02 LITERATURE REVIEW

In reading the wider oeuvre of Rem Koolhaas, several recurring principles and motifs serve to establish a foundational lens through which his approach may be understood. Whilst it is often unclear where the distinction lies between grounded architectural proposition and bold exercise in creative provocation, the driving agenda behind Rem Koolhaas can be seen, as Jeffrey Kipnis observes, as an aspiration to “discover what real, instrumental collaboration can be effected between architecture and freedom.”1 That is to say, one can view the work of Koolhaas/OMA as an attempt towards typological and spatial innovation; whereby the formal hierarchies and social narratives embedded within programmatic normativism are contested and the void as an architectural strategy is often foregrounded. Indeed, Koolhaas’ termed ‘Strategy of the Void’ has at various points, consistently provoked debate regarding the failed agency of architectural planning and the possibility of new spatial paradigms.

Nearly a century prior to Koolhaas, the early protagonists of the Modern Movement disrupted the historical succession of traditional typological reasoning - instead turning to industry and scientific innovation as a doctrine for functional solutions. In his essay ‘On Typology’ (1978), Rafael Moneo suggests that

Mies Van Der Rohe in particular conceived of architecture not as typology so much as “a physical fragment of conceptual space”2 by which he means the architecture in and of itself was only the physical materialisation of a latent force within an arbitrary field. This assertion implies a certain agency that can be attributed to space alone, and by extension; a void. Since, as Moneo remarks, “space takes precedent over type”3, a void space in effect can become a generator which catalyses the performative function of a building or urban area despite a lack of formal composition.

Whilst the concept of compositional absence is arguably a vague proposition, Koolhaas’ so-called Strategy of the Void and Mies’ spatial abstraction can both be seen as a commentary on architecture’s ability to operate as an autonomous entity. If the function of architecture is considered relative to its external context, the performative value of the void itself similarly must work in tandem with a material counterpart, to the extent that its value is largely relativistic. In this respect, the following literature study will speculate on the void as a pretext for autonomous, innovative architectural contingencies; and accordingly attempts to ascertain how it engages with Postmodern understanding of urban spatial organisation.

1 Kipnis, ‘Recent Koolhaas’. Pg. 26 - 37

2 Moneo, ‘On Typology’. Pg. 32

3 Ibid. Pg. 32

FIGURE-GROUND AND URBAN POCHÉ

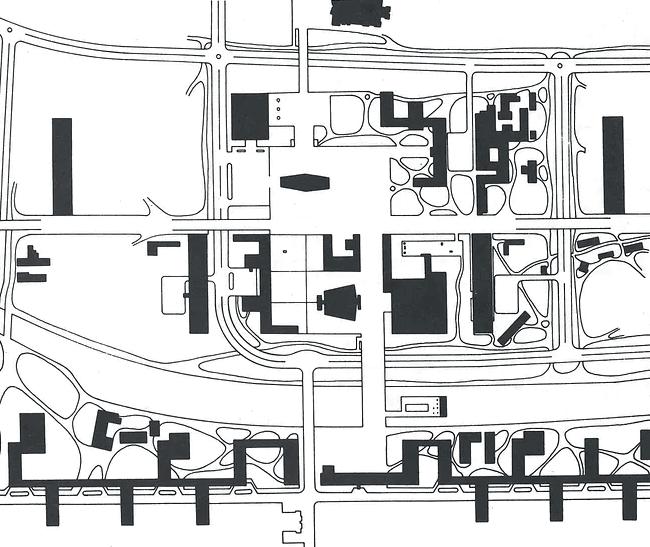

Presiding above all exploration of the void strategy conducted in this thesis is the theory of Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter in Collage City (1978). In Chapter 3 titled ‘Crisis of the Object: Predicament of Texture’, Several diptychs are depicted and examined through the lens of figure-ground.4 Most notably in a direct comparison between Le Corbusier’s Modernist plan for SaintDié and the traditional city layout of Parma (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), the authors argue that both models, when read in this way, reveal conflicting spatial orders; Rowe and Koetter observe one city as “an accumulation of solids in largely unmanipulated void: and [the] other an accumulation of voids in a largely unmanipulated solid”, thus causing opposing interpretation of figure, “[…] in the one object, in the other space.”5

Jacques Lucan, expounding on the formal polarity between the termed convex and concave nature of each model, writes, “Concave space was perceived from a central point of view with buildings disposed in something like a circle. In the old city, empty spaces were therefore kept closed. […] In modern urban planning, empty spaces were open.”6 This distinction becomes

important when considering the function of the perceived void in each respective system. The Modernist city is described as convex, as its immense void is seen to dissolve the legibility of the plan’s figure by segregating its anonymised slabs and towers. In Rowe and Koetter’s analysis of the traditional city however, concave spaces such as courtyards and plazas are spaces which are socially charged.

The central point of the text’s stance then emerges from this viewpoint – an understanding by the authors that “buildings and spaces exist in an equality of sustained debate.”7 What is meant by this is that the various binary positions Rowe and Koetter initially raise (object versus texture, figure versus ground, and so on) can in fact constitute parts within a continuous matrix (what the authors promote as bricolage), and in doing so, the void space can become an active, dominant element rather than subordinate to an adjacent solid figure. Whilst the argument posited by Rowe and Koetter was predicated on a broader pluralistic aspiration for recognising the city as a sum of heterogenous parts, the concept of ‘Urban poché’ is also of particular relevance to the study of the

void. In Beaux-Art tradition, poché itself describes the darkened segment of a plan or section which represents portions of a built structure. Bernhard Hoesli likens poché to “the mortar joints between the individual stones and blocks of a rubble-wall.”8

What therefore emerges here is the idea of multiplicity in the void’s imposition, as one may interpret poché as the transitional element which organises separate spaces. Like the juxtaposition between object and space, poché engages in a dialectic relationship with the transparency of an urban field – both leveraging the void across an urban field, and both informing the performance of the whole. Collage city accordingly adopts Urban poché as an interstitial means for understanding the dichotomy between the city’s contingent parts. That is to say, poché becomes a sort of method for framing – or indeed mediating - the dialectic relationship between figure and ground. The authors further reason that such a method can allow for alternative gestalt readings in particular situations; and in certain cases, it is possible (if not appropriate) for the use of poché to invert the performative interpretation of a building

or space depending on its contextual configuration. Auguste Perret’s proposal for the Palace of the Soviets in Moscow is cited as one such example, inasmuch as the building is normatively understood in Modernist functional terms yet recedes into becoming passive texture in order to activate adjacent voids and engage with its context. Here, Rowe subverts the initial premise of the dissonance between the concavity of the traditional city and the convexity of the Modernist city, acknowledging the implied reciprocity between said object and texture as a matter of “context” and “perceptual field”9. Though one may regard the total abstraction of a complex urban fabric into binary figure-ground as too reductionist, the bilateral metamorphosis which Rowe describes here is therefore deeply embedded in the interpretation of poché - engaging the void as a device for performative and spatial potential.

4 The reading of figure-ground representation has its roots in gestalt psychoanalysis, wherein a particular stimulus is arranged into meaningful and legible structures in order to form a hierarchy of information.

5 Rowe and Koetter, Collage City. Pg 62

6 Lucan, Composition, Non-Composition. Pg. 383

7 Rowe and Koetter, Collage City. Pg. 83

8 Petit and Maxwell, Reckoning with Colin Rowe. Pg. 136

9 Rowe and Koetter, Collage City. Pg. 79

Figure 1: City Plan for Parma

Figure 2: Le Corbusier’s city plan for Saint-Dié.

The discussion on architectural autonomy, which seeks to evaluate the nature of architecture’s internal disciplinary methodology, has long been identified as an issue which considers the intersection of architecture’s own material domain with other fields of knowledge. In the introduction to the book ‘Practice: Architecture Technique + Representation’, Stan Allen postulates on architecture’s innate capacity to operate outside of a discursive system. Though it inherently carries an inclination towards representational application, Allen advocates for a more dynamic methodology for architectural practice on the basis that it is ‘insistently affirmative and instrumental.’10 In opposition to what he calls ‘built discourse’11 Allen emphasises the tangible, process-oriented aspects of the built environment in forging “performative multiplicities”12, which he believes “project transformations into the future”13 - as opposed to rhetorical disposition which stifles any propelling potential. The crux of Allen’s argument lies in the agency supposedly held by architectural practice, as well as the parameters which he believes govern its ability to operate autonomously in the public sphere. This examination has obvious implications on the void

as a spatial mechanism (and its subsequent deployment in any given architectural field). Much like Allen’s critique of ‘built discourse’ - which relies on “a theoretical unity conferred from without by ideology or discourse”14 - the void as a strategic device can be seen to equally depend on contiguous elements (a solid) to derive utility. Although for the void such elements mostly exist within the realm of architecture itself, rather than external metaphysical constructs which operate entirely outside of architecture, it too can be susceptible to becoming a diagrammatic, passive gesture through absence rather than catalysing the performance of its surroundings.

This position also adds credence to Rowe and Koetter’s endorsement of bricolage. As mentioned above, the concept of bricolage is introduced in Collage City with a political agenda; as a means of characterising “an unsystematic tinkering that avoids totalizing concepts.”15 Again, the question of agency is patent – since the bricolage technique suggests a rejection of the absolute principles of both Modernist Utopia and traditional conformity, a void space (as in Perret’s Palace of the Soviets)

and critique on society, especially compared to other forms of media. See Allen, Practice. Pg. XIV

12 Allen, Practice. Pg. XV

13 Ibid. Pg. XIII

14 Ibid. Pg. XV

15 Böck, Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas. Pg, 135

relies on a juxtaposition with a surrounding figure which informs a broader pattern of use. This strategy is parallel - or at the very least resonant - with what Allen describes as an ‘ensemble of procedures’16, insofar as both theories grapple with the conflict between broader imposed narratives and material procedure.17 In this way, the void as a strategy is to a large extent solely dependent on its context to deliver operative outcomes, specifically the way in which synergies and spatial patterns - be it at an urban or building scale - collide through its imposition. Like Collage City’s ensuing proposition of contextual collaging, the relationship of figure and ground can thus be seen, according to Rowe and Koetter, as “one in which both buildings and spaces exist in an equality of sustained debate.”18 Referring to Louis Althusser’s concept of ‘Semi-Autonomy’, architectural historian K. Michael Hays situates contemporary architecture somewhere in between absolute autonomy and purely rhetorical disposition, suggesting that it functions within a reciprocal relationship with other ideological fields (economic, political, cultural, and so on) whereby a body of knowledge is acquired largely through a mutual system that is “held together by the structural totality

of a social formation.”19 Ultimately, the agency of the void as a strategy can only therefore be understood in similar terms - as Hays aptly describes: ‘a relational concept’ - such that, through its ‘semi-autonomy’, it addresses both its own codified procedure as well as external realities.

