ZONING DIAGNOSTIC REPORT

CITY OF STOW, OHIO

JUNE 2022

This reporT was prepared by:

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Zoning codes have profound impacts on many important aspects of a community’s development and character, and, as such, the City of Stow commissioned this zoning diagnostic to evaluate the ways in which Stow’s existing zoning code promotes or interferes with the community’s stated objectives. Those objectives were: (a) promote clarity, efficiency, and consistency of the law and its administration; (b) promote environmental sustainability; (c) promote walkability; (d) maintain or increase the population base and housing options; (e) increase the commercial tax base; (f) promote the redevelopment of outmoded commercial strips; and (g) establish a community identity.

The project’s zoning consultants found that, of the listed community objectives, the existing code most effectively promotes environmental sustainability. Among the supporting provisions are floodplain and wetland protections, open space dedication mandates, stormwater controls, and purpose statements that emphasize the preservation of natural amenities.

The existing zoning code generally impedes clarity, efficiency, and consistency of the law and its administration. It lacks important definitions of terms and unnecessarily repeats some regulations, resulting in an unclear and inefficient code that may be difficult to administer and defend.

Other objectives are weakly promoted by the zoning code’s regulations, and others still are barely addressed. For example, the zoning

code includes few regulations that would yield an increased sense of community identity, such as development surrounding a town center, natural feature, or institution.

Following the analysis, a list of recommendations was generated that, if implemented, may help Stow better achieve its community objectives. Some important recommendations are as follows:

1. Eliminate off-street parking requirements, an action which may result in more efficient use of land, an improvement in stormwater quality and reduced flooding, and a more pedestrian-friendly environment.

2. Mandate front-yard tree planting, an action which may result in reduced heating and cooling energy demands, more absorption of stormwater and reduced flooding, increased greenspace in neighborhoods, more shaded pedestrian paths, and elevated property values.

3. Allow for neighborhood-scaled agricultural uses, an action which may result in greater resilience to unforeseen food import and distribution disruptions, increased greenspace, improved health of Stow residents through better nutrition and exercise, and enhanced local identity and pride.

4. Define all use terms, eliminate duplicative regulations, and include more graphics and tables to illustrate zoning code standards.

We hope that this zoning diagnostic provides an enlightening critique of the current zoning code’s regulations and, with the implementation of its recommendations, helps Stow achieve its vision for the future.

INTRODUCTION

Zoning regulations impact many aspects of a city, including the environment, housing availability, neighborhood character, greenspace and walkability, employment opportunities, and economic prosperity. Therefore, naturally, it is paramount to have an effective and efficient zoning code that guides development to achieve a community’s desired outcomes. This zoning analysis compares the zoning code of Stow, Ohio, against the community’s stated objectives summarizes the results.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES APPLIED

The rationale for conducting this analysis is based on three general principles:

Zoning should regulate only what needs to be regulated to protect health and safety.

First, zoning regulations should place limits on the use of land only when necessary to promote the general welfare. Regulations that do not relate to public interests, such as health and safety, may overstep the police power granted to cities and may not be legally defensible.

Zoning should respect both existing and desired development patterns.

Zoning regulations should relate to a community’s existing and desired development patterns. When regulations are out of context with existing or desired development patterns, land owners may need to apply for numerous administrative approvals and variances for

typical development projects, which increase the cost of investment in a community. Furthermore, processing such administrative approvals and variances can unduly burden government departments.

Zoning should be the implementation of a plan, not a barrier.

Zoning should be a tool to implement a community’s vision as expressed in its comprehensive plan. In many instances, a community invests time, funds, and energy into the development of a comprehensive plan, but zoning regulations are overlooked or revised over time in a disjointed manner. This scenario leads to outdated, inconsistent, and disorganized zoning regulations that are cumbersome, intimidating, and costly for property owners and administrators, alike, and impede planning goals and economic development. On the other hand, a comprehensive update to the zoning code within the long-term planning process allows for clear, usable, defensible, and consistent regulations that operate efficiently to protect the public’s interests and encourage desired outcomes.

METHODOLOGY

This analysis evaluates Stow’s existing zoning code and provides recommendations for amendments.

To that end, we reviewed the 2017 Comprehensive Plan Update. Through critical analysis of the comprehensive plan, general planning and zoning knowledge and expertise, and discussions with City staff,

seven community objectives were identified, as follows:

Objective A: Promote clarity, efficiency, and consistency of the law and its administration.

Objective B: Promote environmental sustainability.

Objective C: Promote walkability.

Objective D: Maintain or increase the population base and housing options.

Objective E: Increase the commercial tax base.

Objective F: Promote the redevelopment of outmoded commercial strips.

Objective G: Establish a community identity.

Following the identification of the community’s objectives, each of the zoning code’s provisions were evaluated against the objectives and were scored as either:

+ Promoting the objective;

! Interfering with the objective;

= Both promoting and interfering with the objective; or [blank]

Having no impact on achieving the objective.

