled, the wheels are back on, and the boat is ready to head to points north.

Another day, my quarry is those pesky registration letters required on the bow of most small boats. As an avid sketcher, I’m always doodling bubble letters in my notebook, so I decided that I had the skill to paint my own. Now I’m standing on a six-foot step ladder, paintbrush in hand, trying to create elegant white shapes that resemble letters on Luna’s red sheerstrake. Although I’ve penciled

in each letter and neatly added blue masking tape to avoid unwanted smudges, a friend observing from a lawn chair cheekily informs me that my work is “a little too handmade.”

Climbing down for some perspective, I try to imagine the letters without the blue tape, and I have to admit they aren’t quite as crisp as I wanted them to be. For a moment, I start to wonder if perhaps I should have called a printshop and ordered some of the “nice” vinyl letters so common on boats these days. But in addition to the extra expense, I hesitate to slap machine-made lettering on a wooden boat made primarily by hand.

In the end, I decide to let the paint dry and evaluate. An hour later, surveying my work from 20 feet away, the letters are easily readable, yet still imperfect. But they meet the regulations, and they’re mine. Besides, Luna is already the wooden boat version of a Volkswagen bus; funky letters fit the bill. Another personal project is now complete. Next time I’ll do better.

I approached summer’s last project with a mix of trepidation and excitement. Using a kit, I’d built an ultralight dinghy for Luna, but oars weren’t part of the package. And I’m well aware that a good pair is the difference between rowing being a joy or a torment. The last time I tried making oars I had fun, but ended up with items resembling battle axes, rather than well-balanced rowing

The author presses bearings back into the wheel's hub.

devices. Still, I reasoned that oars for a dinghy didn’t require the skills of a master craftsman. After all, dinghies end up being bashed around at the dock and things in them sometimes go missing. So rather than buying a cheap heavy pair at the marine store, or an expensive, beautiful pair I’d worry about, I decided to make them myself using lumberyard cedar.

After digging through nearly 100 two by fours, I found a handful that were mostly knot free. With the help of a friend, we ran them through a planer

and used epoxy to glue them together to make the shafts of the oars. Over many evenings and weekend afternoons, I employed a band saw, a spokeshave, and a series of planes to turn all that wood into a pair of oars that now moves my dinghy along comfortably. Using them, I remember the joy of seeing something attractive and useful emerge from raw materials.

The completion of the dinghy and oars gave me a sense of accomplishment larger than any of my past nautical projects. But I couldn’t find the words to

describe that feeling until I read a post from my friend Alex at the WoodenBoat Forum.

“There are few opportunities in this increasingly virtual and manufactured world to do something truly authentic, and end up with something unique. To do something that is, to me, a perfect fusion of action and contemplation, of doing and being. To undertake a protracted project that engages your intellect, yet allows you to be in the moment, for extended periods.”

Alex got it exactly right. When I take my boat to a shop, or to someone else for repairs, it’s all out of my hands. Maybe my neighbors don’t get it, but whether I’m doing a simple job on my boat or a more complex task, I’m fully engaged in an activity that feels important, helps me learn new things, or makes me relish skills I’ve developed. That’s nearly as good as being out on the water.

Bruce Bateau sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Oregon. His stories and adventures can be found at www.terrapintales.wordpress.com

First Fed enthusiastically supports the events, activities, and initiatives of Northwest Maritime through its ongoing sponsorship of the local 501(c)(3) non-profit. First Fed is here for this community in so many ways, and is honored to help uplift others whose endeavors also contribute to the common good!

First Fed helps more people connect with the sea!

Aby Michael Boyd

h, the Broughtons, one of the dreamiest cruising destinations in the entire region. It is a cruiser’s reward, whether you’ve just challenged often-blustery Johnstone Strait or are ducking in from the bigger water of Queen Charlotte Strait and the Pacific Ocean beyond. This area offers much more than just protection from winds and waves, however—it is a treasure trove of islands and waterways to explore and enjoy.

In this column we are using the Broughtons as shorthand for all the islands, inlets and communities spread out around the south end of Queen Charlotte Strait, not only the specific islands of the Broughton Archipelago. Here, while there are opportunities to get off the boat, including substantial towns on Vancouver Island, real hikes are well spread out. Often, even in marine parks, the only way to get past the beach is to bushwack to nowhere, a strenuous and not very rewarding activity. Still, we have come here enough to have discovered a few favorite opportunities.

The large Vancouver Island town of Port McNeill is our preferred provisioning stop and the private marina is our preferred moorage, mainly because they have long hoses so you can fuel your boat right at your slip. It’s also the closest marina to the laundromat—a real plus since hauling loads of laundry up and down docks is not one of our favorite activities. With a proper supermarket nearby, the essentials of provisioning are taken care of, and if we aren’t walked-out from the chores there are also hikes.

Heading east along the water is a road along a bluff with great views, which after a mile or so leads to a trail near the shore for another mile. This four mile hike has plenty of interest without any appreciable up and down. We’ve done it in both good weather and bad and think it’s gratifying at any time.

