new wave journal

Cornwall Film Festival’s New Wave Jury is a group of young film writers and reviewers who watched and selected a winner for the festival’s International Short Film competition 2023.

They were also invited to review a film from this year’s festival for this journal.

Publisher - Louise Fox

Art Director- Sue Lewis

Editor - Tomás Basilio

Designers - Anne Butler

Lara Abbey

Contributing Editor- Amanda White

Cover image of Bella Baxter from Poor Things

by Caoimhe M. HarleyThe otherworldly beauty of Poor Things

By Rebecca Jackson

Poor Things, (2023)

a fantastical return to old school filmmaking.

An eerie blue sky frames the face of an unknown woman. She wears a Victorian dress which strangles her throat, and her jet black hair is gathered into a meticulous updo. Her large, glassy eyes are heavy and world weary. Below her, the Thames seethes and boils. The image is hauntingly beautiful, but there is a strange, uncanny quality to it. The sky is too blue. And that water…

Enter Bella Baxter, played by Emma Stone. She has the face of that melancholic woman we met on Tower Bridge, but her formerly neat hair now cascades down her back, and her once tired eyes are bright with curiosity. What has caused this transformation? ‘It is a happy tale’ proclaims the scientist Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe), before he joyfully recounts reanimating the corpse of the mysterious unknown woman, and replacing her brain with that of her unborn child. Thus begins possibly the most outrageous, brilliant film of 2023.

We watch on as Bella, with her infantile mind and unsteady gait, embarks on a journey to discover all that the world can offer her. This includes, but is by no means limited to: masturbation, custard tarts and sex. She is aided in this endeavour by Duncan Weddenburn, a lothario played by Mark Ruffalo with all the pompous lechery you could wish for from a true Victorian rake.

“ From ceilings plastered with giant ears to phallus shaped windows, every inch of the screen is imbued with a wonderfully perverse humour. ”

Their travels take them across an imagined Europe of dazzling sci-fi invention. From exquisite miniatures to vast constructed soundstages, the ambition of ‘Poor Things’ production design harks to an era of sumptuous technicolour and unbridled creativity. Taking inspiration from the likes of Powell and Pressburger, designers James Price and Shona Heath combined traditional filmmaking techniques with modern technology such as giant LED screens to create an immersive and fantastical world that is breathtaking in its detail. Alternative imaginings of European cities appear on the screen as if it’s coloured with the vomit of a child who has eaten a packet of Skittles. Rooms that at first glance would look at home in any period drama, reveal hidden details upon further inspection. From ceilings plastered with giant ears to phallus shaped windows, every inch of the screen is imbued with a wonderfully perverse humour.

However, despite its brazen surreality, the film remains rooted in its late Victorian setting through art nouveau design elements. The decision to use the architectural style of the 1890s, rather than the early 1800s when the novel is set, is a stroke of genius. Unlike the stark geometric forms of the neoclassical style, art nouveau lines are sinuous and sensual, taking inspiration from the natural world. Notably revived in the 1960s, the style is already associated in the public imagination with the strange and psychedelic, lending it perfectly to the dreamlike, bodily inspired details of this strange universe.

“Rather than distract from the substance of the film, its design serves to enhance and enrich its bold themes.”

Colour plays an integral role in the films storytelling. In a nod to The Wizard of Oz, Godwin’s home, where Bella spends her early life, is entirely black and white. It’s only when she escapes that she experiences the world in its true kaleidoscopic brilliance. Perhaps most vivid of all is the blood red of the home of her monstrous first husband, a man for whom violence is a way of life. In the expressionistic style of Dario Argento, this terrifying hue seeps into every corner of the screen. Rather than distract from the substance of the film, its design serves to enhance and enrich its bold themes. Much like a macabre fairytale can be repacked as child friendly by being set far, far away and populated with unearthly characters, the stylized setting of Poor Things allows its darker themes to be more palatable.

Lanthimos has taken the familiar aesthetics of an era heavily associated with oppression, and transformed it into something salacious and outlandish. This juxtaposition that perfectly compliments the story’s anarchical messaging. This is, at its heart, a film of dichotomies. Nature, desire and freedom come at odds with civilization, repression and entrapment. Emma Stone plays the woman liberated, unencumbered societal rules and expectations. We watch on gleefully as this puts her at odds with the men around her. Though at first enchanted by her lack of inhibition, Duncan Wedderburn is subsequently embarrassed, then horrified, and ultimately ruined by her as he scrambles desperately to uphold the societal conventions that he initially professed to disdain. All the while Bella Baxter continues to dance through this dizzying world, ever growing and changing and learning.

Much like the human bodies that are dissected and pieced back together over the course of the film, at times the story feels messy; the messaging overwrought. But I hesitate to criticise it for this. If anything, it made me wish I could stay longer with this complex, hilarious and completely original creation.

@ameliarobinsonstills

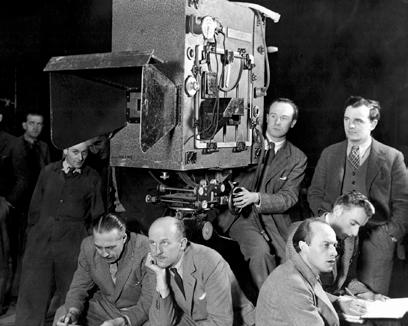

Film : A Matter of Life and Death

A Matter of Life and Death, (1946)

By Amelia Robinson

A Matter of Life and Death (1946) –

by Amelia RobinsonThere is absolutely nothing new I can bring to this review that is unique and groundbreaking but, watching this for the first time in the cinema surrounded by people who have seen and loved the film felt unique. Powell and Pressburger’s ‘A Matter of Life and Death’ depicts postwar ideology of love conquering all by showing the depth of human imagination by tragedy. It is in our nature to think that whatever is in the next life is everyone’s personal heaven and all is organised, but what happens when one person cheats death by accident? This is a spoiler warning if you need a warning about a film that is 77 years old.

“Having a red blinking light behind June and a burning red fire behind Peter unites these two lovers in a tragic scene.”

