ZacharyElliott

ZacharyElliott

ZacharyElliott

ZacharyElliott

AbstractThisdissertationexploreshowparkusersencounterandexperiencethedesignedspacesof QueenElizabethOlympicParkinEastLondonasariverineurbanpark.Itproposesthenovel conceptualframeworkoftheriverineparknexustounpackhowriverineparksaredesignedas hybridsocio-naturesgearedtowardsdeliveringenjoyableandrestorativerecreational experiences,accommodatingnonhumaninhabitants,andprovidingfloodprotectionto surroundingareas.

BasedonmyownaffectiveimpressionsoftheOlympicPark’sspacesandvolumes,andmy understandingoftheirdesignthroughaclosereadingofdesigntexts,thisdissertationargues thatthepark,ashybridandcyborg,integratesrecreational,ecological,andhydrological approachestoriverineparkdesigntoblurtheboundariesbetweencityandpark,natureand culture,landandwater.

Tocounteranover-emphasisintheexistingacademicliteratureondesignintentionsover affective,more-than-humanencounterswithhighlydesignedspaces,theremainderofthe dissertationbuildsonsixteenconversationswithusersoftheOlympicParktoconsiderhow peopleexperienceandencountertheparkassocio-ecologicalhybrid.Itisvitaltoconsiderhow parkusersencounterandanimatethespacesandvolumesoflandscapesliketheOlympicPark becauseurbanparksaredesignedforpeople.

ThisdissertationarguesthattheOlympicParkisencounteredbyitsusersasaseriesofmorethanspacesthataredynamic,complex,andlived-inbyhumansandnonhumans.Thecomplex characterofthepark’sspacesandvolumes,asaseriesofzonesandlevelsthatrunintoand blurintoeachother,createsaseriesof‘parkswithinparks’,eachwithadifferentatmosphere andpaletteoflatentpotentialities,accommodatingdiverseexperiencesandpracticeswithinthe singularityoftheOlympicPark.Becausetheparkisahybridlandscapemeltingtheboundaries betweenhumans/nonhumans,city/nature,andpark/city,humanandnonhumanworlds collideinthepark’sspacesindelightfulways,deliveringadistinctivesensethatthereis‘more aroundyou’.

Thisdissertationdemonstratesthatthedeploymentofrecreational,ecological,andhydrological designstrategiestoriverineurbanparks,inawaythatrideswiththemessinessofcitiesas hybridandmore-than-human,isnotonlybeneficialforurbanhydrologyandecology,butcan alsocontributetoenjoyable,intriguing,andrestorativeexperiencesforhumanparkusers.

Urbanstreamsarebackinvogue.Sotooareriverineurbanparks:parksintegratingurban streamsaspartoftheirdesign(DreiseitlandGrau,2012;Prominskietal.,2017).Theseparks weavetogetherwater,city,andgreenerytomakecitiesmoreliveable,ecological,andflood resilient:buzzwordsamongbuiltenvironmentprofessionals(MostafaviandDoherty,2010; Speck,2013;Barbaux,2015;Montgomery,2015;Prominskietal.,2017;Sim,2019;Kuhlmann etal.,2021).

Butdothedesignintentionsofriverineurbanparkstranslatetoparkusers’livedexperiencesas theyencounterthesedesignedspaces?Thisquestionisunansweredbyexistingacademic literature,whichoftenplacesanemphasisontheproductionofdesignedenvironmentsrather thanonhowtheyareexperienced,engagedwith,andusedbypeopleeveryday(Degenetal., 2008;Ebbensgaard,2017).

ThisdissertationfocusesontheQueenElizabethOlympicParkinEastLondon(alsoreferredto inthisdissertationasQEOP,the‘park’,andtheOlympicPark)asacasestudyforexploring howparkusersencounterthedesignedspacesofriverineurbanparksintheireverydaylives. Openedtothepublicin2014,theQueenElizabethOlympicParkliesattheheartoftheLondon 2012LegacyMasterplan(McNevin,2014;NaishandMason,2014;Wainwright,2014).Itwas selectedasacasestudyforthisdissertationbecauseitisoneofthemostcomplete,concrete examplesofecologicalriverineurbanparkdesign,weavingtogetherhabitats,water,andthe builtenvironmentinanovel,innovative,andhighlyaestheticizedway(DyckhoffandBarrett, 2012;HopkinsandNeal,2013).

Thisdissertationaimsto“investigatehowusersoftheQueenElizabethOlympicParkencounter andexperiencethepark’sdesignedspaces”todrawoutsomeofthewaysinwhichriverine urbanparksarelivedin,perceived,andexperiencedbytheirusers.

Chapter2reviewsthecurrentliteratureoncitiesashybridsocio-naturesandintroducesthe conceptoftheriverineparknexustoconceptualisehowriverineparksareapproachedby designprofessionals.Chapter3considersthemethodsemployedinthisdissertation.Chapter4 considersthedesignintentionsbehindtheQEOPandmyaffectiveencounterswiththepark.The thematicchapters5to7thendelveintothethreeresearchquestionsoutlinedinChapter2to considerhowtheriverineparknexusisexperiencedbytheusersoftheQEOP,considering affectiveimpressions,humanandnonhumanencounters,andwateryexperiencesoftheQueen ElizabethOlympicParkinturn.Chapter8concludes.

Thisliteraturereviewstartsbyconsideringthecityasahybridspacewherethesocialand ecologicalcollideandareintimatelyentangled.Itthenzoomsintotheriverineurbanparkasa hybridsocio-ecologicalspace,proposingtheriverineparknexusasaconceptualtoolfor exploringhowriverineurbanparksaredesignedtomeetamultiplicityofhumanneeds.Finally, theproblemspacewithinwhichtherestofthedissertationissituatedissetup.

Anextensiveurbanscholarshipchallengestheideathatcitiesareanantithesistonature, buildingonarichhistoryofwritingthecityasecological(McHarg,1969;Braun,2005;Levy, 2011).Thisscholarshipencountersthecityas“bothnaturalandsocial”(Swyngedouw,1996,p. 66).Citiesaresitesofcyborg,hybridisednatures,wherethecityandthesocialareintimately entangledwithnatureandtheecological(Swyngedouw,1996;Gandy,2002).Inthisway,the cityismore-than-human,hybrid,orcyborg,becausenonhumansareconstantlymobilisedand metabolisedinitsconstantmaterial(re)production,andbecausenonhumanlifeconstantly circulatesandinhabitsurbanspaces,justashumanlifedoes(Braun,2005;Newelland Cousins,2015).

HinchliffeandWhatmore's(2006)conceptoflivingcitiesisusefulheretohelpusunpackthese ideas.Theyarguethat“citiesareinhabitedwithandagainstthegrainofexpertdesigns”by heterogenoushumanandnonhumaninhabitants(HinchliffeandWhatmore,2006,p.124). Nonhumansmorethanmerelyexistincities,as,justlikehumans,theycanshapeandare shapedbytheirurbanrelations.Becauseurbanspacesandsocio-naturesarebothinhabited andenactedbyhumansandnonhumans,citiesarejustasmuchecologicalastheyaresocial (HinchliffeandWhatmore,2006).

Urbanpracticesandexperiences“involveoren-foldpeopleandamyriadoflivingandnonlivingthings”,because,“[f]romtheroutinesofwalkingthedogorworkinganallotmentto plantingatreeorconstructingapond”,humanlivesconstantlybrushupagainstnonhuman livingandnon-livingthings(HinchliffeandWhatmore,2006,p.131).Forexample,aperson goingforawalkalongariverinaparkmightinteractorengagewith(nonhuman)street furniture,water,andbirdsastheymovethroughthespace.Thisdeepentanglementofnature withculturedemandsthatwecannotconsiderpeopleasinimicaltonatureornatureantithetical tocities,andthatweshouldrefusedivisionsbetweensociety/natureandhumans/nonhumans bytakingthemessinessoflivingtogetherandurbansocio-naturesseriously(Hinchliffeand Whatmore,2006).

Butwhatdoesencounteringthecityassocio-ecologicalhybridmeanforhowprofessionals designurbanspaces?Theconceptoflandscapeurbanismisusefulhere(Waldheim,2002, 2011;Gray,2011).Becauseanature-culturedualismnolongermakessense,landscape urbanistsarguethatweneedadynamic,adaptivelandscapearchitecturefocussinglessonthe qualitiesofspaceandmoreonthesystemsconditioningurbanform,asnature-cultureintersect, interweave,andareentangledinthecontinuous(re)productionofhybridspacesthatare necessarilyboth‘natural’and‘artificial’(SchaferandReeser,2002;Waldheim,2002;Corner, 2006).This“looser,emergenturbanism”(Corner,2006,p.23)takeslandscapeasa fundamentalbuildingblockforurbandesign,andhasinformedarangeofbuiltprojects, includingtheHighLinelinearparkinNewYorkCity(Figure4),andJamesCornerField Operations’proposalforFreshKillsonStatenIsland(Steiner,2011;Ebbensgaard,2017).Both oftheseprojectstreaturbanspaceasahybridsocio-naturebyblurringtheboundaries betweenparkprogramming,habitats/plantings,andhardsurfacecirculationsystems,andthey areprocess-based,astheypreparetheurbansurfaceasopen-endedforitsuncertain appropriationbyhumansandnonhumans(Corner,2006;Pollak,2007;Steiner,2011; Ebbensgaard,2017).

Riverineurbanparksareurbanparksincorporatingariveraspartoftheirdesign.Theyare hybridsocio-ecologicalspacesastheycombine,reconfigure,andmetabolisenonhumanand human,livingandnon-living,elementsthroughdesigntosatisfyamultiplicityofhumanneeds (Prominskietal.,2017).

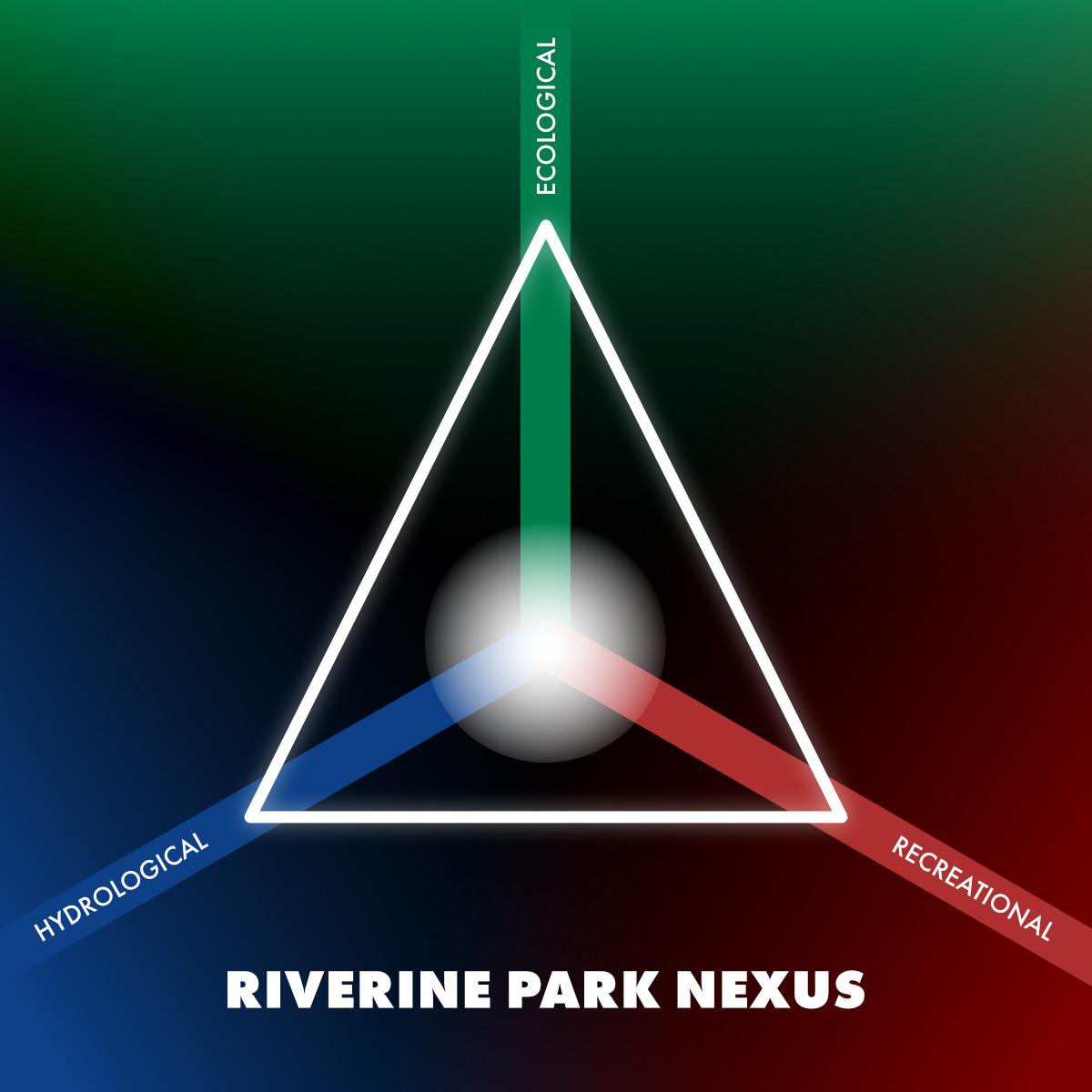

Thisdissertationintroducesthenovelconceptoftheriverineparknexus,whichdescribesthe spatiotemporallycontingentintersectionofrecreational,ecological,andhydrological approachestowardsthedesignofriverineparks(Figure5).ThisconceptbuildsonProminskiet al.’s(2017)identification,intheircomprehensivehandbookofriverplanning,ofthree approachestowardsriverspacedesign,byextendingandexplicitlyconsideringtheminthe contextofriverineurbanparks.Thethreeinterconnectedapproachestowardsriverinepark designthatcomprisethenexusaretakenasfollows:

1.recreational:riverineparksasdesignedtomaximiseenjoyableandrestorative experiencesastheyareinhabitedandusedbyhumanparkusers

2.ecological:riverineparksasdesignedtoaccommodatenonhumaninhabitantsandto maximisepleasantnonhuman-humaninteractions(‘contactwithnature’)

3.hydrological:riverineparksasfront-linedefencesagainsturbanflooding

Tounpacktheconceptoftheriverineparknexusfurther,therationaleanddesignstrategies behindeachapproachtowardsdesigningriverineurbanparkswillnowbeconsidered.

riverineparksasdesignedtomaximiseenjoyableandrestorativeexperiencesastheyare inhabitedandusedbyhumanparkusers

Aparkthatdelivershighlevelsofrecreationalvalueisoftenonethatprovidesarangeof opportunitiestorelax,socialise,andrecreatenearhomesandworkplaces(Bradleyand Millward,1986;Burgessetal.,1988).Understandinghowparksaredesignedtomeetthe needsoftheirusersisvitalbecausethedesignedspacesofurbanparksdonotjustsitthere, theycreateconditionsofpossibilityandcontextsforexperience,practice,andbeing(Harrison, 2000;Degenetal.,2008;Pallasmaa,2012).

