Use the off-season to get running rigging-ready Winter is the ideal time to inspect and replace aging lines—before schedules tighten and launch season begins. Samson ropes deliver the strength, handling, and durability trusted by serious sailors for every application.

From halyards to sheets, Samson’s high-performance lines provide the reliability and control you need for safe, confident sailing. Options include WarpSpeed 3 SD, with ultra-low stretch and SamsonDry® coating for offshore use; AmSteel®-Blue, a lightweight Dyneema® line built for high-load halyards and tacks; MLX3, a versatile, strippable line ideal for performance cruising and club racing; and Validator-12, a 100% Vectran® control line offering nocreep precision.

Now’s the time to upgrade and prepare for the next season with lines you can trust.

I am fortunate to be connected with the full array of ways to approach boat life, and am moved and humbled by the whole wonderful lot. I particularly admire those doing versions of family life afloat far more ambitiously than I am. My two kiddos keep my dad-pride meter in the red, but compared to some I know, they’re hardly being raised as boat kids... yet.

It’s with that context that I share this: I brought our three-year-old, Rowan, sailing for the first time in the last month. She’s been out on boats a number of times, but part of me is sheepish to admit that she hasn’t already done what I know some other kids have at her age. Most of me, though, is positively bursting with joy and gratitude and awe (and relief) to have seen how she thrived. She did so great! (And yes, that’s her on the cover.)

I’m so thankful to my longtime sailing pal, Dave, who welcomed Rowan and me aboard his J/109 Spyhop, and to the half-dozen other sailing friends who accommodated Rowan’s every desire on the boat while simultaneously supplementing my efforts to keep her safe with their own attentive eyes and helping hands. It blew in the teens and the late-September sun kept it pleasantly warm. We flew the spinnaker. Rowan got to drive the boat each time she asked, she never showed any fear, and she was entirely engaged with her surroundings. I am beyond proud.

I could fill volumes gushing about how it all made me feel—it was a really big dad day. But the better question is: “How did she feel?” She’s brilliant, but not a very compelling interview just yet. Rowan, did you like sailing? “Yeah.” What did you like about it? “I liked the sailing.” Do you want to go sailing with Dad again? “Yeah.” I’ll take it.

Short of her telling us how she felt, here are a few observations and hypotheses.

• Rowan’s first interest was the interior of the boat. She quickly turned it into her playhouse, even as it tipped 20-degrees sideways in a puff—sea bags tumbling all over the place were just new obstacles to climb on and over.

• On deck, she did want to steer… frequently. Luckily, our sail had no stakes other than a happy day on the water among friends, so she probably drove six or eight times. Holding a course wasn’t in her skillset yet, but I think her access to the wheel helped her feel like she could do whatever she liked on the boat that was safe for her to do.

• Speaking of safe, I do think she felt safe and, importantly, unafraid. Her over-cautious dad wasn’t at ease 100% of the time, but I think the whole crew was a helpful blend of very relaxed about the actual use of the boat in those conditions and generally Rowan-oriented enough that I believe she felt comfortable at all times.

• Rowan was fascinated by the water. Whether sitting legs out like a few of our fellow crew or laying belly-down on the deck to hang her head over the side and watching the water go by, frothing waves and wakes were constantly captivating entertainment.

• At the risk of cringey self-congratulations, the best thing I did for her that day was choose a sailing situation with people I trust and in which I had zero sailing responsibility. I was there for her and nothing else. And I think and hope that made her feel like she and I were truly sharing the experience together.

I consider the success of this first sail more good luck than good strategy. Of course, I’ve shared this story with many people, and one of them—my friend and renowned sailing coach, Ron Rosenberg—heard my description and offered his advice for sailing parents: “For young kids, there’s only one rule: no bad experiences.” I’m confident Rowan and I would both agree: mission accomplished on the maiden voyage. Here’s hoping we keep that trend going!

I'll see you on the water,

Joe Cline Managing Editor, 48° North

Volume XLV, Number 4, November 2025

(206) 789-7350

info@48north.com | www.48north.com

Publisher Northwest Maritime

Managing Editor Joe Cline joe@48north.com

Editor Andy Cross andy@48north.com

Designer Rainier Powers rainier@48north.com

Advertising Sales Ryan Carson ryan@48north.com

Classifieds classads48@48north.com

48° North is published as a project of Northwest Maritime in Port Townsend, WA – a 501(c)3 non-profit organization whose mission is to engage and educate people of all generations in traditional and contemporary maritime life, in a spirit of adventure and discovery.

Northwest Maritime Center: 431 Water St, Port Townsend, WA 98368 (360) 385-3628

48° North encourages letters, photographs, manuscripts, burgees, and bribes. Emailed manuscripts and high quality digital images are best!

We are not responsible for unsolicited materials. Articles express the author’s thoughts and may not reflect the opinions of the magazine. Reprinting in whole or part is expressly forbidden except by permission from the editor.

SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS FOR 2025

$39/Year For The Magazine

$100/Year For Premium (perks!) www.48north.com/subscribe for details.

Prices vary for international or first class. 48º North

Proud members:

48° North has been published by the nonprofit Northwest Maritime since 2018. We are continually amazed and inspired by the important work of our colleagues and organization, and dedicate these pages to sharing more about these activities with you.

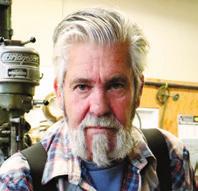

When I sat down with Jared, a 17-year-old senior at Port Townsend High School, I was struck right away by how confidently he spoke about his summer job. For most teenagers, earning money might mean bussing tables or scooping ice cream, but he chose something entirely different: working in a foundry.

Jared’s connection to the maritime world began just last year when, as a junior, he joined the Port Townsend Maritime Academy (PTMA)—a free half-day program that provides juniors and seniors with the opportunity to gain maritime experience, skills, and certifications while exploring different maritime careers.

Having recently moved from Oklahoma, Washington’s maritime industry was completely new to him. “I wanted to give it a try,” he explained. “I wanted to look at careers I might like around the port, and PTMA seemed like a good way in.” It didn’t take long for him to find his footing. Now in his second year at PTMA, Jared has already shown how easy and rewarding it can be to apply what he’s learned in the classroom in a real world setting.

When he decided he didn’t want another restaurant job, Jared reached out to Chrissy McLean, Northwest Maritime’s Career Launch Program Manager, about summer opportunities. One of the options on the list was at Port Townsend Foundry, where world-renowned Pete Langley was looking for help. Jared did some YouTube research, thought the work looked “really cool,” and soon found himself in an interview. “Pete hired me on the spot,” Jared said with a grin. A few days later, he was clocking in. Langley sees mentorship as an essential part of the Foundry’s work. “Trying to help people experience what the trades and industry are like is really important,” he said. “For Jared, or any of the young people working here, it’s an opportunity to see how the industry works and think about what a pathway forward might look like. Having a positive attitude, the ability to take direction, and the willingness to learn what’s necessary to be successful are all very important. He also contributes to a positive working environment. Experiences like this can lead to lots of opportunities down the road, whether that’s here or anywhere else.”

Like the work itself, Port Townsend Foundry is steeped in history. First established in 1883, it was revived in the 1980s by

Langley and continues to produce high-quality marine hardware while maintaining a vast library of wooden patterns, some of which are more than a century old. For Jared, that legacy isn’t abstract— it’s the parts he helps make every day.

Because he’s 17, there were certain limits to what he could do, but Jared took on real responsibility. He started in the molding room, learning from coworker Gabe, who walked him through each step. “By my second day, I was already making molds,” Jared said. These molds form ship and sailboat parts— everything from goosenecks to shredders to fittings that keep lines in place. He’s also done some finishing work by grinding and sandblasting.

The most dramatic part of the job—pouring molten metal—is left to seasoned veterans. Still, Jared has been part of the action, helping pull the lines during pours and learning the sequence: pour, wait, crack open the mold, break the sand, aerate it, and prepare for the next casting.

“It’s all been really cool,” Jared reflected. “I didn’t know anything at all about what a foundry was, but I have loved learning. Everything has a purpose.”

His experience at PTMA has not only prepared him, but also shaped him. He admitted he once thought maritime workers were “kind of grouchy and crusty,” but quickly realized how wrong he was. “The instructors are really nice, and they love their jobs,” he said. One of his highlights was the sailing unit: “I thought sailing was boring and simple, but once we got on the water, pulling the lines and setting the sails—it was really fun. All the elements working together was great.”

