The new GPSMAP® 15x3 series delivers a bold 15.4" hybrid display, combining high-visibility sonar, detailed Garmin Navionics+™ mapping, and seamless integration with your onboard systems.

Available in standard key-assisted touchscreen, GPSMAP 1523. Or enhanced with preloaded coastal and inland maps, GPSMAP 1543.

C 15.4” keyed-assist hybrid display

C Built-in CHIRP, ClearVü™, SideVü™

C Preloaded Garmin Navionics+™ with Auto Guidance+™

C NMEA 2000® & OneHelm™ support

C Wi-Fi®, smart notifications, radar & camera ready

C Compatible with Panoptix™ & LiveScope™

Every boater knows the moment when a piece of gear doesn’t quite work as expected— the engine that dies, the sail that rips, the light that goes out, the block that blows up, or the line that parts. There may be some rolling of eyes or sleeves as you take a deep breath and accept that you’re going to have to dig into the fix. If you’re like me, there's a portion of your brain that celebrates having a new puzzle to solve, and an even bigger part that sets about reconciling the inconvenience because I never seem to plan for this kind of thing. All the while, I’m hoping things don’t go so poorly that I have to drain my amygdala that controls fear and anxiety, or my wallet and pride by calling for a tow.

I’ve been lucky in this way. While professional boat technicians would surely side-eye any of my jury-rigs, I’ve usually managed to effect an adequately functional repair; or at least have been able to make it back to the dock to reassess without much trouble.

In the last few months I’ve been aboard a couple boats with some cutting edge technology, a bunch of stuff I don’t begin to really understand. What I do understand is that a bit of that cool tech simply didn’t seem to work, and nobody on board knew what to do about it. The lack of functionality did not dominate or ruin either experience, but it was an aspect of my time on the water. Moreover, it highlighted the broad catch-22 with technology—it’s only as good as it is useful for the intended audience.

I’ll spare you any conspiratorial tinfoil-hat musings, but the platitudes and jokes about computer systems and connectivity in everything from your automobile to your microwave are becoming increasingly relevant to boats. As this happens, it’s fair for an average person to feel a little less agency. Do I know how to fix a car that’s as old as I am? Certainly not. I do, however, believe that my path to understanding how to do so would be more direct than learning to repair one manufactured in 2025. It’s always been easier to call for professional backup for complex repairs but, with the prevalence of integrated computer systems, it now seems like less of a choice and more of a requirement.

Cruisers who spend time offshore or in very remote waters are well practiced at selecting what kinds of systems they will rely on. Redundancy, simplicity, and repairability have always been prized attributes. This mindset hasn’t been a central part of my boating experience—I’ve been happy leaning into new technology in areas like sails, composites, and weather modeling; and relying (too unquestioningly) on the now-ubiquitous technology of combustion engines, 12-volt systems, and navigation software. But these next-level technological systems I encountered recently might change my calculus.

My boat dreams now involve my young family. While it’s entirely sensible to hope that our future family boat may allow certain modern conveniences, my main focus will be that it works—reliably and simply. And if it doesn’t, the right boat for me needs to have puzzles I think I can solve, or at least work around, on my own.

48º North

Volume XLV, Number 5, December 2025 (206) 789-7350

info@48north.com | www.48north.com

Publisher Northwest Maritime

Managing Editor Joe Cline joe@48north.com

Editor Andy Cross andy@48north.com

Designer Rainier Powers rainier@48north.com

Advertising Sales Ryan Carson ryan@48north.com

Classifieds classads48@48north.com

48° North is published as a project of Northwest Maritime in Port Townsend, WA – a 501(c)3 non-profit organization whose mission is to engage and educate people of all generations in traditional and contemporary maritime life, in a spirit of adventure and discovery.

Northwest Maritime Center: 431 Water St, Port Townsend, WA 98368 (360) 385-3628

48° North encourages letters, photographs, manuscripts, burgees, and bribes. Emailed manuscripts and high quality digital images are best!

We are not responsible for unsolicited materials. Articles express the author’s thoughts and may not reflect the opinions of the magazine. Reprinting in whole or part is expressly forbidden except by permission from the editor.

SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS FOR 2025

$39/Year For The Magazine

$100/Year For Premium (perks!)

Wishing you and yours a safe, happy holiday season,

This realization called to mind my days managing a sailing club and its 25 boats. Do you know which boats were always in service? The simplest ones. There’s a case for the intrinsic value of simplicity, of going without, of rejecting technological modernity on principle. I love a good backto-basics adventure, but that’s not quite it for me.

My recent experiences of boat-tech’s little foibles reinforce my status as a luddite for essential systems. My focus on simplicity is about reliable functionality in the best case scenario, and about my ability to address an issue (given my own technological limitations) when function inevitably falters. On the other hand, will a 12-volt ice maker fit in my stocking, Santa?

Joe Cline

Managing Editor, 48° North

www.48north.com/subscribe for details.

Prices vary for international or first class.

Proud members:

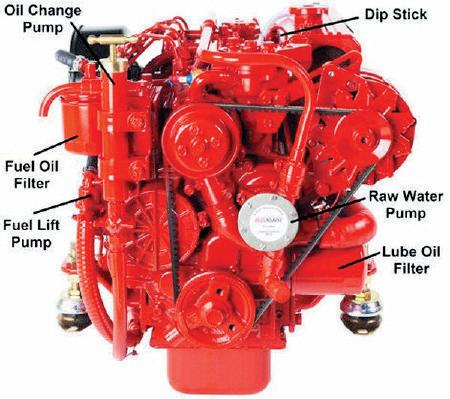

Beta Marine West (Distributor) 400 Harbor Dr, Sausalito, CA 94965 415-332-3507

Pacific Northwest Dealer Network

Emerald Marine

Anacortes, WA • 360-293-4161 www.emeraldmarine.com

Oregon Marine Industries

Portland, OR • 503-702-0123

info@betamarineoregon.com

Access Marine

Seattle, WA • 206-819-2439

info@betamarineengines.com www.betamarineengines.com

Sea Marine

Port Townsend, WA • 360-385-4000

info@betamarinepnw.com www.betamarinepnw.com

Deer Harbor Boatworks

Deer Harbor, WA • 844-792-2382

customersupport@betamarinenw.com www.betamarinenw.com

Auxiliary Engine 6701 Seaview Ave NW, Seattle WA 98117 206-789-8496

auxiliaryeng@gmail.com

Social Media Response to Jennifer Dalton’s Article "Threading the Needle" from the November 2025 Issue

Quinn Olson: Jennifer Dalton, nice article!

Michael Beemer: Jenn does a great job of writing and documenting this trip!

Johnny Faught: What a great article. So very well written and such detail. I had to look up the word “floe.” Such a perfect word for this moment. Thank you for sharing.

From Coast to Coast, We’re United in Our Differences of Perspective

Hey Joe,

I have been fortunate enough to spend time under the tutelage of many shops and mentors. Starting here in the Pacific Northwest, and then heading to Philadelphia and up through Maine before coming back to Seattle.

I have enjoyed conversations with tradespeople, owners, enthusiasts, working mariners, and old salts from all different waterways. Through it all, it seems that the bodies of water we interact with and our respective environments shape how we work and sail, and how we care for our boats.

I’ve been thinking about how my experiences in the Pacific Northwest, New England, and the upper Atlantic boating scenes compare. Each location has its challenges and benefits, with many shared attributes and plenty of distinct ones too. There is a good reason behind the old joke: “Ask three boat people a question, and get six answers in return.” And in my experience, this is true across every region. It makes a very rich and intriguing environment in which to work and play, doesn’t it?

All my best, Dustin Espey Dusty Marine Carpentry

48° North has been published by the nonprofit Northwest Maritime since 2018. We are continually amazed and inspired by the important work of our colleagues and organization, and dedicate these pages to sharing more about these activities with you.

Signs of fall come in many forms, and one of those is Northwest Maritime's Thursday longboating class—known as Team Longboat. Middle and high school students from the OCEAN alternative program in the Port Townsend School District come together for three-and-a-half hours each week to build their maritime skills, share community, eat some snacks, and enjoy the simplicity of being on an open boat on the water.

The group has used the good weather to learn rowing skills, practice docking, take a turn at the helm, and give commands to complete crew-overboard drills. On not-so-nice days, they have taken time to learn how to read weather—using both digital sources and their physical senses—practice reefing sails, and trying on the orange exposure suits.

Team Longboat even enjoyed some antics around Halloween— boating in costumes, rescuing a “pumpkin overboard,” and searching for a sticky substance in the bilge (rice krispy treats).

