The Zubin Mahtani Gidumal Foundation, also known as The Zubin Foundation (TZF) is a charity committed to improving the lives of Hong Kong’s ethnic minorities by reducing suffering and providing opportunities. For more information, please visit: www.zubinfoundation.org.

The Zubin Foundation is grateful to all the ethnic minority women who were interviewed in the research for giving their time and sharing their stories.

The Zubin Foundation thanks the following representatives for contributing their time and sharing their insights: Dr Arfeen Bibi, Azan Marwah, Chief Imam, Former Judge Sharon Melloy, Kay K.W. Chan, Patricia Ho, Puja Kapai, Dr Rizwan Ullah, Shalini Mahtani, and Swamini Supriyanda.

Authors: Sala Sihombing and Shalini Mahtani

Editor: Alka Datwani | Global Brand & Communications

Reviewer: Vibha P. Karnik | The Zubin Foundation

Cover Design: Gagandeep Singh | The Zubin Foundation

Disclaimer

All information in this document is provided for general information only and is not in the nature of advice. It should not be relied upon for any purpose and The Zubin Mahtani Gidumal Foundation Limited (TZF) makes no warranty or representation and gives no assurance as to its accuracy, completeness or suitability for any purpose. Inclusion of information about a company, programme or individual in this publication does not indicate TZF’s endorsement. Where cited, you should refer to the primary sources for more information. TZF reserves the right to make alterations to any of its documents without notice. The information and ideas herein are the confidential, proprietary, sole, and exclusive property of The Zubin Mahtani Gidumal Foundation Limited. The Zubin Mahtani Gidumal Foundation Limited reserves the right to make alterations to any of its documents without notice.

© 2024 The Zubin Mahtani Gidumal Foundation Limited. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of this document (in whole or in part) is not allowed without prior written permission of The Zubin Mahtani Gidumal Foundation Limited and due acknowledgment of authorship. If use of this document (in whole or in part) will generate income for the license, prior written permission to that effect must be obtained from The Zubin Mahtani Gidumal Foundation Limited. To obtain permission, write to info@zubinfoundation.org.

Improving

Sala Sihombing, author

Sala works full-time as a mediator focusing on families in Hong Kong. She is an accredited mediator (Australia NMAS) (USA FINRA) (Hong Kong HKMAAL/HKIAC) (UK CEDR) and Family Mediation Supervisor (HKMAAL). Since 2013, she has taught as an adjunct lecturer at HKU in the LLM ADR Programme.

Having originally qualified as a solicitor in the UK (1995); and Hong Kong (1996) she worked as a criminal and civil litigator. She left private practice to work as in-house counsel at Peregrine and Crédit Agricole Indosuez and later joined Morgan Stanley in the Institutional Equity Division.

In 2011, Sala attended the Straus Institute (Pepperdine University, USA) to receive her LLM in Dispute Resolution. Her LLB (Hons) is from the University of Bristol, UK.

Shalini is the Founder and CEO of The Zubin Foundation (TZF), a charity that improves the lives of Hong Kong’s ethnic minorities by reducing suffering and providing opportunities. TZF works directly in the community through its outreach work and enhances awareness of Hong Kong’s ethnic minorities and race through its Institute of Racial Equality.

Shalini has authored and co-authored work on ethnic minorities in Hong Kong including, but not limited to ethnic minority children with special needs, mental health and youth aspirations. Her research informs public policy recommendations as well as corporate training on race and culture.

Shalini is a member of the Commission for Children of the Hong Kong Government and is the Convenor for its Working Group for Children with Specific Needs. She has a Medal of Honour from the HKSAR Government, an MBE and other accolades. Shalini is from Hong Kong, married and has 3 children.

It was in 2018 that The Zubin Foundation was faced with our first case of forced marriage. The young woman had finished a year in a Hong Kong community college and was volunteering with The Zubin Foundation. I am going to call her Amari, not her real name. She told me that after the summer holidays, she was getting married. She was scared and she had wanted to delay the marriage to her first cousin by a couple of years, but her parents had disagreed. She did not want to marry her cousin in Pakistan but the cost of not doing so was too great for her sisters to bear – her parents threatened to withdraw all of them from school in Hong Kong and send them to Pakistan, if she did not agree to the marriage. She told me this practice of forced marriage was common in Hong Kong. Amari is a Hong Kong born young woman, educated in Hong Kong schools and spoke perfect Cantonese. Her case had a profound impact on me.

Was Amari’s case a one-off? We were not sure, so we decided at The Zubin Foundation to better understand the dreams and aspirations of Hong Kong Pakistani children. Was it true, what Amari said? Was forced marriage “common” in Hong Kong in her community? In 2019, together with Puja Kapai at The University of Hong Kong we explored the dreams of twenty-five Hong Kong Pakistani children and youth aged 14 to 22 years old in our report, Dreams of Pakistani Children. In that report, amongst the research sample, we noted early engagement and marriage among Pakistani girls was prevalent. Some brought up the term “forced marriage” and the struggles they were facing.

According to the Chief Imam of Hong Kong, Mufti Muhammad Arshad, at our 2021 conference titled “What is the Status of Hong Kong’s Ethnic Minorities?” forced marriage is not permitted in Islam and consent from a woman is required for a marriage to be valid. So, why does this practice take place? There are so many reasons, but mostly it’s about culture, honour and ‘face’.

In Hong Kong, we do not have official numbers of forced marriage cases and for this report “Time to UnMute | Understanding Forced Marriage in Hong Kong” we contacted seventeen Hong Kong women who were forced to marry, and all known to The Zubin Foundation. Eleven of them agreed to participate. There are four overarching messages of this report:

1. Local and Global Problem: Forced marriage is a Hong Kong problem and is also a global issue that can also affect men. Over history, forced marriage has been practised in many parts of the world, where parents chose the husbands and wives for their children, who have no say.

2. Culture not Religion: All our women interviewees who face forced marriages in Hong Kong faced cultural issues, and we do not call this a religious issue. Most of our interviewees are practising Muslims and have deep faith in their religion.

3. Children are Abused: Forced marriage impacts Hong Kong’s children. Five of the women were under eleven when the ‘engagement’ took place. The girls were contracted to marry the chosen spouse often without their awareness, and two were under 18 when they were married. This is unacceptable and the Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse Law must ensure forced marriage is understood by mandatory reporters and does not go undetected.

4. Forced Marriage Starts Young: Forced marriage cannot be thought of as a single point in a girl’s life but a continuum of expectations that are set, and gendered child rearing that starts when children are young.

5. Lacking Support: Hong Kong needs to better support forced marriage victims. As an immediate need, a contact list of services to help forced marriage victims access help is imperative.

A massive thank you goes to Sala Sihombing, the author of this report. Sala approached me at a Hong Kong Family Lawyers Association seminar I gave on Forced Marriage in 2023. She was surprised forced marriage existed in Hong Kong, as many are, and wanted to better understand the problem. She has delved deep in the subject and this report represents a fraction of what she has learned.

Most of all, immense gratitude goes to all the women who agreed to be interviewed for this report. To each of you, I appreciate the trust you placed in us to tell your stories. This report is dedicated to you, and we have called it “Time to UnMute”, because it’s time your voices are heard.

As always, I welcome your comments and views.

Warmly,

Shalini Mahtani Founder & CEO The Zubin Foundation

This report highlights the reality that forced marriage occurs in Hong Kong. Eleven women were courageous and generous enough to share their experiences and perspectives on early and forced marriage.

The introduction to this report defines forced marriage. If a party to the marriage does not wish to marry, then a marriage may become a forced marriage. Whilst a person of any gender can be subjected to a forced marriage, it remains a highly gendered practice.

There are powerful myths which surround forced marriage. The primary myth being that this doesn't happen in Hong Kong.

The heart of this report are the responses from interviews which share the words of the interviewees. These women are Hong Kong women. These are Hong Kong stories.

The women were clear about the delineation in their view between an arranged marriage in which the consent of both parties is required and a forced marriage in which a person is coerced into marriage. All shared their subjective viewpoints. In listening to their stories, it was clear from their words that pressure / coercion had been applied to several of the women, even if they did not see themselves as being forced.