As for the future, Jared is keeping his options open but knows it will involve working with his hands. Carpentry, marine electrical, or other maritime trades are on his list. Trade school is the next step. “I love wood,” he said, “but I also really want to stick with maritime.”

Watching him talk about the foundry, it’s clear this summer job has been more than just a paycheck. For Jared, it’s been a launching point—one that’s reinforcing a future in the maritime trades and beyond.

- Anika Colvin, Northwest Maritime Communications Director » nwmaritime.org

In Anacortes, winter shines as brightly on the water as it does downtown. Each December, yacht owners and boaters of every kind join in the celebrated LIGHTED BOAT PARADE, a dazzling procession across the harbor that crowns the season.

Enjoy ANACORTES COASTAL CHRISTMAS festivities, from a waterfront tree lighting to festive markets and caroling, Anacortes o ers a uniquely maritime holiday experience where luxury, community, and nautical tradition converge.

Year-round, Anacortes is equally inviting, with summer’s Waterfront Festival in June o ering free boat rides and maritime exhibits, and local yacht clubs hosting races and cruising events. Whale-watching, shing charters, sailing lessons, and easy access to the San Juan Islands keep the waters lively in every season, ensuring that whether by yacht, charter, or kayak, there’s always a reason to set sail from Anacortes.

After careful review of escalating safety issues at Salmon Bay Marina on the south side of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, the Port of Seattle made the decision to terminate all moorage agreements and close docks A, B, and C no later than March 18, 2026.

A comprehensive engineering review by the Port of Seattle, with additional expert guidance from outside engineering firms, has concluded that several dock elements including the roofs, connections, and underwater pilings pose a distinct and imminent safety risk to customers, employees, and the moored vessels. The safety and security of the marina community is the Port of Seattle’s highest priority, and docks A, B, and C can no longer be maintained to an acceptable level of safety and must be vacated.

All affected customers have been notified. Port of Seattle has assigned a dedicated team to support Salmon Bay Marina

The Southern Sound Series is the centerpiece of offseason racing calendars around Puget Sound. The one-race-per-month series draws big fleets of hardy winter sailors, and is a great display of just how fun and rewarding it can be to get out sailing in challenging conditions.

The South Sound Series Committee recently met and confirmed the traditional race dates.

• December 6, 2025 - Winter Vashon

• January 3, 2026 - Duwamish Head

• February 14, 2026 - Toliva Shoal

• March 14, 2026 - Islands Race

The series retains its customary structure in which each race is hosted by a different South Sound yacht club, but there is a central website for the series hosted by the South Sound Sailing Society that will be updated as each club provides details for their individual race.

» ssseries.org

customers in answering questions and facilitating contact with other marinas, working with customers to assign exit dates, ensuring completion of paperwork, and properly closing moorage accounts. This person also is prioritizing reaching out to those with liveaboard status due to the additional challenges posed by the closure of docks A, B, and C.

A detailed plan for docks A, B, and C, as well as the overall Salmon Bay Marina, has not yet been fully determined by Port of Seattle leadership and Port Commission. Currently, there is no plan to repair or reopen the impacted docks.

» www.portseattle.org/maritime/salmon-bay-marina

A concerned reader contacted 48° North and estimated that 150 boats will be displaced by this closure. Boaters and residents have created a petition urging the Port of Seattle to reconsider. www.change.org/p/save-salmon-bay-marina

Portland Yacht Club (Pacific NW Offshore’s new Organizing Authority, or OA), Corinthian Yacht Club of Portland (the founding club and outgoing OA), and the title sponsor, Schooner Creek Boat Works, invite sailors around the region to celebrate an extraordinary offshore racing event that has been 50 years in the making.

This race offers:

• Two classes: ORC (Racing) and PHRF (Cruising)

• Two experiences: The open Pacific Ocean and the challenging Strait of Juan de Fuca

• Two countries: The United States and Canada.

The Pacific NW Offshore race hits a sweet spot for yacht racers. It is a true offshore experience that starts near the mouth of the Columbia River (a stone’s throw from its host city of Ilwaco, WA), follows Washington’s Pacific coastline, rounds Cape Flattery to enter the Strait of Juan de Fuca, then blasts down the Strait toward Race Passage to finish just outside the entrance to Victoria Harbour, British Columbia.

The organizers hope to draw 50 participating boats for this 50th anniversary race.

» www.pacificnwoffshore.org

The Annapolis Sailboat Show’s reputation precedes it. I’ve been hearing about it for more than a decade. My co-editor Andy Cross has been there quite a few times and has shared his experience with 48° North readers, and I felt the FOMO. This year, the stars aligned for 48° North to have a couple of representatives attend, and we knew we were in for a treat. It’s the largest sailboat show on this continent, and is a comprehensive collection of the nation’s sailing industry, and many of the global players are there, too. And its sailing industry scale is almost incomprehensible for anyone whose boat show expectations have been built in the Pacific Northwest. Weeks later, my head is still spinning with positivity, inspiration, and invigoration (no longer from product-testing the famous Painkiller cocktail). Reflecting on it, I wanted to share some observations with 48° North readers.

Any boat show story necessarily leads with the boats. They’re kind of the point, but whoa, there were too many sailboats to see. It was incredibly cool to check-out the full line-ups from the big manufacturers like Jeanneau, Beneteau, J/Boats, and more, whereas at shows in our region we might only see a small portion of their lines. It was also thrilling to climb aboard boats I’d heard of but hadn’t seen in person yet, like the Excess 13, the Beneteau 30, and the J/36. But perhaps most eye-opening were the boats I hadn’t even heard of, and was very impressed by, including the Pegasus 50, the Zonda Z28, the aluminum centerboarder Ovne 370, or the Hylas 57. I could go on and on. So many sailboats. So little time. So much fun.

Part of what was so fun about experiencing the Annapolis show was its injection of sheer excitement and positivity, and the reminder that this many people love sailing. As I mentioned, there were so, so many boats. And there were lines to get aboard nearly all of them, sometimes very long ones, throughout the day. People who think sailing is amazing and

devote a lifetime’s ration of hours and dollars to it are part of a special community, but this show really highlighted how much bigger that community is than we sometimes think.

There was also such a refreshing reminder of the tightknit sailing industry’s commitment to one another. A number of factors temper the industry’s optimism, from workforce challenges to some complicated trends in the national and global economy, but the collective resolve and enthusiasm endures. It was an oft-heard refrain, but it’s one I believe is genuine—sailing businesses aren’t just doing a good job and out for themselves, there is an active culture of supporting one another and sailing at large. Such spirit is what rising tides are all about.

THERE WERE A SURPRISING NUMBER OF PACIFIC NORTHWEST FRIENDS REPRESENTING

It was more on the industry side than the attendees from what I saw, but there was a ton of Pacific Northwest presence at this show, in spite of its location on the other coast. And that was true from the very beginning.

It started with a shoutout about the awesomeness of our region’s booming J/Pod of J/70s at the Harken Press Conference in the opening minutes of the show, and continued with a CEO of a major international catamaran manufacturer telling me that the Pacific Northwest is definitely the part of the United States where he wants to go cruising before trying anywhere else—the PNW love was in full force around Annapolis. I stayed with 48° North columnists Julie and Gio Cappelli (Necessary or Nice), who are so in demand as instructors that they’re brought out from Anacortes to teach multiple days as a part of the show’s Cruiser’s University.

It’s part of why we were there, but in booth after booth, we found friends and colleagues from our region. Boat shows are often described as reunions, and for a first-time Annapolis attendee the extent to which that was true was a little surprising. From boat sales to marine equipment, from charter companies to education, the PNW shows up for the Annapolis show in a big way, and it’s really great to see.

For all these reasons and more, I can make a strong and enthusiastic recommendation that a visit to the Annapolis Sailboat Show is worth it.

- Joe Cline, Managing Editor, 48° North » www.annapolisboatshows.com/sailboat-show/

Brandon Baker will be well known to many in the marine industry. He's been a mover and shaker in his tenures at Elliott Bay Marina and Port of Edmonds. A bright and energetic person, Brandon's contributions to the boating community have taken many forms.