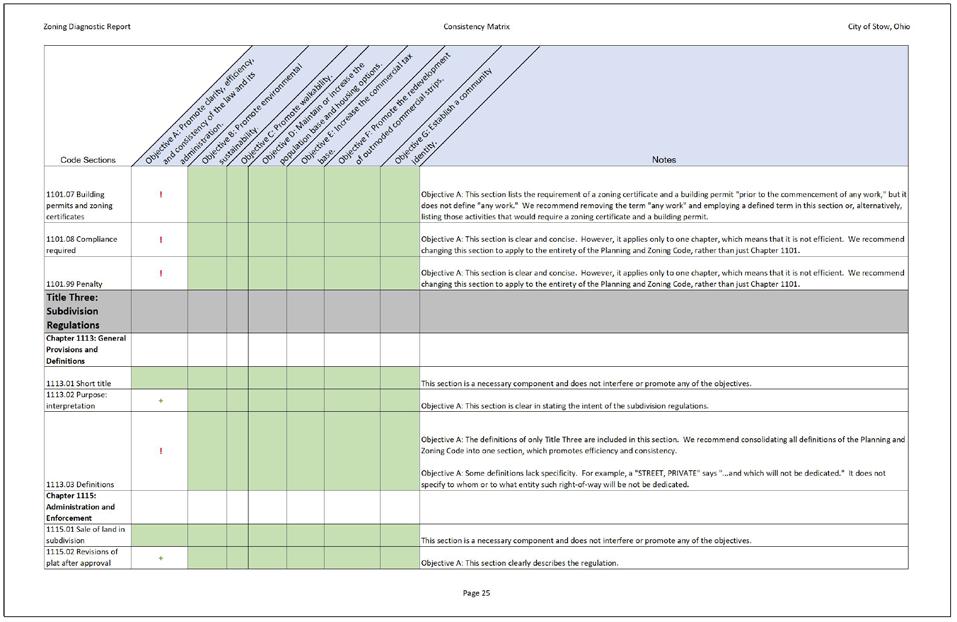

The results of each analysis were recorded and

are included in the Consistency Matrix at the end of this report. A summary of the analysis is provided in the Results section of this report.

Next, a conclusion and list of recommendations provide guidance for future amendments to Stow’s zoning code.

Figure 1. A snapshot of the Consistency Matrix, which can be found at the end of this report.

RESULTS

OBJECTIVE A: PROMOTE CLARITY, EFFICIENCY, AND CONSISTENCY OF THE LAW AND ITS ADMINISTRATION�

Background

A zoning code must be clear, efficient, and consistent.

Clarity: A clear code provides clear instructions to landowners about what is and what is not legal on their properties. It is predicable and has little risk in investing in land, structures, and businesses. A clear code is less reliant on

staff interpretations of the law and is therefore more legally defensible against claims of capriciousness.

Efficiency: An efficient code is quick to read and understand and is, likewise, democratic by nature. It uses tables, graphics, and charts to increase comprehension and eliminate long paragraphs. An efficient code is also easy to administer and does not require applicants of commonplace developments to suffer the costs of waiting for public hearings and committee reviews.

Consistency: A consistent code eliminates conflicting standards within zoning code and between the zoning code and other municipal, state, or federal regulations. It uses established use terms, staff titles, and formatting. A consistent code leads to a more consistent built environment and just application of the law.

This section of the report evaluates the clarity, efficiency, and consistency of Stow’s zoning code.

Scoring Summary (out of 290 evaluations)

88 5 165

Summary

Objective “A” scores poorly--clarity, efficiency, and consistency are not widely achieved by this code. The zoning code includes missing definitions, incomplete sentences, conflicting provisions, duplicative regulations, references that require flipping throughout the code, and

insufficient graphics. However, the zoning code does present many standards in table format, which improves usability.

Supportive Provisions

The zoning code promotes Objective “A” mainly through its use of tables. Tables present regulations, especially numeric regulations, in a space-efficient and easyto-use manner. Some examples include Section 1143.02, where the permitted uses of residential districts are presented in a succinct table; Section 1143.04, where minimum yard area requirements are displayed in a table; and Section 1160.05, where a table sets forth the development standards for the Gilbert Road Overlay District.

Interfering Provisions

There are many more examples where the code fails to achieve Objective “A.” Clarity is lost when the code uses terms that are not defined. For example, Section 1101.03 lists requirements for permits required “prior to actual construction,” but it does not define “actual construction.” In Section 1143.02, uses are listed for residential districts, but many of the uses are not defined. And, in Section 1145.06, it is noted that front yard setbacks of 40 feet must be provided on the side streets of corner lots, but “side street” is not defined in the code. Lack of defined terms may lead to confusion and mistaken nonconformity.

In other areas, clarity is lost due to word choice. In Section 1121.01, the code requires that “Subdivisions shall be planned to take advantage of the topography of the land…

reduce the amount of grading and to minimize the destruction of trees and topsoil.” However, the code does not specify by what methods and to what degree such environmental planning should occur. Likewise, in Section 1123.02, the code requires that “as many trees as possible shall be retained.” While this requirement encourages the preservation of trees, it does not specify how many trees constitute “as many trees as possible” and its effect is diminished.

The code also fails to achieve efficiency. In printed form, the code stretches 287 pages. This length is unnecessary. In many areas, the code repeats procedures and other regulations in each chapter. For example, Sections 1131.04 and 1131.05 direct the user and the administrator on how to interpret conflicts between the zoning code’s regulations and other municipal, state, or federal regulations and how to treat the code in the case that one provision is declared to be illegitimate; however, these sections apply only to Title Five rather than to the whole zoning code and, therefore, are repeated in other titles.

In other areas, the procedure for the approval of conditional uses and overlay districts are repeated in multiple chapters. For example, Sections 1151.09 (Darrow Road Overlay District) and 1153.08 (Planned Residential Development) are nearly identical. Sections for violations and penalties, as well as definitions, are repeated throughout the code, leading to inefficiencies.

Also contributing to its length, the code includes an excessive number of districts and overlay districts and lists nuanced use terms,

such as in Section 1145.02, where there are three listings for different types of restaurants and yet an additional listing for Bar, Tavern, Night Club.

