Zoning Diagnostic Report

Twinsburg OH

JUNE 2023

Engaging ZoneCo does not form an attorneyclient relationship and, as such, the protections of the attorney-client relationship do not apply. If you wish to create an attorney-client relationship, you are encouraged to contact an attorney of your choosing.

Executive Summary

The zoning code is a critical tool for supporting and encouraging the built environment that Twinsburg desires. Zoning significantly affects where people can or cannot live, find food, own land, start businesses, raise children, age in place, find employment, and seek education, among other pursuits of happiness. Although they may have celebrated features and beneficial intentions:

Zoning codes are only as good as the outcomes they produce.

Our analysis of the Twinsburg zoning code uncovered several substantive opportunities:

• Objective A: Best practices regarding stormwater management, solar energy collection systems, the ecological footprint of building materials, and creation of multi-modal pathways can be incorporated to align the zoning ordinance with land-use-related goals in the 2021 Sustainability Plan.

• Objective B: Time-consuming hurdles can be adjusted or removed to support adaptive reuse and rehabilitation of existing investments in Twinsburg. Similar to Objective E, use permissions, dimensional requirements, and parking standards can be clarified and simplified to make desired investments in Twinsburg easier.

• Objective C: Additional housing opportunities can open up incremental changes to established neighborhoods that have multi-faceted benefits of helping aging households downsize in place, meeting the preferences and needs of a wider diversity of households, raising property values, supporting affordability of properties, and creating fine-grained housing opportunities closer to businesses and employment opportunities in Twinsburg.

• Objective D: Use permissions, parking standards, and dimensional requirements that apply to the C-5 district (Downtown Twinsburg) can be adjusted to support a walkable, mixed-use environment anchored around the Square.

• Objective E: Decision making criteria and other standards can be revised so that they are clear, objective, and measurable – in turn, empowering professional staff to review proposed investments into Twinsburg that clearly meet plainly stated standards. Several parts of the ordinance can be more concisely and consistently organized to improve user friendliness and administrative efficiency.

This report marks the beginning of the process for identifying and overcoming shortfalls in the existing zoning ordinance. For Twinsburg’s consideration, this report is intended to illustrate opportunities that will improve the regulatory landscape established by the zoning ordinance in alignment with the city’s adopted vision and goals.

Decisions on the scope and content of revisions are ultimately in the hands of the City Council and the electorate. The considerations written here are subject to change as the project progresses. We present this report as a means of engaging the community to gather input and develop meaningful and desirable revisions to the zoning ordinance

Purpose of a Diagnostic Report

Many cities find themselves with zoning codes that are over a generation old and that do not reflect their adopted vision, nor support modern land uses and best practices. This Diagnostic Report analyzes Twinsburg’s zoning code (1989 with amendments) against the zoning-related goals of the comprehensive plan (2014 with updates in 2021) The outcomes of this analysis inform the comprehensive update of Twinsburg’s Zoning and Development Regulations.

The analysis within this Diagnostic Report is guided by three principles:

1.

Zoning should regulate only what needs to be regulated.

Zoning regulations should place limits on the use of land only when necessary to promote general welfare. Regulations that do not relate to public interests of health and safety may overstep the police power granted to governments and may not be legally defensible

2.

Zoning should respect both existing and desired development patterns.

Zoning regulations should relate to a community’s existing and desired development patterns. When regulations are out of context with existing or desired development patterns, land owners may need to apply for numerous administrative approvals and variances for typical development projects, which increase the cost of investment in a community. Furthermore, processing such administrative approvals and variances can burden government departments

3.

Zoning should implement the plan, not be a barrier to achieving the vision.

Zoning should be a tool to implement a community’s vision as expressed in its comprehensive plan. In many instances, a community invests time, funds, and energy into the development of a comprehensive plan, but zoning regulations are overlooked or revised over time in a disjointed manner. This scenario leads to outdated, inconsistent, and disorganized zoning regulations that are cumbersome, intimidating, and costly for property owners and administrators alike, impeding planning goals and economic development. A comprehensive update to the zoning ordinance that is built from the community’s comprehensive plan allows for clear, usable, defensible, and consistent regulations that operate efficiently to protect the public interests and encourage desired outcomes.

Benchmarks and Analysis

The following objectives were distilled from the zoning-related goals of the 2021 Sustainability Plan, the 2014 Comprehensive Plan specifically for its section on the City Center Redevelopment Plan, and the City Council Work Session on the comprehensive plan update

Objective A

Incentivize sustainability in land use.

This objective includes a search for the zoning code’s provisions that support or hinder elements of land use sustainability including:

• Passive energy collection systems and the placement of solar and wind capture elements

• Stormwater management.