Peter Carter, an RAF pilot, should have died like so many others days before the war was over yet gets lost in the fog (darn English weather). In the time before he dies, he very quickly falls in love with a Boston born radio operator called June. This scene is absolutely stunning. Having a red blinking light behind June and a burning red fire behind Peter unites these two lovers in a tragic scene where we believe that Peter does in-fact die. The colour red is present throughout the film which is only enhanced with the black and white scenes of the other world, Peter is being shown how much love and life he could have if only he had a parachute. He somehow survives and ends up minutes away from June on a scenic beach (the only shot actually outside).

“Whilst preparing for his trial, we learn that Peter is a poet through Doctor Reeves. This questions the whole narrative, does the other world actually exist?”

However, this does not last long as Conductor 71, from the other world, comes to take Peter back and set the records straight, but Peter is determined to have a fair trial, having this in a rose garden full of blooming colour but also so still: “we are talking in space, not in time”. I am consistently impressed by how still the actors are in some of the conductor scenes, and that ping pong scene is great (who knew I would find ping pong artful).

Whilst preparing for his trial we learn through Doctor Reeves, that Peter is a poet. This questions the whole narrative, does the other world actually exist? Or is it all in Peter’s head? I believe it is all hallucinations but the film balances the question very well so that both sides of the argument are strong. Doctor Reeves himself says he believes Peter is suffering from “highly organised hallucinations” which would explain why his mind is making up the trial to justify and explain why he is alive. Peter could be experiencing survivors’ guilt, his Captain died yet he somehow managed to survive so he makes up this other world where the Conductor somehow misses him in the fog to justify his existence. He could be making it all up to cope with the finality of death.

The other world is shown as clean and modern with no sharp corners, white and pure but still with the presence of time. It almost seems unrealistic that this other world where we go to when we die is still bound by time when the conductor can stop time as a simple trick (you see, it is all in Peter’s head of course). The zoomedout shots are stunning and highlight the fantastical element of this film but keeps it based in some sort of reality and familiarity. Everyone has a place and a job. The stairway to heaven is one of the most beautiful and technical shots in the entire film and serves as the pathway through the universe between the two worlds. The clinical surgery room that Peter goes to towards the end of the film is white, sterile, organised. Remind you of anywhere?

The trial of Peter becomes the trial of the British Empire as there were very few nations in which the British had not fought. Doctor Reeves (who is now in the other world because he died, come on keep up) ends up choosing a jury full of American’s because he knows that they believe in freedom, justice and love. His argument is that Peter was merely given the 20 hours not borrowing them as it wasn’t his fault he survived, and in that time, he managed to fall in love with an American girl (how scandalous). His job is to prove that love and give Peter the chance to live with June, even if it is for a short while. Peter faces the court of appeal from the other world in his RAF uniform not his blue suit he has been wearing for most of the film. Is this to appeal to the other ranking officers in the court? Maybe? Either way it works and Doctor Reeves successfully shows that the laws of love are stronger on earth than the laws of time and space, with June willing to die for Peter because the lovely Shakespearean inspired tear on a rose isn’t enough to show love. “There is no sense in Love.”

It is interesting to think about what the initial reaction to this film was for a 1940s audience compared to 2020s audience, are we not as blinded by the amazing use of technicolour and do we not relate as much to the post war commentary? Obviously the rewatch value of this film is high, it is easy to pick apart every scene discussing the intricacies of ideology, national identity and personality after death but most importantly: it is just a good film and holds up 77 years later.

14 Theater Camp, (2023) Theater Camp, (2023) Theater Camp, (2023) Theater

Theater Camp

By Archie SellensThere are two films that have come out this year that showcase a new generation of comedians and actors: Bottoms and Theater Camp. If, like me, you follow the stars of these films closely, you’ll know that they are connected socially as well as professionally. Molly Gordon for instance, star of Theater Camp, was also a significant part of Emma Seligman’s award-winning Shiva Baby, alongside Rachel Snennott, star of Bottoms and longtime collaborator of Ayo Edebiri, who is in both Theater Camp and the aforementioned Bottoms. What all these films have in common, for me at least, is that they feel genuinely representative of a generational perspective that, even if it is a few years ahead of mine, feels relatable, and also uniquely funny and insightful.

While I am not a theatre kid, and have tended to avoid the ‘stage crew’ crowd throughout my life, what this film offers is a representation of a world that is so clearly inspired by the lived reality of its creators and performers that one can’t help but be swayed by its charm and extravagance. Through its two lead characters, played with expert humour and pathos by Molly Gordon and Ben Platt, Theater Camp explores the dynamics of co-dependent friendships that exist mainly to protect each person from their anxieties and dissatisfaction with the trajectory of their social and professional lives. While the dynamic explored in the film is specific to the crushing disappointment experienced by so many young actors when confronted with the reality of a cruel and punishing industry, this theme of isolation and dissatisfaction is one that is widespread amongst a generation excluded from the economy that worked so much better for their parents.

Archie Sellens

“Theater Camp explores the dynamics of co-dependent friendships that exist mainly to protect each person from their anxieties and dissatisfaction with the trajectory of their social and professional lives.”

There are so many differing narratives to unpick from throughout the film, but one character that stood out for me was Troy Rubinsky, the young ‘jock’ played by Jimmy Tatro, who is tasked with saving the camp from dissolution after the death of his mother, who had run it with great care previously. Similar to Bottoms, Theater Camp plays with traditional tropes from the ‘high school’ and ‘summer camp’ movies of the past and adapts them to a new generation, and Troy is a great example. While in the past, movies about high school age stories (think Mean Girls, Wet Hot American Summer) were normally told by the outsider, looking in on the dominant social cliques with ironic disdain, movies like theatre camp showcase how much changing social dynamics have altered the power balance. In Theater Camp, Troy’s character, as a ‘jocky’ hypermasculine ‘bro’, finds himself on the outside of the close-knit community of theatre enthusiasts at the camp, and is forced to find deeper levels to himself in order to connect with the kids he grows to care deeply about. Having said this, Troy himself is more than the caricature of a podcasting, misogynistic tech-bro you see plastered all over instagram reels. Instead, he proves to be tender, caring and, eventually, open-minded to the eccentricities and complexities of the camp and its residents. This new brand of high school comedy no longer succumbs to broad-based caricatures of the ‘jock’, the ‘nerd’ et cetera, and instead not only subvert these archetypes, but gives us characters who defy stereotyping whatsoever, in a rejection of the social order that in itself is representative of younger people’s widespread of American cultural and political orthodoxy in 2023.