Urbanstreamsaremorethanaconduitforwater,aquaticlife,andrivertraffic:theyformpartof thesocio-culturaltextureandcharacterofaplace(Edenetal.,2000;EverardandMoggridge, 2012;Wantzenetal.,2016).Thisiswhyriverineparksoftenintegrateriversintotheirdesign,to emphasisethe‘water-based’characterofanurbanareaandhighlightrelationshipsbetween city,aquaticlife,andwater(Manning,1997;Prominskietal.,2017).Thiscanbedoneby improvingvisualand/orphysicalaccesstourbanstreams,sothattheriverfeelspartofthe urbanlandscape.Onewayinwhichthiscanbeachievedisthroughthecreationofapath circulationnetworkthatallowsparkuserstogetdowntothewater’sedge,moveup/downthe

Recreational,ecological,and hydrologicalapproachestowards designingriverineparkscanbe consideredasinterconnected throughthelensoftheriverinepark nexusconcept

The5km-longBergesduRhône (2007)parkinLyon,France,isan openspacecreatedintheheartof thecitytomaketheRhônemore accessiblethroughgenerous provisionofstepsandpathsdown toandalongtheriver,reconnectingtheRhôneandLyon afteryearsofseparationbyabusy road(Prominskietal.,2017)

ImagebyJean-MarcBrivet,2007, CCBY-SA 3.0,WikimediaCommons, https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Berges_du_Rh%C3%B4ne.JPG)

rivervalley,andintotheriverineurbanparkfromthe surroundingcity(Manning,1997;KondolfandPinto, 2017;Prominskietal.,2017;Figure6).Design strategiesmayalsoinvolveincreasingriver turbulence,eco-morphologicalquality,andedge complexitybyvaryingbankconditions,vegetation plantings,andriverbedlevelsinordertoincrease visualinterestintheriverspace,amplifythepresence ofanurbanstreaminapark,andtomaximisethe potentialforparkusers’restorativeexperiences‘by thewater’(Manning,1997;JunkerandBuchecker, 2008;Prominskietal.,2017;Figure7).

Designersalsoworktocuratetheaffective atmospheresofriverineparks,givingthem ‘character’(Anderson,2009;Böhme,2014;Gandy, 2017).Thisisabout“creat[ing]embodiedandlived existentialmetaphorsthatconcretiseandstructure ourbeingintheworld”(Pallasmaa,2012,p.76), designingspacestoencouragecertainwaysof encountering,using,andexperiencingthem (Anderson,2009;Gandy,2017;WaittandKnobel, 2018).Strategiestoachievethiscanbeassimpleas addingfeatureslikestreetfurnitureorplay equipmenttoaspace,toencouragesittingor playing,butareoftenmoresubtle,asthesize,shape, colours,lights,sounds,andsmellsofdifferentspaces andvolumescanbemodifiedtodistinguishthemas ‘characterareas’(Anderson,2009;Waittand Knobel,2018).Suchtechniquescancreateasenseof cosinessandseclusion(asmaller,quieter,andmore enclosedspace),opennessandinspiration(anopen spacewithhighlevelsofvisibility),orofmovement alongakeycirculationroute(awidecorridorfreeof obstructionstodesignateitsuseasamain throughfare)forparkusers(Kaplanetal.,1998).So, thenatureandcontentsofurbanparks’spacesand volumescreateapaletteofopportunitiesandlatent potentialitiesfortheirrecreationaluseandencounter byparkusersalongandagainstthegrainoftheir design(Degenetal.,2008).

TheRiversWieseandBirsinSwitzerlandhavebeenrevitalised intheirBaselreachesbybreakingdowntheirrigidchannelised, trapezoidalprofileandaddingbaffleandflow-redirecting elementstostimulateamoredynamicflowandtopromotea richeraquaticecology(Prominskietal.,2017)

Top:Birs,Basel,Switzerland(RolandZumbuehl,2005, CCBY-SA4.0, WikimediaCommons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2005Birsfelden-Birs.jpg)

Bottom:RiverWiese,LangeErlenPark,Basel,Switzerland(Miraculix3,2012, CCBY-SA3.0,WikimediaCommons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Flu%C3%9F_Wiese_Eisenbahnbr%C3%BCcke_Blick_flussaufw%C3%A4rts _Lange_Erlen.jpg)

riverineparksasdesignedtoaccommodate nonhumaninhabitantsandtomaximisepleasant nonhuman-humaninteractions(‘contactwithnature’)

Riverineurbanparkscanalsomaximisewellbeing benefitsandrestorativeexperiencesbyincreasing opportunitiesfor‘contactwithnature’inthepark.This isaboutdeepeningtheentanglementof,andthe densityofinteractionsbetween,humanand nonhumanlives(Kaplanetal.,1998),andisthecore objectiveofanecologicalapproachtoriverinepark design.

Thiscanbeachievedbydesigningriverineparksto havehighlevelsofhabitatcomplexityandby weavinghabitatsand‘nature’throughoutthepark’s landscaping(Kaplanetal.,1998;Malleretal.,2006; Fulleretal.,2007;Figure8).Thisisanapproach called‘ecologicallandscapedesign’,whichisall abouttheintentionalproductionofhybridsocionaturesthatenrolnonhumansinthedeliveryofsocioculturallydesirableecosystemservices(Danieletal., 2012;Ernstson,2013;Gómez-BaggethunandBarton, 2013;Ernwein,2021).Thesecaninclude opportunitiesfor‘contactwithnature’,tohave relaxingexperiences,andforhumanparkusersto improvetheirmentalandphysicalwellbeing(Kaplan etal.,1998;Malleretal.,2006;Fulleretal.,2007).

ThefloodwallsandriverbanksoftheRiverRegenhavebeen renovatedatRegensburg,Germany,byplacingbouldersandwood elements(asurbanfurnitureandcurrent-deflectors),planting riverbankswithriparianvegetationandreedbeds,anderectinga floodwallwithdetachableelements(sosightlinestotheriverarenot permanentlyobstructed)tomaximiseaesthetic,ecological, recreational,andfloodprotectionbenefits(Prominskietal.,2017)

Left:DerRegeninRegensburgbyHighContrast,2009, CCBY3.0DE,Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Regen_in_Regensburg.jpg

Above:Mboesch,2015, CCBY-SA4.0,WikimediaCommons https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Regen-uferpromenade-reinhausen.JPG

riverineparksasfront-linedefencesagainsturbanflooding

Riverineparkspacesarealsodesignedashydrological,asfloodprotectionforthereachofthe urbanstreamflowingthroughtheparkhastobeembeddedwithinthepark’sdesigntoprotect buildingsandinfrastructureinandaroundtheparkfromflooding(Prominskietal.,2017).

Traditionalrivermanagementapproachesaredesignedtoroutestormwateroverimpervious surfacesintoconcrete-linedurbanstreams,eliminatinghydrological,geomorphological,and ecologicaldynamicstoevacuatewateroutofthecityasfastaspossible(Penning-Rowselland Burgess,1997;Chocatetal.,2001;PaulandMeyer,2001;Burnsetal.,2012).Theresultisthe geomorphologicalandecologicalsimplificationofurbanstreams(Allanetal.,1997;Pauland Meyer,2001;Elosegietal.,2010).Butthisalsoyieldsanaestheticsimplification,asthe suppressionofurbanstreamdynamicsreducesthevisualandrecreationalinterestofurban streamsfortheirusers(Clarkeetal.,2003;vanStokkometal.,2005;Prominskietal.,2017).

Alternativerivermanagementanddesignstrategieshaveemergedinthepasttwodecades (Prominskietal.,2017).Thesestrategiesaimtoincreaseresilienceagainstfloodingevents (Burnsetal.,2012),whilealsomanagingfloodwaterandriversinamorepeople-and ecologically-mindfulwaytomaximisetherecreationalvalue(Manning,1997;vanStokkomet al.,2005)andecologicalservices(LiandEddleman,2002;Clarkeetal.,2003;Elosegietal., 2010)thaturbanstreamsdelivertocities.

Rivermanagementstrategiestacklingtheseobjectivesinthecontextofriverineparkdesign includeWaterSensitiveUrbanDesign(WSUD)/SustainableUrbanDrainageSystem(SUDS) approachesandriverrehabilitation.WSUDandSUDSapproachesareaboutthe'at-source' managementofstormwater,designingurbancatchmentstorespondtorainfallinawaythat mimicsnonurbanconditions(Walshetal.,2005;Royetal.,2008;WongandBrown,2009). Thisallowsmorecomplexaquaticandriparianecosystemstodevelop,astheyaredisturbed lessfrequently(Walshetal.,2005;Burnsetal.,2012).

Riverrehabilitation,ontheotherhand,isapartialstructuralandfunctionalreturntoariver’s pre-disturbance(i.e.pre-urbanisation)conditions,wheredesirableriverfeaturesareselectively restored,regardlessofwhethertheywerepresentbeforedisturbancetookplace(Tapsell,1995, p.98).Thisisamoreproductiveapproachthanfullriverrestorationasacompletestructural andfunctionalreturntopre-disturbanceconditionsrarelyoccursandislikelyimpractical (Cairns,1988,1989;Tapsell,1995;BoothandJackson,1997;DufourandPiégay,2009).This deliversamoreaesthetically,hydrologically,andecologicallycomplexlandscapethatprovides moreopportunitiesforhumanparkuserstoencounterthenonhumaninhabitantsofaquatic/ riparianecosystemsandtheever-changingwatersrunningthroughthepark(Williamsand Cary,2002;JunkerandBuchecker,2008;Prominskietal.,2017;Figure7).Riverrehabilitation, then,isanapproachcentredonusingdesignasatooltoreconfigureriversandriparian environmentsinawaythatmeetsourcurrentsocioculturalneedsratherthantodogmatically recreateacertainidealisedpaststateorcondition(Adams,1996;WoolleyandMcCginnis, 2000;Kareivaetal.,2007;DufourandPiégay,2009).

Thislastpointiscrucial.RiverrehabilitationandWSUD/SUDSapproachesareappliedto riverineparksbecausetheirapplicationwouldprovidesocio-culturally-determinedbenefitsto parkusers,whetherthatbethroughincreasedfloodprotection,aquaticandriverinehabitat complexity,oraestheticappeal(Niemczynowicz,1999;vanStokkometal.,2005;Dufourand Piégay,2009;Prominskietal.,2017).

Riverineurbanparksare,then,designedtoincreaserecreationalvalue,maximiseopportunities forhumanstoencounternonhumans,anddeliverfloodprotectiontothesurroundingarea.The literaturecitedthusfarisgenerallyclearonhowcertainaffects(e.g.asenseofrelaxation)can beachievedthroughthedesignstrategiesofrecreational,ecological,andhydrological approachestoparkdesign.Yet,perhaps“toomuchhasbeenassumedabouthowthepeople whoinhabitandusethosedesignedspacesreacttothem”(Degenetal.,2008,p.1917).To counterthis,therehasbeenresearchinterrogatinghowhighlydesignedenvironmentsarelived in,especiallyinthecontextofshoppingmalls(Degenetal.,2008;Miller,2014a,2014b)and waterfrontregenerationprojects(SandercockandDovey,2002).

Itisimportanttoexplicitlyconsiderhowtheriverineparknexus,asacombinationof recreational,ecological,andhydrologicalapproachestoparkdesign,islivedin,experienced, andencounteredbythepeoplethatuseriverineparkspaceseveryday.Thisisbecause understandinghowpeopleencounterriverineparksallowsustodesignthemtobettermeet parkusers’needsandinterests.

Asasteptowardstakingseriouslythisquestionofhowtheriverineparknexusisencountered, theremainderofthisdissertationwillconsidertheQueenElizabethOlympicPark(QEOP)asa builtexpressionofthenexus.Chapter4unpackstherecreational/ecological/hydrological strategiesthatinformtheQEOP’sdesign,whilethreeinterconnectedresearchquestionsare addressedinChapters5-7,to“investigatehowusersoftheQueenElizabethOlympicPark encounterandexperiencethepark’sdesignedspaces”asbuiltexpressionsoftheriverinepark nexus:

1.AffectiveImpressions: Howdoparkusersencounterthedesignedspacesandthe volumescreatedbythelandscapingoftheOlympicPark?

2.PlantingsandHabitats:Howdoparkusersencountertheplantingsandconstructed habitatsoftheOlympicPark?

3.BytheWater:HowdoparkusersencounterwaterintheOlympicPark?

Thisdissertationemployssemi-structuredinterviewsandmyownaffectiveencounterswiththe QEOPtoexploretheconceptoftheriverineparknexusinthecontextoftheOlympicPark.