This is also a context surrounding forced marriage. Rushing a young person to marry as soon as possible or bringing a marriage forward in time, can pressure someone, especially when the reality is that no other options are permitted. For example, options to marry later, not marry, or to marry a third party are not allowed

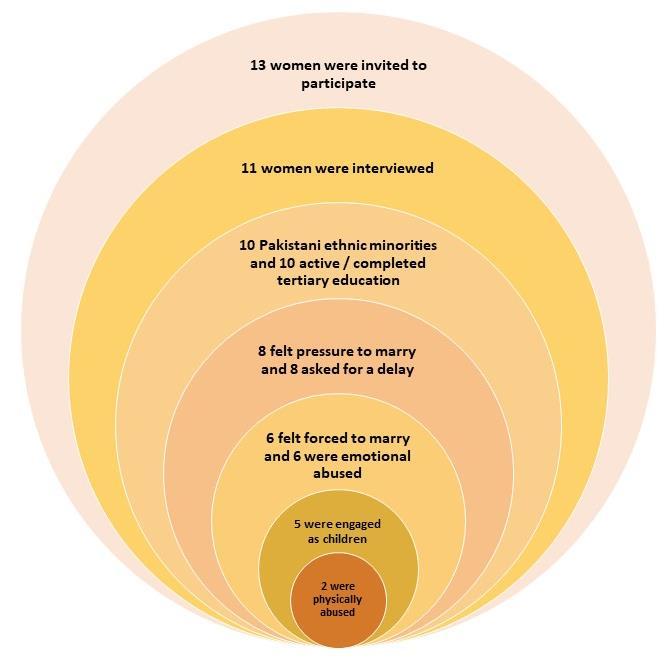

Of the eleven women interviewed, their characteristics were as follows:

● Five were engaged as children and often only found out as adolescents about the contracted marriage - merely awaiting the formal marriage ceremony. Two were married as children. Forced marriage impacts children in Hong Kong, emotionally and physically.

● One was of Indian ethnic origin and ten were of Pakistani ethnic origin.

● Seven of the women were born in Hong Kong and the remainder came to Hong Kong as children.

● All eleven were educated in the Hong Kong educational system and all, apart from one, were able to complete their secondary education.

● Most of the women have either completed or are in the process of completing tertiary education.

● Eight of the women felt pressured to marry and six of them felt they were forced to marry.

● Eight of the women were still married at the time of the interview, one was divorced and two were single having been able to escape the forced marriage.

● Six of the women were married to a cousin.

● Two of the women had mothers with no formal education; six women had mothers with a primary education only; two women had mothers with a secondary education only and one woman had a mother with a tertiary education.

● One woman had a father with no formal education; four women had fathers with a primary education only; three women had fathers with a secondary education only and three women had fathers with a tertiary education.

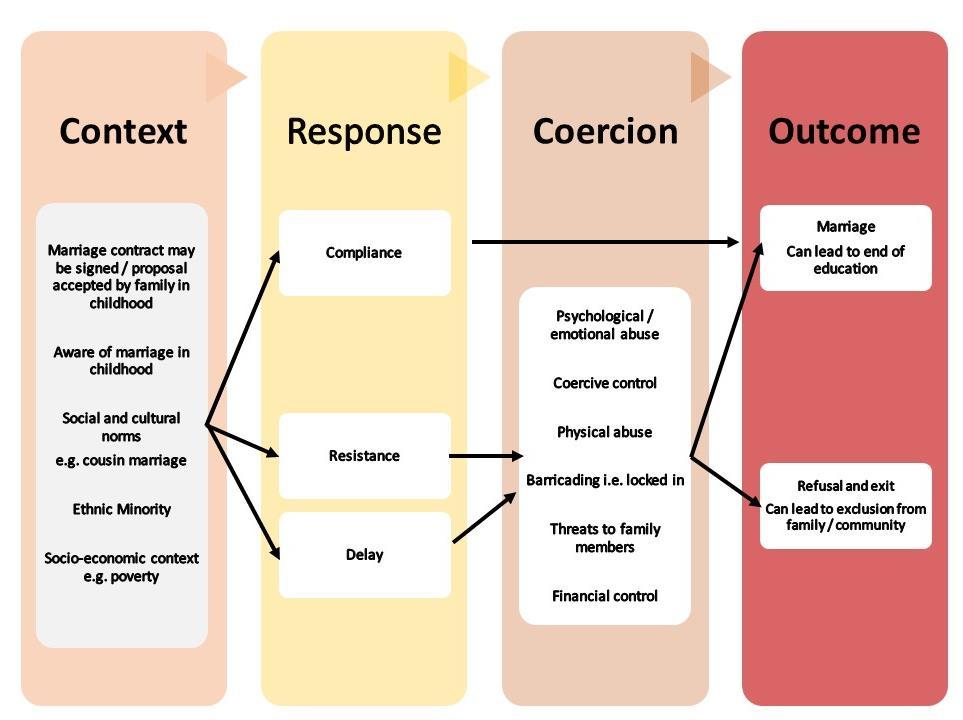

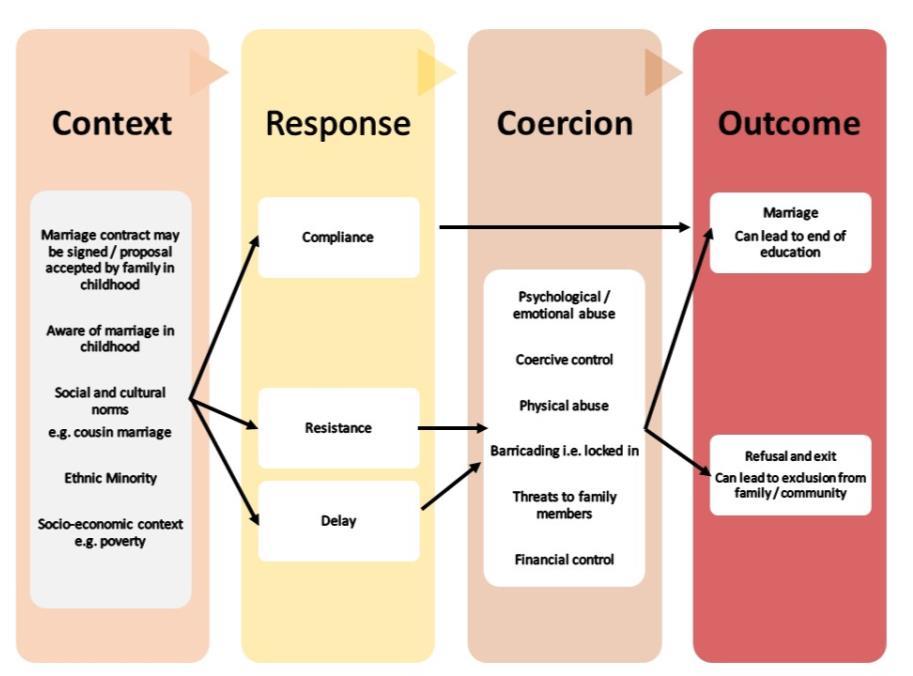

It is key to understand forced marriage is a process which often begins in childhood. Some of the women knew as children that a husband had been chosen for them. Typically, the women found out as teenagers or were told from a young age that the engagement had already been concluded. As a result, they grew up with the knowledge that their life partner had been chosen. This reduces their life options as from childhood they know the expectations of their family are for them to marry this specific person.

In terms of the coercion applied, the methods included:

● emotional and psychological pressure, including verbal abuse. For example, being told her father wished she was dead.

● physical abuse

● coercive control.

● confinement For example, one woman was locked in a room in Pakistan for a month and a half before escaping.

● threats against their siblings. For example, one woman explained she was sustained by having younger sisters. Knowing that if she gave in and consented, they would also be required to marry, perhaps against their will, strengthened her resolve.

Why do they think forced marriage happens?

When discussing the reasons for the forced marriage, many of the women referred to tradition and custom in marriage as opposed to religion. They were clear that their religion does not permit forced marriage, however, they referred to custom and tradition which perpetuates these practices. In fact, all the Muslim women described themselves as devout. For one woman, her faith in Allah meant she needed to resist forced marriage. For some this faith leads them to decide to commit the sin of disobedience and even suicide rather than for their parents to sin by forcing their daughter into marriage.

What are some of the choices they made?