“the opportunity to make the kind of movies they want to, without the pressure of conforming either to ‘bankable’ traditions or to the limits of genre.”

Aside from its representations of social dynamics, Theater Camp is also full to the brim with fantastic comedic performances. Ayo Edebiri and Patti Harrison in particular stand out for their sardonic takes on an unqualified teacher and a hard-nosed capitalist, both delivered with the skill and confidence of two performers who know what their voice is, and how to use it. Edebiri is one of those actors whose trajectory towards the top feels inevitable at this point, and I think it is to be celebrated that actresses like her, Gordon, Harrison and the like have been given the opportunity to make the kind of movies they want to, without the pressure of conforming either to ‘bankable’ traditions or to the limits of genre. In an era where the older generation of American comics consistently use their platforms to express their thinly veiled horror at the open-mindedness and confidence of ‘woke’ young people who want to ‘cancel them’, it is refreshing and empowering to see young female comic actresses given the freedom to showcase their talent, within creative vehicles that challenge perceptions of marginalised people through well-constructed representation, that is not tokenistic, but instead pure and real, and doesn’t sacrifice humour and performance for the sake of social commentary, but unites the two in a satisfying and enjoyable manner.

I will be keenly observing the burgeoning careers of Gordon et al, and hope that we only see more and more films in the same vein as Theater Camp : feel-good, funny movies that challenge norms of both Hollywood and those of the media landscape in general, and do so through brilliant writing and performances that bode well for the future of comedy, once its escaped the withering grip of older male club comics, and is taken over by young people who use it to open minds and hearts, all while being twice as funny.

www.caoimhemakesfilms.com

Film : Poor Things

Poor Things, 2023

Poor Things: Feminist Hysteria

“At its simplest, the argument goes like this: if women’s sexual autonomy has given them wicked and tyrannical control over men’s lives, then women’s liberation is at the root of all male suffering. Therefore, the obvious remedy is to remove women’s freedom and independence, and to use specifically sexual means to do so. In other words, the problem is not women having sex, but women having the choice of whom to have sex with.”

Laura Bates, Men Who Hate Women

It begins with quilts — a symbol of the home. A setting historically destined for the wealthy woman, girlhoods domesticated by needlepoint and etiquette. Home is all Bella Baxter (Emma Stone) has known. Kept under the watchful eye of her creator Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe) and his keen student Max McCandless (Ramy Youssef), Bella is a wideeyed woman born from curiosity. A product of unorthodox experimentation, a result of Godwin’s own (unironic) desire to play God, to fish a woman’s body from the Thames and to replace her brain with that of her unborn child’s. Heinous! And yet, we cannot help but feel the same as Max in his intrigue. We watch her as he does, her cognitive development rapid, her growth a result of her own inquisitiveness of the outside world and newfound sexual desires. Home cannot confine her for much longer.

It is the restraint placed on Bella by the men in her life which induces her freedom. Her imprisonment is idle, an attempt made to combat this by Godwin’s arrangement of Bella’s engagement to Max — yet another form of captivity for Bella. Once introduced to the ridiculously opulent London lawyer Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo) hired to write up a rather unfair contract pertaining Bella’s mildly problematic engagement to Max, Bella gets a taste for the sexual freedom she had only been shamed for on the basis of being ‘improper’ amongst high society. Duncan admires what he believes she is — an easily controllable, hypersexual being whom he can woo with his wealth and passport. After all, Europe is much grander than the home and the rooftop Bella is acclimate to, whisked away by Duncan with Godwin’s permission and Max’s nescience, all under the pretence of adventure and sexual liberation. Still we see Duncan’s façade crumble very swiftly — his wealth from gambling, his use of crude language juxtaposing his received pronunciation lexicon, in turn revealing the farcical nature of high society. And yet when Bella defies the high society Duncan so earnestly claims to hate (through her sexuality and naive honesty), he becomes threatened, kidnapping her to restrain her once more.

“ It is through the claiming of her own self, mind, politics, style, and sexuality that she becomes her own woman — not a product the men around her so desperately wish for her to be. ”

Undeniably, Bella’s sexual liberation is what sets her free. Between the 19th and 20th century, women who acted similarly to Bella were seen as hysterical — a point of view Duncan seems to share, alongside a belief that she can be ‘tamed’ through marriage (a genuine reported treatment for female hysteria). However Bella’s concerns are greater than quelling this falsehood. A new radical friend, Harry Astley (Jerrod Carmichael) opposes Bella’s optimism and guides her towards philosophy instead. Eventually stranded and out of money, she turns to sex work in order to discover herself and the world around her. It is through the claiming of her own self, mind, politics, style, and sexuality that she becomes her own woman — not a product the men around her so desperately wish for her to be. This is why I find the quote from Laura Bates at the beginning of this review so poignant — although fiction, I cannot help but feel Bella’s disposition myself. The excitement towards Bella when she expresses desire,

Undeniably, Bella’s sexual liberation is what sets her free. Between the 19th and 20th century, women who acted similarly to Bella were seen as hysterical — a point of view Duncan seems to share, alongside a belief that she can be ‘tamed’ through marriage (a genuine reported treatment for female hysteria). However Bella’s concerns are greater than quelling this falsehood. A new radical friend, Harry Astley (Jerrod Carmichael) opposes Bella’s optimism and guides her towards philosophy instead. Eventually stranded and out of money, she turns to sex work in order to discover herself and the world around her. It is through the claiming of her own self, mind, politics, style, and sexuality that she becomes her own woman — not a product the men around her so desperately wish for her to be. This is why I find the quote from Laura Bates at the beginning of this review so poignant — although fiction, I cannot help but feel Bella’s disposition myself. The excitement towards Bella when she expresses desire, and disgust towards her when she acts upon it reveals deeper hegemonic attitudes towards women’s sexuality, all conglomerating into a prevalent rape culture which is everpresent today. At one point, Bella is threatened with FGC (an extremely harmful practice involving the female genitalia which is still performed today) as a form of punishment for Bella’s sexuality in a further attempt to tame her, and an alarming reminder of similar contemporary beliefs. Bella’s sexual freedom is beautifully defiant, alleviated by the fact that she knows this. Perhaps my favourite line from the film was when she was confronted by Duncan about her sex work, to which she responds, “you’re our own means of production”. As much as men can mock her, Bella is not the subservient innocent figure they wish her to be, and she will always have that power through her own independence and reclamation of her alleged ‘hysteria’.

and disgust towards her when she acts upon it reveals deeper hegemonic attitudes towards women’s sexuality, all conglomerating into a prevalent rape culture which is everpresent today. At one point, Bella is threatened with FGC (an extremely harmful practice involving the female genitalia which is still performed today) as a form of punishment for Bella’s sexuality in a further attempt to tame her, and an alarming reminder of similar contemporary beliefs. Bella’s sexual freedom is beautifully defiant, alleviated by the fact that she knows this. Perhaps my favourite line from the film was when she was confronted by Duncan about her sex work, to which she responds, “you’re our own means of production”. As much as men can mock her, Bella is not the subservient innocent figure they wish her to be, and she will always have that power through her own independence and reclamation of her alleged ‘hysteria’.