• Protection of sensitive or critical natural areas.

• Avoiding building materials with heavy ecological footprints

• Electric charging stations.

• Multi-modal pathway creation.

Objective B

Promote adaptive reuse and rehabilitation.

This objective includes a search for provisions and standards that support or hinder adaptive reuse and rehabilitation of existing structures including:

• Reducing non-conformities.

• Supporting small businesses.

• Supporting home-based occupations.

• Providing for additions to existing structures.

• Practical use permissions for legacy buildings and challenging sites.

• Effective infill standards for passed-over vacant properties.

Objective C

Expand access to homeownership.

This objective includes a search for provisions and standards that support or hinder homeownership opportunities including:

• Regulating accessory dwelling units, cottage courts, and tiny homes (related to less material, less land, less water and energy consumption, multi-generational housing, and affordability).

• Aging in place (related to access ramps, stair lifts, and access to transit and safe walking routes).

Objective D

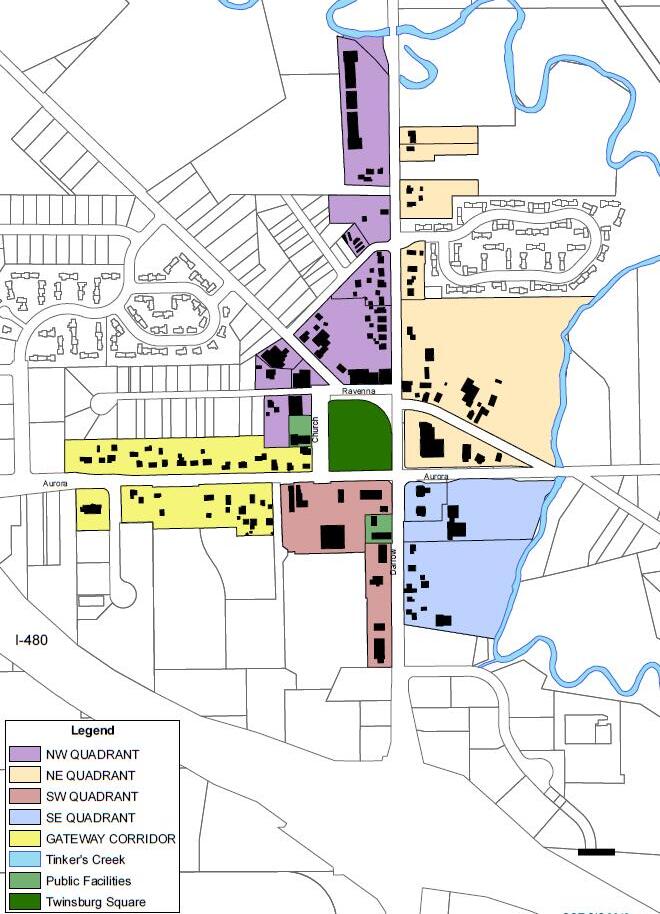

Support walkable development in targeted areas.

This objective includes a search for provisions and standards that support or hinder walkable development in targeted areas (City Center Redevelopment Plan, the Ravenna Road corridor, and the OH-82/Aurora Road corridor). Such provisions include:

• Supporting and incentivizing transportation connections and greenway connections.

• Small lot sizes for fine-grained development.

• Regulating mixed-use development.

• Supporting and incentivizing privately owned public spaces (such as parks, plazas, and artwork).

Objective E

Streamline regulatory processes.

This objective includes a search for provisions and standards that support or hinder clear, concise processes and organization of information for ease of use. Such provisions:

• Align processes with Ohio requirements.

• Remove barriers for context-sensitive investment into Twinsburg (i.e., get zoning out of the way of the built-environment investments that Twinsburg desires).

• Avoid requiring unnecessary information of applicants.

• Avoid excessive permit review procedures and timelines.

A critical analysis of Twinsburg’s zoning code based on these objectives is provided in the following pages.

Objective A: Incentivize Sustainability in Land Use

A small proportion of the 6 titles and 44 chapters in Twinsburg’s zoning ordinance directly address this objective’s elements of land use sustainability The chapters and sections highlighted below directly or indirectly address these elements and are followed by considerations to strengthen their support or lessen their hinderance of these elements.