Every week is a fun adventure. Most of all, the group cherishes the time to slow down, focus on one thing, and put their minds into the small world of the longboat for a few hours.

» www.nwmaritime.org

Whether your scope is local and very challenging, or distant and unquestionably epic, as the Race Boss says, “Time to ruin your summer plans. This is it. The line between someday and I’m doing this.” The 2026 Race to Alaska (R2AK) and SEVENTY48 application window is now officially open.

As you know, R2AK is dramatically simple. 750 miles. No motors. No support. Just you, your crew, your vessel, and whatever mix of stubbornness and wonder got you this far. Port Townsend to Ketchikan. It begins June 14, 2026.

Before you apply:

• Read the Race Packet. It matters.

• Ask yourself if you’re ready. Then apply anyway. R2AK doesn't accept everyone, but Race HQ does read every word. Show them who you are. The start line won’t wait.

SEVENTY48 starts on May 29, 2026, and the application is now live. You’ve got 48 hours to move your human-powered craft—any kind, so long as it floats—70 miles up the Salish Sea from Tacoma to Port Townsend. Battle darkness, tide swings, and the moment when pain turns into something that feels a lot like pride. This isn’t just a race. It’s a full-body question mark with a finish line.

Before you apply:

• Read the Race Packet. It's the roadmap to your poor choices.

• Take stock of your gear, your grit, and your glutes.

SEVENTY48 is not looking for perfect, it's looking for people who are all in. Apply now.

» r2ak.com/r2ak-race-application | seventy48.com/race-application

It's that time of year again to bust out your boat's Christmas lights and decorations, gather your Seattle Christmas Boat Parade crew, and get ready to ring in the holidays. As in past years, the Lake Union parade route is sailboat friendly with no bridges to lift. Start time is at 7:00 p.m., December 13, and registered vessels should be checked in and lined up by 6:30 p.m. See you on the water for some yuletide cheer!

Once registered please hang your numbers on the port and starboard bow. Do not block or cover the numbers so they are clearly visible for the judges.

At 6:30 p.m., registered vessels check-in with “Salty Dog” on VHF 68 in front of Fremont Tug Boats, just east of the Aurora Bridge, directly across from Morrison’s Fuel Dock. Vessels line up west to east and head toward Gasworks Park at 7:00 p.m. The lead boat is Western Towboat. The route circles the lake and ends at Morrison’s North Start Fuel Dock, which is where the judges will be (and they want to hear your merry hoots and hollers!). Make sure judges get a good look at your bright, colorfully

decorated boat and visible parade number on your bow.

Christmas Boat Parade participants are also encouraged to join the toy drive supporting Seattle Children’s Hospital. Toy drive drop off and vessel number pickup is at West Marine, Ballard ‘Fish Shack’ from December 11 – 14.

» Sign up at seattlechristmasboatparade.com/sign-up-form. For questions about the toy drive, email parade@ seattleboatparade.com.

Gig Harbor Junior Sailing (GHJS) recently announced a generous $1,000,000 gift from the Stearns Family Foundation to support the sailing non-profit’s “Charting our Course” capital campaign. This transformative gift supports GHJS’s long-term goal of securing a permanent waterfront location, assuring the program thrives for many generations to come.

After more than a decade as GHJS’s leading supporter, the Stearns Family Foundation made an enormously impactful donation at this year’s annual GHJS fundraising auction. This significant gift will go toward the construction of a new youth sailing center, permanent dock access at West Shore Marina, and permanent use of uplands property at West Shore Marina. The announcement was followed by a rousing standing ovation, and there was hardly a dry eye in the room!

GHJS is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to providing equitable access to sailing programs that foster personal growth and youth development. For more than

16 years, GHJS has operated learn-tosail camps and racing instruction to over 3,992 youth in the greater Gig Harbor area. For the past three years, GHJS has also provided sailing lessons to the Boys and Girls Club of South Puget Sound. Sail camp students often progress to competitive sailing through Narrows Race Team (NRT), composed of nearly 50 racers annually from seven area high schools. Since its founding in 2014, NRT sailors have earned medals at regional regattas and qualified for national competitions in doublehanded, singlehanded, and keelboat racing.

GHJS believes that every young person should have the opportunity to learn to sail regardless of their financial circumstances. Thanks to generous community support and annual fundraising efforts, GHJS has awarded $143,400 in sail camp scholarships since its founding. Scholarships are near and dear to Stan Stearns’s heart. He grew up in Miami, Florida, and had a strong passion to sail but lacked the financial means to participate in the sport.

Through sheer grit and determination, he found a way to join and thrive on the local race team. Stan said of their donation: “Judy and I are fortunate to be able to give to our community. We give to Gig Harbor Junior Sailing because, well, it’s like Mickey Mouse Club, ‘Because we like you!’ We support youth and their pursuits of healthy recreation. Also, we have the satisfaction of seeing kids on the water rather than on their screens— it’s wonderful!”

GHJS looks forward to the partnership with the Stearns Family Foundation and other donors as they work toward a shared goal of delivering sailing opportunities for many years into the future.

» gigharborjuniorsailing.org

wind and waves were unable to effect a rescue.

Lodos deployed their Lifesling man overboard rescue device and made first contact with the two people in the water at about 11:22 a.m., then again about 11:25 a.m., at which time both were pulled carefully to the stern of Lodos. By about 11:27 a.m. both had been pulled aboard by the crew of Lodos. A few minutes later, they were transferred to a local hospital by a Kitsap County Sheriff ’s vessel and emergency services. One was suffering from hypothermia, but both made a full recovery.

The US Sailing Safety at Sea Committee awarded the Arthur B. Hanson Rescue Medal to the skipper and crew of the J/111 Lodos who rescued two crew who had fallen off another sailboat in the Possession Point Race on Puget Sound. The captain and crew of the Washington State Ferry Suquamish and sailboat Blue will also receive letters of commendation for their assistance in the successful rescue of both crew members.

The US Coast Guard and fellow competitors heard the call and began their response and convergence on the incident location as well. The ferry Suquamish heard the “Mayday” call from Blue and diverted from their regular EdmondsKingston run to assist. They placed their large ferry upwind from the two people in the water, which blocked the wind and reduced the wave state to enable safe reboarding onto Lodos.

The awards were presented at a ceremony in conjunction with the awards ceremony for the Puget Sound Sailing Championships hosted by Corinthian Yacht Club of Seattle on October 12, 2025. The medals were awarded to Lodos skippers Tolga Cezik and Rade Trimceski, and crew members John Mason, JJ Hoag, Drew Zangle, and Max Hanson.

The medal and letters of commendation were presented by Corinthian Yacht Club Race Chair Jonathan Anderson, who made the nomination, and Margaret Pommert, V.P. Safety at Sea for The Sailing Foundation and Chair of the US Sailing Arthur B. Hanson Rescue Medal Committee. The medal was presented on behalf of the officers, directors, and members of US Sailing.

The incident happened on Saturday March 8, 2025, at about 11:00 a.m., during the downwind leg of the Possession Point Race on Puget Sound. The Riptide 41 Blue encountered a 38-knot gust in large waves. The gust overpowered the boat, burying the sprit pole, which in turn damaged and disabled the boat, and spun it to weather. Lifelines were destroyed and two crew on the foredeck fell overboard. The crew on Blue quickly deployed their MOM 8 crew-overboard marking unit and hailed a distress call on VHF channel 16.

Lodos, owned by Cezik and Trimceski, was also competing in the race. At about 11:18 a.m., they saw the yellow inflatable pylon from the MOM 8 and the two crew in the water, about 0.3nm north of them. They immediately left the race, dropped their sails, and went to assist. Other racing boats were already on scene, but had not dropped all their sails, and in the high

The Arthur B. Hanson Rescue Medal is awarded to any person who rescues or endeavors to rescue any other person from drowning, shipwreck, or other perils at sea within the territorial waters of the United States, or as part of a sailboat race or voyage that originated or stopped in the U.S. The medal was established in 1990 by friends of the late Mr. Hanson, an ocean-racing sailor from the Chesapeake Bay, with the purpose of recognizing significant accomplishments in seamanship and collecting case studies of rescues for analysis by the Safety at Sea Committee of US Sailing for use in educational and training programs. Any individual or organization may submit a nomination for a Hanson Rescue Medal.

» Visit the US Sailing Hanson Rescue Medal website www.ussailing.org/competition/awards-trophies/the-arthurb-hanson-rescue-medal/ for more information about these awards, including nomination form instructions and guidelines.