16 Allen, Practice. Pg. XV

17 Both Allen and Rowe/Koetter address the issue of agency in somewhat mutual terms. Allen’s idea of ‘material practice’ hinges on the internal disciplinary logic of Architecture whilst Bricolage is framed as a method of leveraging context through assemblage of diverse elements. Both theories view Architecture’s agency as immanent, rather than being prescribed externally.

18 Rowe and Koetter, Collage City. Pg. 83

19 Hays, ‘Prolegomenon for a Study Linking the Advanced Architecture of the Present to That of the 1970s through Ideologies of Media, the Experience of Cities in Transition, and the Ongoing Effects of Reification’. Pg. 102

CASE STUDY 01:

CASA DA MÚSICA, PORTO

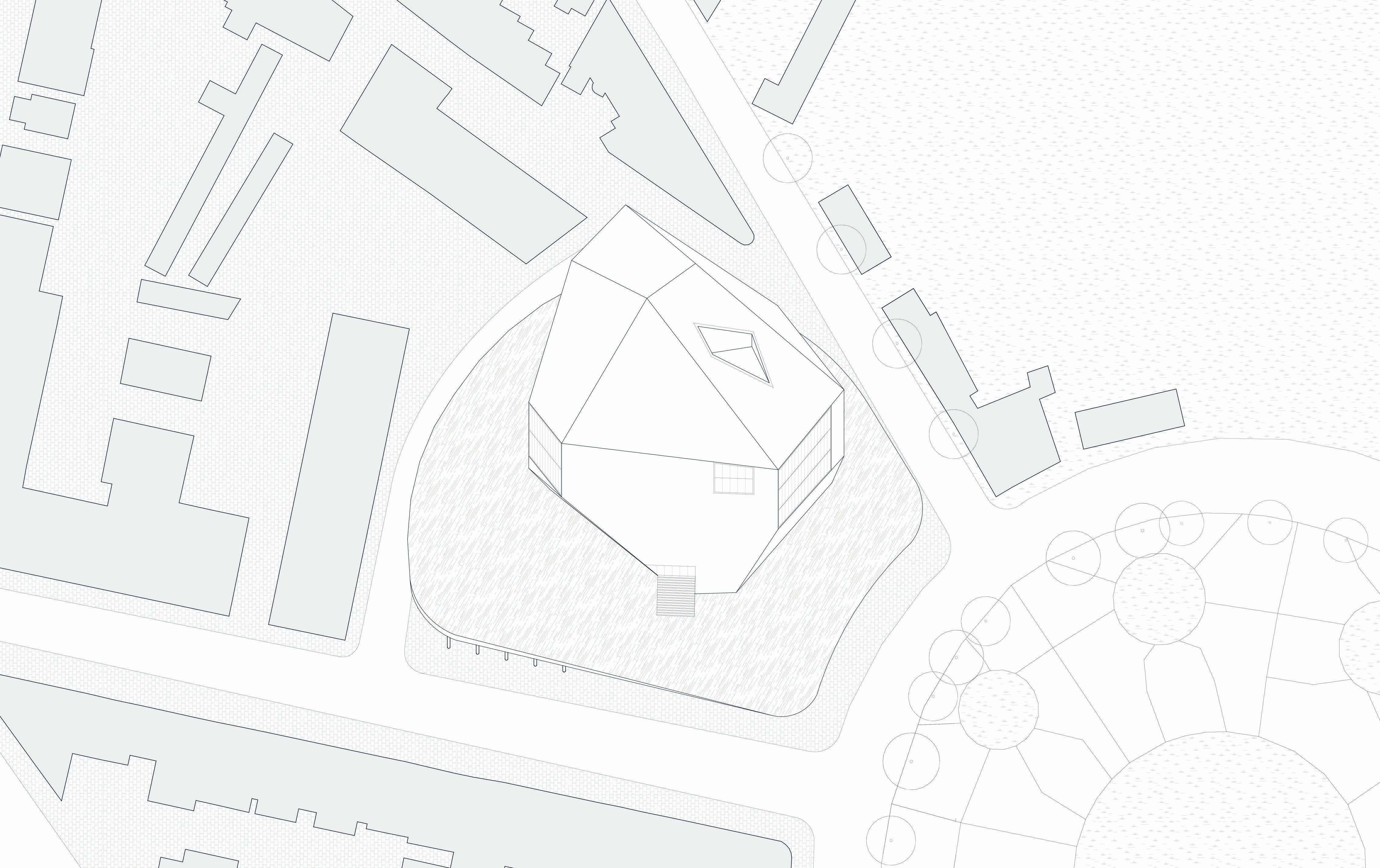

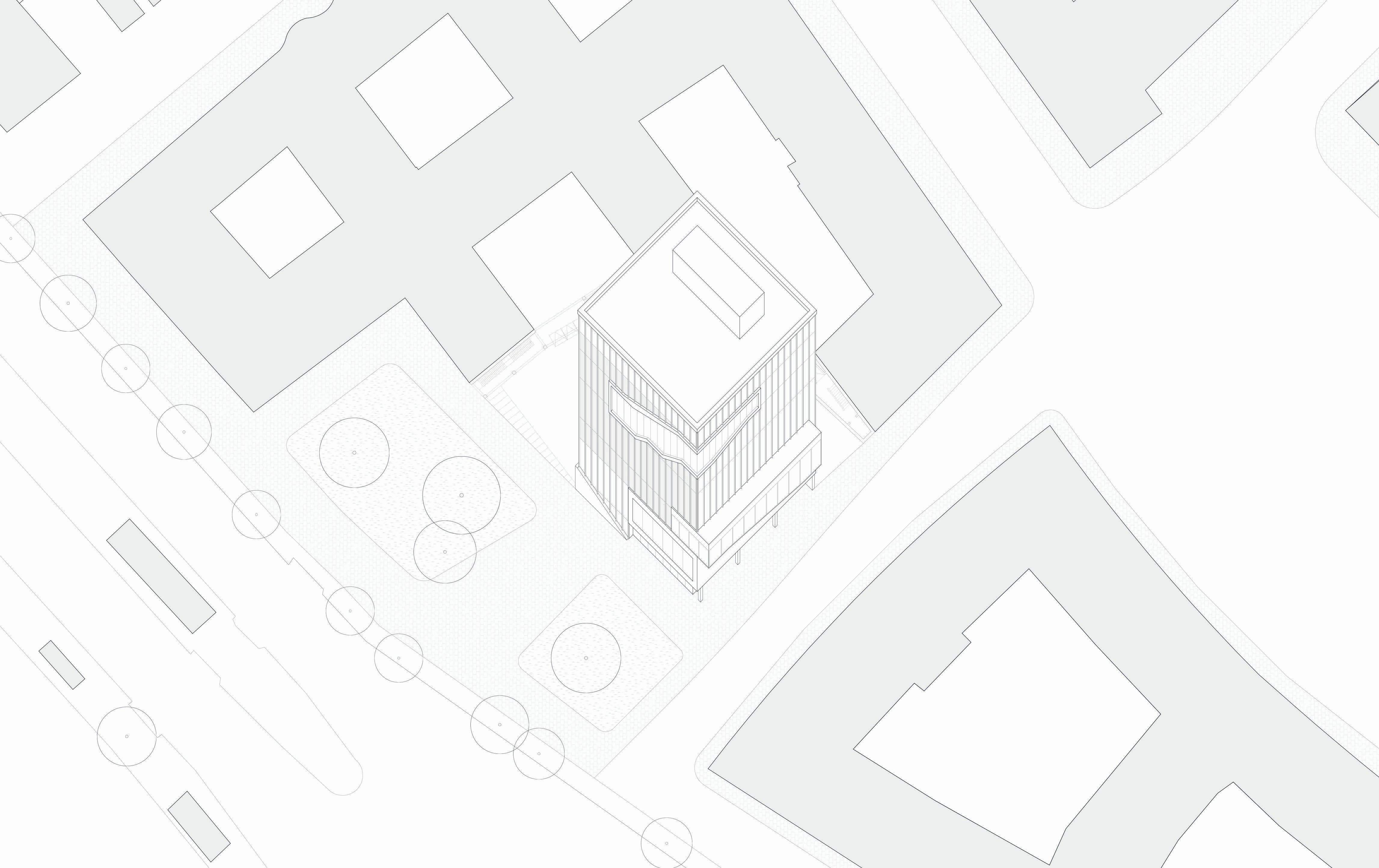

Figure 3: Axonometric drawing of OMA’s Casa da Música, Scale 1:500.