But for a lovely hike through the woods from Port McNeill, we have to take a bit of a trip. We catch the BC Ferry to Sointula where we can explore a super nice small town (people offer to give you a ride even if you are just walking along the road) and go for a wilderness hike. Starting at the eastern end of 9th Avenue is the Mateoja Heritage Trail, which goes for several miles through many different terrains, including an area regrowing from a 1923 forest fire, ending at Big Lake. It is easy walking and a very rewarding 4-mile round trip from the trailhead. Of course, you don’t have to come here from Port McNeill by ferry. You can come to Malcolm Island by boat and stay at the Sointula Harbour Marina. The walk to the trailhead is not much longer. We like both options.

Turnbull Cove is a mainland cove at the head of Grappler Sound, across Queen Charlotte Strait from Port McNeill, but you don’t have to expose yourself to open water to get there. Instead, most cruisers get there via a totally sheltered route through the islands of the Broughtons. The cove is a large, landlocked bay with great anchoring everywhere. The hillsides are very steep and show evidence of prior landslides. In fact, a major slide in 2005 ended in the water close to where we had been anchored only a week before. There must have been a substantial tsunami. We prefer anchoring away from steep hillsides now.

This is a marine park and it has a hike. The trailhead is in a small cove on the north side and goes straight up the hill following an old logging road to Huaskin Lake where there is a ramp from shore out to a float; it even has a picnic table. It’s only half a mile but the road is slowly becoming overgrown and the trail gets harder every year. From the float you can only see a small portion of the lake but its arms extend many miles in several directions. It would be fun to kayak the lake, though hauling the kayak up there from the cove, less so. We’ve seen bear tracks on the trail and in 2023 a black bear was walking the rocks along the shoreline near our boat when we got back from our hike. As with most hikes it's important to be bear-aware.

Logging roads are a good way to stretch your legs, if not always the most desirable hikes. Some were recently in active use so they aren’t as pretty, since trees haven’t filled in yet, but that also means they may offer expansive views. The best access is usually at the old log dump, which is often close to some good, or at least adequate, anchorage. Here are some we have used. There are many others we have seen from the water but haven’t visited. New ones come along regularly, of course; an active logging site today may be an interesting hike in some future year.

A black bear turns over rocks near Mischief in Turnbull Cove. Hikers in this area are advised to be bear aware.

Opposite the entrance to Potts Lagoon on the north side of West Cracroft Island is a fairly recent logging road. We were there just after it was abandoned and there were lots of signs of bear activity.

In the Warren Islands at the entrance to Call Inlet is a logging area that closed down just prior to our visit in 2022. From the top of the road there was a spectacular view of Havannah Channel and surrounding area. The bad news: when they abandoned the site they cut deep swales across the road every 100 feet all the way to the top. It was for drainage, presumably, but it made hiking challenging; walk 100 feet, climb down 5 feet of loose rock, climb up 5 feet on the other side then repeat. It felt like we covered three times the distance and it was just as hard going down.

Close to the entrance to Roaringhole Rapids, near Turnbull Cove, is a new log dump with a fairly good road going up the hill and then north towards Nepah Lagoon. There are some excellent views and not too many deep swales cut into the road. As it heads north it joins older logging roads with more woods. We anchored in Turnbull Cove and rowed the dinghy to the log dump. It’s about a mile from the boat.

Many of the marinas in this area, including Port Harvey, Kwatsi Bay, Shawl Bay, and Greenway Sound have all closed in recent years. From the Jennis Bay Marina site on the north shore of Drury Inlet you can access a number of logging roads that provide excellent hiking opportunities. There is excellent anchoring in the bay if the marina is unavailable.

In 2023, we saw active logging in Greenway Sound near the old marina site, in Tsakonu Cove on the south shore of Knight Inlet and at the south entrance to Sargeaunt Passage. Make a note, in a few more years there may be hiking opportunities here as well.

Unlike the more developed hiking opportunities farther south, hiking in the Broughtons is often an exercise in exploration and discovery; we wouldn’t have it any other way.

Michael and Karen have been cruising the Salish Sea and beyond for more than 20 years, hiking every chance they get. For more resources for hikers visit their website at https://mvmischief.com/library/

The wind was up, the slip was tight, and the peanut gallery of marina neighbors had assumed their usual spots. Perched in cockpits, coffee mugs in hand, performing their silent critiques. As I backed into the narrow berth, a friendly nod came from a guy two slips down, the kind that says, “Nice job, skipper.” For a moment, I basked in the pride of a maneuver well executed. Then the unmistakable whir of the bow thruster echoed off the dock pilings. The nod became a knowing smirk. Pride gave way to sheepishness. Well, so much for impressing the locals.

Bow thrusters have become a flashpoint in the ongoing debate over seamanship,

technology, and what it means to “really” know your boat. Some sailors consider them a vital docking tool, the mark of a practical skipper who values control and safety. Others dismiss them as crutches; something that erodes boat-handling skills and cushions you from learning how your vessel truly moves. So, are they necessary? Or just nice?