Brandon has long running connections to 48° North, having served for many years on the Northwest Marine Trade Association's Grow Boating Committee alongside Managing Editor Joe Cline, and has been a creative thought-partner about everything from boating accessibility to marine media on numerous occasions. Brandon's ascension to Executive Director surely makes him one of the youngest port executives in Puget Sound and a key part of the next generation of leadership in the industry.

The Port of Edmonds Commission is pleased to announce the appointment of Brandon Baker as the new Executive Director, effective immediately.

Baker joined the Port of Edmonds in 2020 as Marina Manager and progressed steadily through leadership roles—becoming Director of Marina Operations in 2022 and Deputy Executive Director in 2023. He has served as Acting Executive Director

since May, following the departure of former Executive Director Angela Harris.

Prior to joining the Port, Baker served as Marina Manager and Director of Marketing at Elliott Bay Marina in Seattle, where he played a key role in customer engagement and waterfront events. He holds several industry certifications, including Clean and Resilient Marina Professional, Advanced Marina Management, and Intermediate Marina Management—all awarded by the Association of Marina Industries.

“Brandon brings an exceptional depth of marina knowledge and a steady, proven leadership style that has earned the respect of our staff and community,” said Commission President David Preston. “His dedicated service and success as Deputy Executive Director have prepared him well to lead the Port of Edmonds into its next chapter.”

Baker’s appointment reflects the Commission’s commitment to sustaining momentum across the Port’s strategic priorities— including environmental stewardship, public access, and regional economic vitality.

» portofedmonds.gov

Response to Voltage Sensing Relays Necessary or Nice Column from the October 2025 issue

Dear Joe,

I’m a decades long reader of 48° North and enjoy every issue. Also, my father, Ed von Wolffersdorff, wrote the Racing Rules Column for 20+ years for your magazine.

Become a part of the 48° North crew! In addition to your magazine each month, with this exciting new subscription offering, you’ll also be supporting 48° North in a more meaningful way. But, warmed cockles are far from the only benefit. Others include:

• Annual subscription to 48° North delivered to your door.

• Two 3-day pass to Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival ($110 value)

• Northwest Maritime Center Member decal

• 10% discount on most items in the Welcome Center

• $100/year (additional fees for First Class forwarding or International)

Our standard subscription gets you 12 months of 48° North and its associated special publications (SARC, Setting Sail, and the Official R2AK Program).

• $39/year (additional fees for First Class forwarding or International)

I’m writing to address one disadvantage of the voltage sensing relays, also known as ACR’s (automatic charging or combining relays) that Gio and Julie Cappelli recommend in their column in the October issue. Nigel Calder in his Boatowner’s Mechanical and Electrical Manual, Fourth Edition, addresses the disadvantage of ACRs on page 53 where he discusses the pros and cons of the various electrical devices used to combine house banks and starting batteries for charging purposes.

The disadvantage of ACRs stems from the fact that house banks are deep cycle batteries and starting batteries are cranking batteries. The key difference is that house banks are typically deeply discharged, which requires a different charging regimen from a starting battery that is minimally discharged. As Nigel explains, the disadvantage of ACRs is that “once battery banks are paralleled, the batteries in both banks will be charged according to the same charging regimen. But different kinds of batteries are commonly used for house service and cranking service....These batteries accept charges in different ways. When charged in parallel, one bank will invariably be somewhat overcharged, while the other will be somewhat undercharged, resulting in a reduced life expectancy for all the batteries.”

The solution to this problem is what’s known as a “batteryto-battery” charger, also known as a DC-to-DC charger, an example being the Victron Orion-Tr Smart Isolated DC-DC (1212 18A) charger that is installed between our house bank and our starting battery on our 1969 Grand Banks 32, Athena. The charge that the Victron produces is programmable, meaning that your starting battery will receive a charge that is tailormade for your starting battery, completely separate from the charge that your house bank receives.

Additionally, the Victron is programmable on your smartphone and can be monitored on your smartphone while underway. The Victron sells for approximately $160, which is just slightly higher than an ACR.

Keep up the good work, Joe!

Most sincerely, David von Wolffersdorff

Response to David’s Question from Julie and Gio:

Hi David, and thanks for your note,

We have had the privilege of spending quite a bit of time with Nigel Calder at various boat shows over the years, and worked with Nigel and Jan during their production of BoatHowTo. There’s no doubt he’s one of the most knowledgeable minds in the marine electrical world. We often say, Nigel has likely

forgotten more about boat systems than most of us will ever know.

As with most things on boats, there’s rarely a single “right” answer. There are often several workable solutions depending on the vessel, its systems, their configuration and the owner’s goals. The most important thing is a thorough understanding how your system functions as a whole and making choices that best fit its design and usage.

It’s true, as Nigel notes, that combining battery banks of different chemistries or states of charge can lead to imperfect charging. That’s why in our article we emphasized a key caveat: All batteries that will be paralleled by an ACR should share similar chemistry, age, and charging profiles. When that’s the case, an ACR offers a simple, elegant, and reliable solution for automatic charge distribution across banks without the need for manual switching.

For many boaters, replacing the old “1-2-Both” switch with a Blue Sea ACR provides an affordable and highly effective upgrade that plays nicely with most existing charging systems, provided those systems are functioning properly.

A DC-to-DC charger, such as the Victron Orion-Tr Smart Isolated mentioned, can indeed be a great choice for some installations. To a large extent when batteries of dissimilar types or charging needs must be kept isolated. However, these devices require careful programming to ensure correct voltage and current limits for both the source and target batteries. Installation and configuration should always be handled by someone with professional training and a solid understanding of the boat’s entire electrical system.

It’s also important to note that isolated versions of DCto-DC chargers are only appropriate when there’s a specific reason for battery banks not to share a common ground, a design element that is uncommon on most small recreational vessels. Selecting the wrong type (isolated vs. non-isolated) can cause unintended electrical issues.

Ultimately, as in so many areas of boat ownership, it depends. Every vessel’s electrical system is unique, and the “best” charging strategy will vary. For example, on our own boat Sea Fox, we’ve been using a Blue Sea ACR since 2019 with a Lifeline GPL 4DL house bank (630 Ah) and a dedicated GPL 2700T starting battery. Even after six years of service relying on three independent charging sources, the batteries continue to perform excellently—proof that when installed correctly in a compatible system, an ACR can be both dependable and efficient.

We appreciate the opportunity for this discussion, and we’re glad to see readers engaging deeply with how to best care for their electrical systems. Whether you choose an ACR, a DC-to-DC charger, or another method entirely, what matters most is ensuring that the system is properly designed, safely installed, and fully understood.

Fair winds,

Gio and Julie Cappelli

by Bryan Henry

Japanese scientists have isolated more than 3,000 pharmaceutically active substances from marine animals and plants.

More than 15,000 chemicals have been discovered in ocean organisms in the past 30 years.

Ecteinascidin, sold under the name of Yondelis and used in cancer treatment, derived from a sea squirt.

In the 1980s, researchers used compounds from a marine sponge to produce AZT, the first drug effective against HIV/AIDS.

Extracts of certain sponges yield antibiotic substances.

Some corals produce antimicrobial compounds, and the sea anemone provides a cardiac stimulant.

1 Directly in front, 2 words

7 Cutting tool

9 Long John Silver was missing one

10 Wearing away on a rope

11 In a position (of a sail) where the wind is pushing against the forward side, tending to push the boat backwards

13 Get better as a Pinot

14 Central section of a vessel

16 Moistureless

20 Roadside lodging establishments

21 Navigation using visible landmarks

22 Sound made to request silence

23 The current’s direction

24 Adjusts the sails

25 Sighting device on a ship for taking the relative bearings of a distant object

26 Prefix meaning environmental

28 Raleigh’s state, abbr.

30 Polite address

31 Like many beaches

32 Ropes supporting a mast fore and aft

1 Takes a naval vessel out of service

2 Order from the captain to leave the vessel immediately, 2 words

3 Burning

4 Female chicken

5 Breakfast staple

6 Water’s resistance to a vessel’s movement

7 The Caribbean, for one

8 Trail left by a moving ship

12 Sleeping need

13 Top grades

15 Rope attached to the bow of a dinghy

17 State of being prepared

18 Water body between the UK and Scandinavia, 2 words

19 Shore toward which the wind is blowing

23 Briny

27 Roman numeral for 101

29 Golden State that enjoys the Pacific coast, abbr.

» See solution on page 52

Zorivax, used to combat herpes infections, is derived from the extract of a sponge.