Chapter 1105 – Definitions This chapter includes a thorough set of definitions regarding the protection of sensitive or critical natural areas. This chapter does not include definitions for passive energy collection systems, ecological footprints of building materials, electric charging stations, or multi-modal pathways. Consider introducing definitions related to these elements to allow for clear regulations. This chapter also includes definitions for design storm, detention, drainageway, and floodplain – all of which are related to stormwater management. Consider expanding these definitions to include terms such as runoff, infiltration, low impact development, and erosion control. For example, Section 1187.31 is dedicated to erosion control, but this term is not expressly defined.

Chapter 1139 – General Regulations

• Passive energy collection systems: This chapter does not specifically address or support passive energy collection systems, but in Section 1139.04, the Planning Commission is authorized to consider other uses similar to those permitted by right in any zoning district. Although it is unlikely, it is possible that solar or wind capture elements may be interpreted as similar to a permitted use, in turn potentially being approved.

• Stormwater management: Section 1139.16 requires development to maintain the integrity of drainage channels and flood plains, requiring consideration of stormwater management in the development process. This Chapter would more strongly support stormwater management by incorporating regulations for on-site stormwater retention and grey water facilities, incentives for permeable pavements, and support for native (non-mowed) plantings, among other best practices.

• Protection of sensitive or critical natural areas: This principle is not directly addressed in Chapter 1139. Consider adding clear, measurable criteria for review of zoning permits and public hearing decisions that determine the presence of sensitive areas, the effects of the proposed development on sensitive areas, and avoidance or mitigation measures from any adverse effects. Consider implementing minimum setbacks from identified sensitive areas.

• Avoiding building materials with heavy ecological footprints: This principle is not directly addressed in Chapter 1139. Consider adding regulations and incentives for recycling and reusing previously manufactured materials, deconstructing buildings that will not be used, and using locally and regionally sourced materials

• Electric charging stations: Chapter 1139 does not specifically address or support electric charging stations. Similar to the notes above on passive energy collection systems, the Planning Commission is authorized in Section 1139.04 to consider other uses similar to those permitted by right in any zoning district. It is possible that electric charging stations may be interpreted as similar to a permitted use, in turn potentially being approved.

• Multi-modal pathway creation: Chapter 1139 does not specifically address or support this principle. However, the Planning Commission may lean on its authority in Section 1139.04 to consider the inclusion of multi-modal pathways as a use similar to those permitted by right. Consider supporting, regulating, and incentivizing easements for multi-modal pathways along coordinated corridors and areas of Twinsburg.

• Additional observations: Where many of the considerations listed above focus on incentives, consider identifying a threshold of a development size where sustainable land use practices become required as a condition of approval of a permit. Such a threshold could be based on the lot area or total project site area, the presence of sensitive or critical natural areas, the gross floor area or footprint size of buildings, or the ratio of land area covered by impervious surfaces – in addition to other measures.

Chapter 1150 – Flood Damage Reduction Overlay District

. This chapter does not directly address stormwater management (or other referenced principles of sustainability in land use), but it does provide regulations on construction methods, materials, and locations as a means of reducing damage to investments in the event of flooding. Consider expanding this Chapter to include provisions for retaining stormwater on-site for properties that are not located within flood-prone areas – which will potentially reduce the amount of stormwater present in a flooding event.

Chapter 1166 – Wind Energy Turbines

. This chapter directly addresses and regulates the siting, design, operation, and similar aspects of wind energy turbines. This chapter includes minimum setback requirements from communication utilities and electrical utilities, effectively placing the most efficient siting of such turbines as secondary to other utilities. Consider requiring or allowing communication and electrical utilities to be moved to locations that are less efficient for wind energy turbines, thereby unlocking greater energy capture potential for properties in Twinsburg. This chapter does not address other referenced principles of sustainability in land use.

Chapter

1170

– Historic Preservation Regulations.

• Of the referenced principles of sustainability in land use, this chapter most directly addresses avoiding building materials with heavy ecological footprints. This language does not explicitly prohibit or encourage certain materials, but it does emphasize preserving the distinguishing qualities of historically significant features. Depending upon the interpretation, this likely encourages repairing rather than replacing historic or older materials

• This chapter does not directly address other referenced aspects of sustainability in land use, but it leaves open the possibility that the Architectural Review Board may consider as part of their review the placement of passive energy collection systems, the impact of proposed actions on the environment surrounding the historical resource, the placement of electric charging stations, and the design and integration of multi-modal pathways. Consider prioritizing passive energy collection systems and electrical charging stations by requiring their approval when they are not visible from the street; or by requiring their approval using the least-intrusive and best-camouflaged means possible when they may be visible from the street.

• Consider explicitly building into Section 1170.09 (Guidelines for Review) a reference to a review process with clear standards handled by professional staff that assesses the

effects of proposed environmental changes on stormwater management, or sensitive or critical natural areas.