IspenttendaysintheQueenElizabethOlympicParkthroughoutApril,July,August,and November2021,encounteringdifferentweatherconditions,seasons,atmospheres,timesof day,anddaysoftheweekinthepark.Todevelopanaffectiveimpressionoftheparkandits volumes,Imovedthrough,around,andbeyondtheparkbyfootandbicycle,both systematicallyandserendipitously,takingpausetostop,observe,reflect,makenotes,andtake photographsofdesigndetailsthroughout(DeCerteau,1984;Jacks,2004,2007;Schultz, 2014;Ebbensgaard,2017).

Designbookswrittenabouttheparkwerereadbetweenvisitstotheparktodevelopan understandingofthedesignintentionsbehindthespacesandvolumesoftheQEOP,including TheMakingoftheQueenElizabethOlympicPark(2013),adesigntextwrittenbyJohnHopkins andPeterNeal,landscapearchitectsinvolvedwiththedeliveryofthepark,andThe ArchitectureofLondon2012(2012),writtenbyTomDyckhoffandClaireBarrett.Ialsowenton acycletourofthepark,ledbya‘ParkChampion’volunteer,togetasenseofhowtheparkis presentedtothepublic.Theaimofallofthesepracticeswastounderstandanddevelopa personalaffectiveimpressionofthelandscapes,layout,spaces,volumes,andatmospheresof theparktoinforminterviewdiscussions,interviewanalysis,andmyresearchquestions(Solnit, 2001;Jacks,2004,2007;Wylie,2005;Schultz,2014;Macpherson,2016).

PriortovisitingtheQEOP,IreadProminskietal.’s(2017)handbookonriverplanningbestpractices.Thethreestrandsofriverspacedesignthattheyidentified(ecology,floodprotection, andamenity)were,then,verymuchinmindasIvisited,movedthrough,andencounteredthe QEOP(Solnit,2001).InmyencounterswiththeQEOP,eachstrandofurbanstreamdesign identifiedbyProminskietal.(2017)wasencounteredasthoroughlyentangledwitheachofthe otherstrands.Thismotivatedthedevelopmentoftheriverineparknexusconceptasanexplicit toolforunpickingandinterrogatingboththedesignintentionsbehindandpeople’sencounters withriverineparks,liketheQEOP,thatmeldtogethercity,water,and‘nature’intoahybridised seriesofvolumes.

Participantswereinvitedtotakepartintheresearchprojectthroughaseriesofposterslocated atkeynodesaroundtheQEOPthrougharrangementwiththeLondonLegacyDevelopment Corporation(LLDC)andlocalbusinesses(Figure9).Theseincludedthetemporarypark informationcentreonStratfordWalk,theViewTubeontheGreenway,DohinHackneyWick, TheHallinEastVillage,andintheQEOP’svenues:theLondonAquaticsCentre,theCopper Boxarena,theLeeValleyHockeyandTennisCentre,andtheLeeValleyVeloPark.Participants werealsoinvitedbymakingpostsinlocalFacebookgroupsandemailinglocalbusinesses. SixteenconversationswithparkuserswereheldoverMicrosoftTeams.Toprotectparticipants’ identities,numbers(e.g.P4)areusedinplaceofnamestorefertoparticipantsthroughoutthe analysischapters.

Thesesemi-structuredinterviewssetouttounderstandhowparticipantsencounteredthespaces, volumes,atmospheres,nonhumanlives,andwatersoftheQEOP.Gentlymovingthroughthree themes–recreational,ecological,andhydrological–intervieweeswereaskedopen-ended questionstoencouragethesharingofrichaccountsoftheemotions,thoughts,andexperiences thatcametotheirmindwhenthinkingabouttheQEOP’sspaces,volumes,andnonhuman inhabitants.TheaccountsparticipantsgaveoftheirexperiencesintheQEOPmeandered throughthekeythemesthatIsoughttoexplore.Thesethemesdissolvedandmeltedintoeach otherintheinterviewdiscussions,justasthespaces,volumes,andaspectsoftheQEOPare

designedtoflowintoeachotherasasocio-ecologicalhybridspaceblurringtheboundaries betweencity,water,andnonhumanlifeworlds.Interviewtranscriptswerecodedline-by-line, andtheanalyticalpointsderivedfromthisprocesssynthesisedtoanswerthisdissertation’sthree researchquestionsinchapters5-7.

Geographicalknowledgeisinherentlypartialandincomplete,andtheconclusionsofthis dissertationareverymuchdependentonwhosawtherecruitmentmaterialsandwas (un)willingtotakepartintheresearchproject(Haraway,1988).Forexample,people enthusiasticaboutthepark’sdesignmayhavebeenmoreinterestedintakingpartinthestudy thanthoseindifferentaboutthedesign.So,althoughIvalueandappreciatetheknowledges andviewsoftheparticipantswhoItalkedto,thesecannotbetakentofullyrepresentorportray theviewsofallparkusers.

IencounteredtheOlympicParkbeforeinterviewingparkusers,sointerviewees’responsesand experiencesareinescapablyandunavoidablyfilteredthroughmyown,broadlypositive, encounterswiththespacesoftheQEOPasanoutsider,asthesemoderatedtheshapeofthe interviewquestionsIaskedandhowIinterpretedparticipants’responses(Haraway,1988).This iswhyIconsidertheconclusionsofthisdissertationasstartingpointsforexploringlived experiencesofdesignedspacesintheQEOPandriverineparksmoregenerally.

Figure9

Examplesofresearchrecruitmentpostersbeing hostedattheParkInformationPoint(left;locatedon StratfordWalkduringthestudy,andnowlocatedin thePavilion,partofInternationalQuarterLondon) andtheViewTube(right;locatedontheGreenway)

ThelandscapeoftheLowerLeaValleyhasbeenirrevocablychangedona scaleunseensincethelasticeage(DyckhoffandBarrett,2012,p.256)

ThissectionconsidershowtheQueenElizabethOlympicParkhasbeendesignedasa“new benchmarkforthedesignofurbanlandscapes”(HarlandandMattinson,quotedinHopkins andNeal,2013,p.142),weavingtogetherrecreational,ecological,andhydrologicalconcerns innovel,fluid,andstrikingconfigurations(HopkinsandNeal,2013).Thediscussionstartsby takinginthecontextforandrationalebehindtheQEOP’sdesign.Itthenexploreshowthe park’sspacesandvolumesareconfiguredashybrid,usingthelensoftheriverineparknexus andbuildingonmyownimpressionsoftheQEOP’slandscapingandtheliteraturewrittenabout thepark,e.g.HopkinsandNeal(2013).

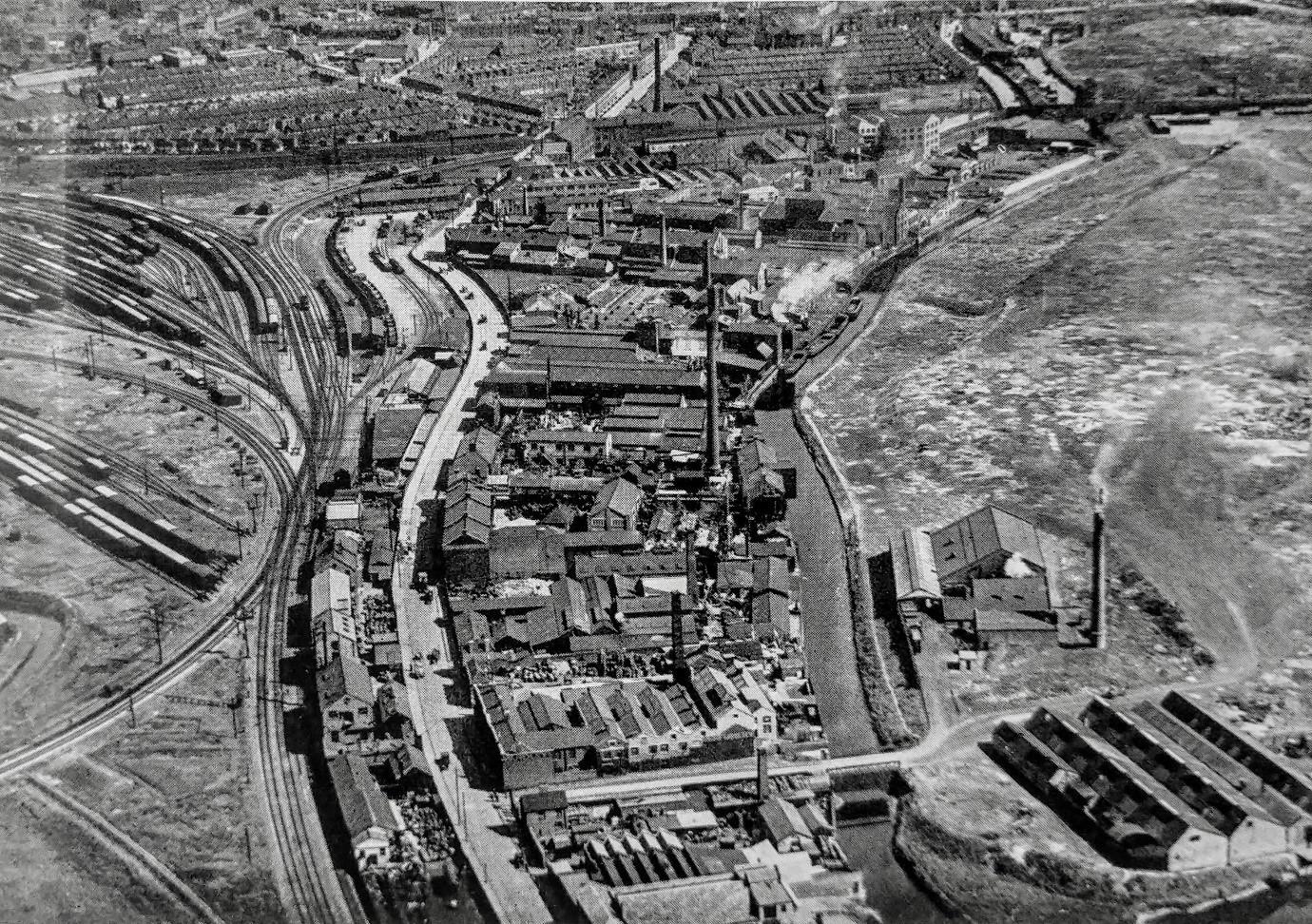

TheLowerLeaValley,thesiteselectedfortheLondon2012OlympicGamesandhomeofthe QueenElizabethOlympicParktoday,hasarichindustrialheritage(Figure10).However,longtermindustrialuseinthearearesultedinaconditionof‘post-industrialdereliction’wherethe RiverLeaandconnectedwaterwayshadlowfloodwaterstoragecapacity,werepolluted, chokedbysilt,overgrown,andinaccessibletothepublic(Nicholls,2014).Thegroundwasalso contaminated,manybuildingswereabandoned,andtransportinfrastructurewaspoor,somuch sothattheareawasdescribedas“atearinthefabricofEastLondon”(HopkinsandNeal, 2013,p.38).ThiscontextiswhytheLondon2012OlympicGameswasseenbymanytobe‘a once-in-a-generationopportunity’tomobiliselarge-scale,rapid,andintensivegovernment spendingtobringEastLondon‘up-to-par’withtherestofthecity(Nimmo,Frost,etal.,2011; GibbonsandWolff,2012b;HopkinsandNeal,2013).

Thisisnottosay,however,thattheLondon2012sitewasaderelict‘wasteland’withno socioculturalvaluebeforeitsredevelopment(Davis,2014;Harris,2015).Infact,itwasanything buta‘wasteland’(RacoandTunney,2010;Marrero-Guillamón,2012,2014;GoldandGold, 2019),as“itteemedwithadhocurbanopportunitiesforgardening,footballorjustwalking; opportunitiesforstumblingonrelicsofindustrialtimes,ortimeswhenthisareaservicedthe voyagesconnectingdistantplacestotheheartofanowdefunctempire;opportunitiesthatnow liebeneathfreshlylaidconcrete"(Colesetal.,2012,p.117).Theerasureofthepre-Olympics socioculturaltextureoftheLowerLeaValleyfromthepopularimagination,byrenderingitasa ‘wastelandripefordevelopment’,isoneofthemaincritiquesoftheLondon2012Games(Gold andGold,2008;HayesandHorne,2011;Watt,2013):thedeliveryofLondon2012asthe “cleanupofeverything”thatwastherebefore(GibbonsandWolff,2012a,p.469).Butwhat aboutwhatwasdevelopedintheplaceofwhatwastherebefore?Thisisthefocusofthis dissertation:unpickingandexploringthedesignoftheQEOPtoexplorehowtheLowerLea Valleyisencounteredbyitsuserstoday.

TheQEOPisanewkindofurbanparkdesignedforthe21stcentury(HopkinsandNeal,2013; Figures11and12).PrinciplesofsustainabilityanddeliveringanOlympiclegacyrunthroughits designrationale:creatingafuture-proofedandexcitinglandscapeweavingtogethervolumetric andspectacularspaces,water,andhabitats;deliveringanaffectiveatmosphereofmuscularity, energy,andrelaxation;andtemporarilyaccommodatingaquarterofamillionvisitorseach dayduringtheLondon2012Gameswhilemeetingtheneedsofitsusersfordecadestocome (HopkinsandNeal,2013).

Figure12

AerialImageoftheQEOPlookingfromthe SouthoftheParktowardstheNorth (photographcourtesyoftheLLDC)

Twopark‘modes’wereconceivedtodeliverthislegacy-orienteddesignvision:gamesmode andlegacymode.ThegamesmodeoftheLondon2012OlympicsandParalympicsadaptsthe visionforthelegacylandscapethroughtemporary(andreusable)structurestoaccommodate Olympiccrowds(Nimmo,Frost,etal.,2011;Nimmo,Wright,etal.,2011;HopkinsandNeal, 2013;NaishandMason,2014).Creatingdistinctpark‘modes’ensuresthatthepark,inlegacy mode,isnotoutsizedandfullofunusedvenues(‘whiteelephants’)withsuperfluouscapacity,in anattempttoavoidthedereliction-riddenlegaciesofpastOlympicGameslikeAthens2004 (HopkinsandNeal,2013;Bloor,2014).Thesetwopark‘modes’wereconnectedbya transformationoftheparkfollowingtheLondon2012ParalympicGamestoensureitwasready forafullre-openingtothepublicinApril2014(NaishandMason,2014).