For one woman, her experience was made much worse by the fact that her father had been supportive of her dreams, and she notes it seemed as if her father was as surprised and confused by his behaviour as she was. She tried to engage with him, by comparing her being forced to her father’s situation as he had not chosen who to marry, however this made matters worse. The situation became extreme, and she attempted suicide. She withdrew from her family and Hong Kong.

One woman made the decision to run away when she was 16 years old. She was lucky and found support from the Hong Kong Police Force and the Social Welfare Department. She was able to escape the marriage; however, she has struggled to proceed with her plans given the interruption to her education.

What would they say to their families?

Asking the women what they would wish to say to their families, if they could speak freely elicited strong responses. They had advice for those in similar situations, including seeking ways to communicate with the parents, e.g. talk to your parents in a way they don't feel you're opposing them; try speaking to your mum or a family friend first and get them to convince your dad. However, one explained that if you are being forced, then 'run away please'.

There are women who also expressed that even if they felt it was too early to marry, it was also important not to lose the chance of a good match. The value placed on the good match was high amongst the interviewees. Although for some of the women, someone from Pakistan from a village who has experienced a very different life to Hong Kong, would not be a good match. There was concern that such a spouse would struggle to adapt to Hong Kong.

Several of the women knew the chosen husbands as they were cousins, and they may have interacted with them as children. However, most of the interviewees shared they had not had any contact with the chosen husband prior to the marriage. They expressed how difficult this was for them to accept. Unusually one woman had been able to communicate freely by texts prior to the marriage. She used this as an opportunity to see if her husband-to-be had similar thoughts about the future.

What do they all have in common?

The importance of their personal educational goals was apparent as eight of the women asked for the marriage to be delayed, to enable them to complete a part of their education. All of them discussed their education and plans for future employment to support their family and themselves.

The sense I received from speaking with these women was of their resilience and their sense of self-belief. These are extraordinary women. Rather than focus on the wrongs that occurred, their focus was on the future and their belief in their ability to make a better future through their own efforts. For women who could be seen as victims, as a group they were all working to fulfil their own potential. Their capacity for understanding and forgiveness is exemplary.

Part 3

The next part of the report considers the context for forced marriage - from the global context to the specific Hong Kong context. Understanding the demographic, social and cultural context in which the interviewees exist is helpful to frame their words. The last sections consider the Hong Kong legal context and a question of why forced marriage continues to occur. Understanding the hold of tradition even on young Hong Kong women can be surprising, e.g. the extent of consanguineous marriages designed to maintain connections with family overseas.

Part 4

Insights from religious leaders are shared to provide religious context to the report. As noted, whilst religion may be claimed as a justification for forced marriage, this is not accepted by the religious leaders who shared their words.

The Chief Imam explained that marriage should be with mutual consent of both, there is no room for forced marriage.

Swamini Supriyanda says that from a religious standpoint, marriage is clearly understood as the union of two equal individuals for the purpose that they may support each other in their responsibilities, in the pursuit of knowledge, and pleasure, and in the combined growth in age as well as emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually. Valuing our daughters is not only valuing our future but increasing our strength even in the present.

Hong Kong has an active civil society and several civil society leaders from Hong Kong were able to share their perspectives on forced marriage in Hong Kong.

Some shared their experience of working with girls and women in Hong Kong. They described the use of emotional blackmail and referred to the ‘family’s honour’ and that in the end girls can feel there are no choices for them.

One perspective highlighted that Islam is ‘very beautiful and I feel it’s so misrepresented'. This echoes some of the observations from the interviewees.

Part 6

Hong Kong exists within a global context and the next section considers the global response to forced marriage. This ranges from criminalisation to community engagement. There are several tools used globally to address forced marriage, and often used in conjunction with each other:

● Forced marriage has been criminalised in several countries including Australia. In Australia, the offence also covers taking a victim overseas which may constitute trafficking. The Police note the challenge for victims in working to prosecute their family members. The criminalisation was part of a series of government and civil society initiatives which formed a landscape with civil protection, support services, education, and awareness.

● Immigration legislation such as in Denmark. In 2003, Denmark introduced a raft of immigration legislation that required each spouse must be at least 24 years old before they can apply for family reunification based on marriage and other requirements. The most significant change could be the introduction of the supposition rule i.e. that a cousin marriage is a forced marriage.

● Civil protection such as the Forced Marriage Protection Orders (FMPOs) in the UK. An FMPO is an injunction which can help to protect a potential victim of forced marriage e.g. by ordering another person to stop harassing a victim. Approximately 200-250 FMPOs have been granted each year between 2014 and 2021. Other initiatives in the UK include the Children Missing from Education ('CME') initiative, as girls may be removed from school to travel overseas for the purposes of marriage.

● Community engagement and empowerment such as in India. UNICEF has acknowledged the progress towards ending child marriage which has been made in India in the last two decades. The significant declines have been associated with improvements in female education, a reduction in poverty and fertility, the promotion of positive gender norms, and the strengthened capacity of social service, justice, and enforcement systems, among other factors.

Part 7

Involving policy and legislation with family life and intimate decisions about marriage is challenging. What is clear is that interventions need to be considered and responsive to the needs of the individuals and the community. The Zubin Foundation proposes that there is a continuum of actions under four broad categories:

Improving the lives of Hong Kong’s ethnic minorities by reducing suffering and providing opportunities

● Stage 1: understand - the first step on this journey is understanding the issue which means understanding forced marriage is a process which often starts in childhood and may be child abuse and that mandatory reporters understand this. Putting together a Forced Marriage Assistance List and collecting data on forced marriage is crucial.

● Stage 2: safety - focus on the support systems that ensure safety to victims and potential victims of forced marriage, in the short-term, medium-term and long-term.

● Stage 3: mindset - address the mindsets which enable forced marriage to occur - provide education and awareness training to frontline responders, religious and community leaders, youth and parents.

● Stage 4: legislation - introduce specific civil protection and criminal offences. Consider collection of data about spousal sponsorship visas.

Overview

Improving the lives of Hong Kong’s ethnic minorities

“

‘My voice was never heard by my parents.’

- words from an interviewee

The objective of this report is to amplify the voices of Hong Kong women, their views and their experience of forced (and early) marriage. Their voices were requested as a series of interviews. These interviews constitute the heart of this report.

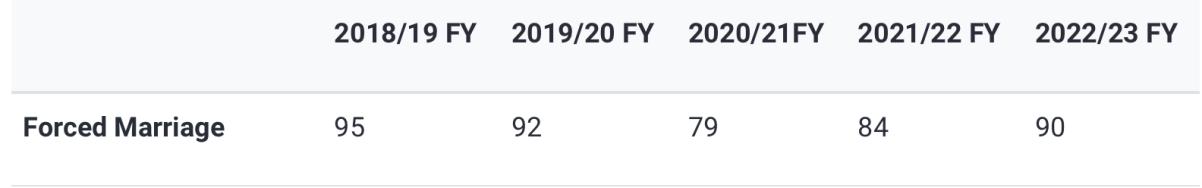

Forced marriage is a complex and global issue. Hong Kong is not exempt from this practice. This project is inspired by the experience of The Zubin Foundation. During the last few years, The Zubin Foundation has been receiving requests for assistance and guidance from girls and women, in relation to forced marriage through calls to the Call Mira helpline or through their outreach in counselling and educational sponsorship. The Call Mira helpline received calls related to forced marriage and had contact from girls and women during the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) noted that the disruption and hardship caused by COVID-19 in this period ‘exacerbated the underlying drivers of all forms of modern slavery, including forced marriage’1

The Zubin Foundation connected with women who were willing to be interviewed about forced (and early) marriage. Some of the women who shared their thoughts have personal experience of early and/or forced marriage. They wanted to share their understanding about these practices. There were also other women who had faced forced marriages who did not want to be interviewed, mostly due to the fear of being identified and the dangers that may come with it.

Findings from the interviews led to a desire to ensure the voices of the interviewees and their perspectives can be heard. It was also important to understand the wider perspective of forced marriage from religious leaders and civil society leaders, and their views have been included too.

The final part of this report is a section containing recommendations based on considering global experience and the Hong Kong context. This section is written jointly with Shalini Mahtani, The Zubin Foundation’s Founder and CEO. It is hoped that these recommendations can stimulate further discussion, education, and implementation of support for forced marriage victims in Hong Kong.