Chapter 1171 – Tree and Vegetation Protection This chapter indirectly supports stormwater management principles. This chapter indirectly affects passive energy collection systems and the placement of solar and wind capture elements. This chapter directly supports the protection of sensitive or critical natural areas and the reduction of ecological footprints. To strengthen and coordinate this chapter’s support of referenced sustainability principles, consider:

• Implementing an estimated calculation on a property’s stormwater retention based on the trunk size, tree species, canopy size, and native groundcover surface areas of planted features (including that of green roofs). Include greywater retention systems in this calculation.

• Placing clear, measurable allowances for trees to be removed and replaced based on best practices (native species; tree stand groupings) to provide unobstructed solar capture for roof-mounted solar collection systems.

Chapter 1172 – Landscaping This chapter indirectly addresses certain land use sustainability principles by supporting the reduction of air and water pollution and by promoting public health and safety. Supporting the reduction of air pollution indirectly supports the use of renewable energy sources. Supporting the reduction of water pollution implies requiring effective stormwater managements practices. Although this chapter does not directly mention the protection of sensitive or critical natural areas, it does reference the intent to protect, preserve, and promote the aesthetic appeal, character, and value of the surrounding neighborhoods, which may indirectly include natural areas. Consider amending this chapter to directly support land use sustainability principles by:

• Tying this chapter more directly to Chapter 1171 – Tree Vegetation Protection (and the considerations stated within that chapter’s analysis).

• Increasing requirements that reduce heat island effects.

• Implementing critical root zone requirements that provide sufficient space for healthy trees and other plant life.

• Incentivizing no-mow native planting areas. These areas reduce the use of powered lawn care tools, typically create pollinator habitats that support healthy wildlife environments, and can be celebrated with official plaques that can fundraise for related natural area preservation efforts. These areas may also retain or filter a higher volume of stormwater than other planting areas – thereby reducing the amount of stormwater that enters public utility systems.

• Reviewing minimum landscaping requirements for parking areas to ensure alignment with the goals of breaking up large expanses of asphalt or concrete, reducing heat island effects, and providing plant life that will slow the rate of stormwater entering public utilities.

• Strengthening tree protection requirements; potentially removing the provision in Section 1172.07 (Minimum Landscape Requirements) subpart (d)(2) that removes protections for trees of 8 inches or greater in diameter that are “within the ground coverage of proposed structure or within 12 feet of the perimeter of such structures.” This may effectively remove protections for all trees where an application is submitted showing a proposed

building footprint. Consider allowing replacement of trees in limited circumstances at a rate that maintains (or swiftly replaces) the lost benefits of the trees being removed.

Chapter 1175 – Environmental Performance Standards This chapter directly addresses stormwater management Requirements for vegetated buffers, swales, watercourses, and wetlands establish or maintain critical hydrological functions that prevent erosion and sedimentation while preserving high ground-water quality. This chapter directly addresses the protection of sensitive or critical natural areas by identifying and requiring maintenance (and avoidance) of wetlands, riparian areas, water bodies, and other critical habitats. This chapter does not directly address passive energy collection systems or the ecological footprint of building materials, but the intent of this chapter indirectly supports the principles of organizing around natural resources and using environmentally friendly building materials. This chapter does not directly support nor hinder the placement of electric charging stations, but it does indirectly support the creation of multi-modal pathways through the preservation of natural areas. To strengthen the ties between this chapter and the referenced sustainability in land use principles, consider:

• Develop clear, measurable guidelines for the most productive placement and orientation of passive energy collection systems. Ensure that these guidelines are aligned with the regulations in Chapter 1171 (Tree and Vegetation Protection) and Chapter 1172 (Landscaping).

• Require and/or incentivize permeable pavement for driveways, walkways, patios, tennis courts, basketball courts, outdoor kitchens, and other hardscaped areas throughout Twinsburg.

• Incentivize the installation of rain gardens, detention basins, and other stormwater harvesting (grey water) systems.

• Expand the definition of sensitive environmental resources to cover all areas of ecological significance and develop a routine survey by a professional to maintain a map of such areas throughout Twinsburg.

Chapter 1177 – Performance Standards for Industrial Districts This chapter indirectly supports stormwater management by requiring all raw materials, finished products, and mobile equipment to be stored within an enclosed building; in turn, containing and reducing potential sources of stormwater runoff. This chapter also prohibits liquid waste from being discharged at levels that exceed other State, County, or City codes, and prohibits solid waste from being buried unless approved by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency These provisions also have a positive impact on preventing or reducing the contamination of ground water. This chapter does not directly or indirectly address the other referenced elements of sustainability in land use.