ThedesignoftheQEOPrepresentsadistinctive,fresh,andforward-thinkingtakeonlandscape architecture.TheQEOP’sdesignisanexampleoftheriverineparknexusin-action,asthepark wasdesignedbyaninterdisciplinaryteam–includinglandscapearchitects,ecologists,and hydrologists–withawide-rangingsuiteofrecreational,ecological,andhydrologicalconcerns andstrategiesinmind(HopkinsandNeal,2013).

GeorgeHargreave’sdesignfortheparkwasaboutre-assertingthegeographyoftheriver, embracingtheRiverLea,andrecoveringthebeautyofitsnaturalfloodplain,whichhadbeen longobscuredbyindustry,privatisation,andpollution(DyckhoffandBarrett,2012;Hopkins andNeal,2013).Hargreave’sdesignachievesthisbydramatizingtheparkinthevertical dimensionandby“peel[ing]back”thelandformoftheparktofacilitatevisualandphysical accesstothewater’sedge(Hargreaves,quotedinHopkinsandNeal,2013,p.116).The WetlandBowlintheNorthoftheParkepitomisesthisaspectofHargreave’sdesign(Figure13), asmuscularlandformsscoopdownandprovidevisualaccesstowardstheriver’sedgeinthe NorthPark,respondingtothecurvesoftheVelodrome(DyckhoffandBarrett,2012).Waterin theQEOP,then,isdesignedtobe“somethingtoshoutabout”andcelebrate,ratherthantohide orfightagainst(DyckhoffandBarrett,2012,p.178).

Figure13

Pathswindingbetweentherollinglandforms ofthemoreecologicalNorthPark

Theresultisalandscapethatweavestogetherwater,plantings,spectaculararchitecture,and innovativedesignfeaturestoproduceanexperienceofariverine“landscapewithout boundaries”(HopkinsandNeal,2013,p.252).Thisisalandscapeintendedtostitchtogether theLowerLeaValley,blurthedistinctionbetweennatureandculture,parkandcity,andcreate everydayopportunitiesfor‘delight’,refreshment,andinspirationforthosethatuseit (Hargreavesetal.,2009;DyckhoffandBarrett,2012;HopkinsandNeal,2013).

FrommyownexperiencesvisitingtheQEOP,this‘peelingback’ofthelandscapetoexposethe RiverLeamakestheOlympicParkfeeldistinctivelyriverine.Butitalsomakestheparkfeel verticallycomplex,consistingofasuiteofinterweavingvolumesthatflowintoeachother.Atthe topofthelandscapeareopenpromenade-likeconcoursesurfacesthatinvitestrolling,running, andcycling,whilepathssweepdowntowardsthewater’sedgebetweengentlygraded wildflowermeadowsandplantings.Ifoundthisnestlingofpathsamidstrolling,muscular landformstobemore-than-functionalanddeeplyaffective,invitingmetopausein wonderment,becurious,andfollowthepathdownintoatranquilriverineworld ofriparianplantsandsoothingwaters.

Hargreave’svisionfortheparkalsosplit theOlympicParkintotwohalves,North andSouth,eachwiththeirowndistinct character,thatfeelalmostlikeparks withinapark(DyckhoffandBarrett, 2012).TheNorthParkisdesignedto feelmoreopen,ecological,pastoral, quiet,andrelaxing,withwildflower meadowplantingsthroughout(Figures 13,15and16),whiletheSouthParkis muchmoreurban(Figure14),withan atmospherefullofactivityandenergy, as“thecommonlivingroomforthe area”(Hargreaves,quotedinDyckhoff andBarrett,2012,p.129).Thisidea literallyplaysoutinthe‘rooms’created intheSouthParkconcourse,designed byJamesCornerFieldOperationstobe secludedspacesset-backfromthe park’smainthroughfares(London LegacyDevelopmentCorporation, 2018,nd).

Figure15

Abridgeandviewacrossthe moreecologicalNorthPark

ThecontrastingdesignintentionsbehindtheNorthandSouthPark manifestintheirequallycontrastinglandscaping.TheSouthPark hasamuchharder,sharper,concrete-heavyappearanceand atmosphere,reflectingitsindustrialheritage,tohandlefestivals andlargeeventsinlegacymode(Figure14).Itisalsohometo Hargreave’s2012Gardens,whichcelebratetheBritishhorticulture traditioninanoverhalfmilelongriversidedisplayofplantsfrom aroundtheworld(HopkinsandNeal,2013).TheNorthPark (Figure15),ontheotherhand,hasasofter,greener,andmore naturalisticlandscape(DyckhoffandBarrett,2012;Hopkinsand Neal,2013).“Itre-establishesariverinelandscapeandarich matrixofwetlandhabitatssetwithinasophisticatedandhighly structuredlandform”(HopkinsandNeal,2013,p.242).

BythewaterintheNorthPark,reedbedshavebeencreatedtoprovidehabitatsandtooffer somefloodprotectionvalueaspartofawiderrehabilitationoftheLowerRiverLea(Dyckhoff andBarrett,2012;HopkinsandNeal,2013).Forexample,thewetlandbowlintheNorthofthe Park,comprisedofthesereedbeds,isdesignedtoturnintoawaterlandscapeintimesofflood (Figure16).Thisisanapproachthatcreates“roomfortheriver”(vanStokkometal.,2005,p. 79),embracingandcelebratingthedynamicsoftheRiverLeawhilealsoprovidingfloodwater storagetoreducetheriskoffloodingdownstream(HopkinsandNeal,2013;Palmeretal., 2014).

Theotherwaterwaysintheparkwerealsorehabilitatedas“thelargestregenerationand restorationprogrammeeverundertakenonBritain’sinlandwaterwaynetwork”(Nicholls,2014, p.40).Channelswerecleaned-uptoremovepollution,newlocksputinplacetomakethe waterwayspubliclynavigable,historicriverwallsrestoredandrefurbished,bridgesconstructed toimproveconnectivitybetweenbanks,andnewriversidehabitatscreated,inanapproach blendingtogetherrecreational,ecological,andhydrologicalapproachestoriverinepark design(HopkinsandNeal,2013;Nicholls,2014).Therewasalsoabroaderapplicationof SUDSdesigntoolsthroughouttheQEOP’slandscape,astechniqueslikevegetatedbioswales andpermeablesurfacesweredeployedtocreateacatchmentconducivetohighlevelsof aquaticandriparianecosystemhealth(Walshetal.,2005;HopkinsandNeal,2013).

Itisclear,then,thattheQEOPintegratestherecreational,ecological,andhydrological approachesoftheriverineparknexusintotheveryfoundationsofitsdesign.Thedesignersof theparkintendedtoblurthedistinctionsbetweencityandpark,natureandculture,landand waterthroughlandscapedesign,butdothesedesignintentionstranslateintothelived experienceofthepeoplewhousetheparkonadailybasis?

Figure16

TheNorthPark'sWetlandBowl

StudiesontheQEOPhavenotyettakenthisquestionseriously.Thesestudieshaveprimarily focussedonthedesignintentionsbehindtheQEOP(Hartman,2012;GoldbyandHeward, 2013;FirthandPatel,2014;BrownandBrown,2018;OudesandStremke,2020)ortreatthe QEOPasanexpressionoftheLondon2012gamesasspectacularneoliberalmega-event (Smith,2014;Waters,2015;Dawson,2017;Cotton,2018;DawsonandJöns,2018).An exceptionisFerreri&Trogal’s(2018)paper,whichconsideredthedesignoftheSouthParkasa ‘totallydesignedenvironment’.Ferreri&Trogal(2018)interviewedlocalresidentsshortlyafter thefullopeningoftheparkin2014,andfoundthattheyheldverynegativeopinionsaboutthe parkspace,assterileanduninspiring(FerreriandTrogal,2018),atoneechoedinmedia coverageoftheparkatthetime(Moore,2014;Wainwright,2014).

Thisdissertationexpandsthesedebatesbyre-centringtheimportanceofhowpeopleencounter thelandscapeoftheQEOPassocio-ecologicalhybrid.Itisvitaltoconsiderhowparkusers encounterandanimatethespacesandvolumesoflandscapesliketheQEOPbecauseparks are,aboveall,designedforpeople(Kaplanetal.,1998),tomeetarangeofsociocultural needs(Julier,2005;Ernstson,2013;ErnstsonandSörlin,2013;ErixonAaltoandErnstson, 2017).

Howdoparkusersencounterthedesignedspacesandthe volumescreatedbythelandscapingoftheOlympicPark?