Whether you’re an off shore racer, cruiser, or powerboater, taking a Safety at Sea course is an invaluable educational opportunity for skippers and crew. The Sailing Foundation’s courses will take place in Seattle on February 15 at Queen Anne Community Center and in Vancouver, WA on February 22 at the Marshall Center.

Registration is set to open in early December and once it does, you’ll want to sign up fast because these courses fill up quickly. To be notified when registration is available, go to the Sailing Foundation’s Safety at Sea page and sign up for the mailing list » thesailingfoundation.org/what-we-do /safety-at-sea

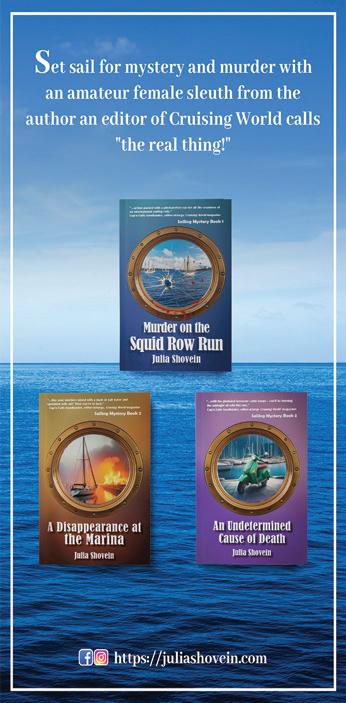

Longtime friend of 48° North and Vashon Island native, Chuck Skewes, has been cooking up something even more exciting than his grandmother’s Blackberry Pie recipe with fresh-picked Gulf Islands berries. Over the years, Chuck has been increasingly involved with the Baja HaHa, and he will now be at the center of this beloved West Coast group cruising event.

Of course, Chuck still owns the Ullman Sails lofts here in the Pacific Northwest and in San Diego, and he’s a co-leader of 48° North’s Cruising Rally as well (August 2-7, 2026, please join us!). But in addition to all of that, he’ll be filling the very big shoes left by the Grand Poobah, Richard Spindler. Knowing Chuck, he’ll thrive in this role with his laid-back positivity and good humor, not to mention his remarkable sailing knowledge that he happily shares with all. Congrats Chuck!

Here’s what Chuck sent in about being named the “Newbah”:

As you may know, the 2025 Baja HaHa was Richard Spindler’s last rally. He decided this after 31 Baja HaHas with anywhere from 45 to 220 boats each year; guiding the fleet down the Baja coast with two stops along the way, and facilitating activities, support, and of course the friendships made and strengthened.

If there was a choice, I would rather that Richard and Dona Spindler could

keep doing the Baja HaHa forever, but as we know that is impossible. At some point people have to go to the next stage of their life and pass on the torch of what was once their passion.

That time has come for Richard. I have done 10 Baja HaHas, several of those with Richard and Dona. We have become close friends, and shared wonderful times on boats and ashore in Mexico, San Diego, the Pacific Northwest, and the San Francisco Bay area. We have discussed how the Baja HaHa has brought Mexican and tropical cruising to thousands of

The Port of Bremerton recently announced the hiring of Tim Petrick for the Director of Marinas position. Tim will oversee operations at both Bremerton and Port Orchard Marinas, including routine maintenance, financials, and major construction projects.

Tim has over two decades in maritime experience, most recently serving as the CEO/Harbormaster for the Crescent City Harbor District in California. There, he oversaw a $2.5M operating budget and $10M+ worth of grantfunded projects, and managed a staff of 21. His public experience has been expansive, with Port leadership trusting that he will carry this knowledge to great use at the Port of Bremerton.

» To contact Tim directly, email timp@portofbremerton.org or call (360)813-0829.

people, and educated many on how to negotiate Mexican ports, Mexican culture, and the true joy of cruising in the country.

I am so honored to be chosen as the one to take this great event and keep the tradition alive. Assistant Poobah Patsy Verhoeven, who has been the backbone of much of the Baja HaHa, is staying involved to keep the transition smooth.

I hope to educate the general cruising public on what the Baja HaHa truly is and what it offers. Until I did my first one, I did not truly understand what it was. I thought it was just a party on your way down the coast. After my first rally, I felt that it would be foolish to enter Mexico without being part of the Baja HaHa. It offers not only a guide into this wonderful place, but safety in numbers. Many people have participated in more than three Baja HaHas and still see the value in it.

The event in 2026 is already being planned and I look forward to another great group of cruisers joining us down the coast and experiencing the dream of Mexican cruising. It never disappoints.

I, along with others, will miss the biggerthan-life voice of the Grand Poobah, but we have planned this transition to be as seamless as possible. Get ready for 2026 and the Newbah on the radio. I hope to see you there.

» www.baja-haha.com

by Bryan Henry

Isinglass, derived from the Dutch huizenblas, meaning “sturgeon’s bladder,” is a transparent gelatin derived from a sturgeon’s bladder. It’s used in glues and jellies and as a clarifying agent.

Ciguatera poisoning is the world’s most common type of seafood poisoning. Not commonly fatal, it can be very unpleasant.

Along the northwest coast of the United States and Canada, the stipes of bull kelp are made into pickles.

The cement secreted by mussels, which quickly hardens underwater, has possible dental uses to secure fillings and crowns.

Herman Melville, author of Moby-Dick , took his first sea voyage in 1839, departing New York for Liverpool on a sailing vessel.

1 Pirate’s flag, 2 words

5 Cape Hatteras state, abbr.

8 The flow of water in a particular direction

10 Crew member responsible for rigging and deck equipment

11 Shallow area of water

13 Hidden from view

15 Philadelphia state, abbr.

16 Up in the rigging or on the mast

20 Waterways

22 Vote of approval

23 Completion of a voyage, e.g.

24 Orange tuber

26 Adjust the sails for efficiency

27 Repair a sail, e.g.

28 Peach State, abbr.

29 Expert

31 First name of the main character in “Outlander”

32 Adjusted slightly

33 Storage container

34 Waterproof coverings

35 Follow a fixed course between ports, for example

1 Strong line or bar for securing sails

2 Florida Key

3 Boat propulsion device, 2 words

4 Receding tide

6 Lightweight boats

7 Tidal river mouth

9 Conger or lamprey

12 “___ Wiedersehen”

14 All the oceans of the world, 2 words

17 Allow

18 Rower

19 Violent storm

21 Droop

25 Distress call at sea

30 Skipper of the ship, short form

31 Triangular sail

The first locks are thought to have been developed in Egypt more than 2,200 years ago.

The first lock in the United States was built at Little Falls, NY, in 1793.

The first tow bridge in the United States was erected in 1654 over the Newbury River at Rowley, Massachusetts.

The first SCUBA diving apparatus was invented in 1771 by British engineer John Smeaton, the diver wearing a barrel that was connected to a boat by a hose, air being pumped through it by the diver’s companion.

The oceans are home to about 120 species of marine mammals.

The Antarctic ecosystem supports more than 200 species of fish, 12 species of whales, 35 species of birds, and six species of seals.

Minute sea animals called copepods outnumber all other animals on earth combined.

Of the original 13 American Colonies, Pennsylvania was the only one that was landlocked, having a short Great Lakes border but no Atlantic coast.

Michigan is the only state that borders four of the five Great Lakes.

Designing and building a chain hook that is easy to use yet strong enough to hold has long been a vexing problem, one which Mantus Marine has continually tried to solve. In their third generation M3 Chain Hook, they may have cracked the code. The latest hook has a likeness to a snap shackle, but with a more rectangular slot to capture a chain link. The M3 locks onto the outside of a single chain link, not through the middle, and will not slide down the chain. Even when the chain is unloaded, it can’t fall off. Designed to be used at the end of a snubber or bridle, the improved hooks fits the full range of anchor chain: BBB, Proof coil, high test, and stainless, and is available in 1/4-5/16in, 5/16-3/8in, 3/8-1/2in, and 1/2-5/8in chain link sizes.

Price: Starting at $83 » www.mantusmarine.com

Few things are more valuable on a boat than a trusty headlamp. Steamlight’s new Sledge headlamp is a rugged, rechargeable, flood beam headlamp engineered for versatility and performance across a variety of outdoor applications. It features dual power LEDs and provides multiple modes of lighting, including a THRO mode, which gives a short burst of 1,000 lumens when extra brightness is needed. Powered by the SL-B26® protected Li-Ion USB rechargeable battery pack, it can also operate on two CR123A lithium batteries. The Sledge is built with a polycarbonate thermoplastic body with an aluminum faceplate, an unbreakable lens, and impact resistance up 6 feet. The IPX4 water-resistant design ensures reliable performance even in wet conditions and a 45-degree tilting head allows for precise beam direction.