A muscle relaxant has been isolated from the snail Murex.

Extracts of abalone and oyster act as antibacterial agents.

Cone shell toxins have been used since 2004 in the production of ziconotide, or Prialt, a painkiller 100 times more powerful than morphine.

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) was originally made from dried kelp.

Algin is extracted from brown algae, and agar and carrageenan are obtained from red algae.

Algin derivatives are used as stabilizers in dairy products and candies as well as in cosmetics, inks and paints. Agar is used as a medium for bacterial culture in laboratories and hospitals, and serves as an ingredient in desserts and in pharmaceutical products.

Carrageenan is a stabilizer and emulsifier used to prevent separation in ice creams, salad dressings, soups, puddings, cosmetics and medicines.

The three varieties of seaweeds—brown, green and red—are not actually related.

Building on the proven design of the Meris Waterproof Bibs, Mustang Survival’s new Meris Waterproof Salopette offers a relaxed fit with reduced bulk for unrestricted movement. Whether you’re grinding winches, scrambling across the deck, or bracing against heavy seas, you’ll be able to get the job done in comfort in a coastal or offshore environment. A two-way waterproof YKK AQUASEAL® zipper ensures full coverage and keeps weight to a minimum, while adjustable knees, waist, and hem provide a tailored fit. Removable lightweight knee pads absorb impact on unforgiving decks, double thigh pockets feature a clear window section for notes and a tool tie-in point, and there is extra space with a zippered chest pocket and two dump pockets. The salopette is available in an extended size range for men and women from XS to XXL, making it a top choice for a wider range of users.

Price: $649.99 » www.mustangsurvival.com

Weems & Plath recently announced the launch of the newest addition to its OGM Series of LED Navigation Lights: the LX Steaming/Deck Light. Purpose-built for marine environments and designed with the needs of sailors and power boaters in mind, this unique combination light offers versatility, ruggedness, and long-lasting performance. The light combines Weems & Plath’s ocean-proven LX Steaming/ Masthead LED Navigation Light with a dual-color deck light that lets you switch between red or white deck illumination. This feature gives sailors the option to have either a red deck light to preserve night vision and reduce glare, or a white light to help illuminate the deck for detailed work. The housing and mounting wings are made from solid aluminum and have been hard-coated with military-spec anodization to ensure they withstand the harshest ocean environments. The sealed UV-resistant acrylic lenses help protect the powerful LEDs that provide over 100,000 hours of brightness. The light is USCG, ABYC, and COLREGS certified and exceeds 3 miles of visibility, making it ideal for sailboats and power boats under 65 feet.

Price: $779.99 » www.weems-plath.com

The Sailrite HandyPress is an innovative table-mounted hand press that makes it easy to install snaps, grommets, and buttons for all your marine, canvas, upholstery, leather, banner and hobby projects. The kit includes six adapters that are designed specifically for the HandyPress, and are compatible with other hand-press dies on the market. You can also use your existing Sailrite dies and dies from other popular brands, or choose from nearly 100 other dies and accessories to get any project completed. Constructed of durable metal and finely machined parts, the press requires 25% to 33% less arm strength compared to similar tools, so you can get more done with less effort, reducing fatigue and strain on your body.

Price: $499.95 » www.sailrite.com

by Dennis Bottemiller

Happily, we pulled our C-Dory 22 Cruiser Sea Lab out of our Fair Harbor slip and onto her trailer for a good cleanup and a few repairs before our three weeks of late summer cruising. I really wanted the windlass to work before we left, the trim tabs were being wonky, and the bottom was a bit furry.

For some reason, the windlass stopped working last summer. Once you’ve had a taste of that system’s convenience, it’s really hard to go without it. Electrical power was getting to the unit, but it seemed somehow frozen up; so once Sea Lab was out of the water, I was determined to pull it off the boat, take it apart, and see what the problem was. As it goes, the modern way to initiate this kind of procedure is to watch YouTube videos. It’s a plan that has gotten me into trouble before, but I’m too stubborn and frugal to immediately recruit the assistance of a professional shop. So, on the bench it goes.

As I pulled out the housing screws, I kept thinking to myself, “A new one is $1,400, don’t screw it up.” In the video, the housing halves separate easily,

and nothing flies out of the inside on springs. In reality, one of the drive gears is pressed into a fitting on one half of the housing, and it’s tight and doesn’t just slide off. There’s probably a special tool for pulling this off, but I didn’t have one, so two long screwdrivers would have to suffice—and they did. I was pleased to see I apparently avoided damaging anything except the irreplaceable gasket between the housing halves, but boy are there a lot of gears in there.

Not finding anything visibly out of place, I pondered the next question… does the motor work? I found and stripped the ends of some trailer wire for test leads and carefully carried the half of the windlass, with all the stuff in it, out to the boat battery. After removing the first drive gear, I touched the wires to their terminals and the motor jumped to life. Great, it’s not burned out. Next, I put the drive gear back in and re-tested it with power and, sure enough, the whole thing drives and appears to be working. The thing itself is not the problem.

Back at the bench, I cleaned up the inside of the housings, redistributed the

grease, and made a nice new gasket seal with 3M 4000. After aligning, pressing, and bolting the halves back together, I rebedded the assembly onto the bow of the boat. To my disappointment, I pushed the button and all I got was a click. I already checked power from the relay to the connection and the spade connections looked clean and shiny, but there was nothing else it could be. So following another trip to town to buy some terminals and replace all four… Voila! It worked.

These are the kinds of things I love, and hate. Climbing through the selfdoubt and worry when learning to do something that might ultimately misfire and cost a lot of money or cause me grief; but if I manage to succeed, the feelings of triumph and self-reliance make it worthwhile. With that task accomplished, the rest of it seemed easy and almost fun.

Once Sea Lab was ready in the driveway, we loaded on all our gear and supplies for three weeks—not having to cart everything down the dock seemed like a bonus. We pulled out of the driveway, boat in tow, and drove the mile and a half back to the marina and ramp launched before motoring around to our slip. We waited for the next morning to begin our summer journey.

Our plan was to rendezvous with our friends, Rob and Tracy on their Sea Ray 23 Blue Pearl at Blake Island and formulate a plan to head north into the Gulf Islands. The Blue Pearl crew had not boated across the border into Canada before, and there were a couple of places we really wanted to take them. They had 10 days, we had

21, so we raced up to the border and checked in without too much difficulty. Both boats called into Canadian Customs on the snazzy app, and they cleared Blue Pearl but told Sea Lab we had to check in at the dock at the South Pender station. We radioed BP and agreed to meet at the Poet’s Cove fuel dock.

After clearing in and topping up on fuel, we motored up the channel and through Pender Pass to head north to Winter Cove on the edge of the Strait of Georgia. We found it uncrowded and beautiful, and when I pushed the anchor

down button, the windlass did its job without complaint. Anchor set, the Blue Pearl sidled up, and we rafted for the night in calm weather and stunning surroundings.

The next morning’s plans were to push farther north to Conover Cove on Wallace Island, a place we had been to a few years ago, and wanted Rob and Tracy to see. We made the easy transit, and managed to get space on the float across the dock from each other with a picnic table in between—perfect for communal meal prep. Tied up and settled in, we hit the hiking trails to the south end for some great views and maritime forest scenery. All four of us are connected to garden and tree work, and are tuned-in to the landscapes surrounding us, and we all found this particular forest very interesting. One tree that was especially fascinating to us was the western yew, Taxus brevifolia, which I had seen on a previous visit to the island. It is an uncommon tree and, in 1962, it was discovered to have a chemical compound in its bark that is highly suppressive to cancerous cells, and the compound was given the name Taxol, which is used in many types of cancer treatments and is on the World Health Organization’s list of Essential Medicines. We sighted numerous examples of this tree, and all of them were very old and large for their type. Western yew is a small tree that blends in with the forest making it difficult to spot, so what people generally think of as “large trees” does not fit with this species. The large specimens we found were of 18-20 inch trunk diameter

but were probably in the neighborhood of 200 years old.