To answer that, we have to begin with what they are. A bow thruster is a small propeller mounted near the front of a boat, typically in a tunnel running athwartships (sideways) through the hull, on an external pod, or in a retractable unit. It allows the bow to push port or starboard independently of the main engine or

by Gio and Julie Cappelli

rudder, making tight maneuvers much easier. They’re especially useful at slow speeds where most sailboats become sluggish or unpredictable, particularly in reverse. On some boats, especially those longer than 40 feet, have dual rudders, or with substantial freeboard, bow thrusters are included as standard equipment. But even on smaller vessels, retrofitting one has become a popular upgrade among coastal cruisers, liveaboards, and aging skippers who want to ease the strain of docking in dicey conditions.

There is a reason why cruisers of all kinds love them. Few chores spike your heart rate faster than docking in a stiff crosswind with current running and only

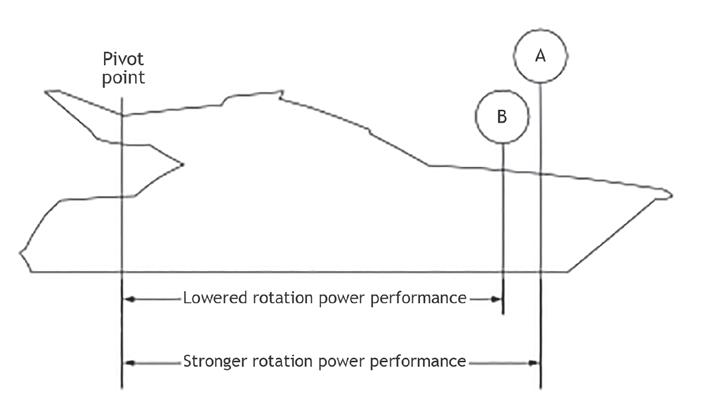

The farther forward a bow thruster is installed, the better rotation you'll have when using it.

six inches between your toerail and someone’s sparkling topsides. A bow thruster offers an escape hatch from that particular flavor of panic. It lets you correct a blown approach or counteract windage with the push of a button. When your crewmate is stepping off with a dock line, or when you’re alone at the helm trying to lasso a piling, having lateral control over the bow can prevent a whole host of mishaps—not to mention bruised egos.

For shorthanded crews or solo sailors, it can mean the difference between taking the boat out or staying within the safety of a slip. Owners can install a remotecontrol system in tandem with their controls at the helm that activate the thruster’s solenoid electronically. These remotes allow the operator to control the bow thruster from virtually anywhere on the boat, adding a valuable layer of versatility and convenience, especially when docking or maneuvering solo.

In crowded marinas or popular anchorages where space is tight and slips are narrow, bow thrusters can reduce the stress of threading the needle. They’re especially helpful on boats that catch the wind or water and complicate precise movements—those with high topsides, full keels, center cockpits, or tall rigs. On most production boats, they can only counteract wind forces up to about 20 to 25 knots, and many seasoned sailors acknowledge that docking a long, heavy vessel in close quarters requires a different skill set than sailing. In these

situations, a bow thruster can make a big boat feel smaller, nimbler, and far more forgiving.

A bow thruster can also be an invaluable asset during a soft grounding. Sea Otter Cove is one of the northernmost anchorages on the west side of Vancouver Island—beautiful and well-protected. However, its entrance channel is shallow, narrow, unmarked, and constantly shifting. Last summer during an early morning departure, our keel gently found the mud as the boat came to a slow stop in the shallows. With careful use of reverse coupled with the side-to-side maneuvering power of the bow thruster, we were able to wiggle free and get back underway with no drama.

Still, bow thrusters come with tradeoffs; starting with cost. Factory-installed units on new boats can easily add several thousand dollars to the price tag. Retrofitting a thruster into an existing hull is an even bigger undertaking. It requires hauling the boat, cutting a custom hole in the bow, glassing in a tunnel, running heavy-gauge wiring to a dedicated battery bank, and installing the control systems. A client of ours recently added a tunnel-style bow thruster to a 45-foot sailboat, with the total cost topping $14,000. The price can climb even higher if your boat requires a retractable thruster, or if installation is complicated by limited access or components, like a freshwater tank beneath a V-berth that must be relocated.

Another downside of bow thrusters is

their significant energy demand. Electric bow thrusters draw substantial power and their consumption increases with thrust capacity. Thrusters are typically rated by the amount of lateral force they produce (usually in kilograms) and by their corresponding power draw. Simply put, more thrust requires more energy. To see just how demanding these systems can be, we partnered with Skagit Valley College’s Marine Maintenance Technology Center in Anacortes. Using state-of-theart multimeters, we tested a 100 kg-rated bow thruster in operation. Our amp clamp recorded an inrush current spike of 1,231 amps at 12V DC, before quickly settling to the manufacturer’s nominal rating of 740 amps.

This highlights the need for properly sized and well-maintained battery banks, wiring, and connections. You’ll need to account for that in your electrical system planning. Some owners go so far as to add a separate battery bank forward to minimize voltage drops or sluggish thruster performance. On top of that, maintenance can be a recurring headache—especially in saltwater environments. Corrosion, maintaining zincs, marine growth, and motor failures aren’t uncommon, and most repairs require a haul out.

Modern hull designs favor flatter bottoms and shallower drafts near the bow. This makes it difficult to install a tunnel thruster far enough forward of the boat’s main pivot point for good leverage or deep enough to avoid cavitation.