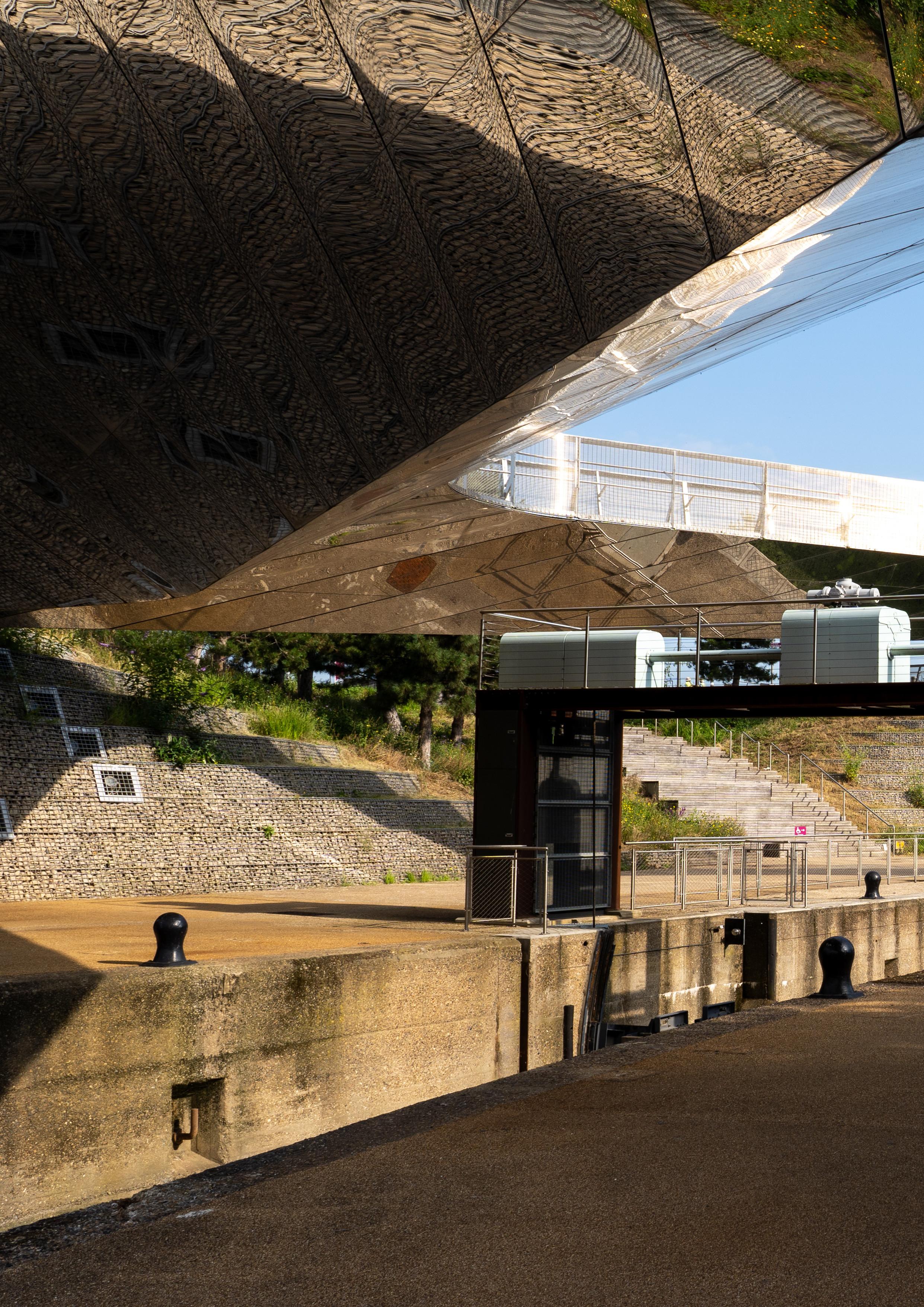

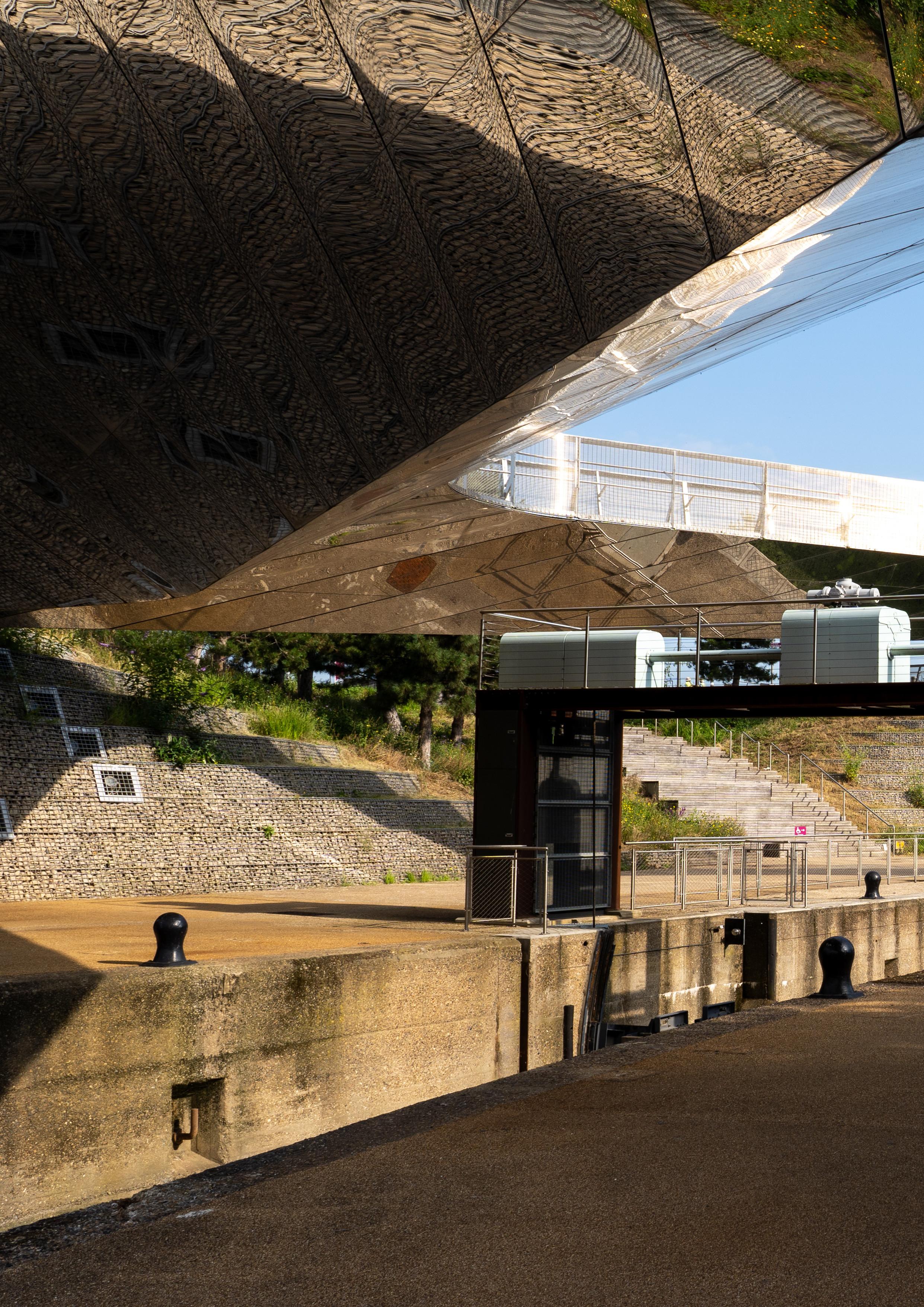

Anoverridingsenseofinspiration,intrigue,andenergyranthrough parkusers’accountsofhowtheyencounteredtheQEOP:asensethat “alotgoeson[inthepark]andyoudon'treallyhavetogofartohave alotoffun”(P9).ParticulardesignelementsoftheQEOPwere identifiedbyparticipantsareespeciallygenerativeoftheseaffectsof inspirationandawe,suchasthemirroredDiamondBridgetowardsthe NorthendoftheSouthPark,whicharchesovertherestoredradial gatesofCarpenter’sLock(Figure17).P4describestheiraffective encounterwiththisdesignelementvividly:

Andthat's[Carpenter’sLock]coveredbythisbridge, whichhasgotthissortofstainless-steelmirrored surface,soyougetthiswonderfulviewasyoulook upandwalkunderit,butalsointhesunlight,it reflectson,youknow,onthepath,whichI'dliketo thinkwaspartofthedesign,buteverythingiseye candy.It'sjusteverything,youknow.Likeabridge, yes,there'sloadsofpossibilitiestodesignabridge, butthisbridgeisjustbeautiful!(P4)

ParticipantsfoundthattheOlympicParkconstantlyyieldedthesekinds ofopportunitiestobeinspired,energised,andintriguedbecauseitis alwayschanging,hassuchanunusualdesign,andinvolvesaspatially complexlandscape.Firstly,thedesignoftheQEOPisconstantly unfolding,as“there'snewstuffgoingonallthetime”inthepark(P1), especiallyinthecontextoftheongoingdeliveryoftheEastBank project(P3,P4).

Secondly,theQEOPisdesignedunlikeanyotherparkbecause Hargreave’sdesignissobold,muscular,anddistinctive.This contributestoparticipants’encountersoftheparkas‘weird’and ‘unusual’,withrelatedaffectiveimpressionsofintrigueandcuriosity,as P11explains:

Ithinkit'sabitofaweirdplace,it'sareallyweird Park,soquitealotofthetimeI'mjustverycurious. I'llwalkaroundthinkingwhydidtheydothat?Why didtheydothis?Whyisn'ttheremoregreen?Likeall thiskindofstuff.So,there'smaybeaperplexedfeeling.(P11)

AndgiventheattentionputintothedesignoftheQEOP’slandscape,it isperhapsunsurprisingthatusersoftheQEOPfindthewayithasbeen zonedintoaseriesof‘characterareas’,withdifferentatmospheres,so interesting:

Ithinkthewaytheparkhasbeensortofzonedina way,um,isfascinating.Thewaytheretendstobethe kindofcelebratoryelementtoitinthesouthernpart, andthemorenatural,invertedcommas,althoughI knowitisn't,inthenorth.Um,Ithinkthat'sgreat,and ithasadifferentkindof atmosphere,thenorthern partofthepark,andespeciallynowthatthey’veput theBlossomGardenin,becausethat'scontemplative.(P1)

ThedesignoftheQEOPisspatiallycomplexinthisway,whichallowslong-termparkusers, whohavebeenusingtheparksinceitopenedin2014,tocontinuetobedelightedbyits designedspaces:findingnewplacesthatare“justhiddenaway”(P5),likeanoutdoorcinema (P4)andtheGreatBritishGarden(P5),andnoticingnewdesigndetailseverytimetheygo (P15,Figures18-20).Thischaracteristicofnoveltyandperpetualintrigueisbakedintothe designedspacesofthepark,astheintricatepathnetworkoftheparkallowsparkuserstotake “adifferentrouteeverytime,andthenyouseesomethingdifferentthatyou'venotseenbefore” (quotefromP11;P3,P4,P5).Itisthissensethat“there'salwayssomethingnew”tosee(P4)that hashelpedsomeparticipantstostay“saneduringthepandemic”(P5).

Itis,inpart,thisspatialcomplexityoftheQEOPthatallowstheparktobesimultaneouslya spaceofinspiration,intrigue,andenergy,aswellasaspaceforrelaxation,forparkusers.This affectiveimpressionofcalmnessintheparkwasacommonthemerunningthroughmostofthe participants’encounterswiththepark:“itdoesn'tfeeltense,youknow?”(P13).Theparkactsas almostagreenretreatwithinthelifeworldsofitsusers,as“it'saniceplacetogoifyouwantto kindofrelaxandgetawayfromitforabit”(P8),adestinationforhaving“nice,chilled-out experience[s]”(P9)inwhatisotherwise“abitofaconcretejungle”(P9,referringtozone2/3 London):

youfeelabitlikeyou'vegotaminiholidaythere,youknow,it'slikewhatyou wouldnormallydoonholiday,you'dfindlike,uh,likereallybeautiful gardensorlikebeautifulsunnyspots…it'slikeit'sthatthinginsideyour normaleverydayenvironment,basically, likealittlepocketofholidayinside everyday.(P16)

Thisexperienceofrelaxationevenpersistswhentheparkwasbusy,partlybecauseofthelarge spatialextentoftheQEOP,as“modern,spacious,andclean”(P13),sothat“evenwhenit's busieronaweekend,Istillfeelveryrelaxed,becausethere'splentyofspacejusttositorlie down”(P5):

there'splentyofspace,soevenattheweekendinthesummerwhenit's busier,youneverfeelthatyou'rewithalotofpeople.Ifyouwalkupand downthecanal,wherethetowpathis,there'squitealotofcyclingalong there,thatcangetquitebusy,butonthewhole,theparkisnotthatbusy, whichisnice.(P14)

ThissensethattheQEOPalwayshasspacestorelaxand‘takeabreak’fromthebusynessof lifeisfacilitatedbythespatialcomplexityoftheQEOP:itisfullofcomplexvolumes,nooks,and cranniesthatfeel“organicallysecluded”(P5)fromtherestoftheparkandcity.Theseare “areasthatarealittlebitquieter”(P5),designedtobeplaceswhereparkuserscanseek respitefromthebusybike-filledconcourseandthechildrenplayingintheQEOP’swater featuresandplaygrounds(HopkinsandNeal,2013).

Thesecluded‘rooms’inthepleasuregardensoftheSouthParkexemplifythispoint(Figure21). Thephysicalseparationtheyhavefromtherestoftheparkmeansthateventhoughthese ‘rooms’andzonesarerightintheheartoftheSouthParkandconcourse,parkuserscanstill “reallyfeelinthemoment”(P13)evenif“someonewouldbepassingbyonabike”(P13).They are‘parkswithinapark’thatallowmultipleactivitiestogoonatonce(P13)withinasingle park.Abroadrangeofparkusersfoundthattheycouldfindspaceslikethisthroughoutthe parkwheretheycouldrelax(P5,P8,P14),andnotfeel“surroundedbypeople”(P14), especiallyintheNorthoftheparkandintheWaterglades(P15).Thisisbydesign,sothatthe QEOPisaparkforeveryone:

Ireallylikethefactthatitkindofincludeseveryone,that'swhatIthinkof whenIgotothepark,thatlikelotsofdifferentkindsofpeoplecanenjoyit, becausethere'ssomanydifferentkindsofthingsthere.(P15)

Astheexampleofhowparkusersencounterthe‘rooms’ofthe QEOPdemonstrates,thespatialcomplexityoftheQEOPwas encounteredbyparticipantsasgenerativeofasensethat differentspacesintheQEOPfeeldifferent.Thisaffectisalso volumetric,becausenotonlydodifferentareasintheQEOP havedifferentatmospheres,differentlevelsintheQEOPfeel different(Figure23).P15developsthispoint,astheyidentified adifferentsetofatmospheresintheirencounterswiththe concourseandlowerlevelsintheNorthPark:“whenyou'reon thetoplevelyoudofeelabitlike...yeah,you'rekindofgoing roundalittlebit”,constantlycirculatinginaconcrete wonderland,butasyouheaddownclosertotheriver:

itfeelsmorenatural,itfeelslike,oh,there's justapaththat'sgoingalongsidehere,and you'vegotthereedsanddifferentpartsofit, soitdoesn'tfeelas[designed]....And maybeyou'vegotafewbenches,butit'snot asmuch..yeah,itfeelsalotmorekindof 'lefttoit',abitmorewild,whichisalittlebit strange[laughs](P15)

Inasensethen,theriparianareasandlevelsoftheNorthPark bytheRiverLeafeelalmostasiftheyare‘notdesigned’,asifit “justevolvedtobelikethat”(P5).Thedifferent‘feel’ofthe differentlevelsintheQEOPcanevenbefunandengagingfor participantsencounteringthem,as,forexample,heading downtothecanalsintheSouthPark,ontoalowervertical level,evokesasenseofdiscovery:“you'rekindofunderthe surfaceifyouknowwhatImean?”(P13).

ThecomplexvolumesandspacesoftheQEOPflowandblur intoeachotherinandbeyondtheboundariesofthepark: “youjustwalkfromoneroomtoanotherdon'tyou?”(P4).This leadstoanaffectiveimpressionwheretheQEOPfeelslarger thanwhatistechnicallytheparkspace,somuchsothatsome participantswereunsureaboutwheretheparkstartedor ended.TheresultisthattheQEOPisencounteredasintegrated intoa“greencorridorthatisquiteuninterrupted”(P9), because,asP14explains,thepathslinkupwithothers,“soyou canwalkuptheLeeValley,youcanwalkbeyondtheparkup thatdirection,andyoucanwalkdowntotheThamesandlink upwiththepathsthere”.However,itisimportanttonotehere thatsomeparkusers,likeP7,feelthattheparkisnotconnected enough,asthepathsareoftensobusythatitcanbecome frustratingtogetfromA-to-B,wheretheflowsbetweenthe spacesandvolumesoftheQEOPcanbreakdown,choke-up, andbecome‘sticky’attimesofpeakusage.

Top:ThemainconcourseintheNorthPark,facingSouthtowardsthe ArcelorMittalOrbitsculpture

Bottom:ApathrunningthroughtheriparianhabitatsoftheNorthPark alongtheRiverLea(hiddenbehindvegetationintheleftoftheframe)

TheQEOP’svolumesandspacesmeldwith,andfold into,thesurroundingurbanfabrictosuchanextent that“it’sdefinitelyanurbanexperiencebeinginthe OlympicPark”(P16).Thisisunsurprising,becausethe masterplanforthearea,ofwhichtheQEOPisapart of,isaboutcreatingahybridlandscapethatrefuses dualismsbetweenhumans/nonhumans,city/nature, andpark/city,‘stitching’theQEOP,in‘legacymode’, backintotherestofEastLondon.Parkusersencounter theQEOPashybrid,justasmuchasitisdesignedas hybrid,asP16explains:

it'sgettingmoreandmorebuiltup aroundStratford,andthere'slike bighighrisescomingup,there'slike majorbuildingsiteswherethey're buildingtheSadler'sWellsthing, thatmakesitlooksuperurban,so you'retotallyremindedlikethat, you'reinthis..likeitdoesn'treally, youdon'treallygetcompletely forgetaboutthefactyou'reinthe city,yeah.You'restillinnature withinthecity.(P16)

Whilethisisnotalwaysthiscase,thehybridityofpark users’encounterswiththeQEOPmeansthatthepark doesnotresultinafeelingof“gettingoutofitalittle bit”(P15)orrelaxation,“evenintheNorthPark” (P15),assomeparticipantsalwaysfeltclosetocafes, roads,andnoise,alwayssawbuildingsandcranes, andfeltliketherewastoomuchtarmacorconcrete whentheywereintheQEOP(P7,P12,P15),in comparisontoparkslikeVictoriaPark,whichwas describedaslikeagreen‘bubble’separatefromthe restofthecity(P15).