Price: $120 » www.streamlight.com

RAILBLAZA mounting systems has recently announced the launch of their new AnchorPoint smartphone holder, an adventure-ready mobile bracket that is built for the marine environment. With a five-point vice and no-slip silicon grips, the AnchorPoint keeps devices sturdily held through bumps, bounces, and rattles on the water. The holder also features four-point suspension vibration dampening technology to keep phones steady and footage crystal clear through every wave. The AnchorPoint has a 360-degree full-locking arm and is able to handle almost any device with an adjustable threaded dial. Its corrosionresistant aluminum build is ideal for the salt and fresh water, and is plug-and-play compatible with the entire RAILBLAZA ecosystem and StarPort mounts.

Price: $75 » www.railblaza.com

Become a part of the 48° North crew! In addition to your magazine each month, with this exciting new subscription offering, you’ll also be supporting 48° North in a more meaningful way. But, warmed cockles are far from the only benefit. Others include:

• Annual subscription to 48° North delivered to your door.

• Two 3-day pass to Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival ($110 value)

• Northwest Maritime Center Member decal

• 10% discount on most items in the Welcome Center

• $100/year (additional fees for First Class forwarding or International)

Our standard subscription gets you 12 months of 48° North and its associated special publications (SARC, Setting Sail, and the Official R2AK Program).

• $39/year (additional fees for First Class forwarding or International)

by Bruce Bateau

As the steward of three wooden craft, I look forward to the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival as a highlight of the boating year. So I feel guilty admitting that I wasn’t there this past September. Instead, my wife, Kate, and I loaded up Luna , our 19-foot catboat, with sleeping gear, a stack of books, and plenty of food and drink. Heading down our street away from

the highway and Port Townsend, I felt like I was experiencing a slower, sailor’s version of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. I’d taken the second week of September off for a mini cruise. In the weeks leading up to it, my mind was spinning like a compass dial, trying to settle on a destination. Should I go to the festival, just because I had the means to drive 200 miles each way? It would be fun, I’d get to hang out with old friends; yet getting there and back would eat up a

big chunk of my vacation time. Or maybe we should just go someplace more local?

A relaxing three-day cruise close to home won out.

How close to home? We started at the Columbia River, a mere eight miles from our house. Not in the scenic Columbia Gorge, or the mysterious backwaters of the estuary, but at the launch ramp near the runway at Portland International Airport. Admittedly, the industrial edge of Portland has less cachet than the

Olympic Peninsula. But launching after a brief 20-minute drive meant more time on the water and the opportunity for a more immersive cruise with an increased window to do whatever we wanted.

Despite our best weather forecasting, it rained as I rigged Luna. But by the time we were ready to launch, the sky was almost clear and an unexpected breeze had filled in. The rain had done its work and the river was nearly empty of other craft, so my only concern was keeping the boat moving upriver against the ever-pushing current. Our goal was Government Island, a 2,000-acre state park straddling the Oregon/Washington border, just four miles away.

Viewed with a jaded eye, the Columbia near Portland is a monotonous stretch of houseboats, sandy islands topped with cottonwood trees, industrial docks, and marinas. We took a more accepting, Zen view. Anytime our gaze scanned upriver, there was scenery enough—majestic with a touch of lingering snow, Mt. Hood hovered in the distance. For now, we opted to regard the commercial traffic as a curiosity, and the familiarity of our own river as an opportunity to reinforce our sense of place. It felt good to be on the water, to escape the orbit of home and the pull of daily life, all with a modicum of effort.

With a four-day supply of food and water aboard, we could roam or linger as we pleased. Government Island has free, well-maintained docks that are often lightly used in the fall. As a destination, the island is close to home, yet remote from city life.

The wind held until we reached Bartlett Landing, where one of the docks

is located. As expected, only a few boats were there, and one peeled away almost immediately. We tied up and sat in the cockpit, taking in the view downriver.

I watched the water flow past Luna’s transom. ‘Is it blue or silver?’ I wondered. Maybe it’s lime with a touch of muddy brown, giving way to a dull emerald? Whatever color it was, I sat there long enough to realize that the angle of the sun, combined with the reflection of the trees on the island, and the state of the tide, created a dynamic combination of hues that I was only able to observe because I’d taken the time to just sit and look.

During the next few days, we ate snacks without regard to meal time. We wandered up the beach, studying flotsam and jetsam along the shore, speculating on how a large, rusty anchor had been abandoned here, and carefully skirted an unsavory collection of beach chairs, odd junk, and a deflated raft. We watched huge barges come and go like components of an irregular clock, passing at all hours of the day and night.

In the morning, with Kate cocooned in the cabin, I drank tea in the cockpit under our tent that doubles as a bird blind (they can’t see me from above, so they fly past, unaware). A swarm of barn swallows flashed over the water, swirling upward like wisps of smoke, then alighting on the gangway. With the next bit of breeze they were off again, snapping up bugs too small to see, diving and rising through the air, then settling on the gleaming stanchion of a stout trawler farther down the dock. The swallows lingered long enough for me to glass them with my binoculars. They weren’t dull brown,

as I’ve always assumed. Instead, the birds gleamed with a blueish sheen that provided contrast against their crimson cheeks and forehead. I studied the swallows, enjoying their nuanced features. That is, until the captain, noticing his stowaways, emerged from his cabin and testily shooed them away.

Life at the dock was good. With no wind and no place to be, we couldn’t think of anyplace we’d rather spend three days. Chatting with the occasional sailor, reading, noticing plants growing in the cracks of a railing, we whiled away our time, seldom making it more than a few hundred feet from the boat.

Even when a wave of gray overtook the sky, our spirits remained high. We drank tea, watched a lone seagull circle overhead, and went for a swim. When I try to remember specific incidents of the cruise, I can scarcely recall anything, other than to say it was all supremely pleasant.

As our time came to a close, I realized that, regrettably, we hadn’t seen a single other wooden boat. Yet in our own way, we had embodied Ferris Bueller’s inquiry about his day off, “The question isn’t, ‘what are we going to do?’ The question is, ‘what aren’t we going to do?’”

If cruising can be perceived as laziness, we achieved it. We made few sail adjustments, completed no chores, nor did we travel far; but we did exactly what we set out to.

Bruce Bateau sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Oregon. His stories and adventures can be found at www.terrapintales.wordpress.com

by David Casey

My Uncle Jess was a tried and true powerboater, squeezing every usable ounce of function from his Chris Craft for fishing trips on San Francisco Bay or a water skiing adventure on Lake Berryessa, a large man-made reservoir not far from his home in Northern California.

My father, on the other hand—who at one time wasn’t a boater at all, but rather a weekend pilot—became more interested in sailing than fishing or waterskiing. He traded in his small Piper airplane for a Catalina 36 as a means to enjoy his retirement and spend more time with family and friends, reveling in the challenges of learning to capture the wind instead of Pacific salmon.

While my dad and his brother-in-law rarely argued about the superiority of sails versus engines, it’s a discussion that plays out again and again in the clubhouse and on the dock of my local yacht club. Though my experience is comparatively limited—this column is about my newcomer’s perspective as I launch into adventures on the Salish Sea, after all—I’ve recently gotten in on the action. It seems I’m amending, or at least evolving, my previously one-sided viewpoint. Each person’s preferences, tastes, and opinions on this topic should be respected and are inherently unique; the ones I’ll express below very much included. But mainly, it’s just plain fun to explore the relationships between different kinds of boats and the people who use them.

Since I followed in my dad’s footsteps by purchasing a sailboat a few decades after he sold his Catalina, I have been backing the sailors in the debate of which boat is better. But since selling our Columbia 28, Ariel, I have spent a number of afternoons aboard a 22-foot powerboat with a 150 horsepower engine. I must sheepishly admit that it didn’t take long for me to appreciate powerboating’s merits, despite memories of some rough and tumble excursions aboard my uncle’s vessel when I was younger. Accepting this adjustment of my perspective, though, has not been easy.

Growing up near San Francisco Bay, I often saw the romantic vista of sailboats dotting the Bay as I crossed the Golden Gate Bridge on a sunny afternoon. Like an Impressionist painting, the boats seemed frozen in time, yet still conveyed the energy of dancers in their balance between the wind and waves, leaving only a trace of froth in their diminutive wakes.