“ It is a delightfully eccentric tale of death, rebirth, and the self-discovery of one Bella Baxter. ”

“ It is a delightfully eccentric tale of death, rebirth, and the self-discovery of one Bella Baxter. ”

With outstanding production design by James Price and Shona Heath reminiscent of Jean-Marc Côté’s 19th century illustrations of the year 2000, Yorgos Lanthimos has created a world in which the strange thrives. Everything is familiar, and yet simultaneously awfully bizarre, making Bella’s growth all the more intriguing. Based on a book of the same name, Poor Things shifts slightly and does an outstanding job of focusing on Bella as the lead point of view, as Stone’s performance is an incredibly adept testimony to consistent yet ever changing character work, proving the case that seemingly popular ‘angry =

good acting’ rarely holds a candle to strong subtlety. Enthusiastically matched by Ruffalo, Dafoe, and supporting cast, Poor Things marvellously stands out amongst Lanthimos’ filmography as a delicate yet empowering body of work. It is a delightfully eccentric tale of death, rebirth, and the self-discovery of one Bella Baxter. She was born already a woman, only to be shaped by a system into someone outside of the cookiecutter it perilously tried to shove and squeeze her into — and that is a thing to be cherished.

With themes of autonomy reminiscent of Mikahail Bulgakov’s The Heart of a Dog and H.G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau, Poor Things does not shy away from its postmodern retrofuturist lineage. With outstanding production design by James Price and Shona Heath reminiscent of Jean-Marc Côté’s 19th century illustrations of the year 2000, Yorgos Lanthimos has created a world in which the strange thrives. Everything is familiar, and yet simultaneously awfully bizarre, making Bella’s growth all the more intriguing. Based on a book of the same name, Poor Things shifts slightly and does an outstanding job of focusing on Bella as the lead point of view, as Stone’s performance is an incredibly adept testimony to consistent yet ever changing character work, proving the case that seemingly popular ‘angry = good acting’ rarely holds a candle to strong subtlety. Enthusiastically matched by Ruffalo, Dafoe, and supporting cast, Poor Things marvellously stands out amongst Lanthimos’ filmography as a delicate yet empowering body of work. It is a delightfully eccentric tale of death, rebirth, and the self-discovery of one Bella Baxter. She was born already a woman, only to be shaped by a system into someone outside of the cookiecutter it perilously tried to shove and squeeze her into — and that is a thing to be cherished.

William Armitage

@williampraseyto

Film: Mångata

A lonesome sea crossing between Africa and Europe engulfed in dark. Twin identities. A mission to the stars. A lone astronaut on the surface of the moon faced with the recognition of her own past.

Mångata (coined after the Swedish phrase describing the long light of the moon and how it reflects upon the dark sea) pulls off a sort of magic trick, somehow fitting all of these intense visuals and ideas into a short film and does it with bravado. There is no wasted second here. Combining a

tragic reality for many that cross the Mediterranean with this inner struggle of our main character, Alya, as she becomes an astronaut sounds like it would be difficult to show on such a short runtime, but Mångata solves this and dazzles. The sound of the Mediterranean Sea lapping at the makeshift boat is painfully real. A handheld one shot of a busy pre-space mission briefing drags the viewer right into buying a lofty set up, and the authentic African instrumentals contrasted against the hard sci fi, always haunting and always inspired.

Mångata feels like a sizzle edit of a much longer, more expensive film but not as a subtraction, with its

Mångata

independent roots Mångata still remains with its tender heart and compelling script that such larger films sometimes sacrifice. The main genre of the film for example, science fiction but blended with an immigrant story, is so enthralling and something that is rare to see. A special mention has to go to the main actress, such a grand plot sweeping years and across culture is balanced elegantly by Stefany Fruzzetti’s quiet but layered performance. A professional and reserved mask hiding such tragedy and pain in the face of watching eyes which by the end gives way to such a heart breaking sort-of regression to the child she used to be, which ties the entire movie together. Again, a magic trick to have such vastly

different scenes. To begin with a child immigrant scared to the whims of the ocean listening to the words of her father and to end with a grown woman travelling an interstellar distance alone, wishing she could stay longer to hear her father’s words once more.

The last image of the film, Alya standing alone, face towards an open horizon above with the astronaut visor slamming down to reveal the reflection of the moon and it’s Mångata, will remain with me for a long time. An undoubtable cinematic image, but one that is soaked with so much more. “Will you represent Africa or Italy?” asks a reporter to Alya at one point, a deliberately simple reduction of very complex issues of a

dual identity, but one that highlights Alya’s motivations even more so. Alya travels to the moon not for a country but to follow Mångata, which her father described so many moons ago, to seek finality, a completion that she never got that cruel night. Alya leaves behind a memento on the moon, she chooses to represent herself first, and leaves the moon free of the baggage that was forced upon her. For she does find him up there, amongst the stars, and he will always be there. Showing a path to the moon so Alya can always find him again, a Mångata.

“Mångata feels like a sizzle edit of a much longer, more expensive film but not as a subtraction, with its independent roots Mångata still remains with its tender heart and compelling script that such larger films sometimes sacrifice.”