A marriage may be planned and desired by immediate and extended family members. They may have a variety of reasons for seeking the marriage including family relations, finances, property and traditions. If a party to the marriage does not wish to marry, then a marriage may become a forced marriage.

Improving

A forced marriage is a marriage where coercion has ‘destroy[ed] the reality of consent and overbears the will of the individual’2. These words contain a myriad of possibilities for the pressure that may be applied, from physical abuse to emotional coercion and duress. The simplicity of these words belies the complex interactions and nuanced reality of forced marriage.

Forced marriage can also be seen as a process rather than an event3. Chantler et al. noted in their work interviewing professionals:

Forced marriage is a ‘process’ which is rooted in gender-based violence, synonymous to ‘grooming where someone is being prepared for a marriage and that over a period of time their ability to consent, or rather withdraw consent, is compromised’ (Case Study Area 4, Third Sector Organisation 4B)4

As a child grows up in a culture they are exposed to the values, beliefs, traditions and norms of their culture and family culture. This can include attitudes towards expectations for marriage, their future opportunities, and their obligations to their family and community. They may have been aware since childhood that their marriage has been planned.

A person may indicate they do not consent either actively or passively. This lack of consent for the marriage may be demonstrated as a direct refusal or it may be silent resignation. A refusal to marry the chosen person may be seen as more than a mere rejection of the marriage and constitute a direct affront to the authority of someone’s immediate and extended family. It may also be interpreted as a rejection of cultural norms.

Whilst a person of any gender can be subjected to a forced marriage, it remains a highly gendered practice, and mostly applies to girls and women. The ILO estimates that in 2021, 22 million people (over two thirds being girls and women) were living in situations of forced marriage5. This represents a 6.6 million increase from the previous estimate in 20166 As the ILO notes, forced marriage is a ‘highly-gendered practice…[which]…is often underpinned by patriarchal norms’7. The coercion is usually applied by immediate and extended family members8. It may also be endorsed and supported by the community and community leaders.

Although both women and men may be subjected to a forced marriage and may suffer from the same treatment if they resist the marriage or go through with the marriage, the consequences can be very different:

It is important to note that while men comprise a small percentage of victims (approximately 15 %) (HAC 2008, Ev 447), research indicates that far more women experience forced marriage than men, and that the practice has more serious consequences for women (Ouattara et al. 1998; Gangoli et al. 2006; Anitha and Gill 2009; Gangoli and Chantler 2009, 269). In addition to the denial of a choice of marriage partner, the harms of forced marriage can include: rape, forced pregnancy, lack of control of the number and spacing of children, interruption to or denial of education, physical violence and beatings, kidnapping or imprisonment (sometimes abroad), murder, lack of freedom of sexuality (especially if a victim is gay or lesbian), and psychological stress which can result in threatened suicide, mental breakdowns, eating disorders and self-harm (Ouattara et al. 1998; Beckett and Macey 2001; Sanghera 2007; Brandon and Hafez 2008; HAC 2008; Macey 2009)9 .

For those working within this space, a commonly used acronym is CEFM which stands for Child, Early and Forced Marriage. There is certainly often an overlap between forced marriage and marriage with children, i.e. those under 18 years in Hong Kong and earlier i.e. may be considered someone between 18 and 24 years who could still be in full-time education.

There are some common myths about forced marriage which continue to persist:

● Forced marriage is the same as arranged marriage.

● Forced marriage is condoned by religion.

● Forced marriage means only physical violence.

● Forced marriage only happens to girls.

● Forced marriage does not happen in Hong Kong.

● Forced marriage only takes place within South Asian communities.

The words ‘forced marriage’ can provoke extreme reactions from denial to activism. Myths about forced marriage obscure the reality of this practice. The myths make it harder for people to find ways to deal with challenges and find the resources they need. The acceptance of myths can lead to ignorance and prejudice. This report aims to bring awareness to the practice, specifically in relation to Hong Kong people.

An arranged marriage will typically involve parents and/or extended families seeking to arrange a marriage between the parties, however the marriage will occur with the consent of both parties. Whilst the bride and groom may have limited or no contact prior to the wedding, the bride and groom retain their ability to refuse the marriage.

Arranged marriages are not synonymous with forced marriages, however an arranged marriage can become a forced marriage. In an arranged marriage, the desire of family and relatives for an arranged marriage to occur can cross the line and become a situation of a forced marriage. Forced marriages and arranged marriages exist on a continuum10

Lam found that in Hong Kong:

Forced marriage is the worst from my informants’ perspective. Arranged marriage, on the other hand, is a marriage based on an agreement of both sides’ parents. The man’s side proposes to the woman’s side, and her parents decide whether to accept or reject the proposal. My informants told me that for arranged marriages parents usually ask for children’s consent and preferences in the Pakistani community in Hong Kong. They accept the approach only when it meets the requirement of their children11

There exists a belief that forced marriage is condoned by religion. As shared by religious leaders in this report from Islam and Hinduism that belief is not correct. These leaders highlighted that there is no place for coercion in relation to marriage.

Whilst most of the women in this report who experienced forced marriage are Muslim, Islam does not condone forced marriage.

Islam doesn’t appreciate pressurising in any aspect of life, even in the affair of marriage. Islam emphasises knowing the willingness of a man and woman to choose his/her life partner and, therefore, disallows forced marriage. The Muslim woman has the right of refusal and acceptance of the proposal of marriage, even against her parents’ will12 .

Despite this clarity, Muzaffar et al. explained that although Islam prohibits forced marriage, elders in communities and families will ignore these prohibitions as ‘choice or opinion of the girl about her marriage

is deemed as improper in the context of family honour’13. Therefore, individual or community beliefs and attitudes prevail.

Although, “Many Pakistani marriages are arranged, brokered by the family elders” (Evason et al., 2016, para.11), in Islam “the right to choose a husband were understood as rights given to women by Islam” (Khurshid, 2018, p. 92)14 .

The myth that forced marriage always involves the use of physical violence is persistent. Although physical violence can be part of the coercion used to compel a forced marriage, it may not be used at all.

Forced marriage is a form of family violence, and thus the process is ‘often similar to the forms of abuse and control utilised by perpetrators in abusive intimate partner and family relationships’15

As with the approach to family violence, in some respects there has been an evolution of understanding. Although concerns are still expressed that:

Issues of physical and sexual violence are frequently privileged over emotional pressure and coercion. In particular, the term ‘force’ was not thought to adequately cover issues of subtle pressure where a young person may not realise what is taking place until it is too late or may not themselves identify the marriage as ‘forced’ as no physical violence occurred. Concerns were expressed by participants that the term ‘forced marriage’ as conceptualised now was limited and often did not express the range of experiences that women and men went through16 .

These experiences can include the threatened loss of connection and community. Anitha et al. highlight the coercive power of the ‘potential loss of family, and thus community’17. Ethnic minority women may have or perceive few options for social capital.

None of us exist in a vacuum and the reality is that for girls and women with few resources, obedience to parents and families coupled with social norms can make the concept of free will elusive. Girls and women in the South Asian community in Hong Kong may feel that they have limited options to resist a marriage when the alternative can be exclusion and isolation. If a woman were to reject a forced marriage, then she may lose her family and her community.

Globally, there is support for the idea that for young women maintaining familial and societal bonds is so important they may submit to marry as required.

Indeed, research on the marriage practices of South Asian women in the UK also indicates that the sanctions that underpin the dominant moral codes of their society are very apparent to the young women, and play a significant role in the exercise of their agency. As one woman said: ‘‘If a girl says

no, it’s considered a bad thing’’, and ‘‘if you didn’t [go along with the marriage] there would be hell to pay from your parents and all your relatives18

...In this light, any test to determine whether or not coercion has taken place that focuses on the extent of the pressure (physical or emotional) that has actively been brought to bear on the victim might not reveal what Feinberg (1986) calls the ‘‘total burden of coercion’’ that the victim experiences. The ‘‘total burden’’ reflects the experiences of the individual, so that any decision about whether or not coercion has taken place is forced to acknowledge how pervasive, frightful, unwelcome and/or intense any pressure is, in order to determine whether or not the proposal coerces19

Forced marriage can also happen to boys and men. This report did not have the opportunity to interview any Hong Kong men about their experience of forced marriage because The Zubin Foundation has not (yet) been confronted by this in Hong Kong. In the UK the evidence suggests the main reason for males being forced to marry20 is because marriage is seen as ‘an antidote’21 for homosexual behaviour. As noted by Samad:

Although oversimplification needs to be avoided, these fall into three broad categories. One category encompassed family and peer group pressure to ensure, for example, that land remained within the family, or that a carer was provided for a disabled family member. A second concerned sexuality and independent behaviour. For example, a forced marriage might be pursued in order to control unwanted behaviour, criminal activity, sexuality (particularly gay relationships) and ‘unsuitable’ heterosexual relationships. The third category concerned protecting family honour or long-standing family commitments and perceived cultural or religious ideals (Abigail, 2007)22

Additionally, families may see marriage for men who suffer from a disability as a way of providing support for their care23. This highlights another group who may be vulnerable to forced marriage, i.e. individuals with physical or mental disability. A family may have genuine concerns for the care of their child and decide that a spouse will either be able to provide financially or otherwise.