Efficiency of administration of the code is also lacking due to the zoning code’s regulations, themselves. Section 1137.02 requires that a zoning certificate be issued only when a site plan has been approved by Council based on the recommendation of the Planning Commission. This requirement slows the zoning certificate approval as applicants must go through multiple hearings and public notice processes, even for those uses deemed “permitted.” When granting zoning certificates becomes too cumbersome, developers may look to develop outside of the city or may attempt to bypass the process and construct illegally without a permit.

Consistency also suffers in a couple of areas. Section 1163.04(l), for instance, lists requirements for retail establishments, restaurants, funeral homes, and studios, but then later says that the uses can be museums, art galleries, bed and breakfast uses, and veterinarians. And in Section 1121.05, the regulations permit inconsistency in lot sizes of subdivisions. Elsewhere, the tables are inconsistent in their setup, switching the districts’ locations along the x and y axes.

OBJECTIVE B: PROMOTE ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY�

Background

The comprehensive plan identifies the community’s aim to “Preserve significant natural areas, especially areas that provide scenic beauty and/or important natural stormwater management and water quality functions” (see Goal 8 on page 19 of the 2017 Comprehensive Plan Update). It also establishes Environmental Protection Policies and Strategies, such as “Expand the use of riparian and wetland setback requirements for all development...” and “Encourage the use of low impact development (LID) infrastructure stormwater controls in new development and redevelopment projects” (page 35). City staff, too, identified stormwater and flooding as a major issue for Stow residents and one that needs to be addressed.

While Stow is nearly completely built-out, with only a handful of undeveloped tracts,

Stow could achieve its goals with plentiful small preserves and ubiquitous stormwater infiltration best practices.

This section of the zoning diagnostic report evaluates Stow’s zoning code on its promotion of, or interference with, promoting environmental sustainability.

Scoring Summary (out of 290 evaluations) + ! = [blank] 44 22 1 223

Summary

Stow’s zoning ordinance includes many provisions that support environmental sustainability. In fact, Objective “B” scored higher in the analysis than any other objective. Still, the code includes many regulations that act to discourage environmental stewardship, and many zoning provisions found in peer cities’ codes that benefit the environment are missing altogether from Stow’s code.

Supportive Provisions

The provisions supporting Objective “B” in Stow’s code focus on the preservation of open space, soils, vegetation, floodplains, and natural topography. Some examples follow:

• Section 1123.02 requires the preservation of topsoil and the restoration of land and vegetation after construction. Topsoil acts to hold stormwater and increase infiltration, reducing flooding.

• Section 1123.05 directs subdividers to dedicate a minimum of 10% of the subdivided land for public sites, public parks, or public open space. And, in Section 1153,06, the code requires Planned Residential Developments to set aside 35% of the site as open space, preservation area, recreational area, or recreational facilities. Open space slows the runoff of stormwater, reduces stormwater volumes, and filters sediment from sheet flow.

• Section 1137.03 directs the Planning Commission to find that an application’s site plan “will preserve and be sensitive to the natural characteristics of the site.”

• At least 25% of commercial lots must be landscaped (Section 1145.10). Landscaped area may help absorb precipitation and limit stormwater from leaving the site.

• Some purpose statements include mention of environmental topics, including the purpose statement of the Mud Brook Watershed Stream and Wetland Setback Overlay District (Section 1155.01), which seeks to preserve water quality within streams and wetlands; the purpose statement of the Planned Residential Development (Section 1153.01), which aims to conserve natural amenities and green spaces within developments; and the purpose statement of the Planned Unit Developments, which mentions the preservation of woodlands, water bodies, and other natural features (Section 1167.01).

• The Mud Brook Watershed Stream and Wetland Setback Overlay District requires wetland setbacks that will help protect habitat, preserve water quality, and reduce flash flooding effects (Section 1155.06).

The provision that most supports Objective “B” is Section 1185.01(e), which requires that the volume of stormwater draining from a site should not exceed that which occurs under natural land cover conditions.

Interfering Provisions

While there are many provisions that aim to protect topsoil, trees, ground cover, floodplains, and natural topography, there are others that interfere with environmental sustainability.

• Most importantly, the off-street parking, waiting space, and loading space requirements (Sections 1181.03, 1181.06, and 1181.08, respectively) mandate that all land uses in Stow provide areas of paved vehicle use areas, greatly contributing to stormwater discharge volumes, temperatures, and flows, damaging the environment and contributing to flooding issues. Furthermore, these requirements make complying with Section 1185.01(e)--which prohibits the discharge of stormwater in excess of that which would occur under natural land cover conditions--difficult or impossible.

• By limiting floor area ratios (to, for example, 25% in the RB District)

and building coverage (20-25% in commercial districts), the code promotes low-intensity uses that require more impervious surface and produce more stormwater effluent per gross floor area of building.

• Stow’s code includes provisions that make single-family dwellings less cumbersome to permit and build than other types of dwellings, which are limited in their placement and require additional reviews and site plans. Prioritizing single-family dwellings over other types of dwellings may negatively impact the environment, as single-family dwellings may generate more impervious surface per unit and consume more energy to heat and cool per unit, on average.

There are other provisions that do not go far enough to achieve environmental sustainability. Some examples are as follows:

• Section 1143.02 lists cluster developments as conditional in the R-1, R-2, and R-3 Districts. Conditional uses (as opposed to permitted uses) may discourage the development of cluster developments, which can preserve tree canopy cover and wetland soils.

• Section 1121.06 encourages the preservation of outstanding natural features, but encouragement, not requirement, may not be enough to achieve Objective “B.”