Setting aside the nostalgia of early morning fishing trips or lazy afternoon sails, the advantages and benefits from each type of boating really depend on conditions—including those of the boat itself—as well as the intended use-case and the point of view of the observer.

It’s not uncommon for sailors to claim that a sailboat is elegant and romantic. But if a vessel has more than a few nautical miles in its wake, then it might be regarded as either classically vintage or perhaps a bit tired, depending on its level of maintenance and care.

As my experience with powerboats increases, I find that they too, can be attractive, sleek and sexy; except those designed for fishing or other heavy work, then their aesthetics strike me as unsurprisingly practical and utilitarian.

No doubt, sailing can be captivating and enchanting. But when an outing takes place in difficult conditions, the resulting experience may be uncomfortable and maybe a little frustrating.

Similarly, powerboating is often fun and exciting, except when it occurs on a craft that needs some attention, in which case it may be a little noisy, bumpy, and smelly. And though many powerboaters will be able to take refuge from the elements while driving, like sailing, difficult conditions create their own challenges for these vessels and mariners.

Granted, my comparisons and descriptors are oversimplified, but like most generalizations, there is a kernel of truth to support them.

While I don’t believe that the battle for the best kind of boat is rooted in romance and nostalgia, both of those areas can play a role in a boat owner’s preference.

In my personal experience with boating, I have found that the balance between forces and resources like time, money, and the elements can make or break an outing aboard either a sailboat or powerboat. I know that I am not alone in the belief that there is a sweet-spot to boating—a point when ability meets challenge and design matches conditions, regardless of whether the power source of the vessel comes from wind or combustion. With sailing, I occasionally found such balance with sail trim. While I am no expert at setting and juggling the variation in sheets or other sail controls from the backstay to the downhaul, I did find that an ideal relationship between the jib and mainsail made steering a breeze, and course alignment steady.

of the last days

As I increase my experience with small powerboats, I am discovering a sweet-spot with regard to speed, which is dependent on the throttle rather than the adjustment of the sheets and halyards. The shift from plowing at low speeds to planing at higher ones demonstrates the obvious correlation to velocity. However, speed also seems to affect how the boat cuts through waves and swells, not to mention the rate of fuel consumption.

In a training session with our new boat-share club’s captain, I was reminded to cut across swells at an angle, and even reduce speed aggressively when moving through larger waves. I recently discovered the reason for the technique the hard way when my failure to throttle back as I cut across a large wave resulted in an airborne jump and a startling slam for me and my on-board guests—an event which never occurred on our masthead sloop.

But I’ve also noticed that an uncomfortable resonance effect can increase the lift and drop of a powerboat when the speed matches the frequency of the wave. Changing that speed, either slower or faster can eliminate the aggressive leaps across the water, but as yet, I’ve been unable to find a formula for this condition-dependent sweet spot. For now, a reduction of speed is my go-to solution to alleviate the rough ride, but I’m planning to experiment with an increase in velocity sometime in the future.

In addition to rough rides, I’ve experienced another frustration with the speed of a powerboat, or more specifically the issue of control while keeping speed low.

On a sailboat, I find that the rudder provides ample control even when crawling through a marina at every speed (greater than 0.0 knots). While it took me a while to learn how to maneuver our three-and-a-half ton Columbia sailboat into her slip comfortably and without incident, I eventually understood that the momentum of the heavy vessel allowed me to “coast” into the marina about 50 to 100 yards before coming to a slow stop.

As I familiarize myself with small powerboats, I am learning a simple, obvious fact that anyone who has piloted these boats takes for granted. The pivoting prop provides control, eliminating the need for a rudder. But for me, that means that a powerboat in neutral has no turning ability, even if it has way on. No power equals no steering.

However, I am slowly learning to use the engine as a steering device, employing the rapid response of reverse to avoid minor collisions with the dock and, god forbid, another boat in the marina.

Among the various pros and cons, simply put, going fast is fun, even if speed is achieved through wind power, which is another element of the sail-power debate. Owners of cruising sailboats brag about “flying through the water” when they achieve speeds more than 7 or 8 knots. Famous mockumentary reference notwithstanding, one of the racers in my club even proclaimed the feat of achieving high speeds by naming his vessel, Goes To Eleven. Compared to my Columbia 28’s max hull speed of 6.2 knots, that’s quite impressive. But the 22-foot powerboat I’ve been using plows along as a displacement vessel at that speed and seems begging me to let it break free even when she is cruising at a comfortable 22 knots.

Speed comes with a price, though. I think I topped off my sailboat’s 12-gallon tank once a year, since the 9.9-horse Yamaha outboard merely sipped fuel at its cruising speed of 3 or 4 knots. But every hour traveling at high speeds in a powerboat requires about 7 or 8 gallons, at least. And in discussing the topic with owners of much larger powerboats, I consider myself lucky to consume even that modest quantity.

There is one area in which neither sailboats nor powerboats have an advantage, and that is the issue of maintenance. I don’t think there is a boat owner alive, regardless of their vessel’s default power source, who is not at one time or another frustrated and annoyed at the amount of time, money, and effort required to keep their boat in proper working order. Sailors have the added component of rigging and canvas. Powerboaters have more engine functions to care for and perhaps more systems as well.

Despite my personal oversimplifications, considering the array of challenges and disadvantages in balance with the ample rewards and benefits of various boat types and designs—I’m far from ready to settle the debate of which vessel is better, sailboats or powerboats. At the moment, thanks to my time aboard both types of boats, I’m not really sure which one I’d choose given the opportunity.

One thing is for sure. If I ever win the lottery and my ship comes in, I think that I’d just take one of each.

David Casey is a retired math teacher, and woodworker. After relocating from California, he and his wife Laura enjoy exploring the vistas of Puget Sound from the deck of a boat or a promenade along its shores.

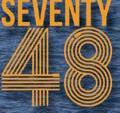

by Julie and Gio Cappelli

Idistinctly remember the only day, or rather night, that I appreciated having a code zero onboard Sea Fox . We were late leaving the Magote just off La Paz where we’d been anchored for the past week provisioning for an anticipated three-week passage to the Hawaiian Islands. The sun had just started to set as we motored out the long channel along the Malecon that we’d come to enjoy walking each day as we set out on our various shopping and exit paperwork adventures. It’s unusual for us to depart so late, but with all the boxes checked and more familiar boats rolling into the anchorage each day, we knew we had to make moves or we’d be dancing the La Paz waltz for at least another week.

The overnight sailing forecast was dismal at best; 5-8 knots, mostly on our nose. In apparent winds over 10 knots, our Malö 39 Sea Fox, can point to an impressive 30 degrees, but at these low wind speeds we weren’t going to hold our breaths for big miles or easy sailing. As we rounded the final channel marker and surveyed the serene Bahia de La Paz, now completely placid and calm compared to the whirlwind of boats and gusty winds that greeted us upon our arrival all those days ago, the puffs of wind we’d hoped to find vanished almost in unison with the setting sun. The wind speed, and boat speed, dropped precipitously just in time for our watch change. I lamented leaving poor Gio to figure out how best to catch the patchy, pathetic puffs while I hopefully caught some sleep. I halfexpected the next sound I heard to be the rumble of the engine.

Instead it was the muffled cursing and sharp report of metal on wood that woke me up. Just one snap shackle glancing off the mahogany bulkhead led me to the same solution Gio had come to: the code zero.

Shoved into the forward head we use primarily as a sail locker and overflow stowage staging area, our code zero was practically brand new and came with the boat when we bought her in San Diego just six months prior. It served us well in the light airs of San Diego Bay, but the more we used it the more we wondered how it would fare under the pressures of rigorous offshore cruising and our eventual return to Pacific Northwest waters in coming months. Dacron sails, such as our mainsail and 125% furling genoa, are remarkably forgiving when it comes to withstanding the punishments of passagemaking. Layers of thick, robust fabric coupled with robust stitching, a healthy dose of chafe protection, and UV protection can keep these white wonders full for years, sometimes decades. Our sailing mentor and partner John Neal regularly cruised 50,000+ miles with his suits of white sails built by Port Townsend Sails. But code zeros are different.

Initially introduced in the racing world, code zeros are a breed of awesome and awful that has taken the sailing world by storm. They are those sneaky in-betweeners that fill the sweet spot between a genoa and an asymmetrical spinnaker. They’re built light and cut flat, with a luff designed to work around a torsion cable so they can furl cleanly, often on a removable, stowable

pancake furler such as ours. In the right conditions they can feel magical, giving you that much sought-after lift in the lightest of zephyrs, extra pace on tight reaches, and a potentially forgiving option for coastal cruising. In our experience they (rarely) behave nicely, they (occasionally) roll up tidy, and they sure do turn those marginal puffs into honest boat speed, which is why cruisers and racers alike treat them like a coveted secret weapon. And when morale is taking a nose dive or the engine hours are already piling up, having a sail that keeps the boat moving instead of wallowing can make a watch feel less like drudgery and more like you’re actually sailing again.