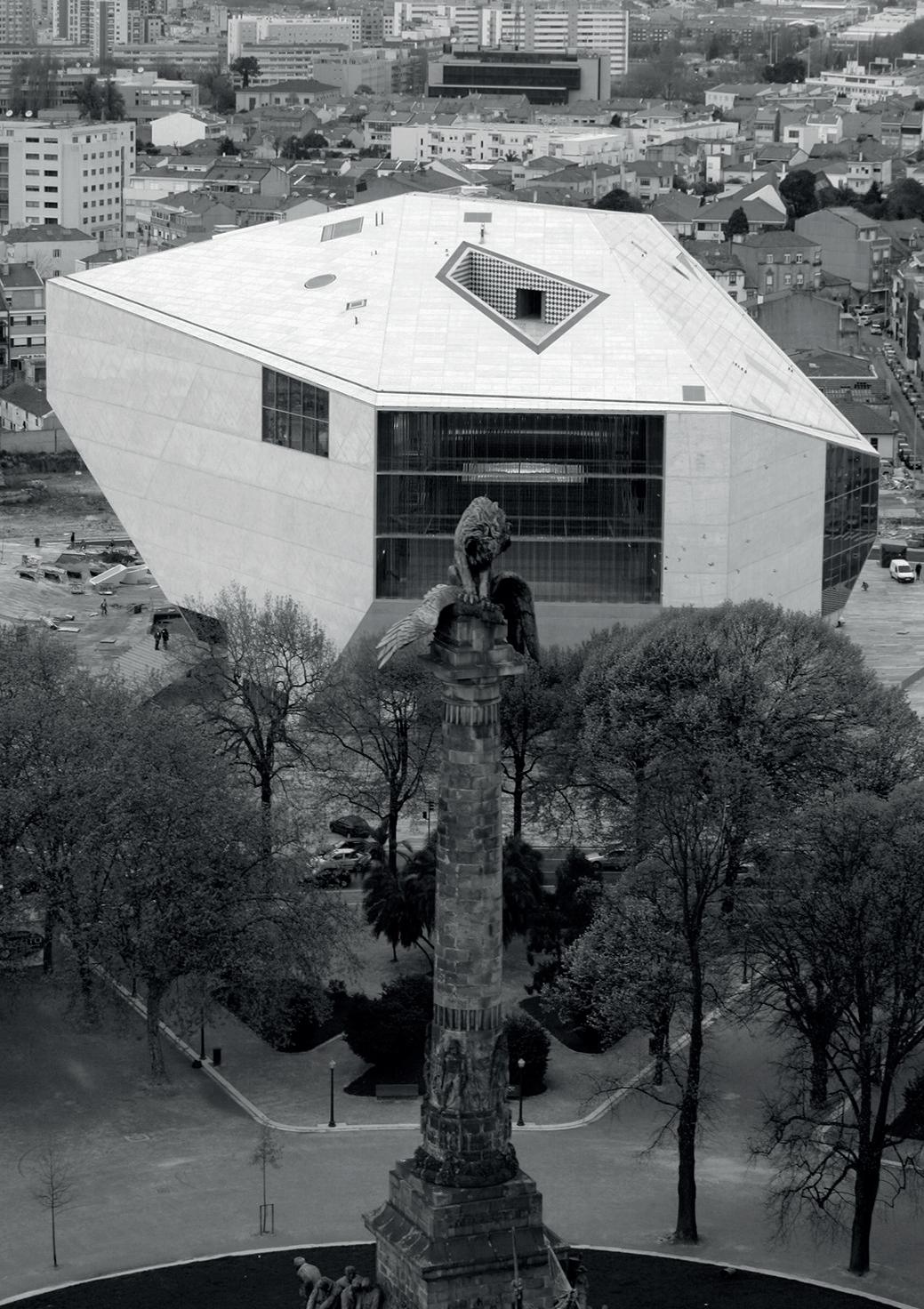

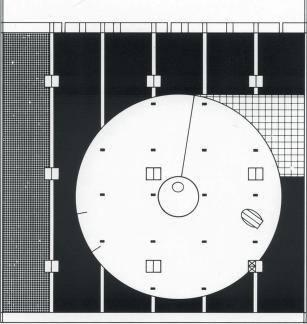

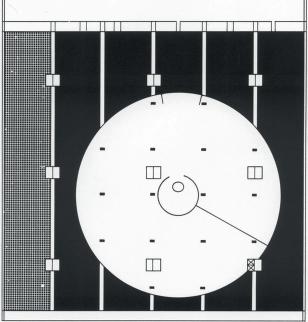

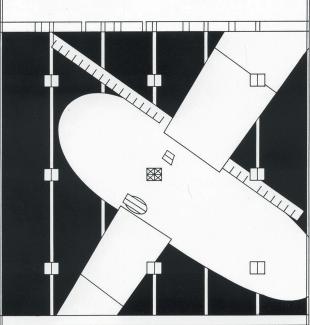

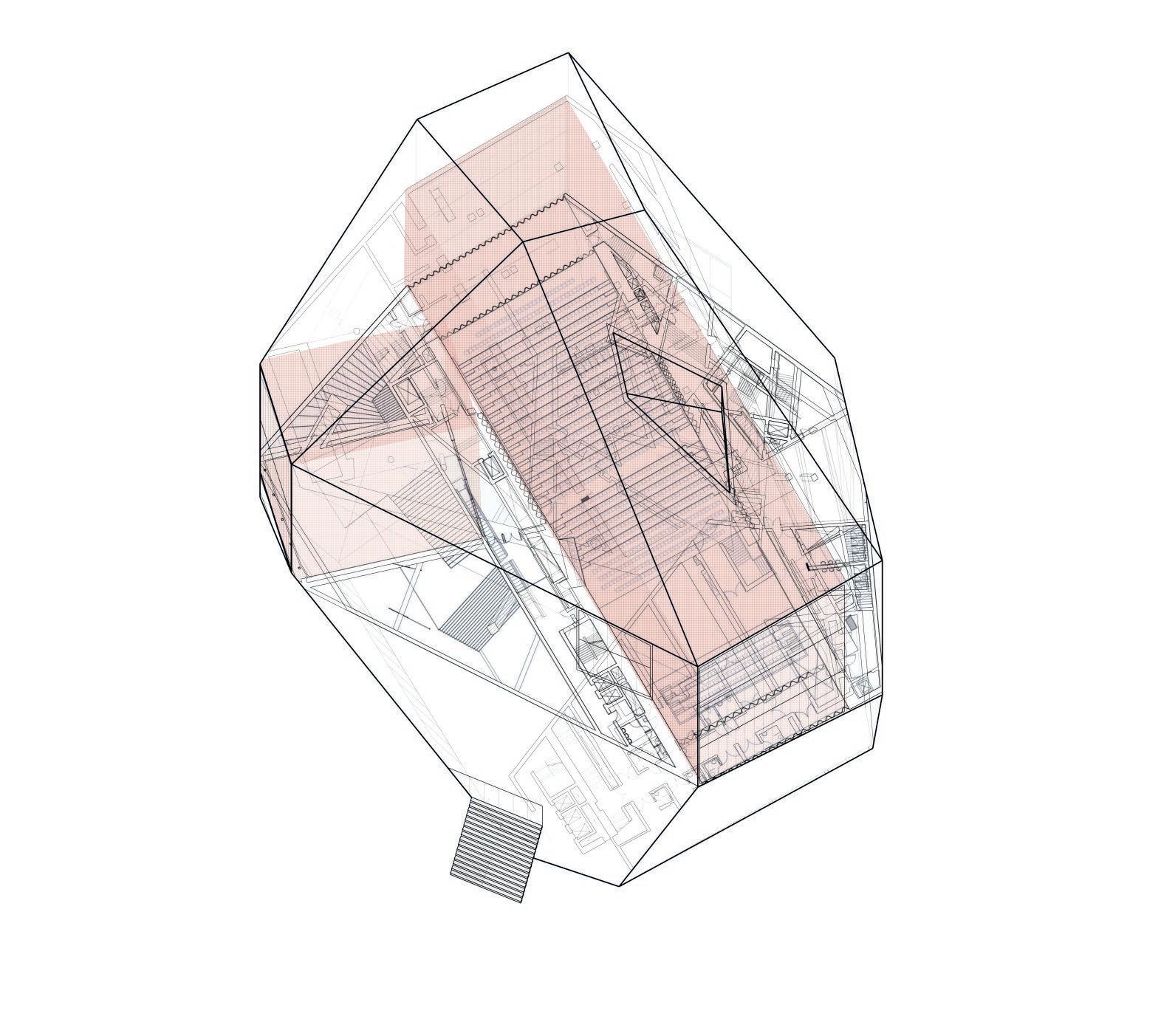

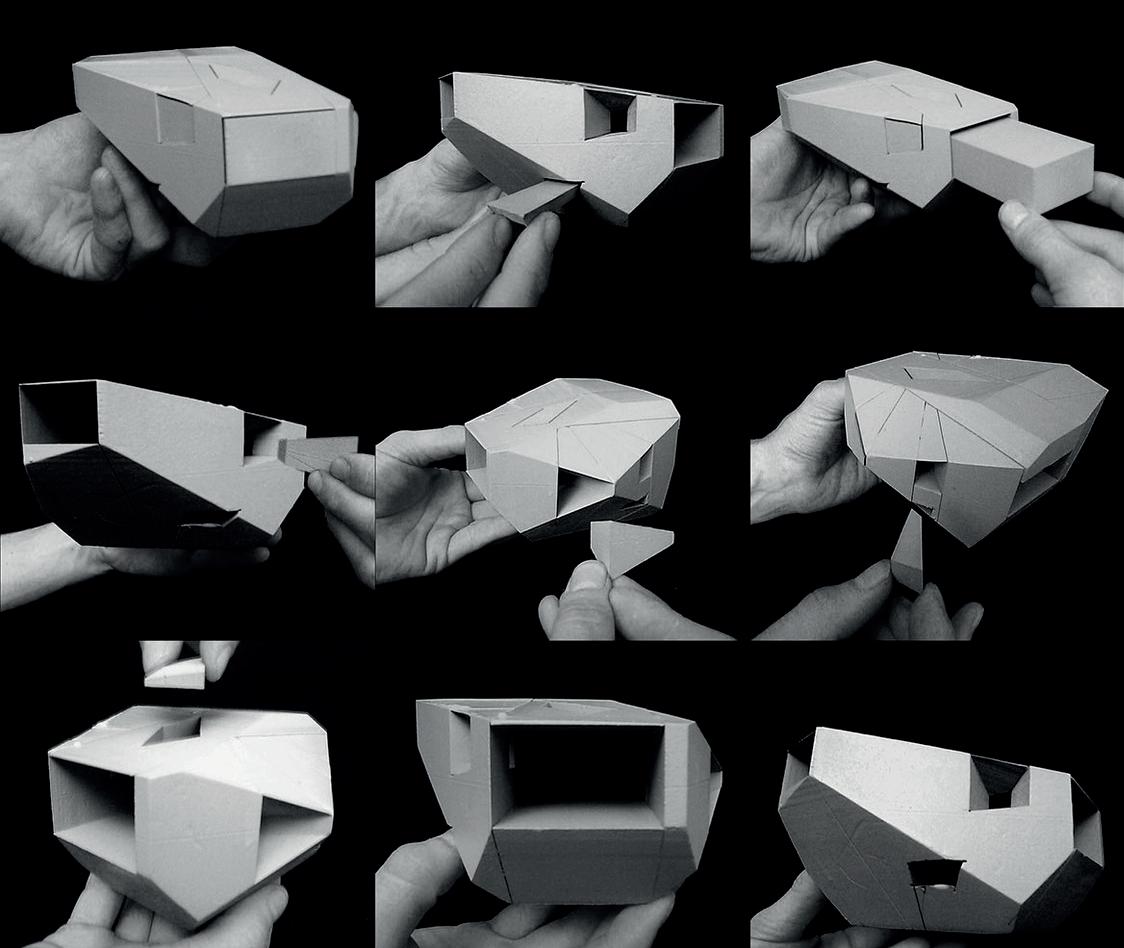

The case study exploration of this thesis research begins with an investigation into Rem Koolhaas’ scheme for the Casa da Música in Porto (1999 – 2005), where perhaps the application of the void is most easily discerned. Touted as the new home of the National Orchestra of Porto upon its completion, the theatre asserts its presence in a historic Rotunda of a working-class peripheral neighbourhood through its striking crystalline form. Adopted explicitly from OMA’s previous design for the Y2K house in Rotterdam,20 the principal void strategy of Casa da Música is identified as the building’s prominent auditorium space, where a large tunnel serves both as iconographic diagram as well as spatial organiser. For Koolhaas, the use of such absences represents a novel method of ordering space as well as engaging with an urban landscape, arguably forming part of OMA’s canonical array of architectural concepts; the elevator, the wall, the ramp, to name a few.