Lastly, there are provisions that are missing

from Stow’s code that, if adopted, could support Objective “B.” Examples of missing provisions include:

• Impervious surface coverage. The code regulates floor area ratio, percent building coverage, total building cover, and minimum dwelling unit size, which may lead to sprawl and increased stormwater effluent per person. The code fails to include limits on impervious surface coverage, which would address stormwater and flooding issues directly.

• Adequate set asides for open space. Section 1123.05 directs subdividers to dedicate a minimum of 10% of the subdivided land for public sites, public parks, or public open space, but 10% is insufficient to mitigate the stormwater impacts of development.

• Purpose statements. Section 1151.01 does not include environmental sustainability in the purpose statement for the Darrow Road Overlay Districts.

• Approval criteria. Section 1157.03 sets forth the criteria by which the Planning Commission and Council must review an application for a Planned Industrial Development, but it does not include environmental sustainability or stormwater pollution mitigation. Likewise, Section 1153.03 fails to list environmental sustainability or stormwater in the approval criteria for a Planned Residential Development.

• Electric car charging. The code does not include electric car charging as a

permitted accessory use.

• Permeable pavement. The code does not include provisions that permit or encourage permeable pavement.

• Renewable electricity generation. The code does not expressly permit photovoltaic cells or household-scale wind turbines.

• Local food systems. Gardens and livestock husbandry are not addressed by Stow’s code.

OBJECTIVE C: PROMOTE WALKABILITY�

Background

Walkable neighborhoods are important for many reasons. First, they promote public health and encourage active lifestyles. While there are many factors that affect weight, several studies identify an inverse relationship between walkability and obesity.1

Walkable neighborhoods also encourage a sense of community--neighbors spend more time in the public realm, passing each other, starting conversations, building relationships, and developing a sense of belonging. Elizabeth Brown, in the Thriving Cities Blog,2 claims that “Walking allows us to establish a place-based

1 As example, see: Stowe, Ellen W., S. Morgan Hughey, Shirelle H. Hallum, and Andrew T. Kaczynski. 2019. Associations Between Walkability and Youth Obesity: Differences by Urbanicity. Childhood Obesity. Dec 2019. 555-559.

2 Brown, Elizabeth. 2017. Walkability and the Thriving City. Smart Growth Online.

connection with our community, to educate ourselves with our surroundings, and inform ourselves of the history of our place—benefits largely absent during driving. Furthermore, walking facilitates social interaction and allows citizens to establish a familiarity with fellow community members that can strengthen a sense of place and belonging to one’s community.” Walkability is, therefore, an important component in achieving Objective “G,” establishing a community identity.

Lastly, because walkability improves the quality of life, properties in walkable areas maintain their values, and may result in safer-and more--investments. JLL, a global firm specializing in real estate services, published an article claiming that “[walkability] strongly correlates with an increase in property values, rents, retail sales, occupancy, absorption and price resilience in downturns.”3

Stow’s 2017 Comprehensive Plan Update identified walkability as a community objective (see Goals 4 and 7 on page 18). Its Transportation and Connectivity Policies and Strategies section includes “Support and promote non-motorized transportation modes...” Likewise, the plan observes that pedestrian safety is a primary concern for many Stow residents (see page 36).

Scoring Summary (out of 290 evaluations) + ! = [blank] 18 30 2 240

3 Boyar, J. 2021. Walkability: why it is important to your CRE property value. JLL Online.

Summary

Stow’s zoning code inadequately promotes walkability. In some instances in the analysis, provisions were highlighted as potentially enhancing the pedestrian experience, such as through required landscaping, screening of refuse storage, and front setbacks for buildings and parking areas. However, many more provisions render walking in Stow unpleasant, unsafe, or impossible.

Supportive Provisions

The pedestrian experience benefits from provisions that enhance the aesthetic appeal of a district. For instance, Section 1158.06 requires landscaping and screening of outdoor storage in the Seasons Road Overlay District; Section 1160.06 requires screening and landscaping around parking areas in the Gilbert Road Overlay District; and Section 1163.04 requires screening around refuse storage in the R-B District. Furthermore, design standards for commercial districts improve aesthetics and encourage pedestrianism (Section 1182.03). And Section 1185.04 requires the maintenance of structures, which, if enforced, could provide for a more pleasant walk.

Connections between sidewalks and neighborhoods is critical. One provision requires pedestrian connectivity: each proposed development in the Stow-Kent Overlay District shall provide for pedestrian connectivity within the development and through the development (Section 1159.07). Another provision--Section 1185.01(h)-requires that sidewalks be constructed along the entire public street frontage for

property that is being built upon; however, this provision fails to require sidewalks along the entire street frontage of any new street, regardless of whether the property is being built upon.

Interfering Provisions

Many more provisions make walking difficult or impossible in Stow’s neighborhoods. By encouraging automobile use, the zoning code makes walking less safe and less desirable. Some examples include:

• Most importantly, Section 1181.03 sets forth the minimum number of parking spaces per land use, including 2.5 spaces per dwelling unit for several types of dwellings. An oversupply of parking induces vehicle use, resulting in more dangerous spaces for pedestrians.

• The code mandates that parking and loading areas have access drives of at least 35 feet in width, which requires pedestrians to dangerously cross over wide access drives as they pass on the sidewalk (Section 1181.09).

• In the classification of streets, only vehicle behavior is considered; pedestrians are not included as a target user (Section 1121.02).

• The subdivision regulations require the rounding of corners at intersections by 30-foot radii for major arterial thoroughfares, collector streets, and industrial streets, which reduces the

walkability of an area by allowing vehicles to make high-speed turns and by requiring long pedestrian crossing distances (Section 1121.02).

• Block lengths are required to be at least 800 feet in length, which encourages vehicles to speed and endangers pedestrians (Section 1121.04).