But for all that charm, code zeros aren’t pure upside. Some sailmakers will tell you that a “code zero” isn’t even one thing anymore. Cruisers, racers, and racer-cruisers all get different fabrics, different load paths, and different crossover angles. The laminates that make them powerful in drifter conditions are remarkably easy to overstress if you tend to get overeager in a building breeze. Because they sit in that awkward gray zone between a headsail and spinnaker, they can feel fussy, even sluggish, to trim and they’re not much use deep downwind. We’ve read that the upwind performance is dismal too, but ours pointed pretty well; sometimes as high as 45 degrees in 5 knots.

Then there’s the lifestyle tax: the dedicated continuous furler and control line, the heroically long two-part purchase halyard required to haul the thing up to the masthead to create enough tension for proper sailshape and furl-ability, the storage footprint, and the reality that laminate fabric ages much faster than your trusty Dacron. Most sailmakers will tell you to expect something like three to five seasons of healthy use if you’re flying it regularly, a little longer if only use it in the truly light airs and furl it immediately as the wind picks up.

While a code zero promises to fill that delicious middle ground between motoring in a limp breeze and wrestling a full kite, the question that matters is whether it solves a problem most cruisers really have. In light air reaches, it can be a showstopper; shaving hours off coastal hops or offshore passages. Shorthanded crews in particular tend to appreciate that while the sail flies easily, the sheer size, weight, and sensitivity in changing conditions means it still demands a respectable amount of respect when in use, particularly during hoists and drops and in shifting wind conditions.

Having it on a furler certainly simplifies the situation, but it demands judgment, space, and a willingness to swap sails when the angle shifts (and typically a second person). It can absolutely be a quiet champion for sailors who spend real time reaching in light air. For everyone else, it risks becoming one more expensive, delicate embellishment that mostly snoozes in the sail locker, waiting for that perfect but rare day. And this is the heart of it: a code zero usually doesn’t save your passage, it just makes a handful of hours happier, faster, or less demoralizing. If that’s a pain point in your sailing life, the sail earns its keep. If not, it probably won’t. Plus, because the design and materials used for these sails evolve quickly, they historically hold resale value poorly—so buying one “just to try it” is rarely a financially graceful experiment.

A code zero can feel tailor-made for the Pacific Northwest’s moody summer wind patterns, where you spend half the day

The pancake furler on Sea Fox required the fabrication and installation of a custom bowspirit, heavily reinforced to handle its load.

in a teasing 6-10 knots of wind and the other half wondering if the forecast forgot you wanted to sail that day. In the Strait of Georgia, or crawling up Johnstone Strait on a glassy morning, it might keep you sailing instead of firing up the iron genoa. But the flip side here is sharper than elsewhere: the breeze can spike fast when thermals kick up or you round a headland, which can make flying a light laminate sail a real liability. And before you get seduced by visions of ghosting out the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the light air reach of your sailing dreams, it’s worth evaluating whether your bowsprit or anchor roller assembly can actually handle the load a code zero will add to it. These sails pull hard, and any marginal hardware will be found out quickly.

Even with clear decks and simple rigging, ours took at least an hour, sometimes longer, to set-up and deploy; and about the same at the end of its deployment. That alone might give you pause. If you rarely pull the code zero out, that hesitation turns its use into a negative feedback loop. The less you use it, the clunkier the set-up feels, and the more likely it is to turn into that “maybe later” sail that never leaves the locker. You’re most likely to use it on those rare dreamy summer afternoons when the wind is gentle, steady, predictable. That’s the local calculus: is a sail that’s magic for maybe twenty days a year still worth the space, cost, and care? A good code zero thrives on steadiness of wind angles and pressure, neither of which the Salish Sea reliably delivers. That doesn’t make it useless, just very conditional.

In the end, a code zero is classic Pacific Northwest temptation. It’s undeniably fun, occasionally brilliant, and absolutely not essential for most cruisers. It won’t replace your genoa, it won’t rescue you from the region’s moody gusts and dead zones, and it won’t see enough use to justify itself if you’re chasing practicality. But on those rare, golden afternoons when the breeze is soft and steady, it can make the boat feel lighter, happier, and maybe even a little magical. If you delight in dialing in your sail inventory and savor the art of coaxing speed from whispery winds, it might be a lovely indulgence for you. But if you’re looking for something that transforms everyday cruising here in the PNW or in the warmer waters of the Pacific, this one stays squarely on our Nice list.

Speaking of warmer waters. It’s a little ironic that I’m writing this article at anchor in Baja California Sur, the code zero long gone from our inventory, and somehow I don’t miss it even a little. Our passage to the Hawaiian Islands was rolly and fast; the code zero never saw the light of day. Same for the couple of months of cruising we did there. And the passage from Hawai’i to Ketchikan. And the next three months of cruising the west coast of Vancouver Island. And several more laps around Vancouver Island with sail training expedition crews. So, it should come as no surprise that before departing on our current anticipated 15,000-mile cruise we evicted lonely code zero. Hopefully it is enjoying a home where it will see more miles and bring more smiles.

Gio and Julie of Pelagic Blue lead offshore sail training expeditions and teach cruising skills classes aimed at preparing aspiring cruisers for safe, self-sufficient cruising on their own boats. Details and sailing schedule at www.pelagicbluecruising.com.

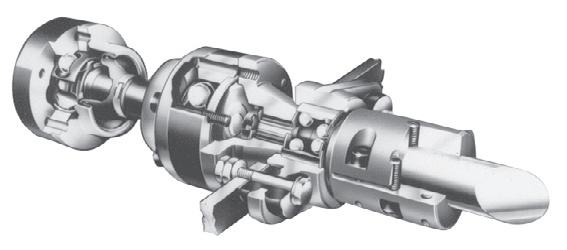

AquaDrive system solves a problem nearly a century old; the fact that marine engines are installed on soft engine mounts and attached almost rigidly to the propeller shaft.

The very logic of AquaDrive is inescapable. An engine that is vibrating

on soft mounts needs total freedom of movement from its propshaft if noise and vibration are not to be transmitted to the hull. The AquaDrive provides just this freedom of movement. Tests proved that the AquaDrive with its softer engine mountings can reduce vibration by 95% and structure borne noise by 50% or more. For information, call Drivelines NW today.

by Michael Boyd

Photos by Karen Johnson

The northern half of Vancouver Island’s West Coast has long been the domain of those with the time and spirit to do a circumnavigation, and these rugged and remote destinations are undeniably special for that reason. On the other hand, Clayoquot and Barkley Sounds in the southern half of the island can easily be reached from Puget Sound without committing to a circumnavigation; just head west out the Strait of Juan de Fuca. It’s even easier now that there is a marina in Port Renfrew to break up the long haul between Sooke and Barkley Sound.

Here’s the exciting part: we find these more accessible West Coast cruising grounds every bit as amazing for boaters. It won’t be surprising for regular readers, but part of that draw for us is the presence of some outstanding hikes along this stretch of coast. Here are a few of our favorites in the southern half of the island, from north to south.

Hot Springs Cove is a narrow inlet just off the ocean at the northern entrance to Clayoquot Sound. As you turn in, you can see the steaming hot springs waters falling over the rocks into the inlet and, about a mile farther, a public dock where the inlet widens. We like to anchor in this wide area, but not close to the dock.

Hot Springs Cove has become a tourist

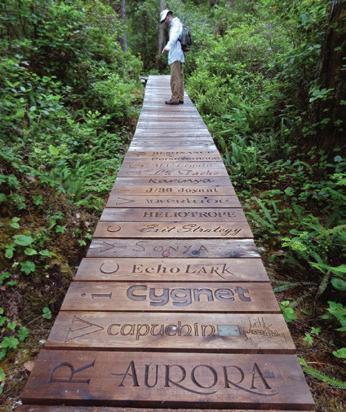

Reading history on the Hot Springs Cove boardwalk.

mecca. It’s not the passing cruisers, but rather the steady stream of tourists coming from Tofino by high speed boat or float plane and landing at the dock throughout the day. This all comes to an abrupt end at about 6:00 every evening, the perfect time to disembark and dinghy to the dock.