The concern in these cases, particularly if there is a mental disability, is whether the individual has the capacity to give a valid consent to the marriage. In addition, an individual with a disability may have even less access to resources and a greater dependence on the family. Their position may be more precarious and make them more vulnerable to the risks of coercion.

Families of people with severe mental illness or intellectual disability may not see that the marriage they are organising is ‘forced’ because of cultural beliefs or lack of awareness of human rights in the UK. They may see themselves as protecting their children’s future care or financial requirements, building stronger family ties, upholding long-standing commitments, or protecting or preserving perceived cultural / religious ideals and traditions (often misguided)24 .

Hong Kong is not immune to forced marriage. The personal experiences shared by some of the women in their interviews highlight that forced marriage occurs in Hong Kong, to Hong Kong girls and women. These interviews also demonstrated that the coercion used by family members can range from emotional and psychological pressure to physical violence and confinement

In a guidebook prepared by The Chinese University of Hong Kong, it states that ‘forced marriage is the most common emanation of [honour-based violence] in Hong Kong’25. This concept of honour-based violence links the perpetuation of domestic violence with perceptions and beliefs about honour and shame. As expressed by Idriss:

While ‘honour’ is related to the chastity of women, it is also considered by the patriarchy to be far too important to be entrusted to women alone. This is an overt demonstration of patriarchy since it is centred upon controlling women’s sexual and reproductive powers by claiming the female body as ‘man’s territory’26

The attitudes and beliefs which inform these ideas about control, honour and shame do exist in Hong Kong. This may lead to milder forms of parental control over behaviour and opportunities. Although within the experience of the interviewees, some of them shared stories of physical abuse. Within the Pakistani community in Hong Kong, Lam found that:

Aysha’s parents tried to preserve what they know as Pakistani culture when they immigrated to Hong Kong. So, Aysha’s understanding of Pakistani culture was according to traditional Islamic concepts. However, when Aysha went to Pakistan for an extended stay, she realised that what her family taught her was not what was actually in Pakistan. Pakistani culture is not that traditional and not that Islamic27

The challenge of seeking to maintain connection with culture and tradition is a common theme in diasporas. As noted by one of the women in her interview, her family sought to impose what she considered to be foreign and outdated concepts in relation to her marriage. Research conducted in Hong Kong notes that:

They imagine the Islamic community through “long-distance nationalism.” This explains Pakistani families’ emphasis on Islam and “traditional Pakistani culture,” preserving it even better than people

Improving

in Pakistan. They relate those Islamic practices and values to Pakistani ethnicity because it helps them form a sense of ethnic belonging and solidarity in Hong Kong not merely because they feel “homesick” but also their need for belonging (Erni & Leung, 2014). Pakistani immigrants’ life in Hong Kong constructs the style of “Pakistani culture” to my informants. So, Aysha felt distanced when she realised how Pakistan had changed. She wanted to uphold “traditional Pakistani culture” in her mind for her identity28 .

Although this report focuses on the experience of Hong Kong women who are South Asian by ethnicity, not only is forced marriage an issue that occurs globally, it is also not limited to South Asian communities. As noted by Chantler et al. (2009)29 forced marriages in the UK, occur in other religious and ethnic minority communities, e.g. African, Middle Eastern, Latin American, Caucasian, Muslim, Eastern European, Albanian, Chinese, Jewish, Mormon, Jehovah’s Witnesses and Greek Orthodox.

Forced marriage also exists in China. Given the 'traditional practice of concubines and bride price in a normal marriage' some rural people have patriarchal views and 'a woman is still considered the property of her father before marriage and of her husband afterward'30 .

Examples of forced marriage in China from the archive demonstrate how women, with no right to refuse, are bought and sold to men for the purpose of marriage, most often in this typology by traffickers unknown to them, but also by members of their own family31 .

The genesis of this report was a series of interviews with women who were married as young women. These women were generous with their time and were gracious to share their personal stories about marriage. They shared their perspective on what young women in Hong Kong experience as they transition from childhood to adulthood. These are Hong Kong stories.

In speaking with these women, it became clear that no story is the same. There is no singular experience and there is no one way in which these women frame their experiences. This section presents their stories as examples of the diversity experienced by young women in Hong Kong. The stories ranged from women who felt supported by their family and tradition and those who felt forced to marry against their expressed will. Some of the women are still married and some have left the relationship. Some expressed concerns and were heard, and some were ignored by their families.

The responses have been disaggregated to protect the identity of the individual women. Here are the perspectives of the women who were willing to share their personal experience and where possible in their own words.

2.2 What is the demographic composition of the group?

This is a group of women with dreams for their future. The Zubin Foundation invited seventeen women to participate in interviews. Some of the women were fearful that giving the interview would expose them to negative consequences. The interviews were conducted in person, on zoom, on the phone and in one case on social media chat. Of the eleven women interviewed for this section, there were some common characteristics:

● Children: Two of the women were married below 18 years of age. Five of the women were contracted to marry or engaged to be married as children and most were not informed until adolescence.

● Ethnicity: Ten of the women were of Pakistani ethnic origin and one was of Indian ethnic origin.

● Born in Hong Kong: Seven of the eleven women were born in Hong Kong and the remaining women arrived in Hong Kong as children.

● Education: Five of the women are currently attending tertiary education; five of the women have completed some level of tertiary education and one has partially completed secondary school.

● Family size: One woman had only one sibling; the other ten women had four or more siblings.

● Mother’s education: Two of the women had mothers with no formal education; six women had mothers with primary education only; two women had mothers with secondary education only and one woman had a mother with tertiary education.

● Father’s education: One woman had a father with no formal education; four women’s fathers had primary education only; three women had fathers with secondary education only and three women had fathers with tertiary education.

● Parents consanguineous marriage: Six of the women had parents who were cousins and five had parents who were not related.

● Asked for marriage to be delayed: Eight of the women asked for the marriage to be delayed.

● Felt pressured to marry: Eight of the women felt pressured to marry.

● Felt forced to marry: Six of the women felt forced to marry.

● Emotional abuse: Six of the women described emotional abuse.

● Physical abuse: Two of the women described physical abuse.

● Related to husband: Six of the women were related to the chosen husband.

In general, the women were clear about the delineation in their view between an arranged marriage in which the consent of both parties is required and a forced marriage in which a person is coerced into marriage.

As one woman noted that she was:

“

‘Against forced marriage…in our religion it says a girl should have a say. If she agrees on marriage, then she should marry but if she says no then shouldn’t marry.’

In her view, early marriage means 10 or 11 years old. She is ‘super against that’ and noted that ‘in the past people had a different mentality’. She felt that at 17 she was ‘mature enough’ although she noted that ‘some girls may need more time to mature’.

Interviewees also differentiated between early and forced marriage. Early marriage typically refers to cases where the person is aged between 18 and 24, denoting someone who may still be in full-time education. Despite the experiences of some of the interviewees which included pressure, a few of them did not define their marriage as forced. This may be because although there was clearly strong pressure to marry by their parents, they did not see it that way. A young woman who is currently in tertiary education explained the difference for her between early and forced marriage and also her view that this practice of forced marriage no longer exists. In her opinion a woman is forced if she does not consent, and has less to do with any pressure she may have received to consent:

“

Improving

‘For me early marriage and forced marriage are two different things. So long as it’s consensual it’s fine. But forced marriage I’m personally against as well. You shouldn’t be forced to marry at a certain age or with a specific person. You should have the freedom to choose when you want to get married or at least be asked about it. Early marriage, I’m not sure. For me, 21 is quite early. But then my parents asked me about it and after talking around and getting advice…and then we eventually decided to go for it.