Chapter 1178 – Recreation and Open Space Land Like Chapter 1177 (Performance Standards for Industrial Districts), this chapter indirectly supports and even incentivizes stormwater management by permitting retention ponds to be counted towards minimum required park and open space area where such areas provide accessible facilities and useable open space for public enjoyment This chapter also allows the Planning Commission to require the dedication and improvement of linear parks as a condition of final plat approval. Consider tying this chapter more closely to the provisions of Chapter 1175 and consider requiring or

incentivizing (instead of solely allowing) the development of multi-modal pathways constructed of permeable pavements along or within recreation areas.

Chapter 1181 – Site Plan Review Regulations This chapter requires site plans for any development that are not exempted to show stormwater management features, a stormwater pollution protection plan, a tree and vegetation survey, a tree and vegetation protection plan, and an impact assessment. This chapter further requires the Planning Commission to evaluate the effects of constructed elements on existing natural features, encouraging their preservation. Consider closely referencing the language in Chapter 1171 (Tree and Vegetation Protection), Chapter 1172 (Landscaping), Chapter 1175 (Environmental Performance Standards), and Chapter 1178 (Recreation and Open Space Land) to coordinate these provisions so they do not duplicate or undermine one another.

The current provisions exempt one-household and two-household dwellings from meeting these requirements. Together, the R-2, R-3, and R-4 districts (which are focused on one-household dwellings) cover over 26% of the land area of Twinsburg. Consider requiring or incentivizing one-household and two-household dwellings to also meet minimum stormwater management requirements and protection of sensitive or critical natural areas.

Chapter 1187 – General Subdivision Design Criteria

. Section 1187.09 (Drainage Requirements) provides in-depth study of rainfall intensity, stormwater accumulation, and the design of in-road and off-road drainage systems – which directly impacts the management of stormwater. Likewise, Section 1187.31 (Erosion Control and Sediment Control – Storm Water Pollution Prevention Plan) requires the development of a Storm Water Pollution Prevention Plan for non-farm projects in Twinsburg. This plan must be developed in compliance with the construction standards of the Ohio Department of Transportation and the “Rainwater Land Development Manual.” Other portions of Chapter 1187 include language requiring the City Engineer to review and approve stormwater management facilities.

Consider expanding these provisions to incorporate rain gardens (and other stormwater management provisions in Chapter 1175) in medians and/or along curbs

While there isn’t language that directly addresses the creation of multi-modal pathways, there are provisions for dedication land for parks, playgrounds, open space, and other public sites, which potentially may include pathways. Consider explicitly requiring and/or incentivizing the establishment of multi-modal pathways. Consider tying the language of this chapter to the other chapters referenced above to remove duplication and remove or reduce potentially conflicting language.

Conclusion – Objective A

. In summary, Twinsburg’s zoning ordinance is largely silent on directly addressing solar energy collection systems, the ecological footprint of building materials, electric charging stations, and multi-modal pathways. Several sections directly or indirectly address stormwater management, wind capture facilities, and the protection of sensitive or critical natural areas. The considerations listed above will introduce or strengthen sustainable land use practices through requirements, incentives, or clarified references.

Objective B: Promote Adaptive Reuse and Rehabilitation

Few sections of the 6 titles and 44 chapters in Twinsburg’s zoning ordinance directly support adaptive reuse and rehabilitation; several sections establish significant hurdles. The sections highlighted below have direct effects on the zoning ordinance’s ability to support adaptive reuse and rehabilitation and are followed by considerations to strengthen their support or lessen the hurdles they create.

Changes in the R-3 and R-4 districts City staff has provided that the minimum lot width requirements in the R-3 and R-4 districts have been increased since 1965, before which many lots were platted. The standards in 1965 required a minimum lot width of 75 feet in both districts. For lots that have access to centralized water and sewer, the current ordinance requires a minimum lot width of 100 feet in the R-3 district and 90 feet in the R-4 district. This creates many lots that are legally established but nonconforming at a smaller lot width than current requirements, in turn creating unnecessary challenges for property owners in established neighborhoods who may seek to invest in their properties. Consider reducing the lot width requirement to meet the established development dimensions – legalizing previously built neighborhoods and simplifying the code for such property owners. Likewise, two-household dwellings in Twinsburg are largely zoned R-4 and are thereby legally established nonconforming uses. Consider permitting two-household dwellings in the R-4 district to support the continued investment in such properties while providing incremental opportunities for housing that can meet a wider range of needs and desires beyond one-household dwellings.