A well installed bow thruster motor will have a protective barrier between its housing and electrical connections and loose items in the locker.

Retractable bow thrusters offer a solution to this challenge. A retractable bow thruster is a motorized propeller unit that folds up into the hull when not in use and is lowered into position when needed. Retractable bow thrusters allow for their installation to be farther forward, providing greater leverage, improved thrust and reduced drag, since the thruster remains enclosed within the hull when not in use. This is an especially valuable feature for racing yachts. However, retractable thrusters come with a larger price tag and require proper maintenance, as they can become jammed by marine fouling when neglected.

Perhaps the most overlooked drawback, though, is a subtle one: the potential erosion of boat-handling skills. It’s easy to let the thruster become a first resort instead of a backup tool. I’ve watched skippers hit the joystick before even checking wind direction or thinking through a spring line maneuver. When that becomes the habit, situational awareness and seamanship start to suffer. And if the thruster fails, which is a possibility each time it is used, you’re left reacting instead of handling.

Full keel or heavy displacement boats are another case. Many traditional cruisers track beautifully offshore but handle like shopping carts at low speed. Add a narrow marina fairway and some tidal flow, and things get complicated fast. I’ve been at the helm of one such boat during a docking attempt in a tight Pacific Northwest harbor, with a brisk

crosswind and an engine idle setting that surged just enough to foil any finesse. The rudder was useless, the reverse was sluggish, and the bow had a mind of its own. That was the day I truly understood the appeal of a bow thruster.

For those without a thruster—or for those who prefer not to rely on one— there are plenty of effective alternatives. Understanding how your boat behaves in reverse, especially in terms of prop walk, can turn what seems like a quirk into an asset. Strategic use of spring lines can let you pivot, pull in, or back out of a slip with surprising elegance. Even the timing of your throttle, the angle of approach, and how you use your momentum all play a role in fine-tuned handling. Some boats are even equipped with stern thrusters, which—while less common—can offer more nuanced control, especially on wide transoms. And of course, no substitute exists for a well-briefed crew. Good communication and practiced line-handling will always trump buttonpushing when things go sideways.

So, what’s the final verdict?

For newer skippers learning to handle a boat in crowded conditions, a bow thruster can be a powerful tool. Nice, certainly, but in many cases approaching necessary. For those with limited mobility, small crews, or a tendency to dock in challenging spots, it becomes an even more attractive asset. For skilled sailors who take pride in traditional handling techniques and enjoy the challenge of tight quarters, a bow thruster is still just nice. Something

This bow thruster needs some serious maintenance. Biological fouling can cause increased cavitation and deteriorated zincs can lead to galvanic corrosion.

to appreciate when it’s there, but not something you’d miss.

For us, a bow thruster remains squarely on the nice list. The price tag associated with the installation of a new bow thruster, for most, is extremely prohibitive. You can buy a small but capable near shore sailboat for the price of a bow thruster installation! Prudent seamanship means always having a plan A and plans B, C, or even D when it comes to docking. Success lies in recognizing the variables at play during each docking situation and preparing corresponding strategies in advance. Equally important is truly understanding how your boat handles. Dedicated sessions to hone close-quarters maneuvering, learning to use prop walk to your advantage, and practicing various approach techniques is time well spent, and often the difference between a smooth landing and a catastrophic one.

If you’ve got a bow thruster, there’s no shame in using it. And if you don’t, enjoy the quiet satisfaction of gliding gently into that slip without it—until you’re wedging into the last available space in Ganges with 15 knots on the beam and a boatload of witnesses.

Gio and Julie of Pelagic Blue lead offshore sail training expeditions and teach cruising skills classes aimed at preparing aspiring cruisers for safe, selfsufficient cruising on their own boats. Details and sailing schedule can be found at www.pelagicbluecruising.com.

Become a part of the 48° North crew! In addition to your magazine each month, with this exciting new subscription offering, you’ll also be supporting 48° North in a more meaningful way. But, warmed cockles are far from the only benefit. Others include:

• Annual subscription to 48° North delivered to your door.

• Two 3-day pass to Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival ($110 value)

• Northwest Maritime Center Member decal

• 10% discount on most items in the Welcome Center

• $100/year (additional fees for First Class forwarding or International)

THE

PLEASE: Our standard subscription gets you 12 months of 48° North and its associated special publications (SARC, Setting Sail, and the Official R2AK Program).

• $39/year (additional fees for First Class forwarding or International)

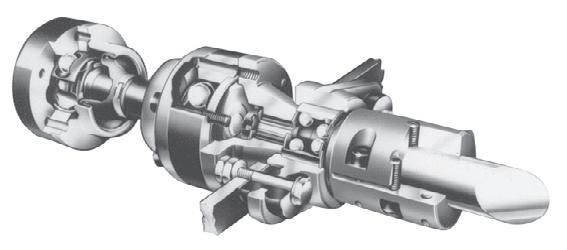

Business or Pleasure, AquaDrive will make your boat smoother, quieter and vibration free.

The AquaDrive system solves a problem nearly a century old; the fact that marine engines are installed on soft engine mounts and attached almost rigidly to the propeller shaft.