For forced marriage I don’t think I heard it from any of my friends or relatives for years. When I was little, I would hear ‘she didn’t want to get married and her parents forced her’ but then now I don’t think I heard it for years.’

Another woman noted forced marriage is still happening although she said that ‘even though they are forced it can still be good’. She noted some girls are forced to marry much older men or when they are too young and this was ‘not right’. In her view her marriage at 23 was young for marriage in a Hong Kong context but she added that ‘23 is not early if it’s the right age’.

She also noted that early and forced marriage are different. In her view 18 is:

“

‘…not right – especially in Hong Kong [as] that means you are still in college, or you just graduated and that is too early for a Hong Kong person.’

Another young woman explained that in her opinion, 17 or 18 years old can be okay to marry, if the girl is ‘mentally capable of maintaining a relationship…are they physically and mentally prepared for that relationship’. However, she also advises girls ‘don’t quit everything and just go for marriage’.

This woman was able to communicate with her husband before marriage even though he is not a relative and she did not know him prior to the proposal. She explained that they were able to text each other to discuss what they wanted in their future life over the course of several months. This is rare for the interviewees most of whom had no direct or even indirect contact prior to the marriage ceremony with their husbands unless they had known them as children.

“

‘I just wish they would allow two people who if they want to spend their lives together to talk together to get to know about each other because the basic questions they want to know to remove the insecurities and stuff.’

As she further explained, after observing the older generation in her family having conflict and issues in their consanguineous marriages; she had concerns about marrying a family member. She described this as:

“

‘All of [my aunts] [my grandmother] got them married in such a hurry there’s always something about their partner – they’re not always really happy…it’s more like being compromised – compromising their life.’

If she could speak freely to anyone, she said she would want to ask her grandmother:

“

‘Why are you rushing everything? Let the girls decide. They’re always saying my daughter never said ‘no’ to me…but I’m like this is our life – [do] you want us to be happy or not?’

She observed ‘it’s not really good to always listen to your parents…let the children consider’. As she explained it, she will ‘have to live this life’.

Another young woman explained, she strongly feels that:

“

‘Marriage is a big step…should be their own choice. People should never be forced to marry at an early age. You haven’t explored the world yet. Your whole life depends on that decision…hard to tell at an early age, hard enough to know yourself.

[girls] shouldn’t get pressured because this is a big decision. They should have the right to say yes or no. [there should be] no pressure from anywhere. For early marriage, I wouldn’t say it’s not good, as marriages I have seen have turned [out] in a good way. Just that forced marriage should stop…I have seen so many cases, he will make sure the girl marries him even if she doesn’t want to. No one gives priority to a girl’s decision. They could be developing their careers…people should listen to their daughters because it’s their whole life.’

A woman whose marriage had been arranged at 15, was told that her father in Pakistan was ill and that he was at risk if she did not return to Pakistan and complete the marriage when told to. When discussing early marriage, she commented:

“

‘I hate early marriages – hate, hate, hate it. If I can change one thing about my life I would be going back and telling my mother I don’t care who dies or who has the heart attack, whether it’s you or my father. I’m not going.’

There were also positive views on their marriage expressed by some of the women. In terms of her beliefs around marriage, one woman shared that she had always thought getting married earlier ‘actually is good’. She referenced that:

“

‘In our religion you’re not allowed to have boyfriends or stuff like that…so if you want to be married and if you know that you want to be married to this person then, why don’t you get married sooner so that you will avoid the bad?’

She also believes getting married at an earlier age means that ‘you have a bit more time to understand each other…you two are growing at the same time’. This woman was unusual for the high level of commitment from her parents to her education. Even after her marriage, they continue to support her and her young family to ensure that she can complete her education.

For one woman who married at 17, she shared that her husband and father are both supportive of her education. She noted that:

“

‘It is usual in our country that men wouldn’t agree with girls studying. It is very unusual for a girl to continue studying after marriage. I feel very lucky that I can study and pursue my career.’

In family decisions, she said that everyone would give their opinion and then her father would make the decision.

Although in Hong Kong, one woman noted that, ‘in Hong Kong if you know your rights and you’re not using them it doesn’t make sense’. Although she also highlighted that that:

“

‘If you’re being forced and don’t want to get married then you say no, in some places your no isn’t worth anything.’

One woman who felt forced to marry noted that early marriage occurs when girls are ‘not prepared for it’ and are ‘handed over to men we don’t know’. She sees forced marriage as an ‘abuse of the rights of a person’ and a ‘loss of freedom and more’.

2.4 When did they know that a marriage was planned?

There is some variety in the experience of the women as to when they found out about the marital plans. Some of the women knew as children that a husband had been chosen for them. Typically, the women found out or were told from a young age that the engagement had already been concluded and then at a later stage this was confirmed to them as merely requiring their acquiescence. This accords with a view of forced marriage as a process which begins in childhood when the girls are contracted to marry at an early age (e.g. 9 or 10 years) and then informed as they approach the end of secondary school (e.g. 15 or 16 years) about the identity of their intended husband. The girls are acculturated to accept this and some of the women did not challenge that they were not consulted or asked to consent before the engagement.

There were few examples where the women were consulted as to their thoughts about the engagement, regardless of their age.

“

‘So, you know in my country once you’ve said yes then it’s over for you. I asked [my father] ‘did you ask me before you said yes?’ ‘Did you even seek my consent?’ and he said ‘why do I have to take your consent? I am your father’. I said this is my life. I am the one who is going to keep him. I’m the one who’s going to feed him. I’m the one who’s going to provide for him and bring him here [to live in Hong Kong]. I’m the one who’s going to sleep with him and have his kids.’

For example, one woman said that she had chosen her husband, however she also explained that her parents and the groom's parents had decided 'when [she] was small' that they would marry. It may well be

that since she was a young child that she knew that her husband had been chosen for her and therefore growing up with this knowledge may have let her feel that this was her choice.

For another woman, at the time of the marriage contract, she thought of the marriage as a love marriage. Her mother had told her that she could not marry outside of the family, so she tried to find someone within the family. Her parents agreed to the marriage when she was 15.

“

‘I think I kind of experienced forced marriage because – there’s two steps – the contract and then going back to your husband’s house. I only did the first step. Then after one year I said a lot of times, I don’t want to marry this person. There were so many problems. I said I don’t want to take any more steps – at least I can complete my [education]. My mother said, ‘your father will have a heart attack’. [the interviewee married before completing her education].’

Unusually one of the women felt she was consulted prior to the marriage contract:

“

‘Even when he [her father] was getting me married – he asked me before that – he got my opinion first before committing to marriage.’

Although she did not refuse the marriage, she did not think there would have been consequences if she had said no.

“

‘Even if I [had] said no, I would have been convinced [by my father to marry the person chosen for me]. If I said no, it would have been a loss for me. At that time, we knew what our parents wanted for us – is the best for us. I knew this person [her husband was her cousin].’

Her faith in her parents’ choice is clear. As she notes, even if she had said no, she ‘would have been convinced’.

Sometimes parents present the husband they have chosen and then inform the girl that the only choice she has is whether she chooses to delay the wedding, usually to complete an educational stage. One woman was told by her father when she was 17 that she would be married to his friend.

“ ‘They asked me ‘we like this boy from this place of this man’s son, are you willing to get married?’. I said no. My mother said ‘you had better take him, otherwise you have no men left, and it’s not like the marriage is happening now. All girls are engaged by now, you’re the only one left’. They kept saying this over and over again, I was stressed.’

She was told by her father that it would just be an engagement and if she wanted to delay then the marriage would happen when she said she was ready.

“ ‘I only said yes because they pressured me into it. I was young and didn’t know what the consequences would be later. I thought when it’s time to actually get married, we’ll see.’

As she notes, at 17 years old she didn’t know what the consequences of this decision would be. She had thought that there would be an option to refuse to marry, however as she learnt there was no option.