While it’s fair to be focused on the dreamy and steamy destination, there’s a lovely walk to enjoy getting to and from the hot springs. From the dock, a path leads a mile south to the hot springs— much of which is boardwalk with boat names carved into the boards. We stopped at the changing shelter and left our boots and socks then climbed down to the hot water.

There is actually a stream filled with hot water that tumbles over a waterfall (hot shower time but no soap, please) and through a series of pools before entering the inlet. If the tide is right, the lowest pools may fill alternately from the

hot stream and the cold inlet making for a unique experience. Wonderful. And we had it to ourselves for almost an hour.

When we got back to the shelter I found one of my boots was missing. A search was undertaken and we found it in the bushes not too far away where no doubt some small animal had dragged it. It seems even the popular hikes can have wild encounters here on the West Coast.

In the southeast corner of Flores Island, Matilda Inlet has several points of interest for the passing boater. About halfway down on the west side of the inlet is the small community of Ahousat with a long public float, general store, and fuel dock. It’s worth a stop, if only to talk to the residents. A bit farther along, the inlet divides with the eastern arm leading to the First Nations community of Marktosis. The western arm continues to an anchorage at the head of the inlet.

Anchoring can be tricky since much of the water you see is too shallow at low tides. But if you consult the chart and your depth sounder, you won’t find it too difficult. The holding is excellent.

The trailhead near the anchorage is easy to recognize; there is a large stone and concrete basin that is supposed to contain lukewarm, sulfur spring water, though it was pretty cold and stagnant when we were there. You are now in Gibson Marine Park. Following a common pattern on the West Coast, a short trail goes through woods and marsh, with many of the wettest places covered by boardwalk. After a half-mile this primitive access trail ends at a beautiful, wide curving sand beach on the ocean at Whitesand Cove. This is the junction with the Wildside Trail which can then be followed along the shore in both directions. The trail to the east ends in the village and the much longer trail to the west ends at Cow Bay. This latter

section includes a crossing that must be done at low tide (or a long, difficult detour.) You may meet other people here since there is a primitive campsite for kayakers at the eastern end of Whitesand Cove. If you’re here in August, it could very well be foggy.

Located at the northwest entrance to Barkley Sound, the town of Ucluelet is both a major destination for tourists coming by road from Victoria and a very welcoming stop for West Coast cruisers. There is plenty of room to anchor near town but we prefer to tie up at the Small Craft Harbour which has good facilities and is only a short walk to the center of

town, and an even shorter walk to the local coffee shop.

From the marina, it’s only a few blocks’ walk on city streets to the ocean side of town. But this time, it’s not a beach but a developed trail called the Wild Pacific Trail that mostly meanders along the top of cliffs overlooking the ocean. Trail sections called Artist Loops provide access to particularly scenic overlooks and even storm-watching decks. We like walking it from both directions since the views are always different when you are looking over your other side.

At the south end, separated from the main trail by a road walk, is a loop around Amphitrite Point that includes passing the lighthouse. Since there is a public

road almost to the light, this section is often crowded but worth the walk for the fantastic views in almost every direction. From the start of the loop around Amphitrite Point to the trail’s north end is about 5.2 miles, not including the 1.5 mile necessary road walk separating the north and south sections. But there are many access points along the trail so you can easily do only part of it at a time. In fact, we like doing the north half one day and the south half another. Between the city amenities and the great trail, Ucluelet is always a worthy stop for West Coast cruisers.

Juan de Fuca about half way between Sooke and Barkley Sound, is remote enough that only a West Coast cruiser would be likely to come here. Which is why Botanical Beach, located just east of the entrance to Port Renfrew, is included in this list, even though it isn’t strictly on the West Coast.

Botanical Beach is a popular destination by car from Victoria, but getting here by boat is another matter. The inlet of Port Renfrew is uninviting, being completely open to the southwest. One possible refuge is the new Pacific Gateway Marina at the head of the inlet on its southeast shore. The other, which we’ve used, is a small one-boat anchorage called Mill Bay, located behind the Woods Nose group of islets. From here, the Mill Bay Trail leads to a road which ends at the Botanical Beach parking lot and the loop trail to the beach. From the marina, it’s a bit longer.

Botanical Beach offers one of the best places to view intertidal marine life on Vancouver Island. It’s a must-visit destination at low tide. You can walk a long way out across flat sandstone and granite outcroppings with tide pools filled with multi-colored sea stars, urchins, anemones, sea cucumbers and more. So significant is this location that a research station was first established here in 1900. Though visiting here by boat is challenging, it remains one of our most loved walks when cruising the West Coast.

From Mill Bay it’s a bit over a mile to the Botanical Beach parking lot; from the marina it’s around 2 miles and you might

be able to schedule a taxi. The loop trail from the parking lot to the beach is about 1.9 miles, longer for true beach explorers. The tide should be 4 feet or less for the best tide pool viewing.

Whether circumnavigating or heading west from Puget Sound via the Strait of Juan de Fuca for an out-and-back voyage, there are rewards aplenty along this beautiful and inviting southern section

Tying up the dinghy at Mill Bay landing beach.

of Vancouver Island’s West Coast. You won’t regret your choice to venture out and enjoy the many anchorages and hiking opportunities that it has to offer.

Michael and Karen have been cruising the Salish Sea and beyond for more than 20 years, hiking every chance they get. For more resources for hikers visit their web site at mvmischief.com/library

(Water, Algae, Sludge and Particle Removal Service) Changing filters often?

Don't let bad fuel or dirty tanks ruin your next cruise!

Whether you're cruising the Pacific Northwest, heading for Alaska, Mexico or around the world, now is the time to filter your fuel & tank ... before trouble finds you ... out there!

THURSDAY - SATURDAY 9:30 AM - 3:30 PM

by Andy Cross

Sitting in a 15-foot RIB at the pin end of the start line, my arms are crossed over my life jacket and an orange whistle is clasped in the side of my mouth. I’m watching closely while Optimist sailors jostle to get up on the line. With sails luffing, then filling, then luffing again, some are on time, several are early, and others are late. From my vantage point, I pick out the sail numbers and life jacket colors of those I think are going to be early and intently watch what they're doing to identify tips I can give them afterwards.

“5, 4, 3, 2, 1, BLAST!” The race is on… sort of. It’s a practice start, one of many we’re doing in this training session, so I blow the whistle several times to call the fleet back for a restart. In choreographed fashion, they ease their sails and bear away or tack to come back down to the line.

As I’d expected, three boats were over early, but several others absolutely nailed the start. I motor over to one of the students who was over early, hold on to the side of his boat, and offer a drink of water with my compliment sandwich: “I love how much speed you had coming off the line, unfortunately you were over early. The boat below you wasn’t very close, so in that situation I’d like to see you use some of that space to burn time—come down a bit, then back up, luff the sail, and hold your lane. Also, your body position in the boat was much better than the first start, so keep that up.”

In a Caribbean islander accent, he replied, “Yes, coach.”

“Good, go have fun!” I respond while motoring to the next boat.

Later, in the debrief session at the yacht club, our group of coaches talked to the kids about starting strategy and how to put themselves in a good position to succeed on the start line. In my mind, there is a lot to that sentiment of getting yourself into positive spots, not just in sailboats. Sailing is the medium that teaches that lesson, but it can be applied to other aspects of life, too.

The idea of getting yourself into scenarios for success is something that has been filed in my teacher-brain for quite a while. I’ve employed it as an instructional tool when teaching lots of different types of sailors; from coaching kids and adults in racing, to leading cruising and offshore sailing classes in a variety of locales. I have a broad memory bank of tidbits like this, which have come over many years of spending time on the water, especially in the teaching capacity. This past summer marked the twentieth year that I’ve been instructing sailing, and my passion for getting people excited about the sport and lifestyle has only strengthened. That passion also extends into my writing, which I hope inspires and informs.

In that vein, the intent of this article is not to give readers my resume, but rather to provide some insight into what my varied experiences have taught me about sailing, teaching, and learning. After all, every good teacher is also a continuous learner, and the same is true of sailors. No matter how much time I spend on the water, I’m always learning from other coaches and instructors, from my students, and even from the ocean. Here are some reflections and takeaways from my twenty years as a teacher.

When I was 21 and fresh out of college, I started teaching sailing at a summer camp in Florida working with 8- to 16-yearolds. I really enjoyed and connected with that age group because I could see firsthand how much progress they could make in a short amount of time. Also, I appreciated how their innocence and trust could lead to pure learning and joy in the sailing environment.