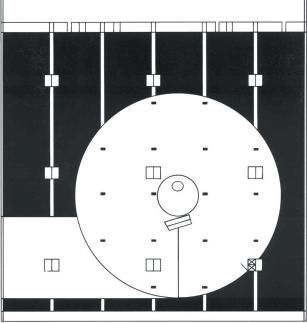

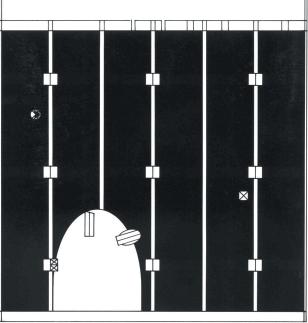

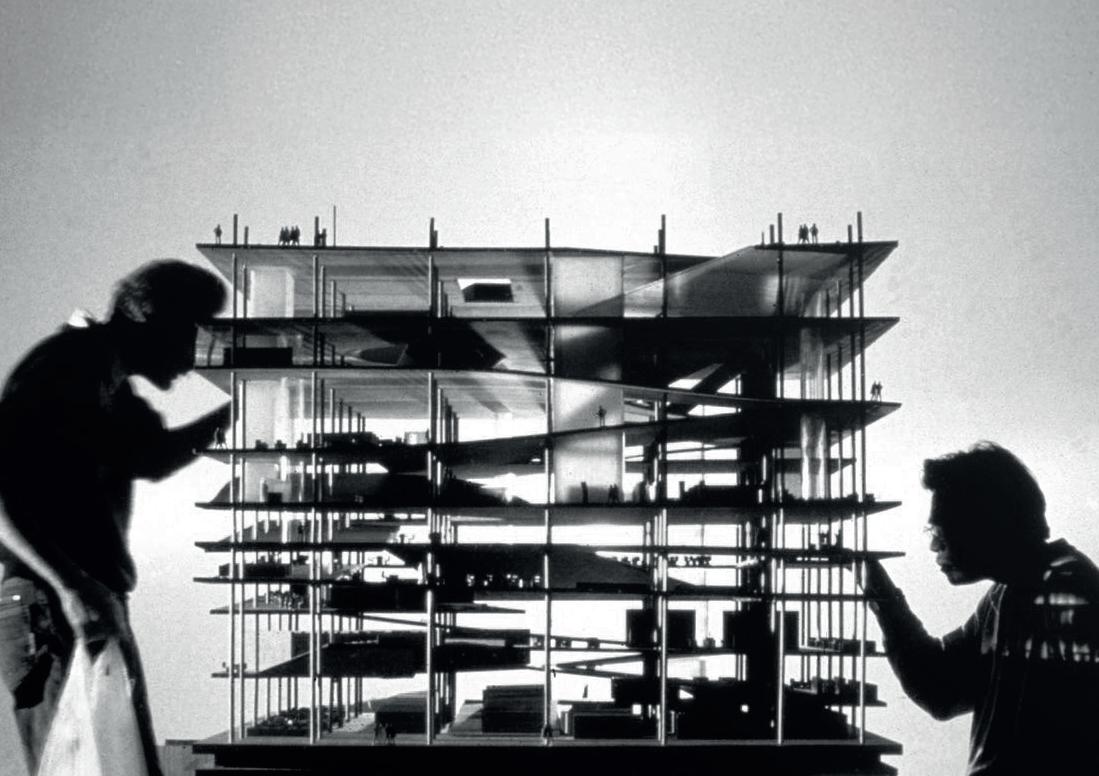

Koolhaas’ experimentation with the solid-void relationship can be traced directly to the design for Très Grande Bibliothèque (TGB, 1989), which similarly implements methods of eliminating

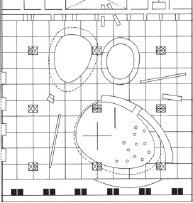

spaces from a volume. Patented as a ‘Method for defining a building through manipulating absences of building’21 the design for the library (Fig. 5) is imagined as ‘a solid block of information’ (the darkened segments of the poché drawings) from which its ‘reading rooms’ (the white, irregular forms) are systematically carved out from to form a stratified, multi-storey cube sustained by nine circulatory cores.22 Conceptually, the scheme clearly shows its intention. Notwithstanding its ambiguity in communicating program and a somewhat haphazard articulation of spatial relationships, the void strategy here is primarily framed as an exercise in speculative freedom via juxtaposition, in which the hollowed-out spaces themselves act as an armature that takes on a generative role. This approach relates to Koolhaas’ long-standing interrogation of the very agency of architecture. Whilst it doesn’t recall the ‘deliberate surrender’23 to chaos of his other termed Strategy of the Void project for Melun Senart (1987) - owing in large part to the difference in scale – the excavated voids here are, like the linear bands of Melun Senart, perceived as figure rather than passive texture despite their lack of compositional strategy. As Koolhaas Writes, “Forms only have to

20 Gargiani, Rem Koolhaas - OMA. Pg. 272

21 Koolhaas, Content. Pg. 77

22 Koolhaas, ‘Strategy of the Void’. Pg. 604 - 660

23 Koolhaas, ‘Surrender’. Pg. 974

Figure 4: Casa da Música, aerial view from rotunda imperial monument.

be “left out,” not constructed.”24 Although the drawings for both the TGB and Melun Senart appear as visually analogous to the dichotomy of figure and ground presented by Rowe and Koetter; Koolhaas, unsurprisingly, had not subscribed to the contextualist viewpoint offered in Collage City.

In his approach, the void is predisposed less so with a ‘reconciliation’25 of any two opposing elements, but rather an overt expression of itself to establish a new spatial logic via non-compositional means. Furthermore, the device of poché was too being appropriated by Koolhaas. Whereas the BeauxArt tradition of poché (say, in Louis Kahn’s system of served and servant spaces) establishes a tectonic and compositional congruence between different spaces; in the TGB, their relationship is severed to produce, as the project description states, “liberated and randomized relationships between the different components of a building.”26 Naturally, one would recall Koolhaas’ previous concept of the ‘Lobotomy’27 from Delirious New York (1978), whereby a similar denial of any mediation between building and city occurs at an urban scale, in contrast

to the contextualist assertion of poché by Rowe and Koetter. Thus, the use of the void in the TGB can be interpreted as a form of internal ‘lobotomy’.