Commercial district use permissions. Use permissions for the commercial districts present a tangled web that cherry picks some uses but leaves other similar uses as prohibited (this is discussed in more depth in Objective E). The hyper specificity of permitting “Clothing, Apparel, and Variety Shop” while not permitting “Retail Sale of General Merchandise” in the C-1 district (for example) establishes an unclear set of expectations – and likely results in sending those uses to neighboring jurisdictions. Similarly, the zoning code identifies “Book Stores, Card Shops, Stationary Stores” as a unique use that is only explicitly permitted in the C-5 district. Yet, the C-2 and C-3 districts permit “Art, Photo, Stationery, Notion, Toy and Gift Sales.” Overlapping use permissions complicate what can otherwise be a clear set of expectations. Further the C-1, C-2, C-3, C-4, and C-5 districts combined cover just under 600 acres (or 5.9%) of Twinsburg’s total 10,095 acres. For these districts that are purpose built for small-, medium-, and large-scale commercial uses, and that have such relatively small opportunities for development, consider expanding use permissions and clarifying massing, parking, and signage standards to make desired development as easy and quick as possible to receive a permit.

Nonconformities Within Chapter 1157 (Nonconforming Uses), Section 1157.02 (Regulations) exempts dwellings in any business district or industrial district from being treated as a nonconforming use. This section also allows non-dwelling structures that are damaged up to 75% of their reproduction value to be rebuilt – albeit in conforming with current district regulations. Together, these provisions create critical flexibility to housing and to commercial and industrial enterprises that have existed or operated in Twinsburg prior to current zoning standards. However, this chapter lacks clarity and distinctions between nonconforming uses, nonconforming lots, and nonconforming site designs. Consider clarifying these elements and providing clear mechanisms for bringing these types of nonconformities into compliance.

Signage. In Section 1173.05 (Applicability), Twinsburg’s zoning ordinance requires all proposed signs (other than those exempted or allowed without a permit) within the city to be reviewed at a public hearing by the Architectural Review Board. Consider reserving public hearings for appeals of administrative decisions, granting exceptions to generally applicable rules, or interpreting complex situations. By introducing clear, measurable standards that can be administered by staff without a public hearing, Twinsburg’s zoning ordinance will provide a more competitive regulatory landscape while setting clearer expectations for property owners. This in turn fosters consistent outcomes and focuses the energy of volunteer appointed boards on the most impactful projects.

Parking requirements.

• Section 1174.05 (Supplementary Regulations) requires the dimensions of an individual parking stall oriented 90 degrees from the travel lane to be at least 9 feet wide and 18 feet deep (or 162 square feet per parking stall). The table in Section 1174.03 (Schedule of Parking Requirements) requires steep amounts of land in Twinsburg to be reserved for the temporary storage of vehicles in comparison to certain uses. For example:

o “Medical centers” require 7 parking stalls (1,176 sq. ft.) per 1,000 sq ft. – which is 117% – of floor area devoted to the activity or 1 per 2 members, whichever is greater.

o “Retail stores and services (20,000 sq. ft. floor area and less)” require 4 parking stalls (648 sq. ft.) per 1,000 sq. ft. – which is 65% – of floor area.

o “Sit-down restaurant/lounge” requires 18 parking stalls (2,916 sq. ft.) per 1,000 sq. ft. – which is 291% – of gross floor area or 1 per two seats, whichever is greater.

o “Mortuaries” require 1 parking stall (162 sq. ft.) per 100 sq. ft. – which is 162% –of floor area.

o It is important to note that these ratios described above do not include the land area required for driveways, travel lanes, and related vehicular maneuvering areas that are required for a functioning parking lot.

• Section 1174.11 (Landbanked Parking) provides a critical relief mechanism from the current minimum parking requirements by allowing the Planning Commission to approve spaces that are reserved on a property but left unconstructed. Consider simplifying minimum parking requirements so that they are based on the footprint of buildings (which only change through approved permits) instead of based on the number of employees during the largest shift (which can fluctuate without triggering permit reviews). Consider reducing minimum parking requirements so that they do not effectively require temporary vehicular storage to be the primary use of properties (where the square footage of the parking area is greater than the building itself). Consider maintaining standards for all parking that is voluntarily provided should a property owner desire to provide more than the minimum required parking. A simplified minimum required parking table could look like the following (accompanied by clear definitions of “customer service floor area” and “non-warehouse floor area”):

Type of Use

(Regardless of District)

Residential Uses

Commercial and Office Uses

Industrial Uses

Minimum Required Parking Spaces

1 space per unit (1)

1 space per 500 square feet of gross customer service floor area

1 space per 5,000 square feet of gross non-warehouse floor area

Mixed-Use Buildings 1 space per 600 square feet of gross floor area

Public Uses Decided per the Planning Commission

Table Notes:

(1) A unit is a residential dwelling, not the number of bedrooms within a residential dwelling.