Fallen Leaves

Film: Fallen Leaves

ARTHUR CASE: “You’re so profoundly sad.” BETTY DRAPER: “No. It’s just my people are Nordic.” (MAD MEN; S2E3: “The Benefactor”)

With the release of THE OTHER SIDE OF HOPE in 2017, Aki Kaurismäki was said to have retired from filmmaking, 6 years later that has proven not to be the caseFALLEN LEAVES is the follow-up to Kaurismäki’s seminal Proletariat trilogy (1986-1990), a worthy return of typical punctuality (81 minutes and done). A cinephile’s second hand love story, BRIEF ENCOUNTER-esque. The already initiated will know Kaurismäki’s cinema as droll and humanist, for all their imperfections he is very much a people person, and this is very much an Aki Kaurismäki film, which is to say it is also peerlessly dry. There are few ‘tricks’, the film’s unsubtlety doesn’t stop with its title. An ensemble of loose change, wage-slaves, down-and-outs, has-beens, dreamers--me and you--foregrounded against the neighbouring Russian invasion of Ukraine and, as usual, the general scourge of late-stage capitalism, Kaurismäki’s bleak social realist foundations remain, though the man has softened with age. What might easily be anticipated as dreary is rather a tender, off-kilter testament to a divinity in unity, that things are never too late.

Starting with Ansa (Finnish for “virtue” and/or “trapped”), played by Alma Pöysti, replenishing stock in a supermarket, a familiar purgatory to me. Days feel rehearsed, meals microwaved, stolen half-smiles; the frustrating meaninglessness of ritual phatic

language. What these jobs lack in mental stimulation is compensated with joint pain. She goes home and listens to her analogue radio alone, the news bad, the music melancholy. Subdued as the pale pastel blue of her favoured overcoat, a second skin. Then there’s Holappa (translates to “slave” or “soul”), first name unknown, played by Jussi Vatanen. A slick-haired, dark-clothed, sad-sack manual labourer. An alcoholic, “drink[s] so much because [he’s] depressed... depressed because [he] drink[s] so much,” he laments. Haloed with vague anguish, empty glasses caressed like crystal ball. Taking refuge in the cyclical certainty of self-sabotage.

The sequence in which Ansa and Holappa’s paths first cross is one of the film’s most beautiful. At one of the local pub’s karaoke nights, a sort of lost souls convention, the camera patiently cuts between the two’s furtive glimpses as they mature into a more kindred gaze, both sets of eyes widened by the dare to dream; to be seen. Ansa’s next encounter with Holappa who is incapacitated by alcohol at a bus stop inspires one of the film’s only uses of non-diegetic sound, Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique, any notion of hyperbole disarmed by its earnestness, the consummation of their cosmic bond. Their souls rhyme in a particularly poignant match cut sometime later into the film: separate from each other, Ansa listless on the sofa to Holappa curled on a park bench, the film now silent but for the industrial murmur of Helsinki after dark. Alma Pöysti said of the film that “it takes courage to fall in love later in life.” The interplay between the oppressive tedium

of their existences and the novelty of their encounters makes them all the more charming, an absurd restraint to the performances necessitating that actions speak louder than words; post cinema date, Ansa’s stilted goodbye kiss to Holappa carries existential affirmation.

“I don’t even know your name. Can I walk you home?” “I will tell you next time. I live nearby.”

Who hasn’t known the aching uncertainty of “next time”? Such is the film’s economy that a shot of a pool of cigarette butts renders buoyant longing. In such gestural clarity Robert Bresson’s influence is clear, Kaurismäki a known admirer. DIARY OF A COUNTRY PRIEST is even likened to Jim Jarmusch’s THE DEAD DON’T DIE in the film’s funniest line while a large poster of L’ARGENT hangs in the cinema the pair visit.

Aesthetically measured: somewhere between Hopper and BALAMORY, there’s a drab-cartoonish eloquence to the use of primary and earthier colour within steady, painterly composition. Modernity sparsely visual, interiors dated, electronics infrequent - perhaps no surprise from the man who once deemed cinema as having died in October 1962 and left Finland for Portugal in ‘89, but you feel this aesthetic nostalgia could speak to a larger sentimentality for old-school romance, connectedness; a Finland worth sticking around for. A quick look online confirms Finland as the happiest country in the world for the 6th year in a row, a fact blanketing a mythologically rowdy alcohol culture, there even exists a word in Finnish for people who stay at home to get drunk in their underwear. This discord is key - Kaurismäki’s bread and butter, quintessential “tragicomedy”, while I find much more

appeal in the first half of that term, the quaint distinction of the film’s colour palette and deadpan wit enables the inevitable overcoming of adversity to play so well. A hyperreal fairytale; another world not quite our own, Aki Kaurismäki its benevolent god.

I could go on.

At the end before the lights had even come back on I heard someone behind me complain that this is nothing they hadn’t seen before from Kaurismäki, while I don’t really disagree, this is a winning formula for me. I got what I came for. Modest magic. I’ve heard others call it hollow, underwhelming, the humour off putting, I can see how it might feel unfulfilling but in its awkwardness lives truth. Not necessarily “happily ever after”, but concern for any material loose end is sidelined by hope. Love: lazarous, a lighthouse. That the final scene—in spite of all worldly conspiracy to the contrary—allows Ansa and a renewed, sober Holappa to walk together toward a burgeoning sunrise, trailed by a dog named Chaplin, is profound. That, is cinema.

@harveypenson

Film: Poor Things Poor Things (2023)

Poor Things is a wild randy tale of entrapment and bodily freedom, with a remarkably fearless performance from Emma Stone, an extravagant new entry from Yorgos Lanthimos, though surprisingly friendly.

Adapted from Alistar Gray’s 1992 novel, Poor Things is the story of Bella Baxter (Emma Stone) a reanimated woman with the brain of newborn baby, created by her lab father Dr Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe), Bella must learn how to control her body and discover what it means to be human on a mind altering journey in the company of a liberating but tightfisted lawyer: Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo). As a revision on the Frankenstein story, Poor Things becomes a hilariously quirky, off quilter

comedy, where Emma Stone has the chance to go to extreme lengths in a singular performance as the ever growing and evolving Bella. Bella starts off as an infante in a grown body uttering simple animal noises and words with an unstable gait, but gradually develops to an intelligent sarky woman who can free herself from the male bonds she is entwined.