Another woman explained in relation to the marriage:

“

‘It’s something that was agreed upon when I was really young. In Pakistan there’s a tradition, your parents make these decisions for you. They choose the person. For me, I don’t mind them choosing, but you need to tell me how that [chosen] person is. If I know him or not. For me, he was a friend that I knew from childhood.

I was in Form 5 when I found out. I didn't hear it from my parents, I heard it from someone else and I was so shocked. I went to my parents and asked them…and then they explained. When I was 18 they told me…

I think I would really like it if they didn’t choose the person at such an early age, because you don’t know how the person will be when he grows up. How will he be as a man? You don’t know what he wants from his future? So, if you decide when he’s just 15 or 16 then you don’t really understand or know that person that deeply. So, for this situation, I hope that if they consider the person, even consider marriage, when me and my sisters are at least 18. They should stop talking when we are at a young age.’

2.5 How did they respond?

Delay was a common reaction from most of the women. One woman said that she had wanted to marry and that it was a long process. In the beginning she was not positive about the marriage proposal; however, she described her father as understanding. She explained to her parents:

“ ‘I’m studying something really [challenging]…they know it’s like a tough thing…so they wouldn’t force me… So, in a way I would make that as an excuse to tell them in a joking way – but some truth in it.’

As she explained it, requesting a delay because of education was a common tactic. Some women would try to negotiate for a delay to complete secondary or even tertiary education before completing the marriage.

2.6 What was the nature of the coercion?

Many of the women spoke about the challenge of being pressured by their immediate family to agree to the marriage:

“

‘At the time there was constant pressure. They informed all of my relatives and friends to convince me of the marriage. In our culture, in my family, they are really conservative. If I was married at a young age, I couldn’t even understand what was going on in my life…it is like forced marriage. They wanted me to marry at any cost. I tried to show and say to my parents that I was worried, and they tried to convince me in every possible way.’

This woman explained that throughout her childhood, her mother was verbally abusive, and her father was both verbally and emotionally abusive. When she tried to convince her parents, they refused to listen, and she believes ‘they were worried I would become more capable and independent, and the fear was I wouldn’t listen to them’.

For some of the women, who had enjoyed a positive relationship with their father, the coercion was particularly heart-breaking as their trusted parent changed:

“

‘When it came to marriage, I don’t know what happened to him. He just changed to another person, so it was a big shock for me. It was heart-breaking. He was out of control. It wasn’t my father that I used to know because he would listen to us, listen to our mother – he would ask her opinion more than anyone. Then suddenly he would not listen – not even tiny.’

The women described being subject to emotional and psychological duress. Usually this was from parents, however it could also come from siblings and from extended family. One woman noted the pressure she was under from her extended family who repeatedly taunted her with her delay in marrying and making her father wait.

“

‘[I] was really glad that I had friends I could share stuff with…just to vent it out…because the stress inside building those things – the thoughts – what will happen? Oh my God –this leads to too much going on – and just makes you…like a robot...constantly one part is doing things.’

In addition, the impact on their siblings could be seen as adding to the coercive burden or giving them strength to resist. A woman noted that the hardest part for her about this situation was that she has younger sisters who witnessed everything. Her sisters said to her ‘if you don’t stand up, he will do the same with us’.

Although pressure applied to the women was typically emotional and psychological, some were also subjected to physical abuse and confinement to convince them to submit. According to one woman, her parents were not ‘extremely physical’ because she was working, and they were worried that someone would see marks on her. She was worried for her physical safety and moved out of the family home to escape the pressure and emotional abuse.

“

‘I ended up losing more than anything else. I ended up losing them, I ended up losing my parents. I ended up losing so much more than I could have imagined.’

For some girls, the dislocation from family is about survival. For one of the women after months of emotional and physical abuse, matters reached a crisis, and her father told her that ‘you either have to follow or are no more my daughter and you have to leave the home’. This young woman did leave the home and was able to support herself financially. There were many more discussions with her parents and at one stage she was confined in her own home in Hong Kong by the family and beaten overnight. The words of her father continue to impact her. She shared that he had on occasion told her that he wished she was dead or that it was ‘better to have a dog than a daughter like you. They will obey but not you’.

Another woman who married at 16, had found out when she was in Form 3 that she was engaged to be married. Her older sister was already married, and she was to be married to the younger brother. Due to concerns from her brother-in-law about young people in Hong Kong being too rebellious, the decision was made by her parents that she would marry. She was under pressure from her mother and elder sister:

“

‘[My mum] said your elder sister is already there. We don’t want anything to happen to her…My mum tried to convince me. My dad was supportive because I was only in Form 4. Then they took us to Pakistan and got me and my elder sister married right away. I was forced. I wasn’t ready.’

As she notes, the duress was not only applied to her situation but also the risks for her sister were highlighted to her:

“

‘My sister was in his house. He had all the controls. He convinced my mum and then my dad, also my sister. My sister told me that if I don’t get married and now, she has to go to Pakistan with them, she would have a hard time.’

The application of pressure from extended family members and even the groom's family is a common theme amongst the women's experiences.

“

‘The woman who was the mother of the guy and the family members of the guy kept coming to ask me to marry him. Their son wants to go abroad…they don’t even question if I say no, they just want it to happen. They said that if the parents agree no one else can do anything.’

A common element of coercion is trickery. This can be in the form of using a trick to ensure a woman will travel to the family's country of origin or will return home. One woman explained that having lived apart from her family, at some stage her family told her that her father was ill and that she should go home to see him. When she arrived at the family home in Hong Kong, she was locked in a room for two days and the pressure escalated. She was able to escape when she came up with an excuse to leave the room and she took her chance and ran.

Sometime later her parents told her that they had accepted her decision. Due to her first marriage ending in divorce, she had to return to Pakistan to complete the divorce formalities and believing that things had calmed down she went with her family to Pakistan. She was able to find Pakistani lawyers to assist her with the divorce and was in contact with them.

At first everything was fine, however after a week, her father said she should give him her identity documents / passport for safekeeping. Later she realised her father was not going to return her identity documents. When she raised the need to return to work her parents escalated. They locked her up and abused her emotionally for a month and half and refused to take her to the doctor when she was unwell. Her health deteriorated, and yet she said:

“

‘I couldn’t even die. Because I didn’t want to die because I have a lot to live for and I don’t want to die because of them. They were of course wishing me death [because] it was better for me to die than for me not listening to them and marrying someone else not of their choosing.’

During this time in Pakistan, her parents continued to prepare for the wedding. She decided she needed to escape and return to Hong Kong. With the assistance of third parties, she was able to return to Hong Kong. When asked about who these third parties were, she did not want to disclose this information as they remain in Pakistan and continue to assist girls and women.

One woman warned that it is difficult to help girls who are being pressured as their parents will take their daughters out of Hong Kong for various reasons:

“

‘Then they pretend to be some kind of characters. ‘Father is unwell’ [or] ‘or mother is dying’. We need to do this. They know marriage without the daughter’s consent is invalid in Islam. So, they make the daughter say somehow ‘yes’.

Financial reasons can also lead to marriages earlier than the girls wish. One woman was expecting to marry one year later in line with the completion of her studies, however her parents asked her if she would marry a year early.

“

‘I have a lot of siblings. My parents were like ‘we cannot afford to have you married one by one, so it was like, it’s going to cost a lot. They asked me because my sister was getting married, if it’s okay to move the date from next year to this year instead…at first, I was confused because I’m studying, and I was like will that affect my studies?’

She did consider saying no due to her shock at the changed date. However, she noted that she discussed this with her father and eventually agreed to marry earlier than planned.

2.7 Why do the interviewees believe forced marriage happens?

Many of the women referred to tradition and custom in marriage as opposed to religion. The women agreed that their religion required consent from both parties. However, custom was seen as having very different standards. As one woman said that she didn’t agree with her parents who had brought her ‘to a foreign country and [brought] their own rules to this place from [their] hometown’.

One woman whose parents attempted to force her into marriage through emotional, psychological, and physical abuse, felt that her ‘parents [were] being forced by elders but parents don’t realise the damage they’re doing’. Her observation is that:

“

‘It’s about the system they created, and they wanted us to grow up in the system they created. I do think they were very afraid that the biggest reason is because [children] will go out of control but some people have hopes and dreams…other kids want to party and…then get married and have a traditional life. We were like no, we want to get out of poverty, and we wanted to create a different lifestyle and we wanted to give our parents a better life than we had…even today we still hope to bring them out of that whole poverty lifestyle.’