PUD use permissions Twinsburg’s zoning code establishes the Planned Unit District (PUD) in Chapter 1161 “to promote large scale residential development in an integrated and harmonious manner … for the inclusion of varying housing types with common open space areas within a single development area.” The current use permissions exclusively allow one-family detached and attached dwellings by right, and conditionally allow the following uses:

• Adult Day Care

• Automatic Teller Machine

• Child Day Care Center

• Drive-Up Service Window

• Government Owned and/or Operated Parks, Playgrounds and Recreation

• Home Occupations

• Outdoor Dining Area

• Private Recreational Facilities

• Public Utilities, Structures, and Right-of-Way

• Religious Institution

• Telecommunication Towers

• Temporary Buildings for Construction Work

This district replaced a former district called PUD1 which permitted multi-family residential uses, single-family residential uses, and commercial uses. Some commercial and multi-family residential uses were constructed and established within the former PUD1 zone and are now made nonconforming by the newer PUD standards.

By creating nonconformities in this way (structures or uses that were legally established but are now subject to standards that they do not meet), Twinsburg’s zoning code makes such existing investments in the city more difficult to insure, obtain financing for renovations, find new tenants that keep the lights on, make sensitive investments into expansion, and even sell. Establishing nonconformities can also artificially lower the property value of such investments. This works counter to the Comprehensive Plan’s goal of promoting adaptive reuse and rehabilitation.

The presence of single-use PUDs may also indicate that existing zoning standards do not meet the community’s desires. While PUDs can provide a useful tool for accommodating unique developments, it is important to use them judiciously and in alignment with broader planning goals and policies. Consider legalizing existing investments in Twinsburg by mapping established development in zoning districts that are appropriate to the pattern of development and the existing and anticipated uses.

Business district architectural design standards. Section 1148.20 (Business District Architectural Design Standards) presents several concerns. It lacks critical specificity and objective standards, making it difficult for property owners to fully understand and comply with the requirements. This section also adds yet another public hearing on top of (or in coordination with) other hearings for commercial uses, adding excessive and unnecessary delays to the process of someone investing in the few areas of Twinsburg that are zoned commercial. The vague language and subjective criteria for architectural design standards foster inconsistent interpretations and appear difficult if not impossible to enforce equitably. The zoning ordinance must provide clear, measurable standards that can be administered by professional staff without requiring interpretation through public hearings. Consider significantly amending this section to implement clear and measurable standards so that the zoning ordinance fosters a more efficient and predictable regulatory landscape that directly supports and incentivizes Twinsburg’s desired developments.

Conclusion – Objective B. A clear set of standards (use permissions, dimensional requirements, parking standards, etc.) aligns Twinsburg’s zoning ordinance directly to the vision the city has set for itself. Removing hurdles – especially time-consuming hurdles – for proposed investments that clearly meet clearly stated standards is the most effective way to support and incentivize such development while simultaneously making Twinsburg more competitive for attracting investment For the relatively few commercial areas in the city (5.9% of the city’s total land area), having clear standards that are based on the impacts of businesses rather than specific merchandise on their shelves also provides significant flexibility for empty storefronts to be marketed for new businesses that are no more intense than currently permitted uses.

Objective C: Expand Access to Homeownership

Twinsburg’s zoning ordinance is practically silent on accessory dwelling units, cottage courts, and tiny homes These housing options can provide highly effective means of increasing property values, flexibly developing passed over land and infill sites, and supporting populations that desire to age in place. Tools like these are rooted in historic practices of residential land development, yet they were forgotten or disfavored in recent generations of zoning ordinances. The ideas below represent current best practices in providing sensitive flexibility for housing opportunities that can meet a wide range of desired living arrangements for diverse households.

Accessory dwelling units. Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) can take many forms but are, in essence, an individual dwelling unit located on the same property as a primary dwelling. An ADU can be attached to the primary dwelling as part of an addition, detached from a house in an accessory structure (including above a detached garage), located in an upper floor of a primary dwelling, or located in an accessible basement that provides proper ingress, egress, light, and air. Some cities permit only certain kinds of arrangements for ADUs, and others allow greater flexibility. Consider permitting attached ADUs by right as an accessory use to primary dwellings on lots that meet dimensional requirements.