From the otherworldly atmosphere and design to deadpan and witty dialogue, Poor Things is a natural vehicle for a Greek auteur such as Lanthimos, from similarly mad and beguiling works such as Dogtooth (2009), The Lobster (2015), The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017), and his last Oscar winning period comedy The Favourite (2018). Lanthimos

has a distinctive knack for surreal black comedy that makes you wonder whether you should be laughing or even screaming at times, but his latest extravaganza is arguably his most friendly and accessible film to date. For all its outlandish idiosyncrasy, Poor Things is a much tamer and less compromising entry, which in turn becomes both a virtue but kind of a drawback.

To our joy, we get to witness an ensemble of professionally bizarre performances, most essentially Stone, but also an unexpectedly devilish comical turn from Marvel star Mark Ruffalo,

a laugh out loud crazed scientist inhabited by the legendary Willem Dafoe, but by now it’s a given what Dafoe is capable of. It is most definitely Emma Stone’s show who is giving her most dedicated performance, physically and mentally, though if there is one thing that the entire cast share is their superb comic timing which is delivered with the upmost and dynamic manner. From Ruffalo’s slimy and manic remarks to Dafoe regaling one liners about his unorthodox surgical implants.

What has sparked the most attention since its premiere at the Venice Film Festival, is the film’s high volume

of sex scenes, where Bella fully indulges in all kinds of pleasure once she has had her first taste of arousal. The frequency of these activities is high and ridiculous, but why it has caused so much talk could be down to the surprise of seeing preconceived actors like Stone and Ruffalo suddenly going at it like animals. In Stone’s case, this does feel a first to see her so physically committed, with the exception of her imaginary sex life from Easy A (2010), but if you want more of Ruffalo’s cinematic libido then you can check out Jane Campion’s In the Cut (2003), and The Kids are All Right (2010).

Bella’s sexuality is one of the most essential parts of the story, because if it feels good why not do it all the time?

As Bella comes to know her body better is when she learns how to control it, and this theme is Poor Thing’s strongest commentary, especially in a time where the individuality of the human body is in great discussion.

But its overarching trail is an inspiring feminist adventure about liberating yourself from a world surrounded by constant male entrapment. It’s an honourable and agreeable narrative but doesn’t offer much new to say to the matter and for all its magically inventive creation Poor Things lands a little ordinary. Lanthimos’s more disturbing elements of his pictures is generally lacking which is what makes his films more striking and thought provoking. The

Poor Things (2023) Yorgos Lanthimos

central existential questions of the drama are not as complex as they could be, and it resolves these issues in safe territory, but what you are left with is still a deliciously hysterical experience that you can’t resist enjoying.

It can’t be ignored that Poor Things is an irresistible visual feast and wonderous creation, from the steampunk Victorian England to the hyperreal colours and Gillem esc carnival look of Europe, I almost wonder if this is the imagined psyche Lanthimos’s characters finally coming to life. James Price and Shona Heath’s art direction is ingenious and

breath-takingly surreal, matched by the dazzling and dizzing cinematography by Robbie Ryan. Accompanying the picture is a deranged score that goes from gentle harps to agitated organs and pipes created by Jerskin Fendrix that conjure a neurotic behaviour paired with the likes of the protagonist.

It’s narrative and ideas may not be as challenging an experience that Yorgos Lanthimos is used to birthing, but Poor Things is still an absurdly fun and stimulating ride about the physical pleasures and pains of existence.

Film: All of Us Strangers all of us strangers (2023)

Andrew Haigh’s All Of Us Strangers is an explosion of angst that spills from the confines of the neat London new-build where it is set. When I left the screen, the entire cinema was filled with the sound of sobbing. I wondered if I hadn’t been focusing as deeply on the film as other viewers - all I knew was I found the film perplexing. I thought it was seriously well edited, with moments of great dialogue, set design and acting. I also thought it reduced its emotional poignancy with relentless over-explanation and signposting. Nonetheless, the film is absolutely worth seeing. It is an hour and fortyfive minutes which will ask you to confront any lingering

feelings you may have towards loss, family, sexuality and relationships. It is sincere and personal, presenting what feels like genuine connection between filmmaker, actor and narrative. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, it cuts to the heart of why we tell stories which makes it deeply worthwhile.

The film centres around Adam, an unreliable narrator played by Andrew Scott who is trying to reconcile with the death of his parents through writing a screenplay about his childhood. A large part of this reconciliation is coming out to them. For Adam, the fact they don’t know about his homosexuality causes a disconnect and makes grieving for his loving parents complicated. How can he remember them as loving him if they never knew about this significant part of his life? From this point onwards, it is unclear if anything that happens is reality or his imagination. The film is imbued with nods to horror cinema. The theme of death is prevalent and ghosts are central to the narrative. There are numerous visual references to BBC style thrillers in the set dressing and camera work. Freudian scenarios are explored,

most notably when Adam’s father is swapped alarmingly with his boyfriend (Paul Mescal’s Harry). Scott and Mescal lean into threatening undertones which is reinforced by the sudden, intense relationship their characters have. All Of Us Strangers is therefore more than a melodrama: it is also a cerebral thriller, a romance, and a family comedy. In fact, the comedy scenes featuring Claire Foy are exceptionally well written and performed.

There are elements of the film that don’t work as well. The 80s theme is one striking example. Adam is stuck in the 80s: he only listens to 80s music, he dresses in 80s clothes, he constantly watches Top of the Pops reruns and his love interest, Harry, also only dresses in 80s clothes. Adam is fixated on the 80s because it was in this period that he lost his parents. This teeters towards making Adam a caricature and is bizarrely at odds with the subtle realism of the rest of the film. It is also tautologous: Adam’s ritualistic journeys to his childhood home to visit his parents’ ghosts is already confirmation enough that he is stuck in his traumatic past. Moments like this counter the subtlety of the rest of the piece. Signposting is a

useful technique to ensure that the audience can relate to the narrative, but it is a shame that Haigh doesn’t trust his viewers to infer these messages themselves.

Despite this pitfall, most of the film is nuanced and insightful. Nowhere is this more evident than the use of ghosts to explore trauma. Although this is a popular cinematic motif, it feels fresh. In All Of Us Strangers, it is not the ghosts that do the haunting, but instead it is Adam who haunts the ghosts of his parents. In doing so, he becomes needy, neglectful of Harry, and stuck in a destructive, selfish loop. Making this alteration to the haunting narrative places responsibility for Adam’s behaviour on his own lap suggesting that moving forward is something we have to choose ourselves. Unlike most ghost stories, Haigh never explains what the rules of the world are. In films like Beetlejuice and Talk to Me how and why supernatural beings enter and exit the natural world is a preoccupation. In Strangers, you don’t even get warned you will be confronting ghosts. The film denies you the nail biting moment where you want to shout at the protagonist to not use the ouija board. Alternatively you are initially unaware that you are looking at ghosts and preoccupied with why Foy is playing Scott’s mother. It is refreshing to watch a film that is so happy to let the audience lose themselves in its storytelling, and it is refreshing to watch a film that holds its melancholy lead responsible for their feelings.