Her hope is that eventually her parents will understand that her resistance was not due to her being irresponsible or badly behaved, instead she wished for an education and career that would lift her and her parents out of poverty.

For a woman who was required to marry a friend of her father’s:

“

‘It felt strange to marry somebody who I didn’t know. My parents had told me about this person, but he had no education, unstable job and I wasn’t in love with him.’

She feels that her father:

“

‘Thought he was agreeing to his elders’ ideas about the boy and was happy to make others happy by ‘giving’ his daughter…[but] isn’t it natural to love your own children more than other [people’s] kids? He also knew I was the weak one emotionally, my sisters were not put up for this – only I was.’

Many of the women referenced traditional views of obedience to parents and in particular, fathers. One woman sought to explain to her father her thoughts:

“

‘What I believe – what is my faith – our religion doesn’t support that and no matter –early, or you’re an adult, you shouldn’t force anyone to get married.’

However, she said that her father responded that this was not about religion anymore, ‘it’s about our Pakistani culture, so we need to follow’. She acknowledged that she feels her father was as shocked as she was by his attitudes and behaviour. Their relationship had previously been supportive, and she acknowledges that it seemed as if even he could not understand his own reactions. She tried to explain to her father:

“

‘I cannot [marry]. I cannot risk my life. It’s about 40/50 years. If I have children with him, I need to make sure he will be a good father like you…I don’t want you to do this sin. I rather that God hates me [because] I disobey you, but I don’t want him…there will be a judgement day and you will say it’s a sin – why did you do that to your own daughter? I don’t want to see that day.’

She tried to compare her experience of being forced to her father’s experience as he had not chosen who to marry, however this made matters worse. The situation became extreme, and she attempted suicide twice.

“

‘I don’t want him to commit the sin, I don’t want people to look down on him. So, I think my dying will make his honour. Keep his honour then why not? I don’t want to give up on my life partner option. So, this will be better.’’

Her situation worsened after the attempts. She withdrew from her family and Hong Kong, although she has since returned. She continued to seek news and connection about her family. Her parents decided that her sister would marry the man chosen for her.

Although she had misgivings about the man, she decided not to say anything to her sister. Sadly, this marriage was abusive, and her sister faced a difficult time. By this stage her father had relented and was speaking with her. Her father’s instinct was to arrange a divorce for her sister; however, she asked him to support her sister:

“

Improving

‘Please don’t do the same mistake. I know you want to support her [the sister] but if she wants to get divorced, then you support her. But don’t make the decision for her.’

Another woman who was interviewed, she explained that:

“

‘They wanted to get rid of me so they wouldn’t have to spend money on me or my education. They wanted to concentrate on my brother. They saw it as they had finished their responsibility to me, and it was better she goes to her own home and is her husband’s responsibility.’

She spoke of her dreams as a very academic child. However, she explained that ‘my voice was never heard by my parents’.

2.8 What sustains them?

These women are extraordinary. Their capacity for understanding and forgiveness is exemplary. For some they were clear that their faith has sustained them. As one woman explained she sought guidance from Allah and in prayer to endure the pressure and to sustain herself.

As one woman who was held in Pakistan for a month and a half and subjected to emotional and physical abuse explained:

“

‘I’d rather be on my own and go through this on my own … because I was dying everyday with their words. I was having panic attacks, and I knew I will be dying. I said I’d rather die on my own than to die with them. Tomorrow God will question me [and say] ‘I gave you so many options, so many paths, you still didn’t take action’.’

Her faith in Allah meant that she believed she needed to resist forced marriage. For some this faith leads them to choose committing the sin of disobedience and even suicide rather than for their parents to sin by forcing them into marriage. She was also sustained by the reality of having younger sisters. Their potential future plight reinforced her will to reject the marriage. Knowing that if she gave in and consented that they would also be required to marry, perhaps against their will, strengthened her resolve.

For one young woman who was forced into marriage when she was 16, she made the decision to run away. On her return to Hong Kong from Pakistan after the marriage, her husband’s family wanted her to apply for a visa for her husband, however this did not happen as she had run away. She acknowledges if she had applied for the visa, ‘life would have been different’.

She was ‘scared about the consequences’ however she had help from her mother and younger sister to stay away from her extended family member who was trying to enforce the marriage. According to her ‘they were searching for me everywhere’.

She noted the help and support she received from the Hong Kong Police. She said the Police told her to go somewhere safe while they arranged a shelter and a social worker. Within the week she had moved into a

shelter and had a social worker assisting her. Despite this assistance, she noted that life in the shelter was ‘not easy’ as there was no ‘privacy’ and it was very lonely and difficult. At the age of 16 she was isolated from her family, her home, her community and her school environment.

Unusually in this case the pressure was not coming from her parents but from her husband’s family and this was echoed by the community who also made this difficult for her and her parents. After she ran away, she emphasised the importance of the support she felt from her mother and father.

“ So many people were pointing fingers. That’s why I had to stop studying…in our own society so many people were pointing fingers at me…even in my school… [my parents] fought with everyone to forgive me – all they wanted was for me to be happy.’

2.9 What would they wish to say to their families?

This question elicited strong responses from some of the women. For the young woman who had managed to escape being held in Pakistan, she wanted to ask her parents:

“

‘Why did you do this to me? I was always there whenever you needed me – physically, psychologically, financially I was the one who was providing for you. Why me? I think there’s also a lack of understanding between their mindset and my mindset. They always keep telling me your choice is wrong. So, if my choice is invalid, what about my feelings? If I ever get the chance to sit down and tell them, I will apologise. Maybe my steps are wrong, but I just had no options. I just choose myself over them.’

Reflecting on her own experience in marriage, one woman said:

“

‘Some things the mother has to teach their own child. Because they will be very harsh on their wives. I can’t change the things that are already there. What can I change? I can change my kids or focus on him [my husband]. I rather focus on my kids than focus on him. Some things – sometimes I just cry. I am doing so many things at the same time. Sometimes I really want to get good sleep, and no one touches me during sleep. No one wakes me up…I just want a break.’

For this woman, she has struggled to complete her tertiary education after being convinced to marry early due to family illness. She was told that a senior family member was ill, and that the marriage had to happen earlier so that they could be present.

For a woman who felt forced to marry, she explained that when she married, she experienced lots of changes and was disturbed.

“

‘I couldn’t sleep for a year. I was engaged for a year because my husband wasn’t ready. That year was very tough thinking about how will I adjust to this person? It took me almost 6-8 years to get him to understand. Since he came to Hong Kong, I’ve seen many changes in him. By seeing the environment, he’s really changed.’

However, she still feels that her voice and her thoughts and feelings were never heard or acknowledged by her parents.

For a young woman who married at 17, if she could speak freely to her father, in relation to her sisters, she would like to say:

“

‘They need to be more broadminded and think more faraway. They should look for a good match. Sometimes parents are committed from a very early age. Not in our family, I am glad my father is different from others…in my family we think we should marry amongst our cousins and if there is a future problem then the elders can help. My father thinks his family is best…even my mother’s relatives has good guys.’

Her wish is that her father could expand the circle of possible grooms outside his own nephews to those of her mother’s side of the family.

2.10 What advice would they give to someone who is being pressured to marry?

The personal experiences of each woman influenced the advice she thought would be helpful to other women who are being pressured to marry. For a woman who was financially independent and had been able to resist the marriage, she focused on personal responsibility:

“

‘I would really tell them that everyone is responsible for their own decision – so let them [your daughters] make their own decision...first try to convince your parents and explain...and if no, then you need to make a decision for yourself…I cannot tell you – I’m here for any decision you make, but I won’t make a decision for you.’

Another woman whose parents and husband are supportive of her education, highlighted rights. For girls who are being pressured to marry, she advised them to ‘hold up your rights…don’t just let them go’. She gave examples of women who are married not being given money by their husbands for themselves, ‘that is their right to have some earning from the husband for themselves’ and if they are being beaten, they should use their rights.

In terms of advice for someone who is being pressured into a forced marriage, one young woman had several ideas about how to approach this.

● ‘Writing it down can help you to construct thoughts and in a spiritual way talk to God, to Allah, he listens. Use this private reflection… to construct [your] thoughts.’