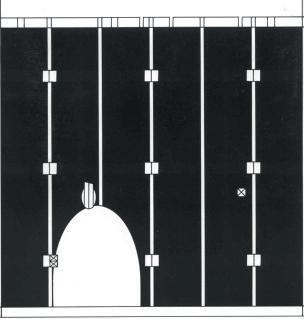

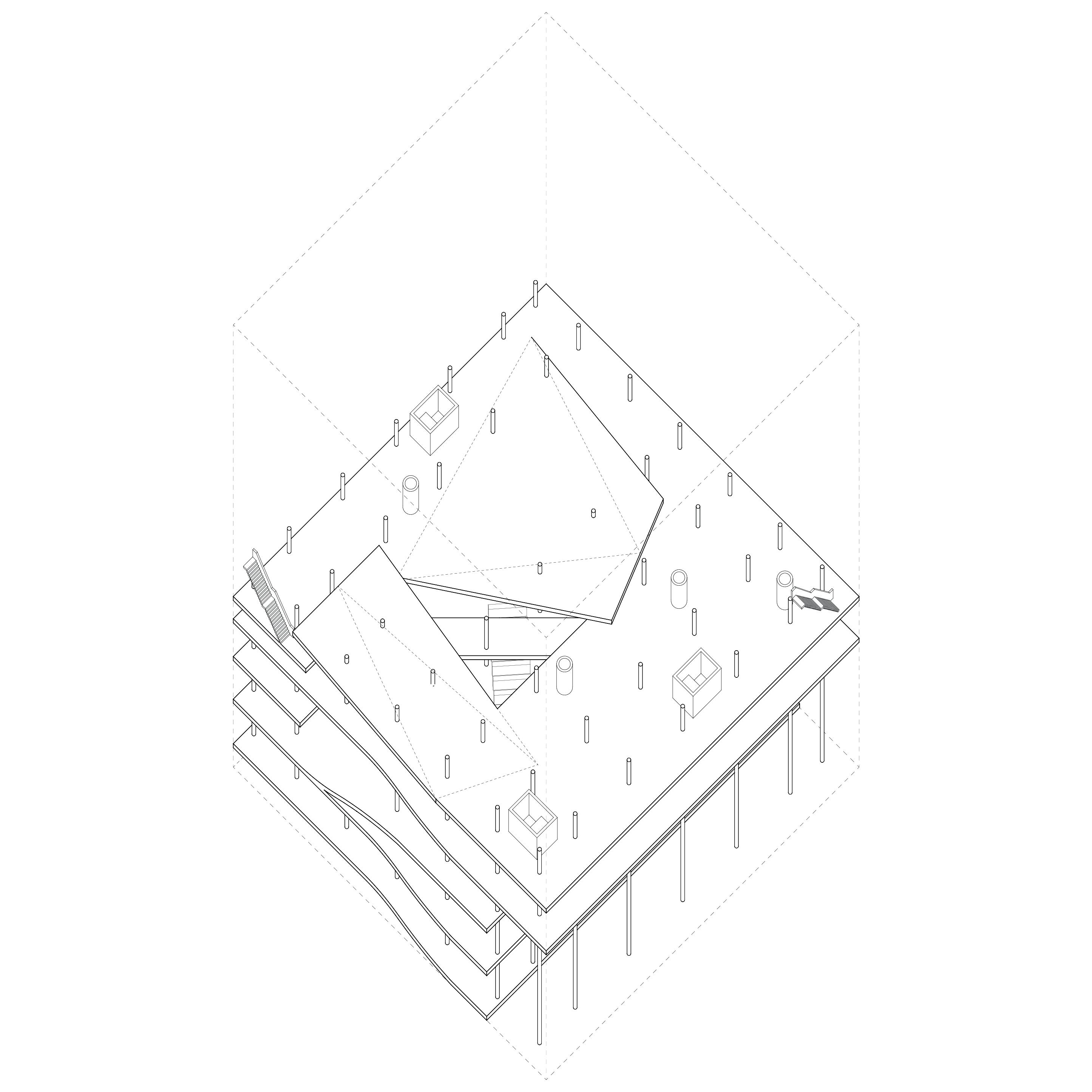

In the Casa da Música, the strategy of the void adopts a somewhat similar spatial and sequential logic. In a ‘Magrittian leap in scale’ from the Y2K house design28 the scheme however does not systematically carve out a series of voids at various levels, but rather a single prominent ‘shoe-box’ shaped void around which an ensemble of other public spaces are organised. In viewing the planimetric arrangement of the project’s collective and ancillary spaces, the collective spaces (e.g. auditoriums, foyers) are the foremost element excavated from the volume, which thus determines the formal disposition of the building. In other words, the void spaces serve both as spatial and compositional driver, whereby the traditional use of poché (i.e. to denote masonry elements) instead represents an entire solid which itself becomes the ‘texture’, as such, of the building. Compositionally, there is also an interesting parallel to be drawn – as Pavlos Philippou points out - with Collage City’s comparison of Le

24 Koolhaas, ‘Strategy of the Void’. Pg. 632

25 Rowe and Koetter, Collage City. Pg. 72

26 Gerrewey and Patteeuw, OMA - the first decade. Pg. 131

27 Koolhaas, Delirious New York. Pg. 100

28 Gargiani, Rem Koolhaas - OMA. Pg. 277

Figure 5: Project for the Très Grande Bibliothèque, Plans of different levels.

Pautre’s Hotel de Beauvais and Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye. As in their assessment of the Modernist and traditional city, the authors position two opposing characteristics; the former in which its internal voids take on a ‘directive role’, and the latter as an insular and rational solid.29 A similarity inevitably arises between the open courtyards of Le Pautre’s Hotel and the elevated main hall of Casa da Música - both as “unstable perimeter with stable interior”30 - although in Koolhaas’ design one can observe that its autonomous, monolithic presence isn’t commensurate with any sort of continuous urban matrix recognised in the traditional city. Counter to the Beaux-Art idea of unity in composition and spatial perception, the exterior appearance is instead generated from the building’s internal logic.31

In this context, the void can in a sense be seen to hold intrinsic agency. It can be argued that unlike the contextualist model of assemblage, the void here asserts itself, in both a physical and diagrammatic sense, to become a formative element. Whilst it is understood that any void (like those of the traditional city) would require an equal figure to derive value, Koolhaas’ process of excavation thus relegates, or even does not acknowledge,

any external systems – to the extent that the polyhedral form of the building in many ways has a direct visual similitude with the solid/void diagram of functions generated by such as strategy.32

This is evident in Lucan’s interpretation, “Solids and voids [of Casa da Música] produce a texture foiling any compositional readability.”33

Urbanistically, one would again naturally recall Rowe and Koetter’s assessment of the free-standing Modernist object. Internally, the theatre’s central auditorium emerges as a celebrated self-contained void which places the form of the building in isolation, orientated as to offer a linear view of the imperial monument at the centre of the rotunda. But whilst Philippou vindicates its institutional performance by recognising the city as a scenic backdrop for internal performances,34 it can also be reasoned that such a proposition would fail to generate a reciprocal, dynamic relationship with a context. Instead, the static nature of the void establishes a purely scenographic relationship with the city in which, through its visual framing, the urban context becomes subordinate to the autonomy of the building.

29 Rowe and Koetter, Collage City. Pg. 78

30 Philippou, ‘Cultural Buildings and Urban Areas’. Pg. 1280

31 According To architectural theory, the Beaux-Art system heavily emphasised that for a room to be perceived as such, it must show what it is made of. Koolhaas’ Casa da Música undermines this by making it impossible to infer any unifying structural logic from what is experienced. See Lucan, Composition, Non-Composition. Pg. 490

32 Peter Eisenman observes the trend in Koolhaas’ work of a turn to treating diagram as icon rather than symbol, evident in his work at Porto and later, the Seattle Public Library. See Eisenman, Ten Canonical Buildings. Pg. 208

33 Lucan, Composition, Non-Composition. Pg. 559

34 Philippou, ‘Cultural Buildings and Urban Areas’. Pg. 1279

Figure 6: Axonometric drawing for Casa da Música, Showing formal composition and internal voids.

Figure 7: Casa da Música, series of architectural models showing excavation.

Figure 8: Casa da Música, view from inside of performance hall of towards imperial monument.

CASE STUDY 02:

THE DUTCH EMBASSY, BERLIN

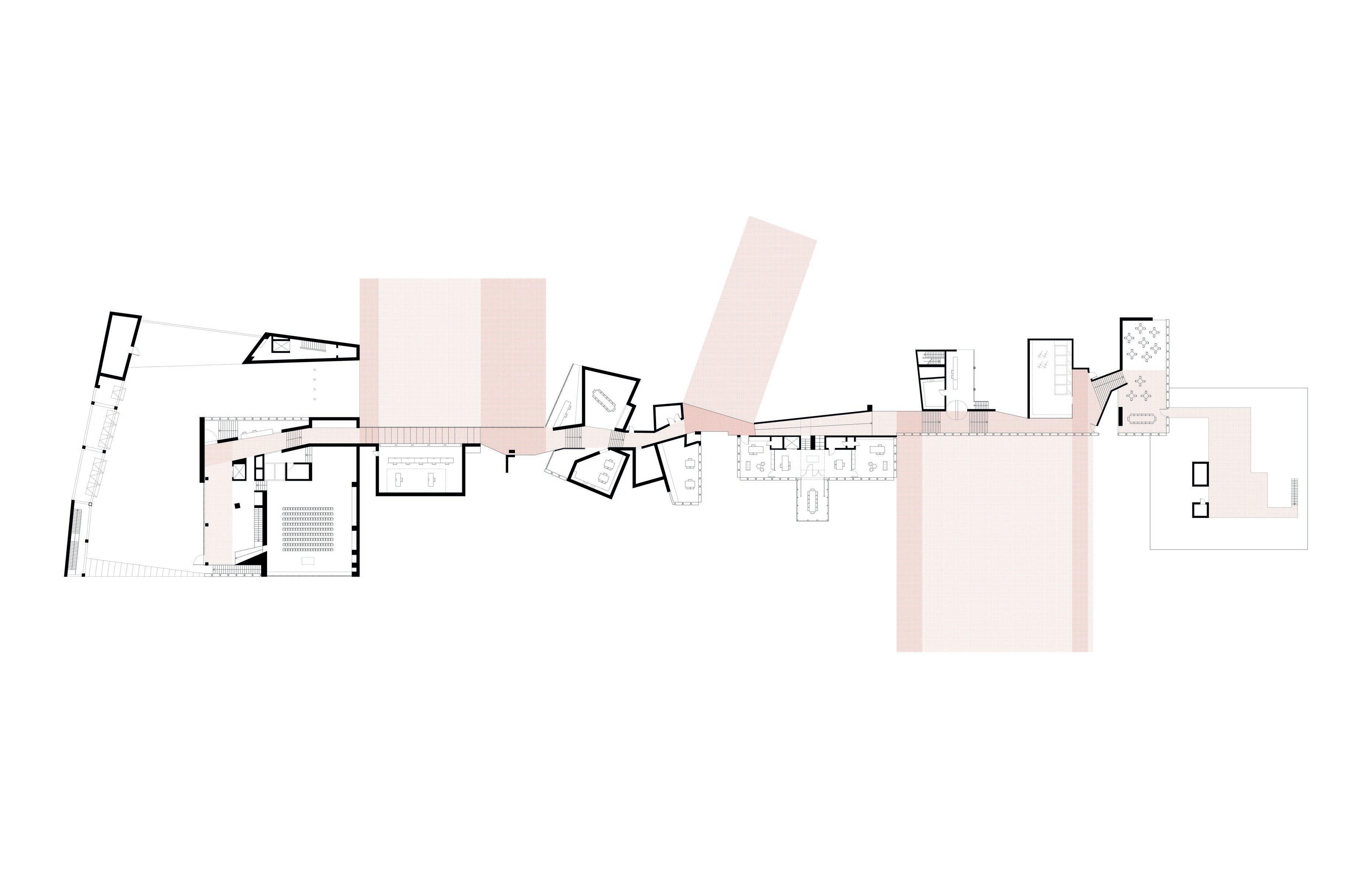

Figure 9: Axonometric drawing of

Dutch Embassy, Scale 1:500

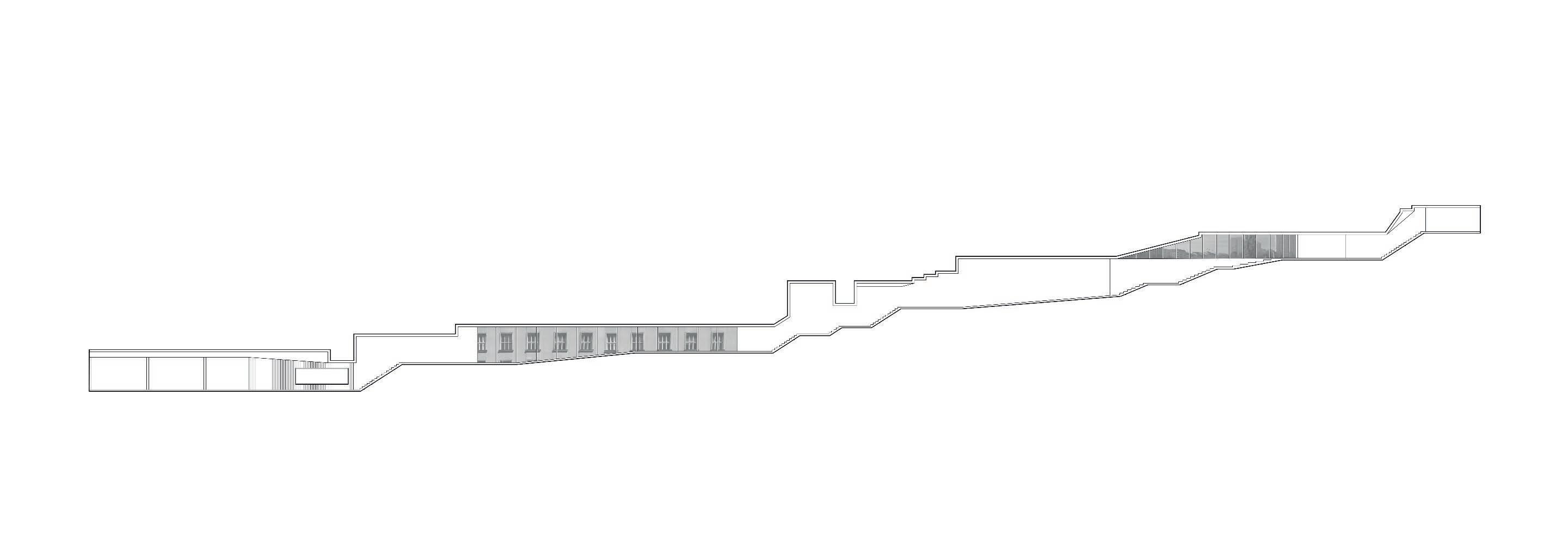

Rem Koolhaas’ design for the Dutch Embassy in Berlin in many ways represents a more dynamic application of the void as a strategy, reconceptualising its spatial articulation to capture the performative energies of both the building’s internal logic and surrounding city fabric. Built between 1999 and 2003, the Embassy at the time reflected a renewed sense of European unity in the German capital. Located on a corner site of a traditional Berlin block along the river Spree, Koolhaas’ design engages with the city as a way of ‘understanding Berlin better’35 – manifest in the building’s occupation of the city block as well as its relationship with various urban spaces and landmarks representative of Berlin’s fragmented past. For Koolhaas, this embodies the very spirit of Berlin; what he surmises as “the breathtaking sequence of its successive incarnations […]”35 throughout time: emerging metropolis, fascist stronghold, ravaged city, to name a few. But whilst this does evoke his complicated relationship with identity and historical continuity (which need not concern the subject of this research), it is against this setting which the void strategy in the Dutch Embassy is realised.

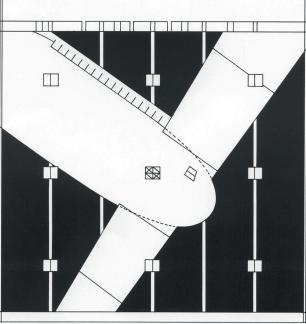

Immediately, the scheme’s deployment of a sort of void strategy is discerned in the block’s morphological pattern. Koolhaas’ design is a direct result of the city’s ‘Planwerk Innere Stadt’ regulations, which had sought to reestablish a coherent and unified urban vision for the city following the destruction caused by Allied bombing in WWII.36 Arguably the most significant legacy of the policy was the implementation of the perimeter block structure, exemplified in many of Berlin’s quintessential early twentieth century buildings (Fig. 11) which intended to reinstate traditional street patterns. This presented a major obstacle for Koolhaas as the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs had stated that the proposal should be “a solitary building, integrating requirements of conventional civil service security with Dutch openness.”37 To satisfy the stipulation for an enclosed block, Koolhaas splits the site into two distinct volumes that sit partially on a pedestal: a free-standing cube for housing Embassy services, and a slender mass which abuts the block’s existing buildings for staff/visitor accommodation. The resultant ‘L’ shaped inner courtyard is how, by considering to the theory of Rowe and Koetter, we can begin to assess how the scheme’s void strategy interacts with

Figure 10: Dutch Embassy, view from inner harbour from across the river Spree.

35 Chaslin, The Dutch Embassy in Berlin by OMA/Rem Koolhaas. Pg. 28

36 Koolhaas, ‘The Terrifying Beauty of the Twentieth Century’. Pg. 207

37 Koolhaas, El Croquis. 53+79. Pg. 414

the context. What becomes apparent here is a twofold reading of the building, both as monolithic object and segment of the typical urban block. Whilst the conventional arrangement of the traditional city described by Rowe and Lucan has its voids completely enclosed by its architecture, the Dutch Embassy’s courtyard is permeable on the eastern side via its ramped connection to Klosterstraße resulting in a relationship to the context that varies from that of a typical institutional building in Berlin.38 Alluding to the idea of bricolage, the Dutch Embassy can be hence interpreted as a ‘reconciliation’39 – as Rowe and Koetter put it – of a Modernist object that emanates an autonomous identity whilst remaining tethered to the traditional typology of the city.

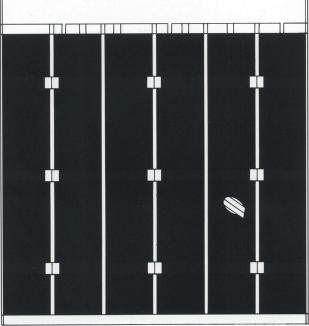

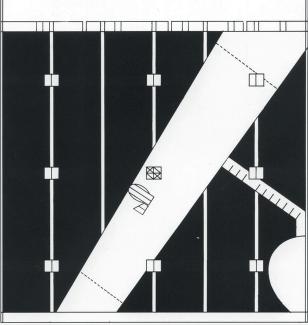

A second, and undeniably more celebrated, void aspect of the Dutch Embassy is the internal trajectory drilled through the building’s eight stories that strategically frames views of the city. To understand its manifestation, it is perhaps appropriate to briefly explore another of Koolhaas’ earlier uses of the strategy, The Jussieu Libraries (1992). Not unlike the Très Grande

38 Though not physically traversable due to change in level, the southern opening of the courtyard also separates itself from the adjacent site, remaining open to allow for visual connections to the embassy gardens and river.

Bibliothèque, the design of Jussieu adopts a radical model for engaging with the void, constructing an uninterrupted trajectory spanning its ten levels. This diagram is achieved through an iterative manipulation of the building’s floor slabs, essentially folding segments of each floor up one storey as to touch the floor of the above level, thus providing a continuous ramped ascension. Koolhaas, over a decade prior, had asserted the idea of the vertical discontinuity in the Manhattan skyscraper; understanding that the ‘Schism’40 enabled by the invention of the elevator allows for incongruent programmatic planes to be distributed vertically ad infinitum In Jussieu, Koolhaas recalls the diagram of the ideal metropolitan condition but produces an entirely different spatial organisation, insofar as the building is conceived in section and so embeds itself within the city context to become “the latest segment of the paths through Paris.”41 Through its sheer scale, the sectional void that winds through the building even evokes the Baudelarian concept of the flâneur – whereby the user is immersed in an urban-like environment, wandering a vertical boulevard and “being seduced by a world of books and information.”42

Koolhaas’ ambition to conceive the ground datum as a pliable element also has its roots in the Corbusian idea of the Free Plan - more specifically in what Jeffrey Kipnis calls Koolhaas’ ‘free section’43 Kipnis draws the comparison between Jussieu’s concourse and the Dom-Ino diagram on the basis that it utilises a conventional structural grid to stage undetermined spatial events within a neutral free plan. The dematerialisation of the ground datum however is the major departure point from the Dom-Ino structure, whereby the introduction of modulated voids in section introduces a stratification of multiple fields of interaction, in contrast to the repetition of identical floor plates in the Dom-Ino structure. Alluding to another of Le Corbusier’s concepts, Jussieu takes clear precedent from the architectural promenade in the Villa Savoye, adopting the curving typology that emerges from this sectional modulation as a means of constructing a dynamic unfolding of space. According to Koolhaas, the circulatory field of the library creates a ‘social magic carpet’44 that - upon inspection - seems to disrupt the traditional figure-ground model. Given that the void spaces bound by the undulating floor plates are the dominant formal principle,

40 Koolhaas, Delirious New York. Pg. 105

41 Gargiani, Rem Koolhaas - OMA. Pg. 191

42 The term flâneur, referring to Charles Baudelaire’s archetype of the leisurely urban wanderer, is explicitly mentioned by Koolhaas in his description of the Jussieu Libraries, though he more broadly invokes the flâneur through his frenetic fascination with the modern city rather than melancholic ambivalence of the individual. See Koolhaas et al, S,M,L,XL. Pg. 1324

43 The term is coined by Jeffrey Kipnis to describe what he argues is Koolhaas’ innovation of Le Corbusier’s Free Plan - which sought to apply a free-standing column arrange ment to a generic floor plan. See Kipnis and Maymind, A Question of Qualities. Pg. 96 – 104

44 Koolhaas et al, S,M,L,XL. Pg. 1310

Figure 11: Archetypical office Building on Unter den Linden, 1910-11.

39 Rowe and Koetter, Collage City. Pg. 72

Figure 12: Architectural model for The Jussieu Libraries, showing internal trajectory and manipulation of floor plates.

Figure 13: Axonometric drawing of The Jussieu Libraries (mezzanine level).

the strategy of the void at Jussieu proposes a completely new system of spatial perception.