Once you give into the phenomenological experience of watching the film you gain a lot. The drug/clubbing/nightmare sequence is authentically unnerving: a genius combination of sight and sound which focuses on depicting Adam’s emotional landscape over explicitly furthering the narrative. The colour imagery stayed with me a while too. There was something very violent in the use of the gentle LED colourings. Although the pinks and oranges were muted, their association with the

clubbing sequences made the intimacy inherent in those colours seem warped and confused. A lot of this film asks you not to rationalise but feel. It would be interesting to hear how affecting it is to audiences outside of the UK as a lot of the audiovisual references harken back to the national cultural lexicon (the Pet Shop Boys’ Always On My Mind was a particular favourite). Even the Christmas reference was specific - what day could Haigh have chosen that could have been more associated with warmth, coziness, and safety? The 80s Christmas scene was reminiscent of The Snowman, a film I watch with my family around the holidays. It perhaps isn’t an intentional reference, but it is a testament to the success of Haigh’s ambiguous filmmaking that it allows the audience to relate their experiences to Adam’s struggle.

At its core, the film is a dive into Adam’s head. When the final act reveal is made, the subjectivity of all that has come before it is abundantly clear. This is a film about a protagonist using storytelling to console himself and deal with his own issues surrounding intimacy. I love films which strike to the heart of storytelling in this way. It actually bears comparison to Mescal’s earlier project Aftersun. Both films deal with bittersweet reality that memory and filmmaking can only allow so much reconciliation with lost ones: whilst we may be able to see people again we cannot bring back their subjectivity. Maybe then the over-explanation can be forgiven if it is allowing people to relate their own experiences to this narrative and find some catharsis through watching it. Maybe the slightly on-the-nose choice of The Power of Love as the closing song can be forgiven if it reminds the viewer that sometimes it is okay to have unfinished business because the future may hold a new sort of answer. And, at the risk of repeating myself, it is seriously, seriously well edited.

20,000 Species of bees

20,000 Species of Bees (2023) Estibaliz Urresola Solaguren

I hope this film finds itself in the list of queer cinema you watch when trying to understand yourself. I was around the same age as Lucia when I was mistaken for a boy. I wore ‘boy’ clothes and had ‘boy’ hair, not a tomboy, just a girl that expressed themself a different way. I immediately related to Lucia because of this. An androgynous kid finding comfort in who they are. A mother and her three children cross the border from France to Spain to attend a family baptism, and use her late fathers studio workshop. The youngest, questioning their identity, finds comfort amongst the family’s beehives and matriarchs. This is an incredibly rich film, full of colour and life. The more I look into this film the better the direction and writing become. The film speaks to itself and breaths. Urresola approaches a difficult subject with taste and real care.

Intimacy

Estibaliz Urresola

Solaguren’s feature debut is an incredibly intimate film. Mainly because of how close the camera is to the actors. This is always a brave decision as it makes the film rely on performance, which Urresola was right to do. Sofia Otero is now the youngest actor to win the Silver Bear for best leading performance, at only 8 years old.

The opening shot of Lucia and her mother (played by Patricia López) facing each other in bed having a whispered conversation. This becomes a motif of the film. Lucia laying with a loved one asking them why they feel so conflicted, what if something went wrong in mum’s tummy? And how does her brother Eneko knows he is a boy? Urresola’s use of these mundane moments is a really wonderful outlet for Lucia’s feelings. It allows the audience to share without feeling voyeuristic.

Another moment I want to talk about is right at the end of the film. Lucia informs the bees of her new name, the way her great grandmother announced new additions to the family. It is one of the few moments Lucia is actually alone and small on the screen against the Spanish landscape. They are announcing to themselves as much as they are the bees.

Identity

“If something doesn’t have a name it doesn’t exist”

This film is primarily about a child figuring out who they are.

Our Protagonist has three names in this film. They are first introduced to as Coco, a nickname given by older sister Nerea, they initially hate it but later adopt it to pass off as a girl. Second, when their birth name ‘Aitor’ is revealed by their mother Ane, and they are devastated. The shame they previously attributed to their toes. Third, the name Lucia is chosen. In the homemade bonfire scene there is no wish to be a girl, only to be called Lucia.

Like the beeswax made by the family, identity is fluid and mouldable in this film. When asked to sculpt self-portraits, all three children’s desires are revealed. Eneko moulds himself and his dad, perhaps wishing Gorka was more present. Masculinity exists like a ghost

in this film, just in the background. Nerea moulds her perfect body, also exploring their femininity over this trip. Nerea wishes to be like a mysterious, older, fashionable cousin. Finally, Lucia makes herself as a mermaid. Not bound by sex or gender, just half fish. Their mother tries to pass off her father’s sylphids as her own work. Long beautiful women that her father fixated on over her.

Faith

“Grandma why am I this way” “What do you mean ‘this way’? God made us perfect”

One thing that made me fall in love with this film was that it allowed faith and queerness to exist in the same space without clashing. There is no calling the little Lucia a sinner or sending to hell. In fact, it is discussions about faith that help Lucia discover themselves. Aunt Lourdes explains that faith is like knowing your eyes aren’t blue, but goes deeper than that, it is knowing without proof. Lucia knows her eyes aren’t blue, and knows she isn’t a boy.

Great aunt Lourdes, named for a place of healing and miracles, is a

healer and assigned the role of ‘beekeeper’ by Lucia. They are the first to get Lucia to swim without embarrassment and are the first person to notice Lucia identifying with being a girl, perhaps before Lucia. The film builds up to the baptism of Lucia’s baby cousin. Which is threatened by the missing statue of John the Baptist. The family searches the town, and the river for days but ultimately it is Lucia that finds it.

Lucia and Niko must enter the water to retrieve the statue, but swap their ‘girl’ and ‘boy’ swimming costumes beforehand.