We hiked and enjoyed Wallace Island for two days, and covered nearly all the trails on the island. The time slipped away and, before we knew it, it was time for the Blue Pearl to head home. We said our goodbyes, and Rob and Tracy headed south and we continued north.

Our next destination was Pirates Cove on DeCourcy Island, an anchorage we had chickened out on entering at low tide years ago in our Cal 27 Moondance We almost chickened out again as it was low tide when we arrived and there were three boats ahead of us waiting to enter through the narrow channel. Plus, from the outside, the inside looked quite crowded. We discussed going somewhere else for the night but decided that was silly as this was one of the places we wanted to see, and many people have told us how great it was. So we waited our turn.

Once in, we saw that there were three unoccupied stern tie chains just inside the entrance, and being in a very small and shallow draft boat we thought that would be fine for us. We had a 400foot roll of poly rope aboard just for this occasion, and we knew it would be another learning experience for us. In 25 years of boating, we had never stern tied before. I dropped and set the anchor with our trusty windlass, then we got one of the kayaks in the water and set the sterntie spool on a stick in Sea Lab’s rod holder. I hopped into the kayak and took the rope end to the chain, through a ring, and back to a stern cleat with an overhand loop knot. We tightened things up and were high-fiving each other on how easily and smoothly we accomplished the whole procedure, then settled in for a leisurely lunch and anchor watch. After a couple hours, we decided it was well-set—time for hiking. The trails were great, and Tim Tim the sailor dog was happy to be on dry

land, so we explored for several hours It was getting to be time for dinner, so we got back to the kayaks and loaded Tim in, and began to paddle back to Sea Lab As we approached, something about the boat looked odd and it dawned on me that it was not in the same place as when we left. Sea Lab was parallel to the reef rocks and very close. We both shifted into high paddling gear, and arrived to find that Sea Lab had pulled her anchor with the rising tide. Swinging on the stern line, the boat had drifted back toward the rocks and was almost aground.

We climbed aboard, looped the kayak painters onto an empty rod holder, and I started the motor, asking Tekla to keep all the lines out of the propeller. Looking over the transom in the crystal-clear water, I could see we were moments away from being stuck in the rocks. Then I was in gear, moving away from the reef and raising the anchor at the same time. We had to get the stern line off the chain,

so Tekla unhitched the end from the cleat and pulled it in from the other end, which was great until the knot from the overhand loop hit the chain… and stuck.

Meanwhile, during the rope shuffle the yellow kayak had somehow dismounted its hold and was 50 yards out the entrance and heading for the channel, but that had to be dealt with later. Around this time, we heard a shout asking if we needed help and we turned to see a man in his inflatable dinghy. “Yes, thank you!

Will you free the knot from the stern tie chain?” And he did so quickly.

We felt back in control. With the line aboard, we moved up the bay a little, farther away from the reef, and in two tries reset the anchor. That accomplished, I jumped into the blue kayak to reset the stern line while the nice man in his dinghy went out and rescued the yellow kayak. Whew! We got everything tied back together and the adrenaline began to fade, and we were both frazzled.

We settled down with mugs of boxed wine and talked about what would have happened if we had come back 10 minutes later. Well, we didn’t. We worked it out, and nothing broke and nobody got hurt. Indeed, after all of these years, we’re still learning.

Dennis, Tekla, and Tim Tim the sailor dog recently changed their home cruising waters from Tacoma to Case Inlet.

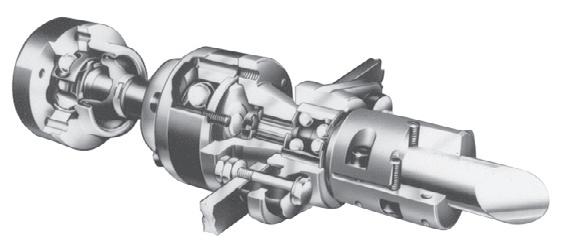

Business or Pleasure, AquaDrive will make your boat smoother, quieter and vibration free.

The AquaDrive system solves a problem nearly a century old; the fact that marine engines are installed on soft engine mounts and attached almost rigidly to the propeller shaft.

The very logic of AquaDrive is inescapable. An engine that is vibrating

on soft mounts needs total freedom of movement from its propshaft if noise and vibration are not to be transmitted to the hull. The AquaDrive provides just this freedom of movement. Tests proved that the AquaDrive with its softer engine mountings can reduce vibration by 95% and structure borne noise by 50% or more. For information, call Drivelines NW today.

Who is that?” I asked my husband Frank while on a mooring ball at Sucia Island. It was one of our first overnight trips in our 26-foot sailboat, and I was still learning how to sleep on board, surrounded by unfamiliar sounds and smells. Something was knocking into our hull very near my head, snarling and grunting, almost like a dog. I opened the bow hatch and peered out into the darkness. There I spotted multiple seals writhing and swirling in the water— behavior I had not witnessed during the day, when these creatures typically seemed calm and solitary. At the time I was not sure I wanted to know what they were up to, but later a biologist friend told me the creatures—likely harbor seals— might have been feeding and using my hull as shelter.

by Lisa Mighetto

A few months after the night of snarling seals at Sucia, Frank and I docked overnight for New Year’s at Boston Harbor in the South Sound. Tucked in our warm cabin and settling into a holiday brandy, we felt a jolt that sent our small boat rocking. We opened the hatch to find a lone seal flinging himself at our transom, trying to crawl into the cockpit. My first thought: “He must be rabid to behave so bizarrely and so close to me.” I grabbed the boat hook, thinking I might need to push him back. While the Marine Mammal Protection Act prohibits touching sea mammals, I knew I could not sleep with a crazy seal on board. As Frank and I pondered our options, we noticed a majestic spectacle in the distance: a pod of orcas, their unmistakable dorsal fins slicing through the water as they moved from

Budd Inlet to Dana Passage. Distracted, we didn’t notice what happened with the seal, who disappeared. Although it was unclear if the presence of orcas caused the seal to approach our vessel, he appeared terrified of the large predators once they arrived on the scene.

One of my favorite things about boating is watching wildlife dramas unfold. It is prudent and, in some cases, legally required, to keep a respectful distance, but I never found chasing marine creatures to be a satisfying pastime. In my experience, the best encounters come when you least expect them. I measure the success of our cruises by the numbers and varieties of marine animals sighted, and my logs include extensive bird lists.

Onboard guests appreciate viewing wildlife from my boat, and seals are a reliable favorite, often popping up alongside with only their heads and large, liquid eyes visible above the water. Porpoises—Dall’s and harbor—are also fun to spot, sometimes darting in and out of our bow wake like speed demons. And everyone seems to love river otters, creatures brimming with what I call a high “cuteness quotient.” Frank and I once watched a family of otters frolicking inside a sail cover on a neighbor’s boat, where they occasionally paused to peek out of an opening. “How adorable!” we gushed. Then we looked at each other, both realizing that these critters could easily do the same inside our sail cover and cockpit.

The Salish Sea’s unsurpassed scenery might seem sterile without wild creatures, who bring every cruising destination to life. Animals embody nature, making it tangible and accessible. Early conservationists understood this point, often including animals in their pleas to protect the natural world. Joseph Grinnell, an early twentieth-century scientist, for example, recognized the appeal of seeing creatures in the wild. “To the natural charm of the landscape they add the witchery of movement,” he explained [Science, “Animal Life as an Asset of National Parks,” Sept. 15, 1916]. Modern scientists similarly understand the public’s interest in encountering wildlife, particularly so-called “charismatic megafauna”—animals of large size and relatable personalities. Fortunately, such creatures are available to boaters in the Salish Sea, at least for now.

Frank and I have a friend who has seen many bears while cruising in British Columbia in his 26-foot Nordic Tug. “Your boat is your Land Rover safari vehicle,” he suggested. Once, on a quiet morning, he and his wife shut off their engine and drifted along the shore to watch a big male grizzly bear ambling down the beach. “We were so close we could hear his three-inch claws tap-tapping on the stones,” he remembered [Roderick Nash quoted in Don Douglass and Reanne Hemingway-Douglas,

Exploring the North Coast of British Columbia, 1997].

When Frank and I are underway in remote waters, we often scan the shore with binoculars, hoping to see a bear. Our conversations follow the same pattern. “Look, there’s one!” I’ll say. “Naw, that’s a rock,” will be his reply. We have had better luck with marine mammals.