Furthermore, all of Stow’s provisions that encourage automobile use have secondary effects of proliferating the vehicle’s dominance of the landscape. A pedestrian, surrounded by roadways, curb cuts, and parking lots, may ask, “Am I the only one not in a car?” Vehicle dominance of the landscape erodes a culture of walking.

• Section 1181.03 requires an excessive amount of off-street parking; more vehicle use areas on the landscape translates to weaker walking culture.

• Parking in the front yard is not prohibited altogether (Section 1181.05). It is only prohibited in the required landscaped area of the front, side, and rear yards. Allowing parking in front of buildings is a detriment to the pedestrian experience.

• Banks, drive-thru restaurants, and other service windows must provide at least 5 off-street vehicle waiting spaces, and automatic car wash facilities are required to provide at least 25 offstreet vehicle waiting spaces. This space dedicated to vehicle use is greatly out of proportion with the space required for pedestrian use (Section 1181.06).

Long distances between destinations-whether a neighbor’s home, a workplace, or a cafe--means that walking as a mode of transportation may not be desirable or possible.

• Section 1121.05 prohibits access from a major arterial thoroughfare across a reserve strip and to a subdivision. This regulation limits walkability because it prevents residents of a subdivision from walking (via a right of access) to the thoroughfare and visiting its commercial amenities.

• Section 1145.05 limits the maximum floor area ration to 25-40% in commercial districts. This limitation, especially at 25% in the C-2 district (neighborhood commercial uses), eliminates the possibility of a multistory commercial use, and it requires that lots are large in comparison to the structure, which may increase walking distances between commercial structures, making walking difficult or impossible.

• Section 1145.06 requires deep front yards for commercial districts. While deep front yards may increase stormwater infiltration, they also encourage front yard parking and increase the distance between the sidewalk and the entrances of buildings, decreasing walkability in Stow.

• Section 1151.06 requires that lots in the Darrow Road Overlay District-1 have 30,000 square feet minimum and lots in the Darrow Road Overlay District-2

have 2 acres minimum. These minimums reduce the walkability of Stow by requiring business uses to be spaced out along the corridor, making walking to destinations impractical or impossible.

• Planned Unit Developments are instructed to discourage through traffic, which may discourage connectivity and, therefore, walkability (Section 1167.05).

OBJECTIVE D: MAINTAIN OR INCREASE THE POPULATION BASE AND HOUSING OPTIONS�

Background

The 2017 Comprehensive Plan Update identifies the goal of retaining existing and attracting new residents to increase the population base (page 18). To accomplish this goal, the plan points to provisions that encourage a variety of housing choices, compatible with the surrounding development, and ensure continued investment in neighborhoods.

Housing diversity is important to maintaining a population base: young professionals and older households have different housing needs and preferences than families with young children (page 29); denser residential development adjacent to retail could boost commercial activity and encourage walkability; senior housing options could allow older Stow residents to age-in-town (page 31).

To achieve Objective “D” over the long-term, housing must be high quality: new dwellings

should incorporate high quality design and materials, and existing housing should be properly maintained (page 30-31).

Scoring Summary (out of 290 evaluations) + ! = [blank] 13 16 1 260

Summary

Many of the code’s provisions interfere with achieving Objective “D.” Housing diversity is unlikely to be accomplished, as singlefamily dwellings are the only form of housing permitted without the implementation of overlays and planned developments.

Supportive Provisions

While few provisions support Objective “D,” some development types and overlay districts offer flexibility in housing type and arrangement. For example:

• The Planned Residential Development allows for many permitted housing types, despite a restrictive residential density limit (Section 1153.04).

• The Stow-Kent Overlay District, too, permits many types of dwellings (Section 1159.04).

• Many types of dwellings are permitted in the R-2, R-3, and C-7 Districts as conditional uses (Sections 1169.03 and 1171.03).

• Section 1171.07 allows for increases in residential density with the addition of

a major recreation facility.

Other provisions require neighborhood amenities that could improve the quality and desirability of nearby housing. For instance, Section 1185.03 requires that developers dedicate 10% of the gross acreage of a “proposed cluster development, planned unit development, multi-family development, or planned residential development to the City for park, playground, or open space purposes.”

Interfering Provisions

Many more provisions interfere with Objective “D.” First, single-family dwellings are prioritized over any other dwelling type.

• In base residential districts, singlefamily dwellings are permitted by right, whereas other types of dwellings are conditionally permitted (Section 1143.02).

• Off-street parking requirements mandate only 2 spaces per unit for single-family and two-family dwellings, but require 2.5 spaces per unit for townhouses and apartments (Section 1181.03). This regulation prioritizes single-family and two-family dwellings over other dwelling types, as singlefamily and two-family dwellings can be constructed with less costly parking per unit.

Second, the code requires large lots and limits residential density, which could result in more expensive and less diverse housing options. Some examples follow:

• Lots in the R-1 District must be a minimum of 20,000 square feet. In the R-3 District, which conditionally permits multi-family dwellings, lots must be 12,000 square feet (Section 1143.03), but density is limited to 6 units per acre and buildings may not exceed 35 feet in height (Section 1169.05).

• The code effectively bans efficiency units, as it requires dwelling units to be at least 960 square feet, except in apartments, where 500 square feet is permitted (Section 1169.05).

Finally, while the comprehensive plan illustrates the need for senior-friendly dwellings, the code does not permit assisted living facilities, nursing homes, or family or group homes for handicapped persons by right in any residential district (Section 1143.02) or commercial district (Section 1145.02). Furthermore, Section 1163.04(b) makes the conditional use approval of a family home for handicapped persons effectively impossible.