Lucia is finally wearing a girl’s costume and doesn’t feel the embarrassment they felt earlier in the film at the public swimming pool. They then enter the water with John the Baptist, almost as if they are getting baptised themselves. Aitor is reborn as Lucia.

I had not come across Saint Lucia before, and so was curious as to why she was chosen as Lucia’s name sake. Saint Lucia is a virgin martyr that plucked out her eyes to deter any potential suitor. Much as our Lucia and her eyes are praised for their beauty. Of course, a knowledge of Christian canon isn’t required to enjoy this film, but the more I research the more rich this film becomes.

Khushi Jain

Khushi Jain

Film:Best UK Shorts

On November 15th, the Poly played host to six short films selected in the ‘Best UK’ strand of the 2023 edition of the Cornwall Film Festival. This curated programme comprised a diverse collection of narratives, including one documentary and one animation. Engagement with the female experience emerged as a thematic Ariadne’s thread, with filmmakers exploring questions of space, agency, sisterhood and childhood. There also seemed to be a focus on climate change, and how we are and probably will confront this global issue.

‘Safe Space’ Dir. Isabel Songer

Isabel Songer’s ‘Safe Space’ is an empathetic glimpse at girlhood from the perspective of a bathroom mirror at a secondary school. This short follows a series of loosely connected moments in the lives of young girls, shedding light on their experience of adolescence, first love, friendship, loneliness and everything else that surpasses scholastic curriculum. The girls bathroom is investigated not only as a safe, feminine space, but also as the hub of all drama, from gossip and embarrassing moments, to naive inscriptions of romance and the challenges of mental health. The camera observes but never penetrates this very private world; its immobility certainly diffuses the tendency to violently and sexually

objectify, but Songer’s gaze on the female body is also very consciously narratorial and empowering. She evokes an uneasy nostalgia by incorporating relatable affairs while also compelling us to ask: what defines a safe space?

‘I am Kanaka’ Dir. Genevieve Sulway

Genevieve Sulway’s ‘I am Kanaka’ strips away Hawaii’s touristy paradisiac identity, and lays bare the dark past and difficult present of the indigenous people, while hopefully envisioning the possibility of a better future. Sulway does not dwell on the problems but on those who are making an effort to solve them, and one such individual is Kaina Makua. Disillusioned with the public schooling system, Kaina set up a non-profit ‘Kumano I Ke Ala’ for underprivileged indigenous kids. The organisation supports and teaches the Hawaiian language, sustainability and basic life skills, uplifting the community and also strengthening their connection with their roots. A fairly traditional documentary, this short consists of several local testimonies and affirms that the future of this island state depends on people like Kaina.

‘The Virtual Llama’ Dir. Tom Cozens

In the futuristic dystopian world of Tom Cozens’ ‘The Virtual Llama’, human beings are able to live perpetually youthful lives and simultaneously tackle the population crises by uploading their minds onto a virtual realm known as ‘paradiso’. Francis chooses this virtual existence, while her sister Emily sits next to her lifeless body, clutching two llama stuffed-toys. It is only through a phone that Emily can now talk to Francis, who has essentially become like the llama toys: she doesn’t consume, grow or evolve. But unlike the llama toys, she cannot be touched, cannot hold hands, hug or kiss. Both Emily and Francis soon realise this tactile starvation and are enveloped in a sense of loneliness. Cozens’ film examines the relationship that our bodies have with the virtual world and the role that technology might have to play to help us combat climate change. It is set in a lush field of flowers resembling Eden, a paradise, which Cozens treats as an antithesis to the virtual ‘paradiso’. Sounds are manipulated to support the narrative and what we have is a fairly bleak but perhaps not too fantastical vision of the future.

‘The Ride’ Dir. Tara Aghdashloo

Three perspectives collide in a drive towards London, exposing the intricacies of human experience in Tara

Aghdashloo’s ‘The Ride’. This short begins with a young couple, Alex and Panchi, hitching a ride with a lorry driver, after their car breaks down. What follows is a slow and superficial unravelling of their romantic relationship, which includes conflicts surrounding female agency and race. Panchi feels oppressed and infantilised with Alex, and Aghdashloo analogies her state through images of caged birds. Thematically, the film becomes problematic when Panchi, a member of the Indian diaspora, accuses Alex, her white English boyfriend, of ‘colonising’ her. The casual use of such charged terminology is troubling to say the least. The film reflects the flimsiness of Panchi’s character, and although beautifully shot, prioritises style over substance. One ends up lamenting not what Alex and Panchi could have been, but what the film itself could have achieved.

‘Firefly’ Dir. Anne-Marie Scragg

‘Firefly’ chronicles the life of Frankie, a deaf girl, whose world is thrown into turmoil after her father remarries and moves to work on an oil rig, leaving her with an abusive stepmother. Set in a Cornish fishing village, it pays ample homage to its landscape without turning the stunning coastal visuals into cinematic pastry. Albeit some of the drama is over the top, Anne-Marie Scragg’s storytelling is gentle. The highlight of this short is the performance of Olivia Pickering (young Frankie); she

looks about innocently with her big blue eyes and there is love in everything she does. On the whole, ‘Firefly’ does a good job with its material, capitalising on its high-octane emotional currency.

Sugar, Spice and Everything Nice!’ Dir. Anoushka

Agarwal

The only animation in this programme, ‘Sugar, Spice and Everything Nice!’ is Anoushka Agarwal’s scrutiny of gendered roles and powerplay in the domestic sphere. In what looks like a dollhouse, a woman silently maintains the decorum of neatness, doing laundry, ironing clothes, washing dishes, sewing, sweeping, etc. Her movements are underscored by a habitual and matter-of-fact attitude, suggesting an indoctrination of the patriarchal division of responsibilities. This routine is regularly interrupted by red vaginal protrusions from the walls of the house, which, perhaps deliberately, are reminiscent of the cushioned walls of asylum cells. From the set to the sound, each detail is carefully designed in this short and its wordlessness imitates the unspoken traumas women often experience in what is supposed to be the safest of places: home.

If you would like to join the next New Wave Jury, or any other opportunity with Mor Media, sign up for our newsletter,The Mor Media Memo, or follow us on social media, and keep an eye out for the application details.

www.mormediacharity.org/new-wave

www.mormediacharity.org