Humans and killer whales have a complicated history. Coast Salish people have revered orcas for thousands of years, viewing them as powerful spiritual beings linked to the vitality of salmon runs. Early settlers described orcas, which are technically large dolphins, as inconvenient, dangerous fiends with sharp teeth. In 1904, for instance, wildlife conservationist William T. Hornaday called orcas “pirates” and “wolves” owing to their predatory behavior [An American Natural History]. His gruesome account, based on the observations of nineteenthcentury whalers, claimed that orcas hunt in “packs,” preying on larger whales by seizing their lips, eating their tongues, and

During the 1960s and 1970s, capture companies herded orcas in Puget Sound, hoping to export them to marine parks in other locations.

pulling them underwater. Fishermen sometimes shot orcas, which damaged nets and competed for salmon.

Beloved British Columbia author M. Wylie Blanchet similarly showed no fondness for orcas in The Curve of Time, which chronicled cruises in her 25-foot boat during the 1920s and 1930s. “The killers are savage things,” she wrote. “They normally hunt in packs.” She and her children witnessed several bloody attacks by orcas on grey whales, prompting a desire to avoid them. Even so, one summer day in Johnstone Strait orcas surrounded her boat. “We didn’t hear them coming,” she explained, “they were just suddenly there, on all sides of us— all just playing. There must have been about twenty of them— chasing, diving, ducking, and rolling with tremendous slaps of their tails.” Today, many mariners would welcome such an encounter. What a difference a few decades makes.

Orcas received an image makeover in the 1960s, when marine parks and aquariums began capturing them to entertain large crowds. Nearly 70 orcas were taken from the Salish Sea for display in places like SeaWorld in California, with around 48 identified as Southern Residents from Puget Sound. Killer whales

came to symbolize the wild marine environment, and audiences were offered a glimpse of a world that most people could not access otherwise. Marine parks and movies like “Namu” (1966) portrayed orcas as friendly, relatable companions rather than vicious predators. Conservationists hoped the new interest in orcas would result in support for their protection.

The pitfalls of herding and transporting killer whales for entertainment soon became apparent. In 1970 a capture company known as Namu, Inc. used speedboats, explosives, and nets to herd nearly 90 orcas into Penn Cove on the east side of Whidbey Island. While six whales were captured for delivery to marine parks, five were killed in the process. Although Governor Dan Evans and the Washington State Department of Game (now Fish and Wildlife) received letters of protest, permitted captures continued in Puget Sound until 1976, when a court order banned the roundup and export of wild orcas from Washington waters.

As of January 2025, new rules require recreational boaters in Washington waters to stay 1,000 yards away from the now critically-endangered Southern Resident orcas at all times. This population is in serious trouble, with only 75 individuals in three pods remaining. Boat congestion poses a persistent threat, interfering with the orcas’ ability to hunt and communicate. Lack of prey, particularly salmon, and pollution also contribute to declining numbers.

Commercial whale watching and paddle tours continue to operate in Washington, providing opportunities to view orcas from a distance. Drawing from my own experience cruising for 25 years in the Salish Sea, private boaters who are patient and respectful may encounter orcas eventually on their own. Although I have not actively sought them, orcas have appeared unexpectedly in my cruises throughout Puget Sound, from Olympia to the San Juan Islands. And there are places near Desolation Sound in BC that I have seen them more often than not. Once, as I was rowing an inflatable dinghy, a pod surfaced next to me, much like Blanchet’s encounter. At water level they towered over me, and I hoped they would not take an interest in my tiny vessel. But like most wild animals I’ve seen, they went about their business, ignoring me as I sat equally terrified and wonderstruck.

“They are big,” a Seattle Times reporter observed recently. “They are beautiful. And they are back” [Linda V. Mapes, Sept. 10, 2023]. The recovery of humpback whales in the Salish Sea has been remarkable. Listed as an endangered species during the early 1970s, humpback whale populations hit a low point in the 1980s, when biologists estimated they were at 5 percent of their historic numbers. Humpbacks are migratory, beginning their lives in the tropics and using Pacific Northwest waters as their summer feeding grounds. By the mid-twentieth century, they were rarely seen in the Salish Sea.

Commercial whaling operations hunted humpbacks and other whales during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By 1925, a whaling station in Bay City, Grays Harbor had processed nearly 2,000 humpbacks. The lucrative oil from the blubber provided lamp fuel, important before electricity

became widely available, as well as a lubricant for machines used in various industries. The products taken from humpbacks and other whales supported many coastal communities for years.

Yet commercial hunting was not sustainable, and the International Whaling Commission banned it in 1966. Twenty years later, the commission prohibited commercial hunting of all whales worldwide, though special provisions allow subsistence hunting by Indigenous people. These measures, along with environmental regulations promoting clean water, led to a return of humpbacks to the Salish Sea and the coastal waters of BC. Biologists estimate that thousands of individuals have been spotted in recent years. So successful is this story that humpbacks have become a symbol of marine conservation. Public interest in these gentle giants is strong, with sightings widely publicized. “You never saw them” in the past, marveled Joe Gaydos, science director for the SeaDoc Society, an Orcas Island nonprofit. “Now we see them willy-nilly, spring, summer, fall, winter” [quoted in Seattle Times, Sept. 10, 2023].

The evidence suggests that opportunities to view humpback whales from the water will increase in the near future. During the last several years, I have encountered them in private boats, power and sail, in the South Sound, Strait of Juan de Fuca, Strait of Georgia, and in the waters around Hecate Strait in BC. These whales are so big that I see them in sections rather than viewing the whole creature. Rounding Cape Scott in my 26-foot sailboat, for instance, I found the humpback’s eye especially fascinating, as I wondered if he was looking at us as we watched him. For me, the most common sight of humpbacks is their flukes slapping the water as they dive. And in a recent cruise to BC, I witnessed humpbacks engaged in “bubble net” feeding, a cooperative behavior that corrals fish by blowing air around them, making it easier to concentrate and gulp the prey. These whales are also known for their complex, haunting songs, adding to their charm and public appeal.

Encounters with whales and the vast array of other marine life provides a glimpse into the wild soul of these cruising grounds. They’re a memorable and enriching aspect of adventures large and small, and a perpetual reminder to all boaters of how lucky we are to share the water with such creatures.

Lisa Mighetto is a historian and sailor residing in Seattle.

by Meredith Anderson

The summer sailing season has come to an epic close with some absolutely beautiful weather, ushering us into the always-too-short Pacific Northwest autumn. In September I found myself finally underway on my own boat for a few weeks after a busy summer fixing other people’s boats and, as I pulled back into my home slip, the work on my engine was not done yet. It was time to make sure my little diesel was ready for winter.

The Salish Sea typically presents us with wet and cold winters, and since most of us are fair weather sailors, our boats don’t get used nearly as much in the offseason as they do in the summer. In order to take good care of our engines and other onboard systems, some long-term storage prep is needed. In this column, I will cover a range of winterizing tasks that should be completed to help ensure your boat and engine are ready to go next season.

For those of you who live aboard like I do, or those planning to visit the boat fairly often to run your engine or get underway, not too much has to be done in terms of long-term storage preparation. I do, however, highly encourage everyone to close all engine raw water and other unused seacocks, keep a heater and dehumidifier running when needed, and top up your fuel and treat your fuel tanks with biocide.

Even though I’m onboard every day, I still keep my engine seacock closed regularly when the engine is not in use. If it’s going to be really cold, or I am not around and the forecast suggests cold weather, I tend to keep an oil-filled space heater running on low with my engine hatch open just in case. While Washington typically doesn’t see too much in the way of hard freezing, it has happened and we have already seen local temperatures as low as 28° Fahrenheit this October. Keeping fuel tanks full will prevent condensation from forming on tank walls thus creating a water problem, which will eventually be an algae problem in your fuel. All of these practices represent practical risk mitigation.

If you are finished with your cruising season and it’s time to change your oil, now is the time to do it. I change my oil at the end of my cruising seasons to prevent any issues with acidity or moisture inside the engine over the winter.

I also run my engine at least once a month—remember that it’s important for it to be under load for a good half-hour or more either at the dock or while underway. Checking and running my engine monthly allows me to repair anything that might be developing long before I want to get underway more regularly for spring and summer cruising.