The very logic of AquaDrive is inescapable. An engine that is vibrating

on soft mounts needs total freedom of movement from its propshaft if noise and vibration are not to be transmitted to the hull. The AquaDrive provides just this freedom of movement. Tests proved that the AquaDrive with its softer engine mountings can reduce vibration by 95% and structure borne noise by 50% or more. For information, call Drivelines NW today.

by Lisa Mighetto

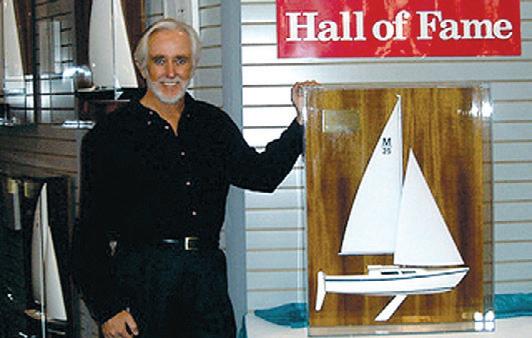

At first glance, Roger MacGregor comes across as every bit the engineer. He has a reserved, pragmatic personality focused on building things. When I met him at his home in Newport Beach, California this spring, he quickly moved the conversation from introductions and pleasantries to describing the architectural features of his house, which sits on a dock overlooking the busy harbor.

“This was a one-story building when I moved here,” he explained, pointing to the upper level he had added himself. After spending several days with Roger, I also saw an artistic, fun side that—at age 90—still gets caught up in the joy of being on the water while relishing aesthetic details. He designed the decorative stained glass that lines the railing of his wharf, for instance, and his 70-foot boat Anthem was recently named one of the “most beautiful sailboats of all time” by Sail Universe, the culmination of a career that began when he built his first vessel, Jolly Roger, at age seven. While Jolly Roger was a wooden rowboat, MacGregor recognized the potential of fiberglass early on, eventually outlasting his competition and engaging thousands of first-time boat owners.

During those sunny spring days, Newport Beach seemed a world away from my home waters in the Salish Sea. Yet MacGregor boats have a solid presence in the Pacific Northwest, extending Roger’s influence far beyond Southern California. His story provides a glimpse into an industry and lifestyle that evolved rapidly during the late twentieth century, transforming recreational sailing.

THE “FLAMING NUTHOUSE” OF COMPETITIVE BOAT DESIGN

California’s South Coast, located between Los Angeles and San Diego, is as alluring as a postcard, characterized by bluegreen water, golden sand, and tall palms swaying in warm breezes. Its surfing culture, borrowed from Hawaii after World

War II, adds to the charm. Yet this region also became an industrial powerhouse during the post-war period, with steel mills, auto assembly plants, and shipyards. The aerospace industry flourished here in the 1940s, thanks to the availability of a skilled workforce, universities that spurred research, and land. Roger, who was born in Pennsylvania and grew up in Ohio, moved with his parents to Southern California in 1948, joining the great post-war migration of residents from the Midwest and East Coast to the Golden State. He studied economics at Occidental College, where he met his wife Mary Lou, and after several years in the Air Force entered business school at Stanford University.

Here he began the project that would become MacGregor Yachts. “We had a couple of kids by then,” Roger explained, “and we wanted a boat where we could be reasonably comfortable and wouldn’t sink… and there weren’t any.” One centerboard sailboat he considered “would fall over just looking at it.” Wooden boats were heavy and had to be moored, which could be expensive. So the goal of his business school project was to design an affordable, unsinkable, trailerable boat that a family could use. After Stanford, MacGregor worked for Ford Motor

Co.’s Aeronutronic Missile and Space Division, where he was able to observe “Henry Ford’s original concept of a production line.” In 1964 he started his own boatbuilding business in Costa Mesa, up the hill from Newport Beach, while still employed at Ford. His new company’s first vessel was the West Wind, which Mary Lou, who was very much engaged in the business, described as “ugly as sin and fast as smoke.” When the number of employees reached eight, Roger left Ford, and by the mid1960s, MacGregor Yachts was off and running.

Many of Roger’s neighbors had the same idea. Estimates claim that 70 to 100 marine companies operated in Costa Mesa, which became the center of boatbuilding in the late twentieth century (Bradley Zint, “New Exhibit Tells ‘The Hull Story’ of Costa Mesa’s Boatbuilding Past,” Los Angeles Times, May 4, 2018). Sailboat companies operating along the South Coast included Catalina, Columbia, Cal, Ericson, Islander, Hobie, and others.

“It was a flaming nuthouse” of competing businesses, Roger recalled. “My street had probably 20 boatbuilders on it, and you couldn’t go anywhere without running into a truck hauling a boat or resin tanks” used to make fiberglass. They were “turning out thousands of boats. It was just unbelievable.” At lunchtime during the 1960s and 1970s, local restaurants filled with boatbuilders clutching drawings and financial plans, with “all the necessities of the industry spread all over the place.” Attracting employees was easy. “I’d put a sign out and 50 people came in,” he remembered. Keeping them was a different story, as rival companies lured workers away.