OBJECTIVE E: INCREASE THE COMMERCIAL TAX BASE�

Figure 3. An image of warehousing, a potential light industrial use that could support the commercial tax base in Stow.

Background

The 2017 Comprehensive Plan Update identifies increasing the tax base as a key objective. It calls for the maximization of the Route 8 corridor by attracting quality office and light industrial development in suitable locations (page 18).

Commercial uses are particularly important for the economic sustainability of Stow. More employment results in higher tax revenues and improved city services.

The amount of income taxes collected is more than double the property taxes, and the amount of withholding...makes up more than two-thirds of all income tax revenue collected. (Page 16 of the Comprehensive Plan)

Scoring Summary (out of 290 evaluations) + ! = [blank] 7 23 1 259

Summary

The zoning code does little to actively support Objective “E.” In many situations, the code presents hurdles that may limit the success of businesses.

Supportive Provisions

Most provisions that encourage commercial activity and the resulting increase in commercial tax base relate to purpose statements. Some examples include:

• The purpose statement for commercial districts aims to protect commercial uses and lands (Section 1145.01).

• The purpose statement of the Seasons Road Overlay District includes supporting the development of high quality office and light industrial uses and promoting economical and efficient use of land (Section 1159.01).

• Section 1159.01 states the purpose of the Stow-Kent Overlay District as offering a greater choice of living environments and commercial activities.

• The purpose of the Minimum Floodplain Requirements chapter includes the protection of the tax base (Section 1189.01).

Additionally, the ability to share off-street

parking with adjacent uses that operate during different hours (Section 1181.04) may reduce commercial overhead costs and allow for expansion and increased employment taxes.

Interfering Provisions

The code hinders the success of Objective “E” by limiting commercial densities and limiting commercial uses.

First, commercial densities are limited by the code through maximum gross floor area, maximum floor area ratio, minimum setbacks, and minimum parking requirements.

• Section 1145.04 requires that lots in the C-2 and C-3 Districts have a minimum of 20,000 and 40,000 square feet, respectively, impairing small enterprises from taking root in Stow and contributing to a flourishing business scene.

• Section 1145.05 limits maximum building coverage to 20-25% in commercial districts and maximum floor area ratios to 25-40%. The floor area ratio is even more heavily capped at 20% in the Darrow Road Overlay District-1 (Section 1151.07). Such limits force business owners to purchase lots that are much larger than their needs and could result in less investment in Stow, as such businesses may opt to purchase smaller, more affordable lots in neighboring cities.

• Section 1181.03 sets forth the minimum number of parking spaces per land use. Because commercial uses must supply

large areas of expensive parking and access drives (Section 1181.09), profits are diminished and potential growth is hindered.

• Section 1181.10 requires each parking spot to be 10 feet by 20 feet. This size, while typical, increases the area required for parking lots, and increases the cost of doing business, limiting the commercial tax revenues of the City.

Second, commercial use types are limited, impairing the potential growth of businesses.

• About half of the uses listed in chapter 1145.02 for commercial districts are conditionally permitted uses. Conditional uses and their associated public hearings increase the risk of development and the costs of doing business in Stow.

• Only three light industrial uses and zero heavy industrial uses are permitted by right in the I-1 District (Section 1147.02).

Additionally, the code sets forth criteria by which the Planning Commission and Council must review an application for a Planned Industrial Development, but it does not include commercial tax revenues (Section 1157.03).

Lastly, some provisions lead to higher governmental spending, which has the same impact as lowering tax revenues. For instance, Section 1121.02 requires large street widths, which leads to higher road maintenance costs. Wide residential lots, as required by Section 1143.03, equate to higher governmental costs

per resident for police, school, garbage, sewer, and other public services.

OBJECTIVE F: PROMOTE THE REDEVELOPMENT OF OUTMODED COMMERCIAL STRIPS�

Background

The 2017 Comprehensive Plan Update emphasizes the need for commercial areas to retain their competitiveness, viability, and vitality. Key to this competitiveness is the redevelopment of shopping centers that are experiencing higher-than-typical vacancy rates, obsolescence, and lack of investment.

The plan calls for reducing the minimum parking standards and reactivating large parking lots as a gathering space for temporary events such as pop-up festivals, art galleries, and farmers markets (pages 25-27). It also emphasizes design standards as important in the redevelopment of commercial centers (page 27).

Objective “F” relates to promoting walkability (Objective “C”) and promoting housing options (Objective “D”). If denser housing surrounds a commercial centers, for instance, there could be more residents within walking distance, resulting in increased sales.

Scoring Summary (out of 290 evaluations)

Summary

Through caps on density, limited permitted uses, high parking minimums, and poor pedestrian services, the code performs poorly in promoting a reimagination of failing strip malls.

Supportive Provisions

The code does set forth some regulations that promote the success of commercial centers. For example, Section 1145.01 includes protecting commercial uses without inducing commercial sprawl as a purpose of the Commercial Districts chapter, and Section 1182.03 introduces design and lighting standards in order to elevate the quality of commercial areas.

The code requires off-street parking, which could affect the ability of commercial uses to redevelop; however, the code incorporates requirements for parking area landscaping and screening which could elevate the design of such shopping centers. Furthermore, the code offers some respite from the parking requirements by permitting shared parking (Section 1181.04).

Interfering Provisions

The code hinders the achievement of Objective “F” through caps on density, limited permitted uses, high parking minimums, and poor pedestrian services.

Low density is a main concern. In Section 1143.10(a-b), the code limits new business development in the RB District to 25% floor area ratio and 3,000 square feet per lot. In

commercial districts, building coverage is capped at 20-25%, and maximum floor area ratios are 25-40% (Section 1145.05). This low density may reduce the viability of investing in a commercial space, as investors may not be able to recoup expenses.