Another piece of advice I often share is to use the early part of the offseason to evaluate whether there are any large projects to complete with a boatyard or contractor. Then, make sure to get on someone’s calendar now, as most contractors will be maxedout come spring.

For those of you who are snowbirds or simply prefer to leave your boats over the winter, your engines may not get run for an extended period of time. Unless you have someone you trust to check and run the engine, you most likely will need to winterize for long-term storage. If you plan on letting the engine sit for more than a month without running it, I would recommend completely winterizing your engine and other systems for the potential cold snaps that come through.

Winterizing includes everything I have stated above: topping off and treating your fuel, keeping a heater and dehumidifier running, closing all seacocks except cockpit drains or other critical ones, and servicing what you need to on your engine. To protect against potential cracks and fractures in hoses and fittings from freezing and thawing, winterization also includes running a special antifreeze through your raw water and fresh water systems.

A lot of the water in Puget Sound is somewhat brackish due to the influence of various rivers, creeks, and other runoff. While pure saltwater may not freeze as readily as fresh water, the fresh water at the surface of our local waters can freeze more quickly than you’d think. Engine repairs for blown heat exchangers, hoses, and through-hulls can be very costly, so having antifreeze

in the system will prevent that.

Some boat owners may choose to have a professional handle winterization, but it is a doable project for many DIYers. To winterize an engine, close your raw water intake and run a hose into a bucket of antifreeze while the engine is running for a short period to pull the antifreeze into the raw water system. With certain setups, you can have a friend start up the engine while you pour a few gallons of antifreeze into an open sea water strainer with the seacock closed. When you see the antifreeze come out of the exhaust, you will know it has made it though your engine’s raw water system, and you can shut everything down and reconnect your hoses.

When spring arrives, simply reopen your seacock and run the engine like normal, as the special winterizing antifreeze used for this purpose is biodegradable. This type of antifreeze is sold at most marine stores and chandleries. Make sure you are NOT using regular engine coolant or antifreeze from an autoparts store. If you need help, most boatyards and contractors should be able to help you winterize these systems before you leave the boat for an extended period.

While your engine is important, so are your other systems onboard. Things like making sure your shore power cables are in good condition, your onboard electrical is in good shape, your fresh water system is winterized for long-term storage, mooring lines are secure, and cockpit drains are free and clear can really ease a lot of stress when you can’t get to the boat. As a liveaboard, I can check things daily and adjust as necessary, and it has paid off when my boat and I have stayed safe in some really uncomfortable winter storms. If the span between checks goes from days to weeks or months, it only increases the need to be thoughtful, proactive, and strategic in your preparations.

While most winters in the Pacific Northwest are fairly mild compared to other northerly locations, it’s not uncommon for us to see stretches of days or even weeks with temperatures below freezing, and this can result in a lot of damage for unprepared owners. I cannot stress enough the importance of closing your seacocks and properly winterizing your water systems if you are going to be away.

Also, if weather moves in, asking someone you trust at the marina to briefly check on your boat is always a good idea, especially if there is significant snow or a hard freeze. I am always happy to check on friends’ and neighbors’ boats while they are away, so don’t be afraid to reach out and lean on your community.

Time invested making sure your boat is in good stead while you’re away for any amount of time is always well-spent. It can save the day when the weather takes a turn and you can’t make it to the marina.

Meredith Anderson is the owner of Madame Diesel, LLC, where she operates a mobile mechanic service and teaches hands-on marine diesel classes to groups and in private classes aboard clients’ own vessels.

Changing the oil is a great end-of-season project to prevent acidity or moisture issues inside the engine.

Engines are important, but all systems should be thoroughly checked before leaving the boat for extended periods.

by Jennifer Dalton

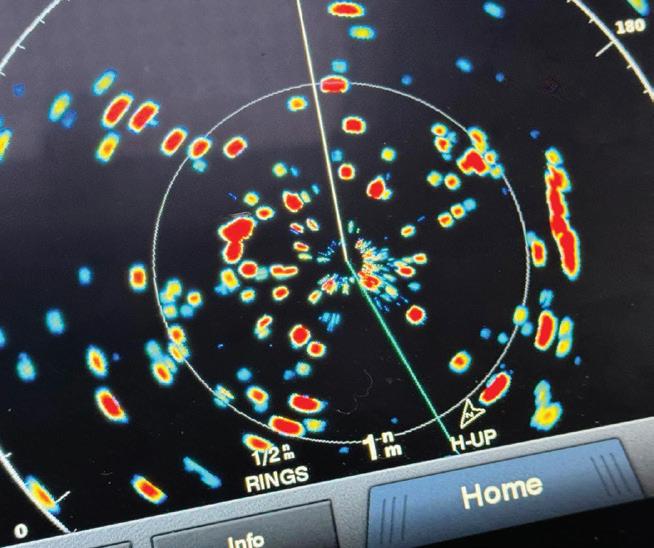

The Anacortes-based crew of One Ocean has completed the Northwest Passage since the time of this writing—the first major milestone on their 27,000-mile expedition. In fact, they have turned south and are now in Bermuda. That may sound idyllic, but shortly before this issue went to press, their five-day passage from Nova Scotia to Bermuda found them in the midst of an Atlantic storm that was unlike anything they had ever seen. One Ocean endured 50-knot winds for days, a gust as high as 69 knots, and towering waves crashing over the boat and causing damage. The boat and crew are fairly battered, but they are all safe. They will be recovering and making repairs before pushing on. Learn more about their journey at www.oneislandoneocean.com

It’s my turn at the helm. I’ve been on watch with Grace and Mark since 10 p.m., and it’s now 12:30 a.m.—an hourand-a-half left before a crew change. The temperature outside is 32 degrees and there’s no wind, but lots of fog. We’re lucky to be able to steer from inside. Despite the intensity of the situation, the cabin is warm and cozy. Grace is crouched on the couch with binoculars, scanning the port side. Mark paces between her and me. We are all hyper-focused on what’s before us… ice, ice, baby.

The ice pack ranges from three- to five-tenths (sea ice concentration is represented as a fraction of surface coverage, in tenths). So far, we’ve been able to thread the needle, but it’s tight. Suddenly, a loud scrape on the starboard side—the hull hit a submerged ice chunk. My shoulders clench toward my ears. A bitter, metallic taste floods my mouth. I swallow hard. Stay focused.

The three of us make constant decisions—moment by moment. Grace and I work in sync, calling out leads in

the ice: “Leaping dolphin to port! Soaring eagle to starboard!”

“Four minutes left,” Grace announces. We’ve shortened shifts at the helm from 30 to 15 minutes to stay sharp. My hands grip the hydraulic wheel, which isn’t the easiest to steer. I take a deep breath. I can do four more minutes. Slow, steady. We’re deep in it now. I have to get us out—no other choice—but the ice looms taller, darker ahead.

Grace calls for me to steer to port. The ice blocks my view. My time is up and it’s Mark’s turn. He slides in and takes the wheel before I even let go—there’s no room for error. He’s already locked in. Grace shifts to the center position, and I jump on the couch with binoculars, wiping down the steamy windows.

Mark steers us port, then starboard. White ice walls streaked with orangebrown rise as tall as the windows. Suddenly, we’re in a narrow ice channel. At 4 knots, the floe traps us—we no longer have choices. We’re at the mercy of the ice.

Sea ice concentration is represented as a fraction of surface coverage. One Ocean was in three- to five-tenths.

The fog lifts, and through my binoculars I see a solid white wall ahead. I lower them and glance at Grace. Her worried look confirms she sees it too.

Mark waits for our calls, but we hesitate. The pause lingers. He asks again, then spots the wall himself. I tell him to hold the course. We stay quiet as Mark shifts One Ocean to neutral. She drifts toward the massive wall. We wait, hoping something will open.

When we’re about a football field away from the dead end, a channel to starboard suddenly opens. Grace calls it, and Mark turns the wheel. The turn is so sharp I worry that One Ocean won’t make it, but she does. Moments later, he swings her hard to port. The chartplotter

shows us edging farther out to sea toward thicker ice. The charts predict 5–9 tenths there. Our fiberglass hull can’t handle that, but for now, we have no other choice.

Mark’s fifteen minutes fly by and now Grace is at the helm. We call out leads, working our way to starboard. About forty-five minutes later, we see open water and finally set course toward land.