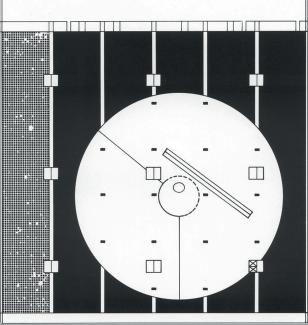

In the Dutch Embassy, the ramped ascent to the internal courtyard from Klosterstraße is the beginning of the trajectory, but these ideas more clearly coalesce to form a choreographed promenade which punctures the interior of the cubic volume. In moments where the trajectory brushes the facade of the building, the pathway stimulates a montage-like experience; framing key views of the Berlin cityscape which, as described earlier, relate to key moments of the city’s history. Most notably, the scheme incorporates a glazed corridor which burst through the building’s envelope at lower level, orientated as to run parallel with the street below and opposing former Nazi building, leading to direct view of the Spree and historic inner harbour. Further in the itinerary, a direct view of The Fernsehturm is captured via a precise cut into the opposing accommodation building, and directly above the glazed bridge, wider views of over the quays and towers of Fischerinsel are provided. Fundamentally however, it must be addressed that the programmatic nature of

the building does bear significant impact on the void’s capability, with issues of territory and public-private divide being crucial in the security of the Embassy; a somewhat cursory observation to make, but undoubtedly important in acknowledging its potential limitation in offering a performative function akin to that of Jussieu, as the introduction of any sort of ‘social magic carpet’ in such a setting would be impossible. Indeed, one could even argue that, by structuring the trajectory only around visual links to the city’s key historical moments, the building loses its autonomy. In this reading, the void holds limited agency, as its value is tied solely to its surrounding figure (i.e. the envelope of the building itself as well as the wider urban context which organises and gives performative value to the void). Clearly, both the ‘L’ shaped courtyard and the internal trajectory emerge as the dominant spaces of the scheme, with the implication that – not unlike Casa da Música - the ‘negative’ or ‘absent’ elements can become significant representative or even iconographic features of a building. Nonetheless, the potency of the void strategy lies beyond its symbolic nature (which in the rhetoric of Koolhaas, would not but evoke the devastating

Figure 14: Threshold sequence into internal courtyard of the Dutch Embassy from Klosterstraße.

Klosterstraße River Bank

Fernsehturm

Across River and Fischerinsel Park and River

Figure 15: Unfolded section of the internal trajectory in the Dutch Embassy, scale 1:400.

urban void left by the war in Berlin). Reflecting again on Stan Allen’s concept of ‘Affirmative Instrumentalism’, the use of the void here serves an operative purpose, and there are clear readings of its implementation which instead point towards a more critical dialogue with its context. As perhaps the void’s most transparent and visually striking element, the protruding glass bridge above Klosterstraße is an interesting threshold to explore. The facade illustrates a moment of the trajectory whereby the user appears to float above the street and is thus completely exposed to the gaze of the public. This introduces a sort of asymmetric dynamic, as there is a complete imbalance in the perceptive relationship between inside and outside. In Jussieu, Jeffrey Kipnis calls the manipulation of sightlines in the building a form of ‘performative discourse’45 and it is clear to see a certain degree of similarity with the Embassy. This voyeuristic tension introduces a level of vulnerability that disturbs the division between public and private space in such an institution. Whilst the transparency of the bridge allows for a kind of visual exchange, it also creates a sense of unease, as those circulating the building are unknowingly visible and disoriented due to the

glass platform beneath them. Another comparable, albeit more subtle, example of this strategy is the building’s sky box which pierces the internal courtyard of the site. In a total inversion of the trajectory’s strategy (i.e. void being carved out from a solid mass), the ambassadors reception room is a solid completely thrust, as it were, into the void of the courtyard - offering a heightened perspective view across the Spree. Whilst both spaces embody distinct manipulations of transparency and visibility, the sky box offers a more intimate, private experience, where the illusion of floating in a void likely leads to an introductory conversation for visitors.

Figure 17: View from the public gardens of the transparent corridor of the Dutch Embassy.

45 Kipnis, ‘Recent Koolhaas’. Pg. 26 - 37

Figure 16: Unfolded trajectory plan of the Dutch Embassy, showing transparency and spatial layering.

CASE STUDY 03: THE NEUE NATIONALGALERIE, BERLIN

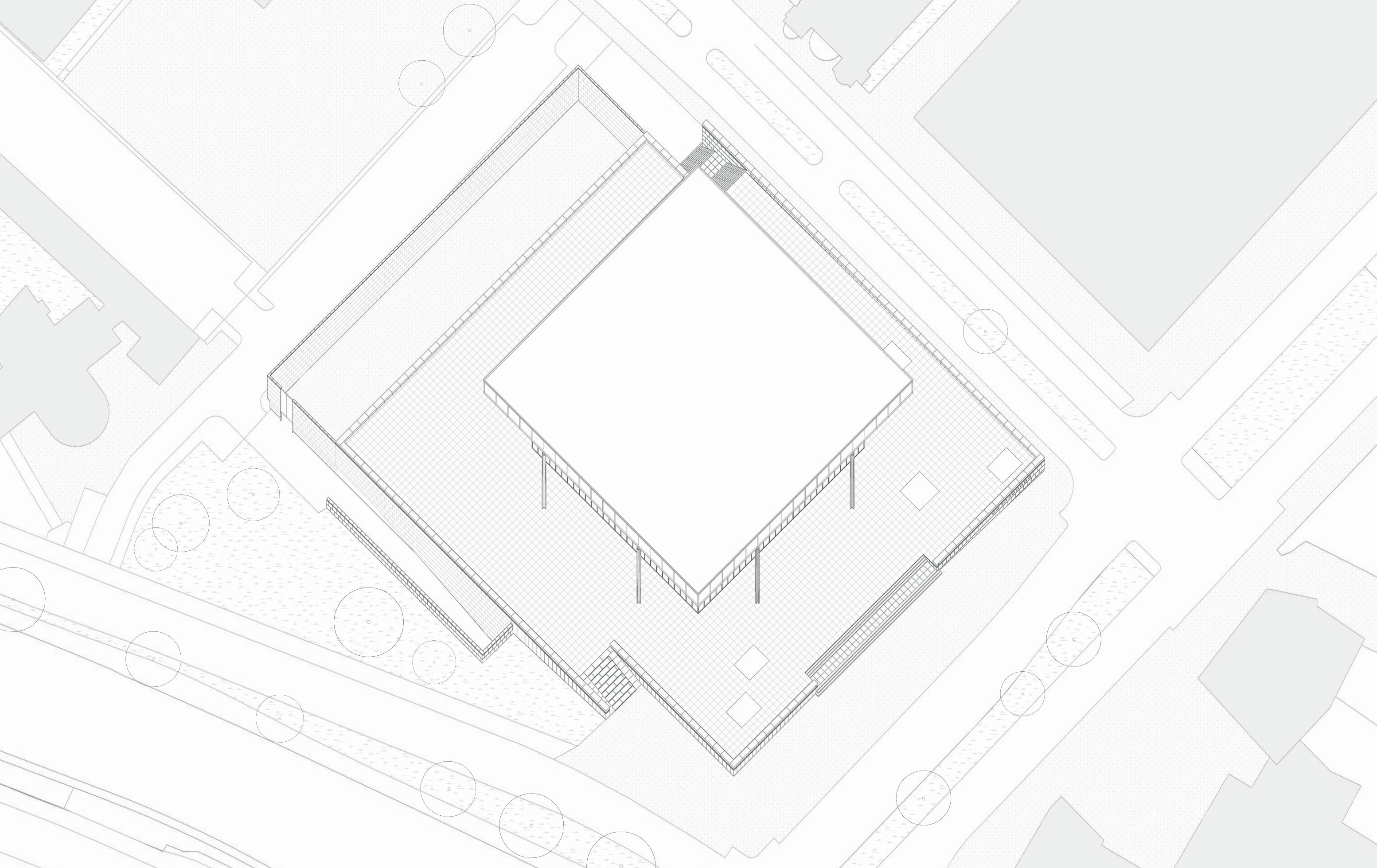

Figure 18: Axonometric drawing of Mies Van Der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie, Scale 1:500.