Not only did that first teaching experience create a deep connection to the kids, it showed me how close sailing coaches are when working together towards a common goal. There aren’t that many jobs where your coworkers become such fast friends, with little to no competition between one another, and a level of information sharing that is admirably high-level. We all wanted our kids to succeed and, by focusing on that, we all wanted each other to be successful as coaches.

Fast forward to 2025 and I find myself at the Sint Maarten Yacht Club in the Eastern Caribbean coaching kids this age for the first time since that summer. Jumping back into this type of teaching after two decades of other pursuits in sailing education—now in another country—I was struck by how the themes and rewards remain the same. I was immediately eager to go through the learning process with these kids and also to join a group of impressively knowledgeable instructors. It’s refreshing to teach youth sailing again and, when I asked one of our youngsters recently how her school day was, she said with all honesty, “It’s much better now that I’m about to go sailing.” That right there is what it’s all about.

Takeaway: Be patient. To best achieve all of those positive and joyful learning experiences for young sailors and instructors alike, I learned quickly that it is important to exercise patience, and to keep a few things in mind about how we take instruction. Children have different learning styles and capabilities than adults, and that’s very evident in the sailing environment. By having patience with individual kids and even in group settings, everyone benefits.

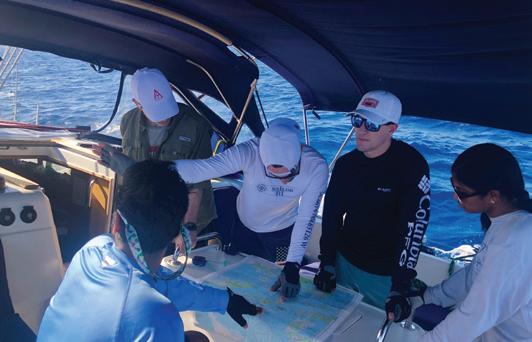

A fellow instructor goes through parts of the boat with attentive new students.

From teaching youth sailing, I got hired as a keelboat instructor at an international sailing school that was based in Florida. Now working full-time and year-round, the amount of information and on-the-job training was initially like drinking through a fire hose. But once I settled it and completed the instructor certification process, it all slowed down and the teaching part came natural to me.

No longer coaching from a RIB, I was now on the boat with the students conveying the finer points of sail trim, points of sail, docking, anchoring, yacht systems, and much more. I loved it. The biggest change with this new endeavor was that I was primarily teaching adults who were using their vacation time to come learn how to sail and cruise on 26-foot keelboats and then 40- to 50foot cruising boats. This meant I had to adapt my teaching style. And, still in my early twenties, I was usually quite a bit younger than my students and I’m sure more than a few were skeptical of my overall level of experience.

Undeterred, I worked my way up the ladder and soon found myself traveling to the Bahamas and Caribbean to teach, and then got navigation and passagemaking instructor certifications that allowed me to go deeper into the sailing curriculum and across bigger stretches of water. It was a blast, but it was a lot. After six mostly wonderful years of living that lifestyle, it was time to take a break. All teaching is hard work, but this style of education is particularly time intensive—I was spending over 250 days a year on the water and needed a change. Also, my burgeoning writing career was providing new opportunities, and I wanted to focus more on that and on possibly starting a family.

Top of their class Navy sailors were quick to learn sail trim and points of sail.

It was the decision to step away from this teaching environment that turned me towards Seattle. I got hired at Windworks Sailing School, where I taught on the weekends, and went to the University of Washington during the week to get my Certificate in Editing. Also in that time span, my wife Jill and I bought our beloved Grand Soleil 39, named her Yahtzee, and moved to Shilshole Bay Marina. Soon after, we welcomed our first son, Porter, then our second, Magnus, and took off cruising. I feel like our family’s adventures started the day I taught that first keelboat class all those years prior.

Takeaway: Get immersed. Knowledge comes from experience, and expertise comes from long-term immersive experiences. When I first started teaching on keelboats and cruising boats, I was all in. Being in my early twenties, a rigorous schedule was ok with me and I was up early, home late, and sometimes gone for a week or more at a time. I knew that all the time and hard work that I was putting in would be worth it in the long run. The effort I expended was almost as valuable as the experience I gained, and in the end, it all led me to a lifestyle that I get to share with others… especially my family.

Along with teaching broader sailing and cruising skills, I was also coaching racing and honing my craft on the race course. I grew up racing dinghies and then went on to keelboats, but when I was first pressed into service as a racing coach, it was a bit intimidating. Being young, it didn’t quite feel like I was ready for that step and yet, I would jump at every opportunity that came my way.

Racing is a love language for the author, especially one-design in a solid breeze.

As with most things, the more I got into it, the more I learned from those around me and the results followed. I came to understand and enjoy the nuances of my role as a coach of a race team and how to teach starting, tactics and strategy, upwind and downwind trim, mark roundings, and so much more. Again, it was one of those parts of sailing that the more you do it, the more you get comfortable with a variety of racing situations, student and crew dynamics, wind and sea states, and modes in which the boat needs to be sailing in order to be successful.

I still take almost every coaching opportunity that I am able to, and even though it was the hardest and most intimidating thing to teach at first, I’ve found that I love it the most because it’s incredibly rewarding to watch students put their skills into practice on the race course and succeed.

Takeaway: Lean in to what is uncomfortable. My initial nerves around teaching race crews stemmed from a lack of experience in that environment. Yes, I knew how to race sailboats, but doing and teaching are not the same. And it’s a different thing entirely to step on a boat with a full crew and coach them through a day or a week of racing. I was fortunate to have mentors who helped me along the way and, even when it seemed like I was in over my head, I pushed through and came out more confident on the other side.

One of my latest part-time endeavors has been teaching recently-graduated officers of the United States Naval Academy how to sail, and then how they could teach the incoming freshman class. If there’s one thing about the Naval Academy, it’s how they build conformity and continuity into teaching sailing.

At Navy, teaching the Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) is the only way. End of discussion. No wiggle room. I knew right away that my freewheeling Caribbean attitude of having fun most of the time while teaching wasn’t going to cut it. While we did have fun sailing at Navy, it was structured in a way where I was having nearly as much of a learning experience as the young officers.

The other civilian instructors were incredibly well versed in the culture of the SOP world and I was a quick study in how to follow the step-by-step organization of this style of teaching on a sailboat. We taught the officers on Navy 26 keelboats and the days were long and hot, but rewarding. We put them through all the normal keelboat skills and it was incredible how fast they

could complete skills checklists. There was a reason why they’d graduated from the Naval Academy.

By the end of the three weeks, the core group of instructors had moved from onboard teaching to coaching from Navy RIBs. We put the sailors through tacking and jibing drills, and even had them racing each other during the final few days of their certification. Navy was a different world, but boy was it gratifying to walk away with a smile on my face after completing that gig.

Takeaway: Be open to new experiences. I’ll admit, when I accepted the job at Navy and walked into the Academy in Annapolis, I didn’t know what to expect—not unlike so many of my students over the years. I had absolutely zero experience in the military world and it probably showed when I came in wearing flip flops and an untucked shirt. Fortunely, I was eager to teach and learn, and in doing so I connected with my fellow instructors and students. And by being willing to try something new and different, I can now count that experience as one of my favorites in all my time teaching sailing.

Looking back on the past two decades of being a sailing instructor brings up a lot of fond memories of fun people I’ve met, sailed and worked with, and amazing places where jobs have taken me. I’ve watched kids go from zero sailing experience to being able to take boats out on their own. Race crews have gone from completely green to being competitive and even winning on the race course. And learn to sail students have blossomed into cruisers who then went on to charter or own their own boats.

I’m proud to have been part of moments like those and continue to push myself to be a better coach and teacher to help new sailors or those who want to grow their skills. Now, looking towards the horizon, I feel more open than ever to what lies ahead. Like I tell my students, just keep working hard and putting yourself in a position to succeed… and you will.

Andy Cross is the editor of 48° North. After years cruising the Pacific Northwest and Alaska with his family aboard their Grand Soleil 39, Yahtzee, they sailed south and are currently in the islands of the Eastern Caribbean.

by Mark Aberle

It all began with a logistical challenge: how could my partner Leigh and I return from the Gulf Islands to the San Juans without my boat, and still have fun doing it?

I had loaned my Maple Leaf 42, Cambria, to my Canadian Race to Alaska teammates for the summer. Getting the boat across the border to them was straightforward, but returning to the U.S. side after the dropoff was another story. With the ferry route between Sidney and Anacortes no longer available, what used to be a simple hop had become much more complicated.