By the time the next shift of crew wakes, we’re exhausted. We collapse into our bunks, knowing that in just four hours we’ll be back on watch.

Sure enough, four quick hours later I woke to the sharp urgency of directional calls—”port” then “starboard!” We’re back in first-year pancake ice, one to

three inches thick. Easier to see over, but endless. I hastily pull on my trusty gear (the Meris line from our supporter, Mustang Survival) and head for the pilothouse.

We’re a mile offshore from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. Dave is at the helm while Tess and Mike call out leads. But again, there seem to be no options. Their watch is technically over, but for now we need all eyes on deck. Mark and I discuss sending me up the mast when Mike suggests flying the drone.

Dave finds a patch of open water, and we float while Mike and Grace set it up. I scramble onto the cabintop with binoculars. The fog has lifted, the sky is clear, and I can scan in all directions. Vigilance is

Mike and Grace, experienced drone flyers from our kelp studies, set the drone on the stern. It lifts, hovers, and then clips the edge of the dinghy, flipping upside down into the icy sea. Luckily, the floats Mike added keep it on the surface, and they retrieve it quickly. Meanwhile, Dave holds One Ocean clear of the ice. I stay on the cabin roof, scanning for leads. The cold bites at my cheeks, but the fresh air sharpens me, shaking off my fatigue. Suddenly, I spot

open water. A lead opens through the pack. I shout through the window for Dave to steer to port.

That ice is now behind us, but we knew it wasn’t over. We hadn’t yet reached the severe plug between the Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf that had blocked ships from transiting the Northwest Passage all summer. Still, we took our moments of calm where we could: exploring harbors that offered respite and eating well. We emerged unscathed,

in good spirits, and still talking to each other—for now, it’s smooth sailing.

Jennifer Dalton is the Project Director and crew for the Around the Americas sailing and research expedition that departed Anacortes, Washington in May 2025. The expedition is conducting the first ever pole-to-pole bull and giant kelp study and sharing findings through an open online education platform. www.oneislandoneocean.com

by Max Fleischfresser

When I was told there would be a boat available to me in Campbell River, I knew I had to take advantage of the opportunity. What sailor wouldn’t jump at the chance? But there’s some important context—it wasn't my boat and I’d be bringing my 2-year-old son on what would be our first big sailing adventure.

Though I spend a lot of time on the water for work, I have been yearning for a good cruise; especially since selling my 40foot C&C and becoming a domesticated landlubber. My brother George’s misfortune to put his Desolation Sound cruise on hold and return to work turned into my good luck when he extended me the offer to use his Fraser 41, Kist.

My wife and I are parents to two young children—our son Theo is 2, and his little sister was only 3 months old at the time. We quickly decided that our 3-month-old was not ready for the trip, so she would stay home with mom. I couldn’t wait to get cruising, and I was excited about sharing the boating lifestyle with Theo in such an extraordinary region. Still, a sailing trip with just me and Theo seemed impossible.

Enter my childhood friend Collin, who is neither a sailor nor a parent, but is overflowing with compassion and patience. Adding Collin’s set of helping hands and supervising eyes made this escapade doable. Our crew was assembled, and we were ready for Desolation.

After the journey to Campbell River—which was long and required a drive, a ferry ride, and more driving—reality quickly set in. We started with an extensive familiarization of Kist with George, who stayed the first night on the boat with us to help us get settled, and his walk-through was essential. She’s a great sailboat but, with her age and a couple different system upgrades, she has some idiosyncrasies.

“Batteries are good, not great. If the voltage gets down to this, then fire up. Don’t trust the engine temp alarm. Don’t let the engine idle too low or it shakes too much. Briefly throttle up and down before changing gears. Here’s how the composting head works. Here’s how the autopilot works. This is how you deploy and stow the outboard to the dinghy. Here is how you

stern tie.” This went on for hours, and anyone who has spent time with a toddler can imagine just how divided our attention was as we went along. After going over everything, I was feeling a little overwhelmed. Then came the noggin bonking.

Theo quickly found that we were no longer in an open floor plan living room. His every movement seemed to cause a screaming injury, mostly to the head. This challenge was offset by his happy discovery that this new space came with plenty of toddler-level button boxes and breakers. Any time a system did not seem to be working properly, the first step of troubleshooting was asking, “What is Theo messing with now?” He was absolutely nonstop in unearthing novel things to play with.

After an intensive first day, it was finally bedtime. I started by trying to put him down in the quarter berth, which did not have a door. That lesson didn’t take long to learn: this would not work because he was constantly crawling out to see what the adults were up to. We moved up to the V-berth. With the

Heeling over equals naptime over for Theo.

door closed, there was a deep hole down to the step, so I packed this space with some gear bags so he couldn’t fall down into it. After reading Bruce the Bear, I squeezed the door shut against the gear bags. Soon after, he was sound asleep.

I slumped down on the settee exhausted, stressed, and processing feelings of doubt and regret. This trip seemed to be too much for us. Collin and I hung out for a bit before I quietly slithered past the gear bags and crawled into the V-berth with Theo and crashed immediately, weary in every way.

Around 6:30 a.m. I got a nudge from Theo, giving the cue that it was time for me to start the day. I got him comfortable and distracted while I tried to fry him an egg. Throughout our cruise, cooking was challenging and required some serious multitasking in order to keep him from messing with something he shouldn’t while also working in the galley. As the trip continued, Collin and I eventually found our groove taking turns cooking while the other tried to keep Theo distracted and out of trouble.

Wrapping up breakfast, we got underway and headed for Gorge Harbor. This, like most of our itinerary, was based on George’s recommendation. I’d never cruised Desolation Sound before, so it was all new to me, and all exciting to explore.

Cooking wasn’t the only rhythm we honed, our daily routine rapidly took shape. Over breakfast and coffee, we would firm up our cruising plans for the day and get going. Once underway, we would take turns running the boat or running Theo, depending on the situation. With some coaching, Collin was soon competent steering the boat under sail and power, which freed me up to prepare snacks and change diapers. We found it best for us to be underway for Theo’s naptime, which worked well most of the time, especially with the soothing Volvo lullaby.

On one particular day early in the trip, the nap got cut very short. Not long after putting Theo down, the wind piped up and it was time to sail. Breeze quickly built into the high twenties. After managing sails and having a blast, I figured I should check on Theo. Stepping down the companionway, I could hear him screaming. I opened the door to the V-berth and found him pinned to the port side along with a couple of his books and toys—being heeled over meant naptime was over.

Higher wind situations were always exceptionally difficult

Heavy air sailing was especially challenging because Theo really needed to be held the whole time.

because we both would need to be mostly hands-on with the boat, while also holding Theo. We had hoped in those situations that a simple tether would be a safe and happy compromise for him. Keeping him tethered, unfortunately, proved to make him miserable and became a safety concern of its own since he would perpetually trip on or snag the tether. So, when it was spicy out, he pretty much just had to be held.

Through all this, we did actually go cruising. Our focus was always partly, sometimes entirely, on Theo, but along the way we got to visit some of this region’s most beautiful cruising destinations—Gorge Harbor, Prideaux Haven, Toba Inlet, Walsh Cove, and Tenedos Bay. Of course, there are so many incredible spots to explore that I’m eager to go back again and stop in other locations.

We ended up appreciating the point-to-point travel and wound up checking out as many spots as possible, but probably enjoyed our two-night layover stays in Prideaux Haven and Walsh Cove most of all. We ran into some friends anchored in Prideaux Haven, and had a great time catching up with them.

Toba Inlet was super cool because of the waterfall, but Walsh Cove was the destination highlight for me. The scenery is pretty dramatic. It’s a little hole in the wall you go into, and there was quite a lot of wildlife. With its warmer water, Walsh was also a

great spot for swimming and paddleboarding.

We found that it was good for everybody to get off the boat and stretch our legs. We dinghied over to check out the island in Walsh Cove, which is very pretty with its cliffs. When we were in Tenedos Bay, we hiked up to Unwin Lake. It was kind of a scramble for Theo, but he walked pretty much the whole way by himself. At the lake, there was a little lagoon with a log across part of it, just a foot or two deep—perfect for Theo. He played in there, and we could swim in deeper water just on the other side of the log. I’m not sure I’ve seen a loon before, definitely not up close, but one visited us while we were swimming, calling over and over. So cool.