So,theQEOPisclearlyencounteredasamore-than parkbyitsusers,asitmeldstogethercity/natureand park/cityintoaseriesofhybridisedexperiences. However,therearealsoplantings,habitats,andwater spacesembeddedwithintheQEOPthatgenerate more-than-humanexperiencesandencountersinthe park,whichthisdissertationnowturnstoconsider.

AviewSouthwardsunderabridgeintheNorth Park.Noticetherichriparianhabitatsoneach bankoftheRiverLeaontheright-handside

Howdoparkusersencountertheplantings andconstructedhabitatsoftheOlympic Park?

ParkusersencountertheQEOPasahybridblend ofmanicuredandwild:wildinplacesliketheNorth Park,where“itfeelslikeyou'rewalkingina meadow,ratherthaninaCityPark”(P13),andas manicuredinthemoreformalgardensoftheSouth Park(P2).Thetextureandroughnessofthe meadowsdistributedthroughouttheparkwas especiallyappreciated,as“otherparksdon't usuallyhavethat”(P7),sothatalthoughthe landscaping“isbydesign,[…]itlookslikeit’snot designed”(P7,Figure26).Andthesemeadows bloomwithvibrantcolours(P4):“Ireallylikehow theyputflowerbedsandmeadows[together],how they'redesignedsotheyflowerandarereally colourfulinthesummer”(P7).

Becauseofthis,parkusersfrequentlysaidthatthe QEOP’splantings,given“theefforttheytaketo keepthatup”(P14),weresomeoftheirfavourite qualitiesabouttheQEOP(P5):simply“amazing” (P2).Since“mostofthat[theecologicalplanting]is ontheedgeofthewateraswell”(P14),adeeper affectofimmersionandseclusionisgeneratedin thewateryandecologicalspacesoftheNorth Park.Seeingtheflowers’colours,smellingtheir perfumes,andhearingtheplantsrustleinthewind isamore-than-humanpracticethatdelivers wellbeingbenefits,astheflowersandplantings affectvisitorsandencourageasenseof refreshmentorrelaxation,apracticedescribedin onecaseas“quiteatreatthinglikeIdoformyself, liketojuststopandobserve”theflowersand plantings(P5).

Andtheseflowersandplantingsarenotstatic,they arenonhumanagentsenrolledintheprovisionof dynamicparkexperiencesthatchangethrough time(Ernwein,2021;Figure25).Thesebringlifeto thehard-surfacedcharacterofsomepartsofthe park:“inthelastfewweeks[August2021]when theyallreallychanged,theybroughtsomuchjoy, andIthoughtwow,Ihadnoideathatallthese amazingcolourswerethere-Ithoughtthatitjust reallybroughtlikeahappinesstotheconcrete jungle!”(P11).Boldblues,oranges,andpurples abound:“they'rejuststriking”(P4).

Figure25 The2012GardensintheSouthPark,runningalongWaterworksRiver,astheychangethroughtheseasons

Figure26

Thelushvegetation oftheriparian habitatsand wetlandbowlofthe moreecological NorthPark

Thescaleandcohesionwithwhichthesebold,intricate, seasonal,andfragrantdisplayshavebeendesigned particularlyimpressedparkusers(P5,P7):“obviouslyin Londonwehavequitealotofgreenspace,butit'smostlylike openparksandtrees,andIreallylovetheflowers,becauseI don'tgetthatalotnearwhereIlive,asit'sreallybeautifulto see,like,thedifferentheightsofflowers,thescentsare amazing,andalsothebutterfliesandbeesattractedtoit,and that'sjustreallynicetosee”(P5).“It'sjustamazinghowmany coloursandbeautifulflowersthereareina,youknow,a reallywildsortof,um,garden.Itcaughtourattention”(P4), as“even‘weeds’[…]lookprettyamazing[laughs]”(P4),but “it's[also]theperfumethattakesyoufromtimetotime”(P4). Theplantswereoftensoengagingorunusualthatparkusers tookphotosorusedidentificationguidesorbookstofindout whattheywere(P4,P12)-”that’showinterestingtheplanting is!”(P4)-andsaidtheywouldbekeentolearnmoreabout identifyingwildlifeintheparkthroughpamphletguidesor augmentedrealityexperiences(P4,P12):

Ithinktheyshouldgetmoretoolsforthat. Peoplewillbereallyinterestedtoknow moreaboutthewildlifeandidentification andunderstandlike...thattherearesome poisonoustypes,forexample,likehemlock, anditwouldbegreattobeabletoidentify those.(P12)

TheQEOP,asitweaveshabitatsandrecreationalspace togetherinavastsocio-ecologicallandscape(Figure27), wasencounteredbymanyparkusersasmorethanjustabout flowersandplantsasnonhumanpresences:othercreatures liveinit.Thecollisionofthesenonhumanlifeworldswiththe livesofhumanparkusersbroughtdelighttoparticipants, especiallyduringtheCOVID-19lockdownsof2020and 2021:“it'sreallynicetohavethenature,andtobeexposed toit,it'ssorelaxing”(P9).

Thesenonhumanencountersarebothsmallandlarge, incidentalandepisodical.Butevensmall,shortencounters betweenhumanandnonhumanlivesintheQEOPcanbe powerfullyaffectiveandgenerativeofexcitement,delight, andjoy,especiallywhentheyareuniqueormemorable,as thefollowingencounterbringstolife:

maybearound,Iguess,June,Julytime, therewasabeetlelikethisbig[gestures usinghands],sothat'smaybeaninch,and itwasturquoiseandmetallic,anditwasjust sosurprisingtosee,right?Itookapicture. […]Itwasjustreallyexcitingandreally… 'causeIseequitealotofbumblebeesand sometimeshoneybeesaswell,um,and butterflies,but[…]toseethebeetlewas quiteunique.Soyeah,thatwascool.(P5)

Swansandgeeseinthewaterwayswereparticularhighlightsformanypark usersinterviewed,astheyrecountedtheirdelightatfollowingtheirlifecycles throughouttheyear(P5,P9,P11)andduringtheCOVID-19lockdowns:

[FromSpringtoSummer2021]Ifollowed-itsoundsreally crazy-butIfollowedthelivesoftheselittleswans!So, there'sapairofswans,andthentheyhadbabies,andthen thebabiesalldied,andIthinkthemomdied,sothatwas [notnice],butyouknowhowitisinlockdown:youjustfind joyandafocusinsmallerthingsthanyouwouldhave usually,soformeitwaslikealltheswans,likeI'dgoonmy walkandseethem,andIchattedwithoneofthesecurity guardsatthestadium,whosaidshesawthemeveryyear andshetoldmethewholestory,sotheywerethenature starsoftheshow!(P11)

justoffFishIsland,wehadeightcygnetstheotherday.I've neverseeneight,andtheyweren'tlikebabies,theywere huge!Soyeah,I'veneverseensomanytogether[before], soIwasquiteimpressed![laughs]Butstufflikethat'sreallynice(P5) Andthisispartofacollectiveactivityofencounteringandfollowingthelives ofthenonhumaninhabitantsoftheQEOP:

there'stwogeesethatlivethere[intheriver],[and]when they'rebackandhavingtheirgoslings[…]theWhatsApp groupslikeexplode-it'sabitofagroupactivity,uh,so that'sprettynice.(P9)

Otherbirdsmakeparkusers’encounterswiththeQEOP’slandscape delightful(P5,P6,P8,P14,P15),especiallyduringtheCOVID-19lockdowns, and“that'sreallylovely[…][because]youdon'tgetsomuchwildlifeinthe city,soyeah,there'salot,there'salotofdiversitywhenyouthinkaboutitin suchasmallarea”(P5).“Ithinksomeofthebirdsarethenicest,Ithink seeingthekingfishersisthemostkindofexcitingthing,probably”(P8),and theseencountersare“quiteuplifting:it'squite,itkindofmakesyoufeelagain thatyou'rekindofpartofnature,andthateveninthecityyou'vegotother wildlife,whereastherearetimeswhenitcanfeelquitedevoidofanything, youknow,youmightseeafoxorsomething,butthat'saboutall.Whereas[in thepark]itreally...itreallyfeelslikethere'smore...kindofaroundyou.”(P8, Figure28)

Itisthissenseof‘morearoundyou’thatrunsthroughsomanyparkusers’ accountsofhowtheyuseandencounterthepark’sspaces,habitats,and plantings:thatitprovidesopportunitiesfor‘contactwithnature’,forhuman andnonhumanlivestointeract,asintegratedintotheveryexperienceand practiceofgoingtotheQEOP(Kaplanetal.,1998).

Placestositandsoakinasenseoftherebeing‘morearoundyou’(P8)intheAsianGardens (SouthPark,top)andonKnights’Bridge(NorthPark,bottom)

Howdoparkusersencounterwaterin theOlympicPark?

TheRiverLeaandassociatedwaterwaysinthe QEOPwerestand-outfeaturesformanyof participantsinterviewed,as“anicefeature whichyoudon'tgetinalotofotherparks” (P8).

TheQEOPwasencounteredasputtingwater front-and-centre,sothatthereareplentyof opportunitiestoencounterwaterinthepark. Theseencountersandopportunitiestositor walkbywaterwereconsideredrestorativeeven atpeaktimesinthepark(P2,P8,P13,P14),so that“evenwhenit'sbusy,there'snearlyalways somewhereyoucanfindtosit.It'sneverthat busy”(P8)intheNorthParkbytheRiverLea. Thisiswhat(re)producesanaffective atmosphereinthischaracterareaoftranquillity, relaxation,andpeacefulness(P13,Figure29), astheNorthParkis“notreallyonthewayto anywhere,soyouonlygothereifyouwantto sitquietly”(P8),whereastheSouthParkis whereyou“getalotofpeoplewalkingacross theparkandgoingbetween,like,Hackney WickandStratfordandstuff-sothere'salot morepeopleusingit”(P8quoted;P15).

Becauseofitslowerfootfall,ecological characterandthepresenceoftheRiverLea,this zoneintheNorthParkcreatesasenseof gettingoutofit,whereparticipants“feellike you'reoutofthecity,likeyou'retransported somewhere”(P15):

IfI'mgoingtositoutinthe park,I'lltendtositbythe riverratherthanjust anywhereelse,'causeIthink theriverisreallycalming, andit'salsoquieter.Youkind of,sometimes,ifyou'reonthe edgeofthepark,you'vegot theroad,oryou'vegotother thingsaroundtheedgesof thepark,whereaswhen you'rebytheriver,it'sreally quietandyoukindoffeellike you'renotalwaysnotin London,you'rekindof,yeah, somewhereelse.(P8)

So,beingbythewaterintheparkoftenofferedasenseofimmersionforparticipants, augmentedbyhighlevelsofplantingbythewater’sedge(P14,Figure30).Multi-sensory encounterswiththesefeaturesoftenresultedinasenseofrelaxationandtranquillityforpark usersasthewatersintheQEOParegenerativeofvisual,acoustic,andolfactibleatmospheres:

Ithinkit'saveryhumanthingtojustwatchwater,andit'sjustveryrelaxing and,especiallylikeIsaid,wetalkedaboutitbefore,soyoucangodownto beabitclosertoit.Andstupidthings,likeIlikethesmellofityouknow?(P5)

it'sreallynicetohavethenature,andtobeexposedtoit,it'ssorelaxing,it's sonicetohearrunningwater(P9)

Theseaffectsofimmersionandrelaxationaremaintaineddespitetheintroductionofhard infrastructureofbridges,paths,andseatingintothelandscapetofacilitateitsrecreationaluse (P12),becausethewater,city,andparkaredesignedandintegratedtogether(P10)inaway thatallowsanencounteroftheRiverLeaas“weav[ing]itswaythroughtheparkreally organically”(P5).

Thedesignoftheparkcelebratesthearea’sindustrialheritage,aslockshavebeenrepaired, channelsmadenavigableagain,andriverwallsrestored,embracingthecanalsandriversand theirindustrialheritage,ratherthanneglectingthemasinconvenientleftoversofanindustrial agebygone(P5,Figure31).Thiseffortto‘keepintouch’withthearea’spastisappreciatedby parkusersencounteringtheQEOP’swateryspaces(P5),as“thiswholebitofthecityiswaterbased,likewiththecanalsrunning,youknow,upRegent'sCanalandthecanalsrunningdown toCanaryWharf,soIthinkit's[…]sortofkeepingintouchwiththenaturalsortoflandscape outhere,eventhoughtheparkisverymanicured[laughs]formostofit”(P10).

Makingthesechannelsnavigableagainallowsparkusers,likeP12,totaketheirboatsintothe canalsandRiverLeaforrecreationaluse,butthereisanotablelackofinfrastructureinthepark tosupportboatlaunches.Thismakesitverydifficultforparkuserstoactuallygetontothe water,leadingtoexperiencesoffrustrationthattheyhave“toinflateit[athome][…]andthen walkwithitatleasttenminutestothepartwhereyoucanactuallyputitdown”(P12).Outletsto inflateboatsintheparkandboatlaunchingstationswouldenableamoredirect,and convenient,encounterwiththeQEOP’swaterspacesthroughwatersportpractices.Thereare, however,boatandpedalohireoptionsintheparktoenablecontactwiththewaterbybeingon thewater.Asoneparticipantexclaims,“I'venevertakenoneoftheboatsorthepedalosout thatyoucanhire,[whispers]they'requiteexpensive![laughs]Butit'snice,Ithink,thatyoucan dothatifyouwantedto.”(P5)

Someparticipantsencounteredthewaterasadynamicdesignelementinthepark,with changinglevels(P2),flowspeeds(P14),andwaterquality(P5),whichaddedatemporal dimensiontoencounterswiththeQEOP’sdesignedspaces.Thisdynamismwasmoreoften encounteredinthemoreecological,waterlandscapeoftheNorthPark,wherewetlandsare inundatedintimesofhighflow,butalsointheSouthPark,bytheWaterworksRiver,where someparticipantsobservedatidemarkofmudonthecolouredcrayonsoutsidetheAquatic Centreasindicativeofchangingwaterlevelsovertime(P3,Figure32).