Another issue interfering with Objective “F” is the permitted use list. The code places tight controls on the uses allowed in commercial areas. Section 1145.02, for example, lists about half of all commercial district uses as conditionally permitted. Conditional uses may deter investment, as entrepreneurs are faced with the risk of disapproval and the expense of waiting for multiple public hearings.

Even when a use is permitted, the code makes it difficult to change the use of a property. For instance, each use requires a different number of off-street parking spaces (Section 1181.03); if a change of use requires additional parking spaces, and no additional room exists on the lot on which to construct such parking spaces, the use will not be conforming. Furthermore, for conditional commercial uses, Section 1163.03 sets forth different area, width, and yard regulations for each use, making changing uses illegal in some cases. As an example, a retail establishment that is conducted on its minimum lot area of 16,000 square feet could not be redeveloped into a restaurant, as a restaurant (with table service) requires a minimum lot size of 20,000 square feet.

Another deterrent to achieving Objective “F” is minimum parking requirements. Minimum off-street parking encourages strip-style commercial areas. Section 1181.03 sets forth parking minimums, which require vast

expanses of parking that may exceed the principal use area. For example, restaurants require one parking space (300 square feet when including the drive aisle) per 50 square feet of floor area.

To exacerbate the issues caused by parking minimums, the code promotes front yard parking characteristic of strip malls. In the Stow-Kent Overlay District, for example, a building must be set back 80 feet from the front lot line; however, parking areas must be set back 20 feet from the front lot line, permitting--and, perhaps, encouraging--the positioning of parking in front of the principal building (Section 1159.06).

OBJECTIVE G: ESTABLISH A COMMUNITY IDENTITY�

Background

Goal #4 of the 2017 Comprehensive Plan Update sets out to “Encourage walkable, pedestrian-friendly mixed use development in strategic locations, such as the Stow City Center...” It continues to illustrate the community’s desire for a focal point of the city:

Redevelopment of the [City Center] is a high priority for the City of Stow. This has been the designated spot for Stow’s “downtown” central city for years. In addition, the public has shown support fro three specific centralized amenities: a public gathering/green space; a community recreation center; and an outdoor lifestyle/mixed use center. (Page 53)

The Stow City Center is an attempt to create a space that is “uniquely Stow” (page 54). Objective “G” expands on this idea: to establish, through the built environment, a defined identity of Stow. Peer communities have defined themselves by highlighting iconic historical structures, encouraging a unique tourism cluster (e.g., Amish-owned businesses), or connecting the town to a natural asset (e.g., pedestrian paths along the river).

Scoring Summary (out of 290 evaluations) + ! = [blank] 4 4 0 282

Summary

Stow’s zoning code does little to address the development of a community identity. The code instead requires most land to be used for low density suburban residential and office uses, and supports a landscape dominated by vehicle use areas. High-density, pedestrianfriendly, mixed-use areas in strategic locations that could support a community identity are not permitted, let alone encouraged, by this code.

Supportive Provisions

Chapter 1355 of the Codified Ordinances of Stow (not the zoning code) sets forth policy on historic preservation. Historic preservation is important in establishing a community identity, as it roots a community in a narrative told by the built environment.

Historic preservation is supported in the

zoning code in Section 1151.07, where the density in the Darrow Road Overlay District is permitted to increase when projects are designed in accordance with the Historic Preservation Design Guidelines.

Additionally, mixed uses are permitted by some overlay districts. For instance, the Darrow Road Overlay District, which overlays R-2, R-3, and R-B Districts, allows for offices, funeral homes, museums, hair salons, florists, and more.

Lastly, some provisions require developments to set aside land as public use areas. For instance, Section 1123.05 directs subdivisions to dedicate 10% of the subdivided land to public sites, public parks, or public open spaces. These areas could encourage the establishment of a community identity, even if just for a small neighborhood. Section 1185.01 requires sidewalks to be constructed where property is developed, which could boost pedestrian activity and neighborly relations. Other areas, still, are protected due to their location in a floodplain or wetland, which could emphasize a community identity of greenery and open space.

Interfering Provisions

The code largely fails to address community identity altogether. There is no mention of a special use area surrounding a historic structure cluster, nor a special entertainment district in the center of town or adjacent to a natural asset. As an example, Stow includes a boundary with the Cuyahoga River, but, while a multi-use recreational trail exists, the code does little to capitalize on the riverine area

with a dense, mixed-use neighborhood that draws visitors from neighboring communities.

Other provisions actively work against creating a community identity. Large minimum setbacks, low maximum densities, a short list of permitted uses, and high minimum parking requirements hinder Objective “G” in that they promote the dominance of detached, singlefamily homes and unwalkable neighborhoods, qualities that are hardly unique to Stow.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the zoning code includes some provisions that promote the objectives, but, overall, it stifles the achievement of the community’s goals.

The zoning code struggles most with Objective “A” to promote clarity, efficiency, and consistency of the law and its administration. From missing definitions of terms to ambiguities to repeated regulations, the code is unclear and inefficient and could be difficult to administer and defend. However, the code does achieve some efficiency in its use of tables and graphics.