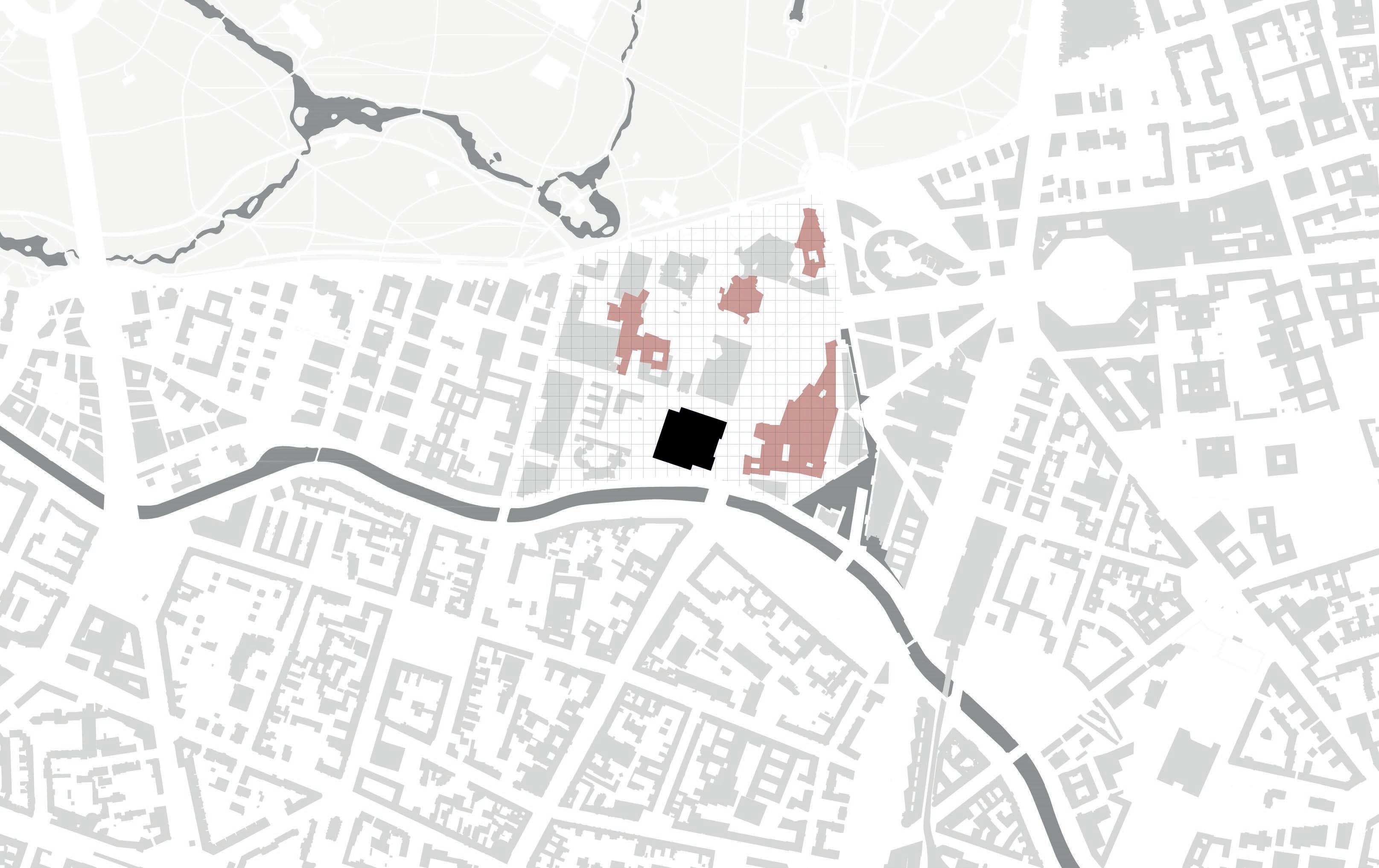

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin (1962 – 1968) has been chosen as an additional case study to explore the performative function of a void space as a design strategy. Rafael Moneo’s account of Modernism’s typological revision was briefly explored earlier in this research paper, in which the latent abstraction of space into a universal formal logic in Mies’ work was detailed. Notwithstanding Moneo’s assertion of “the idealised space through the construction of its abstract components”46 over functional categorisation of architecture; popular commentary on Mies - unlike Koolhaas – does not typically raise notions of absence, figure-ground, void, or any other such generality. Indeed, the orthodox understanding of the Neue Nationalgalerie itself, with frequent reference to the eminent Miesian aphorism of “Less is more” often portrays him as a proponent of a sober structural sensibility in Neoclassical terms. However, it can be reasoned that there are notable correlations with Koolhaas’ explored void strategies and the Neue Nationalgalerie. Both architects, as it were, deploy a void space from which an ambiguous duality between the material and the incorporeal, as well as a deliberate dialogue with a broader urban context can be inferred.

Stan Allen, in his essay ‘Mies’ theater of effects’ observes the Neue Nationalgalerie’s underlying application of ‘the virtual’ as being deeply predicated on Mies’ process of representation.47 When speaking of ‘the virtual’, Allen is referring to the optical, ephemeral effects that architecture produces such as light, shadow, and transparency, which he believes are profoundly constitutive of the experience at the Nationalgalerie. In contrast to the precise tectonic craftsmanship for which his work is largely synonymous with, Mies’ graphic representations would often obscure or completely dematerialise any architectural legibility, suggesting that Mies - as a master builder at heart – was fully conscious that the perceptual dimension of a building cannot be captured in a drawing, and thus strictly belonged in the realm of physical presence. Mies’ Collage of a ‘Museum for a Small City’ (1942) is a prime example of how he reduces the architecture to a “barely legible trace”48 instead depicting components of a landscape beyond the building thereby giving perceptual power to absence itself.

Figure 19: Neue Nationalgalerie, steel and glass facade.

While Mies’ ambiguous mode of representation is fascinating, and would certainly warrant its own line of research, what is perhaps more relevant – as Allen goes on to point out – is how it can be used to frame an alternative interpretation of the Neue Nationalgalerie, particularly when exploring the operative interplay of the building’s iconic plinth and empty, temple-like structure. Stan Allen reiterates the well-known fact of Karl Friedrich Schinkel influence on Mies, not only in a Neoclassical formal language and commonality of work in Berlin, but more significantly in the carefully choreographed representation of the urban field in both of their architecture, the panorama. Allen subsequently posits that this alternative reading of Mies, the understanding of his rhetorical sensibility and the formal composition of the panorama, may be regarded as “an architecture of image and affect, capable of establishing complex relationships with [the city’s] fragmented urban context.”49

To understand the manifestation and effect of the panorama, it is worth clarifying the sequence of programme at the Neue Nationalgalerie. Like in Koolhaas’ trajectory at the Dutch Embassy and Jussieu Libraries (which likely drew inspiration

from Mies’ building), both the idea of sequencing events and destabilisation of the ground datum are extremely important.

At the Neue Nationalgalerie, Mies constructs a deep concrete plinth which elevates the visitor, both literally and figuratively, from the banality of urban life into the world of art.50 Upon entry, the visitor is met with a totally open-plan pavilion structure, furnished only with two modest stair cores and marble-clad shafts. Hence, the user is immersed in a completely void space and is free to manoeuvre unrestricted before descending into the building’s permanent art gallery. This results in a process of inhabitation whereby the open space necessitates horizontal movement in order to stimulate a dynamic experience. Since the user is encouraged to move through different thresholds, both internal and external, they are exposed to a constantly changing view of the city. In addition, the pronounced horizontality of the building (the extension of the cornice past the facade and the expansion of the plaza’s ground-level datum) further isolate, as in Mies’ Collage of a Museum for a Small City, the cityscape from the immediate architectural frame.

Such a void space - in its absolute neutrality of transparency, circulation, light, and reflection - would be difficult to attach to

48 Ibid, Pg. 98

49 Ibid, Pg. 105

50 Böck, Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas. Pg. 212

Figure 20: Mies Van Der RoheMuseum for a Small City, 1942.

our conventional understanding of a solemn Modernist object in an urban field.51 Whilst its salient use of an industrial aesthetic asserts a kind of static autonomy (exacerbated by the disjointed urban condition of the area), the internal dissolution of materiality and superimposition of peripheral views of the city generate such a profound sense of openness and appreciation for its context that in many ways the city itself permeates the building. Whereas the Modernist city’s object, in its autonomy, would all but surely supress any relation to the immediate surroundings, the Neue Nationalgalerie uses this ensemble of perceptual ploys - the panorama as a form of image and effect – to stimulate a phenomenal experience in the building within an absence.

In this way, Mies’s construction of this void space in the Neue Nationalgalerie embodies a deep resonance with the figureground trope that has been explored thus far. Imbued with the agency to transform the area through Mies’ novel understanding of typology, the Neue Nationalgalerie offered the Kulturforum area a substantial level of urban catalysation in neighbouring architectural developments such as the Berliner Philharmonie (1960-1963). In an open reference to Fritz Neumeyer’s interpretation however, Stan Allen eschews any temptation

to attribute Mies with an aspiration toward a ‘higher unity’52 which can be seen to somewhat substantiate Collage City’s reflexive opposition of any universal prognosis of architecture. As discussed previously, both Allen and Rowe’s theories relate in that they reject any totalising ideals; and for Allen in particular, the concept of ‘material practice’ becomes relevant, as the Neue Nationalgalerie duly belies any impulse to impose any type of transcendental logic beyond the site.53 Instead, the central void space of the Nationalgalerie serves a seemingly paradoxical purpose. Unlike Casa da Música, the void does not precede any compositional articulation, but rather corroborates with the building’s distinct tectonic configuration to produce a “delicate choreography of object and urban field.”54 That is to say, the void at the Neue Nationalgalerie gains agency through its mediation with the building’s material presence, producing experiential effects like the expansive panorama. However, it would therefore seem as though such an effect cannot become universally transferrable. If, as Allen contests, the effect is forged by Mies’ carefully calibrated unity of illusion and construction, the void may not be capable of sustaining any intrinsic value aside from its immediate architectural circumstance.

51 Allen, Practice. Pg. 105

52 Neumeyer, ‘Space for Reflection: Block versus Pavilion’. Pg. 196

53 Allen, Practice. Pg. 105

54 Ibid. Pg. 105

Figure 21: The Neue Nationalgalerie, view from plaza of adjacent St. Matthäus-Kirche.

Figure 22: Location of The Neue Nationalgalerie, showing engagement with urban area and adjacent public buildings.

This research has explored architectural projects which represent varied and innovative manifestations of the strategy of the void, each revealing a unique set of interactions with congruent architectural elements as well as a wider urban context. The spectrum of performative and compositional contingencies within each of these buildings was vital to the initial methodology set out for this research, recognising the void’s capacity to mediate between built form, the city, and perceptual experience. Accordingly, this research has determined that there are unique strategic outcomes that can be achieved through the application of the void. Koolhaas’ Casa da Música for instance, exemplifies a more static application of the void, where its iconic auditorium serves as a conceptual and functional organiser for the adjacent spaces but remains largely inward-focused. In this way, the void becomes a compositional and iconographic diagram, maintaining a relatively linear, scenographic interaction with the broader urban fabric. Conversely, the Dutch Embassy and Mies’ Neue Nationalgalerie reveal a dynamic interpretation, whereby the void necessitates a choreographed sequence of movement to manifest a reciprocal engagement with the city.

These diverse applications all provide commentary, in one way or another, on the agency of the void to operate as an autonomous architectural device, providing fertile ground for discussion on the typological and operative dimension of the void in architecture. Notwithstanding architecture’s longstanding, and extensive theoretical preoccupation with figureground dynamics, this research intersects with today’s broader discourse on social sustainability, particularly in its everchanging urban context. Contemporary design in global cities has for the most part been dominated by the proliferation of overly dense and aesthetically cluttered spaces. The strategy of the void thus offers an alternative perspective, advocating for a spatial milieu that is sensitive to the dissonances and transformations symptomatic of contemporary, globalised urban landscapes. This ultimately aligns with the UN’s approach to social sustainability, as outlined by their sustainability goals, which emphasise the importance of inclusive, accessible, and equitable spaces in urban environments. By advocating for void as an armature in a design sense, architectural practice can better respond to the needs of diverse communities, ensuring

that public spaces are not only functional but also supportive of social interaction, mobility, and as explored in this research, innovative performative qualities within the architectural experience. This thesis does not claim that the strategy of the void can be adopted as an autonomous mechanism; nor that it foregoes any agency at the discretion of external phenomena. As has been maintained in this research, the agency of the void is relational, and as such, it offers an alternative method for simultaneously recognising and reinventing the city.