ThisdynamismmeantthattheQEOP’sdesignedspaceswereencounteredbyparticipantsin differentwaysduringdifferentstatesofriverflow,andthecontrastsbetweenthesestateswere oftenasourceofintrigue:

it'squiteinterestingtoseeanareathatinthepastyou'vewalkedthroughand justseeitcompletelyunderwater[…]andthen[seeit]evenjustacoupleof dayslaterasbacktobeingwhatitwasnormallylike,andthenyoucan't quiteimaginethattwodaysagoitwasallunderwater.(P8)

it'salwaysinterestinglikewhenyouseeitfloodedandthenyougoliketwo monthsafterthatandyoucanseewherethewaterusedtobe,right(?),then that'sinteresting.(P2)

Thisintrigueinseeingtheparkasa‘waterlandscape’,inadifferent,floodedconfigurationtoits ‘normal’state,iswhythelowerpathsbeingclosedwheninundatedintimesoffloodismore somethingofinterestthanofannoyance(P15),especiallysincetheinundationoftheNorth Park’swetlandbowlbytheRiverLeaisnotveryfrequent:“[i]t'sprobablylikeaonceayear occasion,it'snotsomethingthatyousortofseeregularly,like,oh,it'sfloodedagain,it'snotan annoyance”(P9).AsP2putsit:“Ihaveneveractuallyseenitasaproblem,butIthinkit'sa feature”(P2).

Anditisafeaturethatlooksdramatic(P6,Figure33),somuchsothatthefloodingofthepark alarmssomeresidentswhentheyfirstmovethere,perhapsduetoalackofobvious interpretativesignageintheparkexplainingthewater-sensitivedesignoftheecologicalNorth Park(P1,P4),asP6recounts:

You always getphotosonthelocalFacebookgroup.It'susuallypeoplewho justmovedinwhogo:"OhmyGod,what'shappenedtothepark?It's underwater!"Andthenyougetthelongtermresidentsgoing:"It'sfine.Don't worryaboutit,bytomorrowit'llbegone.”(P6)

Butitisalsopreciselythisdramaticisationoffloodandriverdynamicsthroughthepark’s landscapingthatisgenerativeofgreaterawarenessoffloodriskandthehydrologicalimpacts ofclimatechangeamonglocalresidents.Encounteringtheriverinahighflowstate,in conjunctionwiththeconsumptionofarticlesinmediaoutletsaboutincreasedfloodriskin Londonduetoclimatechange,wasoftencitedaspromptingareflectiononchanginglevelsof floodriskintheareaaroundtheQEOPandwhethertheThamesBarrierwillbeadequatefor protectingLondoninthelong-term(P4,P14).

Whentheriverisflowingfaster,buthasnotyetbreacheditsbanks,parkusersareoften allowedtogodowntothewater’sedgeandseetheriverandnoticehowfastitisflowing(P15). Thismakestheconstantlychangingstatesoftheriverafeatureoftheparkratherthana problemtobehiddenaway.Encounteringthisfeature,forparkusers,isaboutexperiencinga contrastingstateoftheRiverLeathatisverydifferenttoitsconditionoflowerflowinthe summer,somethingwhichseveralintervieweesappreciated:

I'vestoppedtowatchitbeforewhenit'smovingreallyfast,just'cause,um,I justfinditreallyinteresting,andyoudonoticethedifference.Idon'treally feelstressedbyit,andIquitelikethatthere'stheoptiontolikeenjoyitwhen it'slow,andthenforittonotbe...likenormally,Ithinkinotherplaces,ifit wasmaybegoingtogetflooded,they'djustnotletyouwalkonitatall,butI likethefactthatwhenit'snotgoingtobeflooded,youcanstillwalkcloseto it,andwhenitis,OK,maybeyoujustcan'tgotherethatdayoftheweek, right?SoIlikethat.(P15)

ThisallowsforgreaterinteractionandconnectionwiththeRiverLea,asanonhumanactant,in theriversidespacesoftheNorthParkduringtimesofhigherflow:“likepeopledroppingsticks andjustobserving,orlikeseeingthewildlifeinteractwiththedifferentstateofit.So,Ithinkit [beingalloweddowntothewater’sedgeduringtimesofhigherflow]allowsyoutodothatyoufeelalotmoreconnectedtoit.”(P15).

Itisimportanttonote,however,thattheselivedexperiencesandencounterswiththewater spacearenotauniversalexperience,especiallysincethewaterlevelsintheQEOPareso dynamicandcanchangeatadailyorevenhourlytemporalscale,sosomeparticipantshadnot seenwaterlevelschanginginthepark(P7)oranyflooding(P5).

NorareexperiencesoftheQEOPfloodingentirelypositive,especiallyinparticipants’accounts ofthelateJuly2021floods,wherethePuddingMillandHackneyWickDLRStationsbecame inundatedwithstandingwaterandsubjecttohighlevelsofsurfacerun-off:“Imean,solasttime […]whenwehadthefloods,PuddingMillDLR,whichisdownbytheoppositeendofthepark, liketheyhadlike,what,sortofametreandahalfofwaterorsomething![laughs]Likesomuch water!”(P10).Effectiveat-sourcestormwatermanagementandriverrehabilitationdemandsthe introductionofpermeablesurfacesandat-sourcerainwatercapturethroughouttheurban catchment,andnotjustinafewselectareas.TheQEOPmaymanagewaterwellandbe generativeofdelightfulexperiencesbyemphasisingthedynamicsoftheRiverLea,butthiscan benegatedbyinadequateimplementationofSUDSdesigninareasadjacenttothepark (Walshetal.,2005).

Thisdissertationhasintroducedtheconceptualframeworkoftheriverineparknexusand applieditinthecontextoftheQueenElizabethOlympicPark,interrogatinghowusersofthe OlympicParkencounterandexperienceitsdesignedspaces(HopkinsandNeal,2013).

AsexploredinChapter4,theQEOPcollapsesacity/naturedualismingenerative,landscapescale,andforward-thinkingwaysthroughamore-than-human,hybriddesignapproach (Waldheim,2002,2011;HinchliffeandWhatmore,2006;HopkinsandNeal,2013)that integratestherecreational,ecological,andhydrologicalconcernsoftheriverineparknexusin novel,fluid,andstrikingconfigurations(HopkinsandNeal,2013).However,theQEOPisnot onlydesigned,butisalsoencounteredbyparkusersasaseriesofmore-thanspacesthatare dynamic,complex,andlived-inbyhumansandnonhumans.Itisvitaltoconsiderhowpark usersencounterandanimatethespacesandvolumesoflandscapesliketheQEOPbecause urbanparksaredesignedforpeople(Kaplanetal.,1998).

Chapter5,AffectiveImpressions,consideredhowparkusersencounterandareaffectedbythe designedspacesandvolumesoftheQEOP,arguingthattheparkisliveability-oriented,inthat itisgenerativeoflargelypositiveaffectiveimpressionsofinspiration,intrigue,energy,and relaxationforthosethatencounterit.Itwassuggestedthatthecomplexcharacterofthespaces andvolumesoftheQEOP,consistingofaseriesofzonesandlevelsthatrunintoandblurinto eachother,createsaseriesof‘parkswithinparks’,eachwithadifferentatmosphereandpalette oflatentpotentialities,accommodatingcontrastingexperiencesandpracticeswithinthe singularityoftheQEOP(Degenetal.,2008;Gandy,2017).

AffectiveImpressionsalsoarguedthatparkusersencountertheQEOPasahybridlandscape thatmeltstheboundariesbetweennotonlyhumans/nonhumansandcity/nature,butalso park/city,innovel,generative,and,attimes,jarringways,ashumanandnonhumanworlds collide(HinchliffeandWhatmore,2006).Thedesigned‘blurring’or‘stitching’ofparksintothe restofthecity,however,isnotalwaysfavouredorrelaxingforthosewhousethem.Takingthe QEOPasmore-than,asasitewherehumanandnonhumanlivesandpracticesintermingle, providedagatewayintotherestofthedissertation’sdiscussion.

TurningtoconsiderhowhumanparkusersencounteredthenonhumanresidentsoftheQEOP, Chapter6arguedthatopportunitiesforcontactwith‘nature’areembeddedintheecologicallymindfuldesignedspacesoftheQEOP,andthattheseopportunitieswerefrequentlygenerative ofdelightfulexperiencesforparkusers:rangingfromenjoyingtheperfumesofflowers, followingthelifecyclesofswansinthewaterways,andhavingasensethatthereis‘more aroundyou’.Inthisway,parkusers’encounterswiththeQEOP,becauseofhowitdeploys ecologicalapproachestoriverineparkdesign,aredistinctivelymore-than-human.Designing riverineparkstohavehighlevelsofhabitatcomplexity,astheQEOPdoes(HopkinsandNeal, 2013),isseemingly,then,aproductivestrategyforincreasingopportunitiesforinteractions betweenhumanandnonhumanlivesinriverineparks(Kaplanetal.,1998;Malleretal.,2006; Fulleretal.,2007).

Chapter7arguesthatmore-than-humanencounterswiththeQEOParealsomore-than-animal andmore-than-plant,aswatergainedagencyinparticipants’encounterswiththeQEOP, designedtoworkwithwater,asnonhumanactant,throughwater-sensitivehydrologicaldesign strategies.Water,intheQEOP,yieldsarestorativeaffectof‘gettingoutofit’,asenseof immersionenabledbytheintegrationofwater,city,andparkintheQEOP’slandscapedesign. Partofthisintegrationofwaterwiththerestofthepark’slandscapingwasaboutcreatingspace fortheriver’sdynamicstooperate,andtosurface.ThisexposureoftheRiverLea’sdynamicsin the‘waterlandscape’oftheQEOPoftenevokedasenseofintrigueandcuriosityamongpark users,suggestingthatspotlightingriverdynamicsthroughriverrehabilitationcandeliver benefitstoparkusersbeyondimprovementsinfloodprotectionandhabitatquality(Manning, 1997;vanStokkometal.,2005;Prominskietal.,2017).

Thisdissertationdemonstratesthatthedeploymentofrecreational,ecological,andhydrological strategiestowardsriverineurbanparkdesign,inawaythatrideswiththemessinessofcitiesas hybridandmore-than-human(HinchliffeandWhatmore,2006),isnotonlybeneficialfor urbanhydrologyandecology,butcanalsocontributetodelightful,intriguing,andrestorative experiencesforhumanparkusers(Kaplanetal.,1998).

Althoughthisdissertationhasattemptedtoexplorehowriverineparksareencounteredandthe riverineparknexusislived-in,itfocuses,primarily,onacasestudyoftheQEOP.Thereisan urgentneedtoconsiderhowtheriverineparknexusisencounteredinabroaderspatial context,especiallyinless‘spectacular’riverineurbanparks(Prominskietal.,2017).

Thequestionremains:arehybridliveability-oriented,ecologicallymindful,andwater-sensitive approachestolandscapearchitecturethefutureofriverineparkdesign?Theanswerisnota one-size-fits-all,butitislikelythattheapproachesunderpinningtheriverineparknexuswill formabackboneoftheriverineurbanparksofthefuture.

Abercrombie,P.(1945)GreaterLondonplan:1944. London:HMStationeryOffice.

Adams,W.M.(1996)‘Creativeconservation, landscapesandloss’,LandscapeResearch,21(3),pp. 265–276.doi:10.1080/01426399608706492.

Allan,J.D.etal.(1997)‘Theinfluenceofcatchment landuseonstreamintegrityacrossmultiplespatial scales’,FreshwaterBiology,37(1),pp.149–161. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2427.1997.d01-546.x.

Anderson,B.(2009)‘Affectiveatmospheres’, Emotion,SpaceandSociety,2(2),pp.77–81. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2009.08.005.

Barbaux,S.(2015)‘Foreword’,inICIConsultants (ed.)Spongecity:waterresourcemanagement. Mulgrave,Victoria:ImagesPublishing,pp.3–5.

Bloor,S.(2014)‘AbandonedAthensOlympic2004 venues,10yearson–inpictures’,theGuardian,13 August.Availableat:http:// www.theguardian.com/sport/gallery/2014/aug/ 13/abandoned-athens-olympic-2004-venues-10years-on-in-pictures(Accessed:13October2021).

Böhme,G.(2014)‘UrbanAtmospheres:Charting NewDirectionsforArchitectureandUrbanPlanning’, inBorch,C.(ed.)ArchitecturalAtmospheres.DE GRUYTER,pp.42–59. doi:10.1515/9783038211785.42.

Booth,D.B.andJackson,C.R.(1997)‘Urbanization ofaquaticsystems:degradationthresholds, stormwaterdetection,andthelimitsofmitigation’, JournaloftheAmericanWaterResources Association,33(5),pp.1077–1090.doi:10.1111/ j.1752-1688.1997.tb04126.x.

Bradley,C.andMillward,A.(1986)‘Successful greenspace—doweknowitwhenweseeit?’, LandscapeResearch,11(2),pp.2–8. doi:10.1080/01426398608706191.

Braun,B.(2005)‘Environmentalissues:writinga more-than-humanurbangeography’,Progressin HumanGeography,29(5),pp.635–650. doi:10.1191/0309132505ph574pr.

Brown,T.andBrown,B.(2018)‘Sitingreassemblage:QueenElizabethOlympicPark’,Journal ofLandscapeArchitecture,13(3),pp.40–53. doi:10.1080/18626033.2018.1589134.

Burgess,J.etal.(1988)‘People,ParksandtheUrban Green:AStudyofPopularMeaningsandValuesfor OpenSpacesintheCity’,UrbanStudies,25(6),pp. 455–473.doi:10.1080/00420988820080631.

Burns,M.J.etal.(2012)‘Hydrologicshortcomingsof conventionalurbanstormwatermanagementand opportunitiesforreform’,LandscapeandUrban Planning,105(3),pp.230–240.doi:10.1016/ j.landurbplan.2011.12.012.