ADUs in any form can make multi-generational households more comfortable – providing space and independence for in-laws, and easier access to childcare for parents. ADUs can bring an additional source of income that provides important flexibility (or survival) for a household’s budget. And where individual property owners may choose to construct an ADU, they also end up providing different housing options that can meet the needs of a diverse range of households. For example, a single-person household may not desire to own a house or rent an apartment, but still wish to be close to a job opportunity in Twinsburg. Renting an ADU can be mutually beneficial, especially where the owner is aging and finds that retirement and/or social security benefits are not keeping up with rising costs; or where the owner is having difficulty affording childcare.

Figure 1 - Example ADU Arrangements (illustrated by the American Planning Association).

Consider permitting accessory dwelling units for single- and two-household dwellings with limitations that the ADU must be smaller than the primary dwelling and located in a rear yard (if not incorporated within the primary dwelling). Note: allowing ADUs does not require existing

households to construct one. Increasing housing options in the zoning ordinance will not affect properties that are subject to duly adopted homeowner’s association bylaws where the bylaws restrict or prohibit such development.

Cottage courts The smallest non-apartment dwelling size permitted in Twinsburg is 1,600 square feet in the R-4 district as required by Section 1143.09 (Area, Yard, and Height Regulations). The minimum required size of one-story dwellings without a basement in the R-2 and R-3 districts are 1,800 square feet and 1,700 square feet, respectively Note: The R-8 district referenced therein is not mapped in Twinsburg. Consider reducing square footage minimum requirements which have a direct effects of pricing out potential property owners or encouraging larger, multiple-income households. Reducing square footage minimum requirements can unlock housing options cottage courts that meet a wider diversity of household needs and preferences

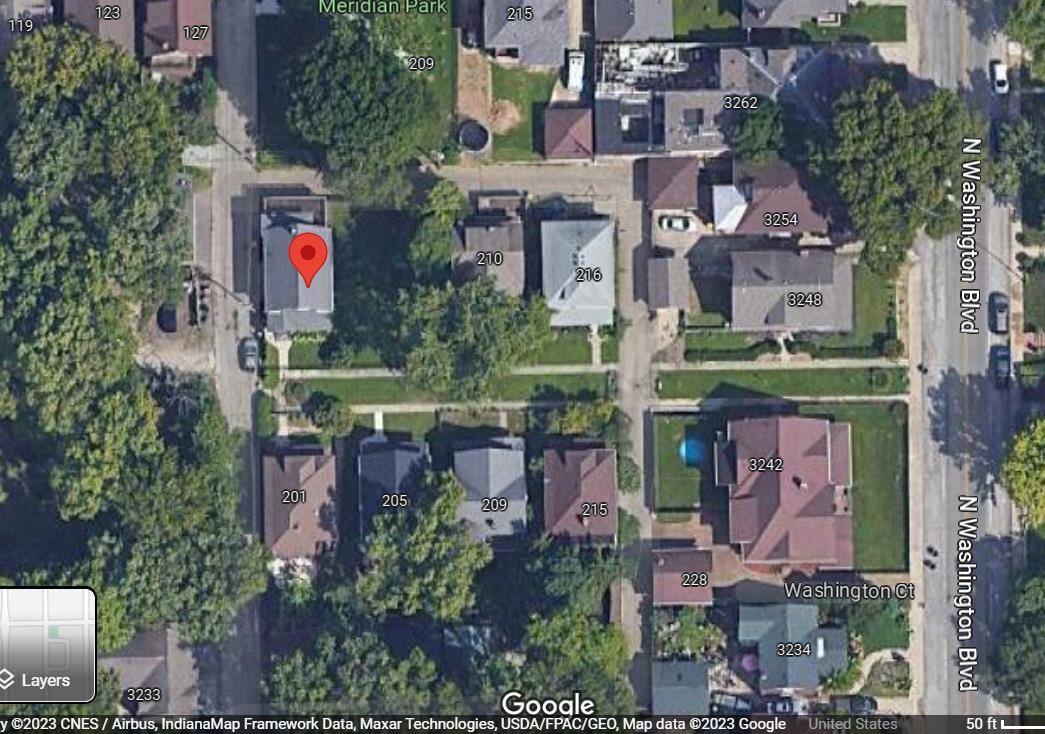

Cottage courts are typically groups of four to eight dwellings that are oriented toward a greenspace instead of a vehicular roadway. Some cities permit this arrangement on one property, while others require each dwelling to be separately platted. Dwellings in this arrangement typically require less land, allowing for varied configurations that can fit previously passed-over or challenging sites that have deep lots with limited street frontage or that have environmentally sensitive areas that need to remain undisturbed. The example below includes 202 Washington Court in Indianapolis, Indiana.

-