The analysis returned the best scores for Objective “B”: support environmental sustainability. The code includes floodplain and wetland protections, mandated open space, stormwater controls, and purpose statements that emphasize the preservation of natural amenities. There are, however, provisions that work against the environment, such as low floor area ratios, mandatory offstreet parking, and hurdles to certain types of more environmentally sustainable residential

development. Additionally, the code misses opportunities for provisions that encourage renewable energy, food systems resilience, and lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Stow’s zoning code inadequately promotes Objective “C”: walkability. Landscaping provisions such as front setbacks, minimum yards, and screening of refuse storage help to improve the aesthetics and make for an enhanced pedestrian experience. However most provisions encouraged a built environment that is unpleasant or dangerous for pedestrians, such as heavy emphasis on vehicle use areas, dispersed development patterns, and single-use neighborhoods.

Objective “D,” maintain or increase the population base and housing diversity, is not supported by Stow’s zoning code. The code includes minimum residential unit sizes, deep minimum setbacks, and high minimum parking requirements that increase housing costs and decrease housing diversity. Furthermore, several housing types, such as those other than single-family detached housing, nursing homes, and assisted living facilities, are not permitted by right in any base district and are subject to cumbersome administrative procedures, discouraging their development.

The code does not support Objective “E,” the expansion of the commercial tax base. It limits commercial densities through maximum gross floor area, maximum floor area ratio, minimum setbacks, and minimum parking requirements, which could deter new businesses from investing in Stow or stifle growth and expansion of existing businesses.

Similarly, the code permits few business use types by right, restricting the pool of potential new enterprises in Stow.

Objective “F” is supported through some design and lot standards, such as landscaping and screening requirements, which could enhance commercial strips. However, limited floor area ratios, limited gross floor areas, limited building heights, limited uses, deep minimum setbacks, and high minimum parking minimums all deter redevelopment of commercial nodes, as investors may not be able to develop at densities necessary for a profitable return on investment.

Finally, the zoning code does not address the establishment of a community identity, Objective “G.” Mixed-use areas are sparse, and those that exist do not allow for densities that support a walkable “downtown.” The code also fails to establish a focus on a natural amenity, such as the Cuyahoga River, a stream, or lake, a business cluster, a historical icon, or a tourism attraction.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on our conclusions, we recommend amending the zoning code to (in order of importance):

• Reduce or eliminate parking minimums, loading area minimums, waiting vehicle space minimums, and access drive widths. Furthermore, require that all parking be located to the side or rear of the principal structure, and reduce or eliminate the minimum parking space dimensions.

This amendment will reduce stormwater issues (Objective “B”), reduce heat island effects (Objective “B”), promote walkability (Objective “C”), decrease housing costs (Objective “D”), decrease business overhead and boost profits (Objective “E”), allow for the redevelopment of parking lots in outmoded commercial strips (Objective “F”), and foster a community identity that is not focused on vehicle use areas (Objective “G”).

• Permit more uses by right, allow the administrator to determine if a proposed unlisted use is similar to a listed use, and allow the administrator to grant zoning certificates for permitted uses. This amendment would improve efficiency (Objective “A”), allow for more diverse housing options (Objective “D”), draw business investment (Objective “E”), enable commercial strips to be redeveloped as walkable mixed-use centers (Objective “F”), and develop Stow’s focal point (Objective “G”).

• Regulate impervious coverage rather than maximum building coverage and maximum floor area ratio, in order to more directly address stormwater and flooding issues (Objective “B”).

• Apply consistent dimensional standards for all uses within a district to allow for seamless adaptive reuse of properties (Objectives “D,” “E,” and “F”).

• Reduce minimum residential setbacks and minimum dwelling unit sizes to

allow for greater walkability (Objective “C”) and housing diversity and affordability (Objective “D”).

• Reduce minimum commercial building setbacks and lot sizes and allow for heights of at least 42 feet to allow for denser business development (Objective “E”).

• Clearly define all criteria for approval and disapproval of site plans and subdivision plats (Objective “A”). This amendment should increase predictability and defensibility.

• Allow cluster developments by right in all districts. This amendment will streamline administrative procedures (Objective “A”) and result in more greenspace and stormwater infiltration area (Objective “B”) and increased housing diversity (Objective “D”).

• Allow for neighborhood-scaled agriculture uses (Objective “D”).

• Allow for renewable energy generation (Objective “D”).

• Mandate a minimum number of street trees be planted determined by the linear feet of street frontage of a property. This amendment would decrease stormwater, flooding, and heat island effect issues (Objective “B”) and increase the beauty of an area and enhance walkability (Objective “C”).

• Reduce minimum turning radii, reduce minimum block lengths on new streets, and increase the minimum sidewalk width to 5 feet, which will increase walkability (Objective “C”).

• Remove content-based regulations on signs (Objective “A”). Allow the administrator to make sign area determinations (Objective “A”).

• Incorporate overlay districts into underlying districts, and consolidate districts to 12 or fewer (Objective “A”).

• Remove reference to specific uses and densities within purpose statements of districts (Objective “A” and “D”).

• Define all use terms, display all uses in one comprehensive use table, and include all use terms in one glossary chapter (Objective “A”).

• Remove duplication of procedures and administrative language, such as penalties, violations, severability, and approvals; consolidate such administrative sections into one chapter (Objective “A”).

• Increase the use of diagrams and graphics to improve ease-of-use (Objective “A”).

• Use strong verbs, such as shall or must, and avoid terms such as encourage, should, or may (Objective “A”).

• Employ gender-neutral pronouns for all references to individuals (Objective “A”).

• Use complete phrases, except in tables (Objective “A”).

• Allow for electronic submission of required zoning certificate applications (Objective “A”).

• Remove the chapter on satellite dish

regulations to streamline the code (Objective “A”).

Other specific comments and recommendations can be found in the Notes column of the Consistency Matrix.

CONSISTENCY MATRIX

The consistency matrix provides an assessment of the consistency of each provision with the objectives. It is included as an addendum to this report.