Cairns,J.(1988)‘RestorationandtheAlternative:a ResearchStrategy’,Restoration&Management Notes,6(2),pp.65–67.Availableat:https:// www.jstor.org/stable/43439291(Accessed:23 October2021).

Cairns,J.(1989)‘RestoringDamagedEcosystems:Is PredisturbanceConditionAViableOption?’,The EnvironmentalProfessional,11,pp.152–159.

Chocat,B.etal.(2001)‘Urbandrainageredefined: Fromstormwaterremovaltointegratedmanagement’, WaterScienceandTechnology,43(5),pp.61–68. doi:10.2166/wst.2001.0251.

Clarke,S.J.etal.(2003)‘Linkingformandfunction: towardsaneco-hydromorphicapproachto sustainableriverrestoration’,AquaticConservation: MarineandFreshwaterEcosystems,13(5),pp. 439–450.doi:10.1002/aqc.591.

Coles,P.etal.(2012)‘SeeingtheOlympics:images, spaces,legacies’,VisualStudies,27(2),pp.117–118. doi:10.1080/1472586x.2012.677247.

Corner,J.(2006)‘TerraFluxus’,inWaldheim,C. (ed.)Thelandscapeurbanismreader.NewYork: PrincetonArchitecturalPress,pp.21–34.Available at:https://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/ login?url=http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ oxford/detail.action?docID=3387326(Accessed:6 January2022).

Cotton,J.(2018)‘TheEastEndisthenewWestEnd’: London2012andResidentExperiencesoftheUrban Changesinapost-OlympicLandscape.PhD. BournemouthUniversity.Availableat:http:// eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/31509/1/ COTTON%2C%20Jordan%20David_M.Res._2018.p df.

Daniel,T.C.etal.(2012)‘Contributionsofcultural servicestotheecosystemservicesagenda’, ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciences, 109(23),pp.8812–8819.doi:10.1073/ pnas.1114773109.

Davis,J.(2014)‘MaterialisingtheOlympiclegacy: designanddevelopmentnarratives’,arq: ArchitecturalResearchQuarterly,18(4),pp. 299–301.doi:10.1017/s1359135515000032.

Dawson,J.andJöns,H.(2018)‘Unravellinglegacy: atriadicactor-networktheoryapproachto understandingtheoutcomesofmegaevents’,Journal ofSport&Tourism,22(1),pp.43–65. doi:10.1080/14775085.2018.1432409.

Dawson,J.O.(2017)Theimpactsofmegaevents:A casestudyofvisitorprofiles,practicesand perceptionsinTheQueenElizabethOlympicPark, EastLondon.PhD.LoughboroughUniversity. Availableat:https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/ 288360374.pdf.

DeCerteau,M.de(1984)Thepracticeofeveryday life.Berkeley;London:UniversityofCaliforniaPress.

Degen,M.etal.(2008)‘ExperiencingVisualitiesin DesignedUrbanEnvironments:LearningfromMilton Keynes’,EnvironmentandPlanningA:Economyand Space,40(8),pp.1901–1920.doi:10.1068/ a39208.

Dreiseitl,H.andGrau,D.(eds)(2012)Recent Waterscapes,RecentWaterscapes.Birkhäuser. Availableat:https://ezproxyprd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2200/document/doi/ 10.1515/9783034615877/html(Accessed:16 December2021).

Dufour,S.andPiégay,H.(2009)‘Fromthemythofa lostparadisetotargetedriverrestoration:forget naturalreferencesandfocusonhumanbenefits’,River ResearchandApplications,25(5),pp.568–581. doi:10.1002/rra.1239.

Dyckhoff,T.andBarrett,C.(2012)Thearchitectureof London2012.Chichester:Wiley.

Ebbensgaard,C.L.(2017)‘“Ilikethesoundoffalling water,it’scalming”:engineeringsensoryexperiences throughlandscapearchitecture’,culturalgeographies, 24(3),pp.441–455. doi:10.1177/1474474017698719.

Eden,S.etal.(2000)‘Translatingnature:river restorationasnature-culture’,Environmentand PlanningD:SocietyandSpace,18(1),pp.258–273. doi:10.1177/026377580001800101.

Elosegi,A.etal.(2010)‘Effectsof hydromorphologicalintegrityonbiodiversityand functioningofriverecosystems’,Hydrobiologia, 657(1),pp.199–215.doi:10.1007/ s10750-009-0083-4.

ErixonAalto,H.andErnstson,H.(2017)‘Ofplants, highlinesandhorses:Civicgroupsanddesignersin therelationalarticulationofvaluesofurbannatures’, LandscapeandUrbanPlanning,157,pp.309–321. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.05.018.

Ernstson,H.(2013)‘Thesocialproductionof ecosystemservices:Aframeworkforstudying environmentaljusticeandecologicalcomplexityin urbanizedlandscapes’,LandscapeandUrban Planning,109(1),pp.7–17.doi:10.1016/ j.landurbplan.2012.10.005.

Ernstson,H.andSörlin,S.(2013)‘Ecosystemservices astechnologyofglobalization:Onarticulating valuesinurbannature’,EcologicalEconomics,86, pp.274–284.doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.09.012.

Ernwein,M.(2021)‘BringingUrbanParkstoLife:The More-Than-HumanPoliticsofUrbanEcological Work’,AnnalsoftheAmericanAssociationof Geographers,111(2),pp.559–576. doi:10.1080/24694452.2020.1773230.

Everard,M.andMoggridge,H.L.(2012) ‘Rediscoveringthevalueofurbanrivers’,Urban Ecosystems,15(2),pp.293–314.doi:10.1007/ s11252-011-0174-7.

Ferreri,M.andTrogal,K.(2018)‘“Thisisaprivatepublicpark”:Encounteringarchitecturesofspectacle inpost-OlympicLondon’,City,22(4),pp.510–526. doi:10.1080/13604813.2018.1497571.

Firth,K.andPatel,M.(2014)‘RegenerationforAll Generations:TheQueenElizabethOlympicPark’, ArchitecturalDesign,84(2),pp.88–93. doi:10.1002/ad.1733.

Fuller,R.A.etal.(2007)‘Psychologicalbenefitsof greenspaceincreasewithbiodiversity’,Biology Letters,3(4),pp.390–394.doi:10.1098/ rsbl.2007.0149.

Gandy,M.(2002)Concreteandclay:reworking natureinNewYorkCity.Cambridge,Mass.;London: MITPress(Urbanandindustrialenvironments).

Gandy,M.(2017)‘Urbanatmospheres’,cultural geographies,24(3),pp.353–374. doi:10.1177/1474474017712995.

Gibbons,A.andWolff,N.(2012a)‘GamesMonitor: UnderminingthehypeoftheLondonOlympics’,City, 16(4),pp.468–473. doi:10.1080/13604813.2012.696914.

Gibbons,A.andWolff,N.(2012b)‘Introduction:RewritingLondonandtheOlympicCity:Critical implicationsof“Faster,Higher,Stronger”’,City, 16(4),pp.439–445. doi:10.1080/13604813.2012.713171.

Gold,J.R.andGold,M.M.(2008)‘OlympicCities: Regeneration,CityRebrandingandChangingUrban Agendas’,GeographyCompass,2(1),pp.300–318. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00080.x.

Gold,J.R.andGold,M.M.(2019)‘Talesofthe Olympiccity:Memory,narrativeandthebuilt environment’,ZARCH,(13),pp.12–33. doi:10.26754/ojs_zarch/zarch.2019133954.

Goldby,N.andHeward,I.(2013)‘Designingout crimeinthedeliveryoftheLondon2012Olympic GamesandthefutureQueenElizabethOlympic Park’,SaferCommunities,12(4),pp.163–175. doi:10.1108/sc-07-2013-0013.

Gómez-Baggethun,E.andBarton,D.N.(2013) ‘Classifyingandvaluingecosystemservicesforurban planning’,EcologicalEconomics,86,pp.235–245. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.019.

Gray,C.(2011)‘LandscapeUrbanism:Definitions& Trajectory’,Scenario[Preprint],(1).Availableat: https://scenariojournal.com/article/landscapeurbanism/(Accessed:25February2021).

Haraway,D.(1988)‘SituatedKnowledges:The ScienceQuestioninFeminismandthePrivilegeof PartialPerspective’,FeministStudies,14(3),pp. 575–599.doi:10.2307/3178066.

Hargreaves,G.etal.(2009)Hargreaves:the alchemyoflandscapearchitecture.London:Thames& Hudson.

Harris,A.(2015)‘Adventuresintheartofdissentand London’sOlympicState’,City,19(1),pp.121–125. doi:10.1080/13604813.2014.991170.

Harrison,P.(2000)‘MakingSense:Embodimentand theSensibilitiesoftheEveryday’,Environmentand PlanningD:SocietyandSpace,18(4),pp.497–517. doi:10.1068/d195t.

Hartman,H.(2012)‘IsSustainabilityJustAnother “Ism”?’,ArchitecturalDesign,82(4),pp.136–140. doi:10.1002/ad.1444.

Hayes,G.andHorne,J.(2011)‘Sustainable Development,ShockandAwe?London2012and CivilSociety’,Sociology,45(5),pp.749–764. doi:10.1177/0038038511413424.

Hinchliffe,S.andWhatmore,S.(2006)‘Livingcities: Towardsapoliticsofconviviality’,ScienceasCulture, 15(2),pp.123–138. doi:10.1080/09505430600707988.

Hopkins,J.C.andNeal,P.(2013)Themakingofthe QueenElizabethOlympicPark.Chichester:Wiley.

Jacks,B.(2004)‘ReimaginingWalking’,Journalof ArchitecturalEducation,57(3),pp.5–9. doi:10.1162/104648804772745193.

Jacks,B.(2007)‘WalkingandReadingin Landscape’,LandscapeJournal,26(2),pp.270–286. doi:10.3368/lj.26.2.270.

Julier,G.(2005)‘UrbanDesignscapesandthe ProductionofAestheticConsent’,UrbanStudies, 42(5–6),pp.869–887. doi:10.1080/00420980500107474.

Junker,B.andBuchecker,M.(2008)‘Aesthetic preferencesversusecologicalobjectivesinriver restorations’,LandscapeandUrbanPlanning, 85(3–4),pp.141–154.doi:10.1016/ j.landurbplan.2007.11.002.

Kaplan,R.etal.(1998)Withpeopleinmind:design andmanagementofeverydaynature.Washington, D.C.:IslandPress.

Kareiva,P.etal.(2007)‘Domesticatednature: Shapinglandscapesandecosystemsforhuman welfare’,Science,316(5833),pp.1866–1869. doi:10.1126/science.1140170.

Kondolf,G.M.andPinto,P.J.(2017)‘Thesocial connectivityofurbanrivers’,Geomorphology,277, pp.182–196.doi:10.1016/ j.geomorph.2016.09.028.

Kuhlmann,F.etal.(2021)‘Urbanriverrevitalisation’, inUrbanBlueSpaces.Routledge.

Levy,S.F.(2011)‘GroundingLandscapeUrbanism’, Scenario[Preprint],(1).Availableat:https:// scenariojournal.com/article/grounding-landscapeurbanism/(Accessed:28February2021).

Li,M.H.andEddleman,K.E.(2002)‘Biotechnical engineeringasanalternativetotraditional engineeringmethodsabiotechnicalstreambank stabilizationdesignapproach’,LandscapeandUrban Planning,60(4),pp.225–242.doi:10.1016/ S0169-2046(02)00057-9.

LondonLegacyDevelopmentCorporation(2018) ‘ParkDesignGuide2018’.Availableat:https:// www.queenelizabetholympicpark.co.uk/-/media/ lldc_park-design-guide_web.ashx?la=en(Accessed: 21November2021).

LondonLegacyDevelopmentCorporation(nd)‘A walkaroundtheQueenElizabethOlympicPark’. Availableat:https:// www.queenelizabetholympicpark.co.uk/-/media/ qeop/files/public/a-walk-around-queen-elizabetholympic-park.ashx?la=en(Accessed:21November 2021).

Macpherson,H.(2016)‘Walkingmethodsin landscaperesearch:movingbodies,spacesof disclosureandrapport’,LandscapeResearch,41(4), pp.425–432. doi:10.1080/01426397.2016.1156065.

Maller,C.etal.(2006)‘Healthynaturehealthy people:“contactwithnature”asanupstreamhealth promotioninterventionforpopulations’,Health PromotionInternational,21(1),pp.45–54. doi:10.1093/heapro/dai032.

Manning,O.D.(1997)‘Designimperativesforriver landscapes’,LandscapeResearch,22(1),pp.67–94. doi:10.1080/01426399708706501.

Marrero-Guillamón,I.(2012)‘Photographyagainst theOlympicspectacle’,VisualStudies,27(2),pp. 132–139.doi:10.1080/1472586x.2012.677497.

Marrero-Guillamón,I.(2014)‘Togetherapart: HackneyWick,theOlympicsiteandrelationalart’, arq:ArchitecturalResearchQuarterly,18(4),pp. 367–376.doi:10.1017/s1359135515000093.

McHarg,I.L.(1969)Designwithnature.GardenCity, N.Y.:publishedfortheAmericanMuseumofNatural HistorybytheNaturalHistoryPressWiley/ Doubleday.

McNevin,N.(2014)‘London2012legacy:principles, purpose,professionalsandcollaboration’, ProceedingsoftheInstitutionofCivilEngineers-Civil Engineering,167(6),pp.13–18.doi:10.1680/ cien.14.00035.

Miller,J.C.(2014a)‘Affect,consumption,andidentity ataBuenosAiresshoppingmall’,Environmentand PlanningA,46(1),pp.46–61.doi:10.1068/ a45730.

Miller,J.C.(2014b)‘Mallswithoutstores(MwS):the affectualspacesofaBuenosAiresshoppingmall’, TransactionsoftheInstituteofBritishGeographers, 39(1),pp.14–25.doi:10.1111/ j.1475-5661.2012.00553.x.

Montgomery,C.(2015)Happycity:transformingour livesthroughurbandesign.London.