The proximity of all these businesses made the challenges of establishing a new company more immediate and more personal. “It’s one thing to compete with a company in a distant part of the country,” Roger commented. “It is quite another to compete with one across the street or just over the fence.” In the days before cyber espionage, Costa Mesa spies were lowtech, sometimes peering through fences and into the windows of rival operations. “What one company learned was captured by another in a matter of days, if not hours,” he marveled. Those who could not keep up were left behind. “It is the sailboat’s equivalent to Silicon Valley, only more concentrated.”

Listening to Roger talk about the early days in Costa Mesa reminded me of a movie from the late 1990s called “The Pirates of Silicon Valley,” about the cutthroat rivalry between Apple and Microsoft in the early days of personal computers

and information technology. As “pirates,” Steve Jobs and Bill Gates brought innovation, explosive growth, and, some would say, an aggressive, fierce culture to their companies. These entrepreneurs flourished because they seized opportunities, and they were at the right place at the right time.

The competition in Costa Mesa and along the South Coast quickly fueled improvements and efficiencies. Fiberglass, for example, presented boatbuilders with exciting possibilities, and MacGregor Yachts embraced the new technology. This glass-reinforced plastic, invented in the late 1940s, encouraged aerodynamic designs and monolithic hull construction. Unlike wood, fiberglass resists rot and leaks, making it ideal for boat construction and maintenance. By the 1960s and 1970s, it had become the dominant material in boatbuilding.

“Fiberglass could create incredibly complex curved surfaces,” Roger explained, “providing the designer with complete freedom regarding styling.” Aesthetically, MacGregor preferred a modern appearance with sleek lines, asserting that “the new fiberglass boats were far better looking than the wooden boats that they replaced.” While that is a matter of endless debate, fiberglass offered an unbeatable advantage: it was affordable, allowing thousands of new boat owners to enter a market that had previously excluded them.

Another way Roger kept costs down was to implement workstations geared toward specific tasks, patterned after Ford Company assembly lines. “That was my advantage,” he explained. “Each station had all of its tools, jigs and fixtures, parts, diagrams, and samples.” In fact, he designed boats with workstations in mind, expecting that each component would be assembled independently. This approach reduced the need for skilled labor, making production more efficient and less expensive. In contrast, other companies adopted a traditional approach, with the same skilled employees handling all sections of boat construction. Catalina was an example, and MacGregor spent some time in Los Angeles with owner Frank Butler observing his production techniques, concluding that he preferred his own workstations.

Roger described Butler as an “excellent boatbuilder,” someone he respected and admired. “I would rather take on General Motors as a competitor,” he commented, than “a motivated

individual entrepreneur, such as Frank Butler of Catalina or Jack Jensen of Cal Boats. With family-owned businesses, their money, egos, and pride are on the line,” driving a desire to succeed and “flatten the competition.”

Perhaps Roger saw himself in the entrepreneurs surrounding him. The social scene gave him ample opportunity to mingle with rivals, as every Friday night they met together at a local bar for “Boat Dealers’ Balls.” Emotions ran high, and these gatherings sometimes ended in brawls and fistfights. “It looked like the Wild West,” he mused, remembering the unbridled exuberance and lack of restrictions. There was camaraderie, too, as boat dealers sponsored football and baseball leagues and formed lasting friendships.

During the 1970s, Roger became pals with a fellow entrepreneur who shared a dream of building a company that would bring sailing to the masses: Hobart “Hobie” Laidlaw Alter. Inspired by the surfing culture at Laguna Beach, Hobie began building 9-foot balsa wood boards for his friends in the 1950s, eventually opening a surf shop in Dana Point. As a champion surfer, he helped revolutionize the surfboard industry by introducing polyurethane foam boards, which were lighter and faster than the old wooden boards. By the 1960s, his focus had shifted to catamarans patterned after Polynesian twin-hulled vessels. The introduction of the Hobie Cat 14—light, affordable, and easy to use—helped set a new sailing culture in motion. Hobie organized regattas, fostering camaraderie and competition among racers, many of whom were new to sailing. Later in his life Hobie moved to Orcas Island, but in the formative years of the 1960s and 1970s he was a legendary figure in Southern California.

MacGregor Yachts sold close to 50,000 boats, including catamarans, 65- and 70-foot racing yachts, and sailboats ranging from 19 to 26 feet. Roger attributes much of his success to boat dealers who helped with transporting, outfitting, and sales. He had dealers all over the world, but none sold more boats than Todd and Cheryl McChesney of Blue Water Yachts in Seattle.

Cheryl bought a MacGregor Sailboat in the late 1980s after seeing an ad in 48° North. While she had grown up boating in the Salish Sea with her family, this was the first vessel she had purchased. “Hey, I can get a boat,” she realized when she saw the price. “And I could trailer it, too,” eliminating the need for moorage. She later married Todd, who had sold her the boat.

Together, the couple devoted the next three decades to introducing many first-time buyers to the joys of boating. Cheryl guessed that as many as 75 percent of their customers were new to sailing, while the “rest were experienced sailors who were downsizing for easier handling or to trailer to lakes and farther destinations.”

Blue Water Yachts brought nearly 1,000 MacGregor sailboats to Pacific Northwest waters. “It’s the perfect boat for this location,” Cheryl explained. “With the distances you can cover under motor, you can actually get to places you couldn’t before.” And while many are content to explore the protected waters of the Salish Sea, some MacGregors have circumnavigated Vancouver Island and ventured to Alaska.

“We were fairly close,” Roger recalled of his neighbor. “Hobie was kind of my idol for a long time because he got a big business started.” One of the most memorable results of their friendship was a massive gathering of employees from Hobie’s company and MacGregor Yachts on the beach at Crystal Cove. Nearly 500 people attended the party, which included music blasting from a sound system on the bluff overlooking the sea, while participants roasted pigs in the sand. Caught up in the revelry, some of the employees fought over the food, eventually toppling the sound truck and sending it crashing to the beach below. “What a day,” Roger commented, remembering the arrival of the authorities who warned him, “you gotta stop this craziness.” Roger and Hobie were ordered to clean up the beach. “It was epic,” Roger concluded.

After talking with Roger, I visited Crystal Cove, now a state park, and tried to imagine the wild scene decades earlier. All I saw were quiet couples walking on a lovely beach, with pelicans soaring overhead and a few terns and seagulls running along the sand. It was a different era.

The McChesneys offered sailing lessons to all customers who wanted them. “We made the boats easy to sail from the cockpit,” Cheryl commented, and “we had the best instructor, Ray Copin, retired USCG Captain and aviator, who was himself a MacGregor owner.”

From the outset, the couple organized gatherings, including concerts, barbecues, and seminars, where MacGregor owners could socialize and learn more about their boats. Their annual MacGregor Rendezvous grew out of a Friday Harbor event they co-sponsored in the early 1990s with 48° North, called the “Plastic Fantastic Fiberglass Boat Festival,” a spoof on the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival. “There were lots of MacGregors there,” Cheryl remembered. “We made a grand entrance sailing together past the ferry dock to join the festival.” Today, the MacGregor Yacht Club of British Columbia continues the tradition of providing an annual rendezvous and an online space where owners can share cruising and maintenance tips.

By the early 2000s, most of the boat builders along the South Coast of California had closed shop or relocated. Environmental regulations, rising property values, and encroaching population increased the costs of operating in Costa Mesa, fragmenting the concentration of businesses that had spurred the innovation

and productivity of the past. MacGregor operated longer than many of his competitors, stopping production in 2014 when a retirement home emerged on the border of his plant. Although awareness of the toxicity of resin fumes was not widespread in the 1960s, by 2014 the business and regulatory environments had changed.

Blue Water Yachts continues to ship MacGregor parts to boat owners all over the world, a testament to how widespread MacGregor sailboats remain. Cheryl marvels at the far-flung destinations she never expected to find boats, wondering, “Really, they have water there?” Todd reports that the most remote location for a MacGregor sailboat may be Spitsbergen Island in the Svalbard Archipelago, about 600 miles north of the Arctic Circle, where he recently shipped a cockpit enclosure. He joked that the added protection would extend the owner’s sailing season “from three to six weeks.”

“Should we go sailing?” Roger asked on our last day together. Off we went to board Anthem, the second version of his “most beautiful” 70-foot boat. The breezy, sunny day in March could have passed for summer in Seattle. We backed away from the dock to enter a bustling harbor, weaving through a fleet of electric Duffy boats, various crews, power vessels of all sizes and shapes, and a few sailboats. We raised two of the five sails while still in the harbor. As our boat shot forward and heeled 20 degrees, I nervously glanced at the boats all around us. But as soon as we sailed out of the harbor on a reach, Anthem easily hit her stride and I relaxed, realizing that not only had Roger designed and built the boat, he had won the Newport Ensenada Race three times. We were in the best hands, and I sat mesmerized as we sped down the coast. Roger looked as content as I had seen him, clearly in his element. And I thought this is what it’s all about—getting people on the water, sharing the greatest sport and lifestyle the West Coast has to offer.

Lisa Mighetto and her husband Frank have sailed the Salish Sea in Murrelet, their MacGregor 26X, for 25 years, including a trip to the west side of Vancouver Island. She is grateful to Roger and Mary Lou MacGregor, Todd and Cheryl McChesney, and the Costa Mesa Historical Society for information and photos.

The author's MacGregor 26X

Vancouver Island’s Cape Scott is not a patch of water to be trifled with. Days of gales gave way to light breeze and sunny skies and we bounced along under sail, equal parts exhilarated and terrified. Suddenly, a dark shape surfaced off the starboard bow. A humpback! Practically eye-to-eye, we stood dumbstruck by the sublimity of the scene, watching its tail flukes disappear beneath the waves. That evening, we anchored in Quatsino Sound, not a soul around for miles. Otherworldly howls came from shore—the wolves several cruisers reported in the area. We pulled up another full crab pot, and couldn’t think of a place we’d rather be.

This was one of the most memorable journeys Frank and I have taken in Murrelet, our MacGregor 26x. Living in Seattle, we had only two weeks of vacation and could not afford to charter a boat. How did we pull this off? We trailered our boat to Port Hardy and took out a few days later at Coal Harbour. Conventional sailboats in Seattle traveled for weeks to reach the same destination.

Trailering a 26-foot boat is not for the faint-hearted, it’s a different skill set from sailing. Yet our boat’s trailerability has provided access to many cruising grounds we otherwise could not explore. And our 50-hp outboard allows speeds up to 20 knots, depending on the weight in the boat and whether the water ballast tanks are full.

Frank and I named Murrelet after a Northwest seabird, which, despite its small chunky body, is a fast flier, often seen streaking across the water. Murrelets nest on land, sometimes miles inland, reminding us of a trailerable MacGregor. We have devoted many hours searching for wildlife in our boat, often bringing friends and Audubon Society members along. Our retractable centerboard allows us to venture into shallow areas. Sure, we could do this in kayaks, but our MacGregor gets us and our guests home before dark.

by Medeea Popescu

The engine’s bass vibrations rumbled below me as I laid on the teak planks of the cockpit. The sun was out, the dodger blocked our apparent wind, and I was taking the opportunity to sunbathe in the late spring calm after many blustery and overcast days. Motoring our way west out of the Strait of Juan De Fuca, we’d just spent a rolly night at anchor in Thrasher Cove, the last protected anchorage on southern Vancouver Island before hitting

the mouth of the Strait.

Our destination was Barkley Sound or as far as we could make it—maybe the outer Broken Group or possibly all the way into Ucluelet if we had enough daylight. It was early June and the days were long, but our Nicholson 32, Aeoli, is not a speedster. She is a solid 1960s fiberglass boat with a full keel and 13,000 pounds of lead ballast. We were happy to be chugging along at around four knots against a slight

incoming tide and the long, smooth rollers pushing their way in off the ocean. We estimated that the 40 mile trip would take us at least 12 hours.

NOAA and the Canadian Weather Service told us to expect light and variable winds in the morning, with the breeze picking up through the afternoon. Using the motor is unusual for us. As new boat owners— one of us (me) a complete novice, and the other drawing on teenage experience lake

The islands of the Broken Group in Barkley Sound where the authors found shelter after a long transit.

sailing—we’re stubborn about pushing ourselves to stick to sails as much as possible. That approach had made for some very slow spring sailing around the San Juan Islands, as we found ourselves in wind holes, just a mile from some harbor entrance that was tantalizingly out of reach.

On this particular morning, we caved and fired up our little-used engine. We hadn’t learned to trust it yet, and maybe we shouldn’t ever get too comfortable. Every time we turn it on I worry that it’ll sputter out of breath and leave us drifting, pulled along by the powerful tides muscling along this rocky shoreline.

We’d taken our time exploring the Gulf Islands and spent several days in the unexpectedly wonderful Becher Bay, east of Sooke, hiking many miles of the regional park abutting the anchorage. Our decent weather was about to run out, though, and we’d found ourselves in a bit of a time crunch. A late-season atmospheric river was forecast to hit the coast the following

Tucked into the anchorage after a long day sailing out of the Strait.

day and we wanted to make it to Ucluelet for the brunt of the rain. Without a heater or shower on board, the pull of comforts at the marina was strong.

Every time we passed through a patch of wind, ripples gaining definition in the smooth blue expanse around us, I turned to Victor and asked, “Should we try sailing?” We pondered the question for a few minutes, squinting at the waves, sticking our heads over the side decks, trying to feel the difference between our apparent wind and the longed-for afternoon breeze. I knew that we should be grateful for the smooth trip down the Strait due to cautionary tales from fellow cruisers and notes in our old copy of the Waggoner guide, but it’s just plain boring sitting around burning diesel to get somewhere.

After two false starts—pulling the jib out, shifting into neutral, watching the sail fill lazily then collapse—we finally had enough wind to move us along at two to three knots. The rest of the afternoon

passed while the intensely green shoreline slowly slid past. We spotted whales diving and surfacing, close enough to smell their fishy sighs and blows. The clouds began to blot out the sun and it soon became time to put on thermal layers and drysuits again. We could see the grey wall of fog looming ahead of us, marking the end of the protected waters of the Strait. By this point, it was nearly 5 p.m. and we still hadn’t made it even with Cape Beale, which marks the southern extent of Barkley Sound. I was getting a little nervous as the waves rolling past us began to build. This was our first trip outside of the protected waters of Puget Sound, and neither of us knew what to expect.

Soon, we hit the wall of fog and were running nearly blind, with only the waves coming towards us visible—we weren’t sure if we’d be able to see the winking light of the Cape Beale lighthouse in the soup. Trusting our old Garmin chartplotter and the backup downloaded nautical charts

on our phone, we surged ahead in the building wind from the port bow quarter. The cruising guide warned us about the many reefs, rocks, and rips in the area, and we kept about two miles offshore. It was clearly going to be too late to make it into Ucluelet before darkness fell.

Accordingly, we decided to drop the hook in an anchorage tucked between Wouwer and Howell islands, part of the Pacific Rim National Reserve’s Broken Group. You enter the anchorage through a 500-foot gap between two tree-topped rocky outcroppings, and is described as having enough room for just one boat, with bow and stern anchor being preferable.